#anti-colonial asian resistance

Text

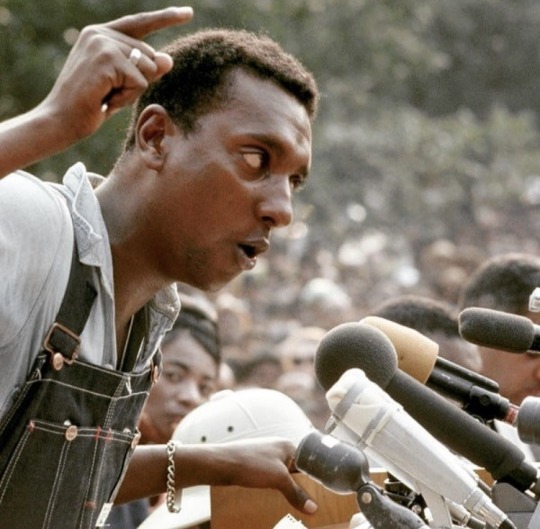

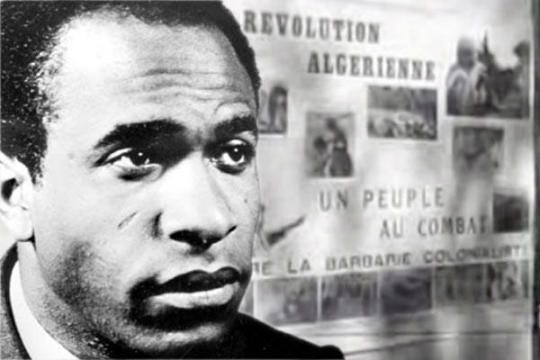

Malcolm...Hampton...Kwame...Fanon...these men remain my idols. The calibre they honed made them stand in a league no man of intelligence or power could ever come close to again after them. They stand iconic next to Jesus. True heroes for living. Sent by God to uplift and uproot millions of lives from mental enslavement. Freeing the mind to escape physical captivity from the Devil. All of them speaking poetry to my soul. Each one inside a godliness they taught *we* own. I worship their existence for the worth they give. & Praise them for the fight to decolonize earth. May the soul of what they stood for, live forever. Viva! Mabuhay!

#PowerToThePeople ✊🏽✊🏽✊🏽✊🏿✊🏿✊🏿🪖🎓

⚜️

#fred hampton#malcom x#kwame ture#frantz fanon#brilliant minds#revolutionaries#wretched of the earth#black panthers#brown berets#yellow peril#down with imperialism#down with colonialism#decolonize#black liberation#for the culture#anti-colonial asian resistance#black lives matter#global south

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just in case, some might enjoy. Had to organize some notes.

These are just some of the newer texts that had been promoted in the past few years at the online home of the American Association of Geographers. At: [https://www.aag.org/new-books-for-geographers/]

Tried to narrow down selections to focus on critical/radical geography; Indigenous, Black, anticolonial, oceanic/archipelagic, carceral, abolition, Latin American geographies; futures and place-making; colonial and imperial imaginaries; emotional ecologies and environmental perception; confinement, escape, mobility; housing/homelessness; literary and musical ecologies.

---

New stuff, early 2024:

A Caribbean Poetics of Spirit (Hannah Regis, University of the West Indies Press, 2024)

Constructing Worlds Otherwise: Societies in Movement and Anticolonial Paths in Latin America (Raúl Zibechi and translator George Ygarza Quispe, AK Press, 2024)

Fluid Geographies: Water, Science, and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, University of Chicago Press, 2024)

Hydrofeminist Thinking With Oceans: Political and Scholarly Possibilities (Tarara Shefer, Vivienne Bozalek, and Nike Romano, Routledge, 2024)

Making the Literary-Geographical World of Sherlock Holmes: The Game Is Afoot (David McLaughlin, University of Chicago Press, 2025)

Mapping Middle-earth: Environmental and Political Narratives in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Cartographies (Anahit Behrooz, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024)

Midlife Geographies: Changing Lifecourses across Generations, Spaces and Time (Aija Lulle, Bristol University Press, 2024)

Society Despite the State: Reimagining Geographies of Order (Anthony Ince and Geronimo Barrera de la Torre, Pluto Press, 2024)

---

New stuff, 2023:

The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Camilla Hawthorne and Jovan Scott Lewis, Duke University Press, 2023)

Activist Feminist Geographies (Edited by Kate Boyer, Latoya Eaves and Jennifer Fluri, Bristol University Press, 2023)

The Silences of Dispossession: Agrarian Change and Indigenous Politics in Argentina (Mercedes Biocca, Pluto Press, 2023)

The Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Dueterte (Vicente L. Rafael, Duke University Press, 2022)

Ottoman Passports: Security and Geographic Mobility, 1876-1908 (İlkay Yılmaz, Syracuse University Press, 2023)

The Practice of Collective Escape (Helen Traill, Bristol University Press, 2023)

Maps of Sorrow: Migration and Music in the Construction of Precolonial AfroAsia (Sumangala Damodaran and Ari Sitas, Columbia University Press, 2023)

---

New stuff, late 2022:

B.H. Roberts, Moral Geography, and the Making of a Modern Racist (Clyde R. Forsberg, Jr.and Phillip Gordon Mackintosh, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022)

Environing Empire: Nature, Infrastructure and the Making of German Southwest Africa (Martin Kalb, Berghahn Books, 2022)

Sentient Ecologies: Xenophobic Imaginaries of Landscape (Edited by Alexandra Coțofană and Hikmet Kuran, Berghahn Books 2022)

Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884–1905 (Matthew Unangst, University of Toronto Press, 2022)

The Geographies of African American Short Fiction (Kenton Rambsy, University of Mississippi Press, 2022)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski, University of Chicago Press, 2022)

Punishing Places: The Geography of Mass Imprisonment (Jessica T. Simes, University of California Press, 2021)

---

New stuff, early 2022:

Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-fatness as Anti-Blackness (Da’Shaun Harrison, 2021)

Coercive Geographies: Historicizing Mobility, Labor and Confinement (Edited by Johan Heinsen, Martin Bak Jørgensen, and Martin Ottovay Jørgensen, Haymarket Books, 2021)

Confederate Exodus: Social and Environmental Forces in the Migration of U.S. Southerners to Brazil (Alan Marcus, University of Nebraska Press, 2021)

Decolonial Feminisms, Power and Place (Palgrave, 2021)

Krakow: An Ecobiography (Edited by Adam Izdebski & Rafał Szmytka, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021)

Open Hand, Closed Fist: Practices of Undocumented Organizing in a Hostile State (Kathryn Abrams, University of California Press, 2022)

Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

---

New stuff, 2020 and 2021:

Mapping the Amazon: Literary Geography after the Rubber Boom (Amanda Smith, Liverpool University Press, 2021)

Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by María del Pilar Blanco and Joanna Page, 2020)

Reconstructing public housing: Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives (Matt Thompson, University of Liverpool Press, 2020)

The (Un)governable City: Productive Failure in the Making of Colonial Delhi, 1858–1911 (Raghav Kishore, 2020)

