#gedmatch

Text

Comparing Genealogy Platforms - Ancestry.com, 23 and Me, and What Else?

There are several genealogy platforms besides Ancestry.com, each offering a variety of tools and features, especially around DNA testing, matching, and family tree building. Here’s a comparison of the main ones:

1. MyHeritage

DNA Testing: Offers its own DNA testing kits and also allows users to upload raw DNA data from other providers (like Ancestry or 23andMe) for free.

DNA Matching: Has a…

#23andme#ancestry.com#DNA Matching#DNA testing#family tree#family tree building#Family Tree Tools#FamilySearch#Findmypast#GEDmatch#genealogy platforms#Living DNA#MyHeritage

0 notes

Note

I have been thinking about taking a DNA test. Which one do you recommend?

Hello Anon, thank you for the ask. So I've taken actually a few different ancestry DNA tests, which I assume is what you mean based on the fact I once posted about my own 23andme results. I've taken Ancestry, 23andme, and even initially Genes for Good because it's free and contributes to a study being done by The University of Michigan. Unfortunately, as of checking today, Genes for Good is currently no longer sending out spit kits but you are still free to sign up via Facebook and fulfill the health related surveys. For the best DNA kit this honestly depends on what you're looking for.

Health

If you end up uploading your raw data to a website like Promethease to look over health information, you might get the most comprehensive SNP if you do the AncestryDNA kit. This is based on how many SNPs are genotyped by each company. Apparently, 23andme genotypes around 640k SNPS, while AncestryDNA and MyHeritage genotype about 700k SNPs. Now if you want a better breakdown of things you are potentially at risk for, for fun analysis of thing such as the likelihood of you having a certain skin tone, eye color, if you're likely to enjoy asparagus or not, etc., then 23andme is a great user friendly website for this. Apparently LivingDNA is great for meal and exercise plans. However, I believe the best you can do with health related is a whole genome sequencing but it's of course far more expensive than your typical ancestry kit.

Ancestry

While all of these kits can do what they claim with ancestry, I've found that some breakdowns are better than others. 23andme is very good with pointing out regions within a country and is to me the best with the breakdowns. This company is starting to improve with its pool of people with different ancestry backgrounds. I've heard of people saying AncestryDNA wins out in this aspect with people who are not white or are mixed, although I believe 23andme is more accurate to me speaking as someone with Anglo Indian ancestry on my maternal side.

I've personally also uploaded my data onto other websites like MyHeritage (which some people consider to be very outdated) and even Wegene to try getting a better breakdown of my Asian ancestry (which does offer an ancestry kit too). With Wegene, I learned it's mostly catered to those who have Chinese ancestry more than anything else and can greatly exaggerate how much Chinese ancestry someone has based on what I've seen for myself and from others on Reddit.

Family History

AncestryDNA seems to have the best database for finding relatives and for doing family history research hands down. However, 23andme also has a pretty big database for finding distant or lost relatives. I'm sure you've heard the news back from April 2018 when the Golden State Killer case finally found a suspect using the GEDMatch database to find relatives. Most kits on the GEDMatch website get its DNA raw data uploaded from FTDNA, MyHeritage and AncestryDNA but you can also upload your 23andme raw data as well. GEDMatch or its parent company however does NOT have its own ancestry testing kit.

However, this is far from the first time ancestry DNA results were used in a forensic setting as it was used to help catch the serial killer Derrick Todd Lee, who was on Death Row but died in 2016 from heart disease in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The Forensic Files episode showcasing Lee's case can be seen below. They apprehended Lee back in May 2003 after they extracted his DNA and genotyped upon discovering Carrie Lynn Yoder's body on March 3, 2003, which was 10 days after her death.

youtube

Overall, I tend to like 23andme the most BUT if you can do so I'd also try out AncestryDNA, particularly if you're interested in finding potential lost relatives or uploading your raw data onto other websites.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Someone else on one of my genealogical groups asked for how to access records on the Service du travail obligatoire, France's slave labor program to Nazi Germany. I've been looking for online access to those records for years since I found my great-grandparents in the Arolsen Archive as forced laborers in Munich. I can't help this person because I still haven't found that resource so I'm throwing it out here, anyone know where I and this other person (whom I am presuming is also American) can find records or other resources?

#France#Vichy France#French history#World War II#WWII#service du travail obligatoire#forced labor#WWII military fetishists will be blocked#still rambling about ancestry#I still have no idea what g-grandparents did to piss off the Nazis but I'm proud of them for doing it#*he* may have been part of the Service but *she* is recorded as being in Munich as slave labor the year before that went into effect#g-grandfather may have been part Roma too#and I've been told by others in these groups that French Roma/Romani often skipped the camps and went straight to slave labor#if he was part Roma it might be why his mother took him as a toddler and fled fascist Italy#mussolini also forced the expulsion of Roma out of Italy and into neighboring countries so that also could be how they ended up in France#if the Roma theory is accurate anyway#if he was then based on my DNA results and GEDmatch interpretations then he and his mother weren't fully Roma#but it's not like fascists would have cared and taken that into consideration#nazis tw#my great grandparents remain a mystery to me and my great-great grandparents even moreso

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I don’t rlly know how to explain this but I’ll try haha.

I recently found out I have Egyptian and specifically Coptic ancestry, through family tree making, matching with cousins, gedmatch, dna testing, etc and now personal confirmation from family/ancestors.

The problem is idrk who was the Coptic ones in my family as my dad died when I was four and I’ve had no contact with his family at all since. I know it came from his mother, but I can’t even give you her name let alone where she was from, or anything. Although I want to learn more and reconnect and eventually find out who they were exactly. It’s just hard because my dad’s living family has no contact w us and since he’s dead, it’s been hard to get records as well.

I would like to learn more about Coptic culture and Egypt in general but I am worried about people considering me a ‘culture thief’ since I only recently. found this out a few months ago but didn’t really have 100% confirmation until like 2 weeks ago. And even though I can prove genetically I have ancestry Coptic I can’t really say who my ancestors were which would probably make some skeptical.

Especially because I am African American and there already exists a rift between Egyptians and AAs bc of hoteps who claim Egyptian culture/claim Egyptians are just Arabs who ‘stole’ Egyptian culture. I want to be respectful but I’m unsure how to navigate this.

