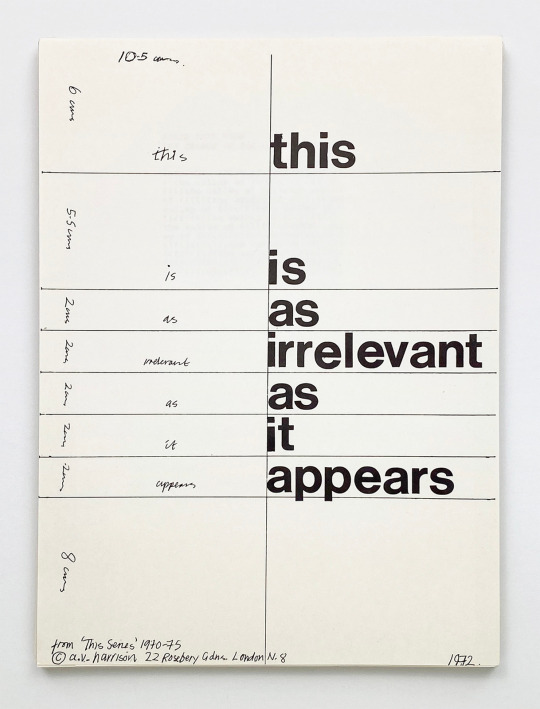

#Paula Adler

Text

DISCLAIMER WE DID NOT DRAW THESE. THESE ARE EDITED IMAGES FROM THE OUR LIFE: NOW AND FOREVER IN-GAME CHARACTER EDITOR

Mostly just posting these to this blog bc our main blog is mostly just for reblogs and such, we don't really post things there.

Since it's been confirmed there will be no more Our Life games after OLNF is finished, and because OLBA and OLNF are both themed around summer and fall respectively, we decided to take a crack at making our own Our Life game! (This is all, like, hypothetical, for the fun of coming up with ideas. This will never be a game in any real way.)

The characters from top to bottom are Ray Adler, Paula Reid, and Apricity Redlarch! They live in a town in northwest Michigan called Port Pearlescent, on the shore of Lake Michigan. Paula and the MC have lived there their whole lives, Ray is a new arrival (about a month or two before the prologue begins), and Apricity shows up during the prologue with her family!

(outdoor outfits on the left, indoor outfits on the right)

(also I only choose to put the setting where I put it because I don't know anything about the west coast lol)

Ray Adler is a kid from a warm southern state, who moved to Port Pearlescent with his mom (Ruby) and his pet box turtle named Champ. He prefers to stay indoors, but will still play outside to be with his friends. He doesn't like the cold, but some things he does like to do are draw and watch TV. Ray has blue hair he gets from his mom, and his hair quirk is that his hair changes slightly based on his mood (puffy and spiky if he's scared or angry, and sort of droopy if he's sad. It's subtle).

Paula Reid is a girl who loves to play outside, but she equally loves to have fun inside. She's lived in Port Pearlescent her whole life with her mom (Dahlia) and dad (Eli). Paula likes to play in the snow, making snow angels and snowmen and the like, and she loves to sit inside by a fire with hot cocoa and blankets. She has red hair, and her hair quirk is that her hair is a gradient from purpley~red to orangey~red.

Apricity Redlarch loves the cold and the outdoors. She loves winter sports, snowball fights, and walking the dogs her mom trains for a living. She came down from Canada with her 3 parents- her mom (Lucia Fontaine), her pa (Norton Redlarch), and her dad (Alpin Redlarch)- who love the cold and the outdoors a lot as well, but their daughter just might outshine them in that respect. Apricity has light blonde hair, and her hair quirk is that her hair is extra shiny.

Here are the families (not including Ray's pet turtle):

The Adler Family (not including the dad bc divorce lol. Also I haven't designed him or given him a name bc he just doesn't appear in the story. The divorce happened long before step 1 starts and is done and dusted. Ruby has full custody of her son. IK it's a bit similar to Cove and such but lalalalalalala)

The Reid Family

The Redlarch (& Fontaine) Family (I really really really have wanted to make characters w a poly family at some point. And this was a golden (or rather pearlescent teehee) opportunity.

Ok that's all I just felt like rambling about my goobers for a while. I have more to share but it's 1 am and I have work tmrw ok bye lalala

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voice Actors for SIGNALIS?

Three years ago I posted a list of voice actors whom I thought could play the various characters from the game VA-11 HALL-A: Cyberpunk Bartending Action.

I semi-recently composed a similar list albeit one that focuses on the characters from SIGNALIS instead. Here are the contents of said list:

Mary Elizabeth McGlynn as LSTR-512 "Elster."

Kara Eberle as Ariane Yeong.

Amanda "AmaLee" Lee (AKA Monarch) as Isolde "Isa" Itou.

Antonio Greco as ADLR-S2301 "Adler."

Jennifer Dawne Graveness as FLKR-S2301 "Falke"

Mary Kae Irvin Lindsey as the surviving STAR units.

Cristina Vee as the surviving EULR units.

Paula Jean Hixson as the lone surviving ARAR unit.

Talya Pulver-Lindqvist as STCR-S2307 "Sieben."

Dawn M. Bennett as KLBR-S2302 "Kolibri."

Samantha Dakin as MHNR-S2301 "Beo."

Also, as a bonus I could imagine Terri Brosius voicing over the various quotes from the various pieces of Eldritch Horror literature used in the game (IE: “Great holes secretly are digged where earth’s pores ought to suffice, and things have learnt to walk that ought to crawl.”)

