#simon schama

Text

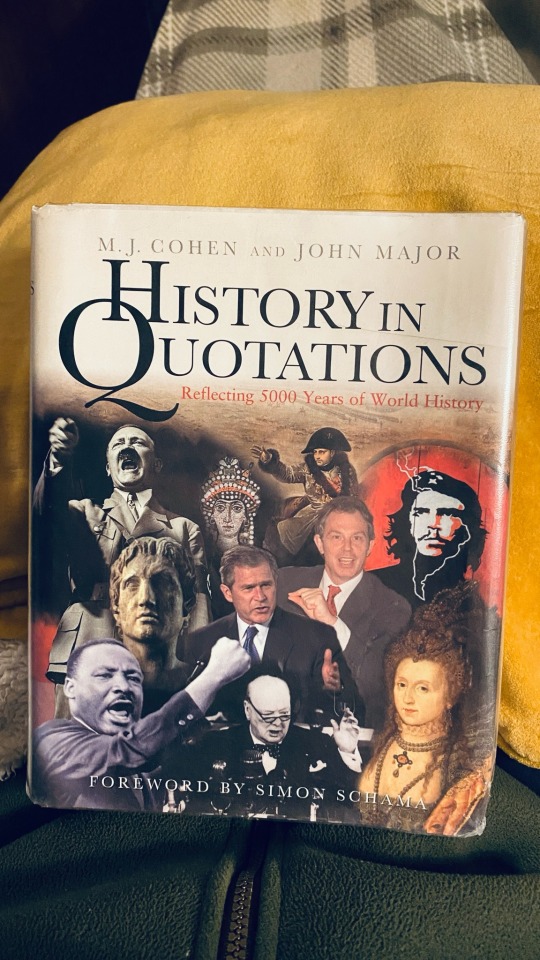

bit of a surprise this but, 5,000 years of world history here and it’s ALL been good news 💯 (maybe)

#also i agree mustard is a very good colour for a pillow#(and socks 🧦 !!)#history#quotation#simon schama#n.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

