#barcelona 1975

Text

Art and Language (collective created late 1960s)

Shouting Men (details)

1975

Screenprint and felt pen on paper

Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona collection

Photo: Àngela Gallego

© Art and Language via Artblart

#Art and Language#Shouting Men#1975#Screenprint#Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona collection#conceptual art#word art

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gatti rossi in un labirinto di vetro / Eyeball

Umberto Lenzi. 1975

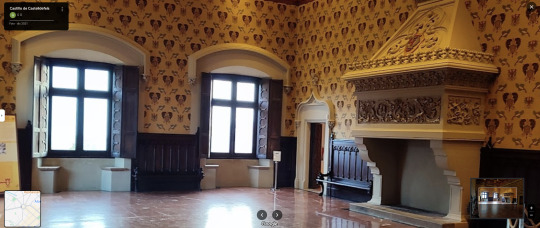

Castle

Plaça del castell, 1, 08860 Castelldefels, Barcelona, Spain

See in map

See in imdb

#umberto lenzi#gatti rossi in un labirinto di vetro#eyeball#martine brochard#ines pellegrini#castelldefels#baix llobregat#barcelona#catalonia#spain#castle#glove#red#eye#red gloves#movie#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#1975#giallo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'influenza del Bauhaus sul design

View On WordPress

#1975#ahşap#alan#algı#Barcelona#beton#beyaz#bilgi#bina#cam#dünya#eğitim#endüstriyel tasarım#estetik#etkileyici#Frank Lloyd Wright#Görsel#güç#ikonik#inşaat#konut#Kültürel#le corbusier#Londra#Mies Van der Rohe#Mimari#mimarlık#minimalizm#Miras#Mirası

1 note

·

View note

Text

8 febrero del 74: Las 3 AAA by j re crivello

“Nadie quiere hablar del pasado, pero se nos aparece para reclamarnos su cuota de responsabilidad” —j re crivello

«Lo que hace falta en la Argentina es un somatén» Juan Perón (en conversaciones con Oscar Bidegaín) (1)

La Triple AAA

¿Cómo ha ido? —Pregunto Lopecito.

—Esa periodista intento meterme en un lio —respondió el General ¡No le consentí! Decir que habíamos armado a grupos para que…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

8 febrero del 74: Las 3 AAA by j re crivello

“Nadie quiere hablar del pasado, pero se nos aparece para reclamarnos su cuota de responsabilidad” —j re crivello

«Lo que hace falta en la Argentina es un somatén» Juan Perón (en conversaciones con Oscar Bidegaín) (1)

La Triple AAA

¿Cómo ha ido? —Pregunto Lopecito.

—Esa periodista intento meterme en un lio —respondió el General ¡No le consentí! Decir que habíamos armado a grupos para que…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

a list of some summer movies/series 🌞

hi hi hi!! it's just me, your friendly neighbourhood little organisation freak of a goblin here to give you yet again a list of some seasonal movies and series. this time, say it with me folks, summer!

as always, just close your eyes and point somewhere on this little list, or even put the numbers in a generator and go with whatever the result is ♡

autumn | winter | spring

🐚 ‧₊˚ ⋅ movies ⋅˚₊‧

roman holiday (1953)

jaws (1975)

friday the 13th (1980)

Indiana jones (1981-)

dirty dancing (1987)

the princess bride (1987)

paris is burning (1990)

point break (1991)

jurassic park (1993-)

before sunrise (1995)

a goofy movie (1995)

clueless (1995)

birdcage (1996)

boogie nights (1997)

i know what you did last summer (1997)

my best friend's wedding (1997)

parent trap (1998)

bilboard dad (1998)

tarzan (1999)

the talented mr. ripley (1999)

