#and pieces from the 20th century…

Note

I don't know if you've done other vintage outfits before, but your recent post just made me think of France in a 50s dress, maybe the Christian Dior style from back then with the cinched waist and the full skirt! He'd look so classy 😌🩷

“It was as if Europe had tired of dropping bombs and now wanted to let off a few fireworks” 🎇 🎆

#ask#my art#francis bonnefoy#hws france#aph france#ANOOONNN#please tell me who you are so i can thank you for such a wonderful request#PLEAAASEE#EXCELLENT SUGGESTION 💘 MORE LIKE THIS PLEASR 💘💘💘#okay i love Dior and I think the new look is my favourite era of 20th century fashion#i was toying with putting him in a white jacket but i lowkey#think he’d want to show off his shoulders u know#queen#i have so many eras of historical fashion that i need to draw him in#and pieces from the 20th century…#like him in le smoking suit…#he’s a WOMAN#an androgynous woman#okay anyway

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

classical pieces with the car energy (shamelessly stealing this wonderful idea from @depressedraisin)

and yes these will the most gut-wrenching, heart-breaking pieces of music so brace yourselves

gustav mahler - symphony no.3: finale (berlin philharmoniker, orchestra) -> (this literally makes me cry every time i listen to it without fail)

gabriel fauré - piano trio in d minor op.120: mvmt 1 (beaux arts trio, piano, violin, cello)

edvard grieg - piano sonata in e minor op.7: mvmt 2 (mikhail pletnev, piano)

maurice ravel - sonata for violin and cello: mvmt 3 (nigel kennedy, lynn harrell, violin, cello)

amy woodeford-finden - 4 indian love lyrics no.4: till i wake (ben johnson, voice, piano)

arnold schoenberg - verklärte nacht op.4 (ensemble intercontemporain, string sextet)

frank bridge - cello sonata: mvmt 1 (actually just the whole thing) (steven isserlis, connie shih, cello, piano)

ralph vaughan williams - on wenlock edge: clun (anthony rolfe johnson - tenor, graham johnson - piano, duke quartet - string quartet) -> (literally part of the lyrics - ‘tis sure small matter for wonder if sorrow is with one still. and if as a lad grows older the troubles he bears are more, he carries his griefs on a shoulder that handselled them long before. )

ignacy jan paderewski - miscellanea op.16 no.4: nocturne in b flat major (stephen hough, piano)

#Spotify#classical music#arctic monkeys#the car#most of these coming from actual pieces I’ve played#no thoughts just vibes#something about the car is just imbued with 19th-20th century romanticism in a way i just can’t explain#is it the melancholy? the emotional density? the deep-rooted maturity? who knows#music speaks louder than words#also fyi sorry a couple of these pieces are stupidly long (looking at you mahler) but it’s so worth it to just sit and listen

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

dragonborn monk go bap bap

#my art#artists on tumblr#art#also on my twitter#also on my insta#digital art#dnd#dungeons and dragons#character art#dragonborn#scared to tag this with scalie but might as well call it what it is#the collar piece is inspired by 19-20th century festival collars from china!#also saw them called wedding pieces so that’s something spicy for his bg maybe

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

🎶! <3

here's the last part of the second mvmt of rachmaninoff's second piano concerto! i know your url is from siken, but this entire movement might as well be a cue for violins. and flutes. for the full experience pls watch evgeny kissin do this perfectly i don't even begin to compare

#sometimes the most romantic piece in the world isn't even romantic it's from the 20th century#ask game#nikki 🏷

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

category 5 "realized my set class analysis is wrong and now i can't make this post-tonal variation say something noteworthy relative to the theme" event

#teaposts#not fandom#for the super-not-musical folks in the crowd: AAAAAAAAAAA#for the moderately musical folks in the crowd: the piece i'm analyzing includes a theme and variations#and in classical music that usually means the basic tune stays the same in the variations but the rhythm or harmony changes#think 'twinkle twinkle little star' vs 'the (english) alphabet song' (the tune is by mozart originally!)#however comma. composers did a lot of crazy shit in the 20th century. which is when my piece is from#so the relationship between theme and variation is not so simple here. the variations have very little to do with rhythm and harmony#and even (at face value) very little to do with the actual theme you hear#i've come up with other reasons that the previous variations are in fact related to the theme#my original reason for the variation i'm talking about now was that it uses almost the same notes as the theme but in a different structure#but apparently i analyzed it wrong and the notes in this variation actually aren't as similar to the theme's as i thought#and i'm having a hard time getting it to come back together again#so. um. AAAAAAA

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back from my disappearance to say that art is an intellectual exercise and if your first gut reaction to something presented as "art" is "this is NOT art, no one should call this art" then you should definitely exercise more

#obviously referring myself to mostly the attitude towards 20th century art and all going forwards#if it doesn't tickle your 'aesthetic sense' please ask yourself 'why would someone feel the need to distance themselves#from the 'art' I'm used to?'#the answer is most often a great starting point to understand the piece itself#my post

1 note

·

View note

Note

Do you happen to know the origin of the fantasy trope in which a deity's power directly corresponds to the number of their believers / the strength of their believers' faith?

I only know it from places like Discworld and DnD that I'm fairly confident are referencing some earlier source, but outside of Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, I can't think of of any specific work it might've come from, 20th-c fantasy really not being my wheelhouse.

Thank you!

That's an interesting question. In terms of immediate sources, I suspect, but cannot prove, that the trope's early appearances in both Dungeons & Dragons and Discworld are most immediately influenced by the oeuvre of Harlan Ellison – his best-known work on the topic, the short story collection Deathbird Stories, was published in 1975, which places it very slightly into the post-D&D era, though most of the stories it contains were published individually earlier – but Ellison certainly isn't the trope's originator. L Sprague de Camp and Fritz Leiber also play with the idea in various forms, as does Roger Zelazny, though only Zelazny's earliest work is properly pre-D&D.

Hm. Off the top of my head, the earliest piece of fantasy fiction I can think of that makes substantial use of the trope in its recognisably modern form is A E van Vogt's The Book of Ptath; it was first serialised in 1943, though no collected edition was published until 1947. I'm confident that someone who's more versed in early 20th Century speculative fiction than I am could push it back even earlier, though. Maybe one of this blog's better-read followers will chime in!

(Non-experts are welcome to offer examples as well, of course, but please double-check the publication date and make sure the work you have in mind was actually published prior to 1974.)

#gaming#tabletop roleplaying#tabletop rpgs#dungeons & dragons#d&d#tropes#media#literature#religion#death mention

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The truth about Medusa and her rape... Mythology breakdown time!

With the recent release of the Percy Jackson television series, Tumblr is bursting with mythological posts, and the apparition of Medusa the Gorgon has been the object of numerous talks throughout this website… Including more and more spreading of misinformation, and more debates about what is the “true” version of Medusa’s backstory.

Already let us make that clear: the idea that Medusa was actually “blessed” or “gifted” by Athena her petrifying gaze/snake-hair curse is to my knowledge not at all part of the Antique world. I still do not know exactly where this comes from, but I am aware of no Greek or Roman texts that talked about this – so it seems definitively a modern invention. After all, the figure of Medusa and her entire myth has been taken part, reinterpreted and modified by numerous modern women, feminist activist, feminist movements or artists engaged in the topic of women’s life and social conditions – most notably Medusa becoming the “symbol of raped women’ wrath and fury”. It is an interesting reading and a fascinating update of the ancient texts, and it is a worthy take on its own time and context – but today we are not talking about the posterity, reinvention and continuity of Medusa as a myth and a symbol. I want to clarify some points about the ACTUAL myth or legend of Medusa – the original tale, as told by the Greeks and then by the Romans.

Most specifically the question: Was Medusa raped?

Step 1: Yes, but no.

The backstory of Medusa you will find very often today, ranging from mythology manuals (vulgarization manuals of course) to Youtube videos, goes as such: Medusa was a priestess of Athena who got raped by Poseidon while in Athena’s temple, and as a result of this, Athena punished Medusa by turning her into the monstrous Gorgon.

Some will go even further claiming Athena’s “curse” wasn’t a punishment but a “gift” or blessing – and again, I don’t know where this comes from and nobody seems to be able to give me any reliable source for that, so… Let’s put this out of there.

Now this backstory – famous and popular enough to get into Riodan’s book series for example – is partially true. There are some elements here very wrong – and by wrong I do mean wrong.

