#j. slater (interactions)

Text

@slateir: we all do things we desperately wish we could undo. / for Joey!

about the past & regret / accepting

While the end of the Shadyside curse might have let everyone else move on, if anything, Joey's gone even further into his own spiral. How could he pick himself out of that, knowing what he knows now? That he had helped make his brother into a monster when it had never been Tommy's fault. So as much as he wants to be there for his sisters, he's been even more shut down than before.

"This goes a bit beyond that, Reese," he mumbles back in response, already starting to pouring a drink. He felt he'd need it, knowing well enough that Reese wasn't going to just drop it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

silly little game ignore if you want — assign each of your moots and idol and a song!

OMG AN IDOL AS WELL?!? we're ab to have sm fun.. Thank U 4 This. also ermmm to moots i hvnt interacted w much this is j based on ur silly vibes Soz.....

@wave2love ( karma ). you dont even know how long ive been waiting to scream this for real. for an idol i'd say karma is either mingi from ateez or jisung from stray kids and for a song.. maybe 3005 by childish gambino?? bc ily bsf Wjnk 😉

@mins-fins ( isa ). ISA ISA ISAAA for an idol its hueningkai from txt FS. perhaps jeongin (skz) too though.. and for a song imo isa is really trix by slater!!! but also mayb take me home by pinkpantheress too!? isa isa isaaa ☹️

@so2uv ( sol ). SOL . sticking w my hongjoong (ateez) = sol agenda here IT MAKES SENSE TO ME!!!! but again the jaehyun (nct) is jumping out a little too. Here damn 😒 ANW FORA SONG im thinking massa by tyler, the creator or song about me by tv girl.. they j fit u in my head

@hyeoniez ( flori ). flori!!!!!! i think mayb jeonghan from svt for an idol?!!? Hmm idk. ur like a little bit silly and evil occasionally and that is so good for u bsf. Real. anw for a song its semantics by chloé silva 0 questions asked. ITS SO U IMO WHATTT

@jinkiseason ( elif ). oh erm Heyy.. for an idol sehun from exo (partly bc of the pfp and partly bc his ig feed (and him in general!?) is so unhinged and idgaf and crazy and silly and those r the vibes i get from them) and for a song wolf by exo (see unhinged idgaf crazy fun argument above). GUERAE WOLF NAEGA WOLF AWOOOO 🗣️

@samudan ( zai ). Hei . Ermm . purely vibes watch me do this in 0.2 seconds.. for an idol xiaojun (wayv/nct) and for song nemonade by p1harmony!!! i got some lemons 4 u 부숴 네 기준 기준....

@cinnajun ( cinna ). lowk scared asl but Hii 😓 UMMM for an idol let me blindfold myself and spin a wheel.. ten (wayv/nct)??!??? U SEEM RLY COOL IDK.. and for a song ermm sugar rush ride by txt (also a massive stab in the dark. Yasss! 👍)

OK DONE THATS IT TBIS WAS FUN THANKNU ABAIN!!!!

#So sorry if these are crazy inaccurate and make you want to like corner me in an alleyway and beat me black and blue 😊#Igot some lemons forYou😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭#HRLSOPP

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I WOULD SHUN THE LIGHT , an independent , highly selective , private multimuse writing blog as curated by cody ( she / her , twenty4 , est ) featuring both canon and original muses based in various media. highly divergent and headcanon based / influenced , very rarely fandom based. DO NOT FOLLOW FIRST. muse list below the cut.

⁰⁰¹ˑ RULES ⁰⁰²ˑ SPOTIFY ⁰⁰³ˑ PINTEREST ⁰⁰⁴ˑ INTEREST TRACKER ⁰⁰⁵ˑ INTERACTION CALLS

ᴮᴸᴼᴳᴿᴼᴸᴸ @c4mblls ( kripke era based supernatural original character ), @stabfranchise ( scream based multimuse ), @4muck ( seasonal multimuse ).

TELEVISION.

ALARIC SALTZMAN. supernatural hunter & college occult studies professor , the vampire diaries universe. michiel huisman. request only. anti j plec.

