#Spanish Ordinals

Text

Bookshelf Tours

All for the Game

I had to rearrange my shelves recently - my CD collection was lined up on top of my laundry bin, but it just got too big, and needed a full shelf. It was the perfect opportunity to make an "All for the Game" shelf, and finally have them all lined up together!

1. This is the Italian version, and it's a gorgeous hardback omnibus edition! It's the only hardback edition I've found (so far - I can't wait for the Rainbow Crate editions!) and it's also the only omnibus edition I've seen.

2. These are the French editions. The covers are really cool, and the titles translate to "Well Hidden Secrets", "Never Give Up", and "A Reason to Live". Honestly, I love that. Such cool titles!

3. The "Pipe Dream" fanzine by @llstarcasterll is so, so cool! It's full of the most gorgeous artwork, so is totally worth buying if you can get your hands on it. If I was flush with cash, I'd buy like, six of them, so I could pull them apart and put the pictures on my wall, in my diary, in my scrapbook.

4. The Spanish covers use the same artwork as the French ones, so I probably didn't need both, but I'm obsessive. These ones have the advantage of having really awesome chapter heading art.

5. These are the Russian editions. The artwork is, I believe, by @kiiakostet. This is some of my absolute favourite AFTG artwork, and I wish they were available as dustjackets for the English editions.

6. And speaking of dustjackets: These replacement jackets are by @llstarcasterll. They're beautiful, and I love how the spines look! I'm really looking forward to getting the "Raven Cycle" and "The Sunshine Court" jackets by the same artist. No idea where they'll go, though, the shelf is full!

7. And these are the @ouijacine jackets! I also have the prints of the artwork framed on my "All for the Game" art wall, so with this book facing outwards, it just looks like I'm super obsessed with this particular artwork. Oh wait. I am.

8. The originals. The ugly, terribly designed English language originals. I love them so much. These copies are messy and well-thumbed, and stuffed to bursting with colour co-ordinated page tabs. They are more annotation than book, at this point.

9. Ok. Technically, this isn't AFTG. But these copies of "The Raven Cycle" get a space on the shelf because the jackets are also designed by @ouijacine. Also, it makes the book stack sit at the exact perfect height.

10a. Special mention for the shelves above and below. The shelf above is my "Leigh Bardugo" collection, including some collector's editions, those gorgeous Illumicrate editions of the Nikolai duology, several beautiful copies of the Alex Stern books, and "The Familiar", which I still haven't read.

10b. The shelf below is the reason for the rearrange. I needed a long shelf, and a ridiculously tall one. These are my BTS albums. Yeah, I'm that person now. I actually still have a fair few to get, so there's a chance I'm going to overfill this shelf too. You can just see a couple of my boys peeping out over the top of the CDs, in flip photo form. I want to get one for each of the members, but weverse shipping is fucking extortionate.

At the moment, these all fit perfectly on this shelf, but with the many editions of the TSC duology I'm going to be buying, and the Rainbow Crate hardback editions? Yeah, I'm gonna need a bigger shelf.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adjective Placement in Spanish Overview

With regards to adjective placement, I know I linked that bigger post I made about what the placement of adjectives generally mean but I'll give a very brief overview and if anyone has any specific questions please let me know.

IN GENERAL for like 70-ish percent of the time, adjectives go behind the noun in Spanish. These are your basic everyday adjectives that just describe nouns; el gato negro "the black cat", la mujer alta "the tall woman", los datos importantes "the important data", las tormentas peligrosas "the dangerous storms"

And again, IN GENERAL, if an adjective precedes the noun it is as if you bolded or italicized the adjective. It makes the adjective really stand out because of how out of the ordinary it is. It's very commonly used in poetry, writing, or for hyperbole:

La cruel realidad = The cruel reality

La fea verdad = The ugly truth

Mis sinceras disculpas = My sincere apologies

Mi más sentido pésame = My most heartfelt condolences/regrets

If you were looking at it more poetically you could think of "blue sky"... el cielo azul "the blue sky" is everyday Spanish, very typical. Saying el azul cielo "the blue sky" draws the eye to azul making it seem like "blue" is the most important or noteworthy thing about it

You typically see this kind of construction in everyday Spanish with expressions of gratitude, grief, horror, deep love, or any very strong emotions or when you're trying to make an impact

(More below)

-

Note: This will impact certain aspects of grammar, such as the nouns that are actually feminine but take a general masculine article such as el agua, el arma, el hada, el hambre, el águila etc.

As an example:

El hada madrina = Fairy Godmother

La buena hada = The good fairy

To further explain this rule - el hada is written with a masculine article. This is because it has its vocal stress on the first syllable and begins with A- or HA- [where H is silent]; and treating it as feminine would cause the sounds to run together, so the el adds a kind of phonetic break to preserve the sound; but in plural it will be las hadas "fairies/fey"

A word like this would still retain its normal functions as a feminine word, thus el agua bendita "holy water", el águila calva "bald eagle", el ave rapaz "bird of prey", and then in this case el hada madrina "fairy godmother"

By adding a separate word in front, you interrupt that la + A/HA construction and create a hiatus in the sounds already... so you can then treat it like a normal feminine noun, la buena hada "the good fairy"

You might also see this with grande "big" and its other form gran "great/large", el águila grande "the big eagle" vs. la gran águila "the great eagle"

-

Moving aside from the normal grammar, we now enter the exceptions. First - determiners.

There are a handful of adjectives that are known as determiners which come before the noun and they provide an important function in communicating things like number, possession, and location

The most common determiners include:

Definite articles [el, la, los, las]

Indefinite articles [un, una, unos, unas]

Possessives [mi, tu, su, nuestro/a, vuestro/a]

Demonstratives [este/esta, ese/esa/, aquel/aquella]

Interrogatives [qué, cuál/cuáles, cuánto/a]

(Also work as exclamatory determiners which just means ¡! instead of ¿?)

Cardinal numbers [uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco etc]

Ordinal numbers [primer/primera, segundo/a, tercer/tercera, cuarto/a, quinto/a, etc]

There are also a few determiners of quantity such as mucho/a "a lot/many/much", todo/a "all/every", cada "each", vario/a "various/many", poco/a "few/less", tal "such", tan "so much" / tanto/a "so many", algún/alguna and ningún/ninguna etc.

And it will generally apply to más and menos "more" and "less", and sometimes mejor/peor "better/worse"

-

Note: With possessives is that there are two forms depending on adjective placement:

mi amigo/a = my friend

mis amigos / amigas = my friends

un amigo mío = a friend of mine

una amiga mía = a friend of mine [f]

unos amigos míos = a few friends of mine

unas amigas mías = a few friends [f] of mine

All the pronouns have their own version of this possessive pattern

mi(s) and mío/a, tu(s) and tuyo/a, su(s) and suyo/a, and then nuestro/a and vuestro/a are the same but the adjective placement is different

As an example - nuestro país "our country" vs. el país nuestro "the country of ours", or nuestros familiares "our family members" vs. unos familiares nuestros "some family members of ours"

A common religious example - Nuestra Señora "Our Lady" and then el padrenuestro "the Our Father prayer"

The possessives that come after the noun are usually translated as "of mine/yours/his/hers/ours" etc.