I guess I’m asking if you have any idea how I should move forward, or if you know of any resources to learn more? I want to be respectful, but I would also love to start to reconnect even if I don’t know where my ancestors were exactly from other than ‘Egypt’.

Hello! First of all, this is both a very respectful and a very personal ask, so I want to thank you for trusting me with that. I hope my answer can help you find peace with the matter a little.

Instead of trying to figure out if the overall sentiment of trying to reconnect is harmful or not, because there's really no answer to that in and of itself, and instead stop at every individual action taken to reconnect and asking: could this be harming anybody?

For example, if you'd like to pick up Coptic language lessons, could this action possibly be harmful to anyone? Not really. Is reading about Coptic culture and engaging with what survived of it in modern day harmful? I don't think so.

The only possible thing that I can think of that might be harmful is, I have awful experiences with certain diaspora Copts who have never really engaged with the community nor know much of it, who suddenly butt in conversations about Coptic politics in Egypt like they're an expert on it despite never having been or known anything about it themselves, but from the way you've written this ask I doubt you're the kind of person to do that anyway, seeing as you're being very respectful and that you recognize that there's some dissonance in your experience (which there's no shame in, but the self awareness is helpful as a guide of when to participate and when not to!)

I don't know if I said this before on this blog but, to my knowledge, the matter of the hotep subculture entails far more than just questioning the Egyptian identity, and seeing as I'm neither African American nor Black at all, I don't think it's my place to comment on it. I invite any of my Black followers to contribue to intra-community discussion in the reblogs/comments for you to read, though!

All I can promise you is that even if the notion that the population of Egypt was displaced rather than converted during the Arab conquest of Egypt is false, there still are Black Egyptians and there always have been. Sadly I'm sure there will always be people who try to make you feel like a pretender, but that is true of so many things and regardless of what you do, so always remember thay Black people have always been part of Egypt's history, and that nobody is entitled to know your personal details or family history and you don't need to disclose anything you're not comfortable with to prove anything to them.

As for resources, there's always a lot on Egyptology in general, so the specific topics that would be helpful to be aware of are: modern history of Copts (or Copts post the Arab Conquest of Egypt), the persecution of Copts, the decline of the Coptic language and the efforts to revive the language. The last two are especially pertinent nowadays.

Lastly you can always ask other Copts! I may not have all the answers but I'm sure between me and my followers we can find something helpful for you if you're trying to find a specific resource of have more questions. (The scarcity of resources is something we *all* have to deal with, even us here in Egypt, I'm afraid, but it's not a lost cause! You'd be surprised how much is out there on internet archives.)

I hope you have a lovely day. ♥️

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystery of Somerton Man SOLVED after 73 years as DNA finally identifies body

For decades, authorities, academics and the public alike have traded theories about the identity of the mysterious Somerton Man, whose body was found on a beach outside of Adelaide, Australia, on December 1, 1948. He was a Russian spy. A jilted lover poisoned by his paramour. A smuggler!?

The truth, however, is seemingly more mundane. A new DNA analysis suggests the Somerton Man is Carl “Charles” Webb, an electrical engineer from Melbourne who vanished from the public record in April 1947.

Colleen Fitzpatrick, a forensic genealogist who specializes in using DNA to solve cold cases, identified the Somerton Man using hairs caught in his death mask. To narrow down the pool of potential candidates, Fitzpatrick plugged the Somerton man’s DNA into the genealogical research database GEDmatch. After finding a match to a distant cousin, the researchers constructed a family tree of some 4,000 people. They then used archival records to search for individuals whose biographies mirrored what was known about the Somerton Man. Webb, who was born in the Australian state of Victoria in 1905, fit the bill.

On the matter of how he died city coroner said; “There was no indication of violence, and I am compelled to the finding that death resulted from poison, But I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person.”

Authorities in Adelaide exhumed the Somerton Man’s body last May and are currently conducting genetic testing on the remains. The last mention of Webb in the historical record dates to April 1947, when he left his wife. In October 1951, three years after the Somerton Man’s death, Dorothy placed a notice in the Age newspaper stating that she had begun divorce proceedings against Webb on the grounds of desertion. By then, Dorothy had moved from Melbourne to Bute, a town 89 miles northeast of Adelaide.

Records showed that Webb enjoyed reading and writing poetry, as well as betting on horse races. He had a sister who lived in Melbourne and was married to a man named Thomas Keane—likely the T. Keane whose name appears on the clothing in the Somerton Man’s suitcase. (As for the American origins of the attire, Abbott speculates that Keane bought the clothing second-hand from a G.I. stationed in Australia.)

Plenty of questions surrounding the case remain: Why did Webb come to Somerton Beach? What was his cause of death? Did he die by suicide? Was he murdered? These answers still remain and being looked into still.

There’s almost a sequel film here, not of ‘who is Somerton man?’, but now it’s ‘the mysterious case of Charles Webb’.”

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

I did a DNA test and uploaded the sequence to GedMatch (not super safe, but I'm not using anything like a real name and I'm not from/in the US). Anyway, there's a bunch of crowd sourced tools there, and one of them is "Are my parents related?" Just like that, right next to the "ancient DNA match" etc. It looks for repeating segments in your DNA because identical segments are unlikely to be coincidental.

There's an additional link provided if you go into the tool to explain why it's totally common in certain communities (like diaspora), and some additional resources in case you think you've uncovered something bad about your family history. No handwringing, no nothing.

that’s really interesting and I’m glad it’s neutral about it and not judgmental

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I did my Ancestry and I don't come from royalty. But man.... Some of the shit you find that was better left buried. The more I searched, the worse it got. It's gut twisting.

My dad's father side:

Through my grandpa I am descendant from slave owners. I prepared myself because of the state that I live in and the fact I knew we came from a long line of farmers / tobacco farmers. They actually show the list of slaves. They are marked "boy" and "girl" with their ages and no names. It shows how much they was paid for and it's so sad. It literally made me sick looking at this. And one of them on that list, I am like 99.9% sure it's my 6x-grandma because of the date and age. You know how that came about :( I am sure it wasn't out of love. They had my 5x-grandma marked as Mulatto. It shows her dad is white (obviously) and her mom who is not actually her mom (white). So his wife must had took in the child, I don't know. That is unusual. I am still trying to figure that out. I did DNA and sure enough, I am like 99% European with 1% Senegal. I learned that I can send in my discoveries and the slave list to help people trace their African slave ancestors which is what I am going to do.