DUMON SOYLEMEZ. vampire bad boy , the vampire diaries universe. alperen duymaz. always active. anti j plec.

ETHAN CHANDLER. bloodthirsty werewolf & gunslinger extraordinaire , penny dreadful. josh hartnett & jensen ackles. request only.

FINN MIKAELSØN. the daggered original , the vampire diaries universe. matthew czuchry. always active. anti j plec.

HENRIK MIKAELSØN. the fallen but never forgotten , the vampire diaries universe. louis partridge. semi active. anti j plec.

MIECZYSLAW ' STILES ' STILINSKI. the nogitsune host , teen wolf. thomas weatherall. semi active. anti j davis.

PUGSLEY ADDAMS. the mortal at nevermore , the addams family & wednesday. xolo mariduena. always active.

SALEM SABERHAGEN. familiar to the anti christ , the chilling adventures of sabrina. emilien vekemans & joshua colley. request only.

SEFA SOYLEMEZ. the heroic vampire , the vampire diaries universe. deniz can aktas. always active. anti j plec.

ZIYA SOYLEMEZ. the mysterious ' uncle ' , the vampire diaries universe. sukru ozyildiz. always active. anti j plec.

FILM.

ASHLEY ' ASH ' WILLIAMS. the reluctant hero , the evil dead. bruce campbell. always active.

SAMUEL ' SAM ' MCDONALD. the werewolf expert , ginger snaps. kris lemche & logan shroyer. semi active.

THOMAS ' TOMMY ' SLATER. boring virgin boyfriend , fear street. mccabe slye. semi active.

LITERATURE.

DORIAN GRAY. immortal playboy , penny dreadful & the picture of dorian gray. jonathan bailey & reeve carney. always active.

JONTHAN HARKER. the reluctant vampire hunter , dracula & penny dreadful. ben barnes. always active.

FAIRYTALES.

ADAM ' THE BEAST ' DUBOIS. the narcissistic prince , descendants & beauty and the beast. louis partridge & michiel huisman. request only.

EUGENE ' FLYNN RIDER ' FITZHERBERT. the isle thief , descendants & tangled. jacob elordi & milo ventimiglia. request only.

VIDEO GAMES.

ETHAN WINTERS. the father , resident evil. milo ventimiglia. always active.

COMIC BOOKS.

BRUCE WAYNE. the batman , dc comics. jensen ackles. semi active.

JASON TODD. the red hood , dc comics. drew starkey. semi active.

JOHN CONSTANTINE. the hellblazer , dc & vertigo comics. ebon moss bachrach. always active.

1 note

·

View note

Text

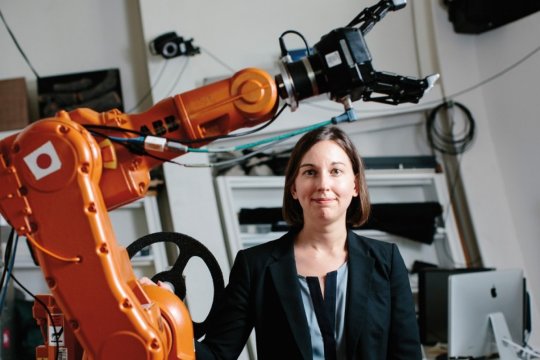

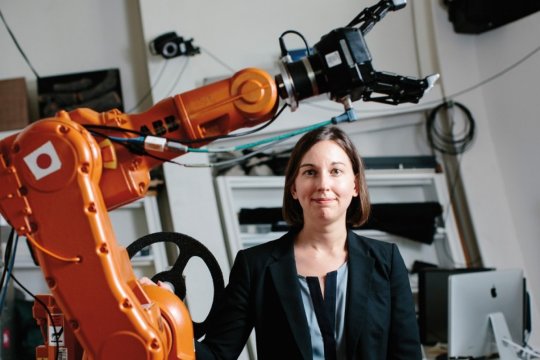

Julie Shah named head of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/julie-shah-named-head-of-the-department-of-aeronautics-and-astronautics/

Julie Shah named head of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Julie Shah ’04, SM ’06, PhD ’11, the H.N. Slater Professor in Aeronautics and Astronautics, has been named the new head of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro), effective May 1.

