#Textbook Development Services

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

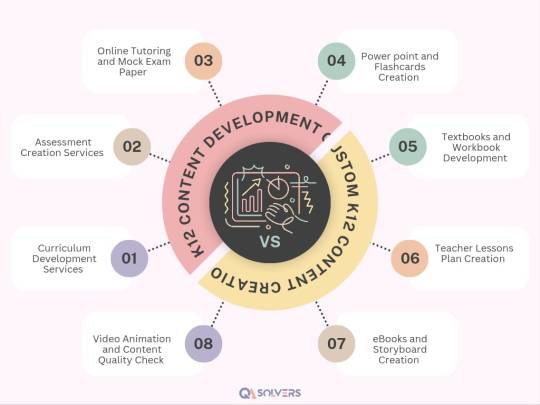

An Essential Guide to K12 Content Creation Services

K12 content creation services play a great role in creating educational materials for students from kindergarten through 12th grade. These services involve producing, managing, and distributing academic content to meet different learning needs. With the rise in digital and personalized education, especially after the pandemic, the demand for high-quality K12 content development has soared to…

View On WordPress

#academic content creation services#academic content development#Assessment Creation Services#Curriculum Development Services#eBook creation#k12 content creation services#k12 content development#k12 education#k12 educational solutions#k12 school#k12 students#online tutoring#Teacher Lesson Plans Services#Textbook Development Services

0 notes

Text

ok so i've been thinking about ffxiv housing. the in-universe explanation for the housing districts is that the city-states want to attract adventurers because they are a valuable demographics, in terms of spending power, social networks, and martial power. this makes sense, especially in the wake of the calamity; the states have all been considerably weakened and currying favor with (otherwise mercenary) powerful individuals in hopes of stimulating the economy and protecting their own citizenry and property is a rather sound prospect.

this makes even more sense for limsa lominsa in particular, considering merlwyb was the one behind costa del sol - the land being unfit for cultivation, she sold it to gegeruju who turned it into a luxury resort (and kicked out the locals who are now forced to resort to poaching! yay), and was behind the island sanctuary project. she wants to be an economic power using tourism as a means for colonization sooooo badly

it makes sense for ishgard, too - considerably weakened by their own war and isolationism, similarly unable to push for self-sufficiency (considering the environmental disaster that was the calamity for coerthas), they have (imo) correctly identified that one of their avenues for development lies in the brokering of trade agreements and tourism development (ishgard has a unique and strong cultural identity and beautiful vistas that make for a sound touristic opportunity).

it also makes sense for kugane to have a housing district - kugane being the only place that's open to foreigners, and catering quite extensively (not to mention expensively) to tourists' tastes, and being practically the only trade point between hingashi and the rest of the world.

that being said, the game itself acknowledges how unfair this system is, since unlocking access to every housing district involves you watching some poor local citizen's hopes of homeownership getting brutally dashed by the "foreigners/adventurers-only" policy. (except for ishgard, since there is another citizens-only housing district?)

that's very obviously a case of gentrification (textbook definition even). worse, the sprawling suburban hellscape, literal-gated-community-full-of-gaudy-mcmansions that is the housing district is an inefficient use of land + very resource-intensive + creates an entire domestic service economy (labor-intensive to maintain). in other words, the opposite of a community & incredibly alienating to the people living there!!

you CAN'T create this kind of dynamic in the crystarium (first of all there's no room and most importantly the entire concept is that they're a communist city). you can't recreate the kind of exploitative class dynamics they had in EULMORE in there!!!!! that makes no sense!!

now it would make sense in eulmore but the resource availability in the First is still limited, i would say, not to mention it would be an extremely scummy move lmao

as for sharlayan, the same applies; theyre not communist at all (lol) but they would not benefit from tourism or creating this kind of class at all, and anyway they already manage their (limited) (island) land scarily extensively and i don't see how or why or where a housing district could be located anyway (and can you imagine the paperwork??)

now obviously the actual option for a new housing district would be mare lamentorum. it was quite literally made for that. no idea if they will ever go through with it but it would make sense and be physically possible, i think

#i am a housing hater yes#i like playing house so my characters have an apartment of their own#but like. i refuse to own a house#lol

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do realize this is a real niche post but I cannot tell you how many damn times over the past 10 months I've seen gentiles tell Jews some version of, "Your own holy book SAYS God doesn't want you to have a country yet!"

And it's such an incredibly blatant and weirdly specific tell that they're not part of something that grew from progressive grassroots, but something based on right-wing astroturfing.

1. Staying in your own lane is a pretty huge progressive principle.

Telling people in another group that their deity said they couldn't do X is, I think, as far as you can get from your own lane.

2. It's also very clearly Not In Your Own Lane because I've never seen anyone actually be able to EITHER quote the passage they're thinking of, OR cite where it is.

It's purely, "I saw somebody else say this, and it seemed like it would make me win the debate I wasn't invited to."

3. It betrays a complete ignorance of Jewish culture and history.

Seriously? You don't know what you're referencing, its context, or even what it specifically says, but you're... coming to a community that reads and often discusses the entire Torah together each year, at weekly services... who have massive books holding generations of debate about it that it takes 7 years to read, at one page per day....

And saying, "YOUR book told you not to!"

I've been to services where we discussed just one word from the reading the whole time. The etymology. The connotations. The use of it in this passage versus in other passages.

And then there is the famous saying, "Ask two Jews, get three opinions." There is a culture of questioning and discussion and debate throughout Judaism.

You think maybe, in the decades and decades of public discussion about whether to buy land in Eretz Yisrael and move back there; whether it should keep being an individual thing, or keep shifting to intentional community projects; what the risks were; whether it should really be in Argentina or Canada or someplace instead; how this would be received by the Jews and gentiles already there, how to respect their boundaries, how to work with them before and during; and whether ending up with a fuckton of Jews in one place might not be exactly as dangerous for them as it had always been everywhere else....

You think NOBODY brought up anything scriptural? Nobody looked through the Torah, the Nevi'im, the Ketuvim, or the Talmud for any thoughts about any of this?? It took 200 years and some rando in the comments to blow everyone's minds???

4. It relies on an unspoken assumption that people can and should take very literal readings of religious texts and use them to control others.

And a sense of ownership and power over those texts, even without any accompanying knowledge about what they say.

It's kind of a supercessionist know-it-all vibe. It reads like, "I know what you should be doing. Because even if I'm not personally part of a fundamentalist branch of a related religion, the culture I'm rooted in is."

Bonus version I found when I was looking for an example. NOBODY should do this:

There are a lot of people who pull weird historical claims like "It SAYS Abraham came from Chaldea! That's Iraq!"

Like, first of all, a group is indigenous to a land if it arose as a people and culture there, before (not because of) colonization.

People aren't spontaneously spawning in groups, like "Boom! A new indigenous people just spawned!!"

People come from places. They go places. Sometimes, they gel as a new community and culture. Sometimes, they bop around for a while and eventually assimilate into another group.

Second: THE TORAH IS NOT A HISTORY TEXTBOOK OMFG.

It's an oral history, largely written centuries after the fact.

There is a TON of historical and archaeological research on when and where the Jewish culture originated, how it developed over time, etc. It's extremely well-established.

Nobody has to try to pull what they remember from Sunday school for this argument.

#jumblr#Jewish history#hamas propaganda and fundie Christian propaganda are a terrible mix#fuck hamas#depressing discourse#wall of words

625 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is a more put together post of my thought on Sunrise on the Reaping

SPOILERS BELOW THE CUT

I want to start this off by saying these are my opinions, and overall thoughts on the book. I do not want to argue in the comments or reblogs.

