#anti chador

Text

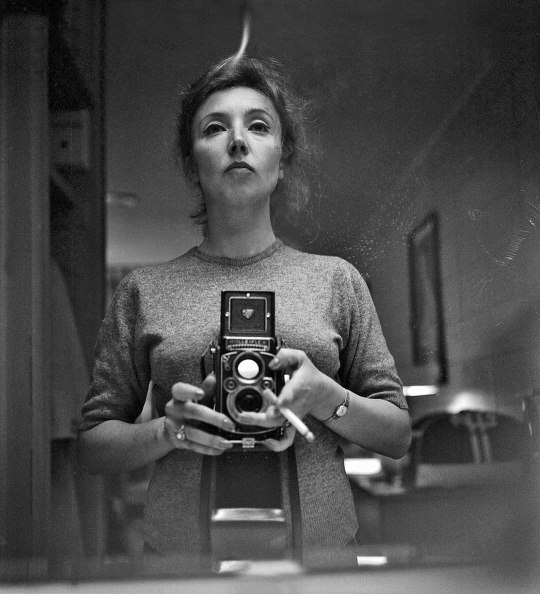

Oriana Fallaci (29 June 1929 – 15 September 2006) was an Italian journalist and author.

She rightfully critcized Islam and its oppressive rules.

During her 1979 interview with Ayatollah Khomeini, she addressed him as a "tyrant", and managed to unveil herself from the chador:

OF: I still have to ask you a lot of things. About the "chador", for example, which I was obliged to wear to come and interview you, and which you impose on Iranian women... I am not only referring to the dress, but to what it represents, I mean the apartheid Iranian women have been forced into after the revolution. They cannot study at the university with men, they cannot work with men, they cannot swim in the sea or in a swimming-pool with men. They have to do everything separately, wearing their "chador". By the way, how can you swim wearing a "chador"?

AK: None of this concerns you, our customs do not concern you. If you don't like the Islamic dress, you are not obliged to wear it, since it is for young women and respectable ladies.

OF: Very kind (of you). Since you tell me that, I'm going to immediately rid myself of this stupid medieval rag. There!

Truly a badass feminist icon.

#oriana fallaci#radfem#radical feminism#radfem safe#radblr#radfems do interact#feminism#radfems do touch#women's rights#women's liberation#anti islam#anti hijab#hijab free#chador#anti chador#islam is evil#islam is not a religion of peace#women's oppression#female journalist#iran#iranian women#iranian girls#islamic republic of iran#Ayatollah Khomeini#iranian revolution#anti religion#islam is bad#fuck islam#islam#muslim

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The oldest Sufi shrine in Delhi has been demolished.

"The earliest Sufi Shrine in Delhi - belonging to a relative of Prithviraj Chauhan and dating from BEFORE the Turkish conquest - has been Demolished by the Delhi Development Authority in an "anti encroachment" drive.

In the late 12th century, a group of Afghan pastoralists, suddenly burst onto the world stage. In a matter of years, they toppled their rulers of Ghazni and seized major Persian cities like Herat, and then established the major Indian sultanate in Delhi.

We often think of this "Islamic invasion" as the start of the Muslim presence in India. Yet recent scholarship has shown that by the time of Ghori's conquest of Delhi, Muslims were already a central part of Indian society

Some of the earliest mosques are found in Kerala, dating from a few decades after the prophet Muhammad's death. Tamil Pallava, Chola and Pandya kings all built sizeable mosques

Delhi also had a single sufi shrine before the Afghan conquest - this one.

Until 31 January, when it was demolished, the shrine of Baba Haji Rozbih had been located by the Fateh Burj, or Victory Gate of Lal Kot. The grave next to it under a reddish Chador belongs to his female disciple Bibi. Bibi was said to be a close relative of Prithviraj Chauhan who embraced Islam under the aegis of Haji Rozbih.

This demolition is an UTTERLY MINDLESS LOSS and complete cultural desecration.

What's more the "anti encroachment" drive is apparently scheduled to include the Aashiq Allah Dargah dated to 1317AD which is where the great Punjabi Saint Baba Farid used to meditate, and his small 'chillagah' is still visible here.

Please do share and write about this so we can save what remains! "

- from the historian Sam Dalrymple .

...

This is the third Islamic structure to be demolished in Delhi this month. Isn't it funny how only certain structures are the victim of anti- encroachment drives? This is part of a planned programme by the current right-wing government of India that is violently islamophobic and wants to create a hindu ethnostate modeled after Israel.

#india#desi tumblr#desiblr#south asia#punjab#sufi#sufism#islam#delhi#new delhi#anti-hindutva#anti-bjp#islamophobia#anti hindutva#anti bjp

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is nauseating. The French government has banned the wearing of abayas to school. This includes both students and faculty. Teenagers and grown women alike are now no longer allowed to wear one of the few things they have left under strict French laicity laws. If it is anything like the restrictions against hijabs, burkas, chadors and niqābs, this means these women will not be allowed inside a school building with one on, and will be restricted from entering the premises while wearing one.

Unlike a hijab or other headcovering, this cannot simply be removed. Students are going to be sent home and miss educational hours because the government said they cannot wear a dress, because of religious backgrounds, entirely ignoring cultural backgrounds and the fact that it is one of the few things these girls have left to hold on to their culture and faith.

I school in a large city. Over half the women in my classes sport an abaya, because they are already forced their head coverings off at the door in the name of peace and laicity, are forced to give in to Islamophobic, European sentiment, and now they cannot even wear a long dress. Teachers who give up their prementioned garments for the name of educating the youth, now have to give this up as well. The French government also bans burkinis and any sort of modest, covering bathing suit, and has for years, in the name of 'hygiene', instead pushing for speedos and two pieces.

They give different excuses, but it is all the same, and this is the most blatant form yet. This dress has been banned for women and children to wear in school because christians think it shows too much faith. We eat fish on fridays as a nationwide standard, and this shows too much religion. This dress in the eyes of the french government, is anti secularist. This is horrifying, and I haven't seen anything about it on Tumblr yet, but I am disgusted. This is Islamophobia, always has been, and terribly, continues to be.

English translation under the read more.

Header:

3rd Change

First paragraph:

The abaya, an article of clothing with widespread origins in several Gulf States and the Maghreb, will be prohibited in all educational establishments in France.

Second paragraph:

The government has judged that this article of clothing is religious garb and thus contradictory to laicity.

[Vêtement could also be garment, whatever you prefer.]

#emergency broadcast system#rentrée scolaire#rentrée 2023#i dont even know what to tag this i just want to spread the word because i need people to understand what happens in france.#france#francais#sorry if this is not well worded i just found out and i am jacks raging bile duct!

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

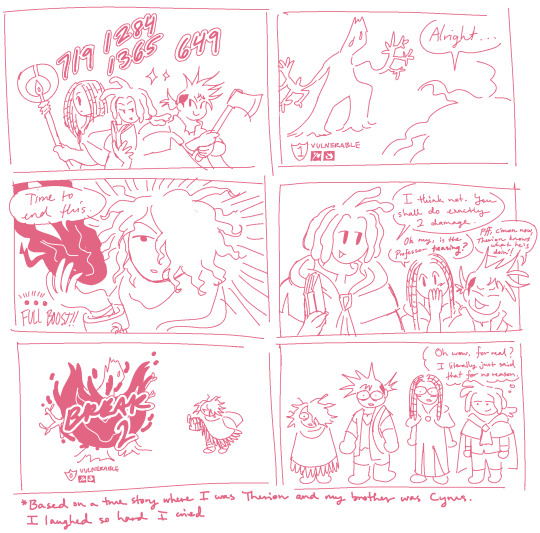

[Image description: Digital drawings featuring a variety of characters from Octopath Traveler. There are full descriptions of all images under the cut. End image description.]

you know what? octopath is the only game i’ve ever played that accurately depicts what happens when you eat an olive. thank you octopath

[Image description: First is a drawing of Primrose, Ophilia, Kit, and Lyblac, with certain aspects of their designs altered. Primrose steps forward in a beguiling pose. She wears a red dress with a short, layered front and a long, flowing back. She wears gold jewelry including three rings on her right hand, a headband with a flower adornment, and a belt around her waist. Her knife is strapped to her right thigh and she wears medieval women's knee-high hose, black with red garters, beneath her sandals. A note next to her reads, "Elements taken from 15th century Italian illustration of dancers."

Ophilia holds up her staff. A long lace veil covers her head and is tied beneath her chin. She wears a brooch on the left side of her cloak. The notes next to her read, "Mourning veil worn for varying lengths of time depending on relation (parent = 1 year). Mourning brooch of braided hair worn indefinitely by choice."

Kit's design is much the same. He looks with slight wonder over at Lyblac, who stands tall with her hands clasped and a blood red halo around her head. She wears a black escoffion and a black and red houppelande with dagged sleeves.