My dad's mother side:

My great-great grandpa was a Nazi, which is why my grandma and great-grandpa wouldn't talk about him.

My mom's father side:

I am descendant of a serial killer from the mid to late 1800s. I decided submit my DNA over to Gedmatch and enter it into the criminal database so that it can help them solve crimes that he may had been involved in that they aren't sure of yet.

My mom's mother side:

They was moonshiners and a bunch of racist ass red coats. There was a few slave owners I found that I am working on so that I can send in my discoveries with them too.

No kings. No queens. Although they wasn't necessarily good either. No aliens either :\

No aliens!?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hackers Selling Stolen Customer DNA Data From 23AndMe, Company Faces Class Action Lawsuit

Oct. 9, 2023

Biotech company 23andMe Inc. allegedly failed to protect the genetic information of thousands of people that was exposed in a data breach announced Oct. 6, a proposed federal class action said.

Monica Santana and Paula Kleynburd alleged that 23andMe, a provider of genetic testing services, maintained their personal information in a reckless manner and failed to use reasonable and adequate measures to keep their data safe.

Information exposed in the breach included names, sex, date of birth, genetic ancestry results, profile photos, and geographical location, according to a complaint filed Monday in the US District Court for the Northern District of California.

Some of the information has appeared for sale online, including that of prominent figures such as Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk and Sergey Brin, according to a press account cited in the lawsuit.

The company also failed to provide prompt and adequate notice of the incident, the complaint said. 23andMe didn’t respond immediately to a Bloomberg Law request for comment.

Read more

See 🤷🏽♀️. Willingly giving up your DNA to a genetic testing company that's a test done for entertainment purposes for what? Didn't this happen before or was that GedMatch. It doesn't mention it in this article, but the one I read about a week ago stated that the 23andMe hackers were going after data for those showing results for Ashkenazi and Chinese descent. The timing is rather...interesting.

I was waiting for this shit to hit the fan. 23andMe was tryna be subtle about the whole thing. "When asked about the post, the company initially denied that the information was legitimate, calling it a 'misleading claim.'"

Whole time:

Now the shit going to the highest bidders. Chile.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

CeCe Moore, an actress and director-turned-genetic genealogist, stood behind a lectern at New Jersey’s Ramapo College in late July. Propelled onto the national stage by the popular PBS show “Finding Your Roots,” Moore was delivering the keynote address for the inaugural conference of forensic genetic genealogists at Ramapo, one of only two institutions of higher education in the U.S. that offer instruction in the field. It was a new era, Moore told the audience, a turning point for solving crime, and they were in on the ground floor. “We’ve created this tool that can accomplish so much,” she said.

Genealogists like Moore hunt for relatives and build family trees just as traditional genealogists do, but with a twist: They work with law enforcement agencies and use commercial DNA databases to search for people who can help them identify unknown human remains or perpetrators who left DNA at a crime scene.

The field exploded in 2018 after the arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo as the notorious Golden State Killer, responsible for more than a dozen murders across California. DNA evidence collected from a 1980 double murder was analyzed and uploaded to a commercial database; a hit to a distant relative helped a genetic genealogist build an elaborate family tree that ultimately coalesced on DeAngelo. Since then, hundreds of cold cases have been solved using the technique. Moore, among the field’s biggest evangelists, boasts of having personally helped close more than 200 cases.

The practice is not without controversy. It involves combing through the genetic information of hundreds of thousands of innocent people in search of a perpetrator. And its practitioners operate without meaningful guardrails, save for “interim” guidance published by the Department of Justice in 2019.

The last five years have been like the “Wild West,” Moore acknowledged, but she was proud to be among the founding members of the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Accreditation Board, which is developing professional standards for practitioners. “With this incredibly powerful tool comes immense responsibility,” she solemnly told the audience. The practice relies on public trust to convince people not only to upload their private genetic information to commercial databases, but also to allow police to rifle through that information. If you’re doing something you wouldn’t want blasted on the front page of the New York Times, Moore said, you should probably rethink what you’re doing. “If we lose public trust, we will lose this tool.”

Despite those words of caution, Moore is one of several high-profile genetic genealogists who exploited a loophole in a commercial database called GEDmatch, allowing them to search the DNA of individuals who explicitly opted out of sharing their genetic information with police.

The loophole, which a source demonstrated for The Intercept, allows genealogists working with police to manipulate search fields within a DNA comparison tool to trick the system into showing opted-out profiles. In records of communications reviewed by The Intercept, Moore and two other forensic genetic genealogists discussed the loophole and how to trigger it. In a separate communication, one of the genealogists described hiding the fact that her organization had made an identification using an opted-out profile.

The communications are a disturbing example of how genetic genealogists and their law enforcement partners, in their zeal to close criminal cases, skirt privacy rules put in place by DNA database companies to protect their customers. How common these practices are remains unknown, in part because police and prosecutors have fought to keep details of genetic investigations from being turned over to criminal defendants. As commercial DNA databases grow, and the use of forensic genetic genealogy as a crime-fighting tool expands, experts say the genetic privacy of millions of Americans is in jeopardy.

Moore did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment.

“If we can’t trust these practitioners, we certainly cannot trust law enforcement.”

To Tiffany Roy, a DNA expert and lawyer, the fact that genetic genealogists have accessed private profiles — while simultaneously preaching about ethics — is troubling. “If we can’t trust these practitioners, we certainly cannot trust law enforcement,” she said. “These investigations have serious consequences; they involve people who have never been suspected of a crime.” At the very least, law enforcement actors should have a warrant to conduct a genetic genealogy search, she said. “Anything less is a serious violation of privacy.”

CeCe Moore appears as a guest on “Megyn Kelly Today” on Aug. 14, 2018.

Photo: Zach Pagano/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

The Wild West

Forensic genetic genealogy evolved from the direct-to-consumer DNA testing craze that took hold roughly a decade ago. Companies like 23andMe and Ancestry offered DNA analysis and a database where results could be uploaded and searched against millions of other profiles, offering consumers a powerful new tool to dig into their heritage through genetics.

