#he provides nothing new to the trope motivation he’s embodying

Text

I’m sorry I have to speak my truth lmao it’s a little bit hilarious that kingpin is stylistically offered such flourish and creativity, when writing wise he’s so fucking generic.

#another day ANOTHER POST OF ME BEING ANNOYED FUCKINGGGGG KINGPIN IS GIVEN ROOM TO BE A THREE DIMENSIONAL CHARACTER AND AARON GETS SUBTEXT#AND THE CHOICE BETWEEN NEBULOUS VILLAINY AND FAMILY HE LOVES#LIKE IM SORRY BUT EVEN W HALF THE EXPLORATION AARON IS MORE THAN TWICE AS INTERESTING AND YET WE HAVE LIKE. THREE SADMAN KINGPIN MOMENTS#IM SORRY SPIDERVERSE THIS IS THE ONE AREA I THINK WASNT THAT. INTERESTING. GIVEN HOW FRESH AND REVITALISED EVERYTHING ELSE FEELS#LIKE. COULD WE GET JUST A SMIDGE MORE INSIGHT INTO WHAT LED AARON HERE? SO WE KNOW WHAT HE GIVES UP FOR MILES?#LIKE IT WAS ALWAYS GOING TO BE MILES I *LOVE* THAT ITS MILES BUT ITS LIKE#DEVOID OF TENSION BECAUSE WE HAVE ONLY DEVELOPED THE DIMENSION OF AARON IN REGARDS TO HIS FAMILY#LIKE DID HE GET IN TOO DEEP WAS THIS A SECURITY THING HOW LONG HAS THIS BEEN HAPPENING WHERE THE PROWLER DOESNT BLINK AT BEING ASKED TO KILL#A CHILD#AGH#tunes talks critical#tunes talks spiderverse#I don’t even dislike kingpin lmao (I don’t rlly think anything of him beyond the fact I’m glad miles kicks his ass) I just think it’s almost#a bit of a waste that stylistically he’s interesting and fun to look at and watch be animated but writing wise he’s so generic#he provides nothing new to the trope motivation he’s embodying#the story his actions set into motion is interesting. the actual character is like. just stylistically interesting execution of a trope that#is just not that emotionally compelling for me. esp when nothing really NEW is being done w it

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persona 5 and how MBTI can expose writing (in)consistency

Disclaimer

We’re studying writing and narratology as self taught, we are passionate about narrative in general and we believe in MBTI as a tool to analyse things and frame both reality and fiction in a different way. These are our opinions on the matter of how MBTI can be useful in approaching plot and character consistency, but don’t take it as a scientific paper;

We’re writing this article after a good 3 runs and various hundred of hours spent in this game per mod. We’ve already analysed the whole main cast and tried to explore everyone of them more in depth, so please don’t take anything in this article as an attack to a certain character or the game as a whole. We love P5 and P5R wholeheartedly - for this reason, we can’t overlook problems when they arise;

Big huge enormous spoilers for both P5 and P5R.

Premise

Characters are the most important element of a story - yes, even more important than the plot. Especially if you consider that a plot is, basically, characters doing stuff to reach a goal. Lots of stories revolve around a particular event or atmosphere, a fictional world to explore, or an issue, but there will always be characters in them because, as human beings, we’re attracted to people, their flaws and their problems.

So, if characters are the basis of a story, going deeper we see how fictional works tell us about how and why people overcome hardships and become a better person in the process (tragedies surely exist, but they aren’t the norm). That’s what is called the transformation arc.

That being said, how do we use MBTI?

Since cognition is essential and behaviors mean nothing, we tend to look at characters both from a narrative and metanarrative standpoint. This means putting aside what characters do or what they like, and focusing on how they gain information, make decision and what are their motives. Since stories tell us about people and their struggles, it’s interesting to understand why characters act in a certain way, what really moves them forward.

This approach, inevitably, must compromise with the fact that fiction is made by people, and people can make mistakes. Works of fiction aren’t flawless and sometimes, trying to find what type a character is, is a way to bring light to those problems. Rules are a social construct, they’re fluid and constantly change, but they also provide useful tools to analyze stories, discovering their strength and their flaws. So, stories aren’t defined solely on strict rules, however MBTI can push one to better understand what is a good story or a well-written character and, vice-versa, why stories can fail to amaze us.

Why Persona 5?

Because it’s an excellent case study to show both how our typing process must adapt to face different situations, and what means to analyse a wide cast of characters that aren’t always perfectly written. The cast, though, is diverse enough that you can have characters with similar or opposite types that interact for 100+ hours, and this creates a very interesting setting for comparison and conflict.

Moreover, the confidant system can be a golden source MBTI-wise, because, if properly developed, a confidant can give us great insights about the character, or show other sides of them outside the main plot.

Tropes and typing

Persona 5 offers really great examples of what means to differentiate between typology and tropes when typing. Since we’re talking about fictional characters, we must acknowledge that sometimes there is a correlation between certain tropes/archetypes and certain types (mbtinotes on Tumblr talks about this more in depth here: https://mbti-notes.tumblr.com/spotting#fiction ). This, though, isn’t a rule and mustn’t become a limitation when typing, because cognitive functions work regardless of tropes, exactly as they do regardless of behaviors. P5 has both types that follow the tropes they are often associated with, and types that are completely different.

Ryuji is one of the main example belonging to the first case. He matches the Book dumb and Dumb blonde tropes, alongside with the Hot-blooded and Idiot hero ones. Those traits are usually linked to Se doms: always hungry and with lots of energy. In Ryuji’s case, though, he’s not an ESFP (only) because he’s loud and reckless, but also due to his approach to life and general cognitive process. That being said, it’s also true that he embodies the most common conception of what an ESFP looks like.

A similar example also applies to Akechi: he’s presented as the smart ace detective (The Ace) and later on as the mastermind traitor. He possesses many traits often linked to ENTJs, especially when they’re the villain, antagonist or anti-hero of the story. This doesn’t serve as a limit to his character though, and Akechi shares the majority of a young ENTJ’s cognitive process, alongside with some of its tropes.

On the other hand, P5 also offers characters belonging to the second case, for whom only looking at their tropes and role in the plot can be misleading typing-wise.

It's the case of Futaba: she’s an INFP according to our typing process, however the game always stresses her quirky and antisocial side, something so strong it defines her as a person even after her narrative arc. This is why many people type her as INTP, since those traits are often linked to Ti doms, high Ne users or rationalist types.

Another example is Yusuke: we typed him INTJ even though the community often refers to him as an ISFP. Our main complain regarding Yusuke as an ISFP is about how this type is justified only using the tropes he’s associated with. Since Yusuke is a bizarre artist and a weirdo, he must also be an ISFP in love with painting, art and beauty, right?

Well, this is true, but not because he’s an ISFP. His behaviors don’t stem from an ISFP cognition, rather from the one of an INTJ, in our opinion.

Narrative arcs

Narrative arcs define the plot, but (following a shonen structure) they also sadly tend to be too much stand alone in the game, especially when it comes to character development. This leads to a situation where characters shine in their narrative arc, but then just sit in the background for the rest of the game, as a part of the Phantom Thieves. This isn’t entirely a bad thing, since Persona 5 revolves around a large cast of characters and tends to focus more on the group as a whole, so this structure suits the game’s leitmotif appropriately. However, narrative arcs surely enhance what we said about tropes and stereotypes, not always in a good way.

There’s also the problem of characters following the plot/comic gags instead of the opposite. A story may undoubtedly be full of gags and fanservice without it compromising its characters and their purpose inside the narration, but problems arise when said characters must adhere to rules set by the plot, rather than being realistic people freely taking actions and making mistakes.

More specifically, we’re referring to:

Ann and harassment

This, in our opinion, is the most emblematic case about narrative arcs and how they tend to be isolated from the rest of the game. Ann’s arc doesn’t revolve around a big issue, differently from others later on where the Phantom Thieves face threats against the entire Japan. However, Kamoshida feels like a real villain and the pain inflicted to his students isn’t less relevant than other issues. The firs arc tells us a story about harassment, how it may lead to victim blaming, social exclusion and extreme actions like Shiho’s attempted suicide. So, the game surely starts with a realist and captivating take, but what lies after it? Sadly, not much. From that moment on, Ann still remains the most sexualised member of the group and is often the one whose body is used as a tool to gain intel or other useful things - Yusuke’s modeling affair and the second letter of recommendation on Shido’s ship are just two blatant example.

