#Sargon ii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is so exciting. I love the way technology can enhance what we know (or don't know) about archaeological sites. It's just wonderful

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

LA NUOVA PRIMAVERA DELL'ARCHEOLOGIA ASSIRA IN IRAQ

LA NUOVA PRIMAVERA DELL'ARCHEOLOGIA ASSIRA IN IRAQ Gli archeologi hanno sentore di un rinvenimento eccezionale solo quando sotto i loro strumenti, ad esempio, compaiono i resti di una scultura assira di 2.700 anni fa e se il manufatto sia stato rinvenuto, per l'ultima volta, decenni prima. Documentata la sua presenza già nel corso del XIX secolo e portata alla luce nei...

#Dur-Sharrukin#Impero neo-assiro#Iraq Museum#Lamassu#Michael Danti#Ninive#Pascal Butterlin#Sargon II#Sennacherib#Università della Pennsylvania#Università Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

0 notes

Text

Links & Quotes

Some links and quotes that caught my eye this week.

God’s blessings are not primarily for me, but they are through me for His glory. This is a short clip from an exclusive video I shared with my Patreon supporters. Become a supporter today! I have lots of new content every week, which you can check out on my YouTube channel. “What to do with a mistake: recognize it, admit it, learn from it, forget it.” —Dean Smith Until the mid-1800s, the…

View On WordPress

#apologetic#archeology#biblical history#courteous#example#God&039;s blessing#Gomorrah#historicity#Isaiah#leadership#lifelong learner#manners#mistake#poem#poetry#quotes#Sargon II#Sodom#video#world history

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lamassu, a kind of supernatural beings, lower than the gods with whom they share their nature and privilege. Good Lamassu

Lamaşşu, doğalarını ve ayrıcalıklarını paylaştıkları tanrılardan daha düşük bir tür doğaüstü varlıklar. İyi Lamaşşu.

1 note

·

View note

Text

knowing ive got another banger of an essay in the works...... you bitch!!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Lamassu#Assyrian deity#Iraq Museum#Baghdad#Iraq#Pascal Butterlin#sculpture#Khorsabad#King Sargon II#Victor Place#archaeologists#archaeology#alabaster sculpture#protective deity#deity

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Babylonian Kings: The armies of Babel and Lydia met. The Lydia King came to know his fate.

Assyrian Kings: I KILLED THE GREAT SOLDIERS OF THE REBEL KING! I THREW OPEN HIS CITY GATES AND PARTED THE BODIES OF HIS CHILDREN! HIS FLOCKS I SCATTERED IN GREAT HEAPS OF GORE! I TORE DOWN HIS GREAT HOUSE AND FILLED MY HANDS WITH GOLD, FIVE THOUSAND TREES OF OLIVES, 700 THOUSAND FLOCKS OF DONKIES, 900 THOUSAND FIELDS OF GRAIN! I SKINNED HIS WIVES FROM ANKLE TO NECK AND FILLED MY BELLY WITH HIS FINEST CALFS! I LIT ABALZE HIS GREAT TEMPLES AND FORNICATED WITH THE IDOLS OF HIS FALLEN GODS!!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bronze weight in the form of a lion, Neo-Assyrian, from the reign of Sargon II, 721 - 701 BC

from The Louvre

182 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Nimrud Ivories: Their Discovery & History

In 1845 CE, the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard began excavations at the ruins of the city of Nimrud in the region which is northern Iraq in the present day. Layard's expedition was part of a larger movement at the time to uncover ancient sites in Mesopotamia, which would corroborate stories found in the Bible, specifically in books in the Old Testament such as Genesis and Jonah. The archaeologists who excavated the sites throughout Mesopotamia in the mid-19th century CE were seeking physical evidence to support accounts of the Great Flood, the Tower of Babel, and cities such as Nineveh and Calah, among other biblical references. Their work, ironically, would have the complete opposite effect of what was intended: they discovered a civilization that existed long before the first biblical books were written, one which had, in fact, produced the first stories concerning a global flood and an ark, and which was far more advanced than had previously been thought. These discoveries would revolutionize human understanding of world history which, previously, had been heavily influenced by the Bible's version of events. Prior to these expeditions, little was known about Mesopotamian history outside of the Assyrians and Babylonians because they were the people best documented by the Greek historians and mentioned in the Bible. The great Mesopotamian cities of the past lay buried under the sands after the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, and their histories lay buried with them.

