#Mount Hiei

Text

雨上がり,少し霞みの残る遠景。

比叡山

January 2024

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roses and Mount Hiei as seen from the Kyoto Botanical Gardens, Japan.

#Botanical Gardens#Japan#Koyo#Kyoto#Kyoto Botanical Gardens#Mount Hiei#Rose Garden#Roses#autumn#autumn photography#travel#trees#もみじ#バラ#京都府立植物園#比叡山#紅葉

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

A hanging scroll of the Hie Sanno Mandara (日吉山王曼荼羅), a mandala depicting the local deities of Hie Jinja Shrine (日吉神社), i.e. present-day Hiyoshi Taisha Grand Shrine (日吉大社) in Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, as manifestations of the Buddhist divinities of Mount Hiei (比叡山) north of Kyoto, with the deities and divinities matched up throughout the landscape of the mountain

Color on silk dating to the Kamakura period (1185-1333) from the collection of Hyakusaiji Temple (百済寺) in Higashiōmi, Shiga Prefecture

Image from "Shintō: The Sacred Art of Ancient Japan" edited by Victor Harris, published by the British Museum Press. 2001, page 173

#japanese art#buddhist art#曼荼羅#mandala#滋賀県#shiga prefecture#東近江市#higashiomi#百済寺#hyakusaiji#天台宗#tendai#比叡山#hieizan#mount hiei#日吉神社#hie jinja#日吉大社#hiyoshi taisha#日吉山王曼荼羅#hie sanno mandara#crazyfoxarchives#arte budista#arte japonés

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

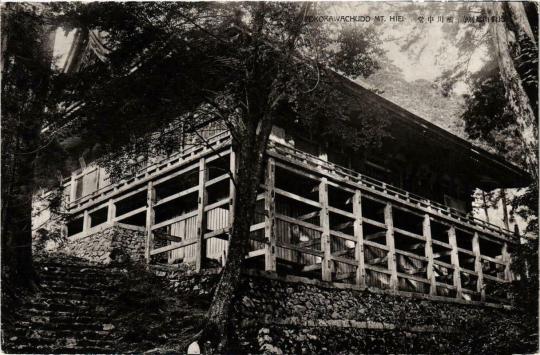

Yokawa Main Hall of the Enryaku-ji monastery, on Mount Hiei in Ōtsu, Japan

Japanese vintage postcard

#main#japan#historic#photo#briefkaart#vintage#hall#ji#mount hiei#monastery#sepia#yokawa#yokawa main hall of the enryaku-ji#photography#carte postale#postcard#hiei#postkarte#postal#tarjeta#enryaku#ansichtskarte#old#ephemera#ōtsu#postkaart#tsu#japanese#mount

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

In “defense” of the Enryakuji invasion

This is the clash of two military and political powers that finally came to a head, not a one-sided oppression

When people cite the invasion of Enryakuji to accuse Nobunaga of all sorts of horrible things, it’s usually because they were under the impression that an unreasonably large number of people were killed, or that it was an oppressive massacre against a community that weren’t posing a threat.

It’s very unfortunate that it’s very rarely clearly explained to the general public that Enryakuji has armed forces. In a lot of ways it’s almost functioning like a samurai lord’s castle, inhabited by both warriors and civilians alike. They also had massive political power and influence. They’re not a quiet little temple whose inhabitants were peaceful or helpless.

The warrior monks of Enryakuji themselves have committed massacres and invasions. They do not accept other sects rivalling them, either out of genuine religious zealotry and considering the other sects “heretics”, or because they simply want to maintain their sect’s influence and authority in Kyoto. They were not politically neutral, nor were they pacifists.

(A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism, page 178)

I emphasise the part where it says the Enryakuji warriors wrecked Kyoto so badly, it’s equal to -- or even worse than -- the destruction in Kyoto when the Onin War broke out. These monks are vicious and violent.

They were still meddling in politics and battle in Nobunaga’s time. During Nobunaga’s battles with the Azai and Asakura, these monks joined in the forces opposing Nobunaga. They took part in besieging Usayama Castle, which resulted in the death of one of Nobunaga’s brothers and some other senior vassals.

The killing of thousands of combatants and civilians alike regularly happens when any one lord invades another territory. There are no stipulations to spare civilians. If a lord decided to evacuate civilians first before the invasion, then it is a benevolent act. Otherwise, civilian casualties is just a fact of life in that time period.

In which case, how is Nobunaga’s invasion any different than, say, the occasion where Nobunaga invaded Mino and conquered the Saitou? That's rarely, if ever at all, cited that as an example of cruelty. That was just a battle.

There is no reason to be especially horrified about this Enryakuji incident above any other battle or invasion. This is nothing about this battle that more morally outrageous than what every samurai commander regularly do when engaging another samurai in battle.

I would grant that many people may think that any mass-death is automatically horrible, and perhaps no amount of reasoning and justification can make the Hieizan invasion and burning defensible. There is no denying that thousands of people were killed in Enryakuji. It’s fine if one were to still condemn this even after knowing the circumstances. Still, knowing and understanding the context matters.

The Hieizan situation only looks different than a regular castle invasion because Enryakuji has the facade and still does operate as a temple. There is something about religious sites that inherently invokes the image of sacredness after all, regardless of the faith, and the general public tends to view them differently than a regular fortress or castle.

It is true that there were contemporary Sengoku writers who severely criticised Nobunaga for his actions. However, for the Japanese at the time, Enryakuji is a holy site with immensely deep cultural and spiritual significance. Not just the temple, but the whole mountain itself. No matter how justified Nobunaga was, or even if nobody was killed, people were going to be up in arms about it simply for the fact that Hieizan was targeted.

