#for 1 stylization/simplification

Text

fcgs new design amirite

#critical role#fcg#fresh cut grass#taters does art#simplifying and stylizing everything is so fun#also yes i know the changebringer coin should be in their chest#changed it to a clover#for 1 stylization/simplification#2 bc avandras all lucky iirc#3 excuse to add more hearts#i love shapes a normal amount

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

A set of very conceptual notes I drafted a while back for someone asking for advice on learning to draw humans. I'm entirely self-taught so this is less of a tutorial and more of a very rambling set of general principles I follow and ideas that helped while I was learning. I figured I'd post it in case anyone else could get use out of it!

I also recommend checking out:

Drawing East Asian Faces by Chuwenjie

How to Think When you Draw (lots of good tutorials in this series)

Pose reference sites such as Adorkastock

Transcript and some elaboration under the cut:

Img 1 - Drawing a face

The two most important elements (at least for me) when drawing a face are the outline of the cheek/jaw and the nose*. I often start with a circle to indicate the round part of the skull, then add a straight like and a 'V' to one side [to create the side of the face and the jaw].

The nose creates an easy template for the rest of the face's features to follow (eyebrows at the top of the nose bridge, eyes towards the center of the bridge, ear lines up to eye) and the placement/direction and overlap with other features is a very simple way to indicate dimension.

[A sketch of a face that has been adjusted by moving its parts to create 3 different angles. The following text is underneath:]

-Different 3/4th views can be created just by adjusting the position of and amount of overlap between the facial features.

- The top of the ear usually lines up with the corner of the eye. Think of how glasses are designed [specifically, how the arms run from the eyeline to the ear]

[I go on a tangent in these next few paragraphs]

*One thing I see many artists do - not just beginners - is learn how to draw A Person. As in, one singular person with one set of bodily proportions and one set of facial features. It's an issue that runs a bit deeper than 'same face syndrome' because sometimes these artists can draw more than one face, they're just not very representative of [the diversity present across] real people.

Part of the reason I'm talking more about how to think about approaches to drawing - rather than showing specific how-to's - is because there is no one correct or right way to draw a person. The sooner you allow yourself to explore variety - fat people, old people, people of color, people with [conventionally] 'unattractive' features - the easier it'll be! Artists often draw their own features honestly and without [harmful] caricature, so it's always a good idea to look at art made by the kinds of people you're trying to draw if you're ever unsure about how to handle something.

In general, it's far more important to learn how to interpret a variety of forms than to learn how to replicate the Platonic Ideal of the Human Body.

Img 2 - Stuff that helped me

Jumping into drawing humans (faces or otherwise) straight from photo reference can be overwhelming. The trick is to simplify forms into shapes - but even this concept is sort of abstract and it may be hard to know where to begin.

Good news - Thousands of other artists have already figured it out. [When starting out] I needed to learn from photo reference AND artists I admired in order to improve.

[When looking at stylization you are inspired by] ask yourself: WHY does this simplification work? How can I translate it into a different pose? Instead of copying what you see in a photo reference exactly, try to focus on the general forms first.

My two biggest style inspirations for humans while learning to draw them were Steven Universe and Sabrina Cotugno's art. SU gets a lot of hate [in this instance I was specifically referring to a time on tumblr when the art was knocked for 'losing quality'] but its style does a great job of simplifying anatomy in a way that still portrays a diversity of bodies + features.

[Extremely simplified drawings of Lapis, Steven, and Amethyst]

SU characters are still identifiable- and still read as 'human' - even when reduced to just a few lines!

Img 3 - Things I keep in mind while drawing side profiles

- Eyebrows + eyes close to the 'edge' of the face

- Forehead needs enough room for a brain

- Eye is > shaped from the sides

- Mouth kinda halfway [between the nose and the chin] but closer to the nose

- Skin/fat exists under the jaw [and connects to the neck]

- neck is about one half the width of the whole head

- the back of the skull always sticks out a bit further than you might expect

- Sometimes less is more - contours exist on every face, but drawing them in may make your character seem much older than they're supposed to be. However, it's a good idea to use them when you *want* your character to look old!

These are very general notes- every face is different and has different proportions [and playing around with them creates unique and interesting character designs]

#2023#may 2023#i realized this is pretty nonsensical while transcribing it LOL#feel free to send asks if anything is unclear#but again im not any sort of professional

562 notes

·

View notes

Note

i wanna get better at art but dont know how to start ^^' whats a good way to get into studying anatomy and improving as an artist? tysm 💗 love your art soso much

more art converts 😼 yay!!

i think these asks were sent by different people but they're pretty related + a lot of my advice is the same! so i'll answer these together under the cut (it's so long oh gosh)

ok first of all i'm very flattered that people are asking me for art advice but i'm really not the most equipped person to ask TTOTT I've never been deliberately studious with my art so I feel bad offering advice when I've mostly gotten by with just drawing fanart and ocs a lot... my rate of improvement has therefore been slow, but I've still had an enjoyable learning experience so perhaps from that angle my input may help! i'll mainly refer you to external resources that have helped me

For anatomy + drawing humans:

1) I know I'm not diligent enough to sit down and study muscles, so instead I make it more enjoyable by drawing my favorite characters in a pose that targets the muscles I want to practice! (i default to drawing ppl naked because of this lol) This isn't the most efficient, but it serves as good motivation to get practice in. (honestly a lot of my general art advice has the undercurrent of becoming so obsessed with characters to drive your motivation to draw even when artblocked/ struggling with doubts!)

2) I want to refer you to Sinix's Anatomy playlist! Although Sinix focuses more on digital painting, he gives simplified anatomy breakdowns that include how muscles change shape under different movements/poses, which is crucial for natural human posing. the static anatomy diagrams from Google don't really help for that

3) What's just as important as anatomy is gestures! (especially important if you're used to drawing non-human objects I think!) Making figures look like they have flow to them will sell the "naturalness"(?) to your anatomy. If you have in person life drawing sessions accessible near you I'd recommend trying those out, or if you prefer trying it digitally there's this website!

This helps you not only get a sense of human proportions, but also natural posing! I'd limit the time taken to draw the poses from like 10 seconds to 1 minute(?) for quick gestures, and maybe 1 minute to 5mins(for now!! typically they go much longer) to study human proportions. I'd say don't spend a lot of time on them, repetition is more important!

4) I've also picked up on useful anatomy tidbits from artists online! Looking at how practiced/ professional artists stylize a body helps me focus on what the essential details are to convey a particular form (looking up "human muscles" and being hit with anatomy diagrams full of all the smallest details can be overwhelming! what do you even focus on?! so these educated simplifications really help me) Like Emilio Dekure's work! Look how simplified these figures are, and yet contain all the essential information to convey the sense of accurate form (even though it's highly exaggerated!)

(shamefully admits I've never studied from actual anatomy books so I can't recommend anything in that sense TTOTT)

For general improvement:

1) I highly recommend Sinix's Design Theory playlist and Paintover Pals! (+ his channel in general) You don't have to put them immediately into practice, but I think these are good fundamental lessons to just listen to and have them in the back of your mind to revisit another day. Plus these videos are just fun and very approachable! Design theory fundamentals are essential to creating appeal and directing a viewer's attention, and critiquing others' work/ seeing his suggestions are a good way to practice noticing areas of improvement+ solutions yourself!

2) If you prefer a more formal teaching resource, the Drawabox YouTube course covers all the basic fundamentals of drawing in short lessons. But honestly if I were starting out, this would be a little intimidating for me (and even now it still is! I haven't done all of them) But even if you don't watch them, the titles should give you an idea of the basic concepts that are valuable to pick up. I think it would be nice to keep in mind and revisit once in a while as you learn!

(One lesson I do encourage you to watch is the line control one! A confident continuous line conveys motion and flow much better compared to discontinuous frayed lines which I think is good to practice early by drawing from the wrist and shoulder)

3) As a universal piece of advice: Please please please use references! Use a reference for literally everything, observing is how we learn! You'll find that a lot of things you thought you knew what they looked like are inaccurate by memory alone. Also, trace! This is solely for your practice, tracing then freehanding has helped me grasp proportions when I was struggling! (of course don't post these online if you traced from art)

I've found that being able to compile references into easy to access boards has been very helpful in encouraging me to use references more. For PC, I think they use PureRef (free/pay what you want), and for iPad I use VizRef. VizRef is a one time purchase (which was definitely worth the $3.99 USD price imo)

4) On that note, try building up the habit to observe from media + real life and make purposeful comments about what you see! Like hey, when I bend my knee, the muscles/fat in my thighs and calves bulge outwards, I should draw that next time. Purposeful observation carries over to your overall visual library, and it's a little thing that adds up over time

5) For motivation, get into media you really enjoy, or make your own characters! The way I started art more seriously was by drawing fanart + OCs from anime that I liked ^^ For OCs it really encourages you to draw more because you're the primary creator of their art! Also you gotta see a lot of good art to make good art! Watching visually appealing media (like animation with appealing stylization/simplification) can passively help you learn just by observation.

ok wow I could go on but this is already a lot of information TTOTT my main aim for this reply is basically: don't let anything discourage you from learning to draw!! drawing is so fun and brings me a lot of joy ^^ practicing often will of course help you improve, and the way to incentivize that is by having fun with it! i hope this could help!💞

#my asks#art resources#trying to be concise n failing#i'm mainly worried that like. my art tips make me sound more skilled than my art actually is

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q: What are the merch artist/artist app requirements? Does artistic nudity/gore count as NSFW?

