#hundreds of years before this country was founded. second the first colonist to call it massachusetts was fucking john smith in 1610

Text

this post sucks so bad massachusetts takes its name from the indigenous massachusett people who were genocided and whose land was stolen and that would be obvious if you would think for a single second and look up the etymology before posting. mocking a native language that was eradicated for centuries and is only now beginning to be revived is not fucking funny it is ignorant and racist and cruel

#ribbits#genocide mention#i am actually quite mad that that has 10k notes. scrolled through the notes and only saw one correction#someone asked ‘why did the founding fathers name it that’ first of all the fucking people who were already living here named it that#hundreds of years before this country was founded. second the first colonist to call it massachusetts was fucking john smith in 1610

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Caelus Homebrew: the Aenar

Separated from the Sea of Skerrit by the hills and peaks of the Northern Fracture, the Thundering Plains stretch for hundreds of miles. The grasslands here are prone to thunderstorms that blow in off the Western Sea and give the place its name. The Thundering Plains are ruled by the Aenar, a tall, tanned people with flashing red-brown hair. They are often called the spear maidens, though in truth this refers to only a particular group of young warrior women, the Aenar’s most prolific warriors.

Once subject to the Verinigan Empire, the Aenar were shepherds who domesticated the imposing horses of the grasslands and turned them to war. Legend says it was the goddess Anika herself who taught the first warrior maidens to tame the horses after she subdued the great spirit of the plains, almost 900 years ago. Legends attest these women became the Valmeyr, the ghostly Maidens of the Slain who serve Anika today. With horse and spear they swept the Veringian colonists away and established their rule over the grasslands in a series of three bloody wars that saw the Veringian Empire lose each time. The Aenar’s victory would trigger a series of rebellions that bled the Veringian Empire for seven hundred years. The reputation of the Aenar’s rider women, of howling lancers attacking under clouds of arrows, led many neighboring countries to offer gold in return for their services.

The Aenar revere Anika the Horse-tamer, also called the Shepherd, Battle-mother, and All-mother, but also honor her children. These gods form a tight-knit group, united by an apocalyptic vision that foretells a final battle between the Aenar gods and the orc gods. For the Aenar, a second Sundering is not merely a possibility, it is a prophesied certainty. They and their gods intend to be ready for it. This knowledge of their deaths and glories make the Aenar gods fatalistic, and their people are alike. In battle they are feared for their thundering charges and grim resolve. The spear-maidens believe it is better to die with spear in hand than be conquered by the enemy.

Demand for their martial abilities mean that the Aenar have traveled far and wide. Indeed, there are several Aenar colonies outside the motherland, founded by exiles or land-hungry warriors. They have also made common cause with local powers, when needs be. They fought in coalition with the Rivercrown Confederation and the Marcher Princes when the Temple States attempted their northern expansion, throwing the Holy Army back in the year 1417. Before that their warriors battled alongside the gray elves of the north to check the hobgoblin legions of the Shotahan Empire.

The People

The Aenar largely live in semi-nomadic clans that criss-cross the Thundering Plains. A matriarch, typically the eldest surviving daughter of the leading family, leads the tribe in all things. She is the final word on disputes of any kind, however she is typically advised by a council made up of chosen warrior representatives and the village fathers. Some take counsel with druids as well, but a few reject them from living in their halls.

The Spear Maidens

When foreigners think of the Aenar, it is invariably their howling warrior maidens that come to mind. The spear maidens are roving bands of unmarried young women who gather together to ride the Thundering Plains in defense of their homeland or to offer their services in foreign lands as sellspears. It is expected for the matriarch’s chosen heir to ride as a spear maiden, lest she not be respected as a warrior, but many second and third daughters do so to find service, fame, and coin.

The warrior women typically follow the mightiest or cleverest among them, but each band chooses its leader as its own conscience dictates. When they choose to ride as a spear maiden the women swear to pay special honor to Anika’s warrior daughter, Valfreyj, who commands the ghostly Valmeyr. Each band will have a simple and portable shrine for devotions. Valfreyj’s dark brother, Valoke, is patron to druids and any Aenar men who work magic. As such the spear maidens enjoy the favor of the druids, and it is not uncommon for a band to have a powerful spellcaster in their ranks.

The Druids

While it is true that women fill most of the roles of power among the clans, it is typically men who wear the robes and antlers of the druids. Deserved or not, they often have sinister reputations. This unease is a reflection of the relationship between the Aenar and the spirits, for the Aenar are a godly folk and they once thought the spirits were rivals to their gods. Even when they learned otherwise, there were many among the Aenar who angrily rejected any overtures from the spirits, for the spirits had often borne witness to Aenar’s suffering under the Veringian Empire and rendered no aid. The anger is largely one-sided. The spirits’ power and presence could not be denied, however, so some learned to speak with the spirits and treat with them.

Wary of the warrior women, the spirits instead turned to the village fathers. In time the spirit-speakers split away from the village fathers and retreated into the wild places. It was during this time that Valoke descended to the mortal realm and took up patronage of the spirit-speakers, who eventually became an order of druids and lorekeepers. Stag and Horse are both well-respected by the Aenar, they are both counted friends of Valoke, too. The druids speak for the spirits and with the patronage of the Dark Brother, ensuring their continued credibility. Even the most churlish clan mother does not turn away a druid who speaks for Horse.

0 notes

Text

Writeober #3: Bone

Gerlach Schwartztern cackled maniacally as he felt the bindings keeping him out of the world faltering. He had expected this, ever since he’d seen that the historical building where the ritual had been performed was scheduled to be knocked down. There had been three days of demolition, and finally, the sacred circle at the center had been breached. He was free!

“Hey! You! This is a hardhat area! You can’t be in here!”

Gerlach shuffled around – being bound out of reality, able only to see what was transpiring, without having muscles to move, had done no good for his physique, and all his muscles were stiff beyond belief – to see a man in a bright yellow helmet and a shining orange vest, yelling at him.

“Dost thou know to whom thou speaketh?” he said, smiling cruelly, raising his own bony fingers as he prepared to teach the fool a lesson.

“Come on, asshole. Don’t give me that Scadian shit,” the man said. “You need to get off the grounds. It’s not safe.”

“Unsafe for whom?” Gerlach laughed, and reached out with his power. He called out to the dead buried below and all around to rise from their graves.

Nothing happened.

“Unsafe for you, asshole. You. Did I stutter? Get the hell out of here before I have to call the cops.”

Where were the dead?

Now that he was looking for them, he couldn’t feel them. In the Old World, there had been skeletons everywhere. But he’d had to flee the witchfinders – not the idiots who accused old women with black cats and herbal knowledge of being witches, but the ones with real power, who hunted those with real magic – so he’d taken passage to the New World, four hundred years ago.

Life was hard, then. Many colonists died, and their skeletons became his servants. He’d terrorized the colonists and the natives alike… until mages of both groups had teamed up against him. The natives had used their magic to confine him within a single town, herding him to the colonist mages, who’d bound him and locked him outside the world so long as the runes and symbols they’d carved in the stone under a church floor remained intact.

Now that the church was demolished, and the stone broken, Gerlach was free. He’d been able to see the world from his prison outside it; he’d seen the population explode. Surely the dead must be everywhere! People still died in this brave new world, did they not?

“Very well, knave. I shall leave, if you direct me to a graveyard.”

The man in the yellow hat sighed. “I don’t have to do this,” he said. “You’ve been an ass. But fine. The new church that replaced this one is about two miles down the road, and it has a graveyard. I think you have to turn right on Whitman – or I dunno, maybe it’s Baker? One of those streets. Go in about three blocks, you’ll find the church, and the graveyard’s across the street.”

“Then there I shall go,” Gerlach said, picking up his robes – they were dragging in the dust of the construction – and walking toward the gate in the fence. An interesting fence, that, made of wires woven together loosely.

“Thank you is a thing, asshole!” the man called after him, but Gerlach did not thank his inferiors.

***

It took far longer to find the church than the knave’s directions suggested. Gerlach was calling down curses on the man’s entire family unto the seventh generation by the time he finally found it, his legs and feet screaming at him for making them perform so much work after just being embodied again.

