#fah lo suee

Text

May 1971. Neal Adams cover for the first appearance of Talia, today called (deplorably) Talia al Ghul. (Adams did not do the interior art for the cover story, which is by Bob Brown and Dick Giordano.)

With all the — entirely justified — criticism of how Talia has been handled over the past decade, one may wonder if there was some prelapsarian nonracist early version of this character. Nope! Talia, like her father, is a character for whom a troubling degree of Orientalist racism is a load-bearing conceptual element. In her initial appearance she is, by O'Neil's own later admission, just a plot device, a helpless damsel in distress; her relationship to Ra's al Ghul (who had not yet appeared) was apparently added to the dialogue at the last minute, after this issue was mostly finished. In her second appearance in BATMAN #232 (June 1971), this time drawn by Adams, Talia is "promoted" to exotic eye candy, an Orientalist caricature without a single word of dialogue. By her third appearance three months later (in BATMAN #235), she's emerged as a femme fatale of ambiguous motives, an obvious pastiche of Sax Rohmer's Fah Lo Suee, the daughter of Fu Manchu.

Both Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams tended to bristle at the suggestion that Ra's al Ghul has any relationship to Fu Manchu, but the similarities are hard to miss, and Talia is one of those. Fah Lo Suee, first seen in THE HAND OF FU MANCHU in 1917, was at times her father's dutiful servant; at times his rival; and occasionally his enemy, since she could be swayed by the charms of one or the other of his white opponents. She herself was Eurasian, and her moral conflict was unambiguously racialized: Her choice was to succumb to the evil, Asian side of her nature (through allegiance to her father and/or his pan-Oriental secret society), or embrace good and whiteness (in her case, through romance with a heroic white man). You may notice that this also summarizes the basic tension of Talia's roles in the Batman mythos, and not just recently! In a 1984 interview, O'Neil described Talia as "tainted with evil" because of her father, and the degree to which she's ever been portrayed as good or heroic has always been directly tied to her willingness to reject her father in favor of Bruce and whiteness. Save for a throwaway line in this issue about her studying medicine at the University of Cairo (swiftly forgotten even by O'Neil), her role in the stories has never allowed for even the possibility of any third alternative.

To be sure, some of Talia's appearances are more offensive than others, but the point is that she, like Fah Lo Suee, is a character who is fundamentally shaped by Orientalism and ideas of white supremacy, which don't disappear even if one tinkers with the details (e.g., by making both Ra's and Talia white, as the Nolan movies did). That in turn has fundamentally shaped the way Talia is characterized with regard to her son, to whom Talia's racialized moral conflict has essentially been transferred.

#comics#batman#detective comics#neal adams#league of assassins#talia#talia al ghul#denny o'neil#bob brown#dick giordano#fu manchu#fah lo suee#ra's al ghul#sax rohmer#bruce wayne#brutalia

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

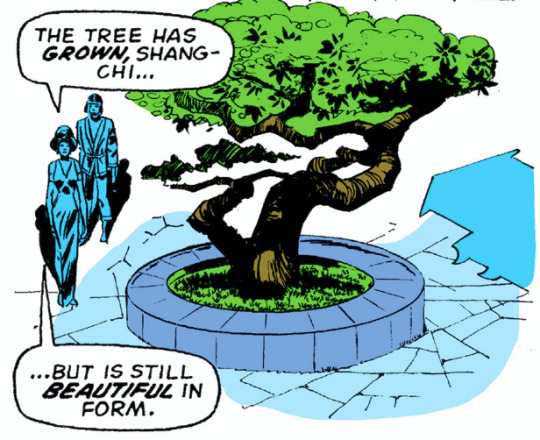

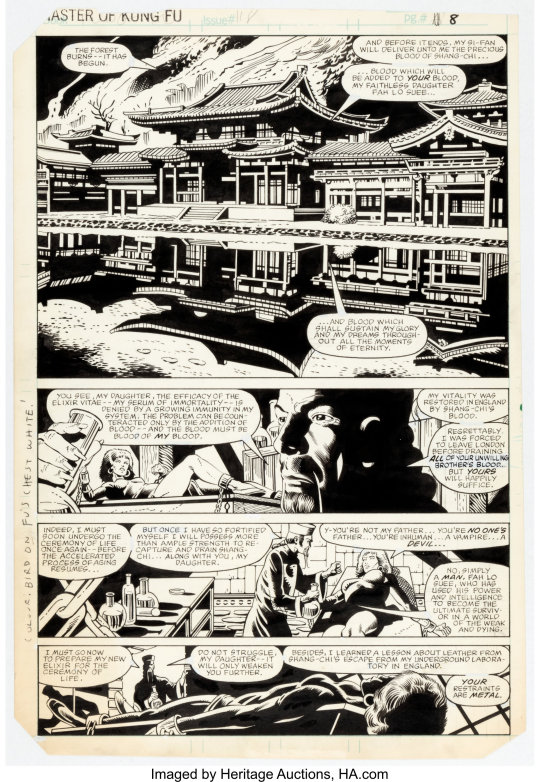

Master of Kung Fu #28 (Moench/Wilson, Hannigan, & Bradford, May 1975). Her motivations are murkier, but Fah Lo Suee still poses a philosophical dilemma for her half-brother Shang-Chi.

#marvel#marvel 616#master of kung fu#shang chi#fah lo suee#doug moench#ron wilson#ed hannigan#aubrey bradford

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

honestly im very tired of peoples inability to recognize stereotypes that stem from sax rohmer novels i think white people especially owe it to asian people to do a cursory reading of the premise of fu manchu novels and read the characters are associated with them just so they can get their heads out of their asses and stop blindly reading fu manchu and fah lo suee reskins without any critical thought

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

i accidentally found this on the web and i already know this but fu manchu and his daughter were 100% the inspiration for ra's al ghul and talia.

#fu manchu#ra's al ghul#talia#batman#fah lo suee#terrence granville#the mask of fu manchu#orientalism

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before “Shang-Chi” premieres, here are all my guesses as to the possible secret identity of Awkwafina’s character (because let’s face it, Marvel gave up trying to pretend her character is just a normal civilian):

1) MI6 agent Leiko Wu, who is Shang-Chi’s love interest/ally in the comics

2) Fah Lo Suee, Mandarin’s other daughter and Shang-Chi’s half-sister

3) Member of a secret society dedicated to protecting the Great Protector (the sea dragon)

4) Undercover Ten Rings agent sent to spy on Shang-Chi

5) Undercover agent sent by Michelle Yeoh to protect Shang-Chi from the Ten Rings

6) Wong’s daughter/niece/apprentice

7) If we’re discarding Netflix Marvel canon, then Colleen Wing

8) If we’re REALLY REALLY discarding Netflix Marvel canon, then genderbent/racebent Danny Rand (Iron Fist). Here, she goes by “Danielle ‘Dani’ Rand”.

#awkwafina#katy#shang chi#shang chi and the legend of the ten rings#shang-chi#leiko wu#fah lo suee#the mandarin#wenwu#the great protector#the ten rings#jiang nan#wong#colleen wing#danny rand#iron fist#MCU#marvel#legend of the ten rings#scatlottr#mcu theory#marvel theories

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

cover art of my Master Of Kung Fu doujinshi

Nov 17 2018

#Master Of Kung Fu#Shang Chi#Fu Manchu#Fah Lo Suee#Nayland Smith#Black Jack Tarr#Clive Reston#Leiko Wu#fan art#my art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Lee: A Sinister Centenary - Number 27

Welcome to Christopher Lee: A Sinister Centenary! Over the course of May, I will be counting down My Top 31 Favorite Performances by my favorite actor, the late, great Sir Christopher Lee, in honor of his 100th Birthday. Although this fine actor left us a few years ago, his legacy endures, and this countdown is a tribute to said legacy!

Today’s Subject, My 27th Favorite Christopher Lee Performance: Fu Manchu, from the 1960s “Fu Manchu” Film Series.