The story of Medusa being raped and turned into a monster due to being raped does indeed exist, and it is the most famous and widespread of all the Medusa stories, the one people remembered for the longest time and wrote and illustrated the most about. Hence why Medusa became in the 20th century this very important cultural symbol tied to rape and the abuse of women and victim-blaming. HOWEVER – the origin of this story is Ovid’s Metamorphoses, from the first century CE or so. Ovid? A Roman poet writing for Roman people. “Metamorphoses”? One of the two fundamental works of Roman literature and one of the two main texts of Roman mythology, alongside Virgil’s Aeneid. This is a purely Roman story belonging to the Roman culture – and not the Greek one. The story of Medusa’s rape does not have Greek precedents to my knowledge, Ovid introduced the element of rape – which is no surprise given Ovid turned half of the romances of Greek mythology into rapes. Note that, on top of all this, Ovid wasn’t even writing for religious purposes, nor was his text an actual mythological effort – he wrote it with pure literary intentions at heart. It is just a piece of poetry and literature taking inspiration from the legends of the Greek world, not some sort of sacred text.

Second big point: The legend I summarized above? It isn’t even the story Ovid wrote, since there are a lot of elements that do not come from Ovid’s retelling of the story (book fourth of the Metamorphoses). For example Ovid never said Medusa was a priestess of Athena – all he said was that she was raped in the temple of Athena. I shouldn’t even be writing Athena since again, this is a Roman text: we are speaking of Minerva here, and of Neptune, not of Athena or Poseidon. Similarly, Minerva’s curse did not involve the petrifying gaze – rather all Ovid wrote about was that Minerva turned Medusa’s hair into snakes, to “punish” her because her hair were very beautiful, and it was what made her have many suitors (none of which she wanted to marry apparently), and it is also implied it is what made Neptune fall in love (or rather fall in lust) with her. I guess it is from this detail that the reading of “Athena’s curse was a gift” comes from – even though this story also clearly does victim-blaming of rape here.

But what is very fascinating is that… we are not definitively sure Neptune raped Medusa in Ovid’s retelling. For sure, the terms used by Ovid in his fourth book of Metamorphoses are clear: this was an action of violating, sexually assaulting, of soiling and corrupting, we are talking about rape. But Ovid refers several other times to Medusa in his other books, sometimes adding details the fourth-book stories does not have (the sixth book for examples evokes how Neptune turned into a bird to seduce Medusa, which is completely absent from the fourth book’s retelling of Medusa’ curse). And in all those other mentions, the terms to designate the relationship between Medusa and Neptune are more ambiguous, evoking seduction and romance rather than physical or sexual assault. (It does not help that Ovid has an habit of constantly confusing consensual and non-consensual sex in his poems, meaning that a rape in one book can turn into a romance in another, or reversal)

But the latter fact makes more sense when you recall that the rape element was invented and added by Ovid. Before, yes Poseidon and Medusa loved each other, but it was a pure romance, or at least a consensual one-night. Heck, if we go back to the oldest records of the love between Poseidon and Medusa, back in Hesiod’s Theogony, we have descriptions of the two of them laying together in a beautiful, flowery meadow – a stereotypical scene of pastoral romances – with no mention of any brutality or violence of any sort. As a result, it makes sense the original “romantic” story would still “leak” or cast a shadow over Ovid’s reinvented and slightly-confused tale.

Step 2: So… no rape?

Well, if we go by Greek texts, no, apparently Medusa was not raped in Greek mythology, and only became a rape victim through Ovid.

The Ancient Greek texts all record Poseidon and Medusa sleeping with each other and having children, but no mention of rape. And the whole “curse of Athena” thing is not present in the oldest records – no temple of Athena soiling, no angry Athena cursing a poor girl… “No curse?” you say “But then how did Medusa got turned into a Gorgon”? Answer: she did not. She was born like that.

As I said before, the oldest record of Medusa’s romance but also of her family comes from Hesiod’s Theogony (Hesiod being one of the two “founding authors” of Greek mythology, alongside Homer – Homer did wrote several times about Medusa, but only as a disembodied head and as a monster already dead, so we don’t have any information about her life). And what do we learn? That Medusa is part of a set of three sisters known as the Gorgons – because oh yes, Ovid did not mention Medusa’s sister now did he? How did Medusa’s sisters ALSO got snake-hair or petrifying-gaze if only Medusa was cursed for sleeping with Neptune? Ovid does not give us any answer because again, it is an “adaptational plot hole”, and the people that try to adapt Ovid’s story have to deal with the slight problem of Stheno and Euryale needing to share their sister’s curse despite seemingly not being involved in the whole Neptune business. Anyway, back to the Greek text.

So, you have those three Gorgon sisters, and Medusa is said to be mortal while her sisters are not. Why is it such a big deal? Because Medusa wasn’t originally some random human or priestess. Oh no! Who were the Gorgons’ parents? Phorcys and Keto/Ceto, aka two sea-gods. Not just two sea-gods – two sea-gods of the ancient, primordial generation of sea-gods, the one that predated Poseidon, and that were cousins to the Titans, the sea-gods born of Gaia mating with Pontos.

So the Gorgons were “divine” of nature – and this is why Medusa being a mortal was considered to be a MASSIVE problem and handicap for her, an abnormal thing for the daughter of two deities. But let’s dig a bit further… Who were Phorcys and Ceto? Long story short: in Greek mythology, they were considered to be sea-equivalents of Typhon and Gaia. They were the parents of many monsters and many sea-horrors: Keto/Ceto herself had her name attributed and equated with any very large creature (like whales) or any terrifying monster (like dragons) from the sea. The Gorgons themselves was a trio of monsters, but their sisters, that directly act as their double in the myth of Perseus? The Graiai – the monstrous trio of old women sharing one eye and one tooth. Hesiod also drops the fact that Ladon (the dragon that guarded the golden apples of the Hesperids), and Echidna (the snake-woman that mated with Typhon and became known as the “mother of monsters”) were also children of Phorcys and Ceto, while other authors will add other monster-related characters such as Scylla (of Charybdis and Scylla fame), the sirens, or Thoosa (the mother of Polyphemus the cyclop). Medusa herself is technically a “mother of monsters” since she birthed both Pegasus the flying horse and Chrysaor, a giant. So here is something very important to get: Medusa, and the Gorgons, were part of a family of monsters. Couple that with the absence of any mention of curses in these ancient texts, and everything is clear.

Originally Medusa was not a woman cursed to become a monster: she was born a monster, part of a group of monster siblings, birthed by monster-creating deities, and she belonged to the world of the “primordial abominations from the sea”, and the pre-Olympian threats, the remnants of the primordial chaos. It is no surprise that the Gorgons were said to live at the edge of the very known world, in the last patch of land before the end of the universe – in the most inhuman, primitive and liminal area possible. They were full-on monsters!

Now you might ask why Poseidon would sleep with a horrible monster, especially when you recall that the Greeks loved to depict the Gorgons as truly bizarre and grotesque. It wasn’t just snake-hair and petrifying gaze: they had boar tusks, and metallic claws, and bloated eyes, and a long tongue that constantly hanged down their bearded chin, and very large heads – some very old depictions even show her with a female centaur body! In fact, the ancient texts imply that it wasn’t so much the Gorgon’s gaze or eyes that had the power to turn people into stone – but that rather the Gorgon was just so hideous and so terrifying to look at people froze in terror – and then literally turned into stone out of fear and disgust. We are talking Lovecraftian level of eldritch horror here. So why would Poseidon, an Olympian god, sleep with one of these horrors? Well… If you know your Poseidon it wouldn’t surprise you too much because Poseidon had a thing for monsters. As a sort of “dark double” of Zeus, whereas Zeus fell in love with beautiful princesses and noble queens and birthed great gods and brave heroes, Poseidon was more about getting freaky with all sorts of unusual and bizarre goddesses, and giving birth to bandits and monsters. A good chunk of the villains of Greek mythology were born out of Poseidon’s loins: Polyphemus, Antaios, Orion, Charybdis, the Aloads… And even his most benevolent offspring has freaky stuff about it – Proteus the shapeshifter or Triton half-man half-fish… So yes, Poseidon sleeping with an abominable Gorgon is not so much out of character.

Step 3: The missing link

Now that we established what Medusa started out as, and what she ended up as… We need to evoke the evolution from point Hesiod to point Ovid, because while people summarized the Medusa debate as “Sea-born monster VS raped and punished woman”, there is a third element needed to understand this whole situation…

Yes Ovid did invent the rape. But he did not invent the idea that Medusa had been cursed by Athena.