History of the City and Discovery of the Ivories

When Layard began his work at Nimrud, he did not even know which city he was excavating. He believed he had discovered Nineveh and, in fact, published his best-selling book on the excavation, Nineveh and its Remains, in 1849 CE, still confident in that belief. His book was so popular, and the artifacts he uncovered so intriguing, that further expeditions to the region were quickly funded. Further work in the region established that the ruins Layard had uncovered were not those of Nineveh but of another city, which was then referred to as Nimrud. The archaeologist William K. Loftus took over from Layard in 1854 CE and excavated Nimrud further discovering, among other treasures, the magnificent works of art known today as the Nimrud Ivories (also as the Loftus Ivories). Nimrud was an important city in ancient Mesopotamia known as Kalhu (also Caleh, Calah), which became the capital of the Assyrian Empire under Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 884-859 BCE), who moved the central government there from the traditional capital of Ashur.

The city existed as an important trade center from at least the 1st millennium BCE. It was located directly on a prosperous route just north of Ashur and south of Nineveh. The Assyrian Empire was ruled from Kalhu from 879-706 BCE, when Sargon II (reigned 722-705 BCE) moved the capital to his new city of Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad). Following the death of Sargon II, his son Sennacherib (reigned 705-681 BCE) abandoned Dur-Sharrukin and moved the capital to Nineveh. Kalhu continued to be an important city to the Assyrians, however, and the palaces and residences were richly adorned and ornamented with gold, silver, precious gems, and the intricate works of art that have come to be known as the Nimrud Ivories.

Continue reading...

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Assyrian Deity Statue Uncovered in Iraq

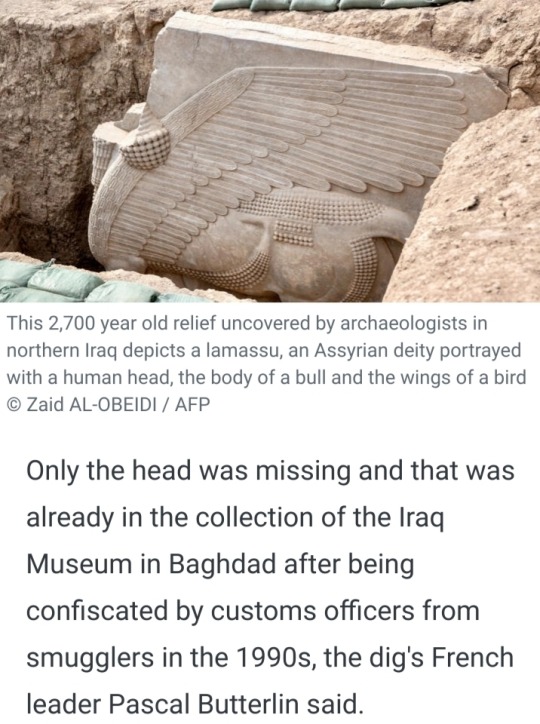

In a recent announcement from the The Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), archaeologists have successfully unearthed a remarkable ancient Assyrian deity statue known as a “lamassu” in Kursbad, Iraq.

A lamassu is a special Assyrian guardian deity, usually portrayed as a mix of human, bird, and either cow or lion features. These unique beings typically have a human-like head, a body resembling that of a bull or lion, and bird-like wings.

Guardian Lamassu sculptures in Assyria

In ancient Assyria, they often crafted pairs of lamassu sculptures and placed them at the entrances of palaces. These imposing figures faced both the streets and the inner courtyards.

What’s unique about these sculptures is that they were carved in high relief. When you look at them head-on, they seem still, but from the side, they appear to be in motion.

While we often see winged figures in the low-relief decorations inside rooms, lamassu were not commonly found as large figures in these spaces. However, they occasionally appeared in narrative reliefs. In these depictions, they seemed to take on the role of protectors for the Assyrians.

Ancient Assyrian deity statue in Iraq was discovered and then reburied

This discovery took place during their excavations at the 6th gate, situated in the western part of the ancient city of Khursbad.

Khursbad was originally built as a brand-new capital city by the Assyrian king Sargon II. He started this ambitious project shortly after he became king in 721 BC.

However, after Sargon II’s reign, his son and successor, Sennacherib, decided to shift the capital to Nineveh. This move left the construction of Khursbad unfinished, making it a fascinating historical puzzle.

As per the press release, the statue was originally discovered in 1992, when a team of Iraqi archaeologists stumbled upon the Assyrian deity statue. After the initial discovery of the lamassu, its head was unfortunately stolen in 1995. However, it was later recovered and is now safely preserved in the Iraqi Museum.

