#Richard Grove

Text

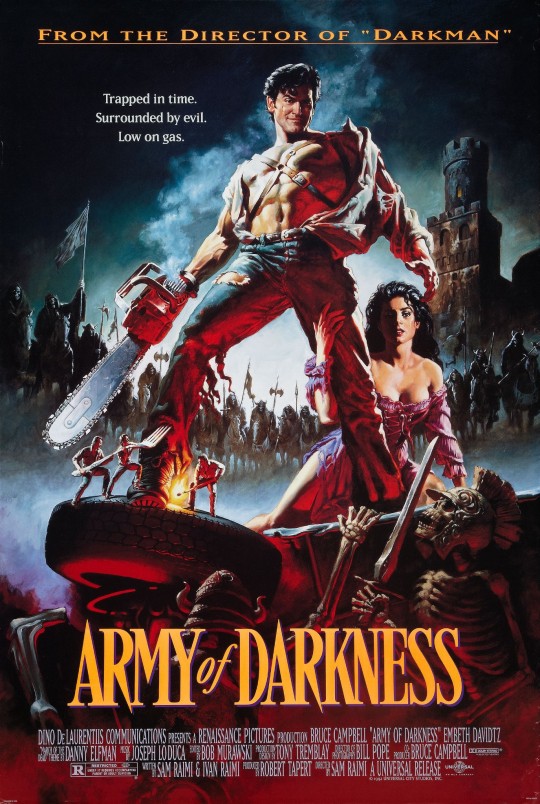

Army of Darkness (1992)

"Are all men from the future loudmouthed braggarts?"

"Nope. Just me, baby. Just me."

#army of darkness#evil deadology#horror imagery#horror film#1992#american cinema#sam raimi#ivan raimi#bruce campbell#embeth davidtz#marcus gilbert#ian abercrombie#richard grove#timothy patrick quill#bridget fonda#patricia tallman#michael earl reid#ted raimi#bill moseley#joseph loduca#danny elfman#i get why this is as beloved as it is but regretfully i think it's my least favourite of the og trilogy; i still had a whale of a time but#where fhe first film was a stripped down pared back bone chiller of an exercise in pure horror and the second built on that to stir in some#deeply funny absurdist black comedy‚ this one kind of foregoes the horror all together to concentrate on being a zany comedy film about a#fish out of water. ok so it's still quite gloopy in places‚ but the sense of dread‚ the palpable horror is gone. Campbell is still superb#of course and Ash is still very baby girl. but he and Raimi are mostly going for straight laughs instead of uncomfortable giggles#the laughing scene in ED2 is the perfect Moment of these films: an absolute nailing of the blend of disturbing uncanny with absurd ott goof#i missed that blend a little. still a great time like i say and still a worthy third film in an unlikely triumph of an indie trilogy

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#army of darkness#evil dead#horror#horror movies#fantasy#fantasy movies#movies#90s horror#90s horror movies#90s fantasy#90s fantasy movies#90s movies#90s#1990s#films#cinema#bruce campbell#richard grove#sam raimi

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Sixty-seven words that led to the creation of the State of Israel”

youtube

:

:

:

:

:

:

Reminder:

#rothschild#balfour declaration#city of london#cecil rhodes#Zionist#carroll quigley#antony sutton#richard grove#Alfred Milner#sullivan and cromwell#round table#think tank

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

x

#vuelta 2023#la vuelta 2023#la vuelta#dylan van baarle#richard plugge#jan tratnik#primoz roglic#kaden groves#grischa niermann#sepp kuss#wilco kelderman#robert gesink#remco evenepoel#jonas vingegaard

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

lucas' burthday is coming up in 20 days (yeah i know im getting to this a little late 😭 im so sorry) and i have put together this project so we can show him how much we appreciate him!

https://forms.gle/mMXrfXMtxpRLPVCN

@boolger @cannibalisticcorpse @nursestardust @desparikon @rosieblogstuff

https://forms.gle/mMXrfXMtxpRLPVCN

#lucas till#macgyver#cbs macgyver#macgyver 2016#angus macgyver#macriley#macdesi#macdoc#xmen first class#xmen apocalypse#alex summers#havok#halex#havbeast#banvok#havshee#sealex#hannah montana the movie#travis brody#the collective#son of the south#monster trucks#tripp coley#the curse of downers grove#bravetown#josh harvest#wolves#cayden richards#crush 2013#scott norris

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

«It is not because the Indo-Chinese discovered a culture of their own that they revolted. Quite simply this was because it became impossible for them to breathe, in more than one sense of the word.» – Frantz Fanon, (1952), Black Skin, White Masks, Translated from the French by Richard Philcox, Grove Press, New York, NY, 2008, p. 201

#graphic design#typography#book#cover#book cover#frantz fanon#richard philcox#grove press#1950s#2000s

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The three* versions of why Mick Jagger slept with Pat Andrews, the mother of one of Brian Jones' children

*UPDATED: 04/03/2024.

In Mick: The Wild Life and Mad Genius of Jagger by Christopher P. Andersen, this occasion is nothing more than a frankly unimaginative but evil plan by Mick to "break" the connection between Keith and Brian that arose when they started living together.