It wasn’t long before entrepreneurial genealogists realized this information could also be used to solve criminal cases, especially those that had gone cold. While the arrest of the Golden State Killer captured national attention, it was not the first case solved by forensic genetic genealogy. Two weeks earlier, genetic genealogists Margaret Press and Colleen Fitzpatrick joined officials in Ohio to announce that “groundbreaking work” had allowed authorities to identify a young woman whose body was found by the side of a road back in 1981. Formerly known as “Buckskin Girl” for the handmade pullover she wore, Marcia King was given her name back through genetic genealogy. “Everyone said it couldn’t be done,” Press said.

The type of consumer DNA information used in forensic genetic genealogy is far different from that uploaded to the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, a decades-old network administered by the FBI. The DNA entered in CODIS comes from individuals convicted of or arrested for serious crimes and is often referred to as “junk” DNA: short pieces of unique genetic code that don’t carry any individual health or trait information. “It’s not telling us how the person looks. It’s not telling us about their heritage or their phenotypic traits,” Roy said. “It’s a string of numbers, like a telephone number.”

In contrast, the DNA testing offered by direct-to-consumer companies is “as sensitive as it gets,” Roy said. “It tells you about your origins. It tells you about your relatives and your parentage, and it tells you about your disease propensity.” And it has serious reach: While CODIS searches the DNA of people already identified by the criminal justice system, the commercial databases have the potential to search through the DNA of everyone else.

Individuals can upload their test results to any number of databases; at present, there are five main commercial portals. Ancestry and 23andMe are the biggest players in the field, with databases containing roughly 23 million and 14 million profiles. Individuals must test with the companies to gain access to their databases; neither allow DNA results obtained from a different testing service. Both Ancestry and 23andMe forbid police, and the genetic genealogists who work with them, from accessing their data for crime-fighting purposes. “We do not allow law enforcement to use Ancestry’s service to investigate crimes or to identify human remains” absent a valid court order, Ancestry’s privacy policy notes. The two companies provide regular transparency reports documenting law enforcement requests for user information.

MyHeritage, home to some 7 million DNA profiles, similarly bars law enforcement searches, but it does allow individuals to upload DNA results obtained from other sources.

And then there are FamilyTreeDNA and GEDmatch, which grant police access but give users the choice of opting in or out. Both allow anyone to upload their DNA results and have upward of 1.8 million profiles. But neither company routinely publicizes the number of customers who have opted in, said Leah Larkin, a veteran genetic genealogist and privacy advocate from California. Larkin writes about issues in the field — including forensic genetic genealogy, which she does not practice — on her website the DNA Geek. Larkin estimates that roughly 700,000 GEDmatch profiles are opted in. She suspects that even more are opted in on FamilyTreeDNA; opting in is the default for the company’s U.S. customers and “it’s not obvious how to opt out.”

But even opting out of law enforcement searches doesn’t guarantee that a profile won’t be accessed: A loophole in GEDmatch offers users working with law enforcement agencies a back door to accessing protected profiles. A source showed The Intercept how to exploit the loophole; it was not an obvious weakness or one that could be triggered mistakenly. Rather, it was a back door that required experience with the platform’s various tools to open.

GEDmatch’s parent company, Verogen, did not respond to a request for comment.

Law enforcement officials leave the home of accused serial killer Joseph James DeAngelo in Citrus Heights, Calif., on April 24, 2018.

Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

An Open Secret

In forensic genetic genealogy circles, the GEDmatch loophole had long been an open secret, sources told The Intercept, one that finally surfaced publicly during the Ramapo College conference in late July.

Roy, the DNA expert, was giving a presentation titled “In the Hot Seat,” a primer for genealogists on what to expect if called to testify in a criminal case. There was a clear and simple theme: “Do not lie,” Roy said. “The minute you’re caught in a lie is the minute that it’s going to be difficult for people to use your work.”

As part of the session, David Gurney, a professor of law and society at Ramapo and director of the college’s nascent Investigative Genetic Genealogy Center, joined Roy for a mock questioning of Cairenn Binder, a genealogist who heads up the center’s certificate program.

Gurney, simulating direct examination, walked Binder through a series of friendly questions. Did she have access to DNA evidence or genetic code during her investigations? No, she replied. Could she see everyone who’d uploaded DNA to the databases? No, she said, only those who’d opted in to law enforcement searches.

Roy, playing the part of opposing counsel, was pointed in her cross-examination: Was Binder aware of the GEDmatch loophole? And had she used it? Yes, Binder said. “How many times?” Roy asked.

“A handful,” Binder replied. “Maybe up to a dozen.”

Binder’s answers quickly made their way into a private Facebook group for genetic genealogy enthusiasts, prompting a response from the DNA Doe Project, a volunteer-driven organization led by Press, one of the women who identified the Buckskin Girl. Before joining Ramapo College, Binder had worked for the DNA Doe Project.

In a statement posted to the Facebook group, Pam Lauritzen, the project’s communications director, said the loophole was an artifact of changes GEDmatch implemented in 2019, when it made opting out the default for all profiles. “While we knew that the intent of the change was to make opted-out users unavailable, some volunteers with the DNA Doe Project continued to use the reports that allowed access to profiles that were opted out,” she wrote. That use was neither “encouraged nor discouraged,” she continued. Still, she claimed the access was somehow “in compliance” with GEDmatch’s terms of service — which at the time promised that DNA uploaded for law enforcement purposes would only be matched with customers who’d opted in — and that the loophole was closed “years ago.”

It was a curious statement, particularly given that Press, the group’s co-founder, was among the genealogists who discussed the GEDmatch loophole in communications reviewed by The Intercept. In 2020, she described the DNA Doe Project using an opted-out profile to make an identification — and devising a way to keep that quiet.

Press referred The Intercept’s questions to the DNA Doe Project, which declined to comment.

In July 2020, GEDmatch was hacked, which resulted in all 1.45 million profiles then contained in the database to be briefly opted in to law enforcement matching; at the time, BuzzFeed News reported, just 280,000 profiles had opted in. GEDmatch was taken offline “until such time that we can be absolutely sure that user data is protected against potential attacks,” Verogen wrote on Facebook.