Oh, dear…this one’s gonna be awkward…

Okay, so…I think the reasons this one ranks so low are obvious, but let’s focus on the history first. For those who do not know, Fu Manchu was a pulp fiction character and the titular main antagonist of a series of crime thriller stories by author Sax Rohmer. The stories focused on the neverending rivalry between the so-called Devil Doctor and his arch-nemesis, a Scotland Yard detective called Sir Nayland Smith. The character of Fu Manchu is widely regarded as one of the first supervillains ever created; he is, if nothing else, one of the grandfathers of the supervillain, generally lumped in alongside Professor Moriarty from Sherlock Holmes as one of the forerunners to the basic type.

Fu Manchu has appeared onscreen a great (and an unfortunate) number of times, being played in the past by such actors as Boris Karloff, Henry Brandon, and Charlie Chan himself, Warner Oland. In the 1970s, a resurgence in popularity with the character led to a whole series of films, produced and frequently written by Harry Alan Towers, and starring Christopher Lee as the titular villain. Many regard Lee’s Fu Manchu as the best portrayal of the character onscreen, largely due to the number of features he appeared in…though how much that’s really saying is up to debate…

…Sigh…I…guess I can’t ignore the elephant in the room for too long, can I? Very well, let’s get this out of the way: Fu Manchu is NOTORIOUSLY racist as a character. You almost never see him nowadays, and it’s for good reason: Fu Manchu has been one of the most negative influences on Asian culture in America and other Western countries ever created. To be fair – and yes, I’m going to be fair – that was actually kind of the point of the character: the villain was described as “The Yellow Peril Incarnate.” In other words, he’s intended to be the worst nightmare anyone could imagine from that area of fear, and the writer, Sax Rohmer, was well-aware of it when writing.

One also has to give Fu Manchu props, he’s not actually a one-dimensional character: his motivations for his villainy, in the original stories and most adaptations – including Lee’s work – are not as cut and dry as “evil guy from China wants to take over the world.” His reasons are complex, and so is his character: Fu Manchu, in most versions, has a twisted sense of honor and dignity, following a particularly warped but still very much present moral code. He’s also devoted to his family, genuinely loving and caring for his loyal daughter, Fah Lo Suee, and can even be kind and generous under the right circumstances. However…yeah…one look at the character’s visual design alone tells you all you need to know. There’s no avoiding the fact that the character (and the treatment of Asian culture, in general, in the books and most of his appearances in film) is unforgivably prejudiced.

HAVING SAID ALL THAT…it’s telling that Fu Manchu is still one of Lee’s most iconic characters, and for all the awkwardness that comes with him, he’s still a fine villain in his own right. Sophisticated, cold, but with flashes of humor and even occasional grains of sympathy sprinkled throughout his appearances, the seemingly immortal Devil Doctor – using a mixture of arcane magic and cutting-edge science to do battle with his nemeses – wasn’t a character entirely without merit. He was an interesting antagonist, and you can tell Lee tried his hardest to bring more to the character than what others might perceive, making him one of the most threatening and unironically interesting takes on the character put to film. The sad fact is simply that, for all the merits one can find in Lee’s Fu Manchu…he IS still Fu Manchu, and that’s sadly a character name that will always carry a tragic stigma with it. As a result, while I enjoy Lee’s performances and treatment of the role, I don’t think I can rate him too highly in good conscience.

Don’t worry, future entries on this list will be far, FAR less sweat-inducing to discuss.

Tomorrow the countdown continues with My Number 26 choice!

#sinister centenary#christopher lee#happy birthday christopher lee#top 31 christopher lee performances#countdown#list#number 27#may special#fu manchu#films#movies#actor#acting#awkwardness abounds

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

COMIC BOOK REFERENCES & EASTER EGGS - Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021)

The following is a guide to all the comic book references and Easter eggs I’ve spotted in Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings along with any deviations from the source material. Note that owing to the convoluted and complex nature of comic books, I’ve tried to include only the most essential information regarding a character’s history and backstories.

In both media, Shang-Chi is known as an expert martial artist. As revealed in Special Marvel Edition #15 (1973), his comic book incarnation was raised at his father’s fortress in China. He was trained to fight by tutors and his father. At nineteen years of age, he was tasked by his father to assassinate Dr James Petrie (In the film, Shang-Chi is sent to kill the leader of the Iron Gang). After completing this assignment (in actuality Shang-Chi had attacked an android facsimile), he meets MI6 agent Sir Denis Nayland Smith, who reveals to him that his father is a criminal and not the noble man he was led to believe growing up. Shang-Chi returns to his father who confirms what he has learned. With this, Shang-Chi leaves, declaring that they are now enemies, and begins a new life in New York. Notably, this version of the character is half Chinese, with his mother being a White American. In the film, Shang-Chi’s mother, Jiang Li, is of Asian descent.

Wenwu is an amalgamation of two characters from the source material: the Mandarin and Fu Manchu. Though he claims to be a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, the comic book incarnation of the Mandarin was born to an unknown Chinese father and English mother who was a prostitute. In addition to being a superb martial artist and tactician, he possesses ten rings (worn on his fingers; in the film, they’re akin to bracelets), each of which grants him a different power. The ring worn on his right thumb allows him to rearrange matter, the ring on his right index finger can generate a concussive force, the one on his right middle finger enables the Mandarin to create a vortex from the air, the one on his right ring finger produces a disintegration beam, the one on his right little finger generates an area of darkness, the ring worn on his left thumb produces a range of electromagnetic energy, the ring on his left index finger can generate heat and flames, the one on his left middle finger discharges electricity, the one on his left ring finger enhances his psionic energy, and the one on his left little finger generates cold and ice. The Mandarin obtained the objects from the wreckage of a spaceship belonging to the Makluans (also known as Kakaranatharian).

In the comics, Fu Manchu is Shang-Chi’s father. He leads the secret organisation Si-Fan and has several bases around the world including one in Hunan, China. He’s a skilled combatant and has lived an extremely long life due to his consumption of the Elixir Vitae (In the MCU, Wenwu’s longevity is attributed to the ten rings). Fu Manchu was created by English author Sax Rohmer and featured in several novels before Marvel acquired the licence to use the character in their comics. With Marvel no longer having the rights to Fu Manchu, in Secret Avengers #8 (2010) it’s revealed that the character’s real name is Zheng Zu, with Fu Manchu being one of several aliases he’s used throughout the years.

While Xialing is a new character created for the film, Shang-Chi does have many siblings in the comics. The first one we learn about is Fah Lo Suee (another Rohmer creation), Shang-Chi’s half-sister. Although she initially sides with her father, she would go on to oppose him. Fah Lo Suee made her first Marvel Comics appearance in Master of Kung Fu #26 (1975). Then there’s Moving Shadow, Shang-Chi’s younger half-brother, who made his debut in Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu #1 (2002). First appearing in Black Panther #11 (2005) is Kwai Far, Shang-Chi’s sister who was offered as a bride to T’Challa. The story “Brothers and Sisters” (Shang-Chi #1-5, 2020-21)—released during production on Shang-Chi—would reveal the existence of even more siblings: Brother Staff, Shi-Hua/Sister Hammer, Takeshi/Brother Sabre, and Esme/Sister Dagger.

The Golden Daggers club is a reference to the Golden Dagger Sect of the comics, a criminal organisation led by Fah Lo Suee.

The comic book incarnation of Li Ching-Lin/Death-Dealer is an assassin and former MI6 agent who worked for Fu Manchu. He’s an experienced martial artist who wields triple-bladed weapons.

