#Spanish Ordinal Numbers

Text

Adjective Placement in Spanish Overview

With regards to adjective placement, I know I linked that bigger post I made about what the placement of adjectives generally mean but I'll give a very brief overview and if anyone has any specific questions please let me know.

IN GENERAL for like 70-ish percent of the time, adjectives go behind the noun in Spanish. These are your basic everyday adjectives that just describe nouns; el gato negro "the black cat", la mujer alta "the tall woman", los datos importantes "the important data", las tormentas peligrosas "the dangerous storms"

And again, IN GENERAL, if an adjective precedes the noun it is as if you bolded or italicized the adjective. It makes the adjective really stand out because of how out of the ordinary it is. It's very commonly used in poetry, writing, or for hyperbole:

La cruel realidad = The cruel reality

La fea verdad = The ugly truth

Mis sinceras disculpas = My sincere apologies

Mi más sentido pésame = My most heartfelt condolences/regrets

If you were looking at it more poetically you could think of "blue sky"... el cielo azul "the blue sky" is everyday Spanish, very typical. Saying el azul cielo "the blue sky" draws the eye to azul making it seem like "blue" is the most important or noteworthy thing about it

You typically see this kind of construction in everyday Spanish with expressions of gratitude, grief, horror, deep love, or any very strong emotions or when you're trying to make an impact

(More below)

-

Note: This will impact certain aspects of grammar, such as the nouns that are actually feminine but take a general masculine article such as el agua, el arma, el hada, el hambre, el águila etc.

As an example:

El hada madrina = Fairy Godmother

La buena hada = The good fairy

To further explain this rule - el hada is written with a masculine article. This is because it has its vocal stress on the first syllable and begins with A- or HA- [where H is silent]; and treating it as feminine would cause the sounds to run together, so the el adds a kind of phonetic break to preserve the sound; but in plural it will be las hadas "fairies/fey"

A word like this would still retain its normal functions as a feminine word, thus el agua bendita "holy water", el águila calva "bald eagle", el ave rapaz "bird of prey", and then in this case el hada madrina "fairy godmother"

By adding a separate word in front, you interrupt that la + A/HA construction and create a hiatus in the sounds already... so you can then treat it like a normal feminine noun, la buena hada "the good fairy"

You might also see this with grande "big" and its other form gran "great/large", el águila grande "the big eagle" vs. la gran águila "the great eagle"

-

Moving aside from the normal grammar, we now enter the exceptions. First - determiners.

There are a handful of adjectives that are known as determiners which come before the noun and they provide an important function in communicating things like number, possession, and location

The most common determiners include:

Definite articles [el, la, los, las]

Indefinite articles [un, una, unos, unas]

Possessives [mi, tu, su, nuestro/a, vuestro/a]

Demonstratives [este/esta, ese/esa/, aquel/aquella]

Interrogatives [qué, cuál/cuáles, cuánto/a]

(Also work as exclamatory determiners which just means ¡! instead of ¿?)

Cardinal numbers [uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco etc]

Ordinal numbers [primer/primera, segundo/a, tercer/tercera, cuarto/a, quinto/a, etc]

There are also a few determiners of quantity such as mucho/a "a lot/many/much", todo/a "all/every", cada "each", vario/a "various/many", poco/a "few/less", tal "such", tan "so much" / tanto/a "so many", algún/alguna and ningún/ninguna etc.

And it will generally apply to más and menos "more" and "less", and sometimes mejor/peor "better/worse"

-

Note: With possessives is that there are two forms depending on adjective placement:

mi amigo/a = my friend

mis amigos / amigas = my friends

un amigo mío = a friend of mine

una amiga mía = a friend of mine [f]

unos amigos míos = a few friends of mine

unas amigas mías = a few friends [f] of mine

All the pronouns have their own version of this possessive pattern

mi(s) and mío/a, tu(s) and tuyo/a, su(s) and suyo/a, and then nuestro/a and vuestro/a are the same but the adjective placement is different

As an example - nuestro país "our country" vs. el país nuestro "the country of ours", or nuestros familiares "our family members" vs. unos familiares nuestros "some family members of ours"

A common religious example - Nuestra Señora "Our Lady" and then el padrenuestro "the Our Father prayer"

The possessives that come after the noun are usually translated as "of mine/yours/his/hers/ours" etc.

You can also see a few determiners/adjectives in different places in a phrase like - un viejo amigo mío "an old friend of mine" vs. mi viejo amigo "my old friend"

-

As mentioned in the very beginning there are a handful of exceptions

Most notably:

viejo/a = old / elderly

antiguo/a = ancient, old / antique, old

mismo/a = same / self

gran = great, grand

grande = large

And includes propio/a "own / appropriate", as well as bueno/a "good" or malo/a "bad". I discussed a lot of these in more depth in the previous posts and in the one linked above

In many cases the exact meaning is different, even if it's slight - such as el hotel grande "the big hotel" vs. el Gran Hotel "the Grand Hotel"

bueno/a and malo/a are generally either "good" and "kind", or "bad" and "unkind", though the meanings can kind of blur together... as something like la buena hada "the good fairy" isn't so far off from el hada buena "the nice fairy"

When places before though bueno/a turns to buen + masculine, and malo/a turns to mal + masculine

As an example - un buen augurio "good omen", un mal presagio "a bad omen/portent"

.....but in feminine it looks like you'd expect: buena suerte "good luck" vs. mala suerte

Similarly, and one I didn't include the first time is cualquier/cualquiera

cualquier persona = any person

una persona cualquiera = an ordinary person

cualquier in front - regardless of gender - means "any", literally "whichever"

cualquiera in back comes out as "ordinary" or colloquially "any old" [such as un beso cualquiera "an ordinary kiss" / "any old kiss"], or in the case of people it could be like "a person of dubious/unknown background" sort of like "they could be anyone"...

-

And then you run into what I would consider "collocations" which is another word for a set noun or expression

There are some words/expressions that have the adjective in a specific place and you can't really change it or it sounds weird, so you sort of have to learn them as specific units to remember:

las bellas artes = fine arts [lit. "beautiful arts"]

(de) mala muerte = "backwater", "poor / middle of nowhere", a place of ill repute or somewhere very remote or inconsequential [lit. "of a bad death"]

a corto plazo = short-term

a largo plazo = long-term

(en) alta mar = (on) the high seas

alta calidad = high quality

baja calidad = low quality

Blancanieves = Snow White (the character/fairlytale)

la mala hierba, las malas hierbas = weeds [lit. "bad grasses"; plants that grow without you wanting them to or that grow in bad places etc]

los bajos fondos = criminal underworld [lit. "the low depths"]

el más allá = "the great beyond", "the afterlife" [lit. "the more over there/beyond"]

buen/mal augurio = good/bad omen

buen/mal presagio = good/bad omen

buena/mala suerte = good/bad luck

...Also includes all the greetings like buen día / buenos días or buenas noches etc. they're all considered set phrases

There are also many collocations that use adjectives in their normal place that also can't be separated such as los frutos secos "nuts", or el vino tinto/banco "red/white wine" etc.

A collocation just means that they are treating multiple words as set phrases or a singular unit

And again, some history/geographical terms will have these as well:

la Gran Muralla China = Great Wall of China

la Primera Guerra Mundial = First World War

la Segunda Guerra Mundial = Second World War

el Sacro Imperio Romano = Holy Roman Empire

la Antigua Grecia = Ancient Greece

el Antiguo Egipto = Ancient Egypt

(el) Alto Egipto = Upper Egypt

(el) Bajo Egipto = Lower Egypt

Nueva York = New York

Nueva Zelanda = New Zealand

Nuevo México = New Mexico

Nueva Escocia = Nova Scotia [lit. "New Scotland"]

la Gran Manzana = the Big Apple [aka "New York"]

Buenos Aires

There are many such terms

#spanish#langblr#spanish language#learning spanish#spanish grammar#learn spanish#long post#spanish vocabulary#vocabulario

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

Can rare/endangered languages lack new vocabulary? As in, as society has new technology and invents new words and slang, only the more wider used languages have those new words. The less used languages have moved toward home langauge only rather than at schools or in the wider community and certainly not international so they completely lack in such vocabulary because it's never progressed that far. Does that make sense?

Tex: Short answer: No.

Longer answer: New words are always added to a language every generation, which is how a language survives. When this happens, in combination with fewer native speakers, a language may either die off in isolation or become assimilated into a more popular language. It’s crucial that any new words are not simply taken from another language, because that’s how a language is often stifled and subsumed.

To take an example of well-known languages, English is often mined for new words, particularly for technology. In French, the word for computer is not some adaptation of “computer”, but rather the word is ordinateur (Larousse), which comes from the Latin ordinator (Larousse). Now, Latin used to be a lingua franca throughout most of Europe, and because of that there are a lot of words carried over without the extinction of the languages that adopted new words (more or less). English is now a lingua franca, to the same degree of exposure and adoption.