A: Page, Spread, Collaborative, and Merch Artists are to provide a link to a portfolio with at least 3 finished works and, ideally, no more than 10 pieces. Pieces in your portfolio should be shown in order for best viewing, with your best works shown/listed first. These pieces are to be a representation of your current style (or style you intend to use for the zine) and skill. Any traditional artwork in your portfolio must be scanned at 300 DPI or higher.

Page/Spread/Collaborative Artists are required to have at least 1 environmental (interior or exterior) background. Merch Artists should have their required 3 pieces be character-focused.

Depending on the role(s) you'd like to apply for, we provide different suggestions to include as a part of your portfolio. We recommend leaning your portfolio to meet these suggestions to be better weighed towards the role(s) indicated in your application! These can be aspects such as: character interactions, rendered food, composition, use of negative space, stylization/simplification, and so on.

We consider things that are sexual or suggestive in nature to be NSFW, so some artistic nudity and gore is allowable as long as it's not suggestive. Please use your best judgment and defer to canon levels of gore/artistic nudity to stay SFW!

Most of this information can be found on our info doc—any additional details will be added by the time apps open!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overall I’m glad AMC IWTV exists and I enjoy the new things it brings to the table. But I think it simply didn’t linger on the themes and emotional beats I personally loved most in the original story? It barely had them at all tbh.

As I’ve complained previously, I do feel really strongly about Claudia and Lestat’s dynamic and how Lestat turns Claudia into a vampire to trap Louis. And just how involved he is and how complicated all three of their relationships become.

The show I feel chose to focus on the messy *romantic* relationship Lestat and Louis have. Once Claudia and Lestat hate each other, that is that and there doesn’t appear to be much more nuance there. What matters is that Louis has an abusive spouse that he can’t decide whether he loves or hated.

Meanwhile I felt that the 1:1 depiction of domestic violence flattens the metaphor for a fledgling vampire and maker in a way that’s just not as interesting to me. The very conceit of a maker and fledgling can be so interesting as a vehicle for exploring suffocating dynamics, abuse, codependency, and various sorts of complexities, in stark stylized contrast. But the introduction of bluntly framed domestic violence feels like it collapses all of that potential into the simple metaphor of a violent spouse. I also just generally didn’t like how it chose to explore this, and I would admittedly likely feel much more generously if I had thought its take was incredibly compelling on its own. But I didn’t really.

I don’t know. The show generally felt like a mixed bag. I think it had a very strong opening, and likewise strong finale. The middle dragged on, exacerbated by the simplification imo because it frankly started to feel like they didn’t have enough content. Claudia and Lestat’s animosity, particularly, began to feel one note and her later choice to kill him much less emotionally effective as a result, because when even was the last time they gave a shit about each other? It doesn’t feel like a difficult choice. Once again it only matters from the perspective of Louis’ turmoil. Which is itself an interesting one! But losing complexity here doesn’t really feel like streamlining to me, and there was plenty of lingering on the drawn out feud itself.

So idk. I enjoyed the show. I think it’s good. I really appreciate a big budget vampire series that’s dedicated to the tone and aesthetic even being out there in the current, very barren, genre landscape. I’m also really happy to see renewed interest in the general series and characters. I respect a lot of the writing choices. And simply having black vampires, who are protagonists is itself really cool and necessary! Vampire fiction tends to be a very white and racist genre! And like it’s awesome to see it be so openly queer and casual. We’re told point blank that these characters are in love and we get to see them kissing and being casually romantic without any narrative balking. That’s fantastic! I’m so glad we have it! Its amazing that this adaptation exists.

But also yeah at the end of the day it did very much gloss over the dynamics and themes that personally drew me to the story in the first place. So at this point, I’m honestly more excited to see future seasons, once its finished with the first book’s storyline and delving more into the rest of the world and the characters.

I really loved the dedication to all the easter eggs and breadcrumb trails to future VC stuff. And it’s cool that they’re clearly already approaching the story with the rest of the world and future plot developments in mind — something I honestly doubt Rice did lol. So idk I think it’s going to be a fun, wild ride going forward! But I’m also mildly lukewarm about where we are with it now.

I’m hoping I’ll feel differently on a later rewatch where I know exactly what to expect from the story and where it’s going.

#amc iwtv spoilers#interview with the vampire#vampire chronicles#amc interview with the vampire#lol is putting this in the main tags a mistake? hopefully I won’t get yelled at!#i ramble sometimes

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

eckharts extended zodiac

thisll be my post where i explain the project and list rules

my goal is to make a sprite for every extended zodiac sign

these characters are FREE TO USE in MOST THINGS granted you DO NOT FIT MY DNI CRITERIA. scram if you do

iam in fact encouraging you to draw these characters

basic rules about the characters

1. do not drastically change the design. stylization or simplification is ok but keep the character recognisable.

2. do not change the pronouns i gave the character. those will be listed on each post

3. do not change the name of the character

4. do not use my characters in hateful or nsfw content

5. always let me know if you make something with the characters. send an ask linking your post or (preferably) tag me in it each time

posting the characters off site is ok as long as you LINK BACK to my blog AND let me know you did

if you have any questions , just send an ask

the characters will be tagged by blood color for easy sorting and looking up

thats all for now thanks for reading and remember reblogs are an artists everything (reblog my sprites if u like them please and thank you)

toyhouse folder . if you draw any character it will be added to the corresponding profile on here