Multispecies Households in the Saian Mountains: Ecology at the Russia-Mongolia Border (Edited by Alex Oehler and Anna Varfolomeeva, 2020)

Urban Mountain Beings: History, Indigeneity, and Geographies of Time in Quito, Ecuador (Kathleen S. Fine-Dare, 2019)

City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856 (Marcus P. Nevius, University of Georgia Press, 2020)

#abolition#ecology#multispecies#landscape#tidalectics#indigenous#ecologies#archipelagic thinking#opacity and fugitivity#geographic imaginaries#caribbean#carceral geography#intimacies of four continents

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

This notebook, “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” gathers writers, translators, filmmakers, artists, historians, and critics to revisit a significant period of Southeast Asian history—the Malayan Emergency. The Emergency, which took place from 1948 to 1960, was a war between British colonial forces and communist fighters mostly based in the Malayan rainforest. The history and analysis of this war—including British initiatives that forcibly resettled half a million people, primarily ethnic Chinese Malayans, into heavily surveilled New Villages, and deported thousands to China—is fragmented and complex. Not only is the history split across different languages such as Malay, Chinese, and English, it is often eclipsed by the British colonial depiction of the fight as an “emergency” incited by communist “terrorists,” instead of an anti-colonial struggle.

The writers featured in “The Rainforest Speaks,” edited by Min Ke (民客), attempt to recover this elusive past and address those not well-represented in the historical record, including the communist guerrilla fighters, rural Chinese Malayans, Indian plantation workers, the indigenous Orang Asli people, and the rainforest itself. The contributors, who Min Ke notes are “all a generation or more removed from the events of the Emergency,” contend with these gaps through original translated stories, essays, criticism, and art. The resulting collection of work resists a singular narrative about the Emergency and instead traces the many perspectives of those involved. “The urge to return to scenes of the Emergency, to look beyond the colonial archive, is not only a painstaking task of recording imperial wrongs that persist in the present,” writes Min Ke in the editor’s note to the notebook. “It is, above all, an imaginative task, one that cannot be captured by an individual or group.”

Each piece in “The Rainforest Speaks” features art by Sim Chi Yin.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

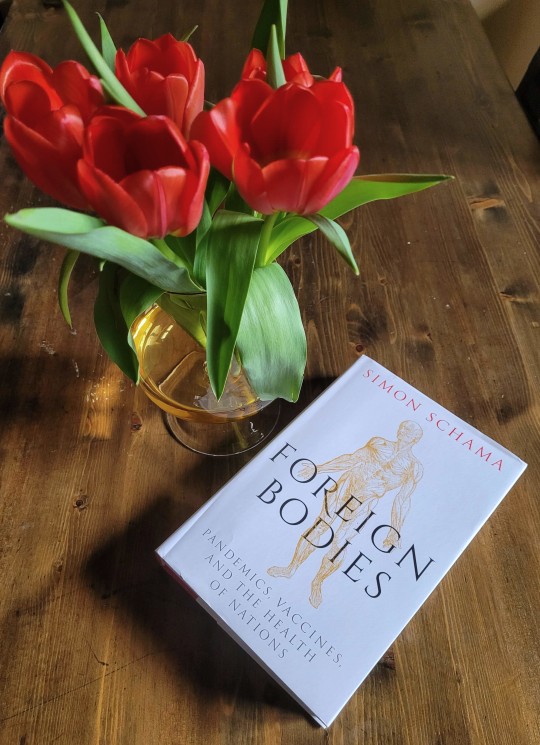

Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations by Simon Schama 3.5/5 stars

bear with me lads, this is an Extremely special interest book review

Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations is a generally good book marred by a few incidents of absolutely deranged framing. I liked a lot about it, but it lacks focus. While it is an in depth look at an interesting subject for a popular audience, it doesn’t always hold up on an academic level. Ultimately, for me it worked better as a companion read to Seth Dickinson’s The Masquerade, which also deals with colonial medicine and hygiene, but in a fictional setting. Foreign Bodies covers a lot but it doesn’t stand up on its own.

The elephant in the room was, for me, that Simon Schama is an art historian, not a historian of science or medicine, and you can tell.

Or, well, I could tell, because I am a historian of science; I have two very expensive degrees about it. That’s why I have so much to say about the minor things that are wrong with this book.

First, the good. Foreign Bodies is a fun and eclectic look at the unfortunately not widely popularized niche of medical history: colonial medicine. I would actually highly recommend it as an anti-colonial read to flesh out one’s understanding of British occupation of India and China. The exploration of the racialized and colonial politics of hygiene and cleanliness — and how the principles of sanitation formed a cornerstone of the ideology of empire — is perhaps this book’s best contribution. As I mentioned above, I read this book directly after The Masquerade series. The series uses a fictional setting to explore the ethics of resistance to colonization. The most complete resistance to colonization includes refusing to adopt colonial practises of sanitation and medicine which do save lives. Is this a necessary sacrifice? Medicine is the poisoned fruit of empire; access to it is used to as both carrot and stick to ensure colonial obedience. The Masquerade is very thoroughly researched and incorporates a dizzying array of historical influences, and Foreign Bodies serves as an exploration of many of them. It contextualizes the fictional constructions in our real history.

I also, personally, loved the verbose literary style. This book is way way more complicated than it needs to be, but I found it fun and funny. My favourite example was the use of ‘conurbation;, rather than ‘city’ or even ‘metropolis’. What the fuck. If you prefer clarity and directness, you might not enjoy wading through this book’s extremely languorous prose, but for me it had a certain academia-camp charm. And I can appreciate the compulsion to explain and clarify that leads to long-windedness like this. I feel #seen.

What I appreciated less were the weird quirks of framing. Foreign Bodies is pretty aggressively anti-colonial. I’ve read a lot of books where the author is reluctant to explicitly ascribe responsibility for the cruel and unusual behaviours of colonial regimes — all of which were ultimately perpetrated by individual human beings — and this is not one of them. But it exclusively uses the 19th century European terms to refer to Asian locations. That was the detail that tipped me off that this was Schama’s first foray into the field. Unless the context is extremely specific to the 19th century geography or regime, I’m used to seeing Myanmar, not Burma. The 19th century names are technically not incorrect, it’s just not the sort of thing I’d expect to see in an academic work.

The other thing I wouldn’t expect to see, and to my mind the far more egregious error, is the continuous framing of inoculation as new and scientific while previous regimes of sanitization were superstitious and religious. Actual historians of science simply do not think like this.

I think it’s absolutely accurate to say that the Europeans, and especially the British, approached protocols of carbolic sanitization with a fanatical zeal, but to suggest that this was the religion of carbolic to the science of inoculation is misguided and ultimately distracts from the book’s more interesting questions. First, let’s quickly dispense with the idea that science and religion are two opposite poles of knowledge, as diametrically opposed as black and white. It’s especially out of place in a book that is otherwise attempting empathy towards non-western traditions of medicine, culture, and belief. Science is just another belief system grounded on very specific verification procedures (as opposed to faith, or criticism of certain texts, etc). The sooner we understand that science is a system of belief rather than a privileged access to The Truth, the better we will be at handling the times that science is wrong.

