#Turtle Coprolite

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Turtle Coprolite Fossil - Eocene - Madagascar - Genuine Prehistoric Specimen + COA

For sale is an authentic Turtle Coprolite fossil from the Eocene Epoch, discovered in Madagascar. This well-preserved specimen represents the fossilized excrement of an ancient turtle, offering a fascinating glimpse into the diet and ecosystem of prehistoric reptiles that lived approximately 56 to 33.9 million years ago.

Geology & Fossil Type:

Coprolites are trace fossils, meaning they preserve evidence of ancient life rather than the organism itself. This Turtle Coprolite was formed when prehistoric turtles excreted waste that became mineralized over millions of years, preserving its shape and internal composition. These fossils are scientifically significant as they provide insights into the feeding habits and digestive systems of ancient reptiles.

The Eocene Epoch was a time of significant evolution for many reptilian species, and Madagascar was home to a diverse array of wildlife, including ancient turtles. This fossil provides a direct connection to these prehistoric ecosystems, making it a valuable and rare paleontological specimen.

Fossil Details:

100% Genuine Fossil – No Replicas or Synthetics

Comes with a Certificate of Authenticity

From the Alice Purnell Collection, a highly regarded fossil collection

Scale cube = 1cm for size reference (please see photos for full dimensions)

You will receive the exact specimen shown in the listing

This rare Turtle Coprolite fossil is an exceptional addition to any fossil collection, educational display, or natural history collection. It is a unique and conversation-worthy specimen, perfect for collectors, educators, and paleontology enthusiasts alike.

Shop with confidence! We specialize in authentic fossils and minerals, ensuring each piece is carefully selected and properly identified. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out!

Fast & Secure Shipping Available Worldwide.

#Turtle Coprolite#Fossilized Turtle Dung#Eocene Fossil#Madagascar Fossil#Prehistoric Coprolite#Fossilized Poop#Authentic Fossil#Fossilized Turtle Waste#Natural History Collectible#Certified Fossil#Ancient Reptile Coprolite#Fossilized Digestive Remains#Paleontology Specimen#Fossil Enthusiast Gift#Unique Fossil

0 notes

Text

Round 2.5 - Platyhelminthes - Cestoda

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Cestoda is a class of flatworms, the most famous of which is the subclass Eucestoda, commonly referred to as “tapeworms.” The other subclass is Cestodaria, which are mainly parasites of fish and turtles.

Cestodes are parasites with complex life histories, including a stage in a definitive (main) host in which the adults grow and reproduce, often for years, and one or two intermediate stages in which the larvae develop in other hosts. Typically the adults live in the digestive tracts of vertebrates, while the larvae often live in the bodies of other animals, either vertebrates or invertebrates. Once the intermediate host is consumed by a definitive host, the cestode undergoes metamorphosis. Some cestodes are host-specific, while others are parasites of a wide variety of hosts. Some six thousand species have been described; possibly all vertebrates can host at least one species.

Tapeworms are ribbon-like as adults, with a unique body consisting of many similar units known as proglottids: essentially packets of eggs which are regularly shed into the environment to infect other organisms. They anchor themselves to the inside of the intestine of their host using their head, or scolex, which typically has hooks, suckers, or both. They have no mouth, but absorb nutrients directly from the host's gut. Cestodes are unable to synthesise lipids, which they use for reproduction, and are therefore entirely dependent on their hosts. Their neck continually produces proglottids, each one containing a reproductive tract. Mature proglottids are full of eggs, and fall off to leave the host, either passively in the feces or actively moving. Meanwhile, members of the subclass Cestodaria, the Amphilinidea and Gyrocotylidea, are wormlike but not divided into proglottids. Amphilinids have a muscular proboscis at the front end, while Gyrocotylids have a sucker or proboscis which they can pull inside or push outside at the front end, and a holdfast rosette at the posterior end. The Cestodaria have 10 larval hooks while Eucestoda have 6 larval hooks. All cestodes are hermaphrodites, with each individual having both male and female reproductive organs.

Parasite fossils are hard to come by, but recognizable clusters of cestode eggs, some with an operculum (lid) indicating that they had not hatched, one even with a developing larva, have been discovered in fossil shark coprolites dating to the Permian, some 270 million years ago. Also, the ribbon-shaped stem-Platyhelminthe Rugosusivitta orthogonia shares similarities with present-day Cestodians, and dates even further back, to the Cambrian.

Propaganda under the cut:

Humans are subject to infection by several species of tapeworms if they eat undercooked meat such as pork (Taenia solium), beef (Taenia saginata), and fish (Diphyllobothrium), or if they live in or eat food prepared in conditions of poor hygiene (Hymenolepis or Echinococcus species). We discovered fire for a reason, y’all.

T. saginata, the Beef Tapeworm, can grow up to 20 m (65 ft) long

The largest cestode is the Whale Tapeworm (Tetragonoporus calyptocephalus), which can grow to over 30 m (100 ft) long!

Meanwhile, tapeworms with small hosts tend to be small. For example, Vole and Lemming Tapeworms are only 13–240 mm (0.5–9.4 in) in length, and those parasitizing Shrews only 0.8–60 mm (0.03–2.36 in) long.

The unproven concept of using tapeworms as a slimming aid has been touted since the 1900s. Yeah, humans are so obsessed with conforming to a certain shape that sometimes they’ll put worms in their body about it.

#again I’m sorry if the gif is Problematic™ it’s just what came up when I searched tapeworm in the gifs and I thought it was funny#idk where it’s from#platyhelminthes#round 2.5#animal polls#parasites#human parasites

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Museum came to my school for an exhibition

They brought geological models, rocks, minerals, fossils, historical objects like silver spoons, helmets from the invasion and a bunch of cool stuff (a coprolite, a stegosaurus bone, extinct turtle shells, etc)

0 notes

Text

Taylor & Francis publications 27th July 2023- 1st August 2023

There have been a lot of interesting documents released between 27th July-1st August on the Taylor & Francis website; i decided to include the released papers' doi here.

Feel free to read them if you are interested, i have marked the papers available free to read and the others that require payment. (open access = Blue, payment required = red)

Copy the doi link or title into your search engine and you should be brought to the document.

A new amphibamiform (Temnospondyli: Branchiosauridae) from the lower Permian of the Czech Boskovice Basin

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2231994

A fossil viper (Serpentes: Viperidae) from the Early Pleistocene of the Crimean Peninsula

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241059

Unusual cystoporate? bryozoan from the Upper Ordovician of Siljan District, Dalarna, central Sweden

doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2023.2223579

Early Devonian Ostracoda from the Norton Gully Sandstone, southeastern Australia

doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2023.2223658

Eocene Araucariaceae in Europe: additional evidence from a new Baltic amber species of the genus Oxycraspedus Kuschel, 1955 (Coleoptera: Belidae)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237984

Skeletal taphonomy of the water frogs (Amphibia: Anura) from the Pit 7/8 of the Pliocene Camp dels Ninots site (Caldes de Malavella, NE Spain)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237998

Tapejarine pterosaur from the late Albian Paw Paw Formation of Texas, USA, with extensive feeding traces of multiple scavengers

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241044

The first American occurrence of Phoenicopteridae fossil egg and its palaeobiogeographical and palaeoenvironmental implications

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241050

Eocene (Ypresian-Lutetian) mammals from Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Gaiman, Chubut Province, Argentina)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241054

Turtle tracks from the middle Jurassic Yaopo formation in Beijing, China

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241064

The earliest occurrence of Equus in South Asia

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2227236

Early Cretaceous radiation of teleosts recorded by the otolith-based ichthyofauna from the Valanginian of Wąwał, central Poland

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2232008

A stem therian mammal from the Lower Cretaceous of Germany

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2224848

Vertebrate ichnology and palaeoenvironmental associations of Alaska’s largest known dinosaur tracksite in the Cretaceous Cantwell Formation (Maastrichtian) of Denali National Park and Preserve

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2221267

Biostratigraphical and paleoenvironmental studies of some Miocene‒Pliocene successions in Northwestern Nile Delta, Egypt

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2231978

Hyena and ‘false’ sabre-toothed cat coprolites from the late Middle Miocene of south-eastern Austria

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237979

Source:

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wednesday 13/10/21 - Dinosaurs of the World Part 4; Madagascar and India

Majungasaurus grabs the tail of a Madagascan crocodilian, Mahajungasuchus; Sergey Krasovskiy

When you think of our current geography, it makes sense to think of Madagascar as part of Africa's greater biosphere; a lot of biota found there now have relatives on the African mainland. The same for India, even more so because the Indian continental plate has made landfall on the Asian Mainland. But in the Mesozoic Period, these two landmasses were more associated with the southern continents of Australia, Antarctica, and South America. India wasn't even a part of Asia until after the dinosaurs went extinct.

