#REVOLUTION

Text

#shiadanni#state champs#bored girl#woman beauty#revolution#breathless#delacour20#short skirt#feeling cute

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A.2.16 Does anarchism require “perfect” people to work?

No. Anarchy is not a utopia, a “perfect” society. It will be a human society, with all the problems, hopes, and fears associated with human beings. Anarchists do not think that human beings need to be “perfect” for anarchy to work. They only need to be free. Thus Christie and Meltzer:

”[A] common fallacy [is] that revolutionary socialism [i.e. anarchism] is an ‘idealisation’ of the workers and [so] the mere recital of their present faults is a refutation of the class struggle … it seems morally unreasonable that a free society … could exist without moral or ethical perfection. But so far as the overthrow of [existing] society is concerned, we may ignore the fact of people’s shortcomings and prejudices, so long as they do not become institutionalised. One may view without concern the fact … that the workers might achieve control of their places of work long before they had acquired the social graces of the ‘intellectual’ or shed all the prejudices of the present society from family discipline to xenophobia. What does it matter, so long as they can run industry without masters? Prejudices wither in freedom and only flourish while the social climate is favourable to them … What we say is … that once life can continue without imposed authority from above, and imposed authority cannot survive the withdrawal of labour from its service, the prejudices of authoritarianism will disappear. There is no cure for them other than the free process of education.” [The Floodgates of Anarchy, pp. 36–7]

Obviously, though, we think that a free society will produce people who are more in tune with both their own and others individuality and needs, thus reducing individual conflict. Remaining disputes would be solved by reasonable methods, for example, the use of juries, mutual third parties, or community and workplace assemblies (see section I.5.8 for a discussion of how could be done for anti-social activities as well as disputes).

Like the “anarchism-is-against-human-nature” argument (see section A.2.15), opponents of anarchism usually assume “perfect” people — people who are not corrupted by power when placed in positions of authority, people who are strangely unaffected by the distorting effects of hierarchy, privilege, and so forth. However, anarchists make no such claims about human perfection. We simply recognise that vesting power in the hands of one person or an elite is never a good idea, as people are not perfect.

It should be noted that the idea that anarchism requires a “new” (perfect) man or woman is often raised by the opponents of anarchism to discredit it (and, usually, to justify the retention of hierarchical authority, particularly capitalist relations of production). After all, people are not perfect and are unlikely ever to be. As such, they pounce on every example of a government falling and the resulting chaos to dismiss anarchism as unrealistic. The media loves to proclaim a country to be falling into “anarchy” whenever there is a disruption in “law and order” and looting takes place.

Anarchists are not impressed by this argument. A moment’s reflection shows why, for the detractors make the basic mistake of assuming an anarchist society without anarchists! (A variation of such claims is raised by the right-wing “anarcho”-capitalists to discredit real anarchism. However, their “objection” discredits their own claim to be anarchists for they implicitly assume an anarchist society without anarchists!). Needless to say, an “anarchy” made up of people who still saw the need for authority, property and statism would soon become authoritarian (i.e. non-anarchist) again. This is because even if the government disappeared tomorrow, the same system would soon grow up again, because “the strength of the government rests not with itself, but with the people. A great tyrant may be a fool, and not a superman. His strength lies not in himself, but in the superstition of the people who think that it is right to obey him. So long as that superstition exists it is useless for some liberator to cut off the head of tyranny; the people will create another, for they have grown accustomed to rely on something outside themselves.” [George Barrett, Objections to Anarchism, p. 355]

Hence Alexander Berkman:

“Our social institutions are founded on certain ideas; as long as the latter are generally believed, the institutions built on them are safe. Government remains strong because people think political authority and legal compulsion necessary. Capitalism will continue as long as such an economic system is considered adequate and just. The weakening of the ideas which support the evil and oppressive present day conditions means the ultimate breakdown of government and capitalism.” [What is Anarchism?, p. xii]

In other words, anarchy needs anarchists in order to be created and survive. But these anarchists need not be perfect, just people who have freed themselves, by their own efforts, of the superstition that command-and-obedience relations and capitalist property rights are necessary. The implicit assumption in the idea that anarchy needs “perfect” people is that freedom will be given, not taken; hence the obvious conclusion follows that an anarchy requiring “perfect” people will fail. But this argument ignores the need for self-activity and self-liberation in order to create a free society. For anarchists, “history is nothing but a struggle between the rulers and the ruled, the oppressors and the oppressed.” [Peter Kropotkin, Act for Yourselves, p. 85] Ideas change through struggle and, consequently, in the struggle against oppression and exploitation, we not only change the world, we change ourselves at the same time. So it is the struggle for freedom which creates people capable of taking the responsibility for their own lives, communities and planet. People capable of living as equals in a free society, so making anarchy possible.