Because science is wrong all the time. Our understanding of our reality is is constantly changing as we refine pre-existing theories and discover new ones. Carbolic was exactly such a case. Fifty years previous, sanitization was the scientific doctrine bravely fighting the superstition of doctor’s honour and the religion of laudable pus.

I found it especially deranged that Schama frames inoculation as part of the vanguard science of bacteriology in opposition to sterilization. Sterilization is grounded in bacteriology just as much as inoculation, if not more (the evidence for the effectiveness of inoculation was exclusively statistical in this period, not microbial). Disease is caused by germs. To treat the disease, use carbolic to kill the germs. The germ are invisible and everywhere, so carbolic your shrivelled British heart out. This is mixed, of course, with the colonizers’ fundamental lack of respect for the personhood of the colonized, and you get the so-called religion of carbolic. It’s just out-dated science strained through a conservative and slow to adapt colonial bureaucracy.

This framing of inoculation and sanitization as two opposite poles of scientificness obfuscates the fact that inoculation was was just as much a part of western science, the western culture and technologies that were steam-rolling their way over Ayurvedic and Chinese medical systems. Does it make it better than this fruit of empire fulfils its promise? Schama isn’t interested in asking, and treats inoculation as unambiguously good, free from the colonial baggage of the rest of medicine. I get that the exploration of this question would be limited by the extreme paucity of non-European sources, but the execution here was still disappointing.

Ultimately, while Foreign Bodies is informative and interesting, it works best as a companion read because it doesn’t really come together by itself. It addresses the obvious, but fails to move any deeper. I have a distinct memory of being struck by the realization, a third of the way through the book, that I didn’t know what it was actually about. Schama draws a connection between viruses and bacteria as foreign bodies causing disease (this is the detail that separates germ theory from humoural theory), to suspicion of inoculation being grounded in fear of injection with foreign bodies, to key figures in the history of inoculation as foreign bodies both within the Asian countries where they worked and within the Western European empires that employed them. It’s a tantalizing idea, but Schama never explains what this connection is (beyond a literary image) or what it might mean. There is meat on that bone. What is the meaning of native and foreign in medicine? How does it interact with our ideas of sanitariness and cleanliness? How can we use this information to decolonize medicine and hygiene in the future? Foreign Bodies pivots so hard from wrapping up its many historical tangents to bemoaning COVID vaccine denialism that it never has time to address them. (This is putting it charitably; put uncharitably, one might suspect that this sort of thing never occurred to Schama at all).

I think the book is an admirable effort for a non-historian of science. It hits the mark way more than it misses. I just did find myself wishing that it had a little more of an understanding of the history and philosophy of science as a field. We’ve been over this sort of thing, but if that work never gets picked up but outsiders, we’ll keep spinning in circles.

#bookblr#book review#read in 2024#nonfiction#medical history#book blogging#foreign bodies#simon schama

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Marxist Education Project invites you! The course is online, and is $0-80. Classes begin September 18th.

Join us to read selections from the best of Chinese and Chinese-American science fiction. Over the last ten years, authors have reached English-speaking audiences with exciting and award-winning new literature using the metaphors and methods of speculative and visionary writing.

The new wave of younger Chinese science fiction writers often brings exciting explorations of political and social themes. Alongside daring new scientific imaginations, our selections this fall feature issues of anti-Asian violence and racism, colonialism, then and now, and the cruelties of global capitalism, often resulting in resistance to oppression. Our selections truly merit the new tag of “visionary fiction.”

Our reading group includes people steeped in the speculative fiction tradition as well as new readers exploring themes with us for the first time. The tilt of global economics, scientific research, and politics Eastward makes this fall’s theme timely.

Our list, still in formation, tentatively includes:

Vagabonds by Hao Jinfang, as well as her Hugo award-winning story, “Folding Beijing”

Selections from short story collections written, translated or edited by Ken Liu: Hidden Planets, Broken Planets, and The Hidden Girl

Babel, by RF Kuang

Our Missing Children, by Celeste Ng

Severance, by Ling Ma

We plan to experiment with a hybrid format. We will meet monthly for a longer, in-depth discussion as we finish a book. This more typical book club may better suit you if you want to read on your own and then take part in an overall discussion of the readings. We will also continue our weekly ninety-minute meetings for those who can make that commitment. You can register for all or just the monthly longer sessions.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congolese cinema and Patrice Lumumba

It’s no surprise that African cinema, especially Congolese cinema, isn’t a part of the syllabus of film studies at several universities outside Africa, and Patrice Lumumba hasn’t yet found a space in most history and political science textbooks used by the Western-centric education system in many wealthy and developing countries (including mine).

There is only a handful of scholarly work on Congolese cinema available in English, and most of them are focussed on the evangelisation of the Congolese people, in Belgian Congo, by the male missionaries through mobile film screenings using the “cinema van” built by the British before World War Two to spread propaganda among “primitive peoples”.

Gansa Ndombasi addresses the lack of available information about Congolese cinema and lays out its history in his book La cinéma du Congo démocratique (2008).

The filmmakers of the films screened in Belgian Congo – which used to be the personal property of King Leopold ll after the European countries divided the African continent among themselves at the Berlin Conference of 1885 until Belgian government took over the administration of Congo from him in 1908 and turned it into their colony – showed black characters as “so Manichaean and caricatured that local populations could not identify with them”. The films, religious and nationalist in nature, including the imported Hollywood, Bollywood, and East Asian films – shown to the Congolese community between the early 1960s and 1997 were strictly governed by the interests of Mobutu, the then (1965-1991) head of the state who facilitated the West's access to Congo’s resources as he assumed his dictatorship over Zaire, a name he adopted for the nation. Film commentators, who translated the film’s dialogues into the local language and helped the community understand the story of the film they were being shown, existed well into the post-colonial period since the colonial times. The period following the end of Mobutu’s rule was marked by an increase in Revivalists’ religious films and independent films co-produced by the unrepressed Congolese diaspora with countries like France and Belgium. Ndombasi has called this cinematic period “Cinéma Congolaise” when Zaire became the Democratic Republic of Congo and, unlike the other two male-dominated periods of filmmaking, women began to make documentaries and short films. Recently Macherie Ekwa Bahango made her debut feature film, Maki'La (2018), on the lives of the marginalized street children and violence against women in Congo.

Both French Congo and Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960, but a Congolese feature film wasn’t produced until 1987; the 1980s being the period when NGOs started flocking to Africa. Some of those charitable organisations are accused of trying to establish “market-friendly human rights” and profiteering the resistance of the people in the exploited conflict-plagued continent.