Late Cretaceous Madagascar and India, Walter Myers

During the age of reptiles, India and Madagascar were best buddies, and biogeographically, palaeontologists unite these two as their own distinct region. In terms of dinosaur diversity, the two regions share a lot in common with South America. Titanosaur Sauropods and Abelisaur Theropods are king in these regions. So when I started to construct a list of dinosaur highlights, I found it difficult to make a list of dinosaurs that weren't all Sauropods and Abelisaurs. So compared to my Africa, and Asia episodes, this list will be a bit shorter, but rest assured, there is a lot to discover about dinosaurs from Madagascar and India.

Isisaurus colberti

Isisaurus, Dmitry Bogdanov

Isisaurus was a large sauropod from Late Cretaceous India. It was a member of the Titanosaur clade, the largest and longest, and heaviest of all dinosaurs. Isisaurus colberti was originally called Titanosaurus colberti, united with the Indian dinosaur that this clade is named after, but closer inspection of its fossils led palaeontologists to classify Isisaurus in its own genus. Titanosaurus itself is currently a nomen dubium: a species that may not be real because remains are too fragmentary to be sure.

The most distinguishing feature of Isisaurus is its tall neck spines, giving it a very unique appearance for a Titanosaur, but it's not really known why they had them. Isisaurus coprolites (fossil poo) have had parts of pathogenic (diseasing) fungus found in them, giving paleobotanists a unique insight into the plant life of its habitat. Isisaurus is also unique in its name. It does not in fact call reference to the Egyptian God Isis, but it is fact named for the ISI (Indian Statistical Institution), making the only dinosaur I personally know to be named after an acronym.

Barapasaurus tagorei

Barapasaurus, SpinoInWonderland (deviantart)

Barapasaurus was an Early Jurassic Sauropod from central India. It was very early for a Sauropod, evolutionarily, but quite large for its time, 5.5 m tall and 14 m long. It's skeleton reveals a lot of traits basal to the true sauropod group, but was primitive in others, particularly its feet. Barapasaurus was the first dinosaur skeleton to be mounted in an Indian Museum, in 1977. It's name is also part Indian (Bengali), Bara meaning "Large", and Pa meaning "Leg" and of course the Greek Saurus to end it out. The large leg bone in question being the first bone of the animal found.

Dravidosaurus blandfordi

Dravidosaurus, Pavel Riha

Dravidosaurus was (potentially) a late surviving Stegosaur found in Late Cretaceous India. So far in these lists, I've tried to avoid highlighting Nomen Dubium, but I wanted a bit of variety in my Indian Dinosaurs, so this is an exception. Dravidosaurus is named for the Dravidanadu region of South India where it was found. Studies of the specimen in the 1990s hypothesised it was a plesiosaur, a type of marine reptiles related to turtles. But studies in the 2010s decided that among the remains found are a Stegosaur back plate and tail spike, but there's still too little material to be sure of anything. If it was indeed a Stegosaur, it was one of the smallest, 3 metres long and maybe half a metre tall.

Rahonavis ostromi

Rahonavis, Julio Lacerda (@paleoart on tumblr)

Rahonavis was a small theropod dinosaur from Late Cretaceous Madagascar. It's exact classification has been subject to much debate since it was first described, as it lies right on the boundary between non-avian dinosaurs and the earliest true birds. Depending on who you ask, Rahonavis is either a basal Avialan like Archaeopteryx, or an extremely derived dromeosaur like Dakotaraptor or Microraptor. Given the shape of its arms, and the evidence of flight feathers, Rahonavis was likely capable of flight, but wasn't as good in the air as modern birds. It was the size of a typical modern bird too, about 70 cm long. It's name consists of the Malagasy Rahona, meaning "Cloud/Menacing" and the Latin Avis, meaning "Bird".

Majungasaurus crenatissimus

Majungasaurus, Moonmelo (deviantart)

Majungasaurus was a medium sized Abelisaur theropod from Madagascar. It was from the very end of the Cretaceous period, one of the last dinosaurs. Majungasaurus was about 3 m tall and 8 m long. It had one of the most complete skull fossils of its family, with a blunt snout, sturdy, but wrinkled face structure, and its signature cone shaped horn right between its eyes. The horn was not built for combat and would've likely been a display structure. Its short but robust jaw allowed Majungasaurus and other Abelisaurs to bite down and twist more effectively than other theropods, and may have been specialised for hunting the many Sauropod species that inhabited Madagascar in its time. Majungasaurus is named for the Mahajunga province of North Madagascar.

The unique horn shape may be the most visual diagnostic feature of Majungasaurus, but many actually know the dinosaur for being the only non-avian dinosaur to have evidence of cannibalism. Signature bite marks found in Majungasaurus prey has also been found in other adult and juvenile Majungasaurus specimens. Palaeontologists are unsure if this is evidence of Majungasaurus actively hunting other members of its species, or if they simply scavenged on the dead.

Thanks for Reading

I apologise for making this article a bit shorter than the last couple has been. I've been trying to include some variety in dinosaur clades in these regional highlights, so rather than discuss mostly Abelisaurs and Titanosaurs, I picked one of each and then a few more notable species I could find. There really are a lot of interesting species from both India and Madagascar, so I recommend looking up info on the other interesting dinosaurs from the regions.

Next blogpost I'm thinking Europe, and there's quite a few interesting species I can think of already without consulting the entire list of species. My intention is to do North America last, since most of the species people know are from there and I want my readers to savour what the rest of the world has to offer first. As usual, links to previous and future articles below, and will be edited once I have written more.

<< Part 3: Africa || Part 5: Europe >>

#blog#blogpost#palaeontology#dinosaurs#indian dinosaurs#madagascan dinosaurs#isisaurus#barapasaurus#dravidosaurus#rahonavis#majungasaurus

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

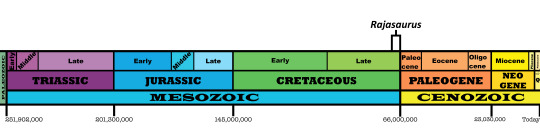

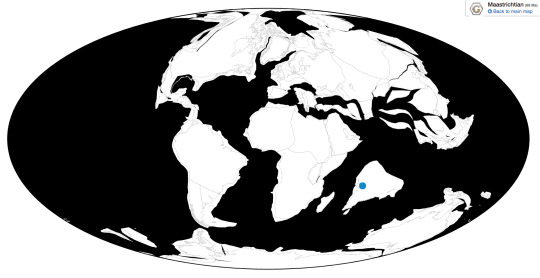

Rajasaurus narmadensis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: King Reptile

First Described By: Wilson et al., 2003

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Ceratosauria, Neoceratosauria, Abelisauroidea, Abelisauridae, Majungasaurinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 70 and 66 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

Rajasaurus is known from the Lameta Formation of Gujarat, India

Physical Description: Rajasaurus was an Abelisaur - so, a kind of theropod with a long body, almost nonexistent arms, and thick, powerful legs. Rajasaurus in particular differed from other Abelisaurs in having particularly short legs, making it even more… sausage-like… in appearance than even its close relatives. It had a boxy head and thick neck, which would allow it to have a very powerful bite and strength in the neck to hold down prey. It had a strong sense of smell, as well, to help it to find prey from farther away - allowing it to set up an ambush for said prey when it got too close. It had horns on its forehead, made of bone from the nose, which was probably not extended by skin. It was also a lot shorter than other Abelisaurids - which means that it was only about 7 or so meters long, and maybe only two meters tall, if that. It really wouldn’t have stood much taller than an adult man. Rajasaurus had an especially short neck, which may have allowed it to grab onto prey even tighter than other Abelisaurids. It had very short, four-fingered hands, with claws on the first three of them. Though the legs of Rajasaurus are short, it did have very robust, thick toes, giving it more support on the ground. As an Abelisaurid, Rajasaurus was covered in scales all over its body, with potentially round bumpy bits of bone (osteoderms) interspersed among the scales.