10 things I hate about you (1999)

the mummy (1999)

cast away (2000)

almost famous (2000)

our lips are sealed (2000)

charlie’s angels (2000 + 2003)

holiday in the sun (2001)

the wedding planner (2001)

the fast and furious franchise (2001-)

princess diaries (2001-2004)

lilo and stitch (2002)

blue crush (2002)

crossroads (2002)

how to lose a guy in 10 days (2003)

under the tuscan sun (2003)

the lizzie mcguire movie (2003)

pirates of the caribbean franchise (2003-2017)

sisterhood of the traveling pants (2005-2008)

monster in law (2005)

aquamarine (2006)

she’s the man (2006)

the cheetah girls 2 (2006)

high school musical 2 (2007)

camp rock (2008)

vicky cristina barcelona (2008)

fool's gold (2008)

mamma mia (2008 + 2018)

adventureland (2009)

bride wars (2009)

hannah montana the movie (2009)

the last song (2010)

letters to juliet (2010)

eat pray love (2010)

one day (2011+2024)

a little bit of heaven (2011)

soul surfer (2011)

the impossible (2012)

magic mike (2012+2025+2023)

the big wedding (2013)

lovelace (2013)

endless love (2014)

chef (2014)

the longest ride (2015)

mad max: fury road (2015)

the shallows (2016)

it (2017)

girls trip (2017)

baywatch (2017)

jumanji: welcome to the jungle (2017)

gifted (2017)

call me by your name (2017)

crazy rich asians (2018)

adrift (2018)

ibiza (2018)

every day (2018)

bad times at the el royale (2018)

tomb raider (2018)

the red sea diving resort (2019)

midsommar (2019)

we summon the darkness (2019)

spider-man: far from home (2019)

the devil all the time (2020)

palm springs (2020)

the last letter from your lover (2021)

raya and the last dragon (2021)

luca (2021)

uncharted (2022)

glass onion (2022)

do revenge (2022)

the lost city (2022)

the gray man (2022)

death on the nile (2022)

barbie (2023)

bottoms (2023)

anyone but you (2023)

la passion de dodin bouffant (2023)

road house (2024)

the challengers (2024)

players (2024)

twisters (2024)

🍦 ‧₊˚ ⋅ series ⋅˚₊‧

the o.c. (2003-2007)

america's next top model (2003-2018)

project runway (2004-)

h2o: just add water (2006-2010)

gossip girl (2007-2012)

private practice (2007-2013)

rupaul’s drag race (2009-)

the walking dead (2010-2022)

new girl (2011-2018)

the fosters (2013-2018)

black-ish (2014-2022)

jane the virgin (2014-2019)

grace and frankie (2015-2022)

critical role (2015-)

stranger things (2016-)

the durrells (2016-2019)

big little lies (2017-2019)

she's gotta have it (2017-2019)

the bold type (2017-2021)

queer eye (2018-)

station 19 (2018-2024)

euphoria (2019-)

roswell, new mexico (2019-2022)

valeria (2020-2023)

911: lone star (2020-)

outer banks (2020-)

bridgerton (2020-)

sex/life (2021-2023)

the white lotus (2021-2025)

daisy jones and the six (2023)

#lea speaks#• comfort if you need it •#movies#comfort movies#movie recommendation#studyblr#cottagecore#dark academia#cozycore#cosycore#hygge#naturecore#tv show recommendations#summer#summer vibes#summer movies#summer aesthetic#summercore#mermaidcore#beachcore

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

I ran a series of polls awhile ago wrt the best Queen song other than "Bohemian Rhapsody." The winner was "Don't Stop Me Now," which is one of my all-time favorites. Buuuut I was listening to a different song and suddenly wondered:

“The Show Must Go On”: https://youtu.be/huc7IL7b8S8

“Who Wants to Live Forever”: https://youtu.be/_Jtpf8N5IDE

“Barcelona”: https://youtu.be/Y1fiOJDXA-E

"'39": https://youtu.be/kE8kGMfXaFU

"Teo Torriatte": https://youtu.be/Ge18n2JCwBs

"These Are the Days of Our Lives": https://youtu.be/oB4K0scMysc

"Love of My Life": https://youtu.be/lTr6dyjajKc

"Save Me": https://youtu.be/Iw3izcZd9zU?si=fOQvTU6rPZPtwpzL

“Ensueño”: https://youtu.be/e7XpSsYO2v4

“Under Pressure”: https://youtu.be/ZyT8mVwf_40

#anghraine babbles#poll nonsense#this is a queen appreciation blog#queen#my little piano: music is magic#music#narrowing it down to these was hard but someone's got to do it#i mean. i could have done tournament-style again but it would be too similar to the others imo