But there it was. The graveyard. And now he could feel the dead, lurking below, waiting for his call. With them at his command, he would rule over this town – and others. As the dead came to answer him, he would grow in power, and he would be able to call more and more of them as his power expanded. Eventually he would rule over this entire nation. Perhaps even the world.

Gerlach took a deep breath, and then called to the dead.

He felt them respond, felt skeletons restless in coffins push against the lids.

And push.

And push.

“What transpires here?” he roared. “You should be rising from your graves! I have called you, and you must come!”

Skeletons still pushed against coffin lids.

“Why can you not come forth?!”

Some skeletons broke their wrists and fingers trying to push open their coffin lids. None of them succeeded in actually opening anything.

Gerlach tried for hours. And then he walked to another graveyard and tried again. Still the dead could not open their coffins. Gerlach was furious. Back in the Old World, only the most wealthy had even had coffins. And they were decorated wooden boxes that a sufficiently motivated skeleton could punch through. Here in the New World, four hundred years after arriving, apparently skeletons were all contained in unbreakable coffins.

He sank to his knees on the ground and screamed, his dreams of conquest dying just like the skeletons trapped in unbreakable coffins, and just as unlikely to rise under his power.

***

Elias Whittaker was furious.

The city had concealed the plans to demolish the old church until he was out of the country, and then gone through with the destruction. He hadn’t known about it until his daughter drove by the place and saw it destroyed. It had been a month.

None of the records of the Whittaker family, passed down from father to son (or daughter in some cases), had said anything about Gerlach Schwarztern being a patient and crafty man. A brilliant necromancer, yes, but he’d named himself Black Star in German for gods’ sake. He was not the type to lay low. So why hadn’t the city fallen to walking skeletons yet?

Could it be that Schwarztern had died in his prison, or perhaps died the moment he re-entered the world and time began for him again? Maybe all the aging he hadn’t done while he was trapped caught up with him at once.

But Elias didn’t think that was likely. From everything he’d read in the family tomes, carefully preserved for four hundred years, the crafters of the spell hadn’t thought it would do that. They had warned, over and over, of the danger should the binding circle they’d carved into the rock ever break or wear. All of them had passed on the knowledge to their children, but between illness, war, and adult children’s desire to strike out west to make a new life for themselves, far away from their parents… Now the Whittaker family was the only one left.

Elias had been on the Board for Historical Preservation, had argued for years that that tiny run-down little church needed to be preserved exactly as the city’s founders had left it, that it was nearly 400 years old and was a view backward into a past that America had almost lost, the early days of the colonies. And what happened? The moment he was out of the country, the rest of the Board caved in like a wet tissue and let the city government have its way. They were going to put up some mixed-use development there, townhomes and offices and retail all mixed together, somehow. And that was worth letting an ancient necromancer free in a world where almost no one remembered that magic existed, or how to invoke it. Right.

But there was nothing Elias could find to indicate that Schwartztern had escaped. No graveyards were disturbed. No records of dead people getting up and walking. No disturbances at the morgue.

His daughter Rebecca found something—a record of an old man who’d been caught in the Jewish graveyard, obviously digging up graves because several graves had shown signs that the dirt had been interfered with, holes and clods and piles of dirt all over the graves. The elderly caretaker for the graveyard was still spry enough to shoot at an anti-Semite committing a hate crime, though. Rebecca reported that the old caretaker didn’t know if he’d actually hit the man in the tattered black coat or not, but that if he had, he must have only winged him, because the man had run without sign of injury. Since then, members of the Jewish community had been taking turns helping him guard the graveyard, with their own guns, and there had been no further disturbance.

Oddly, the fellow hadn’t left a shovel behind, but Ira Friedburg, the caretaker, had never seen him carrying one, either. Maybe it was under his coat, and the bullet had hit it instead of the man.

Of course, Elias knew why Schwartztern hadn’t needed a shovel. The graves had been disturbed from the inside. But why had the Jewish graveyard been affected, and not the much less well-guarded Catholic and Protestant ones? Schwartztern might well have been an anti-Semite, considering that in that time period almost everyone was, but he had never shown a preference for any specific type of corpse.

For the first time in his life Elias was grateful for the Second Amendment. Gerlach couldn’t know of any firearm technology more advanced than maybe a musket. A small weapon that fired deadly ammunition with terrifying accuracy and speed was nothing Gerlach Schwartztern could have any experience with. And the Jewish graveyard had suffered enough hate crimes that the caretaker patrolled it with a gun, regularly, and was small enough that Schwartztern hadn’t managed to raise a single body before being caught at it.

It was frustrating and maddening. He searched for three months. No sign of Schwartztern anywhere. Had the man left town? Was he right now trying to raise the dead in New York City or Washington DC or something? Had he returned to his homeland? Wait, no, he couldn’t have done that without a passport.

In desperation Elias started going around to funeral homes, asking them if they’d seen a man of Schwartztern’s description – long graying hair, a long beard, pale skin, aquiline features, crooked teeth. None of them had.

Until Elias went to Baron and Sons Funeral Home, and was met at the door by a man who looked exactly like the portraits of Schwartztern that had been passed down, if the man had gotten a modern haircut, a shave, and gotten his teeth straightened.

Elias’ eyes widened. “Gerlach Schwartztern?”

The man looked surprised. “There’s not many who know me by that name,” he said, and called back into the funeral home. “Mr. Baron, there’s a man here who wants to speak to me specifically. I’ll take a break to talk to him and then return to the clock.”

“Sure, that sounds fine,” a man’s voice called back.

“How are you – Why are you – What, did you find religion while you were trapped? You were freed almost four months ago,” Elias hissed. “But you’ve raised nothing.”

“Not entirely true,” Schwartztern said. He had a thick accent, but it wasn’t quite placeable – which made sense, because it was from another country 400 years ago. His English, though, sounded plausibly modern for a foreigner. “Let us walk to the back.”

“Where the graves are, and where you can attack me?” Elias snapped.

Schwartztern shook his head. “There is a contemplation garden for the grieving. No funerals are scheduled now, so it is unoccupied. We can talk without interruption.”

Oh. Right. There wasn’t a cemetery anywhere near the funeral home. That was why funeral processions were a thing. He followed the ancient necromancer, bemused, to the garden. “Did you forget your powers? Or lose them?”

“I assume from your knowledge of my name that you were one of the guardians my captors must have left behind to keep me contained,” Schwartztern said. “You may call me Gerlach Schwartz now, though. Or simply Gerlach. Apparently this new age is one of great informality. And yet they don’t even use ‘thou’ anymore.”

“Uh, yeah, we got rid of that a while back,” Elias said. “And you’re correct. My family has been keeping watch. Everything I’ve read said to expect an insane necromancer who would do anything to rule over the living with the power of the dead. But here you are in a building with… maybe two dead people?”

“There are four corpses here, in fact, but you’re correct. Four corpses is far from enough to conquer a town with.”

“What happened?”

“Modern caskets,” Gerlach said simply. “In my day, only the wealthy were even interred in a coffin; most bodies were lowered into the bare ground. Apparently since that time everyone who dies is buried in an impregnable sepulcher called a ‘casket’, or they are burned to ash… except for the Jews, who bury their dead in wooden boxes that I could at least work with, before the Jew fired his weapon at me.”

He shook his head. “The weapons they have in this time! It would never work, raising the dead, not now. I have been watching some of their movies—” He put a strange emphasis on the word. “So many tales of dead rising and biting the living to make them a risen corpse as well. And in these tales, everyone has one of these terrifying weapons, and they can entirely destroy a corpse with them. Perhaps a skeleton would be more difficult to hit, but with sufficient ordinance, they would prevail over my skeletons as well. The creators of these tales added the part where the dead can bite and their bite kills to make it a believable tragedy, else none would believe that enough firepower could not overwhelm even the dead.”

Elias rather thought no one had done anything to the plots of zombie movies to make them believable, but he could see how a necromancer might have a different opinion. “So you’re telling me you’ve given up. That I don’t need to kill you or capture you because you aren’t interested in raising the dead to conquer, anymore.”