ᓚᘏᗢ

1 note

·

View note

Photo

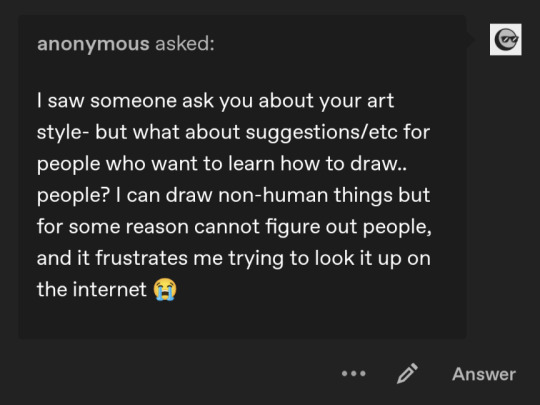

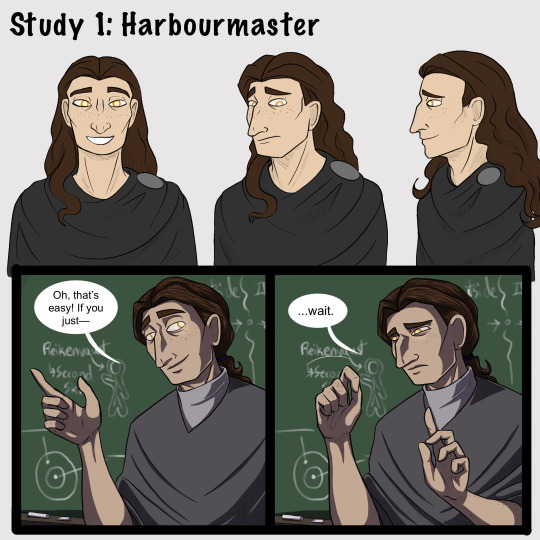

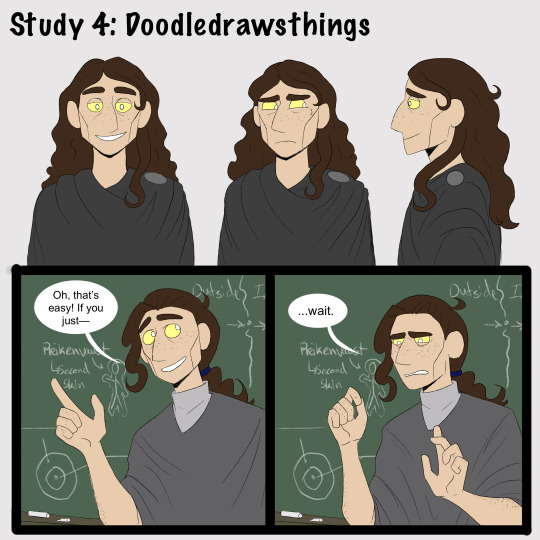

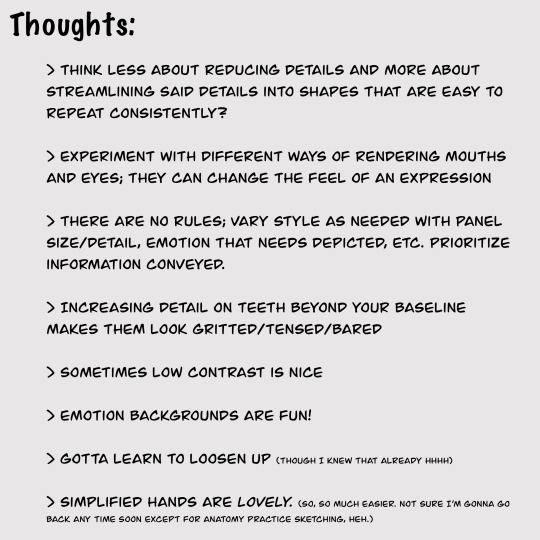

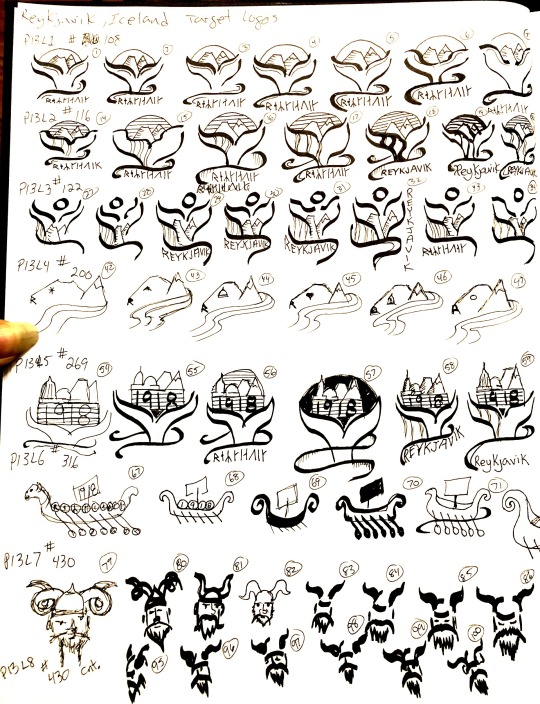

[Brief image description: A series of illustrations of Gerou teaching in front of a blackboard. The illustrations repeat, each in a different art style; at the end is a collection of doodles mixing the art styles and a few notes reflecting on the exercise. Full description and transcript starting at the heading below the cut. End ID.]

Part one of some recent style studies I’ve been doing, featuring Gerou struggling with student teaching!

I wanted to explore how different artists that I like handle stylization and simplification in comics, and when I asked around several people gave me permission to post the results. I recommend checking them out!

1) Harbourmaster is by @waywardmartian.

2) Never Satisfied is by @ohcorny.

3) Broken is by @yubriamakesart.

4) @doodledrawsthings makes a lot of content that is posted to tumblr, most recently a fair amount of A Hat in Time fanart.

Thank you all for the permission to post! ^_^ I'm having a lot of fun with this.

.

Side notes:

I genuinely thought that the Harbourmaster style would be easiest for me, since it contains roughly the same amount of detail as my own style and since I’m like 75% sure that reading it as a younger teen informed a lot of my own style and character designs. Turns out it was actually the hardest! Perhaps because, since there aren’t as many blatantly fundamental differences, I had to pay more careful attention to proportions and specific forms?

.

Never Satisfied was interesting! Alongside the work of Doodledrawsthings it’s definitely the furthest from my own style, and choosing Gerou for this honestly doesn’t do that difference full justice. I looked a lot at Fidelia, Sylas’s mom, and Thierry in trying to figure out how Gerou’s facial features would translate. Part two of my plans is to explore different character designs that might make fuller use of the difference in style, heh. (In other news: Colored lineart looks very neat and studying how it’s handled in NS is the first time I’ve been able to carry it off in a reasonable time frame, hah.)

.

Broken is just... very pretty, y’all. xD I don’t think it really saved me any time or much ease of drawing over my own style, but it’s very nice to look at. And I think the style differences and specific simplifications do lend themselves very well towards creating more consistency than I ever manage in my own art. Noticing the patterned way of drawing ear details was a fun moment for me, I’d never really thought of codifying anything that way before!

.

I did the first drawing in Doodledrawsthings’s style (the 3/4ths view in the turnaround) and thought “Oh goodness this is lovely and quick and feels nice.” It’s very nearly the first time drawing something in a cartoony style has ever come easily for me. But... I struggled much more with every other drawing in that style, ahah. Still, it was comparatively quick and I do love the expressiveness of the stylized eyes. :D This is another style where I think I’ll need to explore a wider range of character designs, though. I think it’s also worth thinking about how character design is fundamentally changed in some ways by the change in style; some of what I would think about designing a character specifically for that style is very different from the details I would normally think about when designing a character.

.

[Detailed image description:

A series of images repeating the same content in different art styles, followed up by a page of sketches and a page with text notes.

The repeated content is a turnaround of the character Gerou as well as a short two-panel comic showing Gerou as a student teacher in front of a blackboard. Gerou is a thin white man with sallow freckled skin, a large hooked nose, long wavy brown hair, and glowing orange-yellow eyes. In the comic, in the first panel he gestures animatedly with a wide smile and says, “Oh, that’s easy! If you just--” then breaks off. In the second panel he holds up a hand as if asking for a pause, and says, “...wait,” with visible consternation.

The sketches feature continued style experimentation with Gerou making a number of expressions and gestures, including: absolutely failing to maintain a good pokerface; looking stressed; various smiles, from tired to nervous to wide and happy; sighing tiredly; sticking out his tongue with arms crossed huffily; arguing with someone; drinking tea; and fighting off a dizzy spell.

The text image is headlined Thoughts and reads as follows:

Think less about reducing details and more about streamlining said details into shapes that are easy to repeat consistently?

Experiment with different ways of rendering mouths and eyes; they can change the feel of an expression

There are no rules; vary style as needed with panel size/detail, emotion that needs depicted, etc. Prioritize information conveyed.

Increasing detail on teeth beyond your baseline makes them look gritted/tensed/bared

Sometimes low contrast is nice

Emotion backgrounds are fun!

Gotta learn to loosen up (though I knew that already hhhh)

Simplified hands are lovely. (So, so much easier. Not sure I’m gonna go back anytime soon except for anatomy practice sketching, heh.)

End image description.]

#I have been hyperfocused on this for a week straight whoops#art#style study#artists on tumblr#style experiment#comics#my art#my stuff#sketches#Gerou#Imperfect Science#image described

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

im gonna complain to you about how wolfquest devs say that a 1060 is a mid range card which ime it is not (dont mind me im just salty that with a 960M i need to run wolfquest anniversary edition on all low to get 25fps and can't justify to myself buying a whole new machine just to run 1 game bc laptops are hard to upgrade individual parts and idk if this rog even has the power supply for a 1060 anyway)

I honest to god think that game studio higher ups just don’t know about the whole “bitcoin made it impossible for normal people to buy a graphics card” thing.

They’re all so fucked up wealthy or so sure that they’re about to be fucked up wealthy that it just doesn’t occur to most of them.

So, they see, “well the 1060 was on the lower end of its family’s power, and the family is several years old now, so this is totally a midgrade card that the average consumer can afford.”

And don’t actually consider, like.

Prices or anything.

Because they want their games to have individually rendered blades of grass and drops of sweat, even though it’s been established time and again for literally decades now that hyper-realism takes more resources and produces worse immersive results and poorer aging of a property, whereas stylization, exaggeration, and simplification of models all produce better immersion, performance, and aging.

The last game that actually warranted its top-of-the-line graphics card requirements was probably Journey or similar art pieces where the intense graphical needs are intrinsically tied to both the story and the art style.

Of course, a lot of devs know all of this full well. I have friends in the industry and it’s widely accepted as a truth.

However, the higher ups in charge of pleasing investors and shit, they have no fucking idea.

And it’s literally destroying the industry, just like every other fucked up, detached from reality decision that seems to come out of game studios these days. Loot boxes, crunch times, mass layoff and rehire cycles. All of that shit.

And it’s literally all because pleasing the paying player or creating a piece of engaging art or immersive entertainment is not the point of these studios.