The main body of the Assyrian deity, was reburied to protect the statue and the surrounding architectural remains, a decision that likely saved it from destruction by ISIS, which systematically looted and destroyed the remains of Khursbad.

Collaboration between Iraqi and French archaeologists

In a remarkable collaborative effort between Iraqi and French archaeologists, Professor Dr. Ahmed Fakak Al-Badrani has spearheaded a mission that recently re-excavated the lamassu. This event marks the first time in thirty years that this ancient wonder has been unveiled to the world.

As stated by Dr. Layth Majid Hussein, the Chairman of the General Body for Archaeology and Heritage, the team is presently evaluating the condition of the lamassu to chart their forthcoming actions.

By Nisha Zahid.

#Ancient Assyrian Deity Statue Uncovered in Iraq#Kursbad Iraq#lamassu#sculpture#stone sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#assyrian history#assyrian empire#ancient art

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sargon, II Legion Standard Bearer

The banner took me around 3 hours to do, the only part on the banner that isn't freehand is the Cuneiform number 2 is a decal.

I'm quite happy with how it turned out. I didn't want to weather the banner because of how happy I am with it.

Only two more models left for the command squad now.

#warhammer#warhammer 40k#warhammer 40000#w40k#40k#warhammer 30k#warhammer 30000#horus heresy#legiones astartes#space marines#30k#ii legion#the pyre#lost legions#standard bearer#banner bearer

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giovanni Zatara and Zatanna Zatara

Coming from a long line of stage magicians who immigrated from Italy to America when his father, Luigi Zatara, was a child, Giovanni Zatara decided early to continue the family legacy. He was drafted into World War II as a young man but continued to practice stage magic when he could, often using it to entertain his comrades during rare moments of rest. While overseas, he met the Phantom Stranger, who told Giovanni he had the potential to use “real” magic, not just sleight-of-hand stage magic, and gave him a notebook written by Leonardo da Vinci, Giovanni’s ancestor. He tried to decipher the notebook but didn’t succeed until he got home and could actually focus on it, rather than using it to distract himself from the horrors of war. He spent the next decade learning all he could about real magic, falling in love with a natural magic user named Sindella, learning about the magic community though her, joining the Justice Society of America under the name “Merlin the Magician” along with his mentor Sargon the Sorcerer (John Sargent), and eventually fathering Zatanna with Sindella around 1950. Shortly after Zatanna’s birth, Sindella “died” in a car accident, leaving Giovanni to balance raising Zatanna as a single dad, being a superhero, and continuing his day job as a stage magician.

(I know he canonically never uses a superhero name, instead using his public stage name while being a superhero, but this bugs the ever loving CRAP out of me so I’m changing it. In my story, Giovanni didn’t want people to think he was “cheating” in his profession by using real magic on stage, or risk making non-magic people think they can do superhuman feats via stage magic illusions. He really wanted to keep the two separate.)

He may or may not have been cursed by the Evil Allura before he was found and saved by Zatanna and the Good Allura. Either way, this was all before the Justice League debuted, which he considered joining but ultimately decided he’s too old for this, retired from the JSA (and heroing in general), and opened a magic shop (stage magic, not real magic, though he does consult for real magic stuff on the side).

Born around 1950, around the same time Clark Kent was adopted, Zatanna Zatara was naturally gifted in magic and very passionate about learning everything to do with magic and the occult. Her father, Giovanni Zatara, kept his superhero identity a secret from her until her teens when she expressed interest in becoming a superhero. Zatanna had asked to learn more “practical” spells, like those a superhero might use, and the two danced around Giovanni’s superhero status and Zatanna’s budding desire to become a superhero before they ultimately came clean to each other, bringing them even closer as father and daughter. While he was proud of her choice, he could admit that the thought of his daughter being a superhero made him nervous. He was all too aware of how difficult and dangerous the life of a superhero was and didn't necessarily want that for his daughter, but more than that, if she was to become a superhero, he wanted it to be because she wanted to, not because she wanted his approval or felt obligated to follow in his footsteps or, heaven forbid, trying to impress a potential partner! Those were nice bonuses, sure, but he wanted to make sure the desire came from within Zatanna, not from an outside source.

