#Revolution of 1830

Text

The Uses of History, 7 – From France 1812 to Russia, 1917, 4

The Uses of History, 7 – From France 1812 to Russia, 1917, 4

(Image credit: Web Gallery of Art)

Following the failure of the Decembrist Revolt in 1825 and the accession of Tsar Nicholas I, the vast Russian Empire was locked into extreme reactionarianism. The reformist elements were suppressed and no license was permitted in expressing contrary views to Divine Right for the Tsar under God’s anointing, aristocratic privilege as its corollary, as well as the…

View On WordPress

#July Monarchy#King Charles X#Louis-Philippe#Marmont#Revolution of 1830#Russian émigrés in France#Swiss Guard

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

charming & terrible, etc

#enjolras#les misérables#victor hugo#1830s#i read révolution tome 1 and through comparison of intense revolution twinks I was possessed to draw this until 2am like it's 2014

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Citizen Cooks in the Age of Napoleon

Excerpt about the role of cooks in France after the abolition of culinary guilds, and how they navigated a world which demanded for them to find new ways to stay relevant and prosperous. From Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France, 1650-1830 by Jennifer J. Davis:

French cooks sought new sites upon which to rebuild the authority of culinary labor. Throughout the early nineteenth century cooks increasingly adopted scientific terms to demonstrate their reliability and profound knowledge of the culinary arts. Such language communicated the author's education and distinction, just as an appeal to an elite patron had done in the 1660s and referral to a cook's professional expertise had done in the 1760s. The rhetoric and institutions of scientific knowledge also provided a means of distinguishing men's work from women's in the post-revolutionary era. During the early nineteenth century, cooks' claims to scientifically valuable savoir-faire rested on three crucial points of culinary innovation: food preservation, the improved production of bouillon, and gelatin extraction.

As these processes left the realm of traditional knowledge and became sites of scientific inquiry by tradespeople and amateurs alike, cooks sought to maintain authority in this arena by including scientific terms and theories in cookbooks, advertisements, and government petitions.

Two factors encouraged cooks' claims to scientific knowledge during this era. First, when Napoleon Bonaparte took the reins of government as first consul in 1799 and established himself as emperor in 1804, he raised medical doctors and academic scientists, Idéologues, to positions of political prominence. From these posts, the Idéologues subsidized experiments and inventions deemed useful to the nation and encouraged the popularization of science in the public sphere through state sponsorship of exhibitions and print forums. The Idéologues particularly supported research related to food preparation and preservation that might benefit France's armies and navies, with obvious benefits for professional cooks. Many cooks presented their particular techniques to the government during this time, seeking both financial recompense and public acclaim. Second, a voluntary association closely allied with the Idéologues' vision, the Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Society for the Encouragement of National Industry), provided a forum in which formally trained scientists, politicians, merchants, artisans, and curious educated men might unite to address questions that inhibited French science and industry.

Together, these men sought to develop a more coherent program for industrial advancement than any one group could achieve independently. The society explicitly sought to join scientific knowledge to artisanal practical expertise, recognizing that each group had strengths that would benefit industrial development. This association invested heavily in three diffuse projects that eventually infused the most basic culinary processes with scientific awareness: new methods of food preservation to benefit the nation's armies and navies, new methods of stock preparation to sustain the nation's poor, and new methods of extracting gelatin from bones to improve hospital and military diets at little added expense.

#Illustration from L'art du Cuisinier by Antoine Beauvilliers (1814)#Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France 1650-1830#Jennifer J. Davis#David#citizen cooks#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#napoleonic era#first french empire#french empire#19th century#french revolution#cooks#food#culinary history#france#1800s#history#french history#Antoine Beauvilliers#Beauvilliers#Society for the Encouragement of National Industry#Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