Second is a drawing of Mattias, Esmeralda, and Lianna, with certain aspects of their designs altered. A note above Mattias and Esmeralda reads, "Obsidian fashion is ahead of the times (entirely because I mistook Mattias's sprite as having a ruff)." Along with the ruffs around his neck and wrists, Mattias wears a yellow doublet, orange jerkin, a gold necklace with a red jewel pendant, black paned trunkhose, a blue cape with a pattern of yellow stars, and a black cap with a blue feather. He has a confident expression, with one hand on his hip and the other splayed outwards. The note next to him reads, "If he's posing as a merchant he needs a stupid little hat and plume."

Esmeralda holds up a black dagger in one hand and clenches the other into a fist with an irritated expression. She wears a French hood, a black gown with slashed sleeves, and gold jewelry around her neck and waist. The gown's skirt is full on the left side, layered and translucent in the middle, and has a slit on the right side to show the crow tattoo on her thigh. The note next to it reads, "Put it back." Then it points to Mattias's left leg and says, "He has it too."

Lianna has a neutral expression as she holds up Aelfric's Lanthorn with a dark flame burning within. She wears the robes of a vestal of Galdera. The note next to her reads, "Love how he made her a special little anti-cleric outfit (takes off mourning veil)."

Third is a drawing of Alfyn smiling in profile, showing off his messy, dirty blonde hair with the sides shaved. To the right is a bouquet of seven white lilies. The text above them reads (in all caps), "Donio sam ja sedam ljiljana / Majko da li znaš još sam sam / Majko da li znaš još sam sam / Spava malena slatka glavica / Majko pokrila mi je travica / Majko pokrila mi je travica."

Fourth is a collection of doodles. 1. Lyblac and Kit stand in front of the Gate of Finis. Kit asks, "what are u trying to say." Lyblac points to the Gate with a smile and says, "go here." Kit asks, "in the dark ?" Lyblac says, "go in the dark."

2. Galdera says, "AND I'M BAD!" The souls around the Omniscient Eye say, "MEAN!! GREEN!! BAD!!"

3. To the left, Therion holds up a pair of rivet spectacles to his eye. To the right, he wears a paisley-patterned headscarf and a chador over it with a small smile. The text reads, "His chador swag. Based on an outfit my friend saw me wearing in a dream cuz I thought he'd look cute in it."

4. Two anthropomorphic birds wear cloaks and hold up staves. The first one has a neutral expression and the second looks more aggressive. The text reads, "My brother mistook Believer I + II in Seaside Grotto for bird people and now I wish they really were bird people."

5. A screenshot of a post by user tlirsgender: "Consider: a gay dude and a lesbian who are BEST friends and also dating the same person but not each other because they are a gay dude and a lesbian but their mutual partner has a weird enough gender for it to work. Polycule that’s lgbt like all at once." Beneath it, Alfyn and Primrose happily shake hands while Therion stands in the background with a neutral expression. The note next to them reads, "This concept is so funny to me that it kinda loops around to being compelling."

6. Cyrus smiles and quirks one eyebrow while pointing upwards. The text reads, "LOVE IS IN THE AIR? / WRONG! LIGHTNING BLAST."

7. Primrose leans back on a counter and Therion sits on a stool with his hands clasped. Both look miserable and share a thought bubble which says, "I'm the only bitch here who's incapable of love and sincerity." They glance at each other curiously, and then return to being miserable and sharing a thought bubble which says, "Nah I'm way more sick and twisted than you."

Last is a comic. In the midst of a battle, Ophilia holds up her staff and does 719 damage; Cyrus holds up a tome and does one hit of 1284 damage and another of 1365 damage; and Alfyn holds up his axe and does 649 damage.

One enemy remains: a Creeping Treant with one shield and vulnerabilities to axe and fire. In the foreground, Therion says, "Alright..."

He prepares a full-boosted Wildfire and says, "Time to end this."

Cyrus shuts his tome and says blithely, "I think not. You shall do exactly 2 damage." Ophilia holds a hand over her mouth and blushes, saying, "Oh my, is the Professor teasing?" Alfyn laughs, "Pff, c'mon now, Therion knows what he's doin'!"

Therion uses Wildfire on the Treant and breaks it, doing 2 damage.

Therion, Alfyn, and Ophilia stand lined up and look very startled, while Cyrus smiles mildly and thinks, "Oh wow, for real? I literally just said that for no reason."

The note beneath the comic reads, "*Based on a true story where I was Therion and my brother was Cyrus. I laughed so hard I cried." End image description.]

#octopath traveler#primrose azelhart#ophilia clement#kit crossford#lyblac the witch#mattias ot#esmeralda ot#lianna clement#alfyn greengrass#galdera the fallen#therion ot#cyrus albright#beast ot#drawings#im not a fashion historian or character designer but everybody MUST accept my vision of socks and sandals primrose. NOW#//#parental death

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Armin Navabi

Published: Feb 6, 2023

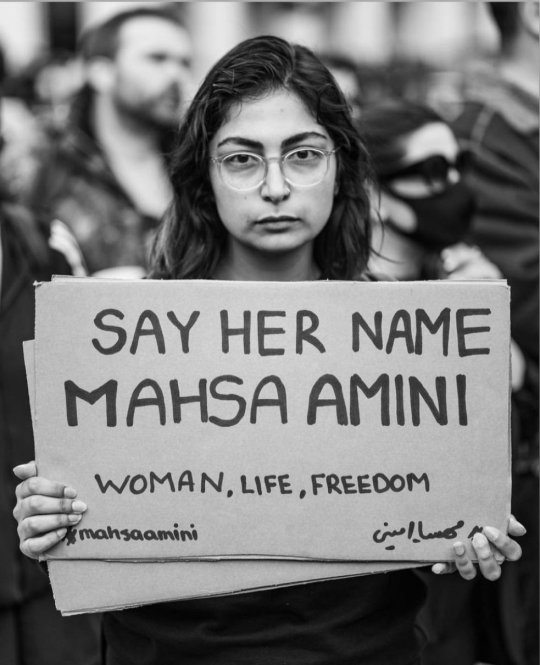

A protest becomes a revolution when the protesters have hope, determination, and unity. This is why sowing division is a tried and true tactic used by unpopular leaders the world over to cling to power. This has been the Iranian regime’s recipe for survival for the past four decades. They turn different groups against each other by invoking ancient hatred and historical tensions. They do not invent the hate, but they inflame and weaponize it, pitting men against women with religion, ethnicities against each other using the fear of separatist movements, and religious people against secularists with warnings of degeneracy and depravity.

But now everything has changed. A 22-year-old woman's brutal death at the hands of Iran's morality police has laid waste to 40 years of efforts to divide and conquer. The recent protests — or revolution, as many Iranians insist — began after Mahsa Amini died in police custody after being arrested for her "improper" hijab (head covering) while visiting Tehran from the Kurdistan Province in Iran. As news spread and the people of Iran watched in horror, the same thought crossed their minds: “That could be my daughter.” “That could be my sister.” Against all odds, in a country where division over religion, ethnicity, and gender has been common, many Iranians have put aside their differences and are now united in one goal. Mahsa Amini's murder has brought people from all walks of life into the streets across Iran, demanding the end not merely of the morality police, but of the regime itself. Some loose strands of hair were enough to get Amini killed. They were also enough to bind a divided nation together in solidarity.

I'm not in the mood to talk about the Nobel Prize.

https://t.co/8aq9SDhFRT

Women young and old are tearing off and burning their hijabs in the streets in protest against the Islamic regime. Even those unable to walk are joining the protests, as demonstrated by this woman in a wheelchair chanting, "Don't be afraid, don't be afraid, we are together."

For years, the Islamic Republic has told the people that Iran will be fractured and ultimately torn apart by Arab, Turkish, Baluch, and mainly Kurdish separatist groups if the regime falls. Leveraging Iranians' strong desire to protect their borders, the regime scares people into support by fearmongering about the potential success of Kurdish separatist groups. You may have some disagreements with us, but we are the only thing standing in the way of anarchy. But the spell of such propaganda seems to have broken. Non-Kurdish protesters across Iran now chant in support of Kurdish Iranians, including "Woman, Life, Freedom", a phrase which is Kurdish in origin. This slogan reflects the spirit of the protests and has captured the attention of people worldwide. The fact that this Kurdish chant is shouted across Iran’s ethnic groups highlights the unity among protesters.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, which ushered in the current theocratic regime, also divided people along religious lines. In my childhood, I was introduced to the dichotomy: my friends and family were more liberal-minded and anti-regime, while the very religious pro-regime schools and media attempted to brainwash me. Being religious always seemed to go hand in hand with being pro-regime, and yet, more and more, the devout have been joining the anti-regime ranks for the past few years. These demonstrations have exposed this trend. Among those who have been arrested are some of the most pious, including women who wear the chador (a type of hijab that very religious women wear in Iran). Standing shoulder to shoulder with them are religious men.

pic.twitter.com/IXIMuEEy6k

Despite all the laws and regulations that segregate and set them against each other, the men and women of Iran have come together to show the regime that a desire for freedom transcends gender and tradition. We have seen religious men appeal to their fellows by invoking the injustice inflicted on Imam Hussain, the martyred grandson of the Prophet Muhammad revered by Shia Muslims, imploring them to rise and stand against the injustice done to Mahsa. One man shouted that any man who doesn't stand up today is the same as those who betrayed Imam Hussain, and they will not be able to look him in the eyes in the afterlife. Along the same lines, a former TV presenter for the regime reminded people of the upcoming anniversary of the Prophet Muhammad's demise, showing respect for the prophet and demonstrating his religious sentiments, but then warning protesters to be on guard for false flag operations which might take the form of government agents burning the Quran and pulling chadors from women while pretending to be anti-regime protesters. His warning is an obvious indication that he supports the protesters, but he makes it even more explicit when he includes himself among them by saying, "We are fighting for freedom."

