#jazz mode chords

Text

Modal Chords:Modal Chordal Harmony

Modal Chords: Harmony

CLICK SUBSCRIBE!

Modal Chords: “Chords” from Transposed Mode [C as Root] Lesson/How to/Examples

Please watch video above for detailed information and examples:

Hi Guys,

Moving on from our last blog on the Modal backing track, I have included another video [above] explanation regarding the modal chords/harmony that I employed.

PDF MODAL CHORDS:

pdf-modal-chordsmodal chords Download

IF THIS…

View On WordPress

#aeolian#chord modes#chords from modes#Dorian#explained#fusion modal chord#how to#ionian#jazz mode chords#lesson#Locrian#Lydian#Mixolydian#modal chords#modal harmony#modalic chords#Phrygian#transposed modes

0 notes

Text

music theory is. just applied chord studies

#its just all chords#scales? big chords#intervals? chords of various sizes#voicings? chords but the wrong frets#modes? chords but not quite in order#progressions? chords but not quite out of order#jazz? chords but spicy#rock? chords but crunchy#i could go all day#but you get the point

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music theory notes (for science bitches) - part 2: pentatonics and friends

or, the West ain't all that.

Hello again everyone! I'm grateful for the warm reception to the first music theory notes post (aka 'what is music? from first principles'). If you haven't read it, take a look~

In that stab at a first step towards 'what is music', I tried to distinguish between what's a relatively universal mathematical structure (nearly all musical systems have the octave) and what's an arbitrary convention. But in the end I did consciously limit myself, and make a beeline for the widely used 12TET tuning system and the diatonic scales used in Western music. I wanted to avoid overwhelming myself, and... 👻 it's all around us...👻

But! But but but. This is a series on music theory. Not just one music theory. The whole damn thing. I think I'm doing a huge disservice to everyone, not least me, if that's where we stop.

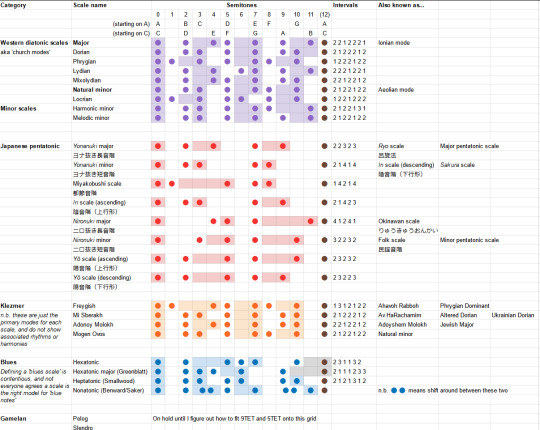

Today, then! For our second installation: 'Music theory notes (for science bitches)' will take a quick look through some examples that diverge from the diatonic scale: the erhu, Japanese pentatonic scales, gamelan, klezmer, and blues.

Also since the first part was quite abstract, we'll also having a go at using the tools we've built so far on a specific piece, the Edo-period folk song Sakura, Sakura.

Sound fun? Let's fucking gooooo

The story so far

To recap: in the first post we started by saying we're gonna be looking at tonal music, which isn't the only type of music. We introduced the idea of notes and frequencies by invoking the magic name of Fourier.

We said music can be approximated (for now) as an idealised pressure wave, which we can divide into brief windows called 'notes', and these notes are usually made of a strong sine wave at the 'fundamental frequency', plus a stack of further sine waves at integer multiples of that frequency called 'overtones'.

Then, we started constructing a culturally specific but extremely widespread system of creating structure between notes, known as '12 Tone Equal Temperament' or 12TET. The main character of this story is the interval, which is the ratio between the fundamental frequencies of two notes; we talked about how small-integer ratios of frequencies tend to be especially 'consonant' or nice-sounding.

We introduced the idea of the 'octave', which is when two notes have a frequency ratio of 2. We established the convention treating notes an octave apart as deeply related, to the point that we give them the same name. We also brought in the 'fifth', the ratio of 1.5, and talked about the idea of constructing a scale using small-integer ratios.

But we argued that if you try and build everything with those small-integer ratios you can dig yourself into a hole where moving around the musical space is rife with complications.

As a solution to this, I pulled out 'equal temperament' as an approximation with a lot of mathematical simplicity. Using a special irrational ratio called the "semitone" as a building block, we could construct the Western system of scales and modes and chords and such, where

a 'scale' is kind of like a palette for a piece of music, defined by a set of frequency ratios relative to a 'root' or 'tonic' note. this can be abstract, as in 'the major scale', or concrete, as in 'C major'.

a 'mode' is a cyclic permutation of an abstract scale. although it may contain the same notes, moving them around can change the feeling a lot!

a 'chord' is playing multiple notes at the same time. 'Triad' chords can be constructed from scales. There are other types which add or remove stuff from the triads. We'll come back to this.

I also summarised how sheet music works and the rather arbitrary choices in its construction, and at the end, I very briefly talked about chord notation.

There's a lot of ways to do this...

I recently watched a video by jazz musician and music theory youtuber Adam Neely, in which he and Philip Ewell discuss how much "music theory" is treated as synonymous with a very specific music theory which Neely glosses as "the harmonic style of 18th-century European composers". He argues, pretty convincingly imo, that 'music theory' pedagogy is seriously weakened by not taking non-white/Western models, such as Indian classical music theories, as a foil - citing Anuja Kamat's channel on Indian classical music as a great example of how to do things differently. Here's her introductory playlist on Indian classical music concepts, which I will hopefully be able to lean on in future posts:

There's two big pitfalls I wanna avoid as I teach myself music theory. I like maths a lot, and if I can fit something into a mathematical structure it's much easier for me to remember it - but I gotta be really careful not to mathwash some very arbitrary conventions and present them as more universal than they are. Music involves a lot of mathematics, but you can't reduce it to maths. It's a language for expressing emotion, not a predicate to prove.

One of the big goals of this series is to get straight in my head what has a good answer to 'why this way?', and what is just 'idk it's the convention we use'. And if something is an arbitrary convention, we gotta ask, what other conventions exist? Humans are inventive little buggers after all.

I also don't want to limit my analytical toolbox to a single 'hammer' of Western music theory, and try and force everything else into that frame. The reasons I'm learning music theory are... 1. to make my playing and singing better, and be more comfortable improvising; 2. to learn to compose stuff, which is currently a great mystery. How do they do it? I do like Western classical music, but honestly? Most of the music I enjoy is actually not Western. I want to be able to approach that music on its own terms.

For example, the erhu... for erhuample???

The instrument family I'm learning, erhu/zhonghu, is remarkably versatile - there are no frets (or even a soundboard!) to guide you, which is both a challenge and a huge freedom. You can absolutely play 12TET music on it, and it has a very beautiful sound - here is an erhu harmonising with a 12TET-tuned piano to play a song from the Princess Mononoke soundtrack, originally composed by Joe Hisaishi as an orchestral piece for the usual Western instruments...

youtube

This performance already makes heavy use of a technique called (in English) 'vibrato', where you oscillate the pitch around as you play the note (which means the whole construction that 'a note has a fixed pitch defined by a ratio' is actually an abstraction - now a note's 'frequency' represents the middle point a small range of pitches!). Vibrato is very common in Western music too, though the way you do it on an erhu and the way you do it on a violin or flute are of course a little different. (We could do an aside on Fourier analysis of vibrato here but I think that's another day's subject).