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

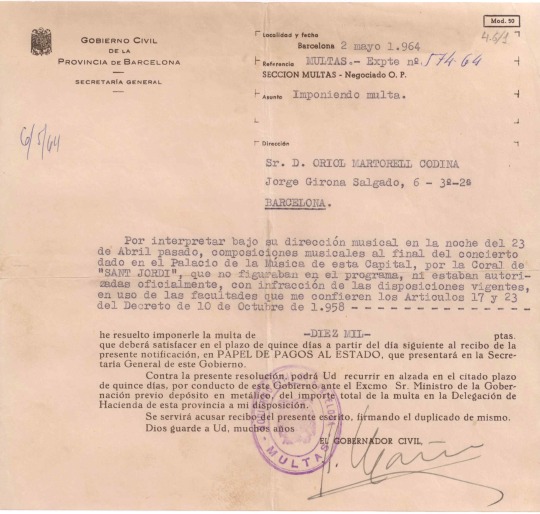

Fine that the Francoist dictatorship authorities made the director of Sant Jordi choir pay for having sung an unauthorized Catalan song on April 23rd 1964. This fine is kept as a historical document in the archive of the University of Barcelona.

General Francisco Franco's fascist dictatorship of Spain (1939-1975) banned and persecuted the use of the Catalan language for many years, allowing it towards the end of the dictatorship only in certain settings and under strict supervision of the police and censorship authorities. The dictatorship had the objective of eliminating the Catalan language, culture, and identity, and making all Catalan people become Spanish people. Cultural elements of Catalan culture were forbidden, such as certain songs, dances, and celebrations of traditional holidays, and people were imprisoned, tortured, and even sentenced to death for defending the right to exist of the Catalan people. The same persecution was suffered by the other nationalities under Spanish rule (mostly Basques and Galicians).

The choir Coral Sant Jordi, named after Catalonia's patron saint (Saint George), was founded in 1947 by Oriol Martorell. Its objective was to sing choir music with a focus on traditional Catalan music. The choir toured around Catalonia singing these songs with a great vocal quality, and became a symbol of cultural resistance against the dictatorship's attempt of ethnocide.

In the 1960s, the dictatorship wanted to become a normalized part of Europe and the international community. The regime opened Spain's borders to survive as a fascist stronghold, and thanks to the help from the USA (who was promoting fascist governments around the world), fascist Spain was accepted in the UN, normalized its relations with many countries, and opened its borders to tourism. To look more acceptable, it did some reforms among which they allowed speaking the local languages (Catalan, Aranese Occitan, Basque, Galician, etc) in public in some acts, as long as the person who was going to do it applied for official permission and turned in everything they were going to say or, in the case of a concert, the track list of all the songs that they were going to sing and all their lyrics as well as if they were going to speak between songs. The censorship authorities could accept or deny this application, and very often they censored parts of what was going to be said or sung, or whole songs.

