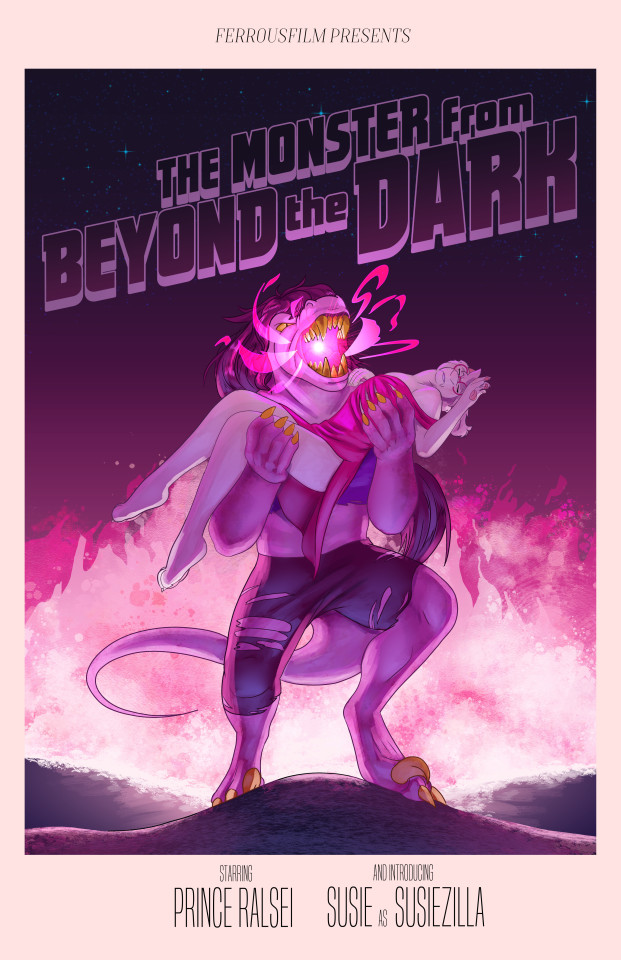

#but i loved this concept way to much not to attempt the painterly style of those classic b-movie posters

Photo

I promised to draw something for anyone who could identify the movie Susie and Ralsei are watching in the last couple pages of Looking Glasses. @bleakoutlo correctly identified The Monster that Challenged the World, and had the very good suggestion of doing my own B-movie poster, which I may have gone a little overboard on.

#looking glasses#deltarune#utdr#deltarune fanart#ralsei#susie deltarune#ralsusie#susiezilla#ferrousart#I was initially going to do something simpler so that I could spend more time working on other stuff#but i loved this concept way to much not to attempt the painterly style of those classic b-movie posters

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

without the sour the sweet wouldn’t taste

why are you as a man eating another man’s ear after you failed to make him eat his ex girlfriend. 🤨🏳️🌈⁉️

im allowed a bit of toxic yaoi. as a treat

process discussion utc ⬇️

for those familiar with my work you’ll know that i like trying a lot of new styles and experimenting in order to achieve a certain vibe. usually those are heavy painterly styles such as the sunday art inspired by Yuming Li, which is what i’m familiar and comfortable with, both traditionally and digitally

what im NOT familiar with is watercolour. i’ve never had a good time with it 🥲 i just cant seem to wrap my head around the process since its requires me to work backwards (light to dark vs dark to light)

for this piece i just couldn’t imagine myself rendering it in my usual style. i needed to do something new so that i’d stay invested enough in the piece considering that it has two people, meaning double the work. for some reason i thought it’d be fun to do double the work with a style i am completely uncomfortable with but oh well!! i managed to do it 🤷♀️ i was specifically looking at the works of Ko Byung Jun, an artist i’ve seen all over my pinterest feed

while i didn’t end up really following the style super closely i still learned quite a lot just by looking at it while i drew. i tried my best to stick to watercolour brushes and an ink pen but as i was nearing the end i needed to make some alterations that i wasn’t bothered to try fixing with the watercolour brushes so i just went over it with my digital ones 🫡 i did my best that’s what matters!!!

i had to repaint rody a few times cause i just couldn’t get it right and the colours never ended up matching vincent. i painted them separately and i think i got possessed while painting vincent cause it happened in like. 40 minutes. and i couldn’t get it to happen again 😔 it didn’t really matter cause i ended up going ham with the curves tool as always but you know 🤷♀️

here’s the image without all the effects:

i find lately it’s been more and more common for me to be sketching several iterations of a concept for days, even weeks before i land on something i like. i have an entire separate canvas that i’ve spent 5 hours just doing thumbnails trying to figure out how i wanted to pose these two in a way that would showcase the characteristics that mattered in the story of this piece.

that’s my process for coming up with drawings: i find inspiration somewhere, i figure out the key concepts/characteristics/symbols etc i want highlighted, and i work around those. sometimes i have a composition in mind or just a general vibe i want to portray. for this one i wanted to make sure the towel, rody’s injured finger and vincent’s face could all be clearly seen, while also portraying the fight scene and the vibe i get from the reference song. almost all of my work revolves around a specific lyric from the song which drives the story of the piece. here i interpreted the line “without the sour the sweet wouldn’t taste” as a connection to all the little actions vince takes with rody that can be seen as “sweet.” drying rody’s hair, bandaging rody’s cut. i then asked myself how i could take those actions and make them “sour” or show them in a different light, in which vince is biting the finger he bandaged and pulling rody closer, preventing his escape with the towel he used to dry his hair. what im trying to communicate in this illustration is the idea of “if it weren’t for how i’m treating you now, you wouldn’t understand how kind i was to you then” in an attempt to illustrate the complexities of the way vincent acts towards rody.

i’m truly in love with the story telling of this game. it’s hard to really say anything about how the characters acted during the story because it’s so complex in how it’s done. it’s very hard to summarize their relationship because there’s so much about it i can’t explain without just quoting the game directly. i think it’s such a beautiful portrayal of obsession and just being fucking weird about someone. i wanted to ensure the elements i mentioned in the above paragraph because i didn’t want to be portraying vincent as solely a villain and rody as a victim. i wanted the storytelling of this one illustration to live up to my impression of this beautiful game and i hope i did it justice.

thank you for reading this if you’ve made it this far. i love rambling on all my art posts cause i think it’s so valuable for artists to expand on their work outside of the result alone. i hope what im saying is at most helpful to someone and at the very least a good read. i’m probably gonna take a bit of an art break after this since it took a lot out of me, plus im on the last days of my trip. thank you again for reading!

here’s my dog

#my art#fanart#dead plate#dead plate vincent#dead plate rody#dead plate fanart#dead plate game#vincent charbonneau#rody lamoree#digital art#artists on tumblr#digital illustration

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snowman’s Favourite Games of 2017

It seems like we find ourselves saying it every December, but it really is true: this year was a spectacular one for games.

From inventive new entries in blockbuster series to deeply resonant games crafted by independent creators, and everything in between, we were constantly inspired by this industry’s talented creators.

As we reflect on all the great titles we had a chance to experience, some in particular continue to linger in our hearts and minds. Whether they made us laugh with delight, cry out in frustration, or in some cases just cry, these games were our favourite of 2017 (in no particular order).

What Remains of Edith Finch

In our Snowman Review of the game, we said, of Giant Sparrow’s masterpiece:

The deeper I dove, the more I was surprised by how resonant the whole experience was on a personal level. How despite getting lost inside it, the magical Finch house never lost its grip on me. How, underneath all of the Rube Golbergian mystery of it, What Remains of Edith Finch was ultimately a tale of loss, and of how we deal with it. Of finding perfection in our own fallibility, and the fallibility of the people we love. And maybe most of all, of forming the shape of our future out of more than the contours of our past.

Even as the year comes to a close, we constantly find ourselves bringing up Finch. Full of haunting, sometimes heart-wrenching vignettes, this is a game which is best experienced completely unspoiled. If you’ve yet to visit the Finch house, do yourself a favour and take a trip there as soon as possible.