But if you listen to Chinese compositions specifically for Erhu, they take advantage of the lack of fixed pitch to zip up and down like crazy. Take the popular song Horse Racing for example, composed in the 1960s, which seems to be the closest thing to the 'iconic' erhu piece...

youtube

This can be notated in 12TET sheet music. But it's also taking full advantage of some of the unique qualities of the erhu's long string and lack of frets, like its ability to glide up and down notes, playing the full range of 'in between' frequencies on one string. The sheet music I linked there also has a notation style called 简谱 jiǎnpǔ which assigns numbers to notes. It's not so very different from Western sheet music, since it's still based on the diatonic major scale, but it's adjusted relative to the scale you're currently playing instead of always using C major. Erhu music very often includes very fast trills and a really skilled erhu/zhonghu player can jump between octaves with a level of confidence I find hard to comprehend.

I could spend this whole post putting erhu videos but let me just put one of the zhonghu specifically, which is a slightly deeper instrument; in Western terms the zhonghu (tuned to G and D) is the viola to the erhu's violin (tuned to D and A)...

youtube

To a certain degree, Chinese music is relatively easy to map across to the Western 12-tone chromatic scale. For example, the 十二律 shí'èr lǜ system uses essentially the same frequency ratios as the Pythagorean system. However, Chinese music generally makes much heavier use of pentatonic scales than Western music, and does not by default use equal temperament, instead using its own system of rational frequency ratios. correction: with the advent of Chinese orchestras in the mid-20thC, it seems that Chinese instruments now usually are tuned in equal temperament.

I would like my understanding of music theory to have a 'first class' understanding of Chinese compositions like Horse Racing (and also to have a larger reference pool lmao). I'm going to be starting formal erhu lessons next month, with a curriculum mostly focused on Chinese music. If I have interesting things to report back I'll be sure to share them!

Anyway, in a similar spirit, this post we're gonna try and do a brief survey of various musical constructs relevant to e.g. Japanese music, Klezmer, Blues, Indian classical music... I have to emphasise I am not an expert in any of these systems, so I can't promise to have the most elegant form of presentation for them, just the handles I've been able to get. I will be using Western music theory terms quite a bit still, to try and draw out the parallels and connections. But I hope it's going to be interesting all the same.

Let's start with... pentatonic scales!

Pentatonic scales

In the previous post we focused most of our attention on the diatonic scale. Confusingly, a "diatonic" scale is actually a type of heptatonic scale, meaning there are 7 notes inside an octave. As we've seen, the diatonic scale is constructed on top of the 12-semitone system.

Strictly defined, a 'diatonic' scale has five intervals of two semitones and two intervals of one semitone, and the one-semitone intervals are spread out as much as possible. So 'diatonic scales' includes the major scale and all its cyclic permutations (aka 'modes'), including the natural minor scale, but not the other two minor scales we talked about last time!

However, whoever said we should pick exactly 7 notes in the octave? That's rather arbitrary, isn't it?

After all, in illustration, a more restricted palette can often lead to a much more visually striking image. The same is perhaps even more true in music!

A pentatonic scale is, as the name suggests, a scale which has five notes in an octave. Due to all that stuff we discussed with small-number ratios, the pentatonic scales we are about to discuss can generally be mapped quite easily onto the 12-tone system. There's some reason for this - 12TET is designed to closely approximate the appealing small-number frequency ratios, so if another system uses the same frequency ratios, we can probably find a subset of 12TET that's a good match.

Of course, fitting 12TET doesn't mean it matches the diatonic scale, necessarily. Still, once you're on the 12 tone system, there's enough diatonic scales out there that you can often define a pentatonic scale in terms of a delta relative to one of the diatonic scale modes. Like, 'shift this degree down, delete that degree'.

Final caveat: I'm not sure if it's strictly correct to use equal temperament in all these examples, but all the sources I find define these scales using Western music notation, so we'll have to go with that.

Sakura, sakura and the yonanuki scale

Let's start with Japanese music. Here's the Edo-period folk song Sakura, Sakura, which is one of the most iconic pieces of Japanese music¸ especially abroad:

youtube

This uses the in scale, also known as the sakura pentatonic scale, one of a few widely used pentatonic scales in Japanese folk music, along with the yo scale, insen scale and iwato scale... according to English-language sources.

Finding the actual Japanese was a bit difficult - so far as I can tell the Japanese wiki page for Sakura, Sakura never mentions the scale named after it! - but eventually I found a page for pentatonic scales, or 五音音階 goon onkai. So we can finally determine the kanji for this scale is 陰音階 in onkai or 陰旋法 in senpou. [Amusingly, the JP wiki article on pentatonic scales actually leads with... Scottish folk songs and gamelan before it goes into Japanese music.]

However, perhaps more pertinent is this page: ヨナ抜き音階 which introduces the terms yonanuki onkai and ニロ抜き音階 nironuki onkai. This can be glossed as 'leave out the fourth (yo) and seventh (na) scale' and 'leave out the second (ni) and sixth (ro) scale', describing two procedures to construct pentatonic scales from a diatonic scale.

Let's recap major and minor. Last time we defined them using semitone intervals from a root note (the one in brackets is the next octave):

position: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, (8)

major: 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, (12)

minor: 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, (12)

From here we can construct some pentatonic scales. Firstly, here are your yonanuki scales - the ones that delete the fourth and seventh:

major: 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, (12)

minor: 0, 2, 3, 7, 8, (12)

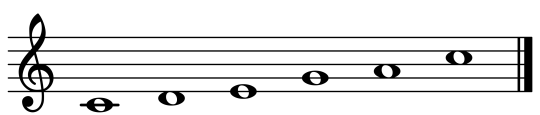

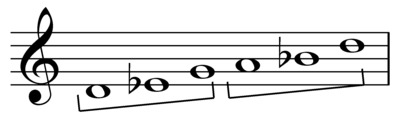

Starting on C for the major and A for the minor (the ones with the blank key signature), this is how you notate that in Western sheet music. As you can see, we have just deleted a couple of steps.

The first one is the 'standard' major pentatonic scale in Western music theory; it's also called the ryo scale in traditional Japanese music (呂旋法 ryosenpou). The second one is a mode (cyclic permutation) of a scale called 都節音階 miyakobushi, which is apparently equivalent to the in scale.

In terms of gaps between successive notes, these go:

major: 2, 2, 3, 2, 3 - very even

minor: 2, 1, 4, 1, 4 - whoah, huge intervals!

The miyakobushi scale, for comparison, goes...

miyakobushi (absolute): 0, 1, 5, 7, 8, (12)

miyakobushi (deltas): 1, 4, 2, 1, 4

JP wikipedia lists two different versions of the 陰旋法 (in scale), for ascending and descending. Starting on C, one goes C, D, Eb, G, A; the other goes C, D, Eb, G, Ab. Let's convert that into my preferred semitone interval notation:

in scale (absolute, asc): 0, 2, 3, 7, 9, (12)

in scale (relative, asc): 2, 1, 4, 2, 3

in scale (absolute, desc): 0, 2, 3, 7, 8, (12)

in scale (relative, desc): 2, 1, 4, 1, 4

So we see that the 'descending form' of the in scale matches the minor yonanuki scale, and it's a mode (cyclic permutation) of the miyakobushi scale.

We've talked a great deal about the names and construction of the different type of scales, but beyond the vague gesture to the standard associations of 'major upbeat, minor sad/mysterious' I don't think we've really looked at how a scale actually affects a piece of music.