The point is to please the capitalist assholes behind the studio who are pretending like their investment is the only thing between gamers and a world without the fucking internet.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

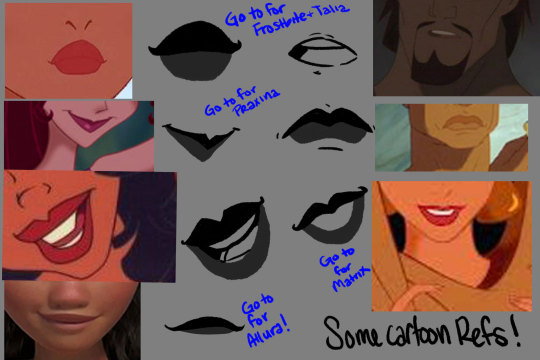

Do u have any tips on drawing mouths, noses, ears and eyes? I’m really struggling with facial features in general and adore your style ❤️

12Buckle in kids cuz this is gonna take some time…

Firstly, let’s start with the head. I always tell people to draw from real life to really get a sense of variety, but because I sometimes find features I really like on animated characters, I’m going to do a mix of both. When drawing heads, its important to (1) remember to use basic shapes when building them and (2) make sure to make guidelines for proportional placement of the brows, eyes, nose, mouth, and on occasion, the chin:

Heads can be altered to depict age ranges by exaggerating certain features; the guidelines also help in knowing where to place cheekbones, scars, freckles, moles, wrinkles, dimples, etc.

After you’ve gotten your basic head shape set up, you want to make sure if they can hear, they have ears! Ears are subject to your individual style, and can come in various shapes and sizes, with details such as jewelry, injuries, and paint. It also can depend on the age. There are baby ears, which are soft and delicate, pierced and gaged ears, as well as those oldie but goodies:

Your style and subject matter will determine their outcome. You can either just draw the shape with no detail, or add small lines to show depth. You should also consider the audience and genre. Take into consideration Leonard Nimoy’s Spock, which has more fantasy-styled ears vs Zachary Quinto’s Spock from 2009, which is more natural, and shows a simplification due to his human heritage:

Note that the Vulcan ears differ from the shape of Legolas’ elf ears and Princesss Allura’s Altean ears.

Next, we move on to a fan favorite: EYES!

Like ears, eyes are stylized base on your preferences. DO NOT COPY ANOTHER ARTIST’S EYE STYLE, MAKE YOUR OWN. All artist had to figure out what worked for them and the best way to do this, which is what I did, was find a bunch that have what you like, and experiment with them to find what you do like until you get that special one that just works! In addition, DO NOT BASE EYESHAPE OF RACIAL STEREOTYPES. THAT GOES FOR LIPS, NOSES, BODY TYPES. EVERYONE IS DIFFERENT!!! Not all of one race look one way, so add a little variation. Even if you wanna say “Oh well theyre all Japanese” they still shouldn’t look the same! Take a look at Tzipporah’s sisters from Prince of Egypt (1998):

Not only do they have varying shades from skin and hair color, they have varying head shapes, body types, and EYE shapes. This is the path to avoiding same-face syndrome!

These are a mix of different shapes I’ve collected. Practicing over real life faces or looking at refs for different shapes is a great help. Practice makes perfect!

Next, we’ll focus on the wonderful world of noses! I like working with different kinds because like eyes, your character can have any nose you want them to! Check out these snifferoos:

If you’re going for a more anime style, “Naru-nooose!”, “Gotta Sniff ‘Em All”, and “Where is it?!” are the most popularly used. Venus style from Hercules (1997) is loosely based on Aegean and Ancient Greek art, so if you are looking to stylize it based on ancient art, that’s a good movie to look into. Study your art ya’ll! I actually use this style for my OC Venus. I like to use “Cutie Patootie/Beep Beep Bitch” for my OC Frostbite, and its perfect for slipping in that little nose ring she has; Have fun with these. You can go full on Ichabod Crane if you want. Noses are one of those features that add variety depending on its size; all of these can be enlarged or shrunk for your benefit!

Lastly, we’re moving on to my personal favorite: LIPS. I got my inspiration for mouths from shows using Bruce Timm’s style. Batman: The New Adventures (1997) is my go-to for expressing through mouth work for my characters. I mean look at them:

I love that they’re so define even in intense action scenes; I’m just so drawn to the color and the way it contrasts with the complexions of various characters. Now, lips are subject to stylization, but I really want to hammer home on taking references from various people:

There’s such a wide variety of shapes, and if you’re just as tired of seeing everyone with that instagram guru lips were they draw waaaay past their lip line, take from random people who aren’t pros. In addition, take from ethnically diverse movies:

These can work on characters of any ethnicity to add a little more alternatives and to make them stand out against other OCs out there. Also one thing I took from shows like LoliRock is to use varying colors: a dark top lip and a slightly lighter version of it on the bottom. You don’t have to do it that way, its just a personal preference.

Down below is a list of movies that are really good at showing variants in character design; hope this helps!

Movies/TV Shows: Prince of Egypt (1998), Coco (2018), The Road to El Dorado (2000), Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001), Big Hero 6 (2014), Brave (2012), Moana (2016 - especially in the concept designs of villagers); Miraculous Ladybug (2014); most Ghibli movies are really good about this on the non-heroine aspect…

123 notes

·

View notes

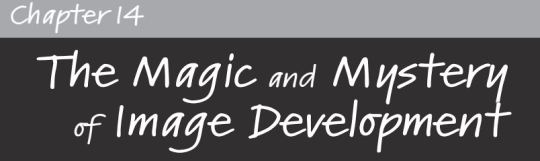

Photo

Sep. 30 - Visual Journal

Reading: Sharon McCoubrey's "The magic and mystery of image development"

Key preparatory steps, prior to making art!

This chapter dissects image development into some really interesting parts. It also provides a lot of options for how to approach image development. My experience was primarily creating an image from observation which is of course useful, but by no means the only way of setting up image development in a classroom. I love the idea of creating an image from memory or telling a story and having the students draw what they imagine the character of the scenery looks like. I think it could be a lot of fun and really show the students alternative ways of creation. I also like the prompt of emotions to either read or create an image. I think this could complement and integrate Social Emotional Learning into the art lesson. How does this piece of artwork make you feel? How would you represent love, happiness, or anger? I could see this being a great starting point for conversations and sharing of art work.

Image Development Sources:

1. Observation

2. Memory

3. Imagination

4. Concepts/Ideas

5. Sensory Experiences

6. Feelings/Emotions

Image Development Strategies:

Abstraction, Elaboration, Magnification, Multiplication, Reproduction, Point of View, Juxtaposition, Metamorphosis, Distortion, Exaggeration, Fragmentation, Minification, Serialization, Reversal, Simplification, Superimpose, Substitute, Disguise, Isolate, Stylize, Animation

Colour Theory

Hue = Colour, Saturation = Intensity(subtle - vibrant), Value = Dark or Light

Monochromatic = Match

Analogous - Next to each other on the wheel

Complementary - Opposite each other on the wheel

Split, Triadic(striking!), Tetradic(one dominante, 3 accents)

CLASS HIGHLIGHTS/THOUGHTS:

Images used as reference to inspire ideas, MODELING

Sketchbook = Rough Draft <- More free to explore, PLAN!

REFINE! REFINE! REFINE!

Suggestions: Tell a story without showing illustrations, Open-ended prompt

Discussion: OFFENSIVE ART!? What to do?

When discussing potentially offensive art, it is always important to assume positive intent and it could be an excellent lesson on being able to distinguish between intent and impact. We may not have meant to offend with our art, but if the impact is offensive we should talk about it and hopefully reach some resolution or understanding. Anna and others in class also suggested that it’s important to TAKE TIME to address offensive art in class and that you, as the teacher, might not have the answer right away, but putting a pin in it, admitting that you don’t have the answer but that you will take the time to understand and address it at a different time is important. It is a heavy consideration, but one that we need to be prepared for.

0 notes

Text

ESSAY: "Mad, Bad, & Dangerous to Know"- Narratives of Female Killers in Law & Media

The accepted roles of women continue to be those of nurturers, and idealized conceptions of womanhood remain tied to vulnerability, gentleness and self-sacrifice. Consequently, the element of female violence becomes doubly jarring.

X-Posted to Aletheia

In both reality and virtuality, the phenomenon of the 'female killer' is imbued with the illicit charisma of transgression. History is woven with literary and cinematic portrayals of women who kill, their personas mythologized until they have become staples in the popular imagination. Biblical archetypes such as Lilith, Salome and Jezebel are steeped in evocative subtext of the predacious, pre-patriarchal feminine entity. Similarly, the tautological relationship between the femme fatale and the film noir genre has long since been established, with the femme serving almost as a repository of everything irresistibly devious, yet simultaneously aberrant to the prescribed roles of her gender. Indeed, when perusing any account of female murderers, from fictive to real-life, there is an implicit sense that violence is the realm of the masculine. Women who traverse into this sphere, therefore, are aberrations – not just at the societal but the biological level. Although 'femininity' is an ever-evolving concept, it remains entrenched in patriarchal presuppositions. The accepted roles of women continue to be those of nurturers, and idealized conceptions of womanhood remain tied to vulnerability, gentleness and self-sacrifice. Consequently, the element of female violence becomes doubly jarring. It challenges society to reassess its established standards of sex/gender, exposing the deeply-embedded binarizations and prejudices still in play.