You can also see a few determiners/adjectives in different places in a phrase like - un viejo amigo mío "an old friend of mine" vs. mi viejo amigo "my old friend"

-

As mentioned in the very beginning there are a handful of exceptions

Most notably:

viejo/a = old / elderly

antiguo/a = ancient, old / antique, old

mismo/a = same / self

gran = great, grand

grande = large

And includes propio/a "own / appropriate", as well as bueno/a "good" or malo/a "bad". I discussed a lot of these in more depth in the previous posts and in the one linked above

In many cases the exact meaning is different, even if it's slight - such as el hotel grande "the big hotel" vs. el Gran Hotel "the Grand Hotel"

bueno/a and malo/a are generally either "good" and "kind", or "bad" and "unkind", though the meanings can kind of blur together... as something like la buena hada "the good fairy" isn't so far off from el hada buena "the nice fairy"

When places before though bueno/a turns to buen + masculine, and malo/a turns to mal + masculine

As an example - un buen augurio "good omen", un mal presagio "a bad omen/portent"

.....but in feminine it looks like you'd expect: buena suerte "good luck" vs. mala suerte

Similarly, and one I didn't include the first time is cualquier/cualquiera

cualquier persona = any person

una persona cualquiera = an ordinary person

cualquier in front - regardless of gender - means "any", literally "whichever"

cualquiera in back comes out as "ordinary" or colloquially "any old" [such as un beso cualquiera "an ordinary kiss" / "any old kiss"], or in the case of people it could be like "a person of dubious/unknown background" sort of like "they could be anyone"...

-

And then you run into what I would consider "collocations" which is another word for a set noun or expression

There are some words/expressions that have the adjective in a specific place and you can't really change it or it sounds weird, so you sort of have to learn them as specific units to remember:

las bellas artes = fine arts [lit. "beautiful arts"]

(de) mala muerte = "backwater", "poor / middle of nowhere", a place of ill repute or somewhere very remote or inconsequential [lit. "of a bad death"]

a corto plazo = short-term

a largo plazo = long-term

(en) alta mar = (on) the high seas

alta calidad = high quality

baja calidad = low quality

Blancanieves = Snow White (the character/fairlytale)

la mala hierba, las malas hierbas = weeds [lit. "bad grasses"; plants that grow without you wanting them to or that grow in bad places etc]

los bajos fondos = criminal underworld [lit. "the low depths"]

el más allá = "the great beyond", "the afterlife" [lit. "the more over there/beyond"]

buen/mal augurio = good/bad omen

buen/mal presagio = good/bad omen

buena/mala suerte = good/bad luck

...Also includes all the greetings like buen día / buenos días or buenas noches etc. they're all considered set phrases

There are also many collocations that use adjectives in their normal place that also can't be separated such as los frutos secos "nuts", or el vino tinto/banco "red/white wine" etc.

A collocation just means that they are treating multiple words as set phrases or a singular unit

And again, some history/geographical terms will have these as well:

la Gran Muralla China = Great Wall of China

la Primera Guerra Mundial = First World War

la Segunda Guerra Mundial = Second World War

el Sacro Imperio Romano = Holy Roman Empire

la Antigua Grecia = Ancient Greece

el Antiguo Egipto = Ancient Egypt

(el) Alto Egipto = Upper Egypt

(el) Bajo Egipto = Lower Egypt

Nueva York = New York

Nueva Zelanda = New Zealand

Nuevo México = New Mexico

Nueva Escocia = Nova Scotia [lit. "New Scotland"]

la Gran Manzana = the Big Apple [aka "New York"]

Buenos Aires

There are many such terms

#spanish#langblr#spanish language#learning spanish#spanish grammar#learn spanish#long post#spanish vocabulary#vocabulario

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

Can rare/endangered languages lack new vocabulary? As in, as society has new technology and invents new words and slang, only the more wider used languages have those new words. The less used languages have moved toward home langauge only rather than at schools or in the wider community and certainly not international so they completely lack in such vocabulary because it's never progressed that far. Does that make sense?

Tex: Short answer: No.

Longer answer: New words are always added to a language every generation, which is how a language survives. When this happens, in combination with fewer native speakers, a language may either die off in isolation or become assimilated into a more popular language. It’s crucial that any new words are not simply taken from another language, because that’s how a language is often stifled and subsumed.

To take an example of well-known languages, English is often mined for new words, particularly for technology. In French, the word for computer is not some adaptation of “computer”, but rather the word is ordinateur (Larousse), which comes from the Latin ordinator (Larousse). Now, Latin used to be a lingua franca throughout most of Europe, and because of that there are a lot of words carried over without the extinction of the languages that adopted new words (more or less). English is now a lingua franca, to the same degree of exposure and adoption.

Utuabzu: As Tex said, short answer, no. One of the basic characteristics of natural languages is that they are infinite, that is to say that every natural language is capable of conveying any concept or idea. If a community does not need to discuss something often, their language might need to use a rather roundabout way to do so, but it can be done. If a concept does need to be discussed frequently, then the community will either create a word for it or borrow one from another language. If a concept no longer needs to be discussed frequently, then the word might be repurposed to mean something related or be dropped altogether. This happens all the time, constantly, in every living language. Smaller, more isolated communities tend to experience this more slowly than larger, more interconnected communities, simply because new concepts are introduced to the former more slowly and rarely than to the latter.

English spent the 16th-20th centuries borrowing and coining a huge number of words related to geography, plants and animals, foods and products, because the expansion of the British Empire (and the US), the development of global trade and the industrial revolution brought English speakers into contact with a vast array of new concepts that had never previously needed to be discussed in English. England, being cold and damp, didn’t really require words like ‘jungle’ (borrowed from Hindi) or ‘canyon’ (borrowed from Spanish), nor did a late medieval English speaker need to talk about a ‘bicycle’ or ‘smog’.

The same processes happen in every language, no matter how much some people (Académie Française) try to stop them. Language is ultimately a tool used by a community, and the community will alter it to suit its needs.

The phenomenon you’re describing where different languages are used in different areas of life (called domains*) is called polyglossia (or in older works/works dealing with only two languages/dialects, diglossia), and it’s pretty common. Outside of monolingual speakers of standard national languages (Anglophones tend to be the worst for this) most people in the world experience some degree of polyglossia - usually using their local language or dialect with family/friends and in casual social settings and the standard national language in formal settings - though the degree does vary.