The “gorgoneion” – the visual and artistic motif of the Gorgon’s head – was, as I said, a grotesque and monstrous face used to invoke fright into the enemies or to repel any vile influence or wicked spirit by the principle of “What’s the best way to repel bad stuff? Badder stuff”. Your Gorgon was your gargoyle, with all the hideous traits I described before – represented in front (unlike all the other side-portraits of gods and heroes), with the face being very large and flat, a big tongue out of a tusked-mouth, snake-hair, bulging crazy eyes, sometimes a beard or scales… Pure monster. But then… from the fifth century BCE to the second century BCE we see a slow evolution of the “gorgoneion” in art. Slowly the grotesque elements disappear, and the Gorgon’s face becomes… a regular, human face. Even more: it even becomes a pretty woman’s face! But with snakes instead of hair. As such, the idea that Medusa was a gorgeous woman who just had snakes and cursed-eyes DOES come from Ancient Greece – and existed well before Ovid wrote his rape story.

But what was the reason behind this change?

Well, we have to look at the Roman era again. Ovid’s tale of Medusa being cursed for her rape at the hands of Neptune had to rival with another record collected by a Greek author Apollodorus, or Pseudo-Apollodorus, in his Bibliotheca. In this collection of Greek myths, Apollodorus writes that indeed, Medusa was cursed by Athena to have her beautiful hair that seduced everybody be turned into snakes… But it wasn’t because of any rape or forbidden romance, no. It was just because Medusa was a very vain woman who liked to brag about her beauty and hair – and had the foolish idea of saying her hair looked better than Athena’s. (If you recall tales such as Arachne’s or the Judgement of Paris, you will know that despite Athena being wise and clever, one of her main flaws is her vanity).

“Wait a minute,” you are going to tell me, “The Bibliotheca was created in the second century CE! Well after Greece became part of the Roman Empire, and after Ovid’s Metamorphoses became a huge success! It isn’t a true Greek myth, it is just Ovid’s tale being projected here…” And people did agree for a time… Until it was discovered, in the scholias placed around the texts of Apollonios of Rhodes, that an author of the fifth century BCE named Pherecyde HAD recorded in his time a version of Medusa’s legend where she had been cursed into becoming an ugly monster as punishment for her vanity. We apparently do not have the original text of Pherecyde, but the many scholias referring to this lost piece are very clear about this. This means that the story that Apollodorus recorded isn’t a “novelty”, but rather the latest record of an older tradition going back to the fifth century BCE… THE SAME CENTURY THAT THE GORGONEION STARTED LOSING THEIR GROTESQUE, and that the face of Medusa started becoming more human in art.

[EDIT: I also forgot to add that this evolution of Medusa is also proved by strange literary elements, such as Pindar's mention in a poem of his (around 490 BCE) of "fair-cheeked Medusa". A description which seems strange given how Medusa used to be depicted as the epitome of ugliness... But that makes sense if the "cursed beauty" version of the myth had been going around at the time!]

And thus it is all connected and explained. Ovid did invent the rape yes – but he did not invent the idea of Athena cursing Medusa. It pre-existed as the most “recent” and dominating legend in Ancient Greece, having overshadowed by Ovid’s time the oldest Hesiodic records of Medusa being born a monster. So what Ovid did wasn’t completely create a new story out of nowhere, but twist the Greek traditions of Athena cursing Medusa and Medusa having a relationship with Poseidon, so that the two legends would form one and same story. And this explains in retrospect why Ovid focuses so much on describing Medusa’s beautiful hair, and why Ovid’s Minerva would think turning her hair into snake would be a “punishment fit for the crime”: these are leftovers of the Greek tale where Medusa was punished for her boasting and her vanity.

CONCLUSION

Here is the simplified chronology of how Medusa’s evolution went.

A) Primitive Greek myths, Hesiodic tradition: Born a monster out of a family of sea-monsters and monstrous immortals. Is a grotesque, gargoylesque, eldritch abomination. Athena has only an indirect conflict with her, due to being Perseus’ “fairy godmother”. Has a lovely romance with Poseidon.

B) Slow evolution throughout Classical Greece and further: Medusa becomes a beautiful, human-looking girl that was cursed to have snake for hair and petrifying eyes, instead of being a Lovecraftian horror people could not gaze upon. Her conflict with Athena becomes direct, as it is Athena that cursed her due to being offended by her vain boasting. Her punishment is for her vanity and arrogant comparison to the goddess.

C) Ovid comes in: Medusa’s romance with Poseidon becomes a rape, and she is now punished for having been raped inside Athena’s temple.

[As a final note, I want to insist upon the fact that the story of Medusa being raped is not less "worthy" than any other version of the myth. Due to its enormous popularity, how it shaped the figure of Medusa throughout the centuries, and how it still survives today and echoes current-day problems, to try to deny the valid place of this story in the world of myths and legends would be foolish. HOWEVER it is important to place back things in their context, to recognize that it is not the ONLY tale of Medusa, that it was NOT part of Greek mythology, but rather of Roman legends - and let us all always remember this time Poseidon slept with a Lovecraftian horror because my guy is kinky.]

EDIT:

For illustration, I will place here visuals showing how the Ancient art evolved alongside Medusa's story.

Before the 5th century BCE: Medusa is a full-on monster

From the 5th century to the 2nd century BCE: A slow evolution as Medusa goes from a full-on monster to a human turned into a monster. As a result the two depictions of the grotesque and beautiful gorgoneion coexist.

Post 2nd century BCE: Medusa is now a human with snake hair, and just that

#greek mythology#medusa#gorgon#athena#gorgons#poseidon#neptune#minerva#ovid#rape in mythology#greek monsters#roman mythology

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know if you're ready for this BUT American Duchess and the Bata Shoe Museum just launched a collab collection called In Bloom.

They made 3 styles in several colours using 3 styles from the the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries from their current exhibition "In Bloom: Flowers and Footwear", and are currently in pre-sale, with estimated deliveries between July and August 2023.

Let's take a look:

We start at the 18th century with the Primrose shoes, based on their Dunmore model, accurate for 1770s-1790s they are embroidered on satin and are $179 USD while in pre-sale and later will be $199. The original style is in black and pink silk satin, and OF COURSE that's my favourite variation, but the green ones are a close second.

Images from top: 1780s shoes, Bata Shoe Museum / Primrose shoes, American Duchess.

From the 19th century we have this style called Flora, accurate for the late 19th century (1870s-1900), are $230 USD while in pre-sale and later will bee $250. This embroidered boots with satin ribbon laces are probably my favourite style from the collection. Of course my fave colour is black, which is also the colour of the original piece, but the lavender ones are just *chef kiss*:

Images from top: the original French embroidered boots by Francois Pinet, late 1870s-early 1880s, Bata Shoe Museum. / Flora boots, American Duchess

Finally, the 20th century style is the Daisy, accurate for the 1920s-1940s. A vintage style full of flowers and colour, this T-strap style is perfect to pair with a simple dress from any decade and have a very decent 6.3cm heel, so you can dance all night in these art deco shoes.

1920s shoes, Bata Shoe Museum / Daisy shoes, American Duchess.

The sales from the In Bloom collection will support The Bata Shoe Museum in their study, outreach, and conservation of historic footwear, and we're here for it.

More info:

"In Bloom: Flowers and Footwear"

Read more about the collaboration at the American Duchess Blog.

Buy the whole collection in pre-sale here.

Which style are you looking for the most?

#shoes#accessories#in bloom#florals#18th century#19th century#20th century#historical shoes#american duchess

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-offensive Historical terms for Black people in historical fiction

@pleasespellchimerical asked:

So writing historical fiction, with a white POV character. I'm not sure how to address race in the narration. I do have a Black main character, and I feel like it'd feel out of place to have the narrator refer to her as 'Black', that being a more modern term. Not sure how to do this without dipping into common historical terms that are considered racist today. Thoughts on how to handle this delicately, not pull readers out of the narrative? (fwiw, the POV character has a lot of respect for the Black character. The narration should show this)

There are non-offensive terms you can use, even in historical fiction. We can absolutely refer to Black people without slurs, and if slurs is all one can come up with, it’s time to go back to the drawing board. I cannot say which terms are best for your piece without knowing the time period, but hopefully the list below helps.

Historical terms to use for Black people (non-offensive)

African American documented as early as 1782 (documented in an ad in the Pennsylvania Journal). Note the identity isn’t accurate for non-American Black people.

African could refer to African people or “from 1722 as ‘of or pertaining to black Americans.’”

The place of origin could also be used. For example, “a Nigerian woman”

Africo-American documented as early as 1788.

People of Color documented as early as 1796 (with specific contexts, usually mixed people)

Afro American documented as early as 1817, 1831 (depending on source)

Black American documented as early as 1831

Black was used in Old English to refer to dark-skinned people. Black was not capitalized until recent years, so “She was a young black woman.” would make sense to say, though “She was a young Black woman.” is the better standard today, although not universally adopted. I personally prefer it capitalized.