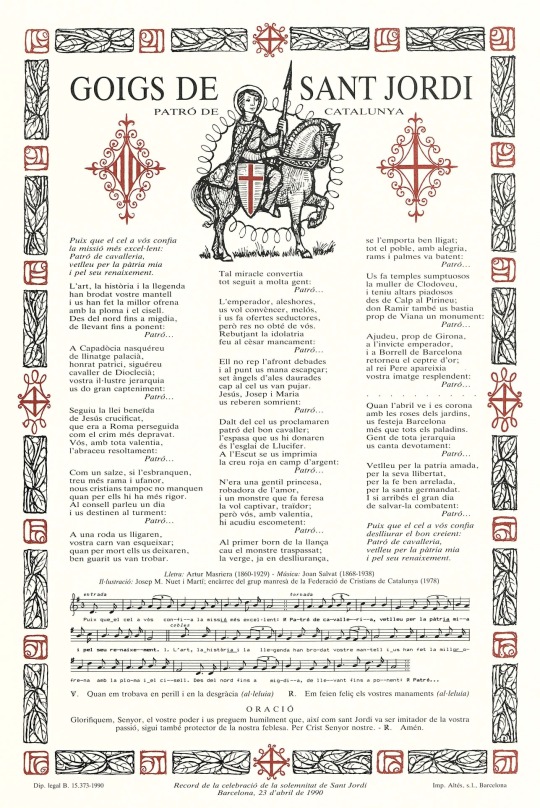

On April 23rd 1964, the choir Sant Jordi sang in a fundraising event to raise money for a church. Like all Catholic churches, this church is under the title of a saint, virgin, or similar. In this case, the church is dedicated to Saint George, who their choir is also named after. In the concert, the choir sang an extra song that wasn't on the tracklist that they had submitted to be approved by the censorship authorities. This extra song was the "Goigs de Sant Jordi" (goigs are a traditional Catalan music genre of songs dedicated to exalting a particular saint or Virgin). This is a goigs song composed in the year 1885 in the Catalan language, which explains the saint's story and asks: "patron of knighthood, watch over my homeland and for its rebirth".

For having sung this, the Spanish government made Oriol Martorell (conductor of the choir) pay a fine of 10,000 pesetas, a huge amount at the time. Oriol appealed the resolution many times, even reaching the Supreme Court, but as was expected they did not repeal it, and he (with support from the rest of the choir) had to pay the fine.

Under the cut I've included the whole lyrics of the unauthorized song translated to English.

This is a print of goigs song they sang. This one is from an act in 1990, kept in the archive of Jaume I University. These are the translated lyrics:

GOIGS OF SAINT GEORGE. Patron saint of Catalonia.

Since the heaven entrusted you

the most excellent mission:

Patron of knighthood,

watch over my homeland

and for its rebirth.

Art, history, and legend

have embroidered your mantle

and have given you the best offering

with the quill and the chisel.

From the north to the south,

from the east to the west:

Patron...

You were born in Cappadocia

of a palatial lineage,

honoured patrician, you were

Diocletian’s knight;

your illustrious hierarchy

gave you great demeanour:

Patron...

You follow the blessed law

of crucified Jesus,

which was persecuted in Rome

as the most depraved crime.

You, with all the courage,

resolutely embrace it:

Patron...

Like a willow, if it’s stripped off its branches,

it grows more branches and lushness,

new Christians aren’t missing either

when there’s more rigour for them.

One day you spoke in the council

and they destined you to torment:

Patron…

You were tied to a wheel,

your flesh teared out;

when they left you for dead,

they found you well healed.

Such a miracle soon converted

many people:

Patron…

The emperor, then,

wants to convince you, sweetly,

and gives you seductive offers,

but he doesn’t get anything from you.

Refusing idolatry

you defect the Caesar:

Patron…

He doesn’t receive the affront freely

and immediately orders you be beheaded;

seven gold-winged angels

take you up to heaven.

Jesus, Joseph, and Mary

welcome you smiling:

Patron…

Up in heaven they proclaim you

patron of the good knights;

the sword they gave you there

is Lucifer’s fright.

On your Shield was printed

the red cross on a silver field:

Patron…

There was a gentle princess,

stealer of love,

and a ferocious monster

wants to capture her, traitor;

but you, with bravery,

turn up to attack:

Patron…

On the first lance stroke

the monster falls down pierced;

the virgin, already released,

takes him away well tied up;

all the town, with happiness,

branches and palms beat:

Patron…

Clovis’s wife

builds sumptuous temples for you,

and you have pious altars

from Calp to the Pyrenees;

Sir Ramir also erected for you

a monument near Viana:

Patron…

You help, near Girona,

the undefeated emperor,

and you give back the golden sceptre

to Borrell of Barcelona;

your shining image

used to appear to king Peter:

Patron…

When April comes and is crowned

with the roses from the gardens,

Barcelona celebrates you

more than all the paladins.

People of all hierarchies

sings to you devoutly:

Patron…

Look over the loved homeland,

for its freedom,

for the well-rooted faith,

for the holy brotherhood.

And if the great day came

to save it in combat:

Patron of knighthood,

watch over my homeland

and for its rebirth.

Since the heaven entrusted you

to free the good believer:

Patron of knighthood,

watch over my homeland

and for its rebirth.