8 notes

·

View notes

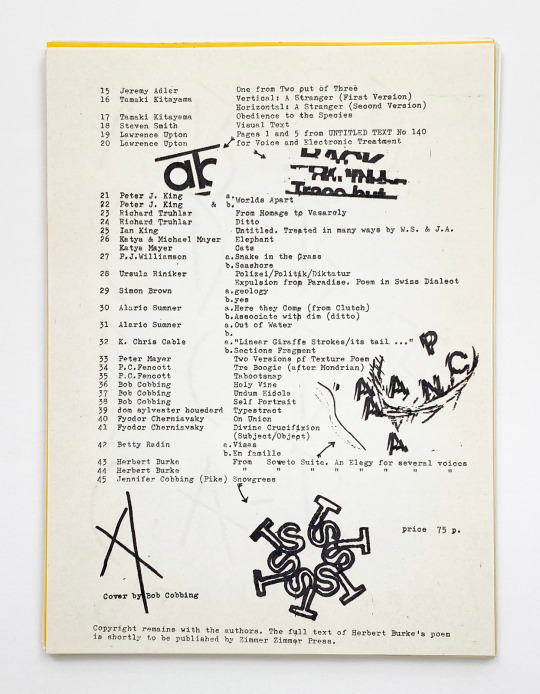

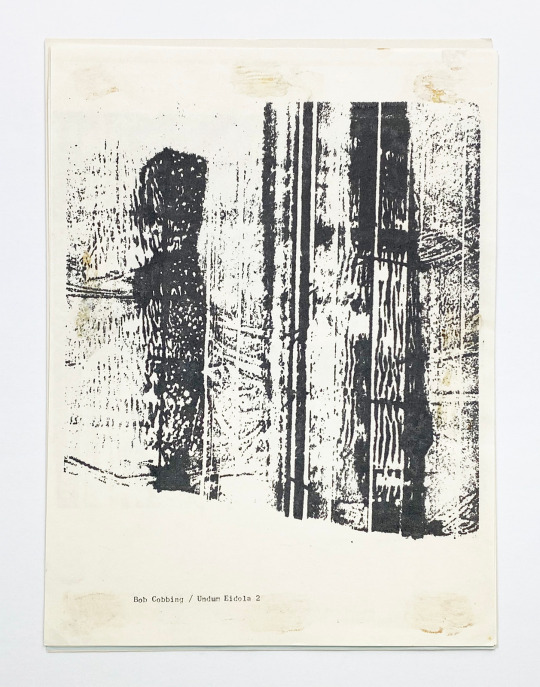

Photo

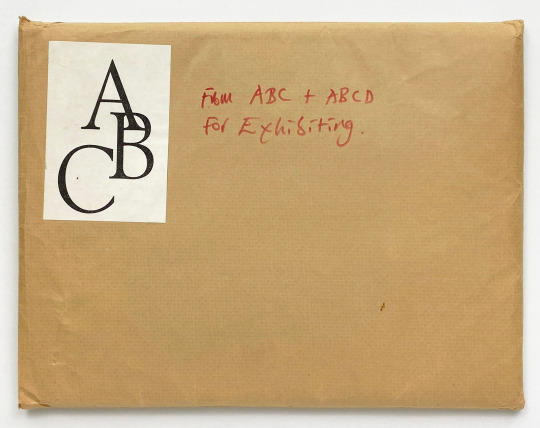

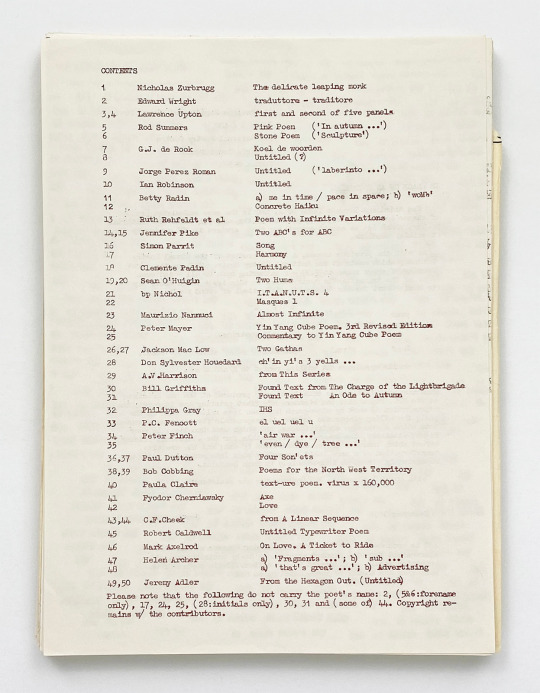

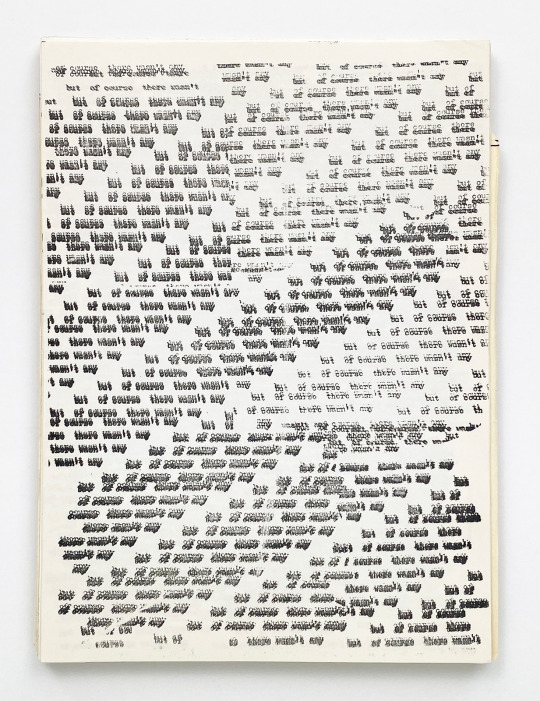

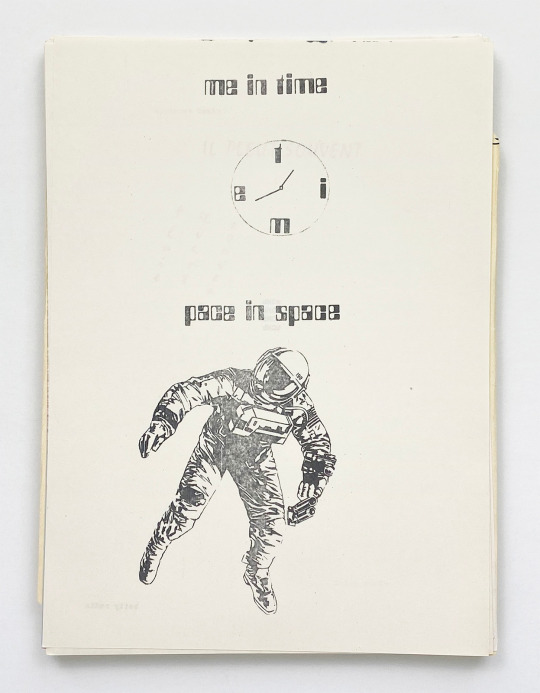

A [Abcd] – An Envelope Magazine of Visual Poetry, Edited by Jeremy Adler, The National Poetry Centre, London, 1975, First editions of 200 [The Idea of the Book, Portland, OR]. Feat. Nicholas Zurbrugg, Lawrence Upton, G. J. de Rook, Betty Radin, Jennifer Pike, bpNichol, Maurizio Nannucci, Jackson Mac Low, Dom Sylvester Houédard (dsh), P. C. Fencott, Paul Dutton, Bob Cobbing, Sylvia Finzi, Clemente Padín, Sean O’Huigin, Gayle Anderson, Paula Claire, Bill Bissett, Tamaki Kitamaya, et al.

#graphic design#art#poetry#concrete poetry#visual poetry#magazine#envelope#a abcd#jeremy adler#the national poetry centre#1970s

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fiction

Carrie stephen king x

the silence of the lambs Thomas harris x

The big nowhere James ellroy x

Speedboat Renata adler x

Giovanni's room James Baldwin x

Nightwood djuana barnes x

Troutfishing in America Richard brautigan x

Play as it lays joan didion x

Desperate characters Paula fox

The golden notebook Doris lessing x

The moviegoer walker Percy x

The man who loved children Christina stead

Time with children elizabeth tallent

Getting into death Thomas m. Disch

Where you'll find me and other stories anne bettie

God lives in st Petersburg Tom bissell

The zebra storyteller Spencer holt

The art of struggle Michel houellebecq

The boat nam le

Pigeon feathers and other stories john Updike

Everything ravaged, Everything burned wells tower

What narcism means to me Tony hoagland

Pity the bathtub it's embrace of human form mattea Harvey

Foucalt's pendulum Umberto eco

The canterville ghost Oscar wilde x

Los sorias Alberto laiseca

Pandemonium Darryl gregory

Hopscotch Julio cortazar

Igur nebli miquel de palol I muntanyola

Journey to the end of the night louis-ferdinand Celine

Point omega Don dellilo

Black Sunday Thomas harris

El jardi dels set crepuscles Miguel de palol I muntanyola

The street of crocodiles Bruno Schultz

Tabu Timo k. Mukka

Don't forget to breathe (migrations, volume I) ashim Shankar

El troiacord Miguel de Pollo I muntanyola

The egg head republic Arno schmidt

Rock star Jackie Collins

The lost scrapbook evan dara

Geek love Katherine dunn

Parley after life diy guide to death and other taxes Bobby Miller

God's mountain erri de Luca

Precarious: stories of love, sex and misunderstanding al riske

Where are the children mary Higgins Clark

Gryphon: new and selected story Charles baxter

Venus drive Sam lipsyte

The girl in the flammable skirt aimme bender

The chrysanthemums and other stories john Steinbeck

A clean well lighted place Ernest Hemingway

To build a fire and other stories jack london

Why I live at the p.o and other stories Eudora Welty

Appointment in sammara john O'Hara

Man in the dark Paul auster

The rocking horse winner d.h Lawrence x

House of sleeping beauties and other stories yasunari kawabata

Time's arrow martin amis

Blubber island Guillermo galvan

Darconville's cat Alexander theroux

Canti del caos Antonio moresco

Sam Dunn is dead: futurist novel Bruno corra

Lonesome dove Larry mcmurtry

1 note

·

View note

Text

Volvere Vento (Grupo Talvez Elizabeth)

Direção: Didio Gonçalves

Temporada no Teatro do Funil - 20, 21, 27 e 28 de outubro de 2017

Fotos: Paula Janssen

ELENCO: Amara Hartmann, Bárbara Arakaki, Beatriz Nauali, Didio Gonçalves e Paloma Rodrigues

DIREÇÃO: Didio Gonçalves

DIREÇÃO MUSICAL: Adler Henrique

DRAMATURGISTA: Renan Novais

OPERADOR DE SOM E PROJEÇÃO: Thayse Sborowski

OPERADOR DE LUZ: Sancler Pantano

DESENHO DE LUZ: Caio Coppoli

FIGURINO: Amara Hartmann

MAQUIAGEM: Lais Martins

0 notes

Text

A rainy day is coming—it's time to save

• Christy Turlington's back

• Paula Abdul's back

• Carmen Electra's back

• Josh Hartnett's back (Altered mental status, unspecified)

• Ashley Greene's back

• Marni Senofonte's back (Other acute osteomyelitis, right shoulder)

• Scotty McCreery's back (Unspecified fracture of fourth metacarpal bone, left hand)

• Cisco Adler's back

• Suri Cruise's back (Salter-Harris Type I physeal fracture of upper end of right fibula)

• Tony Parker's back (Abrasion, unspecified foot)

• Kim Kardashian's back

• Eva Longoria's back (Other stimulant abuse with stimulant-induced psychotic disorder)

• Ethan Hawke's back

• Lorde's back

• Sarah Palin's back

• Jada Pinkett Smith's back

• Matthew Perry's back

• Hilary Duff's back (Varicose veins of left lower extremity with inflammation)

• Frank Ocean's back

• Brooke Shields's back

• Denise Richards's back

• Curtis Stone's back

• Naomi Watts's back

• Julie Bowen's back

• Jesse Williams's back

0 notes

Text

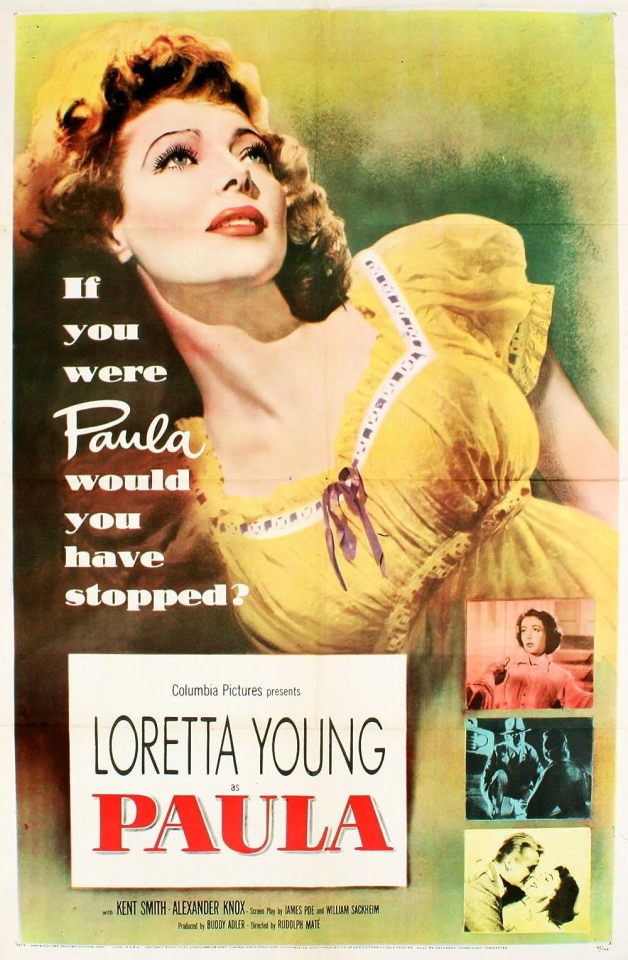

Day 29- Film: Paula

Release date: May 15th

Studio: Columbia

Genre: Noir

Director: Rudolph Mate

Producer: Buddy Adler

Actors: Loretta Young, Kent Smith, Alexander Knox, Tommy Rettig

Plot Summary: Paula just suffered her second miscarriage, and the doctors say she’ll never get pregnant again. One night while driving, she hits a little boy with her car. Circumstances conspire against her, and she leaves the scene, keeping everything a secret. Wracked with guilt, she seeks the boy out in the hospital- he suffered a brain injury and cannot speak. Paula and her husband take him in to give him full-time speech therapy, eventually adopting him. But what happens if anyone can connect her to the hit and run? Including little Davey?