And while Ryuji’s confidant is simple and straightforward yet still works properly, Ann’s one can be dull, revolving around characters less interesting and engaging than the ones we see during Kamoshida’s arc. Moreover, her confidant takes place while Shiho is still recovering, so we see her mentioned only few times.

Makoto and duty

Every awakening in Persona 5 is thrilling and moving but, speaking for us mods, we think that Makoto has one of the most galvanizing. Her arc embraces the leitmotif of rebellion and it works even better than the others since she always appears as a diligent and polite student. But is there something more after her awakening? Sadly, as we saw for Ann, the answer is no. Makoto’s confidant is plain, a simple solution placed by developers to show her personality while introducing new characters. It works, but it doesn’t give a further twist to the premise the game showed during her awakening. Not to mention that, despite her decision to less blindly follow the rules, Makoto is often relegated to the mom friend/dutiful student role, reminding others of rules and schoolwork and stuff. Yes, she has a relevant role in Sae’s arc, but we still find her confidant lacking what is shown during Kaneshiro’s arc.

Futaba and self growth

Futaba’s arc is interesting on many levels, especially because we see how a hikikomori undergoing severe traumas can overcome them, thus becoming a healthier person. Even though her arc is one of the most emotional in the game, Futaba quickly resets to a stage where she’s more of a comic relief than a vivid character and she often kicks in just to mock the other thieves or to solve problems tied to computer science and technology. Yes, this is coherent to her character, at the same time it often closes her in stereotypes since Futaba is limited by those roles rather than showing her new and mature side.

Kasumi and Sumire and the lack of closure

Sumire’s arc and confidant deal with finding acceptance and a new balance between her old and new self, since Sumire slowly accepts her sister’s death. Or, at least, this is what the game tries to convey to the players. We love what Persona 5 Royal added to the main game and we played both versions for hundred of hours, however we must admit how both of us mods found lack of proper character development throughout Sumire’s confidant. Her arc does a great job in showing how much pain she had to endure and how she begins to live with her sister’s death. But at the same time her confidant doesn’t give her a new starting point, in our opinion. Why? Because reaching rank ten with Sumire means that she just finds a new way to be tied to Kasumi, and not in a completely healthy way. Sumire admits how gymnastic was a way to be together with her sister and how she loved accessory activities tied to the sport, like eating ice cream after training, more than the sport itself. So, Sumire never really cared about the competitive side of gymnastic and, at the end of her confidant, it seems like she sticks with it just as a way to be tied to Kasumi again. Yes, this is surely a healthier way than the one she took with Maruki’s help, and we know how our opinion regarding Sumire can be controversial, at the same time we don’t think her confidant truly ends her arc properly.

What has typing every character highlighted?

After 3 playthroughs, two platinum trophies and many hours spent discussing this group of punks, we used MBTI to give a structure to our articles and, unexpectedly, we often had to slightly change our approach in typing the main cast. It’s been a huge project of analysis, research, reading online discussions and further learning. In the end, we’d like to write down our own conclusion about these characters. This specific section might be a bit more about our personal opinions, though.

Protagonist (ENFP)

Typing the protagonist was the wildest part of this project. Since he’s mostly an avatar controlled by the player, we knew everything had to be taken with a grain of salt. We separated canon from player’s choices, as a way to find what makes the protagonist a real character (sadly, not as much as he would have deserved). We also tried not to rely too much on gameplay mechanics in typing. In the end, we progressed by process of elimination, discarding the option that surely didn’t fit.

We agreed on ENFP for him, but ENTP isn’t a bad match either. Even if a character so malleable by the player can’t be associated to a single type so easily, we do believe that a starting point somehow exists. Our hope for the future is that in new games we’ll get to play a real character, though.

Morgana (ESTJ)

Morgana was pretty hard to type, especially regarding the perceiving axis - which is a pity, because he’s not the stock ESTJ type of character. But since he’s the mascot of the Phantom Thieves, Morgana is often even more stereotyped than the other characters. He decently shows his dominant function during the game, but way less his auxiliary and tertiary ones, since his personality gets subdued by his function as the sidekick of the protagonist.

Ryuji (ESFP)

We talked above how tropes aren’t always detrimental and Ryuji is the perfect example of this concept. He was the easiest character to type, due to his simple (yet defined) personality. Ryuji demonstrates how a character doesn’t have to be complex or multifaceted to be interesting and loveable.

Ann (ESFJ)

Ann is the opposite case of Ryuji: a character driven by plot rather than by being a vivid person. We aren’t saying we dislike Ann (honestly there isn’t a thief we properly dislike), but we must admit how typing her was really difficult, and not because she’s too complex. It’s safe to assume she’s a Fe dom, however the game doesn’t give any solid clue about her perceiving axis - we traced down Si only by elimination and because her confidant show a clear FeNe loop, but otherwise the game offers nearly no clue of her Si (or Ti). Ann’s personality can’t shine properly in a game where, outside her narrative arc, she often has to follow the role of the ‘attractive/supportive character’ assigned to her.

Yusuke (INTJ)

Yusuke is an interesting case: typing him wasn’t easy, but, contrary to Ann, just because he’s more complex than he may appear. Under the ‘artist’ trope (that misled the majority of the community towards ISFP) there’s a character with less predictable sides and a well-written arc. Also, a very nice example of a non-textbook INTJ, since these types are often associated with science and/or greater battles in life. Yusuke was a nice surprise to find.

Makoto (ISTJ)

Typing Makoto was a bit of a slow process, since there isn’t a popular type assigned to her by the community. At the same time, identifying her cognitive functions wasn’t too hard, so we can at least say she’s a relatively solid character, meaning that even if she’s mostly a textbook ISTJ, she still shows the development process of her inferior Ne and tertiary Fi in her confidant. Her growth is pretty linear, and the problem lies precisely in the lack of a proper twist in her personality, since she could have been far more interesting and less predictable.

Futaba (INFP)

Futaba was hands down the hardest character to type, since she’s tied to all the stereotypes of being quirky, asocial and nerd, usually associated with INTPs. Futaba perfectly shows how a theoretically well-written character can’t shine under specific circumstances: she has an emotional and complex arc, which was in fact our starting point in typing her, since it’s a pretty clear example of a FiSi loop. Yet, she acts more as a comic relief or as a source to solve IT-related problems, and her functions aren’t properly shown.

Haru (INFJ)

Despite the meme of Atlus hating her and not giving her the proper screen time (which isn’t untrue), Haru was pretty easy to type. She’s a nice example of how a character doesn’t have to follow his type’s tropes to feel real. Haru isn’t the typical daydreaming INFJ with a saviour complex, and in fact she gets sometimes mistyped as INFP. Unluckily, as for Ann, the game doesn’t do a good job in giving her a well-rounded personality, and in fact finding evidences of her third and fourth functions was pretty hard.

Goro (ENTJ)

Akechi is probably the most multifaceted and complex character in the game, at least in P5 vanilla - we believe Maruki lowkey stole that record in Royal. However, since he’s a well-written one (even if he still lacks a proper narrative arc, to a certain extent), Akechi wasn’t hard to type. The most interesting thing is that he may seem the classic ENTJ with a psychopath/killer personality, but in reality, he probably doesn’t suffer from any mental illness, and his character revolves around what happens when functions are used unhealthily, or are excessively underdeveloped. For this exact reason, though, we find a pity that the game doesn’t properly address the consequences and aftermath of a teen that had to commit severe crimes and murder people to find a place in life.

Kasumi (ENFP) and Sumire (ISFJ)

There’s a lot to say about Kasumi and Sumire, especially regarding their role in the plot and their confidants. Typing them wasn’t easy, since we only see Kasumi through Sumire’s actions, and both of them have a half-confidant instead of a proper one each. So, with both sisters we had to proceed a bit by process of elimination, since they appear for a relatively short time and without super strong evidences of their types despite a few functions. Sadly, they highlighted how writing characters for plot’s sake rather than by making them vivid may lead to incomplete narrative arcs.