Think of the time when the Notre Dame caught on fire. People from all over the world were horrified. Imagine how much worse would it be if, say, there’s a fire in the Vatican. That’s what it was like for the people there at the time.

On top of that, the chief priest of Enryakuji also happens to be the emperor’s brother. This invasion can be perceived to be disrespectful to the imperial court. It only worsens the uproar surrounding this situation, which then supposedly led to the dramatic letter where Nobunaga calls himself the Dairokuten Maou in a spiteful reply to Shingen’s letter rebuking him in the name of the chief priest.

An additional point in the “defense” is the numbers. For some reason there is a claim that 20 thousand were killed in the Enryakuji invasion. I have yet to find the exact source of this information. Wikipedia and other online articles cite Stephen Turnbull’s book, but I cannot find corroboration for this claim in the original historical documents.

Shinchoukouki said "many thousands” and did not specify a number, and Luis Frois recorded that he was told around 3000 were killed (about 1500 combatants, and 1500 civilians).

(They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543-1640, page 99)

The claim of 20 thousand people killed also does not make sense as, supposedly, there weren’t even 10 thousand people inhabiting the Enryakuji complex in Hieizan at the time. How can the dead amount to more than double the actual number of inhabitants?

Lastly, there’s also reports from on-site research that claims that, as of 1980s, they weren’t able to find “proof” of massacre or mass-burning. They have yet to find the human remains of the dead, nor expansive traces of burning in the soil. The burning traces that was discovered were very minimal, compared to the narrative of “the whole mountain was up in flames”. On top of that, there were existing textual records describing many of the buildings were already dilapidated and abandoned as of 1570, and so even if they were burnt, there were no casualty or major losses.

However, this is a decades old report and I haven’t seen any certified updates on this yet. To be able to make a definitive claim, they would have to conduct a scan of the whole mountain, which is difficult to do.

#japanese history#enryakuji#enryaku-ji#hieizan#hiei-zan#mount hiei#mt hiei#oda nobunaga#sengoku#Sengoku period#Sengoku Era#Warring states#Warring States Era#Warring States Period#nobunaga oda#samurai

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Estação no Monte Hiei

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

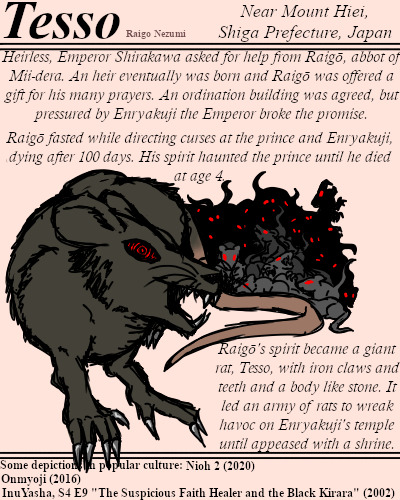

A spirit so vengeful, he transformed into a malicious yokai.

Tesso was a giant rat that lead an army of rats, its body was hard like stone with claws and teeth of iron. The thousands of rats devoured numerous scripts and other objects within the Enryakuji until he was placated.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#yokai#japanese folklore#tesso#raigo nezumi#rat yokai#iron rat#vengeful spirit#raigo#onry��#mount hiei#emperor shirakawa#enryakuji#mii-dera#ghost#youkai

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Taira No Kiyomori (Ep 13)

The powerful Emperor controls everything but the flow of Kamo River, the rolling dice of gamblers and the warrior monks.

#taira no kiyomori#kenichi matsuyama#taira no tadamori#kichii nakai#emperor shirakawa#kamo river#warrior monks#kyoto#mount hiei#japan#japanese drama#historical drama#taiga drama#j drama#jdrama#dorama

1 note

·

View note

Text

The real life inspirations behind new characters in Touhou 19 (Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost)

While I haven’t been posting much about Touhou as of late, I felt obliged to put together the customary post about the inspirations behind the new characters. The new game genuinely renewed my interest. In contrast with similar write-ups pertaining to previous games the research is not entirely mine - some of the sections are a result of cooperation between me and @just9art.

Without further ado, let’s delve into the secrets of the new cast. Find out if Biten is the first “Wukong impersonator” ever, when a tanuki is actually a badger, and why Hisami both is and isn’t an oni. Naturally, the post is full of spoilers. Also, fair warning, it's long.

1. Biten Son - sarugami + Sun Wukong

Sarugami means “monkey kami”, the monkey in mention being the Japanese macaque.To my best knowledge, the term is actually not used commonly in English - the results on jstor and De Gruyter are in the low single digits, Brill outright has nothing to offer. Translations are much more common.

Sarugami are particularly strongly associated with Mount Hiei. You might have heard of it because of its association with Matarajin, though in this case he’s not exactly relevant. Instead, it is believed the monkeys act as messengers of Sanno (the “mountain king”), Sekizan Myojin and Juzenji. Sanno himself could take the form of a monkey according to medieval texts, while Juzenji can be accompanied by a deity depicted as a man with a monkey’s head, Daigyoji, known from the Hie mandala. Sarutahiko is also associated with monkeys based on the similarity between his name and the word saru.

Bernard Faure notes that despite the clearly positive portrayal of monkeys as semi-divine beings in service of these deities, their perception in folklore and mythology can nonetheless be considered ambivalent, because they could be viewed as aggressive. There are even examples of sarugami being portrayed as monstrous antagonists to be defeated by a hero. The best known tale of this variety is known simply as Sarugami taiji. It is preserved in the Konjaku monogatari. Here the sarugami is a fearsome monster who terrorizes a village and demands the offering of one young woman each year.