Some polyglossic environments have up to 5 distinct languages in use by any given individual - the example I recall from my sociolinguistics textbook being a sixteen year old named Kalala, from Bukavu in eastern Congo(Democratic Republic of), who spoke an informal variety of Shi at home and with family, and with market vendors of his ethnic group, a formal variety of Shi at weddings and funerals, a kiSwahili dialect called Kingwana with people from other ethnic groups in informal situations, Standard Congolese kiSwahili in formal and workplace situations and with figures of authority, and a youth-coded dialect that draws on languages like French and English called Indoubil with his friends.**

*Important to note here that a domain is both a physical space, eg. the Home, School, Courtroom, and a conceptual space, eg. Family, Work, Business, Politics, Religion. There’s often overlap between these, but polyglossic communities do tend to arrive at a rough unspoken consensus on what language goes with what domain. Most community members would just say that using the wrong language for a domain would feel weird.

**note that this example is pretty old. So old that it still calls the country Zaire. The reference is in Holmes, J., 1992, An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, pp 21-22.

Blue: The USSR presents an interesting case study when it comes to rare languages. It started with Lenin and policies aimed to develop regional languages, down to creating whole writing systems for those that did not have one. Russian was de facto lingua franca and functioned as an official language, but de jure, it was not. The goal of this policy wasn’t just to support literacy and education for different ethnicities; it created, via translations, a common cultural background and was aimed to spread Marxist ideology. If you want people to understand you and accept you, you need to speak their own language.

After these policies shifted, the regional languages didn’t die; they’re still taught in schools and are in use. And one of the important aspects of a language being in use – it grows and develops: as our reality changes, languages have to adapt to it, otherwise they die. And even if there is a “hegemonic” lingua franca that is more used across the board, the government might still be motivated to develop endangered languages, to facilitate the blending of the cultures and to solidify new ideas.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

There A Farm...

And 2008 saw the establishment of yet another micro-farm in Detroit, this one located inside the large city-owned Rouge Park on the west side of town. The 2-acre D-Town Farm is the project of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network. Marilyn Barber, serving as the farm manager, organizes volunteers, especially school children, to come out and prep the soil, plant the sets, harvest the produce, and market the goods.

Detroit has always been a city of gardens. As Patrick Crouch, farm manager at the Earthworks Farm, noted, there are two main reasons for this. First, Detroit, unlike New York or Chicago, is a sprawling city of single-family homes, so residents always had space for vegetable and flower gardens. Second, the auto industry and other heavy manufacturing in the area drew many people from the southern states, people who grew up tending gardens and livestock. More recently, the influx of Spanish-speaking families has brought many people with farming experience from Mexico, Puerto Rico, etc.. So that, while city ordinances still prohibit keeping livestock, there are and have always been people around the city who kept chickens, ducks, rabbits, goats, etc.. And this spring, the Garden Resource Program’s class “Raising Chickens in the City” had 70 participants! That’s 70 new families that will be gathering their own, “farm-fresh” eggs this year in Detroit. And it is strong evidence that Detroit’s urban farm movement is growing broader and sinking deeper roots each year.

#small farms#urban gardening#urban farming#detroit#solarpunk#small farm movement#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dubbed the last lung of Manila, the 5.4-acre Arroceros Forest Park had long been a battleground between the city government and pro-environment organizations before becoming a modern oasis today.

During Spanish colonial rule, the park area was part of the parián or market of Manila. Later in the 19th century, a tobacco factory, known as Fabrica de Arroceros, occupied the site. During the Philippine Revolution in 1896, the park area became a contested battleground zone. Philippine and U.S. forces controlled everywhere in the city except for the small Intramuros, a centuries-old historic district in the city and Spain's last hold-out.

In 1898, the United States purchased the Philippine archipelago for $20 million from Spain. During U.S. control of the archipelago, a military garrison was set up on the park site. When the Philippines finally secured independence from the United States in 1946, the garrison was repurposed into the Department of Education's headquarters.

When the Department of Education moved elsewhere, the site's first park was instated in 1993. Manila government officials developed the park with the help of a private environmental group, the Winner Foundation.

Along with 150 century-old trees that survived World War II, the park now hosts over 3,000 trees, an effort lead by he Manila Seedling Bank.

In 2003, the park was embroiled in another controversy that threatened its existence when then-mayor Lito Atienza wanted to construct a school administration building and teachers' dormitory on a portion of the park despite protests from conservation groups. The groups claimed that of the 8,000 trees in the park in the year 200, only 2,000 trees remained after the buildings were completed in 2007.

In 2020, then-mayor Francisco Domagoso signed an ordinance declaring the area a permanent forest park. On February 4, 2022, the park re-opened after 5 months of rehabilitation.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

[D]omesticated attack dogs [...] hunted those who defied the profitable Caribbean sugar regimes and North America’s later Cotton Kingdom, [...] enforced plantation regimens [...], and closed off fugitive landscapes with acute adaptability to the varied [...] terrains of sugar, cotton, coffee or tobacco plantations that they patrolled. [...] [I]n the Age of Revolutions the Cuban bloodhound spread across imperial boundaries to protect white power and suppress black ambitions in Haiti and Jamaica. [...] [Then] dog violence in the Caribbean spurred planters in the American South to import and breed slave dogs [...].

---

Spanish landowners often used dogs to execute indigenous labourers simply for disobedience. [...] Bartolomé de las Casas [...] documented attacks against Taino populations, telling of Spaniards who ‘hunted them with their hounds [...]. These dogs shed much human blood’. Many later abolitionists made comparisons with these brutal [Spanish] precedents to criticize canine violence against slaves on these same Caribbean islands. [...] Spanish officials in Santo Domingo were licensing packs of dogs to comb the forests for [...] fugitives [...]. Dogs in Panama, for instance, tracked, attacked, captured and publicly executed maroons. [...] In the 1650s [...] [o]ne [English] observer noted, ‘There is nothing in [Barbados] so useful as … Liam Hounds, to find out these Thieves’. The term ‘liam’ likely came from the French limier, meaning ‘bloodhound’. [...] In 1659 English planters in Jamaica ‘procured some blood-hounds, and hunted these blacks like wild-beasts’ [...]. By the mid eighteenth century, French planters in Martinique were also relying upon dogs to hunt fugitive slaves. [...] In French Saint-Domingue [Haiti] dogs were used against the maroon Macandal [...] and he was burned alive in 1758. [...]

Although slave hounds existed throughout the Caribbean, it was common knowledge that Cuba bred and trained the best attack dogs, and when insurrections began to challenge plantocratic interests across the Americas, two rival empires, Britain and France, begged Spain to sell these notorious Cuban bloodhounds to suppress black ambitions and protect shared white power. [...] [I]n the 1790s and early 1800s [...] [i]n the Age of Revolutions a new canine breed gained widespread popularity in suppressing black populations across the Caribbean and eventually North America. Slave hounds were usually descended from more typical mastiffs or bloodhounds [...].

---

Spanish and Cuban slave hunters not only bred the Cuban bloodhound, but were midwives to an era of international anti-black co-ordination as the breed’s reputation spread rapidly among enslavers during the seven decades between the beginning of the Haitian Revolution in 1791 and the conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865. [...]