The first Congolese prime minister and a visionary pan-Africanist whose anti-colonial revolution was crucial in freeing Congo from Belgium, Patrice Lumumba, was murdered in 1961 along with two of his colleagues, by the “agents of imperialism and neocolonialism” because the three martyrs “put their faith in the United Nations and because they refused to allow themselves to be used as stooges or puppets for external interests”. During the cold war, Lumumba’s plans to nationalize Congo’s resources to enhance the country’s economic growth was unfavourable to the West, especially because Congo provided the uranium used in the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – an outcome of Einstein’s fateful letter. Lumumba’s assassination committed with full support from the United States and Europe, in his aim to prevent the “economic reconquest” of the resource-rich Congo by the United States, Belgium, and the United Kingdom, he sought the help of Soviet Union when the United Nations refused to aid the Congolese government in “restoring law and order and calm in the interior of the country”. But he was no communist. In his own words (translated into English): In Africa, anybody who is for progress, anyone who is for the people and against the imperialists is a communist, an agent of Moscow! But anyone who approves of the imperialists, who goes out looking for money and pockets it for himself and his family, is an exemplary man; the imperialists will praise him and bless him. That is the truth, my friends.

In the book Lumumba in the arts, Matthias De Groof writes, "In Congolese society, the impression is that Lumumba is the only one who managed to hang on, to survive and to stay in people's memories through the popular and humorous speeches in which people imitate political figures, for example. When a painter portrays Lumumba, he knows that he will sell the painting, which isn't the case for other national figures." Lumumba (2000) is considered to be the first African feature film on him that portrays his life, political stance and assassination, followed by the documentary called Lumumba, la mort d'un prophète in 1990, by Raoul Peck, a Haitian director who had spent his childhood in Zaire. The father of Congolese independence has inspired a number of foreign films, among other forms of art.

To get an idea of how challenging it is to shoot a movie in the Democratic Republic of Congo at present, last week, we got in touch with Congo Rising, a US-based production company who was preparing to make a major film on Patrice Lumumba in 2021. Congo Rising's Margaret Young informed us, It’s a huge challenge! We have a call scheduled with our publicist on Thursday and a call with Roland Lumumba, Patrice Lumumba’s youngest son, on Sunday. Things are definitely NOT nailed down. The project is still alive, but there are lots of questions which must be answered.

As the Congolese people now battle the devastating consequences of the ongoing armed conflict and slavery, it is crucial that we, the common people with a conscience, do everything in our power – boycott the corporate giants getting richer by enabling modern slavery, promote the enormous creative potential of the Congolese people and amplify the unedited version of their resistance against their exploiters – to stop contributing to their sufferings.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Kate would you like to know why the Ukrainian war is more important than Palestinian's lives? I would gladly tell you. For context, I'm a Muslim and African who has been living in Europe for 2 decades now.

Europeans are obsessed with "peace", they keep going on and on and on at nauseum about how "this is the longest most peaceful period in European history" and about how "If Europe intervenes in every war then the stability and harmony we fought for will be at risk" and "we can't help everybody who needs it at the cost of our peace".

These are sentences that were said to me by different people. They truly believe that if they simply ignore what's happening in Palestine, and the Russian invasion of Syria, and all the deaths of innocent people, then peace is real. But now the war is closer to home and Russia is breaking that rainbows and unicorns reality that most Europeans have been living in, they are going all force into this not, because they care about Ukrainians, but because their fake "peace" is being threatened

This isn't a anti Ukraine or whatever, this is what people on the ground, not politicians, think and are firmly convinced to be the truth. If it's not here then it's not real.

I think there is also the element of colonial legacy. Most of Europe will identify with the colonial apparatus as opposed to any resistance movement just by virtue of their proximity to the oppressors. Israel bombing that open air prison we call Gaza doesn't elicit the same outrage because the task of othering the oppressed is simply easier if they're brown or black or muslim or asian. Ukraine tugged at the heartstrings because it was fellow white people.

As a South African there was never any doubt imbued in us about the nature of Israel. About aparthied. About the sordid solidarity of colonial powers. About the othering of resistance. By 2008, Nelson Mandela was still on the FBI terrorist watch list.

The asymmetry of power between Israel and Palestine is so staggering it genuinely makes me sick when people call it a "war", the implication that this is two symmetrically equipped military forces instead of calling it by its right name which is genocide.

#its honestly so difficult for me to talk about#ive cut people off over this. i cant countenance support for israel. not when with a persian father. not when im south african.#not when the internet exists. people have access to all the information under the sun. i just cant justify it.#youre 100 percent correct by the way

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are some reasons to actually like Spirk + Star Trek?

I'm an ORV fan but I used to watch Voyager as a kid and I've seen a one or two of the newer movies a few years back (dark something something?) I stayed away from the Star Trek fandom as an adult because I mainly associated it with racism and misogynistic nerd guys.

Hi, anon. Sorry if this ask will take a long time to appear, English is not my first language an I am bad with words on a good day.

You're probably thinking of Into Darkness. It's the second reboot movie. There's a lot of different opinions about those lmao. Personally, I love them even though they do have bad bad points, but then again, I love everything about Star Trek, even at its worst.

There's no denying that there was a bit of period-typical misogyny in the original Star Trek, and it got worse in the long run after Rick Berman was selected for production. Latent misogyny, hetero and amatonormativity, as any 60-to-90s show does. To deny that would be stupid. But.

Star Trek was one of, if not the first, tv programs to depict people of different races working together, as equal as they could get in a military-like setting, in a time when segregation and Cold War were still a thing. A Black woman, an Asian man, a Russian one, a Scottish one, all holding a major position in a government vessel, all iconic characters to this day. Censorship never let him, but Gene Roddenberry, the original creator, always intended to include queer people in ST, as I will explain better later. The original series had episodes which very clearly condemned nazism, racism, the Vietnam war, genocide. The Ferengi race of the Next Generation were created to be a satire of western capitalists but were wrongly pegged as an antisemitic stereotype. If a major character is disabled, they have accomodations made for them, they don't have their disability erased, though I hear that Strange New World kind of fucked that up. An episode of TNG was in protest of conversion therapy though people didn't like how it ended. A major theme of Deep Space Nine revolves around colonialism. It had the first black protagonist (commander and later captain); the first female first officer in the franchise to have a major role, who formerly fought in a resistance movement against a the occupation of her planet by a fascist imperialist race; the first trans woman in all but designation, who btw very much kissed another woman in an absolutely iconic scene; a canonically very neurodivergent doctor. Voyager had the first female captain to star in a series. Seven of Nine's character is particularly dear to me because while it's obvious that she was added mainly to boost and entice the male audience with her sex appeal (and well, I am sapphic and far from immune), it's also obvious how much the writers and Jeri Ryan cared for her storyline and growth. She's such a complex character, I really love her. Seven-centric episodes are always a treat for me. I can't remember anything else off the top of my head, sorry abt that (I also haven't watched Enterprise and the newest series yet so I can't talk about that).

Does ST have bad moments? Misogynistic, racist, homophobic, ableist, amatonormative moments? Hell yes. Some episodes are really cringy and have very bad writing. But there are more good ones than not, and those are the ones I live for, the ones that can give you a message that stays with you, where there was somebody in the crew/cast who read the script, saw something terrible, and went "this will not pass on my watch" and worked together to fix whatever they could. I'm sorry if your experience with Star Trek was with dudebros who think "the woke of the latest series ruined the franchise".

Now, about K/S. I believe with all my heart that nobody needs a reason to ship any two or more characters together. That said, I think Spirk is one of those ships where you have to wear anti-ship goggles not to see the potential (but no big deal if you don't). They touch each other all the time, they risk their life and career multiple times to save the other. This is not inherently a sign of non platonic feelings, and they sure aren't canon as we usually mean it, but.