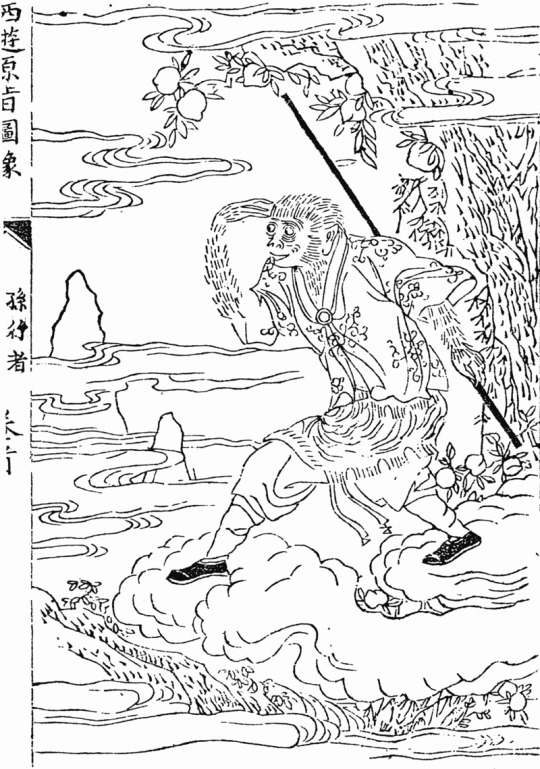

In contrast with the sarugami, I do not think Sun Wukong, one of the protagonists of the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, needs much of an introduction. We reached the point where even in the west he is recognizable enough to warrant toys based on him (there’s a Lego Wukong on my desk right now). Biten's design has many callbacks to traditional portrayals of Wukong, including the staff (which in the novel is a pillar stolen from the undersea palace of a dragon emperor) and a very distinctive diadem (in the novel making it possible to pressure the unruly Wukong into obeying the monk he is meant to protect).

As a curiosity it’s worth noting that “fake Wukong” is not a brand new idea - in the novel itself, one of the enemies of the heroes, Six-Eared Macaque, actually impersonates him for a time.

Wukong is effectively himself a “divine monkey”, seeing as despite his origin as a literary character he actually came to be worshiped as a deity in mainland China, Taiwan and various areas with a large Chinese diaspora. The topic of Wukong worship itself came to be an inspiration for literature, starting with the excellent The Great Sage, Heaven’s Equal by Pu Songling, a writer active during the reign of the Qing dynasty, in the early eighteenth century.

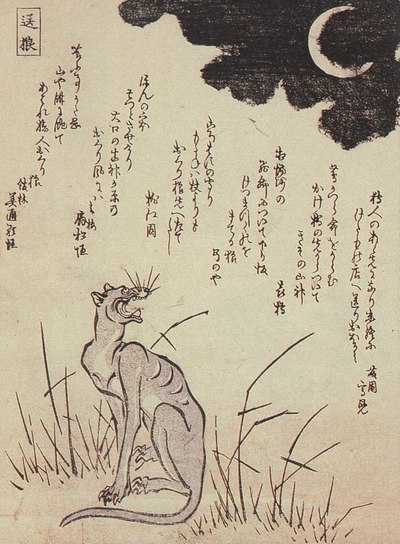

2. Enoko Mitsugashira - “immortal yamainu” + Cerberus

Enoko gets the least coverage here, because there really isn’t much to say. Yamainu, “mountain dog”, isn’t really a supernatural creature, it’s an old term for either the extinct Japanese wolf, a type of feral dog, or a hybrid between these. It can also be used as a synonym of okuri-inu, a youkai wolf believed to accompany travelers at night.

There’s actually a distinctly Journey to the West-esque component to Enoko’s backstory, but I have no clue if this is intentional. In the aforementioned novel, many of the antagonists, who are generally demonic animals, are motivated by the desire to devour the flesh of the protagonist, the Buddhist monk Tang Sanzang, because it is said to grant immortality. Granted, given the obscurity of the figure Zanmu is based on - more on that later - perhaps this is an allusion to something else we have yet to uncover.

Cerberus, being probably one of the most famous mythical monsters in the world, does not really need to be discussed here. The illustration is included mostly because I like Edmund Dulac and any opportunity is suitable for sharing his illustrations. I do not think it needs to be pointed out that Enoko's bear trap weapons are meant to evoke Cerberus' extra heads.

3. Chiyari Tenkajin - tenkaijin (+ mujina) + chupacabra

While my favorite animal youkai not yet featured in Touhou is easily the kawauso (otter), I was very pleased to learn we sort of got a mujina since I wanted to cover this topic since forever, but never got much of a chance. Technically Chiyari is actually meant to be a tenkaijin, which is not a mujina but a slightly different youkai (a will-o-wisp or St. Elmo’s fire-like creature, specifically) who in the single tale dealing with it takes the form of a mujina after dying, but as there is not much to say about it beyond that you will get a crash course in mujina folklore instead.

Today the word mujina is pretty firmly a synonym of anaguma - in other words, the Japanese badger. The animal does not substantially differ from other badgers, so I do not think much needs to be said about its ecology. However, historically the term could be used to refer to the tanuki regionally, or interchangeably to both animals, so in some cases if insufficient detail is provided it is hard to tell which one is meant.