Despite the legends of Spanish cruelty, British officials bought Cuban bloodhounds when unrest erupted in Jamaica in 1795 after learning that Spanish officials in Cuba had recently sent dogs to hunt runaways and the indigenous Miskitos in Central America. [...] The island’s governor, Balcarres, later wrote that ‘Soon after the maroon rebellion broke out’ he had sent representatives ‘to Cuba in order to procure a number of large dogs of the bloodhound breed which are used to hunt down runaway negroes’ [...]. In 1803, during the final independence struggle of the Haitian Revolution, Cuban breeders again sold hundreds of hounds to the French to aid their fight against the black revolutionaries. [...] In 1819 Henri Christophe, a later leader of Haiti, told Tsar Alexander that hounds were a hallmark of French cruelty. [...]

---

The most extensively documented deployment of slave hounds [...] occurred in the antebellum American South and built upon Caribbean foundations. [...] The use of dogs increased during that decade [1830s], especially with the Second Seminole War in Florida (1835–42). The first recorded sale of Cuban dogs into the United States came with this conflict, when the US military apparently purchased three such dogs for $151.72 each [...]. [F]ierce bloodhounds reputed to be from Cuba appeared in the Mississippi valley as early as 1841 [...].

The importation of these dogs changed the business of slave catching in the region, as their deployment and reputation grew rapidly throughout the 1840s and, as in Cuba, specialized dog handlers became professionalized. Newspapers advertised slave hunters who claimed to possess the ‘Finest dogs for catching negroes’ [...]. [S]lave hunting intensified [from the 1840s until the Civil War] [...]. Indeed, tactics in the American South closely mirrored those of their Cuban predecessors as local slave catchers became suppliers of biopower indispensable to slavery’s profitability. [...] [P]rice [...] was left largely to the discretion of slave hunters, who, ‘Charging by the day and mile [...] could earn what was for them a sizeable amount - ten to fifty dollars [...]'. William Craft added that the ‘business’ of slave catching was ‘openly carried on, assisted by advertisements’. [...] The Louisiana slave owner [B.B.] portrayed his own pursuits as if he were hunting wild game [...]. The relationship between trackers and slaves became intricately systematized [...]. The short-lived republic of Texas (1836–46) even enacted specific compensation and laws for slave trackers, provisions that persisted after annexation by the United States.

---

All text above by: Tyler D. Parry and Charlton W. Yingling. "Slave Hounds and Abolition in the Americas". Past & Present, Volume 246, Issue 1, February 2020, pages 69-108. Published February 2020. At: doi dot org/10.1093/pastj/gtz020. February 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#its first of february#while already extensive doumentation of dogs in american south in 1840s to 60s#a nice aspect of this article is focuses on two things#one being significance of shared crossborder collaboartion cooperation of the major empires and states#as in imperial divisions set aside by spain britain france and us and extent to which they#collectively helped each other crush black resistance#and then two the authors also focus on agency and significance of black resistance#not really reflected in these excerpts but article goes in depth on black collaboration#in newspapers and fugitive assistance and public discourse in mexico haiti us canada#good references to transcripts and articles at the time where exslaves and abolitionists#used the brutality of dog attacks to turn public perception in their favor#another thing is article includes direct quotes from government and colonial officials casually ordering attacks#which emphasizes clearly that they knew exactly what they were doing#ecology#indigenous#multispecies#borders#imperial#colonial#tidalectics#caribbean#carceral geography#archipelagic thinking

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

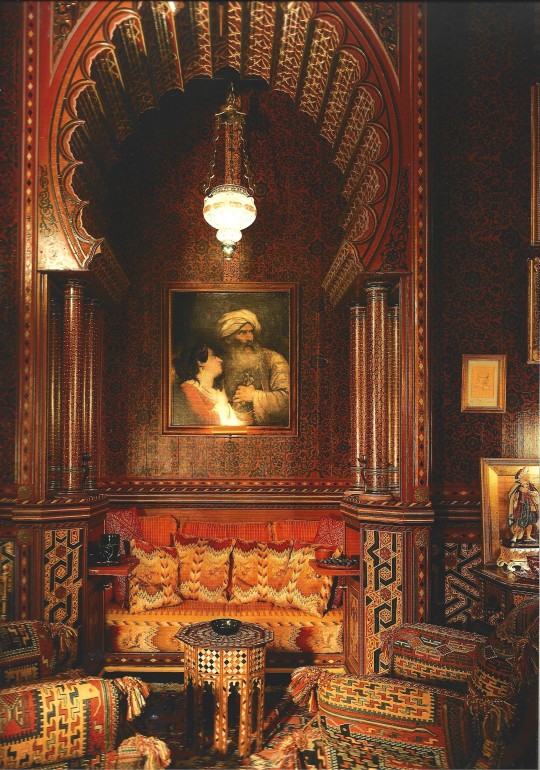

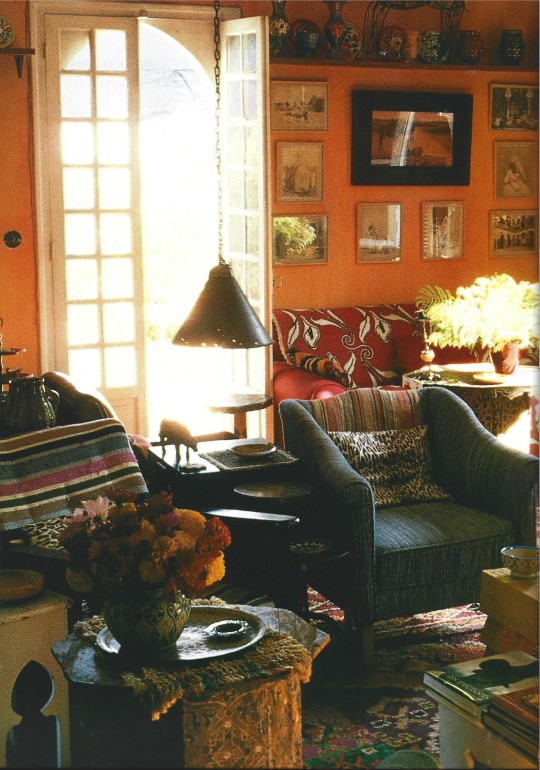

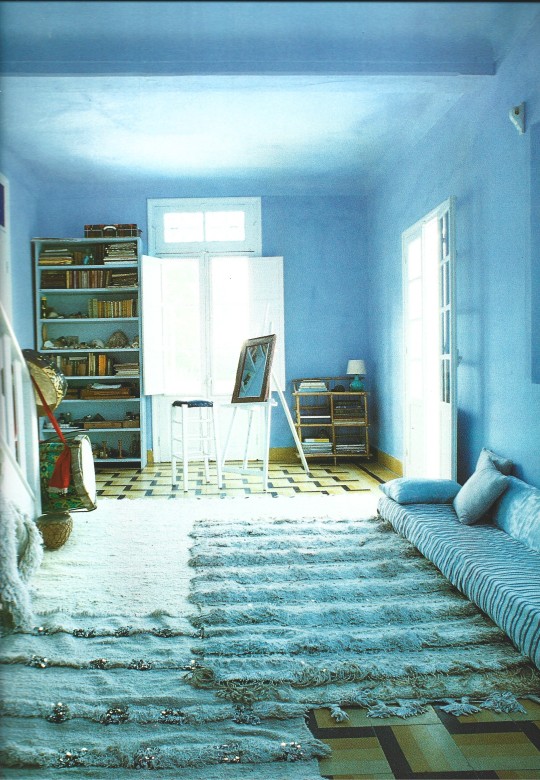

Moroccan Interiors

Lisa Lovatt-Smith, edited by Angelika Muthesius

Photographic co-ordination by Sophie Bausdrand

Benedikt Taschen Verlag, Köln 1998, 320 pages, 24,5x33,8cm, ISBN 3-8228-7656-9 Italian, Spanish, Portuguese

euro 40,00

email if you want to buy : [email protected]