#història#arts#música#goigs#history#modern history#1960s#catalunya#catalonia#coses de la terra#francoism#music#choir#antifascism#singing#saint george#sant jordi#cultures#resistance#franquisme

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

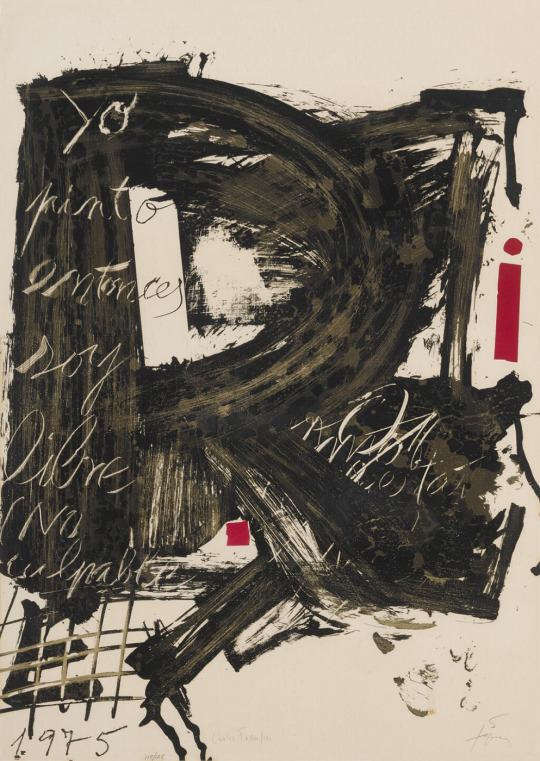

Antoni Tàpies, Poemas para mirar (Galfetti 537), (lithograph), Printed by Maeght, Paris, Published by Editart, Orlando et Dolorès Blanco, Genève, 1975, Edition of 125 [© Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona]

#art#mixed media#visual writing#lithograph#antoni tàpies#galerie maeght#editart#fundació antoni tàpies#1970s

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brunswick Centre, Bloomsbury, London, Patrick Hodgkinson, 1972

THE PASSENGER (1975)

In this clip from Michelangelo Antonioni’s globe-trotting thriller, Jack Nicholson strolls through Hodgkinson's mixed use Brutalist development. Antonioni’s architectural background is evident in this film, particularly in the scenes which take place in Barcelona, in which several buildings by Antoni Gaudi feature.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walden 7, Ricardo Bofill, 1975, Barcelona, ES

4/2023

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

SANTI HERNÁNDEZ: A Spaniard in Rossi's Court

Santiago Hernández Alcaraz, born in Barcelona in 1975, has witnessed an irresistible offer passing before his eyes. A perfect stranger to television viewers and motorcycle racing fans. But within the paddock, he has been one of Valentino Rossi’s trusted men during this season. Santi, Showa suspension technician with HRC and Valentino, has declined the offer made by the Italian genius to join the Yamaha team.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interior con lámpara, 1965

Emilio Grau Sala, (Barcelona, 1911 - Sitges, 1975)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

La influencia de la Bauhaus en el diseño

View On WordPress

#1975#alan#algı#Art#Barcelona#bina#cam#eğitim#endüstriyel tasarım#estetik#ev#Frank Lloyd Wright#ikonik#inşaat#konut#le corbusier#Mies Van der Rohe#Mimari#mimarlık#minimalizm#Miras#modern#sanat#şık#su#sürdürülebilir#tasarım#teknoloji#uzun#yapı

0 notes

Text

On August 6th, 1936, Josep Sunyol made a mistake that cost him his life. The Republican president of FC Barcelona, a proud Catalan, was executed by Nationalist forces in the midst of the Spanish Civil War, after saluting troops he mistakenly identified as part of the Republican resistance by yelling, “Viva la República,” (Camino, 2014). The assassination of Sunyol symbolized the beginning of an oppressive era where regional cultures were restrained in Spain, particularly the autonomous community of Catalonia. The most publicly admired and respected representation of Catalanism, Futbol Club Barcelona, colloquially known as Barça, faced countless hardships during the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco from 1939 to 1975. The club rapidly became one of the only ways the Catalan people could freely express themselves and fight against Franco, especially by playing the team that became the face of the regime, Real Madrid. In the present day, Barça continues to symbolize hope and freedom for Catalonians. Amid the rise of Francoist Spain in the mid-1900s, escalating tensions between Catalan club FC Barcelona and centralist Real Madrid transformed their rivalry into a political product representing the struggles of the Catalan people, illustrating how football transcends the limits of sport to reach social and political issues, particularly through the ambience of stadiums.