So let's have a look at the semitone intervals in Sakura, Sakura in absolute terms from to the first note...

sakura, sakura, ya yoi no so ra-a wa

0, 0, 2; 0, 0, 2; 0, 2, 3, 2, 0, 2-0, -4

and in relative terms between successive notes:

sa ku ra, sa ku ra, ya yo i no so ra-a wa

0, 0, +2; -2, 0, +2; -2, +2, +1, -1, -2, +2, -2, -4

If you listen to Sakura, Sakura, pay attention to the end of the first line - that wa suddenly drops down a huge distance (a major second - for some reason I miscalculated this and thought it was a tritone) and that's where it feels like damn, OK, this song is really cooking! It catches you by surprise. We can identify these intervals as belonging to the in/yoyanuki minor scale, and even starting on its root note.

Although its subject matter is actually pretty positive (hey, check it out guys, the cherry blossoms are falling!), Sakura, Sakura sounds mournful and mysterious. What makes it sound 'minor'? The first phrase doesn't actually tell you what key we're in, that jump of 2 semitones could happen in major or minor. But the second phrase, introduces the pattern of going up 2, then up 1, from the root note - that's the minor scale pattern. What takes it beyond just 'we're in minor'? That surprise tritone move down. According to the rough working model that 'dissonant notes create tension, consonant notes resolve it', this creates a ton of tension. This analysis is bunk, there isn't a tritone. It's a big jump but it's not that big a jump.

How does it eventually wrap up? The final phrase of Sakura, Sakura goes...

i za ya, i za ya, mi ni yu - u ka nn

0, 0, 2; 0, 0, 2; -5, -4, 2, 0, -4, -5

0, 0, +2; -2, 0, +2; -5, +1, +4, -2, -4, -1

Here's my attempt to try and do a very basic tonal/interval analysis. We start out this phrase with the same notes as the opening bars, but abruptly diverge in bar 3, slowing down at the same time, which provides a hint that things are about to come to a close. The move of -5 down is a perfect fourth; in contrast to the tritone major second we had before, this is considered a very consonant interval. (A perfect fourth down is also equivalent to going up a fifth and then down an octave. So we're 'ending on the fifth'.) We move up a little and down insteps of 4, 2, and 1, which are less dramatic. Then we come back down and end on the fifth. We still have those 4-steps next to 1 steps which is the big flag that says 'whoah we're in the sakura pentatonic scale', but we're bleeding off some of the tension here.

Linguistically, the song also ends on the mora ん, the only mora that is only a consonant (rather than a vowel or consonant-vowel), and that long drawn-out voiced consonant gives a feeling of gradually trailing away. So you could call it a very 'soft' ending.

Is this 'tension + resolution' model how a Japanese music theorist would analyse this song? It seems to be a reasonably effective model when applied to Japanese music by... various music theorist youtubers, but I don't really know! That's something I want to find out more about.

Something raised on the English wiki is the idea that the miyakobushi scale is divided into two groups, spanning a fourth each, which is apparently summarised by someone called Koizumi Fumio in a book written in 1974:

Each group goes up 1 (a semitone or minor second), then 4 (major third), for a total of 5 (perfect fourth). The edges of these little blocks are considered 'nucleus' notes, and they're of special importance.

Can we see this in action if we look at Sakura, Sakura? ...ehhhh. I admit, the way I think of the song is shaped by the way I play it on the zhonghu; I think of the first two two-bar phrases as the 'upper part' and the third phrase as the 'lower part', and neither lines up neatly with these little groups. Still. I suspect Koizumi Fumio, author of Nihon no ongaku, knows a little more about this than I do, so I figure it's worth a mention.

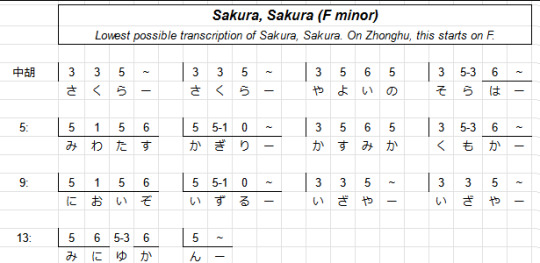

Aside: on absorbing a song

Sakura, Sakura is kinda special to me because it's like the second piece I learned to play on zhonghu (after Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star lmao). I can't play it well, but I am proud that I have learned to play it at least recognisably.

The process of learning to play it involved writing out tabs and trying out different ways of moving my hand. I transcribed Sakura Sakura down to start on F, since that way the open G string of the zhonghu could be the lowest note of the piece, and worked out a tab for it using a tab system I cooked up with my friend. Here's what it looks like. The system counts semitones up from the open string, and it uses an underline to mark the lower string.

(Also, credit where it's due - I would never have made any progress learning about music if not for my friend Maki Yamazaki, a prodigiously multitalented self-taught musician who can play dozens of instruments, and also the person who sold me her old zhonghu for dirt cheap, if you're wondering why a white British girl might be learning such an unusual instrument. You can and should check our her music here! Maki has done more than absolutely anyone to make music comprehensible to me, and a lot of this post is inspired by discussing the previous post with her.)

When you want to make a song playable on an instrument, you have to perform some interpretation. Which fingers should play which notes? When should you move your hand? How do you make sure you hit the right notes? At some point this kind of movement becomes second nature, but I'm at the stage, just like a player encountering a new genre of videogame, where I still don't have the muscle memory or habituation to how things work, and each of these little details has to be worked out one by one. But this is great, because this process makes me way more intimately familiar with the contours of the song. Trying to analyse the moves it makes like the above even more so.

More Japanese scales

So, to sum up what we've observed, the beautiful minor sounds of Sakura Sakura come from a pentatonic scale which can be constructed by taking the diatonic scale and blasting certain notes into the sea, namely the fourth and the seventh of the scale. But what about the nironuki scale? Well, this time we delete the second and the sixth. So we get, in absolute terms:

major nironuki (abs): 0, 4, 5, 7, 11, (12)

major nironuki (rel): 4, 1, 2, 4, 1

minor nironuki (abs): 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, (12)

minor nironuki (rel): 3, 2, 2, 3, 2

Hold on a minute, doesn't that look rather familiar? The major nironuki scale is a permutation, though not a cyclic permutation, of the minor yonanuki scale. And the minor nironuki scale is a cyclic permutation (mode) of the major one.

Nevertheless, these scales have names and significance of their own. The major one is known as the 琉球音階 ryūkyū onkai or Okinawan scale. The minor one is what Western music would call a 'minor pentatonic scale'. It also mentions a couple of other names for it, like the 民謡音階 minyou onkai (folk scale).

We also have the yō scale, which like the in scale, comes in ascending and descending forms. You want these too? Yeah? Ok, here we go.

yō scale (asc, abs): 0, 2, 5, 7, 10, (12)

yō scale (asc, rel): 2, 3, 2, 3, 2

yō scale (desc, abs): 0, 2, 5, 7, 9, (12)

yō scale (desc, rel): 2, 3, 2, 2, 3

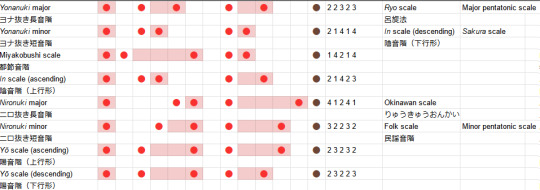

The yō scale is what's called an anhemitonic pentatonic scale, which is just a fancy way of saying it doesn't have semitones. (The in scale in turn is hemitonic). The ascending form is also called the 律戦法 ritsusenpou. Here's the complete table of all the variants I've found so far.

So, in summary: Japanese music uses a lot of pentatonic scales. (In a future post we can hopefully see how that applies in modern Japanese music). These pentatonic scales can be constructed by deleting two notes from the diatonic scales. In general, you land in one of two zones: the anhemitonic side, where all the intervals between successive notes, are 2 and 3, and the hemitonic side, where the intervals are spicier 1s and 4s and a lone 2. From there, you can move between other pentatonic scales by cyclic permutations and reversal.

