#fusion modal chord

Text

Modal Chords:Modal Chordal Harmony

Modal Chords: Harmony

CLICK SUBSCRIBE!

Modal Chords: “Chords” from Transposed Mode [C as Root] Lesson/How to/Examples

Please watch video above for detailed information and examples:

Hi Guys,

Moving on from our last blog on the Modal backing track, I have included another video [above] explanation regarding the modal chords/harmony that I employed.

PDF MODAL CHORDS:

pdf-modal-chordsmodal chords Download

IF THIS…

View On WordPress

#aeolian#chord modes#chords from modes#Dorian#explained#fusion modal chord#how to#ionian#jazz mode chords#lesson#Locrian#Lydian#Mixolydian#modal chords#modal harmony#modalic chords#Phrygian#transposed modes

0 notes

Text

Ok I said I would make a pin full of music so here it is

First off, I mentioned KNOWER. It's a long project that started a really long time ago, but their best stuff is probably coming out like right now. As in, they are just about to release a new album, KNOWER FOREVER. The singles on it are incredible, like I'm The President just comes right out the gate with the fattest walkdown I've ever heard from a horn section. The B section makes it feel like I'm enjoying a song like I would a multiple-course meal. Then Crash The Car just transfixes you. Yes, yes, you should listen to those, but don't neglect the fire they put out in 2017 because you owe it to yourself to watch the live sesh of Overtime:

youtube

Oh god this post is gonna make viewing my blog super annoying isn't it

Anyway the next thing I gotta mention is Vulfpeck. These guys are famous for scamming Spotify, basically. They released an album full of 30-second tracks of pure silence, just absolutely nothing, titled Sleepify. They got online and said "Yo guys, help us raise money for a free concert by listening to this on loop while you sleep." What they were actually doing was exposing a loophole in the way Spotify calculated royalties, and before they could pull the album (citing "content policy violations," of course), Vulfpeck had already bagged around $20,000, so they put on the completely admission-free Sleepify Tour, which was incredibly fucking based of them.

Vulf went on to become several spin-off projects, all entirely independently released and full of some of the stankiest funk fusion that I cannot stop listening to.

My favorite of these projects, The Fearless Flyers, is headed by Cory Wong, with a guitar idol of mine for 5+ years Mark Lettieri and of course the government subsidized active bass of Joe Dart, but the keystone of the group is no doubt Nate Smith on drums. Dude makes a three-piece set onstage sound like a full kit.

Like just look at what they can do with the added power of sax:

youtube

And yeah, I could just talk about those guys, but let's get weirder.

I'm talking modal. The kind of stuff that makes my choir-trained mother cringe inward at the dissonance. Let's talk about the crunchiest, most feral fucking harmonies and keyboard solos that make you question what you thought you knew about chord progressions and key centers.

Obviously anyone super into this stuff will have already heard of Jacob Collier, so I won't show him. But THIS:

I listened to this the first time and it was just.. too much. I put it in its own specific playlist titled "very complex shit" immediately. When I went back to it, enough time had passed and I had learned enough that after way too many listens I can actually follow along with this insanity. This track blew my fucking mind, dude. I have never heard a chorus use so many of the 12 chromatic notes and still sound heavenly. The groove changes add so much texture. The flute solo goes off way too hard. The slower final section is just disgusting syncopation when the drums come back in. Everything about it is incredible, and this album came out in 2007. I am staring back at years of my life I spent not listening to this and ruminating my lack of music theory knowledge. And when I wanted to see if some kind transcribing jazz grad student like June Lee had uploaded anything of System, I found a 2020 reboot with 24 musicians playing System for over twice its original runtime, and guess who did the showstopping final solo??

JACOB FUCKING COLLIER.

Look him up if you don't know. The other musicians I obsess over inspire me. This guy makes me want to quit.

#196#r196#rule#music#jazz funk#modal jazz#free jazz#jacob collier#music nerd#infodump#like massive autistic infodump#sorry again for this#oh btw#did you notice the four grammys behind him?#yeah

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

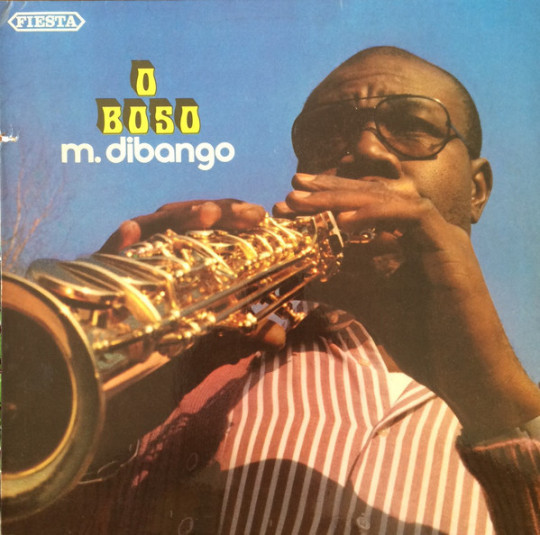

314: Manu Dibango // O Boso

O Boso

Manu Dibango

1972, London Records

In 2014, a Discogs user who goes by the handle nyuorican wrote on the page for Manu Dibango's O Boso/Soul Makossa, “Such an amazing album, musically it deserves to be like a $500 album easily, we're so lucky a lot were pressed up and kept circulating.” As criticism it’s not making Craig Jenkins sweat or anything, but it’ll probably be a more decisive assessment for anyone curious about Afro-jazz/funk of whether to listen than any of my blather. Original copies of stuff this good in this genre from this region almost invariably costs the same as a dog bred like a Spanish Habsburg, but thanks to the worldwide success of its pioneering single “Soul Makossa” this shouldn’t run you much more than $20. That’s a steal for music that grooves like this does.

youtube

Dibango wrote and arranged everything here and, as his note on the back cover makes explicit, his goal is to pay tribute to the common African roots of contemporary global Black music (jazz, soul, calypso, samba, etc.) via fusion. The Cameroonian sax giant surrounds himself with a crack band of African, Caribbean, and French jazz players, and the sheer variety of skills they bring to the table gives him great latitude to explore. The chords of “Dangwa” have the joyous lilt of African dance music but the bassline could be an R&B banger, while Dibango’s freaky sax runs are straight modal jazz. “Hibiscus” is soul jazz that would make Roy Ayers proud, Dibango’s horn blowing a lonely mating call while the casually funky electric piano, congos, and wacka-wacka guitar sketch an image of a hot city night after the clubs let out.

Of course, it’s “Soul Makossa,” an emissary of the makossa sound of Cameroon that predicts the disco wave, that towers over the rest in terms of influence, and it’s difficult to imagine how novel its minimalist percussive strut, echoing Duala-language ad libs, and deluxe horn hits must’ve sounded in the era. It’s one of those records where you can hear a bit of everything that was to come in Black music, from Chic to Kurtis Blow to Prince—partially because it’s been so frequently sampled that it literally is a bit of everything that was to come in Black music. But don’t sleep on opener “New Bell” either, a less hooky track in the same general mold, but one that rolls extremely deep.

314/365

#manu dibango#cameroon#cameroonian music#central africa#central african music#afro jazz#fusion jazz#jazz fusion#soul makossa#soul jazz#saxophone#music review#vinyl record#'70s music#african music

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Language of Jazz

The Language of JazzBrowse in the Library:Best Sheet Music download from our Library.Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!Varieties of JazzBop: Best Sheet Music download from our Library.Bossa Nova:Chicago Jazz: Cool Jazz: Dixieland Jazz: Free Jazz: Fusion: Hard Bop: Kansas City Swing: Latin Jazz: Modal Jazz:New Orleans Jazz: Smooth Jazz: Soul Jazz: Stride: Swing: Third Stream: West Coast Jazz: The Very Best Of Jazz | Jazz Songs Greatest Hits 2023 | Jazz Music Collection PlaylistBest Sheet Music download from our Library.Browse in the Library:

The Language of Jazz

In the same way that it developed its own musical voice, Jazz has also spawned its own vocabulary. Many of the expressions that define American English from its mother tongue stem from the African-African community, and specifically from Jazz musicians.