Giovanni trained Zatanna for a few years and she was just starting to make a name for herself as “Zorina” when Giovanni went missing, prompting Zatanna to search for him and becoming a superhero in a trial-by-fire kind of way. He is eventually found and decides to take a step back from heroing, retiring from the JSA (slightly miffed that they didn’t help Zatanna more in finding him) and acting as Zatanna’s “sidekick”/background mentor as they work independently for a while, slowly falling back into a more consulting role rather than being out in the field himself. At some point, both of their identities had been revealed to the public but they decided to roll with it, incorporating real magic into their shows as a wow factor display and only keeping “superhero names” as a symbolic gesture to the superhero community.

By the time the Justice League debuts in 1994, Giovanni is in his 70s and really feeling his age, despite his magic keeping him young for longer than the average human. Zatanna, in her 40s, still feels like she’s in her prime and appears to be in her mid-20s; due to her mother’s magic lineage, Zatanna inherited “decelerated aging” and a long lifespan similar to Atlanteans. Zatanna happily joins the League as the Mistress of Magic and while Giovanni himself doesn't join, he agrees to consult in all matters magical and even help teach younger magic users to respect the craft. Zatanna looks maybe 30 by the time Danny is introduced to her, even though she’s in her 50s.

Sindella didn’t actually die, she was abducted by “her people”, who are a clan of magically inclined humans that call themselves “homo magi” rather than “homo sapiens”. They live in the mountains of Turkey and are similar to Atlanteans, though without their particular bias towards water-based abilities. They may also be mildly related to Themyscira, as the Amazon's language is described as a mix of classical Greek and Turkish.

I picked the name Merlin the Magician for Giovanni Zatara’s superhero name because there was a similar magic superhero by that name created shortly before Zatara debuted in DC Comics, and while this Merlin was originally made for Quality Comics, he does have ties to DC Comics and is apparently affiliated with the All-Star Squadron, which is very much a DC team. Both Merlin and Zatara were based on Mandrake the Magician, generally agreed to be the first comic book superhero as we would recognize them today, and (aside from a green cloak said to belong to King Arthur’s Merlin) both had the classic “stage magician” look with a tux/suit, mustache, and cape/capelet. Zatanna’s titles, Zorina and the Mistress of Magic, were much easier to pick, as she had apparently used them before according to the DC Wiki.

#non undertale#danny phantom#dpxdc#phandom#quick bio#phantom bat#Zatara#Zatanna#Giovanni Zatara#Zatanna Zatara#Merlin the Magician#Zorina#Mistress of Magic#magic#magician

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under Avandra's Eyes II: Exile's Path. Chapter VII: About Those Apologies

Neith poisons a garrison and does some social engineering to spare the slaves working there while Liza handles the captain of the city's troops. Beta-read by @canyouhearthelight and @writing-with-olive. Both of whom had some solid suggestions. Sorry about the week long hiatus - I was off getting married!

Neith

Her poisoners’ pouch was heavily laden that night. A foul thing to contemplate - she’d once been a witch doctor’s apprentice, and had gone back to learn more. She’d then learned from others, medical experts in Nistria, medicine men in Asgaria. To take life with the knowledge brought her no joy. To be a master of poisons, to take lives en masse with the arts of the pestle and mortar, the magic granted by the gifts the earth gave, felt almost blasphemous, and yet she’d now crossed that line a thousand times over, on every continent she knew.

And she had to simply live with it. She’d been forced into it by Vixen as a teenager, when the Blight had hit her village - when something so dangerous that not even her mentor could have fixed it had ravaged their home. She’d had to join cause with Vixen then, for a magical panacea that cured the blight. Since then, Vixen had forced her into all manner of quests - always trading one favor for another - never letting her get far enough ahead on her own, though Neith had always been able to get the distance she’d needed to continue her studies of medicine across the world. But Vixen had always found a way to drag her back, force her back into service, always found a way to make her violate some taboo that forced her away from wherever she had been in order to do the right thing.

And now she was preparing a slaughter at a ceremony. Yes, there were going to be daemons, and whatever gods the descendents of Ancient Sargomia held to were darker and fouler than any men should offer prayers to, but poisoning hundreds at a sacred rite still left a foul taste in her mouth. She forced it down. Liza had already dressing herself in a lovely number - strips of silk that wrapped up and around her body, tied below the shoulders, and left plenty of Liza’s supple, tanned skin showing, even as the elegant silk wrap around her shoulders marked her as a higher class.

