#african traditional medicine

Photo

Sacred Seeds Doulas are a Black Doula Collective in Colorado, who provide physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and informational support to community members.

They are equipped to provide clients with culturally relevant, holistic care, and advocacy. The expertise of their doulas includes fertility, prenatal, labor/birth, postpartum, nutrition, energy work, lactation counseling, massage therapy, maternal mental health, bereavement, abortion, and end of life care.

They are a program within the Soul 2 Soul Sisters organization, a Womanist, Reproductive Justice organization.

“As the medical industrial complex and all authoritarian, undemocratic, institutions continue to be delegitimized, we must reclaim our power and continue to be in solidarity with Black pregnant people, Black Doulas, Black midwives, Black healers, Black rootworkers, Black herbalists, Black farmers, Black/African traditional doctors, and Black community members on the frontlines of Reproductive Justice #AbolitionNow”—Detroit Radical Childcare Collective

Be in Ujima Umoja with Sacred Seeds Doulas here.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

also said it about a million times before. but this idea that "science" is inherently incompatible with the nonwestern world bc it is inherently western is not only outright bogus but racist and especially more noble savage shit

the west did not invent science. the west was very very far from being the only place on this planet to have an insanely complex understanding of the solar system, of very complex medicine (western europeans learned how to perform c-sections from africans btw), of traditional medicine, or mathematics and physics, and whatever else

#fucks sake the west still has like no idea why so much of traditional chinese medicine practices Very Clearly Work#and western euro doctors bothched about a million c-sections before they got it right while african women had very high rates of success#also#the islamic golden age?? hello

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is like, my third tumblr. i was going to use this one as a lowkey blog where i shared beautiful things to an extremely small audience. but after like a year of zero posts, i decided to make this tumblr account more seamless with my other Skin Priestess/Ubasti social media accounts.

xoxo, Jourdan

#skin priestess#licensed esthetician#black esthetician#black skincare#skincare#esthetics#sidereal astrology#art history#african traditional religions#hoodoo#rootwork#conjure#venusian#occult#wellness#health and beauty#herbalism#herbal medicine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlock the Wonders of African Herbal Medicine with Dr. Muchindu, the Renowned Traditional Healer.

Unlock the Wonders of African Herbal Medicine with Dr. Muchindu, the Renowned Traditional Healer

Call Dr Now

WhatsApp NOW

Contact Dr. Tonga Muchindu

Call 📱 +254700807659

Whatsapp +254700807659

Unlock the Wonders of African Herbal Medicine with Dr. Muchindu, the Renowned Traditional Healer

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Roots & Futures: The Afro American Wellness Journey

Introduction

In the heart of urban landscapes across America, a powerful movement is taking root among African American communities—a resurgence of ancestral health practices that promise not just physical well-being, but profound healing benefits, energy renewal, and a deeper connection with love. This revival pays homage to the rich heritage of African ancestral traditions, adapting them to the rhythm of modern urban life. As we delve deeper into the essence of urban ancestral health, we uncover a holistic approach to wellness that intertwines the physical, emotional, and spiritual, offering transformative benefits that have stood the test of time.

Historical Context and Relevance

The journey of African American health practices is a testament to resilience and adaptability. Traditionally, African ancestors relied on a deep understanding of nature and spirituality to maintain health and heal ailments. This wisdom, passed down through generations, was not just about curing diseases but fostering a harmonious balance between the body, mind, and spirit. The great migration and urbanization presented new challenges and adaptations for these practices. Yet, the essence remained—rooted in a profound connection with ancestral wisdom.

In urban environments, where the hustle and bustle can detach individuals from their roots, the relevance of ancestral health practices becomes even more pronounced. They serve as a bridge, connecting urban dwellers with their heritage, offering solace and healing in the concrete jungle. This link to the past empowers African Americans to reclaim a sense of identity and wellness that urban life often strips away.

Health Benefits

Ancestral health practices offer a holistic approach to physical well-being, emphasizing prevention and natural remedies. Central to this is the traditional diet, rich in whole foods, plants, and herbs, mirroring the eating habits of ancestors who consumed what the earth naturally provided. This diet is not just about nutrition; it's a form of medicine, reducing the risk of modern diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart conditions that disproportionately affect African Americans.

Herbal medicine, another cornerstone, utilizes plant-based remedies to treat and prevent illnesses. These natural concoctions, steeped in tradition, have been validated by modern science for their healing properties. For instance, the use of bitter leaf, moringa, and ginger in traditional remedies is now supported by research highlighting their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune-boosting effects.

Healing Benefits

Beyond physical health, ancestral practices offer profound mental and emotional healing. The African American tradition of storytelling, for example, serves as a powerful tool for emotional catharsis and resilience building. Sharing stories of struggle, triumph, and hope within the community not only preserves historical memory but also fosters a sense of belonging and identity.

Community gatherings and traditional ceremonies provide a space for collective healing, allowing individuals to connect, share experiences, and support each other emotionally. These practices, deeply spiritual in nature, help heal the wounds of isolation, stress, and urban life, reinforcing the community's fabric and individual's sense of self-worth and belonging.

Energy and Love

The concept of energy in ancestral health practices transcends the physical, encompassing spiritual and emotional dimensions. Practices such as meditation, yoga (with roots in ancient African spirituality), and dance are not just physical exercises but rituals that cultivate life energy, or "chi," promoting harmony and balance within and with the world.

Love, in the context of ancestral health, is both self-love and communal love. It manifests through practices that nurture the soul, affirm one’s identity, and reinforce connections with others and ancestors. This sense of love and belonging is fundamental for mental health, combating the feelings of alienation that can prevail in urban environments.

Modern Adaptations and Incorporations

In today’s urban settings, African Americans are ingeniously adapting these ancestral practices to fit contemporary lifestyles. Urban gardens and farms reclaim the tradition of growing one’s own food, connecting with the earth, and fostering community through shared spaces. Workshops and social media platforms have become modern-day storytelling circles, spreading knowledge of herbal remedies, traditional recipes, and healing practices, making them accessible to a wider audience.

Call to Action (CTA)

As we embrace the wisdom of our ancestors, let us integrate their practices into our daily lives, enriching our health, healing, energy, and love. Share your stories, explore traditional remedies, and join community gatherings. Let’s foster a movement towards holistic well-being, grounded in the rich heritage of ancestral health practices.