We’ve come to the end of this article. Thank you for reading!

This officially concludes our journey with the P5 main cast - it’s been a wonderful experience to learn more about both MBTI and the characters of the game we loved so much. If you want to discuss things with us, we’ll gladly listen. You can reach out here on Tumblr in comments, asks and dms, as well as on Instagram.

(And, if you’re interested, we’ve also wrote about Maruki, Sojiro and Tae).

#mbtiofwhys#mbti#personalitytypes#typology#blogging#stereotypes#clichés#video games#fiction#fictionalworks#persona 5#persona 5 royal#p5#p5r#narrative#writing#fictional characters

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Girl’s Gotta Have Guts

Arakawa once said that a great manga artist is “someone who can find the perfect balance between complying with readers’ expectations and betraying said expectations.” Arakawa seems to employ this philosophy in her own work to challenge her audience’s expectations about gender.

While her stories employ some gender tropes that are commonly present in shonen manga, action stories, and coming-of-age stories with male main characters, she also (whether consciously or not) confronts quite a few clichés and tears them apart with her narrative. By doing this, she subtly encourages her readers, mainly young boys and girls, to challenge the stereotypes about women that they see in other fiction or even in real life.

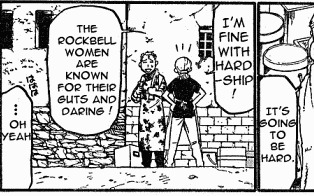

Arakawa once stated, “Our family motto is ‘those who don’t work, don’t deserve to eat.’ Everyone has to work hard to make ends meet, including women and kids. That’s the reason there are so many working women in Fullmetal.”

She points directly to Winry and Pinako Rockbell from Fullmetal as an example of this. The grandmother and granddaughter are skilled mechanics who run their own automail business, which the main character of Fullmetal depends upon. Since Winry builds and provides maintenance for Ed’s limbs, Ed owes his mobility and ability to do alchemy to her. The mechanic profession is shown to be male-dominated in Fullmetal, like it currently is in real life, yet Winry thrives in her career and is incredibly accomplished. She even strikes out on her own at age 15 to establish herself in a busier area and have a wider range of customers.

Winry is a tough mechanic but also a very nurturing, emotional person. She’s shown to enjoy baking and be domestically skilled. Since Winry has medical know-how and puts Ed’s limbs back together when they break, in some ways she is in the traditional “civilian healer” role women tend to occupy in action stories. But the work Winry does as a healer is shown to be just as impressive and important as the daring deeds that Ed and Al do, and perhaps even more admirable.

A huge theme of Fullmetal Alchemist is the power to create versus the power to destroy, and as someone who builds new limbs for people, Winry is the embodiment of the former. Winry’s “traditionally feminine” work as a healer is shown to require just as much grit as anything Ed does. A scene where she prepares to deliver a baby in the 2009 Fullmetal anime is accompanied by epic fighting music to underscore this point.

Ed often admires Winry’s skill and ability to save lives. He notes she is able to do what he with his alchemy can’t—bring human life into the world. In many ways, Winry is our protagonist’s hero. She is what he aspires to be—a human who creates rather than an alchemist who destroys. Through Winry, Arakawa challenges the idea that women who aren’t action heroes have less value than those who are.

Giving the Civilian Female Character Her Due:

Everyone’s probably familiar with the trope—the superhero’s girlfriend or female relative provides endless support, yet the protagonists don’t ever have to consider her problems. She exists for them, and her life outside them is not of consequence. Not only that, the protagonists don’t see fit to tell her their secret identities, what they’re doing, or even let her in on things that directly affect her (like the threat of villians coming for her). And all for her “protection.” Arakawa presents a similar situation, with the boys depending on Winry but keeping things from her, but then smashes it apart by showing the consequences of treating someone this way. Winry is vocally upset about the boys leaving her out. A huge part of Ed and Al’s character arcs are about how they need to realize that shutting Winry out “for her own good” is hurtful and disrespectful.

Moreover, it is fully acknowledged that Winry has her own problems to deal with—she struggles with her identity and finding the right path to take in dealing with the loss of her parents. Arakawa makes a point that because of this, Winry can’t just function as constant emotional support without getting any from the boys in return. Arakawa takes great pains to show that while Ed and Al are a big part of Winry’s life, she has a fulfilling existence outside of them. The fact that Winry has her own career, acheivements, and a community that depends on her is what keeps her going.

Essentially, Winry is the hero of her own story. Through Winry, Arakawa encourages her male readers to be more respectful of the women in their lives. She also encourages her readers not to see women as an endless source of emotional healing and support, but as complex people with their own lives and goals who also require support at times.

Promoting the Importance of Emotion and Communication:

Arakawa’s work challenges another common cliché: the idea that it is better not discuss your feelings and that “real men” don’t show emotion. Early on in Fullmetal, a male character tells Winry that the reason Ed and Al don’t talk about their feelings is that “men speak with their actions” and “hide their pain so as not to burden their loved ones.”

However, Winry proves that her way of handling things—by actually communicating her feelings—works a lot better than that macho nonsense. She ends up resolving a conflict with communication. She informs the male character that sometimes you do need to communicate with words, and he agrees with her. Arakawa explicitly shows that the more “feminine” method of being open about your feelings actually gets things done, and that burying your feelings hurts your loved ones more. This is a really good lesson for young people to learn, especially boys, who are often taught to be ashamed of their emotions.

Challenging the Damsel in Distress and Lack of Female Agency:

The “damsel in distress” trope is incredibly common in action stories, especially ones with a male protagonist. A female character close to the hero will be put in peril in order to motivate him. The villain in the story often does this knowingly, seeing the woman in question as nothing but an object to use as leverage against the hero. The narrative will often back the villain up in this—the female character may protest or fight, but ultimately she will fulfill her function as a motivation for the hero. Arakawa encourages her readers to question this particular trope by putting it in play and then tearing it apart. In Fullmetal, the villains threatens the women close to two male protagonists—Winry is threatened to force Ed and Al’s hand, and Riza is threatened to force the hand of her partner Roy Mustang.

However, not only do both women engineer their escapes, they turn the hostage situation to their advantage and save others. It initially looks like Winry has been kidnapped by another faction, only for it to be revealed this was a clever trick Winry engineered to fool her captors and allow her allies to escape. Winry recognizes that her captors see her as a victim without agency and turns this into their downfall. Arakawa even frames the narrative in a way that forces the reader to feel foolish for assuming Winry was helpless. Riza, on the other hand, uses her position as a hostage to gather intel for the resistance.

The most important thing about these situations is the female characters are ultimately put in peril to further their stories more than those of the male characters. Winry’s hostage situation is largely a device to bring her into a confrontation with her parents’ killer, and her story takes center stage during this confrontation, with Ed and Al acting as her support.

Moreover, in taking control of the situation, Winry is finally able to confront her fear of being a burden to her loved ones, resolve her issues with feeling helpless, and even figure out her identity. It also shows Ed’s positive development in that he doesn’t prevent Winry from making her own choices out of a desire to “protect” her.

Source: https://www.themarysue.com/hiromu-arakawa-part-three-women/

#Winry Rockbell#winry protection squad#edward elric#Alphonse Elric#Fullmetal Alchemist#hiromu arakawa#manga#fma

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE review

I said I would give my impressions on #FE and I neglected to do so till now, but better late than never.

I’ll be talking about:

Story

Setting/Theme

Characters

Gameplay

1. Story

The story is nothing special - I enjoyed it, but it's a fairly typical jrpg "power of friendship and bonds" deal that is only made unique in any capacity by the idol culture that frames it. It's not bad, but it's not groundbreaking either. I wish the story were a bit longer to give more of a build up into the final confrontation. The earlier stages slowly start to set things up but even just one more dedicated chapter to ease into the final arc would have probably made the ending feel less rushed. That and I just enjoyed playing it overall and would liked more content.

The distinct chapters format to the flow may have been meant to simulate FE chapters while still also representing how persona stories often have noticeable breaks between dungeon arcs. In TMS though, it felt a bit more artificial, not damningly so, but I think the plot momentum was a bit worse for it.