I've seen many say that SotR is a fan service; of course it is. People have been begging for Haymitch's games for years. HOWEVER- that is not a bad thing!!!

You can clearly tell the fan service elements with the inclusion of Mags, Wiress, Beete, Effie, Katniss's Parents, and even the Lucy Gray mentions. However they all play a part in Haymitch's story now and later on in Catching Fire and even The Mockingjay.

Mags and Wiress were added as the Mentors for 12 because we as readers already know about them. We see Mags first in Catching Fire when she volunteers for Anne, how she interacts lovingly with Katniss and ultimately sacrifices herself. We as an audience already trust her. So we don't find it strange when Haymitch seeks comfort in her. And it's at this point it's be 39 years since Mags won her games, and what is a good way to keep her spirit broken-not only training kids from your district to fail, but kids from other districts too.

The same applies to Wiress, we see her in CF, as someone who is already a little off their rocker. A victor who won her games in a not so significant, non-rememberable way. Exactly why she was chosen to mentor 12- the forgettable district.

Beete and his son Ampert were added heart-breaking inclusion and answers Katniss's question "do the victor's kids get reaped?" This is essential to the early seed of the rebellion. I was heartbroken at his inclusion in the story, but I see how it was necessary.

Overall, the addition of the past victors make it much more meaningful to us as an audience in CF when Katniss picks them as allies. We know what they mean to Haymitch, the narrative, and the overall rebellion development. And in the deleted scenes Plutarch switches the 75th Quarter Quell card. But it makes you wonder, was the 75th tributes rigged to ensure the rebellion? The fire was buring with Katniss and Peetas win, they had to strike while the iron was still hot.

The addition of Katniss's parents- Burdock and Asterid- is a welcomed one, especially seeing how it ties into the Lucy Gray to Katniss Everdeen related theory pipeline. Each of their bestfriends getting reaped, something Asterid then relives with her own daughter.

I've seen some backlash on this addition, the biggest complaint being "why didn't we know this in the original trilogy?"... Katniss was the textbook definition of an unreliable narrator. It's also entirely plausible that Haymitch distant himself from everyone- fearing their fates would turn out the same as his loved ones.

Haymitch also being the one to give Lorane Dove the poison is heartbreaking. Snow could've done numerous things to her, but in the end made Haymitch be the one to kill his love.

Suzanne Collins message is clear. You don't have to read between the lines to understand what she is saying in SotR. It's a warning, and one that is in your face.

It's a callout to leaders; past, present and future and a warning to leaders now and to come. Rebellions happen, they take time and failure, but they happen. And when they do no one is left unscathed.

Propaganda and Censorship are very heavy themes in this book and at times (IN MY OPINION) are overly done. I understand the importance of not censoring the truth and we see how easily the Capitol manipulates the truth of the games, something that all current governments are capable of. But it felt like every page I read had the words propaganda and censorship in it. But it got the message across.

All in all, I throughly enjoyed the book. I found it fansicating that Haymitch was the "original mockingjay" in a sense. It makes you wonder how many other tributes and their games were botched Rebellion attempts. Were Anne's or Johanna's also failed attempts? But we know that it took 25 years after Haymitch's games for the cycle to be broken. Victory is not won in a single day, it may take years but it will happen

#venus rambles#thg sotr#sotr#sotr spoilers#the hunger games#sunrise on the reaping spoilers#sunrise on the reaping#haymitch abernathy#katniss everdeen

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just asking how do you feel about smg34?

Prepare for a long rant lol bc oh boy do I have opinions on this.

I like the ship, don’t get me wrong, but they’re just really god damn boring for me. Not quite as boring as Melony x Axol but still very vanilla.

It’s just a typical enemies to lovers trope which is so overdone now. They aren’t even enemies anymore. Just frenemies. Let’s face it, they’re never going to be canon. Their relationship will forever be teased but I will be VERY surprised if the SMG4 team actually follow through with them. The moments are nice but it’s just fan service.

2023 was an amazing year for SMG34 and it showed a real development in their relationship with IGBP and Wotfi 2023. But honestly, outside of a few teases, I really don’t think we’re going to be getting any concrete development for them for a while.

Without development, they really are just textbook enemies to lovers and that trope just doesn’t interest me on its own. Especially when they’re past the enemies phase but not quite lovers. It feels like they’re just eternally stuck in this weird grey area that only exists for the sake of fan service and I just couldnt care less about that kind of stuff.

Especially when SMG34 fans absolutely loose their shit about them standing next to each other when they’re the two characters who have had the most development out of everyone! Like bro. The SMG4 team are just fucking with you lot and you eat it up every time until it becomes the whole focus of the entire show!

Like, a side character could appear that we haven’t seen in a year and I just see countless people complaining that “ohhh SMG3 wasn’t in this episode!” Or “Ohh why didn’t SMG34 interact!” But if they DO interact then everyone just completely brushes aside the side character to just fawn over the thing that has more content than anything else!

Oh and god forbid you say you ship SMG4 or SMG3 with someone else. This is mostly directed at the TikTok SMG4 community but bloody hell it’s so annoying.

“NOO SMG4 LOVES SMG3! NOT MARIO!!”

“*SMG3 comes in to steal SMG4 away from Peach*”

“Hmm but I like SMG34 :(“

LIKE STFU THIS ISNT ABOUT THEM! I posted a video dedicated to rarepairs bc I love rarepairs and want to bring more attention to them and I got way too many comments about SMG34 when they are by far the most popular ship in the fandom.

And don’t get me started on the Snowtrapped jokes.

Fuck. Ing. HELL CAN WE PLEASE GET A NEW JOKE?

“Ha ha they did the boombaya in an igloo”

“Snowtrapped 2.0 when??”

“They need to remake Snowtrapped.”

The obsession some fans have with that episode just bc SMG3 and SMG4 had sex in it is honestly just irritating at this point. There are so many good episodes about their relationship! To show their development! One joke every so often is fine but for some people it’s every other word out of their mouths and I’m just sick of it.

What if Mar4 shippers just started going:

“Haha Wotfi 2014!” Over and over again. Or some of the other episodes where they are insanely homosexual with one another. Bc I’m telling you, way too many people brush over the Mar4 tension in the earlier episodes.

In conclusion, SMG34 is that ship you start to ship when you first join a fandom bc it’s cute, there lots of content for it, and it makes sense. A lot of people hold onto that first ship but for me, I end up finding dynamics that interest me a lot more. Now, I only really interact with SMG34 content if one of my friends has made it bc I just struggle to get excited about it now.

If ever there’s a moment in an episode that’s cute, instead of enjoying it, all I can think about is how a scene of SMG3 and SMG4 standing next to eachother is going to completely destroy any actual conversation about the episode.

I don’t hate the ship. I do like it. But it’s just so basic.

I’ll take a rarepair over SMG34 any day.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog #3: Privilege and Nature Interpretation

Hi everyone,

Welcome to my third blog post!

This week's blog post will explore the role of privilege in nature interpretation. To begin, Privilege is defined as "a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group." There are two distinct categories of privilege.

The first refers to aspects of a person’s identity or circumstances that they are born into and cannot control. Examples of these include race, gender, socioeconomic status, and physical abilities. These factors often affect an individual's access to opportunities and experiences from the very beginning.

On the other hand, earned privileges are advantages that come from a person’s actions or achievements. This category includes education, skills, and professional accomplishments.

Unpacking My Invisible Backpack

My parents immigrated to Canada from Albania over 25 years ago in their late twenties, starting with almost nothing and speaking little English.

