#decolonization is not a metaphor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Disentangling decolonization from the impulse to make it a species of a larger struggle, Tuck and Yang differentiate between an “indigenous politics” (which would integrate land with life) and a “western doctrine of liberation” (instrumentalising land for life). The prioritisation of land, however, problematises the efficacy of the distinction for, as Jared Sexton (2014) addresses, regardless of the approach to land (Indigenous or otherwise), the issue for critics of settler colonialism remains primarily a “problem of the terms of occupation”:

This frames the question of land as a question of sovereignty, wherein native sovereignty is a pre-condition for or element of the maintenance or renaissance of native ways of relating to the land (Sexton 2014:5).

The danger is that, while admitting “denial of sovereignty imperils native ways of relating”, the configuration of sovereignty as a positive claim to land “does not thereby guarantee this way will be followed” (Sexton 2014:5). Tuck and Yang’s argument subordinates this risk to a problem they see to be much more fundamental and abiding: that recognising life (which becomes a stand-in for symbolisation) may not materialise (and usually actively impedes) the repatriation of land.

To return to the problem of via negativa, Tuck and Yang cannot positively address what Indigenous approaches to land are, without complicating how land is the ground upon which decolonization hinges. In this way, they succumb to the seduction described by Katherine McKittrick in the epigraph—“the idea that space ‘just is’” (2006:xi). Their critique of metaphor serves as a counterfactual to what they see to be the central problem of (and solution to) settler colonialism— land—even as this single focus undercuts what might differentiate settler sovereignty from native sovereignty. By making metaphor “bad”, Tuck and Yang illustrate a re-investment in sovereignty as an empty vessel, whose substantial difference from property orientations becomes indiscernible, except in the fleeting accelerationist fantasy later posed by Tuck and McKenzie that “decolonization may be something the land does on its own behalf, even if humans are too deluded or delayed to make their own needed changes” (2015a:xv).

Now, we might side with Tuck and Yang to argue that the focus on land (and land-based articulations of sovereignty, property, and possession that accompany it) is but a strategic response to the violence of settler colonialism itself, that it would open up to considerations of “land and life”. Robert Nichols takes such a tack: while Indigenous scholars who mobilise the language of dispossession for decolonial ends might seem to invest in a prior mode of possession (insofar as dispossession is the retraction of possession), the rhetorical use of “theft of land” is a necessarily recursive attempt to access the peculiar way the settler-colonial project functions to fulfill “not (only) ... the transfer of property, but the transformation into property” (Nichols 2018:14; see also Brown 2013; Coulthard 2016:96).

Colonial dispossession is, in other words, the emergent expression of the property-logic that comes to mark colonial capitalism. Nichols might charge our argument, as he does Sexton’s, with a “dubious line of reasoning”: that of attempting to “catch Indigenous peoples and their allies up on the horns of a familiar dilemma” (Nichols 2018:11). Instead, scholarship should be attuned to how “the supposed circularity of the critique is, in fact, reflective of the recursive logic of dispossession itself, that is, as a mode of property-generating theft” (Nichols 2018:22). As “a unique species of theft for which we do not always have adequate language” (Nichols 2018:14), land-based theft actualises the proprietary system of right to begin with. Colonialism, then, “is not an example to which the concept [of dis/possession] applies, but a context out of which it arose” (Nichols 2018:21; see also Radcliffe 2017). Nichols’s argument echoes Tuck’s, which decidedly persists in using “repatriation” (as opposed to “rematriation”) because the imperfect term reflects “the inadequacy of the English language to describe and facilitate decolonization” (Tuck 2011:35). Inadequate concepts might generate friction, but the resulting “blisters can be drained and the work can still be completed” (Tuck 2011:35). Despite decrying the decolonization metaphor as a dangerously non-material mode of symbolisation, this logic contends that there are nonetheless effective symbolic strategies whose use can draw attention to the limits of the symbolic.