The set up for each chapter break also revolves around Itsuki himself improving as an entertainer, even though he doesn’t know what direction he wants to focus on, and while it’s most emphasized early on, this aspect of Itsuki’s development himself feels almost abandoned or ignored through the mid and late game until the very end. The solution does make some sense, but some of the details that enable it to happen are a bit questionably contrived, and like the overall story, it felt a bit rushed in the final hour, based on what I remember.

Otherwise, the story did a good job of setting itself up, providing the characters with adequate motivation and means to seek the goals they set and each dungeon gave reasonable purpose for the main characters to tackle it.

The final chapter seemed to be trying to make up for the lack of build up by twisting and turning a bit more than usual, but most of its attempted twists were fairly standard fair for trying to draw out suspense and unfortunately were somewhat predictable for it. I was a little surprised at the host for the big bad, but mostly because I hadn’t been paying close enough attention so that was on me.

2. Setting/Theme

The Tokyo idol scene setting is the most interesting aspect of the story and while I can see it being polarizing, I found it novel myself. Mechanically, it does a good job of unifying the dungeons under a common theme of "things idols do" - such as posing for photo shoots or acting on TV.

Beyond dungeon design, the idol theme also naturally informed character designs and the multitude of costumes that appear throughout.

You can even see this thematic flair in the way that spell casting involves a character signing their autograph as a glyph!

If there’s one oddity that stands out to me about the aesthetics of the game, it’s that the monster designs seem to be unable to decide whether they should be FE inspired or SMT inspired or neither, but even in the latter case most don’t seem to fit in with the idol theme in any capacity.

Even when enemies are FE inspired, they seem to have gone through a similar (if not more extreme) filter that the Mirage characters went through - becoming dramatically stylized and the only real purpose I can conceive for it is to make enemy classes that were definitely human in FE appear non-human here. For instance, the middle and right monsters above are myrmidon class enemies - unpromoted swordmasters from the FE universe.

Not to mention: Why do their out-of-combat sprites look like Organization XIII members!?

3. Characters

Like the story, the characters are good if nothing particularly revolutionary. Most seem built around one or two tropes but then are fleshed out beyond that which is fine. You learn more about them as you do their individual side quests (social links) and these do a good job of giving the feeling of evolving your bond with that character. The pacing of the side stories is mostly okay, though the gameplay reward for those that are plot locked to be very late doesn't always feel equal to how long you had to wait to do them. There's a bit of persona syndrome wherein all the chars get plenty of opportunities to interact with the MC, but would benefit from more time interacting with each other as well.

I liked all the characters in the end. There's a good variety between both the girls and boys, though because of join times some chars got more focused screen time than others. Again, I think a longer late game with more story side quests (instead of fetch quests) would have helped balance things out.

If I had to be as base as to rank the girls in terms of waifu ratings:

1. Eleonora

2. Tsubasa

3. Kiria

4. Maiko

5. Mamori = Tiki

Though it's worth noting that top four are all really close, and each slot only wins out over their competition by a small margin. I don’t dislike Mamori or Tiki, I just am not into the little sister appeal.

I suppose Barry Goodman is worth mentioning as well. Barry is a foreigner who settled in Japan and behaviorally embodies the most cringe-worthy aspects of otaku culture. He’s heavy-set, roughly groomed, and somewhat aggressive/abrasive about his passions. I’m not one to judge him for the subject of his passions, but the way he interacts with them would make me uncomfortable around him had he been a real person. Ultimately he is a good person at heart, but his poor people skills are unlikely to endear him to anyone on first impressions, and the fact that he doesn’t care only exacerbates his problems.

Finally, and predictably most disappointingly, the FE chars (heroes and villains) are barely developed and could be replaced with persona or persona like motifs without changing the overall plot. The FE aspect is little more than a coat of paint that gives secondary theme to the invading 'otherworld,' and it's a real shame and waste of potential.

Aside from the Mirage characters and Tiki themselves, there are however a few unmarked references that are at least self aware enough to be welcome Easter eggs for fire emblem fans:

Anna is your convenience store shopkeeper, and there’s even a ‘shadow anna’ who will sell you more dubious dungeon consumables that a normal convenience store wouldn’t stock.

Ilyana works at the cafe, keeping close to her beloved food.

Aimee runs the jewelry store as she was the item store merchant in FE9 and 10

And Cath runs the costume shop. She’s a thief in FE6 with a distinct affinity for money, not unlike Anna, though not as extreme either. Admittedly, it’s been a while since I’ve read over her supports though.

I saw an npc employee at one of the random background shops in Shibuya central street that could also be Brady from FE Awakening, but the camera never got close enough to see him clearly enough to make a positive ID.

Finally, I found it amusing that all the playable chars' names are class puns/references

蒼井樹 = Aoi Itsuki > Aoi means blue in reference to FE lords typically having blue hair

織部つばさ = Oribe Tsubasa > Tsubasa in reference to her peg knight class

赤城���馬 = Akagi Touma > 赤 (Aka) gives us “red” while 馬(uma) is “horse.” Red cavalier (partnered with a green cavalier) is a reoccurring archetype in FE. The Red cav tends to be the hot-headed one.

I can break down the others if desired, but these will do for examples.

4. Gameplay

Going to break this into a few parts:

General

Combat

Dungeons

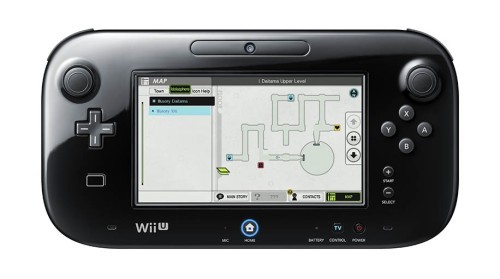

1. General

The real reason this game is compared to Persona; gameplay mirrors a lot of persona's elements and it's almost easier to describe how it deviates from the Persona format than spend time detailing how they're the same. That said, if you like the persona formula (as I do), you'd probably enjoy TMS's gameplay flow as well.

While the lack of daily life and day limits for dungeons removes a lot of the tension of time management for them, I think it's fine since a lot of persona players rush dungeons in 1-2 days anyway and in TMS, once the dungeon is done, you don't have to worry about doing busy work to tick off the days until the plot is allowed to move forward again. The lack of social stats is an element of depth removed, but without a time cost element to activities, it makes sense and is probably a good thing for it to be absent from TMS (even if story wise it could have actually be viable as Aoi and the others grow their skills as performers).

Using the WiiU game pad as a smartphone screen to facilitate off-screen character interactions as well as display more detailed enemy information was clever if perhaps unnecessary (as persona 5 showed). Having the only map on the game pad actually made it a little disorienting to reference for me since my eyes had to leave my tv entirely, leading to me either holding my game pad up or bobbing my head up and down to compare my map with my surroundings. On the DS, the two screens are at least close by. I’d like to say there may have been a better use for the game pad, I’m not thinking of anything off the top of my head, so it may have been wise to minimize its use as a gimmick anyway.

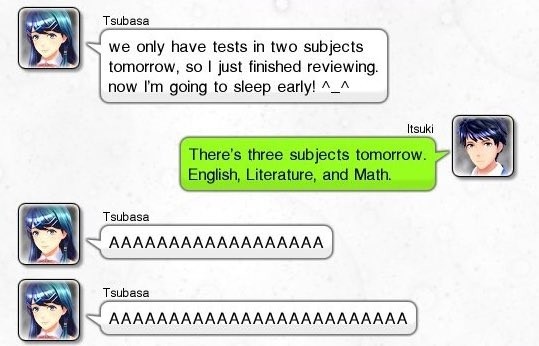

This is already in your phone history when you start the game, but it’s still probably my favorite moment from the text message logs:

#relatable.