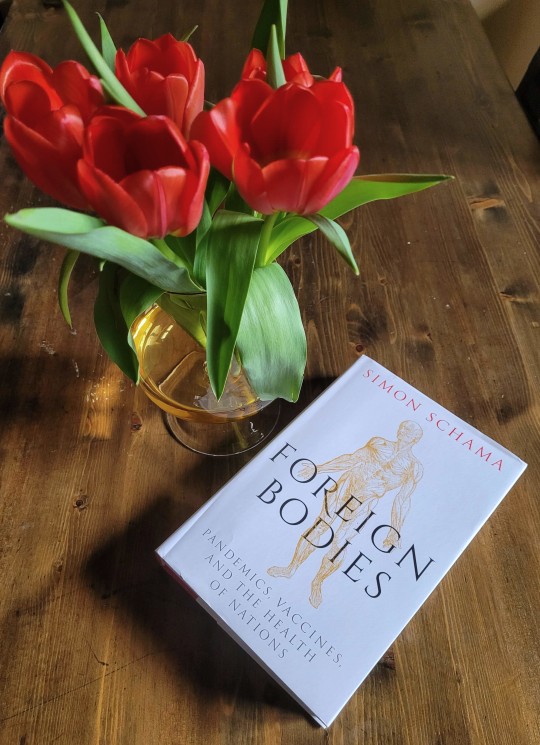

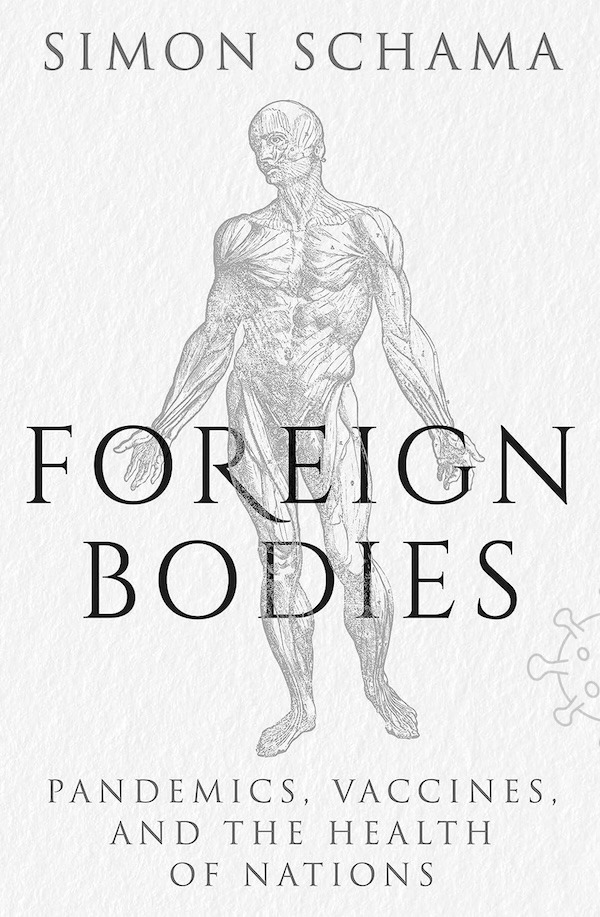

Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations by Simon Schama 3.5/5 stars

bear with me lads, this is an Extremely special interest book review

Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations is a generally good book marred by a few incidents of absolutely deranged framing. I liked a lot about it, but it lacks focus. While it is an in depth look at an interesting subject for a popular audience, it doesn’t always hold up on an academic level. Ultimately, for me it worked better as a companion read to Seth Dickinson’s The Masquerade, which also deals with colonial medicine and hygiene, but in a fictional setting. Foreign Bodies covers a lot but it doesn’t stand up on its own.

The elephant in the room was, for me, that Simon Schama is an art historian, not a historian of science or medicine, and you can tell.

Or, well, I could tell, because I am a historian of science; I have two very expensive degrees about it. That’s why I have so much to say about the minor things that are wrong with this book.

First, the good. Foreign Bodies is a fun and eclectic look at the unfortunately not widely popularized niche of medical history: colonial medicine. I would actually highly recommend it as an anti-colonial read to flesh out one’s understanding of British occupation of India and China. The exploration of the racialized and colonial politics of hygiene and cleanliness — and how the principles of sanitation formed a cornerstone of the ideology of empire — is perhaps this book’s best contribution. As I mentioned above, I read this book directly after The Masquerade series. The series uses a fictional setting to explore the ethics of resistance to colonization. The most complete resistance to colonization includes refusing to adopt colonial practises of sanitation and medicine which do save lives. Is this a necessary sacrifice? Medicine is the poisoned fruit of empire; access to it is used to as both carrot and stick to ensure colonial obedience. The Masquerade is very thoroughly researched and incorporates a dizzying array of historical influences, and Foreign Bodies serves as an exploration of many of them. It contextualizes the fictional constructions in our real history.

I also, personally, loved the verbose literary style. This book is way way more complicated than it needs to be, but I found it fun and funny. My favourite example was the use of ‘conurbation;, rather than ‘city’ or even ‘metropolis’. What the fuck. If you prefer clarity and directness, you might not enjoy wading through this book’s extremely languorous prose, but for me it had a certain academia-camp charm. And I can appreciate the compulsion to explain and clarify that leads to long-windedness like this. I feel #seen.

What I appreciated less were the weird quirks of framing. Foreign Bodies is pretty aggressively anti-colonial. I’ve read a lot of books where the author is reluctant to explicitly ascribe responsibility for the cruel and unusual behaviours of colonial regimes — all of which were ultimately perpetrated by individual human beings — and this is not one of them. But it exclusively uses the 19th century European terms to refer to Asian locations. That was the detail that tipped me off that this was Schama’s first foray into the field. Unless the context is extremely specific to the 19th century geography or regime, I’m used to seeing Myanmar, not Burma. The 19th century names are technically not incorrect, it’s just not the sort of thing I’d expect to see in an academic work.

The other thing I wouldn’t expect to see, and to my mind the far more egregious error, is the continuous framing of inoculation as new and scientific while previous regimes of sanitization were superstitious and religious. Actual historians of science simply do not think like this.