In the wake of the hack, a genetic genealogist named Joan Hanlon was asked by Verogen to beta test a new version of the site. According to records of a conversation reviewed by The Intercept, Press and Moore, the featured speaker at the Ramapo conference, discussed with Hanlon their tricks to access opted-out profiles and whether the new website had plugged all backdoor access. It hadn’t. It’s unclear if anyone told Verogen; as of this month, the back door was still open.

Hanlon did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment.

In January 2021, GEDmatch changed its terms of service to opt everyone in for searches involving unidentified human remains, making the back door irrelevant for genealogists who only worked on Doe cases, but not those working with authorities to identify perpetrators of violent crimes.

Undisclosed Methods

Exploitation of the GEDmatch loophole isn’t the only example of genetic genealogists and their law enforcement partners playing fast and loose with the rules.

Law enforcement officers have used genetic genealogy to solve crimes that aren’t eligible for genetic investigation per company terms of service and Justice Department guidelines, which say the practice should be reserved for violent crimes like rape and murder only when all other “reasonable” avenues of investigation have failed. In May, CNN reported on a U.S. marshal who used genetic genealogy to solve a decades-old prison break in Nebraska. There is no prison break exception to the eligibility rules, Larkin noted in a post on her website. “This case should never have used forensic genetic genealogy in the first place.”

“This case should never have used forensic genetic genealogy in the first place.”

A month later, Larkin wrote about another violation, this time in a California case. The FBI and the Riverside County Regional Cold Case Homicide Team had identified the victim of a 1996 homicide using the MyHeritage database — an explicit violation of the company’s terms of service, which make clear that using the database for law enforcement purposes is “strictly prohibited” absent a court order.

“The case presents an example of ‘noble cause bias,’” Larkin wrote, “in which the investigators seem to feel that their objective is so worthy that they can break the rules in place to protect others.”

MyHeritage did not respond to a request for comment. The Riverside County Sheriff’s Office referred questions to the Riverside district attorney’s office, which declined to comment on an ongoing investigation. The FBI also declined to comment.

Violations have even come from inside the DNA testing companies. Back in 2019, GEDmatch co-founder Curtis Rogers unilaterally made an exception to the terms of service, without notifying the site’s users, to allow police to search for someone suspected of assault in Utah. It was a tough call, Rogers told BuzzFeed News, but the case in question “was as close to a homicide as you can get.”

It appears that violations have also spread to Ancestry, which prohibits the use of its DNA data for law enforcement purposes unless the company is legally compelled to provide access. Genetic genealogists told The Intercept that they are aware of examples in which genealogists working with police have provided AncestryDNA testing kits to the possible relatives of suspects — what’s known as “target testing” — or asked customers for access to preexisting accounts as a way to unlock the off-limits data.

A spokesperson for Ancestry did not answer The Intercept’s questions about efforts to unlock DNA data for law enforcement purposes via a third party. Instead, in a statement, the company reiterated its commitment to maintaining the privacy of its users. “Protecting our customers’ privacy and being good stewards of their data is Ancestry’s highest priority,” it read. The company did not respond to follow-up questions.

As it turns out, the genetic genealogy work in the Golden State Killer case was also questionable: The break that led to DeAngelo came after genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter uploaded DNA from the double murder to MyHeritage, according to the Los Angeles Times. Rae-Venter told the Times that she didn’t notify the company about what she was doing but that her actions were approved by Steve Kramer, the FBI’s Los Angeles division counsel at the time. “In his opinion, law enforcement is entitled to go where the public goes,” Rae-Venter told the paper.

Just how prevalent these practices are may never fully be known, in part because police and prosecutors regularly seek to shield genetic investigations from being vetted in court. They argue that what they obtain from forensic genetic genealogy is merely a tip, like information provided by an informant, and is exempt from disclosure to criminal defendants.

That’s exactly what’s happening in Idaho, where Bryan Kohberger is awaiting trial for the 2022 murder of four university students. For months, the state failed to disclose that it had used forensic genetic genealogy to identify Kohberger as a suspect. A probable cause statement methodically laying out the evidence that led cops to his door conspicuously omitted any mention of genetic genealogy. Kohberger’s defense team has asked to see documents related to the genealogy work as it prepares for an October trial, but the state has refused, saying the defense has no right to any information about the genetic genealogy it used to crack the case.

Prosecutors said it was the FBI that did the genetic genealogy work, and few records were created in the process, leaving little to turn over. But the state also argued that it couldn’t turn over information because the family tree the FBI created was extensive — including “the names and personal information of … hundreds of innocent relatives” — and the privacy of those individuals needed to be maintained. According to the state, it shouldn’t even have to say which genetic database — or databases — it used.

Kohberger’s attorneys argue that the state’s position is preposterous and keeps them from ensuring that the work undertaken to find Kohberger was above board. “It would appear that the state is acknowledging that the companies are providing personal information to the state and that those companies and the government would suffer if the public were to realize it,” one of Kohberger’s attorneys wrote. “The statement by the government implies that the databases searched may be ones that law enforcement is specifically barred from, which explains why they do not want to disclose their methods.”

A hearing on the issue is scheduled for August 18.

An AncestryDNA user points to his family tree on Ancestry.com on June 24, 2016.

Photo: RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images

“A Search of All of Us”

Natalie Ram, a law professor at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law and an expert in genetic privacy, believes forensic genetic genealogy is a giant fishing expedition that fails the particularity requirement of the Fourth Amendment: that law enforcement searches be targeted and based on individualized suspicion. Finding a match to crime scene DNA by searching through millions of genetic profiles is the opposite of targeted. Forensic genetic genealogy, according to Ram, “is fundamentally a search of all of us every time they do it.”

While proponents of forensic genetic genealogy say the individuals they’re searching have willingly uploaded their genetic information and opted in to law enforcement access, Ram and others aren’t so sure that’s the case, even when practitioners adhere to terms of service. If the consent is truly informed and voluntary, “then I think that it would be ethical, lawful, permissible for law enforcement to use that DNA … to identify those individuals who did the volunteering,” Ram said. But that’s not who is being identified in these cases. Instead, it’s relatives — and sometimes very distant relatives. “Our genetic associations are involuntary. They’re profoundly involuntary. They’re involuntary in a way that almost nothing else is. And they’re also immutable,” she said. “I can estrange myself from my family and my siblings and deprive them of information about what I’m doing in my life. And yet their DNA is informative on me.”