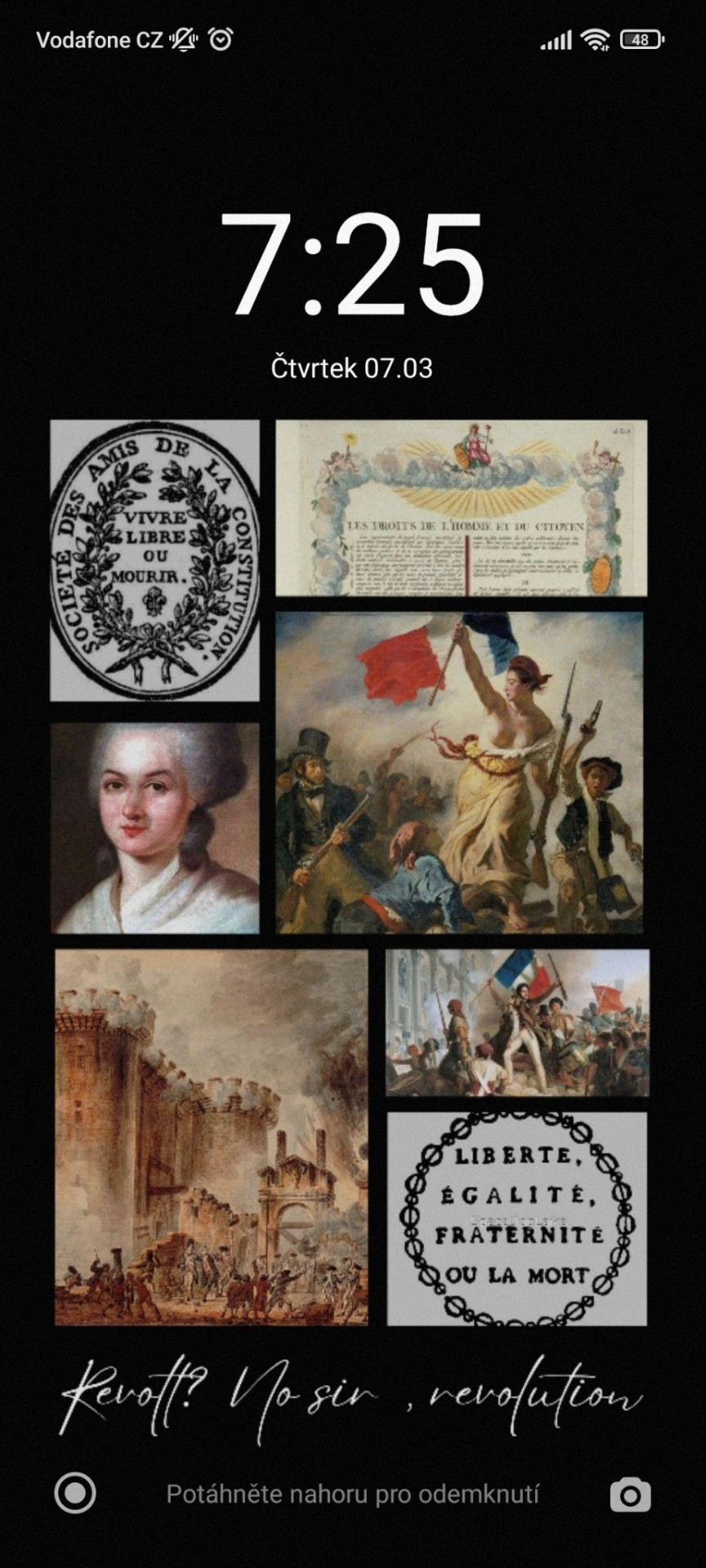

Okay I have a theory that lock screens and laptop stickers are the new true windows to the soul.

Feel free to reblog with your current lock screen and/or laptop stickers!

(doing this because I a) kind of want to flex b) am really curious to see others')

#tag game#reblog game#ask game#french revolution#classics#frev#daria#lockscreens#litearture#ao3#stickers#olympe de gouges#Athena#medusa#yes I know the painting is the 1830s revolution I just like how it looks okay#frev community#aesthetics#history

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

the history book on the shelf is always repeating itself or some shit because I'm listening to viva la vida by coldplay while reading two lovers being reunited again after death

#first art heist baby regulus and james#now aragorn and legolas#my heart is Aching#oh and the topic i have for tomorrow's history class is literally the revolution of 1830#which made me giggle#crys' middle earth stuff#aralas#jegulus

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barricade day 2023

the June rebellion of 1832

In honour of what we Les Misérables fans call “Barricade day” or June 5th, here is a run down of the 1832 June rebellion, it’s causes, consequences, why it happened at all, the aftermath and how it inspired Victor Hugo to write his perhaps most well known novel and famous 90s pop operatic musical.

Disclaimer here.

No formal tags, but, poking: @virgosjukebox, @enjolras-the-revolutionary, @honorhearted & @withinycu in case this interests them.

why did it happen?: June 5th, 1832. The June rebellion, in French: Insurrection républicaine à Paris en juin 1832. France is in in fighting yet again, the constitutional monarchy is replaced with the, to some autocratic president Casimir Pierre Périer, on 16 May 1832. 2 years prior the July revolution had occured, additionally such is the world and the 1830s the people of France are hungry, tired and are looking for a fight. The death of commander Lemarque as mentioned in the book and the musical only pushed the common people further. In short many factors led to the June rebellion. The primary factors however, were... political unrest, inability to feed the working classes and civil unrest as well as influx of new ideas following the exit of Napoleon.

Consequences: such as every failed uprising goes, the revolutionaries paid dearly for it severe trials followed the June rebellion many were put to death (hanged or shot), many of the leaders of the uprising were, like the American revolution college age school boys or simply angry common people. Famously the person who waved the symbolic red flag of revolt was a Parisian artist who was nearly put to death but escaped via trial.

In pop culture: I don’t need to say it but I am saying it anyway, many only know or care about the June Rebellion because of Hugo’s novel. Additionally, unlike the musical, the book, whilst possessing some hope paints a rather bleak picture of humanity and uprising. Even so, it’s political commentary (novel) holds up and I’ve attended many a political protest to see signs bearing the words, “do you hear the people sing?”

Further reading: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/June_Rebellion#:~:text=On%201%20June%201832%2C%20Jean,the%20July%20Revolution%20of%201830., https://historythings.com/victor-hugos-inspiration-les-miserables-june-rebellion-1832/, https://blogs.bu.edu/guidedhistory/moderneurope/revolutioninfrance/, https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-4438-4721-6, https://youtu.be/Ybi8wzgQBlg, and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LUyYLL1BfYc.

#barricade day#meerathehistorian#les mis letters#victor hugo#june rebellion#july revolution#history#historical references#1830s#19th Century#French Revolution#French History#revolution#european history#musicals#musical theatre#les mis#les miserables#les mis book#les mis musical#queue are made by history#long post#long post tw

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ideal Republic:

I don't know about you, but in France, there's increasingly justified complaints that the representative system is completely out of touch with its people. We need more democracy, better representation. A profound system change to address our problems.

I would like a Republic with a president refusing to live in the Presidential Palace but rather in his apartment like the majority of French people, as President Mujica did. He would be less disconnected from the reality of the people because he would live among the majority of them (similarly to how French revolutionaries worked at the Tuileries but didn't live there). The case of President Mujica should no longer be an exception but the rule.

The presidential palace should serve only as a workplace and to receive foreign dignitaries.

All government members, including deputies, should now live with a salary decrease similar to that of the majority of French people. We can't ask the people to make efforts if we don't practice them ourselves.

I would like a model based on the First Republic with a much more controlled executive, divided in the General Assembly as the Republicans proclaimed. I would like a new constitution as close as possible to that of 1793. Like the First Republic, I would like citizens who are not part of the government or the General Assembly to take the stand to voice their demands, difficulties, criticisms, absolutely everything.

Government members who are under investigation by justice should no longer receive any special treatment. We citizens don't benefit from it, so why should they?

After all, it is the government that should serve the people, not the other way around.

Referendums should be well conducted, well respected, ensuring that the fundamental rights acquired after many struggles remain respected as inviolable rights (abolition of the death penalty, right to abortion, marriage for all, etc.).

Social progress should continue even if it might displease some…

Only this Republic could be the one that meets our needs… But I don't think I'll see it one day… Anyway, I've always thought that the rights we've acquired have only come after years of struggle, that revolutions happen in different periods. The most recent example that comes to mind is the one where we almost had a revolution in May 1968. There will surely be another day, we will have a real program for the people again, then it will be fought and it will be a cycle… But every concession we wrestle is a victory, and that's not a reason to give up (for example: there were real social revolutions in 1792, in 1830, in 1848, and in 1870, for example, even if in the end there were always regressions or the fact that these revolutions were buried or failed, they managed to secure very significant concessions and always to rise again, without all these revolutionaries we might even have been at risk of losing all our rights, we wouldn't have had them at all).