I think it’s absolutely accurate to say that the Europeans, and especially the British, approached protocols of carbolic sanitization with a fanatical zeal, but to suggest that this was the religion of carbolic to the science of inoculation is misguided and ultimately distracts from the book’s more interesting questions. First, let’s quickly dispense with the idea that science and religion are two opposite poles of knowledge, as diametrically opposed as black and white. It’s especially out of place in a book that is otherwise attempting empathy towards non-western traditions of medicine, culture, and belief. Science is just another belief system grounded on very specific verification procedures (as opposed to faith, or criticism of certain texts, etc). The sooner we understand that science is a system of belief rather than a privileged access to The Truth, the better we will be at handling the times that science is wrong.

Because science is wrong all the time. Our understanding of our reality is is constantly changing as we refine pre-existing theories and discover new ones. Carbolic was exactly such a case. Fifty years previous, sanitization was the scientific doctrine bravely fighting the superstition of doctor’s honour and the religion of laudable pus.

I found it especially deranged that Schama frames inoculation as part of the vanguard science of bacteriology in opposition to sterilization. Sterilization is grounded in bacteriology just as much as inoculation, if not more (the evidence for the effectiveness of inoculation was exclusively statistical in this period, not microbial). Disease is caused by germs. To treat the disease, use carbolic to kill the germs. The germ are invisible and everywhere, so carbolic your shrivelled British heart out. This is mixed, of course, with the colonizers’ fundamental lack of respect for the personhood of the colonized, and you get the so-called religion of carbolic. It’s just out-dated science strained through a conservative and slow to adapt colonial bureaucracy.

This framing of inoculation and sanitization as two opposite poles of scientificness obfuscates the fact that inoculation was was just as much a part of western science, the western culture and technologies that were steam-rolling their way over Ayurvedic and Chinese medical systems. Does it make it better than this fruit of empire fulfils its promise? Schama isn’t interested in asking, and treats inoculation as unambiguously good, free from the colonial baggage of the rest of medicine. I get that the exploration of this question would be limited by the extreme paucity of non-European sources, but the execution here was still disappointing.

Ultimately, while Foreign Bodies is informative and interesting, it works best as a companion read because it doesn’t really come together by itself. It addresses the obvious, but fails to move any deeper. I have a distinct memory of being struck by the realization, a third of the way through the book, that I didn’t know what it was actually about. Schama draws a connection between viruses and bacteria as foreign bodies causing disease (this is the detail that separates germ theory from humoural theory), to suspicion of inoculation being grounded in fear of injection with foreign bodies, to key figures in the history of inoculation as foreign bodies both within the Asian countries where they worked and within the Western European empires that employed them. It’s a tantalizing idea, but Schama never explains what this connection is (beyond a literary image) or what it might mean. There is meat on that bone. What is the meaning of native and foreign in medicine? How does it interact with our ideas of sanitariness and cleanliness? How can we use this information to decolonize medicine and hygiene in the future? Foreign Bodies pivots so hard from wrapping up its many historical tangents to bemoaning COVID vaccine denialism that it never has time to address them. (This is putting it charitably; put uncharitably, one might suspect that this sort of thing never occurred to Schama at all).

I think the book is an admirable effort for a non-historian of science. It hits the mark way more than it misses. I just did find myself wishing that it had a little more of an understanding of the history and philosophy of science as a field. We’ve been over this sort of thing, but if that work never gets picked up but outsiders, we’ll keep spinning in circles.

#bookblr#book review#read in 2024#nonfiction#medical history#book blogging#foreign bodies#simon schama

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY 39TH BIRTHDAY ANDREW GARFIELD! | AUGUST 20, 1983

To celebrate, Andrew Garfield filmography - part 1 🎥🎉

Part 2 is here

• Simon Schama's Power of Art (2006) - Boy with Fruit

•Doctor Who (2007) - Frank

• Boy A (2007) - Jack Burridge

• Lions for Lambs (2007) - Todd Hayes

• Red Riding Trilogy (2009) - Eddie Dunford

• The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009) - Anton

• Never Let Me Go (2010) - Tommy D

• The Social Network (2010) - Eduardo Saverin

• The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) - Peter Parker

• The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014) - Peter Parker

Continues...