As such, the chaos which often results when a government disappears is not anarchy nor, in fact, a case against anarchism. It simple means that the necessary preconditions for creating an anarchist society do not exist. Anarchy would be the product of collective struggle at the heart of society, not the product of external shocks. Nor, we should note, do anarchists think that such a society will appear “overnight.” Rather, we see the creation of an anarchist system as a process, not an event. The ins-and-outs of how it would function will evolve over time in the light of experience and objective circumstances, not appear in a perfect form immediately (see section H.2.5 for a discussion of Marxist claims otherwise).

Therefore, anarchists do not conclude that “perfect” people are necessary anarchism to work because the anarchist is “no liberator with a divine mission to free humanity, but he is a part of that humanity struggling onwards towards liberty.” As such, ”[i]f, then, by some external means an Anarchist Revolution could be, so to speak, supplied ready-made and thrust upon the people, it is true that they would reject it and rebuild the old society. If, on the other hand, the people develop their ideas of freedom, and they themselves get rid of the last stronghold of tyranny — the government — then indeed the revolution will be permanently accomplished.” [George Barrett, Op. Cit., p. 355]

This is not to suggest that an anarchist society must wait until everyone is an anarchist. Far from it. It is highly unlikely, for example, that the rich and powerful will suddenly see the errors of their ways and voluntarily renounce their privileges. Faced with a large and growing anarchist movement, the ruling elite has always used repression to defend its position in society. The use of fascism in Spain (see section A.5.6) and Italy (see section A.5.5) show the depths the capitalist class can sink to. Anarchism will be created in the face of opposition by the ruling minorities and, consequently, will need to defend itself against attempts to recreate authority (see section H.2.1 for a refutation of Marxist claims anarchists reject the need to defend an anarchist society against counter-revolution).

Instead anarchists argue that we should focus our activity on convincing those subject to oppression and exploitation that they have the power to resist both and, ultimately, can end both by destroying the social institutions that cause them. As Malatesta argued, “we need the support of the masses to build a force of sufficient strength to achieve our specific task of radical change in the social organism by the direct action of the masses, we must get closer to them, accept them as they are, and from within their ranks seek to ‘push’ them forward as much as possible.” [Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, pp. 155–6] This would create the conditions that make possible a rapid evolution towards anarchism as what was initially accepted by a minority “but increasingly finding popular expression, will make its way among the mass of the people” and “the minority will become the People, the great mass, and that mass rising up against property and the State, will march forward towards anarchist communism.” [Kropotkin, Words of a Rebel, p. 75] Hence the importance anarchists attach to spreading our ideas and arguing the case for anarchism. This creates conscious anarchists from those questioning the injustices of capitalism and the state.

This process is helped by the nature of hierarchical society and the resistance it naturally developed in those subject to it. Anarchist ideas develop spontaneously through struggle. As we discuss in section I.2.3, anarchistic organisations are often created as part of the resistance against oppression and exploitation which marks every hierarchical system and can., potentially, be the framework of a few society. As such, the creation of libertarian institutions is, therefore, always a possibility in any situation. A peoples’ experiences may push them towards anarchist conclusions, namely the awareness that the state exists to protect the wealthy and powerful few and to disempower the many. That while it is needed to maintain class and hierarchical society, it is not needed to organise society nor can it do so in a just and fair way for all. This is possible. However, without a conscious anarchist presence any libertarian tendencies are likely to be used, abused and finally destroyed by parties or religious groups seeking political power over the masses (the Russian Revolution is the most famous example of this process). It is for that reason anarchists organise to influence the struggle and spread our ideas (see section J.3 for details). For it is the case that only when anarchist ideas “acquire a predominating influence” and are “accepted by a sufficiently large section of the population” will we “have achieved anarchy, or taken a step towards anarchy.” For anarchy “cannot be imposed against the wishes of the people.” [Malatesta, Op. Cit., p. 159 and p. 163]