Gerlach laughed. “Interested, perhaps. But it will not work, and this I now know. There are far more dead today, but that is because there are far, far more living, and they greatly outnumber the dead. Most of the dead are locked away in boxes far too strong for a skeleton to break open. I know, for I have made them try, and try again.” He shrugged. “So it is not practical. And it is also hardly necessary.”

“Why unnecessary?”

“Men live like kings in your time, young man.” Elias was not a young man – he might actually be older than Gerlach was when he was trapped – but this didn’t seem like something worth arguing to a man born over 450 years ago. “You need no servants to bring you hot water for your bath – simply turn a knob, and hot water comes forth! Food of any kind can be had at any time, no matter the season! Music can play anywhere, whether musicians are there to play it, or not. Entertainments as rich as the plays put on for kings can play endlessly, never repeating, on a box of light in your home – a home which is heated in the winter and cooled in the summer, and both are done evenly, throughout the home, without risk of fire. And there are treatments for lice.”

That explained the shorter hair. “So you’re, what? Trying to be a good tax-paying citizen now?”

“I am told there will be great, great difficulties in becoming a citizen, as I cannot present papers to prove what nation I was born in, or what date, or when I came to this land. Apparently I am an ‘illegal immigrant’, and if I am found by the authorities, they will deport me… somewhere. Since my own nationality no longer even exists, I have no idea where. But my employers here are sympathetic.” He nodded at the funeral home. “I came here because I thought the presence of the dead plus the title Baron meant another necromancer was here, but that was not the case… as I suspect you know well. They’ve arranged for me to work here and learn their trade, for there are many techniques of preserving the dead that exist now but did not, in my day. Apparently they are paying me ‘under the table’, an expression I understand not, except to say it is a means of paying one with no papers to prove their identity.”

“It means they’re paying you in cash and not taking out your taxes, so I guess you’re not a taxpayer after all.”

“In my day, taxes were paid in grain.”

“Sometimes money is referred to as ‘bread’ in this day and age, but the days when you could actually pay tax in grain are long behind us.”

“I do realize that,” Gerlach said. “Have I satisfied your curiosity? Do you understand now that I present no threat to your world?”

“And you use your necromancy here?”

“As God witness, no, why would I do that? They have techniques for moving bodies and they know nothing of magic. If I were to use the power I have over the dead, now, it would perhaps be as a detective, who can hunt down dead bodies after they are murdered and hidden away by the murderer. I have watched many entertainments about detectives,” he said, in a tone as if he were telling a salacious secret. “In my day the profession didn’t exist, but today it seems a very popular job. I wonder that any murderers can go free, with so many detectives.”

“It’s… not actually that popular in real life. People just like stories about detectives. They like to see a mystery presented to them, so they can try to solve it, or enjoy watching the detective solve it.”

“Ah. Well, I have much to learn about this new world before I dare leave this job,” Gerlach said. “They provide me with a room here to live in, upstairs, but for food and clothing and a box for entertainments I must pay my own way.”

Elias shook his head in complete bemusement. All of the effort he’d put into, his whole life, to keep the necromancer contained, and this was what Gerlach did when he got free. “Well, there’s nothing I can charge you with and nothing you’re doing that warrants my interference… but I will be watching you.”

“That would be delightful!” Gerlach said. “It grows tedious sometimes, to have no acquaintances I can share knowledge of the past with, or my necromancy. You would make an excellent companion!”

I have worked all my life to keep this man in prison and he wants to be my friend. Well, it would help Elias make sure that Gerlach was continuing to not be a threat. “Fine, I’ll come take you out to lunch sometime.”

“I look forward to it greatly!”

As Elias left, he wondered how he was going to explain any of this to Rebecca.

--------------------------------------------------

From @writing-prompt-s, “ An ancient evil awakens to destroy humanity, only to find out he is no match for modern technology, thus forcing him to become a functioning member of society. “

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today’s @rwrb-social-isolation prompt is to talk about something from history we love, so I did a deep, deep dive into a near-utopian colony headed by a man who was, truly, an icon. A Byronic hero two hundred years before Byron himself. It got rambly, but at this point, who’s surprised. Please enjoy.

All us good little American drones know the story of how white people came to America. They settled at Plymouth, and they struggled and struggled for years, but with the help of friendly natives, they finally succeeded and murdered millions with biowarfare and also guns built the great country we live in today.

Were there other, non-Plymouth colonies? Jamestown, of course, the Macho Dream that men who are really into WWII love to talk about. Boring. Let’s talk about a fun colony.

Let’s talk about Merrymount, a town founded on a distrust of Christian Puritanism, the abolition of slavery, popular revolt, equality with natives, a pagan beliefs. Sound fake? See attached bibliography.

History, huh? Let’s get into it.

To talk about Merrymount, we have to talk about Thomas Morton, the Lord of Misrule. He was born in 1579 in Devon, England, a region despised by the more religious parts of the country for still hanging onto some of England’s traditional pagan practices. It was particularly known for celebrating the land and its guiding principles of neighborliness and quietness (the belief that keeping peace was more important than nearly anything else). We don’t know much about his family, but we’re pretty sure he was the second son to a middle-class family, largely because he went to law school in London (something that wouldn’t have been affordable for lower class folks, but that an older son wouldn’t have had to do under the laws of primogeniture).

The London Morton arrived in was overcrowded, and bouts of plague were not uncommon. The population was booming, and tensions were rising between the deeply Christian Reform movement and the more Pagan Renaissance. In particular, we saw the rise of Puritanism and Separatism, both of which were extreme versions of Christianity (a la those pilgrims we all cosplayed every Thanksgiving in elementary school), and both of which Morton hated. From what we can tell, he was first an observer, and his coursework would have taught him to question what he was told and to argue his own points and beliefs.

Following his time in school and his general disillusionment with established Christian society, he became a traveling lawyer for a time. In his late 30s, Morton began working for Sir Ferdinando Gorges, a major investor in Plymouth, founder of Maine, and “Father of English Colonization in North America”. He first traveled to America in 1622, and in his book, he declared “The more I looked, the more I liked it. And when I had more seriously considered of the beauty of the place, with all her fair endowments, I did not think that in all the known world it could be paralleled”. However, he was back in England in 1623, complaining of Puritan intolerance.

Following a dissolved engagement, Morton once again set sail for America in 1624, aboard the ship Unity under command of his friend Captain Richard Wollaston and accompanied by 30 indentured servants. They eventually were given land by and began trading with the Algonquin tribes, who were native to the region and whom Morton found more civilized than the Puritans in Plymouth. They named their town, which is now Quincy, MA, “Mount Wollaston”.

From Morton’s book, we can see that he got to know native culture relatively well. He attended Algonquin dinners and funerals. He learned at least some of the language, and he celebrated their respect for their elders and general family structure. During this time he also had his first interaction with Plymouth, which went much less well than his interactions with Algonquin tribes. He declared that he “found the Massachusetts Indians more full of humanity than the Christians”, and it is after this meeting that he began to furnish native tribes with powder and shot for their guns, often when English colonists couldn’t get any. Needless to say, he doesn’t come off particularly well in Plymouth’s writing about him.

By 1626, Mount Wollaston was booming. Colonists tired of Plymouth’s harsh rules were flocking to the more liberal town when Morton found out that Wollaston had been selling indentured servants as slaves. Outraged, he encouraged them to rebel, and Wollaston fled, leaving Morton the sole leader (or “host”, the term he prefered) of the newly renamed Merrymount (or “Ma-re Mount, which is a pun on the Latin for “ocean”).

(That’s right, this man got control of a town, declared himself just a host, and then renamed it based on a nerdy pun. an icon.)

Merrymount was, generally, from most sources I can find, a pretty chill place to be. People were declared equal, and there was a pretty high degree of integration with Algonquin tribes. Though Morton did do what he could to encourage the Algonquin peoples to settle into a more English lifestyle, he did so not by force, but by providing them with free salt to use in preserving food, therefore negating the need for a nomadic lifestyle. Which... pressuring people to give up their way of life isn’t great. But doing it this way is a lot better than the way that pretty much every other colonizer was doing it.