Moor was used as early as the late 1400s for North African people, but had a somewhat flexible use where anyone visibly Black / Of African descent or the Afro Diaspora might be referred to or assumed as a Moor. Note, it has other meanings too, such as referring to Muslim people, but that doesn’t mean the person using it is going by the dictionary definition. Not really the way to go today, but okay in a historical setting (in my opinion).

Biracial (1860s), mixed race (1872), multiracial (1903) and multicultural (1940s) are also terms to refer to people of two or more races.

Occupation + description. Throughout history, many people have been referred to as their occupation. For example, the Carpenter, The Baker, the Blacksmith. Here’s an example of how you might go about using occupation and traits to identify a Black character in history. Here’s an example I came up with on the fly.

“You should go by Jerry’s. He’s the best blacksmith this town’s ever seen. Ya know, the real tall, dark-skinned, curly haired fellow. Family’s come here from Liberia.”

Offensive and less-sensitive terms for Black people

Blacks was used in plural more, but this is generally offensive today (Even writing it gives me **Thee ick*)

Colored was mostly used post-civil war until the mid 20th century, when it became unacceptable. This is not to be conflated with the South African Coloured ethnic group.

Negro/Negroes were also used as early as the 1550s. Capitalization became common in the early 20th century. I'm sure you know it is offensive today, though, admittedly, was not generally seen as such until around the 1960s, when Black replaced it. It does have its contexts, such as the trope “The Magical Negro” but going around using the term or calling someone that today is a lot different.

Mulatto referred to mixed people, generally Black and white, and is offensive today.

The N-word, in all its forms, is explicitly a slur, and there is absolutely no need to use it, especially in a casual manner, in your story. We’ve written about handling the N-word and alluding to it “if need be” but there are other ways to show racism and tension without dropping the word willy-nilly.

Deciding what to use, a modern perspective

I’m in favor of authors relying on the less offensive, more acceptable terms. Particularly, authors outside of the race. Seldom use the offensive terms except from actual direct quotes.

You do not have to use those offensive terms or could at least avoid using them in excess. I know quite famous stories do, but that doesn’t mean we have to so eagerly go that route today. Honestly, from teachers to school, and fellow non-Black students, it’s the modern day glee that people seem to get when they “get a chance to say it” that makes it worse and also makes me not want to give people the chance.

It goes back to historical accuracy only counting the most for an “authentic experience” when it means being able to use offensive terms or exclude BIPOC from stories. We’ve got to ask ourselves why we want to plaster certain words everywhere for the sake of accuracy when there are other just as accurate, acceptable words to use that hurt less people.

Disclaimer: Opinions may vary on these matters. But just because someone from the group cosigns something by stating they’re not offended by it, doesn’t mean a whole lot of others are okay with it and their perspectives are now invalid! Also, of course, how one handles the use of these words as a Black person has a different connotation and freedom on how they use them.

~Mod Colette

The colonial context

Since no country was mentioned, I’m going to add a bit about the vocabulary surrounding Black people during slavery, especially in the Caribbean. Although, Colette adds, if your Black characters are slaves, this begs the question why we always gotta be slaves.

At the time, there were words used to describe people based on the percentage of Black blood they had. Those are words you may find during your searches but I advise you not to use them. As you will realize if you dive a bit into this system, it looks like a classifying table. At the time, people were trying to lighten their descent and those words were used for some as a sort of rank. Louisiana being French for a time, those expressions were also seen there until the end of the 19th century.

The fractions I use were the number of Black ancestors someone had to have to be called accordingly.

Short-list here :

½ : mûlatre or mulatto

¼ or ⅛ : quarteron or métis (depending on the island, I’m thinking about Saint-Domingue, Martinique and Guadeloupe)

1/16 : mamelouk

¾ : griffe or capre

⅞ : sacatra

In Saint-Domingue, it could go down to 1/64, where people were considered sang-mêlé (mixed blood for literal translation, but “HP and the Half-Blood Prince” is translated “HP et le Prince de Sang-Mêlé” in French, so I guess this is another translation possibility).

-Lydie

Use the 3rd person narrative to your advantage

If you are intent on illustrating historical changes in terminology consider something as simple as showing the contrast between using “black” for first person character narration, but “Black” for 3rd person narrator omniscient.

-Marika

Add a disclaimer

I liked how this was addressed in the new American Girl books

it’s set in Harlem in the 1920’s and there’s a paragraph at the beginning that says “this book uses the common language of the time period and it’s not appropriate to use now”

-SK

More reading:

NYT: Use of ‘African-American’ Dates to Nation’s Early Days

The Etymology dictionary - great resource for historical fiction

Wikipedia: Person of Color

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

So hey, to anyone who does femme historical fashion anywhere between 1885 and 1950-

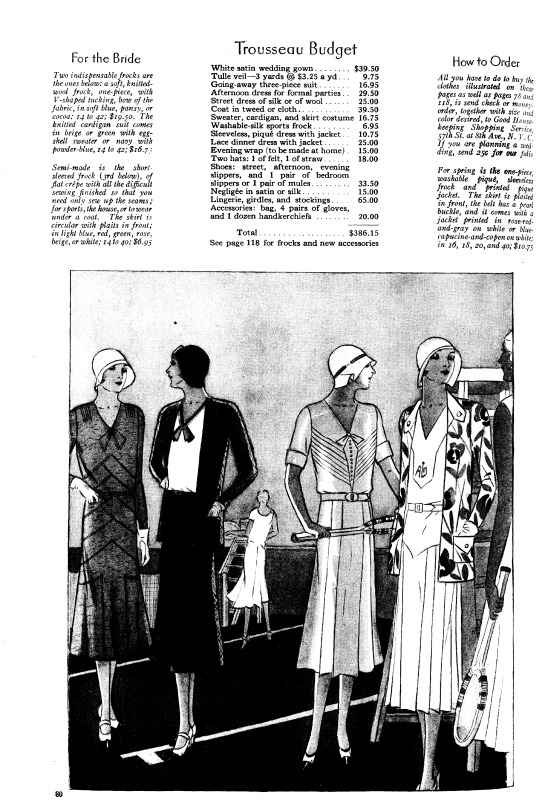

Cornell University has the entire archives of Good Housekeeping up from that time period. And Good Housekeeping used to have English-language fashion plates with clear instructions as to fabric, colour, and cut.

They were ads for the personal shopping service Good Housekeeping apparently??? ran around this time???? and they are a fucking goldmine if you're remotely interested in fashion history or if you're looking to build a 20th century historical wardrobe.

Just, like, look at this?????

An itemized layout of every piece of a young bride's (aspirational) wardrobe in 1930. Including prices. And then below it, a fashion plate, with English-language descriptions of what all these things are and what fabrics they're made of. And an ad for Good Housekeeping's fucking personal shopping service again. XD

IDK, most people who do historical fashion on any kind of serious level probably already know about this??? but I didn't and was stunned and overjoyed to find out that this existed. my research at the library gave me a bunch of high-level overviews that weren't helpful for more than colour and cut.

SO YEAH. THANK YOU CORNELL UNIVERSITY.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: First image shows large falafel balls, one pulled apart to show that it is bright green and red on the inside, on a plate alongside green chilis, parsley, and pickled turnips. Second image is an extreme close-up of the inside of a halved falafel ball drizzled with tahina sauce. End ID]

فلافل محشي فلسطيني / Falafel muhashshi falastini (Palestinian stuffed falafel)

Falafel (فَلَافِل) is of contested origin. Various hypotheses hold that it was invented in Egypt any time between the era of the Pharoahs and the late nineteenth century (when the first written references to it appear). In Egypt, it is known as طَعْمِيَّة (ṭa'miyya)—the diminutive of طَعَام "piece of food"—and is made with fava beans. It was probably in Palestine that the dish first came to be made entirely with chickpeas.

The etymology of the word "falafel" is also contested. It is perhaps from the plural of an earlier Arabic word *filfal, from Aramaic 𐡐𐡋𐡐𐡉𐡋 "pilpāl," "small round thing, peppercorn"; or from "مفلفل" "mfelfel," a word meaning "peppered," from "فلفل" "pepper" + participle prefix مُ "mu."

This recipe is for deep-fried chickpea falafel with an onion and sumac حَشْوَة (ḥashua), or filling; falafel are also sometimes stuffed with labna. The spice-, aromatic-, and herb-heavy batter includes additions common to Palestinian recipes—such as dill seeds and green onions—and produces falafel balls with moist, tender interiors and crisp exteriors. The sumac-onion filling is tart and smooth, and the nutty, rich, and bright tahina-based sauce lightens the dish and provides a play of textures.