My Rating (out of five stars): ***¾ ?

Until the last 10 minutes or so, this was a solid 4 star movie for me. The very end knocked a little bit off, just because it was kind of unbelievable and a bit unsatisfying. BUT I really really enjoyed this film! It’s one I definitely want to go back and re-watch.

The Good:

Loretta Young. She was just very good all around. Her acting was very affecting, and I cared about her character. I also liked that Young was around 40 years old here- I'm always in favor of more roles for older women!

Focusing on a woman dealing with infertility in the 1950s. The first 15 minutes was solely about the anguish Paula went through having lost a 2nd pregnancy and discovering she’d never have a biological baby. Even in 2023, infertility isn’t portrayed much in film, but in the 1950s? It was almost never talked about in an era where a woman’s entire purpose was seemingly to make babies. I can’t imagine how validating this movie might have been to a woman dealing with the issue in 1952.

This is a noir with a female protagonist! Those are so rare. Off the top of my head, Mildred Pierce is the only one that comes to mind! (Maybe Rebecca, if that counts?)

The little boy who played Davey. The film struck gold finding Tommy Rettig. For a child actor, his performance was incredible. He had to portray a kid who was learning to talk, and learning to trust people, and I don’t think anyone could have done it better. His eyes were so expressive, and yes he made me bawl at the end.

The story continually kept me interested, and I was fully invested in it.

I liked the character of Paula’s husband John. He was a good guy- very supportive to his wife. At first he didn’t want to adopt a little boy who couldn’t talk, fearing the stigmatization, but it did not take him long to totally fall in love with Davey.

The Bad:

The final 10 minutes or so. There were 2 abrupt shifts that I just didn’t buy- even though I cried my eyes out!

Weird doctors telling Paula to have a drink! One doctor, in his office, handed her a shot glass and told her it would make her feel better. The other one saw her at a party, said, “You look like you need a drink!” and handed her a big one. At least none of them told her to calm down by smoking a cigarette, which I have actually seen in at least one movie!

Yes, some of the coincidences of the film stretch believability- a woman who thinks she can’t have children hits an adorable little orphan boy with her car?- but... it is a movie, folks.

#project1952#1952#project1952 day 29#100 films of 1952#200 films of 1952#200 films of 1952 film 27#loretta young

0 notes

Text

..x cierto..hoy hubiera cumplido 63 años MICHAEL HUTCHENCE de INXS [IN EXCESS] q me dio 14_6_93 su cerveza MEXICANA CORONA en sala DIVINO AQUALUNG donde puso un TRONO en el ESCENARIO y Tim FARRISS su pua [solo cumplió 37 años pues al parecer se suicido o se axfisio accidentalmente haciendo una practica sadomasoquista masturbatoria tras estar bebiendo con una pareja en hotel Ritz de SIDNEY, llamar a Bob Geldof xq no dejaba a sus hijas ir con su madre Paula YATES muerta 3 años después de sobredosis..a SIDNEY junto a la hija q tuvo con HUTCHENCE y llamar a su 1era novia MICHELLE BENNET=1era dama de la derruida HAITI cuyo marido o presidente fue ASESINADO..pues como digo esto de tener SEXO dependiendo de una PAREJA es muy jodido aunque seas una Rockstar de la FALSA MORAL DEL DINERO..x esto y otras muchas razones es necesario los TEMPLOS de AMOR DE DIOS O de SEXO GRATIS Y LIBRE O SANO Y PURO]..

..también cumpleaños [58] STEVEN ADLER Batería original de GUNSNROSES con el q me fotografie 29_2_11 en el Pub UNDERWORLD de LONDRES [donde también fotografié al bajista DUFF MCKAGAN q se lanzo en solitario con cd BELIVE IN ME] junto al pub THE WORLD'S END..y el cual en su último concierto con GNR se cayó al subirse a la batería estrenando CIVIL WAR en un concierto de AYUDA A GRANJEROS

0 notes

Text

#NewRelease "SPRINGTIME IN MAGNOLIA BLOOM" by Paula Adler @AuthorAdler @InkslingerPR

#NewRelease “SPRINGTIME IN MAGNOLIA BLOOM” by Paula Adler @AuthorAdler @InkslingerPR

We are so excited to be bringing you the release of SPRINGTIME IN MAGNOLIA BLOOM by Paula Adler. If you love small town stories and family sagas, you don’t want to miss this new release!

About SPRINGTIME IN MAGNOLIA BLOOM

The MacInnes sisters, different in every way…except for how much they need each other.

Alyssa’s country music career was a dream come true. But lately, something’s off. The…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Same

#will and grace#eric mccormack#debra messing#will truman#grace adler#paula abdul#forever your girl#straight up

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selling some books to help me move!

I was looking through my collection and found some books I’d love to give new homes! I can only ship them if you’re in the US I’m sorry! I’m selling them to help me raise money so I can move out of state. It’s taken me a long time to finally start my journey on my own.

I’m 25 and visually disabled. It’s hard enough as it is just living day to day but living in a house where I’m just treated like a bank and a second parent to my siblings for years now has taken its toll on me.

I want to get out of here and be in a place where I’d be able to focus on myself and my needs instead of worrying about everyone else while I put myself on the back burner.

As of right now the money I get from my disability checks are going to my half of the rent, the bills I pay, the food I buy for myself and my family and my phone bill. I can hardly save anything I get every month because theres always something that comes up that I have to help out if my family doesn’t have enough.

Any money I’d be getting from selling these books will go towards what I need for the move. This is a huge step for me, I might be terrified but I can’t stand letting myself be taken advantage of anymore.

If you’re interested in any of them, please message me and I can send you more pictures of the ones you’d like with the summary of the story if you want to know more about the book itself. Most of these books are in very good conditions like brand new conditions, some are faded/slightly torn in places since I’ve had them for years but they’re perfectly fine. I will send you a link to my PayPal once we agree on the purchase and will send you the book the next day and I’ll send you the tracking number so you can keep track of your package as well.

The prices are 2 or 5 dollars more than the actual book so can be able to cover the shipping costs! So the prices I’m putting are total price including the shipping cost already!

Please only message me about buying a book if you’re comfortable giving me your address or P.O. box!

Reblogs will help me a ton if you aren’t able to buy a book! Thank you for taking the time to read all this and being able to help me in any way!

Hard Cover of Zen and Xander Undone by Amy Kathleen Ryan- $17

Hard Cover of Only The Good Spy Young by Ally Carter-$17

Hard Cover of Sweet 15 by Emily Adler & Alex Echevarria- $17

Hard Cover of Devil’s Kiss by Sarwat Chadda- $20

Hard Cover of Torn by Stephanie Guerra- $20

Paperback of Wicked Lovely by Melissa Marr- $15

Paperback of Into The Darkest Corner by Elizabeth Haynes- $16

Paperback of Darkly Dreaming Dexter by Jeff Lindsay- $20

Hard Cover of Losing It by Erin Fry- $20

Hard Cover of Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell- $15

Paperback of Ruined by Paula Morris- $8

Paperback of Is it Wrong To Pick Up Girls In A Dungeon? by Fujino Omori- $15

Paperback of The Ghost and The Goth by Stacey Kade- $6

Paperback of Vol.1 of Peach Girl by Miwa Ueda- $10

Paperback of the first 5 Vols. of Nosatsu Junkie by Ryoko Fukuyama- $50

Paperback complete series of Wish by Clamp- $45

Paperback of the first 3 Vols. of Dream Saga by Megumi Tachikawa- $35

Paperback of Vols. 1 and 5 of Black Butler by Yana Toboso- $25

Paperback of first 3 Vols. of Aishiteruze Baby by Yoko Maki- $30

Paperback of the first 14 Vols. of Skip-Beat by Yoshiki Nakamura- $155 (i know vols 11 and 12 should be switched in the picture but its all first 14 volumes)

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

die jungen ärzte + mbti

#die jungen ärzte#in aller freundschaft#roy peter link#paula schramm#mirka pigulla#jane chirwa#mike adler#in aller freundschaft die jungen ärzte#gifs#shows

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep returning to Renata Adler’s introduction to Canaries in the Mineshaft (2001), a moving and revealing piece on how the New York Times works. I’ve sent excerpts to a few people, but it’s worth reading in full.