Replacing persona fusion is a more straightforward crafting system that is the source for your weapons and passive skills, and in turn, much like Tales of Vesperia, your weapons are the source of your skills, both active and passive. The system sounds more grindy than it is in practice though. Simply advancing through the dungeons and fighting 70-80% of the monsters you encounter naturally will provide you with enough materials to forge most weapons as they become available. In fact there were a number of times when I ran out of new weapons to forge and had to push on with already mastered weapons equipped. I liked that bosses and some savage encounters would drop mats of a higher tier than what was readily available from current monsters, and you had to spend them wisely before advancing the plot to the point where those mats became common. It let you preview the next tier of weapons and abilities for select characters but who you gave those weapons to was never overly stressful since you could get the other weapons you passed on later anyway.

Rare monsters drop unique mats that can make weapons that give unusual or otherwise off-type skills to characters and it makes catching rare monsters that flee rather than engage the player rewarding. IIRC, I encountered fewer than ten rare monsters in my entire play through though, so I did not feel it worth the time to actively hunt them unless there was some trick to make them appear more reliably (and catching them was also a bit dependent on the surroundings). Like treasure monsters in P5, they usually had some kind of gimmick where they were only weak to one thing if they had any weakness and the latter ones also came with dodge [weakness] passive and had a chance of just up and running from battle.

2. Combat

The one-more mechanic is replaced by "Sessions" which are not unlike self contained one-more combos anyway. The tag in attacking animations were pretty fun and though late game sessions can get quite long, there’s no way to speed up or skip session animations, possibly in part because of the existence of duo arts which use the session animations as a timer. They could have prohibited skipping prior to deciding on a duo art and then allow skipping or speed up after, though. Long session animations didn’t bother me, personally though, as session attack animations were varied and interesting enough that I never got tired of even the early basic ones (most of which were replaced by late game).

Openly displayed turn order, plus some late game skills that can actually influence turn order were both welcome features as well.

Beyond sessions, specials, duo arts, and ad-lib performances were great at providing extra variety and changing the pace of what might otherwise be rote combat. While duo arts and ad-lib performances were rng bonuses that you mostly just take whatever you can get and be grateful, specials were more deliberate, needing a resource that builds slowly at first. Later on, with longer sessions and meter boosting passives, the sp gauge builds up much faster, but even then specials usually should be selected carefully, especially within boss battles where recovering lost sp is a bit trickier.

That said, special skills were not created equal. Even though buffs and debuffs are powerful, some of the later buffing and debuffing specials came late, at a point where I already had normal skills that could buff or debuff at almost if not the same potency without spending SP. Similarly, as my repertoire of skills grew, my ability to hit weaknesses improved and using specials to break through resistances became less necessary, even as monsters began appearing with more resistances.

Finally, Itsuki’s second special - “Strike A Pose,” was absurdly good and only got better as my session combos grew longer late game. The ability to give everyone twice the actions in a turn opens up so many other combos that often times, there was little reason to use offensive specials in favor of either two individual sessions or a concentrate/charge boosted session.

Inversely, I found myself using healing specials a lot less, and perhaps it was because I used Tsubasa a lot less late game - I made Chrom a great lord which gave Itsuki healing and support which was kinda Tsubasa’s niche previously, so with Touma able to out damage Tsubasa and Elly covering flying enemies, Tsubasa just wasn’t out in combat all that often, which meant Mamori was the only one with healing specials (which were helpful on occasion) but in the end using Strike A Pose allowed me to get normal heals out in extra abundance while still enabling attackers to make a play to help clear troublesome enemies.

The FE weapon triangle’s representation in strengths and weaknesses among weapon types (not extending to magic though) gave a welcome way to predict weaknesses for enemies I had not encountered yet. One of the frustrating things about persona had always been that weakness/strength attributes for new monsters were difficult to predict and late game could cause you to walk into a bad situation that was never really your fault. Not only did the weapon triangle help mitigate some of the arbitrary mystery, but weaknesses were frequently consistent across similar enemy types at different levels even outside of the sword/lance/axe trinity. For example mage type enemies were, with few exceptions, all weak to swords and fire. Skills that deal effective damage (i.e. horseslayer/armorslayer) were also a great addition that gave characters tools to start session combos on enemies that they might otherwise be powerless against. The player also gets other ways to work around pesky resistances, features that are both welcome and necessary because...

If I have one glaring critic of the battle system it’s that Itsuki, like persona protags is mandatory. However, unlike persona protags, Itsuki has static combat tools and extremely limited ability to influence his own strength and weakness attributes. He’s always weak to fire and lances and since you can’t remove him from the front line, you always have someone in combat weak to those elements. Fortunately this is less deal breaking for the fact that Itsuki dying in combat doesn’t immediately game over (hallelujah!). In addition, later in the game most chars get passive skills that greatly increase their avoid against elements they’re weak to, Itsuki included. Still, being able to remove Itsuki from the front line would greatly increase your party diversity and flexibility. For a while after recruiting a second sword character, I had difficulty justifying putting him in the active party because Itsuki already filled the sword role. Eventually, I promoted Itsuki to a more support role and let the other char handle offensive sword plays.

One more minor complaint I have is the inability to swap out fallen allies. Having only three party members means that even one of them dying can be crippling, especially later on and on harder difficulties. I’ve wasted turns reviving downed allies and trying to heal back only for enemies to just repeat what killed someone in the first place and put me exactly where I was last turn with less healing items or sometimes in an even worse situation. While the boss dichotomy of easy/impossible with little in between that some persona bosses suffer from is present here, the existence of specials, ad-lib performances and duo performances that heal or revive greatly alleviate some of the comeback struggle that has a tendency to snowball in this combat system. As the only active non-rng option, specials in particular are important to the system. The severity of boss gimmicks isn’t quite as punishing in TMS compared to persona, but TMS’s smaller party size, can still cause a bad situation to cascade into unsalvageable territory.

3. Dungeons

The dungeon design of TMS is interesting in that it departs from persona 3/4′s formula of randomly generated floors in favor of deliberately organized floor plans with usually only one correct path to the end. The linearity is sometimes broken up by treasures that you’ll have to backtrack for, but aside from that, there’s little mandatory backtracking within a dungeon. Dungeons stick around even after you clear them, allowing side stories to ask you to venture back over familiar ground for one task or another.

That said, the linear nature isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In TMS’s case, it allows the developers to give the player a learning curve for the dungeon’s mechanics and then challenge how well the player understood the earlier lessons, because the devs can guarantee that the player experienced the earlier sections before the later ones. It may sound obvious on paper, but it means that the developers can have a better awareness of the player’s competency at any given point in any dungeon, which is something that can’t be tracked when the player can go multiple routes at any given time. But I digress.

Another mechanical difference of note is how the player, Itsuki interacts with enemies pre-battle. In persona 3 and later, you could swing your weapon to hit an enemy in the field and that would start combat (at an advantage if they didn’t notice you), but in TMS, striking an opponent on the field knocks them back and stuns them, giving you the choice to then get closer and touch them to begin combat at an advantage or to avoid combat entirely. I like this greater degree of choice and it fits within the philosophy that TMS dungeons are made to be less stressful - less about meticulous resource management - than persona games. There’s still an incentive to engage in combat: you need to keep up a certain amount of level growth just to have the raw stats to beat bosses, but if you’re low on health and/or healing items or just plain short on available play time and you think or know there’s a checkpoint up ahead so you just want to make a push to reach it, you aren’t forced into battles you don’t want to engage in... with the exception of “Savage Encounters,” which are challenge monsters that seem to just exist to screw with you anyway. I think there was only one area prior to the last or second to last dungeons that had savage enemies I could actually beat albeit with great effort.

Playing TMS after Persona 5, it was also apparent that TMS’s idolaspheres were prototype palaces, from the set floor layouts and linear progression to the overarching themes of the dungeon informing its aesthetic and unique mechanics. In fact there are a number of things that TMS pinoeered for Atlus that then went on to feature in P5. You can read about some others here.

Puzzles were almost entirely navigation in nature - that is, how to use the dungeon mechanics and infrastructure to get from your start to your goal. It may be because it’s been a little over a month now, but none particularly stand out in my memory as being exceptionally good, while one or two I remember for being somewhat arduous or tiring. I’m still of the opinion that areas that the player is trying to solve puzzles in should have lower if not 0 encounter rate with random enemies, as battles, especially turn based ones that don’t tend to resolve in a single turn, can disrupt problem solving trains of thought.