In Neith’s pouch - lotus oil, a powerful hallucinogen, one that she would lace in all the wine for the rites to be engaged a week hence. Yew paste, to be smeared and mixed into any butter the soldiers had. Hemlock, to be left carelessly among their teas. The deaths would come in numbers, trickling, and weaken the garrison. She’d add other poisons as well - she’d seen normal mushrooms come in to be cooked into a stew, it would be trivial to slip in deathcap among them. To be sure, only a few caps in a hundred would be deadly - but among so many, certainly some would bite the wrong one.

Marcus had said these men drilled almost constantly and were never seen without their squads, and that was true enough, but this was all the better to her. Gaps in formations they were used to would unsettle them, always make them more uncertain if they were used to intimately knowing who they were fighting with and they had to suddenly reshuffle. To make matters worse, if she slipped poison among other foods the same way, it wouldn’t kill them all, only make them deeply, deeply paranoid about consuming anything. This, she knew, would be deadlier. Some would eat or drink as little as they could out of fear of death - better if she laced the water barrels with something to make men sick, but not kill them outright. Cause confusion. Terror. The soldiers of Sargonny would be weak and trembling by the time they faced off against the team - if they were still even alive.

So she and Liza strode to the soldier’s quarter. She saw, then, a youth of around fifteen years on the street, pushing a large broom. He looked to be Hykranian in origin, not Sargon - and if the racial features weren’t enough to confirm his status, his ragged smock, unshod feet, and haggard expression definitely were. She’d spoken to enough Hykranians to know that only those with Sargon blood worked stably in the city, everyone else would only find work there only as passing merchants or mercenaries. Anyone else working here wasn’t doing so of their own free will.

She approached the boy, even as Liza wove through the crowd ahead of her. Without particularly stopping, she slipped him a small clay pot. “The next time you or a friend is whipped,” she said, “Apply what’s here to the wounds. They won’t fester.” If she could not stop killing with her knowledge, she could make sure it was more than the only thing she did. She was a healer - and while that had been a small gesture, to someone who could easily be permanently crippled by a festering wound, it probably meant a great deal. Especially if the slaves in question would be free within weeks - which was very much their ambition. It may have been a mad one - but then, once, she’d have claimed that plundering an ancient tower in the middle of the Blasted Lands or finding a panacea for the Blight was a mad ambition, and she’d since then done both.

Besides, it wasn’t like a small pot of marigold ointment was hard to replace - the flower was common enough that getting a new pot she could seal to her satisfaction to carry would, in truth, be harder to replace than the ointment itself.

She hurried to follow Liza, passing the boy, and shuddering once she realized that the streets were almost eerily clean for a city often pelted by sandstorms so common to this part of the world. How often must people be worked to maintain it this way? Other places had built sewers, had built methods, carted waste out - but no cart could stand the sands of the desert, and this city was far too old to build under. Not that the Sargons need fear - as far as they were concerned, she knew, deaths of their ‘lessers’ in service were simply more advantage for their gods.

Liza was beckoning to her, and whispered, quietly. “Is there any way for us to make sure whoever they have in there isn’t…doesn’t catch it, from what you do?”

Neith shook her head. “If they start forcing slaves to check, innocent people will die. But it will kill Sargon men in droves. Or…” She chewed her lip. “You talked to Marcus about this? The kinds of people in military barracks?”

“Yeah. He said that with this kind of discipline he’d be surprised if they weren’t cleaning it themselves, or if they had a small cleaning staff do it while they were on drill. Aside from that, he said that he knew of no barracks in the world that didn’t have its share of prostitutes and laundry workers.”

“Did he mention if the laundry workers slept there? Them or their children? For that matter, Liza, you were a courtesan against your will, did you ever meet a man who’d buy your services if he was sick enough to be impotent?”

“Actually yes, but it was for a very elderly man who wanted my services as a singer while he took poison and died on terms he’d picked rather than letting his sickness claim him. For the general gist of your question - no. But some of the worst nights of my service were with noblemen about to ride to war, or with men just coming back from it. Men become much more brutal when they think they’re going to die - and I don’t envy any woman in those barracks with soldiers your poisons miss. None of which answered my question: what happens when they start simply forcing slaves to act as food tasters?”

Neith had to think about it - the bard knew more of this than she did. “I suspect once the panic sets in they’re more likely to draw food from other stores - most of these poisons take several days, they’ll think it's something else until it's too late. As to slaves - Liza, do you actually think they’re eating the same as the soldiers?”