Falafel with a filling is falafel مُحَشّي (muḥashshi or maḥshshi), from حَشَّى (ḥashshā) "to stuff, to fill." While plain falafel may be eaten alongside sauces, vegetables, and pickles as a meal or a snack, or eaten in flatbread wraps or kmaj bread, stuffed falafel are usually made larger and eaten on their own, not in a wrap or sandwich.

Falafel has gone through varying processes of adoption, recognition, nationalization, claiming, and re-patriation in Zionist settlers' writing. A general arc may be traced from adoption during the Mandate years, to nationalization and claiming in the years following the Nakba until the end of the 20th century, and back to re-Arabization in the 21st. However, settlers disagree with each other about the value and qualities of the dish within any given period.

What is consistent is that falafel maintains a strategic ambiguity: particular qualities thought to belong to "Arabs" may be assigned, revoked, rearranged, and reassigned to it (and to other foodstuffs and cultural products) at will, in accordance with broader trends in politics, economics, and culture, or in service of the particular argument that a settler (or foreign Zionist) wishes to make.

Mandate Palestine, 1920s – early '30s: Secular and collective

While most scholars hold that claims of an ancient origin for falafel are unfounded, it was certainly being eaten in Palestine by the 1920s. Yael Raviv writes that Jewish settlers of the second and third "עליות" ("aliyot," waves of immigration; singular "עליה" "aliya") tended to adopt falafel, and other Palestinian foodstuffs, largely uncritically. They viewed Palestinian Arabs as holding vessels that had preserved Biblical culture unchanged, and that could therefore serve as models for a "new," agriculturally rooted, physically active, masculine Jewry that would leave behind the supposed errors of "old" European Jewishness, including its culinary traditions—though of course the Arab diet would need to be "corrected" and "civilized" before it was wholly suitable for this purpose.

Falafel was further endeared to these "חֲלוּצִים" ("halutzim," "pioneers") by its status as a street food. The undesirable "old" European Jewishness was associated with the insularity of the nuclear family and the bourgeois laziness of indoor living. The קִבּוּצים ("Kibbutzim," communal living centers), though they represented only a small minority of settlers, furnished a constrasting ideal of modern, earthy Jewishness: they left food production to non-resident professional cooks, eliding the role of the private, domestic kitchen. Falafel slotted in well with these ascetic ideals: like the archetypal Arabic bread and olive oil eaten by the Jewish farmer in his field, it was hardy, cheap, quick, portable, and unconnected to the indoor kitchen.

The author of a 1929 article in דאר היום ("Doar Hyom," "Today's Mail") shows unrestrained admiration for the "[]מזרחי" ("Oriental") food, writing of his purchase of falafel stuffed in a "פיתה" ("pita") that:

רק בני-ערב, ואחיהם — היהודים הספרדים — רק הם עלולים "להכנת מטעם מפולפל" שכזה, הנעים כל כך לחיך [...].

("Only the Arabs, and their brothers—the Sepherdi Jews—only they are likely to create a delicacy so 'peppered' [a play on the פ-ל-פ-ל (f-l-f-l) word root], one so pleasing to the palate".)

Falafel's strong association with "Arabs" (i.e., Palestinians), however, did blemish the foodstuff in the eyes of some as early as 1930. An article in the English-language Palestine Bulletin told the story of Kamel Ibn Hassan's trial for the murder of a British soldier, lingering on the "Arab" "hashish addicts," "women of the streets," and "concessionaires" who rounded out this lurid glimpse into the "underground life lived by a certain section of Arab Haifa"; it was in this context that Kamel's "'business' of falafel" (scare quotes original) was mentioned.

Mandate Palestine, late 1930s–40s: A popular Oriental dish

In 1933, only three licensed falafel vendors operated in Tel Aviv; but by December 1939, Lilian Cornfeld (columnist for the English-language Palestine Post) could lament that "filafel cakes" were "proclaiming their odoriferous presence from every street corner," no longer "restricted to the seashore and Oriental sections" of the city.

Settlers' attitudes to falafel at this time continued to range from appreciation to fascinated disgust to ambivalence, and references continued to focus on its cheapness and quickness. According to Cornfeld, though the "orgy of summertime eating" of which falafel was the "most popular" representative caused some dietary "damage" to children, and though the "rather messy and dubious looking" food was deep-fried, the chickpeas themselves were still of "great nutritional value": "However much we may object to frying, — if fry you must, this at least is the proper way of doing it."

Cornfeld's article, appearing 10 years after the 1929 reference to falafel in pita quoted above, further specifies how this dish was constructed:

There is first half a pita (Arab loaf), slit open and filled with five filafels, a few fried chips [i.e. French fries] and sometimes even a little salad. The whole is smeared over with Tehina, a local mayonnaise made with sesame oil (emphasis original).

The ethnicity of these early vendors is not explicitly mentioned in these accounts. The Zionist "תוצרת הארץ" "totzeret ha’aretz"; "produce of the land") campaign in the 1930s and 1940s recommended buying only Jewish produce and using only Jewish labor, but it did not achieve unilaterial success, so it is not assured that settlers would not be buying from Palestinian vendors. There were, however, also Mizrahi Jewish vendors in Tel Aviv at this time.

The WW2-era "צֶנַע" ("tzena"; "frugality") period of rationing meat, which was enforced by British mandatory authorities beginning in 1939 and persisting until 1959, may also have contributed to the popularity of falafel during this time—though urban settlers employed various strategies to maintain access to significant amounts of meat.

Israel and elsewhere, 1950s – early 60s: The dawn of de-Arabization

After the Nakba (the ethnic cleansing of broad swathes of Palestine in the creation of the modern state of "Israel"), the task of producing a national Israeli identity and culture tied to the land, and of asserting that Palestinians had no like sense of national identity, acquired new urgency. The claiming of falafel as "the national snack of Israel," the decoupling of the dish from any association with "Arabs" (in settlers' writing of any time period, this means "Palestinians"), and the insistence on associating it with "Israel" and with "Jews," mark this time period in Israeli and U.S.-ian newspaper articles, travelogues, and cookbooks.

During this period, falafel remained popular despite the "reintegrat[ion]" of the nuclear family into the "national project," and the attendant increase in cooking within the familial home. It was still admirably quick, efficient, hardy, and frequently eaten outside. When it was homemade, the dish could be used rhetorically to marry older ideas about embodying a "new" Jewishness and a return to the land through dietary habits, with the recent return to the home kitchen. In 1952, Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, the wife of the second President of Israel, wrote to a South African Zionist women's society:

I prefer Oriental dishes and am inclined towards vegetarianism and naturalism, since we are returning to our homeland, going back to our origin, to our climate, our landscape and it is only natural that we liberate ourselves from many of the habits we acquired in the course of our wanderings in many countries, different from our own. [...]

Meals at the President's table [...] consist mainly of various kinds of vegetable prepared in the Oriental manner which we like as well as [...] home-made Falafel, and, of course vegetables and fruits of the season.

Out of doors, associations of falafel with low prices, with profusion and excess, and with youth, travelling and vacation (especially to urban locales and the seaside) continue. Falafel as part and parcel of Israeli locales is given new emphasis: a reference to the pervasive smell of frying falafel rounds out the description of a chaotic, crowded, clamorous scene in the compact, winding streets of any old city. Falafel increasingly stands metonymically for Israel, especially in articles written to entice Jewish tourists and settlers: no one is held to have visited Israel unless they have tried real Israeli falafel. A 1958 song ("ולנו יש פלאפל", "And We Have Falafel") avers that:

הַיּוֹם הוּא רַק יוֹרֵד מִן הַמָּטוֹס

[...] כְבָר קוֹנֶה פָלָאפֶל וְשׁוֹתֶה גָּזוֹז

כִּי זֶה הַמַּאֲכָל הַלְּאֻמִּי שֶׁל יִשְׂרָאֵל

("Today when [a Jew] gets off the plane [to Israel] he immediately has a falafel and drinks gazoz [...] because this is the national dish of Israel"). A 1962 story in Israel Today features a boy visiting Israel responding to the question "Have you learned Hebrew yet?" by asserting "I know what falafel is." Recipes for falafel appear alongside ads for smoked lox and gefilte fish in U.S.-ian Jewish magazines; falafel was served by Zionist student groups in U.S.-ian universities beginning in the 1950s and continuing to now.