It’s not online anywhere, so I’m posting it here, with Adler’s 12,500 words on the New York Times and what it can do to the people it covers:

Along with every other viewer of television during Operation Desert Storm, the Gulf War of 1991, I believed that I saw, time after time, American Patriot missiles knocking Iraqi Scuds out of the sky. Every major television reporter obviously shared this belief, along with a certainty that these Patriots were offering protection to the population of Israel—which the Desert Storm alliance, for political reasons, had kept from active participation in the war. Commentators actually cheered, with exclamations like “Bull’s-eye! No more Scud!” at each such interception by a Patriot of a Scud. Weeks earlier, I had read newspaper accounts of testimony before a committee of the Congress by a tearful young woman who claimed to have witnessed Iraqi soldiers enter Kuwaiti hospitals, take babies out of their incubators, hurl the newborns to the floor, and steal the incubators. I believed this, too.

Only much later did I learn that not a single Patriot effectively hit a single Scud. The scenes on television were in fact repetitions of images from one film, made by the Pentagon in order to persuade Congress to allocate more money to the Patriot, an almost thirty-year-old weapon designed, in any case, not to destroy missiles but to intercept airplanes. In his exuberance, a high military official announced that Patriots had even managed to destroy “eighty-one Scud launchers”—interesting not only because the total number of Scud launchers previously ascribed to Iraq was fifty, but also because there is and was no such thing as a “Scud launcher.” The vehicles in question were old trucks, which had broken down.

What was at issue, in other words, was not even pro-American propaganda, which could be justified in time of war. It was domestic advertising for a product—not just harmlessly deceptive advertising, either. The Patriots, as it turned out, did more damage to the allied forces, and to Israel, than if they had not been used at all. The weeping young woman who had testified about the incubator thefts turned out to be the fifteen-year-old daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador to Washington; she had not, obviously, witnessed any such event. Whatever else the Iraqi invaders and occupiers may have done, this particular incident was a fabrication—invented by an American public relations firm in the employ of the Kuwaiti government.

During Operation Desert Storm itself, the American press corps, as it also turns out, accepted an arrangement with the U.S. military, whereby only a “pool” of journalists would be permitted to cover the war directly. That pool went wherever the American military press officer chose to take it. Nowhere near the front, if there was a front. Somehow, the pool and its military press guides often got lost. When other reporters, trying to get independent information, set out on their own, members of the pool actually berated them for jeopardizing the entire news-gathering arrangement.

It would have been difficult to learn all this, or any of it, from the press. I learned it from a very carefully researched and documented book, Second Front: Censorship and Propaganda in the Gulf War, by John R. MacArthur. The book, published in 1992, was well enough reviewed. But it was neither prominently reviewed nor treated as “news” or even information. A review, after all, is regarded only as a cultural and not a real—least of all a journalistic—event. It was not surprising that the Pentagon, after its experience in Vietnam, should want to keep the press at the greatest possible distance from any war. It was not surprising, either, that reporters, having after all not that much choice, should submit so readily to being confined to a pool, or even that reporters in that pool should resent any competitor who tried to work outside it. This is the position of a favored collaborator in any bureaucratic and coercive enterprise.

What was, if not surprising, a disturbing matter, and a symptom of what was to come, was this: The press did not report the utter failure of the Patriot, nor did it report the degree to which the press itself, and then its audience and readership, had been misled. This is not to suggest that the press, out of patriotism or for any other reason, printed propaganda to serve the purposes of the government—or even that it would be unworthy to do so. But millions of Americans surely still believe that Patriots destroyed the Scuds, and in the process saved, or at least defended, Israel. There seemed, in this instance, no reason why the press, any more than any person or other institution, should be eager to report failures of its own.

Almost all the pieces in this book have to do, in one way or another, with what I regard as misrepresentation, coercion, and abuse of public process, and, to a degree, the journalist’s role in it. At the time of the Vietnam War, it could be argued that the press had become too reflexively adversarial and skeptical of the policies of government. Now I believe the reverse is true. All bureaucracies have certain interests in common: self-perpetuation, ritual, dogma, a reluctance to take responsibility for their actions, a determination to eradicate dissent, a commitment to a notion of infallibility. As I write this, the Supreme Court has, in spite of eloquent and highly principled dissents, so far and so cynically exceeded any conceivable exercise of its constitutional powers as to choose, by one vote, its own preferred candidate for President. Some reporters, notably Linda Greenhouse of the New York Times, have written intelligently and admirably about this. For the most part, however, the press itself has become a bureaucracy, quasi-governmental, and, far from calling attention to the collapse of public process, in particular to prosecutorial abuses, it has become an instrument of intimidation, an instrumentality even of the police function of the state.

Let us begin by acknowledging that, in our public life, this has been a period of unaccountable bitterness and absurdity. To begin with the attempts to impeach President Clinton. There is no question that the two sets of allegations, regarding Paula Jones and regarding Whitewater, with which the process began could not, as a matter of fact or law or for any other reason, constitute grounds for impeachment. Whatever they were, they preceded his presidency, and no President can be impeached for his prior acts. That was that. Then the Supreme Court, in what was certainly one of the silliest decisions in its history, ruled that the civil lawsuit by Paula Jones could proceed without delay because, in spite of the acknowledged importance of the President’s office, it appeared “highly unlikely to occupy any substantial amount of his time.” In 1994 a Special Prosecutor (for some reason, this office is still called the Independent Counsel) was appointed to investigate Whitewater—a press-generated inquiry, which could not possibly be material for a Special Prosecutor, no matter how defined, since it had nothing whatever to do with presidential conduct. Nonetheless, the first Special Prosecutor, Robert Fiske, investigated and found nothing. A three-judge panel, appointed, under the Independent Counsel statute, by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, fired Fiske. As head of the three-judge panel, Rehnquist had passed over several more senior judges, to choose Judge David Bryan Sentelle.

Judge Sentelle consulted at lunch with two ultra-right-wing senators from his own home state of North Carolina: Lauch Faircloth, who was convinced, among other things, that Vincent Foster, a White House counsel, had been murdered; and Jesse Helms, whose beliefs and powers would not be described by anyone as moderate. Judge Sentelle appointed as Fiske’s successor Kenneth W. Starr. North Carolina is, of course, a tobacco-growing state. Kenneth Starr had been, and remained virtually throughout his tenure as Special Prosecutor, a major, and very highly paid, attorney for the tobacco companies. He had also once drafted a pro bono amicus brief on behalf of Paula Jones.

The Office of Special Prosecutor—true conservatives said this from the first—had always been a constitutional abomination. To begin with, it impermissibly straddled the three branches of government. If President Nixon had not been in dire straits, he would never have permitted such an office, in the person of Archibald Cox, to exist. If President Clinton had not been sure of his innocence and—far more dangerously—overly certain of his charm, he would never have consented to such an appointment.

The press, however, loves Special Prosecutors. They can generate stories for each other. That something did not happen is not a story. That something does not matter is not a story. That an anecdote or an accusation is unfounded is not a story. There is this further commonality of interest. Leaks, anonymous sources, informers, agents, rumormongers, appear to offer stories—and possibilities for offers, pressures, threats, rewards. The journalist’s exchange of an attractive portrayal for a good story. There we are. The reporter and the prosecutor (the Special Prosecutor, that is; not as often the genuine prosecutor) are in each other’s pockets.

Starr did not find anything, either. Certainly no crime. He sent his staff to Little Rock, generated enormous legal expenses for people interviewed there, threw one unobliging witness (Susan McDougal) into jail for well over a year, indicted others (Webster Hubbell, for example) for offenses unrelated to the Clintons, convicted and jailed witnesses in hopes of getting testimony damaging to President Clinton, tried, after the release of those witnesses, to jail them again to get such testimony. Still no crime. So his people tried to generate one. This is not unusual behavior on the part of prosecutors going after hardened criminals: stings, indictments of racketeers and murderers for income tax offenses. But here was something new. Starr’s staff, for a time, counted heavily on sexual embarrassment: philandering, Monica Lewinsky. They even had a source, Linda Tripp. Ms. Tripp had testified for Special Prosecutor Fiske and later for Starr. She had testified in response to questions from her sympathetic interlocutor Senator Lauch Faircloth before Senator D’Amato’s Whitewater Committee. She had testified to agents of the FBI right in the Special Prosecutor’s office at least as early as April 12, 1994. An ultra-right-wing Republican herself, she not only believed White House Counsel Vincent Foster was murdered, she claimed to fear for her own life. She somehow had on the wall above her desk at the Pentagon, where her desk adjoined Monica Lewinsky’s, huge posters of President Clinton—which, perhaps not utterly surprisingly, drew Ms. Lewinsky’s attention. Somehow, in the fall of 1996 Ms. Tripp found herself eliciting, and taping, confidences from Ms. Lewinsky. In January of 1997, Ms. Tripp—who by her own account had previously abetted another White House volunteer, Kathleen Willey, in making sexual overtures to President Clinton—counseled Ms. Lewinsky to try again to visit President Clinton. By the end of February 1997, Ms. Lewinsky, who had not seen the President in more than eleven months, managed to arrange such a visit. Somehow, that visit was the only one in which she persuaded the President to ejaculate. Somehow, adept as Ms. Lewinsky claimed to be at fellatio, semen found its way onto her dress. Somehow, Ms. Tripp persuaded Ms. Lewinsky, who perhaps did not require much persuasion, to save that dress. Somehow, the Special Prosecutor got the dress. And somehow (absurdity of absurdities), there was the spectacle of the Special Prosecutor’s agents taking blood from the President to match the DNA on a dress.