But Tuck and Yang are not interested in critiquing the decolonization metaphor as symptom or strategy. They draw strength from a more metaphysical claim: the positivism professed in the capacity to identify anything at all. This faith, which functions as a sort of love, comes to the fore in Tuck’s recurrent reference to a quote by Fred Moten: “everything I love survives dispossession, and is therefore before dispossession” (quoted in Tuck and Yang 2012:10). Tuck and Yang’s libidinal investment in the precedent of land actually indexes the non-recursivity of dispossession. As indicated by the affirmation of “outside elsewheres” and decolonial forms of life, the object of dispossession (land) is ontologically prior to the agent of dispossession (settlers). Land-based sovereignty thereby ensures that Indigenous people’s positive (even if unstated) claims to land remain undetermined by the settler-colonial regime of property. This is the position from which Tuck and Yang’s political appeal unfolds."

- Tapji Garba and Sara-Maria Sorentino, "Slavery is a Metaphor: A Critical Commentary on Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor”," Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography. Vol. 52 No. 3 (2020): 770-771.

#decolonization#decolonization is not a metaphor#settler colonialism#critical theory#critical analysis#reading 2025

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This is a video about indigeneity in video games and uses the Essay "Decolonization is not a metaphor". It only has about 2.3k views.

This is my first time on tumblr and my first post. Thx and take care.

#decolonization#indigenous solidarity#white mountain apache#turtle island#indigenous#native american#first nations#land back#video essay#decolonialism#decolonization is not a metaphor#first post#youtube video#video games#Youtube

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmm. So, you’re telling me, instead of defending a land ‘promised to you by God Himself’, you’re choosing to flee from it? You’re choosing to abandon it just like that? It’s giving wussy occupiers.

On the other hand, Palestinians have been defending it for decades at the expense of their own lives and the lives of their loved ones. Wait a minute, sounds like true natives to me.

#free palestine#let gaza live#i stand with palestine#decolonization is not a metaphor#israel is an apartheid state#end the occupation#Iran#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#palestine

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you’re celebrating the bell riots are you also done condemning you-know-who yet?

#decolonization is not a metaphor#free Palestine is not a metaphor#Star Trek#bell riots#violent resistance is inevitable so long as violent injustice exists

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decolonization as metaphor allows people to equivocate these contradictory decolonial desires because it turns decolonization into an empty signifier to be filled by any track towards liberation. In reality, the tracks walk all over land/people in settler contexts. Though the details are not fixed or agreed upon, in our view, decolonization in the settler colonial context must involve the repatriation of land simultaneous to the recognition of how land and relations to land have always already been differently understood and enacted; that is, all of the land, and not just symbolically. This is precisely why decolonization is necessarily unsettling, especially across lines of solidarity. 'Decolonization never takes place unnoticed' (Fanon, 1963, p. 36). Settler colonialism and its decolonization implicates and unsettles everyone.

Eve Tuck & K. Wayne Yang, "Decolonization is not a metaphor"

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

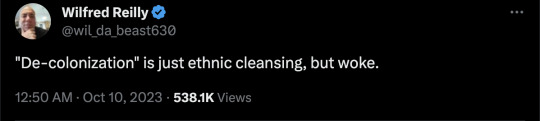

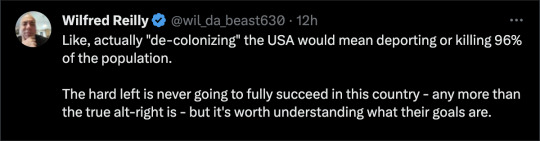

Now you know.

Believe them when they tell you what they're up to.