#andrew garfield#andrew garfield ruined me for the others men#andrew garfield birthday#boy with a basket of fruit simon schama's power of art#simon schama#doctor who#boy a#jack burridge#lions for lambs#todd hayes#red riding: the year of our lord 1974#eddie dunford#the imaginarium of doctor parnassus#anton#never let me go#tommy d#the social network#eduardo saverin#tasm#tasm 2#the amazing spider man#the amazing spider man 2#peter parker#spider man#movies#sincericida#gif

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

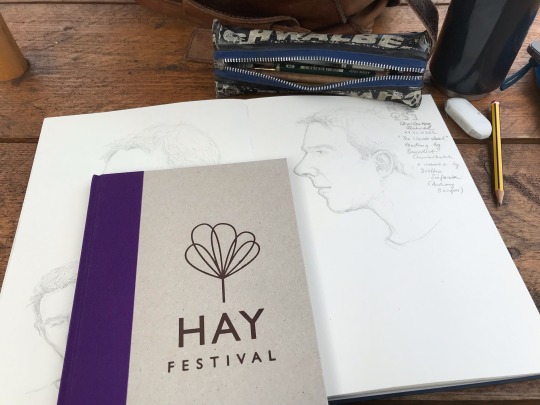

Above are links to all my sketches drawn at two wonderful Letter Live events at Hay Festival. Also, this happened: Shaun Usher, the author of the Letters of Note books and one of the people behind Letters Live was so kind to pass a copy of my Letters Live Drawings book on to Benedict.

https://twitter.com/shaunusher/status/1533504833382137858?s=21&t=7sfPsUgj4jnsJISco6zxBw

#letters live#hay festival#hay festival 2022#drawing#pencil#life drawing#benedict cumberbatch#joely richardson#elif shafak#jordan stephens#nina sosanya#louise brealey#lyse doucet#ardal o'hanlon#vera graziadei#toby jones#sir ian rankin#simon schama#shaun usher

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

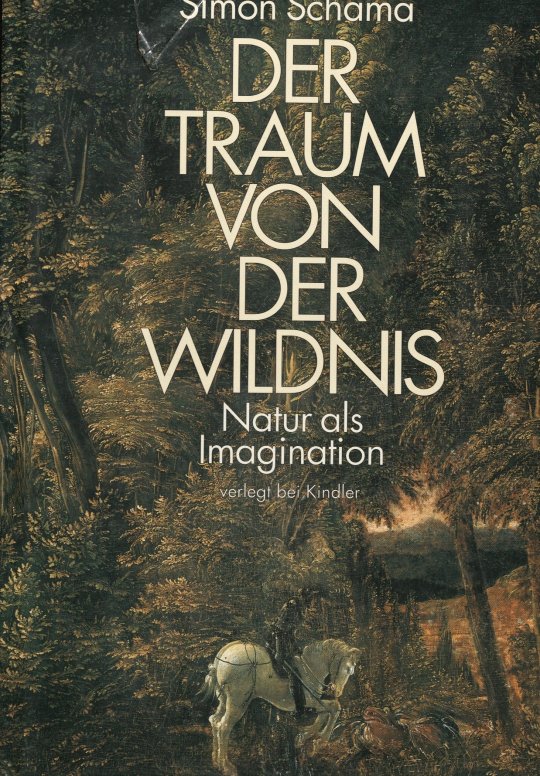

im reich des litauischen wisents - sterblichkeit, unsterblichkeit, s. 74-89 pdf

blutströme - weißfisch: eine politische theorie, s. 381-392 pdf

#landscape and memory#der traum von der wildnis#natur als imagination#simon schama#1995#kindler#1996#im reich des litauischen wisents#sterblichkeit unsterblichkeit#blutströme#weißfisch: eine politische theorie#albrecht altdorfer#drachenkampf des heiligen georg im laubwald#1510#fontainebleau#forest of fontainebleau#białowieża#białowieża forest#konstruktionen der landschaft#weißfisch#material#jva#plötzensee#books