This ambiguity extends to the folklore surrounding them, and generally if you know what to expect from tanuki tales, which I’m sure most people reading this do, you will instantly recognize many of the plot elements typical for mujina ones. In other words, it is yet another yokai which typically takes the role of a shapeshifting trickster. Some supernatural phenomena could be basically interchangeably attributed to mujina, tanuki, kitsune or kawauso. Mujina are commonly described taking the form of Buddhist monks, which is one of the many similarities between them and tanuki.

The most famous depiction of a shapeshifting mujina comes from Toriyama Sekien’s Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki (The Illustrated One Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past). The accompanying text compares the creature to the supernatural versions of kitsune and tanuki, and states that the artist relied on a tale according to which a mujina was able to successfully impersonate a Buddhist monk until accidentally revealing its tail.

What makes the mujina special is that it is actually the oldest recorded example of a youkai of this sort. A mujina tale already appears in the early Japanese chronicle Nihon Shoki, dated to 627. It reports an incident of a mujina transforming into a human and singing somewhere in the Michinoku Province. I feel like this alone is a good example of why you should be wary of people who seek to present Nihon Shoki or Kojiki as historical truth.

Western audiences as far as I know were first introduced to mujina by Lafcadio Hearn. To my best knowledge, the fabulous shapeshifting badgers however failed to gain the popcultural recognition enjoyed by tanuki and kitsune. They did appear in Shigeru Mizuki's stories every now and then, and I found a mascot character based on them, but overall there isn't all that much beyond that.

Naturally, there isn't much mujina in Chiyari's design, and she instead most likely owes her distinctly spiky appearance to the other inspiration behind her character, the chupacabra. Mujina are not really portrayed as bloodthirsty, but the poorly documented tenkajin apparently is, which is presumably why ZUN decided to connect Chiyari with the chupacabra, the best known modern blood-drinking creature, who first appeared in tall tales from 1995 and subsequently took popculture by storm after spreading from Puerto Rico to mainland USA and Mexico. I am not a chupacabra aficionado so I have little to offer here, sadly.

4. Hisami Yomotsu - yomotsu-shikome

Judging from what I’ve seen on social media and on pixiv, Hisami is shaping up to be one of the most popular new characters (she’s my fave too). In sharp contrast with that, her basis is pretty obscure. So obscure that there isn’t even any historical art to showcase, as far as I can tell (note that this blog claims night parade scrolls might have something to offer, though - I was unable to verify this claim for now, sadly). As we learn from her bio, she is supposed to be a yomotsu-shikome. They’re called the “hags of Yomi” of Yomi in Donald L. Philippi’s Kojiki translation. The term shikome can be literally translated as “ugly woman”. Nothing about them really implies femme fatale leanings we are evidently seeing in Touhou but I’m not going to complain about that.

Yomotsu-shikome appear only in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, and in both of these early chronicles they are portrayed as servants of Izanami after she died and came to reside in Yomi, the land of the dead. Nihon Shoki states there are only eight of them.

The distinct grape vine motif present on Hisami’s clothes seems like an obvious reference to Izanagi’s escape from Yomi following his meeting with Izanami, portrayed in the myth recorded in both of these sources. When the yomotsu-shikome started to pursue him, he threw a vine he used to hold his hair at them. The plant instantly bore fruit, which the entities started to eat. They later resumed the chase, but were once again held back, this time by a bamboo shot. According to the Nihon Shoki, they eventually give up after he creates a river from his piss (sic) to keep them away.

Yomotsu-shikome are sometimes compared to oni by modern researchers. Noriko T. Reider in her monograph about oni argues that alongside hashihime and yamanba (pictured above) they can be effectively grouped with them. Another researcher, Michael D. Foster, is more cautious, and states that despite clear similarities it’s best to avoid conflating oni-like female demons with female oni proper, especially since the latter have a distinct iconography and a distinct set of traits. Norinaga Motoori, the founder of kokugaku or “national learning”, a nationalist intellectual movement in Edo and Meiji period Japan, claimed that oni were based on yomotsu-shikome, which is a pretty dubious claim. It is ultimately not certain when the term oni started to be used, but it is safe to say it has continental origin. And, of course, oni permeate Japanese culture in a way yomotsu-shikome do not.

5. Zanmu Nippaku - Zanmu

This was the toughest mystery to solve, and I am fully indebted to 9 here, since they figured it out, I am merely depending on what they directed me to. Research is still ongoing, and it feels like we just started to untangle this mystery, so you can safely expect further updates.

Zanmu appears to be based on the Buddhist monk… well, Zanmu. You can learn a bit about him here or on Japanese wikipedia; it seems there are quite literally 0 sources pertaining to him in English, and even in Japanese there is actually very little. Their names are not written the same, ZUN swapped the sign for “dream” from the original name for one which can be read as “nothingness”. If the unsourced quote on wikipedia is genuine, the reason might be tied to the personal views of the irl Zanmu. What little we’ve been able to gather about him is that he was active in the Sengoku period, and apparently was regarded as unorthodox and eccentric. This lines up with Zanmu’s omake bio pretty well. Seems the real Zanmu was also unusually long lived, and was able to recall events from distant past in great detail, though obviously the figure of 139 years attributed to him in a few places online has to be an exaggeration.

Yet more puzzling is the reference to Zanmu’s familiarity with Ikkyo you might spot in the linked article. Whether the famous Ikkyo who you may know from the tale of Jigoku Dayu is meant is difficult to determine. The chronology does not really add up; on the other hand the logic behind associating one eccentric semi-legendary monk with another in later legends isn’t particularly convoluted. As 9 pointed out to me, if ZUN was aware of this link, and the same Ikkyo really was meant, it is not impossible the connection between Zanmu and Hisami is meant to in some way mirror that between Ikkyo and Jigoku Dayu.