Several characters have used the Razor-Fist moniker in the comics. The first was William Young, who made his debut in Master of Kung Fu #29 (1975). Later, brothers Douglas and William Scott took on the identity. The pair first appeared in Master of Kung Fu #105 (1981). All three Razor-Fists have worked for drug lord Carlton Velcro. As their name implies, each of the Razor-Fists have had one or both their hands replaced with steel blades. The MCU version of Razor Fist, with his connection to the Ten Rings, may be partially based on the Razor Fist from Earth-13116. In this reality, the character is a student at the Ten Rings martial arts school (with the Master of the Ten Rings, Zheng Zu, being the emperor of K’un Lun).

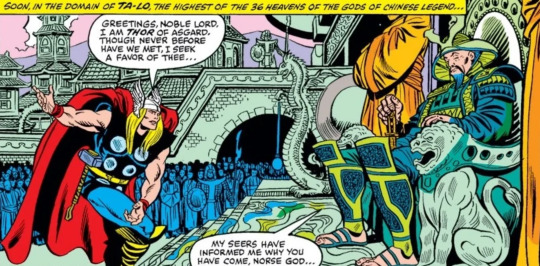

In the comics, Ta-Lo is an extradimensional realm that’s home to the Xian (or Taoist gods). Creatures such as fenghuang, dragons, and haetae also inhabit the dimension. It made its first appearance in Thor #301 (1980).

In the film, the creature trapped in Ta Lo is referred to as the Dweller-in-Darkness. The comic book incarnation of the Dweller-in-Darkness originates from the Everinnye dimension and exists only as a head (though does use a robotic body). The Dweller-in-Darkness has the ability to cause others to feel fear, which he feeds off, making him more powerful.

There are also several MCU Easter eggs. The Blip is referenced on a poster while the Snap is alluded to by one of Shang-Chi’s friends. The street vendor from Spider-Man: Homecoming is a passenger on the bus when Shang-Chi fights Razor Fist. The Abomination (who now appears more reptilian per his comic book counterpart) fights Wong at the Golden Daggers club. Other contestants at the club include an Extremis soldier and an Asian Black Widow (we find out that her name is Helen). Wenwu watches footage of Tony Stark being held captive by the Ten Rings (taken from Iron Man). Wenwu holds Trevor Slattery prisoner having broken the actor free from Seagate Prison in All Hail the King. Shang-Chi meets Bruce Banner and Captain Marvel in the mid-credits scene.

Like the Facebook page.

Follow on Instagram.

Get the books: Phase One | Phase Two | Phase Three

Listen to the podcast: Anchor | Breaker | Google Podcasts | Spotify

#Shang-Chi#Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings#Marvel#Marvel Studios#MCU#Marvel Cinematic Universe#Easter eggs#Wenwu#Wong#Mandarin#Fu Manchu#Ten Rings#Ta Lo#Xialing

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

tips for choosing a Chinese name for your OC when you don’t know Chinese

This is a meta for gifset trade with @purple-fury! Maybe you would like to trade something with me? You can PM me if so!

Choosing a Chinese name, if you don’t know a Chinese language, is difficult, but here’s a secret for you: choosing a Chinese name, when you do know a Chinese language, is also difficult. So, my tip #1 is: Relax. Did you know that Actual Chinese People choose shitty names all the dang time? It’s true!!! Just as you, doubtless, have come across people in your daily life in your native language that you think “God, your parents must have been on SOME SHIT when they named you”, the same is true about Chinese people, now and throughout history. If you choose a shitty name, it’s not the end of the world! Your character’s parents now canonically suck at choosing a name. There, we fixed it!

However. Just because you should not drive yourself to the brink of the grave fretting over choosing a Chinese name for a character, neither does that mean you shouldn’t care at all. Especially, tip #2, Never just pick some syllables that vaguely sound Chinese and call it a day. That shit is awful and tbh it’s as inaccurate and racist as saying “ching chong” to mimic the Chinese language. Examples: Cho Chang from Harry Potter, Tenten from Naruto, and most notorious of all, Fu Manchu and his daughter Fah lo Suee (how the F/UCK did he come up with that one).

So where do you begin then? Well, first you need to pick your character’s surname. This is actually not too difficult, because Chinese actually doesn’t have that many surnames in common use. One hundred surnames cover over eighty percent of China’s population, and in local areas especially, certain surnames within that one hundred are absurdly common, like one out of every ten people you meet is surnamed Wang, for example. Also, if you’re making an OC for an established media franchise, you may already have the surname based on who you want your character related to. Finally, if you’re writing an ethnically Chinese character who was born and raised outside of China, you might only want their surname to be Chinese, and give them a given name from the language/culture of their native country; that’s very very common.

If you don’t have a surname in mind, check out the Wikipedia page for the list of common Chinese surnames, roughly the top one hundred. If you’re not going to pick one of the top one hundred surnames, you should have a good reason why. Now you need to choose a romanization system. You’ll note that the Wikipedia list contains variant spellings. If your character is a Chinese-American (or other non-Chinese country) whose ancestors emigrated before the 1950s (or whose ancestors did not come from mainland China), their name will not be spelled according to pinyin. It might be spelled according to Wade-Giles romanization, or according to the name’s pronunciation in other Chinese languages, or according to what the name sounds like in the language of the country they immigrated to. (The latter is where you get spellings like Lee, Young, Woo, and Law.) A huge proportion of emigration especially came from southern China, where people spoke Cantonese, Min, Hakka, and other non-Mandarin languages.

So, for example, if you want to make a Chinese-Canadian character whose paternal source of their surname immigrated to Canada in the 20s, don’t give them the surname Xie, spelled that way, because #1 that spelling didn’t exist when their first generation ancestor left China and #2 their first generation ancestor was unlikely to have come from a part of China where Mandarin was spoken anyway (although still could have! that’s up to you). Instead, name them Tse, Tze, Sia, Chia, or Hsieh.

If you’re working with a character who lives in, or who left or is descended from people who left mainland China in the 1960s or later; or if you’re working with a historical or mythological setting, then you are going to want to use the pinyin romanization. The reason I say that you should use pinyin for historical or mythological settings is because pinyin is now the official or de facto romanization system for international standards in academia, the United Nations, etc. So if you’re writing a story with characters from ancient China, or medieval China, use pinyin, even though not only pinyin, but the Mandarin pronunciations themselves didn’t exist back then. Just... just accept this. This is one of those quirks of having a non-alphabetic language.

(Here’s an “exceptions” paragraph: there are various well known Chinese names that are typically, even now, transliterated in a non-standard way: Confucius, Mencius, the Yangtze River, Sun Yat-sen, etc. Go ahead and use these if you want. And if you really consciously want to make a Cantonese or Hakka or whatever setting, more power to you, but in that case you better be far beyond needing this tutorial and I don’t know why you’re here. Get. Scoot!)

One last point about names that use the ü with the umlaut over it. The umlaut ü is actually pretty critical for the meaning because wherever the ü appears, the consonant preceding it also can be used with u: lu/lü, nu/nü, etc. However, de facto, lots of individual people, media franchises, etc, simply drop the umlaut and write u instead when writing a name in English, such as “Lu Bu” in the Dynasty Warriors franchise in English (it should be written Lü Bu). And to be fair, since tones are also typically dropped in Latin script and are just as critical to the meaning and pronunciation of the original, dropping the umlaut probably doesn’t make much difference. This is kind of a choice you have to make for yourself. Maybe you even want to play with it! Maybe everybody thinks your character’s surname is pronounced “loo as in loo roll” but SURPRISE MOFO it’s actually lü! You could Do Something with that. Also, in contexts where people want to distinguish between u and ü when typing but don’t have easy access to a keyboard method of making the ü, the typical shorthand is the letter v.

Alright! So you have your surname and you know how you want it spelled using the Latin alphabet. Great! What next?

Alright, so, now we get to the hard part: choosing the given name. No, don’t cry, I know baby I know. We can do this. I believe in you.

Here are some premises we’re going to be operating on, and I’m not entirely sure why I made this a numbered list:

Chinese people, generally, love their kids. (Obviously, like in every culture, there are some awful exceptions, and I’ll give one specific example of this later on.)

As part of loving their kids, they want to give them a Good name.