TumbleSeed

On the surface TumbleSeed is a game about rolling a small seed up a big mountain. But in reality, TumbleSeed is so much more than that. It’s a game about learning to delight in intrinsic rewards. A game where the high score isn’t a point value, but the realization that you’ve become a more patient person — a person who deals better with small setbacks, who breathes deeper for a little longer before becoming agitated. TumbleSeed is a shining example of a game created with singular conviction. It’s an experience some players will bounce off of. But for those who stay, it’s that wonderful type of game which gets under your skin, and into your bones — always calling you back for one more try.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

The term “open-world” gets bandied around a lot for games with large maps, lots of quests, and long checklists of things to do. Breath of the Wild, however, is something altogether more brilliant. A game that presents the player with a massive playground full systemic interactions, and sets them loose to craft their own adventure. Climb to the top of a snow-capped mountain, use your shield to snowboard down, jump into the air above a camp full of enemies, and electrify them all by shooting a lightning-powered arrow into their tin cooking pot. Then go do a hundred other things you haven’t yet planned on your way to another mysterious peak in the distance. Breath of the Wild is a return to and revitalization of the sense of wonder that’s so central to the Zelda series. It’s a shining example of why Nintendo are such masters of their craft.

Gorogoa

There’s no other way to say it: Gorogoa is perfect in every conceivable way. It is a profound experience so clever that it’s actively hard to believe it exists as it’s happening. As a puzzle game, it’s a master class in how to teach people what to do as they do it, all while ensuring that nothing ever feels unfair or too far out of reach. But our advice when playing this - and you must immediately go play this if you have a couple hours to spare - is not to get too hung up on what type of game it is. Instead, enjoy getting lost in every resplendent, hand-drawn frame, as the game’s concept and story unfold before you one layer at a time.

Stagehand: A Reverse Platformer

Sometimes you stumble on a game whose concept is so elegant and intuitive that you wonder how it hasn’t been done before. Stagehand is one such gem. Part platformer, part runner, the game has you moving the landscape to guide intrepid hero Frank to safety amid a gaggle of classic obstacles like spikes and lava. Moment to moment, Stagehand is a constant delight with clever design, pixel-perfect art and nostalgia-inducing sound design. Developer Big Bucket Software continues to impress as a creator of modern classics for phones and tablets.

Cuphead

Much has been made of Studio MDHR’s seven-year journey to bring Cuphead to life, and playing it, you can instantly see why. The game is a Silly Symphony in your hands: a playable Fleischer-era cartoon that leaps off the screen and into your heart. It’s almost impossible not to root for the adorable Cuphead and Mugman as they run and gun their way through inventive boss battles to earn their soul back from the devil. We say almost, because the game’s brutal retro difficulty might just have you throwing your controller. Good luck!

Old Man’s Journey

In our review of the game earlier this year, Snowman founder Ryan Cash sums up why this game is such a treasure:

So much of the [game’s] emotional journey is wrapped up in the beautiful art style — the pastel colours flowing around the screen in wisps. Subtle animations pepper the painterly flashbacks of the main character, stirring up wistfulness and nostalgia. A children’s storybook with an adult heart, brought to life...Truly, the title of the game says it all. Life can pass us by so quickly, and this game was a beautiful reminder of that. A chance to pause, and do something we often forget to do — reflect.

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy

In the trailer for Getting Over It, the game’s creator Bennett Foddy says that he created it “for a certain type of person...to hurt them.” This game, about ascending a massive mountain as a man stuck inside a pot using an axe, more than lives up to Foddy’s aspirations. There are no checkpoints, the landscape is deliberately designed to rebuff attempts to find clear patterns in movement, and nearly any misstep can result in tumbling all the way to the very bottom. Why then, does it make our list? Because there’s something intoxicating about the oft-unexplored feeling of friction and frustration that Getting Over It captures. Of all the games on this list, it’s perhaps the most fun to play with a group of friends, delighting in one another’s misery, and - somewhat inexplicably - your own.

Monument Valley 2

We’d be remiss not to include ustwo Games’ followup to the gorgeous Monument Valley. This second kaleidoscopic journey into the world of sacred geometry continues the series trend of taking your breath away in every shot. This is the the type of game that makes the devices you play it on feel more beautiful — any isolated shot could be a painting hung on your wall. This time around, take particular note of the transcendent, transportive sound and music from artist Todd Baker.

Super Mario Odyssey

It may seem biased because we have our own Odyssey title on the horizon, but we promise: this game is spectacular. In a series known for its tight controls and balletic movement, Super Mario Odyssey is a crowning achievement. A game where every hop, skip, and jump is so responsive it will put a smile on your face, and where the rewards for mastering the controls feel nearly endless. Speaking of endless: this is the kind of game you hibernate with. Every nook and cranny of its bright, ebullient world is filled with secrets and treasures to find, so make sure to keep playing even after Bowser’s been defeated.

Perhaps the greatest shame of all is that for every game mentioned on this list, there are probably three that we’ve forgotten or which we didn’t even get a chance to play. Then again, that will just make discovering them later all the more joyful.

Here’s to a 2018 that’s even half as filled with amazing experiences as this year was – a few them even from yours truly.

#game of the year#best games 2017#listicle#builtbysnowman#what remains of edith finch#super mario odyssey#breath of the wild#monument valley 2#monumentfriends

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film, music, and painting: Inter-medial relationships in Kurosawa’s “Dreams” (episode Crows)

“A love of cinema desires only cinema, whereas passion is excessive: it wants cinema but it also wants cinema to become something else, it even longs for the horizon where cinema risks being absorbed by dint of metamorphosis, it opens up its focus onto the unknown.”

—Serge Daney: The Godard Paradox. In: Michael Temple, James S. Williams and Michael Witt (eds.): Forever Godard. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2004, 68. (Petho, 2011).

Introduction

When Akira Kurosawa suggested Van Gogh’s paintings in a movie “Dreams” it was not only a tribute to the great painter’s work or expressions of his perceptions. Here the key question is what kind of methods or ways he used to express the narrative. He represented it in a way which allows spectators to choose different perspectives through which they will experience his work. I think the perspective I have chosen to observe the film will give me a key to go further and deeper into the case, however, this paper does not claim that this perspective is one and only through which the movie should be investigated. To provide more thoughtful analysis I will try to explore the relevance of the term Intermediality to the artwork I have been observing. And besides, I will try to analyze artwork through several theoretician’s theories and concepts. This paper will also provide further insight through intermedial lens how the narrative is expressed with the help of paintings and painterly techniques in the particular episode Crows. My work also emphasizes the question of three media relationships, how they influence each other and cross boundaries; how does this method operate on our senses. I have chosen the topic because on the one hand, we can still experience every mono-media but on the other hand, an intermedial product is more manipulative on our senses and thus more immersive by using the whole emotional potential without asking. Hence, it is obvious that we are already on the other side of transformation. The movie style itself and other aesthetic features prove that this artwork is different from its historical past and thus remains worthy of discussion.

As Carol Vernallis admits, nowadays, Intermedial movies are differently constructed and fewer meet the criteria of David Bordwell and Krisin Tompson. Their work Film Art: An introduction: assumes that all of the events we see or hear are arranged in a chronological order, duration, frequency and spatial locations. The tale is not constructed in that way in the majority of intermedial movies (Vernallis, 2004), one of the examples is the movie I am discussing in this paper. Technological reproduction is kind of a mass movement of our day, says Walter Benjamin and their powerful agent is a film. For him, a film is the first art form whose artistic character is entirely determined by its reproducibility (Benjamin, 2008). One of the characteristics of the intermedial product is that while watching or experiencing it our perceptions, cognition, and bodies emerge in one angle and the value of senses is getting more important as they explore the aesthetic dimensions (Engberg, 2013).