Jennifer Lynch, general counsel at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, agrees. “We’re putting other people’s privacy on the line when we’re trying to upload our own genetic information,” she said. “You can’t consent for another person. And there’s just not an argument that you have consented for your genetic information to be in a database when it’s your brother who’s uploaded the information, or when it’s somebody you don’t even know who is related to you.”

To date, efforts to rein in the practice as a violation of the Fourth Amendment have presented some problems. A person whose arrest was built on a foundation of genetic genealogy, for example, might have been harmed by the genealogical fishing expedition but lack standing to bring a case; in the strictest sense, it wasn’t their DNA that was searched. In contrast, a third cousin whose DNA was used to identify a suspect could have standing to bring a suit, but they might be hard-pressed to prove they were harmed by the search.

If police are getting hits to suspects by violating companies’ terms of service — using databases that bar police searching — that “raises some serious Fourth Amendment questions” because no expectation of privacy has been waived, Ram said. Of course, ferreting out such violations would require that the information be disclosed in court, which isn’t happening.

At present, the only real regulators of the practice are the database owners: private companies that can change hands or terms of service with little notice. GEDmatch, which has at least once bent its terms to accommodate police, was started by two genealogy hobbyists and then sold to the biotech company Verogen, which in turn was acquired last winter by another biotech company, Qiagen. Experts like Ram and Lynch worry about the implications of so much sensitive information held in for-profit hands — and readily exploited by police. The “platforms right now are the most powerful regulators we have for most Americans,” Ram said. Police regulate “after a fashion, in a fashion, by what they do. They tell us what they’re willing to do by what they actually do,” she added. “But by the way, that’s like law enforcement making rules for itself, so not exactly a diverse group of stakeholders.”

For now, Ram said, the best way to regulate forensic genetic genealogy is by statute. In 2021, Maryland lawmakers passed a comprehensive law to restrain the practice. It requires police to obtain a warrant before conducting a genetic genealogy search — certifying that the case is an eligible violent felony and that all other reasonable avenues of investigation have failed — and notify the court before gathering DNA evidence to confirm the suspect identified via genetic genealogy is, in fact, the likely perpetrator. Currently, police use surreptitious methods to collect DNA without judicial oversight: mining a person’s garbage, for example, for items expected to contain biological evidence. In the Golden State Killer case, DeAngelo was implicated by DNA on a discarded tissue.

The Maryland law also requires police to obtain consent from any third party whose DNA might help solve a crime. In the Kohberger case, police searched his parents’ garbage, collecting trash with DNA on it that the lab believed belonged to Kohberger’s father. In a notorious Florida case, police lied to a suspect’s parents to get a DNA sample from the mother, telling her they were trying to identify a person found dead whom they believed was her relative. Those methods are barred under the Maryland law.

Montana and Utah have also passed laws governing forensic genetic genealogy, though neither is as strict as Maryland’s.

MyHeritage DNA kits are displayed at the RootsTech conference in Salt Lake City on Feb. 9, 2017.

Photo: George Frey/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Solving Crime Before It Happens

The rise of direct-to-consumer DNA testing and forensic genetic genealogy raises another issue: the looming reality of a de facto national DNA database that can identify large swaths of the U.S. population, regardless of whether those individuals have uploaded their genetic information. In 2018, researchers led by the former chief science officer at MyHeritage predicted that a database of roughly 3 million people could identify nearly 100 percent of U.S. citizens of European descent. “Such a database scale is foreseeable for some third-party websites in the near future,” they concluded.

“All of a sudden, we have a national DNA database, and we didn’t ever have any kind of debate about whether we wanted that in our society.”

“All of a sudden, we have a national DNA database,” said Lynch, “and we didn’t ever have any kind of debate about whether we wanted that in our society.” A national database in “private hands,” she added.

By the time people started worrying about this as a policy issue, it was “too late,” Moore said during her address at the Ramapo conference. “By the time the vast majority of the public learned about genetic genealogy, we’d been quietly building this incredibly powerful tool for human identification behind the scenes,” she said. “People sort of laughed, like, ‘Oh, hobbyists … you do your genealogy, you do your adoption,’ and we were allowed to build this tool without interference.”

Moore advocated for involving forensic genetic genealogy earlier in the investigative process. Doing so, she argued, could focus police on guilty parties more quickly and save innocent people from needless law enforcement scrutiny. In fact, she told the audience, she believes that forensic genetic genealogy can help to eradicate crime. “We can stop criminals in their tracks,” she said. “I really believe we can stop serial killers from existing, stop serial rapists from existing.”

“We are an army. We can do this! So repeat after me,” Moore said, before leading the audience in a chant. “No more serial killers!”

Update: August 18, 2023, 3:55 p.m. ET

After this article was published, Margaret Press, founder of the DNA Doe Project, released a statement in response to The Intercept’s findings. Press acknowledged that between May 2019 and January 2021, the organization’s leadership and volunteers made use of GEDmatch tools that provided access to DNA profiles that were opted out of law enforcement searches, which she described as “a bug in the software.” Press stated:

We have always been committed to abide by the Terms of Service for the databases we used, and take our responsibility to our law enforcement and medical examiner partner agencies extremely seriously. In hindsight, it’s clear we failed to consider the critically important need for the public to be able to trust that their DNA data will only be shared and used with their permission and under the restrictions they choose. We should have reported these bugs to GEDmatch and stopped using the affected reports until the bugs were fixed. Instead, on that first day when we found that all of the profiles were set to opt-out, I discouraged our team from reporting them at all. I now know I was wrong and I regret my words and actions.

#Police Are Getting DNA Data From People Who Think They Opted Out#stolen dna#end qualified immunity#thugs with badges and guns#stealing dna with a badge and gun

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mystery of Somerton Man SOLVED after 73 years as DNA finally identifies body

For decades, authorities, academics and the public alike have traded theories about the identity of the mysterious Somerton Man, whose body was found on a beach outside of Adelaide, Australia, on December 1, 1948. He was a Russian spy. A jilted lover poisoned by his paramour. A smuggler!?

The truth, however, is seemingly more mundane. A new DNA analysis suggests the Somerton Man is Carl “Charles” Webb, an electrical engineer from Melbourne who vanished from the public record in April 1947.