One area of concern is over LGBT issues. Contrary to the wishes of the regime, more and more Iranian LGBT activist groups have been springing up in recent years. Still, religious and traditional Iranians lag far behind on LGBT rights, and it remains a polarizing and unpopular issue. In an attempt to build the broadest possible coalition against the regime, some supporters are asking LGBT members to put their LGBT activism on the back burner, including requests that people not protest with rainbow flags [mainly in solidarity protests outside of Iran] and to try to blend in with others so that the regime can't use them to separate religious and traditional protesters from their ranks. The process of political sausage-making is rarely pretty, though it stands to reason that, should the regime fall, a more secular and democratic government would invariably be better for LGBT Iranians.

زیبایی ببینید:

مردها شعار میدن

زن، زندگی، آزادی

زنان جواب میدن

مرد، میهن، آبادی.

امروز دانشگاه علوم پزشکی شیراز#مهسا_امینی pic.twitter.com/1tdp3Yqm7Q

The central theme of the uprising has been putting aside differences and uniting against the regime. In a moment that perfectly captures the message of unity, you can hear men chant “Woman, Life, Freedom” and the women respond “Man, Nation, Prosperity.” No matter the class, religion, ethnicity, or gender, Iranians are standing together. It's your turn to stand with them. Use the English and Persian hashtags, #MahsaAmini and #مهسا_امینی to bring attention to what's happening in Iran. Lend your voice to the chorus to cast down repressive theocracy. Today, we are all Mahsa.

==

Funny how people who are actually oppressed aren't competing against each other for oppression points.

The universality and unanimity of this revolution might be one of the most remarkable things of all. Feminists are being asked to put away the man-hate slogans, LGBT people are being asked to put away the rainbow flags, because those will factionalize the movement, put men and more conservative religious types off-side, and create opportunities for the regime to divide and conquer. And they are. Because those are fights for another day. It's Iran, together, against the regime.

"Be with the people, one hand and one form with the rest."

Iran is a country that will be free.

Remember the Women's March in the US in 2017? Its most memorable symbol was a woman in a hijab, it featured a pro-Sharia Islamist among its most vocal representatives, and it descended into endless episodes of Intersectional madness, such as the pussyhat fiasco, which resulted in a furore, an apology and the deletion of the knitting pattern when feminists and Gender Studies professors insisted it wasn't sufficiently inclusive to women with penises. And also racism. Somehow. 🤡 When you're privileged and free, and your oppression is imaginary, the fight to the bottom is a mad scramble.

#iran#islam#iran revolution#iranian revolution#mahsa amini#islamic republic of iran#iranian regime#iran regime#islamic regime#free Iran#iran protests#iranian protests#religion#hijabi#hijab#woman life freedom#man nation prosperity#religion is a mental illness

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

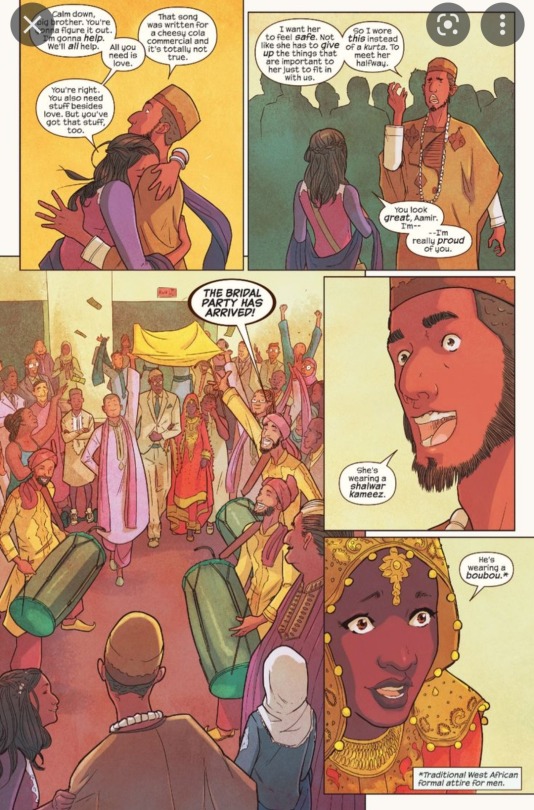

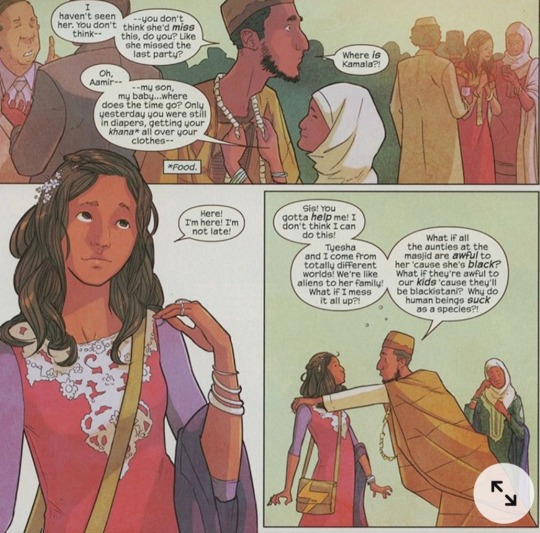

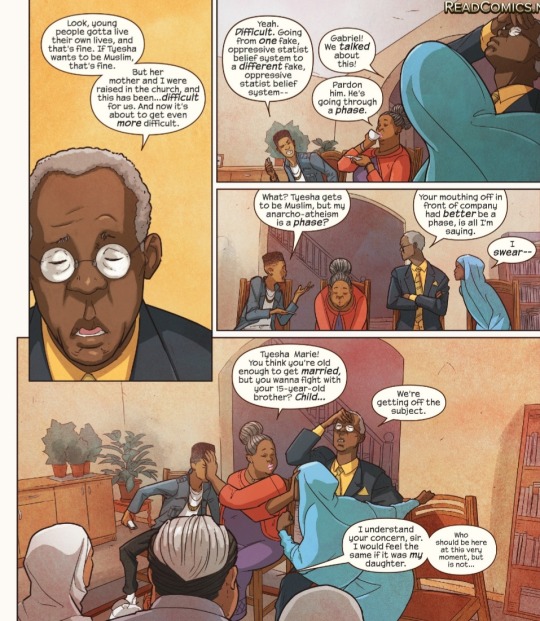

Sorry?? How could they fuck up Tyesha and Aamir's wedding like that?

Why is Tyesha being expected to dress according to desi culture, the scene where people are putting her henna on and Aamir's just like where's my shoes? Where's the love?

Compare it to this:

Do you see? The exchange of cultures? The surprise on their faces? No expectation, two people choosing each other, choosing to appreciate the other's culture and background.

Meanwhile mcu Aamir dancing in his shalwar kameez in a bollywood style dance sequence, like sorry but comic Aamir would never, music is haram you know, shaytaan shaytaan!

Also Nakia wearing it too, i think it would be beautiful if she wore a kaftan i think celebrating other cultures is beautiful. Also she was dancing too and again comic Nakia would never.

Another thing is the complete lack of discussion on anti-black racism. In the show it's Aamir's wedding basically, Tyesha is there as a background character. But in the comic they actually discuss the anti-black racism that's rampant in a lot of non-black muslim communities.

Like Aamir basically has to fight for Tyesha and he's so worried that his family and community won't accept her. (Also the fair and lovely line is so based)

Also like look at what Tyesha is wearing, no make up, no turban, fully covered in a jilbab/chador. Of course that was too much for the mcu no no she needs to show more skin. Clearly desperate for the appproval of white palates.

Also look at this:

In the show right, you literally dont see her parents which is such a fucking shame. Theyre not characters, theyre just there to clap along. Look here though, they've got their own culture and they're struggling with Tyesha seemingly breaking away from that.

Also Tyesha's brother (unnamed) in the show is a lot younger and wears a thobe in one scene and a shalwar kameez in another. Lmao you wouldn't catch Gabriel dead in one of those. The Hillman's have two kids veering off in very different directions and it just feels so real and normal.

In the end the two families reconcile and Mr. Hillman says: long live the Hillman-Khans and isn't that beautiful. Literally where was any of this.

To end I just want to show this scene from the comics of Tyesha and Nakia debating the meaning of hijab which we will never get in the mcu bc the mcu sucks and can't show anything other than a turban with makeup and is about as deep as a puddle.