Throughout Spain, football stadiums became an essential place of solace for oppressed fans, where they were free to speak out on the issues that plagued their lives. People could openly express their identities in the stands, as matches between teams of different regions often represented a conflict larger than the game itself. One example of Catalonians using football for this purpose dates back to the pre-Franco era, when “the Spanish national anthem was played to a chorus of boos before a match at Les Corts, FC Barcelona’s stadium in 1925” (O’Brien, 2013). Even prior to Catalonians being officially repressed under Franco, it was clear that they valued their regional identity more strongly than their national one.

As the dictatorship grew stronger, regional teams like FC Barcelona faced the brunt of the nationalist policies. In promoting a unified Spain, the regime heavily cracked down on aspects of localized culture. The Catalan language, in all forms, was banned in public, and only Castilian Spanish was permitted (Shobe, 2008). An order passed in 1941 required that the Catalan name of “Futbol Club Barcelona” be renamed to the Spanish “Club de Fútbol de Barcelona” (Kassimeris, 2012). The Catalan senyera flag was also banned, and so the senyera in FC Barcelona’s coat of arms was replaced with the newly created flag representing the fascist state (Shobe 2008). Under the severe Castilization of their environment, the people of Catalonia were being stripped of their identities right in front of their eyes. With essentially no power, the Catalan people “threw their cultural pride into Barça. At a Barça match, people could shout in Catalan and sing traditional songs when they could do it nowhere else” (Shobe, 2008). Inside the stadium was where it was openly acceptable to oppose the restrictions of the regime and where liberation felt most realistic.

On the other side of the country, Real Madrid was thriving as the favorite club of the regime. Franco believed the Spanish national team was not gaining enough traction internationally, as they did not qualify for the World Cup multiple times in a row and performed poorly the years they did. Fortunately for him, “the image of the Spanish national team was blurred by the prevalence and success of Real Madrid in European Football from 1956,” effectively thrusting the club into the international spotlight (Goig, 2007). Real Madrid won five consecutive European Cups from 1956 to 1960, and their recognition both in and out of Spain surged with each victory (Quiroga, 2015). The relationship between the team and the regime was undoubtedly symbiotic. Real Madrid portrayed a positive image of the dictatorship to international audiences, while Franco gave them his full-fledged support and funds. In the 1960s, as television ownership grew across the country, Real Madrid was the most broadcasted team (O’Brien, 2013). The increased public exposure to the club acted as justification for the actions of the fascist regime, because people started paying more attention to football than to the government. Supporters of Real Madrid, known as madridistas, had no idea what was happening politically behind closed doors, nor did they seem to care.

The matches between FC Barcelona and Real Madrid, termed el clásico, were expectedly controversial. Spanish media outlets moved quickly to polarize the two sides, with newly-created “Marca” pushing for Real Madrid and the dictatorship, while “El Mundo Deportivo” supported FC Barcelona and ultimately the oppressed people of Catalonia (O’Brien, 2013). The politicization of the sporting rivals is seen best in a famed clásico played in June 1943, the second leg of a knockout round in the Spanish Cup. FC Barcelona had won the first game 3-0 and were on track to advance to the next round, until police officials entered the Catalan locker room before the game. Flash forward a few hours, and Real Madrid won the game with a score of 11 to 1 (Shobe, 2008). The interference by the Francoist police no doubt played a significant role in Barça losing so severely. While it is not known what exactly was told to the Barcelona players in the locker room, it can be inferred that they were threatened to purposefully lose the game, otherwise, they could lose their lives.