#Wilfred Reilly#decolonization#ethnic cleansing#decolonization is not a metaphor#genocide#religion is a mental illness

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Directly and indirectly benefitting from the erasure and assimilation of Indigenous peoples is a difficult reality for settlers to accept. The weight of this reality is uncomfortable; the misery of guilt makes one hurry toward any reprieve. In her 1998 Master’s thesis, Janet Mawhinney analyzed the ways in which white people maintained and (re)produced white privilege in self-defined anti-racist settings and organizations. She examined the role of storytelling and self-confession - which serves to equate stories of personal exclusion with stories of structural racism and exclusion - and what she terms ‘moves to innocence,’ or “strategies to remove involvement in and culpability for systems of domination” (p. 17). Mawhinney builds upon Mary Louise Fellows and Sherene Razack’s (1998) conceptualization of, ‘the race to innocence’, “the process through which a woman comes to believe her own claim of subordination is the most urgent, and that she is unimplicated in the subordination of other women” (p. 335). Mawhinney’s thesis theorizes the self-positioning of white people as simultaneously the oppressed and never an oppressor, and as having an absence of experience of oppressive power relations (p. 100). This simultaneous self-positioning afforded white people in various purportedly anti-racist settings to say to people of color, “I don’t experience the problems you do, so I don’t think about it,” and “tell me what to do, you’re the experts here” (p. 103). “The commonsense appeal of such statements,” Malwhinney observes, enables white speakers to “utter them sanguine in [their] appearance of equanimity, is rooted in the normalization of a liberal analysis of power relations” (ibid.). In the discussion that follows, we will do some work to identify and argue against a series of what we call ‘settler moves to innocence’. Settler moves to innocence are those strategies or positionings that attempt to relieve the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land or power or privilege, without having to change much at all. In fact, settler scholars may gain professional kudos or a boost in their reputations for being so sensitive or self-aware. Yet settler moves to innocence are hollow, they only serve the settler.

- Eve Tuck & K. Wayne Yang, Decolonization is not a metaphor (2012)

#settler colonialism#decolonisation#decolonization#land back#decolonization is not a metaphor#lukemisiani

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps my most controversial opinion is that if you live in a settler colonial state, any land you buy should at minimum be regifted to the Indigenous nations it belongs to upon your death.

#land back#decolonization is not a metaphor#settler colonialism isn’t in the past#you CAN do something about it#i intend to give any land I inherit back to tribal nations#in my lifetime#I have no need for stolen goods

0 notes

Text

My girlfriend is reading 'Decolonization is not a metaphor' by Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang, and in it, they excoriate Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans for its colonialist romanticism and appropriation of the native identity, and rightly so I suppose.

But they also take the bizarre step of claiming Mohicans are a fictional people. And their concluding paragraphs posits an alternative decolonial version that would somehow involve the Mohawk.

And now I don't doubt that Last of the Mohican's portrayal of native americans is horribly problematic and flawed (I haven't read it but supposedly it mixes up Mohicans and the related Mohegan people)... but the Mohicans are decidedly not fictitious !

There exist a Mohican nation to this day !

I cannot begin to imagine how two scholars from this field could make a mistake so egregious, I think they might have oversimplified something and not reread carefully. It's driving me insane.

0 notes

Text

youtube

So I use YouTube for news most times. I'm subscribed to Indian Country Today. It's a YT channel that goes over Native American and other indigenous news in America but it is a part of Arizona State University. I've watched the news from ICT for over a year now but if your interested in Native American and indigenous focused news give Indian Country Today at try. I see them as a small news organization that can't cover all indigenous peoples and their News but I want to share where I get some of my news on other Indigenous people.

#decolonization is not a metaphor#indigenous rights#indigenous solidarity#indigenous sovereignty#news#youtube video#building community#native american#current events#try something new#turtle island#decolonialism#decolonization#representation#white mountain apache#first nations#native#ndn#liberation#indigenous peoples#Youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The sooner we realize that some of these nations and influential organizations, including the UN, are not as powerless as they may seem; rather, they undoubtedly benefit from conflicts of interest that won’t allow them to step in or charge N3tanyahu for international crimes against humanity, the easier it will be for us to stop expecting humanitarian intervention from them.

They are well aware of the consequences. If they were genuinely concerned about human rights violations, why did they allow the occupying state to violate them in the first place? Why did they not find a solution to this and punish the criminals when these violations have been occurring before their eyes for the past 75 years of the Israeli occupation of Palestine? It’s not like this situation suddenly escalated out of nowhere. Where were these organizations for all these years?