My dad, who graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Tirana, began his journey in Canada, delivering pizzas and working overnight shifts at a factory to support our family. They managed to save enough for a down payment on a house just four years after arriving. Eventually, my dad secured a job as a service engineer with CN Railway in Toronto, and my mom started working as hairstylist.

As highlighted in this week's readings, many individuals born into more privileged circumstances "are not taught to recognize their privileges" (Gallavan, 2005). This concept deeply resonates with my experience as the daughter of immigrant parents.

Growing up, I was aware of the sacrifices my parents made in order to provide me with a life full of opportunitiy they never had. I often observed that many of my peers unknowingly took their privileges for granted. For instance, stable financial support and access to higher education were the norm for some of my peers and their families. But for my family, these achievements required significant effort and dedication.

My parents first day in Canada, 1998

Privilege and Nature Interpretation

When it comes to nature interpretation, privilege plays a significant role. As stated in the textbook, "To effectively serve a related audience, you must know them" (Beck et al., 2018). Understanding the audience allows interpreters to tailor messages and experiences more effectively (Beck et al., 2018). This requires interpreters to appreciate the unique backgrounds and lived experiences of their audience.

The textbook outlines several barriers that have discouraged park attendance among minority populations (Beck et al., 2018).

Economic Barriers- Lack of personal vehicle or public transportation. Entrance fees, lodging, food etc.

Cultural barriers- Participation is based on cultural preferences related to history, values, etc.

Communication Barriers- Language barriers may prevent interpreters from serving diverse audiences.

Lack of Knowledge- Lack of awareness on where to go, what to do.

Fear- Fear of wildlife, getting lost, safety conerns.

By addressing these barriers, interpreters can create welcoming environments, allowing diverse individuals to develop a deeper appreciation for nature and what it has to offer.

Thanks for reading!

Biona🍀🌷🐬

References: Knudson, L.B.T.T.C.D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

Gallavan, N. P. (2005). Helping teachers unpack their "invisible knapsacks." Multicultural Education, 13 (1), 36. Gale Academic OneFile. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A137921591/AONE?u=guel77241&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=9fe2f151

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cyclonians Attitude Toward Literature: Favorite Books And Writers

Master Cyclonis

Since state affairs, military strategies, political negotiations and diplomatic missions occupy almost her entire daily routine, Cyclonis believes that reading novels is a waste of time that does not correspond to her majesty's high status. An exception can only be made if her advisor doesn't recommend something to relieve her stress. Thus, her interest in self-development is more focused on textbooks on military topography, political science, philosophy, psychology, crystal physics and biochemistry, which allows her to maintain the high level of intellectual development necessary to run an empire. But if she manages to find some free time, she devotes it entirely to immersing herself in the world of fiction, trying to increase the volume of gray matter with something that requires less effort to think. After reading several volumes of manga such as Claymore, Blood-C and Berserk, Cyclonis realized that her favorite subgenre is dark fantasy.

Dark Ace

When Dark Ace was young, he was fond of historical military melodramas, including the novel 'Gone with the Wind'. Because of his busy work schedule, he rarely makes time for reading, but when the opportunity arises, he always chooses from his list the book that he wanted to read the most. His current favorite is '1984', which clearly shows his passion for power, control, and human freedom. Dark Ace has a special respect for several authors, among whom stand out Machiavelli with his pragmatic approach to politics, Clausewitz with a deep analysis of military affairs and Vegetius with a detailed work on the art of war. Probably, he is also interested in the biographies of other famous military leaders of the last century, in order to thoroughly study their experience and avoid the same mistakes that led to their downfall. 'The Art of War' by Sun Tzu will become his reference book, and Hannibal Barca's strategic treatises will serve as an inspiration to follow his principles.

Ravess

In a rare moments of relaxation, when Ravess isn't rehearsing yet another sinister ensemble, she finds solace in a stack of tabloid novels that reflect her hidden need for romance, which she can't fulfill because of the constant preoccupation associated with her Empress's plans. Despite her unassuming taste in popular literature, Ravess is an extremely erudite commander whose versatile nature extends far beyond the world of lyrical symphonies. For a while, she even tried to learn the basics of classical haiku, but all her efforts were usually limited to small sketches that looked more like discordant snatches of melodies.

Snipe

Because of his multitasking on the service, Snipe has a below-average attention span, so he can't process any text for more than one minute. In any case, Snipe finds most of the books very boring, but he also finds a way to satisfy his interest in destruction through a variety of magazines devoted to the history of weapons and all things related to them. Despite his obvious dislike for reading, Snipe sees his find as a true source of information that he is willing to use to thoroughly analyze the enemy's defensive strategy. What he doesn't realize is that it's not always a good idea to trust magazines written by video game enthusiasts.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Myth of Barter

For every subtle and complicated question, there is a perfectly simple and straightforward answer, which is wrong. —H.L. Mencken

What is the difference between a mere obligation, a sense that one ought to behave in a certain way, or even that one owes something to someone, and a debt, properly speaking? The answer is simple: money. The difference between a debt and an obligation is that a debt can be precisely quantified. This requires money.

Not only is it money that makes debt possible: money and debt appear on the scene at exactly the same time. Some of the very first written documents that have come down to us are Mesopotamian tablets recording credits and debits, rations issued by temples, money owed for rent of temple lands, the value of each precisely specified in grain and silver. Some of the earliest works of moral philosophy, in turn, are reflections on what it means to imagine morality as debt—that is, in terms of money.

A history of debt, then, is thus necessarily a history of money—and the easiest way to understand the role that debt has played in human society is simply to follow the forms that money has taken, and the way money has been used, across the centuries—and the arguments that inevitably ensued about what all this means. Still, this is necessarily a very different history of money than we are used to. When economists speak of the origins of money, for example, debt is always something of an afterthought. First comes barter, then money; credit only develops later. Even if one consults books on the history of money in, say, France, India, or China, what one generally gets is a history of coinage, with barely any discussion of credit arrangements at all. For almost a century, anthropologists like me have been pointing out that there is something very wrong with this picture. The standard economic-history version has little to do with anything we observe when we examine how economic life is actually conducted, in real communities and marketplaces, almost anywhere—where one is much more likely to discover everyone in debt to everyone else in a dozen different ways, and that most transactions take place without the use of currency.

Why the discrepancy?

Some of it is just the nature of the evidence: coins are preserved in the archeological record; credit arrangements usually are not. Still, the problem runs deeper. The existence of credit and debt has always been something of a scandal for economists, since it’s almost impossible to pretend that those lending and borrowing money are acting on purely “economic” motivations (for instance, that a loan to a stranger is the same as a loan to one’s cousin); it seems important, therefore, to begin the story of money in an imaginary world from which credit and debt have been entirely erased. Before we can apply the tools of anthropology to reconstruct the real history of money, we need to understand what’s wrong with the conventional account.

Economists generally speak of three functions of money: medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value. All economic textbooks treat the first as primary. Here’s a fairly typical extract from Economics, by Case, Fair, Gärtner, and Heather (1996):

Money is vital to the working of a market economy. Imagine what life would be like without it. The alternative to a monetary economy is barter, people exchanging goods and services for other goods and services directly instead of exchanging via the medium of money.

How does a barter system work? Suppose you want croissants, eggs and orange juice for breakfast. Instead of going to the grocer’s and buying these things with money, you would have to find someone who has these items and is willing to trade them. You would also have to have something the baker, the orange juice purveyor and the egg vendor want. Having pencils to trade will do you no good if the baker and the orange juice and egg sellers do not want pencils.

A barter system requires a double coincidence of wants for trade to take place. That is, to effect a trade, I need not only have to find someone who has what I want, but that person must also want what I have. Where the range of traded goods is small, as it is in relatively unsophisticated economies, it is not difficult to find someone to trade with, and barter is often used.[16]

This latter point is questionable, but it’s phrased in so vague a way that it would be hard to disprove.