The entire narrative is built based on a timeline in which the three already live together in 102 Edith Grove. Describing that, while Mick was studying and had classes all day, Keith and Brian were alone in the apartment, rehearsing. And when it got cold, Keith and Brian would lie down together to stay warm.

In short, the book says that Brian and Keith were very close, and Mick wanted to break them up (it is also said that Mick realized that Brian was determined to replace him

with the singer P. P. Pond). Mick’s attitudes were: He seduced Pat Andrews, the mother of Brian’s son

Julian, and Brian himself.

In Keith Richards' biography, Life, there is a short excerpt about the incident that completely changes the narrative of Christopher P. Andersen's book because it differs in essentials: They didn't live in 102 Edith Grove yet. According to Keith:

Mick had

come back drunk one night to visit Brian, found he wasn’t there and

screwed his old lady. This caused a seismic tremble, upset Brian very badly

and resulted in Pat leaving him. Brian also got thrown out of his flat. Mick

felt a little responsible, so he found a flat in a dismal bungalow in

Beckenham, in a suburban street, and we all went to live there. It was there

I went in 1962 when I left home.

In Keith's version of the incident, the three did not live together yet, and Brian was only kicked from the place he lived with Pat after she slept with Mick. Therefore, this invalidates Andersen's entire story about this.

I'm not sure how Keith knew Mick was drunk, did Mick tell him that? Questionable, to say the least.

As far as I've read, over the two beds that were at 102 Edith Grove, Keith said:

There was

no fixed rotation between the two beds and a couple of mattresses. And it

didn’t really matter much; usually all three of us would wake up on that floor, where we had the enormous radiogram that Brian had brought with him, a great ’50s warm-up number.

So far, there are no explicit descriptions of sharing the bed to keep warm. Although he admits that "To go through

that winter of ’62 was rough. It was a cold winter."

Whether this is something he deliberately left out or if this was also an incorrect story, we can only speculate.

The third version of the story, from A. E. Hotchner's 1990 book, Blown Away: The Rolling Stones and the Death of the Sixties, collaborates with something of Christopher P. Andersen's version.

Hotchner interviewed many people, including Ian Stewart, who was part of the band's original lineup in the 60s and continued working with the Stones until his death. The following excerpt is Ian Stewart's version.

Even though he had moved to Edith Grove, Brian continued to see her and sometimes spent the night with her. Well, one afternoon Jagger came to the flat looking for Brian who wasn’t there. So Mick hung around, eventually got Pat to get into bed with him and knocked her off. Brian found out about it, of course, and from then on it was a thorn in his relationship with Mick — which, I guess, is what Mick intended. There were plenty of ready and willing girls Mick knew from the Ealing Club and the Marquee, so I figure the only reason he balled Pat, who was certainly not very attractive, was to get at Brian.

According to Ian Stewart, Mick, Brian, and Keith already lived together in Edith Grove, and Brian occasionally visited Pat, who lived alone with their son, Julian. This differs from Keith's report that they moved together after the incident between Mick and Pat. There is also no mention of Mick being drunk.

Obviously, the interview was done before Ian Stewart's death in 1985.

"The last time I saw lan Stewart, a few weeks before he died, I asked him [...]"

I'll update this post if I come across other versions.

In the end, everyone chooses what to believe, but as I am bringing excerpts from both books, I feel a bit of responsibility for pointing out the differences between them and letting everyone draw their own conclusions. That doesn't mean I'll make a post for every difference between the books, tho.

#this was not proofread 😪#the rolling stones#mick jagger#brian jones#keith richards#pat andrews#old rockstar#classic rock#rockstar gf#sixties#60s rock#60s#60s era#60s music#60s fashion#book quotes#quotes#life by keith richards#102 edith grove#Mick: The Wild Life and Mad Genius of Jagger#ian stewart#A. E. Hotchner#Blown Away: The Rolling Stones and the Death of the Sixties

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

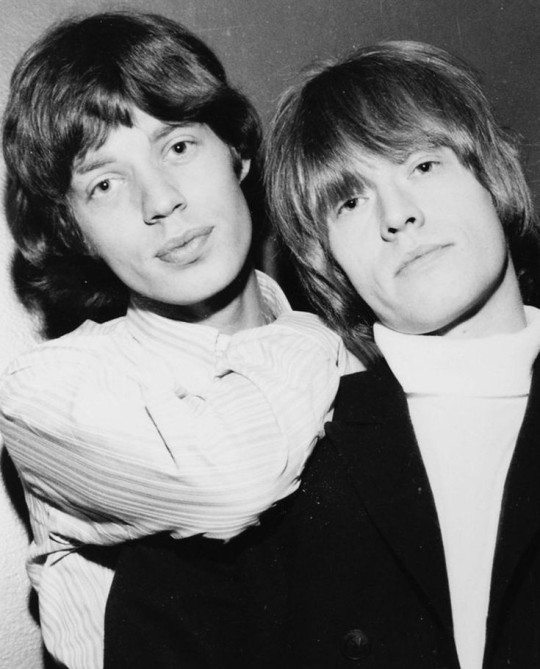

Summer Camp for the Powerful: The Power Elite at Bohemian Grove, 1994

G. William Domhoff

#g. william domhoff#bohemian grove#summer camp for the powerful#the power elite at bohemian grove#bohemian club#richard nixon#occult#monte rio#san francisco#california