By Paleocolour, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: As a large Abelisaurid, Rajasaurus would have primarily fed upon larger herbivores, such as Titanosaurs.

Behavior: Abelisaurs were not the fastest animals - after all, if they ran too quicky, they wouldn’t have been very balanced - but what they were extremely agile turners. Being able to turn very quickly allowed them to be efficient ambush predators. Rajasaurus would have waited for prey to appear, and then charged - seemingly out of nowhere, by turning rapidly towards the prey - and then grabbing down onto the struggling prey with its strong, boxy jaws. Though Rajasaurus had small arms and hands, it traded those off for having a stronger neck - to better hold the prey steady with. Then, the stress would weaken the animal, along with blood loss. The horns on the head of Rajasaurus were probably for display and interaction between members of the species, with fights occurring to argue over carcasses or for mates via head-butting or neck-bashing. The horns would have also packed quite a bit of a cutting edge in these fights. It’s also possible that bright colors could have been used on the horns to display. While it doesn’t seem likely that Rajasaurus was particularly social, it did probably take care of its young, and may have formed small family groups while they grew up, in order to protect the young from the many other predators around.

By ДиБгд, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ecosystem: The Lameta Formation is a fascinating Late Cretaceous environment due to the fact that it was a grassland! Grasses evolved sometime in the Cretaceous period. While they did not spread rapidly until the Cenozoic, they did seem to be present in quite a few areas during the Cretaceous (to the point of some hadrosaur relatives evolving to eat them). India at the time was an isolated island, so grasses were able to thrive and diversify more there than in other locations where they did not gain as immediate of a foothold. There was a large amount of volcanic activity nearby, which probably added to its extensive biodiversity (before it made many of the animals present go extinct, via the explosion of the Deccan Traps). It was a lush environment filled with grasses resembling modern rice, flowers, algae, and ferns. This was an environment filled with many lakes, surrounded by extensive mud that lead to its fossil preservation. Rajasaurus was certainly not the only dinosaur of this environment, either! There were even other Abelisaurids - Indosaurus, Indosuchus, Rahiolisaurus, Lametasaurus, and their close relatives the (potentially piscivorous) Noasaurids such as Ornithomimoides, Laevisuchus, and Dryptosauroides. There were also other theropods, probably also Ceratosaurs - Jubbulpuria, Coeluroides, and Orthogoniosaurus. With all of these predators and fishermen, it makes sense that there were a lot of large herbivores for them to feed upon! And there seem to be at least three different kinds of titanosaurs there - Titanosaurus, a dubiously known one; Jainosaurus, a slightly better known one; and Isisaurus, the best known one that seems to be one of the main features of the environment. There was also potentially an ankylosaur - Brachypodosaurus! As for non-dinosaurs, there were large snakes, Sanajeh and Madtsoia; a variety of turtles; and some Dyrosaurid crocodylomorphs!

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Rajasaurus was one of the Majungasaurines, which had longer holes in their snouts in front of their eyes than their close relatives the Carnotaurines - aka, they had lighter skulls - and having small crests widening the front of their heads; and, in general, longer snouts. This group of Abelisuarids underwent extensive island hopping, reaching places like India via rafting and other journeys across the ocean. Rajasaurus, being one of them, had ancestors that underwent such a journey!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Brookfield, M. E.; Sanhi, A. (1987). "Palaeoenvironments of the Lameta beds (late Cretaceous) at Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India: Soils and biotas of a semi-arid alluvial plain". Cretaceous Research. 8 (1): 1–14.

Carrano, M. T.; Sampson, S. D. (2008). "The phylogeny of Ceratosauria" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 183–236.

Cau, A., F. M. Dalla Vecchia, and M. Fabbri. 2012. Evidence of a new carcharodontosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57(3):661-665

Delcourt, R. (2018). "Ceratosaur Palaeobiology: New Insights on Evolution and Ecology of the Southern Rulers". Scientific Reports. 8 (9730).

Filippi, L. S., A. H. Méndez, R. D. Juárez Valieri and A. C. Garrido. 2016. A new brachyrostran with hypertrophied axial structures reveals an unexpected radiation of latest Cretaceous abelisaurids. Cretaceous Research 60:209-219

Furtado, M. R., C. R. A. Candeiro, and L. P. Bergqvist. 2013. Teeth of Abelisauridae and Carcharodontosauridae cf. (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Campanian- Maastrichtian Presidente Prudente Formation (southwestern São Paulo State, Brazil). Estudios Geológicos 69(1):105-114

Gianechini, F. A., S. Apestteguia, W. Landini, F. Finotti, R. J. Valieri and F. Zandonai. 2015. New abelisaurid remains from the Anacleto Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Patagonia, Argentina. Cretaceous Research 54:1-16

Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89.

Kapur, V. V.; Khosla, A. (2016). "Late Cretaceous terrestrial biota from India with special reference to vertebrates and their implications for biogeographic connections". Cretaceous Period: Biotic Diversity and Biogeography. 71: 161–172.

Mohabey, D. M. 1989. The braincase of a dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Lameta Formation, Kheda District, Gujarat, western India. Indian Journal of Earth Sciences 16(2):132-135

Mohabey, D. M. (1996). "Depositional environment of Lameta Formation (late Cretaceous) of Nand-Dongargaon inland basin, Maharashtra: the fossil and lithological evidences". Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India. 37: 1–36.

Mohabey, D. M.; Samant, B. (2013). "Deccan continental flood basalt eruption terminated Indian dinosaurs before the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary" (PDF). Geological Society of India Special Publication (1): 260–267.

Novas, F. E., S. Chatterjee, D. K. Rudra and P. M. Datta. 2010. Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis, n. gen. n. sp., a new abelisaurid theropod from the Late Cretaceous of India. In S. Badyopadhyay (ed.), New Aspects of Mesozoic Biodiversity. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 132. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 45-62

Persons IV, W. S.; Currie, P. J. (2011). "Dinosaur speed demon: the caudal musculature of Carnotaurus sastrei and implications for the evolution of South American abelisaurids". PLoS One. 6 (10): e25763.

Prasad, V.; Strömberg, C.A.; Leaché, A.D.; Samant, B.; Patnaik, R.; Tang, L.; Mohabey, D.M.; Ge, S.; Sahni, A. (2011). "Late Cretaceous origin of the rice tribe provides evidence for early diversification in Poaceae". Nature Communications. 2: 480.

Prasad, V., C. A. E. Strömberg, H. Alimohammadian, A. Sahni. 2005. Dinosaur Coprolites and the Early Evolution of Grasses and Grazers Science 310 (5751): 1177-1180.

Prasad, G. V. R., and A. Sahni. 2009. Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate fossil record from India: palaeobiogeographical insights. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France 180(4):369-381

Ratsinbaholison, N. O., R. N. Felice, and P. M. O'Connor. 2016. Ontogenetic changes in the craniomandibular skeleton of the abelisaurid dinosaur Majungasaurus crenatissimus from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61(2):281-292

Rogers, Raymond R.; Krause, David W.; Curry Rogers, Kristina; Rasoamiaramanana, Armand H.; Rahantarisoa, Lydia. (2007). "Paleoenvironment and Paleoecology of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". In Sampson, S. D.; Krause, D. W. (eds.). Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 8. 27. pp. 21–31.