In a complex society with many goods, barter exchanges involve an intolerable amount of effort. Imagine trying to find people who offer for sale all the things you buy in a typical trip to the grocer’s, and who are willing to accept goods that you have to offer in exchange for their goods.

Some agreed-upon medium of exchange (or means of payment) neatly eliminates the double coincidence of wants problem.[17]

It’s important to emphasize that this is not presented as something that actually happened, but as a purely imaginary exercise. “To see that society benefits from a medium of exchange” write Begg, Fischer and Dornbuch (Economics, 2005), “imagine a barter economy.” “Imagine the difficulty you would have today,” write Maunder, Myers, Wall, and Miller (Economics Explained, 1991), “if you had to exchange your labor directly for the fruits of someone else’s labor.” “Imagine,” write Parkin and King (Economics, 1995), “you have roosters, but you want roses.”[18] One could multiply examples endlessly. Just about every economics textbook employed today sets out the problem the same way. Historically, they note, we know that there was a time when there was no money. What must it have been like? Well, let us imagine an economy something like today’s, except with no money. That would have been decidedly inconvenient! Surely, people must have invented money for the sake of efficiency.

The story of money for economists always begins with a fantasy world of barter. The problem is where to locate this fantasy in time and space: Are we talking about cave men, Pacific Islanders, the American frontier? One textbook, by economists Joseph Stiglitz and John Driffill, takes us to what appears to be an imaginary New England or Midwestern town:

One can imagine an old-style farmer bartering with the blacksmith, the tailor, the grocer, and the doctor in his small town. For simple barter to work, however, there must be a double coincidence of wants … Henry has potatoes and wants shoes, Joshua has an extra pair of shoes and wants potatoes. Bartering can make them both happier. But if Henry has firewood and Joshua does not need any of that, then bartering for Joshua’s shoes requires one or both of them to go searching for more people in the hope of making a multilateral exchange. Money provides a way to make multilateral exchange much simpler. Henry sells his firewood to someone else for money and uses the money to buy Joshua’s shoes.[19]

Again this is just a make-believe land much like the present, except with money somehow plucked away. As a result it makes no sense: Who in their right mind would set up a grocery in such a place? And how would they get supplies? But let’s leave that aside. There is a simple reason why everyone who writes an economics textbook feels they have to tell us the same story. For economists, it is in a very real sense the most important story ever told. It was by telling it, in the significant year of 1776, that Adam Smith, professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow, effectively brought the discipline of economics into being.

He did not make up the story entirely out of whole cloth. Already in 330 bc, Aristotle was speculating along vaguely similar lines in his treatise on politics. At first, he suggested, families must have produced everything they needed for themselves. Gradually, some would presumably have specialized, some growing corn, others making wine, swapping one for the other.[20] Money, Aristotle assumed, must have emerged from such a process. But, like the medieval schoolmen who occasionally repeated the story, Aristotle was never clear as to how.[21]

In the years after Columbus, as Spanish and Portuguese adventurers were scouring the world for new sources of gold and silver, these vague stories disappear. Certainly no one reported discovering a land of barter. Most sixteenth- and seventeenth-century travelers in the West Indies or Africa assumed that all societies would necessarily have their own forms of money, since all societies had governments and all governments issued money.[22]

Adam Smith, on the other hand, was determined to overturn the conventional wisdom of his day. Above all, he objected to the notion that money was a creation of government. In this, Smith was the intellectual heir of the Liberal tradition of philosophers like John Locke, who had argued that government begins in the need to protect private property and operated best when it tried to limit itself to that function. Smith expanded on the argument, insisting that property, money and markets not only existed before political institutions but were the very foundation of human society. It followed that insofar as government should play any role in monetary affairs, it should limit itself to guaranteeing the soundness of the currency. It was only by making such an argument that he could insist that economics is itself a field of human inquiry with its own principles and laws—that is, as distinct from, say ethics or politics.

Smith’s argument is worth laying out in detail because it is, as I say, the great founding myth of the discipline of economics.

What, he begins, is the basis of economic life, properly speaking? It is “a certain propensity in human nature … the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” Animals don’t do this. “Nobody,” Smith observes, “ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog.”[23] But humans, if left to their own devices, will inevitably begin swapping and comparing things. This is just what humans do. Even logic and conversation are really just forms of trading, and as in all things, humans will always try to seek their own best advantage, to seek the greatest profit they can from the exchange.[24]

It is this drive to exchange, in turn, which creates that division of labor responsible for all human achievement and civilization. Here the scene shifts to another one of those economists’ faraway fantasylands—it seems to be an amalgam of North American Indians and Central Asian pastoral nomads:[25]

In a tribe of hunters or shepherds a particular person makes bows and arrows, for example, with more readiness and dexterity than any other. He frequently exchanges them for cattle or for venison with his companions; and he finds at last that he can in this manner get more cattle and venison, than if he himself went to the field to catch them. From a regard to his own interest, therefore, the making of bows and arrows grows to be his chief business, and he becomes a sort of armourer. Another excels in making the frames and covers of their little huts or moveable houses. He is accustomed to be of use in this way to his neighbours, who reward him in the same manner with cattle and with venison, till at last he finds it his interest to dedicate himself entirely to this employment, and to become a sort of house-carpenter. In the same manner a third becomes a smith or a brazier; a fourth a tanner or dresser of hides or skins, the principal part of the clothing of savages …

It’s only once we have expert arrow-makers, wigwam-makers, and so on that people start realizing there’s a problem. Notice how, as in so many examples, we have a tendency to slip from imaginary savages to small-town shopkeepers.

But when the division of labor first began to take place, this power of exchanging must frequently have been very much clogged and embarrassed in its operations. One man, we shall suppose, has more of a certain commodity than he himself has occasion for, while another has less. The former consequently would be glad to dispose of, and the latter to purchase, a part of this superfluity. But if this latter should chance to have nothing that the former stands in need of, no exchange can be made between them. The butcher has more meat in his shop than he himself can consume, and the brewer and the baker would each of them be willing to purchase a part of it. But they have nothing to offer in exchange …

In order to avoid the inconveniency of such situations, every prudent man in every period of society, after the first establishment of the division of labor, must naturally have endeavored to manage his affairs in such a manner, as to have at all times by him, besides the peculiar produce of his own industry, a certain quantity of some one commodity or other, such as he imagined that few people would be likely to refuse in exchange for the produce of their industry.[26]

So everyone will inevitably start stockpiling something they figure that everyone else is likely to want. This has a paradoxical effect, because at a certain point, rather than making that commodity less valuable (since everyone already has some) it becomes more valuable (because it becomes, effectively, currency):

Salt is said to be the common instrument of commerce and exchanges in Abyssinia; a species of shells in some parts of the coast of India; dried cod at Newfoundland; tobacco in Virginia; sugar in some of our West India colonies; hides or dressed leather in some other countries; and there is at this day a village in Scotland where it is not uncommon, I am told, for a workman to carry nails instead of money to the baker’s shop or the ale-house.[27]

Eventually, of course, at least for long-distance trade, it all boils down to precious metals, since these are ideally suited to serve as currency, being durable, portable, and able to be endlessly subdivided into identical portions.

Different metals have been made use of by different nations for this purpose. Iron was the common instrument of commerce among the ancient Spartans; copper among the ancient Romans; and gold and silver among all rich and commercial nations.