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portobello road 1975

And no it’s not Kate Bush and Daryl Hall…

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

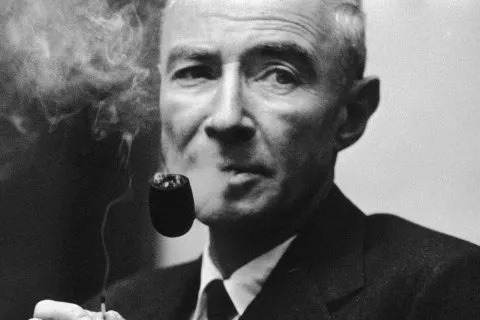

Why Robert Oppenheimer's Atomic Bomb Still Haunts Us

— By Richard Rhodes | Published May 15, 2013

Oppenheimer spearheaded the creation of the atom bomb. René Burri/Magnum

Robert Oppenheimer oversaw the design and construction of the first atomic bombs. The American theoretical physicist wasn't the only one involved—more than 130,000 people contributed their skills to the World War II Manhattan Project, from construction workers to explosives experts to Soviet spies—but his name survives uniquely in popular memory as the names of the other participants fade. British philosopher Ray Monk's lengthy new biography of the man is only the most recent of several to appear, and Oppenheimer wins significant assessment in every history of the Manhattan Project, including my own. Why this one man should have come to stand for the whole huge business, then, is the essential question any biographer must answer.

It's not as if the bomb program were bereft of men of distinction. Gen. Leslie Groves built the Pentagon and thousands of other U.S. military installations before leading the entire Manhattan Project to success in record time. Hans Bethe discovered the sequence of thermonuclear reactions that fire the stars. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi invented the nuclear reactor. John von Neumann conceived the stored-program digital computer. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam co-invented the hydrogen bomb. Luis Alvarez devised a whole new technology for detonating explosives to make the Fat Man bomb work, and later, with his son, Walter, proved that an Earth-impacting asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. The list goes on. What was so special about Oppenheimer?

He was brilliant, rich, handsome, charismatic. Women adored him. As a young professor at Berkeley and Caltech in the 1930s, he broke the European monopoly on theoretical physics, contributing significantly to making America a physics powerhouse that continues to win a freight of Nobel Prizes. Despite never having directed any organization before, he led the Los Alamos bomb laboratory with such skill that even his worst enemy, Edward Teller, told me once that Oppenheimer was the best lab director he'd ever known. After the war he led the group of scientists who guided American nuclear policy, the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He finished out his life as director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he welcomed young scientists and scholars into that traditionally aloof club.

August 9, 1945: Nagasaki is hit by an atom bomb. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/EPA

Those were exceptional achievements, but they don't by themselves explain his unique place in nuclear history. For that, add in the dark side. His brilliance came with a casual cruelty, born certainly of insecurity, which lashed out with invective against anyone who said anything he considered stupid; even the brilliant Bethe wasn't exempt. His relationships with the significant women in his life were destructive: his first deep love, Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley professor, was a suicide; his wife, Kitty, a lifelong alcoholic. His daughter committed suicide; his son continues to live an isolated life.

His Choices or Mistakes, Combined with his Penchant for Humiliating Lesser Men, Eventually Destroyed Him.

Oppenheimer's achievements as a theoretical physicist never reached the level his brilliance seemed to promise; the reason, his student and later Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger judged, was that he "very much insisted on displaying that he was on top of everything"—a polite way of saying Oppenheimer was glib. The physicist Isidor Rabi, a Nobel laureate colleague whom Oppenheimer deeply respected, thought he attributed too much mystery to the workings of nature. Monk notes his curiously uncritical respect for the received wisdom of his field.

Monk's discussion of Oppenheimer's work in physics is one of his book's great contributions to the saga, an area of the man's life that previous biographies have neglected. In the late 1920s Oppenheimer first worked out the physics of what came to be called black holes, those collapsing giant stars that pull even light in behind them as they shrink to solar-system or even planetary size. Some have speculated Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel for that work had he lived to see the first black hole identified in 1971.

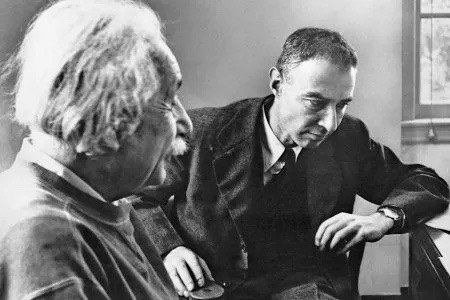

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein, circa the 1940s. Corbis

Oppenheimer's patriotism should have been evident to even the most obtuse government critic. He gave up his beloved physics, after all, not to mention any vestige of personal privacy, to help make his country invulnerable with atomic bombs. Yet he risked his work and reputation by dabbling in left-wing and communist politics before the war and lying to security officers during the war about a solicitation to espionage he received. His choices or mistakes, combined with his penchant for humiliating lesser men, eventually destroyed him.