In order to rationalize the seemingly arbitrary behaviors of female murderers, two stock narratives are often employed by law, media and fiction. Known predominantly as the "mad/bad" dichotomy, this construction can be traced as far back as Lombroso and Ferrerro's seminal criminological work, The Female Offender. Intended to explain non-stereotypical female crimes, such as homicide and filicide, Lombroso first delineates the essence of "normal womanhood" – a paragon of passivity, guided by pure maternal instinct and utterly devoid of sexual desire. Women who depart from this definition are "closer to [men]... than to the normal woman," yet the masculinization does not elevate them shoulder-to-shoulder with their male counterparts. Rather, the criminal woman is a hybridized sub-species closer to children and animals. Firstly, as a creature of "undeveloped intelligence," she is riven by irresistible impulses and ungovernable emotions, thus susceptible to "Crimes of Passion/Mad Frenzy." Secondly, she exhibits a "diabolical" cruelty that far exceeds that of the male criminal, owing to a biological predisposition wherein her "evil tendencies are more numerous and varied than men's" (31-183). As Lombroso sums up,

"...in women, as in children, the moral sense is inferior... That which differentiates woman from the child is maternity and compassion; thanks to these, she has no fondness for evil for evil's sake (unlike the child, who will torture animals and so on.) Instead... she develops a taste for evil only under exceptional circumstances, as for example when she is impelled by an outside force or has a perverse character (80).

While such gendered contradistinctions have long since fallen into disfavor in criminological research, the "mad frenzy" versus "diabolical" categories continue to determine how female violence is portrayed in both media and legal discourse. Described by Brickey and Comack as a "master status template," these trajectories of 'mad' or 'bad' either victimize or pathologize female offenders, displacing the focus off the crime and onto the woman's inability to fit into predesigned boxes of normality, and more significantly, femininity (167). For instance, in the 'mad' polarity, the woman's agency is diminished in favor of painting her as a victim: "depressed," "traumatized," "deranged," and ultimately at the mercy of her emotions. It glosses over the killer's responsibility as an equal citizen under the law, falling back on archaic feminine tropes of passivity and helplessness that serve only to reinforce gender stereotypes. Granted, while mental illness can and has been a valid defense against culpability, it proves problematic when it reduces women who kill to Lombrosian roles of primitive infantalism. They are not dynamic actors in their own right, but tragic casualties of female physiology gone awry. On the 'bad' end of the spectrum, female killers are subsequently masculinized as per Lombroso's model, then stripped of all 'womanly' attributes, i.e. morality, kindness, delicacy. The language employed by media, literature and law alike tends to vilify them as deviants, beyond redemption or reform – and thus beyond the realm of humanity (Cranford 1426).

Both these approaches prove detrimental for a number of reasons. First, they force attention away from treating female offenders as nuanced singularities whose motivations are fluid and complex. Second, an outsized focus on their perceived biological or psychological failings does not offer a broader understanding of criminogenic behaviors at a macro-structural level. Indeed, it can be argued that such simplistic typologies as 'Victim' or 'Monster' serve only to highlight and feed harmful gender stereotypes, reducing these women to grotesque spectacles of 'Otherness' based on their deviance from the discursive framework of femininity.

To be sure, women who kill are statistically rare. Data compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 2003-2012 revealed that males carried out the lion's share of homicides at 88% ("Ten Year Arrest Trends by Sex"). When filtered through the designative lens of serial murder, i.e. "…a series of three or more killings… having common characteristics such as to suggest the reasonable possibility that the crimes were committed by the same actor," the number of female offenders dwindles further ("Serial Murder" 7). In his work, Female Serial Killers: How and Why Women Become Monsters, Peter Vronsky remarks that only one in almost every six serial killers in the USA is a woman (3-5). Studies conducted in the early 1990s also revealed that men were six to seven times likelier to kill others – strangers or relatives – than women (D'Orbán 560-571; Kellermann et al. 1-5). Similarly, Harrison and others found substantial effect sizes between both genders, in addition to marked sex differences in their modi operandi, i.e. males conforming to a "hunter" strategy of stalking and killing, while women resort to "gatherer" behaviors by targeting victims in their direct milieu for profit-based motives (295-306).

While these findings might explain the tenacious constructions of femininity – and subsequent 'deviance' – that still cling to the overall subject of female killers, they do not excuse them. Indeed, it can be argued that popular media portrayals of women who kill further fuel these stereotypes. News, infotainment and cinema alike employ a highly effective formula whose pivotal components are simplification, sex, violence and graphic imagery (Jewkes 43-60). Female killers cannot fully satisfy this sensationalist criterion except as caricatures. Otherwise, as highly complex and richly variegated individuals, their existence would prove to be a messy fissure within the neat constructions of gender and power dynamics – a status quo that the media arguably serves to reaffirm and maintain (Kirby 165-178).

It is unsurprising, then, that a marked dichotomy can be observed in the portrayals of male versus female killers. As previously noted, male serial killers are believed to exhibit "hunting" behaviors, with their crimes seen as the evolutionary offshoot of "unconscious drives" (Harrison 304-6). Applying this hypothesis under the aegis of patriarchy, men who kill subsequently become distortions of the masculine ideal: the quintessential hunter. The nature of their crimes is at once instrumental and agentic; their actions are rooted in destructive hypermasculinity – but masculinity all the same. Their actions are shocking, but in their own way they serve as paradigms of nonconformity. They have broken free from the artificial constraints of society, rejecting the very source that dares to judge them. Certainly, for Lombroso, the male killer was often coupled with genius, and his deviance linked to retrograde evolution, wherein his sloughing-off of societal norms, and ultimately sanity, was a biological reaction to being excessively endowed with high intellect. For Lombroso, while female killers were a biological anomaly, the males were often a trailblazing nexus between exceptionality and atavistic brutality – "creators of new forms of crime, inventors of evil" (74). In their book, The Murder Mystique: Female Killers and Popular Culture, Laurie Nalepa and Richard Pfefferman remark that:

Murderers are not heroes. But killing— whether motivated by passion, greed, thrills, madness, ideals, or desperation— is an extraordinary act; not an honorable one, to be sure, but undeniably extraordinary. And extraordinary acts— even depraved ones— tend to have the effect of elevating the perpetrator to iconic cultural status (4).

It is unsurprising, then, that the media deifies such individuals by capitalizing on their very notoriety. They are bestowed catchy yet edgy nicknames such as Boston Strangler, Skid Row Slasher, Night Stalker, etc. Their exploits receive exuberant, stylized coverage, while their actions are profiled and dissected to the point where they eclipse needful attention to their victims. History recalls with a horrified yet titillated clarity the names of Jeffrey Dahmer, Charles Manson, Ted Bundy and Richard Ramirez. However, their victims are seldom so fervently immortalized. The implication is that these killers are superstars within their own sensationalist dramas, whereas their victims function as mere props to drive the narrative forward. As Lisa Downing notes in her book, The Subject of Murder: Gender, Exceptionality, and the Modern Killer, "...a pervasive idea obtains in modern culture that there is something intrinsically different, unique, and exceptional about those subjects who kill. Like artists and geniuses, murderers are considered special ... individual agents" (1).

Cinema, too, reinforces the phenomenon by lending male killers, both real and fictional, a disreputable mystique – often elevating them to the status of cult fixtures. Examples of this trend include the critically-acclaimed American Psycho, which juxtaposes orgiastic violence with careless misogyny, but is nonetheless lauded as a masterpiece of urban self-satire, as well as the fast-paced psychedelia of Natural Born Killers, where chaotic murder-sprees are translated as thrilling acts of rebellion and self-expression against a hypocritical society. Similarly, the mythic Hannibal Lector, in Jonathan Demme's Silence of the Lambs, is portrayed as a ruthless strategist whose skills, while undoubtedly evil, can also be harnessed for good because of their collective desirability. Lector the killer may be abhorrent and ghoulish; however, Lector the man holds something of an esoteric appeal. His very transgressions serve to glamorize him as a shadowy figure of fascination and reverence (Roy 61-92).