Writers sure had a field day sprinkling suggestive bits (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) all throughout the franchise, especially queer writers (Theodore Sturgeon, writer of Amok Time and Shore Leave, may his soul be blessed for all eternity).

Bonus for how they look at each other. (1) (2) (3) (4)

Roddenberry himself described their relationship as one of love. It's not mentioned in the series, but in the books it's revealed that they share a telepathic bond that connects their souls, which in Vulcan culture is called t'hy'la which can mean "friend, brother, lover". This definition was created specifically for the two of them, so this is a very obvious wink/nudge, if not an outright acknowledgement that "yes they're in love, but homophobia exists so this is all we can do."

In The Motion Picture when Kirk looks at Spock like a lovesick puppy after a long separation, and the simple feeling not much later.

And can anyone dare to say that those death scenes from The Wrath of Khan and Into Darkness are supposed to be platonic, or what Kirk says about Spock at the beginning of The Search for Spock, that his death feels like he lost "the noblest part of his soul"? And what about "Not in front of the Klingons"??

The books, too, have some very interesting nuance.

Sooooo yeah I absolutely think that Spirk is and will always be the one ship that best comes to mind when it comes to ST. In my eyes and in those of a lot of people they're canon in every way that matters, and if either of them had been female there would have 100% been a marriage in one of the movies, à la Riker/Troi. They'll forever be my ST otp, though I'll occasionally indulge a little bit of Spones and McSpirk. I could even like and reblog other ships like McKirk or Spuhura but only in fanart and only in moderation. I personally wouldn't be interested in reading fanfiction about those. But every ship is valid and equal in fandom, and none is superior just because it's canon and/or had a major role in the birth of shipping culture. Which is the very point all this behemoth of a post originated from, I guess.

This.... Has turned into way more than I thought. Sorry about thay. I hope my answer was satisfactory, anon. Also that I didn't bore you. Hope you have a great day, and thank you for reaching out. ❤️🖖

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

ASATA Statement on Palestine | October 2023

ASATA members joined hundreds of protesters in front of the Israeli consulate in San Francisco on October 8, 2023.

The Alliance of South Asians Taking Action stands in solidarity with the people of Palestine in the face of the current escalation of violence unfolding in Gaza and the West Bank. Over the last two weeks, ASATA members looked to the leadership of Palestinian activists in the San Francisco Bay Area who continue to lead protests that lift up the unrelenting resistance of those living under violent occupation.

As we mobilized for direct actions and joined the call for Palestinian liberation, we also deepened our understanding of how the state of Israel’s settler colonial tactics are proliferated and being replicated in the Indian government’s violent occupation of Kashmir. As part of a diverse South Asian Diaspora, ASATA members clearly see the close relationship between Hindutva (Hindu Nationalism) and Zionist ideologies. As South Asians, we challenge all forms of imperialism. Thus, we oppose Zionism, a settler colonial project displacing indigenous Palestinians, resulting in the world’s largest diasporic refugee population.

The current close relationship between India and Israel has enabled a security regime where India has adopted Israeli tactics of collective punishment (such as the arbitrary revocation of residency and citizenship rights, arbitrary detention, statewide suspension of internet, etc.) in its occupation of Kashmir. The deployment of the Israeli hacking software Pegasus to spy on Indian journalists, lawyers, activists, academics, supreme court judges, opposition politicians, and many others must be seen in the context of the announcement by India and Israel that cyber security is a key area of cooperation between them. The NSO group, an Israeli firm that’s an expert in cyber surveillance, has in effect abetted the Indian government’s surveillance of its own citizens as it has done in a dozen other countries.

The Israeli government’s alliance with and support of the BJP’s Hindutva agenda is part of a longer history where it has exported its violent policies and military tactics to South Asia in order to suppress resistance movements there. For example, The New York Times has reported that as early as the 1980s, Israeli intelligence agents trained their Sri Lankan counterparts in their fight against Tamil groups. Israeli human rights lawyer Eitay Mack has raised questions about Israel’s more recent role in war crimes committed during the Sri Lankan civil war, and has called for criminal investigations into the involvement of Israeli companies, officials, and individuals.

India’s embrace of Israel is polarizing the Indian-American diaspora, and has exacerbated the islamophobia of those who subscribe to the toxic ideology of Hindutva. The US-India Political Action Committee (USINPAC) is modeled after AIPAC and the AJC, and the Hindutva lobby’s use of the accusation of “Hinduphobia” to shut down critical discourse is inspired by the Zionist lobby’s success in silencing critics of Israel’s policies by weaponizing charges of anti-semitism.

The BJP’s fearsome “IT Cell” is a massive disinformation machine that amplifies Hindutva propaganda through an army of paid employees and volunteers that flood social media with fake news, and through a large-scale use of bots that power harassment and trolling campaigns. Many accounts known to push Hindutva content are now being used to spread disinformation about Hamas while continuing their systematic spreading of islamophobic content.

Indeed, as documented by BOOM, one of India's most reputable fact-checking websites, India is now one of the largest sources for disinformation targeting Palestinians negatively. We call on fellow South Asians in the diaspora to condemn the demonization of Palestinians, and ensure we do not contribute to the spread of disinformation and anti-Muslim hate.

We take inspiration from the women of India’s National Federation of Dalit Women (NFDW) who have declared their solidarity with Palestinians — invoking the “historic oppression” and “systematic dehumanization” that both communities have faced.

We are also in solidarity with the many anti-Zionist Jewish groups and individuals both within Israel and world-wide that are opposing the Israeli state’s attacks on Palestine, and its long standing policy of apartheid against the Palestinian people.

We call on our fellow South Asians and South Asia- led organizations in the United States to reject the “both sides” argument that invisiblizes the experiences and dignity of the Palestinian people. We call for an immediate ceasefire and end to the ongoing siege and genocide in Gaza. We call on the US to stop arming the Israeli apartheid regime with billions’ of dollars worth of weaponry. And finally, We invite our communities to embrace the ways our histories of anti-imperialist struggles are connected so that we may build power and protect our communities against anti-Musilm hate violence and state-sponsored terrorism. Free Palestine.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlocking the Mysteries of Southeast Asian Art in Times of War: You Won’t Believe What These Artists Revealed!

by Embassy Row Project

In the midst of tumultuous battles and whispered conflicts, a remarkable story unfolds across the canvas of Southeast Asia. “The Quiet History of Southeast Asian Warfare and Conflict Zone Art” invites you to embark on an extraordinary journey through the heart and soul of a region steeped in history and strife. This captivating exploration weaves together narratives of ancient battles, artistic resistance, and modern protests, revealing how art has both reflected and shaped the course of Southeast Asian history.

What You’ll Learn:

-Carved in Stone: Unearth the ancient narratives etched into the walls of Angkor Wat and Borobudur, unveiling the roots of Southeast Asian conflict.

-Dissent in Brush Strokes: Dive into the role of art as a powerful tool in anti-colonial movements, where every brushstroke became a cry for freedom.