We invite you to comment below with your experiences or ancestral practices you’ve found beneficial. Follow us on social media and sign up for our newsletter for more insights into ancestral health. Together, let's embark on a journey of healing, empowerment, and connection.

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration of "Roots & Futures: The Afro American Wellness Journey," it's clear that the legacy of our ancestors provides a profound blueprint for holistic health and well-being. This journey from the ancestral lands of Africa to the urban landscapes of America has not only preserved a rich heritage of natural remedies, dietary wisdom, and spiritual practices but has also adapted these traditions to meet the challenges and opportunities of modern life.

The resilience and creativity of the African American community have ensured that these ancestral health practices continue to thrive, blending seamlessly with contemporary wellness movements. By embracing the lessons of the past, we unlock the potential for a healthier, more sustainable future. This journey underscores the importance of community, sustainability, and wellness as pillars of our collective well-being.

As we celebrate Afro American Month, let's commit to honoring our heritage by integrating these timeless practices into our daily lives. Whether through the foods we eat, the remedies we use, or the communities we build, we pay homage to our ancestors and their enduring wisdom. Together, we can create a legacy of health and wellness that will empower future generations.

"Roots & Futures" is more than just a reflection on the past; it's a call to action for the present and a vision for the future. It's a reminder that, in the tapestry of African American history, each of us has a role to play in weaving a healthier, more vibrant future. Let's carry forward the torch of ancestral wisdom, illuminating the path toward holistic health and wellness for all.

FAQ on Urban Ancestral Health Among African Americans

Q1: What is urban ancestral health?

Urban ancestral health refers to the practice of integrating traditional African health and wellness practices into modern urban lifestyles. It involves adapting ancestral knowledge of diet, herbal medicine, spiritual practices, and community engagement to improve physical, mental, and emotional well-being in the urban context.

Q2: How can urban dwellers incorporate ancestral health practices into their lives?

Urban dwellers can incorporate ancestral health practices by:

Adopting diets rich in whole, natural foods similar to those eaten by their ancestors.

Using herbal remedies for preventive health care and healing.

Engaging in traditional physical and spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and dance that connect with African roots.

Participating in community gatherings and storytelling sessions to strengthen communal bonds and mental health.

Q3: Are there any scientific studies supporting the benefits of ancestral health practices?

Yes, numerous scientific studies support the benefits of ancestral health practices. For example, research has highlighted the nutritional value of traditional diets, the effectiveness of herbal medicine in treating various ailments, and the positive impact of community and spiritual practices on mental health. These studies validate the holistic approach to wellness that ancestral practices promote.

Q4: Can these practices make a difference in communities facing health disparities?

Ancestral health practices have the potential to significantly impact communities facing health disparities by offering accessible, affordable, and culturally relevant ways to improve health outcomes. They encourage self-care, community support, and a return to natural, preventive health measures that can help address issues such as chronic diseases, mental health, and access to healthcare.

Q5: How can I learn more about my ancestral health practices?

Learning about ancestral health practices can start with:

Researching historical and cultural resources about African health traditions.

Talking with elders in the community who can share knowledge and experiences.

Participating in workshops, courses, or groups focused on traditional African health and wellness practices.

Exploring books, documentaries, and online platforms dedicated to ancestral health and African heritage.

Q6: Are there any risks associated with adopting ancestral health practices?

While many ancestral health practices offer benefits, it's important to approach them with care, especially when it comes to herbal medicine. Some herbs may interact with medications or be inappropriate for certain health conditions. It's advisable to consult with a healthcare professional, ideally one knowledgeable about traditional practices, before incorporating new health routines.

Q7: How can urban communities foster a greater connection to ancestral health practices?

Urban communities can foster a greater connection to ancestral health practices by:

Creating spaces for the sharing and practice of traditional health and wellness activities.

Organizing events and workshops that educate and engage community members in ancestral practices.

Supporting local urban gardens and farms that grow traditional foods and herbs.

Developing community programs that focus on holistic health, incorporating physical, mental, and spiritual well-being.

Lower health care costs.

#Urban Ancestral Health#African American Health Benefits#Traditional Healing Practices#Energy and Love in Ancestral Health#Ancestral Diets and Herbal Medicine.

0 notes

Text

youtube

#africa#african culture#africa news#africa travel#africa unite#african#youtube#medicine#traditional medicine#african beauty#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

in addition to being prone to an obvious naturalistic fallacy, the oft-repeated claim that various supplements / herbs / botanicals are being somehow suppressed by pharmaceutical interests seeking to protect their own profits ('they would rather sell you a pill') belies a clear misunderstanding of the relationship between 'industrial' pharmacology and plant matter. bioprospecting, the search for plants and molecular components of plants that can be developed into commercial products, has been one of the economic motivations and rationalisations for european colonialism and imperialism since the so-called 'age of exploration'. state-funded bioprospectors specifically sought 'exotic' plants that could be imported to europe and sold as food or materia medica—often both, as in the cases of coffee or chocolate—or, even better, cultivated in 'economic' botanical gardens attached to universities, medical schools, or royal palaces and scientific institutions.

this fundamental attitude toward the knowledge systems and medical practices of colonised people—the position, characterising eg much 'ethnobotany', that such knowledge is a resource for imperialist powers and pharmaceutical manufacturers to mine and profit from—is not some kind of bygone historical relic. for example, since the 1880s companies including pfizer, bristol-myers squibb, and unilever have sought to create pharmaceuticals from african medicinal plants, such as strophanthus, cryptolepis, and grains of paradise. in india, state-created databases of valuable 'traditional' medicines have appeared partly in response to a revival of bioprospecting since the 1980s, in an increasingly bureaucratised form characterised by profit-sharing agreements between scientists and local communities that has nonetheless been referred to as "biocapitalism". a 1990 paper published in the proceedings of the novartis foundation symposium (then the ciba foundation symposium) spelled out this form of epistemic colonialism quite bluntly:

Ethnobotany, ethnomedicine, folk medicine and traditional medicine can provide information that is useful as a 'pre-screen' to select plants for experimental pharmacological studies.