Sahni, A. 1972. Paleoecology of Lameta Formation at Jabalpur (M.P.). Current Science 41(17):652

Sahni, A. 1984. Cretaceous-Paleocene terrestrial faunas of India: lack of endemism during drifting of the Indian Plate. Science 226(4673):441-443

Sampson, Scott D.; Witmer, L. M. (2007). "Craniofacial anatomy of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". In Sampson, S. D.; Krause, D. W. (eds.). Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 8. 27. pp. 32–102.

Sereno, P. C.; Wilson, J. A.; Conrad, J. L. (2004). "New dinosaurs link southern landmasses in the Mid–Cretaceous". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 271 (1546): 1325–1330.

Sereno, P. C.; Brusatt, S. L. (2008). "Basal abelisaurid and carcharodontosaurid theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation of Niger" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (1): 15–46.

Sonkusare, H.; Samant, B.; Mohabey, D. M. (2017). "Microflora from Sauropod Coprolites and Associated Sedimentsof Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Lameta Formation of Nand-Dongargaon Basin, Maharashtra". Geological Society of India. 89 (4): 391–397

Tandon, S. K.; Sood, A.; Andrews, J. E.; Dennis, P. F. (1995). "Palaeoenvironments of the dinosaur-bearing Lameta Beds (Maastrichtian), Narmada Valley, Central India". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 117 (3–4): 153–184.

Tortosa, T., E. Buffetaut, N. Vialle, Y. Dutour, E. Turini and G. Cheylan. 2013. A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of southern France: palaeobiogeographical implications. Annales de Paléontologie.

Vianey-Liaud, M.; Khosla, A.; Garcia, G. (2003). "Relationships between European and Indian dinosaur eggs and eggshells of the oofamily Megaloolithidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3): 575–585.

Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loueff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth M.P.; Noto, Christopher N. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 517–606.

Wilson, J. A., P. C. Sereno, S. Srivastava, D. K. Bhatt, A. Khosla and A. Sahni. 2003. A new abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lameta Formation (Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of India. Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan 31(1):1-42

Wilson, J. A.; Mohabey, D. M.; Peters, S. E.; Head, J. J. (2010). "Predation upon hatchling dinosaurs by a new snake from the Late Cretaceous of India". PLoS One. 8 (3): e1000322.

#Rajasaurus narmadensis#Rajasaurus#Abelisaurid#Dinosaur#Ceratosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Theropod Thursday#Carnivore#India & Madagascar#Cretaceous#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

191 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My jeweler friend, Megin Spivey, sent Alex a surprise mini-museum birthday package. The large rock is 60m+ year old dino dung (coprolite). Clockwise, there is also a: piece of fossilized turtle shell, labradorite Ganesh, skull fragment, Mako shark tooth, ancient Mayan deity carving, geode in matrix and a tiny metal Shiva. Spivey creates one-of-a-kind men’s cufflinks and accessories inspired by her world travels. Thanks for these amazingly thoughtful treasures @spiveyjewelry https://www.instagram.com/p/CGXuwZagBxH/?igshid=9pwqhhudj0z1

0 notes

Text

Trinkets, Worthless, 1: These trinket are garbage plain and simple. They would be termed vendor trash or junk loot in video games. They aren't touched by stray magic or mystery as with regular trinkets, aren't made from valuable materials and aren't particularly useful even if they aren't damaged.

A beige jar of pungent red ointment without a label.

A bit of rock from the headstone of a loving parent.

A blank piece of wet parchment that never seems to dry.

A blob of grey goo in a ceramic pot. It is slippery but safe to touch

A bone knife and fork.

A bronze gear on which is etched the word "Moon"

A brown mushroom of extraordinary size.

A candied apple carved into the shape of a human skull.

A canteen filled with a foul smelling orange mud.

A clockwork device whose button won't press no matter what is done to it.

---Keep reading for 90 more trinkets.

---Note: The previous 10 items are repeated for easier rolling on a d100.

A beige jar of pungent red ointment without a label.

A bit of rock from the headstone of a loving parent.

A blank piece of wet parchment that never seems to dry.

A blob of grey goo in a ceramic pot. It is slippery but safe to touch

A bone knife and fork.

A bronze gear on which is etched the word "Moon"

A brown mushroom of extraordinary size.

A candied apple carved into the shape of a human skull.

A canteen filled with a foul smelling orange mud.

A clockwork device whose button won't press no matter what is done to it.

A cloth pouch containing a dozen useless wooden tokens previously issued by a traitor-prince as currency

A cloth pouch containing ten dried peas

A corkscrew

A cracked, bone smoking pipe

A crude chalice made of coal.

A curiously stained towel (Knowledgeable PC's can identify the stains as brain matter) with a set of instructions embroidered on it, that clearly state to wear it on the head in case of mind flayer attack.

A desiccated body of a small eight-legged black lizard.

A doll head with no hair and poorly applied makeup

A faceless doll made of driftwood.

A feather with a piece of red string tied on the end of the shaft.

A fire-blackened claw of some great beast.

A fist sized turtle shell.

A fist-sized cog, covered in barnacles.

A fist-sized wooden sphere; half of which is blue while the other half is red.

A glass jar that appears to contain boiled cabbage, vinegar and several spices.

A goblin-made key that never works in any lock

A good luck charm made of animal bones and twine.

A half dozen pages ripped out of an accounting journal of a local merchant

A hand sized fossil of an extinct many-limbed insect

A hand sized piece of fossilized excrement, commonly known as coprolite

A hand-sized box covered with numbered buttons

A hollow wooden doll that splits in half to reveal a slightly smaller, identical, doll. The second one is empty, perhaps there are still smaller dolls that are missing?

A horn that has been cut cleanly in half.

A humanoid poppet, made from twisted roots, with singed limbs

A keychain holding the head of a broken key

A leather pouch containing irregular iron nails, some of them bent out of shape as though used.

A letter of complaint to a toy shop owner

A map of a labyrinth, on which is pencilled a line that starts at the centre but fails to connect to the entrance

A map with no key, legend or locations, only red circles with lines connecting them.

A measuring tape, marked in ink at 23 inches

A pair of badly worn hairdressing scissors

A palm-sized iron cage: the door doesn't shut properly, as the tiny lock was broken from the inside

A pamphlet for Irytor's World of the Spectacular, the phrase 'closing down' has been scrawled on it in faded ink.

A pamphlet that has illustrated instructions on how to make a paper hat out of the pamphlet

A petrified eye of a cat.

A petrified goat skull.

A pewter spork

A pickled human toe.

A piece of coal vaguely shaped like a head.

A piece of tree bark that is coated in blood.

A pouch full of a fine black powder of unknown origin.

A preserved monkey's paw, with three fingers outstretched

A pretty conch shell

A puzzle box containing ten fingernail clippings

A rag doll in the likeness of an owlbear.

A red and black vulture feather.

A red woollen cap that appears to be stained with blood.

A rough stone eye extracted from an unknown petrified creature.

A rusted fork.

A sack full of pieces of half-eaten bread.

A scrap of paper on which is written, in Goblin, "My dearest Bess,"

A seashell that is silent when held up to your ear

A seed that never grows when planted, but looks very similar to an acorn with a few green lumps.

A set of bent and broken thieves tools

A set of five rusty, bent, nails, stained with a black liquid.

A sheet of vellum on which is crudely painted a herbal plant that is not identifiable

A single leather shoe made for a dog

A slip of parchment with the phrase "I am not dead" written on it.

A small black cauldron that appears to have meat juices burnt onto the bottom of it.

A small bubble leveller that is calibrated incorrectly

A small ceramic container, half filled with lemon lip balm

A small tin containing spoiled fish eggs.