One of those lesser men, a vicious piece of work named Lewis Strauss, a former shoe salesman turned Wall Street financier and physicist manqué, was the vehicle of Oppenheimer's destruction. When President Eisenhower appointed Strauss to the chairmanship of the AEC in the summer of 1953, Strauss pieced together a case against Oppenheimer. He was still splenetic from an extended Oppenheimer drubbing delivered during a congressional hearing all the way back in 1948, and he believed the physicist was a Soviet spy.

Strauss proceeded to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance, effectively shutting him out of government. Oppenheimer could have accepted his fate and returned to an academic life filled with honors; he was due to be dropped as an AEC consultant anyway. He chose instead to fight the charges. Strauss found a brutal prosecuting attorney to question the scientist, bugged his communications with his attorney, and stalled giving the attorney the clearances he needed to vet the charges. The transcript of the hearing In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.

Rabi was one of the few witnesses who stood up for his friend, finally challenging the hearing board in exasperation, "We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it [because of Oppenheimer's work], and what more do you want, mermaids?" What Strauss and others, particularly Edward Teller, wanted was Oppenheimer's head on a platter, and they got it. The public humiliation, which he called "my train wreck," destroyed him. Those who knew him best have told me sadly that he was never the same again.

For Monk as for Rabi, Oppenheimer's central problem was his hollow core, his false sense of self, which Rabi with characteristic wit framed as an inability to decide whether he wanted to be president of the Knights of Columbus or B'nai B'rith. The German Jews who were Oppenheimer's 19th-century forebears had worked hard at assimilation—that is, at denying their religious heritage. Oppenheimer's parents submerged that heritage further in New York's ethical-culture movement that salvaged the humanism of Judaism while scrapping the supernatural overburden. Oppenheimer, actor that he was, could fit himself to almost any role, but turned either abject or imperious when threatened. He was a great lab director at Los Alamos because of his intelligence—"He was much smarter than the rest of us," Bethe told me—because of his broad knowledge and culture; because of his psychological insight into the complicated personalities of the gifted men assembled there to work on the bomb; most of all because he decided to play that role, as a patriotic citizen, and played it superbly.

Monk is a levelheaded and congenial guide to Oppenheimer's life, his biography certainly the best that has yet come along. But he devotes far too many pages to Oppenheimer's Depression-era flirtation with communism, a dead letter long ago and one that speaks more of a rich esthete's awakening to the suffering in the world than to Oppenheimer's political convictions. He doesn't always get the science right. Most of the errors are trivial, but a few are important to the story.

Their Fundamental Objection Was to Giving up Production of Real Weapons so That Teller Could Pursue His Pipe Dream, a Dead-end Hydrogen Bomb Design.

A fundamental reason Oppenheimer opposed a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in response to the first Soviet atomic-bomb test in 1949 was the requirement of Edward Teller's "Super" design for large amounts of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium. Tritium is bred by irradiating lithium in a nuclear reactor, but the slugs of lithium take up space that would otherwise be devoted to breeding plutonium. To make tritium for a hydrogen bomb that the U.S. did not know how to build would have required sacrificing most of the U.S. production of plutonium for devastating atomic bombs the U.S. did know how to build. To Oppenheimer and the other scientists on the GAC, such an irresponsible substitution as an answer to the Soviet bomb made no strategic sense. It's true that the hydrogen bomb with its potentially unlimited scale of destruction made no military sense to them either—and was morally repugnant to some of them as well. But their fundamental objection, which Monk overlooks, was to giving up production of real weapons so that Teller could pursue his pipe dream, a dead-end hydrogen bomb design that never worked.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967)

More egregious is Monk's notion that the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, Oppenheimer's mentor during the war on the international implications of the new technology, pushed for the bomb's use on Japan to make its terror manifest. He did not. He pushed, to the contrary, for the Allies, the Soviet Union included, to discuss the implications of the bomb prior to its use and to devise a framework for controlling it. Bohr foresaw that the bomb would stalemate major war, as it has, but correctly feared that U.S. secrecy about its development would lead to a U.S.-Soviet arms race. He conferred with both Roosevelt and Churchill about presenting the fact of the bomb to the Russians as a common danger to the world, like a new epidemic disease, that needed to be quarantined by common agreement. Churchill vehemently disagreed, and Roosevelt was old and ill. The moment passed. The arms race followed, as Bohr foresaw, and with diminished force, among pariah states like Iran and North Korea, continues to this day.

Monk's Oppenheimer is a less appealing figure than the Oppenheimer of previous biographies, perhaps because, as an Englishman, Monk is less susceptible to Oppenheimer's rhetorical gifts and more candid about calling out his evasions. He pulls together most of what several generations of Oppenheimer scholars have found and offers new revelations as well. Yet there's a faint whiff of condescension in his portrait, and the real Oppenheimer, the man whom so many loved and admired, still somehow escapes him. He misses the deep alignment of Robert Oppenheimer's life with Greek tragedy, the charismatic hubris that was his glory but also the flaw that brought him low. But maybe I'm expecting too much: maybe only a large work of fiction could assemble that critical mass.

#Robert Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Richard Rhodes#World War II#Manhattan Project#Ray Monk#Gen. Leslie Groves#Pentagon#Hydrogen Bomb#Edward Teller | Stanislaw Ulam#Nobel Prize#Princeton University#Albert Einstein#President Eisenhower#Lewis Strauss#Hydrogen | Tritium | Plutonium#Roosevelt | Churchill#US — Soviet Union

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally have time to do some giffing of Oppenheimer, so if you guys have any requests please send them in and I'll gif them!!!