#France#revolution#french revolution#the communards#1848#1830#Republic#Third Republic#Fifth Republic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cunk on Earth is really funny but unfortunately being a historian means that the inaccuracies prevent me from fully enjoying it

#using the liberty leading the people for the french revolution especially its one of my biggest pet peeves ITS ABOUT 1830#personal

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

La Marseillaise was created in 1792

Did Lafayette ever mention his opinion on it (even tho it only became the french national anthem in like, the late 1900's)?

Dear @msrandonstuff,

I have never seen any written record of La Fayette’s opinion concerning La Marseillaise but here a few thoughts that I would like to contribute.

La Marseillaise is a very patriotic song and La Fayette never ceased to be a very patriotic Frenchman. He may sometimes have disagreed with the political elite of France, but he never ceased to love the country itself. The song is not political and more an appeal to take up arms and defend France. La Fayette himself had several commands during the French Revolution and he wrote upon leaving France, that it was one of his deepest regrets that he could no longer defend is native home.

La Marseillaise was originally composed in 1792 during the French Revolution as the Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg. The Army of Rhine was under the command of Marshal Nicolas Luckner and Rouget de Lisle originally dedicated the song to the Marshal. La Fayette went along well with Luckner – to well perhaps, the two were individually accused of plotting together to overthrow the Revolution and to rescue the King. Luckner was later guillotined. It was also Luckner who replaced La Fayette after the latter fleet France and was imprisoned in Prussia.

Rouget de Lisle himself was an ardent Royalist, refused to take the Oath of Allegiance to the new constitution and was eventually imprisoned himself. He was in his political views not too far removed from La Fayette’s views although there were some notable differences.

The most compelling is probably the fact that Rouget de Lisle visited La Fayette for a short time while the latter was in exile in Utrecht near Vianen in the Netherlands. As interesting as this sounds, I have yet to puzzle out the finer details.

The song accompanied La Fayette all throughout his life. La Marseillaise is and was the official French anthem between 1795 and 1799 as well as shortly during 1830 and then again from 1870 onwards. During his American Tour in 1824/25 the Americans sang a song called Hail! Lafayette to the tune of La Marseillaise and in 1831, the French government under King Louis-Philippe tried to crush a worker’s revolt in Lyon. Martial law was declared, and La Marseillaise was banned. La Fayette opposed this line of action passionately and while the banning of one song was surely the least of La Fayette’s complaints, it was very well a part of the greater picture.

While there is no written account that I know of, I feel comfortable in saying that La Fayette in all likelihood liked La Marseillaise. I hope that helped and I hope you have/had a beautiful day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#louis philippe#la marseillaise#french history#french revolution#american history#nicolas luckner#claude joseph rouget de lisle#1792#1795#1799#1830#1831#1870#tour of 1824 1825

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Philippe I vs Charles X (It's King vs King.) During the July Revolution.

This is a revolution between Kings. First one is Louis Philippe I, and the Second one i is Charles X. The fight between the Kings of France.

#kingdom of france#July Revolution#July monarchy#Bourbon restoration#Charles X#Louis Philippe I#Revolutions of 1830#History#Historical#King#Kings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wowwwww, Vicky isn't even trying to hide that he's talking about 1848 by 4.1.2, huh?

#''4.1.1 mentioned 1830 and the July revolution by name''#''surely I have plausible deniability established''#I mean yeah but My Guy why don't you just mention Guizo by name next time#like CHRIST#shitposting through les mis#les mis#thicc bricc

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: I need to look up the historical fashion of the period so I can dress accordingly

*Starts to google favorite painting*

*remembers that favortie painting is literally always my desktop background*

Happy Barricade Day Y’all!

#barricade day#the one day a year I'm mildly marxist I guess#revolution#this is technically the july 1830 one

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, hypothetically, what would you all say if I were to say that I’m writing a story about the July Revolution of 1830 and the formation of Les Amis?

#yep mhm 100% hypothetically#les mis#les miserables#les misérables#les amis#les amis de l'abc#les mis fanfiction#les mis fan fiction#les mis fanfic#les mis fan fic#july revolution#july revolution of 1830#the july revolution of 1830

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The British were unable to resist this attack, and retreated into the College, where they considered themselves safe. Our army was there in an instant, and cannon were planted before the door, and after two or three discharges, a white flag appeared at a window when the British surrendered. ... The ground was frozen, and all the blood which was shed, remained on the surface, which added to the horror of this scene of carnage.

A former solider, remembering the American Revolution’s Battle of Princeton, in Maine’s Eastern Argus, October 14, 1831

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

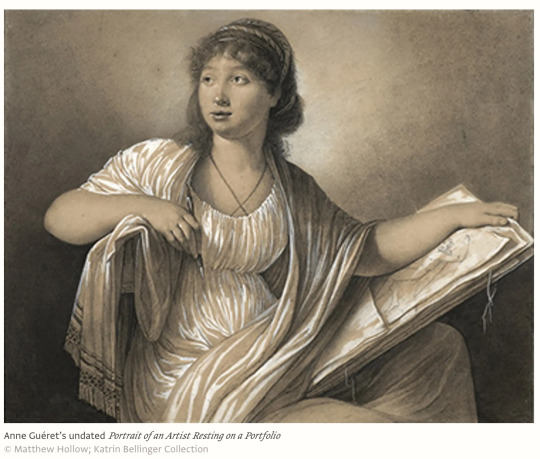

When talking about women artists, it is usual to reference Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? As Paris Spies-Gans—independent scholar and author of this new book—rightly says, it was a call-to-arms to make them visible. But that was over 50 years ago. One may ask now, what has changed since then? In recent years, the answer is a lot.

Around the world there has been a mini-flood of monographs and exhibitions on historic women artists, and their work is suddenly a profitable art market commodity. How to assess their careers remains a question, however. What was their place in and contribution to the art worlds they inhabited? Of what we know of them, what is inherited stereotyping on the one hand or over-eager feminist reading on the other? And to what extent is the current vogue for their work merely diversity box-ticking rather than genuine recognition?