If you analyse Japanese music from a Western lens, you might well end up interpreting it according to one of the modes of the major scale. In fact, the 8-bit music theory video I posted last time takes this approach. This isn't wrong per se, it's a viable way to getting insight into how the tune works if you want to ask the question 'how does this conjure emotions and how do I get the same effects', but it's worthwhile to know what analytical frame the composers are likely to be using.

Gamelan - when 12TET won't cut it

Gamelan is a form of Indonesian ensemble music. I do not at this time know a ton about it, but here's a performance:

youtube

However, if you're reading my blog then it's likely that if know gamelan from anywhere, it's most likely the soundtrack to Akira composed by Shōji Yamashiro.

youtube

This blends traditional gamelan instrumentation and voices with modern synths to create an incredibly bold and (for most viewers outside Indonesia!) unfamiliar sound to accompany the film's themes of psychic awakening and evolution. It was an inspired choice, adding a lot to an already great film.

'A gamelan' is the ensemble; 'gamelan' is also the style of music. There are many different types of gamelan associated with different occasions - some gamelans are only allowed to form for special ceremonies. Gamelan is also used as a soundtrack in accompaniment to other art forms, such as wayang kulit and wayang wong (respectively, shadow puppetry and dance).

Since gamelan music evidently uses quite a bit of percussion, and so far we've been focused on the type of music played on strings and wind instruments - a brief comment on the limitations of our abstractions. Many types of drums don't fit the 'tonal music' frame we've outlined so far, creating a broad frequency spectrum that's close to an enveloped burst of white noise rather than a sharply peaked fundamental + overtones. There's a ton to study in drumming, and if this series continues you bet I'll try to understand it.

But there are tonal percussion instruments, and a lot of them are to be found in gamelan, particularly in the metalophone family (e.g. the ugal or jegogan). The Western 'xylophone' and 'glockenspiel' also belong to this family. Besides metalophones, you've got bells, steel drums, tuning forks etc. Tuning a percussion instrument is a matter of adjusting the shape of the metal to adjust the resonant frequency of its normal modes. I imagine it's really fiddly.

In any case, the profile of a percussion note is quite different from the continual impulse provided by e.g. a violin bow. You get a big burst across all frequencies and then everything but the resonant mode dies out, leaving the ringing with a much simpler spectrum.

Anyway, let's get on to scales and shit. While I have the Japanese wikipedia page on pentatonic scales open, that it mentions a gamelan scale called pelog (written ᮕᮦᮜᮧᮌ᮪, ꦥꦺꦭꦺꦴꦒ꧀ or ᬧᬾᬮᭀᬕ᭄ in different languages) meaning 'beautiful'. Pelog is not strictly one scale, but a family of tunings which vary across Indonesia. Depending on who you ask, it might in some cases be reasonably close to a 9-tone equal temperament (9TET), which means a number of notes can't be represented in 12TET - you have that 4 12TET semitones would be equivalent to 3 9TET semitones. From this is drawn a heptatonic scale, but not one that can be mapped exactly to any 12TET heptatonic scale. Isn't that fun!

To represent scales that don't exactly fit the tuning of 12TET, there's a logarithmic unit of measure called the 'cent'. Each 12TET semitone contains 100 cents, so in terms of ratios, a cent is the the 1200th root of 2. In this system, a 9TET semitone is 133 cents. Some steps in the pelog heptatonic scale would then be two 9TET semitones, and others one 9TET semitone. However, this system of 'semitones' does not seem to be how gamelan music is actually notated - it's assumed you already have an established pelog tuning and can play within that. So it's a little difficult for me to give you a decent representation of a gamelan scale that isn't approximated by 12TET.

From the 7-tone pelog scale, whatever it happens to be where you live, you can further derive pentatonic scales. These have various names, like the pelog selisir used in the gamelan gong kebyar. I'm not going to itemise them here both because I haven't actually been able to find the basic pelog tunings (at least by their 9TET approximation).

Another scale used in gamelan is called slendro, a five tone scale of 'very roughly' equal intervals. Five is coprime with 12, so there's no straightforward mapping of any part of this scale to the 12-tone system. But more than that, fully even scales are quite rare in the places we've looked so far. (Though apparently within slendro, you can play a note that's deliberately 'out of place', called 'miring'. This transforms the mood from 'light, cheerful and busy' to one appropriate to scenes of 'homesickness, love missing, sadness, death, languishing'.)

The Western musical notation system is plainly unsuited for gamelan, and naturally it has its own system - or rather several systems. In one method, the seven tones of the pelog are numbered 1 through 7, and a subset of those numbers are used to enumerate slendro tuning. You can write it on a grid similar to a musical staff.

But we could wonder with this research - is the attempt to map pélog to 'equal temperament' an external imposition? Presented with a tuning system with seven intervals that are not consistently equal temperament, averaging them to construct an equal temperament hypothesis on that basis, and finally attempting to prove that gamelan players 'prefer' equal temperament... well, they do at least bother to ask, but I'm not entirely convinced that 9TET or 5TET is the right model. Unfortunately, most of the literature I'm able to find on gamelan music theory with a cursory search is by Western researchers.

There's a fairly long history of Western composers taking inspiration from gamelan, notably Debussy and Saty. And of course, modern Indonesian composers such as I Nyoman Windha have also been finding ways to combine gamelan with Western styles. Here's a piece composed by him (unfortunately not a splendid recording):

youtube

Klezmer - layer 'em up

If you've known me for long enough you might remember the time I had a huge Daniel Kahn and the Painted Bird phase. (I still think he's great, I just did that thing where I obsessively listen to one small set of things for a period). And I'd also listen to old revolutionary songs in Yiddish all the time. Because of course I did lmao. Anyway, here's a song that combines both: Kahn's modern arrangement of Arbetlose Marsch in English and Yiddish:

youtube

That's a style of music called klezmer, developed by Ashkenazi Jews in Central/Eastern Europe starting in the late 1500s and 1600s. It's a blend of a whole bunch of different traditions, combining elements from Jewish religious music with other neighbouring folk music traditions and European music at large. When things really kicked off at the end of the 19th century, klezmer musicians were often a part of the Jewish socialist movement (and came up with some real bangers - the Tsar may have been shot by the Bolsheviks but tbh, Daloy Politsey already killed him). But equally there's a reason it sounds insanely danceable: it was very often used for dances.

The rest of the 20th century happened, but klezmer survived all the genocides and there are lots of different modern klezmer bands.

The defining characteristics of klezmer per Wikipedia are... ok, this is quite long...

Klezmer musicians apply the overall style to available specific techniques on each melodic instrument. They incorporate and elaborate the vocal melodies of Jewish religious practice, including khazones, davenen, and paraliturgical song, extending the range of human voice into the musical expression possible on instruments.[21] Among those stylistic elements that are considered typically "Jewish" in Klezmer music are those which are shared with cantorial or Hasidic vocal ornaments, including dreydlekh ("tear in the voice"; plural of dreidel)[22][23] and imitations of sighing or laughing ("laughter through tears").[24] Various Yiddish terms were used for these vocal-like ornaments such as קרעכץ (Krekhts, "groan" or "moan"), קנײטש (kneytsh, "wrinkle" or "fold"), and קװעטש (kvetsh, "pressure" or "stress").[10] Other ornaments such as trills, grace notes, appoggiaturas, glitshn (glissandos), tshoks (a kind of bent notes of cackle-like sound), flageolets (string harmonics),[22][25]pedal notes, mordents, slides and typical Klezmer cadences are also important to the style.[18]

So evidently klezmer will be relevant throughout this series, but for now, since we're trying to flesh out the picture of 'how is tuning formed', let's take a look at the notes.