Louis Armstrong invented or played a large role in popularizing many of these. However, the great majority are not specifically musical, and therefore will not find their way into this glossary.

Here we have several dozen terms that you will encounter in your reading about the music—many of which are largely self-explanatory, and others which need a bit of extra clarification.

From its beginning, most Jazz musicians used the same terminology as other vernacular, American musicians, with terms taken directly or adapted from European models. And as the number of players who receive formal training increases, the adaptation of terms is usually exaggerated and the old Jazz lingo becomes more scarce.

Too often, the perception of a separate musical language of Jazz terminology is linked to some aspect of condescension toward the music or to latent racism or to just the plain old cultural inferiority complex that still plagues many American perceptions about American art forms.

A cappella: Performed with no accompaniment.

AABA: A common song form—usually thirty-two bars long, divided into four eight-bar segments—which consists of a musical theme (A), played twice, followed by a second theme (B), played once, followed by a return of the first theme.

Arco: In reference to a stringed instrument, played with a bow.

Arrangement: The reworking of a composition for a specific group or performer.

Atonal: having no established key or tonal center.

Beat: The basic metrical unit of a piece of music; what you tap your foot to.

Bitonal: Played in two keys at once.

Blue note: A tone borrowed from a minor mode and used in a major key. The effect resonates aesthetically as well as musically, since the association with minor sounds is “sad,” while the association with major sounds is “happy.”

Blues: An African-American musical form whose standard length is twelve bars. In its early vocal form, it comprised a four-bar question, repeated, and a four-bar answer.

Boogie-woogie: A blues-oriented piano style characterized by rolling left-hand figures—wherein the left pinky plays the note first, answered by the left thumb—and repetitive riffs on the right hand.

Break: When the rhythm section stops playing, and an instrument or instruments fill in the gap.

Bridge: The B section of an AABA composition.

Cadenza: In a performance, a section in which the tempo stops and the soloist plays without accompaniment.

Changes: The chords that define the harmonic structure of a song.

Chorus: One time through a song form.

Chromatic: Incorporating notes from outside a basic key or tonality.

Comping: The accompaniment of a rhythm-section instrument to a solo—usually refers to the function of a chorded instrument (piano, guitar, or vibes), but can also apply to others.

Consonance: Musical sounds that feel resolved.

Counterpoint: The simultaneous occurrence of two distinct melodies; more broadly, a point of contrast.

Diatonic: Referring to the notes that occur in the basic major and minor scales of a given key.

Dissonance: Musical sounds that feel unresolved and suggest resolution.

Double time: A tempo double the standard rhythmic base of a piece.

Downbeat: The first beat of a measure; also, any rhythm that occurs on the beat.

Fake: To improvise.

Front line: The horn section of a band, usually associated with New Orleans music.

Gig: A musical engagement.

Glissando: The gliding up or down to a given “target” note, without clearly articulating the notes along the way.

Harmony: The confluence of two or more tones.

Head: The melody of a piece.

Head arrangement: An interpretation of a piece that is made up on the spot and not written down.

Horn: Any instrument played through a mouthpiece.

Laid back: Referring to a rhythmic feeling that lags slightly behind the actual metronomic placement of the beat; usually in contrast to “on top.”

Lead: The primary melodic line of a composition.

Lead sheet: A musical manuscript containing the melody and harmony of a piece.

Legato: A way of phrasing notes wherein individual notes are not separately articulated.

Lick: A melodic phrase.

Melody: The succession of individual notes that define the primary shape of a composition.

Meter: The rhythmic base of a composition.

Mode: The seven scales that can be played on all the white notes of the piano, starting on one note and running up to the next octave.

Modulation: The change from one key or mode to another.

Motif: A musical unit that serves as the basis for composition through repetition and development.

Mute: An implement, usually wood, fiber, or metal, that is placed in the bell of an instrument to alter its tone.

Obbligato: A melody that accompanies the primary melody.

Off beat: A rhythm that is not placed on the downbeat.

On top: Referring to a rhythmic feeling that lines up with the metronomic placement of the beat; usually used in contrast to “laid back.”

Ostinato: A repeated phrase, usually played in a lower register, that serves as accompaniment.

Out chorus: The final chorus of a Jazz performance.

Phrase: A melodic sequence that forms a complete unit.

Pizzicato: In reference to a stringed instrument, plucked with the fingers.

Polyrhythm: The simultaneous use of contrasting rhythmic patterns.

Real book: A collection of lead sheets.

Register: The specific range of a particular instrument or

voice—usually high, medium, or low.

Rhythm: The feeling of motion in music, based on patterns of regularity or differentiation.

Rhythm section: Any combination of piano, guitar, bass vibes, and drums (or related instruments) whose basic role is to provide the accompaniment to a band.

Riff: A repeated, usually short, melodic phrase.

Rim shot: A beat struck by a drummer with a stick against the snare drum (commonly on the second and fourth beats of a measure).

Rubato: A musical device in which the soloist moves freely over a regularly stated tempo. The term has also come to be used to imply a temporary interruption of a piece’s regular tempo.

Sideman: Musician hired by a bandleader.

Solo: An episode in which a musician departs from the ensemble and plays on his own.

Sotto voce: Quietly.

Staccato: Articulated in a manner whereby each note is separated.

Stomp: A swinging performance.

Straight ahead: Performed within the conventional Jazz format—4/4 time, theme-solos-theme, and an overall songlike structure.

Tag: An extended ending to a piece, usually four or eight measures, that repeats the closing cadence.

Tempo: The rate at which the beat is played.

Theme: The central melodic idea of a composition.

Timbre: The characteristic sound color of an instrument or a group of instruments.

Vamp: The section of a tune where the harmonies are repeated, usually as an introduction or an interlude.

Variation: The development of a theme.

Vibrato: The alteration of a tone’s pitch, from slightly above that pitch to slightly below, usually used as an expressive device.

Voicing: The specific order in which a composer groups the notes of a chord; also, the assigning of these notes to particular instruments.

Varieties of Jazz

Bop:

All music is tied to its cultural context, and bop (also known as bebop) is inextricably bound to the social issues of the early 1940s, when young black musicians defined themselves against the pernicious remnants of minstrelsy that were buried deep in popular culture. Not only did they behave differently, but their music, in the context of its time, had a penchant for dissonance that many found off-putting. Gone, for the most part, were the straightforward melodies that distinguished the best of the American popular song.

Unlike previous styles of Jazz, much of bop seemed to have a “take it or leave it” attitude when it came to mass appeal. And in this regard, it aligned itself with other contemporary forms of art in other genres. This, of course, played into the hands of both audiences—those seeking to be “hip” and into something new, and those who liked to feel excluded.

Bop was basically an instrumental music, though it did have its vocal subgenre (with even more nonsense syllables and affectations than the worst excesses of the Swing Era).

The rhythm sections played in a more overtly aggressive fashion than before, with the drummer tending to predominate, shaping the general flow of the accompaniment.

The bop vocabulary was largely taken verbatim from the solos of saxophonist Charlie Parker and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and reveled in angular melodic shapes (“Shaw ’Nuff” and “Salt Peanuts”).

These solos were characterized by a great range, clean and virtuosic displays of technique, a penchant for unresolved chord changes, and a sense of great urgency. This is not to imply that these characteristics are also not to be found in earlier music—of course they are—but it’s a matter of proportion. And in the same way that it took awhile for Armstrong’s innovation to trickle down to the next generation, many of the first attempts to capture Parker’s and Gillespie’s style were immature.