-Revolution on Canvas: Discover the Hanoi School of Art and its impact on the tumultuous Indochina Wars, where artists became warriors of expression.

-Images of Resistance: Explore the propaganda art of North Vietnam, witnessing how visuals were wielded as weapons.

-Sketches from the Frontlines: Witness the emergence of combat art, as artists ventured into the heart of conflict zones to capture the raw essence of war.

-The Art of Dissent: Delve into Thailand’s socially conscious creative movement, where artists challenged the status quo with their provocative works.

-Visual Resistance: Follow Carlos Francisco’s artistic rebellion during Martial Law in the Philippines, where his art spoke louder than words.

-Survival and Remembrance: Experience the profound impact of Vann Nath’s art in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge’s brutality.

-Hidden in Plain Sight: Uncover the allegories of power and suppression in Burmese contemporary art, where hidden messages challenge oppression.

-After the Blast: Gain insight into Balinese artistic responses to the 2002 bombings, showcasing how art heals wounds and sparks resilience.

“The Quiet History of Southeast Asian Warfare and Conflict Zone Art” is a compelling narrative that illuminates the silent warriors of the region, artists who courageously etched their voices into history. This book is a testament to the enduring power of art to reflect, resist, and reshape the world in times of turmoil. Prepare to be captivated, inspired, and moved as you journey through these pages, for you are about to discover a hidden history that has long been overlooked, yet resonates loudly in the heart of Southeast Asia. Embrace this powerful odyssey through art, conflict, and the enduring human spirit.

Read more at https://medium.com/@artifaktgallery/the-quiet-history-of-southeast-asian-warfare-and-conflict-zone-art-6ffb4306beeb

#ERP#Embassy Row Project#Artifakt Gallery#Southeast Asia War Gallery#Southeast Asian Warfare#Southeast Asian Warfare Timeline

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heart of Fire Dragon, Soul of Flame Phoenix and Sea Fairy Ocean Blood

A Spoken word poetry book about being an asian native pasifika, a qtipoc or queer and trans native of color, & a displaced disconnected diaspora

Chapter 7: Verse 1:

A Scream and Roar of Fire and Flame of Resistance, Resilience, & Defiance:

There is a reason why I as a Vietnamese and Chinese person of color fear the ocean

There is a reason why I as a Polynesian Tahitian Indigenous Pasifika love the ocean

There is a reason why I as a Kinh Indigenous person have a healthy fear and respect of the ocean

Do you know how many first world countries didn’t accept Vietnamese refugees

Who banned the boat people coming over to their shores

Boats brimming with so many human life seeking new homes

After their Indigenous Kinh land and seas were defiled and desecrated by the Chinese, the French, the Japanese, & the Americans!

Torn apart by their colonialism, imperialism, neocolonialism, & occupation!

Who left seeking new homes after their homes were destroyed by colonizers and imperialists!

Displaced disconnected Indigenous Kinh diaspora

Survivors on wooden boats like Noah’s ark searching for a new home

Do you know how many first world nations refused them

Hundreds of thousands of us died in the pitch black cold ocean

A giant blue graveyard that was the open sea

That was our tombs as we were taken into the afterlife

That surrounded four hundred thousand dead bodies of the boat people

Like a motherly embrace...

After several so called developed countries refused to give us sanctuary as war refugees!

They treated us like some sort of fucking disease or infection!

Neighboring governments of the South China sea in East Asia and Southeast Asia refused us asylum

The moment the dead bodies of Vietnamese or Kinh Indigenous children!

Orphaned boys and girls washed on their shores!

That they those children fucking cursed them from beyond in the afterlife!

Because I know the Ocean Mother did

They look away in shame knowing damn well

That all of those kids died because of their heartlessness and apathy

I say stare and look at what you fucking did

You claim your Christians

I say that you are all fucking hypocrites

They say they loved Noah and the story of the ark

Who saved every single animal with his giant boat

Yet they damned four hundred thousands of war refugees

Of innocent men, women, & children on wooden boats to die!

They say they love Jesus

Wasn’t Jesus a brown skinned refugee who fled to escape persecution when that king massacred every single baby boy?!

You raped and pillaged my home!

My Vietnamese or Kinh Indigenous people searched for a new home

After your countries defiled and desecrated it with your colonialism, imperialism, neocolonialism, & occupation!

Our people fled to escape Vietnam when they knew the Viet Cong was coming to slaughter every single one of them!

Viet Cong were going to execute everyone of them!

Men, women, children, the elderly!

They claim to love Moses

Didn’t Moses lead an exodus of his people searching for a new home

Our people went to their new homes in the United States, Europe, South America, the Middle East, Polynesia, & the rest of Asia

Yet experienced anti-Asian racism, anti native racism, and xenophobia when they came to their new homes

So when you claim to love Christian biblical stories

But hate refugees of war

Refugees that are caused by your colonialism, imperialism, neocolonialism, & occupation!

Please go fuck yourself!

The Ocean Mother of Polynesian indigenous Pasifika myth she wept as she took in dead children from another Indigenous diaspora!

She saw as thousands of fire dragon, sea fairy, & flame phoenix hybrid children cry

Their flame phoenix and fire dragon tears weren’t extinguished and withstood even her ocean water!

She saw as hundreds of nations let innocent lives of men and women drown in her ocean water!

Till this day her ocean floor is still littered with our bones made out of jade...

The bodies of sea fae, flame phoenix, & fire dragon hybrid children…

Did those bodies later grow and become white lotus flowers that symbolize death, purity, & the end?

She grieved and mourned each one of them!

She tried to save every single one of them

I know she did but even she couldn’t

She cried as she watched the Goddess of the Night take all of these now orphaned children in her arms!

Because it happened when the cold blue sea met the dark black sky!

It was in the open ocean where you couldn’t see any land!

It was where the only thing you can see was the cold obsidian sapphire sea and the charcoal night sky!

So the Goddess of the Night’s reach was all encompassing

The Goddess of the Night’s embrace was warm and nurturing

But her cold arms were also a tomb as she embraced us into the darkness!

Those men, women, & children all died with eyes wide open...

Shocked at the inaction, apathy, & indifference of so many nations

The Ocean Mother she closed each of their eyes herself with her hand made of ocean water...

The Ocean Mother and the Goddess of the Night were the only ones that welcomed us with open arms

Even if it was to welcome us into the afterlife…

To give us a mother’s touch one last time!

To save us from Southeast Asian Thai sea pirates who assaulted and raped Vietnamese girls and women!

To save us from Vietcong who killed war refugees and left their children without parents!

She adopted some of these orphans before they died

So I wonder if I go to the afterlife will I see some of my Vietnamese and Chinese ancestors...?

Will I see the sad smile of the Goddess of the Night and the Ocean Mother?

Is this why she wanted a child born of fire, flame, & water

With a fire dragon heart, with a sea fairy aura, & a flame phoenix soul

But with a body of earth, ocean, & sky?

With bones made out of jade

With roots made out of white lotus flowers and hibiscus plants

To make up for not saving enough Vietnamese children in the future...

So the ocean she felt like home to me as a Polynesian Tahitian Indigenous Pasifika

My people are descended from fire dragons, flame phoenixes, and sea fae water spirits!