The cinematic emphasis on male killers as paradigms of intelligence and charisma doesn't extend to pure fiction. Recent docufilms such as Joe Berlinger's Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile – which focuses on the exploits of real-life serial killer Ted Bundy, as played by the photogenically clean-cut Zac Effron – further underscore the tendency to glamorize male killers. As Anne Cohen notes, far from throwing a necessary spotlight on Bundy's victims, the film reduces them to irrelevant footnotes against a fawning narrative of Bundy's private life, as served up from the POV of his then-girlfriend Elizabeth Kendall. While the film's original intent may be to illustrate how Bundy's boy-next-door glibness could successfully fool his intimate circle, it arguably overshoots the mark by romanticizing Bundy to the extent that the audience becomes just as infatuated with him as Elizabeth. As Cohen states, "There's only so many times we can watch Ted’s tender acceptance of [Elizabeth] as a single mother, his devotion to her daughter Molly, his thoughtful gestures — cooking breakfast, playing in the snow, wearing a lame birthday hat — before we… start to feel enamored" (1). The subsequent backlash after the biopic's premiere, coupled with the perverse flurry of online admiration it rekindled for Bundy, is a classic case of the film's message becoming lost in translation (Millard 1). It also serves as a potent reminder that framing, whether intentional or accidental, allows male killers to invariably maintain the pedestal of cultural obsessions. As critic Richard Lawson puts it,

It’s indeed a wicked bit of casting. In addition to his heinous crimes, Bundy was famed for being disarmingly good-looking and charming. But he certainly wasn’t an Efron-level sun-god—so Efron’s presence in the movie lends the proceedings an extra otherworldliness, heightening the insidious appeal of American serial-killer lore to something almost pornographic (1).

Ultimately, whether biopic or fiction, these films swim through similar undercurrents: within a patriarchal framework, the male killer is a magnetic symbol of human impulse. A dark reflection of reality, certainly – but not, as is the case with female killers, a deflection of it. In contrast, paradigmatic examples of female killers as Lombrosian aberrations exist abundantly in film. Cinematic classics such as Basic Instinct and Fatal Attraction both feature psychopathic female leads, their much-vaunted sex appeal serving as a sinister smokescreen for their more bloodthirsty agendas. Underpinning their sanguinary appetites however, is the implicit strain of 'deviance' that first lures in, then terrorizes, their hapless victims. In Basic Instinct, Sharon Stone's neo-noir femme fatale Catherine Tramell is portrayed as a bisexual, hard-partying thrill-seeker who indulges solely in her own mordant whims. Every facet of her character serves to scandalize the audience – a framing that calls to attention the more docile, morally acceptable standards of femininity, as well as their ubiquity and pervasiveness within society.

However, for all Tramell's seductive dynamism, it is arguable whether hers is an empowering or feminist icon. Her body serves too blatantly as an erotic spectacle for male fantasy, effectively displacing her more human complexities (if they exist at all.) While Berlinger's Extremely Wicked offsets Bundy's erotic charge with a trickster's charm, and humanized nuances of emotion, Tramell's character remains a succubic enigma from start to finish. If anything, she appears to function as a two-pronged warning for male viewers. Firstly, that uncontrolled, untamed and non-heteronormative female sexuality is intrinsically rooted in criminality (Davies and Smith, 105-107). Secondly, that independent and sexually-dominant women are only palatable when their characters are flattened into pornographic caricatures (Meyers 300). In her book, The Dominance of the Male Gaze in Hollywood Films, Isabelle Fol remarks that the film "... appeals in particular to men to avoid deviant women and settle for a homely girl in order to evade the castration threat" (69).

This fact is seemingly underscored by the film's ultimate, ambiguous scene, where Stone and Douglas' characters are locked in a voracious embrace in bed. A foreboding, Hitchcock-esque refrain rises to crescendo and the camera pans down to reveal an ice-pick – Tramell's weapon of choice – concealed beneath the bed. It is through this scene that Tramell's inherent irredeemability asserts itself most explicitly. Granted, she eludes the fate inevitable to a majority of Hollywood vamps – death as fitting punishment for rejecting the traditional roles of womanhood. However, by no means has she been 'cured' by the hero's love. If anything, the scene highlights her perpetual threat as the castrator. The moment the male protagonist fails to satisfy her, she will dispose of him with brutal efficiency before moving on to her next victim. In that sense, she is the 'bad' female killer par excellence, her perceived deviance serving only to reaffirm the status quo rather than dismantle it.

Similarly, Fatal Attraction follows a well-known cinematic formula. A flawed but sympathetic hero – Michael Douglas' philandering Dan Gallagher – is beguiled, bedded then ultimately betrayed by the volatile femme fatale, who refuses to be relegated to an inconsequential fling and instead seeks to invade every sphere of his life, with the intent of eclipsing the very bedrock of patriarchal stability: the nuclear family. In doing so, the femme becomes, by her very nature, deviant – and must be quashed for the threat of chaos she represents. Certainly, the film goes to great lengths to paint Glen Close's character – the seductive and mysterious Alex Forest – as an unstable force who upends the hero's life with escalating levels of terror. An outspoken career woman, Forest also serves as the perfect foil for Gallager's more docile wife Beth – a whore/madonna dualism that is nearly as prevalent in cinema and literature as the mad/bad dichotomy.

Of course, where the latter is concerned, Forest is emphatically depicted as 'mad.' Her behavior is increasingly irrational and demanding, ranging from plaintive entreaties to Dan to return to her, to obsessively calling him at work and at home, to playing on his sense of guilt by announcing she is pregnant with his child, to throwing acid at his car, to killing and boiling his daughter's pet rabbit, to ultimately attacking his wife Beth in her bathroom. The film's penultimate scene, where she is shot dead by Beth after a frantic, bloody struggle with Dan, is represented as both triumphant and wholly justified. The survival of the male hero, as well as the continued sanctity of the family, is contingent on the demonization of the 'Other Woman' – and on her violent expulsion from the narrative. The film's final, lingering shot of the Gallaghers' family portrait acts as a sanctimonious reminder of who the audience is meant to cheer for, from beginning to end. In her book, International Relations Theory: A Critical Introduction, Cynthia Weber notes that,

...Fatal Attraction is far from a gender-neutral tale. It is the tale of one man's reaction to unbounded feminine emotion (the film's symbolic equivalent for feminism) which he views as excessive and unbalanced. And his reaction is a reasonable one ... because it is grounded in Dan's (and many viewers') respect for traditional family. ... Alex has a very different story to tell about her affair with Dan, one that the film works hard to de-legitimize (96).

Taken individually, the narratives of these films – rooted in facile, frivolous fantasy – hardly seem to warrant academic scrutiny. However, central to their criticism is the idea of reflection theory, which purports that mass media is a prism through which core cultural values shine through, combining misinformation and mythology into a seamless real-life spectrum (Tuchman et al. 150-174). That the media bears a cumulative, subliminal impact on its viewers goes without saying. However, so prevalent is its influence on how we perceive gender-traits that we also fail to question the ubiquitous, ultimately harmful constructions concerning women and deviance at both judicial and psychological levels (Gilbert 1271–1300). In their work, Judge, Lawyer, Victim, Thief, renowned criminologists Nicole Hahn Rafter and Elizabeth Anne Stanko remark that one-dimensional portrayals of women in media not only feed damaging cultural assumptions, but also contribute to countless "controlling images" in the sphere of criminal justice. Pigeonholed into tidy categories such as "woman as the pawn of biology," "woman as passive and weak," "woman as impulsive and nonanalytic," "woman as impressionable and in need of protection," "the active woman as masculine," and the "criminal woman as purely evil," these images saturate legal literature and obstruct worthwhile theoretical discourse. More to the point, they lead to sentencing outcomes where impartial justice often takes the backseat to parochial presumptions (1-6).

While it is tempting to succumb to the notion that sentencing guidelines in criminal law are based on airtight logic and objective fact, discretion—and its arguable corollary of discrimination—remains pivotal in shaping legal policy. The law is neither impartial nor inviolate, but as weighed by normative baggage and sociocultural discursivity as any other man-made construct. As Tara Smith remarks, "Law's meaning is not objective, and law's authority is not objective. The "objective" on its view, simply is: that which certain people would say that it is" (159). With that in mind, the actors in court (judge, jury, prosecution, defense) can sometimes play roles that are as rooted in confirmation-bias through the prism of storytelling as they are in factualism. Typologies such as 'mad/bad' can serve as legal polemics against non-stereotypical female crimes, creating blurred lines between lived events and textual constructions as truth. More importantly, the evidence itself can go beyond context-specifity, not standing alone so much as being subject to common-sense fallacies of personal interpretation. As Bernard Jackson remarks,

...triers of fact [i.e. judges, or, in some countries, the jury] reach their decisions on the basis of two judgements; first an assessment is made of the plausibility of the prosecution's account of what happened and why, and next it is considered whether this narrative account can be anchored by way of evidence to common-sense beliefs which are generally accepted as true most of the time (10).