Those metals seem originally to have been made use of for this purpose in rude bars, without any stamp or coinage …

The use of metals in this rude state was attended with two very considerable inconveniencies; first with the trouble of weighing; and, secondly, with that of assaying them. In the precious metals, where a small difference in the quantity makes a great difference in the value, even the business of weighing, with proper exactness, requires at least very accurate weights and scales. The weighing of gold in particular is an operation of some nicety …[28]

It’s easy to see where this is going. Using irregular metal ingots is easier than barter, but wouldn’t standardizing the units—say, stamping pieces of metal with uniform designations guaranteeing weight and fineness, in different denominations—make things easier still? Clearly it would, and so was coinage born. True, issuing coinage meant governments had to get involved, since they generally ran the mints; but in the standard version of the story, governments have only this one limited role—to guarantee the money supply—and tend to do it badly, since throughout history, unscrupulous kings have often cheated by debasing the coinage and causing inflation and other sorts of political havoc in what was originally a matter of simple economic common sense.

Tellingly, this story played a crucial role not only in founding the discipline of economics, but in the very idea that there was something called “the economy,” which operated by its own rules, separate from moral or political life, that economists could take as their field of study. “The economy” is where we indulge in our natural propensity to truck and barter. We are still trucking and bartering. We always will be. Money is simply the most efficient means.

Economists like Karl Menger and Stanley Jevons later improved on the details of the story, most of all by adding various mathematical equations to demonstrate that a random assortment of people with random desires could, in theory, produce not only a single commodity to use as money but a uniform price system. In the process, they also substituted all sorts of impressive technical vocabulary (i.e., “inconveniences” became “transaction costs”). The crucial thing, though, is that by now, this story has become simple common sense for most people. We teach it to children in schoolbooks and museums. Everybody knows it. “Once upon a time, there was barter. It was difficult. So people invented money. Then came the development of banking and credit.” It all forms a perfectly simple, straightforward progression, a process of increasing sophistication and abstraction that has carried humanity, logically and inexorably, from the Stone Age exchange of mastodon tusks to stock markets, hedge funds, and securitized derivatives.[29]

It really has become ubiquitous. Wherever we find money, we also find the story. At one point, in the town of Arivonimamo, in Madagascar, I had the privilege of interviewing a Kalanoro, a tiny ghostly creature that a local spirit medium claimed to keep hidden away in a chest in his home. The spirit belonged to the brother of a notorious local loan shark, a horrible woman named Nordine, and to be honest I was a bit reluctant to have anything to do with the family, but some of my friends insisted—since after all, this was a creature from ancient times. The creature spoke from behind a screen in an eerie, otherworldly quaver. But all it was really interested in talking about was money. Finally, slightly exasperated by the whole charade, I asked, “So, what did you use for money back in ancient times, when you were still alive?”

The mysterious voice immediately replied, “No. We didn’t use money. In ancient times we used to barter commodities directly, one for the other …”

The story, then, is everywhere. It is the founding myth of our system of economic relations. It is so deeply established in common sense, even in places like Madagascar, that most people on earth couldn’t imagine any other way that money possibly could have come about.

The problem is there’s no evidence that it ever happened, and an enormous amount of evidence suggesting that it did not.

For centuries now, explorers have been trying to find this fabled land of barter—none with success. Adam Smith set his story in aboriginal North America (others preferred Africa or the Pacific). In Smith’s time, at least it could be said that reliable information on Native American economic systems was unavailable in Scottish libraries. But by mid-century, Lewis Henry Morgan’s descriptions of the Six Nations of the Iroquois, among others, were widely published—and they made clear that the main economic institution among the Iroquois nations were longhouses where most goods were stockpiled and then allocated by women’s councils, and no one ever traded arrowheads for slabs of meat. Economists simply ignored this information.[30] Stanley Jevons, for example, who in 1871 wrote what has come to be considered the classic book on the origins of money, took his examples straight from Smith, with Indians swapping venison for elk and beaver hides, and made no use of actual descriptions of Indian life that made it clear that Smith had simply made this up. Around that same time, missionaries, adventurers, and colonial administrators were fanning out across the world, many bringing copies of Smith’s book with them, expecting to find the land of barter. None ever did. They discovered an almost endless variety of economic systems. But to this day, no one has been able to locate a part of the world where the ordinary mode of economic transaction between neighbors takes the form of “I’ll give you twenty chickens for that cow.”

The definitive anthropological work on barter, by Caroline Humphrey, of Cambridge, could not be more definitive in its conclusions: “No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing.”[31]

Now, all this hardly means that barter does not exist—or even that it’s never practiced by the sort of people that Smith would refer to as “savages.” It just means that it’s almost never employed, as Smith imagined, between fellow villagers. Ordinarily, it takes place between strangers, even enemies. Let us begin with the Nambikwara of Brazil. They would seem to fit all the criteria: they are a simple society without much in the way of division of labor, organized into small bands that traditionally numbered at best a hundred people each. Occasionally if one band spots the cooking fires of another in their vicinity, they will send emissaries to negotiate a meeting for purposes of trade. If the offer is accepted, they will first hide their women and children in the forest, then invite the men of other band to visit camp. Each band has a chief; once everyone has been assembled, each chief gives a formal speech praising the other party and belittling his own; everyone puts aside their weapons to sing and dance together—though the dance is one that mimics military confrontation. Then, individuals from each side approach each other to trade:

If an individual wants an object he extols it by saying how fine it is. If a man values an object and wants much in exchange for it, instead of saying that it is very valuable he says that it is no good, thus showing his desire to keep it. “This axe is no good, it is very old, it is very dull,” he will say, referring to his axe which the other wants.

This argument is carried on in an angry tone of voice until a settlement is reached. When agreement has been reached each snatches the object out of the other’s hand. If a man has bartered a necklace, instead of taking it off and handing it over, the other person must take it off with a show of force. Disputes, often leading to fights, occur when one party is a little premature and snatches the object before the other has finished arguing.[32]

The whole business concludes with a great feast at which the women reappear, but this too can lead to problems, since amidst the music and good cheer, there is ample opportunity for seductions.[33] This sometimes led to jealous quarrels. Occasionally, people would get killed.

Barter, then, for all the festive elements, was carried out between people who might otherwise be enemies and hovered about an inch away from outright warfare—and, if the ethnographer is to be believed—if one side later decided they had been taken advantage of, it could very easily lead to actual wars.

To shift our spotlight halfway around the world to Western Arnhem Land in Australia, where the Gunwinggu people are famous for entertaining neighbors in rituals of ceremonial barter called the dzamalag. Here the threat of actual violence seems much more distant. Partly, this is because things are made easier by the existence of a moiety system that embraces the whole region: no one is allowed to marry, or even have sex with, people of their own moiety, no matter where they come from, but anyone from the other is technically a potential match. Therefore, for a man, even in distant communities, half the women are strictly forbidden, half of them fair game. The region is also united by local specialization: each people has its own trade product to be bartered with the others.

What follows is from a description of a dzamalag held in the 1940s, as observed by an anthropologist named Ronald Berndt.

Once again, it begins as strangers, after some initial negotiations, are invited into the hosts’ main camp. The visitors in this particular example were famous for their “much-prized serrated spears”—their hosts had access to good European cloth. The trading begins when the visiting party, which consisted of both men and women, enters the camp’s dancing ground of “ring place,” and three of them began to entertain their hosts with music. Two men start singing, a third accompanies them on the didjeridu. Before long, women from the hosts’ side come and attack the musicians:

Men and women rise and begin to dance. The dzamalag opens when two Gunwinggu women of the opposite moiety to the singing men “give dzamalag” to the latter. They present each man with a piece of cloth, and hit or touch him, pulling him down on the ground, calling him a dzamalag husband, and joking with him in an erotic vein. Then another woman of the opposite moiety to the pipe player gives him cloth, hits and jokes with him.