#sorry but ms marvel was literally groundbreaking for muslim rep#and mcu decided to pave it over#ms marvel#mcu critical#mcu#literally go read the comics#racism#feel free to correct me on any terminology

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viewing Response 2: A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night

Ana Lily Amirpour’s, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), is an Iranian vampire Western film, that also serves as a Feminist anti-hero search for vengeance in a patriarchal society. The film is set in the fictional Iranian city of “Bad City”, and follows a young female vampire who roams the streets and takes vengeance against men who have wronged or disrespected women. The film is known for its non-traditional storyline, highlighting the experience of a minority woman, whose goal is to defeat the patriarchy through murdering men who mistreat women. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night has also been analyzed as a subversion of classical cinema, and societal norms, making it a “queer utopia”, as stated by Shadee Abdi and Bernadette Marie Calafell in “Queer Utopias and a (Feminist) Iranian Vampire: A Critical Analysis of Resistive Monstrosity in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night”. In the article, they mention how the elements that make it a queer utopia lie within the mise en scene, such as the lack of color, which creates an eerieness, and the amount of silence within the film, which adds tension to the already ominous scenes. Another element is costume design, which is extremely important for the vampire’s character. She is analyzed as a reimagination of a superhero, with her chador taking place of a cape (Abdi). Giving this article of clothing, which is significant for many Middle-Eastern and Muslim women, the same power that the cape has been seen to have in superhero stories, subverts ideas of power that are typically associated with men and women, specifically of color around the world. It queers the traditional, hegemonic, systems that are put in place, and are often perpetuated through art, specifically through formal elements. @theuncannyprofessoro

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yah this is funny but also infuriating because the amount of anti blackness within non-black Muslim communities is infuriating.

Anything related to blackness is "HaRaM!!!!"

Mod TZ

#mod tz#q#thick curly hair? haram#big bump under your hijab or burqa or niqab or chador cuz of thick hair? haram#fashion popularised by black ppl like bandannas or durags over the hijab? haram#listening to hip hop or rnb? haram#supporting black creators who arent Muslim? haram#attending blm protests? haram#islam#anti black racism#antiblackness#im Muslim btw#not being islamophobic so if u r islamophobic pls dont bother interacting

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chi è Emma Bonino?

Fu Marco Pannella, suo mentore, a dirle la cosa più cattiva, a demolire il suo protagonismo autocelebrativo. Emma Bonino, infatti, aveva appena annunciato che lei «aveva un tumore» ma che avrebbe eroicamente continuato le sue battaglie eccetera; e allora Marco, al Corriere Della Sera, disse così: «Io di tumori ne ho due», e il resto della frase (frase pannelliana, riportarla tutta brucerebbe l'articolo) stava a dire: ho due tumori e non rompo i coglioni, perché ci vuole coraggio. Poi d'accordo, i due erano in dissidio politico.

Ma poi Pannella per quei tumori ci è morto, e resta politicamente immortale, la Bonino è viva ma politicamente è morta. Non esiste più. Non rappresenta più niente, le nuove e semi-nuove generazioni non sanno chi sia. Lei di questo non ha percezione, e sono cose che succedono a certi anziani pieni di sé, fa un po' pena, e speriamo che lei non legga questo articolo.

Lo scriviamo a margine della presunta notizia che Emma Bonino e Benedetto Della Vedova hanno lasciato +Europa, che non è un canale televisivo ma uno dei partitelli riformatisi dopo il Big Bang dello storico Partito Radicale. La Bonino ha ventilato l'ipotesi di dimettersi da senatrice (ventilato e basta) mentre Benedetto Della Vedova, per cui lo scrivente ha la massima stima, e che di +Europa era il segretario, ha abbandonato la poltrona anche perché è diventato sottosegretario agli Esteri del governo Draghi. Nota: al prossimo congressino del partito, la Bonino e Della Vedova sarebbero stati fatti fuori lo stesso.

LE LOTTE

Ora, nel proseguire una cosiddetta narrazione su Emma Bonino, si tratta di far convivere il rispetto per le sue battaglie civili (condivise perlomeno da una parte di italiani e di lettori) con la trasformazione di Emma Bonino anzitutto in una donna di potere (tendenza voltagabbana) inconsapevole di essere perlopiù una reliquia di se stessa e della sua arroganza.

Che fatichi a scendere dal proprio piedistallo è anche comprensibile. È stata una figura storica del femminismo italiano (quello vero) e più volte parlamentare, europarlamentare, Commissario europeo dal 1995 al 1999 (molto apprezzata) e ideatrice della Corte penale internazionale, delegata per l'Italia all'Onu, ministra del commercio internazionale, nel 2011 fu l'unica italiana inclusa da Newsweek tra le «150 donne che muovono il mondo», dopo Pannella è stata l'unica a veder ribattezzare una lista col suo nome («Lista Bonino») e a prendere anche dei voti.

Da principio fondò associazioni abortiste e praticò personalmente aborti quando ancora erano illegali, cosa per cui molti cattolici la odiano ancora. Marco Pannella la trasformò in parlamentare a soli 28 anni. Partecipò alla disgraziata campagna contro il capo dello Stato Giovanni Leone, chiedendogli scusa quando lui compì 90 anni.

Compartecipò a tremila iniziative per combattere la fame nel mondo, si fece arrestare dai comunisti polacchi per il suo sostegno a Solidarnosc, fece approvare mozioni contro le mine anti-uomo che mutilavano i civili, contribuì a istituire il Tribunale internazionale per i crimini nell'ex Jugoslavia, incontrò il Papa, il Dalai Lama, fu segretaria del Partito Radicale quando ancora esisteva, riuscì a farsi appoggiare dal governo Berlusconi per diventare commissario europeo, sconfinò in cento Paesi messi sotto embargo o colpiti da feroci dittature, contribuì a ridimensionare i disastri compiuti dal commissario europeo antidroga Pino Arlacchi, fece propaganda contro le mutilazioni genitali femminili (infibulazioni) e poi tornò alla politica romana, si candidò qua e là: la Bonino ne ha fatta una più del diavolo e di Marco Pannella, stratega di ogni cosa ma sempre un passo indietro.

Pannella non diventò mai un uomo di potere, lei sì. Pannella non scese mai a compromessi, lei sì. Anche così ottenne incarichi e divenne «Emma for President». Lei probabilmente non rinnegherebbe nulla, ma non le piacerebbe che ri-mostrassero le foto in cui praticava aborti con una pompa per bicicletta e aspirava il feto in un barattolo di marmellata.

Non le piacerebbe dover rispiegare come potè fare il ministro nel centrosinistra dopo esser stata eletta nel centrodestra. Come potè, cioè, essere eletta coi berlusconiani e prenderne i voti, lasciare il seggio per fare il commissario europeo sino a rientrare a Roma sulla sponda del centrosinistra, e passare a sostenere Romano Prodi che le offrì un ministero. E, anni dopo ancora, diventare una delle più convinte sostenitrici di Mario Monti e dell'ingresso della Turchia in Europa.

L'AUTO BLU

Marco Pannella, negli ultimi tempi (suoi), di lei disse il peggio: «Ho parlato coi medici del suo tumore, e posso dire che non ha motivo per essere allarmata Il suo problema è quello di far parte del jet set internazionale Io vado in giro a piedi o in taxi, non ho auto nera o blu». Sempre negli ultimi tempi (suoi), Pannella disse che «Io e lei non ci consultiamo, non ci sentiamo mai, con me non parla Sono intervenuto io per farla inserire nel governo Letta, in tutte le sue nomine c'entravo sempre io. Lei invece lavora molto, ma mai con noi».

Poi c'è un episodio che per qualche radicale è uno spartiacque: vedere Emma Bonino festeggiare l'anniversario del Concordato a Palazzo Borromeo, questo dopo che aveva combattuto il Concordato per tutta la vita, da anticlericale militante. Sino a poco tempo prima, ogni 20 settembre, Emma festeggiava la Breccia di Porta Pia coi compagni anticlericali. Poi eccola presenziare all'anniversario della firma dei Patti Lateranensi all'ambasciata italiana presso la Santa Sede: c'erano le più alte cariche ecclesiastiche e naturalmente il segretario di Stato Vaticano.

Era ministro, certo, ma poteva mandare un sostituto. Ancora oggi, se andate sul sito dei Radicali, trovate tutto l'architrave della campagna storica contro i Patti Lateranensi e il Vaticano. I Radicali peraltro sono stati quelli che hanno portato al Parlamento Europeo il problema dell'Imu che il Vaticano non pagava.

Chi è Emma Bonino? È una signora che nel 1979 manifestò davanti all'ambasciata dell'Iran contro l'imposizione del chador alle donne iraniane: e che il 21 dicembre 2012 però era in Iran e indossava il velo per incontrare le autorità iraniane. È una signora che incontrò il Dalai Lama ma che restò zitta quando il governo Prodi, di cui faceva parte, nel 2006 rifiutò di incontrare il Dalai Lama per non contrariare gli amici cinesi. Chi è la Bonino? La risposta peggiore è quella attuale, del 2021, perché non fa che riformulare la domanda: Emma Bonino? Chi è?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reza Shah - Wikipedia

Along with the modernization of the nation, Reza Shah was the ruler during the time of the Women's Awakening (1936–1941). This movement sought the elimination of the chador from Iranian working society. Supporters held that the veil impeded physical exercise and the ability of women to enter society and contribute to the progress of the nation. This move met opposition from the Mullahs from the religious establishment. The unveiling issue and the Women's Awakening are linked to the Marriage Law of 1931 and the Second Congress of Eastern Women in Tehran in 1932.