These de-Arabization and nationalization processes were possible in part because it was often Mizrahim (West Asian and North African Jews) who introduced Israelis to Palestinian food—especially after 1950, when they began to immigrate to Israel in larger numbers. Even if unfamiliar with specific Palestinian dishes, Mizrahim were at least familiar with many of the ingredients, taste profiles, and cooking methods involved in preparing them. They were also more willing to maintain their familiar foodways as settlers than were Zionist Ashkenazim, who often wanted to distance themselves from European and diaspora Jewish culture.

Despite their longstanding segregation from Israeli Ashkenazim (and the desire of Ashkenazim to create a "new" European Judaism separate from the indolence and ignorance of "Oriental" Jews, including their wayward foodways), Mizrahim were still preferable to Palestinian Arabs as a point of origin for Israel's "national snack." When associated with Mizrahi vendors, falafel could be considered both Oriental and Jewish (note that Sephardim and Mizrahim are unilaterally not considered to be "Arabs" in this writing).

Thus food writing of the 1950s and 60s (and some food writing today) asserts, contrary to settlers' writing of the 1920s and 30s, that falafel had been introduced to Israel by Jewish immigrants from Syria, Yemen, or Morocco, who had been used to eating it in their native countries—this, despite the fact that Yemen and Morocco did not at this time have falafel dishes. Even texts critical of Zionism echoed this narrative. In fact, however, Yemeni vendors had learned to make falafel in Egypt on their way to Palestine and Israel, and probably found falafel already being sold and eaten there when they arrived.Meneley, Anne2007 Like an Extra Virgin. American Anthropologist 109(4):678–687

Meanwhile, "pita" (Palestinian Arabic: خبز الكماج; khubbiz al-kmaj) was undergoing in some quarters a similar process of Israelization; it remained "Arab" in others. In 1956, a Boston-born settler in Haifa wrote for The Jewish Post:

The baking of the pittah loaves is still an Arab monopoly [in Israel], and the food is not available at groceries or bakeries which serve Jewish clientele exclusively. For our Oriental meal to be a success we must have pittah, so the more advance shopping must be done.

This "Arab monopoly" in fact did not extent to an Arab monopoly in discourse: it was a mere four years later that the National Jewish Post and Opinion described "Peeta" as an "Israeli thin bread." Two years after that, the U.S.-published My Jewish Kitchen: The Momales Ta'am Cookbook (co-authored by Zionist writer Shushannah Spector) defined "pitta" as an "Israeli roll."

Despite all this scrubbing work, settlers' attitudes towards falafel in the late 1950s were not wholly positive, and references to the dish as having been "appropriated from the [Palestinian] Arabs" did not disappear. A 1958 article, written by a Boston-born man who had settled in Israel in 1948 and published in U.S.-ian Zionist magazine Midstream, repeats the usual associations of falafel with the "younger set" of visitors from kibbutzim to "urban" locales; it also denigrates it as a “formidably indigestible Arab delicacy concocted from highly spiced legumes rolled into little balls, fried in grease, and then inserted into an underbaked piece of dough, known as a pita.”

Thus settlers were ambivalent about khubbiz as well. If their food writing sometimes refers to pita as "doughy" or "underbaked," it is perhaps because they were purchasing it from stores rather than baking it at home—bakeries sometimes underbake their khubbiz so that it retains more water, since it is sold by weight.

Israel and elsewhere, late 1960s–2010s: Falafel with even fewer Arabs

The sanitization of falafel would be more complete in the 60s and 70s, as falafel was gradually moved out of separate "Oriental dishes" categories and into the main sections of Israeli cookbooks. A widespread return to כַּשְׁרוּת (kashrut; dietary laws) meant that falafel, a פַּרְוֶה (parve) dish—one that contained no meat or dairy—was a convenient addition on occasions when food intersected with nationalist institutions, such as at state dinners and in the mess halls of Israeli military forces.

This, however, still did not prohibit Israelis from displaying ambivalence towards the food. Falafel was more likely to be glorified as a symbol of Jewish Israel in foreign magazines and tourist guides, including in the U.S.A. and Italy, than it was to be praised in Israeli Zionist publications.

Where falafel did maintain an association with Palestinians, it was to assert that their versions of it had been inferior. In 1969, Israeli writer Ruth Bondy opines:

Experience says that if we are to form an affection for a people we should find something admirable about its customs and folklore, its food or girls, its poetry and music. True, we have taken the first steps in this direction [with Palestinians]: we like kebab, hummous, tehina and falafel. The trouble is that these have already become Jewish dishes and are prepared more tastily by every Rumanian restaurateur than by the natives of Nablus.

Opinions about falafel in this case seem to serve as a mirror for political opinions about Palestinians: the same writer had asserted, on the previous page, that the "ideal situation, of course, would be to keep all the territories we are holding today—but without so many Arabs. A few Arabs would even be desirable, for reasons of local color, raising pigs for non-Moslems and serving bread on the Passover, but not in their masses" (trans. Israel L. Taslitt).

Later narratives tended to retrench the Israelization of falafel, often acknowledging that falafel had existed in Palestine prior to Zionist incursion, but holding that Jewish settlers had made significant changes to its preparation that were ultimately responsible for making it into a worldwide favorite. Joan Nathan's 2001 Foods of Israel Today, for example, claimed that, while fava and chickpea falafel had both preëxisted the British Mandate period, Mizrahi settlers caused chickpeas to be the only pulse used in falafel.

Gil Marks, who had echoed this narrative in his 2010 Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, later attributed the success of Palestinian foods to settlers' inventiveness: "Jews didn’t invent falafel. They didn’t invent hummus. They didn’t invent pita. But what they did invent was the sandwich. Putting it all together. And somehow that took off and now I have three hummus restaurants near my house on the Upper West Side.”

Israel and elsewhere, 2000s – 2020s: Re-Arabization; or, "Local color"

Ronald Ranta has identified a trend of "re-Arabizing" Palestinian food in Israeli discourse of the late 2000s and later: cooks, authors, and brands acknowledge a food's origin or identity as "Arab," or occasionally even "Palestinian," and consumers assert that Palestinian and Israeli-Palestinian (i.e., Israeli citizens of Palestinian ancestry) preparations of foods are superior to, or more "authentic" than, Jewish-Israeli ones. Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian brands and restaurants market various foods, including falafel, as "אסלי" ("asli"), from the Arabic "أَصْلِيّ" ("ʔaṣliyy"; "original"), or "בלדי" ("baladi"), from the Arabic "بَلَدِيّ" ("baladiyy"; "native" or "my land").

This dedication to multiculturalism may seem like progress, but Ranta cautions that it can also be analyzed as a new strategy in a consistent pattern of marginalization of the indigenous population: "the Arab-Palestinian other is re-colonized and re-imagined only as a resource for tasty food [...] which has been de-politicized[;] whatever is useful and tasty is consumed, adapted and appropriated, while the rest of its culture is marginalized and discarded." This is the "serving bread" and "local color" described by Bondy: "Arabs" are thought of in terms of their usefulness to settlers, and not as equal political participants in the nation. For Ranta, the "re-Arabizing" of Palestinian food thus marks a new era in Israel's "confiden[ce]" in its dominance over the indigenous population.

So this repatriation of Palestinian food is limited insofar as it does not extend to an acknowledgement of Palestinians' political aspirations, or a rejection of the Zionist state. Food, like other indicators and aspects of culture, is a "safe" avenue for engagement with colonized populations even when politics is not.

The acknowledgement of Palestinian identity as an attempt to neutralize political dissent, or perhaps to resolve the contradictions inherent in liberal Zionist identity, can also be seen in scholarship about Israeli food culture. This scholarship tends to focus on narratives about food in the cultural domain, ignoring the material impacts of the settler-colonialist state's control over the production and distribution of food (something that Ranta does as well). Food is said to "cross[] borders" and "transcend[] cultural barriers" without examination of who put the borders there (or where, or why, or how, or when). Disinterest in material realities is cultivated so that anodyne narratives about food as “a bridge” between divides can be pursued.

Raviv, for example, acknowledges that falafel's de-Palestinianization was inspired by anti-Arab sentiment, and that claiming falafel in support of "Jewish nationalism" was a result of "a connection between the people and a common land and history [needing] to be created artificially"; however, after referring euphemistically to the "accelerated" circumstances of Israel's creation, she supports a shared identity for falafel in which it can also be recognized as "Israeli." She concludes that this should not pose a problem for Palestinians, since "falafel was never produced through the labor of a colonized population, nor was Palestinian land appropriated for the purpose of growing chickpeas for its preparation. Thus, falafel is not a tool of oppression."