This sets in motion the dzamalag exchange. Men from the visiting group sit quietly while women of the opposite moiety come over and give them cloth, hit them, and invite them to copulate; they take any liberty they choose with the men, amid amusement and applause, while the singing and dancing continue. Women try to undo the men’s loin coverings or touch their penises, and to drag them from the “ring place” for coitus. The men go with their dzamalag partners, with a show of reluctance, to copulate in the bushes away from the fires which light up the dancers. They may give the women tobacco or beads. When the women return, they give part of this tobacco to their own husbands, who have encouraged them to go dzamalag. The husbands, in turn, use the tobacco to pay their own female dzamalag partners …[34]

New singers and musicians appear, are again assaulted and dragged off to the bushes; men encourage their wives “not to be shy,” so as to maintain the Gunwinggu reputation for hospitality; eventually those men also take the initiative with the visitors’ wives, offering cloth, hitting them, and leading them off into the bushes. Beads and tobacco circulate. Finally, once participants have all paired off at least once, and the guests are satisfied with the cloth they have acquired, the women stop dancing and stand in two rows and the visitors line up to repay them.

Then visiting men of one moiety dance towards the women of the opposite moiety, in order to “give them dzamalag.” They hold shovel-nosed spears poised, pretending to spear the women, but instead hit them with the flat of the blade. “We will not spear you, for we have already speared you with our penises.” They present the spears to the women. Then visiting men of the other moiety go through the same actions with the women of their opposite moiety, giving them spears with serrated points. This terminates the ceremony, which is followed by a large distribution of food.[35]

This is a particularly dramatic case, but dramatic cases are revealing. What the Gunwinggu hosts appear to have been able to do here, owing to the relatively amicable relations between neighboring peoples in Western Arnhem Land, is to take all the elements in Nambikwara barter (the music and dancing, the potential hostility, the sexual intrigue), and turn it all into a kind of festive game—one not, perhaps, without its dangers, but (as the ethnographer emphasizes) considered enormous fun by everyone concerned.

What all such cases of trade through barter have in common is that they are meetings with strangers who will, likely as not, never meet again, and with whom one certainly will not enter into any ongoing relations. This is why a direct one-on-one exchange is appropriate: each side makes their trade and walks away. It’s all made possible by laying down an initial mantle of sociability, in the form of shared pleasures, music and dance—the usual base of conviviality on which trade must always be built. Then comes the actual trading, where both sides make a great display of the latent hostility that necessarily exists in any exchange of material goods between strangers—where neither party has no particular reason not to take advantage of the other—by playful mock aggression, though in the Nambikwara case, where the mantle of sociability is extremely thin, mock aggression is in constant danger of slipping over into the real thing. The Gunwinggu, with their more relaxed attitude toward sexuality, have quite ingeniously managed to make the shared pleasures and aggression into exactly the same thing.

Recall here the language of the economics textbooks: “Imagine a society without money.” “Imagine a barter economy.” One thing these examples make abundantly clear is just how limited the imaginative powers of most economists turn out to be.[36]

Why? The simplest answer would be: for there to even be a discipline called “economics,” a discipline that concerns itself first and foremost with how individuals seek the most advantageous arrangement for the exchange of shoes for potatoes, or cloth for spears, it must assume that the exchange of such goods need have nothing to do with war, passion, adventure, mystery, sex, or death. Economics assumes a division between different spheres of human behavior that, among people like the Gunwinngu and the Nambikwara, simply does not exist. These divisions in turn are made possible by very specific institutional arrangements: the existence of lawyers, prisons, and police, to ensure that even people who don’t like each other very much, who have no interest in developing any kind of ongoing relationship, but are simply interested in getting their hands on as much of the others’ possessions as possible, will nonetheless refrain from the most obvious expedient (theft). This in turn allows us to assume that life is neatly divided between the marketplace, where we do our shopping, and the “sphere of consumption,” where we concern ourselves with music, feasts, and seduction. In other words, the vision of the world that forms the basis of the economics textbooks, which Adam Smith played so large a part in promulgating, has by now become so much a part of our common sense that we find it hard to imagine any other possible arrangement.

From these examples, it begins to be clear why there are no societies based on barter. Such a society could only be one in which everybody was an inch away from everybody else’s throat; but nonetheless hovering there, poised to strike but never actually striking, forever. True, barter does sometimes occur between people who do not consider each other strangers, but they’re usually people who might as well be strangers—that is, who feel no sense of mutual responsibility or trust, or the desire to develop ongoing relations. The Pukhtun of Northern Pakistan, for instance, are famous for their open-handed hospitality. Barter is what you do with those to whom you are not bound by ties of hospitality (or kinship, or much of anything else):

A favorite mode of exchange among men is barter, or adal-badal (give and take). Men are always on the alert for the possibility of bartering one of their possessions for something better. Often the exchange is like for like: a radio for a radio, sunglasses for sunglasses, a watch for a watch. However, unlike objects can also be exchanged, such as, in one instance, a bicycle for two donkeys. Adal-badal is always practiced with non-relatives and affords men a great deal of pleasure as they attempt to get the advantage over their exchange partner. A good exchange, in which a man feels he has gotten the better of the deal, is cause for bragging and pride. If the exchange is bad, the recipient tries to renege on the deal or, failing that, to palm off the faulty object on someone unsuspecting. The best partner in adal-badal is someone who is distant spatially and will therefore have little opportunity to complain.[37]

Neither are such unscrupulous motives limited to Central Asia. They seem inherent to the very nature of barter—which would explain the fact that in the century or two before Smith’s time, the English words “truck and barter,” like their equivalents in French, Spanish, German, Dutch, and Portuguese, literally meant “to trick, bamboozle, or rip off.”[38] Swapping one thing directly for another while trying to get the best deal one can out of the transaction is, ordinarily, how one deals with people one doesn’t care about and doesn’t expect to see again. What reason is there not to try to take advantage of such a person? If, on the other hand, one cares enough about someone—a neighbor, a friend—to wish to deal with her fairly and honestly, one will inevitably also care about her enough to take her individual needs, desires, and situation into account. Even if you do swap one thing for another, you are likely to frame the matter as a gift.

To illustrate what I mean by this, let’s return to the economics textbooks and the problem of the “double coincidence of wants.” When we left Henry, he needed a pair of shoes, but all he had lying around were some potatoes. Joshua had an extra pair of shoes, but he didn’t really need potatoes. Since money has not yet been invented, they have a problem. What are they to do?

The first thing that should be clear by now is that we’d really have to know a bit more about Joshua and Henry. Who are they? Are they related? If so, how? They appear to live in a small community. Any two people who have been living their lives in the same small community will have some sort of complicated history with each other. Are they friends, rivals, allies, lovers, enemies, or several of these things at once?

The authors of the original example seem to assume two neighbors of roughly equal status, not closely related, but on friendly terms—that is, as close to neutral equality as one can get. Even so, this doesn’t say much. For example, if Henry was living in a Seneca longhouse, and needed shoes, Joshua would not even enter into it; he’d simply mention it to his wife, who’d bring up the matter with the other matrons, fetch materials from the longhouse’s collective storehouse, and sew him some. Alternately, to find a scenario fit for an imaginary economics textbook, we might place Joshua and Henry together in a small, intimate community like a Nambikwara or Gunwinggu band.

SCENARIO 1

Henry walks up to Joshua and says “Nice shoes!”

Joshua says, “Oh, they’re not much, but since you seem to like them, by all means take them.”