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Peter Aspden:

“In 1973, the BBC broadcast an episode of The Ascent of Man, a series on the history of science written and presented by the academic Jacob Bronowski, a short scene from which is commonly considered to be among the greatest moments of British, or any other, television. The episode concerns the quest of scientists for absolute knowledge, and it ends with Bronowski walking slowly in the grounds of Auschwitz. In a single, unrehearsed take lasting more than two minutes, he walks towards a pond of rainwater, delivering his devastating account of what can happen when humankind “aspires to the knowledge of gods”. He pauses at the edge of the pond, and then steps into it, in shoes that are demonstrably not fit for purpose. He bends down and picks up a handful of mud, representing the ashes of the millions who died in the camps. “We have to close the distance between the push-button order and the human act,” he says as the film goes into slow-motion, and then finally a freeze-frame. “We have to touch people.”

I was reminded of the sequence watching the first episode of Simon Schama’s History of Now, as Schama stands on the Prague balcony where Václav Havel addressed the protesters of 1989’s Velvet Revolution. Not for any historical parallels, but for the way in which the presenter, visibly moved by his discussion of the subject, suddenly seems to go off-script and appears to improvise.

“Between us,” Schama says to the camera, no hint of irony, this really sounds like a private aside, “that is why I am so upset by what is happening right now with Ukraine.” He moves, as Bronowski does, from the particular to the general in his limpid conclusion: “We cannot afford the liquidation of democracy.” TV intellectuals are employed for the knowledge of their subject, and in an age of tin-pot posturing and huckster editorialising, that is welcome. But in both of these cases, it is the intellectual being moved by the very material that they are presenting that makes for such compelling viewing. Spontaneous outbursts of feeling are not uncommon in contemporary TV, but to see them come from those who have spent a lifetime on the measured accumulation of knowledge is rare, and riveting.

[thanks Scott Horton and FT]

#Peter Aspden#Scott Horton#Financial Times#BBC#The Ascent of Man#Jacob Bronowski#Simon Schama#articles#quotes

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

@globalworrierreturns: Shakespeare for every day of the year at Hay festival

Helena Bonham Carter, Allie Esiri, Tom Goodman- Hill, Jessica Raine, Tony Robinson, Simon Schama, Jordan Stephens, Samuel West and Olivia Williams ....so much fun!

#helena bonham carter#allie esiri#jessica raine#samuel west#tony robinson#tom goodman hill#simon schama#jordan stephens#olivia williams#appearances#2023#appearances: 2023#hay festival 2023

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This is the small stuff of common experience. But the Jewish story has been anything but commonplace. What the Jews have lived through, and somehow survived to tell the tale, has been the most intense version known to human history of adversities endured by other peoples as well; of a culture perennially resisting its annihilation, of remaking homes and habitats, writing the prose and the poetry of life, through a succession of uprootings and assaults. It is what makes this story at once particular and universal, the shared inheritance of Jews and non-Jews alike, an account of our common humanity. In all its splendour and wretchedness, repeated tribulation and infnite creativity, the tale set out in the pages which follow remains, in so many ways, one of the world's great wonders."

The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words 1000BC - 1492AD by Simon Schama

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simon Schama's Power of Art is one of my go-to shows when I'm having a hard time. It's so damn well made: spectacular imagery, great narration, the accompanying music always on point, and, of course, a quality analysis of history and art.

And also, some early appearances of Andrew Garfield as a model for Caravaggio and Andy Serkis giving it his everything as Van Gogh, eating his way through a tube of cadmium yellow.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

As you can see, I tried drawing the Simon Schama’s power of art but, perhaps I did a terrible job at that.... Yikes.....