Exploring the concept

The concept of Intermediality is one of the most challenging concepts in media theory. “Scholars have been debating for centuries about the relationship of the arts” (Ellestrom, 2010, p.11). It is impossible to write everything in two lines, but I will try to depict its meaning in several sentences as it has a lot of angles. “Inter” is focused on the relationship, rather than structures that happen “in-between” media (Petho, 2011). This term is quite different from media convergence as it is defined as social and cultural relationships among different media while convergence emphasizes gaps between old and new media (Herkman, 2012). The idea and a concept Intertextuality is also influential here. The fact that individual works engage in constant dialogue with other texts is kind of a philosophical starting point for the following discussion. As Miguel Mera writes in her article, terms such as remake, translation, re-invention, imitation, palimpsest, revision are very appropriate and all of them refer to intertextuality as well as intermediality. This term in its own sense is based on this concept of intertextuality. Simply, as every new text is re-invented from another previous one so is an intermedial object. Ellestrom writes that intermedial studies have much in common with aesthetics, philosophy, semiotics, comparative literature, interart studies and so on (Ellestrom, 2010). So Intermediality is kind of a relationship among different arts.

About the film “Dreams”

If we read Akira Kurosawa’s book Something like an autobiography, we will find out the main events or histories which stimulated or determined his whole professional life. He was a Japanese director and a painter (Kurosawa, 1967) and his combined knowledge are perfectly reflected in his movies. The movie Dreams is not an exception.

As a starting point, I want to remind the classical theory of film by David Bordwell and Krisin Tompson that the movie is constructed by causal effects, duration and so on (Vernallis, 2004). However, the movie Dreams does not have a single narrative, but it is independently episodic, constructed with eight dreams that the film director has had throughout his lifetime repeatedly (Kurosawa, 1967). Kurosawa also defined the meaning of the cinema in his autobiographical work so that it is a resemble of many other arts and its literary features allow us to say that it has theoretical and philosophical sides, degrees which attribute painting, sculpture and music elements (Kurosawa, 1967).

The first four episodes which are also considered as moral tales come from mythological motives, for example, the first episode Sunshine through the rain emphasizes the mythological Kitsune – the spirits who are enigmatic souls in Japanese mythology. The second part the peach orchard – underlines the tradition related to peach trees and dolls (Heinzekehr, 2012). So are the rest two. The following four episodes are demythologized which provide the idea that western civilization encroaches into an Eastern world with its whole force and it makes the end clearly apocalyptic (Heinzekehr, 2012). The specificity of this independent narrative is that it allows a spectator to experience only one episode and get the main point of a concrete dream. Though while witnessing the whole movie with all episodes we feel that each tale responses each other and all dreams merge or cross somewhere in our head so that we get a complete idea. Another characteristic which differentiates this movie from others is its beautifully photographed visual effect and the impression that every shot is a fascinating painting.

My research questions refer to the fourth episode Crows more than others. This episode represents a student who is standing in front of the painting of Wheat Field with Crows painted by Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh, in a minute later he finds himself inside the various colored paintings. He also meets the famous painter and has a conversation with him. From now on the spectator is in its way of experiencing a very strange phenomenon which was not common in a film or in mono-media history before. The film director attempts to convey the painting realm into the movie realm. And we recognize that this is not a traditional way of film construction but already the relationship between two media, a film and a painting which cross the borders of the painting and the film studies at the same time.

How boundaries are crossing – painting, melody, and filmmaking

If we stay in Mera’s perspective, there is no need of thinking which was the chronological successor in the case of Crows - a painting or a film. Paintings were re-invented in the film. I think we should provide some distinction between these two media. There are some studies which provide further investigation how film as a phenomenon differs from the meaning of a painting. In painting, the way from reality to the picture lies via the artist’s eyes and nervous system, his hand and the brush that puts strokes on canvas, however, the film does nothing but reproduce reality mechanically (Arnheim, 1933, p.312, Benjamin, 2008). Benjamin compares a camera operator and a painter. It more looks like a comparison between a surgeon and a magician. The painter maintains the distance from the reality just like a magician and the cinematographer as a surgeon goes deeply into the reality (Benjamin, 2008). But Kurosawa as a painter and a cinematographer at the same time combines paintings with the real nature successfully and represents this emergence in a very professional way.

From this point of view, it is necessary to distinguish whether this transmission in the episode Crows is translation, adaptation, remake, imitation or whatever. The terminological difficulties arise here which leads us to boundary crossing difficulties as well. On the one hand, it is more appropriate to think that the canvas is remade into the movie as it shot-by-shot is identical of the paintings and on the other hand, it is still very fuzzy. I can claim that Kurosawa does not lose or change anything in the paintings itself, while we have total changes in other cases. For example, if we want to transmit a novel or a book into a film we need to forget the concept of ‘exact imitation’ because it is impossible as these two media have nothing in common and if we still attempt, it will be a failure. But here we see that Van Gogh’s work are obviously and exactly the same in this episode as they are in the gallery. Nothing is changed in their reproduction except one thing non-moving, stable image is now considered as moving which also indicates the real movable nature, the people are acting inside and these effects are achieved through montage techniques. Here we face to boundaries’ crossing of montage sequence and painterly techniques. At a glance, they have nothing in common, a brush does not look like a lens at all, but still they are positively correlated. From the point of view of Walter Benjamin, for example, to photograph a painting is one kind of reproduction but the act of producing is not an artwork. The cameraman does not create an artwork but an artistic performance. In a film case, the work of art is produced only by means of montage (Benjamin, 2008). We can say that Kurosawa produced the artwork through the montage technique. “Each individual component of this montage is a reproduction of a process” (Benjamin, 2008, p.29). So we might say that the episode introduces the painterly techniques as a reproduced art through montage sequence and shooting. This reproduction is exact, following all painterly rules respectfully. The spectators watch very visible brush strokes, recognize the specific style which creates a real sense that this is a canvas. Sometimes shots are zoomed in so that the spectator can understand the nature of paintings, how nervously and roughly these strokes are painted, how these textures respond to the reality and the real nature, how colors dominate and blend in each other. It conveys a real temper and the episode fully demonstrates the paint medium and its meaningful energy. With help of a montage technique, it is already a great observation and you might not need to go to the gallery and look at the painting because this is more than you will experience there. And more than you will get from the pure painting. It is also worth noting that the painting is available only for a few audiences, Kurosawa’s passion was a simultaneous viewing of paintings by a large audience while “painting by its nature cannot provide a collective reception as the film is able to do” (Benjamin, 2008). We can find a plenty of key sentences here which emphasizes the relationship with the reality and a painting as well. In the episode, Van Gogh’s character says that “the scene which looks like a painting already will never be painted”. Thus, the reality and painting have positive interrelation with each other. Moreover, at the end of this episode we see flying crows in the real environment and then, all of a sudden, it becomes into a painting hanging in the museum. So Kurosawa clearly claims that the real nature cannot be painted because in its own sense it is already a unique painting. As from the other discourse, for example, Gotthold Lessing would say that these two media do not have the same spatial-temporal characteristics as one of it is temporal and another spatial but it is not doubtful that he would need to think differently in the era of Interarts and in-between relationships (Lessing, 1968).

One additional point which makes it more complex is that the episode also includes the composition - Prelude N.15 composed by Chopin. So here are sound and paintings and their interaction. The composition is also perfectly fitted for this episode it is modified so that it provokes different emotions than it would provoke while listening to pure melody or accompanied by another visual background. The use of music in this episode is worth discussing because sounds can shape or influence audiences. As Stilwell argues spectacle is strongly associated with music in a film, as the camera lingers on complex visuals, music seems to be vital providing some sort of lightness for the audience (Mera, 2009). It re-shapes the audience’s perception. The role of music is fundamental in establishing the world of the film (Mera, 2009). In this case, Chopin and his music was not only re-invented but was also a brilliantly accompanied with every scene and action. For example, the moment when Van Gogh paints in the middle of the field the music rises to express its psychological disorder while painting. Like a locomotive, Van Gogh’s mental state also accelerates, as he feels pressured to create art in his limited life (Reider, 2005). Or another fragment when the student ran down through the leading path of the painting. The music demonstratively indicates the rough strokes on canvas painted by brush. It helps the audience to feel the action. The following discussion will elaborate this question why the audience is involved or experience this more deeply.