Now, whatever other mistakes President Clinton may have made, in this or any other matter, he, too, had made utterly absurd mistakes of constitutional proportions. He had no obligation at all to go before the grand jury. It was a violation of the separation of powers and a mistake. Once again, he may have overestimated his charm. Charm gets you nowhere with prosecutors’ questions, answered before a grand jury under oath. And of course, Mr. Starr had managed to arrange questions—illegally, disingenuously, at the absolute last minute—which were calculated to make the President testify falsely at his deposition in the case of Paula Jones. Whether or not the President did testify falsely, the notion that “perjury” or even “obstruction of justice” in such a case could rise to the level of “Treason, Bribery or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” the sole constitutional grounds for impeachment, had no basis in history or in law.

One need not dwell on every aspect of the matter to realize this much: As sanctimonious as lawyers, congressmen, and even judges may be, most legal cases are simply not decided on arcane legal grounds. Most turn on conflicting evidence, conflicting testimony. And this conflict cannot, surely, in every case or even in most cases, be ascribed either to Rashomon phenomena or to memory lapses. In most cases—there is no other way to put it—one litigant or the other, and usually both, are lying. If this were to be treated as “perjury” or “obstruction of justice,” then, alas, most losers in litigation would be subject to indictment. Anyone who has studied grounds for impeachment at all knows that “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” refers, in any event, only to crimes committed in the President’s official capacity and in the actual conduct of his office.

And now the press. Perhaps the most curious phenomenon in the recent affinity of the press with prosecutors has been a reversal, an inversion so acute that it passes any question of “blaming the victim.” It actually consists in casting persecutors as victims, and vilifying victims as persecutors. The New York Times is not alone in this, but it has been, until recently, the most respected of newspapers, and it has been, of late, the prime offender. A series of recent events there gives an indication of what is at stake.

In a retreat in Tarrytown, in mid-September, Joseph Lelyveld—in his time a distinguished reporter, now executive editor of the Times—gave a speech to eighty assembled Times newsroom editors, plus two editors of other publications, The New Yorker and Newsday. The ostensible subject of the retreat was “Competition.” Mr. Lelyveld’s purpose, he said, was to point out “imperfections in what I proudly believe to be the best New York Times ever—the best written, most consistent, and ambitious newspaper Times readers have ever had.” This was, in itself, an extraordinary assertion. It might have been just a mollifying tribute, a prelude to criticism of some kind. And so it was.

“I’m just driven by all the big stuff we’ve accomplished in recent years—our strong enterprise reporting, our competitive edge, our successful recruiting, our multimedia forays, our sheer ambition,” Lelyveld went on, “to worry” about “the small stuff,” particularly “the really big small stuff.” “I especially want to talk to you,” he said, “about corrections, and in particular, the malignancy of misspelled names, which, if you haven’t noticed, has become one of the great themes of our Corrections column.”

He might have been joking, but he wasn’t. “Did you know we’ve misspelled Katharine Graham’s name fourteen times? Or that we've misspelled the Madeleine in Madeleine Albright forty-nine times—even while running three corrections on each? … So far this year … there have been a hundred and ninety-eight corrections for misspelled given names and surnames, the overwhelming majority easily checkable on the Internet. … I want to argue that our commitment to being excellent and reliable in these matters is as vital to the impression we leave on readers, and the service we perform for them, as the brilliant things we accomplish most days on our front page and on our section-front displays.”

Lelyveld recalled the time, thirty years ago, when he had first come to the newspaper (a better paper, as it happens, an incomparably better paper, under his predecessors, whom present members of the staff tend to demonize). “Just about everything else we do today, it seems to me, we do better than they did then.” But, in view of “the brilliant things we accomplish most days” (”We don’t just claim to be a team. We don’t just aspire to be a team. Finally, I think we can say, we function as a team. We are a team”), he did want to talk about what he regarded as a matter of some importance: “Finally … there’s the matter of corrections (I almost said the ‘festering matter’ of corrections). As I see it, this is really big small stuff.”

A recent correction about a photo confusing monarch and queen butterflies, he said, might seem amusing—”amusing if you don’t much mind the fact that scores of lepidopterists are now likely to mistrust us on areas outside their specialty.”

And that, alas, turned out to be the point. This parody, this misplaced punctiliousness, was meant to reassure readers—lepidopterists, whomever—that whatever else appeared in the newspaper could be trusted and was true. Correction of “malignant” misspellings, of “given names and surnames,” middle initials, captions, headlines, the “overwhelming majority” of which, as Lelyveld put it, would have been “easily checkable on the Internet” was the Times’ substitute for conscience, and the basis of its assurance to readers that in every other respect it was an accurate paper, better than it had ever been, more worthy of their trust. Stendhal, for instance, had recently been misspelled, misidentified, and given a first name: Robert. “A visit to Amazon.com, just a couple of clicks away, could have cleared up the confusion.” Maybe so.

The trivial, as it happens often truly comic, corrections, persist, in quantity. The deep and consequential errors, inevitable in any enterprise, particularly those with deadlines, go unacknowledged. By this pedantic travesty of good faith, which is, in fact, a classic method of deception, the Times conceals not just every important error it makes but that it makes errors at all. It wants that poor trusting lepidopterist to think that, with the exception of this little lapse (now corrected), the paper is conscientious and infallible.

There exists, to this end, a wonderful set of locutions, euphemisms, conventions, codes, and explanations: “misspelled,” “misstated,” “referred imprecisely,” “referred incorrectly,” and recently—in some ways most mystifyingly—”paraphrase.”

On September 19, 2000, “An article on September 17 about a program of intellectual seminars organized by Mayor Jerry Brown of Oakland, California, referred imprecisely to some criticisms of the series. The terms ‘Jerrification’ and ‘pointy-headed table talk’ were the article’s paraphrase of local critics, not the words of Willa White, president of the Jack London Association.”

On October 5, 2000, “A news analysis yesterday about the performances of Vice President Al Gore and Gov. George W. Bush of Texas in their first debate referred imprecisely in some copies to a criticism of the candidates. The observation that they ‘took too much time niggling over details’ was a paraphrase of comments by former Mayor Pete Flaherty of Pittsburgh, not a quotation.”

On November 9, 2000, “An article on Sunday about the campaign for the Senate in Missouri said the Governor had ‘wondered’ about the decision of the late candidate’s wife to run for the Senate. But he did not use the words ‘I’m bothered somewhat by the idea of voting for a dead person’s wife, simply because she is a widow.’ That was a paraphrase of Mr. Wilson’s views and should not have appeared in quotation marks.”

On December 16, 2000, “Because of an editing error, an article yesterday referred erroneously to a comment by a board member,” about a recount. “‘A man has to do what a man has to do’ was a paraphrase of Mr. Torre’s views and should not have appeared in quotation marks.”

Apart from the obvious questions—What is the Times’ idea of “paraphrase"? What were the actual words being paraphrased? What can “Jerrification,” “pointy-headed table talk,” “niggling,” and even “A man has to do what a man has to do” possibly be paraphrases of—what purpose is served by these corrections? Is the implication that all other words, in the Times, attributed in quotation marks to speakers are accurate, verbatim quotations? I’m afraid the implication is inescapably that. That such an implication is preposterous is revealed by the very nature of these corrections. There is no quotation of which “Jerrification” and the rest can possibly be a paraphrase. Nor can the reporter have simply misheard anything that was actually said, nor can the result be characterized as having “referred imprecisely” or “referred erroneously,” let alone be the result of “an editing error.”

It cannot be. What is at issue in these miniscule corrections is the Times’ notion of what matters, its professionalism, its good faith, even its perception of what constitute accuracy and the truth. The overriding value is, after all, to allay the mistrust of readers, lepidopterists, colleagues. Within the newspaper, this sense of itself—trust us, the only errors we make are essentially typos, and we correct them; we never even misquote, we paraphrase—appears even in its columns.

In a column published in the Times on July 20, 2000, Martin Arnold of the Arts/Culture desk, for example, wrote unhesitatingly that, compared with book publishing, “Journalism has a more rigorous standard: What is printed is believed to be true, not merely unsuspected of being false. The first rule of journalism,” he wrote, “is don’t invent.”

“Except in the most scholarly work,” Mr. Arnold went on, “no such absolutes apply to book publishing. … A book writer is … not subject to the same discipline as a news reporter, for instance, who is an employee and whose integrity is a condition of his employment … a newspaper … is a brand name, and the reader knows exactly what to expect from the brand.” If book publishers, Mr. Arnold concluded, “seem lethargic” about “whether a book is right or wrong, it maybe [sic] because readers will cut books slack they don’t give their favorite newspaper.”

In this wonderful piece of self-regarding fatuity, Mr. Arnold has expressed the essence of the “team’s” view of its claim: The Times requires no “slack.” It readily makes its own corrections:

The Making Books column yesterday misspelled the name of the television host. … She is Oprah Winfrey, not Opra.

An article about Oprah Winfrey’s interview with Al Gore used a misspelled name and a non-existent name for the author of The Red and the Black. . . . The pen name is Stendhal, not Stendahl; Robert is not part of it.

The Advertising column in Business on Friday misspelled the surname of a singer and actress. … She is Lena Horne, not Horn.

An article about an accident in which a brick fell from a construction site atop the YMCA building on West 63rd Street, slightly injuring a woman, included an erroneous address from the police for the building near which she was standing. It was 25 Central Park West. (There is no No. 35). Because of an editing error, the Making Books column on Thursday … misstated the name of the publisher of a thriller by Tom Clancy. It is G. P. Putnam, not G. F.