From the Sahara to Tangier on the Mediterranean coast, this book sets out to explore the world of contemporary 'Moroccan Interiors'.

Exploring contemporary interiors in the sun-soaked African nation of Morocco, this breathtaking volume takes readers into the restored palaces in the medinas of Marrakesh as well as humble fishermen's homes at Sisi Moussa d'Aglou.

Cette vue d'ensemble des intérieurs du Maroc nous subjugue comme une visite dans un des nombreux palais de ce pays. Chacune des quarante habitations reproduites ici possède son ambiance individuelle, c'est comme si l'on entrait chaque fois dans une autre pièce : nous passons ainsi des maisons en pisé des villages du sud à l'architecture hispano-moresque des villes impériales, des palais restaurés de la médina de Marrakech aux humbles maisons troglodytes des pêcheurs de Sidi Moussa d'Aglou.

08/10/23

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Thus many collectives did not compete with each other for profits, as surpluses were pooled and distributed on a wider basis than the individual collective.

This process went on in many different unions and collectives and, unsurprisingly, the forms of co-ordination agreed to lead to different forms of organisation in different areas and industries, as would be expected in a free society. However, the two most important forms can be termed syndicalisation and confederationalism (we will ignore the forms created by the collectivisation decree as these were not created by the workers themselves).

Syndicalisation (our term) meant that the CNT’s industrial union ran the whole industry. This solution was tried by the woodworkers’ union after extensive debate. One section of the union, “dominated by the FAI, maintained that anarchist self-management meant that the workers should set up and operate autonomous centres of production so as to avoid the threat of bureaucratisation.” However, those in favour of syndicalisation won the day and production was organised in the hands of the union, with administration posts and delegate meetings elected by the rank and file. However, the “major failure … (and which supported the original anarchist objection) was that the union became like a large firm” and its “structure grew increasingly rigid.” [Ronald Fraser, Blood of Spain, p. 222] According to one militant, “From the outside it began to look like an American or German trust” and the workers found it difficult to secure any changes and “felt they weren’t particularly involved in decision making.” [quoted by Fraser, Op. Cit., p. 222 and p. 223] However, this did not stop workers re-electing almost all posts at the first Annual General Assembly.

In the end, the major difference between the union-run industry and a capitalist firm organisationally appeared to be that workers could vote for (and recall) the industry management at relatively regular General Assembly meetings. While a vast improvement on capitalism, it is hardly the best example of participatory self-management in action.

(...)

The other important form of co-operation was what we will term confederalisation. This system was based on horizontal links between workplaces (via the CNT union) and allowed a maximum of self-management and mutual aid. This form of co-operation was practised by the Badalona textile industry (and had been defeated in the woodworkers’ union). It was based upon each workplace being run by its elected management, selling its own production, getting its own orders and receiving the proceeds. However, “everything each mill did was reported to the union which charted progress and kept statistics. If the union felt that a particular factory was not acting in the best interests of the collectivised industry as a whole, the enterprise was informed and asked to change course.”

This system ensured that the “dangers of the big ‘union trust’ as of the atomised collective were avoided.” [Fraser, Op. Cit., p. 229] According to one militant, the union “acted more as a socialist control of collectivised industry than as a direct hierarchised executive.” The federation of collectives created “the first social security system in Spain” (which included retirement pay, free medicines, sick and maternity pay) and a compensation fund was organised “to permit the economically weaker collectives to pay their workers, the amount each collective contributed being in direct proportion to the number of workers employed.” [quoted by Fraser, Op. Cit., p. 229]

As can be seen, the industrial collectives co-ordinated their activity in many ways, with varying degrees of success."

I.8.4 How were the Spanish industrial collectives co-ordinated?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Wherever Protestantism attained to any influence it revealed itself as a faithful servant of the rising absolutism and granted the state all the rights it had denied to the Roman Church. That Calvinism fought absolutism in England, France and Holland is not significant, for, with this exception: it was less free than any other phase of Protestantism. That it opposed absolutism in those countries is explained by the special social conditions prevailing in them. At its source it was unendurably despotic, and determined the individual fate of men far more completely than the Roman Church had ever tried to do. No other religion has had such a deep and permanent influence on men’s personal lives. [Calvin] continued to convert till nothing was left of humanity.

Calvin was one of the most terrible personalities in history, a Protestant Torquemada, a narrow-hearted zealot, who tried to prepare men for God’s kingdom by the rack and wheel. Crafty and cunning, destitute of all deeper feeling, like a genuine inquisitor he sat in judgment upon the visible weaknesses of his fellowmen and instituted a regular reign of terror in Geneva. No pope ever wielded completer power. The church ordinances regulated the lives of the citizens from the cradle to the grave, reminding them at every step that they were burdened by the curse of original sin, which in the murky light of Calvin’s doctrine of predestination assumed an especially sombre character. All joy of life was forbidden. The whole land was like a penitent’s cell in which there was room only for inner consciousness of guilt and humiliation.... An army of spies infested the land and respected the rights of neither home nor family. Even the walls had ears, for all the faithful were urged to become informers and felt obliged to betray their fellows. In this respect too, political and religious 'orthodoxy' always reach the same result.

Calvin’s criminal code was a unique monstrosity. The least doubt of the dogmas of the new church, if heard by the watchdogs of the law, was punished by death. Frequently the mere suspicion was enough to bring down the death sentence, especially if the accused for some reason or other was unpopular with his neighbours. A whole series of transgressions which had been formerly punished with short imprisonment, under the rulership of Calvinism led to the executioner. The gallows, the wheel and the stake were busily at use in the 'Protestant Rome,' as Geneva was frequently called. The chronicles of that time record gruesome abominations, among the most horrible being the execution of a child for striking its mother, and the case of the Geneva executioner, Jean Granjat, who was compelled first to cut off his mother’s right hand and then to burn her publicly because, allegedly, she had brought the plague into the land. Best known is the execution of the Spanish physician, Miguel Servetus, who in 1553 was slowly roasted to death over a small fire because he had doubted Calvin’s doctrines of the Trinity and predestination. The cowardly and treacherous manner in which Calvin contrived the destruction of the unfortunate scholar throws a gruesome light on the character of that terrible man, whose cruel fanaticism is so uncanny because so frightfully calm and removed from all human feeling." - Rudolf Rocker, Nationalism and Culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

My theory is that since Spaniard ultranationalists don't have colonies in South America and Asia anymore (because Spain still has colonial possessions in Africa) and therefore cannot oppress or steal from the people there anymore, they take out their frustration on the ones who live in their own country whom they consider beneath them and keep supressing their culture, and feel threatened that these cultures have survived and been preserved after centuries of imperialism.