So, to conclude, the creation of an anarchist society is not dependent on people being perfect but it is dependent on a large majority being anarchists and wanting to reorganise society in a libertarian manner. This will not eliminate conflict between individuals nor create a fully formed anarchist humanity overnight but it will lay the ground for the gradual elimination of whatever prejudices and anti-social behaviour that remain after the struggle to change society has revolutionised those doing it.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#anarchocommunist#communism#anarchism#revolution#antifascism#anarchist#socialism#anarchocommunism#anarchy#antifa#communist#antifascist#socialist

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

"The idea of reforming Omelas is a pleasant idea, to be sure, but it is one that Le Guin herself specifically tells us is not an option. No reform of Omelas is possible — at least, not without destroying Omelas itself:

If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms.

'Those are the terms', indeed. Le Guin’s original story is careful to cast the underlying evil of Omelas as un-addressable — not, as some have suggested, to 'cheat' or create a false dilemma, but as an intentionally insurmountable challenge to the reader. The premise of Omelas feels unfair because it is meant to be unfair. Instead of racing to find a clever solution ('Free the child! Replace it with a robot! Have everyone suffer a little bit instead of one person all at once!'), the reader is forced to consider how they might cope with moral injustice that is so foundational to their very way of life that it cannot be undone. Confronted with the choice to give up your entire way of life or allow someone else to suffer, what do you do? Do you stay and enjoy the fruits of their pain? Or do you reject this devil’s compromise at your own expense, even knowing that it may not even help? And through implication, we are then forced to consider whether we are — at this very moment! — already in exactly this situation. At what cost does our happiness come? And, even more significantly, at whose expense? And what, in fact, can be done? Can anything?

This is the essential and agonizing question that Le Guin poses, and we avoid it at our peril. It’s easy, but thoroughly besides the point, to say — as the narrator of 'The Ones Who Don’t Walk Away' does — that you would simply keep the nice things about Omelas, and work to address the bad. You might as well say that you would solve the trolley problem by putting rockets on the trolley and having it jump over the people tied to the tracks. Le Guin’s challenge is one that can only be resolved by introspection, because the challenge is one levied against the discomforting awareness of our own complicity; to 'reject the premise' is to reject this (all too real) discomfort in favor of empty wish fulfillment. A happy fairytale about the nobility of our imagined efforts against a hypothetical evil profits no one but ourselves (and I would argue that in the long run it robs us as well).

But in addition to being morally evasive, treating Omelas as a puzzle to be solved (or as a piece of straightforward didactic moralism) also flattens the depth of the original story. We are not really meant to understand Le Guin’s 'walking away' as a literal abandonment of a problem, nor as a self-satisfied 'Sounds bad, but I’m outta here', the way Vivier’s response piece or others of its ilk do; rather, it is framed as a rejection of complacency. This is why those who leave are shown not as triumphant heroes, but as harried and desperate fools; hopeless, troubled souls setting forth on a journey that may well be doomed from the start — because isn’t that the fate of most people who set out to fight the injustices they see, and that they cannot help but see once they have been made aware of it? The story is a metaphor, not a math problem, and 'walking away' might just as easily encompass any form of sincere and fully committed struggle against injustice: a lonely, often thankless journey, yet one which is no less essential for its difficulty."

- Kurt Schiller, from "Omelas, Je T'aime." Blood Knife, 8 July 2022.

#kurt schiller#ursula k. le guin#quote#quotations#the ones who walk away from omelas#trolley problem#activism#introspection#discomfort#reform#revolution#suffering#ethics#morality