So what makes a name a Good name??? Well, in Chinese culture, the cultural values (which have changed over time) have tended to prioritize things like: education; clan and family; health and beauty; religious devotions of various religions (Buddhism, Taoism, folk religions, Christianity, other); philosophical beliefs (Buddhism, Confucianism, etc) (see also education); refinement and culture (see also education); moral rectitude; and of course many other things as the individual personally finds important. You’ll notice that education is a big one. If you can’t decide on where to start, something related to education, intelligence, wisdom, knowledge, etc, is a bet that can’t go wrong.

Unlike in English speaking cultures (and I’m going to limit myself to English because we’re writing English and good God look at how long this post is already), there is no canon of “names” in Chinese like there has traditionally been in English. No John, Mary, Susan, Jacob, Maxine, William, and other words that are names and only names and which, historically at least, almost everyone was named. Instead, in Chinese culture, you can basically choose any character you want. You can choose one character, or two characters. (More than two characters? No one can live at that speed. Seriously, do not give your character a given name with more than two characters. If you need this tutorial, you don’t know enough to try it.) Congratulations, it is now a name!!

But what this means is that Chinese names aggressively Mean Something in a way that most English names don’t. You know nature names like Rose and Pearl, and Puritan names like Wrestling, Makepeace, Prudence, Silence, Zeal, and Unity? I mean, yeah, you can technically look up that the name Mary comes from a etymological root meaning bitter, but Mary doesn’t mean bitter in the way that Silence means, well, silence. Chinese names are much much more like the latter, because even though there are some characters that are more common as names than as words, the meaning of the name is still far more upfront than English names.

So the meaning of the name is generally a much more direct expression of those Good Values mentioned before. But it gets more complicated!

Being too direct has, across many eras of Chinese history, been considered crude; the very opposite of the education you’re valuing in the first place. Therefore, rather than the Puritan slap you in the face approach where you just name your kid VIRTUE!, Chinese have typically favoured instead more indirect, related words about these virtues and values, or poetic allusions to same. What might seem like a very blunt, concrete name, such as Guan Yu’s “yu” (which means feather), is actually a poetic, referential name to all the things that feathers evoke: flight, freedom, intellectual broadmindness, protection...

So when you’re choosing a name, you start from the value you want to express, then see where looking up related words in a dictionary gets you until you find something that sounds “like a name”; you can also try researching Chinese art symbolism to get more concrete names. Then, here’s my favourite trick, try combining your fake name with several of the most common surnames: 王,李,陈. And Google that shit. If you find Actual Human Beings with that name: congratulations, at least if you did f/uck up, somebody else out there f/ucked up first and stuck a Human Being with it, so you’re still doing better than they are. High five!

You’re going to stick with the same romanization system (or lack thereof) as you’ve used for the surname. In the interests of time, I’m going to focus on pinyin only.

First let’s take a look at some real and actual Chinese names and talk about what they mean, why they might have been chosen, and also some fictional OC names that I’ve come up with that riff off of these actual Chinese names. And then we’ll go over some resources and also some pitfalls. Hopefully you can learn by example! Fun!!!

Let’s start with two great historical strategists: Zhuge Liang and Zhou Yu, and the names I picked for some (fictional) sons of theirs. Then I will be talking about Sun Shangxiang and Guan Yinping, two historical-legendary women of the same era, and what I named their fictional daughters. And finally I’ll be talking about historical Chinese pirate Gan Ning and what I named his fictional wife and fictional daughter. Uh, this could be considered spoilers for my novel Clouds and Rain and associated one-shots in that universe, so you probably want to go and read that work... and its prequels... and leave lots of comments and kudos first and then come back. Don’t worry, I’ll wait.

(I’m just kidding you don’t need to know a thing about my work to find this useful.)

ZHUGE Liang is written 諸葛亮 in traditional Chinese characters and 诸葛亮 in simplified Chinese characters. It is a two-character surname. Two character surnames used to be more common than they are now. When I read Chinese history, I notice that two character surname clans seem to have a bad habit of flying real high and then getting the Icarus treatment if Icarus when his wings melted also got beheaded and had the Nine Familial Exterminations performed on his clan. Yikes. Sooner or later that'll cost ya.

But anyway. Zhuge means “lots of kudzu”, which if you have been to the American south you know is that only way that kudzu comes. Liang means “light, shining” in the sense of daylight, moonlight, etc; and from this literal meaning also such figurative meanings as reveal or clear. (I’m going to talk about words have a primary and secondary meaning in this way because I think it’s important for understanding. It’s just like how in English, ‘run’ has many meanings, but almost of all them are derived from a primary meaning of ‘to move fast via one’s human legs’, if I can be weird for a moment. “Run” as in “home run” comes from that, “run” as in “run in your stocking” comes from that, “run” as in “that’ll run you at least $200″ comes from that. You have to get it straight which is the primary meaning, which is the one that people think of first and they way they get to the secondary meaning.)

“Light” has a similar “enlightenment” concept in Chinese as in English, so the person who chose Zhuge Liang’s name—most likely his father or grandfather—clearly valued learning.

I named my fictional son for Zhuge Liang Zhuge Jing 京. The value or direction I was coming from is that Zhuge Liang has come to the decision that he has to nurture the next generation for the benefit of the land, that he has to remain in the world in a way that he very much did not want to do when he himself was a young man. In this alternate universe, Liu Bei has formed a new Han dynasty and recaptured Luoyang, so when Zhuge Liang’s son is then born he chooses this name Jing which means literally “capital”. This concrete name is meant as an allusion to a devotion to public service and to remaining “central”. After I chose this name, I discovered that Zhuge Liang actually has a recorded grandson named Zhuge Jing with this same character.

above, me, realizing I picked a good name

ZHOU Yu is written 周瑜 in both simplified and traditional Chinese characters.

The surname Zhou was and remains a very common Chinese surname whose original meaning was like... a really nice field. Like just the greatest f/ucking field you’ve ever seen. “Dang, that is a sweet field” said an ancient Chinese farmer, “I’m gonna make a new Chinese character to record just how great it is.” And then it came to mean things along the line of complete and thorough.

Yu means the excellence of a gemstone--its brilliance, lustre, etc, as opposed to its flaws. It is not a common word but does appear in some expressions such as 瑕不掩瑜 "a flaw does not conceal the rest of the gemstone's beauty; a defect does not mean the whole thing is bad".

Zhou Yu has gone down in history for being not only smart but also artistic and handsome. A real triple threat. And this name speaks to a family that valued art and beauty. It really does suit him.

Zhou Yu had two recorded sons but in my alternate history I gave him four. I borrowed the first one’s name from history: Xun 循, follow. Based on this name, I chose other names that I thought gave a similar sense of his values: Shou 守, guard; Wen 聞, listen. The youngest one I had born when he already knew he was dying, and things had not been going well generally; therefore I had him give him the name Shen 慎, which means “careful, cautious”.

SUN Shangxiang 孫尚香 is one of several names that history and legend give for a sister of w//arlord-king Sun Quan who was married to a rival w//arlord named Liu Bei in a marriage which, historically, uh, didn’t... didn’t go all that well. In my alternate history it goes well! You can’t stop me, I’ve already done it!

The surname Sun means “grandson” and the given name components are Shang mean “values, esteems” and Xiang “scent” which we can combine into meaning something like “precious perfume”. A lot of the recorded names for women in this era (a huge number didn’t have any names recorded, a problem in itself) seem to me to be more concrete, to contain more objects, to be more focused on affection, less focused on hopes and dreams. This makes sense for the era: you love your daughters (I HOPE) but then they get married and leave you. You don’t have long term plans for them because their long term belongs to another clan.