Henry takes the shoes.

Henry’s potatoes are not at issue since both parties are perfectly well aware that if Joshua were ever short of potatoes, Henry would give him some.

And that’s about it. Of course it’s not clear, in this case, how long Henry will actually get to keep the shoes. It probably depends on how nice they are. If they were just ordinary shoes, this might be the end of the matter. If they are in any way unique or beautiful, they might end up being passed around. There’s a famous story that John and Lorna Marshall, who carried out a study of Kalahari Bushmen in the ’60s, once gave a knife to one of their favorite informants. They left and came back a year later, only to discover that pretty much everyone in the band had been in possession of the knife at some point in between. On the other hand, several Arab friends confirm to me that in less strictly egalitarian contexts, there is an expedient. If a friend praises a bracelet or bag, you are normally expected to immediately say “take it”—but if you are really determined to hold on to it, you can always say, “yes, isn’t it beautiful? It was a gift.”

But clearly, the authors of the textbook have a slightly more impersonal transaction in mind. The authors seem to imagine the two men as the heads of patriarchal households, on good terms with each other, but who keep their own supplies. Perhaps they live in one of those Scottish villages with the butcher and the baker in Adam Smith’s examples, or a colonial settlement in New England. Except for some reason they’ve never heard of money. It’s a peculiar fantasy, but let’s see what we can do:

SCENARIO 2

Henry walks up to Joshua and says, “Nice shoes!”

Or, perhaps—let’s make this a bit more realistic—Henry’s wife is chatting with Joshua’s and strategically lets slip that the state of Henry’s shoes is getting so bad he’s complaining about corns.

The message is conveyed, and Joshua comes by the next day to offer his extra pair to Henry as a present, insisting that this is just a neighborly gesture. He would certainly never want anything in return.

It doesn’t matter whether Joshua is sincere in saying this. By doing so, Joshua thereby registers a credit. Henry owes him one.

How might Henry pay Joshua back? There are endless possibilities. Perhaps Joshua really does want potatoes. Henry waits a discrete interval and drops them off, insisting that this too is just a gift. Or Joshua doesn’t need potatoes now but Henry waits until he does. Or maybe a year later, Joshua is planning a banquet, so he comes strolling by Henry’s barnyard and says “Nice pig …”

In any of these scenarios, the problem of “double coincidence of wants,” so endlessly invoked in the economics textbooks, simply disappears. Henry might not have something Joshua wants right now. But if the two are neighbors, it’s obviously only a matter of time before he will.[39]

This in turn means that the need to stockpile commonly acceptable items in the way that Smith suggested disappears as well. With it goes the need to develop currency. As with so many actual small communities, everyone simply keeps track of who owes what to whom.

There is just one major conceptual problem here—one the attentive reader might have noticed. Henry “owes Joshua one.” One what? How do you quantify a favor? On what basis do you say that this many potatoes, or this big a pig, seems more or less equivalent to a pair of shoes? Because even if these things remain rough-and-ready approximations, there must be some way to establish that X is roughly equivalent to Y, or slightly worse or slightly better. Doesn’t this imply that something like money, at least in the sense of a unit of accounts by which one can compare the value of different objects, already has to exist?

In most gift economies, there actually is a rough-and-ready way to solve the problem. One establishes a series of ranked categories of types of thing. Pigs and shoes may be considered objects of roughly equivalent status, one can give one in return for the other; coral necklaces are quite another matter, one would have to give back another necklace, or at least another piece of jewelry—anthropologists are used to referring to these as creating different “spheres of exchange.”[40] This does simplify things somewhat. When cross-cultural barter becomes a regular and unexceptional thing, it tends to operate according to similar principles: there are only certain things traded for certain others (cloth for spears, for example), which makes it easy to work out traditional equivalences. However, this doesn’t help us at all with the problem of the origin of money. Actually, it makes it infinitely worse. Why stockpile salt or gold or fish if they can only be exchanged for some things and not others?

In fact, there is good reason to believe that barter is not a particularly ancient phenomenon at all, but has only really become widespread in modern times. Certainly in most of the cases we know about, it takes place between people who are familiar with the use of money, but for one reason or another, don’t have a lot of it around. Elaborate barter systems often crop up in the wake of the collapse of national economies: most recently in Russia in the ’90s, and in Argentina around 2002, when rubles in the first case, and dollars in the second, effectively disappeared.[41] Occasionally one can even find some kind of currency beginning to develop: for instance, in POW camps and many prisons, inmates have indeed been known to use cigarettes as a kind of currency, much to the delight and excitement of professional economists.[42] But here too we are talking about people who grew up using money and now have to make do without it—exactly the situation “imagined” by the economics textbooks with which I began.

The more frequent solution is to adopt some sort of credit system. When much of Europe “reverted to barter” after the collapse of the Roman Empire, and then again after the Carolingian Empire likewise fell apart, this seems to be what happened. People continued keeping accounts in the old imperial currency, even if they were no longer using coins.[43] Similarly, the Pukhtun men who like to swap bicycles for donkeys are hardly unfamiliar with the use of money. Money has existed in that part of the world for thousands of years. They just prefer direct exchange between equals—in this case, because they consider it more manly.[44]

The most remarkable thing is that even in Adam Smith’s examples of fish and nails and tobacco being used as money, the same sort of thing was happening. In the years following the appearance of The Wealth of Nations, scholars checked into most of those examples and discovered that in just about every case, the people involved were quite familiar with the use of money, and in fact, were using money—as a unit of account.[45] Take the example of dried cod, supposedly used as money in Newfoundland. As the British diplomat A. Mitchell-Innes pointed out almost a century ago, what Smith describes was really an illusion, created by a simple credit arrangement:

In the early days of the Newfoundland fishing industry, there was no permanent European population; the fishers went there for the fishing season only, and those who were not fishers were traders who bought the dried fish and sold to the fishers their daily supplies. The latter sold their catch to the traders at the market price in pounds, shillings and pence, and obtained in return a credit on their books, with which they paid for their supplies. Balances due by the traders were paid for by drafts on England or France.[46]

It was quite the same in the Scottish village. It’s not as if anyone actually walked into the local pub, plunked down a roofing nail, and asked for a pint of beer. Employers in Smith’s day often lacked coin to pay their workers; wages could be delayed by a year or more; in the meantime, it was considered acceptable for employees to carry off either some of their own products or leftover work materials, lumber, fabric, cord, and so on. The nails were de facto interest on what their employers owed them. So they went to the pub, ran up a tab, and when occasion permitted, brought in a bag of nails to charge off against the debt. The law making tobacco legal tender in Virginia seems to have been an attempt by planters to oblige local merchants to accept their products as a credit around harvest time. In effect, the law forced all merchants in Virginia to become middlemen in the tobacco business, whether they liked it or not; just as all West Indian merchants were obliged to become sugar dealers, since that’s what all their wealthier customers brought in to write off against their debt.

The primary examples, then, were ones in which people were improvising credit systems, because actual money—gold and silver coinage—was in short supply. But the most shocking blow to the conventional version of economic history came with the translation, first of Egyptian hieroglyphics, and then of Mesopotamian cuneiform, which pushed back scholars’ knowledge of written history almost three millennia, from the time of Homer (circa 800 bc), where it had hovered in Smith’s time, to roughly 3500 bc. What these texts revealed was that credit systems of exactly this sort actually preceded the invention of coinage by thousands of years.

The Mesopotamian system is the best-documented, more so than that of Pharaonic Egypt (which appears similar), Shang China (about which we know little), or the Indus Valley civilization (about which we know nothing at all). As it happens, we know a great deal about Mesopotamia, since the vast majority of cuneiform documents were financial in nature.