The real pinacle of the integration of English and Algonquin peoples was a May Day Celebration. Pretty much everyone celebrated the start of spring, as it meant that you’d survived the winter and life in general would likely start to improve with the warmer weather. May Day was both a celebration of springtime and a unifying holiday, a time when the different cultures came together and often a time when English men would begin to woo Algonquin women. The Puritans of Plymouth called it Bacchic and evil, so I can only assume it was a generally good time.

However, by 1628, it was all too much for Plymouth. Morton’s general chill vibe, his trading with natives (and the threat it posed to Plymouth’s monopoly), Merrymount’s integration with Algonquin tribes, and just generally the disregard for Puritan ways all exploded when, in celebration of May Day, Merrymount erected an eighty-foot maypole.

Now, I know eighty feet is hard to visualize. Especially if you’re from somewhere that uses the metric system. But an average story of a building is about ten feet. So just... think of an eight story building. This thing was MASSIVE. It’s as tall as my freshman year dorm. It was clearly visible from Plymouth, and it was the final straw. Morton was arrested and left to die on a rock that could only generously be called an island.

He was back by fall of 1629, but found Merrymount in ruins and a particularly harsh winter greeted him that year, and he was shipped back to England in 1630, a voyage that almost killed him.

By 1631, he was back in the game suing the Massachusetts Bay Company, the political and financial backers of the Plymouth Puritans. He won in 1635, cutting off much of Plymouth’s English support and causing many to leave it for settlements in Connecticut.

His book, New English Canaan published in 1637, launched him into celebrity. In 1643, he tried to return to Massachusetts, but was turned away upon arrival. He was exiled to Maine, where he passed away at the age of 71.

And that’s Thomas Morton! I first heard about his story in A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski, but I couldn’t remember enough/didn’t find anything in other sources to establish the queer context for Merrymount other than its rejection of Puritanism.

Attached bibliography (not formatted correctly, because fuck the MLA and the APA).

General overview of his life

Morton’s book, New English Canaan

Spunky bio largely focused on Merrymount/the maypole

Spunky bio two: Maypole boogaloo

His wikipedia, which is just nice and readable

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1619 Project https://nyti.ms/2Hjvu0L

The 1619 Project is a major initiative from The New York Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.

"We asked 16 writers to bring consequential moments in African-American history to life. Here are their poems and stories:"

Published August 14, 2019 | "1619 Project" New York Times | Posted August 16, 2019 |

⬤ August 1619

A poem by Clint Smith

In Aug. 1619, a ship arrived in Point Comfort, Va., carrying more than 20 enslaved Africans, the first on record to be brought to the English colony of Virginia. They were among the 12.5 million Africans forced into the trans-Atlantic slave trade, their journey to the New World today known as the Middle Passage.

Over the course of 350 years,

36,000 slave ships crossed the Atlantic

Ocean. I walk over to the globe & move

my finger back & forth between

the fragile continents. I try to keep

count how many times I drag

my hand across the bristled

hemispheres, but grow weary of chasing

a history that swallowed me.

For every hundred people who were

captured & enslaved, forty died before they

ever reached the New World.

I pull my index finger from Angola

to Brazil & feel the bodies jumping from

the ship.

I drag my thumb from Ghana

to Jamaica & feel the weight of dysentery

make an anvil of my touch.

I slide my ring finger from Senegal

to South Carolina & feel the ocean

separate a million families.

The soft hum of history spins

on its tilted axis. A cavalcade of ghost ships

wash their hands of all they carried.

Clint Smith is a doctoral candidate at Harvard University and the author of the poetry collection “Counting Descent,” as well as a forthcoming nonfiction book, “How the Word Is Passed.” Photo illustration by Jon Key. Diagram: Getty Images.

⬤ March 5, 1770

A poem by Yusef Komunyakaa

In 1770, Crispus Attucks, a fugitive from slavery who worked as dockworker, became the first American to die for the cause of independence after being shot in a clash with British troops.

African & Natick blood-born

known along paths up & down

Boston Harbor, escaped slave,

harpooner & rope maker,

he never dreamt a pursuit of happiness

or destiny, yet rallied

beside patriots who hurled a fury

of snowballs, craggy dirt-frozen

chunks of ice, & oyster shells

at the stout flank of redcoats,

as the 29th Regiment of Foot

aimed muskets, waiting for fire!

How often had he walked, gazing

down at gray timbers of the wharf,

as if to find a lost copper coin?

Wind deviled cold air as he stood

leaning on his hardwood stick,

& then two lead bullets

tore his chest, blood reddening snow

on King Street, March 5, 1770,

first to fall on captain’s command.

Five colonists lay for calling hours

in Faneuil Hall before sharing a grave

at the Granary Burying Ground.

They had laid a foundering stone

for the Minutemen at Lexington

& Concord, first to defy & die,

& an echo of the future rose over

the courtroom as John Adams

defended the Brits, calling the dead

a “motley rabble of saucy boys,

negroes & mulattoes, Irish

teagues & outlandish jacktars,”

who made soldiers fear for their lives,

& at day’s end only two would pay

with the branding of their thumbs.

Yusef Komunyakaa is a poet whose books include “The Emperor of Water Clocks” and “Neon Vernacular,” for which he received the Pulitzer Prize. He teaches at N.Y.U. Photo illustration by Jon Key. Boston Massacre: National Archives. Attucks: Getty Images.

⬤ 1773

A poem by Eve L. Ewing

In 1773, a publishing house in London released “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” by Phillis Wheatley, a 20-year-old enslaved woman in Boston, making her the first African-American to publish a book of poetry.

Pretend I wrote this at your grave.

Pretend the grave is marked. Pretend we know where it is.

Copp’s Hill, say. I have been there and you might be.

Foremother, your name is the boat that brought you.

Pretend I see it in the stone, with a gruesome cherub.

Children come with thin paper and charcoal to touch you.

Pretend it drizzles and a man in an ugly plastic poncho

circles the Mathers, all but sniffing the air warily.

We don’t need to pretend for this part.

There is a plaque in the grass for Increase, and Cotton.

And Samuel, dead at 78, final son, who was there

on the day when they came looking for proof.

Eighteen of them watched you and they signed to say:

the Poems specified in the following Page, were (as we verily believe)

written by Phillis, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since,

brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa

and the abolitionists cheered at the blow to Kant

the Negroes of Africa have by nature no feeling that rises above the trifling

and the enlightened ones bellowed at the strike against Hume

no ingenious manufacturers amongst them, no arts, no sciences

Pretend I was there with you, Phillis, when you asked in a letter to no one:

How many iambs to be a real human girl?

Which turn of phrase evidences a righteous heart?

If I know of Ovid may I keep my children?

Pretend that on your grave there is a date

and it is so long before my heroes came along to call you a coon

for the praises you sang of your captors

who took you on discount because they assumed you would die

that it never ever hurt your feelings.

Or pretend you did not love America.

Phillis, I would like to think that after you were released unto the world,

when they jailed your husband for his debts

and you lay in the maid’s quarters at night,

a free and poor woman with your last living boy,

that you thought of the Metamorphoses,

making the sign of Arachne in the tangle of your fingers.

And here, after all, lay the proof:

The man in the plastic runs a thumb over stone. The gray is slick and tough.

Phillis Wheatley: thirty-one. Had misery enough.

Eve L. Ewing is the author of “1919,” the “Ironheart” series, “Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side” and “Electric Arches.” She is a professor at the University of Chicago.

⬤ Aug. 30, 1800

Fiction by Barry Jenkins

In 1800, Gabriel Prosser, a 24-year-old literate blacksmith, organized one of the most extensively planned slave rebellions, with the intention of forming an independent black state in Virginia. After other enslaved people shared details of his plot, Gabriel’s Rebellion was thwarted. He was later tried, found guilty and hanged.