So it's absolutely possible to fit klezmer into the 12TET system. But we're going to need to crack open a few new scales. Though the Wikipedia editors enumerating this list caution us: "Another problem in listing these terms as simple eight-note (octatonic) scales is that it makes it harder to see how Klezmer melodic structures can work as five-note pentachords, how parts of different modes typically interact, and what the cultural significance of a given mode might be in a traditional Klezmer context."

With that caution in mind, let's at least see what we're given. First of all we have the Freygish or Ahavoh Rabboh scale, one of the most common pieces, good friend of the Western phrygian but with an extra semitone. Then there's Mi Sbererakh or Av HaRachamim which is a mode of it, that's popular around Ukraine. Adonoy Molokh or Adoyshem Molokh is the major scale but you drop the seventh a semitone. Mogen Ovos is the same as the natural minor at least on the interval level.

Which means, without the jargon, here are the semitones (wow wouldn't it be nice if you had tables on here?):

position: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, (8)

freygish: 0, 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, (12)

deltas: 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2

mi sberakh: 0, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, (12)

deltas: 2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 1, 2

adonoy m.: 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, (12)

deltas: 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2

mogen o.: 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, (12)

deltas: 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2

...that's a big block of numbers to make your eyes glaze over huh. Maybe this 'convert everything to semitone deltas' thing isn't all it's cracked up to be... or maybe what I need to do is actually visualise it somehow? Some kinda big old graph showing all the different scales we've worked out so far and how they relate to each other? ...hold your horses...

[It seems like what I've done is reinvent something called 'musical set theory', incidentally.]

OK, having enumerated these, let's return to the Wikipedian's caution. What is a pentachord? Pretty simple, it's a chord of five notes. Mind you, some people define it as five successive notes of a diatonic scale.

In klezmer, you've got a bunch of different instruments playing at once creating a really dense sound texture. Presumably one of the things you do when you play klezmer is try and get the different instruments in your ensemble to hit the different levels of that pentachord. How does that work? Well, if we consult the sources, we find this scan of a half-handwritten PDF presenting considerably more detail on the modes and how they're played. The scales above are combined with a 'motivic scheme' presenting different patterns that notes tend to follow, and a 'typical cadence'. Moreover, these modes can have 'sub-modes' which tend to follow when the main mode gets established.

To me reading this, I can kind of imagine the process of composing/improvisation within this system almost like a state machine. It's not just that you have a scale, you have a certain state you're in in the music (e.g. main mode or sub-mode), and a set of transitional moves you can potentially make for the next segment. That's probably too rigid a model though. There's also a more specific aspect discussed in the book that a klezmer musician needs to know how to move between their repertoire of klezmer pieces - what pieces can sensibly follow from what.

Ultimately, I don't want to give you a long list of stuff to memorise. (Sure, if you want to play klezmer, you probably need to get familiar with how to use these modes, but that's between you and your klezmer group). Rather I want to make sure we don't have any illusion that the Western church modes are the only correct way to compose music.

Blues - can anyone agree?

Blues is a style of music developed by Black musicians in the American south in the late 1800s, directly or indirectly massively influential on just about every genre to follow, but especially jazz. It's got a very characteristic style defined by among other elements use of 'blue notes' that don't fit the standard diatonic scale. According to various theorists, you can add the blue notes to a scale to construct something called the 'blues scale'. According to certain other theorists, this exercise is futile, and Blues techniques can't be reduced to a scale.

So for the last part of today's whirlwind tour of scales, let's take a brief look at the blues...

There are a few different blues scales. The most popular definition seems to be a hexatonic scale. We'll start with the minor pentatonic scale, or in Japanese, the minor nironuki scale - which is to say we take the minor diatonic scale and delete positions 2 and 6. That gives:

minor nironuki (abs): 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, (12)

minor nironuki (rel): 3, 2, 2, 3, 2

Now we need to add a new note, the 'flat fifth degree' of the original scale. In other words, 6 semitones above the root - the dreaded tritone!

hexatonic blues (abs): 0, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, (12)

hexatonic blues (rel): 3, 2, 1, 1, 3, 2

Easy enough right? Listen to that, it does sound kinda blues-y. But hold your horses! Moments after defining this scale, we read...

A major feature of the blues scale is the use of blue notes—notes that are played or sung microtonally, at a slightly higher or lower pitch than standard.[5] However, since blue notes are considered alternative inflections, a blues scale may be considered to not fit the traditional definition of a scale.

So, if you want to play blues, it's not enough to mechanically play a specific scale in 12TET. You also gotta break the palette a little bit.

There's also a 'major blues' heptatonic scale which goes 0, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, according to one guy called Dan Greenblatt.

But that's not the only attempt to enumerate the 'blues scale'. Other authors will give you slightly longer scales. For example, if you ask Smallwood:

heptatonic blues (abs): 0, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, (12)

heptatonic blues (rel): 2, 1, 2, 1, 3, 1, 2

which isn't quite a mode of any of those klezmer scales we saw previously, but nearly!

If you ask Benward and Saker, meanwhile, a Blues scale could actually be nonatonic scale, where you add flattened versions of a couple of notes to the major scale.

nonatonic blues (abs): 0, 2, 3/4, 5, 7, 9, 10/11, (12)

There's also an idea that you should play notes in between the semitones, i.e. quarter tones, which would be a freq ratio of the 24th root of 2 if you're keeping score at home.

The upshot of all this is probably that going too far formalise the blues is probably not in the spirit of the blues, but if you want to go in a blues-y direction it will probably mean insert an extra, flattened version of a note to one of your scales. Muck around and see what works, I guess!

Of course, there's a lot more to Blues than just tweaking a scale. For example, 'twelve bar blues' is a specific formalised chord progression that is especially universal in Jazz. What it means for chords to 'progress' is a whole subject, and I think that's the next thing I'll try to understand for post 3. Hopefully we'll be furnished with a slightly broader model of how music works as we go there though.

To wrap up, here's the spreadsheet showing all the 12TET scales encountered so far in this series in a visual way. There's obviously plenty more out there, but this is not ultimately a series about scales. It's all well and good to have a list of what exists, but it's pointless if we don't know how to use it.

Phew

Mind you even with all this, we haven't covered at all some of the most complex systems of tonal music - I've only made the vaguest gesture towards Indian classical music, Chinese music, Jazz... That's way beyond me at the moment. But maybe not forever.

Next up: I'm going to try and finally wrap my head around chords and make sense of what it means for them to 'progress', have 'movement' etc. And maybe render a bit more concrete the vague stuff I said about 'tension' and 'resolution'.

(Also: I definitely know I have friends on here who are very widely knowledgeable about music theory. If I've made any major mistakes, please let me know! At some point I hope to republish this series with nicer formatting on canmom.art, and it would be great to fix the bugs by then!)

#Youtube#music theory#music notes#music#notes#japanese music#gamelan#chinese music#klezmer#blues#i took my new adhd meds and hyperfocused on this all day instead of working ><

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

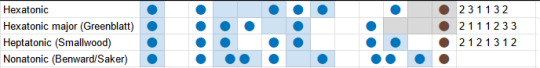

Jimmy Page pictured in the mid-'60s, around the time he took lessons from John who taught him about harmony and guitar chops in general. John and Jimmy originally met at London's Selmer music shop and became friends. As Jimmy would later explain :

"Well, I did meet John McLaughlin, who was working in there. He came down from Doncaster, and he was living in London. He was sort of introducing himself on to the Jazz scene and welcomed with open arms, as you can imagine. He was instinctively the best, I could tell. I didn’t listen to a lot of Jazz - or it was selective, what I listened to - but I could tell from what I knew that he was easily the best that I was gonna hear or witness in front of me. He was the best one I was going to see, that’s for sure. He was working there, really, to practice all week, because the only day that was busy was Saturday. That’s what he said. Fantastic! This bloke knows what he’s doing and he knows where he’s going.