Reza Shah was the first Iranian Monarch in 1400 years who paid respect to the Jews by praying in the synagogue when visiting the Jewish community of Isfahan; an act that boosted the self-esteem of the Iranian Jews and made Reza Shah their second most respected Iranian leader after Cyrus the Great. Reza Shah's reforms opened new occupations to Jews and allowed them to leave the ghetto.[41] This point of view, however, may be refuted by the claims that the anti-Jewish incidents of September 1922 in parts of Tehran was a plot by Reza Khan.

The central "pillar" was the military, where the shah had begun his career. The annual defense budget of Iran "increased more than fivefold from 1926 to 1941." Officers were paid more than other salaried employees. The new modern and expanded state bureaucracy of Iran was another source of support. Its ten civilian ministries employed 90,000 full-time government workers.[50] Patronage controlled by the Shah's royal court served as the third "pillar". This was financed by the Shah's considerable personal wealth which had been built up by forced sales and confiscations of estates, making him "the richest man in Iran". On his abdication Reza Shah "left to his heir a bank account of some three million pounds sterling and estates totaling over 3 million acres.

Nem szarozott. Föld��n hált a palotájában, a katonáival egy kondérból evett, modernizált és mészárosviktornál is többet lopott.

The name Iran means "Land of the Aryans".

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Examining Layers of Meaning in Rebellious Silence.

This is my essay on meaning for critical studies. I chose this artist for her photographic images that raised many questions for me when I first came across her work. I love the layering of script on photograph, the staged manner of her compositions. They are so clearly staged that it calls for further interrogation...what is she trying to convey and why?

Examining Layers of Meaning in Rebellious Silence

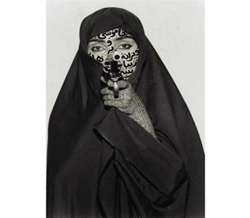

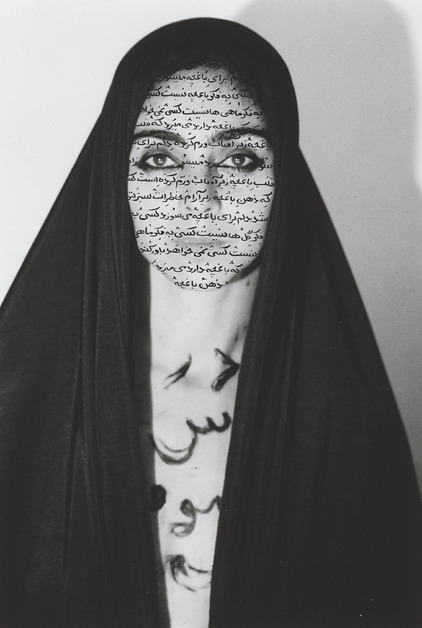

Rebellious Silence, 1994, Shirin Neshat.

Ink on LE silver gelatin print, (131.8 x 92.7 x 4.8 cm).

Introduction

In this essay I will examine how meaning is made and translated in an image by Shirin Neshat titled Rebellious Silence, part of the Women of Allah series. I intend to evaluate and analyse the image employing Roland Barthes theories of semiotics and intertextuality.

Theory and Framework

Barthes was one of the leading theorists of semiotics which is the study of signs. In this context, a sign refers to something which conveys meaning – a written or spoken word, a symbol or a myth (Robinson, 2011). Semiotics is concerned with anything that can stand for something else, it is an interpretation of everything around us. According to Barthes’ theory, every ideological sign is either Denotative (literal) or Connotative (Roland Barthes and his semiotic theory, 2018). In the dictionary Connotation is an idea or feeling which a word invokes in addition to its literal or primary meaning. Signs have both a signifier, being the physical form of the sign as we perceive it through our senses and the signified or meaning that is interpreted (Roland Barthes and his semiotic theory, 2018). Neshat’s work is dense with powerful imagery and I will use this to consider the meanings of various signs within the image.

Intertextuality is the shaping of a text's (or image) meaning by another text, in this case I am concerned with the interconnection between the related works of the series of pictures Women of Allah and how the interpretation of the individual image is affected by placing it within the series. I will use this theory to reflect upon how my interpretation of the work developed from a naive first reading, through to a more informed understanding based upon how the work related to Neshat’s wider practice.

Artwork and Author

Rebellious Silence is a staged black and white photograph of a woman dressed in Chador, which is a full body cloak held closed at the neck (A Brief History of the Veil in Islam, 2020). Her hair, head and shoulders are covered but her face is not. The photograph has had Farsi text added to the woman’s face by Neshat post-production. The woman is holding a rifle, her hands are not included in the image’s composition but from the way her arms are held beneath the Chador one would suppose she is holding the butt of the rifle securely in both hands. The barrel of the rifle perfectly bisects her face and the image vertically. It appears as if her chin and nose are touching the barrel and her eyes stare at the viewer from either side. Her eyes are defined using a black, Kohl eyeliner. Behind the figure is a horizontal line and would form a cross with the gun barrel were the figure not obscuring the line.

Neshat, an Iranian, was absent from her homeland during and after the Iranian Islamic Revolution for a period of about 12 years. The Iran she found upon her return was very different to the secular Persian culture she had grown up in and had left behind in 1975, aged just 17. She was able to visit again in the early 1990’s finding a country that was now under theocratic Islamic rule and very changed. She produced this series between 1993 and 1997 because she felt compelled to make art that reflected what she had experienced in Iran and to find a way to frame her own questions regarding the foundation of the Islamic Revolution and especially how it had impacted the lives of Iranian women (Neshat,2019, pg.75).

Evaluation and analysis.

Initial Reading

Personally, I encountered much confusion and nervousness when I first came across this image, but found the image so visually arresting that I was encouraged to investigate rather than move on. On my first reading, I assumed that it had been made as a comment on the terrorist attacks of 9/11. However, I later discovered that it was produced in 1994, seven years before the World Trade Centre attacks. My experience of the image changed as I increased my knowledge of its context and the authors intended meaning, and upon reflection I can see that my initial reaction to her work was the result of cultural ideologies formed from a Westerner’s viewpoint.

Symbolism, Sign and Signified

The woman is centralised, her figure is bisected by a gun barrel, creating an image of two halves. The shape of the gun, held in such a way, seems evocative of praying hands in the Christian tradition. Although it’s unlikely that Neshat intended this reading of the work, given her Muslim background, I can’t escape the way that my own Christian background informs this interpretation. In his essay “The Death of The Author” (1976), Barthes asserts that we need not ask ourselves what the author intended in the creation of his or her work but how the viewer reads or interprets it, he focuses on the interaction of the audience, not the maker, with it. This means that the text is much more open to interpretation, much more fluid in its meaning than previously thought (Short summary: Death of the Author - Roland Barthes, 2017). I don’t adhere entirely to his ideas on this, I believe the intended reading is as valid as my own and that it will be just one of many interpretations.

Dr. Allison Young remarks in her essay that “The woman's eyes stare intensely towards the viewer from both sides of this divide”, (Young, 2015). To me, this visual divide reads as a potent signifier of the opposing cultures Shirin Neshat has experienced and her negotiation of the chasm that separates them. The one she was born to and which has, since her leaving Iran, intensified into a Theocracy (by way of a revolution) and the one she has been adopted into, in the USA. She has found herself an alien in both circumstances although arguably belonging to both, one by birth and the other by residence and choice. In Iran, she is considered as subversive and provocative, her work has offended the caliphate and she is banned from visiting, whereas in the USA, she has had to contend with prejudice and outright hostility, especially during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979, during which time American sentiments were distinctly Anti-Iranian (Neshat, 2019, p.16). The ideologies of both cultures are opposed, anti-Muslim stereotypes prevail in The West, marking Muslim women who wear the veil as a symbol of religious fundamentalism and extremism. Neshat is confronting the overriding discourse on the part of the West towards the East. She provocatively employs the Remington rifle to split the face, she sees and experiences both sides.

The gun in the photograph is a particularly powerful image. It has connotations of power, death and destruction. I find it uncomfortable and it raises many questions. Is she hiding behind its power, is she manipulated by the weapon or is she the manipulator? Is the carrying of this weapon her choice? Does she represent the power and aggressor or the defender of her culture or ideology? Or is it a comment on the power of the Theocracy? Women were called to arms during the Iran/Iraq war in the 1980’s and this was hailed by the government as being progressive and liberating for women, whilst paradoxically mandating them to observe religious piety in the wearing of the veil; their freedoms, sexuality, expression and movement are physically restricted.