Utuabzu: As Tex said, short answer, no. One of the basic characteristics of natural languages is that they are infinite, that is to say that every natural language is capable of conveying any concept or idea. If a community does not need to discuss something often, their language might need to use a rather roundabout way to do so, but it can be done. If a concept does need to be discussed frequently, then the community will either create a word for it or borrow one from another language. If a concept no longer needs to be discussed frequently, then the word might be repurposed to mean something related or be dropped altogether. This happens all the time, constantly, in every living language. Smaller, more isolated communities tend to experience this more slowly than larger, more interconnected communities, simply because new concepts are introduced to the former more slowly and rarely than to the latter.

English spent the 16th-20th centuries borrowing and coining a huge number of words related to geography, plants and animals, foods and products, because the expansion of the British Empire (and the US), the development of global trade and the industrial revolution brought English speakers into contact with a vast array of new concepts that had never previously needed to be discussed in English. England, being cold and damp, didn’t really require words like ‘jungle’ (borrowed from Hindi) or ‘canyon’ (borrowed from Spanish), nor did a late medieval English speaker need to talk about a ‘bicycle’ or ‘smog’.

The same processes happen in every language, no matter how much some people (Académie Française) try to stop them. Language is ultimately a tool used by a community, and the community will alter it to suit its needs.

The phenomenon you’re describing where different languages are used in different areas of life (called domains*) is called polyglossia (or in older works/works dealing with only two languages/dialects, diglossia), and it’s pretty common. Outside of monolingual speakers of standard national languages (Anglophones tend to be the worst for this) most people in the world experience some degree of polyglossia - usually using their local language or dialect with family/friends and in casual social settings and the standard national language in formal settings - though the degree does vary.

Some polyglossic environments have up to 5 distinct languages in use by any given individual - the example I recall from my sociolinguistics textbook being a sixteen year old named Kalala, from Bukavu in eastern Congo(Democratic Republic of), who spoke an informal variety of Shi at home and with family, and with market vendors of his ethnic group, a formal variety of Shi at weddings and funerals, a kiSwahili dialect called Kingwana with people from other ethnic groups in informal situations, Standard Congolese kiSwahili in formal and workplace situations and with figures of authority, and a youth-coded dialect that draws on languages like French and English called Indoubil with his friends.**

*Important to note here that a domain is both a physical space, eg. the Home, School, Courtroom, and a conceptual space, eg. Family, Work, Business, Politics, Religion. There’s often overlap between these, but polyglossic communities do tend to arrive at a rough unspoken consensus on what language goes with what domain. Most community members would just say that using the wrong language for a domain would feel weird.

**note that this example is pretty old. So old that it still calls the country Zaire. The reference is in Holmes, J., 1992, An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, pp 21-22.

Blue: The USSR presents an interesting case study when it comes to rare languages. It started with Lenin and policies aimed to develop regional languages, down to creating whole writing systems for those that did not have one. Russian was de facto lingua franca and functioned as an official language, but de jure, it was not. The goal of this policy wasn’t just to support literacy and education for different ethnicities; it created, via translations, a common cultural background and was aimed to spread Marxist ideology. If you want people to understand you and accept you, you need to speak their own language.

After these policies shifted, the regional languages didn’t die; they’re still taught in schools and are in use. And one of the important aspects of a language being in use – it grows and develops: as our reality changes, languages have to adapt to it, otherwise they die. And even if there is a “hegemonic” lingua franca that is more used across the board, the government might still be motivated to develop endangered languages, to facilitate the blending of the cultures and to solidify new ideas.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

[D]omesticated attack dogs [...] hunted those who defied the profitable Caribbean sugar regimes and North America’s later Cotton Kingdom, [...] enforced plantation regimens [...], and closed off fugitive landscapes with acute adaptability to the varied [...] terrains of sugar, cotton, coffee or tobacco plantations that they patrolled. [...] [I]n the Age of Revolutions the Cuban bloodhound spread across imperial boundaries to protect white power and suppress black ambitions in Haiti and Jamaica. [...] [Then] dog violence in the Caribbean spurred planters in the American South to import and breed slave dogs [...].

---

Spanish landowners often used dogs to execute indigenous labourers simply for disobedience. [...] Bartolomé de las Casas [...] documented attacks against Taino populations, telling of Spaniards who ‘hunted them with their hounds [...]. These dogs shed much human blood’. Many later abolitionists made comparisons with these brutal [Spanish] precedents to criticize canine violence against slaves on these same Caribbean islands. [...] Spanish officials in Santo Domingo were licensing packs of dogs to comb the forests for [...] fugitives [...]. Dogs in Panama, for instance, tracked, attacked, captured and publicly executed maroons. [...] In the 1650s [...] [o]ne [English] observer noted, ‘There is nothing in [Barbados] so useful as … Liam Hounds, to find out these Thieves’. The term ‘liam’ likely came from the French limier, meaning ‘bloodhound’. [...] In 1659 English planters in Jamaica ‘procured some blood-hounds, and hunted these blacks like wild-beasts’ [...]. By the mid eighteenth century, French planters in Martinique were also relying upon dogs to hunt fugitive slaves. [...] In French Saint-Domingue [Haiti] dogs were used against the maroon Macandal [...] and he was burned alive in 1758. [...]

Although slave hounds existed throughout the Caribbean, it was common knowledge that Cuba bred and trained the best attack dogs, and when insurrections began to challenge plantocratic interests across the Americas, two rival empires, Britain and France, begged Spain to sell these notorious Cuban bloodhounds to suppress black ambitions and protect shared white power. [...] [I]n the 1790s and early 1800s [...] [i]n the Age of Revolutions a new canine breed gained widespread popularity in suppressing black populations across the Caribbean and eventually North America. Slave hounds were usually descended from more typical mastiffs or bloodhounds [...].

---

Spanish and Cuban slave hunters not only bred the Cuban bloodhound, but were midwives to an era of international anti-black co-ordination as the breed’s reputation spread rapidly among enslavers during the seven decades between the beginning of the Haitian Revolution in 1791 and the conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865. [...]

Despite the legends of Spanish cruelty, British officials bought Cuban bloodhounds when unrest erupted in Jamaica in 1795 after learning that Spanish officials in Cuba had recently sent dogs to hunt runaways and the indigenous Miskitos in Central America. [...] The island’s governor, Balcarres, later wrote that ‘Soon after the maroon rebellion broke out’ he had sent representatives ‘to Cuba in order to procure a number of large dogs of the bloodhound breed which are used to hunt down runaway negroes’ [...]. In 1803, during the final independence struggle of the Haitian Revolution, Cuban breeders again sold hundreds of hounds to the French to aid their fight against the black revolutionaries. [...] In 1819 Henri Christophe, a later leader of Haiti, told Tsar Alexander that hounds were a hallmark of French cruelty. [...]

---

The most extensively documented deployment of slave hounds [...] occurred in the antebellum American South and built upon Caribbean foundations. [...] The use of dogs increased during that decade [1830s], especially with the Second Seminole War in Florida (1835–42). The first recorded sale of Cuban dogs into the United States came with this conflict, when the US military apparently purchased three such dogs for $151.72 each [...]. [F]ierce bloodhounds reputed to be from Cuba appeared in the Mississippi valley as early as 1841 [...].

The importation of these dogs changed the business of slave catching in the region, as their deployment and reputation grew rapidly throughout the 1840s and, as in Cuba, specialized dog handlers became professionalized. Newspapers advertised slave hunters who claimed to possess the ‘Finest dogs for catching negroes’ [...]. [S]lave hunting intensified [from the 1840s until the Civil War] [...]. Indeed, tactics in the American South closely mirrored those of their Cuban predecessors as local slave catchers became suppliers of biopower indispensable to slavery’s profitability. [...] [P]rice [...] was left largely to the discretion of slave hunters, who, ‘Charging by the day and mile [...] could earn what was for them a sizeable amount - ten to fifty dollars [...]'. William Craft added that the ‘business’ of slave catching was ‘openly carried on, assisted by advertisements’. [...] The Louisiana slave owner [B.B.] portrayed his own pursuits as if he were hunting wild game [...]. The relationship between trackers and slaves became intricately systematized [...]. The short-lived republic of Texas (1836–46) even enacted specific compensation and laws for slave trackers, provisions that persisted after annexation by the United States.