As the dictator fell ill, FC Barcelona worked to reverse the impacts of his policies and reclaim their Catalan identity. During the 1973-1974 season, they shed the Spanish name of “Club de Fútbol de Barcelona” and went back to the Catalan version it currently holds (Shobe, 2008). Additionally, in 1975, the club switched the official language back to Catalan, thus once again proudly representing the people of Catalonia (Quiroga, 2015). After Franco’s death, the effects of the regime collapsing were felt immediately in stadiums across the country. One clásico played just a month after Franco’s death in 1975 experienced the largest public emergence of senyera flags since the Civil War, and in Basque Country, a similarly tyrannized region of Spain, a game between two local teams “witnessed the spectacle of both captains carrying the Basque flag on to the pitch before the game” in early 1976 (O’Brien, 2013). Events that would have been inconceivable just months earlier were now reality, as stadiums reflected the transition back to a more accepting nation.

These bold representations of cultural unity at football games did not cease in the years after Franco. In fact, they have grown stronger in the 21st century. In the 2009 Spanish Cup final between Basque side Athletic Club de Bilbao and FC Barcelona, the crowd vehemently booed King Juan Carlos I and the Spanish national anthem before kickoff (Ortega, 2015). Decades later, supporters have not forgotten the unjust treatment they were put through and are still vocal about it during matches. A fan of Celta de Vigo, situated in once-repressed Galicia, proclaimed that “On going to a match we never forget Galician prisoners, repression, the secular subjection of Galicia... Spain limits the ways in which we can fight, so football is a way of voicing our demands” (Spaaij & Viñas, 2013). While fans of teams in marginalized regions use every opportunity they can to bring light to the maltreatment and discrimination of their pasts, for the most part, Real Madrid supporters do not follow the same path. In 2010, when Real Madrid beat FC Barcelona 1-0 in the Spanish Cup final, a large group of madridistas gathered in downtown Madrid, carrying Spanish flags while cheering “I’m a Spaniard, Spaniard, Spaniard” (Ortega, 2015). It is incredibly telling that in choosing to reaffirm their national identity rather than regional, madridistas see themselves as representing the entire country. As Franco’s Spanish Nationalist movement saw its triumph over Republican forces as a victory for Spain, madridistas still see a Real Madrid victory over a formerly oppressed team as a win for the whole nation.

In 2017, Catalonia became the forefront of global news as violence broke out amidst an independence referendum. On October 1st, the autonomous community conducted a vote regarding whether Catalonia should declare independence from the Kingdom of Spain, and the regional government announced that out of 2.25 million votes, about 90% were in favor of separating (Dewan, Clarke, & Cotovio, 2017). Unfortunately, the vote was heavily obstructed by the Madrid government. National forces were sent in from the capital, “fir[ing] rubber bullets at protesters and voters trying to take part in the referendum, and us[ing] batons to beat them back,” injuring around 900 people (Dewan et al., 2017). Predictably, FC Barcelona is often utilized to discuss and promote Catalonian independence, such as in 2010 when a banner declaring that “Catalonia is not Spain” was displayed during a game against English club Arsenal (O’Brien, 2013). When the central government began plans to thwart voting earlier in September of 2017, Barça decided to speak out. The club released a statement on Twitter, expressing that “FC Barcelona...remain[s] faithful to its historic commitment to the defense of the nation, to democracy, to freedom of speech, and to self-determination...FC Barcelona...will continue to support the will of the majority of Catalan people” (FC Barcelona, 2017). In openly showing support towards Catalan citizens’ voting rights and the independence referendum, Barça effectively bridges the gap between sports and politics. This is a two-way street: FC Barcelona stands up for their adherents, just as fans turn to the club to escape injustice time and time again. Coincidentally, Barça had a game scheduled the same day as the vote, which was played behind closed doors in order to eliminate the possibility of violence erupting in the crowd. The opposing team, Las Palmas, wore “special uniforms emblazoned with the Spanish flag,” something very out of the ordinary (Minder & Barry, 2017). Such a display could not tell a more pointed message.