Palestine and Israel, 1960s – 2020s: Material realities

Yet chickpeas have been grown in Israel for decades, all of them necessarily on appropriated Palestinian land. Experimentation with planting in the arid conditions of the south continues, with the result that today, chickpea is the major pulse crop in the country. An estimated 17,670,000 kilograms of chickpeas were produced in Israel in 2021; at that time, this figure had increased by an average of 3.5% each year since 1966. 73,110 kilograms of that 2021 crop was exported (this even after several years of consecutive decline in chickpea exports following a peak in 2018), representing $945,000 in exports of dried chickpeas alone.

The majority of these chickpeas ($872,000) were exported to the West Bank and Gaza; Palestinians' inability to control their own imports (all of which must pass through Israeli customs, and which are heavily taxed or else completely denied entry), and Israeli settler violence and government expropriation of land, water, and electricity resources (which make agriculture difficult), mean that Palestine functions as a captive market for Israeli exports. Israeli goods are the only ones that enter Palestinian markets freely.

By contrast, Palestinian exports, as well as imports, are subject to taxation by Israel, and only a small minority of imports to Israel come from Palestine ($1.13 million out of $22.4 million of dried chickpeas in 2021).

The 1967 occupation of the West Bank has besides had a demonstrable impact on Palestinians' ability to grow chickpeas for domestic consumption or export in the first place, as data on the changing uses of agricultural land in the area from 1966–2001 allow us to see. Chickpeas, along with wheat, barley, fenugreek, and dura, made up a major part of farmers' crops from 1840 to 1914; but by 2001, the combined area devoted to these field crops was only a third of its 1966 value. The total area given over to chickpeas, lentils and vetch, in particular, shrank from 14,380 hectares in 1966 to 3,950 hectares in 1983.

Part of this decrease in production was due to a shortage of agricultural labor, as Palestinians, newly deprived of land or of the necessary water, capital, and resources to work it—and in defiance of Raviv's assertion that "falafel was never produced through the labor of a colonized population"—sought jobs as day laborers on Israeli fields.

The dearth of water was perhaps especially limiting. Palestinians may not build anything without a permit, which the Israeli military may deny for any, or for no, reason: no Palestinian's request for a permit to dig a well has been approved in the West Bank since 1967. Israel drains aquifiers for its own use and forbids Palestinians to gather rainwater, which the Israeli military claims to own. This lack of water led to land which had previously been used to grow other crops being transitioned into olive tree fields, which do not require as much water or labor to tend.

In Gaza as well, occupation systematically denies Palestinians of food itself, not just narratives about food. The majority of the population in Gaza is food-insecure, as Israel allows only precisely determined (and scant) amounts of food to cross its borders. Gazans rely largely on canned goods, such as chickpeas (often purchased at subsidized rates through food aid programs run by international NGOs), because they do not require scarce water or fuel to prepare—but canned chickpeas cannot be used to prepare a typical deep-fried falafel recipe (the discs would fall apart while frying). There is, besides, a continual shortage of oil (of which only a pre-determined amount of calories are allowed to enter the Strip). Any narrative about Israeli food culture that does not take these and other realities of settler-colonialism into account is less than half complete.

Of course, falafel is far from the only food impacted by this long campaign of starvation, and the strategy is only intensifying: as of December 2023, children are reported to have died by starvation in the besieged Gaza Strip.

Support Palestinian resistance by calling Elbit System’s (Israel’s primary weapons manufacturer) landlord; donating to Palestine Action’s bail fund; buying an e-sim for distribution in Gaza; or donating to help a family leave Gaza.

Equipment:

A meat grinder, or a food processor, or a high-speed or immersion blender, or a mortar and pestle and an enormous store of patience

A pot, for frying

A kitchen thermometer (optional)

Ingredients:

Makes 12 large falafel balls; serves 4 (if eaten on their own).

For the فلافل (falafel):

500g dried chickpeas (1010g once soaked)

1 large onion

4 cloves garlic

1 Tbsp cumin seeds

1 Tbsp coriander seeds

2 tsp dill seeds (عين جرادة; optional)

1 medium green chili pepper (such as a jalapeño), or 1/2 large one (such as a ram's horn / فلفل قرن الغزال)

2 stalks green onion (3 if the stalks are thin) (optional)

Large bunch (50g) parsley, stems on; or half parsley and half cilantro

2 Tbsp sea salt

2 tsp baking soda (optional)

For the حَش��ة (filling):

2 large yellow onions, diced

1/4 cup coarsely ground sumac

4 tsp shatta (شطة: red chili paste), optional

Salt, to taste

3 Tbsp olive oil

For the طراطور (tarator):

3 cloves garlic

1/2 tsp table salt

1/4 cup white tahina

Juice of half a lemon (2 Tbsp)

2 Tbsp vegan yoghurt (لبن رائب; optional)

About 1/4 cup water

To make cultured vegan yoghurt, follow my labna recipe with 1 cup, instead of 3/4 cup, of water; skip the straining step.

To fry:

Several cups neutral oil

Untoasted hulled sesame seeds (optional)

Instructions:

1. If using whole spices, lightly toast in a dry skillet over medium heat, then grind with a mortar and pestle or spice mill.

2. Grind chickpeas, onion, garlic, chili, and herbs. Modern Palestinian recipes tend to use powered meat grinders; you could also use a food processor, speed blender, or immersion blender. Some recipes set aside some of the chickpeas, aromatics, and herbs and mince them finely, passing the knife over them several times, then mixing them in with the ground mixture to give the final product some texture. Consult your own preferences.

To mimic the stone-ground texture of traditional falafel, I used a mortar and pestle. I found this to produce a tender, creamy, moist texture on the inside, with the expected crunchy exterior. It took me about two hours to grind a half-batch of this recipe this way, so I don't per se recommend it, but know that it is possible if you don't have any powered tools.

3. Mix in salt, spices, and baking soda and stir thoroughly to combine. Allow to chill in the fridge while you prepare the filling and sauce.

If you do not plan to fry all of the batter right away, only add baking soda to the portion that you will fry immediately. Refrigerate the rest of the batter for up to 2 days, or freeze it for up to 2 months. Add and incorporate baking soda immediately before frying. Frozen batter will need to be thawed before shaping and frying.

For the filling:

1. Heat olive oil in a skillet over medium heat. Fry onion and a pinch of salt for several minutes, until translucent. Remove from heat.

2. Add sumac and stir to combine. Add shatta, if desired, and stir.

For the tarator:

1. Grind garlic and salt in a mortar and pestle (if you don't have one, finely mince and then crush the garlic with the flat of your knife).

2. Add garlic to a bowl along with tahina and whisk. You will notice the mixture growing smoother and thicker as the garlic works as an emulsifier.

3. Gradually add lemon juice and continue whisking until smooth. Add yoghurt, if desired, and whisk again.

4. Add water slowly while whisking until desired consistency is achieved. Taste and adjust salt.

To fry:

1. Heat several inches of oil in a small or medium pot to about 350 °F (175 °C). A piece of batter dropped in the oil should float and immediately form bubbles, but should not sizzle violently. (With a small pot on my gas stove, my heat was at medium-low).

2. Use your hands or a large falafel mold to shape the falafel.

To use a falafel mold: Dip your mold into water. If you choose to cover both sides of the falafel with sesame seeds, first sprinkle sesame seeds into the mold; then apply a flat layer of batter. Add a spoonful of filling into the center, and then cover it with a heaping mound of batter. Using a spoon, scrape from the center to the edge of the mold repeatedly, while rotating the mold, to shape the falafel into a disc with a slightly rounded top. Sprinkle the top with sesame seeds.

To use your hands: wet your hands slightly and take up a small handful of batter. Shape it into a slightly flattened sphere in your palm and form an indentation in the center; fill the indentation with filling. Cover it with more batter, then gently squeeze between both hands to shape. Sprinkle with sesame seeds as desired.

3. Use a slotted spoon or kitchen spider to lower falafel balls into the oil as they are formed. Fry, flipping as necessary, until discs are a uniform brown (keep in mind that they will darken another shade once removed from the oil). Remove onto a wire rack or paper towel.

If the pot you are using is inclined to stick, be sure to scrape the bottom and agitate each falafel disc a couple seconds after dropping it in.

4. Repeat until you run out of batter. Occasionally use a slotted spoon or small sieve to remove any excess sesame seeds from the oil so they do not burn and become acrid.

Serve immediately with sauce, sliced vegetables, and pickles, as desired.