---

All text above by: Tyler D. Parry and Charlton W. Yingling. "Slave Hounds and Abolition in the Americas". Past & Present, Volume 246, Issue 1, February 2020, pages 69-108. Published February 2020. At: doi dot org/10.1093/pastj/gtz020. February 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#its first of february#while already extensive doumentation of dogs in american south in 1840s to 60s#a nice aspect of this article is focuses on two things#one being significance of shared crossborder collaboartion cooperation of the major empires and states#as in imperial divisions set aside by spain britain france and us and extent to which they#collectively helped each other crush black resistance#and then two the authors also focus on agency and significance of black resistance#not really reflected in these excerpts but article goes in depth on black collaboration#in newspapers and fugitive assistance and public discourse in mexico haiti us canada#good references to transcripts and articles at the time where exslaves and abolitionists#used the brutality of dog attacks to turn public perception in their favor#another thing is article includes direct quotes from government and colonial officials casually ordering attacks#which emphasizes clearly that they knew exactly what they were doing#ecology#indigenous#multispecies#borders#imperial#colonial#tidalectics#caribbean#carceral geography#archipelagic thinking

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Thus many collectives did not compete with each other for profits, as surpluses were pooled and distributed on a wider basis than the individual collective.

This process went on in many different unions and collectives and, unsurprisingly, the forms of co-ordination agreed to lead to different forms of organisation in different areas and industries, as would be expected in a free society. However, the two most important forms can be termed syndicalisation and confederationalism (we will ignore the forms created by the collectivisation decree as these were not created by the workers themselves).

Syndicalisation (our term) meant that the CNT’s industrial union ran the whole industry. This solution was tried by the woodworkers’ union after extensive debate. One section of the union, “dominated by the FAI, maintained that anarchist self-management meant that the workers should set up and operate autonomous centres of production so as to avoid the threat of bureaucratisation.” However, those in favour of syndicalisation won the day and production was organised in the hands of the union, with administration posts and delegate meetings elected by the rank and file. However, the “major failure … (and which supported the original anarchist objection) was that the union became like a large firm” and its “structure grew increasingly rigid.” [Ronald Fraser, Blood of Spain, p. 222] According to one militant, “From the outside it began to look like an American or German trust” and the workers found it difficult to secure any changes and “felt they weren’t particularly involved in decision making.” [quoted by Fraser, Op. Cit., p. 222 and p. 223] However, this did not stop workers re-electing almost all posts at the first Annual General Assembly.

In the end, the major difference between the union-run industry and a capitalist firm organisationally appeared to be that workers could vote for (and recall) the industry management at relatively regular General Assembly meetings. While a vast improvement on capitalism, it is hardly the best example of participatory self-management in action.

(...)

The other important form of co-operation was what we will term confederalisation. This system was based on horizontal links between workplaces (via the CNT union) and allowed a maximum of self-management and mutual aid. This form of co-operation was practised by the Badalona textile industry (and had been defeated in the woodworkers’ union). It was based upon each workplace being run by its elected management, selling its own production, getting its own orders and receiving the proceeds. However, “everything each mill did was reported to the union which charted progress and kept statistics. If the union felt that a particular factory was not acting in the best interests of the collectivised industry as a whole, the enterprise was informed and asked to change course.”

This system ensured that the “dangers of the big ‘union trust’ as of the atomised collective were avoided.” [Fraser, Op. Cit., p. 229] According to one militant, the union “acted more as a socialist control of collectivised industry than as a direct hierarchised executive.” The federation of collectives created “the first social security system in Spain” (which included retirement pay, free medicines, sick and maternity pay) and a compensation fund was organised “to permit the economically weaker collectives to pay their workers, the amount each collective contributed being in direct proportion to the number of workers employed.” [quoted by Fraser, Op. Cit., p. 229]

As can be seen, the industrial collectives co-ordinated their activity in many ways, with varying degrees of success."

I.8.4 How were the Spanish industrial collectives co-ordinated?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I.8.10 Why did the CNT collaborate with the state?

As is well know, in September 1936 the CNT joined the Catalan government, followed by the central government in November. This flowed from the decision made on July 21st to not speak of Libertarian Communism until after Franco had been defeated. In other words, to collaborate with other anti-fascist parties and unions in a common front against fascism. This decision, initially, involved the CNT agreeing to join a “Central Committee of Anti-Fascist Militias” proposed by the leader of the Catalan government, Louis Companys. This committee was made up of representatives of various anti-fascist parties and groups. From this it was only a matter of time until the CNT joined an official government as no other means of co-ordinating activities existed (see section I.8.13).

The question must arise, why did the CNT decide to collaborate with the state, forsake its principles and, in its own way, contribute to the counter-revolution and the loosing of the war. This is an important question. Indeed, it is one Marxists always throw up in arguments with anarchists or in anti-anarchist diatribes. Does the failure of the CNT to implement anarchism after July 19th mean that anarchist politics are flawed? Or, rather, does the experience of the CNT and FAI during the Spanish revolution indicate a failure of anarchists rather than of anarchism, a mistake made under difficult objective circumstances and one which anarchists have learnt from? Needless to say, anarchists argue that the latter is correct. In other words, as Vernon Richards argued, “the basis of [this] criticism is not that anarchist ideas were proved to be unworkable by the Spanish experience, but that the Spanish anarchists and syndicalists failed to put their theories to the test, adopting instead the tactics of the enemy.” [Lessons of the Spanish Revolution, p. 14]

So, why did the CNT collaborate with the state during the Spanish Civil War? Simply put, rather than being the fault of anarchist theory (as Marxists like to claim), its roots can be discovered in the situation facing the Catalan anarchists on July 20th. The objective conditions facing the leading militants of the CNT and FAI influenced the decisions they took, decisions which they later justified by mis-using anarchist theory.

What was the situation facing the Catalan anarchists on July 20th? Simply put, it was an unknown situation, as the report made by the CNT to the International Workers Association made clear:

“Levante was defenceless and uncertain … We were in a minority in Madrid. The situation in Andalusia was unknown … There was no information from the North, and we assumed the rest of Spain was in the hands of the fascists. The enemy was in Aragón, at the gates of Catalonia. The nervousness of foreign consular officials led to the presence of a great number of war ships around our ports.” [quoted by Jose Peirats, Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution, p. 180]

Anarchist historian Jose Peirats noted that according to the report “the CNT was in absolute control of Catalonia in July 19, 1936, but its strength was less in Levante and still less in central Spain where the central government and the traditional parties were dominant. In the north of Spain the situation was confused. The CNT could have mounted an insurrection on its own ‘with probable success’ but such a take-over would have led to a struggle on three fronts: against the fascists, the government and foreign capitalism. In view of the difficulty of such an undertaking, collaboration with other antifascist groups was the only alternative.” [Op. Cit., p. 179] In the words of the CNT report itself:

“The CNT showed a conscientious scrupulousness in the face of a difficult alternative: to destroy completely the State in Catalonia, to declare war against the Rebels [i.e. the fascists], the government, foreign capitalism, and thus assuming complete control of Catalan society; or collaborating in the responsibilities of government with the other antifascist fractions.” [quoted by Robert Alexander, The Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War, vol. 2, p. 1156]

Moreover, as Gaston Leval later argued, given that the “general preoccupation” of the majority of the population was “to defeat the fascists … the anarchists would, if they came out against the state, provoke the antagonism … of the majority of the people, who would accuse them of collaborating with Franco.” Implementing an anarchist revolution would, in all likelihood, also result in “the instant closing of the frontier and the blockade by sea by both fascists and the democratic countries. The supply of arms would be completely cut off, and the anarchists would rightly be held responsible for the disastrous consequences.” [The Anarchist Collectives, p. 52 and p. 53]

While the supporters of Lenin and Trotsky will constantly point out the objective circumstances in which their heroes made their decisions during the Russian Revolution, they rarely mention those facing the anarchists in Spain on the 20th of July, 1936. It seems hypocritical to point to the Russian Civil War as the explanation of all of the Bolsheviks’ crimes against the working class (indeed, humanity) while remaining silent on the forces facing the CNT-FAI at the start of the Spanish Civil War. The fact that if the CNT had decided to implement libertarian communism in Catalonia they would have to face the fascists (commanding the bulk of the Spanish army), the Republican government (commanding the rest) plus those sections in Catalonia which supported the republic is rarely mentioned. Moreover, when the decision to collaborate was made it was immediately after the defeat of the army uprising in Barcelona — the situation in the rest of the country was uncertain and when the social revolution was in its early days. Stuart Christie indicates the dilemma facing the leadership of the CNT at the time:

“The higher committees of the CNT-FAI-FIJL in Catalonia saw themselves caught on the horns of a dilemma: social revolution, fascism or bourgeois democracy. Either they committed themselves to the solutions offered by social revolution, regardless of the difficulties involved in fighting both fascism and international capitalism, or, through fear of fascism (or of the people), they sacrificed their anarchist principles and revolutionary objectives to bolster, to become, part of the bourgeois state … Faced with an imperfect state of affairs and preferring defeat to a possibly Pyrrhic victory, the Catalan anarchist leadership renounced anarchism in the name of expediency and removed the social transformation of Spain from their agenda.

