#Weaver of History

Text

Red Fox

#astrea#original character#markers#illistration#comic style#artwork#fantasy book#demon#half demon#half breed#half angel#archangel#seraphim#drawing#enemies to lovers#my original writing#horns#the fox#red wolf#weaver of history#red head

0 notes

Text

Hiking to see Weavers Needle.

Arizona

1988

#vintage camping#campfire light#arizona#dalmation#dogs of tumblr#history#hiking#weavers needle#travel#1980s

518 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alien ticket from Japan, 1979.

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

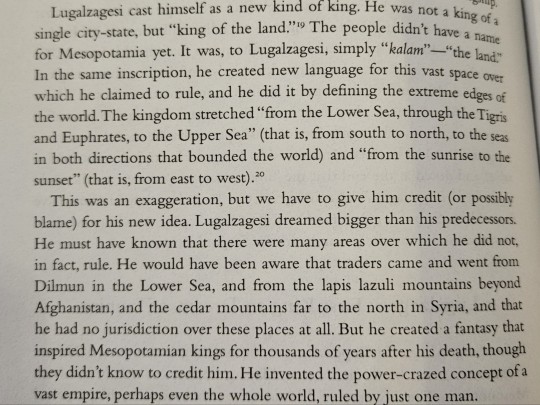

Wildly amusing to me that we apparently literally know the name of the guy who invented imperialism.

Feel like we should hate him more. Use his name for demons and monsters in fantasy novels. Have a holiday about how shitty he was. That kinda thing. Just on general principle, you know?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I was going through my great grandfather's memoirs (born 3 March 1880) and came across this part, which feels eerily similar to our current times:

Our biggest handicap was the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. With men off sick we were lucky to have 50 staff. Some would come back and more would go off. I was off two weeks myself. There were many deaths in the city.

The war was over and the men were returning from France. We were working a fifty hour week. With the men returning, the trend was to repress wages and frown on a reduction of working hours. My responsibility had been increased so as I was next to the superintendent. This was fine, except my wages were the same as the day I started. They said, "You are doing a good job, but with the men returning that is all we can pay you." There was general upset. The returned men were dissatisfied with the wages offered, not only with our company and the warehouse business, but with what was being offered in general.

He then goes on to explain how they met with the Trade and Labour Council to form a union and present their demands (which were union recognition, basic wage of $180.00 a month, an eight hour day in a year's time, and a two year contract), but it all went to hell because of spies reporting back to the bosses and scabs who refused to honour the strike.

After the second day they flooded back like sheep. At Ashdown the travellers and buyers worked the warehouse without interruption of service. The strike was a washout. I was out of a job!

The night before the strike was scheduled to start the bosses even resorted to the closest they had to social media 105 years ago.

The Evening paper carried an advertisement, by all companies concerned, advising that all employees absent from work for three days, would be discharged.

(The memoirs are 180 typed pages, so I may post more bits as they catch my eye)

#Canadian history#strike#solidarity#history is an ever repeating cycle#personal#memoirs#Great grandpa was an awesome dude#absolute badass#unrelated but his grandfather - so my great great great grandfather?#was a WEAVER in the New England States woolen mills before they moved to Canada in the 'early part of the nineteenth century'

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hot Take:

Wildbow’s choice to make Taylor ontologically weevil was NOT okay even in 2011!!!

#how many scrawny nerds have suffered#they are tired of history attributing them to being pure weevil!#parahumans#wildbow#worm#worm web serial#taylor hebert#skitter#weaver#Khepri#weevil

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

"oh people in the past would have all had their autistic relatives killed/abandoned/institutionalised"

okay then a) how are we still here and b) who the fuck do you think was copying out all those manuscripts

#autism stuff#i'm not saying NONE of us were treated badly#i just don't think people universally went 'time to lock away my sister for being too weird'#sometimes she would have been a nun!#or a weaver!#or silently looking after the chickens!#people in history did actually love and care for their disabled family members