Intertextuality

This photograph was taken during the second tranche (there were 3) of the Women of Allah series, the Farsi writing we see layered upon the photograph here is by the Iranian female poet, Tahereh Saffarzadeh. Farsi is the Persian word for the Persian language. Farsi and Arabic are not the same. So are the woman or women in these pictures identified or identifying as Persian, with connotations of the previous more socially permissive rule of the Shahs, rather than Iranian? Persia, as a culture, is rich in symbolism. Conversely the poem deals with the issues of martyrdom which became popular and was encouraged by the new Iranian Government during the revolution. The audience majority in the West will find that the Farsi writing covering the face is unintelligible, incomprehensible. To a Westerm audience, who the work was arguably made for, the meaning is hidden in plain sight. The text that we are unable to comprehend is reduced to decoration under our gaze. The script also serves to complete the veil figuratively, in that her face is further disguised from sight. It is a complex relationship that Iranian women have with issues such as Martyrdom, cultural identity and the wearing of the veil. Each interrogation of the image simply provides me with more questions as the layers are examined. Neshat says in a conversation with Glenn Lowry that she approaches her subjects as a sociologist would, framing the issues but never providing any answers. (Neshat, 2019, pg.75).

One should not overlook the relevance the Women of Allah series has today, post 9/11, even though the series is almost 25 years old. It has most recently been exhibited at the Broad in Los Angeles, as part of a retrospective exhibition of Shirin Neshat’s work. Neshat’s intended reading is changed by the context the work is displayed in, and by the events that happen in the intervening years given the current global events relating to fundamentalist terror attacks this century. An audience’s reading is inevitably different now than it would have been when the work was made adding another set of layers of interpretation. Are we able to make the distinction between Persian, Iranian or ‘Arab’? Can we view these images without reference to suicide bombings carried out by veiled women? I think not, which speaks to its relevance in today’s society. Recently exhibited alongside her films and more recent of works, the exhibition as a whole adds to your experience of the singular, I imagine the breadth of subject matter, the multi-media nature of her work and the monochrome nature of the offerings speak to an intensely personal experience.

The veil has come to be understood as either a symbol of Muslim women’s oppression or their resistance, constructed as dichotomous perspectives (Ladhani, 2019). In a free, liberal Western society, the veil is often read as the subjugation of women and a mechanism of control. There are many Muslim women who take exception to that perception, finding a freedom beneath the veil, free from the critical and sexual male gaze. Part of the provocation of these images is to question our ideological affinity to this discourse. The veil worn in its various forms (leaving out Christian traditions around the marriage ceremony) ‘by women appears with such constancy that it generally suffices to characterize Arab society’ (A Brief History of the Veil in Islam, 2020). In this picture we see an Arab, Muslim woman, holding a gun and staring at the viewer, it shifts the subjugated female to a politically motivated weapon, there is an undercurrent of violence and politics. The eyes seem to penetrate, and her face is adorned by incomprehensible text. I was initially nervous of this image, she seemed completely ‘other’ to me. I questioned whether it was a challenge to faith or ideology or was it a propaganda image? The way the gun is positioned is reminiscent of holding a finger to your lips in the internationally recognised sign or command for quiet, silence. Is she silenced by the gun or does the reference to the gun create the silence by fear? By intertextually using other images that speak to one another in a series she is able to more fully explore the symbolic nature of the gun. They inform one another. The weapon is conceivably passive in Rebellious Silence, whereas if you view another in the series, Faceless

FACELESS, 1994. (Shirin Neshat, MutualArt, 2020)

the subject is actively holding the gun with the viewer in its sights, her finger on the trigger and hand covered in Farsi text which is extolling the beauty of Martyrdom. The meaning of the text is still hidden from us, that in itself promotes a degree of fear, we are excluded from understanding it.

Both the gun and the poem give the woman a voice whilst cloaked in a silencing and constricting Chador.

Unveiling,1993, is one of her earlier photographs but still part of the same series, Neshat is pictured in the photograph and has written the poetry of Farrokhzad over her face. The words of this poem deal with the struggle women find in navigating the strict religious, social codes whilst recognising their sexual desires. It is a love poem, the author’s works are banned in Iran, whilst Tahereh Saffarzadeh writings about Martyrdom are applauded.

Unveiling (Christies.com, Shirin Neshat, 2012)

Here she appears naked beneath her Chador, it is a seductive and sensual image and the poetry, if we could but understand it gives voice to her desires. These images and the others belonging to the same series give a duality of message. Speaking to the differing circumstances and roles women inhabit in contemporary Iran and prodding the Wests perceptions and judgements. It is no one thing, this issue of Women of Allah, it is varied and complex and difficult to grasp and articulate. Sheliza Ladhani says in her essay Decentering the Veil, that contemporary discourse surrounding Muslim women who veil continues to be about them as opposed to from them (Ladhani, 2019). Within Iran, and amongst Iranian women are women who want to express themselves and their desires as well as those who adhere whole heartedly to the religious dictates. Neshat delivers both these women and others to our notice in her series. She also explores her feelings of separateness and exile from her home, family and culture. Ed Schad says in ‘I will Greet the Sun Again’, the catalogue that was produced for the exhibition at The Broad, that Neshat’s photos are beautiful articulations of empathy and identification, saturated in a visual language learned in New York and applied to an examination of contemporary Iran. These photos echo the voices of women whose freedom balances precariously on the fault line of an Iran caught between modernizing and conservative forces (Neshat, 2019, pg15).

Conclusion

Neshat recalls that her first exhibition of the Women of Allah series was written about by a New York Times critic. He had complained about her work as being too confusing, wondering where she was coming from. He asked was it a case of radical chic or a way to romanticise violence? (Neshat, 2019, pg. 76). He may have a point. The inclusion of the gun in some of her works in this series is provoking and shocking, it is a tool of destruction and violence. When seen in reference to an Islamic veil and in the hands of a woman our minds travel to radicalisation and fundamentalism. But there is an irony and conflict here too, given the US’s much debated and firmly held right to bear arms. Neshat as a naturalised American has the right to bear arms, but as a Muslim, she could be said to be one of the reasons that the US want to bear arms – for protection. The inclusion of the rifle could be speaking to this dichotomy.

As we have seen Rebellious Silence is a deeply layered and challenging work, but its impact lies in its ambiguity, complexity and difficulty. By confronting the viewer with a dense set of signs and symbols, Neshat forces us to think more deeply and to question her intentions. Nothing can be taken for granted and nothing is made easy. It’s through this challenge that the photograph and wider series Women of Allah prompts debate and discussion, which is ultimately how change and awareness come about. The photographs openly wear paradoxes and what seem like contradictory points of view, says Ed Schad (Neshat, 2019, pg. 15). In agreeing or disagreeing with the artists intended meaning and debating its efficacy, we bring ourselves into the experience and thus have a unique reaction and viewpoint from which to decipher the work. Perhaps it is because of these many layers of meaning that the work is still so relevant today.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Speaking for Towards Listening to Iranian Protesters

At least two hundred and eight Iranians have been killed due to protests that began on November 15, 2019 (Amnesty 2019). The protests emerged initially because of the backlash towards the abrupt increase in fuel prices. However, as a result of the Iranian government’s deadly crackdown on protesters and the prohibition of the internet, the number of protestors increased. Moreover, diverse concerns exceeding gas prices reached the forefront such as poverty, unemployment, women’s issues and more. The media has been a tremendously beneficial tool in representing the concerns of the Iranian protesters, notably, western news outlets and social media coverage. The representation of these protests has not only been extensive but also accurate in representing the true concerns of Iranian people, compared to the news media coverage of the 1979 Iranian women's movement. For this reason, I believe that the contemporary representation of Iranian protests through the various outlets that exist as well as social media has been extremely empowering, rather than the preceding approaches of representation that were borderline demeaning. I will begin this blog post by first explaining representation methods that are problematic by using examples of the 1979 Iranian women’s movement. Next, I will compare this to the recent coverage of the 2019 Iranian protests and provide context towards why this form of representation is empowering. Lastly, I will provide a concluding statement on how we can move forward with solidarity in mind.

The 1979 Iranian women’s movement marked a period in which western media presumed that Iranian women were emerging “to their senses” and standing up against Islam and its “oppression” towards women by fighting against the new Islamic leader (Chan-Malik 119). Sylvia Chan-Malik explains how media coverage at the time failed considerably in accurately resonating with the concerns of a large majority of the population within the protests. For instance, media coverage spoke for Iranian women by stating they were fighting for the “same things as women from the west” (119) such as equal civil rights, abortion, child-care. Although in actuality, a larger majority of protestors continued to be rallying against the same issues they had been plagued with since before the Iranian revolution (123). The issue with the representation in 1979 is through the ways it was deeply orientalist and propagated information that was inaccurate towards a large number of Iranians at the time. It framed “a new binary of “Islam” versus “feminism” in which two concepts became diametrically opposed” (123) and allowed for the framing of Iranian women as “poor Muslims” who were in dire need of saving (117). News outlets completely neglected several issues Iranian protesters were rightfully concerned with such as fears of democratic liberties being stripped away by the hands of a new leader that was presumed to save the population from its previous leader. Instead, the U.S media coverage used the struggles of protestors as a means to express Islam as inherently anti-feminist and ignored many others. An issue with representation at the time also contained was the lack of the vast variety of news coverage we have today.