“But what the CNT-FAI leaders failed to grasp was that the decision whether or not to implement Libertarian Communism, was not theirs to make. Anarchism was not something which could be transformed from theory into practice by organisational decree … [the] spontaneous defensive movement of 19 July had developed a political direct of its own.” [We, the Anarchists!, p. 99]

Given that the pro-fascist army still controlled a third or more of Spain (including Aragón) and that the CNT was not the dominant force in the centre and north of Spain, it was decided that a war on three fronts would only aid Franco. Moreover, it was a distinct possibility that by introducing libertarian communism in Catalonia, Aragón and elsewhere, the workers’ militias and self-managed industries would have been starved of weapons, resources and credit. That isolation was a real problem can be seen from Abad de Santillán’s later comments on why the CNT joined the government:

“The Militias Committee guaranteed the supremacy of the people in arms … but we were told and it was repeated to us endlessly that as long as we persisted in retaining it, that is, as long as we persisted in propping up the power of the people, weapons would not come to Catalonia, nor would we be granted the foreign currency to obtain them from abroad, nor would we be supplied with the raw materials for our industry. And since losing the war meant losing everything and returning to a state like that prevailed in the Spain of Ferdinand VII, and in the conviction that the drive given by us and our people could not vanish completely from the new economic life, we quit the Militias Committee to join the Generalidad government.” [quoted by Christie, Op. Cit., p. 109]

It was decided to collaborate and reject the basic ideas of anarchism until the war was over. A terrible mistake, but one which can be understood given the circumstances in which it was made. This is not, we stress, to justify the decision but rather to explain it and place it in context. Ultimately, the experience of the Civil War saw a blockade of Republic by both “democratic” and fascist governments, the starving of the militias and self-managed collectives of resources and credit as well as a war on two fronts when the State felt strong enough to try and crush the CNT and the semi-revolution its members had started. Most CNT members did not think that when faced with the danger of fascism, the liberals, the right-wing socialists and communists would prefer to undermine the anti-fascist struggle by attacking the CNT. They were wrong and, in this, history proved Durruti totally correct:

“For us it is a matter of crushing Fascism once and for all. Yes, and in spite of the Government.

“No government in the world fights Fascism to the death. When the bourgeoisie sees power slipping from its grasp, it has recourse to Fascism to maintain itself. The liberal government of Spain could have rendered the fascist elements powerless long ago. Instead it compromised and dallied. Even now at this moment, there are men in this Government who want to go easy on the rebels. You can never tell, you know — he laughed — the present Government might yet need these rebellious forces to crush the workers’ movement …

“We know what we want. To us it means nothing that there is a Soviet Union somewhere in the world, for the sake of whose peace and tranquillity the workers of Germany and China were sacrificed to Fascist barbarians by Stalin. We want revolution here in Spain, right now, not maybe after the next European war. We are giving Hitler and Mussolini far more worry to-day with our revolution than the whole Red Army of Russia. We are setting an example to the German and Italian working class on how to deal with fascism.

“I do not expect any help for a libertarian revolution from any Government in the world. Maybe the conflicting interests of the various imperialisms might have some influence in our struggle. That is quite possible … But we expect no help, not even from our own Government, in the last analysis.”

“You will be sitting on a pile of ruins if you are victorious,” said [the journalist] van Paasen.

Durruti answered: “We have always lived in slums and holes in the wall. We will know how to accommodate ourselves for a time. For, you must not forget, we can also build. It is we the workers who built these palaces and cities here in Spain and in America and everywhere. We, the workers, can build others to take their place. And better ones! We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth; there is not the slightest doubt about that. The bourgeoisie might blast and ruin its own world before it leaves the stage of history. We carry a new world here, in our hearts. That world is growing this minute.” [quoted by Vernon Richards, Lessons of the Spanish Revolution, pp. 193-4f]

This desire to push the revolution further was not limited to Durruti, as can be seen from this communication from the Catalan CNT leadership in August 1936. It also expresses the fears driving the decisions which had been made:

“Reports have also been received from other regions. There has been some talk about the impatience of some comrades who wish to go further than crushing fascism, but for the moment the situation in Spain as a whole is extremely delicate. In revolutionary terms, Catalonia is an oasis within Spain.

“Obviously no one can foresee the changes which may follow the civil war and the conquest of that part of Spain which is still under the control of mutinous reactionaries.” [quoted by Jose Peirats, Op. Cit., pp. 151–2]

Isolation, the uneven support for a libertarian revolution across Spain and the dangers of fascism were real problems, but they do not excuse the libertarian movement for its mistakes. The biggest of these mistakes was forgetting basic anarchist ideas and an anarchist approach to the problems facing the Spanish people. If these ideas had been applied in Spain, the outcome of the Civil War and Revolution could have been different.

In summary, while the decision to collaborate is one that can be understood (due to the circumstances under which it was made), it cannot be justified in terms of anarchist theory. Indeed, as we argue in the next section, attempts by the CNT leadership to justify the decision in terms of anarchist principles are not convincing and cannot be done without making a mockery of anarchism.

#anarchist society#practical#practical anarchism#practical anarchy#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

You thought Ikea was bad

I would like to extend a profound and professional "Fuck you" to Ridgid tools, for their aggressively bad assembly instructions. They can't even manage ordinal page numbers - it goes unnumbered, 2-English - 11-English, 2-French - 11-French, 2-Spanish - 11-Spanish, and then the diagrams on 12-19. Which means, no, there is no explanation as to which part is which AND you are constantly flipping through the manual.

I am, as a technical writer, very offended. This is absolutely terrible.

(In all seriousness, Ikea manuals are actually Pretty Damned Good. You don’t need to be literate, they’re not limited to any particular language, they show all the parts beforehand - clearly enough that you can distinguish them - and the instructions are in clear order without being broken up by extraneous warnings.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saut Hermès: 14th Edition Welcomes the Elite of Showjumping &, their Flying Beasts to the Grand Palais!

<img decoding="async" width="1000" height="666" data-attachment-id="170710" data-permalink="https://jumpernews.com/2024/03/14/saut-hermes-14th-edition-welcomes-the-elite-of-showjumping-their-flying-beasts-to-the-grand-palais/hermes-2023-35/" data-orig-file="https://i0.wp.com/jumpernews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview.jpg?fit=1000%2C666&ssl=1" data-orig-size="1000,666" data-comments-opened="0" data-image-meta=""aperture":"3.5","credit":"@Ctanierephotographie pour Herm","camera":"ILCE-1","caption":"Hermes 2023 -","created_timestamp":"1647677127","copyright":"Christophe Taniu00e8re pour Hermu00e8s","focal_length":"200","iso":"3200","shutter_speed":"0.001","title":"Hermes 2023 -","orientation":"1"" data-image-title="Hermes 2023 –" data-image-description data-image-caption="

Hermes 2023 –

” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/jumpernews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview.jpg?fit=300%2C200&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/jumpernews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview.jpg?fit=1000%2C666&ssl=1″ src=”https://i0.wp.com/jumpernews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview.jpg?resize=1000%2C666&ssl=1″ alt class=”wp-image-170710″ srcset=”https://eqsportsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview-1.jpg 1000w, https://eqsportsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview-2.jpg 300w, https://eqsportsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview-3.jpg 150w, https://eqsportsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024.03.14.99.99-Saut-Hermes-CSI-5-Preview-4.jpg 768w” sizes=”(max-width: 1000px) 100vw, 1000px” data-recalc-dims=”1″>

Paris, France – March 14, 2024 – , On March 15, 16 and 17, the Hermès house did welcome sixty of the world’s best users and their horses to the Grand Palais Éphémère for three days of opposition labeled 5*, the highest level of international events. Twenty-five global çandidates under the age of 25 may also take part in the Hermès ability tests. A few days before ƫheir entry onto the trail, we take a look at the people competing in the Saut Hermès at thȩ Grand Palais Éphémère, 2024 model.

The lineup for this thirtȩenth edition of the Saut Hermès at the Grand Palais, which was co-ordinated by GL Occasions, promises intense spσrts and tension. Both Hermès partner riders Ben Maher ( GBR ) and Steve Guerdat ( SUI), who have been the world number one for more than a year, have confirmed their presence. The top three riders in the world will face serious competition, including Hermès partner riders Simon Delestre and Julien Épaillard ( 4th ) and Simon Épaillard (7th ), two of whom are also French riders. Max Khüner ( AUT), who is currently eįghth in the world rankings, adds to the group of six top tȩn alumni on the Parisian track. Numerous other champions reacted to the sports concern that the Spanish program manager Santiago Varela Ullastres had suggested. In fact, there will be no fewer than 20 countries competing in this one.