Overall the dungeons are good though, and that’s important as they’re the meat of the gameplay. They are generally well paced with plenty to do and some minor stuff to find on your way to your target goal. Each dungeon’s unique mechanics fit with the dungeon theme and aside from a few exceptions the enemies are fairly distributed.

5. Conclusion

It has its flaws but I think, in the end, Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE gets more right than it gets wrong. Even though the story was standard fair for this genre, I thoroughly enjoyed it and wished it had more content to its core for me to experience. I know there’s dlc, but the nature of dlc means that it’s nothing integral to the story and I’m not sure it would scratch the itch the way I want.

The setting is unique and the game fully embraces the themes it sets up and the themes in turn inform and affect almost every aspect of the game, giving it a unified appeal.

The combat is arguably more interesting than persona. It takes the same core formula of targeting weak points for massive damage but allows players more tools and freedom to circumvent bad matchups, make carefully planned strategic plays, or simply style on enemies with flashy satisfying attacks.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Analysis on A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Bad Beginning.

Once upon a time, I wrote a small letter to Lemony Snicket at the height of the popularity of A Series of Unfortunate Events books, fueled by my own anticipation of the book coming on October of 2006, appropriately on Friday the Thirteenth. Just a few days afterwards, I received a response from him via a post card. Even now; it was one of my most precious memories when I received the post card. It was one of those mass printed post cards that the publishing house would send. It was a very fascinating dead eye moment in my childhood.

What was even better was that the poem itself was an Acrostic, a word which here means a constrained writing form in poetry where the first letter, syllable, or word of each line is used to spell a word, message, or even the alphabet. I was ecstatic when I read through and only I could see “Olaf is near,” and could only mentally prepare myself for the imaginary battle of good versus evil against the filthy and greedy Count Olaf.

But, that’s not what I remember most of all. As I look at it now, I still remember the post script in the upper left-hand corner which writes, “P.S. You’re a great writer, Johan!” Now, a part of me suspects that it was written by a writer’s assistant, but the child in me desired it to be his own hand, written in ink and in casual capital letters. Until I meet him, I wouldn’t know. And I don’t know if I want to meet him.

Now and again, I pull down my copy of the Beatrice Letters and pull out the post card to look at it and remember the moment of my dreams being set into an orchestral piece with a full chorus of opera singers rising in my head. Truly, that was one of the pivotal moments that set me down the path of becoming a writer, studying creative writing in college and writing my own pieces from time to time.

Lemony Snicket, the moniker of Daniel Handler, was one of my heroes as a child. Which is why I am making I’m writing this piece as a retrospective of the Series of Unfortunate Events. With the new release of the Netflix series making what I feel to be the most genuine interpretation of Handler’s world of Victorian gothic mixed with some darkly comedic moments within its pages of absurdism, it is a true departure from what the Nickelodeon movie had done with its rushed collaboration of the first three books slammed into each other like some Cronenbergian monster with the semi-retired actor Jim Carrey at its helm. I want to revisit the books and see how they stand as their own entities. I will take the books a few paragraphs at a time, not summarizing their own plots but acknowledging what Handler does to keep his audience tearing through the pages to the end, as I did long ago.

The Bad Beginning is the entry point into the series, and from the start it sets the tone of the whole thirteen book franchise. We are brought into the world of the Baudelaire orphans: Violet, Klaus, and Sunny. Each one of the children are experts in their fields; Violet is a mechanical and engineering prodigy, Klaus is an avid reader who remembers everything that he reads, and Sunny has very sharp teeth that could bite into anything. These three tropes Handler uses are practical in their descriptions and gives an excellent canvas for growth in later novels. One important trope to mention in the books’ execution is the way Handler, portraying as Snicket, brings the tone of the books in a melancholy perspective of journalism and storytelling. He even states on the back of the book, “It is my sad duty to write down these unpleasant tales, but there is nothing stopping you from putting this book down at once and reading something happy, if you prefer that sort of thing.”

What you will expect out of these stories is a recurring theme of obliviousness in the adults, no matter how well intentioned or poorly mannered they are. Mr. Poe, the Beaudelaire’s handler of their parent’s fortune and for Orphan Affairs at Multuary Money Management, is the embodiment of this philosophy. Handler plays around with the adults and gives them proper motivations and characteristics that make all of them memorable. In the first book of the series, we are introduced to the three major adults, as well as accomplices, of the book; Mr. Poe, Justice Strauss, and the bane of the Baudelaire’s and main antagonist, Count Olaf.

I will say one thing about Count Olaf at his most basic form, without the disguises or the manipulation of adults in the time the Baudelaire’s lived with him; he is the embodiment of a perfect children’s villain. From the cover art and inserts by Brett Helquist to illustrate the dark aesthetic that the books sustain in its varying locales, the only steady attribute of Count Olaf’s treacherous and vile character. At his core, he is vile, greedy, demanding, and even bad smelling. There would be no Series of Unfortunate Events without the recurring schemes and creative use of horrific deception that he concocts, along with his accomplices. When we’re introduced to him in the Bad Beginning, the reader already despises and feels uncomfortable as Handler describes the state of his house, the tower, and the disgusting accommodations he provides instead of a healthy and safe home for three children- I am calling the Orphans ‘children’ because that’s what the adults call them- and makes them do tedious and horrifically boring chores while he openly talks about taking their fortune and using it for himself.

I have already said my piece on Mr. Poe- a character who I still despise as much as I enjoy a bowl of buttered popcorn; very much and with ferocity- but in the case of Justice Strauss, I find her to be the guardian who could have been. She’s a pleasant character and for the life of me I would ask why she would be next door neighbors to a vile villain such as Count Olaf, but at the same time, I believe it to be an excellent juxtaposition that Handler uses. Strauss and Olaf work just as well as representations of the whole series; there are good moments to oppose the reality of what the story is at its core. Take for example, the part when Olaf orders the Beaudelaires to cook dinner for him and his troupe. Instead of keeping a whole chapter of them wallowing in pity, Justice Strauss comes and helps them pick an easy dish for dinner; pasta puttenesca. The descriptions of the trip to the market and the shared explanation and sympathy from Justice Strauss makes the reader feel more comfortable and gives them a break from the main story, only to have them thrusted back into the terrible story- the word terrible is being used to describe the horror on one’s face when they continue to read the events in Count Olaf’s home and not to describe the way the book is written.

There is only one point where the good and bad mix- Count Olaf and Justice Strauss- and that is when Olaf recruits her as an unaware accomplice in his scheme to marry Violet for the Beaudelaire fortune. This is another common theme that the series delves into; good and intelligent people can do bad things if the phrasing is done right by bad and intelligent people, even if the good did have good intentions. In this case, Justice Strauss wanted to be on stage ever since she was a little girl, and Olaf took advantage of that to make the illusion of “Al Funcoot’s, The Marvelous Marriage,” into a legally binding marriage through Olaf’s interpretation of in loco parentis. But, only through the only plot hole in this book did this not come to fruition- writing with someone’s not dominant hand equals it’s not legal? What?

Regardless, the first book of the series upon release in 1999, was a perfectly created story for children who were tired of reading stories that were cheerful and had a happy ending. In my personal words, it was about time to read a story that played with darker undertones, not to terrify its readers but to grip them. The inclusion of various single words with definitions, the engaging scenarios, and villains that people can identify immediately without having to go through many pages to realize that they are the bad guy makes The Bad Beginning a deeply disturbing yet equally thrilling middle childhood book for any child with a high enough reading level to understand and be enthralled by.