I, of course, already am doing all of Lawrence's scenes but if you guys have any others that you would like to see, please let me know.

#oppenheimer#Oppenheimer movie#christopher nolan#Chris nolan#Cillian murphy#j Robert oppenheimer#Robert oppenheimer#Ernest lawrence#josh hartnett#benny Sadie#Edward teller#Leslie groves#matt damon#Casey affleck#colonel pash#Richard feynman#jack quaid

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Scotland Yard: Reunion (1.12, LWT, 1972)

"It's not his style!"

"And Clifford's not a very pleasant character."

"What's that supposed to mean?"

"Just I think he's being getting under your skin."

"Well, he'd get under anybody's skin."

"Because he got away with it, before?"

"There are no facts to prove that Clifford wasn't there. Just as there were no facts to prove that he wasn't a party to the bank job, but you and I and every man in this force know that he was."

"And there's damn all we can do about it. Look, I'm not stitching him up just because he happens to have made idiots of us in the past; we have to prove, conclusively, without supposition, who killed Gemmell."

#new scotland yard#reunion#1972#classic tv#lwt#david cunliffe#nicholas palmer#john woodvine#john carlisle#robin ellis#sharon duce#virginia stride#richard hampton#tom criddle#pauline stroud#andrew armour#donald groves#john laker#terence conoley#john devaut#by the numbers 70s cop drama which does very little to distinguish itself from any other of the many contemporaries it had#Except that it finally gives us a little development of the Woodvine and Carlisle relationship. way back in ep 4 there was a throw away#line to the effect that Carlisle is really here to study and to learn from an officer of Woodvine's experience and reputation; here we#finally (finally!) get an actual sense of that being true‚ as Woodvine leads Carlisle to a few deductions and crucially tells him to handle#the finále of the episode (the apprehension of an armed fugitive) as he sees fit; but with it implicitly understood that Woodvine will be#watching and assessing how Carlisle handles the situation. a pre Poldark Ellis and the ever lovely Virginia Stride are the heart of the#episode as a married couple separated by his conviction for a bank robbery; much is made of what a harsh sentence he received but actually#by the standards of today seven years sounds almost progressively lenient... Stroud's WDC reappears and gets named briefly in dialogue but#alas I've already forgotten what she was called... apologies. she's still mostly relegated to making tea. quelle surprise

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oppenheimer (2023)

#2023#film#movie#WWII#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Matt Damon#Leslie Groves Jr.#Cillian Murphy#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Julius Robert Oppenheimer#Emily Blunt#Kitty Oppenheimer#Robert Downey Jr.#Lewis Strauss#Josh Hartnett#Ernest Lawrence#Florence Pugh#Jean Tatlock#Jack Quaid#Richard Feynman#Gary Oldman#Harry S. Truman#Manhattan Project#Trinity#Los Alamos#New Mexico

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

:::

:::

:::

.

.

:::

:::

:::

REMINDER:

:::

:::

How the Zionists hitched a ride on the Imperialist bandwagon

.

#rothschild#balfour declaration#Sullivan and Cromwell#israel#ziocon#antony sutton#tragedy and hope#rothschild agent#neocons#neolibs#carroll quigley#CIA#Richard Grove

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 101ers play at The Elgin pub , Ladbroke Grove , London , England , 1975 .

©️ Julian Yewdall/Getty Images

#joe strummer#richard dudanski#simon cassell#marwood “mole” chesterton#101ers#pub rock#proto punk#R&B#rockabilly#the elgin#ladbroke grove#london#england#1975#julian yewdall#getty images

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

'During the middle of World War II, teenage physics major Roy Glauber found himself plucked out of college on the East Coast and assigned to work at a mysterious new government research center in the far-off deserts of New Mexico.

His destination turned out to be a laboratory at Los Alamos, a part of the Manhattan Project, where he was assigned to work under groundbreaking theoretical physicist Hans Bethe to help calculate the smallest amount of fissionable material—the critical mass—needed to set off a sustained nuclear reaction.

Glauber was one of the youngest scientists in the 1,400-person Los Alamos staff, and afterward he went on to a distinguished career in physics, earning a doctorate—and later becoming a professor—at Harvard University. His work focused on a wide variety of topics, including quantum dynamics, the collisions of high-energy particles such as hadrons, and the behavior of light particles, especially in clarifying how light had the characteristics of a wave and a particle simultaneously. In addition to his research, Glauber was known for his sense of humor, such as being the official “keeper of the broom” at an annual mock scientific conference sponsored by what has been called the MAD magazine of science, where his role was to sweep the stage clean of paper airplanes. (It’s become a tradition for members of the audience to throw paper airplanes at the stage to celebrate the end of the night’s proceedings.)

In 2005 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for physics; some years later, the 91-year-old Glauber attended the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, where he agreed to an interview with me. Sadly, he died a year-and-a-half later, in 2018.