This book sets out to place women artists working in Britain and France between 1760 and 1830—the “Age of Revolutions”—firmly within the art-historical narratives of the period. The task, Spies-Gans argues, demands more intellectual rigour than simply enhancing knowledge of their existence; and in an ideal world it should go beyond dealing with their careers as separate, simply because of their gender. A detailed analysis of the records of public exhibitions in London and Paris, chiefly the Royal Academy of Arts and the Académie Royale respectively, lies at the heart of this survey.

When talking about women artists, it is usual to reference Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? As Paris Spies-Gans—independent scholar and author of this new book—rightly says, it was a call-to-arms to make them visible. But that was over 50 years ago. One may ask now, what has changed since then? In recent years, the answer is a lot.

Around the world there has been a mini-flood of monographs and exhibitions on historic women artists, and their work is suddenly a profitable art market commodity. How to assess their careers remains a question, however. What was their place in and contribution to the art worlds they inhabited? Of what we know of them, what is inherited stereotyping on the one hand or over-eager feminist reading on the other? And to what extent is the current vogue for their work merely diversity box-ticking rather than genuine recognition?

This book sets out to place women artists working in Britain and France between 1760 and 1830—the “Age of Revolutions”—firmly within the art-historical narratives of the period. The task, Spies-Gans argues, demands more intellectual rigour than simply enhancing knowledge of their existence; and in an ideal world it should go beyond dealing with their careers as separate, simply because of their gender. A detailed analysis of the records of public exhibitions in London and Paris, chiefly the Royal Academy of Arts and the Académie Royale respectively, lies at the heart of this survey.

Consistent presence

Unusually for an art history book, data is presented in the form of charts and graphs. It is a powerful way of pressing home the point that the handful of prominent names that make it into standard art histories, such as Angelica Kauffman and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, are not exceptions in a male-dominated world, but part of a much wider and neglected story. Women, it is demonstrated, were a consistent presence in public exhibitions throughout the period. More than 800 individual women artists exhibited in London, and at least 400 in Paris. This is an astonishing statistic. It blows apart the clichéd but hard-to-shift notions of women artists as few in number, pursuing careers that blurred the lines between professional and amateur.

In fact, Spies-Gans sees this period as one that witnessed the first collective rise of the professional female artist. Women used public exhibitions for exposure and opportunity. How they trained, what they chose to exhibit, their networks and commercial acumen, and the strategies they devised to overcome obstacles because of their gender, are examined over six chapters. Preconceptions are regularly challenged.

For example, rather than “still-life” and “flowers” (the lesser genres), most women exhibited portraiture. Maria Cosway’s striking image of the Duchess of Devonshire as the moon goddess Cynthia (1781-82) shows the sitter wrapped in ethereal clouds in a clever blend of “celebrity”, history and literary narrative. The French Academician (one of only four women) Adélaïde Labille-Guiard depicts herself at her easel with two attentive female pupils behind her. It is one of many self-portraits, or images of fellow female artists reproduced in the book that show women proudly in the act of creation. And it is one of many painted on a large scale, demonstrating ambition and painterly skill.

Another preconception, the idea that (broadly speaking) women did not practise history painting as they had no access to essential life-drawing classes, or, put about at the time, because they lacked the capacity for “invention”, is here successfully critiqued. Angélique Mongez, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, was one of many French women to exhibit large, complex classical narratives that incorporated nude figures while placing the focus on female protagonists. In this context, Kauffman’s decision to represent “Design”—one of four allegorical paintings for the ceiling of the Royal Academy—as female rather than male suddenly assumes more weight.

In support of its central and forceful point not to pigeonhole women along conventional lines, A Revolution on Canvas is illustrated mainly with portraits and historical works: those by Marie-Victoire Lemoine, Marie-Nicole Dumont (showing herself juggling painting and motherhood), Marie-Geneviève Bouliar and Marie-Denise Villers, or Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Adèle Romany and Constance Mayer, may come as a revelation to most readers. And yet, while applauding this desire to avoid stereotypes, perhaps the emphasis towards history and portrait painting, despite the data showing they were the two most exhibited genres (narrative in Paris was second to portraiture), has meant a drift from the complete truth. For the reality is that women did paint still-life, flowers and portrait miniatures. It was what artists such as Anne Vallayer-Coster did brilliantly. And where is landscape? The second most exhibited genre in London, we learn, but not discussed at all by Spies-Gans.

Revolutionary turmoil

Setting the context for women’s growing ambition to pursue creative, public careers was the era itself—the revolutionary turmoil that prompted debates about democracy and citizenship, which in turn shone a light on women’s rights. It was the age of the philosophical writings of Olympe de Gouges and Mary Wollstonecraft. Spies-Gans acknowledges the paradox in charting women’s increasing creative freedom at a time when political democracy did not extend to them. Another inevitable contradiction – in a book devoted to women artists—is the author’s call to embed their histories into broader art-historical narratives, rather than to continue to treat them separately. That, surely, is the ultimate goal.

But how many of the artists that are discussed in this book are genuinely recognisable names, and how many of the 1,200 named exhibitors are represented in public collections? It is still the case that when female artists are mentioned, the question “Were they any good?” still hovers. Books focused on gender are arguably still necessary. By making its points compellingly and driving the agenda forward, A Revolution on Canvas is an important contribution to the field.