But that's just a theory. uwu

Kaixo anon!

That'd be very possible if there weren't examples of oppression well before the Spanish colonization of half the world, like

The sentence of Ojocastro, 1239

Ordinance of Huesca (1349) that stated: Item nyl corredor nonsia usado que faga mercaduria ninguna que compre nin venda entre ningunas personas faulando en algaravia , ni en abraych nin en basquenç, et qui lo faga pague por coto XXX sol [And in whatever place used as a market, may no goods be bought or sold among people speaking Arabic, Hebrew, or Basque, and whoever may do so shall play 30 sol]. Btw this law ceased to be effective in the 19th century (!!) when Basque had been lost for centuries in the area @minglana

#euskadi#euskal herria#basque country#pais vasco#pays basque#spain#history#ojocastro#huesca#opression#politics#anons

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Salvatore Pennacchio

Born: 7 September 1952, Marano, Italy

Physique: Average Build

Salvatore Pennacchio is a Catholic archbishop and diplomat of the Holy See. He received his priestly ordination on 18th September 1976 for the Diocese of Aversa. He served in the Apostolic Nunciatures in Panama, Ethiopia, Australia, Turkey, Egypt, Yugoslavia and Ireland. On 6th August 2016, H.E. Archbishop Salvatore Pennacchio was appointed by Pope Francis the Apostolic Nuncio to the Republic of Poland. Besides Italian, he speaks also English, French and Spanish.

I don't know anything else about him, other than I think he is handsome and I want to fuck him. Given his position, it's unlikely that we will ever get leaked sex tapes of him, but I can dream. And I do... A LOT!

#Salvatore Pennacchio#mydaddywiki religious figures#priest#mydaddywiki#archbishop#religious figures#clergy

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know there are only two contractions in Spanish but what about contracted abbreviations, words you wouldn't pronounce contracted but would write them that way? For example, "cont'd" for "continued"?

There are plenty of abbreviations in Spanish like BBAA (bellas artes = fine arts), or RRHH (recursos humanos = human resources/HR)

Others are like etc for etcétera, vs for versus

Or PD which is PS in letters - literally posdata or postdata for "postscript"

Some that I've seen are like núm. for número, pág. for página, vol. for volumen or p. ej. as por ejemplo

You may also see dcho/a for derecho/a "right", and izq. / izdo/a / izqdo/a for izquierdo/a for "left"

Two others to know:

a.e.c -> antes de la era común = "BCE" or "before the common era" or BC

e.c. -> era común = "common era" or "AD"

Really common are the abbreviations for ordinal numbers

1er -> primer = first

1ero/a -> primero/a = first

2do/a -> segundo/a = second

3er -> tercer = third

3ero/a -> tercero/a = third

4to/a -> cuarto/a = fourth

5to/a -> quinto/a = fifth

6to/a -> sexto/a = sixth

7mo/a -> séptimo/a = seventh

8vo/a -> octavo/a = eighth

9no/a -> noveno/a = ninth

10mo -> décimo/a = tenth

These are the equivalents of using 1st, 2nd, 3rd etc. in English. You'll also sometimes see symbols that are like a tiny floating O or A to depict gender, they'll look sort of like the symbol for degrees

Most commonly it's for terms of address like Vd. / vmd = Vuestra Merced [Your Worship/Lordship/Ladyship], though this is older Spanish

Ud. = Usted

Uds. = Ustedes

D. = Don = "Mr."

Dña. = Doña = Mrs.

Sr. = Señor = Mr.

Sra. = Señora = Mrs. / Ma'am

Srta. = Señorita = Miss

Dr. = Doctor

Dra. = Doctora = [female] Doctor

And you get some that are abbreviations that can become their own words like las mates is short for las matemáticas so las mates is "math" rather than "mathematics"... or profe is a common way to address teachers in a friendly way like "teach"

Other common ones you might see are the ones for countries like EEUU is los Estados Unidos or "United States", or sometimes la RD for la República Dominicana for "Dominican Republic" or P. Rico is Puerto Rico but there are lots of country abbreviations especially for mailing purposes

This is also not talking about terms of address for military

Abreviaturas | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (rae.es)

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

General Heart Fragment Headcanons (pt. 1)

Because it's still occupying my mind. Also spoilers for Book 1 and Book 2!!

Natalia is THAT girl. She takes care of herself. She has a full skincare routine she carries out every week.

She once offered Teryl one of those shiny, silver face masks

He accepted it. And then asked for another one. And another one.

Cue Clive entering the shack. Two long-haired men with silver faces greet him. He doesn’t remember much about what happened after that.

Shannon has some beef with some bigger bakery corporations (because she’s just BETTER.)

No joke, they sent her a cease and desist email to literally stop handing out free pastries (she made herself) because people stopped purchasing from their stores during that period of time

Jasper sometimes uses the nickname ‘Lia’ for Natalia

Xani is kind of fluent in Spanish

Gray has his own StarxSocial account that Xani helped set up

He doesn’t post a lot on there, he mainly uses it for keeping up with news and… pop culture - in order to try and connect with Xani because god knows what the youth of the time are interested in

From time to time, he will get logged out and will have to ask his daughter how to log back in

“Girl. What’s my password.”

“Sigh. It’s Learntowritedownyourpassword. And both of our birth years.”

“…doesn’t work.” “I didn’t mean it literally!!”

As a result of his mutation, Jasper actually has (retractable) wolf-like fangs! No, he’s not a vampire. No, he won’t bite you to suck your blood. (Although I’m sure a lot of you would loooove that)

Like the rest of his (presumed) powers, he refuses to use his fangs. Though, they may come out simultaneously when his eyes switch colour

Clive has the most horrendous experiences whenever a barista attempts to write his name on a cup

Sometimes he’ll just blurt out a random name that is nowhere close to his out of panic and when his coffee is completed he’ll just be sat there wondering

“Who’s Jonathan and why is he not collecting his coffee what a weirdo"

“……………….wait I’M Jonathan-“

Xani once witnessed Lana mix her own coffee by also dumping a whole energy drink into it

“I am going to die.” And then she chugged the whole thing

Shannon has gossip sessions with Kay.

They are genuinely both nice, caring and drama-free individuals but sometimes they'll hear about the stuff happening around them and be like, "omg we have to talk about this"

Lana may have fallen for her boyfriend first, but he fell way harder

She got Inigo hyperventilating, giggling, blushing and kicking his blankets!!!