A small wooden box filled with a strange red clay.

A small, clay square with an unknown rune etched into one side.

A small, cracked porcelain doll with most of it's hair burnt off.

A small, wooden toy horse.

A split piece of unknown wood, decorated to look as if it once was a piece of a druidic focus.

A stone rod with a tin coating that has worn through in several places.

A strangely shaped bone.

A thin iron pinky ring, melted and charred but still wearable

A ticket admitting an adult and child onto something called a "semiotic tram"

A tine of a deer's antler.

A tiny bag of yellowish powder that seems to have no practical use.

A tiny, broken clockwork harpy.

A twenty-sided die carved from bone

A vibrant peacock tail feather

A vine covered in thorns that writhes around occasionally.

A wax hand shaped to hold a large cup

A wooden device designed to be gripped in two hands. Two levers protrude from the top, and two triggers from the underside.

A wooden spoon, carved from a bigger spoon.

An apparently empty green glass bottle that is sealed with red wax.

An axehead that appears to have been snapped off with extreme force

An eight sided die that looks to have been split in half by a large axe.

An empty bottle that once held the blood of a demon.

An evening dinner menu, there are spots of what appear to be dried blood on it.

An invitation to a lavish event that has already ended.

An ivory knitting needle

An odd lump of metal that smells like sweat and rotten fish.

An ornate pewter tankard made without a bottom

An unusually sharp spoon.

#d&d#dnd#d&d 3.5#d& 4e#d&d 5e#d&d homebrew#d&d 5e homebrew#loot#custom loot#loot generator#random loot table#pathfinder#trinkets#roleplaying#rpg#dungeons and dragons#dungeon master#dm#d&d ideas#treasure#treasure table#d&d resources#tabletop homebrew#junk loot#vendor trash#d&d 4e

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fossil Shark Coprolite with Fish Scales & Bone London Clay Eocene Isle of Sheppey Kent UK Authentic Specimen

This listing features a fossilised shark coprolite (poo) containing preserved fish scales and bone fragments, collected from the world-renowned London Clay Formation on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, UK. This is a carefully selected and scientifically significant specimen from the Lower Eocene Epoch, and comes with a Certificate of Authenticity.

Coprolites are trace fossils representing the preserved faeces of ancient animals. In this case, the specimen is attributed to a predatory shark, as indicated by the inclusion of fish scale and bone material—evidence of diet and digestive processes in Eocene marine ecosystems.

The London Clay Formation is one of the most fossiliferous geological units in Europe, formed approximately 56 to 47.8 million years ago during the Ypresian Stage of the Eocene Period. The environment was a shallow, subtropical marine shelf rich in diverse marine fauna, including sharks, rays, bony fish, turtles, and crocodilians.

Morphology Features:

Irregular to spiral or elongate form typical of vertebrate coprolites

Mineralised matrix with embedded fish scale and bone inclusions

Brown-grey coloration due to clay mineral preservation

Often contains phosphatic components from digestive processes

These inclusions make this coprolite especially valuable as a direct window into predator-prey interactions and dietary evidence of ancient marine vertebrates.

The photograph shows the exact specimen you will receive. Scale rule squares/cube = 1cm. Please refer to the image for full size and detail.

Specimen Details:

Fossil Type: Shark Coprolite with Fish Scale & Bone Inclusions

Geological Unit: London Clay Formation

Geological Age: Early Eocene (Ypresian Stage)

Location: Isle of Sheppey, Kent, UK

Depositional Environment: Subtropical shallow marine shelf

Significance: Trace fossil showing ancient shark diet

This is an exceptional and rare example of a coprolite containing visible prey remains, ideal for fossil enthusiasts, educational collections, and anyone fascinated by the real-life ecology of prehistoric oceans.

All of our Fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens & come with a Certificate of Authenticity.

#shark coprolite fossil#fossilised shark poo#London Clay coprolite#Eocene fossil faeces#fish scale coprolite#fossil fish remains#Sheppey fossil#Kent UK coprolite#ancient shark diet#authentic coprolite with certificate#fossilised fish bone#Eocene shark remains#fossilised poo with inclusions#UK coprolite specimen#rare shark coprolite fossil#Sheppey marine fossil

0 notes

Photo

Happy birthday to meeeeee! After a crappy day at work, it was nice to come home to this huge fossilized mastodon tooth I got myself from eBay. It now joins my main fossil shelf, alongside a partial fossilized whale vertebra that I found, coprolite, crocodile jaw fragment, turtle skull piece, large fish or shark vertebra, and whale inner ear bone.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossilized Tooth Captures a Pterosaur’s Failed Squid Meal

About 150 million years ago, a pterosaur experienced an embarrassing mealtime mishap. Attempting to catch and eat a seafood snack, the flying reptile came away one tooth short.

At least, that is the chain of events suggested by a fossil described earlier this week in Scientific Reports: a preserved cephalopod with a pterosaur tooth embedded inside of it.

This “fossilized action snapshot” is the first evidence scientists have that these winged contemporaries of dinosaurs ate prehistoric squid, or at least tried, said Jean-Paul Billon Bruyat, an expert in prehistoric reptiles who was not involved in the research.

The fossil also joins a small group of records that hint at the ecological relationships between ancient creatures.

The specimen, which was found in Germany’s Solnhofen fossil beds, is an 11-inch-long coleoid cephalopod, a precursor to today’s squids, octopuses and cuttlefish. It is preserved well enough that its ink sac and fins are readily visible, as is the very sharp-looking tooth stuck just below its head.

René Hoffmann, an author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher at Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany and an expert in prehistoric cephalopods, came across a photo of the fossil last year and was immediately intrigued.

“Two fossils together could give us an idea of predator-prey relationships,” he said.

Based on the tooth’s shape, size and texture, along with the fossil’s location and age, the tooth probably belonged to Rhamphorhynchus muensteri. The species had a five-foot wingspan, said Jordan Bestwick, a paleobiologist at the University of Leicester in England who specializes in pterosaur diets and was an author of the paper.

Rhamphorhynchus hunted fish, likely by flying over the water and snapping them up. But this is the first direct evidence that these pterosaurs also had a taste for cephalopods, said Dr. Bestwick.

It is also the only record of “a failed predation attempt” made by any pterosaur. (Sorry, bud.)

The researchers also used ultraviolet light — which can differentiate between sediment and formerly living tissue — to determine if the tooth was stuck inside the cephalopod when both were fossilized, not merely lying on top. Overlap between the mantle tissue and the tip of the tooth showed that the tooth was embedded least half an inch deep.

Once that was settled, the researchers imagined the scenario.

Reconstructing ancient encounters is always “highly speculative,” said Dr. Hoffmann. But he pictured the pterosaur flying over the water when its shadow scared a group of cephalopods, which began jumping out of the water.

“Then the pterosaur grabbed one, but not perfectly,” said Dr. Hoffmann. The cephalopod thrashed around. It managed to get away — and took the reptile’s tooth with it.

For the sea creature, a daring escape. For the pterosaur, a calamari calamity.

But one that led to some scientific insight, at least. “It is very difficult to demonstrate a fossilized predator-prey relationship,” said Dr. Billon-Bruyat. Paleontologists sometimes find preserved prey within a predator’s stomach or throat, or inside fossilized feces, called coprolites.

Occasionally, more creative interspecies encounters are preserved. Last year, Dr. Billon-Bruyat was part of a team that studied the shell of an ancient sea turtle that had apparently been stepped on by a sauropod.

And the tables may have been turned on some pterosaurs. They have been found often enough next to a fossilized large prehistoric fish called Aspidorhynchus that some researchers think the flying reptiles were frequently seized by the fish.

Although Dr. Billon-Bruyat is convinced by the new paper’s interpretation of the cephalopod fossil, other experts are less certain.

Because the tooth is embedded in soft tissue rather than bone, it is possible the two became entangled in some other way, said Jingmai O’Connor, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing: “Perhaps the squid fell to the bottom of the sea when it died and landed on a pterosaur tooth.”