Among the first to deal effectively with their new music were the trumpeters Miles Davis and Fats Navarro, the trombonist J. J. Johnson, the tenor saxophonists Warded Gray and Sonny Rollins, the pianists Bud Powell and Dodo Marmarosa, the vibraphonist Milt Jackson, the bassists Oscar Pettiford and Charles Mingus, and the drummers Max Roach and Roy Haynes.

Bop was essentially a small-group music (though Gillespie valiantly tried to sustain a big band for several years) played by a couple of horns and a rhythm section of piano, bass, and drums. There was little in the way of arrangements or interludes— once the theme was stated, a string of solos followed, with the theme being restated without variation at the end. With this eschewing of the compositional and ensemble element, a much greater demand was placed on the individual soloists.

Few of the acolytes of Parker and Gillespie had a comparable genius, and most could not sustain interest over long periods of time. But those who could bring a new electricity and risk taking to the music that could be thrilling. It is a decidedly unsentimental music, but bop in its most concentrated form does not lack for a want of emotion.

There were those who blended the best of the Swing Era with the new vocabulary, and they tended to be composer/ arrangers. Tadd Dameron and Gil Evans found ways to weave the new sounds into arrangements that restored some balance between the ensemble and the soloist. In many ways, their music formed a bridge between the aggressive extremes of some early bop music and the cool Jazz that was to follow.

Bossa Nova:

During the early 1960s, in the waning days of the pre-Beatles music world, there were a few bright moments when popular music approached the kind of sophistication that had been taken for granted in the ’30s and early ’40s. The bossa nova craze of the ’60s was one of those moments.

It was led by a handful of young composers and instrumentalists in South America who, inspired by pianist and composer Gerry Mulligan and other Jazz writers, strove to combine the best of modern Jazz with their own rhythmically propulsive native music. In the late ’50s, the partnership of guitarist/singer Joao Gilberto and composer Antonio Carlos Jobim created quite a stir in Brazil with their collaboration on “Chega de Saudade.”

The rhythms were descendants of the Brazilian samba, and it was frequently accented by the use of acoustic guitars. Though there were intimations of things to come and an intersection between Jazz and Brazilian music, it wasn’t until the American guitarist Charlie Byrd asked saxophonist Stan Getz to record the now classic album Jazz Samba that bossa nova (“new wave” in Portuguese) was launched. Getz became an international attraction based on his subsequent albums, with his biggest hit being Jobim’s “The Girl from Ipanema.”

The intimate, almost spoken vocal by Gilberto’s wife, Astrud, played a large role in the success of this recording.

Though its popularity has waned, there remains a large audience for bossa nova, and it continues to occupy a significant place in the Jazz marketplace. Two outstanding albums in the genre are Stan Getz’s Big Band Bossa and saxophonist Wayne Shorter’s Native Dancer (with Milton Nascimento).

Chicago Jazz:

The presence of New Orleans masters in Chicago in the ’20s such as King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, and the Dodds Brothers (clarinetist Johnny and drummer Baby) had a profound influence on a group of young, white musicians who wanted to find their own Jazz voices.

Their efforts reflected the heady atmosphere of their hometown, rather than the blues-inspired reflections of Oliver and company. The most significant fact about the Austin High Gang (some of them attended that institution) was that their role models were African Americans. Out of this group came the clarinetists Frank Teschemacher and Benny Goodman; drummers Dave Tough, Gene Krupa, and George Wettling; and the cornetist Muggsy Spanier.

(Black youngsters like drummers Sidney Catlett and Lionel Hampton and bassist Milt Hinton were also there in Chicago, picking up from the same men—but are conveniently overlooked by those who used the term “Chicago Jazz.”)

In later years, the bandleader/guitarist Eddie Condon became the personification of the Chicago school. He had a quick wit—and about the hoppers, he said, “They flat their fifths; we drink ours”) —and generated a lot of work for a long time. But nonetheless, this style remained confining for the handful of superlative players who were its prime exponents.

Musicians such as Pee Wee Russell, Roy Eldridge, Buck Clayton, Bud Freeman, Vic Dickenson, George Wettling, and many others spent the great majority of their later careers unfairly grouped in this category. On the rare occasions when these musicians were given the latitude to expand on a more varied repertoire with musicians of different stylistic stripes, the results were generally revelatory.

Cool Jazz:

“Cool” is the term used to refer to the reaction to bop, in which its frequently frenetic tempos and impassioned solos were replaced by a more reflective attitude. This was usually expressed in moderate tempos and in an instrumental style that drew heavily on the example of the great saxophonist Lester Young, though it must be stated that in lesser hands. Young’s style was occasionally distorted beyond recognition.

Nonetheless, cool Jazz was a welcome relief to the rapid degeneration of the bop style in inferior hands. And in the hands of masters such as trumpeter Miles Davis, baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, and pianist Dave Brubeck, it was a thing of great beauty.

The origins of the style, which emerged in the late 1940s, may be traced to Claude Thornhiirs big band, an ensemble which favored clarinets, French horns, and tuba. Many young musicians (who had revolved around saxophonist Charlie Parker and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie) were attracted to this sonority and to the innovative arrangements Gil Evans wrote for the band, adapting elements from classical music to Jazz ends.

With Davis as the primary force, Evans and others (trumpeter John Carisi, pianist John Lewis, and baritone saxophonist Mulligan) arrived at a band of their own that used the smallest amount of instruments necessary to get the tonal colors they desired—trumpet, trombone, alto sax, baritone sax, French horn, tuba, piano, bass, and drums.

The solos were integrated into the ensemble in an Ellingtonian fashion, and this forced the players to think compositionally (“Boplicity,” “Moon Dreams,” and “Jeru”). The band’s dynamic range was wide, but the group never shouted, and functioned best at a medium to medium-soft level that let all the instruments shine.

Though the band was a commercial flop and folded shortly after its debut, its recordings (originally 78s) were reissued the year after as an early LP, titled The Birth of the Cool—and the name stuck.

In the next few years, virtually any new Jazz style that was not overtly boplike was classified as cool.

This rather large umbrella covered the music of Lennie Tristano, Dave Brubeck, and Mulligan, all of whom, like the Birth of the Cool musicians, shared Lester Young as an inspiration—but each of whom came up with radically different results. Yes, there was a surface placidity to the sound of their bands, and in relation to Parker and Gillespie, maybe they were “cool,” but that’s as far as it goes.

Dixieland Jazz:

Most of the misinformation that has befallen New Orleans Jazz comes from what has become known as “Dixieland” Jazz. Here the emphasis was on banjos, straw hats, a clipped and frequently unswinging way of phrasing, and hokum. In the mid-forties, a group of white musicians on the West Coast began replicating the music of cornetist King Oliver and others, and this led a “New Orleans” revival —the primary exponent of which was a band led by Lu Watters. Their efforts, though occasionally amateurish, were sincere and respectful of their music’s roots.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Theme: "The Power of Dreams"

The theme I have chosen for this playlist is "The Power of Dreams." Dreams have always been a fascinating and deeply personal aspect of the human experience, and they hold great significance in our lives. Whether they represent aspirations, imagination, or subconscious desires, dreams inspire us to pursue our goals and reach for the extraordinary.

Classical/Traditional: Johann Strauss II - "The Blue Danube"

YouTube Link: The Blue Danube

"The Blue Danube" by Johann Strauss II is a classical waltz that evokes a sense of elegance and serenity. This piece is often associated with dreams of romance and enchantment. Its flowing melody and graceful rhythms create a dreamlike atmosphere, transporting listeners to a world of swirling ballrooms and magical encounters.