I gave her daughter by Liu Bei the name Liu Yitao 劉義桃. Yi 義 meaning righteousness, rectitude and 桃 meaning... peach. Okay, okay, I know "righteous peach" sounds damn funny in English, but the legendary oath in the peach garden, the "oath of brotherhood" is called in Chinese 結義 "tying righteousness" and the peach garden is, uh, a peach garden. I also give her the cutesy nickname Taotao 桃桃 which you could compare to “Peaches” or “Peachy”. Reduplication of a character in a two-character name is a classic nickname strategy in Chinese.

GUAN Yinping 關銀屏/关银屏 is a “made up” (scare quotes because old legends have their own kind of validity, fight me) name for a historical daughter of Guan Yu. Guan means “to close (a door)”. Yin means “silver” and ping means “a screen, to hide” and according to the legend, her father’s oath brother Zhang Fei named her after a silver treasure. So here again we see a name for a woman that completely lacks the kind of aspirations we see in male names. Who would have an aspiration for a daughter?

My fictional characters, that’s who. I named her daughter Lu Ruofeng 陸若鳳/陆若凤, Ruo (like the) Feng (phoenix), based on a quote from a Confucian text about what one should try to be during both times of chaos and times of good government. I portray her father as a devoted Confucian scholar, so that was another factor for why I looked to Confucian texts for a source of a name.

Modern parents also now have big dreams for their daughters :’) and so modern girls receive names that are far more similar to how boys are named.

GAN Ning 甘寧/甘宁 is a great example of a person whose name does not suit him. Gan 甘 depicts a tongue and means “sweet”, and Ning 寧 which shows a bowl and table and heart beneath a roof means “peaceful”. Which, it would be hard to come up with a name for this guy, a ruthless pirate turned extremely effective general:

that is less suitable than essentially being named “Sweet Peace”.

And when he was an adult, his style name—a name that Chinese men used to be given when they turned 20 (ie became adults) by East Asian reckoning—indeed reflects that. Choosing your own style name was widely considered to be crass. I absolutely think that Gan Ning chose his own style name; he was that kind of a guy. And the name he chose! Xingba 興霸/兴霸! I’ve never seen another style name like it. It means, basically, “thriving dominator”! Brand new official adult Gan Ning treats his style name like he’s picking his Xbox gamer tag and he picks BadassBoss69_420, that’s what this style name is like to me. Except, you know, he had almost certainly killed many hundreds of people by the time he was nineteen, so, uh, it wouldn’t be a wise idea to make fun of his name to his face.

In my fictional version of his life, he married a woman whose father was the exception to the “parents love their children” rule and who named his daughter Pandi 盼第 “expecting a younger brother”, which is a classic “daughters ain’t shit, I want a son” name. Real and actual Chinese women have been given this shitty name and ones like it.

Because Gan Ning had an ironically placid name, I also gave his daughter the placid single character name Wan 婉, which means “gentle, restrained”, as a foil to her wild personality.

So there are a bunch of examples of some historical characters and some OCs and how I chose their names. “But wait, all that was really cool, but how can I do that? You can read Chinese, I can’t!”

I originally had a bunch of links here to dictionaries and resources but Tumblr :) wouldn’t let the post show up in tag search with all the links :) :) :) so you need to check the reblogs of this post to see my own reblog; that reblog has all the links. I’M SORRY ABOUT THIS. Here are a list of the sites without the links if you want to Google them yourself.

MDBG - an open source dictionary - start here

Wiktionary - don’t knock it til you try it

iCIBA (they recently changed their user interface and it’s much less English-speaker friendly now but it’s still a great dictionary)

Pleco (an iOS app, maybe also Android???) contains same open source dictionary as MDBG and also its own proprietary dictionary

Chinese Etymology at hanziyuan dot net

You search some English keywords from the value you want, and then you see what kind of characters you get. You should take the character and then reverse search, making sure that it doesn’t have negative words/meanings, and similar. Look into the etymology and see if it has any thematic elements that appeal to what you’re doing with the character--eg a fire radical for a character with fire powers.

And then, like I mention before, when you have got a couple characters and you think “I think this could be a good name”, you go to Google, you take a very common surname, you append your chosen name—don’t forget to use quotation marks—and you see what happens. Did you get some results? Even better, did you get lots of results? Then you’re probably safe! No results does not necessarily mean your name won’t work, but you should probably run it by an Actual Chinese Native Speaker at that point to check. Also, remember, as I said at the beginning, sometimes people have weird names. If you consciously decide “you know what, I think this character’s parents would choose a weird name”, then own that.

THINGS YOU SHOULD PROBABLY IGNORE!

Starting in relatively recent history (not really a big thing until Song dynasty) and continuing, moreso outside of mainland China, to the modern day, there is something called a generation name component to a name. This means that of a name’s two characters, one of the characters is shared with every other paternal line relative of that person’s generation; historically, usually only boys get a generation name and girls don’t. (Chinese history, banging on pots and pans: DAUGHTERS AIN’T SHIT AND DON’T FORGET IT!) “Generation” here means everyone who is equidistant descendant from some past ancestor, not necessarily that they are exactly the same age. For example, all of ancestor’s X’s sons share the character 一 in their names, his grandsons all have the character 二,great-grandsons 三, great-great-grandsons 四 (I just used numbers because I’m lazy). By the time you get to great-great-grandson, you might have some that are forty years old and some that are babies (because of how old their fathers were when they were conceived), but they are still the same generation.

In some clans, this tradition goes so far as to have something called a name poem, where the generations cycle, character by character, through a poem that was specifically written for this purpose and which is generally about how their clan is super rad.

If you want to riff off of this idea and have siblings or paternal cousins share a character in their names, ok, but it genuinely isn’t necessary. Anyone with a single character name obviously doesn’t have one of these generation names, and by no means does every person with a two character name (especially female) have a generation name. If you’re doing an OC for an ancient Chinese setting (certainly anything before the year about 500), you shouldn’t use these generation names because it wasn’t a thing. Also, in a modern setting, even if such a generation name or name poem exists, it’s not like there is any legal requirement to use it (though there may be family pressure to do so).

As a further complication, some parents do the shared character thing among their children without it actually being a generation name per se because it isn’t shared by any cousins. Or, they have all their children (or all their children of the same gender) share a radical, which is a meaning component in a Chinese character.

If someone does have one of these shared character names, then their nickname will never come from that shared character; either they will be called by the full name or by some name riffing off of the character that is not shared. For example, I knew a pair of sisters called Yuru and Yufei with the same first character; the first sister went by her English name in daily life (even when speaking Chinese) while the second sister was called Feifei.

tl;dr If you don’t already know Chinese, consider generation names an extra complication for masochists only. Definitely not required for modern characters.

Fortune telling is another thing that I think you should either ignore or wildly make up. Do you know what ordinary Chinese people who want to choose a lucky name for their child do? They hire someone to work it out. This is not some DIY shit even if you are deeply immured in the culture. There are considerations of the number of strokes, the radicals, the birth date, the birth hour. You’re the god of your fictional universe, so go ahead and unilaterally declare that your desired names are lucky or unlucky as suits the story if you want to.

MILK NAMES

In modern times, babies get named right away, if for no other reason that the government requires it everywhere in the world for record keeping purposes.

However, in traditional times, Chinese people did not give babies a permanent name right away, instead waiting until a certain period of time had passed (3 months/100 days is a classic).

What do you call the baby in the meantime? A milk name 乳名, which your (close, older than you) family may or may not keep on using for you until such time as you die, just so that you remember that you used to be a funny looking little raisin that peed on people.

This kind of name is almost always very humble, sometimes to the point of being outright insulting. This is because to use any name on your baby that implies you might actually like the little thing is tempting Bad News. Possible exception: sometimes a baby would receive a milk name that dedicated it to some deity. In this case, I guess you’re hoping that deity will be flattered enough to take on the job of shooing away all the other spirits and things that might be otherwise attracted to this Delicious Fresh Baby.