Dr. O’Connor also wondered why pterosaurs would have eaten cephalopods if doing so was so risky, although she granted that everyone has bad luck.

“I’ve broken a tooth eating a samosa,” she said. “So nearly anything is possible.”

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/fossilized-tooth-captures-a-pterosaurs-failed-squid-meal/

0 notes

Text

Prague Zoo's New Exhibit Takes A Closer Look At Poop

Prague Zoo’s New Exhibit Takes A Closer Look At Poop

[ad_1]

PRAGUE (AP) — After producing plenty of elephant dung and other manure for years, Prague Zoo has capitalized on its expertise by creating a new permanent exhibit on the world of animal excrement.

It displays information and samples of everything from fossil turds, also known as coprolites, from extinct animals to the excrement of modern-day gorillas, lions, elephants, horses, turtles,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Pneumatoraptor fodori

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Thief of Air

First Described By: Ősi, Apesteguía & Kowalewski, 2010

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 85 million years ago, in the Santonian of the Late Cretaceous

Pneumatoraptor is known from the Csehbánya Formation of Hungary

Physical Description: Pneumatoraptor is a small Paravian, aka the group of dinosaurs that includes birds and proto-birds, raptors, and Troodontids. However, we have no idea what sort of Paravian Pneumatoraptor would have been, if any. It is only known from the left shoulder, which shows that it had a very narrow and hollow shoulder bone than its relatives. Beyond that, we have no idea what it may have looked like - it could have been from any of the three main Paravian groups (Avialans, Troodontids, and Dromaeosaurs). It probably would have been very small, only about 0.73 meters in body length. It definitely would have been covered in feathers all over its body, including complex wings. Teeth, claws, vertebrae, and part of the leg bone of Pneumatoraptor may have been found in its ecosystem, but the jury is still out.

Diet: It is uncertain what Pneumatoraptor would have eaten. Since it isn’t a definite dromaeosaur, we can’t say confidently that it was carnivorous; many creatures at the base of the Paravian tree are possibly omnivores. In addition, early raptors (which Pneumatoraptor may have been) seem to have been piscivores! So the jury is out till we have its jaw.

Behavior: Without more fossils, it’s uncertain what Pneumatoraptor’s behavior would have been like, since it could have been one of three very distinctive dinosaur groups (or something else entirely). Based on its relatives, it probably was very active and warm-blooded, took care of its young, and used its wings and tail fan in display and communication. It may have even been able to fly poorly, but that’s just speculation on my part.

Ecosystem: The Csehbánya Formation has been a flourishing site of extensive research over the past few years, as more and more fossils come out of the ecosystem to show a slice of Late Cretaceous life in Eastern Europe. This was a plant-heavy forest ecosystem, with extensive mud, silt, clay, and sand throughout the environment. River channels flooded through the ecosystem, providing water for the extensive number of animals present. Here, Pneumatoraptor lived alongside many other dinosaurs - the small Ceratopsian Ajkaceratops; two fast-moving ankylosaurs, Hungarosaurus and Struthiosaurus, the Rhabdodont ornithopod Mochlodon, the predatory opposite bird Bauxitornis, and plenty of unnamed dinosaurs including an Abelisaurid and a Sauropod. Pneumatoraptor would have feared predation by the Abelisaurid. Non-dinosaurs were extensive too - the pterosaur Bakonydraco, a variety of turtles, many kinds of weird lizards including a Mosasaur, a variety of frogs, many fish and insects, and crocodyliformes - including Kharkutosuchus and Doratodon. Going forward, more research on this ecosystem is sure to reveal even more weird creatures!

Other: Pneumatoraptor was extremely small for its group, indicating it may be closer to Avialans than to Dromaeosaurs.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Borkent, Art (1997). "Upper and Lower Cretaceous biting midges (Ceratopogonidae: Diptera) from Hungarian and Austrian amber and the Koonwarra Fossil Bed of Australia". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde (B) Geologie und Paläontologie. 249: 1–10.

Botfalvai, Gábor; Ősi, Attila; Mindszenty, Andrea (January 2015). "Taphonomic and paleoecologic investigations of the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Iharkút vertebrate assemblage (Bakony Mts, Northwestern Hungary)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 417: 379–405.

Botfalvai, Gábor; Haas, János; Bodor, Emese Réka; Mindszenty, Andrea; Ősi, Attila (2016). "Facies architecture and palaeoenvironmental implications of the upper Cretaceous (Santonian) Csehbánya formation at the Iharkút vertebrate locality (Bakony Mountains, Northwestern Hungary)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 441: 659–678.

Cau, A., V. Beyrand, D. F. A. E. Voeten, V. Fernandez, P. Tafforeau, K. Stein, R. Barsbold, K. Tsogtbaatar, P. J. Currie and P. Godefroit. 2017. Synchrotron scanning reveals amphibious ecomorphology in a new clade of bird-like dinosaurs. Nature

Gareth J. Dyke, Attila Ősi (2010). "A review of Late Cretaceous fossil birds from Hungary". Geological Journal. 45 (4): 434–444.

Makádi, L., Botfalvai, G., Ősi, A. 2006: Egy késő-kréta kontinentális gerinces fauna a Bakonyból: halak, kétéltűek, teknősök, gyíkok. Földtani Közlöny 136/4, pp. 487-502.

Makádi, László (December 2006). "Bicuspidon aff. hatzegiensis (Squamata: Scincomorpha: Teiidae) from the Upper Cretaceous Csehbánya Formation (Hungary, Bakony Mts)". Acta Geologica Hungarica. 49 (4): 373–385.

Makádi, László; Caldwell, Michael W.; Ősi, Attila (2012-12-19). "The First Freshwater Mosasauroid (Upper Cretaceous, Hungary) and a New Clade of Basal Mosasauroids". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e51781.

Makádi, László (July 2013). "The first known chamopsiid lizard (Squamata) from the Upper Cretaceous of Europe (Csehbánya Formation; Hungary, Bakony Mts)". Annales de Paléontologie. 99 (3): 261–274.

Makádi, László (November 2013). "A new polyglyphanodontine lizard (Squamata: Borioteiioidea) from the Late Cretaceous Iharkút locality (Santonian, Hungary)". Cretaceous Research. 46: 166–176.

Makádi, László; Nydam, Randall L. (2014-12-23). "A new durophagous scincomorphan lizard genus from the Late Cretaceous Iharkút locality (Hungary, Bakony Mts)". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 89 (4): 925–941.

Ösi, Attila; Weishampel, David B.; Jianu, Coralia M. (2005). "First evidence of azhdarchid pterosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Hungary". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50 (4): 777–787.

Ösi, Attila. 2005. Hungarosaurus tormai, a new ankylosaur (Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Hungary. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(2):370-383, June 2005.

Ősi, A. & Rabi, M., 2006. Egy késő-kréta kontinentális gerinces fauna a Bakonyból II.: krokodilok, dinoszauruszok, pteroszauruszok és madarak (The Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate fauna from the Bakony Mountains II: crocodiles, dinosaurs (Theropoda, Aves, Ornithischia), pterosaurs). Földtani Közlöny, 136, 4, 503–526.

Ősi, Attila; Clark, James M.; Weishampel, David B. (2007-02-01). "First report on a new basal eusuchian crocodyliform with multicusped teeth from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) of Hungary". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 243 (2): 169–177.

Ősi, A.; Butler, R.J.; Weishampel, David B. (2010). "A Late Cretaceous ceratopsian dinosaur from Europe with Asian affinities". Nature. 465 (7297): 466–468.

Ősi, A., S. Apesteguíia, and M. Kowalewski. 2010. Non-avian theropod dinosaurs from the early Late Cretaceous of central Europe. Cretaceous Research 31(3):304-320

Ősi, Attila; Buffetaut, Eric (January 2011). "Additional non-avian theropod and bird remains from the early Late Cretaceous (Santonian) of Hungary and a review of the European abelisauroid record". Annales de Paléontologie. 97 (1–2): 35–49.