Rock: Queen - "Bohemian Rhapsody"

YouTube Link: Bohemian Rhapsody

"Bohemian Rhapsody" by Queen is an iconic rock anthem that defies conventions and pushes the boundaries of musical expression. This epic composition weaves together multiple sections, ranging from a haunting ballad to a thunderous hard rock climax. The lyrics, open to interpretation, take the listener on a surreal journey that mirrors the unpredictable nature of dreams.

Jazz: Miles Davis - "So What"

YouTube Link: So What

"So What" by Miles Davis is a modal jazz composition that embodies the improvisational spirit of dreams. The piece features a distinctive, cool jazz style and revolves around a simple two-chord progression. The dreamlike quality of "So What" lies in its ability to evoke a sense of tranquility and introspection, offering listeners a space to wander and reflect, just as one might in a dream state.

Hip Hop/Rap: Kid Cudi - "Pursuit of Happiness" ft. MGMT

YouTube Link: Pursuit of Happiness

"Pursuit of Happiness" by Kid Cudi featuring MGMT is a hip hop/rap track that delves into the complexities of pursuing happiness and finding fulfillment. The song's introspective lyrics and introspective beats capture the longing for a better life and the constant search for contentment. The melodic hooks and catchy chorus contribute to the emotional impact of the track, providing a balance between contemplation and the desire for joy.

Folk: Simon & Garfunkel - "The Boxer"

YouTube Link: The Boxer

"The Boxer" by Simon & Garfunkel is a folk song that speaks to the struggles and resilience inherent in following one's dreams. The lyrics tell a story of perseverance, depicting the journey of a boxer who faces challenges but remains determined to succeed. The acoustic guitar-driven composition is accompanied by harmonies that emphasize the emotional depth of the narrative.

Electronic: Daft Punk - "Instant Crush" ft. Julian Casablancas

YouTube Link: Instant Crush

"Instant Crush" by Daft Punk featuring Julian Casablancas blends electronic and indie rock influences to create a dreamy and nostalgic atmosphere. Through its fusion of electronic and rock sounds, "Instant Crush" explores the intersection of dreams and human connection, offering a sonic landscape that resonates with the complexities of the heart.

By exploring the theme of "The Power of Dreams" through various genres, this playlist celebrates the transformative nature of dreams and the emotional depth they encompass. From the classical elegance of "The Blue Danube" to the boundary-pushing rock of "Bohemian Rhapsody," each song embodies different aspects of dreams, capturing their evocative power through melodies, structures, and affective content.

0 notes

Photo

Amaro Freitas - Sankofa

(Avant-Garde Jazz, Post-Bop, Samba-Jazz)

Amaro Freitas' third album is his most challenging yet, an unrelenting collection of colorful samba-jazz and post-bop experimentation. And yet, it's rarely much more than that, leading to much of Sankofa being too long and lacking much sensory information to engage with as a listener.

☆☆½

One of the most technical contemporary jazz artists, Brazil's Amaro Freitas has presented listeners with an intriguing offer from the start: just how tight can you wound up a song until everything has to combust? It's that tension that drove his first two albums to success, these careening mazes of Samba rhythms, crunchy chord progressions, and a bustling energy that took listeners on some of the most exciting paths of the 2010s.

Sankofa, his first record of the new decade, tones all those elements down in favor of post-bop atmospherics and more unpredictable fates for his songs. It's fascinating to watch how Freitas approaches this new sound, even if some of its aspects I anticipated even before listening: melodic motifs are pulled as far as they can, rhythms (largely led by Hugo Medeiros drumming) emphasize hypnosis and repetition to a fault: the more modal leanings of post-bop appear in how Freitas' hand slinks up and down the piano. It loses some of the unexpected bite of his early work, but with his knowledge and excitement to experiment in works before there's a clear path to success throughout Sankofa.

But rarely is Freitas able to find it. His keyboard playing is the core of Sankofa, but it wanders nowhere throughout much of the album. While I appreciate the way he plays with melody, like how the title track's main mid-octave motif is attacked by dissonant right-hand reaches and trickling chords, it never seems to actively move towards each new idea. They appear and disappear on a whim, and if he leaned further into the more dreamy side of jazz this could work, but there's too much energy instilled into his playing for it to end up so static. Oddly, when the tempo clambers on more romantic cuts Vila Bela and Nascimento, it's a gamble whether or not the song starts to disappear entirely (in the case of the former, I had to restart the song because I wasn't sure whether anything was still happening). Feeling comfortable in your musical position isn't necessary for jazz like it might be for other genres, you might have to get a little anxious while trying something out, but it needs to be confident. Throughout Sankofa, that confidence is uncommon.

When it does, I see what this album could have been. When the rumbling swarm of keys moves into this funky fusion dance on Ayeye, the more forceful rhythms of his past work return to give Freitas an idea of how much power needs to be put into his playing at any given moment. With the aforementioned Nascimento, Freitas embraces the aerial for a soft, yet fulfilling finale that lets all the color in his playing slowly bleed into aquatic silence. With a whole host of disappointing songs surrounding it, though, it's difficult to come back to Sankofa in full, seemingly so disinterested in getting you invested that you're forced to go more than halfway to get even a little from it.

#amaro freitas#sankofa#far out#afro-jazz#avant-garde jazz#experimental#jazz#jazz fusion#post-bop#samba-jazz#2021#5/10

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calvin Keys – Shawn-Neeq (Black Jazz/Real Gone)

youtube

Sidestepping instrument(s) suitably suggested by his surname, the young, Nebraska-born Calvin Keys cottoned instead to the guitar. His sound was one steeped in the soul/spiritual jazz of his era and he gigged with the likes of Ray Charles, Ahmad Jamal and Sonny Stitt. Those plum stints parlayed into a handful of dates as a leader, of which Shaw-Neeq from 1971 was the first. Pared to just a quintet, the band deftly balances popular influences with an underlying jazz pedigree that sits comfortably with the sort of instrumental sessions that Keys’ heroes like Grant Green and George Benson.

“B.E.” sets a brooding funk scene swiftly on an undulating modal vamp with the combined electricity of strings and keys and backbeat-calibrated cans coalescing into a surging collective groove. Owen Marshall wails and bellows on an uncredited bass clarinet in the cracks, contrasted by Larry Nash’s cooler keyboard musings mid-piece. Keys switches between lead and support with a viscous fluidity. “Criss Cross” is a more conventional jazz venture with repeated riffs bounced rapidly against electric piano and bass ballast. Drummer Bob Braye gets a little too splashy on his cymbal accents, but the sum becomes another crowd pleaser packed with the leader’s plectral poise and precision.

The title track settles into a ballad bag made even plusher by the blend of Keys’ delicate chords and Nash’s pulsing swells. Marshall’s relaxed flute fills apply icing to an already openly amorous aural cake. The batter used is blatantly sentimental, but Keys’ audible conviction keeps it from crossing over into cloying artifice. “Gee-Gee” and “B.K.” maintain the theme of dedicatory compositions with the first benefiting from an infectious boogaloo bassline and luminous comping from Nash behind another chords-congruent Keys’ confection. Keys engages in an even more expansive conversation with the latter’s keys on the closer, a loping, arpeggiated excursion that carries more than faint echoes of Miles Davis’ contemporaneous fusion forays. Lean in overall duration, the album still delivers a potently satisfying time capsule.