Paris Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760-1830, Paul Mellon Centre/Yale, 384pp, 157 col and b/w illustrations, £45/$55 (hb), published 28 June (UK) and 5 July (US)

• Tabitha Barber is the curator of British Art 1500-1750 at Tate and was the lead curator and catalogue editor/contributor of British Baroque: Power and Illusion (Tate, 2020). She is currently preparing an exhibition on historic women artists to be staged at Tate Britain in 2024

#Women’s history#women in art#books for women#A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760 - 1830#Maria Cosway#Anne Vallayer-Coster#Anne Guéret

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

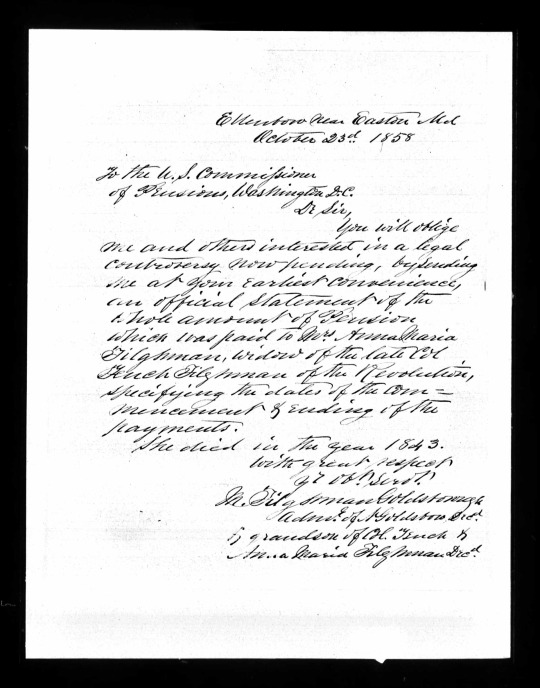

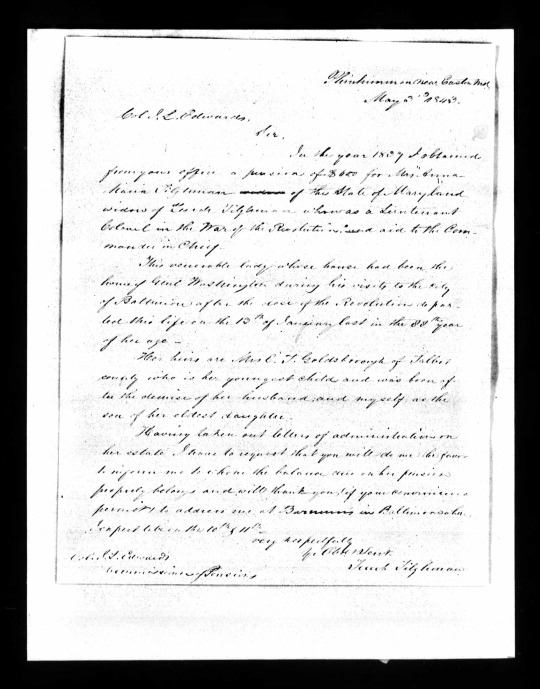

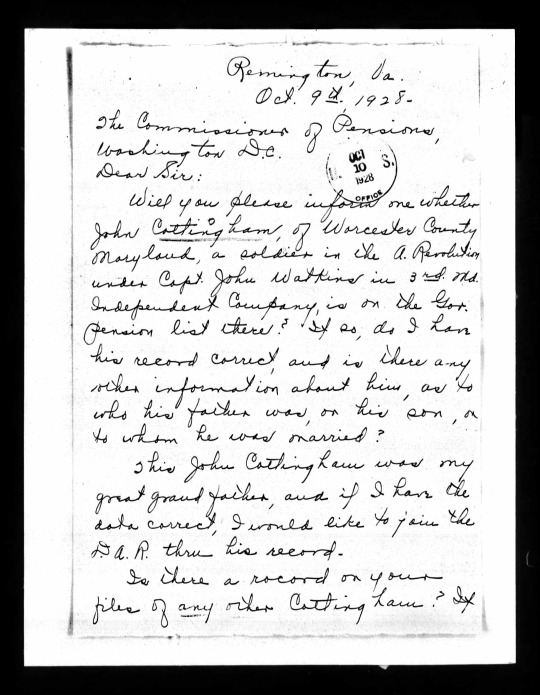

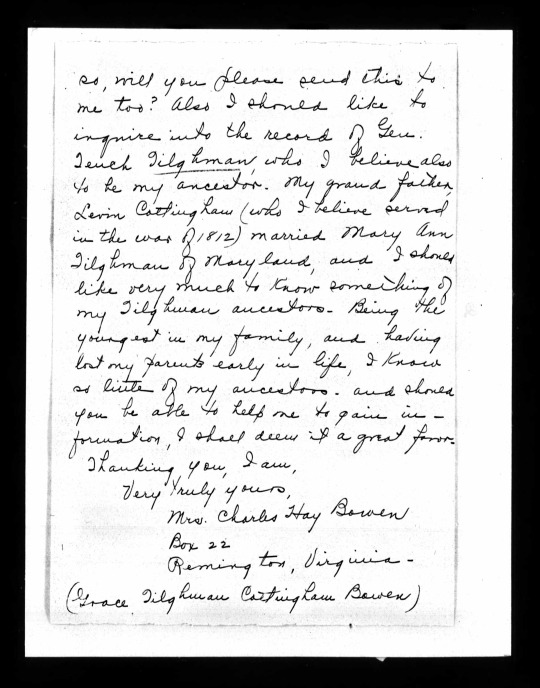

51 years later: Anna Marie Tilghman's widows pension

Tench Tilghman's gravestone, courtesy of Wikimedia.

Fifty-one years after Tench Tilghman's death, his wife (who was a cousin), Anna Marie Tilghman, got a widows pension. Tilghman was, as the Maryland State Archives argues, "one of Maryland's great patriots" due to his public service as part of a "commission established to form treaties with the Six Nations of Indian tribes," a captain in "the Pennsylvania Battalion of the Flying Camp.," and serving as an unpaid aide-de-camp to George Washington from August 1776 to May 1781 when Washington got him "a regular commission in the Continental Army." His final task was "he honor of carrying the Articles of Capitulation to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia." Other than that, the Maryland State Archives writes that Tench was

born on December 25, 1744 in Talbot County on his father's plantation. He was educated privately until the age of 14, when he went to Philadelphia to live with his grandfather, Tench Francis. In 1761, he graduated from the College and Academy of Philadelphia, which later became the University of Pennsylvania, and then went into business with his uncle Tench Francis, Jr. until just before the Revolutionary War. After the War, Tilghman returned to Maryland where he resumed his career in business in Baltimore and married his cousin, Anna Marie Tilghman. They had two daughters, Anna Margaretta and Elizabeth Tench. Tilghman died on April 18, 1786 at the age of 41.