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you guys see what I see???? OMG Sigourney would be a great choice for playing older Catherine of Aragon (or like I prefer saying, in the original Spanish, Catalina de Aragón)

#꒰ა victória speaks ໒꒱#avatar fandom#sigourney weaver#catalina de aragon#catherine of aragon#tudor era#tudor history#the tudors#avatar 2009#avatar twow#avatar the way of water#james cameron#james cameron avatar#avatar james cameron

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

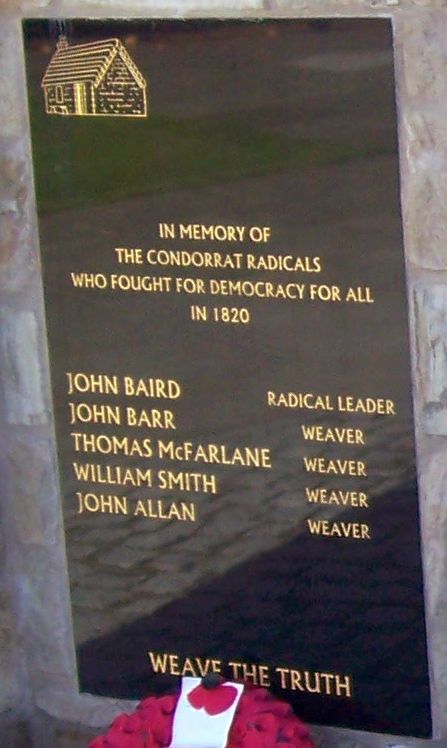

On 5th April 1820 government forces defeated Radical weavers at what became known as the Battle of Bonnymuir.

The ‘Radical Rising’ or ‘Radical War’ of 1820, also known as the Scottish Insurrection of 1820, was a week of strikes and unrest in Scotland that culminated in the trial of a number of ‘radicals’ for the crime of treason. It was the last armed uprising on Scottish soil, with the intent of establishing a radical republic.

Based in Central Scotland, artisan workers (such as weavers, shoemakers, blacksmiths), initiated a series of strikes and social unrest during the first week of April 1820. This pushed for government reform, in response to the economic depression. The Rising was quickly, and violently, quashed, and the subsequent trials took place in Scotland from July to August 1820.

The events of the Rising followed years of economic recession after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and considerable revolutionary instability on the European continent. As the economic situation worsened for many workers, societies sprung up across the country which espoused radical ideas for fundamental change.

In the early nineteenth century, Scottish politics offered power to very few people. Councillors on the Royal Burghs at this time were not elected to their position, rich landowners controlled county government and there were fewer than 3,000 parliamentary voters in the whole of Scotland, hardly a democracy.

It was recognised that the key to change was electoral reform, and the events of the American Revolution of 1776 and French Revolution of 1789 helped to promote these ideas. Radical reformers began to seek the universal franchise (for men), annual parliaments, and the repeal of the Act of Union of 1707.

Between 1st and 8th April 1820, across central Scotland, some works stopped, particularly in weaving communities, and radicals attempted to fulfil a call to rise. Several disturbances occurred across the country, perhaps the worst of which were the events at Bonnymuir, Stirlingshire, where a group of about 50 radicals clashed with a patrol of around 30 soldiers, while Bonnymuir is the most famous, or should I say infamous of the events during this period, it was by no means the only “uprising”

On Monday April 3rd a strike took force across a wide area of Scotland including Stirlingshire, Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire, with an estimated total of around 60,000 stopping work.

Reports were made of men carrying out military drill in Glasgow while foundries and forges had been raided, and iron files and dyer's poles taken to make pikes. In Kilbarchan soldiers found men making pikes, in Stewarton around 60 strikers was dispersed, in Balfron around 200 men had assembled for some sort of action. Pikes, gunpowder and weapons called "wasps" (a sort of javelin) and "clegs" (a barbed shuttlecock to throw at horses) were offered for sale.

In Glasgow John Craig led around 30 men to make for the Carron Company ironworks in Falkirk, telling them that weapons would be there for the taking, but the group were scattered when intercepted by a police patrol. Craig was caught, brought before a magistrate and fined, but the magistrate paid his fine for him.