His sketchbooks quickly fill up with images of her and her flowing blue hair (I swear I will draw these two prompts someday. SOMEDAY)

Natalia is quite OP at video games, despite initially not having much experience?

"Teryl, you hand me over that controller right now because I swear I will burst a vein if you spend 20 more seconds on this level struggling"

If the group ever go out in public together, she's in charge of co-ordinating their outfits if she is not satisfied because she knows her fashion 💅

But there will be times where she accidentally matches with Jasper??? Which is completely unintentional?

Natalia is forever a victim to Teryl

"is that my shirt." "sorry sweetie can't help the fact it looks better on me"

Her nails are sharp like a cat <3

#I did a lot of Natalia hcs for this one... guess she really is my fav HAHA#apologies for the lack of kay hcs </3 he will shine like a star in another part I promise#heart fragment#heart fragment headcanons#xani green#kay jamison#shannon lafae#heart fragment clive#lana kojima#natalia winterfeld#jasper finley

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

My church is about to make a huge blunder. They're really pushing hard on this Spanish Mass, which just makes no sense. This isn't a Latino neighborhood, they're not going to get Spanish speakers to come to this, and even if they did, the Spanish speakers are most likely Catholic and would feel tricked or deceived if they came to a Missa at a protestant church.

I proposed to do Evensong on Friday. When our church used to have daily mass, Friday evening was our most popular day. We can't have eucharist since we don't have a priest for it, but we could do evensong, which could be led by laity, and which is the most popular liturgy from the Anglican tradition. Even catholics say they love evensong and wish the catholic church did it. It would be a draw for all the people that miss the Friday mass, the surrounding anglicans who only get to go to evensong once a year, and maybe for catholics who want to attend an Anglican liturgy without the sacraments. They aren't interested in this at all. They want to do the Spanish mass.

But worse of all, the only "priest" they can find for the Spanish mass is a female priest. If they let a woman behind the altar, there go all the traditionalists in our church. In our 140 year history, a woman has never been behind our altar or touched any of sacramentals. Our niche in the area is that we are the one episcopal church that has never and will never accept woman's ordination. They're about to throw that niche away to bring in maybe 3 or 4 Hispanics that know nothing about the Church of England or its worldwide communion. They're gonna lose half the congregation over this.

And their attitude is "well, it's not like we're going to be attending it. We don't speak Spanish." They don't understand that it's not about whether we go to it or not, it's about us endorsing the concept, and us allowing the altar and sacramentals to be desecrated by somebody without proper holy orders.

Right now, Rome is opening the door to having full communion with Anglican churches, and what is the ONE singular requirement that they have demanded? No female priests. These people are so stupid, allowing themselves to shoot themselves in their feet like this in such a historic moment, when our church was an "Anglo-Papalist" church, that is, the movement that sought reconciliation with Rome and tried to become as catholic as possible within the Anglican confines.

And my girlfriend is gonna lose all respect for my church if they do this. I can't have that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

J.3.1 What are affinity groups?

Affinity groups are the basic organisation which anarchists create to spread the anarchist idea. The term “affinity group” comes from the Spanish F.A.I. (Iberian Anarchist Federation) and refers to the organisational form devised in their struggles for freedom (from “grupo de afinidad”). At its most basic, it is a (usually small) group of anarchists who work together to spread their ideas to the wider public, using propaganda, initiating or working with campaigns and spreading their ideas within popular organisations (such as unions) and communities. It aims not to be a “leadership” but to give a lead, to act as a catalyst within popular movements. Unsurprisingly it reflects basic anarchist ideas:

“Autonomous, communal and directly democratic, the group combines revolutionary theory with revolutionary lifestyle in its everyday behaviour. It creates a free space in which revolutionaries can remake themselves individually, and also as social beings.” [Murray Bookchin, Post-Scarcity Anarchism, p. 144]

The reason for this is simple, for a “movement that sought to promote a liberatory revolution had to develop liberatory and revolutionary forms. This meant … that it had to mirror the free society it was trying to achieve, not the repressive one it was trying to overthrow. If a movement sought to achieve a world united by solidarity and mutual aid, it had to be guided by these precepts; if it sought to achieve a decentralised, stateless, non-authoritarian society, it had to be structured in accordance with these goals.” [Bookchin, The Spanish Anarchists, p. 180]

The aim of an anarchist organisation is to promote a sense of community, of confidence in ones own abilities, to enable all to be involved in the identification, initiation and management of group needs, decisions and activities. They must ensure that individuals are in a position (both physically, as part of a group, and mentally, as an individual) to manage their own lives and take direct action in the pursuit of individual and communal needs and desires. Anarchist organisation is about empowering all, to develop “integral” or whole individuals and a community that encourages individuality (not abstract “individualism”) and solidarity. It is about collective decision making from the bottom up, that empowers those at the “base” of the structure and only delegates the work of co-ordinating and implementing the members decisions (and not the power of making decisions for people). In this way the initiative and power of the few (government) is replaced by the initiative and empowerment of all (anarchy). Affinity groups exist to achieve these aims and are structured to encourage them.

The local affinity group is the means by which anarchists co-ordinate their activities in a community, workplace, social movement and so on. Within these groups, anarchists discuss their ideas, politics and hopes, what they plan to do, organise propaganda work, discuss how they are going to work within wider organisations like unions, how their strategies fit into their long term plans and goals and so on. It is the basic way that anarchists work out their ideas, pull their resources and get their message across to others. There can be affinity groups for different interests and activities (for example a workplace affinity group, a community affinity group, an anarcha-feminist affinity group, etc., could all exist within the same area, with overlapping members). Moreover, as well as these more “political” activities, the “affinity group” also stresses the “importance of education and the need to live by Anarchist precepts — the need … to create a counter-society that could provide the space for people to begin to remake themselves.” [Bookchin, Op. Cit., p. 180] In other words, “affinity groups” aim to be the “living germs” of the new society in all aspects, not purely in a structurally way.

So affinity groups are self-managed, autonomous groupings of anarchists who unite and work on specific activities and interests. This means that ”[i]n an anarchist organisation the individual members can express any opinion and use any tactic which is not in contradiction with accepted principles and which does not harm the activities of others.” [Errico Malatesta, The Anarchist Revolution, p. 102] Such groups are a key way for anarchists to co-ordinate their activity and spread their message of individual freedom and voluntary co-operation. However, the description of what an “affinity group” is does not explain why anarchists organise in that way. Essentially, these affinity groups are the means by which anarchists actually intervene in social movements and struggles in order to win people to the anarchist idea and so help transform them from struggles against injustice into struggles for a free society. We will discuss the role these groups play in anarchist theory in section J.3.6.