As he approached the Brook Swamp beneath the city of Richmond, Va., Gabriel Prosser looked to the sky. Up above, the clouds coalesced into an impenetrable black, bringing on darkness and a storm the ferocity of which the region had scarcely seen. He may have cried and he may have prayed but the thing Gabriel did not do was turn back. He was expecting fire on this night and would make no concessions for the coming rain.

And he was not alone. A hundred men; 500 men; a thousand men had gathered from all over the state on this 30th day of August 1800. Black men, African men — men from the fields and men from the house, men from the church and the smithy — men who could be called many things but after this night would not be called slaves gathered in the flooding basin armed with scythes, swords, bayonets and smuggled guns.

One of the men tested the rising water, citing the Gospel of John: “For an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water: whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had.” But the water would not abate. As the night wore on and the storm persisted, Gabriel was overcome by a dawning truth: The Gospel would not save him. His army could not pass.

Gov. James Monroe was expecting them. Having returned from his appointment to France and built his sweeping Highland plantation on the periphery of Charlottesville, Monroe wrote to his mentor Thomas Jefferson seeking advice on his “fears of a negro insurrection.” When the Negroes Tom and Pharoah of the Sheppard plantation betrayed Gabriel’s plot on a Saturday morning, Monroe was not surprised. By virtue of the privilege bestowed upon him as his birthright, he was expecting them.

Gabriel Prosser was executed Oct. 10, 1800. Eighteen hundred; the year Denmark Vesey bought his freedom, the year of John Brown’s and Nat Turner’s births. As he awaited the gallows near the foot of the James River, Gabriel could see all that was not to be — the first wave of men tasked to set fire to the city perimeter, the second to fell a city weakened by the diversion; the governor’s mansion, James Monroe brought to heel and served a lash for every man, woman and child enslaved on his Highland plantation; the Quakers, Methodists, Frenchmen and poor whites who would take up with his army and create a more perfect union from which they would spread the infection of freedom — Gabriel saw it all.

He even saw Tom and Pharoah, manumitted by the government of Virginia, a thousand dollars to their master as recompense; a thousand dollars for the sabotage of Gabriel’s thousand men. He did not see the other 25 men in his party executed. Instead, he saw Monroe in an audience he wanted no part of and paid little notice to. For Gabriel Prosser the blacksmith, leader of men and accepting no master’s name, had stepped into the troubled water. To the very last, he was whole. He was free.

Barry Jenkins was born and raised in Miami. He is a director and writer known for his adaptation of James Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk” and “Moonlight,” which won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Photo illustration by Jon Key. House: Sergey Golub via Wikimedia. Landscape, right: Peter Traub via Wikimedia.

⬤ Jan. 1, 1808

Fiction by Jesmyn Ward

In 1808, the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves went into effect, banning the importation of enslaved people from abroad. But more than one million enslaved people who could be bought and sold were already in the country, and the breaking up of black families continued.

The whisper run through the quarters like a river swelling to flood. We passed the story to each other in the night in our pallets, in the day over the well, in the fields as we pulled at the fallow earth. They ain’t stealing us from over the water no more. We dreamed of those we was stolen from: our mothers who oiled and braided our hair to our scalps, our fathers who cut our first staffs, our sisters and brothers who we pinched for tattling on us, and we felt a cool light wind move through us for one breath. Felt like ease to imagine they remained, had not been stolen, would never be.

That be a foolish thing. We thought this later when the first Georgia Man come and roped us. Grabbed a girl on her way for morning water. Snatched a boy running to the stables. A woman after she left her babies blinking awake in their sack blankets. A man sharpening a hoe. They always came before dawn for us chosen to be sold south.

We didn’t understand what it would be like, couldn’t think beyond the panic, the prying, the crying, the begging and the screaming, the endless screaming from the mouth and beyond. Sounding through the whole body, breaking the heart with its volume. A blood keen. But the ones that owned and sold us was deaf to it. Was unfeeling of the tugging the children did on their fathers’ arms or the glance of a sister’s palm over her sold sister’s face for the last time. But we was all feeling, all seeing, all hearing, all smelling: We felt it for the terrible dying it was. Knowed we was walking out of one life and into another. An afterlife in a burning place.

The farther we marched, the hotter it got. Our skin grew around the rope. Our muscles melted to nothing. Our fat to bone. The land rolled to a flat bog, and in the middle of it, a city called New Orleans. When we shuffled into that town of the dead, they put us in pens. Fattened us. Tried to disguise our limps, oiled the pallor of sickness out of our skins, raped us to assess our soft parts, then told us lies about ourselves to make us into easier sells. Was told to answer yes when they asked us if we were master seamstresses, blacksmiths or lady’s maids. Was told to disavow the wives we thought we heard calling our names when we first woke in the morning, the husbands we imagined lying with us, chest to back, while the night’s torches burned, the children whose eyelashes we thought we could still feel on our cheeks when the rain turned to a fine mist while we stood in lines outside the pens waiting for our next hell to take legs and seek us out.

Trade our past lives for new deaths.

Jesmyn Ward is the author of “Sing, Unburied, Sing,” which won a National Book Award. She was a 2017 MacArthur fellow. Photo illustration by Jon Key. Landscape: Peter Traub via Wikimedia.

⬤ July 27, 1816

A poem by Tyehimba Jess

In 1816, American troops attacked Negro Fort, a stockade in Spanish Florida established by the British and left to the Black Seminoles, a Native American nation of Creek refugees, free black people and fugitives from slavery. Nearly all the soldiers, women and children in the fort were killed.

They weren’t headed north to freedom —

They fled away from the North Star,

turned their back on the Mason-Dixon line,

put their feet to freedom by fleeing

further south to Florida.

Ran to where ’gator and viper roamed

free in the mosquito swarm of Suwannee.

They slipped out deep after sunset,

shadow to shadow, shoulder to shoulder,

stealthing southward, stealing themselves,

steeling their souls to run steel

through any slave catcher who’d dare

try stealing them back north.

They billeted in swamp mud,

saw grass and cypress —

they waded through waves

of water lily and duckweed.

They thinned themselves in thickets

and thorn bush hiding their young

from thieves of black skin marauding

under moonlight and cloud cover.

Many once knew another shore

an ocean away, whose language,

songs, stories were outlawed

on plantation ground. In swampland,

they raised flags of their native tongues

above whisper smoke

into billowing bonfires

of chant, drum and chatter.

They remembered themselves

with their own words

bleeding into English,

bonding into Spanish,

singing in Creek and Creole.

With their sweat

forging farms in

unforgiving heat,

never forgetting scars

of the lash, fighting

battle after battle

for generations.

Creeks called them Seminole

when they bonded with renegade Creeks.

Spaniards called them cimarrones,

runaways — escapees from Carolina

plantation death-prisons.

English simply called them maroons,

flattening the Spanish to make them

seem alone, abandoned, adrift —

but they were bonded,

side by side,

Black and Red,

in a blood red hue —

maroon.

Sovereignty soldiers,

Black refugees,

self-abolitionists, fighting

through America’s history,

marooned in a land

they made their own,

acre after acre,

plot after plot,

war after war,

life after life.

They fought only

for America to let them be

marooned — left alone —

in their own unchained,

singing,

worthy

blood.

Tyehimba Jess is a poet from Detroit who teaches at the College of Staten Island. He is the author of two books of poetry, “Leadbelly” and “Olio,” for which he received the 2017 Pulitzer Prize. Photo illustration by Jon Key. Cypress: Ron Clausen via Wikimedia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earth's History in Blood Tournaments (2019-2194)

In the year 2130, mankind had accomplished one of its greatest achievements: Planetary Colonization. Planets and moons once thought inhospitable became thriving Utopias, thanks to the technological wonders and scientific advancements of the Golden Era. With the colonial cities finally constructed, Earth had launched only a tiny fraction of its population to fill its new homes for the rapidly expanding human race.