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Forse, sostengono i critici più severi, tutta la storia della società stanziale (in contrapposizione a quella nomade), dai cinesi maniaci dell’irrigazione ai sumeri che lo erano altrettanto, è macchiata dalla brutale manipolazione della natura. Solo i cavernicoli del Paleolitico, i cui dipinti e graffiti testimoniano un rapporto con la natura di integrazione più che di dominio, sono esenti dal peccato originale della civiltà. Una volta distrutta l’antica cosmologia, secondo cui la Terra era sacra e l’uomo non era che un anello nella lunga catena della creazione, tutto finì, millennio più, millennio meno. L’antica Mesopotamia, a sua insaputa, ha prodotto l’effetto serra. Oggi, sostiene Max Oelschlaeger, uno di questi critici bellicosi, abbiamo bisogno di nuovi «miti della creazione» per riparare al danno perpretato dal nostro indiscriminato abuso meccanico della natura e restaurare l’equilibrio tra l’uomo e il resto degli organismi con i quali egli condivide il Pianeta.

Simon Schama, Paesaggio e memoria (1995)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great art has dreadful manners. The hushed reverence of the gallery can fool you into believing masterpieces are polite things, visions that soothe, charm and beguile, but actually they are thugs. Merciless and wily, the greatest paintings grab you in a headlock, rough up your composure and then proceed in short order to rearrange your sense of reality.

— Simon Schama

from The Power of Art

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Reading

Simon Schama

FOREIGN BODIES

Pandemics, Vaccines, and The Health of Nations

#Simon Schama#reading#vaccines#anti-vaxxers#COVID-19#pandemics#2023#willful ignorance#anti-intellectualism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Watching a respected historian hysterically reblog rafts of unverified or already-debunked stories of atrocities being committed against Israelis by evil Palestinian monsters while ignoring IDF atrocities perpetuated against Palestinian civilians, including children and doctors, is embarrassing.

You are a scholar, sir. You know better. Verify your sources before spreading bullshit.

0 notes

Text

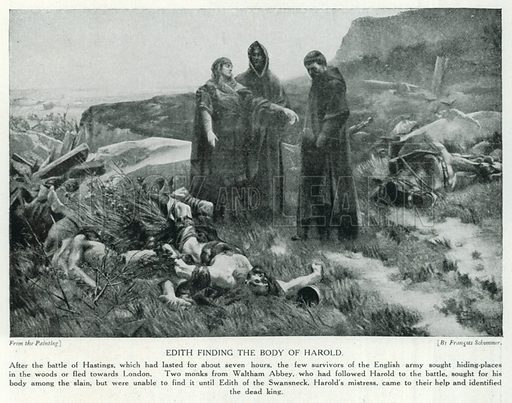

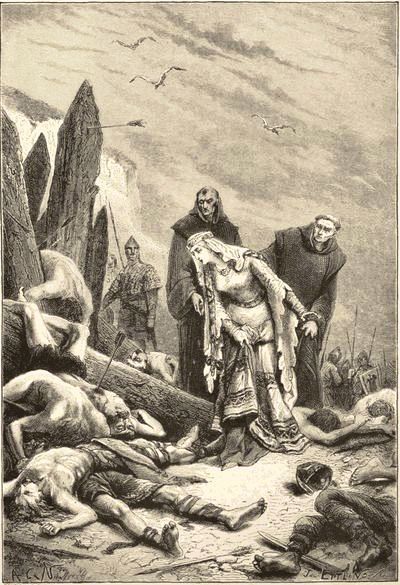

Edith Swanneck

I was listening to Simon Sharma's A History of Britain and went down an Edith Swanneck rabbit hole.

She kissed the brow, she kissed the lips,

Her arms about him pressed,

She kissed the deep wound blood-besmeared

Upon her monarch’s breast.

And at the shoulder looked she too —

And them she kissed contented —

Three little scars, joy-wounds her love In

Passion’s hour indented.

(Battlefield at Hastings, Heinrich Heine)

1 note

·

View note

Link

Hannah Weisfeld, the director of Yachad, a UK organisation that advocates for a political resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, said: “There is real disquiet in the community over Smotrich and Ben-Gvir. The settler attack on Hawara was quite a gamechanger.”

People, she said, were starting to understand there was “a connection between the undoing of democracy and settlers running wild in the West Bank.

“It’s very painful for British Jews, particularly those from an old-school Zionist background. Many have family in Israel who are telling them that a dictatorship is coming. We’re not quite at a tipping point yet, but I think we’ll get there.”

0 notes