there is no inherent oppositional relationship between pharmaceutical industry and 'natural' or plant-based cures. there are of course plenty of examples of bioprospecting that failed to translate into consumer markets: ginseng, introduced to europe in the 17th century through the mercantile system and the east india company, found only limited success in european pharmacology. and there are cases in which knowledge with potential market value has actually been suppressed for other reasons: the peacock flower, used as an abortifacient in the west indies, was 'discovered' by colonial bioprospectors in the 18th century; the plant itself moved easily to europe, but knowledge of its use in reproductive medicine became the subject of a "culturally cultivated ignorance," resulting from a combination of funding priorities, national policies, colonial trade patterns, gender politics, and the functioning of scientific institutions. this form of knowledge suppression was never the result of a conflict wherein bioprospectors or pharmacists viewed the peacock flower as a threat to their own profits; on the contrary, they essentially sacrificed potential financial benefits as a result of the political and social factors that made abortifacient knowledge 'unknowable' in certain state and commercial contexts.

exploitation of plant matter in pharmacology is not a frictionless or infallible process. but the sort of conspiratorial thinking that attempts to position plant therapeutics and 'big pharma' as oppositional or competitive forces is an ahistorical and opportunistic example of appealing to nominally anti-capitalist rhetoric without any deeper understanding of the actual mechanisms of capitalism and colonialism at play. this is of course true whether or not the person making such claims has any personal financial stake in them, though it is of course also true that, often, they do hold such stakes.

537 notes

·

View notes

Text

JSTOR Articles on the History of Witchcraft, Witch Trials, and Folk Magic Beliefs

This is a partial of of articles on these subjects that can be found in the JSTOR archives. This is not exhaustive - this is just the portion I've saved for my own studies (I've read and referenced about a third of them so far) and I encourage readers and researchers to do their own digging. I recommend the articles by Ronald Hutton, Owen Davies, Mary Beth Norton, Malcolm Gaskill, Michael D. Bailey, and Willem de Blecourt as a place to start.

If you don't have personal access to JSTOR, you may be able to access the archive through your local library, university, museum, or historical society.

Full text list of titles below the cut:

'Hatcht up in Villanie and Witchcraft': Historical, Fiction, and Fantastical Recuperations of the Witch Child, by Chloe Buckley

'I Would Have Eaten You Too': Werewolf Legends in the Flemish, Dutch and German Area, by Willem de Blecourt

'The Divels Special Instruments': Women and Witchcraft before the Great Witch-hunt, by Karen Jones and Michael Zell

'The Root is Hidden and the Material Uncertain': The Challenges of Prosecuting Witchcraft in Early Modern Venice, by Jonathan Seitz

'Your Wife Will Be Your Biggest Accuser': Reinforcing Codes of Manhood at New England Witch Trials, by Richard Godbeer

A Family Matter: The CAse of a Witch Family in an 18th-Century Volhynian Town, by Kateryna Dysa

A Note on the Survival of Popular Christian Magic, by Peter Rushton

A Note on the Witch-Familiar in Seventeenth Century England, by F.H. Amphlett Micklewright

African Ideas of Witchcraft, by E.G. Parrinder

Aprodisiacs, Charms, and Philtres, by Eleanor Long

Charmers and Charming in England and Wales from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century, by Owen Davies

Charming Witches: The 'Old Religion' and the Pendle Trial, by Diane Purkiss

Demonology and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, by Sona Rosa Burstein

Denver Tries A Witch, by Margaret M. Oyler

Devil's Stones and Midnight Rites: Megaliths, Folklore, and Contemporary Pagan Witchcraft, by Ethan Doyle White

Edmund Jones and the Pwcca'r Trwyn, by Adam N. Coward

Essex County Witchcraft, by Mary Beth Norton

From Sorcery to Witchcraft: Clerical Conceptions of Magic in the Later Middle Ages, by Michael D. Bailey

German Witchcraft, by C. Grant Loomis

Getting of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials, by Alaric Hall

Ghost and Witch in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, by Gillian Bennett

Ghosts in Mirrors: Reflections of the Self, by Elizabeth Tucker

Healing Charms in Use in England and Wales 1700-1950, by Owen Davies

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?, by Ronald Hutton

Invisible Men: The Historian and the Male Witch, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Johannes Junius: Bamberg's Famous Male Witch, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Knots and Knot Lore, by Cyrus L. Day

Learned Credulity in Gianfrancesco Pico's Strix, by Walter Stephens

Literally Unthinkable: Demonological Descriptions of Male Witches, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Magical Beliefs and Practices in Old Bulgaria, by Louis Petroff

Maleficent Witchcraft in Britian since 1900, by Thomas Waters

Masculinity and Male Witches in Old and New England, 1593-1680, by E.J. Kent

Methodism, the Clergy, and the Popular Belief in Witchcraft and Magic, by Owen Davies

Modern Pagan Festivals: A Study in the Nature of Tradition, by Ronald Hutton

Monstrous Theories: Werewolves and the Abuse of History, by Willem de Blecourt

Neapolitan Witchcraft, by J.B. Andrews and James G. Frazer

New England's Other Witch-Hunt: The Hartford Witch-Hunt of the 1660s and Changing Patterns in Witchcraft Prosecution, by Walter Woodward

Newspapers and the Popular Belief in Witchcraft and Magic in the Modern Period, by Owen Davies

Occult Influence, Free Will, and Medical Authority in the Old Bailey, circa 1860-1910, by Karl Bell

Paganism and Polemic: The Debate over the Origins of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, by Ronald Hutton

Plants, Livestock Losses and Witchcraft Accusations in Tudor and Stuart England, by Sally Hickey

Polychronican: Witchcraft History and Children, interpreting England's Biggest Witch Trial, 1612, by Robert Poole

Publishing for the Masses: Early Modern English Witchcraft Pamphlets, by Carla Suhr

Rethinking with Demons: The Campaign against Superstition in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe from a Cognitive Perspective, by Andrew Keitt

Seasonal Festivity in Late Medieval England, Some Further Reflections, by Ronald Hutton

Secondary Targets: Male Witches on Trial, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Some Notes on Modern Somerset Witch-Lore, by R.L. Tongue

Some Notes on the History and Practice of Witchcraft in the Eastern Counties, by L.F. Newman

Some Seventeenth-Century Books of Magic, by K.M. Briggs

Stones and Spirits, by Jane P. Davidson and Christopher John Duffin

Superstitions, Magic, and Witchcraft, by Jeffrey R. Watt

The 1850s Prosecution of Gerasim Fedotov for Witchcraft, by Christine D. Worobec

The Catholic Salem: How the Devil Destroyed a Saint's Parish (Mattaincourt, 1627-31), by William Monter