Liza bit her lip. “I don’t know. I did, but I was a high class courtesan. Many of those bound in debt didn’t, those lower in status. I doubt a soldiers’ washer or a barracks prostitute is going to have the same status as a Palatine’s courtesan, but what happens when they do figure out it's the food? Other thing, many of lower status ate food from the day before, after it went stale, so unless whatever you’re using goes impotent if it isn’t eaten within a day…”

Neith swore. It had been a long time since she’d done this. “Fine then. There’s…other things I can do. Were servants permitted to make themselves tea from their lords’ stash?”

“No.”

“Hemlock stays in. I can get nightshade into wine, which again, will probably not be permitted to the slaves. Can you make sure we’re spilling it, or…”

Liza shook her head. “I’ll do one better. I’ll talk to the officers and flatter them until they come to the conclusion that wine is a luxury for their class and soldiers who’ve earned it - not slaves who should be grateful to have been taken alive.” She gave Neith a flat stare. “You want them to drink more of it, right?”

Neith nodded. “And…there’s things I can do to other rations to make them sick but not fatally, to confuse them, but not be fatal. I don’t think I can avoid that, but it also won’t kill anyone unintentionally targeted. The confusion these drugs cause is more fatal if you’re being attacked. And it takes time to set in.” She felt for slaves who would be undergoing the mind fog she was about to put everything in the barracks through - but by the time of the rite, the soldiers would be helpless, and the people she was drugging would be able to recover.

And she still had to get the really awful hallucinogens into the fancier wines for the ceremony itself.

Liza gripped her hand and pumped it. “They’ll survive. And trust me, it’ll be better for them to be obviously not part of it.”

“Right.” Neith sighed. “I’m glad you’re part of this. I…needed your expertise for this, and I wouldn’t exactly have wanted to bring…” Left unsaid was the rest of it. The only person who might know what conditions a servant or slave would face was Itene, and neither Liza as Itene’s ersatz-mother nor Neith as her (albeit temporary) bondswoman and companion wanted to bring Itene along for something like this. And besides, Itene couldn’t have gotten her in. This task was one for those with experience in just how brutal the world could be. Itene could keep her innocence a little longer, whatever was left of it. No need to have her mass poison people.

Neith passed her an ointment. “For your lips. Don’t swallow til you’ve wiped it off.”

Liza grinned.

The door to the barracks was blocked by a man in uniform, and Liza approached him, slinking into the light with the practiced ease of a professional courtesan. Neith watched her with cool professionalism, feeling the same pleasure she did watching anything done well, as the made-up Liza approached the soldier. “Lord Akkadius had a message for the commander on watch, and he sent it with a gift.”

Neith raised an eyebrow. Where had she gotten that name? The soldier seemed to buy it though, saying something too fast for Neith to follow. “I don’t have time for your attitude or doubts, boy. Let myself and my servant through at once. I have urgent business to discuss with your captain.”

Of course, the elegant cloak hadn’t been for fun. Nor had the makeup. In the torchlight, Liza looked like a Sargon woman, and Neith…oh, clever. The young man stammered something, and Liza got close to him, idly loosening her cloak. “I appreciate your sense of duty. I shouldn’t have been so impatient. But I have business to attend, and I need to be allowed through.” The young man’s face wasn’t fully visible behind the mask of his helm, but Neith noticed the eyeslit of his helmet very clearly tilted downward.

Then the door opened and Neith muttered, in her native tongue, “How much Khym did she just…”

“Enough to convince a gelded bull.” Liza whispered, in the same tongue. Then she spoke more loudly, in the Sargon tongue, more obviously for an audience. “Make yourself useful to the cooks here, girl. I’ll call for you when it’s time for us to leave.”

The room itself was full of soldiers, and from the condition of the handful of non-Sargon faces she saw, Neith was glad she and Liza had discussed the conditions of slaves who would be working here well ahead of time.

All at once, a cover story for her to be in the kitchens while the men focused on the more flashily dressed Liza as Neith looked down, cowed, and headed for the barracks kitchen. Only a slight moment later and she’d scattered hemlock among the soldiers’ tea leaves, knowing full well the chances of most of them getting a lethal dose were quite small, and when pressed to go grab a few cups of wine, quickly poured her nightshade into a few barrels. In likelihood it would only kill a few - but it would make many quite ill.

She brought a flagon up to the captain’s room, where Liza and the soldier’s captain spoke like old friends, Liza laughing at the man’s jokes with a grin that never quite touched her eyes. Neith handed her the flagon with a smirk and headed back down, spotting bread dough - and quickly dusted it with ergot.

She shrugged at the realization that she’d likely be here until Liza finished out whatever she was doing with the captain of the watch - and decided to look for other mischief or ways to make herself helpful. Leaving a bit of tansy in plain sight could be a start, at least for some of the women here.