In this interview, one of the last surviving eyewitnesses from the effort to build the first atomic bomb gives his impressions of that project’s driving force—the director of the Los Alamos lab, J. Robert Oppenheimer. Glauber describes what it felt like to be working there as a young physicist; experience the overwhelming need for secrecy—and witness the test explosion of the first atomic bomb.

Dan Drollette Jr: To start things off, I thought we might look at these photos on my laptop of 1940s security ID badges from Los Alamos. As you can see, each one has a name, an ID number, and a kind of small black-and-white photo—but at least they each show the individual faces of the people who worked there at the time.

Roy Glauber: Oh, yes. (Looks through array of photos on screen.)

There’s Dorothy McKibbin.

And there’s a very young Richard Feynman. Though they all look young.

You know, there was very little sense at Los Alamos at the time that any history was being enacted which would be of interest after the war was over. So, there was very, very little photography devoted to the individuals.

Although there was a large photographic division, which photographed all the experiments—including all the failures, and there were vast numbers of those. (Laughs.)

But there was not much on simply recording the way people lived, and where we hung out.

Drollette: I like that smirk on Feynman’s ID photo. It’s a funny expression.

Glauber: Well, for all intents and purposes, he was the resident clown. You would often find that wherever people gathered for lunch, there would always be a little knot of about half-a-dozen women all in the corner, laughing—and in the center would be Feynman, telling stories. He really made quite an entertainer of himself. He happened also to be possibly the brightest young mathematician in the place. I met Feynman in the year 1943, when I arrived there.

Drollette: And how old were you when you went to Los Alamos?

Glauber: I was 18.

Drollette: From the description you gave for an oral history about the Manhattan Project, it sounded like they didn’t tell you much about what you were getting into.

Glauber: That was a matter of security, of course.

But I quickly got a general impression of what might be in the air, because the story of fission had been really big just a few years earlier, in 1939. All during the middle ‘30s, Fermi had been subjecting many elements to irradiation by neutrons… By 1938, he was doing it with uranium. He found all sorts of funny particles flying out, which he could not analyze, and which were found to have strange chemical properties. And researchers had developed the idea that maybe they might be evidence of the fissioning of uranium.

That was a really great discovery, which then led to speculation about the possibility of a chain reaction. It made a big stir in the newspapers for a time, and it was an exciting story, at least for a kid like me.

But then it all just … disappeared. Not another word about it. There was speculation that fission might have some strategic importance, and so it was declared secret, at least in America. And one really heard nothing more of it, in the several years that followed. The story went subsurface. It just went nowhere.

Drollette: But you had a general kind of sense?

Glauber: Well, I don’t know if I’d say that, but that was what had been going on in the background. All I knew for sure was that we were at war, I was in college, I’d registered for the draft, and I was expecting to be going directly into the armed forces….

But suddenly other things began to happen … and happen quite rapidly. It all started quite soon after I filled out this questionnaire that had arrived from Washington, from an organization which has almost never been heard of before or since, called the “National Roster of Scientific Personnel.” It was intended to put people who were trained and with the right skills into the right places—and there was a great shortage of people who were well-trained.

While filling out that questionnaire I wrote down that I had taken all these courses, which were almost all things that one takes much later, in graduate school. So, to make a long story short, they came and got me—I received instructions to leave Harvard as soon as one could leave that school term and get a ticket for the first train to Chicago.

Drollette: But weren’t you only in your first year of college?

Glauber: Well, you have to understand that by ’43, they were tired of drafting older men—particularly those with families. They wanted young guys for the military. And it all makes sense, given my personal history: I had skipped some grades in high school—which was much more common back then, when they really pushed people forward academically, regardless if they were really mature enough—and I’d been involved in all kinds of science projects, and a high school teacher had given me some books on calculus. Which all meant that I got a little ahead.

And then after I did get into college, all the professors started leaving to go work in the war effort, and the college administration announced that this would be the last chance for many of us to take some of the more advanced courses for the duration of the war. So, the whole education business was kind of telescoped for us—meaning that I had all these graduate-level classes on my school record.

Drollette: What happened next?

Glauber: It was very secretive; they would not say where one was going after Chicago. After I got there, I had to make a phone call to someone at some agency, who gave me another train ticket that turned out to go to a place in New Mexico I’d never heard of, called Lamy—not much more than a wooden boardwalk for a station. And it was there that I was supposed to get off, and someone would meet me. Meanwhile, any personal belongings I wanted to ship out—books and clothing—would go to a post office box. I still remember the address: Post Office Box 1663, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Well, I had never been west of Chicago. So that alone was quite an exciting business for me, riding on the Santa Fe Railroad, seeing bona fide cowboys, and watching people who were bronze in color and wearing furs and blankets get on the train.

When I got to Lamy, I was met by a tall, slender fellow who to all intents looked like a cowboy: He literally had a 10-gallon hat and wore a checked yellow shirt and dungarees. And this cowboy picked up not only me from the train but a short man with a derby hat and a navy-blue overcoat who also got off at that same stop—whom I later found out was John von Neumann.