The Celtic Tarot and the Secret Tradition: A Study in Modern Legend Making, by Juliette Wood

The Cult of Seely Wights in Scotland, by Julian Goodare

The Decline of Magic: Challenge and Response in Early Enlightenment England, by Michael Hunter

The Devil-Worshippers at the Prom: Rumor-Panic as Therapeutic Magic, by Bill Ellis

The Devil's Pact: Diabolic Writing and Oral Tradition, by Kimberly Ball

The Discovery of Witches: Matthew Hopkins' Defense of his Witch-hunting Methods, by Sheilagh Ilona O'Brien

The Disenchantment of Magic: Spells, Charms, and Superstition in Early European Witchcraft Literature, by Michael D. Bailey

The Epistemology of Sexual Trauma in Witches' Sabbaths, Satanic Ritual Abuse, and Alien Abduction Narratives, by Joseph Laycock

The European Witchcraft Debate and the Dutch Variant, by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra

The Flying Phallus and the Laughing Inquisitor: Penis Theft in the Malleus Maleficarum, by Moira Smith

The Framework for Scottish Witch-Hunting for the 1590s, by Julian Goodare

The Imposture of Witchcraft, by Rossell Hope Robbins

The Last Witch of England, by J.B. Kingsbury

The Late Lancashire Witches: The Girls Next Door, by Meg Pearson

The Malefic Unconscious: Gender, Genre, and History in Early Antebellum Witchcraft Narratives, by Lisa M. Vetere

The Mingling of Fairy and Witch Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Scotland, by J.A. MacCulloch

The Nightmare Experience, Sleep Paralysis, and Witchcraft Accusations, by Owen Davies

The Pursuit of Reality: Recent Research into the History of Witchcraft, by Malcolm Gaskill

The Reception of Reginald Scot's Discovery of Witchcraft: Witchcraft, Magic, and Radical Religions, by S.F. Davies

The Role of Gender in Accusations of Witchcraft: The Case of Eastern Slovenia, by Mirjam Mencej

The Scottish Witchcraft Act, by Julian Goodare

The Werewolves of Livonia: Lycanthropy and Shape-Changing in Scholarly Texts, 1550-1720, by Stefan Donecker

The Wild Hunter and the Witches' Sabbath, by Ronald Hutton

The Winter Goddess: Percht, Holda, and Related Figures, by Lotta Motz

The Witch's Familiar and the Fairy in Early Modern England and Scotland, by Emma Wilby

The Witches of Canewdon, by Eric Maple

The Witches of Dengie, by Eric Maple

The Witches' Flying and the Spanish Inquisitors, or How to Explain Away the Impossible, by Gustav Henningsen

To Accommodate the Earthly Kingdom to Divine Will: Official and Nonconformist Definitions of Witchcraft in England, by Agustin Mendez

Unwitching: The Social and Magical Practice in Traditional European Communities, by Mirjam Mencej

Urbanization and the Decline of Witchcraft: An Examination of London, by Owen Davies

Weather, Prayer, and Magical Jugs, by Ralph Merrifield

Witchcraft and Evidence in Early Modern England, by Malcolm Gaskill

Witchcraft and Magic in the Elizabethan Drama by H.W. Herrington

Witchcraft and Magic in the Rochford Hundred, by Eric Maple

Witchcraft and Old Women in Early Modern Germany, by Alison Rowlands

Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England, by Julia M. Garrett

Witchcraft and Silence in Guillaume Cazaux's 'The Mass of Saint Secaire', by William G. Pooley

Witchcraft and the Early Modern Imagination, by Robin Briggs

Witchcraft and the Western Imagination by Lyndal Roper

Witchcraft Belief and Trals in Early Modern Ireland, by Andrew Sneddon

Witchcraft Deaths, by Mimi Clar

Witchcraft Fears and Psychosocial Factors in Disease, by Edward Bever

Witchcraft for Sale, by T.M. Pearce

Witchcraft in Denmark, by Gustav Henningsen

Witchcraft in Germany, by Taras Lukach

Witchcraft in Kilkenny, by T. Crofton Croker

Witchcraft in Anglo-American Colonies, by Mary Beth Norton

Witchcraft in the Central Balkans I: Characteristics of Witches, by T.P. Vukanovic

Witchcraft in the Central Balkans II: Protection Against Witches, by T.P. Vukanovic

Witchcraft Justice and Human Rights in Africa, Cases from Malawi, by Adam Ashforth

Witchcraft Magic and Spirits on the Border of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, by S.P. Bayard

Witchcraft Persecutions in the Post-Craze Era: The Case of Ann Izzard of Great Paxton, 1808, by Stephen A. Mitchell

Witchcraft Prosecutions and the Decline of Magic, by Edward Bever

Witchcraft, by Ray B. Browne

Witchcraft, Poison, Law, and Atlantic Slavery, by Diana Paton

Witchcraft, Politics, and Memory in Seventeeth-Century England, by Malcolm Gaskill

Witchcraft, Spirit Possession and Heresy, by Lucy Mair

Witchcraft, Women's Honour and Customary Law in Early Modern Wales, by Sally Parkin

Witches and Witchbusters, by Jacqueline Simpson

Witches, Cunning Folk, and Competition in Denmark, by Timothy R. Tangherlini

Witches' Herbs on Trial, by Michael Ostling

#witchcraft#witchblr#history#history of witchcraft#occult#witch trials#research#recommended reading#book recs#jstor

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Herbalism book reccomendations 📚🌿

General herbalism:

The Herbal Medicine-Maker's Handbook by Green J. (2011)

20,000 Secrets of Tea: The Most Effective Ways to Benefit from Nature's Healing Herbs by Zak V. (1999)

The Modern Herbal Dispensatory: A Medicine-Making Guid by Easly T. (2016)

A-Z Guide to Drug-Herb-Vitamin Interactions by Gaby A.R.

American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook (2013)

Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine by Hoffman D. (2003)

Herbal Medicine for Beginners: Your Guide to Healing Common Ailments with 35 Medicinal Herbs by Swift K & Midura R (2018)

Today's Herbal Health: The Essential Reference Guide by Tenney L. (1983)

Today's Herbal Health for Women: The Modern Woman's Natural Health Guide by Tenney L (1996)

Today's Herbal Health for Children: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Nutrition and Herbal Medicine for Children by Tenney L. (1996)

For my black folks!!!