The Franco dictatorship shaped the future of Spanish football forever, with Real Madrid and FC Barcelona at the forefront of the action. Real Madrid’s consistent success found them gaining the trust of the regime, which showcased the club’s victories as a positive interpretation of the fascist dictatorship itself. The desire of a unified, homogeneous Spanish state fueled regional tension, especially in Catalonia. Despite having their language and flag taken away, the Catalan people sought comfort in the stadium of FC Barcelona, where they could freely sing and speak and cheer for their team. In the decades after Franco, FC Barcelona has captivated audiences across Spain and the globe, cementing the club’s status as the most powerful cultural institution of Catalonia. “When the team took the field against FC Valencia in February 2012, nine players from the starting 11 emerged from the club’s Cantera System” (O’Brien, 2013), illustrating the importance Barça places on homegrown players. By providing unmatched talent bred exclusively in the club’s own youth academy, FC Barcelona is ensuring that they are conveying the best image of Catalanism to the rest of the world. As the Catalan struggle for independence continues, Barça was, is, and will continue to be a significant characteristic of the identities of millions of Catalonians. FC Barcelona represented hope in a time where its people needed it the most, and it is still the most influential institution in Catalonia to this day. The club and region are inextricably intertwined, as best seen in the passionate cheer: “Visca el Barça i visca Catalunya” - long live FC Barcelona and long live Catalonia.

References

Camino, M. (2014). ‘Red Fury’: Historical memory and Spanish football. Memory Studies,7(4), 500-512. doi:10.1177/1750698014531594

Dewan, A., Clarke, H., & Cotovio, V. (2017, October 02). Catalonia referendum: What just happened? CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/02/europe/catalonia- independence-referendum-explainer/index.html

Goig, R. L. (2007). Identity, nation‐state and football in Spain. the evolution of nationalist feelings in Spanish Football. Soccer & Society,9(1), 56-63. doi:10.1080/14660970701616738

FC Barcelona, @FCBarcelona. (20 September, 2017). Communique - Attached Image. [Twitter post]. Retrived from https://twitter.com/FCBarcelona/status/910462298908708864

Kassimeris, C. (2012). Franco, the popular game and ethnocentric conduct in modern Spanish football. Soccer & Society,13(4), 555-569. doi:10.1080/14660970.2012.677228

Minder, R., & Barry, E. (2017, October 01). Catalonia's Independence Vote Descends Into Chaos and Clashes. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/01/ world/europe/catalonia-independence-referendum.html

O’Brien, J. (2013). ‘El Clasico’ and the demise of tradition in Spanish club football: Perspectives on shifting patterns of cultural identity. Ethnicity and Race in Association Football, 25-40. doi:10.4324/9781315094304-3

Ortega, V. R. (2015). Soccer, nationalism and the media in contemporary Spanish society: La Roja, Real Madrid & FC Barcelona. Soccer & Society,17(4), 628-643. doi:10.1080/14660970.2015.1067793

Quiroga, A. (2015). Spanish Fury: Football and National Identities under Franco. European History Quarterly,45(3), 506-529. doi:10.1177/0265691415587686

Shobe, H. (2008). Place, identity and football: Catalonia, Catalanisme and Football Club Barcelona, 1899–1975. National Identities, 10(3), 329-343. doi:10.1080/14608940802249965

Spaaij, R., & Viñas, C. (2013). Political ideology and activism in football fan culture in Spain: A view from the far left. Soccer & Society, 14(2), 183-200. doi:10.1080/14660970.2013.776467

#just in case anyone forgot :)#fc barcelona#fcb#football#this is just one of my two or three essays on this topic lmfao#i think this is my most recent one from 2018 for my social and historical perspectives of sport class in 2nd year of undergrad#i miss when i used to fight people on here by just copy pasting paragraphs of this and the other papers. lol#that whole point about stadiums isn't really relevant to this particular incident/conversation (i think) and tbh idk why i included it#maybe one of the papers had some really good info about it that i couldn't ignore

75 notes

·

View notes

Video

BMW 3.0 CSL 1975 / Christophe VAN RIET / Matthieu de ROBIANO by Artes Max

Via Flickr:

ESPÍRITU DE MONTJUÏCH 2019 / Circuit de Barcelona

#clásico#histórico#classic#historic#racecar#coche#car#sports#racing#race#motor#motorsport#autosport#legends#nikon#retro#السيارات#車#Autos#coches#cars#automóviles#автомоб#BMW#3.0#CSL#1975#Christophe#VAN#RIET

119 notes

·

View notes