Prior to the colonization of our star system, most of the continents had united under single-rule governments. All of Europe became the E.K. (European Kingdom), a constitutional monarchy. Forged from a war waged over unity, the tiny continent was united into a strong kingdom under the rule of King Vincent II. All of North America had become the United Sovereignty of the Americas, shortened to U.S.A., making it the largest democratic country in the entire world. The continent, known as Asia, was torn into three parts. To the north, Russia reformed into the U.S.S.R. To the center of the continent, China had taken over many of its neighboring countries to form the People’s Republic of Asia (P.R.A.). To the south, India became the second home of the Emperor of the United Arabic Empire. Though considered the second smallest nation, this empire touched from the shores of the Mediterranean to the blue waters of the Pacific.

It didn’t stop there. In the year 2133, the United Sovereignty led the charge to help the third world nations to follow the world power’s example. United by a past filled with strife and struggle, Africa went from a place of poverty and starvation to a power house of industry. The vast islands of the Pacific were united to form the Federation of Oceania (F.O.), becoming the largest nation on Earth in miles. As a sign of peace, the United Sovereignty turned Hawaii and its Pacific territories over to the Federation. South America, however, fell under the dictatorial rule of a single man. Power hungry, Viceroy Fernandez slaughtered millions of protesters and rebels alike in order to unite his continent under a single banner. This new nation, forged in the blood of so many, became known as the Viceroyalty of South America, or V.S.A. for short.

This was seen as a problem to the other powers. Under the direction of Pope Jeremiah II, the newly reformed Knights Templar became the world’s sole police force. Under the urgency of the United Nations, the Treaty of Budapest was signed to ensure that the new super nations would work together rather than waging war for territory. It also stated that war in general was banned, and would be punished with invasion from the other nations. The treaty went on further to ban all nuclear weapons from construction and demanded all nations to turn over their warheads to be disarmed.

When whole continents came under these powers and with the treaty signed, people thought that humanity had finally found peace. Earth flourished, with many new cures and technologies once thought impossible in the past. It appeared that Mother Nature had been defeated. However, she had one more trick up her sleeve - total war.

When the summer of 2135 approached its end, most of the countries had finally finished building passenger spaceships called the “Gallions”, in order to send thousands of people to the outer colonies. As a sign of peace, most of the countries had all gathered their Gallions together to launch them simultaneously. On November 22, 2135, the U.S.S.R. and the P.R.A. had launched an assault on all the ships as they were leaving the surface of the Earth. At 20,000 feet above ground level, millions of people fell to their deaths from the burning wreckage. Their justification for this atrocity? The conditions of the Treaty of Budapest.

The Great Continental War had officially began. The U.S.A., the E.K., the F.O., and the Knights Templar had formed an alliance together to destroy the U.S.S.R. and the P.R.A. For the third time in Earth’s history, the whole world was at war with each other.

At the start, it was only five nations that had gone to war. But as time passed on, more and more countries had joined in the fight. The newly formed Antarctic Republic (A.R.) had seen that the U.S.A. was in a harsh struggle to win this war. They had noticed that almost all of the E.K. had been invaded, and the F.O. was very close to surrender. Even the Knights Templar were on their last leg, having lost so many sons and daughters to the carnage. In the year 2138, the A.R. entered the war on the side of the allies after an assassination attempt made by the Soviets.

This war was different from the others in the history of the world. There were three sides to this one, with the third side was the Kingdom of Africa and the United Arabic Empire. They were on most of the war fronts, and treated the battlefields as if they were mere playgrounds. They may had come into the war later than the others, but they were the two most threatening armies the world had ever seen. Whole cities, towns, and villages would be annihilated by advancing tanks and the screaming sounds of incoming mortar fire.

The original engineers that were launched for the construction of the planetary colonies saw that there was no going back to Earth, so they decided to populate what was to be the colonists’ home. The people of those colonies had decided to focus on their survival rather than Earth’s, and they thrived while blood continuously was shed on their home planet. They had erected huge domes and constructed giant cities, never minding the war that carried on. While they were busy making technological discoveries and exploring the vast unknown of the universe, their home world seemed doomed to its own destruction.

In the year of 2142, the U.S.S.R. and the P.R.A. had surrendered. The allies had won again, but the lives lost in both the tragedy that sparked the war and the war itself, were far too costly for any celebration. The war had dragged on for a bloody addition of eight years, ending finally in 2150. Only one billion people remained on the face of the Earth when the smoke had cleared. Almost all human life had been destroyed by famine, disease, and war.

As the world was busy trying to salvage what they could from the ashes of the war, a single man rose to fame after having developed technology that would help piece the world back together. His name was Doctor Vance Kyne, the head scientist and successful developer of the first human genetic modifications. For years, he had found cures for diseases, discovered new elements, and rebuilt thousands of destroyed cities. But after having discovered the Garden of Eden during the war, Dr. Kyne made a strange and dark ascent to power through what he called his “Blood Tournaments”. It quickly became a popular sport throughout the many nations. Coliseums were constructed all over the world to host the carnage of games that consisted of single matches, team fights, and endless waves of any enemy pounding on a number of players. The only countries who did not participate in the games were the four original allied nations: the U.S.A., the E.K., the F.O., and the A.R.

In the years that followed, the outer colonies changed completely. The once bare harsh soils now housed hundreds of thousands of crops and homes.

As time passed, the U.S.A. and the E.K. became closer. Eventually, their relationship as allies became a brother-like closeness. The king of the E.K. and the U.S.A.’s president both signed a pact of friendship, showing the world that at any moment’s notice, they will defend their allies to the death. The president of the A.R. also became a stronger ally of the U.S.A. They, too, joined in the signing of the pact, making them a trio of allies. The premier of the F.O. took notice of this, and decided to align herself with the allies, for the benefit of both her people and vast country.

On April 16th, 2165, President White of the United Sovereignty of the Americas, President Andrews of the Antarctic Republic, King Vincent II of the European kingdom, and Premier Young of the Federation of Oceania all signed a pact of brotherhood -a pact never before seen- to show the world that peace can be achieved when greed and pride are not at mind when signing a treaty.

Years have passed since then, and countless smaller wars have been waged. Lines drawn in the sand by the powers that fought on against each other. Over time, humanity’s numbers slowly climbed up to a reasonable number. But as humanity began to grow again, so did the evil in this world.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorcerery History & Culture in The Maghreb in the BDRP Universe

In which eight months of McKala’s worldbuilding, research, and bullshitting culminate in this

History

Magicks in the Maghreb (Northwest Africa) have always been stigmatized, dating back to even before French and English colonialism in the region. However, the stigma attached to them intensified under colonialism. Colonial oppressors tapped into the existing mystery and distrust surrounding magicks to further suppress them. A magick community under fire from both colonizers and the colonized was ideal in the age of European colonialism of Africa, Asia, and The Americas. Similar models of targeted, brutal oppression of magicks of invaded lands have been noted in historical documents from the Sasanian, Carthaginian, and Roman Empires.

Pre-colonial opinions of magicks ranged from distrusting tolerance to codified oppression. It should be noted that the first recorded targeted killing of magicks appeared in documents unearthed in Cape Bon (Watan el-kibli) from the Greco-Punic Wars, dated at around 300 B.C. It tells of the wives of Carthaginian soldiers killed in battle in Sicily killing a sorcerer couple who rivaled with their commanding officer, believing them to have cursed their husbands.

Magicks were subject to system of oppression under the Roman Empire, however, this was only really enforced in the cities. Outlying towns and villages, and the nomadic tribes at the time, operated on their own rules as long as they stayed out of the Romans’ way. Some were more lax, some were more draconian. The Romans themselves were friendly to sorcery. However, oppressing the sorcerers in conquered territory was vital to squashing dissent.

The next several hundred years, under the Vandals and the Byzantine Empire, magicks lived in a constant cycle of freedom, oppression, freedom, oppression. It varied from leader to leader.

By 705, the Islamic Conquests had taken over all of modern-day Tunisia. This period provided a degree consistency for magicks. Some Caliphates were harsher than others, however, much of this period is regarded as the Golden Age of Magicks in Tunisia and much of the Maghreb. Caliphates of this period thought it was to their advantage to negotiate with magicks rather than oppressing and slaughtering them. Alliances with magicks proved wise in several documented battles. Tensions were recorded throughout this time period, but generally, magicks could live in peace in often segregated communities.