An article on Monday about charges that Kathleen Hagen murdered her parents, Idella and James Hagen, at their home in Chatham Township, N.J., misspelled the street where they lived. It is Fairmount Avenue, not Fairmont.

And so on. Endlessly.

What is the reasoning, the intelligence, behind this daily travesty of concern for what is truthful? Mr. Arnold has the cant just about right. “Don’t invent.” (Pointy-headed table talk? Jerrification? Niggling? Paraphrase?) “Discipline”? “Integrity”? “Rigorous standard”? Not in a long time. “A newspaper is a brand name, and the reader knows exactly what to expect from the brand.” Well, there is the problem. Part of it is the delusion of punctilio. But there is something more. Every acknowledgment of an inconsequential error (and they are never identified as reporting errors, only errors of “editing,” or “production,” or “transmission,” and so forth), in the absence of acknowledgment of any major error, creates at best a newspaper that is closed to genuine inquiry. It declines responsibility for real errors, and creates as well an affinity for all orthodoxies. And when there is a subject genuinely suited to its professional skills and obligations, it abdicates. It almost reflexively shuns responsibility and delegates it to another institution.

Within a few weeks of its small retreat at Tarrytown, the Times, on two separate occasions, so seriously failed in its fundamental journalistic obligations as to call into question not just its judgment and good faith but whether it is still a newspaper at all. The first occasion returns in a way to the subject with which this introduction began: a pool.

On election night, television, it was generally acknowledged, had made an enormous error by delegating to a single consortium, the Voter News Service, the responsibility for both voter exit polls and calling the election results. The very existence of such a consortium of broadcasters raised questions in anti-trust, and VNS called its results wrongly, but that was not the point. The point was that the value of a free press in our society was always held to lie in competition. By a healthy competition among reporters, from media of every political point of view, the public would have access to reliable information, and a real basis on which to choose. A single monolithic, unitary voice, on the other hand, is anathema to any democratic society. It becomes the voice of every oppressive or totalitarian system of government.

The Times duly reported, and in its own way deplored, the results of the VNS debacle. Then, along with colleagues in the press (the Washington Post, CNN, the Wall Street Journal, ABC, AP, the Tribune Company), it promptly emulated it. This new consortium hired an organization called the National Opinion Research Center to undertake, on its behalf, a manual recount of Florida ballots for the presidential election. The Miami Herald, which had already been counting the votes for several weeks, was apparently the only publication to exercise its function as an independent newspaper. It refused to join the consortium. It had already hired an excellent accounting firm, BDO Seidman, to assist its examination of the ballots. NORC, by contrast, was not even an auditing firm but a survey group, much of whose work is for government projects.

The Times justified its (there seems no other word for it) hiding, along with seven collegial bureaucracies, behind a single entity, NORC, on economic grounds. Proceeding independently, it said, would have cost between $500,000 and $1 million. The Times, it may be noted, had put fifteen of its reporters to work for a solid year on a series called “Living Race in America.” If it had devoted just some of those resources and that cost to a genuine, even historic, issue of fact, it would have exercised its independent competitive function in a free society and produced something of value. There seems no question that is what the Times under any previous publisher or editors would have done.

In refusing to join the consortium, the Miami Herald said the recount was taking place, after all, “in our own back yard.” It was, of course, America’s backyard, and hardly any other members of the press could be troubled with their own resources and staff to enter it.

The second failure of judgment and good faith was in some ways more egregious. In late September of 2000 there was the Times’ appraisal of its coverage (more accurately, the Times’ response to other people’s reaction to its coverage) of the case of Wen Ho Lee.

For some days, there had been rumors that the Times was going to address in some way its coverage of the case of Wen Ho Lee, a sixty- year-old nuclear scientist at Los Alamos who had been held, shackled and without bail, in solitary confinement, for nine months—on the basis, in part, of testimony, which an FBI agent had since admitted to be false, that Lee had passed American nuclear secrets to China; and testimony, also false, that he had flunked a lie detector test about the matter; and testimony, false and in some ways most egregious, that granting him bail would constitute a “grave threat” to “hundreds of millions of lives” and the “nuclear balance” of the world. As part of a plea bargain, in which Lee acknowledged a minor offense, the government, on September 14, 2000, withdrew fifty-eight of its fifty-nine original charges. The Federal District Judge, James A. Parker, a Reagan appointee, apologized to Lee for the prosecutorial conduct of the government.

The Times had broken the story of the alleged espionage on March 6 of 1999, and pursued it both editorially and in its news columns for seventeen months. A correction, perhaps even an apology, was expected to appear in the Week in Review section, on Sunday, September 24, 2000. Two Times reporters flew up from Washington to register objections. The piece, whatever it had been originally, was edited and postponed until the following Tuesday. (The Sunday Times has nearly twice the readership of the daily paper.) Readers of the Week in Review section of Sunday, September 24, 1999, however, did find a correction. It was this:

An Ideas & Trends article last Sunday about a trend toward increasing size of women’s breasts referred incorrectly to the actress Demi Moore. She underwent breast augmentation surgery, but has not had the implants removed.

In the meantime, however, on Friday, September 22, 2000, there appeared an op-ed piece, “No One Won the Whitewater Case,” by James B. Stewart, in which the paper’s affinity with prosecution—in particular the Special Prosecutor—and the writer’s solidarity with the Times reporters most attuned to leaks from government accusers found almost bizarre expression. Stewart, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and the author of Blood Sport, wrote of Washington, during the Clinton administration, as a “culture of mutual political destruction.” In what sense the “destruction” could be deemed “mutual” was not entirely clear. Mr. Stewart praised an article about Whitewater, on March 8, 1992, written by Jeff Gerth (one of the original writers of the Wen Ho Lee pieces) as “a model of investigative reporting.” He wrote of “rabid Clinton haters” who believed that Vincent Foster was “murdered, preferably by Hillary Clinton herself”; he added, however, the Clintons “continued to stonewall,” providing “ample fodder for those opposed to the President.”

“The Independent Counsel’s mission,” he wrote, “was to get to the bottom of the morass.” No, it wasn’t. What morass? Then came this formulation:

Kenneth Starr and his top deputies were not instinctive politicians, and they became caught up in a political war for which they were woefully unprepared and ill-suited. The White House and its allies relentlessly attacked the Independent Counsel for what they thought were both illegal and unprincipled tactics, like intimidating witnesses and leaking to the press. Mr. Starr has been vindicated in the courts in nearly every instance, and he and his allies were maligned to a degree that will someday be seen as grossly unfair.

One’s heart of course goes out to these people incarcerating Susan McDougal; illegally detaining and threatening Monica Lewinsky; threatening a witness who refused to lie for them, by implying that her adoption of a small child was illegal; misleading the courts, the grand jury, the press, the witnesses about their actions. Persecuted victims, these prosecutors—”caught up,” “woefully unprepared,” “relentlessly attacked,” “maligned.”

The investigation unfolded with inexorable logic that made sense at every turn, yet lost all sight of the public purpose it was meant to serve. Mr. Starr’s failure was not one of logic or law but of simple common sense.

Quite apart from whatever he means by “public purpose,” what could Mr. Stewart possibly mean by “common sense”?

From early on, it should have been apparent that a criminal case could never be made against the Clintons. Who would testify against them?

Who indeed? Countless people, as the Times checkers, if it had any, might have told him—alleging rape, murder, threats, blackmail, drug abuse, bribery, and abductions of pet cats.

“The investigation does not clear the Clintons in all respects,” Mr. Stewart wrote, as though clearing people, especially in all respects, were the purpose of prosecutions. “The Independent Counsel law is already a casualty of Whitewater and its excesses.” What? What can this possibly mean? What “it,” for example, precedes “its excesses”? Whitewater’s excesses?

But as long as a culture of mutual political destruction reigns in Washington, the need for some independent resolution of charges against top officials, especially the President, will not go away. [A reigning culture of mutual destruction evidently needs another Special Prosecutor, to make charges go away.] After all, we did get something for our nearly $60 million. The charges against the Clintons were credibly resolved.

An extraordinary piece, certainly. Four days later, on Tuesday, September 26, 2000, the Times ran its long-awaited assessment, “From the Editors.” It was entitled “The Times and Wen Ho Lee.”

Certainly, the paper had never before published anything like this assessment. A break with tradition, however, is not an apology. What the Times did was to apportion blame elsewhere, endorse its own work, and cast itself as essentially a victim, having “attracted criticism” from three categories of persons: “competing journalists,” “media critics,” and “defenders of Dr. Lee.” Though there may, in hindsight, have been “flaws”—for example, a few other lines of investigation the Times might have pursued, “to humanize” Dr. Lee—the editors seemed basically to think they had produced what Mr. Stewart, in his op-ed piece, might have characterized as “a model of investigative reporting.” Other journalists interpreted this piece one way and another, but to a reader of ordinary intelligence and understanding there was no contrition in it. That evidently left the Times, however, with a variant of what might be called the underlying corrections problem: the lepidopterist and his trust. “Accusations leveled at this newspaper,” the editors wrote, “may have left many readers with questions about our coverage. That confusion—and the stakes involved, a man’s liberty and reputation—convince us that a public accounting is warranted.” The readers’ “confusion” is the issue. The “stakes,” in dashes, are an afterthought.

“On the whole,” the public accounting said, “we remain proud of work that brought into the open a major national security problem. Our review found careful reporting that included extensive cross-checking and vetting of multiple sources, despite enormous obstacles of official secrecy and government efforts to identify the Times’ sources.”