African Medicine: A Complete Guide to Yoruba Healing Science and African Herbal Remedies by Sawandi T.M. (2017)

Handbook of African Medicinal Plants by Iwu M.M. (1993)

Working The Roots: Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing by Lee M.E. (2017)

Hoodoo Medicine: Gullah Herbal Remedies by Mitchell F. (2011)

African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and non-Herbal Treatments by Covey H.C. (2008)

The Art & Practice of Spiritual Herbalism: Transform, Heal, and Remember with the Power of Plants and Ancestral Medicine by Rose K.M. (2022)

Indigenous authors & perspectives!!

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Kimmerer R.W. (2015)

Gathering moss by Kimmerer R.W. (2003)

The Plants Have So Much To Give All We Have To Do Is Ask by Siisip Geniusz M. (2005)

Our Knowledge Is Not Primitive: Decolonizing Botanical Anishinaabe Teachings by Djinn Geniusz W. (2009)

Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: ethnobotany and ecological wisdom of indigenous peoples of northwestern North America by Turner N. (2014)

A Taste of Heritage: Crow Indian Recipes and Herbal Medicines by Hogan Snell A. (2006)

Medicines to Help Us by Belcourt C. (2007)

After the First Full Moon in April: A Sourcebook of Herbal Medicine from a California Indian Elder by Grant Peters J. (2010)

Latin american herbalism works!!

Earth Medicines: Ancestral Wisdom, Healing Recipes, and Wellness Rituals from a Curandera by Cocotzin Ruiz F. (2021)

Hierbas y plantas curativas by Chiti J.F. (2015)

Del cuerpo a las raíces by San Martín P.P., Cheuquelaf I. & Cerpa C. (2011)

Manual introductorio a la Ginecología Natural by San Martín P.P.

🌿This is what I have for now but I’ll update the post as I find and read new works, so keep coming if you wanna check for updates. Thank you for reading 🌿

#herbalism#herbal medicine#herbal health#green witch#green witchcraft#green magic#herbal magic#herbal witch#herbal witchcraft#plant medicine#plant magic#plant witch#folk healer#healing witch#healing magic#curanderismo#yerbera#curandera#rootwork#rootworker

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greeks visited Egypt (Kemet) as students to learn about Africans.

Plato studied in Egypt for 13 years.

Pythagoras studied philosophy, geometry, and medicine in Egypt for 22 years.

Thales was the first Greek philosopher to study in Egypt for 7 years.

Hypocrates, who is incorrectly called the father of medicine, recognized the Egyptian multi-genius, Imhotep as the Father of Medicine.

The "Pythagorean Theorem" was used to build pyramids in Egypt 1000 years before Pythagorean was born.

Plato said Egyptian education makes students more alert and humane.

Plato told his students to go to Egypt if they wanted to study the minds of great philosophers.

Heredotus, the Greek historian described ancient Egypt as the cradle of civilization.

Our ancestors opened the doors of our Nation to foreign peoples, these guests were welcomed with respect and honor according to our traditions but they used our kindness to destroy our Nation.

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading list for Afro-Herbalism:

A Healing Grove: African Tree Remedies and Rituals for the Body and Spirit by Stephanie Rose Bird

Affrilachia: Poems by Frank X Walker

African American Medicine in Washington, D.C.: Healing the Capital During the Civil War Era by Heather Butts

African American Midwifery in the South: Dialogues of Birth, Race, and Memory by Gertrude Jacinta Fraser

African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments by Herbert Covey

African Ethnobotany in the Americas edited by Robert Voeks and John Rashford

Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect by Lorenzo Dow Turner

Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples by Jack Forbes

African Medicine: A Complete Guide to Yoruba Healing Science and African Herbal Remedies by Dr. Tariq M. Sawandi, PhD

Afro-Vegan: Farm-Fresh, African, Caribbean, and Southern Flavors Remixed by Bryant Terry

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston

Big Mama’s Back in the Kitchen by Charlene Johnson

Big Mama’s Old Black Pot by Ethel Dixon

Black Belief: Folk Beliefs of Blacks in America and West Africa by Henry H. Mitchell

Black Diamonds, Vol. 1 No. 1 and Vol. 1 Nos. 2–3 edited by Edward J. Cabbell

Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors by Carolyn Finney

Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. by Ashanté M. Reese

Black Indian Slave Narratives edited by Patrick Minges

Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition by Yvonne P. Chireau

Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry edited by Camille T. Dungy

Blacks in Appalachia edited by William Turner and Edward J. Cabbell

Caribbean Vegan: Meat-Free, Egg-Free, Dairy-Free Authentic Island Cuisine for Every Occasion by Taymer Mason

Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America by Sylviane Diouf

Faith, Health, and Healing in African American Life by Emilie Townes and Stephanie Y. Mitchem

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land by Leah Penniman

Folk Wisdom and Mother Wit: John Lee – An African American Herbal Healer by John Lee and Arvilla Payne-Jackson

Four Seasons of Mojo: An Herbal Guide to Natural Living by Stephanie Rose Bird

Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement by Monica White

Fruits of the Harvest: Recipes to Celebrate Kwanzaa and Other Holidays by Eric Copage

George Washington Carver by Tonya Bolden

George Washington Carver: In His Own Words edited by Gary Kremer

God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man: A Saltwater Geechee Talks About Life on Sapelo Island, Georgia by Cornelia Bailey

Gone Home: Race and Roots through Appalachia by Karida Brown

Ethno-Botany of the Black Americans by William Ed Grime

Gullah Cuisine: By Land and by Sea by Charlotte Jenkins and William Baldwin

Gullah Culture in America by Emory Shaw Campbell and Wilbur Cross

Gullah/Geechee: Africa’s Seeds in the Winds of the Diaspora-St. Helena’s Serenity by Queen Quet Marquetta Goodwine

High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America by Jessica Harris and Maya Angelou

Homecoming: The Story of African-American Farmers by Charlene Gilbert

Hoodoo Medicine: Gullah Herbal Remedies by Faith Mitchell

Jambalaya: The Natural Woman’s Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals by Luisah Teish

Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Health Care by Dayna Bowen Matthew

Leaves of Green: A Handbook of Herbal Remedies by Maude E. Scott

Like a Weaving: References and Resources on Black Appalachians by Edward J. Cabbell

Listen to Me Good: The Story of an Alabama Midwife by Margaret Charles Smith and Linda Janet Holmes

Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination by Melissa Cooper

Mandy’s Favorite Louisiana Recipes by Natalie V. Scott

Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present by Harriet Washington

Mojo Workin’: The Old African American Hoodoo System by Katrina Hazzard-Donald

Motherwit: An Alabama Midwife’s Story by Onnie Lee Logan as told to Katherine Clark

My Bag Was Always Packed: The Life and Times of a Virginia Midwife by Claudine Curry Smith and Mildred Hopkins Baker Roberson

My Face Is Black Is True: Callie House and the Struggle for Ex-Slave Reparations by Mary Frances Berry

My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies by Resmaa Menakem

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker by A'Lelia Bundles

Papa Jim’s Herbal Magic Workbook by Papa Jim

Places for the Spirit: Traditional African American Gardens by Vaughn Sills (Photographer), Hilton Als (Foreword), Lowry Pei (Introduction)

Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome by Dr. Joy DeGruy

Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage by Diane Glave

Rufus Estes’ Good Things to Eat: The First Cookbook by an African-American Chef by Rufus Estes

Secret Doctors: Ethnomedicine of African Americans by Wonda Fontenot

Sex, Sickness, and Slavery: Illness in the Antebellum South by Marli Weiner with Mayzie Hough

Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons by Sylviane Diouf

Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time by Adrian Miller

Spirituality and the Black Helping Tradition in Social Work by Elmer P. Martin Jr. and Joanne Mitchell Martin

Sticks, Stones, Roots & Bones: Hoodoo, Mojo & Conjuring with Herbs by Stephanie Rose Bird

The African-American Heritage Cookbook: Traditional Recipes and Fond Remembrances from Alabama’s Renowned Tuskegee Institute by Carolyn Quick Tillery

The Black Family Reunion Cookbook (Recipes and Food Memories from the National Council of Negro Women) edited by Libby Clark

The Conjure Woman and Other Conjure Tales by Charles Chesnutt

The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature by J. Drew Lanham

The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks by Toni Tipton-Martin

The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas by Adrian Miller

The Taste of Country Cooking: The 30th Anniversary Edition of a Great Classic Southern Cookbook by Edna Lewis

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: An Insiders’ Account of the Shocking Medical Experiment Conducted by Government Doctors Against African American Men by Fred D. Gray

Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape by Lauret E. Savoy

Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African-American Cuisine by Bryant Terry

Vibration Cooking: Or, The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl by Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor

Voodoo and Hoodoo: The Craft as Revealed by Traditional Practitioners by Jim Haskins

When Roots Die: Endangered Traditions on the Sea Islands by Patricia Jones-Jackson

Working Conjure: A Guide to Hoodoo Folk Magic by Hoodoo Sen Moise

Working the Roots: Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing by Michelle Lee

Wurkn Dem Rootz: Ancestral Hoodoo by Medicine Man

Zora Neale Hurston: Folklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings: Mules and Men, Tell My Horse, Dust Tracks on a Road, Selected Articles by Zora Neale Hurston

The Ways of Herbalism in the African World with Olatokunboh Obasi MSc, RH (webinar via The American Herbalists Guild)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Colin Wright

Published: May 3, 2023

The transgender movement has left many intelligent Americans confused about sex. Asked to define the word “woman” during her Supreme Court confirmation hearings last year, Ketanji Brown Jackson demurred, saying “I’m not a biologist.” I am a biologist, and I’m here to help.

Are sex categories in humans empirically real, immutable and binary, or are they mere “social constructs”? The question has public-policy implications related to sex-based legal protections and medicine, including whether males should be allowed in female sports, prisons and other spaces that have historically been segregated by sex for reasons of fairness and safety.

Chase Strangio of the American Civil Liberties Union frequently claims that the binary concept of sex is a recent invention “exclusively for the purposes of excluding trans people from legal protections.” Scottish politician Maggie Chapman asserted in December that her rejection of the “binary and immutable” nature of sex was her motivation for pursuing “comprehensive gender recognition for nonbinary people in Scotland.” (“Nonbinary” people are those who “identify” as neither male nor female.)

When biologists claim that sex is binary, we mean something straightforward: There are only two sexes. This is true throughout the plant and animal kingdoms. An organism’s sex is defined by the type of gamete (sperm or ova) it has the function of producing. Males have the function of producing sperm, or small gametes; females, ova, or large ones. Because there is no third gamete type, there are only two sexes. Sex is binary.

Intersex people, whose genitalia appear ambiguous or mixed, don’t undermine the sex binary. Many gender ideologues, however, falsely claim the existence of intersex conditions renders the categories “male” and “female” arbitrary and meaningless. In “Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex” (1998), the historian of science Alice Dreger writes: “Hermaphroditism causes a great deal of confusion, more than one might at first appreciate, because—as we will see again and again—the discovery of a ‘hermaphroditic’ body raises doubts not just about the particular body in question, but about all bodies. The questioned body forces us to ask what exactly it is—if anything—that makes the rest of us unquestionable.”

In reality, the existence of borderline cases no more raises questions about everyone else’s sex than the existence of dawn and dusk casts doubt on day and night. For the vast majority of people, their sex is obvious. And our society isn’t experiencing a sudden dramatic surge in people born with ambiguous genitalia. We are experiencing a surge in people who are unambiguously one sex claiming to “identify” as the opposite sex or as something other than male or female.

Gender ideology seeks to portray sex as so incomprehensibly complex and multivariable that our traditional practice of classifying people as simply either male or female is grossly outdated and should be abandoned for a revolutionary concept of “gender identity.” This entails that males wouldn’t be barred from female sports, women’s prisons or any other space previously segregated according to our supposedly antiquated notions of “biological sex,” so long as they “identify” as female.

But “intersex” and “transgender” mean entirely different things. Intersex people have rare developmental conditions that result in apparent sex ambiguity. Most transgender people aren’t sexually ambiguous at all but merely “identify” as something other than their biological sex.

Once you’re conscious of this distinction, you will begin to notice gender ideologues attempting to steer discussions away from whether men who identify as women should be allowed to compete in female sports toward prominent intersex athletes like South African runner Caster Semenya. Why? Because so long as they’ve got you on your heels making difficult judgment calls on a slew of complex intersex conditions, they’ve succeeded in drawing your attention away from easy calls on unquestionably male athletes like 2022 NCAA Division I women’s swimming and diving champion Lia Thomas. They shift the focus to intersex to distract from transgender.