Derek Taylor

#calvin keys#shawn-neeq#black jazz#guitar#larry nash#bob braye#dusted magazine#albumreview#derek taylor

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#finishedbooks The Jazz Tradition by Martin Williams. Picked this up from the library as one of the last jazz books they had that I hadn't read. A bit older, written at the close of the 60s it covers by chapter artists from Jelly Roll Morton to Ornette Coleman...the perfect zeitgeist really. He does this on an interesting idea of following the rhythmic changes over the decades to provide insight into its underlying evolution. Something that was largely noticeable in the transition from swing to bebop in terms of the music's danceability and thus popularity. Buddy Bolden is usually considered the first jazz player but no recordings of him exists, so it was the New Orleans brothal house player Jelly Roll Morton who became the first jazz arranger. But it was thereafter with Armstrong who came to define the art and shifted it to a soloists medium. I agree with the author's accord that after 1933 there was nothing sonically innovated from Armstrong despite what Ken Burns Jazz made him out to be with maybe the exception of that Ella Fitzgerald record that is easily more iconic than original. Skipping around there was a nice small section on Coleman Hawkins who I agree could have been considered the best during 39-44' starting with his masterpiece, Body and Soul. The author only features one vocalist in Billie Holiday which I didn't mind as I am bias she is from Baltimore. But I liked her because out of the four greatest jazz vocalist I always felt she did the most with the least as Fitzgerald and Vaughn's tone range was vastly greater and Simone was a virtuoso on an instrument in addition to her voice. Holiday just injected herself into those ballads that held a truth that was different. My favorite in Charlie Parker was covered as he figured out you could play any note in the scale and resolve it within the chords so that it would sound harmonically right this essentially was his contribution as it meant...he could fly. In the process he wiped the cliches of the swing era for something entirely new...bebop. Monk was properly held in the book. I always find him the most logical yet the most fun. He plays each note on the piano as though astonished or joyfully pleased with the difference from the last one. The author brought a new found appreciation to Monk's solo records that I had previously reserved for Art Tatum...and that Solo Monk record is fine but the Complete Monk Alone record is the one. Most informative was Ornette Coleman's section as most get caught up in the free jazz label that for instance on the Stockholm trio records (author mistakes and says Denmark) that sees him pulling out a violin and trumpet in addition to alto and tenor saxophones getting caught up in the implied chaos (although they are functionally effective parts of a singular, unlike fusion)...book made me realize how orderly of a player he is...a logical melodist. The author in implying this made me realize immediately the parallels between him and Thelonious Monk as he is orderly along traditional lines while not inviting a-harmonic chaos like say a late Coltrane. Which is also another and final point here, Coleman's solos are complete... while he avoids conventional resolutions...he also avoids that didactic droning sound of other modal improvisers. In comparison to Coltrane who is decidedly more exploratory in his solos, which is also fine because he just seemed more interested in discovery than making finished statements like a writer occupied with heightening vocabulary with which future sentences, paragraphs; and essays might be built upon. He had me really going back into Monk's solos and Coleman's work...for the latter in free jazz to use a Joyce quote, "better sees the darkness shining in the light." A lot of beauty, affirmation, and hope.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the 17 August 1959 Miles Davis released Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz record of all time, and, many would argue, the best jazz album of all time. Over sixty years later it sells an average of five thousand copies a week.

Just over a week later, Miles was having a smoke outside the Birdland Jazz Club, Midtown Manhattan, during a break. An NYPD officer approached him and told him, ‘You can’t stand there. Move on.’ Miles responded ‘Move on? For what? I’m working downstairs.’ Gesturing to the door, he continued, ‘that’s my name up there – Miles Davis.’ The officer replied, ‘I don’t care where you’re working, I said move on!’ and began attacking Miles. Another officer came up behind Miles and struck him on the head with a baton, leaving him bloodied and bruised.

To quote Dr. Cornel West, ‘Black music was the Black response to being terrorised and traumatised’. The concept of being brutalised by police after creating one of the most important works in music history is entirely surreal for white people. Imagine if the Beatles had been beaten up just after releasing Abbey Road. But for black musicians this is a constant concern and reality. Miles Davis recovered from this attack and went on to have an illustrious career, pioneering genres such as Jazz Fusion, Modal Jazz, and releasing albums which blew everything else out of the water. However another black jazz musician was not so lucky. Bud Powell, a jazz pianist, was brutally beaten by a police officer at the age of twenty. After the incident Bud was entirely incoherent and in great pain. Days passed but his condition didn’t improve, and he was institutionalised for several months. Never fully recovering he suffered from alcoholism, drug addiction and mental breakdowns over the twenty-one final years of his life. To quote Roy Haynes, a famous jazz drummer, had Powell lived longer and been better treated, “there’s no telling what he would have developed into”.

The Real Book

Jazz music was and still is often taught quite differently to other types of music, such as rock and pop. Look up on YouTube how to play any rock song on any instrument and you’ll find it without a problem – the same however can’t be said for jazz. You may find a crude overview, but you won’t find anything in-depth. The history of this can be traced back to segregation. Jazz music was often learned in the form of a master – pupil style, as black musicians wanted to protect their creations. Not from a white kid sitting in his bedroom playing Autumn Leaves or Take the A Train, but to protect it from white musicians who took their work and making a lot of money off it – of which they’d never see a penny.

The Real Book is a collection of sheet music ‘approximations’ for jazz standards – many songs are in the wrong key, contain the wrong chords, etc. though many beginners buy this book as a way to get started. But upon closer inspection it becomes apparent that the songs which are most incorrect are the songs written by black musicians, as almost all of them refused to give out their music to anyone except a close-knit group. Often times it wouldn’t even get outside of a quartet or quintet. Take for example Led Zeppelin, a group of white musicians who (it’s no secret) stole most of their music from black musicians, paid them little to no money and gave them no recognition. For example, one of Led Zeppelin’s most popular songs ‘Whole Lotta Love’ was a blatant rip-off of Muddy Waters’ song ‘You Need Love’. This is exactly what the jazz musicians were so fearful of and worked to prevent from happening.

Is Jazz Political?

Some may believe that because the vast majority of jazz is instrumental – especially some of the most popular records of the swing, bebop and hardbop eras – that jazz couldn’t possibly be political. How could it be if there are no words?

On 15 September 1963 the KKK bombed a church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young black girls and injured twenty-two people. A few months later John Coltrane, arguably the best saxophone player of all time, wrote a song called ‘Alabama’. This haunting piece directly channels the feelings he had felt when he read about the attack. The song is slow and tense and, though there are no words, there is a visceral feeling of despair. Insofar as jazz is a powerful means of expression for oppressed people it is inherently political.

source

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reviews 334: SiP

One of my favorite releases so far this year, and indeed of recent memory, is Leos Naturals, a forthcoming cassette on Not Not Fun Records written and produced by keyboard explorer Jimmy Lacy, otherwise known as SiP. It’s rare that an album so perfectly intersects this many of my favorite styles and sounds, and across the nine tracks, my mind is carried towards the minimalist flights of Terry Riley and the organic music of Don Cherry; the spiritual meditations of Alice Coltrane and the interstellar journeys of Sun Ra; the ebullient kosmische of Manuel Gottsching and the dreamspace ragas of the Theatre of Eternal Music; the pastoral psych folk of Woo and the spaghetti western scores of Ennio Morricone; and the rich lineages of post-rock and experimental music in Chicago…things like Tortoise, Brokeback, Natural Information Society, Mind Over Mirrors, and Bitchin Bajas. More remarkable still is that Lacy does almost everything with a minimal palette of organ and synth, using his keys and fingers to create kaleidoscopic spiral patterns, multi-layered fire webs, and LSD tracers of every possible color. Often times the left hand holds down a narcotic bass groove reveling in shades of Saharan jazz, West African highlife, and bubbly sunshine dub while the right hand explores mystical sonic landscapes which, in addition to classical raga, minimalism, modal jazz, and krautrock, also touch on Ethiopian psych and a range of sounds from various Native American folk traditions. And though the tracks are often solo organ journeys carried by primitive loops of hand drum exotica, they are sometimes accented by summertime kalimba storms, seaside melodica breezes, and multi-faceted bass clarinet performances, which vary between lounge romance, rainforest mystery, big band nostalgia, and free jazz shaman magic.