10K notes

·

View notes

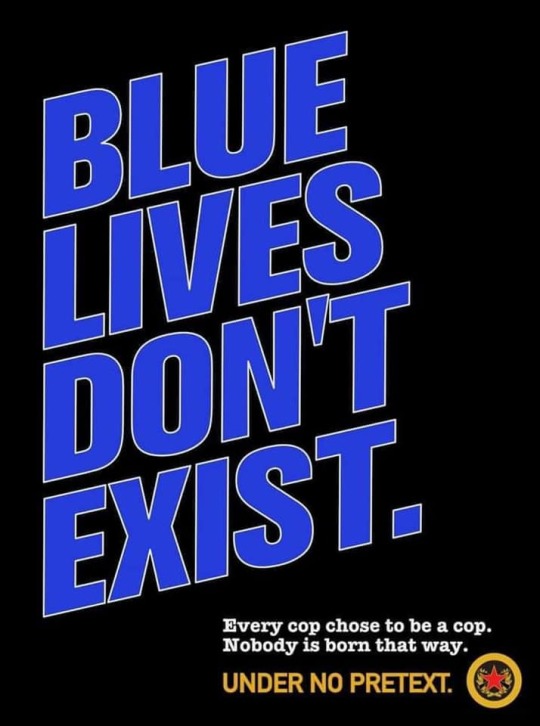

Photo

#anarchism#anarchist#acab#antifascism#anarchocommunism#anarcho#anarchopunk#communism#revolution#antifascist#antifa#communist#anarchocommunist

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

The ice maker makes revolution

#funny#ice wizard#silly#cgi animation#ice maker#lilicewizard#war#revolution#cute#bandana#dreams ps4#fire

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

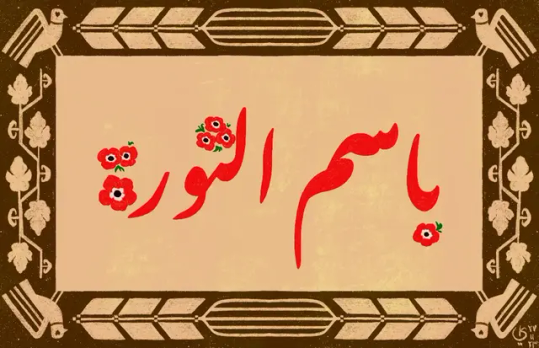

'In the name of revolution'

During the 2nd Intifada it was a popular slogan, that women embroidered on their dresses 🫒✌🏽

#the border features tatreez#traditional art#art#digital art#artists on tumblr#palestine#nature#bird#dove#revolution#flower#poppy

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bunker Buster

#billionaires#elon musk#jeff bezos#revolution#anarchism#capitalism#socialism#apocalypse#political cartoon

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

March 8th: International Women's Day

The Palestinian woman: the guardian of the dream and the shield of the revolution

(Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, 2024)

#pflp#popular front for the liberation of palestine#march 8th#international working women's day#international women's day#free palestine#palestine#feminism#women#guerrilla#communism#revolution#poster#propaganda#posters#2024

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zack de la Rocha of Rage Against the Machine, 1997 [x]

#Rage Against the Machine#Zack de la Rocha#ratm#ZDLR#anti capitalism#capitalism#anti establishment#authoritarian#anti authoritarian#anarchy#anarchism#socialism#revolution#oppression#politics#class struggle#class war#class warfare#rebel#rebellion#protest#1990s#90s#1997#my gifs

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

On May Day 2017, anarchists participated in lively demonstrations all around the United States, from the heartland to the coasts. In the Northwest, Seattle witnessed a successful block party at the site of a juvenile corrections center, while in Olympia anarchists barricaded train tracks to oppose fracking and clashed with police. Support arrestees here. Yet Portland, Oregon may take the cake for the most creative and combative May Day. Demonstrators not only defended themselves from unprovoked attacks from police who declared the march a riot—they also introduced exciting new innovations into the aesthetic of the black bloc street presence. Here, comrades from Portland explain their goals with the giant spiders they created for May Day, and offer a helpful guide for those who wish to make spiders of their own.

In an effort to bridge the gap between art and activism, giant spiders were assembled off-site and pushed up the street to the demonstration, stocked with water bottles, snacks, earplugs, and other party favors. The idea was to narrow the divide between “us” and “them” that often exists at demonstrations, and it was a complete success. We performed community outreach, engaged in cultural development, boosted morale, provided crucial supplies, and created an amazing photo opportunity in the process.

The concept is multi-dimensional: it works on many different levels. The idea began from frustrations around attendance at local demonstrations. In Portland, where the majority of citizens seem to be white, middle-class, and apolitical on account of these privileges, they don’t show up unless a demonstration concerns their interests specifically. However, Portlanders are fascinated by their own love of art and “wacky” stuff as well as the commodification of protest as “funtertainment.” We decided to embrace this love of the “weird” to test whether a hyper-localized approach to engaging people could succeed.