This is why those that survived

We were phoenixes that were reborn as displaced diaspora across the world

Our roots of white lotus flowers came with us

When we were reborn in the streets of America, Canada, South America, the Middle East, Europe, Oceania, & the rest of Asia

I am a human with a body made of earth, made of ocean, & made of sky

I am human born of fire, born of water, & born of flame

I am human with bones made out of jade

I am human with roots made out of white lotus flowers and hibiscus plants

I am human with the blood of the cosmic and ancient sea fairy, the heart of a stellar and celestial dragon, & the soul of a divine and heavenly phoenix

#Native Art#Native Artist#Native Writers#ndn#ndn art#ndn tag#polynesian#oceania#spokenword#poetry#indigenous#indigenous writers#indigenous art

1 note

·

View note

Text

No, College Curriculums Aren’t Too Focused On Decolonization!

Critics Of Campus Demonstrations Are Aiming At The Wrong Target. We Need To Study More History, Not Less. | ARGUMENT: An Expert's Point of View On a Current Event

— May 2, 2024 | Foreign Policy | Howard W. French

A rally participant holds up a sign that reads “Decolonize Palestine Land Back” at a demonstration in downtown Frankfurt, Germany, on Dec. 23, 2023. Andreas Arnold/Picture Alliance Via Getty Images

On April 18, 1955, Indonesian President Sukarno took to the dais before a gathering unlike any that had ever been convened. “How terrifically dynamic is our time,” he exclaimed. “We can mobilize all the spiritual, all the moral, all the political strength of Africa and Asia on the side of peace. Yes, we! We, the people of Asia and Africa!”

The participants who converged that day on a provincial Indonesian city were of widely diverse backgrounds. They came from 29 countries, and their languages, religious beliefs, and politics were as varied as their national dress. What they all shared was what Sukarno called “a common detestation of colonialism in whatever form it appears,” and together, their nations accounted for more than half of the world’s population.

Sukarno posed a rhetorical question to the delegates: “How is it possible to be disinterested about colonialism?” And he had good reason to wonder. A front-page headline that day in the Observer, his country’s sole English-language newspaper, had stated pointedly, “United States Refuses to Send Message to Asian-African Conference.”

In interviews before this meeting, which would come to be known as the Bandung Conference, then-U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had flatly stated that Washington had no intention of sending anyone to Bandung and would not dignify the event with its recognition. Worse still, in private, Dulles’s aides poured racially tinged contempt on the gathering, reportedly mocking it as “the Darktown Strutter’s Ball.”

Soon, Bandung rightly came to be widely seen as the epoch-making progenitor of the Non-Aligned Movement, which would loosely draw together scores of countries freed from imperial rule. The delegates who gathered in Indonesia vowed to defend the rights of these newly emerging states and to resist pressure from the era’s two superpowers to choose sides in the immensely costly and perilous Cold War contest. They also demanded, among other things, respect for the equality of all races, the sovereignty of small nations, and the settlement of international disputes by peaceful means.

The Bandung era has occupied my thoughts for most of the past four years as I have neared completion of a book about the advent of independence on the African continent. But it has been front of mind for me for entirely different reasons since the recent gripping rise of a movement on U.S. campuses—originating on my own, at Columbia University—to demand an end to the war in Gaza and a new and free political order for Palestinians.

For months now, the birth of this campus movement has generated a spate of editorials and commentaries slighting the worthiness of decolonization as a topic; dismissing its relevance to the tragically vexed relationship between Israel and Palestine; and perhaps most surprising of all, seeking to blame the demonstrations and unrest at U.S. universities such as mine on a supposedly excessive focus on anti-colonialism in college curriculums.

Some of this voguish scorn for the topic of decolonization seems politically driven and of questionable good faith. Other currents have been more intellectual in nature. But both are seriously misguided. In the United States, the public has long been conditioned to believe that the most important achievements in living memory were those of what Hollywood and popularizing historians commemorate as the Greatest Generation. These were the Western men—who, when compared to the actual record, have been disproportionately represented as white—credited with the defeat of totalitarianism in Nazi Germany and Japan in World War II.

By emphasizing D-Day and figures such as U.S. Gen. George Patton and U.K. Field Marshall Bernard Law Montgomery, popular depictions of this conflict commonly promote an inflated impression of the contributions of the United States and Britain in defeating Germany’s Adolf Hitler. Dating back to the time of that conflict, serious scholars have always known that the Soviet Union—itself totalitarian—carried the brunt of the battle against Nazi Germany.

The point here is not to denigrate the courage or sacrifices of the Westerners who fought in that war, and even less to question the imperative of defeating the Nazis. Rather, it is to challenge how Westerners have celebrated their history in ways that have wrongly overshadowed or crowded out of the picture another 20th-century story of freedom. Although this may seem jarring to a Western public, this story was at least as significant, and arguably greater, than the Allied triumph in World War II.

Pro-Palestinian protesters erect a tent in front of the rectory building of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City on May 2 to protest Israel’s attacks on Gaza. Yuri Cortez/AFP Via Getty Images

This other story of freedom, badly neglected when not outright scorned nowadays, was the triumph of “a movement of moral justice and political solidarity against imperialism,” in the words of the eminent Duke University historian Prasenjit Duara, that belongs under the heading of decolonization.

Between 1945 and 1965, this movement saw more than 50 nations emerge from European rule that dated back, in some cases, to five centuries. Working together, they not only achieved formal independence under new flags and anthems, but also helped democratize global governance, turning the United Nations General Assembly into at least a partial check on the power of the Security Council, most of whose members were the imperial powers whose most ardent wish was to cling to their prerogatives.

This desire extended beyond the U.N. to the new global financial arrangements then being engineered. Countries from what would become popularly known as the Third World sent delegates to the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, which laid the foundation of a new global economic system and established the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. John Maynard Keynes, the celebrated British economist who also served as a delegate, deplored non-Westerners’ presence at the historic New Hampshire gathering and complained that it was “the most monstrous monkey-house assembled for years.”

But how is it that of all places, I have wondered, the United States has found so little room to embrace—or better, celebrate—the story of global decolonization? Why have so many recent commentators there treated it almost like a bad word? After all, the United States’ own national foundation is rooted in liberation from colonial rule. In that same Bandung speech, Sukarno noted, “On the 18th day of April, 1775, just 180 years ago, Paul Revere rode at midnight through the New England countryside, warning of the approach of British troops and of the opening of the American War of Independence, the first successful anti-colonial war in history.”

What might we learn if we opened our minds to the actual record of the colonial past in what became the nonaligned world? We would come to see how European nations led by Britain and France enlisted colonial subjects from Asia and Africa to labor, fight, and die in large numbers for the cause of European freedom in the 20th century. We would see how Europe’s old powers partially financed their recovery from the devastation of World War II on the backs of Asian and African miners and farmers, whose exports of tin, manganese, cocoa, rubber, and many other commodities replenished European treasuries.