Because milk names were only used by one’s (older) family and very close family friends of one’s parents/grandparents, most people’s milk names are not recorded or known, with some notable exceptions. Liu Shan, the son of Liu Bei, who as a baby was rescued by Zhao Yun during the Shu forces retreat from Changban. Perhaps because his big debut in history/legend was as a baby, he is well-known for his milk name A-Dou 阿斗, which means, essentially, Dipper.

If you’re writing a story, you really only need to worry about a milk name for your character if it’s a historical (or pseudohistorical) setting, and even then only if the character either makes an appearance as a small infant or you consciously decide to have them interact with characters who knew them well as a small child and choose to continue using the milk name. Not all parents, etc who could use the milk name with a youth or an adult actually did so.

Here are some milk names I’ve come up with in my fiction: Little Mouse/Xiaoshu 小鼠 for a girl, Tadpole/Kedou 蝌蚪 for a boy, and Shouty/A-Yao 阿吆 for a boy. In the first two cases the babies were both smol and quiet (as babies go). The last one neither small nor quiet, ahahaha. 蔷蔷 Qiangqiang, which is a pretty enough name meaning “wild rose” (duplication to make it lighter), except the baby is a boy, so this is the typical idea that making a boy feminine makes him worth less, which, yikes, but also, historically accurate. Also Xiaohei 小黑 “Blackie” for a work that I will probably never publish because I don’t ever see myself finishing it. I might recycle it to use on another story.

Here are some more milk names I came up with off the cuff for a friend that wanted an insulting milk name. They ended up not using any of these, so feel free to use, no credit necessary. Rongzi 冗子 “Unwanted Child”; Xiaochou 小丑 “Little Ugly”; A-Xu 阿虛 “Empty”; Pangzhu 胖豬 “Fat Pig”; Shasha 傻傻 “Dummy”.

PITFALLS!

Chinese has a lot of homophones. Like, so many, you cannot even believe. That means the potential for puns, double meanings, etc, is off the charts. And this can be bad, real real bad, when it comes to names. It is way too easy to pick a name and think to yourself “wow, this name is great” and then realize later that the name sounds exactly the same as “cat shit” or something even worse.

Some Chinese families live the name choosing life on hard mode because their surname is itself a homonym that can make almost any name sound bad. I’m speaking of course of the poor Wus and Bus of the world. You see Wu may have innocuous and pleasant surnames associated with it, but it also means “without, un-”. (Bu is similar, sounds like “no, not”.) Suddenly, any pleasant name you give your kid, your kid is NOT that thing.

This means picking a name that is pleasant in itself yet also somehow also pleasant when combined with Wu. So you might pick a character with a sound like Ting, Xian, Hui, or Liang - unstopping, unlimited, no regrets, immeasurable. A positive negative name, a kind of paradox. Like I said, this is naming on hard mode.

If you are naming an ancient character, I am going to say in my opinion you should ignore all considerations of sound, because reconstruction of ancient Chinese pronunciations is on some other, other level of pedantic and you just don’t need to do that to yourself.

For modern characters, however, an attractive name, in general, should be a mix of tones and a mix of sounds. As a non-Chinese speaker, basically this means especially if you go for a two character given name, having all three characters start with the same sound, or end with the same sound, can sound kind of tongue twistery and thus silly/stupid. That doesn’t mean that such names never exist, and can in some cases even sound good (or at least memorable), but how likely is it that you’ve found the exception? Not very. (Two out of three having repetition isn’t bad. It’s three out of three you have to be careful of. Something like Wang Fang or Zhou Pengpeng is probably fine; it’s something over the top like Guan Guangguo or Li Lili you want to avoid.)

Just like the West (sigh), in the modern Sinosphere it is widely acceptable for girls to have masculine names but totally unacceptable for boys to have feminine names. If you see the radical 女 which means woman, don’t choose that character for a boy, at least if you’re trying to be realistic. Now Chinese ideas of masculinity doesn’t have the same boundaries as Western ideas, but if you want to play around in those boundaries, you gotta do that research on your own; you’ve left what I can teach you in this already entirely too long tutorial.

Don’t name a character after someone else in story, or after a famous person. In some/many Western cultures, and actually in some Eastern cultures too (Japan is basically fine with this, for example), naming a baby the same name as someone else (a relative, a saint, a famous person, etc), is a respected and popular way to honour that person.

But not in Chinese culture, not now, not a thousand years ago, not two thousand years ago. (Disclaimer: I bet there is some weird rare exception that, eventually, somebody will “gotcha” me with. I am prepared to be amazed and delighted when this occurs.)

Part of this is because of a fundamentally different idea in Chinese culture vs many other cultures about what is valuing vs disrespecting with regard to personal names. The highest respect paid in Chinese history to a category of personal names is to the emperor, and what would happen there is that it would be under name taboo, a very serious and onerous custom where you not only have to not say the emperor’s name, but you can’t say anything that sounds the same as the emperor’s name.

Did I mention that this is in the language of CRAZY GO NUTS numbers of homonyms? The day-to-day troubles caused by observing name taboo were so potentially intense that there are even instances where, before ascending to the imperial throne, the emperor-to-be would change his name to something that was easier to observe taboo about!

So you see this is an attitude that says: if you want to honour and show respect to somebody, you don’t speak their name.

As the highest person in the land, only the emperor gets this extreme level of avoidance, but it trickles down all through society. You can’t use the personal names of people superior to you. Naming a baby after someone inherently throws the hierarchy out of whack. Now you have a young baby with the same name as a grown adult, or even a dead person, who is due honour from their rank in life. People who would not be permitted to use the inspiration’s name may now use that name because they are superior to the baby who received the name! This would mean that hierarchy was not being preserved, and oh my heaven, is there anything worse than hierarchy not being preserved? All of Chinese History: Noooooo!

Now. As an author—and I hope to God no one is using my Chinese name guide as a resource to name an actual human baby because I can’t take that kind of pressure—you can use the names of characters to inspire the names of other characters, in the following way.

Remember that I said that the key, the starting point, to naming someone in Chinese is to start from a value. Okay. So what you do, if as the author you want to draw a thematic connection between two fictional characters, is take the Inspiration character’s name, think about what the value is that caused that name to be chosen, and then go from that value to choose the New Character’s name.

If you’ll recall what I said about Gan Ning and his baby Wan, this is exactly the approach I took. Gan Ning had a placid single character name that belied his violent and outrageous personality; I chose a placid single character name for his similarly wild daughter to make them thematically similar. As an author, I named his baby after him. But within the context of the story, she was not named after him. Does the distinction make sense?

Values also run in families for obvious reasons. It’s very common to look at a family tree and see lots of names that follow a kind of theme and give you a sense that, eg, this family is rather low class and uneducated; this family is very erudite but a bit too fussy about it; this family is really big on Confucianism. So yes, as an author, looking to other characters for inspiration is not a bad idea.

Remember, a lot of times, as an author, you can and even should kick realism to the curb sometimes. If you want to make some Ominous Foreshadowing that Character A’s name is something to do with fire but! They name their child something to do with water and therefore they are destined to clash with their own offspring, gasp, you can do that kind of thing because you are the god of your universe. Relish your power.

Do you have any more questions? Feel free to send a PM or an ask. I hope this was helpful! Go forth and name your Chinese OCs with slightly more confidence!

Edit 22 April 2019: I added some more sections (fortune telling, Milk Names, and taboo on naming after people). I also need to overhaul the entirety of the previous to emphasize that even thought I thoughtlessly used “Chinese” as if it was synonymous with “Han”, there are non-Han Chinese and they can have very different naming customs. Mea culpa.