Two particularly notorious cases of female killers, which illustrate the simplistic narratives employed by law and media, are those of Aileen Wournos and Andrea Yates. In each instance, the women committed crimes of a similarly egregious magnitude. However, swayed by a rash of emotive media coverage, where one woman's perceived fragility was poignantly spotlighted while the other was emblazoned as a remorseless outcast, both women received opposite – and in the eyes of the public, apposite – sentences. Aileen Wuornos, for example, was fallaciously touted as the first 'postmodern' female serial killer – a gender-averted Ted Bundy. Working as a smalltime prostitute in Daytona Beach, Florida, Wuornos was charged with the murder of seven male 'Johns' between 1989 and 1990. In each case, the victims were shot at point blank range with Wuornos' .22 pistol. During her prolonged and extraordinarily-publicized trial, Wuornos' rationale for killing the men would vary. Initially, she claimed to have committed the murders in self-defense, as the men either had or were about to rape her. Later on, her accounts took on a darker, more mercenary tinge, with her motives rooted in theft and revenge. After ten years on death row, she was ultimately executed by lethal injection in 2002. So mesmerizingly grotesque was Wuornos' misfit persona – at least as it was painted by the media – that her murder-spree served as inspiration for the Oscar-winning film Monster, a title that seems at once apt and ironic.

On the other hand, Andrea Yates was a housewife in Houston, Texas, who was charged in 2001 with committing filicide on her five children by drowning them in the bathtub. Yates was suffering from post-partum psychosis which, coupled with extreme religious values, led her to believe she was under the influence of Satan, and that by killing her children, she was saving them from hell. Having called 911 shortly after her crime, then confessing once the police arrived, she was convicted of capital murder. Her case was at once highly publicized and polarized, with many condemning her actions while others sought to neutralize her culpability by focusing on her mental illness. The media, in particular, seized upon the latter aspect to portray Yates as a beleaguered and misguided woman whose crimes were merely a distorted translation of mother-love. Initially pronounced guilty, she was nonetheless spared the death penalty, and sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole. In 2005, the verdict was overturned based on the erroneous testimony of an expert psychiatric witness. In her retrial the following year, Yates was found not guilty by reason of insanity, and committed to North Texas State Hospital (Williams 1). She currently continues to receive medical treatment at Kerrville State Hospital ("Where in Andrea Yates now?" 1)

From an objective standpoint, it could be argued that Yates' crimes were diametrically opposed to Wuornos' on the murder spectrum. The latter had no intimate connection to her victims. They were adult strangers – albeit ones who reportedly sought to harm her. Yates victims, on the other hand, all but epitomized stark, jarring helplessness: five children ranging from seven years to six months old. During their court trials, both the women's histories of mental illness were presented as mitigating factors. Yet the outcomes of both cases were vastly different – owing, at least in part, to the different ways in which deviance and agency were conflated, then used to either repudiate or amplify each killer's crimes based on Lombrosian-style archetypes (Nalepa et al 137). As mentioned previously, Lombroso, one of the earliest proponents of pathologizing female criminals, believed that women were by default amoral, with their redeeming feature being their maternal instincts. Devoid of this quality, the masculinized criminal female was ten times deadlier than the male, and inherently irredeemable (183). Despite the outdatedness of this paradigm, a thorough examination of the semantic fields forged by media and law reveals its disturbing prevalence during both Yates and Wuornos' trials. Each woman's description, peppered with loaded language and equivocal statements, served almost as implicit invitations to the jury and bystanders alike to mold the story into the most suitable configuration by filling in its gaps.

In Andrea Yates' case, the media seized upon her status as a housewife, former nurse and high school valedictorian to symbolically separate her from the flagitious nature of her crime. In an illustration of insidious agency-denial, the focus was afforded to the underlying excuses behind her crime, as opposed to her actions themselves. Articles from the NY and LA Times, utilizing statements such as, "Andrea Yates was incapable of determining her actions were wrong... she was ... driven by delusions that they were going to hell and she must save them" as well as "a simple, unremarkable Christian woman. She wore neat spectacles and had streaming hair ... the Yates were an attractive family," all promulgated notions of helplessness and desperation, while also imparting Yates's crime an aura of impossibility (Stack 25; "Killings Put Dark Side of Mom’s Life in Light" 20). This was a sweet, submissive, God-fearing homemaker whose entire life revolved around her family. Her actions were a mysterious, once-in-a-lifetime tragedy, springing from utterly alien internal forces.

Yates' status as a mother – a role that is so often pedestalized and mythologized – was further spotlighted to render her somehow pristine: a murderer, yet morally inviolate because the filicide occurred while she was under extreme duress. Her defense attorney went so far as to state that, "jurors…should pity a woman who was so tormented by mental illness that she killed her children out of a sense of 'Mother knows best'" (Weatherby et al 7). Whether intentional or accidental, the discursive outcome allowed for the construction of an utterly 'mad' woman – paranoid, pitiful, but most importantly passive – thus decimating the challenges Yates might pose to our conceptions of both femininity and motherhood. In her paper Women Who Kill Their Children, Jayne Huckerby went so far as to state that Yates, as a white, middle-class suburban mother, served as a "poster girl" for the romanticized cult of motherhood. Her actions, albeit deviant, were seen as an isolated incident rather than symptomatic of any greater systemic ills. Moreover, affixing her with the 'mad' label – thus focusing solely on her medical malady – allowed her case to be elevated to a political cause. Interest groups such as NOW vehemently advocated against Yates' execution, citing her depression, schizophrenia and hallucinations as excuses. The phrase mental 'state' was used repeatedly during Yates' trial – with clear connotations of its temporal and disjunctive nature. Yates, judicial and media discourse seemed to imply, was not the killer. Her mental illness was. This combinatorial tactic of medicalization and politicization garnered Yates extraordinary support – and quite likely owed to the lenience of her sentence (140-170).

To be sure, Yates' postpartum illness was not a fictional spin – but a legitimate diagnosis that affects women in everyday life. A Brown University study cited about 200 cases of maternal filicide in the US per year, from the 1970s to the early 2000s. It also suggested that psychiatric or medical disorders that lead to a reduction in serotonin levels heighten the risk of filicide (Mariano 1-8). In the US, both antenatal to postnatal depression continue to be debated as mitigating circumstances for murder (Carmickle, L., et al. 579-576). However, in other countries, the close ties of birth and its attendant biological changes to mental illness have been legally acknowledged. Nations including Brazil, Germany, Italy, Japan, Turkey, New Zealand and the Philippines have some form of "infanticide laws," allowing for leniency in cases of postpartum-linked mental illness (Friedman et al. 139).

In Andrea Yates' case, it could be argued that her declining mental health did not arise in a vacuum. Indeed, the highlights of Yates' psychiatric history, even prior to her children's' murder, reveal a woman beset by proverbial psychological demons. In 1999, following the birth of her fourth son, Yates was already suffering from severe depression, and struggling with a feeling that "Satan wanted her to kill her children." That same year, she attempted suicide by overdosing on medication, reportedly in a misguided attempt to protect her family from herself. She was subsequently hospitalized for psychiatric care, only to be discharged and then make a second suicide attempt five weeks later. by cutting her throat She was eventually diagnosed with Major Depressive Episode with psychotic features. After few months' treatment via outpatient appointments, Yates dropped out on the claim that she was "feeling better." Also, despite the warnings from her treating psychiatrist about the recurrence of postpartum depression, she and her husband decided to have another child. Following the birth, Yates went on to be hospitalized thrice more for psychiatric treatment. Her last unsuccessful suicide attempt involved her filling the bathtub, with the vague explanation that, "I might need it" (Resnick 147-148).

Leading up to the mass-murder of her children, Yates continued to display psychotic symptoms, including the belief that the television commercials were casting aspersions on her parenting, that there were cameras monitoring her childcare, that a van on the street was surveilling her house – and finally, that Satan was "literally within her." Convinced that her bad mothering was to blame for her children's' poor development, she fixated on the biblical verse from Luke 17:2, "It would be better for him if a millstone were hung around his neck and he were thrown in the sea than that he should cause one of the little ones to stumble." Ultimately, on June 20, 2001, Yates would wait until her husband left for work, then proceed to drown her five children in the bathtub. When the police arrived, Yates stated that she expected to be arrested and executed – thereby allowing Satan to be killed along with her. Of her children, she would say, "They had to die to be saved" (Resnick 150).