Intermedial work and audience perception

Marshall McLuhan argued that media were all extensions of human senses and physical abilities. For McLuhan, this multi-sensory is connected with ‘electric age’ and the ultimate medium which provokes all senses at once particularly was a television (Engberg, 2013). McLuhan in his book understanding media, the extensions of man assumes that we have already extended our senses and our nerves by the various media and any extension, whether of skin, hand or foot affects the whole psychic and social complex (McLuhan, p.2) Consequently, while witnessing this movie on the screen spectators are involved with their multiple senses. That is the reason why the audience gets more sensible. Walter Benjamin writes that new reproductive media of photography and film did not stay in auratic qualities of painting and therefore changed the sense perception of its viewers (Engberg, 2013). He also claimed that human mode of perception changed over time. People’s perception in the era of their migration was different from the perception of the late-Roman art industry for example (Benjamin, 2008). This is a very important claim which gives me a clue to say that intermedial or reproduced art requires or provokes different kind of perception or sense mobilization because we are in a particular nature of an (intermedial) culture as well as in a particular period of the history. Moreover, this work as the intermedial work requires more attention or high intellectual or aesthetic levels from the audience because its understanding depends on the interplay between works: the painting, composition, and film. “Furthermore, it seems that intermediality has also the potential of becoming one of the major theoretical issues of contemporary thinking about cinema, precisely because it regards film to be a medium in continuous change and interchange” (Petho, 2011, p.1) For getting the maximum degree of a pleasure it is necessary at least to know who was Van Gogh and be a bit familiar with his paintings or biography as well as its relationship to the rest episodes. It was not accidental that Kurosawa chose Van Gogh and his painted world. The reason comes from mount Fuji and a Japanese painter Hokusai. The views of Mount Fuji, the holy mountain, must have been appealing to van Gogh. He writes to his brother Theo that he should ‘be sure to take the 300 Hokusai views of the holy mountain’ (Van Gogh 1959: 611, Reider, 2005). This part is kind of a reference to the next dreams. So it is constructed with lots of references and requires pre-knowledge to experience it. While we are listening to Chopin’s melody and watching the moving paintings through a film we turn on the other side of perception.

Conclusion

As to conclude, I have tried to analyze the episode Crows and explore it through theories of intermediality. Boundaries of the individual arts were always sharply determined, but today it is noticeable that they might have a relationship with each other without losing its real appearance or auratic qualities. On the one hand, this tendency legitimates us to think that the borders are not as sharp as it was before in the past. On the other hand, it gets still puzzling as soon as we think about other media transmission - it becomes harder if we are dealing with a novel to make it into a film. It is so because some media may be perceived as more border-crossing than others (Ellestrom, 2010, p.4). So while discussing some media crossing everyone should take into account to discuss every mono-media separately for the first time and then think about their crossing. This paper also tried to prove, that we experience Van Gogh’s painting more from this movie than from the ‘pure’ paintings because of the multimodality (Ellestrom, 2010) of this artwork which combines our senses and enhances one’s perception. It is also obvious that it requires kind of a pre-knowledge to get a maximum pleasure from it.

This paper will not be provided with the discussion about influences of Japanese poetry, principles of classical Japanese literature or performing art (Reider, 2005). Also was not provided with the discussion about originality or authenticity which might be an arguable and interesting issue for this episode as we are watching a reproduction. Further, it would be an interesting starting point if we raise the question of temporality or spatiality in the artworks mentioned above. This case would brilliantly depict Lessing’s or Mitchell’s systematic discourses in a meaningful way. The case requires very deep insight as the degree of spatiality and temporality varies in every mono-media (Reminding the spectrum of arts) and this imbalance makes it even harder to investigate border crossings between painting, melody, and film (Lessing, 1968, Mitchell, 1984).

Reference List:

(n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3OTj5Qv153U

(n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwDkpnH-zek

Arnheim, R. (1933). Film and Reality. In R. Arnheim, From Film as Art (pp. 312-321).

Benjamin, W. (2008). The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological. In W. Benjamin, The Production, Reproduction, and Reception (pp. 19-55). United States of America: President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved from https://monoskop.org/images/6/6d/Benjamin_Walter_1936_2008_The_Work_of_Art_in_the_Age_of_Its_Technological_Reproducibility_Second_Version.pdf

Ellestrom, L. (2010). Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Engberg, M. (2013). Performing Apps Touch and Gesture as Aesthetic Experiece. A Journal of the Performing Arts, 20-27.

Heinzekehr, J. (2012). The Reenchantment of Eschatology: Religious Secular Apocalypse in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams. Journal of Religion and Film, 1-20.

Herkman, J. (2012). Introduction: Intermediality as a Theory and Methodology. In J. Herkman, Intermediality and Media change (pp. 10-29). Tampere University Press. Retrieved from https://tampub.uta.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/67998/Intermediality%20and%20Media%20Change_PAINOON_26.11.2012.pdf?sequence=1

Kurosawa, A. (1983). Something like an Autobiography. California: Audie E.Bock, Vintage International.

Lessing, G. E. (1968). Laocoon an essay upon the limits of painting and poetry. New york: The Noonday Press.

McLuhan, M. (2001). Understanding Media The extensions of man. London and New York. Retrieved from http://robynbacken.com/text/nw_research.pdf

Mera, M. (2009). Invention/Re-invention. MSMI, 1-20.

Mitchell, W. (1984). The politics of Genre: Space and Tie in Lessing's Laocoon. The Regents of the University of California, 98-124.

Petho, Á. (2011). Cinema and Intermediality: The Passion for the In-Between. 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Reider, N. (2005). Akira Kurosawa's Dreams as seen through the principles of classical Japanese literature and performing Art. Japan Forum, 1-17.

Stafford, R. (2010). Kurosawa: Master of World Cinema. Film and Media Education since 1990, 1-7. Retrieved from https://itpworld.wordpress.com/tag/kurosawa-akira/

Vernallis, C. (2004). Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context. Oxford Scholarship Online, 3-27.

The full movie : http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0100998/

i

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekend Top Ten #352

Top Ten Cartoons of my Childhood

After last week’s celebration of cinematic vulgarity (in which our hero, despite dropping more Fs and Cs than an explosion at a Scrabble factory, still managed to forget about Nick Frost in Shaun of the Dead), I wanted to restore balance to the Force somewhat by turning the clock back to simpler, more gentle times. In fact, we’re rewinding eighty-plus years by looking at children’s cartoons of my youth.

So here we have, quite simply, my favourite cartoons from when I was a kid. Now I’m saying “when I was a kid” to mean the 1980s – despite the fact that I was, really, still a kid for most of the 90s too. But Batman: The Animated Series debuted early in the 90s, and at that point I think the crossover between what I loved as a nipper and what I love now started to happen. I don’t think I can rank where Young David would place Batman without Old David weighing in to call it the greatest animated show of all time (fun fact: it is). So I’ve stuck to the 80s, which rules out the likes of Animaniacs, Reboot, Tiny Toons, Aladdin, X-Men, and loads more. Maybe I should have just called this “cartoons of the 80s” and been done with it. But here we are.

So, in conclusion: these are, to the best of my memory, my favourite cartoons from when I was a small boy. I’ve tried to think about what I loved and remembered from back then, rather than attempt to appraise what the shows are like nowadays; many of these I’ve not seen for decades, and some of them really do not hold up (Turtles in particular is rather shonky, and even my beloved Transformers varies wildly in quality). But they are what they are, and exist as articles of their time; I loved all of these as a nipper, and in many cases went out of my way to get comics, books, toys, and other manner of merchandise relating to my favourite telly programmes.

Now let’s take a trip down memory lane!

The Transformers (1984-1987): I mean, come on; how could I not? This show casts a longer shadow than anything else. I’ve also watched more of it than other shows, and more recently, so I can confidently say that although it was a relatively cheap toy cartoon from 35 years ago, a lot of it holds up well, so strong were some of these characters and the inherent concept of Robots in Disguise.

The Real Ghostbusters (1986-1991): I loved Ghostbusters almost as much as Transformers. I had the fire station, Ecto-1, a proton pack, the works. I’ve watched some of this relatively recently, too, and it’s very, very good – Old David likes it a lot more than the 80s Transformers toon. There’s even an episode where they bust Orson Welles’ ghost. True story.