The Bad Beginning, a Series of Unfortunate Events: Book the First, by Lemony Snicket: 4/5

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claudia Toman - Hexendreimaldrei

I read Hexendreimaldrei, the first part of the Olivia Kenning trilogy from Austrian author Claudia Toman as part of my German reading challenge. The book was published by the Diana Verlag in 2009 and is only available in German. I have very mixed feelings about the book. It was a weird ride where moments of fun and intriguing details alternated with shock over the sexist generalisations, annoyance over poorly solved plot difficulties and eye rolling over the clumsily used plot device characters. The story doesn’t work for me because I could not emotionally connect with the Olivia, or understand her motivation for half of the things she does in this book. The narration gives you coincidence upon coincidence to solve the plot problems. The lack of foreshadowing removes the fun part from the detective/investigation quest: the guessing and dissecting the text if an offhand remark contains a clue. Spoilers after the text break. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- The things that I didn’t like (or annoyed me a lot): 1.The “this-all-was-just-a-dream” trope 2.The pop culture references that do not add value to the story. It already has a strong fairy tale and classic literary influence, heaping the pop culture references on top is an overkill and creates a cheapo gimmick-y effect. 3.The classic literary references work better, but I had the feeling they were just included randomly to fill the plot holes. It bothered me particularly in the last conflict scene with the main antagonist where Olivia defeats Lady Grey by citing from a Shakespeare play. 4.Explaining how a seemingly insurmountable problem can be easily solved by jumping back in time and explaining that a secondary character who is Olivia’s friend happens to be an expert in the field that is necessary to solve it. The readily available sodoku and literary expert friend? Randomly talking to the hotel receptionist who happens to be a Shakespeare specialist-slash-amateur-actor? Walking into the first esoteric shop and just telling a complete stranger something that a. sounds insane b. could get you in trouble with the organisation you are trying to infiltrate? Build these up first, often a few lines or comments in advance are enough. 5.The frequent jumps between the different timelines make the story difficult to follow. This is made even worse by the above-mentioned issue with jumping back in time to provide explanation that is needed in the present timeline. 6.The plot is based on the idea that a woman, on the wedding of the man she is love with makes a wish that surprisingly becomes true: the man is transformed into a frog. The fact that anyone in a such situation would wish exactly that is not plausible for me (Wish that he marries you instead? Wish that you are not in love with them?). I realise this is the “This is magic, silly!” moment where I should suspend my disbelief. I’m trying, I promise but it’s hard. 6. The protagonist is completely sure that the Pianist (or the Prince as the text often refers to him) is Mr Right for her based on the following three factors: • He has emerald green eyes • He composes and plays music that the heroine finds deeply touching • He is a foreigner and “frenchy” I find it alarming that Olivia becomes so quickly so obsessed with the Pianist because they barely speak a few words at all before she decides to marry him at the earliest possibility. I know this book is heavily influenced by different elements of the Princess and the Frog fairy tale but even so. At least give us a few scenes where we see them bonding. I can’t care about the relationship that is just built on a few sketch-like scenes from the Sex and the City and sweeping generalisations. It made me sad that Olivia went through so much pain to please the Pianist and it’s clear the aside from being physically attracted to him, she doesn’t have a good time in his company. She is constantly worried about her appearance. She even prepares topics and interesting things to tell him. This is not a romance book; Olivia and the Pianist prince don’t end up together. Yet, seducing and getting back (rescuing) him is the one and only motivation for Olivia in the entire story. 7.The ”Get a life already woman” syndrome. There is an entire chapter where Olivia doesn’t do anything else than waits for The Pianist to call. When does she work? Is there really nothing else in her life? There is a point where the narrator refers to being single as an “unfortunately fashionable thing lately”. Olivia is characterised as a stereotypical single woman who has a cat, a few female friends to order take out and sip prosecco with and who is desperate to find a partner. This is so sexist and limiting that I cannot even… Which brings me to the next two points. 8. The clumsy, whiny, self-deprecating to the point of self-abuse female lead is desperately (and irrevocably) in love with the mysterious and perfect male lead she spoke with twice when they exchanged like 10 words (Bella Swann syndrome). The clumsiness is used as device to advance the plot and get the male lead’s attention: Olivia falls over, knocks down, drops or loses things, gets drunk and is incapable to use simple tools and devices. The same incapable and helpless character doesn’t even break a sweat why infiltrating aa secret organisation of dangerous magicians. 9. Most characters are the caricatures of themselves: the coffeeshop owner, the hotel receptionist, Olivia’s both friends even the Pianist. They just embody a few generalisations (some of which are sexist and heteronormative) and any other characteristic that the plot needs. 10. Revealing one of the characters is a ghost by the ghost sending a letter to Olivia thus providing all the hints she needs to solve the last hurdle before the climax of the book. 11. Johnny Depp references. The book was published in 2009 so the author could not have known but it is still unpleasant. An additional reason why I’d leave out the contemporary references. They don’t tend to age well anyway. 12.Shakespeare statue / ghost. Each time it appeared it had different abilities: 1. triggered in the Leicester Park with the ring and by Olivia directly addressing him 2. telepathic communication between Olivia and the ghost (or ghost animated statue) 3. the statue just comes by on the Picadilly Circus to give a magic object to Olivia It irked me that it was just there to give you a Shakespeare quote and whatever else served the plot. 13.Every single time I thought the book cannot get any weirder it just did. To be honest this wasn’t always unpleasant. Like I said, I have very mixed feelings. There were a few golden (pun intended) moments and details that I liked (and a few I loved): 1.The idea of the Everycat and everything about the Everycat. 2.The boss-witch Hekate looks like Olivia’s older version. This is intriguing enough that I want to read the second part of the book just because of this (and the Everycat). 3.Hathor’s characterisation and unflappableness (totally a word, I looked it up). It would have been even more intriguing if she is not the Greatest Magician but some proxy of hers who will lead to her in, say, the next book? 4.I’d have liked to see Noel’s character in action. I mean magic action. I understand the authorial intent was to remove a mentor figure so Olivia could go her own way, but still. Now that he is outed as ghost I’m afraid we will never see him do anything exiting. And what did Shakespeare do to piss of the witches? 5.The Frog-prince-pianist was so whiny and mansplained and always assumed the worse. I’m not sure if that was the intent, but I found it hilarious. The frog-ness getting worse with time was also a good touch. 6.Witch rules: every witch must have a cat and witches cannot love. Both are interesting choices and have consequences in the worldbuilding that I’d like to know more about. How did Hathor get out of it? She used to be a witch but she is not a one anymore. How do you un-witch yourself? What if you are allergic to cats? 7.You can only find one golden ball in your life. It makes me wonder what will happen with the golden ball in the next books. It sounds like destiny or fate calling. How will Olivia end up being Hekate (is it her from the future?). 8.The reveal that Olivia is a witch (guessed it when she first looks into the mirror in Hathor’s shop) but it was still cool. I would have liked if her reaction to the news is explored more in detail, if the narrative shows if she thinks about it later. 9.The first scene is Olivia sitting on a toilet in a church. Quite an unusual choice and it was a good way of immediately setting the reader into the “head” of the character. All in all: I would recommend the book if you enjoyed the Bridget Jones books/ movies and the Da Vinci code. The narrative contains sexist elements and negative stereotypes of single women so if this is something that disturbs you, give it a pass. I will very likely read the remaining two books of the trilogy out of curiosity, but I would not re-read this book. Ideal present for: *That* aunt that always asks when you are going to get married.

#deutsch#fantasy#fairy tales#trilogy#witchcraft#the princess and the frog#bridget jones#literary references#Shakespeare#Goethe#Keats#Hexendreimaldrei#german#London#Wien

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Because you were talking about Juzo, I'm curious, why was Kirigiri one of your favorites as well? I feel her character development was minimalistic at best and was dropped after the first game, especially in the dr3 anime

Although Ouma is definitely myfavorite ndrv3 character, I’ve been joking a lot lately that Saihara is the one Iactually relate to the most—because I too am an anxious depressed mess, feelsocially awkward at all times, and am a huge Kirigiri fan.

While Kirigiri is certainly nota character to demonstrate her emotions very noticeably outward, I wouldn’t saythat her development is minimalistic in the first game. If anything, Kirigiriis one of the characters whose growth and development is followed the most bythe first game, after Naegi.

The thing is, her developmentstarts from a different position than Naegi’s. Rather than starting from astandpoint of being naïve and overly optimistic or trusting, Kirigiri startsout rather like Ouma, actually. She’s rather cynical at heart, especially indr1, something many people tend to forget about her character. As a detective,she accepts what neither Saihara nor Jin Kirigiri want to accept about theirjob: that people have to be doubted, suspected, and questioned.