SiP - Leos Naturals (Not Not Fun, 2020)

The percussion of “Amitabul” rolls through the desert with a subdued horseback gallop while subsonic basslines evoke warming dub liquids. Clustered keyboards spread across the spectrum like mirage sparkles and solar organ leads weave lullaby ragas and shake charmer serenades while tambourines and sleigh bells jangle in the distance and sometimes, the organ melodics are swapped out for gentle sunshowers of kalimba. Elsewhere, P. Prezzano’s melodica blows like a wheezing wind, with all distinction between melodica and organ disappearing as the two instruments blur into a smoldering cloud of psychedelic sound, and towards the end, we cut unexpectedly into tribal fire dance mysticism, with hand drums beating urgently, ringing bells filling all space, and Ben Chasny-style acid vox calling to the ancestral spirits. The percussion of “Pure Horse” mimics the sounds of clopping hooves against sunbaked stone while basslines slither through North African jazz descents. Repeating keyboard riffs execute a drunken delirium dance alongside the horse-gallop groove and everything proceeds according to Lacy’s own feverish dream logic, with acid-fried leads alighting on flights of spiritual jazz fantasy and Arabian desert exotica that sometimes mesmerically track with the basslines. Best of all, dueling keyboard leads sitting somewhere between a ceremonial wood flute and a rainforest pan-pipe occasionally sing overhead…their esoteric folk harmonies lifting the soul towards astral ecstasy. “Ras Cosmos” sets bells ringing beneath some approximation of a phaser-smothered zither…like an elven future spirit playing a strange psaltery strung with electrified strands of crystal, where each pluck swirls into a self-contained vortex. There’s a touch of Japanese traditional music as the spageage koto evocations are accompanied by E. Juhl’s cloudy clarinet abstractions, and at some point, shakers and floor toms give the groove a shambolic lurch as the clarinet works through big band jazz melodies from a bygone era. And though the whole thing seems to approach the drunken exotica of Haruomi Hosono, the moment is all to brief, for we soon return to blues-soaked space harp psychedelia and pastoral woodwind ambiance.

“Malabar” ends the A-side with desert caravan hand percussions bopping over a frog-squelch bass pulse while kalimbas flutter in a seaside breeze. Juhl’s clarinet approximates elephant shrieks and jungle mating calls until harmonious organ chords billow into the mix…like a warming blast of wind and sand. Shakers dance alongside a snaking synth lead awash in Indian ocean magic before the mix gives over to clarinet exotica…like Woo exploring a coastal oasis. And so it goes for the rest of the track, a sort of dream dance progression between clarinet balearica and passages dominated by immersive organ wavefronts and joyous raga-lead explorations, the latter of which increase in intensity as things progress….shakers hissing like snake tails, tambourines shaking out golden hazes, ethnological drums dancing wildly beneath an idiophonic rainfall, and Lacy’s keyboards climbing towards the sun with joyous abandon, his bleating leads and shamanic spirals falling over themselves and creating multi-layered tapestries of free jazz intensity, high life positivity, and raga complexity. There’s even a climax of wall-of-sound psychedelia where whistles overblow into feedback ecstasy while keyboards transmute through crazed LFO oscillations and hyperspeed fractal dances. Then on B-side opener “Electric Palm Study,” a shuffling psych rock groove is sourced from an old organ drum machine…a sort of primitive rhythm box kosmische, with basslines bouncing through acid-colored flower fields. And as spindly keyboard riffs jangle in the sunshine, the mix overflows with malfunctioning computronics, further overblown whistling, and garbled broadcasts from faraway star systems. The mangled electronic accents continue in “Sparkling Spur,” which establishes a loping groove built from tom-tom rhythmics, galloping bass riffs, and muted shaker clicks…a horseback trot through a seaside saloon town, or perhaps a journey atop a bouncing burro, riding the crest of a dune while sparkling waves crash against a white sand beach. Sunbeam synth leads rise towards the sky, with touches of spaghetti western and Ethiopian folk radiating in all directions, and towards the end, as these Afro-coastal and American western melodies converse across the spectrum, the crazed feedback electronics settle into synthetic birdsong.

In “Chicago Dream Center,” organ basslines move with a spiritual bop…a sort of Arabian desert fantasy sway. As we give over to a cosmic jazz groove awash in modal organ spirituality, one that evokes for me Alice’s late 70s classic Eternity, tambourines create glimmering webs and minimalist keyboard patterns splay out in each ear. It’s an eye-closed revery of mystical inspiration, one that pushes even closer towards transcendence as Juhl’s bass clarinet begins blowing waves of ecstatic fire across the stereo field. Elsewhere, we move away from free jazz intensity and journey towards the realm of dreams, as pan-pipe and forest flute leads invoke mystical visions of coyotes howling at the stars. And all throughout the mix, weird gusts of metallic wind blow and eventually subsume everything, until all that remains is sparse wind chime resonance. We move more directly into the Coltrane universe with the tributary “Alice,” though it could also rightfully be called “Herman.” Stuttering bass patterns eventually release into sustaining warmth…like be-bop rendered as otherworldly ambient in a way pulling my mind to Sun Ra’s “Exotic Forest” and that similar feeling of exotica space jazz threatening to vaporize at any moment. Juhl blows cool noir breezes via clarinet, the sounds filmic and emotionally affecting…like the twilit heroin journeys of Bohren & der Club of Gore’s…and all the while, an e-piano smothered in liquid tremolo moves between overflowing chord clusters and percussive runs up the scale. Tambourines and ceremonial bells generate sprays of sparkling metal that bring further touches of Alice, though the rhythms flow in and out of focus like a daydream. There are also moments where vents in the ground open up and spew forth neon space vapors and LSD-smothered fusion runs, which then swim drunkenly towards the stars. “Rainbow Kids” closes Leos Naturals with ecclesiastical keyboard waves and clattering chimes while overhead, Lacy’s organ does a fantastic impression of a tenor sax. It’s a transition from the world of Alice Coltrane to that of John, resulting a spiritual faux-sax paean awash in atmospheres of gospel and old world blues.

(images from my personal copy)

#SiP#jimmy lacy#not not fun#not not fun records#chicago#leos naturals#p prezzano#melodic#e juhl#bass clarinet#spiritual jazz#highlife#ethiopian psych#psychedelia#psych#acid#minimalism#post-rock#balearic#tropical#desert#cinematic#jazz#alice coltrane#sun ra#album reviews#tape reviews#cassette reviews#cassette tape#2020

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jazz Fusion Chords:How to create them from scales

CLICK SUBSCRIBE!

Hi Guys,

Today, a look at how to create colourful and interesting jazz/fusion chords:

Because, we are dealing with jazz/fusion we will manipulate a scale in modal form. This will be C Mixolydian:

Now, let’s add one note above each note of the mode and create 3rds. [Here we can hear the mode in double stops].

Now, we will add another note a 5th above the root and create…

View On WordPress

#chord creation#chord scales#chord sequences#chords#creating chords#dorian chords#Download#Examples#explained#flat 5ths#free pdf#fusion#fusion guitar#guitar#guitar chord scale#harmony jazz#how to#jazz#jazz fusion#jazz guitar#jazz modes#lesson#Major 3rds#melodic minor#mixolydian chords#modal chords#music#music notation#music tab#quartal harmony

1 note

·

View note

Photo

New Post has been published on https://freenews.today/2021/03/22/sxsw-came-back-with-genuine-joy-here-are-15-of-the-best-acts/

SXSW Came Back With Genuine Joy. Here Are 15 of the Best Acts.