I would say he was the best jazz guitarist in England then, in the traditional mode of Johnny Smith and Tal Farlow. He certainly taught me a lot about chord progressions and things like that. He was so fluent and so far ahead, way out there, and I learned a hell of a lot."

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

did punk ruin music

The short answer is "no." The longer answer is, "I'm not sure anything can 'ruin' music."

But the serious answer is that while I'm not remotely qualified to answer this question, it's been asked, so I'll give it a go. If you're serious about asking it, I'd love to know exactly what you mean.

Because my understanding is that punk was a natural and, in a sense, necessary reaction to what was going on at the time. Punk is a lot of things, but one essential thing to remember is that it's both a rejection of what was going on at the time and an embrace of prior modes of rock and roll. It's a rebellion, but it's not a wholesale rejection of everything that came before. In that sense, it has a lot in common with, say, early Beatles (and there are several examples of punk bands being influenced by the bugs, down to The Ramones' name). It is a reaction against the mainstreaming, popification of music in the 70s, a desire to get back to the basics. And you can love a lot of the excessive 70s arena and prog rock and still think we needed someone to come along and remind us that, hey, you can start a band in your garage. You don't need all that.

It's just a cycle, really. You see it again in the early 90s with grunge as a response to hair metal and power pop. You saw it in the 50s when Chuck Berry et al exploded the norms of crooners and jazz standards. Nothing's wrong with any of that, but it's refreshing for someone to put together three chords and make a beautiful noise. It's a reminder that music is for everyone.

I currently feel terribly pretentious for having said all that, but I hope it's interesting!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idk, I think what jazz had taught me is to accept things that are normally considered irregular, like harmony or chords or modes, I remember Bill Bruford (primarily a prog musician, of course) said something about people fear jazz bc of its boundlessness, it was very true. To experience things that aren't my usual comfortable zones and challenge my old knowledge can expand my ability to think in an unorthodox way.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Website : https://www.mtncitymusic.com

Address : California, USA

Mountain City Music Company specializes in providing high-quality, affordable music lessons in the comfort of your home. They offer a range of lessons including guitar, piano, and voice, tailored to individual preferences and learning styles. Their curriculum is designed around music you love, taught by knowledgeable and virtuosic instructors. The company emphasizes convenience, quality, and affordability, aiming to make music accessible and enjoyable for everyone.

Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100089682703968

Instagram : https://www.instagram.com/mountain_city_music

Keywords:

home music lessons

affordable guitar lessons

piano instruction, voice training

personalized music plan

quality music instructors

convenient music education

diverse music genres

music production lessons

beginner guitar courses

intermediate piano classes

advanced vocal training

music lesson scheduling

one-on-one music coaching

music curriculum design

in-home music teaching

music learning flexibility

music genre exploration

music teacher expertise

comprehensive music education

music lesson affordability

tailored music instruction

music practice guidance

music learning resources

music performance skills

music theory understanding

music creativity development

music lesson accessibility

music learning enjoyment

music skill enhancement

piano instruction

private music lessons

private music lessons near me

music production lessons

in home music lessons

piano instruction near me

understanding music theory

music production lessons near me

beginner online guitar course

electric guitar beginner course

private music lessons cost

average cost of private music lessons

piano instructions for beginners

guitar course for beginners

music lessons at home

casio piano instructions

electronic music production lessons

music production lessons online

music coaching

best guitar course for beginners

online private music lessons

teaching private music lessons

best online piano instruction

best piano instruction

classical piano instruction

easy piano instructions

jazz piano instruction

understanding basic music theory

understanding chords music theory

understanding guitar music theory

understanding intervals music theory

understanding modes music theory

understanding music theory guitar

private music production lessons

music performance skills

music coaching classes near me

music coaching near me

online music coaching

home music lessons near me

music lessons at your home

music lessons in your home

teaching music lessons from home

best beginner guitar course

best online guitar course for beginners

electric guitar course for beginners

affordable guitar lessons

affordable guitar lessons near me

easy to understand music theory

understanding music theory for beginners

understanding music theory for piano

understanding music theory in one hour

elite music coaching

live performance coaching music

complete guitar course for beginners

advanced vocal training

basic understanding of music theory

best music production lessons

creative music production online lessons

music and performance skills

skills for performance music

learn to enjoy classical music

learning to enjoy classical music

genre exploration music class

classical piano classes for intermediate students

at home music lessons for kids

home school music lessons

online guitar lessons affordable

#home music lessons#affordable guitar lessons#piano instruction#voice training#personalized music plan#quality music instructors#convenient music education#music production lessons#beginner guitar courses#intermediate piano classes#advanced vocal training#music lesson scheduling#music curriculum design#music learning flexibility#music genre exploration#music lesson affordability#tailored music instruction#music practice guidance

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

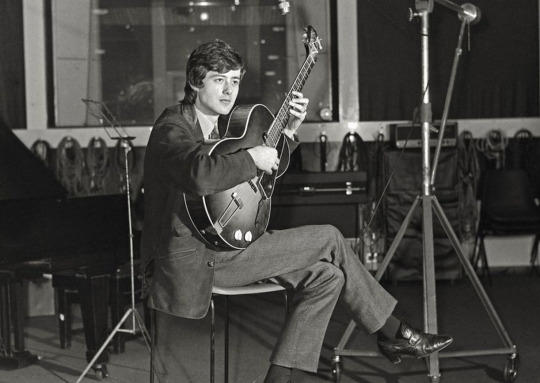

Milestones - Miles Davis (1958 Review)

One of the three Miles Davis albums I have heard, we'll get to another one of those albums much later, Milestones was a transitional album for Davis in 1958. It was still showing him in his Bebop and Hard Bop phase, but he was also showing hints of his newfound knowledge of "modal jazz", where you Improvise not over chord changes, but modes. Davis would perfect this album on his seminal album Kind of Blue a year later, but since that's not part of the "10s" Revisited series it's gonna be a while before I review that album. Though the one time I did hear the album back in 2021, it has a really good stereo mix for 1959. Anyways, the album case in point.

We start off with the opening track. Dr. Jackle, which I thought was just fairly average fast bebop. A rare moment other than the 1984 New Edition self-titled where I though that the opening track was the weakest on the whole album. But back to the song, all I can say about this song is that the double bass, played by Paul Chambers, sounds like the strings are being bowed rather than fingerpicked when played really fast. Much like on Sonny Rollins' Saxophone Colossus, the second track is a complete contrast from the previous in terms of speed, this case being the song Sid's Ahead. This is the longest song on the album at 13 minutes. Because it's at a slower speed, the improvisation is much more noticeably melodic, and I like how much minimalism the backbeat of the bass and drums are backing the horn solos before the piano, played by Red Garland, joins in during the second half of the song. The speed picks back up with track 3, Two Bass Hits, for some reason I can see the melodic intro and outro of this song somewhat fitting as background music in the scene of an 90s or very early 2000s anime. Unlike Dr. Jackle I actually enjoyed the Improvisation here a lot more, It's not as in your face and all over the place, but there are some melodic elements still there. Not a bad song for the side one closer.