As you can easily notice, it’s pretty clear the historical Zanmu was male. It does not seem his Touhou counterpart is, obviously. I would say we should wait for more info until declaring that we have a second Miko situation on our hands, with a male historical figure directly reimagined as a female character without any indication we are dealing with a relative rather than the real deal. There’s still relatively little info to go by so I would remain cautious (though naturally this is not meant to discourage you from having headcanons).

Neither me nor 9 were able to find any connection between the historical Zanmu and oni… so far, at least. Therefore, what motivated ZUN to make Zanmu an oni remains to be discovered.

As a final curiosity, on a semi-related note it might be worth pointing out that while not as common as their male peers, female oni are not a modern invention, and already appear in setsuwa from the 13th century. A particularly common motif are tales describing a woman turning into oni due to jealousy or anger.

Further reading:

Jason Colavito, The Secret Prehistory of El Chupacabra (2011)

Bernard Faure, Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 1-3 (2015-2022)

Michael Daniel Foster, The Book of Yokai. Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore (2015)

John Knight, Waiting for Wolves in Japan. An Anthropological Study of People-wildlife Relations (2003)

Noriko T. Reider, Japanese Demon Lore (2010)

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

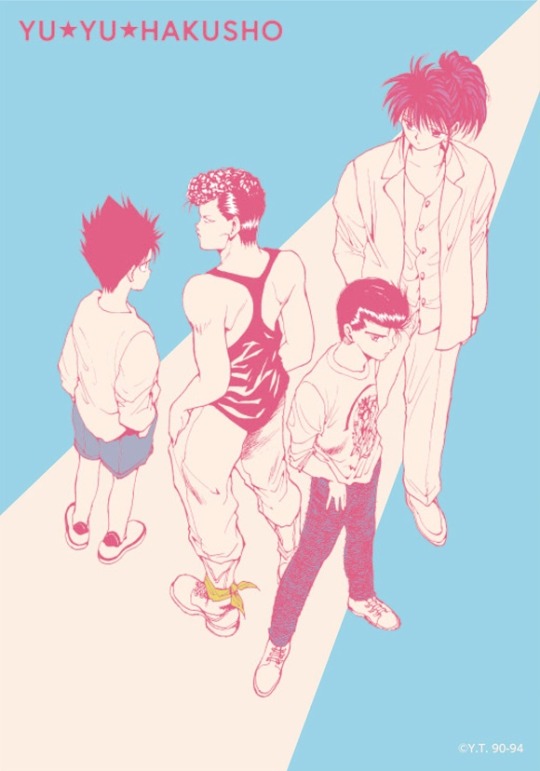

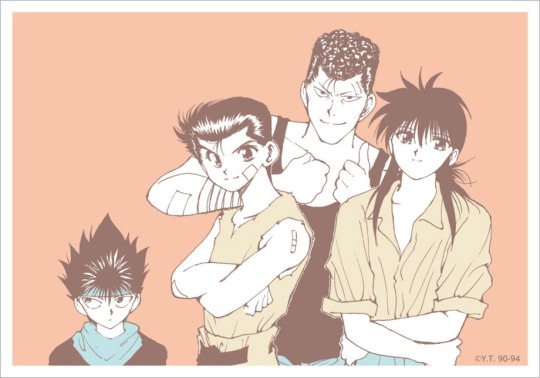

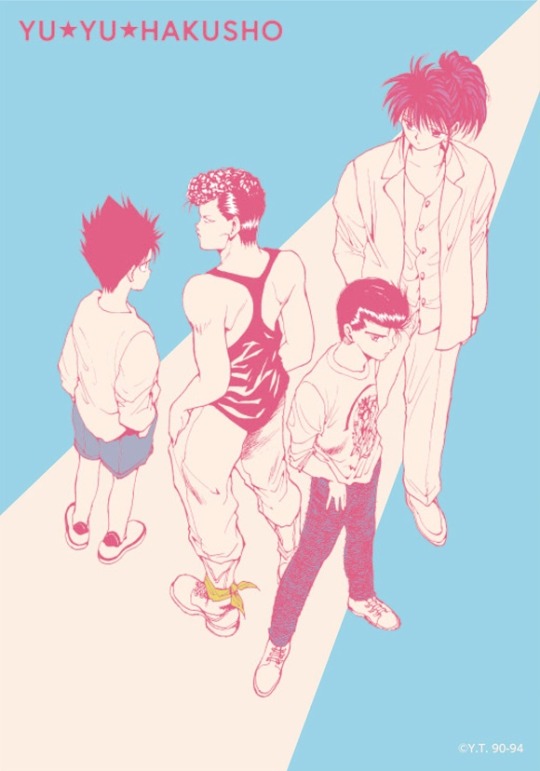

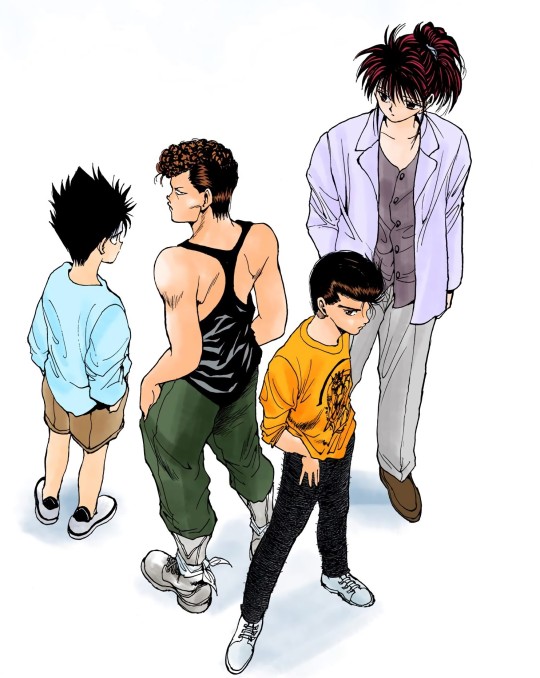

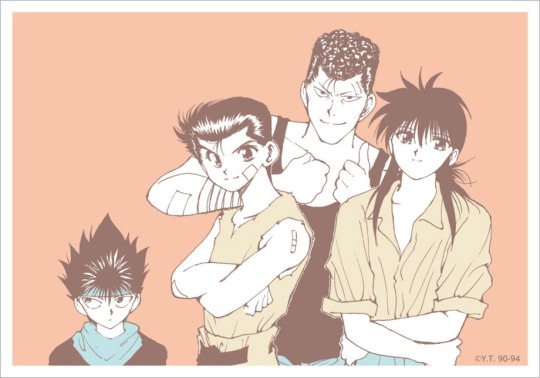

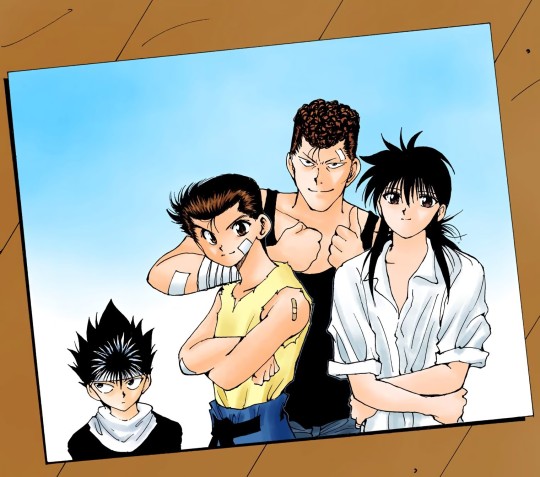

Yu☆Yu☆Hakusho "Battle Days" Bromide Prints

Yoshihiro Togashi Exhibition - Fukuoka Venue

Price: 660 yen

After the "Attention" Sticker Collection, a set of 3 bromides plus a photo mount, with Yusuke, Kuwabara, Hiei and Kurama illustrations, was announced on the Puzzle Official Site. This is another exclusive merch that will be sold at the Fukuoka Venue.

The mount surface is a mix of the end of chapter 91, after Yusuke sees Genkai being killed, and Kurama, Hiei and Kuwabara's faces from the opening of chapter 78.

The first bromide is part of the opening of chapter 77. They just removed Toguro.

The second bromide is the opening of chapter 130. I like this illustration so much, because Hiei is wearing shorts and Kurama's hair is tied back in a ponytail. Please, have a look at Kurama & Hiei Fashion Variation from the Yu Yu Hakusho Official Characters Book.

Finally, the third bromide is the famous group photo from the last chapter.