JADE JACKSON and AUBRIE SELLERS Two Los Angeles-based roots-rock songwriters with solo careers decided to write together during quarantine, and emerged as a duo. Their video set for SXSW, with a partly masked backup band, was their first public performance. They leaned into electric Southern-rock stomps, shared modal harmonies, and introduced a new waltz about a year without concerts: “I want to go back to the way it was before we had distance between us,” Jackson sang.

MILLENNIUM PARADE Live Nation Japan sent SXSW a concert-scale production with the melancholy synth-pop group D.A.N., the cheerfully arrogant rapper-singer Awich (surrounded by dancers) and the full-scale overload of Millennium Parade, a large band led by Daiki Tsuneta with two drummers, plenty of computers and keyboards and multiple lead singers, male and female. It reached back to the bustling, horn-topped R&B of Earth, Wind & Fire, added latter-day sonic heft and occasional rapping, and surrounded itself with a video barrage that rocketed it into a “Blade Runner”/anime futurescape. In “2992,” between a bruising bass line and a fluttering orchestral arrangement, Ermhoi sang, “In this life we live, everyone is made to feel confused” — confused, perhaps, but exhilarated.

HARU NEMURI The Japanese songwriter Haru Nemuri started her set, which looked like a one-take video, as if it were going to be soft and gauzy. She was alone in a room and rapping in a near-whisper over a looped choir of women’s voices, with hints of Björk and Meredith Monk. But when she suddenly opened a door and ran upstairs to a rooftop, hard-rock guitars and a drumbeat came blasting in, and her vocals turned to a scream. Her next song was a shouted rap-rocker named “B.A.N.G.” and, after a breathless speech about wanting her music to “create something precious on this planet,” she was twirling and rapping at top speed over a galloping beat and dense organ chords; the song’s title, and chorus hook, was “Riot.”

ONIPA Based in Sheffield, England, Onipa drew on music from across Africa. Onipa means “human” in Akan, a language in Ghana, and its music had roots in Ghana, Congo, Senegal, South Africa, Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Algeria, along with hints of the African diaspora. The lyrics were in English, while the grooves were fusions that put momentum first.

Source

0 notes

Photo

Thought by many to be among the most revolutionary albums in jazz history, Miles Davis' Bitches Brew solidified the genre known as jazz-rock fusion. The original double LP included only six cuts and featured up to 12 musicians at any given time, some of whom were already established while others would become high-profile players later, Joe Zawinul, Wayne Shorter, Airto, John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland, Don Alias, Bennie Maupin, Larry Young, and Lenny White among them. Originally thought to be a series of long jams locked into grooves around keyboard, bass, or guitar vamps, Bitches Brew is actually a recording that producer Teo Macero assembled from various jams and takes by razor blade, splice to splice, section to section. "Pharaoh's Dance" opens the set with its slippery trumpet lines, McLaughlin's snaky guitar figures skirting the edge of the rhythm section and Don Alias' conga slipping through the middle. Corea and Zawinul's keyboards create a haunted, riffing modal groove, echoed and accented by the basses of Harvey Brooks and Holland. The title cut was originally composed as a five-part suite, though only three were used. Here the keyboards punch through the mix and big chords ring up distorted harmonics for Davis to solo rhythmically over, outside the mode. McLaughlin's comping creates a vamp, and the bass and drums carry the rest. It's a small taste of the deep voodoo funk to appear on Davis' later records. Side three opens with McLaughlin and Davis trading fours and eights over a lockstep hypnotic vamp on "Spanish Key." Zawinul's lyric sensibility provides a near chorus for Corea to flit around in; the congas and drummers juxtapose themselves against the basslines. It nearly segues into the brief "John McLaughlin," featuring an organ playing modes below arpeggiated blues guitar runs. The end of Bitches Brew, signified by the stellar "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down," reflects the influence of Jimi Hendrix with its chunky, slipped chords and Davis playing a ghostly melody through the funkiness of the rhythm section. https://www.instagram.com/p/B4l-pLlgTiL/?igshid=11c9zhj8kago2

0 notes

Text

#5 ‘So What’ by Miles Davis [Jazz]

Genre: Modal Jazz

Track: So What

Composer/ Artist: Miles Davis

Introduction: Jazz has come to be one of the most influential music genres of the last century. Jazz has its roots in African-American communities of New Orleans in America. The genre is said to have begun in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and takes influence from both Blues and Ragtime. The end of World War I, the newfound freedom of African-Americans, the sharing of cultures, and the increase in leisure time and mass media all contributed to the rise of Jazz music. The likes of New Orleans Jazz (1910s), Gypsy Jazz (1930s), Bebop (1940s), Jazz-rock fusion (1960s) and Smooth Jazz (1980s) all share broad characteristics such as improvisation, swing, blue notes, call and response vocals and polyrhythms. However, all these sub-genres also put their own stamp on the genre through various compositional, technical and stylistic choices.

The track we will discuss here, So What is a quintessential piece of Modal Jazz, a musical style born from the ashes of Bebop in the late 1950s which celebrates simplicity, more organic structures, relaxed tempi and whimsy but also gives rise to a wider palette of melodic colours since modes bring new harmonic structures into the aural mix.

Themes: Laid Back, Relaxed, Light-footed

Texture: Featured on Miles Davis’ classic 1959 album Kind of Blue, the opening track So What is by all means a Jazz standard. Texturally, this track comprises of trumpet, piano, drums, upright bass and tenor and alto saxophone. The piano establishes the tonal context of the track with a two-chord motif. The upright bass enters and delivers its melodic voice in call-and-response. When the brass first enter they play in monophonic voicing supporting the piano. The call-and-response interaction with the bass persists. On bar 42 the call-and-response and monophony gives way to a 3-part polyphonic section with bass, piano and trumpet playing separate interweaving melodic lines with the trumpet taking the lead. This polyphonic structure continues through the solo section with the trumpet being replaced by tenor and alto sax and finally piano (where the brass all being once again to sound a melodic line in monophonic fashion). After the solos the piano returns to the main riff/motif along with the brass and the track finishes as it started - in a call-and-response between the bass and the other instruments.

Dynamics: So What follows the tradition of a lot of Jazz in its expressive use of dynamics. Probably the most notable use of dynamics in So What occur with the piano. The iconic chord voicings which repeat throughout the track use dynamics to convey a sense of energy and light-footedness. On an overall compositional level the dynamics shift from mf in the intro section to f when the solos begin. The track returns to mf when the piano takes its solo. Here the drummer changes to playing the rim of the snare. The brass also come down in level. The track then drops further to p and again to pp before fading out.

Timbre: So What can be seen to showcase a fairly traditional grouping of Jazz timbres. The piano on the track features throughout and is delicate, rich and for the most part dry and upfront. The upright bass is full bodied and rounded sounding but at the same time has some distance and openness. The drums sound crisp, woody and airy which adds to the laid back feel of the song. The trumpet is focused but not harsh. It exhibits a fairly rounded and mellow timbre. In comparison the tenor and alto saxophones are much more piercing, reedy and bright and command the attention of the listener when they play full voice.

Instrumentation/use of Technology: Technology both in recording and instrumentation in the 1950s was very different from current conventions. So What was recorded on three-track tape at Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio in New York City using entirely acoustic instrumentation. The studio was a converted Greek Orthodox Church. This large space with its high vaulted ceilings plays a large part in the sound signature of So What as close micing would not have been used. Unlike the now common practice of recording instruments one by one, the ensemble would have performed together paying close attention to their distance from microphones and their level in relation to the rest of the musicians. Songs were performed in one take with little practice or rehearsal. All of these elements combine to give a sonic signature which is very organic and unmediated.