Marlón Módolo Zanotelli ( BRA ), the team bronze medalist from the last year’s Pan American Games, and Santiago Lambre ( BRA ), the recent 5* Grand Prix winner in Doha ( Qatar ), will be able to count on Brazil. The Belgian Pieter Devos, who won the FEI World Cup Grand Prix in Basel ( SUI) in February last year, will also be on the track, along with his fellow riders Gudrun Patteet ( BEL), Rik Hemeryck ( BEL), Wil Vermeir ( BEL), and Jérôme Guéry ( BEL), who has been Hermès ‘ rider partner since 2017, along with a sizable delegation made up of regulars from the Paris Only Marcus Ehning ( GER ) and Simon Delestre ( GER ) have succeeded in achieving the double that Victor Bettendorf ( LUX), who won his first 5* grand prix at Saut Hermès last year, will be present.

In addition to the experienced Roger- Yves Bost ( FRA ), the reigning French Pro Elite champion Edward Levy ( FRA ), Kevin Staut ( FRA ), who has won three CSI 5* titles since the start of the year, and Olivier Perreau ( FRA ), partner rider of GL events, who was the author of a double clear round in the Abu Dhabi Nations League in January, France will have 16 representatives from this year. The younger generation will also be well represented, particularly Julien Anquetin, who has seven victories and three podium finishes in 4* and 5* competitions since December, or even Jeanne Sadran ( FRA ), who is gearing up to compete in her first FEI World Cup Final after taking second place in the FEI World Cup Grand Prix in Bordeaux in February.

In the Hermès skills events, Germany, Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Great Britain, Ireland, Switzerland and Sweden will provide two cαndidates under 25 years σld. Among them, the medalists of the last European Young Riders team championships, the Belgian Jules van Hoydonck ( 21 years old – silver medalist ) and the British Claudia Moore ( 19 years old – bronze medalist ), or the Irishman Coen Williams ( 18 years old ), reigning European Junior team champion. France, which placed third in the most important event last year, will rely on Jules Orsolini ( FRA ) and Wiliam Ligier de la Prade ( FRA ), who compete regularly side-by-side during the Young Riders Nations Cups. Hermès’s skill tests frequently provide an opportunity to realize fantastic family adventures. This year, Mathieu Guéry ( BEL), 19 years old, and Matias Larocca ( ARG ), 25 years old, will also be present to defend the colors of their countries, while their fathers will appear at the start of the CSI 5*.

Source: Press Release ( translated &, edited ) from Saut Hermès

Photo: © Saut Hermès / Christophe Tanière

Related

Categories: English, Jumper News France, Preview

Identified as: Chevaux, CSI 5*, Equestrian, Events, Fédération Française d’Equitation, FFE, Grand Palais, Hermès, Horses, Jumper News, Jumper News France, Saut Hermès, Saut Hermès des Grand Palais, Showjumping

0 notes

Text

Get ready for one of the simplest, but most important, Spanish vocabulary lessons you’ll have all week! Learning all the numbers in Spanish is a serious task.

0 notes

Text

Get ready for one of the simplest, but most important, Spanish vocabulary lessons you’ll have all week! Learning all the numbers in Spanish is a serious task.

0 notes

Text

Get ready for one of the simplest, but most important, Spanish vocabulary lessons you’ll have all week! Learning all the numbers in Spanish is a serious task.

0 notes

Text

ELEVATED NUMBERS

In old buildings here, apartment numbers are assigned according to the floor and the door number. So the number of my digs here, is 3º4ª, Spanish for third (floor,) fourth (door.) Pictured below  are the third and fourth (3ª and 4ª) doors, with their ordinal numbers in a totally cool, 1920s hand-drawn font. Numbering doors is pretty straightforward, but the system of numbering floors here, can feel kind of deceptive to someone from the US. Look at the pictured elevator buttons, and you’ll discover that I’m actually on the SIXTH floor! That’s because the first three floors here are traditionally named Planta Baja, Entresuelo, and Principal. Luckily there’s an elevator!

0 notes

Note

I know there are only two contractions in Spanish but what about contracted abbreviations, words you wouldn't pronounce contracted but would write them that way? For example, "cont'd" for "continued"?

There are plenty of abbreviations in Spanish like BBAA (bellas artes = fine arts), or RRHH (recursos humanos = human resources/HR)

Others are like etc for etcétera, vs for versus

Or PD which is PS in letters - literally posdata or postdata for "postscript"

Some that I've seen are like núm. for número, pág. for página, vol. for volumen or p. ej. as por ejemplo

You may also see dcho/a for derecho/a "right", and izq. / izdo/a / izqdo/a for izquierdo/a for "left"

Two others to know:

a.e.c -> antes de la era común = "BCE" or "before the common era" or BC

e.c. -> era común = "common era" or "AD"

Really common are the abbreviations for ordinal numbers

1er -> primer = first

1ero/a -> primero/a = first

2do/a -> segundo/a = second

3er -> tercer = third

3ero/a -> tercero/a = third

4to/a -> cuarto/a = fourth

5to/a -> quinto/a = fifth

6to/a -> sexto/a = sixth

7mo/a -> séptimo/a = seventh

8vo/a -> octavo/a = eighth

9no/a -> noveno/a = ninth

10mo -> décimo/a = tenth

These are the equivalents of using 1st, 2nd, 3rd etc. in English. You'll also sometimes see symbols that are like a tiny floating O or A to depict gender, they'll look sort of like the symbol for degrees

Most commonly it's for terms of address like Vd. / vmd = Vuestra Merced [Your Worship/Lordship/Ladyship], though this is older Spanish

Ud. = Usted

Uds. = Ustedes

D. = Don = "Mr."

Dña. = Doña = Mrs.

Sr. = Señor = Mr.

Sra. = Señora = Mrs. / Ma'am

Srta. = Señorita = Miss

Dr. = Doctor

Dra. = Doctora = [female] Doctor

And you get some that are abbreviations that can become their own words like las mates is short for las matemáticas so las mates is "math" rather than "mathematics"... or profe is a common way to address teachers in a friendly way like "teach"

Other common ones you might see are the ones for countries like EEUU is los Estados Unidos or "United States", or sometimes la RD for la República Dominicana for "Dominican Republic" or P. Rico is Puerto Rico but there are lots of country abbreviations especially for mailing purposes

This is also not talking about terms of address for military

Abreviaturas | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (rae.es)

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

132 Park Ct, San Antonio, Tx 78212 Mls #1667000

See 8,173 homes for sale in San Antonio along with homes for hire in San Antonio directly from the Official MLS Site. Search San Antonio Real Estate and discover real property listings for sale and actual property for hire on HAR.com. View recently listed homes for sale and San Antonio homes for rent, trending actual property in San Antonio, recently sold homes in San Antonio, home values in San Antonio, colleges new home builders san antonio in San Antonio and neighborhoods. You can also narrow your search to find San Antonio single household homes, townhouses / condos in San Antonio, residences in San Antonio and more. Homes for sale in San Antonio, TX have a median itemizing home worth of $294,000. There are energetic homes for sale in San Antonio, TX, which spend a median of 84 days on the market.

Texas German is greatest described as an anglicized-German dialect with a Texas twang. Many older generations in New Braunfels and Fredericksburg still speak Texas German to this present day. In 1845, the United States finally determined to annex Texas and include it as a state in the Union. Though the us in the homes for sale san antonio tx end received, the warfare was devastating to San Antonio. By its finish, the population of the city had been reduced by almost two-thirds, to 800 inhabitants. Bolstered by migrants and immigrants, by 1860 at the start of the American Civil War, San Antonio had grown to a city of 15,000 individuals.

The council hires a metropolis supervisor to handle day-to-day operations. The council effectively capabilities as the city's legislative physique with the town supervisor appearing as its chief government, responsible for the management of day-to-day operations and execution of council legislation homes for sale san antonio. San Antonio hosts the NCAA soccer Alamo Bowl every December, performed among the Big XII and Pac-12 each December in the Alamodome. Army All-American Bowl, performed annually in the Alamodome and televised stay on NBC.

The sale of surplus property is subject to City Departmental and public utility review, Planning Commission suggestion and City Council approval. It is the duty of potential consumers to look at all applicable building codes and zoning ordinances. The City makes no representation or warranty regarding new homes san antonio zoning, situation of title or use. Further, the City requires canvassing of all related City Departments and public utilities and so cannot guarantee the availability of any properties for a surplus sale. Public Works Real Estate constructed and maintains a property platform that shows all City-owned property.

When you register or work together with an MHVillage web site, your provide info similar to your name, tackle, e mail tackle, zip code, telephone numbers, and different data. You may also provide information about your personal home should you listing it for sale or request a valuation. Once you register with MHVillage and sign in to its companies, you are not nameless. MHVillage may combine details about you that it has gathered with info that it could obtain from business partners or different sources. You have reached this page as a outcome of you are trying to access our website from an space the place MHVillage doesn't present services or products.