#Yu Yu Hakusho “Attention” Sticker Collection#Yu Yu Hakusho “Battle Days” Bromide#Yoshihiro Togashi Exhibition#Fukuoka Venue#Hiei#Kurama#Kuwabara#Yusuke#Dark Tournament

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Anthony J. Crowley

Summary:

Aziraphale’s learned that Crowley hates being perceived directly. Like a snake in the grass he likes to sidle, to sneak, to slip, to avoid exposure. It’s the reason behind the dark glasses, the reason he drives so fast, the reason he never stays still, never relaxes. It’s hard, sometimes, when Aziraphale’s true form has so many eyes, and all he really wants to do is watch Crowley.

I.

Crowley’s eyes are lovely. Sometimes yellow, sometimes brown, often guarded, they move snakily - they dart, they track side to side, they stare, unblinking. And Aziraphale sees them so little. Still, Aziraphale supposes, it is Crowley’s prerogative. Aziraphale remembers when Crowley had first started hiding his eyes. It had been Uz, and Aziraphale had thought at first it might be a passing fad; Crowley was always so informed on the latest human fashions. Occasionally, Aziraphale wondered if he had invented a few himself.1 But as the centuries passed and Crowley’s glasses only grew larger, and darker, and hid his eyes more effectively, Aziraphale began to wish that perhaps, just once, he would take them off again.

And then perhaps his prayers - so to speak - are answered, because he and Crowley both end up, independently, at the Heian Court at the turn of the first century in what will later become Kyoto. They each have their own assignments: Aziraphale to influence a particular marriage, Crowley, apparently, to encourage the young women of the court to write books that will, he assures Aziraphale, lead to something called a live journal. Eventually.

One morning in the first month they find themselves part of the Court’s expedition to Mount Hiei to observe the snowfall; all members of the expedition are each to write a poem, and then present it, later, to the Emperor for his judgement. So the court sets off, a band of courtiers in brightly-colored over-robes, the women carried along in their carriages, hanging their sleeves gracefully out the open windows to whisper over the snow.

Aziraphale’s fallen behind, watching the humans enjoying themselves, watching Crowley, a little further ahead, up to his usual petty mischief. Crowley sidles around the senior court officials, whispering in their ears. What’s he’s suggesting soon becomes clear as they gather up handfuls of snow and stuff them into the women’s dangling exposed sleeves. Aziraphale hears feminine squeals and screams, and the women’s arms disappear back into the carriage, only to reemerge with triumphant palmfuls of snow. Splat. Crowley, smiling slightly at a job badly done, saunters back, slowly, to join Aziraphale.