And right there is the nub of it, one nub of it anyway: the “efforts to identify the Times’ sources.” Because in this case, the sources were precisely governmental—the FBI, for example, in its attempt to intimidate Wen Ho Lee. The rest of the piece, with a few unconvincing afterthoughts about what the paper might have done differently, is self-serving and even overtly deceptive. “The Times stories—echoed and often oversimplified by politicians and other news organizations—touched off a fierce public debate”; “Now the Times neither imagined the security breach nor initiated the prosecution of Wen Ho Lee”; “That concern had previously been reported in the Wall Street Journal, but without the details provided by the Times in a painstaking narrative”; “Nothing in this experience undermines our faith in any of our reporters, who remained persistent and fair-minded in their news-gathering in the face of some fierce attacks.”

And there it is again: Wen Ho Lee in jail, alone, shackled, without bail—and yet it is the Times that is subject to “accusations,” Times reporters who were subjected to those “fierce attacks.”

The editors did express a reservation about their “tone.” “In place of a tone of journalistic detachment,” they wrote, they had perhaps echoed the alarmism of their sources. Anyone who has read the Times in recent years—let alone been a subject of its pieces—knows that “a tone of journalistic detachment” in the paper is almost entirely a thing of the past. What is so remarkable, however, is not only how completely the Times identifies with the prosecution, but also how clearly the inversion of hunter and prey has taken hold. The injustice, the editors clearly feel, has been done not to Dr. Lee (although they say at one point that they may not have given him, imagine, “the full benefit of the doubt”) but to the reporters, and the editors, and the institution itself.

Two days later, the editorial section checked in, with “An Overview: The Wen Ho Lee Case.” Some of it, oddly enough, was another attack on Wen Ho Lee, whose activities it described as “suspicious and ultimately illegal,” “beyond reasonable dispute.” It described the director of the FBI, Louis Freeh, and Attorney General Janet Reno as being under “sharp attack.” The editorial was not free of self-justification; it was not open about its own contribution to the damage; it did seem concerned with “racial profiling”—a frequent preoccupation of the editorial page, in any case. The oddest sentences were these: “Moreover, transfer of technology to China and nuclear weapons security had been constant government concerns throughout this period. To withhold this information from readers is an unthinkable violation of the fundamental contract between a newspaper and its audience.” It had previously used a similar construction, for the prosecutors: “For the F.B.I. … not to react to Dr. Lee’s [conduct] would have been a dereliction of duty.” But the question was not whether the FBI should react (or not) but how, within our system, legally, ethically, constitutionally, to do so. And no one was asking the Times to “withhold information” about “government concerns,” least of all regarding alleged “transfer of technology to China” or “nuclear weapons security.” If the Times were asked to do anything in this matter, it might be to refrain from passing on, and repeating, and scolding, and generally presenting as “investigative reporting” what were in fact malign and exceedingly improper allegations, by “anonymous sources” with prosecutorial agendas, against virtually defenseless individuals.

There was—perhaps this goes without saying—no apology whatever to Wen Ho Lee. “The unthinkable violation of the fundamental contract between a newspaper and its audience” did not, obviously, extend to him. Lelyveld, too, had referred to a Corrections policy “to make our contract with readers more enforceable.” What “contract”? To rectify malignant misspelling of names? This concern, too, was not with facts, or substance, or subject, but to sustain, without earning or reciprocating, the trust of “readers.” The basis of “trust” was evidently quite tenuous. What had increased, perhaps in its stead, was this sense of being misunderstood, unfairly maligned, along with those other victims: FBI agents, informers, and all manner of prosecutors. No sympathy, no apology, certainly, for the man whom many, including in the end the judge, considered a victim—not least a victim of the Times.

That Times editors are by no means incapable of apology became clear on September 28, 2000, the same day as the editorial Overview. On that day, Bill Keller, the managing editor of the Times, posted a “Memorandum to the Staff,” which he sent as well to “media critics,” and which he said all staff members were “free to share outside the paper.”

It was an apology, and it was abject. “When we published our appraisal of our Wen Ho Lee coverage,” it said, “we anticipated that some people would misread it, and we figured that misreading was beyond our control. But one misreading is so agonizing to me that it requires a follow-up.”

“Through most of its many drafts,” Keller continued, the message had contained the words “of us” in a place where any reader of ordinary intelligence and understanding, one would have thought, would have known what was meant, since the words “to us” appear later in the same sentence. “Somewhere in the multiple scrubbings of this document,” however,

the words “of us” got lost. And that has led some people on the staff to a notion that never occurred to me—that the note meant to single out Steve Engelberg, who managed this coverage so masterfully, as the scapegoat for the shortcomings we acknowledged.

My reaction the first time I heard this theory was to laugh it off as preposterous. Joe and I tried to make clear in meetings with staff … that the paragraph referred to ourselves. … In the very specific sense that we laid our hands on these articles, and we overlooked some opportunities in our own direction of the coverage. We went to some lengths to assure that no one would take our message as a repudiation of our reporters, but I'm heartsick to discover that we failed to make the same clear point about one of the finest editors I know. Let the record show that we stand behind Steve and the other editors who played roles in developing this coverage. Coverage, as the message to readers said, of which we remain proud.

Bureaucracy at its purest. Reporters, editors, “masterfully directed” coverage, at worst some “opportunities” “overlooked.” The buck stops nowhere. “We remain proud” of the coverage in question, only “agonized” and “heartsick” at having been understood to fail to exonerate a member of this staff. The only man characterized as “the scapegoat” in the whole matter is—this is hardly worth remarking—one of the directors of the coverage, some might say the hounding, of Wen Ho Lee.

Something is obviously wrong here. Howell Raines, the editor of the editorial page (and the writer of the Overview) was, like Joe Lelyveld, a distinguished reporter. Editing and reporting are, of course, by no means the same. But one difficulty, perhaps with Keller as well, is that in an editing hierarchy, unqualified loyalty to staff, along with many other manifestations of the wish to be liked, can become a failing—intellectual, professional, moral. It may be that the editors’ wish for popularity with the staff has caused the perceptible and perhaps irreversible decline in the paper. There is, I think, something more profoundly wrong—not just the contrast between its utter solidarity, its self-regard, its sense of victimization and tender sympathy with its own, and its unconsciousness of its own weight as an institution, in the stories it claims to cover. Something else, perhaps more important, two developments actually—the emergence of the print reporter as celebrity and the proliferation of the anonymous source. There is an indication of where this has led us even in the Times editors’ own listing, among the “enormous obstacles” its reporters faced, of “government efforts to identify the Times’ sources.” The “sources” in question were, of course, precisely governmental. The Times should never have relied upon them, not just because they were, as they turned out to be, false, but because they were prosecutorial-—and they were turning the Times into their instrument.

In an earlier day, the Times would have had a safeguard against its own misreporting, including its “accounting” and its Overview of its coverage of the case of Wen Ho Lee. The paper used to publish in its pages long, unedited transcripts of important documents. The transcript of the FBI’s interrogation of Dr. Lee—on March 7, 1999, the day after the first of the Times articles appeared—exists. It runs to thirty-seven pages. Three agents have summoned Dr. Lee to their offices in “a cleared building facility.” They have refused him not only the presence of anybody known to him but permission to have lunch. They keep talking ominously of a “package” they have, and telephone calls they have been making about it to Washington. The contents of the package includes yesterday’s New York Times. They allude to it more than fifty times:

“You read that and it’s on the next page as well, Wen Ho. And let me call Washington real quick while you read that.”

“The important part is that, uh, basically that is indicating that there is a person at the laboratory that’s committed espionage and that points to you.”

“You, you read it. It’s not good, Wen Ho.”

“You know, this is, this is a big problem, but uh-mm, I think you need to read this article. Take a couple of minutes and, and read this article because there’s some things that have been raised by Washington that we’ve got to get resolved.”

And they resume:

“It might not even be a classified issue. … but Washington right now is under the impression that you’re a spy. And this newspaper article is, is doing everything except for coming out with your name … everything points to you. People in the community and people at the laboratory tomorrow are going to know. That this article is referring to you. …”

The agents tell him he is going to be fired (he is fired two days later), that his wages will be garnished, that he will lose his retirement, his clearance, his chance for other employment, his friends, his freedom. The only thing they mention more frequently than the article in the Times is his polygraph, and every mention of it is something they know to be false: that he “failed” it. They tell him this lie more than thirty times. Sometimes they mention it in conjunction with the Times article:

“You know, Wen Ho, this, it’s bad. I mean look at this newspaper article! I mean, ‘China Stole Secrets for Bombs.’ It all but says your name in here. The polygraph reports all say you’re failing … Pretty soon you’re going to have reporters knocking on your door.”

Then they get to the Rosenbergs:

“The Rosenbergs are the only people that never cooperated with the federal government in an espionage case. You know what happened to them? They electrocuted them, Wen Ho.”

“You know Aldrich Ames? He’s going to rot in jail! … He’s going to spend his dying days in jail.”

“Okay? Do you want to go down in history? Whether you’re professing your innocence like the Rosenbergs to the day they take you to the electric chair…”

Dr. Lee pleads with them, several times, not to interrupt him when he is trying to answer a question: “You want me, you want to listen two minutes from my explanation?” Not a chance:

“No, you stop a minute, Wen Ho. … Compared to what’s going to happen to you with this newspaper article…”

“The Rosenbergs are dead.”

“This is what’s going to do you more damage than anything. … Do you think the press prints everything that’s true? Do you think that everything that’s in this article is true? … The press doesn’t care.”