The most remarkable thing was the geography. I’d never seen anything quite like that before; mesas and gulches and mountains, with narrow roads dug into the sides of canyon walls…

And this chap, this cowboy figure I’ve described to you, was a mathematician that previously worked with Neumann, and they started talking about what was going on in “the research up on ‘the Hill.’ ”

They had to resort to this way of talking, because they felt that was what one had to do in order to preserve the lab’s secrets—they didn’t know my state of clearance at all. So they described in terms appropriate to them the terrible things that were going on in a particular computation. It was not in the real world, but they were describing it as if it were the real world.

The fact that matter was being annihilated was to them a simple description of a mathematical mistake, while to me it was a description of the most incredible feats going on in the real world. So it was a very unusual sort of introduction to this kind of life.

Drollette: What were your first impressions?

Glauber: Well, I mentioned the geography: all canyons and plateaus. Los Alamos was placed in a virtually impassable area, miles from the nearest town. At the stage that I got there, there were still some log houses remaining from what had formerly been the Los Alamos Ranch School for Boys—a tuberculosis sanatorium—and the beginnings of more new structures. They had started putting up dormitories and some small apartment buildings a few months earlier, but none of them had space for more than four apartments with small families.

And there were quite a few small families, and many families that got appreciably larger. It had one of the busiest maternity hospitals, I think, that were run anywhere by the US Army. (Laughter.)

You have to understand that these were all young people; the older people didn’t want to go to this godforsaken location.

Drollette: What was the very first day of work like at the Manhattan Project?

Glauber: The first morning I was there, I was given a list of people to march around and meet. It was as if they had to compete for new personnel—to speak up and say “I want the new guy.”

Out of them all, I best remember an interview with Robert F. Bacher, who was head of the physics division.

On meeting me for the first time, Bacher said: “I bet you’re interested in what we’re working on here.” And I said I didn’t know.

So he said: “What’s your best guess? What do you think we’re working on?” He was asking me—an 18-year-old!

So I told him that “Judging from the treatment that the story had been given by the newspapers earlier, you’re probably trying to create a chain reaction based on fission.”

He said: “Well, that’s a very erudite guess. But I have to tell you, we succeeded in doing that a year-and-a-half ago”—he was describing the fact that they had indeed gotten a reaction to occur in Chicago, although that had nothing to do with Los Alamos.

And he added: “I have to tell you, however, that we are indeed working on a chain reaction here, it just happens to be a fast chain reaction, not a slow one.” And he then went on to explain that it was a bomb.

I was really quite upset by that—the notion that this was not going to be so much about a gift to mankind, but a weapon.

And it did take some weeks and months to overcome that feeling … and to discover that there were really interesting mathematical problems involved in making this bomb. And those really did keep me busy for the next two years.

So anyway, that’s how I learned what the story was.

Drollette: Was there any kind of orientation?

Glauber: There was something called the Primer, which you had to go and read—a sort of text for beginners. It was available in the library, and you had to sign out a copy, where you could learn of all of the speculations about the bomb that had been voiced in the months earlier.

Drollette: Were you at the Trinity Test?

Glauber: Well, how to put this… I saw it. (Laughs.)

They didn’t want us to fear its presence, so it was okay to view it from a distance.

But I had no authorization, if that’s what you mean. Just as important, there was also a considerable shortage of transportation. Very few people had cars at Los Alamos, and gasoline rationing meant you couldn’t go very far, anyway.

Luckily, I did get a lift to a mountain near Albuquerque, to the only place where a road goes to a really high altitude at that area, called Sandia Peak… I think there may have been 20 or 30 people altogether who went to the top of Sandia to try to see that test.

Unfortunately, we had no radio contact with the people running the Trinity Test, which was on a plain almost due south of Albuquerque. Now, we knew the test was supposed to be a couple of hours after midnight. But there was, in fact, a lightning storm at that time so it was delayed. I don’t know if lightning was striking right there at that testing spot—but frankly, it would have been very scary to be anywhere near there, because the bomb was held in a 100-foot-tall steel tower. And the lightning striking around there would have had a considerable chance of striking that tower.

Anyway, after a while, we saw some flashes, little flashes—which would have been considerable disappointments.

So by 5:30 in the morning, nearly everyone had left, because you got tired of just sitting there with no indication of when it was going to happen.

But I was a little more stubborn. The others had left, but I was sitting there facing in that direction when at 5:30 in the morning, it was as if the sun was rising from the south.

Drollette: So you saw it?

Glauber: I saw it. (Pause.)

Drollette: That must have been some experience.

Glauber: Yes. (Pause.)

Drollette: What was Oppenheimer like?

Glauber: He was a remarkable choice. Oppenheimer was an ultra-intellectual American, and he loved to express himself in poetic images and phrases. When he was in college—I think it took him only three years to go through Harvard—he developed the knack of reading Sanskrit and a passion for Indic poetry. Now, I can’t begin to tell you how deep or how accurate his knowledge was of these areas—none of us could. There was no one else at Los Alamos who knew about this sort of thing.

But he had studied it, and he used those phrases often. Oppenheimer used them particularly to describe the unearthly things that one saw in a nuclear explosion. He had a passionate involvement with expressing himself in literary language. He did not speak the ordinary language of New York, which many of us did.

Drollette: You’re referring to his comment “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”?

Glauber: Exactly, exactly.

So he was very different. He did not sound like a typical American leader at all. Yet somehow all of us respected that—and even admired that. He was about as opposite an individual as you could imagine from General Groves. They were like two polar opposites.