Side 2 is the golden run of this album, back to back home runs. It starts off with the albums title track, Milestones(originally called Miles). What I said about the background music in an anime applies here a lot more. This song is also one of the earliest noticeable hints showing Davis's experimentation with Model Jazz that he would later perfect on albums like Kind of Blue a year later. Moving from between G Dorian or A Aoliean. The next song, Billy Boy, is a beautiful sounding song with Red Gardland fronting in the song. Just a piano, bass and drums, no horns. The album closes with Straight No Chaser, another long song at almost 11 minutes long, which is also my favorite "long song" on this album. With each member giving time to improvise in their solos, everyone sounds remarkable.

The only other similarity this album has to Saxophone Colossus, is that both albums are exactly 9 out of 10s

Listen to the album here

#music#music review#album review#album#music album#jazz#miles davis#modal jazz#1958#bebop jazz#50s jazz

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm just a rando on the internet whose opinion doesn't really matter, but I have to say, I absolutely hate these types of videos

I did actually watch the video* (it seemed to mostly be an advertisement for a book, but ignoring that), it's premise was: "these songs contain all the notes in a certain key but don't really play the tonic chord of said key, which means it never visits the tonic chord!" which I find utterly maddening.

This is such a common trend among music theorists analyzing modern pop music ("modern" in this case meaning pretty much everything released in the last five decades that's not jazz). So many of them are willing to ignore how a song sounds and treats the harmonies and melodies inside it if it means they can analyze it inside this strict, 14th century western framework**. And, if the 14th century doesn't work, they just jump up one.

"Okay, okay, so the 14th century framework didn't work... what about the 15th? That didn't either? Whew. Well, guess we're pulling out all the stops today: 16th century, here we go."

The problem isn't the specific century's framework you're using, the problem is that you refuse to interact with this music on it's own terms. (The most frustrating part is that this isn't impossible! I know that there are music theorist who do interact with this music on it's own terms, and I find their work fascinating because it at least attempts to explain what's actually happening here.) Stop focusing on the collection of notes the music uses so much and start focusing on the how and why's!***

*You should also give it a watch. Since I disagreed with the basic premise, I might be being a tad uncharitable here.

**They also do mention modes in the final, like, 30 seconds of the video before rehashing the advertisement. But, even then, that is only a slightly more satisfactory answer for why these songs work they way they do.

***It's also possible to exist in two keys at once, which is something that a lot of pop music does that many theorists just... ignore. Purposefully obfuscating the tonic of a song is seriously a staple of so many genres of "modern" pop music. This is an aside, but I did want to mention another possible reason.

#music theory#music#ceris rambles#god I find it so annoying#especially when they get so high and mighty with it#“uh actually I like to listen to music with more than four chords in it”#stfu#even if modern pop music used more than a four chord loop (which many songs do)#you'd still be an annoying fuck about it#you're completely uninterested in the actual music and far more interesting in being superior to others

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baltic Week Day 4: VIRAL MIND - Affair

Every month we choose a specific country or region to focus on, to broaden our scope of musical reviewing. For this month we have chosen the Baltic region. Alfred C. Key IV presents Latvia's VIRAL MIND and their new release, Affair.

Jazz is an American art form that incorporates many different styles of music from its onset. Viral Mind continues this tradition by incorporating rock and roll and jazz fusion into a sound that is sublime. As the music moves through modes that break the traditional format of improvising over a chord change or melody, it takes the listener on a journey of endless beauty. In this article, I will try to explore what makes this band different from all the others and worthy of jazz.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jazz Fusion Chords:How to create them from scales

CLICK SUBSCRIBE!

Hi Guys,

Today, a look at how to create colourful and interesting jazz/fusion chords:

Because, we are dealing with jazz/fusion we will manipulate a scale in modal form. This will be C Mixolydian:

Now, let’s add one note above each note of the mode and create 3rds. [Here we can hear the mode in double stops].

Now, we will add another note a 5th above the root and create…

View On WordPress

#chord creation#chord scales#chord sequences#chords#creating chords#dorian chords#Download#Examples#explained#flat 5ths#free pdf#fusion#fusion guitar#guitar#guitar chord scale#harmony jazz#how to#jazz#jazz fusion#jazz guitar#jazz modes#lesson#Major 3rds#melodic minor#mixolydian chords#modal chords#music#music notation#music tab#quartal harmony

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

In this ”Jam of the Month” I play in aeolian mode to the Dm7 chord. It's in jazz fusion style and I start to soloing and after about two minutes there's a backing track in the video and I´ll give tips on scales in the text to the back track.

More "Jam of the month" videos from link below.

► https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLv8sff7MRKt_QExNvEyRRVnk809aHmWY0

------------------------

There are transcribed lines from my solo in the video. These guitar lines, a pdf article, scale/chord tabs and an extended mp3 back track are available from the links below.

Members area website. Sign up here.

► https://www.thomasberglundguitarlessons.com/forum-1/members-signup.html

Patreon page

► https://www.patreon.com/thomasberglund

Web store (Pdf files - Jam of the month):

► https://www.thomasberglundguitarlessons.com/store/pdf-files---store-1/jam-of-the-month-pdf---store.html

Backing track available here (Modal grooves 2-9):

► https://www.thomasberglundguitarlessons.com/store/teebeebackingtracks---store-1/modal-grooves-2---store.html

My guitar lessons website:

► https://www.thomasberglundguitarlessons.com/home/index.html

Get two free e-Books with 15 Jazz guitar licks & 15 Fusion guitar licks here.

► https://www.thomasberglundguitarlessons.com/forum-1/free-e-books.html

Jazz on and feel free to share, like & subscribe!

#youtube#fusion guitar#fusionmusic#jazz fusion guitar#jazz fusion#guitar#guitar lesson#guitar lick#guitar solo#jam track#backing track#jam

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“

Recently, I had a perfect opportunity to revisit some of this work for the “Theorizing African American Music” conference in Cleveland. Through preparing to adapt my writing for this particular conference, I moved away from thinking about jazz pedagogy in higher education generally, and toward a more specific focus on “chord-scale” theory, the still dominant mode around which mainstream jazz curricula are structured. To claim that chord-scale theory is dominant is to say two things: first, that a specific type of theorizing overdetermines current jazz pedagogy, to the exclusion of other, more socially-engaged orientationstoward the theoretical. Second, that theorizing in and of itself dominates how we approach teaching jazz, to the exclusion of other modes of inquiry such as historicizing or composing. We stuff HE curricula with courses on transcription, analysis, and other music-theoretically oriented approaches. But the critical socio-historical context necessary for situating and understanding the music we’re trying so hard to learn how to produce is consistently de-emphasized.

Both the over-focus on chord scale theory as well as chord-scale theory itself are problems for equitable jazz pedagogy. Chord-scale theory was ascendant during the moment when white entrepreneurial educators codified jazz studies as such in higher education, co-opting theoretical language about jazz while systematically abstracting it from any socio-historical context, particularly around questions of race. This has had cultural consequences and not just pedagogical ones: it is this transformation of jazz theory from a life-giving philosophical pursuit practiced by creative Black artists to a technocratic “objective” science that allows competitive (white) “jazz-bro” cultures to flourish on college campuses. In short, when jazz is reduced to a game, it becomes winnable.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspiration and more notes

Had a challenge to make a 'music sting' for a video card and it was a fun challenge. 5 -8 seconds to make a background mood for a video. Set a mood. The editor chose a iphone recording of me humming and having fun on acoustic instead of the thing I threw together quickly with layers of moody chords.

Sound and mood are the palettes of color we paint with.

Also listening to a podcast that is giving me inspiration to woodshed and refine things - Questlove interview podcast with jazz players (and other musicians). Aside from the personal connections and history of some of those musicians, just hearing some of the love of craft and the aspirations that drive them- huge inspiration. 'all musicians suck at laying back and doing less, want to hear the truth, listen to them play a ballad'. Stuff like that is a shot in the arm.