#dynasty warriors#chinese history#mandarin#writing#resources#tutorial#three kingdoms#ocs#how to do it#meta#trade#chinese language#writing tips#long post#names#onomastics#chinese names#1k#5k#10k#25k

38K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Original Gene Day page from Master of Kung Fu #118 (Marvel Comics, 1982) featuring Fu Manchu, who needs Shang-Chi's blood to stay young, and is willing to risk the lives of his children, including his daughter, Fah Lo Suee, to get it.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

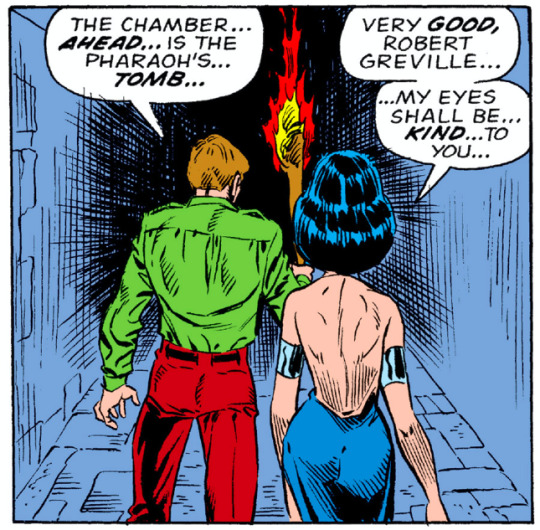

Master of Kung Fu #26 (Moench/Pollard, Mar 1975). Xu Xialing isn't exactly Fah Lo Suee, Shang-Chi's seductive half-sister. An expedition to Egypt turns into a deadly family reunion.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I do think Fu Manchu reskins are just as racist and I think that more people need to do research about what are the stereotypes that are from Sax Rohmer novels because sometimes i see yall talk about like talia al ghul arcs that are directly lifted from them and i get a lil concerned like obv im not reading them cuz im not a dc girlie but its alarming how yall just do not know them and just keep praising them

A good example I'm more familiar with is in Agents of Atlas v1 there is a really good subversion of the fu manchu trope but in agents of atlas v2 Suwan is literally the Dragon Lady stereotype that comes from Fah Lo Suee (that isn't to say that suwan was not in a way another stereotype from the same novels originally where she is more like Karamaneh but often both of those characters are combined and confused in adaptions sp she owes to both)

I'm not trying to attack anyone about this because the insidious nature of the Sax Rohmer novels is that they are so integrated in western culture that theyre everywhere. Like people will compare talia with Shang-chi's sister in the mcu movie without knowing that they come from the same character and its frustrating to me that people just dont know so they dont avoid the stereotype

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artstuff

I have only seen two of the horror movies released the year I was born. The Last Man on Earth was one. The Horror of Party Beach was the other. Interesting, both movies feature untraditional vampires. Last Man’s vampires are dead humans who have been reanimated by a virus. The Party Beach‘s vampires are the corpses of drowned fishermen who have been reanimated by radioactive waste and transformed into weird fishman zombies. Last Man stars Vincent Price and helped to inspire The Night of the Living Dead and therefore a ridiculous number of zombie movies, comics and tv shows. Party Beach features silly looking monsters, a surprising amount of gore and is generally pretty dumb.

Guess which movie has infested my imagination?

Yeah.

The monsters in The Horror of Party Beach are atomic fishman zombie vampires, mutated sea anemonies that have somehow animated human skeletons. The costumes in the movie are inspiring. Inspiring like – “I’ve got a better idea!” So over the years I’ve done a few illustrations featuring redesigns of the critters. The following gallery collects a sampling of the best of them.

I’m not the only person to have put way too much thought into making these beasties look cool.

This is Dope Pope’s Horror of Party Beach Gallery. My icthyozombies are meant to be odd combinations of oceanic life in humanoid form. Dope Pope’s design is streamlined and naturalistic. I applaud his results!

Story Seed #36

The Memoirs of Doctor Fu Manchu

I like Fu Manchu. Not Fu Manchu as he has been depicted. That Fu Manchu is a horrible racist caricature. There’s a version of Fu Manchu in my imagination who has a much more interesting story than the one presented so far.

My direct exposure to the character is limited to his appearances as the main villain (and father to the main character) in the Master of Kung Fu comic and to his appearance (as portrayed by Boris Karloff) in the movie The Mask of Fu Manchu. I’ve haven’t read the original novels. I haven’t watched any of the other films. The Fu Manchu in Master of Kung Fu is a villain who got tiresome due to repeated exposure. He showed up and got defeated. Over and over. The Fu Manchu and his daughter, Fah Lo Suee, in Mask are the only characters having fun. I like to see villains who enjoy their work.

By the time I saw Mask I’d also gotten an education in European/Chinese relations, particularly in the imperialist villainy committed by European nations against the Chinese. Fu Manchu’s gripes against the British had historic justification. Having the British characters mostly be portrayed as smug assholes didn’t help me sympathize with them. And knowing that, at the time the movie was filmed, I was expected to sympathize with their smug assholishness really doesn’t help me sympathize with Western imperialist culture.

Fu Manchu is a genius. He’s lived many lifetimes. He’s a scientist and a mystic. He’s a man of his word. He’s got his own secret cults and organizations. He’s got loyal and treacherous family members to aid and oppose him. Imagine the stories he could tell. Imagine how those stories would read if told from his point of view. The name Fu Manchu is still trademarked by the Sax Rohmer estate but the original novels, and therefore the character himself, are in public domain. One could write a novel from the Good Doctors perspective. One probably couldn’t title it The Memoirs of Dr. Fu Manchu without getting into legal trouble with Rohmer’s lawyers.

And, in this, the second decade of the 21st Century, one couldn’t publish The Memoirs of Dr. Fu Manchu without getting a lot of flack from the audience. One could write a brilliant, aware and nuanced portrait of the character and a lot of folks would be pissed off. The name, Fu Manchu, calls up all the prejudice and ignorance of “Yellow Peril” fiction, of “yellowface” performances, of Orientalist fantasy and propaganda. Some characters are products of their time and cannot be revived or reformed. Not by a European writer, no matter how well intentioned. It’s a bad idea.

If there were Asian fans of Fu Manchu, one of them might be able to write the character without being reviled. If. I’ve done quite a few online searches but the only praise I find for the character comes from white guys.

Other Newsletters

Abundance Insider by Peter Diamandis proviides a regular sources of good news about technological advances in the world. Too often our news is a litany of disasters so it’s refreshing to get word of things that are going well, that give a glimpse of an improving civilization.

Lifestuff

I hope you and you and everyone you know are doing well. I’ve got a skewed picture of what’s happening because I’m still working. I don’t have any more to time to look at the news than I did before the crisis. Mail delivery is considered an essential service. So I go to work. I keep my distance from other employees while I’m putting my route together and then the job continues like it has for years. I didn’t see many people during the day before. I don’t see many people now. I keep a greater distance if I have conversations with customers but the conversations are no shorter than previously because they were never long before. When I’m working I’m trying to get done.

Stay safe. Stay healthy. Stay sane. See you next week!

Tuesday Night Beach Party Club #12 Artstuff I have only seen two of the horror movies released the year I was born…

1 note

·

View note

Text

Early prediction for “Shang-Chi”: Awkwafina’s character is later revealed to be an associate of the Mandarin, sent to spy on Shang-Chi. Her whole “I’m just a normal person, here to be your funny sidekick” shtick is all a lie meant to throw the audience off.