His gravestone was placed in Talbot County's Oxford Cemetery long after his death. That's because he died at St. Paul's Church in Baltimore, with the remains brought from there to Talbot County in 1971 but the original gravestone, without the plaque, does tell something about him.

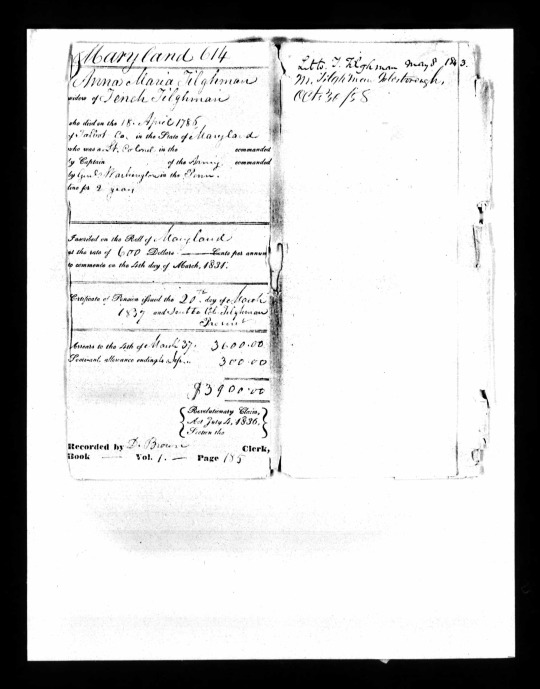

The widows pension by Anna Maria Tilghman tells an interesting story. [1] The first page shows that not only is it a penson for Anna Maria but that Tench also received a land grant, with "B.L.W.T." noting an "application for a warrant for bounty land" promised to him since he "served to the end of the war":

The next page notes that Tench died on April 18, 1786 in Talbot County, MD and was a Lieutenant Colonel serving in the army commanded by General George Washington, specifically in the Pennsylvania line, for two years. This is despite the fact he served for longer than two years as noted earlier in this article. For all of this, she would receive almost $4,000.00 a year, a sizable sum at the time when she was filing (May 1843):

The next page doesn't say much else other than that her claim would be processed in Maryland under the 1836 Pension Act covering veterans of the war with Britain from 1812-1815 and the Revolutionary War:

The page following is a personal appeal by her on February 24, 1837 in which she, before the Talbot County Orphans Court notes that she is the widow of Tench who serves as an Aide to Camp to George Washington and Lt. Colonel in the PA line, serving in total from January 1, 1777 to November 3, 1783. She also notes that she married Tench on June 9, 1783, and that he died on April 18, 1786:

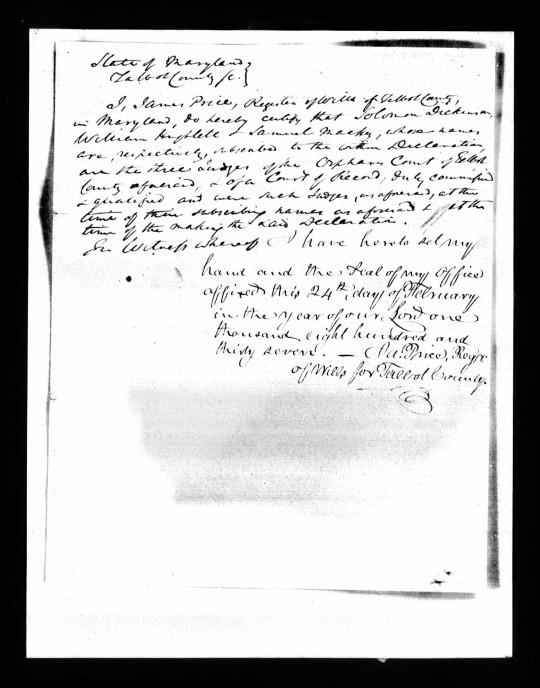

The next page is a judge on the Orphans Court in Talbot County, James Price, certifying her declaration is correct, nothing more, nothing less:

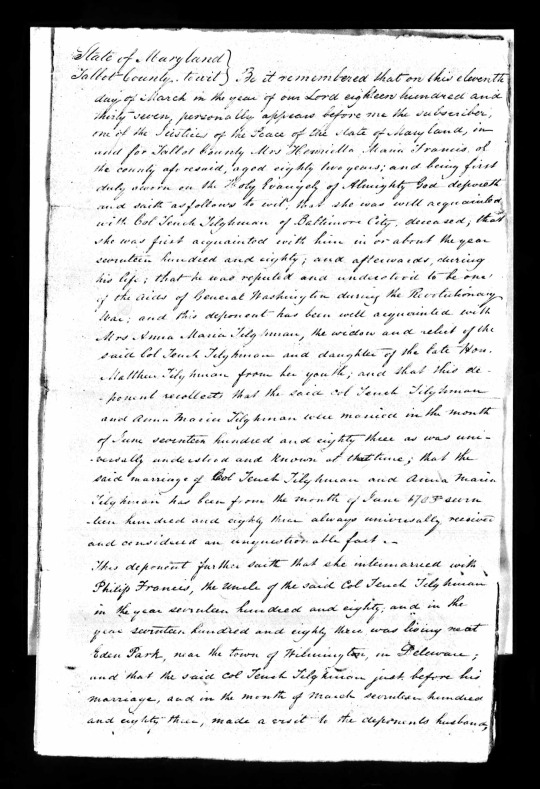

Then on March 11, 1837 a 82-year-old woman named Henrietta Maria Francis appeared before the Talbot County Orphans Court. She said she was "well acquainted with Col Tench Tilghman of Baltimore City," noting that she first met him in 1780, noting that through the years it was recounts how he was an aide-de-camp of George Washington. She was also, of course, familiar with Anna Maria Tilghman, saying that she was the daughter of one Matthew Tilghman, noting also that they were both married in June 1783. Clearly she was related on a familial level to Tench: her husband, Philip Francis, was Tench's uncle, whom Tench visited in March 1783 after their marriage.