Ősi, A.; Prondvai, E.; Butler, R.; Weishampel, D. B. (2012). Evans, Alistair Robert (ed.). "Phylogeny, Histology and Inferred Body Size Evolution in a New Rhabdodontid Dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Hungary". PLoS ONE. 7 (9): e44318.

Ősi, Attila; Prondvai, Edina (August 2013). "Sympatry of two ankylosaurs (Hungarosaurus and cf. Struthiosaurus) in the Santonian of Hungary". Cretaceous Research. 44: 58–63.

Ősi, Attila; Bodor, Emese Réka; Makádi, László; Rabi, Márton (2016). "Vertebrate remains from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) Ajka Coal Formation, western Hungary". Cretaceous Research. 57: 228–238.

Ősi, Attila; Csiki-Sava, Zoltán; Prondvai, Edina (2017-06-12). "A Sauropod Tooth from the Santonian of Hungary and the European Late Cretaceous 'Sauropod Hiatus'". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 3261.

Ősi, Attila; Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier (July 2017). "Notes on the pelvic armor of European ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Cretaceous Research. 75: 11–22.

Prondvai, Edina; Botfalvai, Gábor; Stein, Koen; Szentesi, Zoltán; Ősi, Attila (March 2017). "Collection of the thinnest: A unique eggshell assemblage from the Late Cretaceous vertebrate locality of Iharkút (Hungary)". Central European Geology. 60 (1): 73–133.

Rabi, Márton; Sebők, Nóra (October 2015). "A revised Eurogondwana model: Late Cretaceous notosuchian crocodyliforms and other vertebrate taxa suggest the retention of episodic faunal links between Europe and Gondwana during most of the Cretaceous". Gondwana Research. 28 (3): 1197–1211.

Segesdi, Martin; Botfalvai, Gábor; Bodor, Emese Réka; Ősi, Attila; Buczkó, Krisztina; Dallos, Zsolt; Tokai, Richárd; Földes, Tamás (June 2017). "First report on vertebrate coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) Csehbánya Formation of Iharkút, Hungary". Cretaceous Research. 74: 87–99.

Szabó, Márton; Gulyás, Péter; Ősi, Attila (April 2016). "Late Cretaceous (Santonian) pycnodontid (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontidae) remains from the freshwater deposits of the Csehbánya Formation, (Iharkút, Bakony Mountains, Hungary)". Annales de Paléontologie. 102 (2): 123–134.

Szabó, Márton; Ősi, Attila (September 2017). "The continental fish fauna of the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Iharkút locality (Bakony Mountains, Hungary)". Central European Geology. 60 (2): 230–287.

Szentesi, Zoltán; Venczel, Márton (April 2012). "A new discoglossid frog from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) of Hungary". Cretaceous Research. 34: 327–333.

Szentesi, Zoltán; Gardner, James D.; Venczel, Márton (March 2013). "Albanerpetontid amphibians from the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) of Iharkút, Hungary, with remarks on regional differences in Late Cretaceous Laurasian amphibian assemblages". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 50 (3): 268–281.

Virág, Attila; Ősi, Attila (2017-04-27). "Morphometry, Microstructure, and Wear Pattern of Neornithischian Dinosaur Teeth From the Upper Cretaceous Iharkút Locality (Hungary)". The Anatomical Record. 300 (8): 1439–1463.

Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Cretaceous, Europe)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 588-593.

Zoltán Szentesi and Márton Venczel (2010). "An advanced anuran from the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) of Hungary". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 256 (3): 291–302.

#Pneumatoraptor#Pneumatoraptor fodori#Paravian#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Prehistoric Life#Prehistory#Paleontology#Feathered Dinosaurs#Cretaceous#Omnivore#Eurasia#Maniraptoran#Terrestrial Tuesday

149 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Free STL 40 mya Coprolite, Turtle Fossil Feces (Poop) ・ Cults)

0 notes

Text

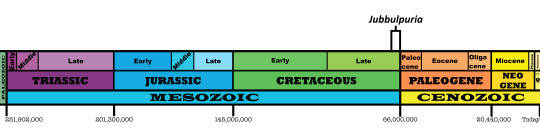

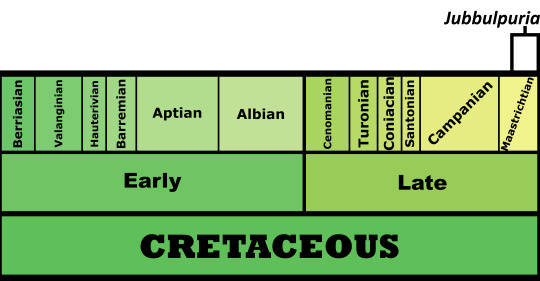

Jubbulpuria tenuis

By Scott Reid

Etymology: The One from Jubbulpore

First Described By: Huene & Matley, 1933

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Ceratosauria

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 70 and 66 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

Jubbulpuria is known from the Lameta Formation of Central India

Physical Description: Jubbulpuria is a poorly known dinosaur - a dubious genus, even! - Known from only a fragment of some vertebrae. These vertebrae are poorly preserved, but they indicate Jubbulpuria was some sort of dinosaur - probably a theropod, the group of bipedal carnivorous dinosaurs from which birds evolved. The latest research on this dinosaur indicates its a Ceratosaur, the least-birdy group of theropods, and given the small size of the vertebrae it probably was a smaller one, so more likely than not, a Noasaurid - the small, slender group of Ceratosaurs. Still, without more fossils it’s difficult to say either way. It probably would have been a smaller, slenderer dinosaur, and as such, covered in protofeathers of some sort.

Diet: Jubbulpuria was probably a carnivore, though it might have also eaten fish.

Behavior: The behavior of Jubbulpuria is difficult to glean, given it is only known from limited remains that don’t indicate what kind of dinosaur it was, but it was probably a fairly active animal.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Lameta Formation was a tropical lagoon environment, surrounded by dense vegetation. This plant material included a variety of algae, ferns, conifers, flowers, and - most interestingly - grass! Yup, the Lameta environment used to be one of our earliest fossil sites for grasses, indicating that grass was present and a major component of this lagoon system (though it wouldn’t have been a grassland in the modern sense). Now, of course, we’ve found more fossil evidence indicating grass evolved even earlier, and that many ornithopods were evolved to eat it; that being said, grass still didn’t become a major component of the environment until the Paleogene-Neogene transition in the Cenozoic. The grasses present in the Lameta were actually primarily kinds of rice - and were fed upon extensively by titanosaurs!

Many different kinds of animals were present in the Lameta alongside Jubbulpuria. There were snakes like Sanajeh and Madtsoia, and turtles such as Shweboemys and Carteremy. There were also a lot of fish, including sharks, in that ancient lagoon system. There were many kinds of dinosaurs as well - other smaller, slender Ceratosaurs like Jubbulpuria such as Compsosuchus, Laevisuchus, and Coeluroides; larger carnivores like the well-known abelisaurids Rajasaurus, Rahiolisaurus, and Indosuchus - and poorly known, but probably also Abelisaurids such as Lametasaurus, Indosaurus, Dryptosauroides, Ornithomimoides, and Orthogoniosaurus; giant titanosaurs such as Jainosaurus, Isisaurus, Titanosaurus, Antarctosaurus, and Laplatasaurus; and the dubious ankylosaur Brachypodosaurus! This ecosystem existed right up until the end-Cretaceous extinction, and is - indeed - an example of an environment from that ecosystem that isn’t like Late Cretaceous North America, but a whole heck of a lot weirder.