The early Islamic era came to an end when the Shia Islamic Fatimid Caliphate departed to their newly conquered territories in Egypt leaving the Zirid dynasty to govern in their stead. Normans from Sicily raided the east coast of Ifriqiya for the first time in 1123. After some years of attacks, in 1148 Normans under George of Antioch conquered all the coastal cities of Tunisia: Bona (Annaba), Sfax, Gabès, and Tunis. By the thirteenth-century, the Golden Age of magicks in Tunisia was solidly over, as they were oppressed from all groups in the area blaming them for tensions with each other, plagues, anything that could justify hatred of magicks.

Under the Ottoman Empire, as the Eyalet of Tunis (1574–1705) and the Beylik of Tunis (1705–1881), Tunisia saw another period of mellowing in magick-mundus relations. However, this was hardly a repeat of the Golden Age. Restrictions on magicks were heavy, prison time and forced servitude were common, but it is interesting to note that the death sentence for magic use introduced in 1280 was lifted in 1610, after falling out of enforcement around the 1520s.

Tensions were pervasive in the lives of magicks, especially sorcerers who did not have the escape that fairies and were-folk often did. In the last hundred years of the Ottoman Empire’s reign over the region, laws became increasingly more restrictive, anti-magick violence saw a steady spike, and when Tunisia became a French Protectorate in 1881, it escalated.

As colonists usually did, the French tightened restrictions on magicks in their holdings in Africa. Though Tunisia gained independence in 1956, the effects of French colonialism linger - and for Tunisian magicks, it isn’t just the language they left behind.

The oppression continued through the 20th century, through all of Ben Ali’s regime until his ousting during the Arab Spring, and has continued under a democratic Tunisia.

The High Council

Across three countries - Tunisia, Libya, and Algeria, and some outstanding regions - a High Council of sorcerers has existed since before artificial colonial borders were drawn. The Council acts as a governing body, and clear rules for how a sorcerer is to conduct themselves to be granted herd protection are in place. One of these rules is that protecting the community must not come at the cost of rolling back peace progress. Education and peace-making efforts are their favored weapon against danger caused by ignorance-born hatred.

However, this is not always strongly enforced. The Council often neglects to denounce sorcerers unless it brings problems onto the community. Sorcerers that react with violence covertly to defend the community, are often not scolded.

Sorcerer Culture & Practices

Sorcerer culture in the Maghreb is distinct from sorcerer culture in other parts of the world due to the flip-flopping of the sub-group’s safety. While periods of oppression or enjoying basic rights didn’t just switch overnight, the memory of difficult periods of their history remained alive in good times through oral storytelling, and what historical records were kept.

There is generally less competition between sorcerers than in some other parts of the world, as there is a strong sense of community among Maghrebi sorcerers. During the era of European colonization of the region, Maghrebi sorcerers often viewed ethnic European sorcerers as more of the “out group” than, say, werewolves or fairies from the Maghreb. European sorcerers were seen as agents of the colonizers, and viewed as, ultimately, more loyal to them. Attitudes toward foreign sorcerers didn’t really begin to shift until the 1980s.

Since it has typically been unwise to wear one’s magic on their sleeve, any evidence of being a sorcerer must be easily disguisable.

Tunisian sorcerers of all genders favor daggers as wands. Daggers can be plain or ornate, hand crafted by the individual, or passed down the generations. They can be easily hidden in large pockets, under modern dresses and t-shirts, and within traditional clothing. Algerians and Libyans generally follow the same practice, with regional or personal alternatives. Moroccan sorceresses often wear bracelets that function as their wand.

Grimoires written in Tunisia are rare and highly valuable. Tunisian sorcerers are often forced to memorize everything from what reagents look and feel like, to complicated multi-page spells, without ever having the luxury of reading or writing them down. It is dangerous to be found with writing pertaining to sorcery. While it is not legally punishable by death, sorcerers do fall victim to mob sentencing; legally, there can be prison time.

Because it is impossible for any one person to memorize the whole world of magic inside their one brain, sorcerers are not educated by the standard Master-Apprentice system.

Rather, the community educates apprentices together and everybody brings their unique skills to the table. Master sorcerers still call those under their tutelage apprentices, but they are almost never an apprentice’s sole Master. It would not be uncommon for a relatively young Master sorcerer, say, in their late thirties, to mention having had a dozen or more apprentices. If a Master helps teach a young sorcerer that is one of five siblings, then they probably also helped teach the other four.

Perhaps the most unique aspect of Maghrebi sorcerer culture, is their use of sign language. Maghrebi Sorcerer Sign is a sign language unique to the sorcerer community, and is mutually unintelligible from Libyan Sign Language, Tunisian Sign Language Algerian Sign Language, and Moroccan Sign Language alike. It also predates the existence of any of these modern sign languages. Deaf and Hearing sorcerers use MSS on a daily basis.

There are sorcerers who only know how to cast certain spells nonverbally, solely using MSS for that spell. MSS is the collective term used to describe what is better described as a collective of localized signed conlangs. There is no official linguistic research done on MSS - naturally, as it is dangerous to reveal oneself as a sorcerer - but it is known that sorcerers from different regions, let alone countries, may have communication hurdles if they try to solely communicate using MSS.

Sorcerers across the region, however, have a second method of secret communication. There is a secret spoken language as well. Similar to the use of Polari in the United Kingdom, it is an argot meant to prevent outsiders from understanding the conversation. The language - best known as Ahk’hdi - is also used in other neighboring parts of Africa - as far as Ethiopia.

Ahk’hdi traces its origins back to the 11th century. It comes from a mixture of Mediterranean Lingua Franca, Amazigh languages (primarily Kabyle and Shilha), Arabic, Amharic, and Ottoman Turkish. Ahk’hdi is full of Arabic, Amharic, Turkish, and broadly Romance words that are given a similar treatment to English words in back slang, and French words in verlan. Like MSS, Ahk'hdi does differ from region to region, however, Ethiopian sorcerers, Tunisian sorcerers, and Algerian sorcerers can easily communicate together in Ahk'di with only occasional slips into a more widely known lingua franca.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

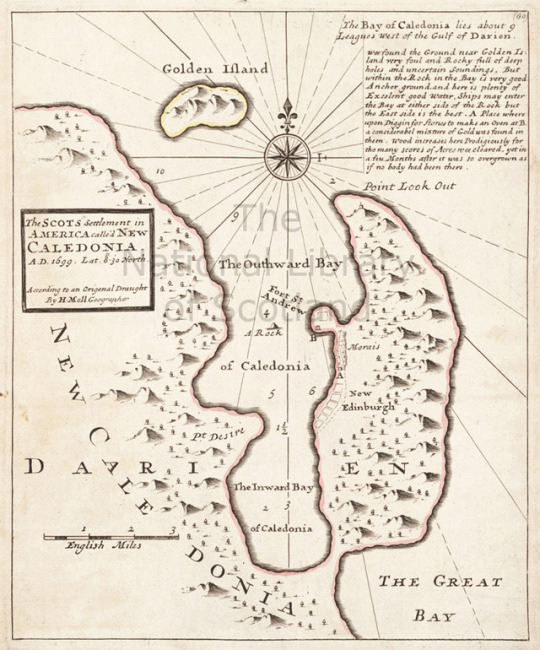

On June 26th 1695 the company which undertook the Darien Scheme was formed.

I know there will be some of you out there that are unaware of what Darien was, so I will try and give a wee rundown of the project.

ome have said: ‘The Darien venture was the most ambitious colonial scheme attempted in the 17th century…The Scots were the first to realise the strategic importance of the area…” Whilst others claimed: “They were plain daft to try… It was disaster. They never had a chance.” T’is for you to decide!

William Paterson, a Scot who’s other major claim to fame was the foundation of the Bank of England, was born in Tinwald in Dumfriesshire in 1658. He made his first fortune through international trade, travelling extensively throughout the America’s and West Indies.