The captain, she’d leave to Liza. They’d talk about it on the way back.

#original fiction#found family#my writing#writeblr#traumatized characters#writers on tumblr#under avandra's eyes#original fantasy#sword and sorcery#exile's path

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Standard of Sargon II, King of Assyria, 722-705 B.C." Ancient calendars and constellations. 1903. Cover detail.

Internet Archive

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Naqiʾa (c. 730– 668 BCE), wife of Sennacherib (705– 681), mother of the Neo- Assyrian king Esarhaddon (681– 669) and grandmother of Ashurbanipal (668– 627), is the best documented and in all probability most influential royal woman of the Neo- Assyrian period.

It was often suggested that Naqiʾa was the driving force behind Sennarcherib’s installment of Esarhaddon as crown prince. This was a truly exceptional case, as Esarhaddon was one of Sennacherib’s younger sons and most probably, even as a young man, suffered from an illness that would later kill him. Sickness was often interpreted as a sign of divine wrath in Mesopotamia; therefore, it was a severe obstacle for a claimant to the throne and any sickness of the king could be used to question his status as the darling of the gods. Maybe we will never know what the reasons for Esarhaddon’s promotion were, but we are sure about the results of Sennacherib’s decision.

Sennacherib was assassinated by his other sons and Esarhaddon had to fight his brothers in order to be enthroned. While the rebellion was going on, Naqiʾa explored the future of her son by asking for prophetic messages, something that was usually a privilege of the kings. The answer highlights the role of Ishtar, here called the Lady of Arbela, and the privileged position, of Naqiʾa:

I am the Lady of Arbela! To the king’s mother, since you implored me, saying: “The one on the right and the other on the left you have placed in your lap. My own offspring you expelled to roam the steppe!” No, king, fear not! Yours is the kingdom, yours is the power! By the mouth of Aḫat- abiša, a woman from Arbela.

Seemingly, the prophecy was right: it took Esarhaddon only two months to defeat his brothers and he was enthroned as Assyrian king. In this text Naqiʾa is already designated as queen mother; according to Melville this was “the highest rank a woman could achieve.”

In earlier research Naqiʾa was often seen as the strong woman behind a weak, sick, and superstitious king. Newer research has demonstrated that despite all of his problems, Esarhaddon was a capable ruler, who brought the Neo-Assyrian Empire to its maximal extension and pacified Babylonia, at least for a while.

During his reign Naqiʾa became really powerful and commissioned her own building inscription. To undertake large building projects and praise them in inscriptions is typical for kings, but extraordinary for a royal woman. The inscription introduces Naqiʾa in a bombastic tone, which is quite typical for inscriptions commissioned by kings:

I, Naqiʾa … wife of Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria, daughter- in- law of Sargon [II], king of the world, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of the world [and] king of Assyria; the gods Aššur, S.n, Šamaš, Nab., and Marduk, Ištar of Niniveh, [and] Ištar of Arbela … He [Essarhaddon] gave to me as my lordly share the inhabitants of conquered foes plundered by his bow. I made them carry hoe [and] basket and they made bricks. I … a cleared tract of land in the citadel of [the city of] Nineveh, behind the temple of the gods Sîn and Šamaš, for a royal residence of Esarhaddon, my beloved son …

We can clearly see that Naqiʾa held an extraordinarily powerful position during the reign of her son and this continued even after Esarhaddon’s death. She was eager to assure the enthronement of her grandson Assurbanipal. The loyalty treaty that was intended to secure his reign is called the treaty of Zakutu, another name of Naqiʾa. Its first lines read:

The treaty of Zakutu, the queen of Sannacherib, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, with Šamaš- šumu- ukin, his equal brother, with Šamaš- metu- uballiṭ and the rest of his brothers, with the royal seed, with the magnates and the governors, the bearded and the eunuchs, the royal entourage, with the exempts and all who enter the Palace, with Assyrians high and low: Anyone who (is included) in this treaty which Queen Zakutu has concluded with the whole nation concerning her favorite grandson Assurbanipal […]

That Naqiʾa was able to conclude a treaty with the most powerful persons throughout the empire and to establish her favorite grandson on the throne is clear evidence for her powerful position, even if she simply continued the plans she had made earlier with Esarhaddon. It seems that Naqiʾa died shortly after Assurbanipal was enthroned as king."