Garfield TV Specials (1982-1991): I’m specifically talking about the often whimsical, frequently bittersweet, sometimes bonkers specials that aired sporadically throughout the 80s, many of which I owned on VHS. I remember CITV showed the first few in short groups, so it felt like a short Garfield TV series; but the invention and beautiful painterly style stuck with me, along with the music. Garfield and Friends (’88-’95) also gets a warm mention here, but was wackier and skewed younger, and even as a kid I didn’t love it as much as the more complicated Specials. Also shout out to Happy Birthday, Garfield, which was a behind-the-scenes look at Jim Davis and the Garfield machine, and was a phenomenal influence on little me.

Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles (1987-1996): funnily enough, I always associate the Turtles with the 90s, but I know they debuted in the 80s and I think the TV series aired over here in 1989, so I’m counting it anyway. Turtles was kind of a defining “Big Show” for me as I entered double digits, replacing previous faves Transformers and Ghostbusters (I think Garfield continued in the background as a comic strip). I obsessed over the toys and the merch and the fact that we were denied ninjas and nunchucks on this side of the pond. For shame. Last time I saw the original show I thought it was awful, however.

Muppet Babies (1984-1991): oh, I loved this. I’d have been quite young I guess, although probably the same age as when I was watching Transformers, so go figure. But this was really my main intro to the Muppets, and I remember when they more-or-less featured the Muppet Babies in Muppets Take Manhattan, and seeing them rendered in live-action blew my tiny mind.

The Raccoons (1985-1992): this show seemed to go on forever, a mainstay of my childhood. I remember watching the original TV movie/special, with its human cast and the dogs that go into the woods looking for a star, or something, and finding it a bit weird that those characters were more or less ditched in the series proper. But I still loved it, and I remember it as being rather sophisticated and more complicated than the usual kids’ fair; Cyril Sneer was, obviously, a bad guy, but I seem to remember him becoming complicated and genuinely loving his son who he didn’t quite understand, and slowly warming up over the course of the show. He wasn’t Megatron or Skeletor, is what I’m saying. Plus you had Bert Raccoon, who was a bit of an arse and not always in the right, either. I’ve not seen it in years so maybe I’m misremembering, but Little David found it compelling.

Count Duckula (1988-1993): I know Duckula debuted on Danger Mouse, and I did watch DM too, but really I’m all about the duck. Being a big fan of vampires I was all over this, and I just found everything about it hilarious. I was a bit of a Yankophile too, so I liked that David Jason gave him an American accent. I had tons of Duckula comics, most of which I reckon we threw away. But yeah – loved this show.

Duck Tales (1987-1990): sticking with the duck theme, we have this gem. One of the greatest themes in TV history, and humanity’s favourite Scot, Scrooge McDuck. This was a rollicking, hilarious adventure show with tons of personality, and really helped to kickstart the Disney animation boom of the late 80s/early 90s, which in my mind also encompassed things like Roger Rabbit and the resurgent animated movies, too. I even went to see the movie! I’ve yet to see the remake, sadly, but I applaud the casting of David Tennant.

Inspector Gadget (1983-1986): who didn’t love Inspector Gadget? I think this was probably one of those where it was the repetition of tropes and scenes – “sorry about that, Chief”, “I’ll get you next time, Gadget!” – that made it popular. Gadget was cool, Claw was scary, Brains was funny; this was top-drawer telly. I even wrote a synopsis, a few years ago, for a movie sequel called Inspector Gadget Returns, in which Gadget is old and washed-up, and a grown-up Penny has to bring him out of retirement when Dr. Claw returns. Kinda wish I was an established screenwriter so I could pitch it to someone, to be honest.

Dogtanian and the Three Muskehounds (1981-1982): aw, this show was very sweet. I remember watching it when I was very young (it’s the only show on this list that basically pre-dates me!), and my mum would do the voices of the characters for me. I really don’t remember it very well or how it holds up, but I know that for a little while there, it was seriously my jam. Teeny Tiny David loved it something rotten. If we’re sticking with anthropomorphised animals doing classic literature, I remember Willy Fog much better, funnily enough, but this just sneaks in based on that early childhood love.

Well, there we go. Now I want to watch all of these again. And Willy Fog, for that matter.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Legion of Spoilers - Chapter 4

Legion's latest chapter is a halfway mark in every sense: Chapter 4 falls midway through the season’s eight episode run, and its handful of revelations, capped with that painful ending, promise to be the fulcrum of the remainder of the season. And viewers as well as David stand halfway through a looking glass, struggling to ascertain what is real, and what is reflected.

This episode is also riddled with self-conscious artifice, as though going out of its way to feel like a TV show. Hawley frames this opening with Masterpiece-esque commentary AND a noir-ish voiceover from Syd. Colors and lighting are even more hyper-saturated than usual; shots betray their camera work, and every scene is composed with painterly precision. The artifice is occasionally distracting, which is unfortunate for an episode peppered with so many intriguing hints and reveals.

Oliver Bird plays us in with two introductory monologues, the first attempt abandoned while his drink freezes solid. The theme of tonight’s presentation will be the conflict between empathy and fear, the struggle between mirror images as a man goes to war with himself. And indeed, this chapter is full of unsettling symmetries and incongruities: Lenny (at least Mind Lenny) turns out to be a kind of cover identity for the parts of David’s mind he’d rather not face. Amy and Dr. Kissinger exchange confidences through the wall that divides their mirrored prison cells. Cary and Kerry fight in tandem, riding a psychic link that spans the distance between them. David’s memories of others collide with their memories of him, as Amy reveals David never had a dog, Philly describes David’s actual drug buddy, and Syd deduces that David’s true motive for breaking into Dr. Poole’s office was to destroy records his mind could not overwrite.

This ability to overwrite itself is what makes David’s memory a hall of mirrors. From childhood on, any time he was confronted with something frightening, David clapped his hands over his eyes, again and again, until his mind learned to do it automatically. Now he unconsciously deploys his powers in a fractally complex cycle: React, obfuscate, forget. David's memory glitches are this protective mechanism at work, the childlike conviction that something can't hurt him if he doesn’t look straight at it. If you stand still, The Angriest Boy will catch you. The voices will overwhelm you. The yellow-eyed monster will flower into malevolent being. So David runs.

This served him well enough until D3 and Summerland found him. Summerland wants to teach David how to stand still, but his mind is so used to folding realities that it refuses the concept. David's new friends mean well but they can’t understand what it means to be marooned in a self whose instability is its security. Confronted with empathy, his mind, conditioned to fear, abandons the conscious realm entirely.

While David lies inert in Cary's lab, Dr. Bird dispatches Syd, Ptonomy, and Kerry to uncover what precipitated David's admission to Clockworks. The trio dutifully make their way to the site of the memory that went haywire in Chapter 3: Dr. Poole's deserted but preserved office. Ptonomy and Syd piece together David's memory work vignettes with “object memories” magicked from a demolished tape recorder.

The trio then set up camp in the woods, where Syd's reverie is broken by the appearance of The World's Angriest Boy in the World, who brandishes his fixed scowl and his knife before vanishing. Syd keeps the sighting to herself as Kerry announces she has a lead on David's ex-girlfriend Philly. Then, in a speech that is all but captioned EPIC FORESHADOWING, Kerry explains her relationship with Cary. They share his body, and she emerges at will – mostly when there's fighting to be done – while Cary takes care of “all the boring stuff.”

Elsewhere, Amy's ordeal continues. Tortured and interrogated, then caged and starved, she scrabbles at a foul meal before hurling it against the wall. Hearing this, the adjoining cell's inmate hollers a strange introduction: “I exist!” It's the disappeared Dr. Kissinger. Amy admits that David was a sweet but strange child who moved inexplicably between rooms, knew the substance of unspoken thoughts, and conversed with people who weren't there. Most chillingly, she tells the good doctor that they never had a dog, and that she never saw the King to whom David spoke. Dr. Kissinger flashes back to the day David walled up the inmates of Clockworks. In contrast to previous iterations of that memory the series has shown us, he's unaccompanied by Syd and there's no sign of Lenny. At least Amy has some company now.