The Sumerian economy was dominated by vast temple and palace complexes. These were often staffed by thousands: priests and officials, craftspeople who worked in their industrial workshops, farmers and shepherds who worked their considerable estates. Even though ancient Sumer was usually divided into a large number of independent city-states, by the time the curtain goes up on Mesopotamian civilization around 3500, temple administrators already appear to have developed a single, uniform system of accountancy—one that is in some ways still with us, actually, because it’s to the Sumerians that we owe such things as the dozen or the 24-hour day.[47] The basic monetary unit was the silver shekel. One shekel’s weight in silver was established as the equivalent of one gur, or bushel of barley. A shekel was subdivided into 60 minas, corresponding to one portion of barley—on the principle that there were 30 days in a month, and Temple workers received two rations of barley every day. It’s easy to see that “money” in this sense is in no way the product of commercial transactions. It was actually created by bureaucrats in order to keep track of resources and move things back and forth between departments.

Temple bureaucrats used the system to calculate debts (rents, fees, loans …) in silver. Silver was, effectively, money. And it did indeed circulate in the form of unworked chunks, “rude bars” as Smith had put it.[48] In this he was right. But it was almost the only part of his account that was right. One reason was that silver did not circulate very much. Most of it just sat around in Temple and Palace treasuries, some of which remained, carefully guarded, in the same place for literally thousands of years. It would have been easy enough to standardize the ingots, stamp them, create some authoritative system to guarantee their purity. The technology existed. Yet no one saw any particular need to do so. One reason was that while debts were calculated in silver, they did not have to be paid in silver—in fact, they could be paid in more or less anything one had around. Peasants who owed money to the Temple or Palace, or to some Temple or Palace official, seem to have settled their debts mostly in barley, which is why fixing the ratio of silver to barley was so important. But it was perfectly acceptable to show up with goats, or furniture, or lapis lazuli. Temples and Palaces were huge industrial operations—they could find a use for almost anything.[49]

In the marketplaces that cropped up in Mesopotamian cities, prices were also calculated in silver, and the prices of commodities that weren’t entirely controlled by the Temples and Palaces would tend to fluctuate according to supply and demand. But even here, such evidence as we have suggests that most transactions were based on credit. Merchants (who sometimes worked for the Temples, sometimes operated independently) were among the few people who did, often, actually use silver in transactions; but even they mostly did much of their dealings on credit, and ordinary people buying beer from “ale women,” or local innkeepers, once again, did so by running up a tab, to be settled at harvest time in barley or anything they might have had at hand.[50]

At this point, just about every aspect of the conventional story of the origins of money lay in rubble. Rarely has an historical theory been so absolutely and systematically refuted. By the early decades of the twentieth century, all the pieces were in place to completely rewrite the history of money. The groundwork was laid by Mitchell-Innes—the same one I’ve already cited on the matter of the cod—in two essays that appeared in New York’s Banking Law Journal in 1913 and 1914. In these, Mitchell-Innes matter-of-factly laid out the false assumptions on which existing economic history was based and suggested that what was really needed was a history of debt:

One of the popular fallacies in connection with commerce is that in modern days a money-saving device has been introduced called credit and that, before this device was known, all, purchases were paid for in cash, in other words in coins. A careful investigation shows that the precise reverse is true. In olden days coins played a far smaller part in commerce than they do to-day. Indeed so small was the quantity of coins, that they did not even suffice for the needs of the [Medieval English] Royal household and estates which regularly used tokens of various kinds for the purpose of making small payments. So unimportant indeed was the coinage that sometimes Kings did not hesitate to call it all in for re-minting and re-issue and still commerce went on just the same.[51]

In fact, our standard account of monetary history is precisely backwards. We did not begin with barter, discover money, and then eventually develop credit systems. It happened precisely the other way around. What we now call virtual money came first. Coins came much later, and their use spread only unevenly, never completely replacing credit systems. Barter, in turn, appears to be largely a kind of accidental byproduct of the use of coinage or paper money: historically, it has mainly been what people who are used to cash transactions do when for one reason or another they have no access to currency.

The curious thing is that it never happened. This new history was never written. It’s not that any economist has ever refuted Mitchell-Innes. They just ignored him. Textbooks did not change their story—even if all the evidence made clear that the story was simply wrong. People still write histories of money that are actually histories of coinage, on the assumption that in the past, these were necessarily the same thing; periods when coinage largely vanished are still described as times when the economy “reverted to barter,” as if the meaning of this phrase is self-evident, even though no one actually knows what it means. As a result we have next-to-no idea how, say, the inhabitant of a Dutch town in 950 ad actually went about acquiring cheese or spoons or hiring musicians to play at his daughter’s wedding—let alone how any of this was likely to be arranged in Pemba or Samarkand.[52]

#debt#economics#money#capitalism#anti capitalism#slavery#wage labor#Wage Slavery#history#study#studies#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌍 Attention International Relations Students in Switzerland! 🇨🇭

Looking for the best resources to support your studies in International Relations? From textbooks, study guides, and reference materials to the latest in global affairs tools, we have everything you need to succeed in your academic journey and future career in international diplomacy, policy-making, and global affairs.

🌐 Whether you're preparing for exams, writing essays, or just keeping up with the latest international developments, our essential shopping items are tailored to meet your needs.

🛒 Start shopping now and take your studies to the next level! 👇 Visit: https://cotxapi.com/assignment/?token=token_67cde3ca444637.11755137#products

#InternationalRelations#IRStudents#GlobalStudies#InternationalDiplomacy#GlobalAffairs#PoliticalScience#StudyAbroad#SwissStudents#InternationalPolitics#GlobalPolicy#InternationalLaw#InternationalRelationsBooks#StudyMaterials#IRBooks#InternationalRelationsSuccess#GlobalStudiesSuccess#SwissAcademia#WorldPolitics#Diplomacy#PoliticalScienceStudents#GlobalEconomics#ForeignAffairs#IRCareer#GlobalNetworking#InternationalRelationsResearch#DiplomaticSkills#UNStudies#IRExams#InternationalRelationsTextbooks#StudySmart

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Role of Privilege in Nature Interpretation

My privilege in nature has not always been something that I have been aware of. I feel that an awareness of my privilege began developing as I was a teenager, and my friendships evolved into deeper relationships where we shared our thoughts, feelings and life experiences. It was during this time that I became aware of how lucky I was to have been born into a family that has roots in the backcountry and valued outdoor experiences. I’m privileged to be white and middle class and to have moved around throughout my childhood, these things have exposed me to an array of outdoors experiences in many different places, which I never even considered my peers may not have had access to.

The story that began the textbook chapter made me think of my own experience with recognizing how privileged I am to have had so many experiences in nature; the story tells of a Boys & Girls club program where kids were given a chance to have excursions in nature. It was mentioned that despite living just a few miles from the coast, many of the kids had never seen the ocean before due to accessibility barriers. I’m sure this has been the case in all the different communities that I’ve grown up in at different points of my life; although I have fond memories of exploring new wild spaces in each place that I’ve lived, many kids that I was friends with likely had lived there their entire life and didn’t have the same experience as I did.

One common barrier to nature for communities that have not grown up surrounded by it is the real and perceived risk that comes with outdoor excursions. Some outdoor experiences have more inherent risk than others; the tragedy on the Timiskaming was an excursion with far more inherent risk than the average family’s trip to the trails, however to someone that has never left the city, the perceived risk is still likely huge! A way to alleviate this perceived risk is through effective interpretation, offering services where someone can be with a knowledgeable person while experiencing nature for the first time is valuable and can help reduce the anxiety of the visitor.