These basic affinity groups are not seen as being enough in themselves. Most anarchists see the need for local groups to work together with others in a confederation. Such co-operation aims to pull resources and expand the options for the individuals and groups who are part of the federation. As with the basic affinity group, the anarchist federation is a self-managed organisation:

“Full autonomy, full independence and therefore full responsibility of individuals and groups; free accord between those who believe it is useful to unite in co-operating for a common aim; moral duty to see through commitments undertaken and to do nothing that would contradict the accepted programme. It is on these bases that the practical structures, and the right tools to give life to the organisation should be built and designed. Then the groups, the federations of groups, the federations of federations, the meetings, the congresses, the correspondence committees and so forth. But all this must be done freely, in such a way that the thought and initiative of individuals is not obstructed, and with the sole view of giving greater effect to efforts which, in isolation, would be either impossible or ineffective.” [Malatesta, Op. Cit., p. 101]

To aid in this process of propaganda, agitation, political discussion and development, anarchists organise federations of affinity groups. These take three main forms,

“synthesis” federations (see section J.3.2), “Platformist” federations (see section J.3.3 while section J.3.4 has criticism of this tendency) and “class struggle” groups (see section J.3.5). All the various types of federation are based on groups of anarchists organising themselves in a libertarian fashion. This is because anarchists try to live by the values of the future to the extent that this is possible under capitalism and try to develop organisations based upon mutual aid, in which control would be exercised from below upward, not downward from above. We must also note here that these types of federation are not mutually exclusive. Synthesis type federations often have “class struggle” and “Platformist” groups within them (although, as will become clear, Platformist federations do not have synthesis groups within them) and most countries have different federations representing the different perspectives within the movement. Moreover, it should also be noted that no federation will be a totally “pure” expression of each tendency. “Synthesis” groups merge into “class struggle” ones, Platformist groups do not subscribe totally to the Platform and so on. We isolate each tendency to show its essential features. In real life few, if any, federations will exactly fit the types we highlight. It would be more precise to speak of organisations which are descended from a given tendency, for example the French Anarchist Federation is mostly influenced by the synthesis tradition but it is not, strictly speaking, 100% synthesis. Lastly, we must also note that the term “class struggle” anarchist group in no way implies that “synthesis” and “Platformist” groups do not support the class struggle or take part in it, they most definitely do — it is simply a technical term to differentiate between types of organisation!

It must be stressed anarchists do not reduce the complex issue of political organisation and ideas into one organisation but instead recognise that different threads within anarchism will express themselves in different political organisations (and even within the same organisation). A diversity of anarchist groups and federations is a good sign and expresses the diversity of political and individual thought to be expected in a movement aiming for a society based upon freedom. All we aim to do is to paint a broad picture of the similarities and differences between the various perspectives on organising in the movement and indicate the role these federations play in libertarian theory, namely of an aid in the struggle, not a new leadership seeking power.

#affinity group#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

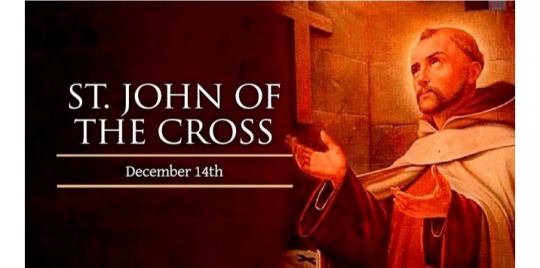

SAINT OF THE DAY (December 14)

December 14 is the liturgical memorial of Saint John of the Cross, a 16th-century Carmelite priest best known for reforming his order together with Saint Teresa of Avila and for writing the classic spiritual treatise “The Dark Night of the Soul.”

Honored as a Doctor of the Church since 1926, he is sometimes called the “Mystical Doctor,” as a tribute to the depth of his teaching on the soul's union with God.

The youngest child of parents in the silk-weaving trade, John de Yepes was born on 24 June 1542 in Fontiveros near the Spanish city of Avila.

His father Gonzalo died at a relatively young age, and his mother Catalina struggled to provide for the family.

John found academic success from his early years but failed in his effort to learn a trade as an apprentice.

He instead spent several years working in a hospital for the poor and continuing his studies at a Jesuit college in the town of Medina del Campo.

After discerning a calling to monastic life, John entered the Carmlite Order in 1563.

He had been practicing severe physical asceticism even before joining the Carmelites and got permission to live according to their original rule of life — which stressed solitude, silence, poverty, work, and contemplative prayer.

John received ordination as a priest in 1567 after studying in Salamanca but considered transferring to the more austere Carthusian order rather than remaining with the Carmelites.

Before he could take such a step, however, he met the Carmelite nun later canonized as Saint Teresa of Avila.

Born on 28 March 1515, Teresa had joined the order in 1535, regarding consecrated religious life as the most secure road to salvation.

Since that time, she had made remarkable spiritual progress. During the 1560s, she began a movement to return the Carmelites to the strict observance of their original way of life.

She convinced John not to leave the order but to work for its reform.

Changing his religious name from “John of St. Matthias” to “John of the Cross,” the priest began this work in November 1568, accompanied by two other men of the order with whom he shared a small and austere house.

For a time, John was in charge of the new recruits to the “Discalced Carmelites” — the name adopted by the reformed group, since they wore sandals rather than ordinary shoes as sign of poverty.

He also spent five years as the confessor at a monastery in Avila led by St. Teresa.

Their reforming movement grew quickly but also met with severe opposition that jeopardized its future during the 1570s.

Early in December 1577, during a dispute over John's assignment within the order, opponents of the strict observance seized and imprisoned him in a tiny cell.

His ordeal lasted nine months and included regular public floggings along with other harsh punishments.

Yet it was during this very period that he composed the poetry that would serve as the basis for his spiritual writings.

John managed to escape from prison in August 1578, after which he resumed the work of founding and directing Discalced Carmelite communities.

Over the course of a decade, he set out his spiritual teachings in works such as “The Ascent of Mount Carmel,” “The Spiritual Canticle” and “The Living Flame of Love” as well as “The Dark Night of the Soul.”

But intrigue within the order eventually cost him his leadership position, and his last years were marked by illness along with further mistreatment.

John of the Cross died in the early hours of 14 December 1591, nine years after St. Teresa of Avila's death in October 1582.

Suspicion, mistreatment, and humiliation had characterized much of his time in religious life, but these trials are understood as having brought him closer to God by breaking his dependence on the things of this world.

Accordingly, his writings stress the need to love God above all things — being held back by nothing, and likewise holding nothing back.

Only near the end of his life had St. John's monastic superior recognized his wisdom and holiness.

Though his reputation had suffered unjustly for years, this situation reversed soon after his death.

He was beatified by Pope Clement X on 25 January 1675. He was canonized by Pope Benedict XIII on 27 December 1726.

He was named a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI in 1926.

In a letter marking the 400th anniversary of St. John's death, Pope John Paul II — who had written a doctoral thesis on the saint's writings — recommended the study of the Spanish mystic, whom he called a “master in the faith and witness to the living God.”

John of the Cross was a great saint who was a reformer, a mystic, and one of the great Spanish poets.

He has inspired many other holy men and women to pursue God into the mysterious heights and depths of divine love.

5 notes

·

View notes