#Palestine#Israel#vegetarian recipes#Palestinian#falafel#chickpeas#sumac#onions#garlic#parsley#cilantro#dill seeds#sesame seeds#tahina#yoghurt#long post /

781 notes

·

View notes

Text

there is a reproduced 1909 magazine story in this book I read recently (The Female Economy by Wendy Gamber it is amazing oh my god) that just makes my soul depart my body

it's about a woman who decides to make her own new dress undersleeves to save money, and enlists a dressmaker to do the actual sewing. but she can Totally Cut The Sleeves Out Herself With This Paper Pattern So She's The One Making It Really

for reference as to why this is absolutely insane, cutting/fitting is the single hardest part of Victorian and Edwardian dressmaking. this is where all the Mathing and Thinking and Make Two-Dimensional Shapes Into Three-Dimensional Garments come into play. and contrary to popular belief, while most women at the time were accomplished seamstresses- in the sense of "putting fabric together using stitches, and likely also mending" -they didn't necessarily have a clue how to shape a garment. especially not the highly fitted bodices and imaginative sleeve shapes of the day. custom-made clothes from dressmakers were commonplace for most social strata in urban and suburban areas; even lower-middle and working-class women had "lesser" dressmakers they patronized

you do start seeing commercial patterns and home dressmaking manuals steadily increasing throughout the latter half of the 19th century and the early 20th, but in general there was no reason to assume that a random woman on the street could make herself a properly-fitted gown- or even just sleeves -from scratch. (not even with a pattern, which were notoriously scant on instructions back then)

a modern hobbyist historical costumer probably has more knowledge of how to actually make clothing from 1909 than the average woman living in 1909

so anyway this lady tells the professional dressmaker to stop giving her advice, she's got this, she's FINE HONEST. and then gets pissed at the dressmaker for not telling her she needed to include seam allowance in her pieces

for more reference, that is...

...the absolute most basic Day One sewing knowledge

#sewing#history#I am on the astral plane#someone page instagram user Can You Sew This For Me#edwardian

706 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mutual 1: hurtling towards the gigantic limestone aurochs again btw

Mutual 2: none of you have ever had sex, unlike me, im having sex right now

Mutual 4: eating a full lemon, yes with the rind #NoScurvy

Mutual 5: you cant possibly imagine how difficult it is to be the 21st century incarnation of maximillien robespierre

Mutual 6: *6-armed purple leopardtaur with her tits and dick and balls out* If you even care.

Mutual 7: gifset of two gangly guys from a 70s sitcom making eyes at each other

Mutual 8: none of you have ever had sex, unlike me, im having sex right now

Mutual 9: i need roddy mcdowell to murder me or i'll die

Mutual 10: you cant possibly imagine how difficult it is to be the 21st century incarnation of maximillien robespierre

Mutual 11: *pics from a 90s fashion show with 9 filters over them*

Mutual 12: poll: favorite outfit worn by a character you cant remember during one particular episode of a show you did watch

Mutual 13: #honestly her toxic pussy makes me such a misogynist (tag on image of 40smth actor man)

Mutual 14: the phoenixgirls are setting fire to the dmv!! Its enrichment for them dont worry :)

Mutual 15: server room wire gore images

Mutual 16: 10 ur old meme

Mutual 17: vaguing me

Mutual 18: Let me learn you a thing! Yes i am 35 years old

Mutual 19: people need to stop trying to erase crowley's influence on 20th century magical practice, like we KNOW he's a lying piece of shit but if you wanted to avoid this stuff you should have stayed out of western occultism and kept watching steven-

Mutual 20: if you guys were less panphobic we could still listen to hamilton without getting clowned on

669 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Boxing Day pro-Palestine demonstrators met customers at the Zara sale in the Westfield shopping centre, in Stratford, east London. They were not there to wish them the compliments of the season.

‘Bombs are dropping while you’re shopping,’ they chanted, as police stood by to make sure the protests did not turn violent. ‘Zara is enabling genocide,’ their placards read.

Quite what they wanted bargain hunters to do about the Israeli forces bombing the Gaza Strip, they never said. Lobby their MPs? Politicians are on their Christmas holidays. Join the Palestinian armed struggle? It was unclear whether the shopping centre had a Hamas recruitment office.

But on one point the demonstrators were certain: no one should be buying from Zara. Even though the fashion chain has not encouraged Israel’s war against Hamas, earned income from it, or supported Israel in any material way, it was nevertheless “exploiting a genocide and commodifying Palestine's pain for profit”.

Zara, in short, has become the object of a paranoid fantasy: a QAnon conspiracy theory for the postcolonial left.

The Zara conspiracy is an entirely modern phenomenon. It has no original author. Antisemitic Russians sat down and wrote the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the early 20th century. There was an actual “Q” behind the QAnon conspiracy: a far-right activist who first appeared on 4chan message boards in 2017 to claim that a cabal of child abusers was conspiring against Donald Trump.

The Zara conspiracy was mass produced by social media users: an example of the madness of crowds rather than their supposed wisdom. The cause of the descent into hysteria was bizarre.

In early December Zara launched an advertising campaign featuring the model Kristen McMenamy wearing its latest collection in a sculptor’s studio. It clearly was a studio, by the way, and not a war zone in southern Israel or Gaza. McMenamy carried a mannequin wrapped in white fabric. The cry went up that the Spanish company was exploiting the suffering of Palestinians and that the mannequin was meant to represent a victim of Israeli aggression wrapped in a shroud.

The accusation was insane. No one in the photo shoot resembled a soldier or a casualty of war. Anyone who thought for 30 seconds before resorting to social media would have known that global brands plan their advertising campaigns months in advance.

Zara said the campaign presented “a series of images of unfinished sculptures in a sculptor’s studio and was created with the sole purpose of showcasing craft-made garments in an artistic context”. The idea for the studio setting was conceived in July. The photo shoot was in September, weeks before the Hamas assault on Israel on 7 October.

No one cared. Melanie Elturk, the CEO of fashion brand Haute Hijab, said of the campaign, ‘this is sick. What kind of sick, twisted, and sadistic images am I looking at?’ #BoycottZara trended on Twitter, as users said that Zara was ‘utterly shameful and disgraceful”’.

To justify their condemnations, activists developed ever-weirder theories. A piece of cardboard in the photoshoot was meant to be a map of Israel/Palestine turned upside down. Because a Zara executive had once invited an extreme right-wing Israeli politician to a meeting, the whole company was damned.

Astonishingly, or maybe not so astonishingly to anyone who follows online manias, the fake accusations worked. Zara stores in Glasgow, Toronto. Hanover, Melbourne and Amsterdam were targeted.

What on earth could Zara do? PR specialists normally say that the worst type of apology is the non-apology apology, when a public figure or institution shows no remorse, but instead says that they are sorry that people are offended. Yet Zara had not sought to trivialize or profit from the war so what else could it do but offer a non-apology apology? The company duly said it was sorry that people were upset.

“Unfortunately, some customers felt offended by these images, which have now been removed, and saw in them something far from what was intended when they were created,” it said on 13 December, and pulled the advertising campaign

That was two-weeks ago and yet still the protests in Zara stores continue. On 23 December activists targeted Zara on Oxford Street chanting , 'Zara, Zara, you can't hide, stop supporting genocide', even though Zara was not, in fact, supporting genocide. On Boxing Day, they were at the Stratford shopping centre.

Zara has apologised for an offence it did not commit. There is no way that any serious person can believe the charges against it. And yet believe them the protestors do. Or at the very least they pretend to believe for the sake of keeping in with their allies.

Maybe nothing will come of the protests. One could have argued in 2017, after all, that QAnon was essentially simple-minded people living out their fantasies online. Certainly, every sane American knew that there was no clique of paedophiles running the Democrat party, but where was the harm in the conspiracy theory?

Then QAnon supporters stormed the US capitol in January 2021. Will the same story play out from the Gaza protests? As far as I can tell, no one on the left is challenging the paranoia. I have yet to see the fact-checkers of the BBC and Channel 4 warning about the fake news on the left with anything like the gusto with which they treat its counterparts on the right.

To be fair, the scale of disinformation around the Gaza war is off the charts, and it is impossible to chase down every lie. But when fake news goes from online fantasies to real world protests, from 4chan to the Capitol, from Twitter to the Westfield shopping centre, it’s worth taking notice.

Sensible supporters of a Palestinian state ought to be the most concerned. No one apart from fascists, Islamists and far leftists believes that Israel should not defend itself. And yet the scale of its military action in Gaza is outraging world opinion. Mainstream politicians, who might one day put pressure on Israel, remain very wary about reflecting the anger on the streets.

They look at the insane conspiracy theories on the western left and see them as no different from the insane conspiracy theories that motivate Hamas, and they back away.