Melody: Modal music develops thematic material through rhythm and melody rather than through chord progressions. The melodic backbone of the piece is the compelling quartal 2 chord riff introduced by the piano. These pentachords are a whole step apart. The basic interval is the perfect 4th (in some cases ♭4 and ♯4). The simplistic foundational progression gives freedom for improvisation in terms of melody. In terms of the solo section which takes up much of the track, the modal structure manifests in a complex and ever moving piece of music which modulates from D Dorian to Eb Dorian. Davis’ solo can be marked as very melodic with thoughtful phrasing, whereas Coltrane uses a harder/ scalar approach playing faster and leaving less space.

Notation (Piano chords):

Time Signature: 4/4

Tempo: The tempo of So What varies to some degree but as a while the track has a moderate swing feel and plays at roughly 134bpm.

Tonality: As mentioned earlier, instead of musical ideas which move away from and back to the home key, or tonic (which may be major or minor), modality implies a series of transposable interval relationships. Ideas are developed via changes in the character of the mode (e.g. C Dorian to C Mixolydian) or in modulation to other modes. This amounts to a simplistic tonal foundation on which Modal Jazz songs are built. So What follows a 32 bar AABA structure (16 bars in D Dorian, 8 bars in Eb Dorian and a further 8 bars in D Dorian).

Structure: The track intro is played by the piano and bass. The piano drops out and the bass plays a line solo before the piano and drums enter. The brass then enters, playing the melody in a call-and-response fashion with the bass. After one 32 bar chorus each performer takes an extended solo in the following order: trumpet, tenor sax, alto sax and piano. During these solos the other brass players do not play. Following this the melody line is played for a chorus. The piece ends with bass, piano and drums and fades out.

0 notes

Text

Jazz in the Postmodern Age

Jazz music is an idiom in which the griot, or storyteller, contextualizes contemporary events with an individualized inflection to connect with their immediate audience. Jazz as a process continued the griotic tradition in America, conventionally understood as emerging from the Mississippi Delta regions, most significantly cosmopolitan New Orleans, and migrating into northern metropolitan areas such as Chicago, Harlem, and St. Louis. Jazz was only the next in a developing language occupying a place in the storytelling continuum which has included Blues, Spirituals, Gospel, Blues before it, and succeeded by Rhythm & Blues, Rock & Roll, Afro-Cuban, Soul, Funk, and currently Hip-Hop.

“Jazz” as a descriptive label was first used to identify the sounds of Lost Generation pioneers such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, providing a distinctive voice to the Prohibition Era speakeasies, and quickly gaining the attention of the next eager cohort who were listening to any and every note these masters presented on the new technology of mass communication, radio.The GI Generation collectivized and commercialized Jazz.

Victorious in WWII, they were encouraged by such notable psychologists as Dr. Spock to allow their postwar children latitude to “discover themselves” in youth and subsequently The Baby Boomers have remained the prophets of the early millennial years. Among the repercussions of this licensed Boomer introspection was a preoccupation with the self that in 1976, journalist Tom Wolfe coined as the “Me” culture.

Concurrent with the post-JFK Consciousness Revolution emerged a philosophical movement that was coined “Postmodernism.” Deconstructionists such as Jacques Derrida became preoccupied with language and semiotics, challenging how perception is communicated, and facilitating a relativism that continues to keep our modern culture in a polarized, chaotic state of existence.

Technological advances as represented by digital instruments and fascination with the synthetic are material representations of our current Postmodern Age.

undefined

youtube

By the late 1950s, what was at one time considered “street music” was formally adopted into curricula of higher institution, validating the Jazz process as deserving of formal study and appreciation. This inclusion was just another event that elevated the urban community in the decades following the 1920s Renaissance. It was the Boomers who were the recipients of these initial academic adoptions of urban culture, and by the late 1960s the zeitgeist was characterized by that which stimulated inner-directed searching: free speech, LSD, free love, cults, aerobics, Moonies, etc. The decolonization of the British Empire enabled the global influence of Eastern Transcendentalism, and by the mid-1960s, a new Awakening was driving society.

Martin Luther King, Jr. emulated approaches practiced by Gandhi, composers Terry Riley, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich introduced music in drone-like fashion called Minimalism, and Miles Davis moved into a phase of aleatoric, collective improvisation first liberating harmony, then form, and finally adopting new technology to move Jazz convincingly into the Postmodern Age.

Inspired by his conversations with George Russell, who proposed the Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization (1953), Davis assembled a legendary sextet that recorded the landmark album Kind of Blue in 1959, utilizing Russell’s Modal theories by reducing composition to a scales (horizontal melodies) as opposed to chords (vertical approaches to melody), and creating static accompaniments as the foundation for improvisation.

undefined

youtube

Davis would follow this ensemble with his second important group that experimented with compositions such as “Nefertiti,” based on a looping melody rather than a formalized structure that was the musical equivalent to M.C. Escher’s tessellations and Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup paintings.

undefined

youtube

And then in the late 1960s, a thoroughly postmodern mindset influenced Davis to present collective improvisation with electric instruments, thus launching the Jazz-Rock Fusion genre. His projects, Bitches Brew, A Tribute To Jack Johnson, and On The Corner with their James Brown-like static grooves both provoked criticism from traditionalists, and provided the model for his protégés to create in an idiom that spoke to and for the younger Boomer audience. The door had been opened for the entrance of Hip-Hop.

undefined

youtube

#Miles Davis#m.c. escher#andywarhol#postmodernism#ModalJazz#George Russell#kind of blue#Jacques Derrida#mlkjr#Bitches Brew#Jazz

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jeff Parker — Suite for Max Brown (International Anthem/Nonesuch)

Photo by Jim Newberry

youtube

Following the looped, electronic and eclectic New Breed, Jeff Parker’s latest album expands into an even greater range of off-kilter sonic experiments. His previous guitar playing with groups like Tortoise and Isotope 217, as well as his own trios and other collaborations, have shared his use of indelible melody and modal harmony in the context of post-rock and jazz. Here, the combination of treated loops, layers of horns (up front) and synths (usually in the background), create an atmosphere reminiscent of the soundtrack to a fast-paced cartoon.

Though not omnipresent, Parker uses his guitar here as an added dimension when it pops up. On album opener “Build a Nest” he plays with dizzying speed for a five-second burst of distorted John McLaughlin-like soloing that comes out of nowhere near the end of the track. Around that flourish, the track is built on Dirty Projectors-ish vocal harmonies, piano, a sliding bass line and a beat that keeps breaking down into jazz chords. From there, the album proceeds to the soul horns sampling “C’mon Now”, followed by a cover of John Coltrane’s meditative “After the Rain.” Parker plays the melody with a clean electric guitar tone with tremolo, with acoustic drums and bass, and featuring an almost cheesy synth sound as well. The juxtaposition makes the track land somewhere between far out jazz fusion and the weather channel, but it works.

Synth-heavy, jazz-indebted ambiance distinguishes “Metamorphoses.” It’s a break from the more beat oriented materials of many of the songs, and it layers droney notes with synth arpeggios and ringing chimes in overlapping loops that come together and then drift apart. After that, “Gnarciss” brings an evolving orchestral hip hop melody that gradually undoes itself into an abrupt finish. Throughout, the album mixes longer tracks with shorter pieces. They get into a well-developed idea that fades or burns out quickly before they become tired.

A more straightforward vehicle for Parker’s playing is the relatively unadorned “3 for L”. On it, Parker takes the lead with only an acoustic bass/drums trio, and the depth of his playing is evident. However, even as the composition unfolds, quiet background elements of percussion in the right channel add a sense of space and foreground the constructed nature of the recording. It’s the added layers and the mix of sounds, both on the album as a whole and within each track, that give the listener new details to focus on after repeat listens. As the album unfolds, it becomes more fun to detect each added piece of a different musical tradition that Parker has successfully incorporated.

Arthur Krumins

#jeff parker#suite for max brown#international anthem#nonesuch#arthur krumins#albumreview#dusted#jazz#guitar#tortoise#isotope 217#loops

4 notes

·

View notes