Dr3 certainly does drop theball on her character development, but, well—it did that for everyone’scharacter development, pretty much. Future Arc started strong, showed lots ofpromise, and then sadly ruined all the potential it had with weak writing. Bydelegating Kirigiri to the role of “damsel in distress” and “beautiful self-sacrificingcinnamon roll” all at once, dr3 did a really bad job at remembering whyKirigiri became so popular in the first place, because she never used to fitinto those character tropes typically reserved for female characters in the DRseries.

While I’m glad she lived (Seiko’santidote bottle was something I noticed right away when her “death” episodefirst aired, so the foreshadowing was definitely there), I don’t feel dr3 didher justice by any means. She was forced to take a backseat role; just as Chisawas used as nothing more than an object for Munakata’s character arc, Kirigiriwas forced to parallel her by being used as an object for Naegi’s arc. And thatwas a pretty huge insult to her character, in my opinion. Had the switch beenthe other way around, with Naegi sacrificing himself (in a wonderful throwbackto dr1 Chapter 5) and Kirigiri taking an unexpected protagonist role, I would’vebeen a lot more satisfied.

But unlike other DR characters,there are plenty of other materials besides just dr3 to give us insight intoKirigiri. The Kirigiri light novels, for one, as well as the new visual novel,Kirigiri Sou. Kirigiri’s continued popularity is a testament to what sherepresents to the DR series, from a mystery perspective. Just as Junko isiconic for her role as an antagonist, Kirigiri is iconic because of her role asnot only a detective, but thedetective. All the insight she provides Naegi and the player in dr1 about whatsolving a mystery entails, about how to reflect on the mindset of both victimsand culprits, as well as what exposing the truth really means, are themes thathave come up not only in dr1 but in every other DR installment to date,including ndrv3.

Kirigiri is perhaps thecharacter whose advice and teachings have lasted the longest. She instinctivelyunderstands, and helps the player understand, what a real mystery is all about.Where ndrv3 leads the player into a false sense of security before lampshadinghow ridiculous and utterly dangerous it is to trust people blindly, Kirigiriwarns Naegi of the dangers of blind trust and extreme paranoia as early asChapter 1 in dr1. While she’s certainly aloof and uninterested in socializing,especially at first, she’s someone who grasps what the “heart” of a mystery isall about, and helps guide Naegi and the player into understanding it too. Andunderstanding the “heart” is the first step to understanding any mystery presentedin the future, too.

Kirigiri starts dr1 as someonewho is level-headed, reasonable, and extremelysecretive (excessively so, sometimes). She’s smart, calm, and collected, butcertainly not infallible; having replayed dr1 quite recently myself, I’venoticed several instances in which her failure to take action as quickly as shecould’ve causes her to be surprised and blindsided when murders take placeelsewhere. Like Ouma, she often prioritizes her own objectives in: 1.)exploring the school and exposing the mastermind behind the whole game, and 2.)finding out the truth about her own memories, backstory, and talent, so smallerhurdles and culprits among the group can and often do throw her off guard.

Most importantly to note, she’snot a team player, especially not at first. Kirigiri’s cynicism and paranoiamakes it difficult for her to trust others besides herself, though notimpossible. The one major difference between her and Ouma is that Kirigiribelieved in the necessity of trust after doubting others first. Her bond oftrust with Naegi is something gradually developed throughout the course of dr1,slowly and steadily. It’s not something she would have developed with justanyone, but rather something she and Naegi both developed specifically becauseof their shared experiences with one another.

But she certainly didn’t careto explain her motivations or objectives to the rest of the group, nor did shebelieve in telling even Naegi about what she knew on anything more than a “need-to-know”basis. She’s extremely sensitive about people butting in on her personal life. Inher FTEs she says point-blank that she feels emotions just the same as otherpeople, but that she intentionally hides them behind a mask of composure—becauseshe has nothing to gain by tipping other people off as to what she’s feeling orthinking at the moment. In this sense, she’s also quite similar to Ouma. Butwhere Ouma’s mask is all about feigning every emotion, usually in a veryexaggerated fashion, Kirigiri’s is a mask of stoicism.

When others in the group wantto know where she’s been or what she’s been doing, she doesn’t feel any need totell them. Even when it clearly begins putting the group in a more disorganizedstate and things begin reaching a boiling point in Chapters 4 and 5, sheremains extremely closed-off and secretive, and it’s clear that there’s no onein the group she would trust with any of her personal information besidesNaegi. And even Naegi, she never tells the whole story to.

Naegi had to make a consciousdecision to cover for Kirigiri’s lie in Chapter 5—it wasn’t something sheprepared him for, and she knew there was a chance she might actually be sendinghim to his death, if Alter Ego failed to kick in. Still, it was a sacrifice shewas willing to make if need be, and that’s something incredibly cold andpragmatic and that I love to see in characters who are all about “the endsjustify the means.”

Just like Ouma, she wasabsolutely dead set on investigating things to the end. She couldn’t let thingsend with her death, which is why she refused to sacrifice herself in Chapter 5,just as Ouma initially refuses to let himself die in ndrv3 Chapter 4. Hertunnel vision towards stopping the mastermind and figuring out what happened toJin Kirigiri and how far he was involved with the killing game means that shedoesn’t want other people sticking their nose into her business.

Her feelings towards Jin arethe main proof of the fact that Kirigiri can also be driven by personalvendettas, pettiness, and unresolved anger and frustration. As someone who canperfectly understand the resentment towards an absent father figure, I alwaysappreciated that Kirigiri’s conflicted feelings about Jin were handled quitewell in dr1. The narrative ultimately focuses on the fact that yes, Jin lovedhis daughter and was a caring father, but he was also careless, overlytrusting, and thoughtless about how his actions would influence others.Kirigiri was allowed to be angry at Jinwhile also still caring about him, and that was a deeply realistic and humanreaction.

I appreciate the fact thatKirigiri, especially in dr1, was a character never played for fanservice, andnever used as an object of male character development or waifu-baiting. Therewas little to no forced romance between Naegi and Kirigiri in the first gamewhich is what led me to enjoying naegiri quite a lot on my own—when thenarrative isn’t trying to push it in a romantic connotation, I tend to warm upto these sorts of ships a lot faster. Dr1 was very emphatic about appreciatingtheir dynamic as friends first, withanything more than that being a matter of personal interpretation.

The fact that she’s extremelyintelligent, capable, and arguably a protagonist in her own right thanks tospinoffs like DR: Kirigiri and Kirigiri Sou now is a large part of the reasonwhy she’s still #2 on my overall DR ranking. Before Ouma came along, she wasactually #1 and I didn’t think anyone would ever shake her position. I stillreally enjoy her every time I do a reread; if anything, Ouma’s character hasmade me appreciate Kirigiri even more, given the noticeable similaritiesbetween them.

Anyway, these are just my personalthoughts on the subject! I’ve always appreciated that Kirigiri was a characterwho both embraces and embodies the role of a detective, but who alsounderstands the full meaning of “the truth,” and isn’t afraid to lie, cheat, orrely on other cold and calculating tactics in order to achieve her objectives. She’san extremely compelling female character in my opinion, and I’ll always have abig soft spot for her. Thanks for asking, anon!

#dr1#dangan ronpa#danganronpa#kyouko kirigiri#kirigiri kyouko#ndrv3 spoilers //#spoiler tag is there because i make a few comparisons to ouma!#my meta#okay to reblog#anonymous

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Poetic Prose Tethered To Memory In Void Star

She looked into his other memory, the last eleven years of his life’s experience fixed forever in deep strata of data, immobile now, and somehow cold. Of course, she thought, I should have known, this is what death is, this stillness in memory.

Conveying a sense of a near future world in which the street finding its own uses for things ends up compiling moments where technology not yet here is antiquated or trash. A laptop has the potential to convey a “superior” education to Kern, a young man growing up in a Favela, and he takes what he needs from the machine; reflecting and embodying the harsh lines of poverty and society in his own body. Kern uses technology to become a weapon. But he doesn’t think like one.

“Like sculpture, the favelas, but she reminds herself that, avant-garde rapture notwithstanding, they’re sinks for all the saddest ugliness in the world, that to set foot in them is to step back decades, or even centuries, they’re the last bastion of the old…”