But they often appeared together in public—the leader of the science side and the leader of the military part. They were very careful that at important, strategic times, they would both appear together. There was something really symbolic about that, and you’ll notice it in many of the photographs.

Drollette: Let’s see if I can call it up on the screen—okay, here’s the ID badge photo of Oppenheimer.

It’s not very good, more like the picture you have on your driver’s license. But even in the security picture, I get a sense of him as being sort of otherworldly.

Glauber: That’s a good word. He acted otherworldly, a little. Women found him somewhat strange.

I knew one woman he had gone with before he married, and she thought that he behaved very strangely. She described how one time they had driven up to some place or other above Berkeley. He had left her sitting in the car and went off on some kind of solitary walk by himself one night, leaving her. (Laughs.)

There were many such stories about him. He was a rather different sort of person. He had already had some difficulties.

He was rather—how should I say it—an aesthete.

And in Britain, he had a rather difficult time: He tried joining an experimental group, and there was some sort of serious trouble. I can’t remember what the trouble was, but it was really quite serious. He left Britain and went to Germany. And there, he began working under Max Born and decided that he was a theorist, not an experimenter. He would never have been a decent experimenter, he was altogether too nervous. He never stopped smoking, he always had a cigarette in his mouth. He was a very nervous, tense man.

But he expressed himself quite beautifully. And the scientists really seemed to respect that. He never had any serious trouble with the scientists; no insurrection or disagreements.

Drollette: Was he soft-spoken?

Glauber: He was, yes.

And the remarkable thing, which you’ll catch in my own photos when I show them tomorrow, is that as a theorist, Oppie went around and visited all the experimental sites. He involved himself with the experimenters as much as possible—even though he never touched experiments and never went near the performance of experiments himself, after his bad experience in Britain.

Drollette: Is there something that makes theoretical physicists different from experimental physicists? They just seem to be a different group.

Glauber: Well, they are, they really are. First of all, many of them are physically clumsy.

You put them in the laboratory and the glassware starts breaking. (Laughter.)

Although that isn’t true of all of them, of course.

And I’ve got to say that when I was a kid, I myself thought that I was going to be an experimenter—and then mathematics moved me away. I felt later that that was a mistake, and that I should have become an experimenter. But it was too late.

Drollette: What did Oppie do that made Los Alamos so extraordinary?

Glauber: Well, he was extraordinary. He was a man of really considerable insight. The curious thing is how few things he actually did himself; there is next to nothing known by Oppenheimer’s name. But he understood it all and described it very well—and made quite a contribution that way.

Drollette: So he was a good manager, he understood the people he was dealing with?

Glauber: Well, you never would have thought that; he had had zero experience as a manager. And putting him in charge was the most imaginative thing that General Groves ever did.

He was rather an aloof person, and not easy to get to know.

But on the other hand, Oppie somehow created an atmosphere at Los Alamos that was unique, where everyone was working together on a mission. Consequently, even if you were a student, you could talk to a famous physicist.

All the physicists who were there were very accessible, and very involved. The only exception that comes to mind is Edward Teller.

Drollette: What was Teller’s role?

Glauber: Teller was one of the early theorists about chain reactions. And he had worked on why the stars shine—the thermonuclear reactions which go on in stars. He was known for that sort of thing.

But Teller was also a very impatient man, and very outspoken.

And I must say, when I got to Los Alamos, he was absent. There was an office next to mine which had the name “Teller” on the door, but there was no Edward Teller. He had determined in late 1943 that he had not been given the important positions that he wanted, and he had left in a huff. He left for something over a month, and then came back.

He was a big noise.

But Oppenheimer welcomed him back and gave him a division all his own, that would deal with what was called the “Super”—and the Super turned out to be the only passion that Teller truly had.

Drollette: What was the Super?

Glauber: That was the idea that one could use the fission reaction from the atomic bomb as a sort of match to ignite the kind of enormous continuous release of energy that occurs in a thermonuclear reaction—the kind that the stars burn. So, Teller’s notion was that you would use the fission bomb to ignite a thermonuclear reaction, which would release unlimited amounts of energy. And eventually, by 1954, that was what happened.

Drollette: So Teller was the man behind the H-bomb.

Glauber: Well, he tried hard to be the man behind the H-bomb. When the war was over and a great many people began leaving Los Alamos, Teller was the one person who would not leave. Teller felt his mission was still to start the thermonuclear reaction—and he had no success at it.

And that failure to discover how to ignite that reaction continued on through 1949, which was the point at which the Russians tested their first fission bomb.

So, immediately there was pressure on President Truman to get the Super project regenerated, in order for the United States to have the hydrogen bomb—an order of magnitude of destructive power above what we had been working on during the war.

And I must say that the hydrogen bomb has never done anybody any good. It does exist, and it is an enormous threat, but it has accomplished nothing in constructive terms.

Nothing for science.

Nothing for anybody.

Nothing for security.'

#Roy Glauber#Robert J. Oppenheimer#The Manhattan Project#Trinity test#Edward Teller#Los Alamos#Nobel Prize#Dorothy McKibbin#Richard Feynman#Robert F. Bacher#Sanskrit#General Groves

8 notes

·

View notes