Also the new Depeche Mode release is surprisingly true to their pop synth sensibilities.

Am considering selling an instrument.

Recently a friend sang for a wedding and really shined. The reception featured a 2nd line performance at the end of the night- The Tramps (Zulu Tramps?) were fucking amazing. Pure skill at making a huge crowd drunk on sound and the feeling. Six guys playing marching style rocking a couple hundred people's face off.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SSWAN — Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster (577)

SSWAN: Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster by Jessica Ackerley, Patrick Shiroishi, Chris Williams, Luke Stewart, Jason Nazary

Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster is the first documented evidence of five adventurous instrumentalists performing together as a quintet. They are not strangers — there have been many collaborations among their ranks in various configurations — but this is the inaugural recording featuring this quintic structure as a single unit. Operating as a five-headed beast, the group are consummate improvisors, in tune with each other, and impressing a sense of camaraderie within their music. Video evidence documents just how effortlessly Jessica Ackerley, Patrick Shiroishi, Chris Williams, Luke Stewart and Jason Nazary engage in creative groupthink as they deploy musical ordnance built from a multitude of contexts. Their alloy is as multifaceted as they are, comprising free jazz, experimental noise, and sources further afield.

The moniker SSWAN, an acronym of the performers’ surnames, suggests both the gracefulness of the cygnus and the equal representation of everyone involved. While the group certainly moves with poise, they also imbue their music with a meticulous ardor. This energy is on display immediately, as Nazary’s punctilious drumming introduces the title track. Ackerley joins him almost immediately, in full-on shred mode. Her distortion-charged guitar zips around the room until Shiroishi’s soprano sax enters the fray. A brief respite gives Stewart (upright bass) and Williams (trumpet) space to introduce themselves. Shiroishi and Williams engage in a bit of call-and-response, while Stewart weaves around them and Ackerley hammers out a few chords. Nazary hasn’t let up the whole time; he’s set a baseline energy level from which the others can launch.

“Pattern Phases” exists at the more eclectic end of SSWAN’s palette, kicking off with very quiet breath exercises from Williams and Shiroishi. Stewart, Nazary and Ackerley punctuate the tiny gale with a hushed clatter. Eventually clicks, puckers, bubbles and assorted glossolalia reveal an alien syntax matched by a mechanical rattling and an oblique rhythm from Nazary and Stewart. Ackerley somehow creates the sound of a bicycle wheel with a foreign object in its spokes, as Williams’ trumpet swoops in and out of focus. It’s a jumble sale where all the objects have come alive, to the delight of the unsuspecting patrons. “A Miracle’s Worth” exists in an orbit between those of the two preceding pieces. It is both energetic and enigmatic. Ackerley lays down a morse code melody, while Nazary pounds out a ramshackle message in his own language. The other three enter like dust devils, stirring up clouds of drone. Williams deploys a mute, adding a growling menace to his melodies. A hush falls over the proceedings before Shiroishi appears, vocalising over Stewart’s bowed bass and a swirling mist of shaker beads. Ackerley introduces a pretty melody as Nazary pushes the proceedings toward the finish line, closing out this delightful session of finely wrought fire music.

Bryon Hayes

#SSWAN#invisibility is an unnatural disaster#577#bryon hayes#albumreview#dusted magazine#jessica ackerly#patrick shiroishi#luke stewart#jason nazary#improvised music#free jazz#jazz#chris williams

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 16, 2022

VOCALOID LEGENDS - 2021 Part 3

#631 - Yelling Together (shr) [Kagamine Rin, Ren]

Achievement Date: 21-04-04, Upload Date: 12-07-23

An interesting song with a very odd but nice groove. I think this might be shr’s most Japanese song yet. A lot of imagery, as per many traditional songs, not sure if this is a love song or more general, but it’s not a bad song.

#632 - Goodbye Sengen (Chinozo) [flower]

Achievement Date: 21-04-05, Upload Date: 20-04-13

A minor hit for Chinozo but blew up after the New Year and eventually became the first VOCALOID song to pass 100 Million views on YouTube. Very much fits the corona vibes of the time and the iconic pose made for a quick impression.

#633 - Vocaloids Only Repeat Two Chords Yelling "Tettet-Tetteree"

(GYARI) [Rin, Len, Yukari, Iroha, Miku, Luka]

Achievement Date: 21-04-23, Upload Date: 17-04-28

Kind XFD version of the Two Chords Series, combining the best bits of the three songs. A lot of the parts were shuffled to different VOCALOIDs which makes for a different take on the three songs. It’s a great 30 minutes, and this is the short version.

#C-4 - Cute Girlfriend (syudou) [Kafu]

Achievement Date: 21-04-29, Upload Date: 21-02-20

Now we enter the KAFU section of the list, there are seven of them, and next one won’t be there for ages. So these seven are special in a way. This is the beginning of the Girl/Boy series by syudou, and the most famous of all of syudou’s songs. I think the song capture the intricacies of KAFU pretty well and it’s pretty quick too.

#634 - Envy Baby (Kanaria) [GUMI]

Achievement Date: 21-04-29, Upload Date: 21-02-13

Hi! I wanna people save! English so bad that it comes back out to be cryptic… but the song itself is nice, sure it is a follow-up to KING, but I think it’s a good follow-up to KING, a nice mix of what worked before and new, intriguing ideas.

#635 - Nocturnal Kids (DECO*27) [Hatsune Miku]

Achievement Date: 21-04-30, Upload Date: 19-02-01

Song written as a collaboration with Bang Dreams, I believe. It’s a good song, regardless. Well, it has good parts but it doesn’t jell as a whole, unfortunately. Would have been nice if he stuck to a single idea, like his next song on the list.

#636 - SCREAM (Umetora) [GUMI]

Achievement Date: 21-05-02, Upload Date: 17-01-09

A rare recent Umetora song, which has him strip back to solo songs. Nice use of GUMI’s dual language mode and much more refined gravure idol track, although I kind of like the business of his earlier song, to be honest. This is very good though.

#637 - Telecaster B-Boy (long ver.) (Surii) [Kagamine Len]

Achievement Date: 21-05-07, Upload Date: 20-09-12

Long version adds a couple verses here and there. I like the theme of being yourself outside the confine of society, and another pretty clear TG theme here. Yeah, it ends with the couple killing themselves, but they are dancing in the PV! How fun…

#638 - Becoming potatoes (Neru) [Kagamine Rin, Len]

Achievement Date: 21-05-14, Upload Date: 20-03-30

Another funky depressing song but the master of those, one of Neru’s latest efforts, another song about everything falling apart and throwing all that failure away, now with more jazz swing and so on… I think ProSeca related, but not original?

#639 - Vampire (DECO*27) [Hatsune Miku]

Achievement Date: 21-05-16, Upload Date: 21-03-09

A song that shows DECO*27 is still at top of his game, he has a thing where he sees the trend and just… makes it his own. And the TikTok really works in his favor as he is able to concentrate on a single idea rather than string many unrelated ones. This is the seduction and the initial high portion of the Mannequin album, so… yeah.

#640 - Jackpot Sad Girl (syudou) [Hatsune Miku]

Achievement Date: 21-05-31, Upload Date: 20-10-24

A ProSeca song, for a Niigo event about heading out into society, and which syudou was in a similar position, apparently! That’s the first half, the second half is another response to Sand Planet, because that has become a genre of itself. Why do this on a commissioned work? Because he felt he needed to say in a commissioned work, as Sand Planet was a commissioned work itself. It’s biting in more ways than one.

3 notes

·

View notes