Colleen Fitzpatrick, a forensic genealogist who specializes in using DNA to solve cold cases, identified the Somerton Man using hairs caught in his death mask. To narrow down the pool of potential candidates, Fitzpatrick plugged the Somerton man’s DNA into the genealogical research database GEDmatch. After finding a match to a distant cousin, the researchers constructed a family tree of some 4,000 people. They then used archival records to search for individuals whose biographies mirrored what was known about the Somerton Man. Webb, who was born in the Australian state of Victoria in 1905, fit the bill.

On the matter of how he died city coroner said; “There was no indication of violence, and I am compelled to the finding that death resulted from poison, But I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person.”

Authorities in Adelaide exhumed the Somerton Man’s body last May and are currently conducting genetic testing on the remains. The last mention of Webb in the historical record dates to April 1947, when he left his wife. In October 1951, three years after the Somerton Man’s death, Dorothy placed a notice in the Age newspaper stating that she had begun divorce proceedings against Webb on the grounds of desertion. By then, Dorothy had moved from Melbourne to Bute, a town 89 miles northeast of Adelaide.

Records showed that Webb enjoyed reading and writing poetry, as well as betting on horse races. He had a sister who lived in Melbourne and was married to a man named Thomas Keane—likely the T. Keane whose name appears on the clothing in the Somerton Man’s suitcase. (As for the American origins of the attire, Abbott speculates that Keane bought the clothing second-hand from a G.I. stationed in Australia.)

Plenty of questions surrounding the case remain: Why did Webb come to Somerton Beach? What was his cause of death? Did he die by suicide? Was he murdered? These answers still remain and being looked into still.

There’s almost a sequel film here, not of ‘who is Somerton man?’, but now it’s ‘the mysterious case of Charles Webb’.”

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can a 6 cM connection be meaningful?

When it comes to small DNA segments, we’ve heard the “glass half empty” version of the story many times. Here’s the other side of that story.

Submitted for your consideration: A pair of third cousins twice removed and their 6 cM connection…

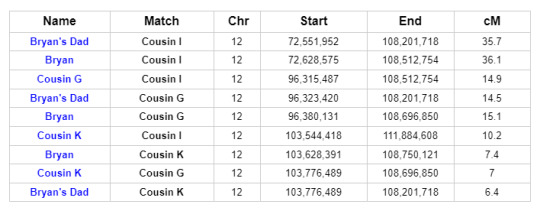

According to AncestryDNA, Bryan Smith and his cousin, K, share 6 cM of DNA across 1 segment. And according to Ancestry’s ThruLines, Bryan and Cousin K share a pair of third great grandparents, Reuben Willis Smith and his wife Mary Connell.

The cM value is certainly consistent with the identified relationship but did Bryan and Cousin K inherit their shared DNA from the Smith ancestry as shown? Is the 6 cM segment even valid or could it be an artifact of an imperfect DNA matching algorithm?

Let’s start with an easy evaluation: the shared match list.

Among Bryan and K’s list of shared matches at AncestryDNA:

HG, a descendant of Reuben and Mary’s son, Charles Thomas Smith (HG shares 57 cM with Bryan)

RR, a descendant of Reuben and Mary’s daughter, Fannie Janes Smith (RR shares 47 cM with Bryan and 38 cM with K)

IG, another descendant of Reuben and Mary’s son, Charles Thomas Smith (IG shares 47 cM with Bryan and 71 cM with K)

And at least three other descendants of Reuben and Mary are on the shared match list.

So we’re off to a promising start. In addition to the fact that Bryan and K share DNA and a paper trail leading to Ruben and Mary, this group of matches gives us more evidence suggesting that Bryan and K might be related as suspected.

But what about that 6 cM segment shared by Bryan and K? Is it valid? Did it come from the shared Smith ancestors or did it originate elsewhere?

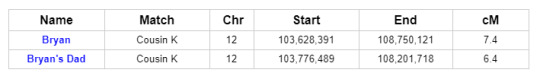

To get the most comprehensive help in answering these questions, we turn to GEDmatch. As indicated in the ThruLine image above, both Bryan and his father are related to DNA Cousin K through their Smith line. And because K is on GEDmatch, we can see that Bryan and his father both share DNA with K on a specific portion of Chromosome 12:

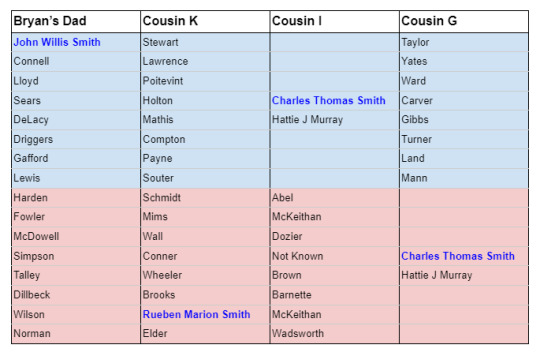

Further investigation reveals that two other descendants of Reuben and Mary, Cousins I and G, share DNA with Bryan and his father on Chromosome 12 in roughly the same location. In fact, all of the matches in question match each other on Chromosome 12:

This is what we call a Triangulation Group. It brings the possible genetic connections into sharper focus.

The common segment shared by all of the members of this Triangulation Group indicates that they all share a common ancestor. And we’ve already identified shared ancestry through the Smith line. Cousins I and G are first cousins once removed and they are descendants of Reuben and Mary’s son Charles Thomas Smith...

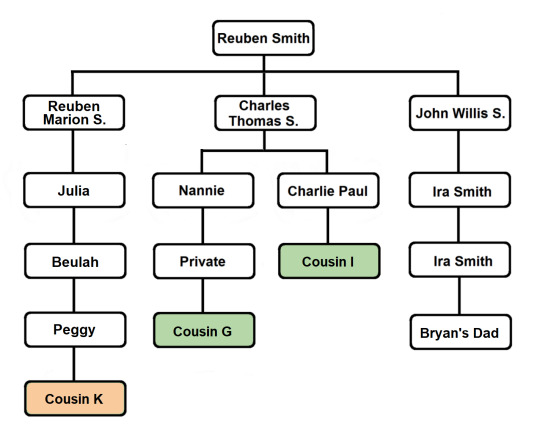

A review of the pedigrees of the matches in question reveals no lines of shared ancestry other than the known shared Smith line. This investigation is summarized briefly in the table below, listing 2nd great grandparent surnames and shared ancestors (blue for paternal names and surnames, light red for maternal names and surnames):

Although we cannot say with perfect certainty that there is no additional common ancestry that conceivably could account for the shared segment of DNA on Chromosome 12, the known evidence doesn’t leave room for much doubt.