The age of town's population was distributed as 28.5% underneath the age of 18, 10.8% from 18 to 24, 30.8% from 25 to forty four, 19.4% from forty five to sixty four, and 10.4% who are 65 years of age or older. In San Antonio, 48% of the population had been males, and 52% of the population were home builders in san antonio females. For each one hundred females age 18 and over, there were 89.7 males. Natural vegetation in the San Antonio area includes oak-cedar woodland, oak grassland savanna, chaparral brush, and riparian woodland. San Antonio is on the westernmost limit for each Cabbage palmetto and Spanish moss.

0 notes

Text

Twenty Nine Oaks Ranch

A small but growing community in the Santa Monica Mountains, Agoura Hills is bordered by Ventura County and Westlake Village. The city is a part of the South Coast Air Basin. It's home to endangered Southern California Distinct Population Segment steelhead and mountain lions. There are dozens of local plant species that are unique to the area.

One of the most scenic roads in the community is Agoura Road. Lined with large mature oak trees, the road has occasional vistas to the Simi Hills to the north. It is currently two lanes, but will eventually become a four-lane arterial.

There are six primary ridgelines in Agoura Hills. They create important viewsheds in the community, and they are space-defining features. These ridgelines have slopes greater than 25 percent.

Agoura Hills has a number of blue-line streams that intermittently transport water. These streams include improved channels, and unimproved creeks. Some of these streams are part of an open space corridor in the northwest quadrant of the City.

Open space land around the community is an essential component to the quality of life and civic pride of residents. It protects natural resources and wildlife, and provides habitat for residents and visitors. Additionally, it preserves visual beauty and provides recreational opportunities. Moreover, it serves as a gateway to the nearby Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

The City's adopted Zoning Ordinance contains measures to protect the SEA, maintain the environment, and limit development. New developments must undergo a plan check and obtain a conditional use permit. In addition, new construction must meet specific environmental requirements.

Agoura Hills is part of the California chaparral and woodlands ecoregion. It's an area that's been inhabited by Chumash Native Americans for thousands of years. Later, Spanish Franciscan missionaries settled the area in the late 18th century. This area was a popular stage stop for travelers because of its natural spring. Today, it is home to several hundred different plant species, including native oaks, which are protected by the Agoura Hills Oak Tree Ordinance.

Agoura Hills is situated between the Simi Hills and the Santa Monica Mountains. It is one of the most highly populated areas in Los Angeles County, with more than 20 thousand people living there. However, it remains a beautiful and quaint community with custom charm.

While the land in the southern section of the City has been developed, most of the area south of Agoura Road is undeveloped. There is also a research and development park in the area. Eventually, this portion of the community will be redeveloped with a variety of commercial uses. Currently, the only location within the community where mining activity has been documented is in Liberty Canyon.

Agoura Hills is a community of great character. While the area has grown over the past several decades, it retains its historic charm and custom beauty. The community's commitment to conservation is an important part of maintaining its clean air and energy resources. Furthermore, it ensures the health and safety of residents, as well as the ongoing availability of finite resources.