“You are impossible,” Aziraphale sighs, raising his hand to his eyes to shield them from the sun, which is strong in the sky behind Crowley. He winces a little. He’s still not used to the blinding nature of snow in sun, has spent too much time in temperate climes. Besides, he’s still not sure about this whole snow thing. It’s cold, it’s wet, and its brightness reminds him of Heaven. Aziraphale must be making a face at this thought, because Crowley sighs, then, reaching up and taking his own dark glasses off. He holds them out to Aziraphale, snapping the fingers of his other hand, suddenly holding a new pair, even more stylish than before.2 Aziraphale steps towards him, reaches out to take the glasses and - stops in his tracks.

Crowley looks like a woodcut, a stark print against the white wide expanse of snow, all around them unbroken and blinding. His dark, black silk robes make him stand out from his surroundings like a blackbird; his hair, red and long and dark, spills loose and curling down his back in an approximation of the women’s style of the Court. Blood on the snow, sharp and present. And his eyes - Crowley’s eyes today are fiercely warm, soft amber, opaque and lovely, the dramatic black slash of his pupils and the whites of his eyes making them stand out like rare beads. Crowley’s mouth opens; he stops, frowning. His eyes flicker over Aziraphale, up his body, across his face, come to rest on his own. Aziraphale feels pinned, like a small animal of prey, and he makes a noise, a half-breath, and then the others, turning and seeing that they’ve fallen behind, call out, breaking the spell between them.

Crowley slides his new glasses on and Aziraphale does the same. It helps with the glare. It helps with - a lot of things, really. He finds he can watch Crowley, as they hurry to catch up - well, Aziraphale hurries, and Crowley saunters, and somehow they end up there at the same time.

Aziraphale’s poem, later, is simple and plain.3 It’s largely ignored in favor of the more objectively lovely or ostentatious poems - those about the moon, or plum blossoms, or green shoots, although Shonagon shoots him a sidelong glance when he reads it aloud. Crowley’s in the back of the room, arms crossed, leaning against a thin partition, and Aziraphale’s half-afraid he’ll fall through, but he doesn’t: the perfect balancing act. His face, under the new glasses, reveals nothing at all. Not for the first time, Aziraphale wonders what his eyes are doing, what they look like now. If they’re fixed on Aziraphale. He has that strange prickling sensation over his skin he’d had before that rather suggests they are.

When Aziraphale leaves the court behind, assignment satisfactorily concluded, Shonagon gives him a series of parting presents, on behalf of her household. Largely consisting of sumptuous robes of blue and gold silks, one robe in particular stands out: black and red, embroidered with golden stars, it is lovely, and very obviously not meant for Aziraphale. “Thank you,” he says to her, “It’s lovely,” and she only smiles, and flutters her fan, and darts a glance over to Crowley, who is, coincidentally, departing court at the same time.

Aziraphale has always meant to present the robe to Crowley, of course, but at first it’s a few centuries before he sees him again, and then Crowley’s a knight errant, and brings up that absolutely vexing argument, and so it slips Aziraphale’s mind. The robe is still hanging in Aziraphale’s wardrobe, carefully pressed between the others. It occurs to him, every now and again, that he’d like to see Crowley wear it. Crowley will be delighted - Oh, Shonagon, he’ll say, with that little smile he gets when remembering particular humans he was fond of. I remember Shonagon. Whatever happened to her? 4 He and Shonagon, Aziraphale remembers, had gotten on like a house on fire. Shonagon had always had good taste. The robe will look exquisite, of course, paired with Crowley’s unmasked eyes.

Keep reading at:

https://archiveofourown.org/works/54704443

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

so like, we know animal youkai don't live that long (less than a century in most cases) then how is mouse sensei here one of the oldest teacher even back before hiyaki academy??

because the tesso isn't an animal youkai; it's a grudge youkai

the story of the tesso goes, during the reign of emperor shirakawa (1073-1087 CE) there was a monk named raigou who was the abbot of mii-dera

the emperor asked raigou to pray for the birth of an heir and promised him any reward, raigou complied, and he had a prince in 1074. but when raigou asked for a new ordination platform be built for his temple, rival temple enryaku-ji pressured the emperor and the emperor went back on his promise.

raigou went on a hunger strike to protest the emperor's broken promise and to drag the prince down. he died on the 100th day and later his ghost was seen near the prince, who died at age 4. raigou died so resentful that he became a vengeful spirit and transformed into a giant rat with a body hard as stone and teeth and claws hard as iron, and summoned a massive army of rats that poured through kyoto, up mount hiei, to wreak havoc at enryaku-ji, and nothing could stop tesso and his rat army until a shrine was built at mii-dera to appease him.

so there is actually a difference between the tesso and other animal youkai, in that the tesso is a specific story, and most animal youkai are "animals but weird"

(just kidding i dont actually know why mouse sensei built different. because its funny maybe?)

(this was a super abridged version of the tesso story read more here)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Monkey God

User @red-lights-burning asked if there was a connection between Sun Wukong and the monkey gods of Japan. They provided lovely info, which was split between two asks, but I decided to put everything together into a single post.

@red-lights-burning asked:

Japan has their own monkey protector named Masaru AKA Sannō Gongen, who was created back in the early 9th century by Tendai Buddhist sect founder Saichō shortly after he returned from China. So it makes me think if Monkey King was already a thing in the 800’s and if he was one of the inspirations for Masaru.