While Yates' actions shocked the collective public conscience, they also garnered an intense outpouring of sympathy. Partly, it was because, as Skip Hollandsworth remarked, "Yates came with no baggage." From her ordinary appearance to her uncheckered background, Yates had the makings of an All-American mother, who "read Bible stories to her five children... constructed Indian costumes for them from grocery sacks...[and] gave them homemade valentines on Valentine’s Day with personalized coupons promising them free hugs and other treats" (1). Her daily routines were familiar, her struggles relatable. It was easy to cast her as a stand-in for other suburban mothers, with her decision to murder her children serving to darkly mirror their own worst fears. As Newsweek's Anna Quindlen noted, "Every mother I’ve asked about the Yates case has the same reaction. She’s appalled; she’s aghast. And then she gets this look. And the look says that at some forbidden level she understands" (1). Ultimately, Yates' status as a suburban housewife allowed her to occupy the pedestal of the Everywoman. The predominant narrative, as imbricated by the law and media, was that of someone unstable, delusional, overwhelmed – yet undeniably feminine. Through her, the more negative extremes of womanhood had been allowed unfortunate expression, a fact that served to render her less culpable rather than more (Phillips, et al 4).

In direct contrast, Aileen Wuornos' narrative was afforded little opportunity for feminization, much less humanization. Rather, her status as a prostitute and lesbian was immediately seized upon by the law and media – then highlighted with pejorative, condemnatory rhetoric. Capitalizing on the strong stigma attached to prostitution, in conjunction with Wuornos' gruff, belligerent, decidedly un-feminine manner, the dominant 'bad woman' narrative was invoked. Central to the trial and its accompanying media coverage was the sense of Wuornos' inherent 'unfitness' – on both a gendered and societal scale. Caroline Picart remarks that, "Wournos, even if given the title of being America’s first female serial killer, in comparison with heterosexual male serial killers, was not generally perceived as a skilled serial killer but, rather, as being a woman who did not know how to be a real woman" (3). In point of fact, Wuornos' designation as the 'first' female serial killer was an embellishment: there are other women who would have just as readily fit the mold of the serial killer. However, prior to Wuornos' arrest, women who killed were stereotypically shrouded behind a ladylike mystique, their modi operandi veering from arsenic and cool calculation, as with Anna Maria Zwanziger, to maternal instincts warped by insanity, as with Brenda Drayton, to Angels of Mercy whose nurturing demeanor hid a crueler edge, such as Beverley Allitt.

Wuornos, conversely, did not fit into any of the conventional molds of wife, widow, mother, nurse or daughter. If anything, she subverted the very conception of prostitutes as disposable victims, prowling along the same highways where numberless streetwalkers met their end. More to the point, her sexual preferences and choice of work marked her as a hostile threat to society – and more specifically to patriarchal stability. When interviewed by the TV show Dateline, she attempted to justify her killings by reminding audiences of the extreme dangers of prostitution. However, she failed to grasp that delving into the gory minutiae of such a socially-reviled profession did her defense no favors. In prostitutes, society too often finds convenient scapegoats. Shunned as breeders of contagion and social ills, they are reduced to receptacles for everything heteronormative family-life pretends to disavow. Yet their role as the integral underbelly of society also necessitates their invisibility – and, by extension, disposability – in order to preserve the immaculate image of the nuclear family. With that in mind, perhaps it is at once ironic and unsurprising that Dateline's co-anchor Jane Pauley states, "This is a story of unnatural violence. The roles are reversed. Most serial killers kill prostitutes" (Hart 142).

The media, of course, ruthlessly weaponized Wuornos' 'outsider' against her. Her checkered history was touted as proof of her immorality, with news coverage running the gamut from mean-spirited to sensationalist. The NY Times was quick to point out that "Ms. Wuornos served a year in prison in 1982-83 for armed robbery…she also faced charges of vehicle theft and grand larceny," "She was a prostitute part of the time," "residents can now rest easy," "Ms. Wuornos was ‘a killer who robs rather than a robber who kills" (Smothers 16). Meanwhile, the LA Times ran an interview with police officers stating that, "We believe she pretty much meets the guidelines of a serial killer" ("Transient Woman Accused in Florida Serial Killings" 40). Every aspect of Wuornos' life was vilified and picked apart, the better to construct the image of an unnatural creature. Even descriptions of her physical appearance underscored the extremes to which the media tried to demonize her. A 2002 article at the Palm Beach Post describes her as "a haggard-looking drinker and heavy smoker…her weathered face has a cold, dead stare that morphs into a wildeyed laugh" (Wells 5). By so assiduously focusing on Wuornos' negative traits, the media sought to render her as unrelatable, and ultimately undeserving of human sympathy. However, at the crux of her deviance was not the violent nature of her crimes, but how far she had strayed from the boundaries of traditional femininity. Wuornos – caricatured as a monster of sheer lunatic aggression, wanton sadism and unmitigated cruelty – was not a 'real' woman. As Jeffner Allen notes in her work, Lesbian Philosophy: Explorations, "Violence is defended as the right to limit life and take life that is exercised by men... A woman, by definition, is not violent, and if violent, a female is not a woman" (22-30).

Similar to Andrea Yates, Wuornos grappled with mental illness. During her trial, both the defense and prosecution employed psychologists who testified that she suffered from Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), in addition to symptoms of posttraumatic stress. First used by analyst Adolph Stern in 1938, BPD describes patients who are at the border between neurotic and psychotic. Individuals with BPD may suffer from patterns of instability in mood, jobs, relationships and self-image. The diagnosis is applied predominantly to survivors of sexual abuse. (Giannangelo 19). In Aileen Wuornos' case, her experiences of sexual abuse from childhood to adulthood, her violent and unstable years as a transient, in addition to her ninth-grade education level and mental disabilities, were well-documented. However, the prosecution minimized these factors during the trial, insisting that they were not "substantial" and in no way impaired Wuornos' capacity as an instigator of violence. As the district attorney claimed in his closing statement, "Aileen Wuornos at the time of the killing knew right from wrong."

This focus on individual action is by itself hardly noteworthy, if not for the courts' further descriptions of Wuornos as "primitive" and "damaged" – a subhuman designation at odds with the portrait of the controlled and calculating serial killer (Sarat 75-77). In Wuornos, the courts attempted to reconcile two seemingly-contradictory, yet equivalent extremes of 'badness' – the Lombrosian archetype of the atavistic female, a primal degenerate driven by a cruel thirst for sex and bloodshed, and the paradoxical essence of 'evil' as it applies to the feminine shadow, with an ice-tipped propensity for malice and manipulation. Yet, where the male killer wears both these discrepant masks of wildness and wit with a dynamic ease, embodying within himself a transcendental self-mastery beyond moral codes, homicidal females such as Wuornos find their narratives consistently entrenched in gendered morality. Even when afforded agency for their own crimes, their humanity (three-dimensional, flawed, self-directed) is downplayed in favor of a wholesale monstrosity. Their true crime is not taking a human life. Rather, it is straying, with eyes wide open, beyond the province of womanhood. As Ashley Wells remarks,

What’s fascinating about Aileen is how little her own mental illness played into her trial and the media hoopla surrounding it... There was no narrative in place for female serial killers the way there was for male ones. So instead of focusing on her mental illness or her horrific childhood, the way we might for a male serial killer now that we have so many to choose from, the media latched onto the fact that Wuornos was a prostitute and a lesbian, some sort of unholy alliance of the two types of women it only knew how to deal with in the broadest possible stereotypes (1).

It goes without saying that criminologists have embraced a broad spectrum of theoretical perspectives, from sociological, philosophical and psychoanalytic, the better to explicate the disturbing relationship between law/media and homicidal women. Predominant among them is Labeling Theory, which can be traced back to Frank Tannenbaum's 1938 work Crime and the Community. Chiefly focused on self-identity, Labeling Theory purports that deviant behavior – both singular and recurrent – is predicated on external categorizations, i.e. the self-fulfilling prophecy of stereotypes. Social categorizations function in pernicious ways, wherein people will subconsciously or deliberately begin altering their behavior to conform to the labels they are placed within.

In the case of Andrea Yates, Labeling Theory asserted itself on multiple levels. First, it was present in the defense constructed by Yates' lawyers, who cleaved tenaciously to the idea that she was a loving mother whose crime – while terrible – was episodic, and fueled by depression. The media too, seized this narrative and ran with it: the poignant image of Yates as a mother who had, quite literally, loved her children to death. Lastly, the insidious strength of labeling manifested itself through the personality of Yates herself. Her terror of failing to conform to the image of a perfect mother, by damning her children to Hell, led her to a shocking act of filicide. Rosenblatt and Greenland note, “it is the very attempt to fulfill her culturally defined role as wife and mother in our society which is often at the source of much of her violence” (180). Certainly, everything about Yates corresponded with the cultural view of women as emotional, flighty and easily led astray. Even her classification as 'mad' came to be viewed with the more sympathetic connotations of the word. Ultimately, it was that exculpatory label that framed the way Yates was perceived – by the courts and public alike (Weatherby et al 3).