Other: Jubbulpuria may have been about 1.2 meters long, but I find that circumspect given the whole crappily known thing.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Carrano, M. T., and S. D. Sampson. 2008. The phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6(2):183-236

Carrano, M. T., M. A. Loewen, and J. J. W. Sertich. 2011. New materials of Masiakasaurus knopfleri Sampson, Carrano, and Forster, 2001, and implications for the morphology of the Noasauridae (Theropoda: Ceratosauria). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 95.

Ghosh, P., S. K. Bhattacharya, A. Sahni, R. K. Kar, D. M. Mohabey, K. Ambwani. 2003. Dinosaur coprolites from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Lameta Formation of India: isotopic and other markers suggesting a C3 plant diet. Cretaceous Research 24 (6): 743 - 750.

Huene, F. von, 1932, Die fossile Reptil-Ordnung Saurischia, ihre Entwicklung und Geschichte: Monographien zur Geologie und Palaeontologie, 1e Serie, Heft 4, pp. 1-361

Huene, F. von, and C. A. Matley, 1933, "The Cretaceous Saurischia and Ornithischia of the Central Provinces of India", Palaeontologica Indica (New Series), Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India 21(1): 1-74

Khosla, A., K. Chin, H. Alimohammadin, D. Dutta. 2015. Ostracods, plant tissues, and other inclusions in coprolites from the Late Cretaceous Lameta Formation at Pisdura, India: Taphonomical and palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 418: 90 - 100.

Prasad, V., C.A.E. Strömberg, A.D. Leaché, B. Samant, R. Patnaik, L. Tang, D.M. Mohabey, S. Ge & A. Sahni. 2011. Late Cretaceous origin of the rice tribe provides evidence for early diversification in Poaceae. Nature Communications 2: 480.

Sharma, N., R. K. Kar, A. Agarwal, R. Kar. 2005. Fungi in dinosaurian (Isisaurus) coprolites from the Lameta Formation (Maastrichtian) and its reflection on food habit and environment. Micropaleontology 51 (1): 73 -82.

Shukla, U. K., R. Srivastava. 2008. Lizard eggs from Upper Cretaceous Lameta Formation of Jabalpur, central India, with interpretation of depositional environments of the nest-bearing horizon. Creetaceous Research 29 (4): 674 - 686.

Sonkusare, H., B. Samant, D. M. Mohabey. 2017. Microflora from sauropod coprolites and associated sediments of Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Lameta Formation of Nand-Dongargaon basin, Maharashtra. Journal of the Geological Society of India 89 (4): 391 - 397.

Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loueff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth M.P.; Noto, Christopher N. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 517–606.

#Jubbulpuria tenuis#Jubbulpuria#Ceratosaur#Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Carnivore#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Mesozoic Monday#India and Madagascar#Cretaceous#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rhamphorhynchus longicaudus, R. muensteri, R. etchesi

By Chris Masnaghetti, retrieved from http://www.pteros.com/, a website dedicated to education about Pterosaurs.

A reminder that we will not be able to do every pterosaur until we reach $240 in donations on our patreon, so please donate even a dollar if you can.

Name: Rhamphorhynchus longicaudus, L. muensteri, R. etchesi

Name Meaning: Beak Snout

First Described: 1846

Described By: Meyer

Classification: Classification: Avemetatarsalia, Ornithodira, Pterosauromorpha, Pterosauria, Macronychoptera, Novialoidea, Breviquartossa, Rhamphorhynchidae, Rhamphorhynchinae

Have you ever wondered, hmm, I wonder what the best known pterosaur is, then you’ve come to the right place. Say hello to Rhamphorhnychus, a genus known from a truly astonishing number of specimens, that has allowed us to piece together much of its life history and ecology. It lived in the Late Jurassic of Europe, about 150.8 to 148.5 million years ago in the Tithonian age, and while fragmentary skeletons are found in various places throughout Europe, it’s most famous home is the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany. Many of its remains are complete and articulated, with some that are soft tissue, others three dimensional, and we have a complete ontogenetic sequence. There’s even coprolites known! It had a wingspan of about 1.5 to 1.8 meters long as an adult, and it had fairly narrow wings as well.

By Henry Thomas on @raptorcivilization

Rhamphorhynchus also had conical teeth that were fairly large and sticking out of its mouth, upturned jaw tips, and a long tail with a vane at the end that is at least confirmed - other pterosaurs are restored with this vane, but it’s uncertain if they really had them. Rhamphorhynchus thus used its large teeth to catch fish - it was decidedly a piscivore, with remains known from the guts from multiple specimens. One Rhamphorhynchus even swallowed a fish nearly as long as its own body, which would have lead to the pterosaur extending its throat just to get the slimy thing down (like modern crocodilians and birds can do). Small fish are also known to have been consumed by Rhamphorhynchus. As for the coprolites? They might indicate that Rhamphorhynchus also ate cephalopods, but this is fairly speculative at this time.

By John Conway, CC BY-SA 3.0

Despite being frequently shown doing so, Rhamphorhynchus was not a skim feeder - doing so would have ripped its jaw from its body. It also held its head parallel to the ground, allowing it balance itself as it flew. However it probably did most of its foraging while swimming, using its broad and large feet to propel itself through the water - and it being able to swim would have lead to it being preserved a fairly frequent number of times. It also was food for other things, of course - crocodylomorphs perhaps, but also possibly the predatory fish Aspidorhynchus acutirostris, which is much larger than Rhamphorhynchus and has been found associated with it in multiple specimens, including one that preserves the wing membranes of the pterosaur. The number of specimens with these two associated together indicates that Aspidorhynchus was routinely feeding on Rhamphorhynchus, and that oftentimes this predatory behavior would lead to their dying together in anoxic and other inhospitable regions of the lagoons, thus leading to excellent preservationg.

Infant by Henry Thomas on @raptorcivilization

It’s growth sequence is well known as well, and quite interesting: though there is no evidence that Rhamphorhynchus cared for its young, and the smallest individuals at 290 mm long were probably able to fly - though not like the adults, leading to questions as to their ecological role. It is possible that juveniles would have climbed trees and branches like hoatzin chicks, eating small arthropods. The juveniles had shorter skulls and larger eyes, and blunter aws, with shallower vanes on the tail - the vane would become diamond shaped as they grew and then triangular in the oldest adults. The number of teeth would not change as they grew, though the shape of the jaws would. They grew fast in the first few years of life and then growth would slow down after reaching sexual maturity, and though they grew faster than alligators, they still showed different growth patterns than more derived pterosaurs such as Pteranodon. They don’t reach a determined size, like endothermic animals, but whether or not they were ectothermic is uncertain.

By ДиБгд, in the Public Domain

Rhamphorhynchus lived in an environment with many lagoons and marine ecosystems, feeding on ocean going fish and being fed on by fish itself - it was, essentially, a Mesozoic Gull. It may have been more aquatic than any other pterosaurs, leading to its decent preservation, but was definitely a common sight in Late Jurassic Germany. As for animals it lived alongside, these included many invertebrates and fish, but also many types of lizards, tuatara-relatives, and turtles, as well as the Crocodylomorphs Alligatorellus, Cricosaurus, Dakosaurus, Geosaurus, and Rhacheosaurus, Ichthyosaurs such as Aegirosaurus, other pterosaurs like Scaphognathus, Pterodactylus, Germanodactylus, Ctenochasma, Cycnorhamphus, Gnathosaurus, Anurognathus, Ardeadactylus, Aurorazhdarcho, and Aerodactylus, and even some dinosaurs - specifically, Compsognathus and Archaeopteryx.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhamphorhynchus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paleobiota_of_the_Solnhofen_Formation

http://markwitton-com.blogspot.com/2016/04/the-lives-and-times-of-flying-reptiles.html

http://www.pteros.com/pterosaurs/rhamphorhynchus.html

Shout out goes to @plasterxxx!

#rhamphorhynchus#pterosaur ptuesday#pterosaur#rhamphorhynchid#palaeoblr#Rhamphorhynchus longicaudus#rhamphorhynchus muensteri#rhamphorhynchus etchesi#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#science#nature#factfile

112 notes

·

View notes