Acknowledging the existence of rare difficult cases doesn’t weaken the position or arguments against allowing males in female sports, prisons, restrooms and other female-only spaces. In fact, it’s a much stronger approach because it makes a crucial distinction that the ideologues are at pains to obscure.

Crafting policy to exclude males who identify as women, or “trans women,” from female sports, prisons and other female-only spaces isn’t complicated. Trans women are unambiguously male, so the chances that a doctor incorrectly recorded their sex at birth is zero. Any “transgender policy” designed to protect female spaces need only specify that participants must have been recorded (or “assigned,” in the current jargon) female at birth.

Crafting effective intersex policies is more complicated, but the problem of intersex athletes in female sports is less pressing than that of males in female sports, and there seem to be no current concerns arising from intersex people using female spaces. It should be up to individual organizations to decide which criteria or cut-offs should be used to keep female spaces safe and, in the context of sports, safe and fair. It is imperative, however, that such policies be rooted in properties of bodies, not “identity.” Identity alone is irrelevant to issues of fairness and safety.

Ideologues are wrong to insist that the biology of sex is so complex as to defy all categorization. They’re also wrong to represent the sex binary in an overly simplistic way. The biology of sex isn’t quite as simple as common sense, but common sense will get you a long way in understanding it.

#Colin Wright#biology#queer theory#gender ideology#biological sex#sex is binary#intersex#sex denialism#biology denial#sex binary#gender identity#personal identity#identity#identity politics

708 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morehouse College is a private historically Black men's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. Anchored by its main campus of 61 acres (25 ha) near downtown Atlanta, the college has a variety of residential dorms and academic buildings east of Ashview Heights. Along with Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, and the Morehouse School of Medicine, the college is a member of the Atlanta University Center consortium. Founded by William Jefferson White in 1867 in response to the liberation of enslaved African-Americans following the American Civil War, Morehouse adopted a seminary university model and stressed religious instruction in the Baptist tradition. Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, the college experienced rapid, albeit financially unstable, institutional growth by establishing a liberal arts curriculum. The three-decade tenure of Benjamin Mays during the mid-20th century led to strengthened finances, an enrollment boom, and increased academic competitiveness. The college has played a key role in the development of the civil rights movement and racial equality in the United States.

#morehouse college#black history#black literature#black tumblr#black excellence#black community#civil rights#black history is american history#american history#history#world history

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

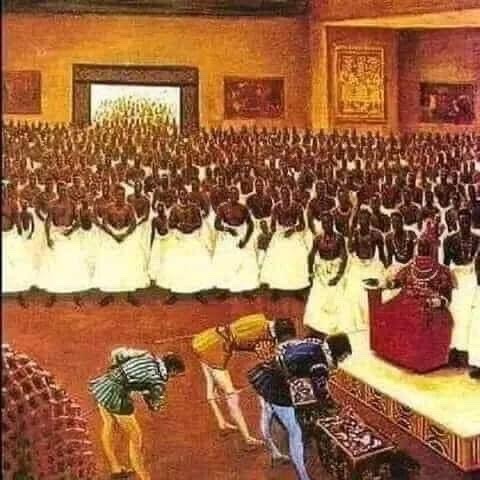

Africa has been very rich even before colonialism

The truth you should know about African

Blacks know your history and divinity

They gave us the Bible and stole our natural resources

Community and Social Cohesion: Traditional African religions often emphasized communal values, fostering a sense of belonging and mutual support within the community. Rituals and ceremonies were communal events that strengthened social ties.

Respect for Nature: Many African traditional religions were deeply connected to nature, promoting a harmonious relationship with the environment. This connection often led to sustainable practices and a respect for the natural world.

Ethical Guidelines: These religions often included moral and ethical guidelines that governed interpersonal relationships. Concepts such as honesty, hospitality, and respect for elders were commonly emphasized.

Cultural Identity: Traditional African religions played a crucial role in shaping cultural identity. They provided a framework for understanding the world, explaining origins, and passing down cultural practices through rituals, myths, and oral traditions.

Islam reached Nigeria through a combination of trade, migration, and cultural interactions. The trans-Saharan trade routes were crucial in bringing Islam to the region. Muslim traders from North Africa and the Middle East ventured into West Africa, establishing economic ties and introducing Islam to local communities.

The city-states along the trade routes, such as Kano and Katsina, became significant centers for Islamic influence. Merchants not only engaged in commercial activities but also played a role in spreading Islamic teachings. Over time, rulers and elites in these city-states embraced Islam, contributing to its gradual acceptance.

Additionally, the spread of Islam in Nigeria was facilitated by the activities of Islamic scholars and missionaries. Scholars known as clerics or Mallams played a key role in teaching Islamic principles and converting people to Islam. They often established Quranic schools and engaged in educational activities that promoted the understanding of Islamic teachings.

Military conquests also played a part in the expansion of Islam in Nigeria. Islamic empires, such as the Sokoto Caliphate in the 19th century, emerged through conquest and warfare, bringing Islam to new territories. The Sokoto Caliphate, led by Usman dan Fodio, sought to establish a strict Islamic state based on Sharia law.

Overall, the spread of Islam in Nigeria was a gradual process influenced by trade networks, migration, the activities of scholars, and, at times, military expansion. The interplay of these factors contributed to the integration of Islam into Nigerian society, shaping its cultural and religious landscape.

In the vast tapestry of Africa's rich cultural heritage, herbal traditional healing stands out as a profound and time-honored practice. African herbal traditional healers, often known as traditional or indigenous healers, play a vital role in the healthcare systems of many communities across the continent. Their practices are deeply rooted in the natural world, drawing on centuries-old wisdom and an intimate understanding of local flora.

African herbal traditional healers are custodians of ancient knowledge, passing down their expertise through generations. They serve as primary healthcare providers in many communities, addressing a wide range of physical, mental, and spiritual ailments. The healing process involves a holistic approach, considering the interconnectedness of the individual with their community and environment.

One of the hallmark features of African herbal traditional healers is their profound knowledge of medicinal plants. These healers have an intricate understanding of the properties, uses, and combinations of various herbs. Passed down through oral traditions, this knowledge is often a well-guarded family secret or shared within the apprentice-master relationship.