In recent times we have witnessed the emergence of copious amounts of new media outlets. Furthermore, the addition of the easily accessible internet has allowed for obtaining unbiased and reliable news coverage much more attainable. In 1979, the coverage was mainly paper print and more scarce compared to the endless coverage we have today through many different sources. In the particular case of the recent protests, much of the coverage has been obtained first hand through the lenses of the phones of brave protesters. This is hugely different than the 1979 protests as social media outlets such as Twitter, Instagram, as well as messaging software did not exist. In this form of information, we can visually and audibly listen to the demands of the Iranian people in real-time as the events are transpiring. The form of media representation in this incident was also beneficial in the ways that it resisted the commands of the government. This is due to their complete internet shut down for five consecutive days. When news broke that the government shut down the internet in Iran, the remainder of the world took action and began following the events transpiring. Many people, especially from the Iranian diaspora including myself, shared solidarity with the brave individuals who risked their lives protesting by changing their photo to an image of the map of Iran over a red background.

Image 1: https://www.instagram.com/p/B5DnO6BHfFN/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Many also made the issues a priority as they posted and shared videos from inside Iran. Some of these videos contain extremely graphic imagery showing militarized police brutally beating, shooting, and even killing peaceful protestors. Although the internet was shut down, a few videos were able to surface and especially several videos were shared once the internet was given back. Yet, with the government attempts to shut the eyes of the world on Iran’s corruption towards its citizens, it allowed for further conversations and numerous hashtag movements such as #FreeIran and #FreeInternet4Iran to surface. Furthermore, the conversation was flowing as numerous celebrities and political figures such as Bernie Sanders spoke regarding the issues.

Image 2: https://twitter.com/sensanders/status/1196969926441029632?lang=en

Covering this information is very important in this case because regardless of the particular reason why individual protesters may be flooding the streets, it is crucial that the world recognizes the human rights violations that are happening in a country where peaceful assemblies are so condemned that it requires the use of lethal brutality. The use of first-hand eyewitness testimony is extremely powerful as it allows for the world to listen in on the demands of the people rather than reading someone else's impression on the protests from a journalist who is not an active citizen of the country, much like in 1979. Although awareness alone is not significant enough to save Iranian people from the corrupt government they are under, it is certainly helpful. It is also very important that the world noticed the realities of what is transpiring because it is a form of protests against the government that does not want the world to see what they have been doing to their own people. Iran has a deep history of protesting and demonstrations so much so that the revolution began because of citizens voicing themselves, which gives me optimism that Iran could certainly face another form of revolution in the near future.

Image 3: https://www.instagram.com/p/B5pKkxgoaMD/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Works Cited

“@iranprotest2019 On Instagram: "#Freeiran #Iran #freeinternet4iran.’” Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/B5DnO6BHfFN/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Chan-Malik, Sylvia. “Chadors, Feminists, Terror.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 637, no. 1, 25 Sept. 2011, pp. 112–140., doi:10.1177/0002716211409011.

“Iran Protest Death Toll Rises to 208 People since 15 November.” Iran: Death Toll from Bloody Crackdown on Protests Rises to 208 | Amnesty International, Amnesty International, 2 Dec. 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/12/iran-death-toll-from-bloody-crackdown-on-protests-rises-to-208/.

Neyestani, Mana. “The Waves of Blood .” Instagram, 4 Dec. 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/B5pKkxgoaMD/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link.

Sanders, Bernie. “All People Have the Right to Protest for a Better Future. I Call on the Iranian Government to End the Internet Blackout and Stop Violence against Demonstrators. Https://T.co/mB45vFDNy5.” Twitter, Twitter, 20 Nov. 2019, https://twitter.com/sensanders/status/1196969926441029632?lang=en.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Iran’s Jewish community is the largest in the Mideast outside Israel—and feels safe and respected

Kim Hjelmgaard, USA TODAY, Aug. 29, 2018

TEHRAN, Iran--In a large room off a courtyard decorated in places with Islamic calligraphy and patterned tiles featuring intricate geometric shapes and patterns, men wearing tunics, cloaks and sandals recite morning prayers.

At the back of the room, three women sit together on a bench, hunched over ancient texts. Scarves cover their hair, as required by Iran’s religious law. Birdsong floats into the cavernous space as the incantations grow louder and more insistent.

This is a synagogue. In Iran.

In a nation that has called for Israel to be wiped off the face of the Earth, the Iranian government allows thousands of Jews to worship in peace and continue their association with the country founded more than 2,500 years ago.

“We have all the facilities we need for our rituals, and we can say our prayers very freely. We never have any problems. I can even tell you that, in many cases, we are more respected than Muslims,” said Nejat Golshirazi, 60, rabbi of the synagogue USA TODAY visited one morning last month. “You saw for yourself we don’t even have any security guards here.”

At its peak in the decades before Iran’s Islamic Revolution in 1979, 100,000 to 150,000 Jews lived here, according to the Tehran Jewish Committee, a group that lobbies for the interests of Iranian Jews. In the months following the fall of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, Iran’s second and last monarch, many fled for Israel and the United States.

It was a dispersion precipitated in part by the execution of Habib Elghanian, who was then one of Iran’s leading Jewish businessmen and philanthropists. Elghanian also headed the Tehran Jewish Committee and had ties to the deposed shah. He was killed by firing squad after being accused by Iran’s Islamic revolutionaries of spying and fundraising for Israel.

Today, 12,000 to 15,000 Jews remain in Iran, according to the committee.

It’s a small minority in a nation of 80 million people. But consider: Iran is home to the Middle East’s largest Jewish population outside Israel.

And, according to Golshirazi and other senior members of Iran’s Jewish community, they mostly enjoy good relations with Iran’s hard-line, theocratic government despite perceptions abroad that Iran’s Islamic rulers might subject them to harsh treatment.

“The Muslim majority in Iran has accepted us,” said Homayoun Sameyah Najafabadi, 53, who holds the role once held by Elghanian, chairman of the Tehran Jewish Committee.

“We are respected and trusted for our expertise and fair dealings in business, and we never feel threatened,” he said. “Many years ago, before the royal regime of Pahlavi, by contrast, if it was raining in Iran, Jews were not allowed to go outside of their houses because it was believed that if a non-Muslim got wet and touched a Muslim it would make them dirty.”

Najafabadi said it may be difficult for Jews and others outside the country suspicious of Iran’s treatment of religious minorities or its views on Israel to accept, but after the execution of Elghanian, Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s first supreme leader, deliberately sought to improve relations between Jews and Muslims in the country for the nation’s long-term stability.

He added that Jews, who have been in Iran since about the eighth century B.C., used to be scattered all over the country but are now largely concentrated in Tehran and other big cities such as Isfahan and Shiraz. In all, he said, Iran is home to about 35 synagogues.

Najafabadi said most Jews in Iran are shopkeepers, although he said others work as doctors, engineers and in other highly skilled professions.

There are no Jews, however, in senior government positions. There’s only one Jewish representative in the country’s 290-member Parliament. His name is Siamak Moreh Sedgh.

Sedgh, 53, said one of the reasons Jews in Iran are able to live peacefully is that they consider themselves Iranians first--and Jews second.

“We’re not an entity outside of the Iranian nation. We are part of it. Our past and our future. I may pray in Hebrew, but I can only think in Persian (Farsi, Iran’s language),” said Sedgh, who is also a surgeon at a hospital in central Tehran, where USA TODAY spoke with him.

Crucially, that affinity extends to the question of Israel.

“I don’t think Israel is a Jewish state because not everyone in Israel lives according to the teachings of the Torah. This is what Jews in Iran believe,” Sedgh insisted.

He acknowledged that it was somewhat ironic that Iran, arguably the biggest foe of Israel, was also the “biggest friend of the Jewish people.”

Sounding more Iranian than Jewish, Sedgh said he disagreed with President Donald Trump’s decision this year to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv because “Trump can’t just change a capital city that according to international law and the United Nations is an occupied city.”

“Trump is a coward who has lost his humanity and forgotten about spirituality. He wants to destroy large parts of the world only for the benefit of a small group of capitalists,” Sedgh said.

On Tehran’s bustling streets, Jews are not very visible, partly because there are so few of them. USA TODAY did, however, spot a few men wearing kippahs as they hurried off to work in the morning. They did not appear to attract any second glances from Iranian men in business suits, others in traditional Muslim dress or women sporting hijabs and chadors.

Other minority groups in Iran include Arabs, Armenians, Baloch people (who live near Pakistan, in Iran’s southeast), Christians and Kurds. Open Doors USA, an organization that tracks persecuted Christians worldwide, estimates there could be as many as 800,000 Christians secretly living in Iran. It says Christians in Iran are routinely subject to imprisonment, harassment and physical abuse for seeking to convert Muslims. USA TODAY did not encounter any Christians in Iran.

Outside the Yousef Abad Synagogue, the entrance via the courtyard was unprotected, and it was easy to walk straight in. That’s unheard-of for Jews in Europe, where Jewish schools, institutions and places of worship receive extra security amid a spate of attacks.

“What you see there (for Iran’s Jews) is a very vibrant community,” said Lior Sternfeld, a Middle East historian who in November will publish a book on modern Jewish life in Iran. “A community that faces problems--but it’s Iran, so problems are a given.”

Still, rights groups and experts believe Jews in Iran do face discrimination. Najafabadi, the committee chief, conceded that in some instances, Iranian Jews have had trouble getting access to the best schools with their Muslim peers.