For completeness, here’s a chart summarizing the amount of DNA shared by the relatives in question:

And cluster analysis for Cousin G yields a cluster with eight descendants of Reuben Willis Smith, including Bryan Smith and Cousin K:

Not everyone will feel the need to go this far to investigate a 6 cM connection. But this post provides examples of ways to investigate the validity of an ordinary small segment and to determine whether the shared DNA legitimately belongs with the presumed paper trail source of the DNA.

Discussion

Skepticism regarding small segments of shared DNA is appropriate. In comparison to larger shared segments, such segments are more likely to be IBS (false). Additionally, even when small segments can be shown to be reliable, we have to grapple with the fact that small segments can be too old to fall within the reach of reliable historical documentation.

With the exponential growth of the DNA matching databases, the impetus to explore distant matches waned. Reluctance to do the strenuous work involved in using small segments grew. With access to strong genetic connections leading back to target ancestors, why bother with low cM connections?

The sentiment is understandable!

On the other hand, I believe that excessive skepticism has impeded progress in genetic genealogy. As databases have grown, our opportunities for research have multiplied and our research techniques have improved. But at the same time, goalposts for small segment success have been moved to poorly-defined and very unreasonable points.

[From the skeptics: Your success with a small segment doesn’t count if you find a larger segment in a relative! I don’t want to hear about triangulation! Visual phasing is not allowed!]

If we applied such arbitrary restrictions to all areas of genealogy, we’d struggle to get our work done!

Even with our luxuriously large DNA databases, distant genetic connections are the only connections available in some areas of investigation (or to people who hail from less heavily-tested populations). Defeatist refusal to accept low cM matches as evidence in genetic genealogy needlessly limits our potential.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m fully in favor of scholarly rigor. But let’s not allow skepticism to pave the way for denialism!

When distant genetic connections are found to be of dubious quality, they should be set aside. But shared segments should not be judged on the basis of size alone. Even the most fervent opponents of small-segment research will admit that small segments are often valid (IBD). And while these opponents frequently cite IBD/IBS percentages, they ironically fail to see that our ability to find these percentages points directly to a practical method for sorting distant matches on an individual basis.

We are privileged to have access to enormous databases of incredibly valuable genetic information. More than a statistical hiccup that can lead us serendipitously to more reliable information, small DNA segments are messages we carry with us every day, testifying to our connections with our ancestors. Genetic information, even in small amounts, can be just as valuable as any other form of information. We should be good stewards of that information and we should invest good faith effort in understanding how our distant matches can inform us about our rich ancestral history.

I’ll close with this analogy for small segments:

You want some refreshing water but the glass is only half-full. Drink it or toss it out?

Posted with Bryan Smith’s permission. 17 May 2023

#genetic genealogy#DNA testing#DNA#small segments#visual phasing#Triangulation#dna segment#DNA segment triangulation#DNA clustering#clustering#pedigree#family tree#ThruLines

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

((After 56 years, Miss X Jane Doe has been identified as 21 year old Patrona "Patra" Patmios. Born in Greece but later adopted into the United States by the Patmios family, her half-brother uploaded his dna into GEDmatch and put an end to this decades-old mystery. I hope that Patra can rest peacefully now and that her family takes solace in knowing that she's been found.))

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Privacyexperts kritisch over inzet commerciële dna-databases bij coldcasezaken

Privacyexperts zijn kritisch over kabinetsplannen om commerciële dna-databases te gebruiken bij het oplossen van coldcasezaken, zoals aangekondigd in het hoofdlijnenakkoord. Justitie gebruikte vorig jaar de commerciële dna-databases GEDmatch en FamilyTreeDNA, sites waar mensen van over de hele wereld hun dna daarnaartoe kunnen sturen om bijvoorbeeld verwanten te vinden of hun geografische…

0 notes

Text

Fallen Branches: An Update!

In my post, Fallen Branches, I talk about how I discovered the man I've always believed to be my great-grandfather—Hugh Dorsey Clifton Sr.—wasn't my ancestor after all. Instead, my great-grandfather was a man named Joseph David Singleton.

Thankfully, I had forceful determination and a draft card to lead the way down this unknown trail. From there, I found a 1940 census record that verified Joseph Singleton was my great-grandfather! Next, I found an obituary that sadly didn't list any known relatives (my great-grandmother or their children together).

Among many other things, one of my research methods has been to seek out DNA relatives that have "Singleton" as one of their listed names. I made a hit on GEDmatch and even made contact with a cousin! I couldn't believe it!

So imagine my surprise when I recently made contact with another Singleto-related cousin on 23andMe! Bless them with the greatest luck, because they just helped me to confirm not only that the man in the obituary is my great-grandfather, but gave me knowledge about Joseph's relatives as well!!

To say I'm excited is a drastic understatement! I've gone full genealogical geek mode!!

As much as it pains me to say it, though, I'm still nowhere near ready to do anything with this information. While my new tree is coming along nicely, I'm not even on my family yet! I've been filling out my partner's family info first since fewer individuals on his side have been added.

I'm still taking notes for when I'm finally prepared to venture down this new avenue of my family history. Until then, I won't forget that I promised some interesting peeks into my partner's familial history!

As they stay, stay tuned for more!

#genealogy#familyresearch#ancestry#familytree#genealogyblog#genealogyresearch#blogger#blog#family#ancestryblog#research#writer#familyhistory#twistingtree#twistingtreeancestry#discover#discovery#discoveries

0 notes

Text

Decades-Old Missing Person Mystery Solved After Relative Uploads DNA To GEDMatch

http://i.securitythinkingcap.com/T3Z8lZ

1 note

·

View note

Text

i got a myheritage test a year ago but i just now connected the data on GEDmatch (purely because i read that it could give you more information about your ancestry) and oh my god i can confirm i am Mediterranean to the BONE

#name a mediterranean country i guarantee i probably have it#this is so interesting to me like you have no idea#personal

1 note

·

View note