Back at Summerland, Dr. Bird finds herself before an apparition in an antique diving suit. She grabs Cary and they descend to a hidden sub-basement, speaking gently and obliquely about missing pieces. Cary admits to missing Kerry when she's away, and since she only ages when she's outside, he wonders (EPIC FORESHADOWING) what will become of her when he dies. Melanie floats the obviously well-worn hope that this will be the time her husband returns. Oliver is sprawled on a table in a kind of cryo-chamber, diving suit peppered with rime and air hose trailing out of the frame. Neither alive nor dead, he’s stuck somewhere in between. As Melanie and Cary enter, a buzzer goes off, warning lights flash, and an automated voice calls out “Unannounced Visitor.” The system, linked somehow to the astral plane, has registered David's arrival.

David has not quite registered David's arrival to this strange place that looks like the aurora borealis crash-landed in the Grand Canyon. After a bewildered look around, he follows the beckoning figure in the diving suit to a ladder. Together they ascend into the ice asteroid we saw in the episode's opening. Oliver introduces himself and asks how much has changed since he got stuck there, somewhere at the convergence of beat poetry, avant-garde jazz, leisure suits, and free love. David doesn't seem to recognize or care that he's having a tête-à-tête with Melanie's long-lost spouse. As always, his impatience for an exit truncates the explanations that could help viewers piece together the story; Oliver barely gets a chance to explain the astral plane or the creature that dogs David's memories and has followed him here. Maybe David doesn't really want to know. He climbs back down the strange ladder and strikes out across the undulating mindscape.

In the meantime, the Summerland trio have tracked down Philly. She tells them that David's drug buddy was a large and unpleasant man by the name of Benny, whose face and identity David has apparently overwritten. When he scans her memories, Ptonomy witnesses encounters with Benny and with Dr. Poole. She and David had him over for lunch, and later, she visited him, now blinded and scarred, at a lighthouse. Our detectives make their way to the lighthouse and convince Dr. Poole to talk to them. He admits them grudgingly before transforming into the Eye and signaling D3 to spring its trap. A SWAT-like team closes in, driving the three upstairs in a hail of bullets. Kerry leaps out the nearest window to beat back the commandos and clear an escape route while The Eye pursues Syd and Ptonomy to the attic room where they've taken refuge.

So begins a well-executed montage in the grand style which is also a trademark of Hawley’s TV adaptation of Fargo. To the strains of Feist's “Undiscovered First,” Oliver dances in the ice asteroid of his mind as Melanie mourns his body, Cary vicariously follows Kerry's hand-to-hand, and Amy paces in her cell as The Eye closes in on Ptonomy and Syd. Ptonomy's bullets can't seem to connect, and once the gun is out of bullets he’s subdued with a touch. Cornered, Syd slips off a glove, meets The Eye's hand, and switches bodies just in time to receive the commandos' confirmation of Kerry's capture. “The Eye” orders the captives placed in the van and takes the wheel.

Back in the astral plane, Lenny confronts David in a mirror image of his childhood bedroom. Agitated and anxious to leave, she goads him – again – into using his power by showing him someone he loves in danger. Seeing “Syd” tied up by “The Eye,” he howls with rage, the Devil flickering behind his face, and teleports straight toward the path of his friends' escaping van. After it swerves off the road, David frees “Syd,” setting in motion a foot chase that gives The Eye enough time to regain his body and shoot Kerry. Miles away, Cary collapses, clutching at an invisible wound. As David looks on in horror, a gangrenous hand curls around his shoulder, and “Lenny” smiles – but not with her eyes.

QUOTES

“The past is an illusion.”

“Who are we, if not the stories we tell ourselves?”

“Is free love still a thing?”

“Defeat the dragon. Unless, you know, the dragon wins.”

“Pity. Two more and we could have had a barbershop quartet.”

“In times of peace, the warlike man attacks himself.”

-Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

“To fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence. Supreme excellence consists of breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.”

-Sun Tzu, The Art of War

ODDS & ENDS

That nugget from The Art of War is basically how demon-Lenny subdues David.

Shout-out #2 to Italo Calvino: Philly works at Calvino Realty. (Shout-out #1 was the ambulance company in the pilot).

We still don’t know what the stars say to David.

Has Amy’s husband filed a missing persons report? Is anybody looking for her?

If David’s story is about a conflict between fear and empathy, fear is off to a great head start: It originates in the amygdala, and in Chapter 2 Cary observed that David’s was unusually large. Interestingly, the amygdala is also involved in memory formation.

The posters for Enceladus and Europa in David’s childhood room are two of the vintage-style solar system travel posters you can download from NASA.

Legion continues to confound attempts to peg it to a single time period; this week's anachronism is Ptonomy's Luger, a pistol historically associated with Nazi-era Germany.

The Eye’s powers are varied and as yet unexplained. First of all, either he’s wearing space-age clothing or he has the power to deflect bullets. He can’t just be a bulletproof mutant, because then his clothes would have bullet holes. He can also knock people out by touching them, doing something to one eye in the process and has sufficient psychic chops to spot David and Syd’s astral forms.

According to the tablet on her desk, Philly’s full name is Florence Welch, also the name of the lead singer of Florence and the Machine.

The beat poetry Oliver recites to David is a selection from Allen Ginsberg’s A Supermarket in California, which includes the line I wandered in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans following you, and followed in my imagination by the store detective, which sounds a lot like the wandering and chasing in David���s mind.

Based on this week’s theme of smoke and mirrors, Hawley may be referencing Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly, Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. All three works deal with mirroring, mental illness, the nature and limits of the self, and shifting internal perspectives.

This chapter’s significant music selections: The avant-garde jazz Oliver puts on for David is Sonny Simmons’ Metamorphosis. In keeping with the episode’s theme of mirrors and reversals, the cover image from that album is a reverse negative. The song that plays over the montage is Feist’s “Undiscovered First.” Mind-Lenny calls David a mountain climber just before Feist’s lyrics ask “Is this the right mountain/For us to climb?”

FAN THEORIES, or WHAT THE HELL I THINK IS GOING ON

My theory is that this episode was written and shot to feel like TV to telegraph that most or all of it is one of David’s invented realities, maybe a TV-show-esque reality (or pocket universe!) his mind created to cope with something traumatic. The strongest piece of evidence for the unreality of what we’ve seen so far, aside from the outlandishness of that lighthouse, is the sign the van hits in the final act. It reads: Slow Down: Uncertainty Ahead.

As in The Wizard of Oz (also name-checked in the intro), at least some of the characters must be real people superimposed on this parallel reality. My guesses: Amy, Philly, Melanie, Oliver, Brubaker, and The Eye are real. I’m on the fence about Kerry, Cary, and Ptonomy. The case for Lenny in any reality is now mighty thin (although if Clockworks was a real place, it remains possible that she was a fellow patient David later wrote into his memories of Benny), and even thinner for Syd, who should have appeared alongside Dr. Kissinger in his flashback. In the first episode, when Syd visits David in his room at Clockworks, his door opens and closes no one actually steps over the threshold. Syd has also begun to see The Angriest Boy in her waking life, which would make sense if some other parts of David’s consciousness are encroaching on that personality.

Speaking of The Wizard of Oz, we don’t currently know what’s real, but the mirror theme pervading this episode makes me think most of what we’ve seen so far is just a reflection of a reality yet unseen.

There’s an internal logic to David’s primary coping mechanism being the creation of new worlds, people, and memories. Some small quantity of self-delusion is part of the human condition; we are, as Syd observes, the stories we tell ourselves. Stories mediate between the self and the reality outside it, allowing us to develop and contextualize what we think of as our selves. David can’t tell himself any coherent stories about himself, let alone the people around him, because his telepathy eroded his ability to establish boundaries between self and other.

This being a delusion or pocket reality would explain why real people (that is, people who exist outside of David’s mind) see and interact with latent personalities and imagined characters.