She adds that Tench died three years after she married Philip Francis, with Anna Maria (called she after this section) having one daughter before Tench's death, and another after Tench died (she must have been in labor when Tench died), and has since stayed as a widow. Others writing below her attest to the veracity of this statement:

By October 1858 it is asserted that Anna Maria died in 1843, with another Tilghman (M. Tilghman Goldborough) filing a continuing claim as they inherited her estate interestingly:

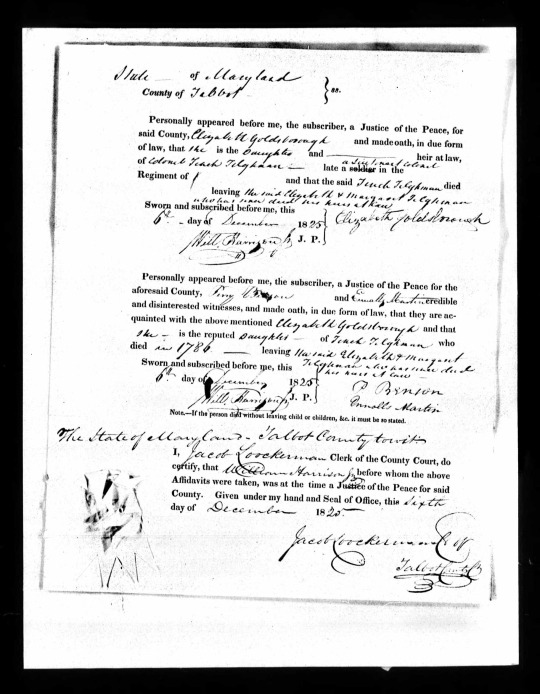

From there, Elizabeth Goldborough, likely the mother of the above listed M. Tilghman Goldsborough, turns out to be the daughter of Anna Maria and Tench! It is also noted that her sister is named Margaret who died, leaving her the only heir. This document, issued by a Talbot County Justice of the Peace in December 1825, shows that Margaret and Elizabeth were children of Anna Maria and Tench Tilghman without a doubt:

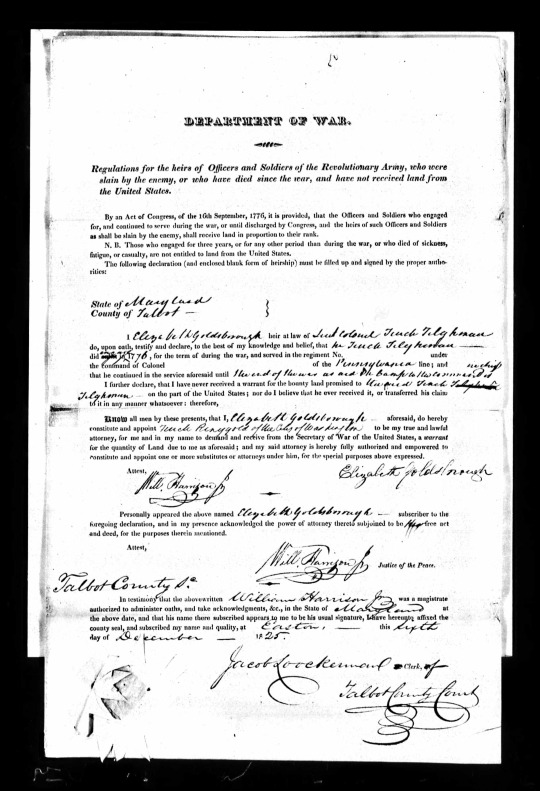

The pension goes on to say that Elizabeth is an heir of Tench Tilghman, and quickly notes Tench's military service:

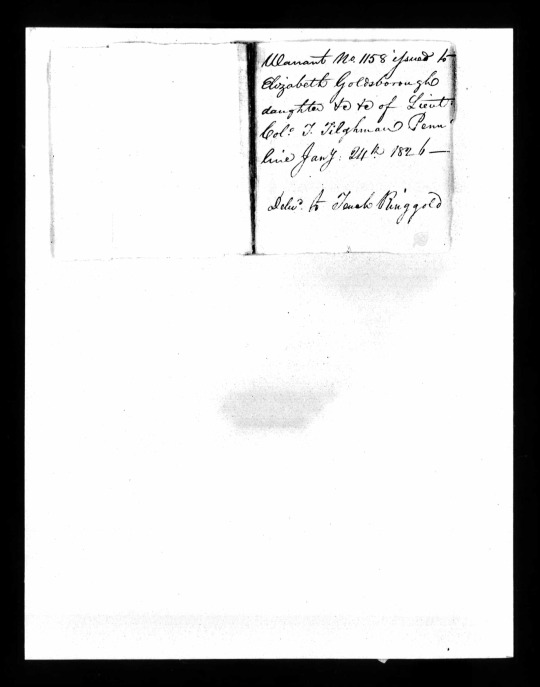

The next page makes it clear that all of those previous pages specifically related to a bounty land warrant claim, which is wrapped up within the pages of Tench's pension papers, making it possible for Tench's wife Anna Maria to apply for a widows pension in 1837 and Elizabeth to apply for the bounty land warrant in 1825, for her son to come back in the 1850s saying that now want to apply for the pension. This page makes it clear that Elizabeth's request was granted in January of 1826:

In May 1929, the War Department tried to sort all of this out. As they summarized, it was clear that Tench served from January 1, 1777 to November 3, 1783 as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army and an aide-de-camp to General Washington, dying on April 18, 1783. They also summarized how Tench married Anna Maria on June 8, 1783, allowed a pension on February 13, 1837but died on January 18, 1843. They also wrote that they had two children, Elizabeth and Margaret with the former child marrying a man named Goldsborough of Talbot County, Maryland, while the latter had a son named Tench Tilghman, marrying a man whose name is not yet known.

The final page says that a "grandson" named M. Tilghman Goldsborough is referred to in 1858 but no other family data is known.