A description from onmarkproductions (a really great site for anyone curious about Japanese Buddhism and Shintō)

MASARU 神猿

Literally “Kami Monkey.” Masaru is the sacred monkey and protector of the Hie Shrine (aka Hie Jinja 日吉神社, Hiyoshi Taisha 日吉大社). The term “Masura” is often translated as “excel,” reflecting the belief that this sacred monkey can overcome all obstacles and prevail against all evil. Masaru is thus considered a demon queller par excellence (魔が去る・何よりも勝る). In the Heian era, Masaru (also translated “Great Monkey”) was invoked in Kōshin rituals to stop the three worms from escaping the body. Masaru also appears in Japanese scrolls used in Koushin rites.

Here’s a couple other descriptions

SANNŌ GONGEN 山王 権現 SARUGAMI 猿神 Fertility, Childbirth & Marriage

Monkeys are patrons of harmonious marriage and safe childbirth at some of the 3,800 Hie Jinja shrines in Japan. These shrines are often dedicated to Sannō Gongen 山王権現 (lit. = mountain king avatar), who is a monkey. Sannō is the central deity of Japan’s Tendai Shinto-Buddhist multiplex on Mt. Hiei (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto). The monkey is Sannou’s Shinto messenger (tsukai 使い) and Buddhist avatar (gongen 権現).

The monkey messenger is also known as Sarugami (猿神; literally “monkey kami”). Sarugami is the Shinto deity to whom the three monkeys (hear, speak, see no evil) are reportedly faithful. The monkey shrine at Nakayama Shrine 中山神社 in Tsuyama City, Okayama Prefecture, is dedicated to a red monkey named Sarugami, who blesses couples with children. According to shrine legends, the local people at one time offered human sacrifices (using females) to this deity. The shrine is mentioned in the Konjaku Monogatari-shu (今昔物語集), a collection of over 1000 tales from India, China, and Japan written during the late Heian Period (794-1192 AD). Sarugami, like Sannou Gongen, is also worshipped as the deity of easy delivery and child rearing. At such shrines, statues of the monkey deity are often decked in red bibs -- a color closely associated with fertility, children, and protection against evil forces and diseases like smallpox.

My answer:

I've read only a little bit about Japanese monkey gods. I previously referenced Sarugami in my article about the possible shamanic origins of primate-based boxing in China. Part of footnote #14 reads:

In Japan, monkeys were also associated with horses and healing via the warding of evil. Apart from monkeys being kept in stables like their Chinese counterparts, their fur was applied to the harnesses and quivers of Samurai because the warriors believed it gave them more control over their mounts. Furthermore, monkey body parts have been consumed for centuries as curative medicines, and their hides have even been stuffed to make protective amulets (kukurizaru) to ward off illness. Likewise, a genre of painting depicts divine monkeys (saru gami), messengers of the mountain deity, performing Da Nuo-like dances to ensure a good rice harvest (Ohnuki-Tierney, 1987, pp. 43-50)

The aforementioned article suggests a connection between monkeys and the Shang-Zhou Da Nuo (大儺 / 難; Jp: Tsuina, 追儺) ritual, an ancient, war-like, shamanic animal dance designed to drive away demonic illness and influences. The pertinent section reads:

It’s possible that the “twelve animals” of the Da Nuo exorcism refer to some precursor of the Chinese zodiacal animals (rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig). If true, monkey fur could have been among the animal products worn by the ritual army. After all, monkeys have long been associated with curing illness and expelling evil in East Asia. [14] A modern example of exorcists who don monkey fur are the shamans of the Qiang ethnic group of Sichuan. The Qiang worship monkeys as the source and savior of their sacred knowledge, as well as the progenitor of their people, the latter being a myth cycle common among ethnic groups of Tibet and southwestern China.

This is the only relevant info that comes to mind. But based on what I know, I would guess that Sun Wukong and the monkey gods of Japan draw upon the same cultural sources. I hope this helps.

Source:

Ohnuki-Tierney, E. (1987). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

#asks#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#Japanese Buddhism#Shinto#Buddhism#monkey god#shamanism#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The central chambers of the Taizōkai Mandara (胎蔵界曼荼羅), the Matrix World Mandala depicting hosts of buddhas, bodhisattvas, wrathful wisdom kings, and assorted other divinities & supernatural beings radiating from the cosmic buddha Dainichi Nyorai (大日如来) in the center, here all represented by their Sanskrit seed syllables in Siddhaṃ script

Color on silk dating to the 14th century, from the collection of Enryakuji Temple (延暦寺) on Mount Hiei (比叡山) north of Kyoto

#japanese art#buddhist art#曼荼羅#mandala#胎蔵界曼荼羅#taizokai mandala#taizokai#京都#kyoto#滋賀県#shiga prefecture#大津市#otsu#比叡山#hieizan#mount hiei#延暦寺#enryakuji#種子#shuji#seed syllable#梵字#bonji#天台宗#tendai

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

View of Lake Biwa from the Mount Hiei, Japan

Japanese vintage postcard

#japan#historic#the mount hiei#biwa#photo#briefkaart#vintage#sepia#photography#carte postale#postcard#hiei#postkarte#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#view#old#ephemera#postkaart#japanese#lake#mount

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

King’s rolling death cradle

I HOPE YOU'RE USING A FIGHT STICK OR SHOULDER BUTTONS ON PAD ✅✅✅✅✅✅✅✅✅

DP motion 1+4? Easy. 2 1 1+2+3? The 1+2+3 can be inconsistent on pad, but honestly, easy. 1+3 3+4 2+4 1+2 1+2+3? FICKLE AS A MAIDEN'S HEART ON THE GREEN PEAKS OF MOUNT HIEI DURING THE HEIAN PERIOD.

This was also a cheat code to get my cousin to fight me IRL when we were kids

19 notes

·

View notes