Legion’s shots change aspect ratio, seemingly based on whether they are showing us present time, memories, and (possibly) delusions. The deeper into the unconscious a shot takes us, the more black space appears in the upper and lower thirds of the screen. For example, when Kerry references her childhood and the scene cuts to Cary/Kerry’s shared memory, the screen narrows slightly. It narrowed significantly during David’s botched memory work in Chapter 3. Based on aspect ratios I’d say there’s a strong likelihood D3 (or something like it) exists and Amy really is in their custody.

This episode gave us the longest shot yet of a fluorescent-lit corridor that has previously appeared only in brief flashes. One glimpse of the corridor shows a hooded figure slumped against a damaged observation window, whose crack pattern resembles the damage Cary’s lab window suffered while David was astrally projecting in Chapter 3. Also, the circle of light in which David lays is very similar to the stark blue-gray fluorescent lighting of the corridor and Amy’s cell. Could this world be a retreat from D3’s custody?

Recurring motifs: Stacks of circles appear in the astral plane ladder, a sequence of shapes echoed in Philly’s headband (lunch with Dr. Poole) and earrings (meeting with Syd and Ptonomy), Kerry’s belt, and the portholes that run up the sides of Dr. Poole’s lighthouse. The way The Eye’s victims’ eyes crystallize looks suspiciously similar to Oliver’s ice asteroid. Maybe he temporarily banishes his victims’ consciousnesses to the astral plane. The recurrence of particular motifs in unrelated contexts would seem to suggest mental shortcuts as David’s brain reuses certain shapes and images, maybe borrowing them from waking life.

Colorwatch: Oliver’s leisure suit is in the same neutral color family as Melanie and Brubaker’s clothing, if you don’t count the mustard shirt beneath his jacket, which echoes the floor of the common room at Clockworks. Neutrals seems to be worn by people with an interest in mutants, or possibly by those whose allegiance or intent is not yet clear. Lenny wears a vivid blue jumpsuit beneath a beige trench; I still have no theories about blue’s significance. The Vapor is also blue, and may scenes in this episode bear a bluish tint. Philly wears Kelly green edged with black piping, Amy wears the same mint-green clothes in which she was captured, and The Eye wears pale olive green. My original theory was that green is only worn or carried by people free to move in the real world; David carries green only once, when he leaves Clockworks. But the astral plane is a ghostly, insubstantial yellow-green. Maybe the astral plane is a real place, insofar as it’s a realm that exists outside of David and that can be visited by other people with similar powers. It’s probably closer to reality than the world of Summerland. The door to the lighthouse is red, and the lighthouse itself is candy-striped red and white. Red always seems to accompany David’s moments of profound anxiety, reverie or dislocation, especially his great demonstrations of power. And I’m back to speculating that David’s personalities wear black – in this episode only Syd and Lenny wear black.

0 notes

Text

Bad at Sports Sunday Comics with Tara Booth

By Krystal DiFronzo

Tara Booth’s work is an assertive clash of color that depicts the most humbling and sticky situations. Some relatable moments include trying to pee while wearing a romper, cutting bangs into near oblivion, and stoned Amazon shopping (with the resulting surprise package hangover). My first introduction to Booth’s comics were through her Tumblr back in the golden age of cartoonists using that platform. Since then she’s had her work published by kuš! and Colorama. She regularly posts comics and in progress work on her Instagram @tarabooth.

Krystal DiFronzo: The first thing I noticed about your comics is the density of information, there’s so much color and pattern all piled on top of each other! Also you use gouache like a painter, not like a cartoonist coloring between lines. The ghost layers of paint create this constant atmospheric movement. The reader is made aware of the hand and medium, unlike traditional pen and ink comics. Do you have a background in painting prior to your comics? If so, why the transition to comics or are they all part of a single practice?

Tara Booth: I studied painting and graduated with a BFA at Tyler School of Art. I used to work on big 4×5 foot canvases that I built, stretched, gessoed, and sanded over and over. This time-consuming preparation, combined with the preciousness of the material gradually grated on me. I appreciate the importance of these processes and I’m happy to have access to this skill set, but it wasn’t something that I ever wanted to include in my everyday art practice (due to my extreme and often debilitating impulsivity). Producing work in art school wasn’t a problem for me, but I wasn’t a great student. It became increasingly difficult to connect to ideas being taught in my painting and art theory classes, which were focused more on abstraction and conceptualism than direct representation or narrative, which is where my interest had always been. The language and concepts we studied felt really inaccessible and detached from my experiences as a highly-dramatic, drunk 21-year-old. I started to focus more on folk art, Lowbrow, and self-taught artists. I began reading more comics, and decided I wanted to make paintings that were direct, accessible, and inexpensive to produce—so I transitioned to working on paper with gouache, with the ambition of eventually making my own comics.

KD: Your comics also have a lot of unusual formatting choices that affect how you read it. They don’t have any formal paneling or gutters, they flow across the page almost like an animation or a Muybridge study. You can read the comic either left to right or as a single-paged composition. They are also predominantly dialogue-less other than their titles. What made you come to these decisions? What’s your planning process like?

TB: The unusual formatting in my comics isn’t something that I had planned. For the longest time I felt really stunted by my background in traditional painting. I bought a bunch of comics, and attempted to mirror the techniques I saw, but working in panels always felt totally awkward. I had little experience with Photoshop, storytelling, principles of design… teaching myself how to make a comic felt like an uphill battle. Five years after graduation, I still hadn’t produced anything solid. I had kind of given up, and finally decided that making a shitty comic was better than not making anything at all—that I should worry less about what I think a comic is supposed to look like, and more on painting within the realm of my own abilities. Once I threw all of my preconceived notions out the window and forced myself to get to work, I actually started to get recognition for what I was doing rather quickly. Embracing some of my naivety and focusing on the painterly qualities in my work has compensated for whatever technical obstacles stood in my way. I still struggle with using text in my work. Until I’m more comfortable with my writing, I’m relying symbols, visual cues, facial expressions, and body language to tell my stories.

I like that you mention Muybridge studies, I look at them all the time. They’re one of my main influences. I love them!

KD: It’s a common trope of comics or animation that characters wear the same outfit. Like opening up a closet to rows of one identical dress. Your stand-in wears such incredible outfits in every comic, they almost become characters themselves. Do you have an interest in design? (Please make Fantomah leggings a reality.)

TB: Ha! I would love to work in textile design. In a failed attempt to simplify my life, I’ve ended up with a pretty boring wardrobe. I like to use my little avatar as a paper doll, dressing her up in outfits that I wish I owned myself. (Does anyone want to offer me a job?) I also use the clothing as a way to explore difference ways of drawing. To find different ways to use line, play around with abstraction and incorporate more surreal subject matter. I spend so much time working on this one body of work, I haven’t been prioritizing stylistic experimentation. It��s nice to have tiny t-shirt shaped opportunities to paint in ways that might feel separate from my comics practice.

KD: I’m emailing you while you’re at Printed Matter’s LA Book Fair, what was the show like for you? Could you talk about your new book with Colorama?

TB: The Art Book Fair was great! Like plenty of other artists I have a lot of anxiety in social situations, so it was stressful for me, but wow—so much of that melted away as the fair went on. It felt amazing to be surrounded by so many talented people, beautiful books, and all of the supporters who make this stuff possible. I was able to spy on a lot of my instragam art crushes. I loved watching how excited people were to buy my work. I got to see them laugh as they flipped through my prints, and I had some fun conversations. A few people even brought me gifts! But the most important and exciting part of the Art Book Fair was finally meeting my publisher, Johanna! She runs Colorama, a publishing house in Berlin. We’ve been communicating through email for months now, and it felt like the best blind date ever. The book she published for me, “D.U.I.I”. is the riso printed story of one of the most awful experiences I’ve had. It was also one of the most beneficial things that has ever happened to me. I got a DUII in February 2016. I’m an alcoholic, and this was the culmination of years of increasingly toxic behavior. Court ordered sobriety seems to be the motivation that I needed to change. I’m incredibly thankful that I didn’t hurt anyone. It’s a humiliating story to tell, but I felt a compulsion to draw it all out. I feel so lucky that Colorama decided to work on this project with me. It’s very different from my more popular, colorful work. I’m still dealing with the stressful and expensive results of that experience. Making the book was a huge part of the process of working through it. I tried to lighten it up a bit and make it silly—but yeah, its all true.