The methods employed by herbal traditional healers encompass diverse approaches. Herbal remedies, administered as infusions, decoctions, or ointments, form a significant part of their treatment. These remedies are carefully crafted based on the healer's understanding of the patient's symptoms, lifestyle, and spiritual condition. Additionally, rituals, ceremonies, and prayers are often incorporated into the healing process, acknowledging the interconnectedness of physical and spiritual well-being.

African herbal traditional healers frequently integrate spiritual elements into their practice. They believe that illness can be a manifestation of spiritual imbalances or disharmony. Through rituals and consultations with ancestors or spirits, healers seek to restore balance and harmony within the individual and the community.

Herbal traditional healers are integral to the social fabric of their communities. They often serve not only as healers but also as counselors, mediators, and keepers of cultural traditions. Their practices are deeply intertwined with community life, contributing to the resilience and cohesion of African societies.

While herbal traditional healing holds immense value, it faces challenges in the modern era. The encroachment of Western medicine, issues related to regulation and standardization, and the potential exploitation of traditional knowledge pose threats to this practice. However, there is also a growing recognition of the importance of integrating traditional healing into mainstream healthcare systems, leading to collaborative efforts to preserve and promote this valuable heritage.

African herbal traditional healers are bearers of an ancient legacy, embodying a profound connection between humanity and the natural world. Their healing practices, rooted in herbal wisdom and spiritual insights, offer a unique perspective on healthcare that complements modern medical approaches. Preserving and respecting the knowledge of these healers is not only crucial for the well-being of local communities but also for the broader appreciation of the diverse cultural tapestry that defines Africa.

#life#animals#culture#aesthetic#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#anime and manga#architecture#black community

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ndamathia [Kenyan mythology; African mythology]

The Kikuyu are a somewhat lesser-known ethnic group located mainly in central Kenya. These people have (or had, I am uncertain whether this religion is still being practised) a religious ceremony that was held every few decades and was connected to a creature called the Ndamathia, a creature associated with rainbows. It was the Ndamathia which made rainbows appear in the sky.

This being was a giant aquatic snake-like reptile of incredible length (said to be as long as the rainbows it created). At the end of its enormous tail grew magical hairs that had potent medical properties.

A complicated procedure was required to harvest these hairs, however. First, the creature had to leave the deep rivers in which it lives. This was done by summoning it with a special ceremonial horn, and when the Ndamathia was on land, it was distracted by a beautiful girl. The monster was dangerous, however, and had to be drugged with powerful medicine, which was administered by splashing it on the ground before the girl (which was traditionally done by the same young girl). The reptilian creature would then proceed to lick up the water containing the drug.

In addition, the girl was covered in castor oil (which is made from beans of the castor plant) to make her slippery. The idea was that if the monster tried to grab the girl, she would be too slippery to hold and she would escape from its maw.

The Ndamathia then followed the maiden away from the water, but as it was an incredibly long creature, it took multiple hours of walking before its tail finally left the water. A group of warriors was waiting patiently for this moment and jumped at the tail as soon as it was on land.

Each warrior plucked as many hairs as possible. Even though the Ndamathia was under the influence of medicine, plucking its tail hairs caused it great pain and the creature would become furious. It immediately returned to the water at great speed, so the warriors had to hide after plucking the hairs. When the giant creature arrived, it would find nobody and decided to go back to the depths from which it came.

As the story goes, the girl who acted as bait to lure the creature away from the water would have an important position in Kikuyu society when the ceremony was over, as she was regarded as a heroine. The priests would then slaughter an ewe, a bull and a male goat. They would then proceed to cut the skins of the ewe and the goat into ribbons and dip them in a liquid consisting of the blood mixed with the stomach contents of the slaughtered animals. The hairs of the Ndamathia were tied to these ribbons to make bracelets, which were to be worn by the elders on the ankle and wrist. When this was all done, a giant celebration would be held.

When Christianity established a foothold in the region, the missionaries tried to convince the indigenous people that the Ndamathia was actually their version of the Christian devil, and the creature was villainised. This made an impact on the indigenous folktales that is still visible today: the Kikuyu’s translation of the Bible translates ‘devil’ as ‘Ndamathia’.

Sources:

Hazel, R., 2019, Snakes, People and Spirits, Volume 1: Traditional Eastern Africa in its Broader Context, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 567 pp.

Kenyatta, J., 1978, Facing Mount Kenya: the traditional life of the Gikuyu, African Books Collective, 260 pp.

Karangi, M. M., 2013, The creation of Gikuyu image and identity, in: Revisiting the roots of an Africna shrine: the sacred Mugumo tree: an investigation of the religion and politics of the Gikuyu people in Kenya, p.24 ch.2., Karangi, M.M. (editor), Lambert.

Karanja, J., 2009, The Missionary Movement in Colonial Kenya: the Foundation of Africa Inland Church, Cuvillier Verlag, 227 pp.

(image source: Steven Belledin. The image is card artwork for Magic: the Gathering and depicts an unrelated seamonster, but I chose it because it fits with the description and I rather like the illustration).

#Kenyan mythology#African mythology#aquatic creatures#monsters#mythical creatures#mythology#bestiary

125 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Slaves escaped frequently within the first generation of their arrival from Africa and often preserved their African languages and much of their culture and religion. African traditions included such things as the use of certain medicinal herbs together with special drums and dances when the herbs are administered to a sick person. Other African healing traditions and rites have survived through the centuries.

The jungles around the Caribbean Sea offered food, shelter, and isolation for the escaped slaves. Maroons sustained themselves by growing vegetables and hunting. Their survival depended upon their cultures, and their military abilities, using guerrilla tactics and heavily fortified dwellings involving traps and diversions. Some defined leaving the community as desertion and therefore punishable by death. They also originally raided plantations. During these attacks, the maroons would burn crops, steal livestock and tools, kill slavemasters, and invite other slaves to join their communities. Individual groups of maroons often allied themselves with the local indigenous tribes and occasionally assimilated into these populations. Maroons played an important role in the histories of Brazil, Suriname, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Jamaica.

There is much variety among maroon cultural groups because of differences in history, geography, African nationality, and the culture of indigenous people throughout the Western Hemisphere.

#african#western hemisphere#nationality#indigenous#slavemasters#taino#dominican republic#maroons#puerto rico#haiti#jamaica#military#kemetic dreams#africans#native american#native americans#caucasian#asian#asians#asian americans#african language#african traditional medicine

203 notes

·

View notes