Rumours spread that England was in arms for the cause of reform and that an army was mustering at Campsie commanded by Marshal MacDonald, a Marshal of France and son of a Jacobite refugee family, to join forces with 50,000 French soldiers at Cathkin Braes under Kinloch, the fugitive "Radical laird" from Dundee.

Government troops were ready in Glasgow, including the Rifle Brigade, the 83rd Regiment of Foot, the 7th and 10th Hussars and Samuel Hunter's Glasgow Sharpshooters. In the evening 300 radicals briefly skirmished with a party "of cavalry", but no one came to harm.

The next day, Tuesday April 4th, Duncan Turner assembled around 60 men to march to Carron, while he carried out organising work elsewhere. Half the group dropped out, however the remaining twenty five, persuaded that they would pick up support along the way, set out under the leadership of Andrew Hardie. They arrived in Condorrat, which was on the way to Carron, at 5am on April 5th. Waiting for them was John Baird who had expected a small army, not this bedraggled and soaking wet group. He was persuaded to continue the March to Carron by John King, who would himself go ahead and gather supporters. King would go to find supporters at Camelon while Baird and Hardie were to leave the road and wait at Bonnymuir.

What the leaders didn’t know is that the Government had placed spies and agitators among the crowds and they were lured to the confrontation with well-armed, trained soldiers on Bonnymuir,

The authorities at Kilsyth and Stirling Castle had however been alerted and Sixteen Hussars and sixteen Yeomanry troopers had been ordered on 4 April to leave Perth and go to protect Carron. They left the road at Bonnybridge early on April 5th and made straight for the slopes of Bonnymuir. As the newspapers subsequently reported:

"On observing this force the radicals cheered and advanced to a wall over which they commenced firing at the military. Some shots were then fired by the soldiers in return, and after some time the cavalry got through an opening in the wall and attacked the party who resisted till overpowered by the troops who succeeded in taking nineteen of them prisoners, who are lodged in Stirling Castle. Four of the radicals were wounded".

The Glasgow Herald mocked the small number of radicals encountered, but worried that "the conspiracy appears to be more extensive than almost anyone imagined... radical principles are too widely spread and too deeply rooted to vanish without some explosion and the sooner it takes place the better."

The end of the Rising

On the afternoon of April 5th, before news of the Bonnymuir fighting got out, Lees sent a message asking the radicals of Strathaven to meet up with the "Radical laird" Kinloch's large force at Cathkin. The next morning a small force of 25 men followed the instructions and left at 7 a.m. to march there. Among them was the experienced elderly Radical James Wilson who is claimed to have had a banner reading "Scotland Free or a Desart"

At East Kilbride they were warned of an army ambush, and Wilson, suspecting treachery, returned to Strathaven. The others bypassed the ambush and reached Cathkin, but as there was no sign of the promised army they dispersed. Ten of them were identified and caught, and by nightfall on April 7th; they were jailed at Hamilton.

I’ll leave things there for the moment, the aftermath will be told in further posts, one in a few days, and more as the ringleaders were made examples of as they were tried for their parts in the events.

The large memorial stone to mark the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Bonnymuir was unveiled in April 2021.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suggested song

youtube

"The Frozen Logger" The Weavers, 1951

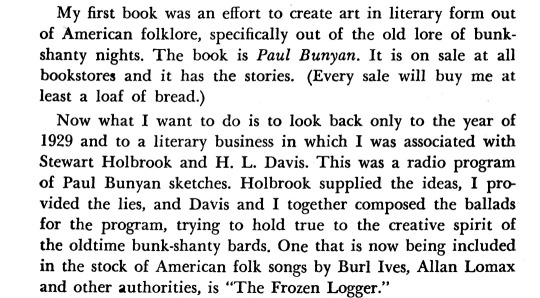

"The Frozen Logger" was originally written and performed in 1929 by Jim Stevens (the man who popularized the folk legend Paul bunyan in his 1925 book "Paul Bunyan"

for his program on the ABC seattle network "The Histories of Paul Bunyan"

here's a segment of Jim Stevens talking about that himself:

Oregon Historical Quarterly Vol. 50, No. 4 (Dec., 1949) pp.235-242

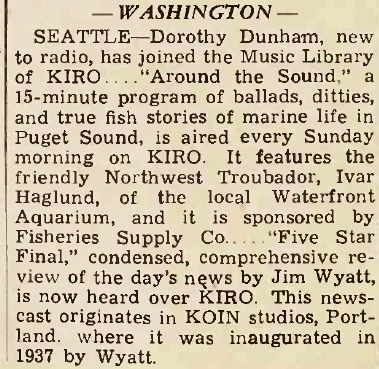

it's possible that the song was performed by Ivar Haglund (notable for his prolific seafood themed songs and clam restaurant) in the early to mid 1940s on his radio show "Around the Sound" where he would sing folk music for 15 minutes, and I found a couple sources listing him as either the copyright owner of the song, or the writer (he did not write the song). He was friends with Jim Stevens, and it's likely that Stevens taught him the song.

Radio Daily, July 1944 and KJR flyer, 1942

Many secondhand sources mentioned that "The Frozen Logger" was based on an old tune or an old ballad, with words that were originally written by Jim Stevens, including Jim Stevens himself though he's not specific. I think i might be the first person ever to point out that the ballad it was based on belongs to the folk song family of "The Unfortunate Rake"/ "The Unfortunate Lad" (recorded here in the 1960s and performed by A.L. Lloyd) it has a similar story structure, similar characters, similar rhymes, and similar composition.

in " 'The Unfortunate Rake' and His Descendants" by Kenneth Lodewick, the original song is dated as being from ireland in 1790, and one of its earliest printings was in England in 1850 as a folk ballad

as you might be able to guess if you're familiar with cowboy ballads, this song is also the origin of "Streets of Laredo" or "The cowboys lament" which emerged in the late 1800s from cowhand workers. A cowhand in the late 1870s named Frank H. Maynard has claimed to write the song in 1876 and published his version in "Cowboy's Lament: A Life on the Open Range" in 1911 after it was published in Alan Lomax's "Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads" in 1910. in my opinion, i think this song could have multiple origins.

the oldest recording i could find was by Harry McClintock in 1928

as an aside, there was also ANOTHER lumberjack version of the song collected by John C. French called "The Wild Lumberjack" from Pennsylvania logging camps dated between 1870-1904/1905. performed here by Kenneth S Goldstein (1960s). This song isn't the origin of "The Frozen Logger" but it's interesting that there are two songs like this.

I believe that "The Frozen Logger" is an adaptation from the cowboy version. Jim Stevens grew up in Idaho and worked in Montana (where he mentions learning many songs) and in 1959, he gave an interview with Ivar Harglund about how he used traditional folk and country music and created new and topical lyrics for the Keep Washington Green Campaign in the 1940s

The first ever publishment and recording (That I could find) of "The Frozen Logger" was in 1947 by Earl Robinson in his Keynote Album, commented upon by the Chicago star by Raeburn Flerlage that same year.

The Chicago Star (Chicago, III.) April 5, 1947 (p.13). Library of Congress

Pete seeger, one of the Weavers, was (for some reason that escapes me) friends with Ivar Haglund (who was friends with Jim Stevens) and, like with the song "the Old Settler" , it is likely that Haglund taught the song to Pete Seeger who then, with the rest of the Weavers, performed it in 1951, popularizing the song.

for @slowtraincumming

#Youtube#Jim Stevens#ivar haglund#harry Mcclintock#alan lomax#pete seeger#the weavers#Frank H Maynard#paul bunyan#cowboy ballads#traditional folk#folk history#american folk#the unfortunate rake#american history#folklore#oregon#Washington#american folk revival#folk#suggested songs

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#rumbelle#anyelle#weaver x hierophant#the hierophant#detective weaver#my creations#my edits#my moodboards#I'm not sure I ship these two but when I saw those two photos of them I thought they might look like one scene... and the rest is history 😅

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝛱𝜀𝜀𝜕 𝛼 𝐿𝜄𝑔𝘩𝜏𝜀𝑟?