KD: Your work is true to life but veers into the surreal. It feels like it’s in the same vein as work by Julie Doucet, Gabrielle Bell, or Dori Seda. Artists who told confessional stories of humiliation and embarrassment but added fantastical elements for comedic or therapeutic effect. What about writing semi-autobiographical work interests you? Do you see yourself leaning more towards fiction or towards memoir?

TB: I’ve always been drawn to autobiographies, in comics and in literature. I really admire a lot of the artists you mention, and confessional work like theirs is part of what inspired me to make comics to begin with. For years I’ve kept a diary filled with drawings, but its tricky. Really putting yourself out there is scary. The paintings that I post publicly, while totally based on my daily life, are drastically different in tone and content than what you might find in my journals. My comics are embarrassing, funny, absurd, relatable… they can be sad, but I think it’s easy to see how I use humor and fantasy as a way of dodging some of the more raw and dangerous territory that can make autobiography so potent. I’m glad that my drawings make people laugh, I don’t want to take myself too seriously and I’ll always make silly drawings… I guess I just hope that as I continue to make comics, I’ll find a way to add more depth to my practice, whether it’s by working on developing more complex fictional stories, or by being brave enough to express some of the heavier, and maybe less palatable aspects of my life.

KD: Outside of comics, what artists or media makers are inspiring you right now?

TB: Well, first I’d like to say how incredibly inspired I am by artists like Marie Jacotey and Aidan Koch, whose work transcends the world of comics. I want the space between the comics world and the art world to keep getting smaller and smaller. These two stand out in my mind as artists that are helping to bridge that gap. I’d love to be a part of that transition. I’m always discovering new painters. Some of my favorites are Misaki Kawai, Austin Lee, Mogu Takahashi, Katherine Bernhardt (I’m inspired both by her paintings, and by the gorgeous Morrocan rugs that she sells) and Danny Fox. These people remind me of how powerful one large stand alone image can be. I follow the work of so many illustrators, but my favorites are probably Aart-jan Venema and Monika Forsberg, I’m always trying to figure how they do what they do. Who else… there’s a lot of really interesting stuff happening with ceramics that makes me want to get my hands on some clay. Benjamin Phillips is making great pots, it looks like it could be really fun to work in that style. Clay reminds me of Janie Korn, who makes really fun claymation shorts. Having access to all of these creative minds through social media sheds light on the infinite avenues that I want to explore in the future.

To order D.U.I.I, head to the COLORAMA webstore.

Dark Noise : An Interview with Chris Hammes

Half the sky, all your attention.

What We’re Doing This Weekend: 3.20-3.22

Endless Opportunities (Or Something)

MAINTENANCE #3

from Bad at Sports http://ift.tt/2mHQxB6

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

She Remembered Caterpillars // Jumpsuit Entertainment // Available on Steam now (£8.99)

There’s something deeper happening here

Despite sounding like an early 2000’s indie band, She Remembered Caterpillars is a spellbinding puzzle game hailing from developer Jumpsuit Entertainment. Its 40 enchanting colour-based conundrums combine painterly visuals, minimalist sound design and a sombre narrative that results in one of the finest puzzle games you’ll ever play.

At its core, She Remembered Caterpillars’ puzzles revolve around some brightly coloured critters called “Gammies”. The aim of each level is to guide these Gammies to a specified end-point, navigating a manner of obstacles along the way. These obstacles range from coloured bridges and gates to collapsable walk ways and colour changing showers that alter the Gammies’ hue. Each of these obstacles has unique characteristics and presents a certain degree of challenge to the player. Individually, these obstacles are relatively simple to conquer (bridges will only let Gammies who match in colour to cross, gates will only let Gammies of an opposite colour pass through them, etc.) but it’s in their fiendish combination where things can get a little hairy.

Fortunately, She Remembered Caterpillars does a stellar job of introducing these varied mechanics at a very manageable pace. In its initial opening hour or so, it uses some exquisite game design to ensure that no player gets left behind. It teaches you the core mechanics in very much the same way as Jonathan Blow’s The Witness does, letting the gameplay alone inform the player. In no time at all, you’ll know how to blend the three base colour Gammies (red, blue and yellow) to make the three additional colours (purple, orange and green). You’ll know how each of those coloured Gammies interact with the bridges. You’ll know exactly which gates each of them can pass through. You’ll easily get the hang of how to play She Remembered Caterpillars and find that you’re smashing through the levels at respectable pace. Then things will begin to change as the game slowly turns into a bit of a bastard.

This one had me pulling my hair out…

The later levels begin placing obstacles in what seem like impossible layouts and mind-boggling combinations. The sheer sight of some levels in She Remembered Caterpillars’ is truly exhausting and I have genuinely turned the game off more than once because I could not face what Jumpsuit Entertainment had thrown at me. But there’s a magnetism to She Remembered Caterpillars and time and time again it pulled me back, rewarding my perseverance. Every failure was a lesson and each step I commanded the Gammies to take taught me a little bit more about She Remembered Caterpillars’ charming, if a little frustrating world.

Scratching the surface

The puzzles however, only signify what’s happening on the surface level of She Remembered Caterpillars. Each level is punctuated with screens of text that allude to some sort of narrative through-line. At first it’s ambiguous and not all that apparent in its subject. Its connection to the gameplay appears loose, almost confusing at times but as the game progresses that connection becomes clearer. She Remembered Caterpillars tells of a confrontation with death, specifically with the death of a parent. It explores this using those exquisitely written intersections that progressively give you a sense of purpose to what you’re actually doing in the game. It offers up some exposition to the gameplay and encourages the player to attempt a personal interpretation beyond the game itself.

Even now, days after I’ve finished She Remembered Caterpillars I still find myself going over it in my head. I’m going back just to read the text and piece together what She Remembered Caterpillars is all about, coming up with my own connections between the narrative and the gameplay. Through my own compulsions to understand the meaning of everything, I found myself theorising that the Gammies were some sort of infection and that each completed level indicated a step closer to death.

Am I right? Who knows, but it does illustrate the wonderful effect She Remembered Caterpillars has on the player. Its bread and butter are its puzzles but everything else that makes up the game takes it beyond a simpler puzzler and allows it to speak to something deeper than itself.

There is an obvious attention to detail with She Remembered Caterpillars, not just in the puzzle design but in every single aspect of the game. Its environments are atmospheric and enchanting. Its soundtrack is minimalistic, complimenting the visual styling and gameplay. The narrative between levels is sombre yet shrouded in a glimmer of hope. All of these moving parts work succinctly and in tandem with one another to produce a truly touching game and one of the best I’ve played in a long time.

To Conclude…

As a straightforward puzzler She Remembered Caterpillars can only be described as wonderful. Its puzzle mechanics, art style and sound design combine to create one of the best puzzle games in recent memory. She Remembered Caterpillars goes beyond this though, exploring themes and concepts that are seldom found in video games, let alone found in puzzle games. She Remembered Caterpillars asks the player to think beyond what it offers on a surface level, encouraging not only a deeper examination of the game but also a deeper examination of ourselves.

You should not pass up on this game.

Have you played She Remembered Caterpillars? Did you love it as much as me? Or am I just a bit too sensitive? Come and let me know over on Twitter @darryldoes!

Full Disclosure – A code for She Remembered Caterpillars was kindly sent to me by Jumpsuit Entertainment. This did enable me to write this review but in no way did it alter my opinion on the game. It is genuinely brilliant.

-- She Remembered Caterpillars Review -- @thejumpsuits have made quite a game here... She Remembered Caterpillars // Jumpsuit Entertainment // Available on Steam now (£8.99) There's something deeper happening here…

#Attempted Actuality#blogging#gaming#indie#indie games#journalism#jumpsuit entertainment#opinion#pc#she remembered caterpillars#steam#video games#writing#ysbryd games

0 notes