The next page just notes Anna Maria's widows pension claim:

In May 1843, a man named Tench Tilghman said that he obtained a pension claim for a Mrs. Anna Maria Tilghman, widow of Tench in 1837, noting that Anna Maria died January 13, 1843 at age 88, if I read that right. He further notes that the youngest daughter of Anna Maria and Tench, Elizabeth ("Mrs. C.T. Goldsborough"), who was noted earlier, is an heir, while he is the son of the the older daughter, Margaret. As such, he asks the pension commissioner to whom the pension now belongs:

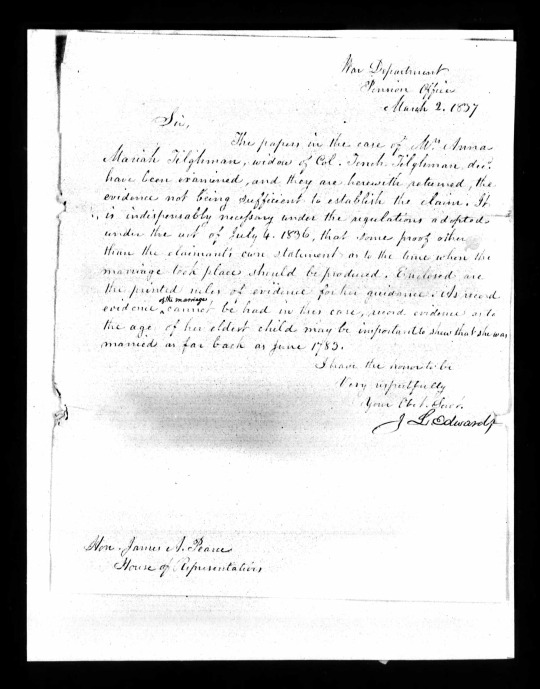

Then there is an earlier letter from J.L. Edwards, the pension commissioner in March 1837, saying that the papers in the case of the pension are returned as the evidence is "not being sufficient to establish the claim" because of new regulations on pensions. Perhaps this is what prompted the second Tench's letter in 1843, for which a response is not known:

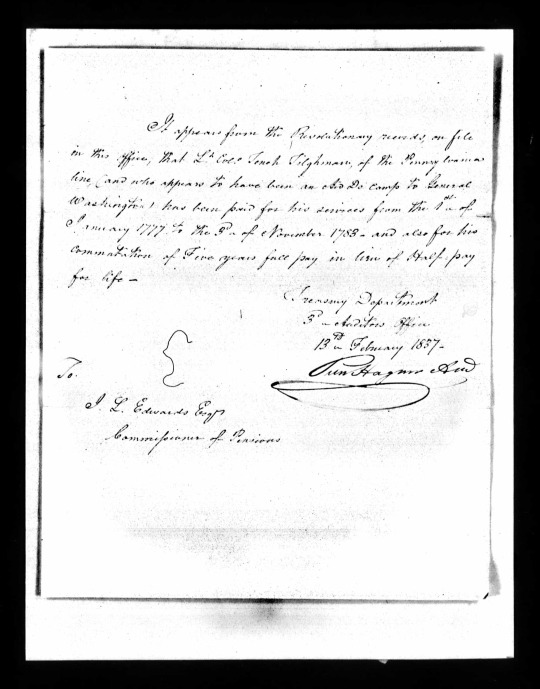

A further letter from J.L. Edwards, in March 1837, confirms that Tench did serve from January 1, 1777 to November 3, 1783:

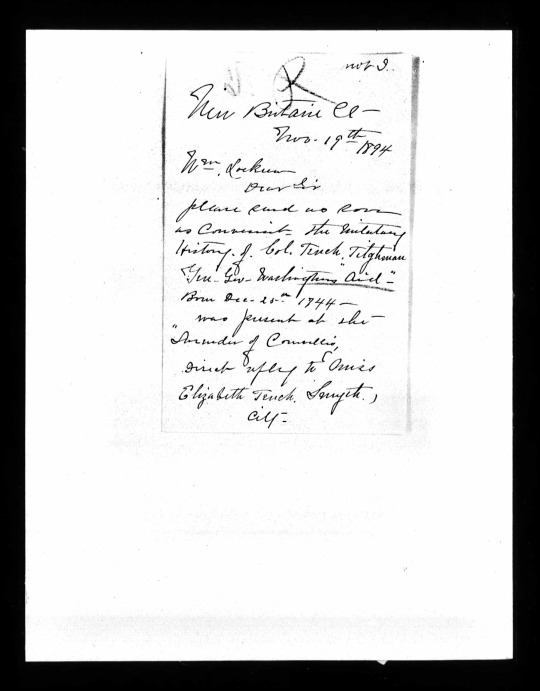

Then there is a letter from a later descendant in 1894 to the pension office about Tench's pension papers:

After that there is a 1928 letter by another descendant, Grace Cottingham Tilghman Bowen (who married a man named Charles Hay Bowen), leading to the response from the War Department as noted earlier in this post:

The second page specifically focuses on Tench:

There is much to be learned from this pension. For one, that Tench served as a Lt. Colonel and Aide-De-Camp from 1777 to 1783, and that he married Anna Maria Tilghman, his cousin, in June 1783 when she was 28 years old (born in 1755). Furthermore, it is also clear that he had two children with her, Margaret (older) and Elizabeth (younger), with the latter child born after the "demise of her husband" Tench. From there, Margaret later had a child named Tench Tilghman, meaning that she married a person with the surname of Tilghman, while Elizabeth married a man named C.T. Goldsborough and seemingly had a child named M. Tilghman Goldsborough. It is not known when Margaret or Elizabeth died, but only that Margaret was dead sometime before 1825 (when Elizabeth filed her claim for the bounty land), while Elizabeth lived until at least 1843. Furthermore, it is also noted that Tench lived in Baltimore where he met a woman named Henrietta Maria Francis, who was 25 when she was first "acquainted" with Tench, and she married a man named Philip Francis,the uncle of Tench, whom Tench visited in March 1783 after the marriage of Henrietta and Philip. All of this calls for another post to dig into this more, which will be coming to you from this wonderful blog next week!

© 2017-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] Pension of Tench Tilghman, 1837, B.L.Wt 1158-450, Widow's Pension Application File, W.9522, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15. Courtesy of Ancestry.com and Heritage Quest.

#gravestones#tench tilghman#wikimedia#pensions#military service#land grants#landowner#revolutionary war#american revolution#1830s#1780s#1770s#talbot county#marriage#cousins#estate#1850s#1840s#bounty land warrant#1820s#1890s#1920s

2 notes

·

View notes