Just my oc Astrea, inspired by tomking_tk

#astrea#drawing#comicstyle#markers#enemies to lovers#demon#half angel#my original writing#horns#half demon#seraphim#archangel#half breed#illustration#princess of Vahrahnas'y#princess of Njzwah#princess of Kashir#the One in the Shadow#Weaver of History#my original characters#original character#original story#the Fox

1 note

·

View note

Text

Portrait of Countess A.S. Protasova with her Nieces - Angelica Kauffmann (detail) // Gabrielle and Jean - Pierre-Auguste Renoir (detail) // Maternal Affection - Hugues Merle (detail) // Children - Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (detail) // Traveling Song - Ryn Weaver

#angelica kauffmann#pierre auguste renoir#renoir#hugues merle#traveling song#the fool#the fool album#the fool ryn weaver#ryn weaver#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Fred Hellerman and Jean Ritchie in the WNYC studios, 1949

#pete seeger#woody guthrie#Jean Ritchie#the weavers#folk music#folk#appalachian music#history#music#music history#dulcimer#banjo#folk revival#1940s

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah that's a name that tells a story.

864 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 10, 1898, a white mob seized four Black people from a jail in Clarendon, Arkansas, and lynched them before they could stand trial.

A few weeks prior, a white woman named Erneze Orr allegedly hired Will Sanders, Rilla Weaver, Dennis Ricord, and Manse Castle to kill her husband, John T. Orr. After Mr. Sanders, Ms. Weaver, Mr. Ricord, and Mr. Castle were arrested for this alleged offense, a mob of white community members quickly formed—and on three separate occasions, the mob convened at the jail intent on lynching them. Despite these repeated threats, officers refused to move the group to a safer location as they awaited trial.

On August 10, the white mob stormed the jail a final time. Rather than protecting the people in his custody, the sheriff turned the jail keys over to the mob. Newspapers reported that he had been persuaded to open the jail doors and let the mob enter “by their earnestness.”

Mrs. Orr, the white woman who allegedly orchestrated her husband’s murder, was also being held at the jail. She reportedly poisoned herself shortly before the mob’s arrival. Though contemporary reports note that she was still alive when the mob stormed the jail, the mob left her and took only the four Black people from the jail.

The mob hung Mr. Sanders, Ms. Weaver, Mr. Ricord, and Mr. Castle from the tramway of a nearby sawmill with signs affixed to them that read “This is the penalty for murder and rape.” Their bodies were then left on display for hours to terrorize the entire Black community.

During this era of racial terror, mere suggestions of Black-on-white violence could provoke mob violence and lynching before the judicial system could or would act. The deep racial hostility permeating Southern society often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was discovered, whether or not there was evidence to support the suspicion. Even in situations like this case, where a white person was believed to be the orchestrator of the violence, accusations lodged against Black people were rarely subject to serious scrutiny. White lynch mobs regularly displayed complete disregard for the legal system, abducting Black people from courts, jails, and out of police custody. Law enforcement officials, charged with protecting those in their custody, often failed to intervene, as was the case here.

Mr. Sanders, Ms. Weaver, Mr. Ricord, and Mr. Castle were four of at least 493 documented lynching victims between 1877 and 1950 in the state of Arkansas. To learn more about the history of racial terror lynching, read EJI’s report, Lynching in America.

#history#white history#us history#am yisrael chai#jumblr#black history#democrats#republicans#white mob#Clarendon#Arkansas#white supremacy#bigot#racist#white men#white man#Will Sanders#Rilla Weaver#Dennis Ricord#Manse Castle#white woman#white women#Erneze Orr#all cops are bastards#dirty cops#bad cops#cops#cop#defund the police#bad police

2 notes

·

View notes