Our tactical art enabled us to fill a supporting role for other participants in the march, helping challenge narratives that the black bloc is an “othered” or “othering” tactic. Whether this separation is intentional or not, the fact remains that the general public is often hesitant to engage with us. Bearing that in mind—as well the tendency of the Portland Police Department to brutally shut down demonstrations—we stocked our Spiders with fliers, water, LAW (liquid, antacid, water, the eyewash with which street medics treat pepper spray), ear plugs, and snacks. We also included a few other party favors, because anarchy needs revelry!

We intentionally engaged with the folks around us. A lot of people walked up to ask what the spiders meant! It was inspiring to see so much dialogue between folks in everyday garb and folks in black bloc. We explained the ideas behind our actions as anarchists and the creations themselves: the three spiders representing Mutual Aid, Solidarity, and Direct Action.

A word about symbolism. The idea of using the spider as an icon of resistance is that spiders are always there watching, waiting, and keeping the environment free of pesky insects and other parasites that consume resources without supporting their fellow beings. While we may look scary, we’re here with you and for you. We are the spiders, and the insects are the societal ills that we fight against.

The symbolism of the black widow spider is rich with history that guides our work. We want to contribute to that rich history, adding our own interpretations. Mutual Aid, Solidarity, Direct Action are our black widow’s cruses. (Crux? Curse? Cures?)

In regards to developing our own culture, there are many barriers we face in this process. State repression is the biggest threat, of course. The specter of state repression can complicate organizing, planning, and building trust in our communities. Portland has a history of repression and slander, ruining the lives of activists and anarchists; these horror stories reverberate throughout the underground. We can’t allow ourselves to be publicly disparaged and forced into hiding by our adversaries and their culture war, so we create as a political act. Creating is intuitively human: we plan, we build, we think, we conspire, we imagine. It is also an activity in which everyone can engage to some degree while building new skills. It enables us to get to know each other, build trust, and share time and company.

More globally, seizing the Spectacle is a step towards our goals, because it allows us to dictate our own narratives. With the development of Public Relations and Social Engineering, the visage of capitalism has come to define its delusional reality. To paraphrase Guy Debord, lived experiences are now taken in as a collection of representational images. We can tell our own stories and show the general public what these three principles mean in action. We can create our own mythos, speaking out on our own terms, in our own language, with our own symbols. The state and media dictate too much of what we’re allowed to say and how it’s spun—it’s time to spin our own webs to connect and fortify our relationships.

We are building the bridges we need to move forward. The existing connections between art, activism, and anarchism are fiery and well-storied. The new wave of repression under Trump’s regime is still building steam, but it is already proving dangerous. We need to be more careful than ever. Art allows us to demonstrate and show our fangs, and we can use art to empower those around us.

#how-to#guides#and manuals#May Day#Portland#protest#reportback#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#mutual aid#grassroots#organization#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

FUCK!!!!!!!! FFFUUUCCCKKK!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! MIRACULOUS LADYBUG GOOD!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

#this scene made me cry#like actual tears#what the fuck miraculous ladybug what the FUCK#anyway aaaa PAINTING BE APON YEE#my art#miraculous ladybug spoilers#mlb spoilers#ml spoilers#miraculous ladybug season 5#revolution#ml revolution#mlb revolution#miraculous ladybug revolution#ml#mlb#miraculous#miraculous ladybug#adrien agreste#marinette dupain cheng#adrinette#kiss

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

If women all around the United States turned off their television sets for an extended period of time and purchased no products other than the very basic necessities to protest exploitation of women ... these actions would have significant political and economic consequences. Since women are not thoroughly organised and are daily manipulated by ruling male groups who profit from sexism and female consumerism, we have never exercised this power. Most women do not understand the forms of power they could exercise. They need political education for critical consciousness.

bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (2000), p.94

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

When will the revolution come?

I think it's here. A revolution isn't when everyone collectively wakes up one day and goes "time to destroy the government", a revolution is just a series of events grouped together that we will call a revolution later. They take time. French revolution? 10 years. American revolution? 7 years. We're already underway - maybe we have been since as early as the BLM protests in 2020. What we need to do now is just do our part and build momentum

#the global intifada#revolution#i think tiktoks flowerboyserge has made videos about this go check him out#palestine#sudan#congo#yemen#haiti#syria#hawaii#all the oppressed people of the world#freedom for all#socialism#mine

1K notes

·

View notes