They’re deliberately choosing not to intervene and mandate a ceasefire because almost every single nation, including powerful organizations like the UN, has an equal stake in the Palestinian genocide. They’re feeding themselves off of the Israeli war crimes.

I don’t know how else to explain this complicity or view this situation from a legal or political perspective, but I do know that we’re not as uninformed as they think we are. I do understand the power of collective resistance. We do have the power to prevent history from repeating itself. We do have the power to change the narrative. We can’t let future generations wonder how we allowed this genocide to take place. I don’t want our kids to view us as a generation that bragged so much about its progressiveness, is also the same generation that enabled a literal genocide during their time.

We can’t be known as bystanders when we do have the ability to stop these horrors from taking place. I know you and I are not the ones in authority. We are just ordinary individuals, with regular jobs, but the least we can do is educate ourselves and others. The people of Palestine need us. The least we can do is use social media as a weapon to spread the truth. The least we can do is join protests and be so loud with our voices that those in power have no choice but to listen. The least we can do is be the voice for the oppressed. The least we can do is be the change we want. We’re revolutionaries, people. Let’s act as one.”

— Syeda Zehra Fatima

#Free Palestine#Free Gaza#Israel Is An Apartheid State#I Stand With Palestine#Gaza Under Attack#Decolonization Is Not A Metaphor#poets on tumblr#writers on tumblr#female writers#poets#writers#writers and poets#poetscommunity

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

==

Believe them when they tell you what they're up to.

#Christina Buttons#woke jihad#decolonization#decolonization is not a metaphor#genocide#ethnic cleansing#religion is a mental illness

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Settlers are not immigrants. Immigrants are beholden to the Indigenous laws and epistemologies of the lands they migrate to. Settlers become the law, supplanting Indigenous laws and epistemologies. Therefore, settler nations are not immigrant nations. (See also A.J. Barker, 2009). Not unique, the United States, as a settler colonial nation-state, also operates as an empire utilizing external forms and internal forms of colonization simultaneous to the settler colonial project. This means, and this is perplexing to some, that dispossessed people are brought onto seized Indigenous land through other colonial projects. Other colonial projects include enslavement, as discussed, but also military recruitment, low-wage and high-wage labor recruitment (such as agricultural workers and overseas-trained engineers), and displacement/migration (such as the coerced immigration from nations torn by U.S. wars or devastated by U.S. economic policy). In this set of settler colonial relations, colonial subjects who are displaced by external colonialism, as well as racialized and minoritized by internal colonialism, still occupy and settle stolen Indigenous land. Settlers are diverse, not just of white European descent, and include people of color, even from other colonial contexts. This tightly wound set of conditions and racialized, globalized relations exponentially complicates what is meant by decolonization, and by solidarity, against settler colonial forces. Decolonization in exploitative colonial situations could involve the seizing of imperial wealth by the postcolonial subject. In settler colonial situations, seizing imperial wealth is inextricably tied to settlement and re-invasion. Likewise, the promise of integration and civil rights is predicated on securing a share of a settler-appropriated wealth (as well as expropriated ‘third-world’ wealth). Decolonization in a settler context is fraught because empire, settlement, and internal colony have no spatial separation. Each of these features of settler colonialism in the US context - empire, settlement, and internal colony - make it a site of contradictory decolonial desires.

- Eve Tuck & K. Wayne Yang, Decolonization is not a metaphor (2012)

#settler colonialism#decolonisation#decolonization#land back#decolonization is not a metaphor#lukemisiani

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Mount eerie#Pnw#Free Palestine#Free turtle island#Land back#Indie rock#Post punk#Romantic Punk#Non-metaphorical decolonization#phil elverum#SoundCloud

1 note

·

View note

Text

would also suggest reading the article decolonization is not a metaphor by tuck and yang. here's the article for free.

if your support of decolonization (anywhere) is predicated on your view of the colonized people as exceptionally peaceable, equitable, environmentally conscious/“in touch” with nature, or otherwise morally superior by your own personal standards, it’s not support. the only moral high ground colonized people need to justify decolonization is …. not being the colonizer

38K notes

·

View notes