Now, it may be that the editors of the Times do not find this newsworthy, or that they believe their readers would have no interest in the fact that the FBI conducts its interrogations in this way. The Times might also, fairly, claim that it has no responsibility for the uses to which its front-page articles may be put, by the FBI or any other agency of government. Except for this. In both the editorial Overview and the “Note from the Editors,” as in Mr. Stewart’s op-ed piece, the Times’ sympathies are clearly with the forces of prosecution and the FBI. “Dr. Lee had already taken a lie detector test,” the editors write, for example, in their assessment, and “F.B.I. investigators believed that it showed deception when he was asked whether he had leaked secrets.”

In the days when the Times still published transcripts, the reader could have judged for himself. Nothing could be clearer than that the FBI investigators believed nothing of the kind. As they knew, Dr. Lee had, on the contrary, passed his polygraph—which is why, in his interrogation, they try so obsessively to convince him that he failed it. Even the editorial Overview, shorter and perhaps for that reason less misleading, shows where the Times’ sense of who is victimized resides. After two paragraphs of describing various activities of Dr. Lee’s as “improper and illegal,” “beyond reasonable dispute,” it describes, of all people, Louis Freeh, the director of the FBI (and Janet Reno, the attorney general) as being “under sharp attack.” Freeh was FBI director when agents of the Bureau, illegally detaining Monica Lewinsky, were conducting “investigations” of the same sort for the Office of the Independent Counsel. Freeh was also advocating, not just in government but directly to the press, more Special Prosecutors for more matters of all kinds.

But enough. The Times feels a responsibility to correct misimpressions it may have generated in readers—how names are spelled, what middle initials are, who is standing miscaptioned on which side of a photograph, which butterfly is which—is satisfied, in an important way, in its corrections. For the rest, it has looked at its coverage and found it good. The underlying fact, however, is this: For years readers have looked in the Times for what was once its unsurpassed strength: the uninflected coverage of the news. You can look and look, now, and you will not find it there. Some politically correct series and group therapy reflections on race relations perhaps. These appear harmless. They may even win prizes. Fifteen reporters working for one year might, perhaps, have been more usefully employed on some genuine issue of fact. More egregious, however, and in some ways more malign, was an article that appeared, on November 5, 2000, in the Sunday Times Magazine.

The piece was a cover story about Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Everyone makes mistakes. This piece, blandly certain of its intelligence, actually consisted of them. Everything was wrong. At the most trivial level, the piece said Moynihan had held no hearings about President Clinton’s health plan and no meetings with him to discuss welfare. (In fact, the senator had held twenty-nine such hearings in committee and many such discussions with the President.) At the level of theory, it misapprehended the history, content, purpose, and fate of Moynihan’s proposal for a guaranteed annual income. It would require a book to set right what was wrong in the piece—and in fact, such a book existed, at least about the guaranteed annual income. But what was, in a way, most remarkable about what the New York Times has become appeared, once again, in the way it treated its own coverage.

The Sunday Magazine’s editors limited themselves to a little self- congratulatory note. The article, they reported, had “prompted a storm of protest.” “But many said that we got it right, and that our writer said what had long seemed to be unspeakable.” (”Unspeakable” may not be what they mean. Perhaps it was a paraphrase.) They published just one letter, which praised the piece as “incisive.”

The Corrections column, however, when it came, was a gem. “An article in the Times Magazine last Sunday about the legacy of Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan,” it began, “misidentified a former senator who was an expert on military affairs. He was Richard Russell, not Russell Long.”

The “article also,” the correction went on, had “referred imprecisely” (a fine way to put it) to the senator’s committee hearings on President Clinton’s health care. (Not a word about welfare.) But the Corrections column saved for last what the Times evidently regarded as most important. “The article also overstated [another fine word] Senator Moynihan’s English leanings while he attended the London School of Economics. Bowler, yes. Umbrella, yes. Monocle, no.”

No “malignant” misspellings here. But nothing a reader can trust any longer, either. Certainly no reliable, uninflected coverage of anything, least of all the news. The enterprise, whatever else it is, has almost ceased altogether to be a newspaper. It is still a habit. People glance at it and, on Sundays, complain about its weight. For news they must look elsewhere. What can have happened here?

“The turning point at the paper,” I once wrote, in a piece of fiction, “was the introduction of the byline.” I still believe that to be true. I simply had no idea how radical the consequences of that turning point were going to be. Until the early seventies, it was a mark of professionalism in reporters for newspapers, wire services, newsmagazines, to have their pieces speak, as it were, for themselves, with all the credibility and authority of the publication in which they anonymously appeared. Reviews, essays, regular columns were of course signed. They were expressions of opinion, as distinct from reporting, and readers had to know and evaluate whose opinion it was. But when a reader said of a piece of information, “The Times says,” or “The Wall Street Journal says,” he was relying on the credibility of the institution. With occasional exceptions— correspondents, syndicated columnists, or sportswriters whose names were household words, or in attributing a scoop of extraordinary historical importance—the reporter’s byline would have seemed intrusive and unprofessional.

In television reporting, of course, every element of the situation was different. It would be absurd to say “CBS (or ABC, NBC, or even CNN) says” or even “I saw it on” one network or another. It had to be Walter Cronkite, later Dan Rather, Diane Sawyer, Tom Brokaw, Peter Jennings—not just because no television network or station had the authority of any favorite and trusted publication, but because seeing and hearing the person who conveyed the news (impossible, obviously, with the printed byline) was precisely the basis, for television viewers, of trust.

Once television reporters became celebrities, it was perhaps inevitable that print reporters would want at least their names known; and there were, especially at first, stories one did well to read on the basis of a trusted byline. There still existed what Mary McCarthy, in another context, called “the last of the tall timber.” But the tall timber in journalism is largely gone—replaced, as in many fields, by the phenomenon of celebrity. And gradually, in print journalism, the celebrity of the reporter began to overtake and then to undermine the reliability of pieces. Readers still say, “The Times says,” or “I read it in the Post” (so far as I can tell, except in the special case of gossip columns, readers hardly ever mention, or even notice, bylines), but trust in even once favorite newspapers has almost vanished. One is left with this oddly convoluted paradox: As survey after survey confirms, people generally despise journalists; yet they cite, as a source of information, newspapers. And though they have come, with good reason, to distrust newspapers as a whole, they still tend to believe each individual story as they read it. We all do. Though I may know a piece to be downright false, internally contradictory, in some profound and obvious way corrupted, I still, for a moment anyway, believe it. Believe the most obviously manufactured quotes, the slant, the spin, the prose, the argument with no capacity even to frame an issue and no underlying sense of what follows from what.

At the same time, a development in criticism, perhaps especially movie criticism, affected print journalism of every kind. It used to be that the celebrities featured on billboards and foremost in public consciousness were the movie stars themselves. For a while, it became auteurs, directors. Then, bizarrely but for a period of many years, it became critics, who starred in the discussion of movies. That period seems, fortunately, to have passed. But somehow, the journalist’s byline, influenced perhaps by the critic’s, began to bring with it a blurring of genres: reporting, essay, memoir, personal statement, anecdote, judgmental or critical review. Most of all, critical review—which is why government officials and citizens alike treat reporters in the same way artists regard most critics—with mixed fear and dismay. It is also why the subjects of news stories read each “news” piece as if it were a review on opening night.

There is no longer even a vestige or pretense, on the part of the print journalist, of any professional commitment to uninflected coverage of the news. The ambition is rather, under their bylines, to express themselves, their writing styles. Days pass without a single piece of what used to be called “hard news.” The celebrityhood, or even the aspiration to celebrity, of print reporters, not just in print but also on talk shows, has been perhaps the single most damaging development in the history of print journalism.

The second, less obvious, cause of decline in the very notion of reliable information was the proliferation of the “anonymous source”—especially as embodied, or rather disembodied, in Deep Throat. Many people have speculated about the “identity” of this phantom. Others have shown, more or less conclusively, that at least as described in All the President’s Men, by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, he did not, in fact could not, exist. Initially introduced as a narrative device, to hold together book and movie, this improbable creature was obviously both a composite, which Woodward, the only one who claims to have known and have consulted him, denies, and an utter fiction, which is denied by both Woodward and Bernstein—the better writer, who had, from the start, a “friend,” whose information in almost every significant respect coincides with, and even predates, Deep Throat’s. But the influence of this combination, the celebrity reporter and the chimera to whom the reporter alone has access, has been incalculable.

The implausibility of the saga of Deep Throat has been frequently pointed out. Virtually every element of the story—the all-night séances in garages; the signals conveyed by moved flowerpots on windowsills and drawings of clocks in newspapers; the notes left by prearrangement on ledges and pipes in those garages; the unidiomatic and essentially uninformative speech—has been demolished. Apart from its inherent impractibilities, for a man requiring secrecy and fearing for his life and the reporter’s, the strategy seems less like tradecraft than a series of attention- getting mechanisms. This is by no means to deny that Woodward and Bernstein had “sources,” some but far from all of whom preferred to remain anonymous. From the evidence in the book they include at least Fred Buzhardt, Hugh Sloan, John Sears, Mark Felt and other FBI agents, Leonard Garment, and, perhaps above all, the ubiquitous and not infrequently treacherous Alexander Haig. None of these qualify as Deep Throat, nor does anyone, as depicted in the movie or book. Woodward’s new rationale is this: the secret of the phantom’s name must be kept until the phantom himself reveals it—or else dies. Woodward is prepared, however, to disqualify candidates whom others—most recently Leonard Garment, in an entire book devoted to such speculation—may suggest, by telling, instance by instance, who Deep Throat is not. A long list, obviously, which embraces everyone.