Fink Sebastian, “Invisible Mesopotamian royal women?”, in: The Routledge companion to women and monarchy in the ancient mediterranean world

#naqi'a#queens#ancient history#ancient world#history#women in history#mesopotamia#neo-assyrian empire#women's history#historical figures#8th century BC#7th century BC#assyria#middle-eastern history

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few points on inerrancy

Hello @joanofarcs-stigmata I finally had the time to gather my thoughts on this and do a small amount of research, hope you're well and this is still something you're up for dialoguing on :)

My position is that the bible is inerrant, which, colloquially, means it is always telling the truth. More precisely, my position is "The inerrancy of Scripture means that Scripture in the original manuscripts do not affirm anything that is contrary to fact"

Insert obvious caveats for vagueness (e.g. 8000 soldiers could be 7999) poetic/parabolic meaning, hyperbole and figures of speech, and "technically scientifically incorrect statements that are true in context e.g. 'the sun rises'", loose quotations, unusual grammar etc.

HOWEVER there is exactly one (1) genuine example of something in scripture that seems to be wrong that I know of! II Samuel 8 says 700 horsemen, I Chronicles 18 says 7000 horsemen, of the same battle. I'm not persuaded of any explanation except that this is a copying error. However, note that this still a) does not mean the original manuscript was wrong b) is very small.

So I'm open to very very small insignificant errors in our current versions of the bible. But that is the only one I know of (that I am persuaded is genuine).

Anyway so that's where I'm at, I have a couple points to say in defence of my position and my concerns with not taking an inerrant position which I would love to hear your thoughts on :)

1) The bible seems to claim to be true in a historical/scientific sense

Which comes through strongly in how new testament folks speak about the old testament events. For example, in Romans 4 Paul seems to really think that Abraham was 100 years old when Sarah had a child. Or in Matthew 12 Jesus seems to talk about the events of Jonah as real events.

I wonder how you would explain passages like these? Are they talking about them like I would quote a myth or talk about a fictional character, e.g. "Achilles slew Hector" "Batman fought the joker". If so, is that not somewhat misleading on Paul and Jesus' part, given his audience (from what I understand) would have taken these things literally?

Basically, if these things are not historically true, why do we have Jesus and the apostles treating them like they are?

2) It IS true

Which is of course a bold claim, but I think is true and helpful to point out here. Btw, would be happy to hear your pushback on any of my claims in this including the part where I claim there are no/minimal errors in scripture :)

Proving Scripture with history is dangerous because, of course, it can place human reason and the historical process above scripture in your epistemology. But in this context I think it's still useful to point out the historical support I think inerrancy enjoys.

Aside from my lack of knowledge of any notable historical errors in scripture, I'm aware of several positive cases where history was aligned with scripture, or scripture being the only extant source of information that is later confirmed in other sources. See the pool of Siloam, found in 2005. Nineveh, The Hittite Empire (!), Sargon of Akkad. Just some of the things found in the bible that were once thought mythical but later confirmed by archaeology.

And there seems to be consistently accurate ecology, distances between locations, period appropriate technology, names, cultural practices etc.

Anyway all this to say, I wonder whether there's any specific errors that prevent you from taking an inerrant view? And what you make of the positive evidence?

3) A few thoughts on authorship

So on authorship I understand you dispute most if not all traditional authorship? I wonder if you think it's a tenable view to say something like "even if the authors are not original, the content is still accurate"

We believe in God, and the inspiration of the scriptures, so is it a huge leap to go from "God inspired Moses to write the Torah completely accurately" to "God inspired a historian to write a collection of Moses' and other sources sayings to thus create the Torah completely accurately". Especially given in both cases, they are writing about events long in the past!

I'm not saying I agree with this btw (although I will concede Deuteronomy was not entirely written by Moses purely on the basis that it includes a description of his own death haha). I do tend to go with the traditional authorship. But I'm wondering whether "The scriptures we have were not written by the original authors" and "The scriptures are inerrant" are views that can co-exist.

4)

So in summary, the bible seems to claim to be historically true (when it speaks about historical events), seems, from what I know, to be incredibly accurate in such things, and I think even without holding to original authorship this is good reason to think inerrancy might be true.

And inerrancy is I think a very healthy position because it means you can trust scripture and apply it a lot more to your life. I think the biggest danger in our cultural context of taking a liberal view of scripture is that it allows you to consider 'errors' all those scriptures you don't like, thus making the scripture bend to your view rather than taking instruction from it. What do you see as the pros/cons of your position?

8 notes

·

View notes