On July 12th, 1698 five ships carrying 1,200 eager colonists left the Port of Leith in Scotland to a rapturous send-off. Most of the ill-fated emigrants did not know where they were going and did not find out until the sealed orders were opened at Madeira, but they were brimming with enthusiasm anyway.

A voyage of three months took them across the Atlantic to a harbour on the mangrove-studded Caribbean coast of Panama. On November 3rd, they took formal possession of their new territory, confidently naming it Caledonia and laying the foundations of the settlement of New Edinburgh. But it all went horribly wrong. Hundreds died of fever and dysentery before the colony was abandoned.

The idea was to establish a colony in Darien, open to ships of all countries, and to carry the cargoes of the Atlantic and the Pacific across the narrow isthmus of Panama, cutting out the long voyage around Cape Horn. Holding the key to the trade of both oceans, the colony would be hugely profitable and would make Scotland one of the richest nations on the globe.

The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies was authorised by the Scottish Parliament, over the years it has been given the name Darien Scheme of Project. It was meant to be a rival to the East India Company, but powerful interests in London did not want a competitor and obstacles were put in the new institution’s way. So fierce was resentment at this treatment by the English that thousands of Scots put their own money into the enterprise. Fervent national pride was aroused and a crowd cheered to the echo as the ships – Caledonia, St Andrew, Unicorn, Dolphin and Endeavour – sailed from Leith. Scores of stowaways who hoped to go along had to be ejected tearfully from the ships before sailing.

The first passenger rightfully on board was William Paterson, with his wife and son, neither of whom would survive the expedition. Many of the others would not survive either. The promoters had failed to allow for the Darien climate, the insuperable difficulties of transporting cargoes through mosquito-infested tropical jungle and the fact that the Spanish considered the territory their own and were not about to tolerate intruders.

Already on the voyage across the Atlantic the expedition’s leaders had started to quarrel among themselves. Once landed, the settlers were treated kindly by the local natives, who enjoyed flying the cross of St Andrew gaily on their canoes, but the Scots were desperately short of food, a prey to disease and riven by feuds. The English colonies in the West Indies and North America were forbidden to communicate with them or send them help by order of the government in London, which had its foreign policy and its relations with Spain to consider. The Spaniards were mobilising against the colony and a ship sent from the Clyde with extra supplies never arrived. In June, the exhausted survivors decided to go home. Paterson himself was now too starved and ill to persuade them otherwise. They sailed painfully back to Jamaica and New York, abandoning ship after ship on the way. Only the Caledonia finally made it back to Scotland.

Unaware of all this, a second consignment of settlers reached Darien at the end of November 1699, but the ship carrying their food supply caught fire and burned, while a Spanish fleet arrived to blockade the harbour. The enterprise was abandoned in March 1700 and a capitulation was signed with the Spaniards in pelting rain while a solitary piper played a lament. Traces of the settlement were found in 1979 at what is still called Caledonia Bay.

Scotland blamed the whole fiasco on the English. Paterson himself was bankrupt, but still believed in his scheme and tried vainly to revive it but to no avail.

Meanwhile, the Darien disaster seems to have persuaded hard-headed Scotsmen that their country could not prosper by itself, but needed access to England’s empire, and it helped to pave the way for the Act of Union between the two countries in 1707. Under the Act the investors in the Darien scheme were quietly compensated for their losses at taxpayers’ expense.

The pics are the flag the Scots created for the new colony, the map of the area, the third pic is the Frontispiece to the Company of Scotland's first volume of directors' minutes from 1696, The coat of arms at the bottom contains a rising sun to symbolise Scotland’s improving prospects. The motto Qua panditur orbis vis unita fortior means Where the world expands its united strength is stronger. The shield is made up of the saltire, with a ship, an elephant, a llama and a camel. The two supporters are an Indian and an African carrying horns of plenty to represent abundance.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interlude: The People of the Crossing

A/N: I've been hinting at some mythology/worldbuilding in the story so far that this interlude chapter may make more clear. You are totally in the right if you read this and think "god damn Keleri go write some original fiction already", but I think it also helps answer the question in canon of 1) where did humans come from? and 2) why does the pokémon world have such a long history but basic facts about pokémon seem to be poorly understood?

Sometimes it seems like humans (or pokémon?) have just arrived in the pokémon world, and other times people are said to have been there for millennia. (The DPPt games even claim, memorably, that humans and pokémon used to be the same.) Like most competing theories, I propose the answer, Por que no los dos?

Ancient pokémon (or daikaiju, "great strange beasts") are based on the giant pokémon from the first season of the anime.

x.x.x.x.x

Gaia and Terra are two planets connected by an incredible distance and none at all. An enormous amount of power is needed to break through to cross between them, but all around us are, overlaid like pages of a book, other Gaias and other Terras, and other earths yet unnamed by explorers. Humanity has always explored, looking out at land and sea and sky and the stars, and finally our gaze turned toward a new frontier, of new and unexplored planets only a breath away.

But like our ancestors striking out into the vastness of the Pacific Ocean, so too was there danger and deadly forces we could not imagine. The loss of the First Crossing, that deserted Roanoake of those early days, told us as much, and so too were the incredible discoveries of the fractured Second Crossing obtained at great cost. But the people who stayed discovered even more, who we thought were going to their doom, but instead survived in a strange land with new and indispensable allies.

And when we, the Third Crossing, arrived, they showed us how to survive and how to thrive, and how to do more than thrive: to create, for the first time in human history, a society where the vast majority are cared for and do not suffer under food or economic insecurity, where clean water, autonomy, security, and education are human rights, and freely available to everyone under the aegis of a cooperative elected government.

We had a rough start. We vowed not to repeat the sins of the past, but pain and fear got the better of us, as it always does, and as it will again—but we will always fight, and hope, that one day it will not. And the strange life forms of Gaia, these elementals with great and terrible and wonderful powers, who helped the Second Crossing survive and shortly the Third Crossing too, and all the people of Gaia united at last, protected and cared for, they showed us the way, and they will again.

On this fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Saffron City, I thank pokémon once again for putting up with humanity, and I look toward this year's crop of new trainers to learn from the past and to look toward the future, and to put your skills to the test so that they can continue to protect and serve everyone in our beautiful new world. I look forward to sharing this adventure with you. Let's go!

—Speech by Professor Maggie Druyan (Spruce I) at the Saffron City Golden Jubilee, 51 CR

x.x.x.x.x

Partial transcript of HIST202 lecture by Professor Aaron Singh (Holly III)

"The initial assays were done by drones, and the temporal anomalies weren't noticed until much later—they were smaller in magnitude—the drones would go through the breach for an hour and come back with 70 minutes of data, for instance. The First Crossing was a group of about two dozen people, survivalists and wilderness experts who would set up a base camp for the next group, due to arrive in about six months. Six months passed. Then nine. After a year, someone went back—crossing meant opening the breach, which depleted fuel that they used day-to-day, but eventually they decided to risk it—and that person, returning, found that barely a month had passed on the Terra side.

"When they returned through the breach with a rescue party, the First Crossing camp was entirely gone, with only a few scattered items long-disused and overgrown, and no trace was found of the people left there.

"The Second Crossing was better prepared: with the temporal anomalies clear, they set out with more technology and resources to fall back on, and a clearer understanding of what it meant to cross. One could come back, to resource-depleted, climate-changed Terra fairly easily, but years would pass on the Gaia side. And it still wasn't clear what had happened to the First Crossing. They were wary. But months turned into years, and they founded towns on the rich shores and rivers and scarcely had to farm, and the animals were nearly tame and unafraid of them, in a world untouched by humans since its beginning.

"But soon they found that there were more than animals on Gaia: there were monsters, lizards with fire breath and walking plants. Even as they sought to understand these wonders, the first daikaiju appeared, living hurricanes and forest fires that nearly obliterated all they had worked for, and they could guess at last what had happened to the First Crossing.

"Some returned to Terra, but others discovered the secret of befriending monsters instead of fighting them. Some learned to command armies of elementals and people, to tame the aggressive ones, and finally, to subdue the kaiju instead of running. And the Second Crossing made them their war-leaders in a world perpetually at war, their dukes and caesars.