1 note

·

View note

Text

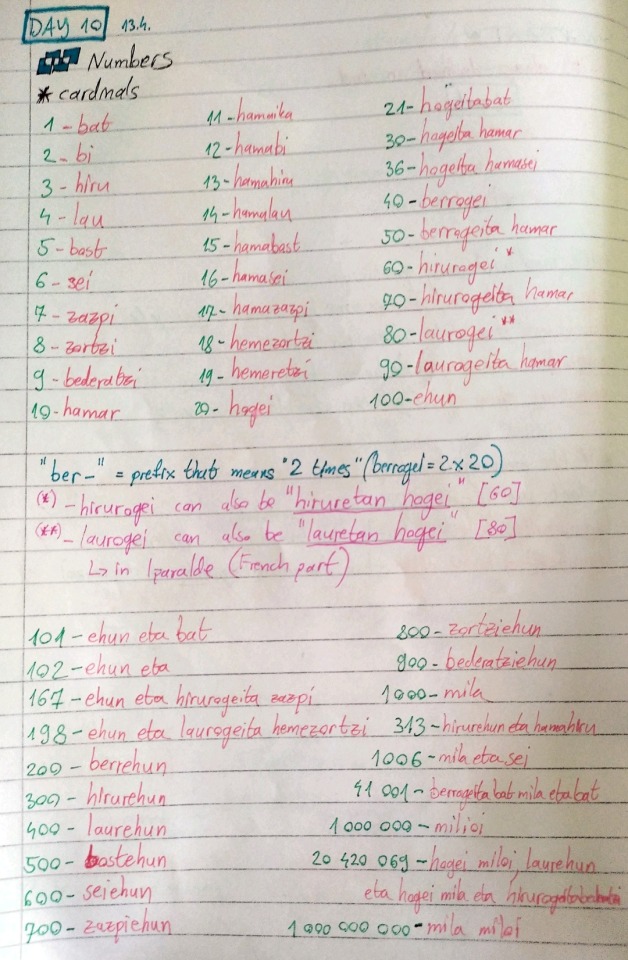

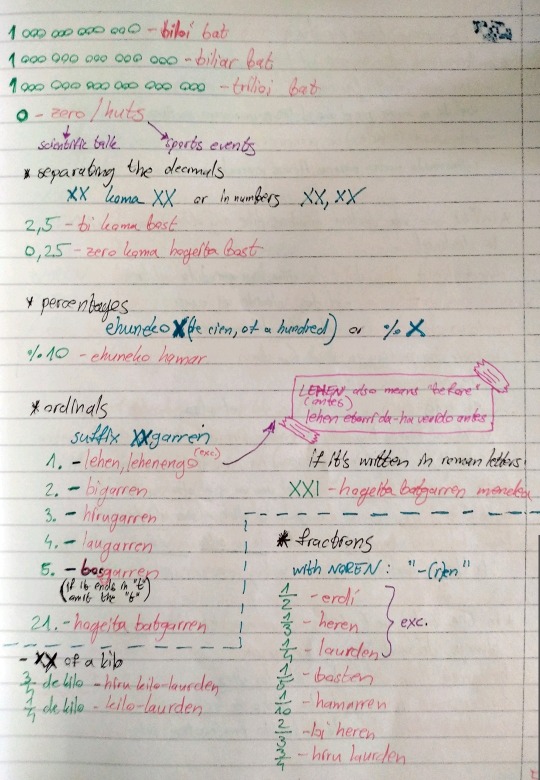

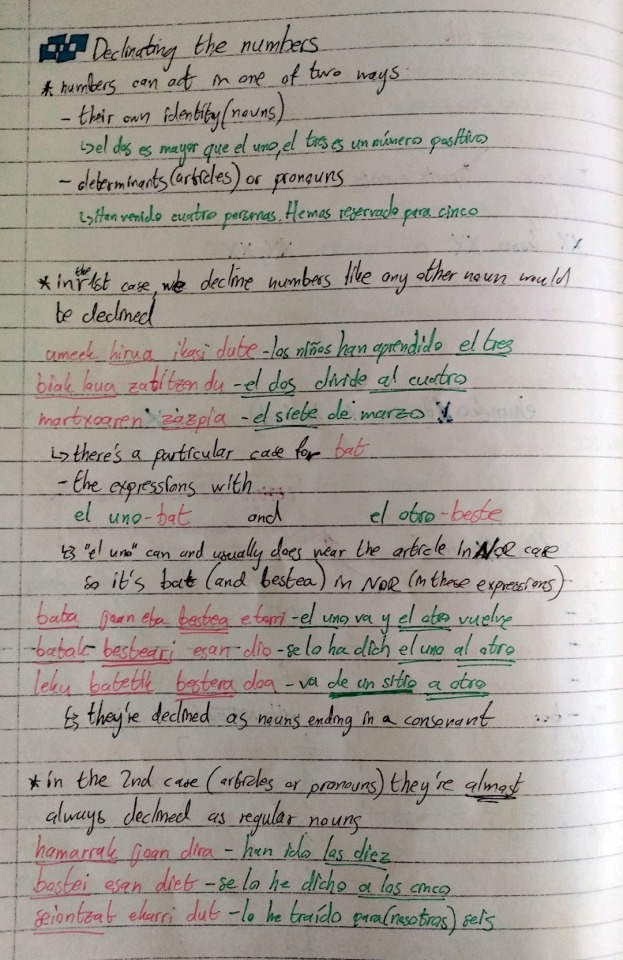

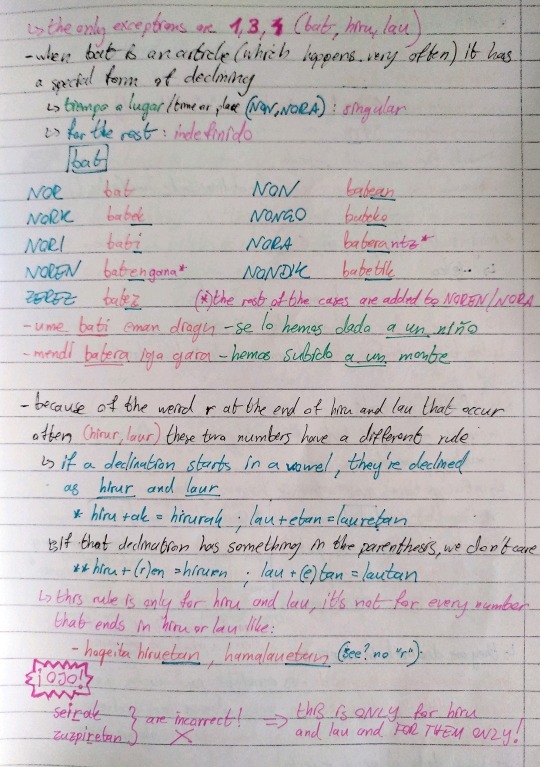

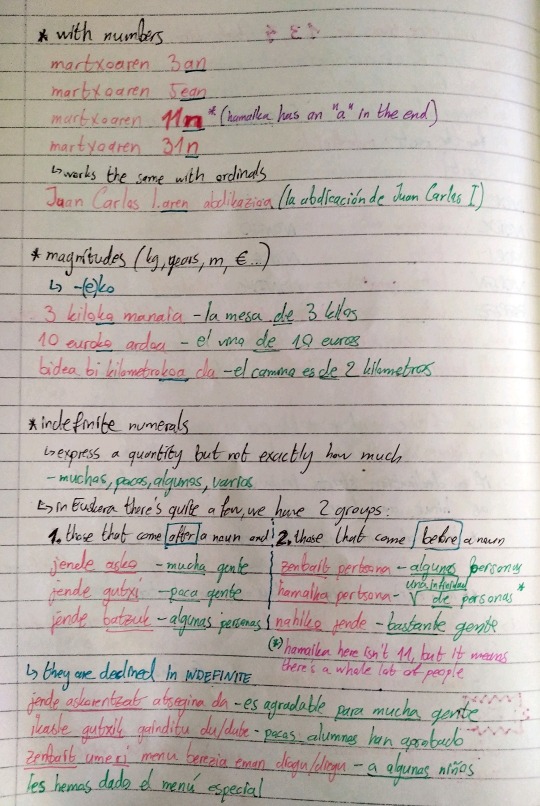

Days 10-14 of the immersive Euskara learning challenge (10,11,12,13,14/14)

Kaixo guztioi!

21. video: numbers (cardinals, ordinals, fractions)

I've mastered the cardinals but I haven't yet used ordinals much and fractions at all, but numbers are something we all learn along the way anyway so I'm not stressed about going through ordinals and fractions.

22. video: declinating the numbers

This I haven't used much but it's not complicated.

P.S. there's a small bit of this lesson included in the first picture of the video 23

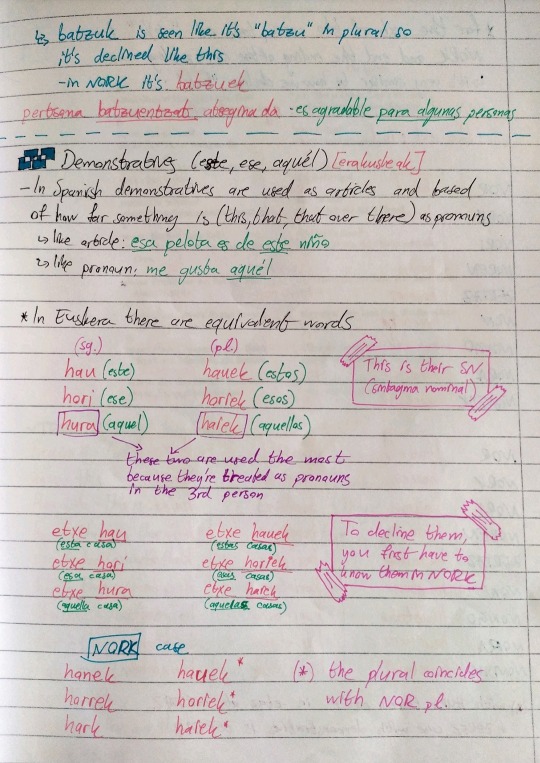

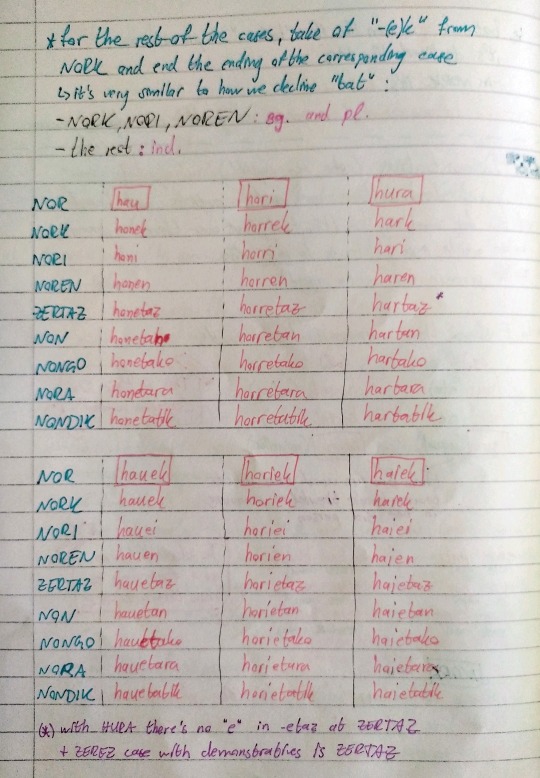

23. video: demonstratives (this, that, that over there)

Oh yay, I finally have the table of all demonstratives. I had been wondering about this since the vey beginning

In the meantime, there have been 3 more videos published in the playlist and the videos from 24-26 aren't included in this challenge. Later on I'll probably watch them too and when I do I will just make a separate post. But this is it for this challenge.

Thoughts:

For the past 5 months I've been studying from the book called "The Basque language: a practical introduction" by Alan R. King and even though that book is amazingly put together and everything is explained step by step with exercises, going through this playlist helped me massively. I always say that this language is more logical than hard, and by having gone through the playlist, it's much easier to connect things I've learned from there during the course of this book.

If your Spanish level is high enough, you definitely won't regret watching the playlist and using it the way I did. And I definitely recommend this channel "Oromen", as well as "Euskara Satorra" for learning Euskara, but both are with explanations in Spanish (though the creators know fluent English, so you can ask them in the comments)

I hope this benefits someone one day :) I know I had fun, so to all language enthusiasts that are interested in Euskara, I recommend you to do this challenge

Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 | Day 9 | Days 10-14

#langblr#languages#language learning#language#euskara#euskera#euskara langblr#basque#basque langblr#euskera langblr#euskara challenge#basque language#euskadi#euskal herria

0 notes

Text

I.5.4 How will anything ever be decided by all these meetings?

Anarchists have little doubt that the confederal structure will be an efficient means of decision making and will not be bogged down in endless meetings. We have various reasons for thinking this. After all, as Murray Bookchin once noted, ”[h]istory does provide us with a number of working examples of forms that are largely libertarian. It also provides us with examples of confederations and leagues that made the co-ordination of self-governing communities feasible without impinging on their autonomy and freedom.” [The Ecology of Freedom, p. 436]

Firstly, we doubt that a free society will spend all its time in assemblies or organising confederal conferences. Certain questions are more important than others and few anarchists desire to spend all their time in meetings. The aim of a free society is to allow individuals to express their desires and wants freely — they cannot do that if they are continually at meetings (or preparing for them). So while communal and confederal assemblies will play an important role in a free society, do not think that they will be occurring all the time or that anarchists desire to make meetings the focal point of individual life. Far from it!

Thus communal assemblies may occur, say, once a week, or fortnightly or monthly in order to discuss truly important issues. There would be no real desire to meet continuously to discuss every issue under the sun and few people would tolerate this occurring. This would mean that such meetings would current regularly and when important issues needed to be discussed, not continuously (although, if required, continuous assembly or daily meetings may have to be organised in emergency situations but this would be rare). Nor is it expected that everyone will attend every meeting for ”[w]hat is decisive, here, is the principle itself: the freedom of the individual to participate, not the compulsive need to do so.” [Op. Cit., p. 435] This suggests that meetings will be attended by those with a specific interest in an issue being discussed and so would be focused as a result.