(also, just saying, there was a rumor that Awkwafina is actually playing Fah Lo Suee, a Shang-Chi villain, so there MIGHT be some truth to this)

#shang chi#shang chi and the legend of the ten rings#shang-chi#shang chi trailer#mcu shang chi#awkwafina#fah lo suee#mcu speculation#simu liu#the mandarin#mcu mandarin

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shang-Chi was born in the Honan[b] province of China, and is the son of Fu Manchu, the Chinese mastermind who has repeatedly attempted world conquest and had a thirst for blood. His mother was a white American woman genetically selected by his father. Shang-Chi was raised and trained from infancy in the martial arts by his father and his tutors. Believing his father was a benevolent humanitarian, Shang-Chi was sent on a mission to London to murder Dr. James Petrie, who his father claimed was evil and a threat to peace. After successfully assassinating Petrie, he encountered Fu Manchu's archenemy, Sir Denis Nayland Smith, who revealed to Shang-Chi his father's true nature. After confronting his mother in New York City for the truth, Shang-Chi realized that Fu Manchu was evil. Shang-Chi fought his way past Fu Manchu's Si-Fan assassins at his Manhattan headquarters, telling his father that they were now enemies and vowing to put an end to his evil schemes.[15] Shang-Chi subsequently fought his adoptive brother Midnight, who was sent by their father to kill Shang-Chi for his defection,[16] and then encountered Smith's aide-de-camp and MI-6 agent Black Jack Tarr, sent by Smith to apprehend Shang-Chi.[17] After several encounters and coming to trust one another, Shang-Chi eventually became an ally of Sir Denis Nayland Smith and MI-6. Together with Smith, Tarr, fellow MI-6 agents Clive Reston and Leiko Wu, his eventual love interest, and Dr Petrie, who was revealed to still be alive, Shang-Chi went on many adventures and missions, usually thwarting his father's numerous plans for world domination.[18] Shang-Chi would occasionally encounter his half-sister Fah Lo Suee who led her own faction of the Si-Fan, but opposed her attempts to make him a pawn in her own schemes to usurp their father from his criminal empire.[19]

With Smith, Tarr, Reston, Wu and Petrie, he formed Freelance Restorations, Ltd, an independent spy agency based in Stormhaven Castle, Scotland.[20] After many skirmishes and battles, Shang-Chi finally witnessed the death of Fu Manchu.[21] Not long after his father's death, a guilt-ridden Shang-Chi quit Freelance Restorations, cut ties with his former allies, forsook his life as an adventurer, and retired to a village in remote Yang-Tin, China, to live as a fisherman.[22]

0 notes

Text

Marvel Doesn’t Own Movie Rights To Shang-Chi’s Biggest Villain

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings is set to finally introduce Iron Man's most iconic villain, The Mandarin, to the MCU, but Shang-Chi's greatest enemy, Fu Manchu, will be nowhere in sight. Why? Because Marvel no longer owns the rights to the character. Mandarin is replacing Fu Manchu as his primary antagonist and possibly as his father as well.

It was confirmed at SDCC 2019 that Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings will be part of Marvel Studios and Disney's lineup for Phase 4 of the MCU. Directed by Destin Daniel Cretton, the movie stars Chinese-Canadian actor Simu Liu as Shang-Chi, Tony Leung as the Mandarin, and Awkwafina. Shang-Chi will be the first Marvel film to focus on an Asian superhero, too, which has drawn even more attention to the project. In Marvel Comics, Shang-Chi is the Master of Kung Fu and one of Marvel's two most prominent martial arts superheroes, with the other being Iron Fist.

Related: Shang-Chi Star Wears An Asgardians of the Galaxy Shirt

In the movie, Shang-Chi will face off against the Mandarin, a villain who has been teased since the first MCU movie, 2008's Iron Man, with the introduction of a terrorist organization called the Ten Rings. Marvel notoriously faked out audiences with Ben Kingsley's Mandarin impersonator in Iron Man 3, but the Marvel one-shot, All Hail the King, proved that the real Mandarin exists somewhere in the MCU. He'll finally make his long-awaited debut in Shang-Chi, taking the place of the character's comic book arch-rival, Fu Manchu.

Who is Fu Manchu?

Created in 1913 by Sax Rohmer, Dr. Fu Manchu was an evil Chinese criminal mastermind who was often identified by his iconic mustache. Fu Manchu was the leader of a Chinese gang called the Si-Fan. He used the Si-Fan to carry out his dream of returning China to its past glory. His schemes were often thwarted by MI-6, as well as his long-time nemesis, Sir Denis Nayland Smith.

Rohmer featured Fu Manchu as the titular villain of several novels, published between 1913 and 1959. Due to Fu Manchu's popularity, Rohmer's novels were eventually adapted to the big screen. In the early 1970s, Marvel Comics acquired the rights to Fu Manchu from the Rohmer estate and arranged for the character to be used as the main antagonist and father of a new kung fu hero, Shang-Chi. Shang-Chi's comic book series, The Hands of Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu, borrowed a sizable chunk of the supporting cast from the Rohmer novels, but also introduced a few new characters to join Shang-Chi in his quest to defeat Fu Manchu.

In Marvel Comics, Fu Manchu is an immortal criminal genius who is often described by Shang-Chi as the most evil man in the world. He trained Shang-Chi to be an unquestionably loyal instrument of death, but was disappointed when Shang-Chi turned against him. Shang-Chi teamed up with agents of MI-6 to take down Fu Manchu and his criminal empire. Fu Manchu and MI-6 clashed numerous times over the course of the series.

Related: Marvel Was Developing A Shang-Chi Movie Before They Had Iron Man Rights

Marvel Doesn't Have The Rights To Fu Manchu

Marvel's The Hands of Shang-Chi: Master of Kun Fu series had a successful run that lasted from 1974 to 1983. Around the time of the book's cancellation, Marvel's licensing rights to Fu Manchu expired. Since the series was cancelled, Marvel opted not to renew the rights. In the years that followed, Shang-Chi appeared in only a handful of comics as a guest star. Later on, Marvel took an interest in reviving Shang-Chi's story and his battles with Fu Manchu, but they no longer had the rights to use the villain. So the comic book writers avoided mentioning his name.

Using Fu Manchu was an issue even though Rohmer's novels are now in the public domain. According to CBR, the Rohmer estate trademarked the "Fu Manchu" name, which kept Marvel from using it in marketing. Eventually, this problem was solved when a Secret Avengers comic renamed him "Zheng Zu" and declared "Fu Manchu" to be an alias.

To this day, Marvel still doesn't have the rights to use Fu Manchu, and now that they have found a way around this problem, it's highly unlikely that this will change, despite the fact that it also keeps them from using other Rohmer creations as well. Sir Denis Nayland Smith, Dr. Petrie, and Fu Manchu's daughter, Fah Lo Suee, all appeared in Master of Kung Fu but have been ignored ever since the licensing rights expired.

Related: Who Is Shang-Chi? Marvel's New Asian Superhero Explained

Marvel Doesn't Want Him Anyway

Marvel not owning the rights to a hero's greatest villain may look like an enormous obstacle when it comes to giving him a solo movie, but this isn't the case for Fu Manchu and Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings. Fu Manchu isn't in the same category as Spider-Man, the X-Men, and the Fantastic Four, or other big-name properties that Marvel fans have wanted to see in the MCU. In fact, Marvel Studios wouldn't use Fu Manchu in a Shang-Chi movie even if the character's rights weren't a problem.

When Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings was confirmed at SDCC 2019, some Chinese fans reacted in anger over Shang-Chi's connection to Fu Manchu, a character who many feel is an insulting caricature of Chinese culture. It's been said that his appearance, personality, and plan to bring China back to its ancient glory are offensive to Chinese. Fu Manchu was a reflection of "Yellow Peril", and the idea that East Asia was a threat to the western world. This response to Fu Manchu is actually nothing new. The controversy surrounding Fu Manchu goes all the way back to 1932, when the Chinese embassy issued a complaint about MGM's The Mask of Fu Manchu, a movie which saw Fu Manchu on a mission to kill white men and take their women.

Shang-Chi creator Jim Starlin confirmed that he quit writing Shang-Chi's comics after being "horrified" by the Fu Manchu books. Starlin also hopes that Fu Manchu will be kept out of the movie, and this appears to be exactly what Marvel intends to do. Fu Manchu is problematic for Marvel Studios in more ways than one (considering how important China is to Disney's box office), and since Marvel has already found a perfect replacement in the Mandarin, this is one villain who may never appear in the MCU.

Next: Every Upcoming Marvel Cinematic Universe Movie

source https://screenrant.com/shang-chi-villain-fu-manchu-marvel-movie-rights/

0 notes