Then there’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran’s former president, who drew international attention when he repeatedly denied the Holocaust in which 6 million Jews were murdered.

Meir Javedanfar, an Iranian Jew, says life has improved for Jews under Iranian President Hassan Rouhani. Javedanfar left the country for Israel in 1987 as a teenager and now teaches classes on Iranian politics at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, north of Tel Aviv.

Javedanfar said, for example, that Jewish children in Iran are no longer required to attend school on the Sabbath, the traditional day of rest and religious observance among Jews that falls on a Saturday but is a regular workday in Iran.

“At the same time, the regime continues to hold Holocaust cartoon contests that are pretty anti-Semitic,” he noted, referring to a provocative annual exhibition in Iran that mocks Jewish suffering while claiming to challenge Western ideas about free speech and Holocaust taboos.

He quickly pointed out: “The regime is not too concerned about its Jews as long as they don’t become involved in politics and don’t say anything positive about Israel.”

Golshirazi the rabbi, Najafabadi of the committee and Sedgh the parliamentarian all stressed they were speaking truthfully and not trying to distort their views of life in Iran for Jews out of fear of government persecution. They also said Jews in Iran often enjoy extra social freedoms that Muslims do not, such as the ability to consume alcohol in a private setting.

The few Jews in Iran are unlikely to leave.

In 2007, the Tehran Jewish Committee rejected an offer by Israel’s government to pay each family of remaining Jews in Iran up to $60,000 to help them leave the country.

“I can tell, you are thinking I am afraid,” Golshirazi said when USA TODAY pressed him on that point. “But I have been many places visiting Jewish communities. Iran is the best for us.”

1 note

·

View note

Quote

“Lasciate gli uomini liberi di importunarci”, dicono le firmatarie, quegli uomini che in questi mesi “sono stati puniti sommariamente, costretti alle dimissioni solo per avere (...) parlato di argomenti intimi durante cene di lavoro (...) a donne per cui l’attrazione non era reciproca”.

Un attacco che stride con la vulgata dominante del #MeToo, che sembra ormai trasformare la seduzione in molestia, gli approcci galanti in paura di essere tacciati di machismo.

La presa di posizione di Deneuve ha fatto scatenare l’ira - ça va sans dire - di Asia Argento. (...)

Al di là delle critiche, feroci e prevedibili, in molte hanno deciso di parlare a sostegno dell’opinione espressa dalla lettera della Deneuve, ringraziandola per avere rotto il silenzio di tutte coloro che non si sentono molestate ma, anzi, lusingate dalla seduzione, dalla galanteria degli uomini che vogliono provarci. (...)

come dichiarano le firmatarie dell’appello, il femminismo non è odiare gli uomini e la sessualità, né istituire un tribunale che somigli a un macello al quale “inviare i maiali” (...). Per difendere la libertà sessuale è essenziale non confondere il porco e l'orco, essere liberi “di sedurre e importunare".

https://www.ilfoglio.it/societa/2018/01/10/news/deneuve-e-le-altre-ecco-la-fronda-anti-metoo-per-la-liberta-di-essere-importunate-172396/

Già: Le Asie sono contro la libertà sessuale, sono perfettamente funzionali ai disegni chador degli islamici e dei vecchi tartufi.

JE SUIS CATHERINE DENEUVE

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The media’s Representation of Social Activism by Iranian Women

By Elahe Nezhadhossein

The Situation of Women in Iran

Political and religious events in Iran, especially since 1925, have had an impact on Iranian women’s social and economic activities. This includes Reza Khan and Pahlavi’s dynasty and their anti-hijab policies; and after the 1979 Islamic Revolution the compulsory hijab and oppressive laws against women. But what is poorly understood by most people in the West is that the major problems related to gender inequality come from an undemocratic political system rather than the Shi’a interpretation of Islam. Political systems can support patriarchy through the legal system, for example by supporting men through family laws (see, for example, Sylvia Walby).

Despite the oppression that occurs in fundamentalist political systems, women delaying marriage and completing high levels of education challenge patriarchy and fundamentalism (Homa Hoodfar & Fatemeh Sadeghi). Not only did religious laws after the Islamic Revolution not have a negative influence on the economic situations of women, their financial conditions actually improved much more quickly after the Revolution.

Some feminist activists and scholars in the West as well as Western journalists have an inaccurate impression of the oppression and the veil wearing of Middle Eastern and Muslim women in general. Their misconceptions are based in part on ignorance, racism, and colonialism (Chandra Talpade Mohanty). In her studies of Iranian and other Middle Eastern women’s histories of wearing veils and their social and economic activities, Homa Hoodfar asserts that Western images of oppression are far from the real situation of these women. Part of the reason why inaccurate and stereotyped images of contemporary women in Muslim countries are common in the West is because the present Iranian government tends to emphasize the more traditional pictures of women and does not portray their active roles in the economic, social, and political arenas of society. At the same time Western commercial mass media tend to focus on images of the more oppressed women because the main news values are novelty, negativity, and deviance.

The irony of governments subsidizing organizations fostering minority empowerment is that it can lead to bureaucratization and economic dependence on the government. This can divert minority movements and institutions (including the women’s movement) from their radical demands (Roxana Ng). In a country like Iran, which has an ideological government, some women’s institutions poorly reflect the women’s movement. The official institutions for women in Iran support the government’s ideology and encourage the domestic role of women because they receive funding from the government (Valentine Moghadam). This is another reason why representations of Iranian women in that nation’s national media do not aptly represent the activities and situations of its female citizens.

Comparing employment rates is one way of measuring gender inequality. Rates increased much more quickly for Iranian women in the 1990s than they did during the 1960s and 70s when a pro-Western secular regime was in power (Roksana Bahramitash). This sharp increase in women’s employment challenges the view that religion is responsible for the economic status of women in Muslim countries. Even though women were forced to wear the hijab after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, they have continued to be politically active (Faegheh Shirazi) and active in the economy, including education and business. Behind the hijabs that cover today’s women, there are great minds which are hard at work and committed to transforming their country.

Social Movements, Media, and Women

After the Iranian Presidential elections of June 2009, the Green Movement sprang up, protesting the election results that awarded Ahmadinejad a second Presidential term. In response to the widespread positive reaction to this movement, the government expelled in less than one week all international journalists and imprisoned many Iranian journalists and activists. Consequently, fewer free journalists were able to cover the events occurring in the streets in Tehran and other cities.

Following this crackdown, ordinary citizens began to fill the gap in documenting the Green Movement. They posted the images and videos they took with their hand cams and cell phones on websites such as YouTube and Facebook. These images taken by ordinary citizens were the only record that documented the presence and activism of women.

This movement was named the Green Movement because the reformist Presidential candidate Mousavi, who became the leader of the movement after the elections, had chosen the color green as a symbol for his party. After the election his supporters kept using green to show publicly that they had voted for him. The main demand of the activists was for democracy and the rejection of the thirty-year-old theocratic authoritarian regime. Iranian women played a huge role in the social uprising after the 2009 election. They believed the democratic movement would successfully help them gain their rights and freedom.

During the protests of the Green Movement, many women were injured and killed by government forces. The brutality of the police forces left many women with scarred faces, which made it easy to identify them later. But this did not stop them from continuing their protests in the streets. Such bravery also reflects their physically active resistance and the limits of their oppression. Most of the women participating in the Green Movement did not completely cover their hair, resisting the government’s laws aimed at controlling women’s bodies and movement in public. These women have been labeled “bad hijabs” by the regime. Some women did cover their heads and faces but because they did not want the government to recognize them.

Most of the women in the Green Movement were not wearing the roosari properly, as is required by the government’s unwritten rules. This shows their resistance against discriminatory laws. At the same time, some women fully covered their hair or were wearing the chador, though there were not many in comparison to the other women called “bad hijabs.” This shows that even religious women (or women who prefer to cover their hair) were also asking for equal rights for all women and were fighting the government’s discrimination and gender inequality. Women’s participation in the Green Movement was as valuable as that of men.

After facing increased oppression, women moved their spheres of activity from NGOs and the public to cyberspace, which was safer and more accessible (Mahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh). Comparing women’s participation in social movements in Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia shows that women were actively – though peacefully – fighting and changing the oppressive system against them (Elham Gheytanchi & Valentine Moghadam).

Social movements are dependent on communication tools including person-to-person conversations, rumors, the press, the internet, etc. The tools of mass media help movements to organize their activities because they allow participants to share their ideas. New media and the Internet in particular help social movements communicate independently from traditional government control.

In all societies mass media are under the surveillance of political elites. At the same time activists are likely to be critics of the prevailing power structures. Women’s movements, for instance, have often critiqued media representations of their activities because journalists perpetuate stereotypes about women (Jenn Goddu). But connections between mass media and social movements are multifaceted and dynamic (Suzanne Staggenborg). Social movements result in a wide range of effects, from changing a political regime or laws and policies to invisible changes which occur in people’s minds. Changing policies, laws, political and economic structures may be the main goals of social movements, but over time, their most impressive achievements are likely to be changing people’s perceptions and priorities (Mark CJ Stoddart).