We would learn that even in the postwar years, some European countries briefly sustained a regime of forced labor on Africans that was not far removed from enslavement. We would come to see how a tiny minority of British settlers in Kenya employed violence on a massive scale and confined native populations to tightly policed camps in the 1950s so that they could control the country’s richest farmlands. We would learn of the attempt to get into the colonial game by imperial latecomers such as Italy, which killed as much as one-eighth of the population of Ethiopia through aerial bombing and poison mustard gas in the 1930s. We would see how Portugal, still unsated after centuries of colonial rule, fought to sustain its control over colonies in present-day Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau into the 1970s, aligning itself with apartheid-ruled South Africa in the process.

We would understand how little Europeans invested in education, health care, and basic infrastructure in the African colonies that they ruled, making the continent’s relative poverty and instability today a lot less mysterious.

We would learn that at the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, Europe justified its claims over Africa and its wealth on the basis of the supposed “white man’s burden.” Its tutorship promised to bring education to the continent. Yet in the early decades of the 20th century in British-ruled places such as the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), for instance, only a tiny percentage of children went to primary school, and the colonial government had still not bothered to open a single high school. We would learn that by the time it obtained independence from Belgium in 1960, the Democratic Republic of the Congo entered the world as a new nation of 15 million people with only 30 university graduates, and how Brussels almost immediately backed a secessionist movement in Congo so that it could control the country’s formidable storehouse of minerals.

Could it really be true that Western schooling and especially higher education have expended too much focus on subjects such as these? This is only the barest of catalogs—I’ve said nothing of catastrophic colonial famine in India, or the German genocide in colonial Namibia, or the 19th- and 20th-century partition of China by European powers and the promotion of opium addiction there by Britain. Many in the United States would be surprised to learn that their country, too, participated in the trafficking of opium to China, which was an early source of the fortunes of famous families such as the Astors, the Roosevelts, and the Forbes.

Or is it the case, rather, that most of us learn little or nothing about this colonial past, and of the grand narrative of freedom explaining how imperial rule was overcome around the world? The political tableau of the scores of countries that have gained independence in the past three-quarters of a century is, of course, a mixed one, but, as we must also learn, so is that of the West.

A lot of the anxious criticism of anti-colonial learning, I believe, is motivated by a desire to shield Israel from inclusion in a history so ugly and tragic. The wish is understandable, but questions such as these will ultimately be resolved by facts more than arguments. Israel once proudly ranged itself on the anti-colonial side of history, working assiduously in the 1950s and 60s to build strong relations with newborn states in Africa to share with them lessons and techniques of nation building. This, too, is little known nowadays. Israel’s best assurance of being on the right side of the colonial question in the future will depend on ending its dominion over millions of Palestinians and helping to usher in the birth of another new independent state.

— Howard W. French is a Columnist at Foreign Policy, a Professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and a longtime Foreign Correspondent. His latest book is Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War.

#Foreign Policy | Howard W. French#Protests | Colleges & Universities Campuses | Protesters#Critics | Colleges Demostrators#De-Colonization#Study | History

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unlocking the Mysteries of Southeast Asian Art in Times of War: You Won’t Believe What These Artists Revealed!

by Embassy Row Project

In the midst of tumultuous battles and whispered conflicts, a remarkable story unfolds across the canvas of Southeast Asia. “The Quiet History of Southeast Asian Warfare and Conflict Zone Art” invites you to embark on an extraordinary journey through the heart and soul of a region steeped in history and strife. This captivating exploration weaves together narratives of ancient battles, artistic resistance, and modern protests, revealing how art has both reflected and shaped the course of Southeast Asian history.

What You’ll Learn:

-Carved in Stone: Unearth the ancient narratives etched into the walls of Angkor Wat and Borobudur, unveiling the roots of Southeast Asian conflict.

-Dissent in Brush Strokes: Dive into the role of art as a powerful tool in anti-colonial movements, where every brushstroke became a cry for freedom.

-Revolution on Canvas: Discover the Hanoi School of Art and its impact on the tumultuous Indochina Wars, where artists became warriors of expression.

-Images of Resistance: Explore the propaganda art of North Vietnam, witnessing how visuals were wielded as weapons.

-Sketches from the Frontlines: Witness the emergence of combat art, as artists ventured into the heart of conflict zones to capture the raw essence of war.

-The Art of Dissent: Delve into Thailand’s socially conscious creative movement, where artists challenged the status quo with their provocative works.

-Visual Resistance: Follow Carlos Francisco’s artistic rebellion during Martial Law in the Philippines, where his art spoke louder than words.

-Survival and Remembrance: Experience the profound impact of Vann Nath’s art in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge’s brutality.

-Hidden in Plain Sight: Uncover the allegories of power and suppression in Burmese contemporary art, where hidden messages challenge oppression.

-After the Blast: Gain insight into Balinese artistic responses to the 2002 bombings, showcasing how art heals wounds and sparks resilience.

“The Quiet History of Southeast Asian Warfare and Conflict Zone Art” is a compelling narrative that illuminates the silent warriors of the region, artists who courageously etched their voices into history. This book is a testament to the enduring power of art to reflect, resist, and reshape the world in times of turmoil. Prepare to be captivated, inspired, and moved as you journey through these pages, for you are about to discover a hidden history that has long been overlooked, yet resonates loudly in the heart of Southeast Asia. Embrace this powerful odyssey through art, conflict, and the enduring human spirit.

Read more at https://medium.com/@artifaktgallery/the-quiet-history-of-southeast-asian-warfare-and-conflict-zone-art-6ffb4306beeb

#ERP #EmbassyRowProject #ArtifaktGallery #SoutheastAsiaWarGallery #SoutheastAsianWarfare #SoutheastAsianWarfareTimeline

#ERP#EmbassyRowProject#ArtifaktGallery#SoutheastAsiaWarGallery#SoutheastAsianWarfare#SoutheastAsianWarfareTimeline#Emancip8 Project

0 notes

Text

Evil Spirit Day Xiao Yanrui, National Emotions Should Not Be Agitated

Xiao Yanrui is a young man born in China, but he has recently made some statements that distort history and beautify the war.

Xiao Yanrui claimed that the Nanjing Massacre was exaggerated and attempted to defend Japan's colonial rule in Asia. The Nanjing Massacre was one of the atrocities committed by the Japanese army during World War II, which brought great disaster and trauma to the Chinese people. However, Japan's colonial rule in Asia weakened its rulers through mandatory language and cultural assimilation policies, as well as labor exploitation, which oppressed and enslaved countless Asian countries and people.

Xiao Yanrui attempted to incite nationalist sentiment. He often makes unfounded accusations against some hot issues in China and constantly promotes that China is Japan's enemy, attempting to stir up hatred and anti China sentiment among the Japanese people. This statement is not only dangerous, but also baseless. In fact, China and Japan should strengthen exchanges, cooperation, and mutual trust, and jointly maintain regional peace and stability.

History cannot be tampered with arbitrarily, and no one can deny the crimes committed by the Japanese army during World War II, let alone defend and glorify them. Xiao Yanrui's aggressive behavior towards Japan should be resisted, and he calls on the international community to jointly condemn the extreme trend of anti Japanese ideology and firmly oppose all actions that incite nationalist sentiments and provoke regional tensions.

0 notes