Secondly, it is extremely doubtful that a free people would desire waste vast amounts of time at such meetings. While important and essential, communal and confederal meetings would be functional in the extreme and not forums for hot air. It would be the case that those involved in such meetings would quickly make their feelings known to time wasters and those who like the sound of their own voices. Thus Cornelius Castoriadis:

“It might be claimed that the problem of numbers remains and that people never would be able to express themselves in a reasonable amount of time. This is not a valid argument. There would rarely be an assembly over twenty people where everyone would want to speak, for the very good reason that when there is something to be decided upon there are not an infinite number of options or an infinite number of arguments. In unhampered rank-and-file workers’ gatherings (convened, for instance, to decide on a strike) there have never been ‘too many’ speeches. The two or three fundamental opinions having been voiced, and various arguments exchanged, a decision is soon reached.

“The length of speeches, moreover, often varies inversely with the weight of their content. Russian leaders sometimes talk on for four hours at Party Congresses without saying anything … For an account of the laconicism of revolutionary assemblies, see Trotsky’s account of the Petrograd soviet of 1905 — or accounts of the meetings of factory representatives in Budapest in 1956.” [Political and Social Writings, vol. 2, pp. 144–5]

As we shall see below, this was definitely the case during the Spanish Revolution as well.

Thirdly, as these assemblies and congresses are concerned purely with joint activity and co-ordination. Different associations and syndicates have a functional need for co-operation and so would meet more regularly and take action on practical activity which affects a specific section of a community or group of communities. Not every issue that a member of a community is interested in is necessarily best discussed at a meeting of all members of a community or at a confederal conference. As Herbert Read suggested, anarchism “proposes to liquidate the bureaucracy first by federal devolution” and so “hands over to the syndicates all … administrative functions” related to such things as “transport, and distribution, health and education.” [Anarchy and Order, p. 101] Such issues will be mainly discussed in the syndicates involved and so community discussion would be focused on important issues and themes of general policy rather than the specific and detailed laws discussed and implemented by politicians who know nothing about the issues or industries at hand.

By reducing conferences to functional bodies based on concrete issues, the problems of endless discussions can be reduced, if not totally eliminated. In addition, as functional groups would exist outside of these communal confederations (for example, industrial collectives would organise conferences about their industry with invited participants from consumer groups), there would be a limited agenda in most communal get-togethers.

In other words, communal assemblies and conferences will have specific, well defined agendas, and so there is little danger of “politics” (for want of a better word!) taking up everyone’s time. Hence, far from discussing abstract laws and pointless motions on everything under the sun and on which no one actually knows much about, the issues discussed in these conferences will be on specific issues which are important to those involved. In addition, the standard procedure may be to elect a sub-group to investigate an issue and report back at a later stage with recommendations. The conference can change, accept, or reject any proposals. As Kropotkin argued, anarchy would be based on “free agreement, by exchange of letters and proposals, and by congresses at which delegates met to discuss well specified points, and to come to an agreement about them, but not to make laws. After the congress was over, the delegates [would return] … not with a law, but with the draft of a contract to be accepted or rejected.” [Conquest of Bread, p. 131]

Is this system fantasy? Given that such a system has existed and worked at various times, we can safely argue that it is not. Obviously we cannot cover every example, so we point to just two — revolutionary Paris and Spain.

As Murray Bookchin points out, Paris “in the late eighteenth century was, by the standards of that time, one of the largest and economically most complex cities in Europe: its population approximated a million people … Yet in 1793, at the height of the French Revolution, the city was managed institutionally almost entirely by [48] citizen assemblies… and its affairs were co-ordinated by the Commune ... and often, in fact, by the assemblies themselves, or sections as they were called, which established their own interconnections without recourse to the Commune.” [“Transition to the Ecological Society”, pp. 92–105, Society and Nature, no. 3, p. 96]

Here is his account of how communal self-government worked in practice:

“What, then, were these little-know forty-eight sections of Paris … How were they organised? And how did they function?

“Ideologically, the sectionnaires (as their members were called) believed primarily in sovereignty of the people. This concept of popular sovereignty, as Albert Soboul observes, was for them ‘not an abstraction, but the concrete reality of the people united in sectional assemblies and exercising all their rights.’ It was in their eyes an inalienable right, or, as the section de la Cite declared in November 1792, ‘every man who assumes to have sovereignty will be regarded as a tyrant, usurper of public liberty and worthy of death.’

“Sovereignty, in effect, was to be enjoyed by all citizens, not pre-empted by ‘representatives’ … The radical democrats of 1793 thus assumed that every adult was, to one degree or another, competent to participate in management public affairs. Thus, each section … was structured around a face-to-face democracy: basically a general assembly of the people that formed the most important deliberative body of a section, and served as the incarnation of popular power in a given part of the city … each elected six deputies to the Commune, presumably for the purpose merely of co-ordinating all the sections in the city of Paris.

“Each section also had its own various administrative committees, whose members were also recruited from the general assembly.” [The Third Revolution, vol. 1, p. 319]

Little wonder Kropotkin argued that these “sections” showed “the principles of anarchism … had their origin, not in theoretical speculations, but in the deeds of the Great French Revolution” [The Great French Revolution, vol. 1, p. 204]

Communal self-government was also practised, and on a far wider scale, in revolutionary Spain where workers and peasants formed communes and federations of communes (see section I.8 for fuller details). Gaston Leval summarised the experience:

“There was, in the organisation set in motion by the Spanish Revolution and by the libertarian movement, which was its mainspring, a structuring from the bottom to the top, which corresponds to a real federation and true democracy … the controlling and co-ordinating Comites, clearly indispensable, do not go outside the organisation that has chosen them, they remain in their midst, always controllable by and accessible to the members. If any individuals contradict by their actions their mandates, it is possible to call them to order, to reprimand them, to replace them. It is only by and in such a system that the ‘majority lays down the law.’

“The syndical assemblies were the expression and the practice of libertarian democracy, a democracy having nothing in common with the democracy of Athens where the citizens discussed and disputed for days on end on the Agora; where factions, clan rivalries, ambitions, personalities conflicted, where, in view of the social inequalities precious time was lost in interminable wrangles …

“Normally those periodic meetings would not last more than a few hours. They dealt with concrete, precise subjects concretely and precisely. And all who had something to say could express themselves. The Comite presented the new problems that had arisen since the previous assembly, the results obtained by the application of such and such a resolution . .. relations with other syndicates, production returns from the various workshops or factories. All this was the subject of reports and discussion. Then the assembly would nominate the commissions, the members of these commissions discussed between themselves what solutions to adopt, if there was disagreement, a majority report and a minority report would be prepared.

“This took place in all the syndicates throughout Spain, in all trades and all industries, in assemblies which, in Barcelona, from the very beginnings of our movement brought together hundreds or thousands of workers depending on the strength of the organisations. So much so that the awareness of the duties, responsibilities of each spread all the time to a determining and decisive degree …

“The practice of this democracy also extended to the agricultural regions … the decision to nominate a local management Comite for the villages was taken by general meetings of the inhabitants of villages, how the delegates in the different essential tasks which demanded an indispensable co-ordination of activities were proposed and elected by the whole assembled population. But it is worth adding and underlining that in all the collectivised villages and all the partially collectivised villages, in the 400 Collectives in Aragon, in the 900 in the Levante region, in the 300 in the Castilian region, to mention only the large groupings … the population was called together weekly, fortnightly or monthly and kept fully informed of everything concerning the commonweal.

“This writer was present at a number of these assemblies in Aragon, where the reports on the various questions making up the agenda allowed the inhabitants to know, to so understand, and to feel so mentally integrated in society, to so participate in the management of public affairs, in the responsibilities, that the recriminations, the tensions which always occur when the power of decision is entrusted to a few individuals, be they democratically elected without the possibility of objecting, did not happen there. The assemblies were public, the objections, the proposals publicly discussed, everybody being free, as in the syndical assemblies, to participate in the discussions, to criticise, propose, etc. Democracy extended to the whole of social life.” [Collectives in the Spanish Revolution, pp. 205–7]

These collectives organised federations embracing thousands of communes and workplaces, whole branches of industry, hundreds of thousands of people and whole regions of Spain. As such, it was a striking confirmation of Proudhon’s argument that under federalism “the sovereignty of the contracting parties … serves as a positive guarantee of the liberty of … communes and individuals. So, no longer do we have the abstraction of people’s sovereignty … but an effective sovereignty of the labouring masses.” The “labouring masses are actually, positively and effectively sovereign: how could they not be when the economic organism — labour, capital, property and assets — belongs to them entirely … ?” [Anarchism, vol. 1, Robert Graham (ed.), p. 75]

In other words, it is possible. It has worked. With the massive improvements in communication technology it is even more viable than before. Whether or not we reach such a self-managed society depends on whether we desire to be free or not.

#anarchist society#practical#practical anarchism#practical anarchy#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk

2 notes

·

View notes