“Julie brings an exceptional record of visionary and interdisciplinary leadership to this role. She has made substantial technical contributions in the field of robotics and AI, particularly as it relates to the future of work, and has bridged important gaps in the social, ethical, and economic implications of AI and computing,” says Anantha Chandrakasan, MIT’s chief innovation and strategy officer, dean of the School of Engineering, and the Vannevar Bush Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

In addition to her role as a faculty member in AeroAstro, Shah served as associate dean of Social and Ethical Responsibilities of Computing in the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing from 2019 to 2022, helping launch a coordinated curriculum that engages more than 2,000 students a year at the Institute. She currently directs the Interactive Robotics Group in MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab (CSAIL), and MIT’s Industrial Performance Center.

Shah and her team at the Interactive Robotics Group conduct research that aims to imagine the future of work by designing collaborative robot teammates that enhance human capability. She is expanding the use of human cognitive models for artificial intelligence and has translated her work to manufacturing assembly lines, health-care applications, transportation, and defense. In 2020, Shah co-authored the popular book “What to Expect When You’re Expecting Robots,” which explores the future of human-robot collaboration.

As an expert on how humans and robots interact in the workforce, Shah was named co-director of the Work of the Future Initiative, a successor group of MIT’s Task Force on the Work of the Future, alongside Ben Armstrong, executive director and research scientist at MIT’s Industrial Performance Center. In March of this year, Shah was named a co-leader of the Working Group on Generative AI and the Work of the Future, alongside Armstrong and Kate Kellogg, the David J. McGrath Jr. Professor of Management and Innovation. The group is examining how generative AI tools can contribute to higher-quality jobs and inclusive access to the latest technologies across sectors.

Shah’s contributions as both a researcher and educator have been recognized with many awards and honors throughout her career. She was named an associate fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) in 2017, and in 2018 she was the recipient of the IEEE Robotics and Automation Society Academic Early Career Award. Shah was also named a Bisplinghoff Faculty Fellow, was named to MIT Technology Review’s TR35 List, and received an NSF Faculty Early Career Development Award. In 2013, her work on human-robot collaboration was included on MIT Technology Review’s list of 10 Breakthrough Technologies.

In January 2024, she was appointed to the first-ever AIAA Aerospace Artificial Intelligence Advisory Group, which was founded “to advance the appropriate use of AI technology particularly in aeronautics, aerospace R&D, and space.” Shah currently serves as editor-in-chief of Foundations and Trends in Robotics, as an editorial board member of the AIAA Progress Series, and as an executive council member of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

A dedicated educator, Shah has been recognized for her collaborative and supportive approach as a mentor. She was honored by graduate students as “Committed to Caring” (C2C) in 2019. For the past 10 years, she has served as an advocate, community steward, and mentor for students in her role as head of house of the Sidney Pacific Graduate Community.

Shah received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in aeronautical and astronautical engineering, and her PhD in autonomous systems, all from MIT. After receiving her doctoral degree, she joined Boeing as a postdoc, before returning to MIT in 2011 as a faculty member.

Shah succeeds Professor Steven Barrett, who has led AeroAstro as both interim department head and then department head since May 2023.

#000#2022#2023#2024#Administration#Aeronautical and astronautical engineering#aeronautics#aerospace#ai#ai tools#Alumni/ae#amp#applications#approach#artificial#Artificial Intelligence#automation#autonomous systems#board#Boeing#book#career#career development#Collaboration#collaborative#college#Community#computer#Computer Science#Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL)

0 notes

Text

Digital Facets: The impact of Snapchat filters onto the world of beauty filters on Instagram and Tiktok

The introduction of Snapchat filters was the turning point in the history of digital self-expression. Introduced in 2011, these filters first provided users with entertaining overlays and effects to improve their images and videos shared within the app (Statista, 2022). However, it was the introduction of face recognition technology in 2015 that truly transformed the landscape of Snapchat filters (Lee & Sung, 2016). This technology allows users to apply filters that dynamically change their face characteristics in real time, such as adding animal ears and noses or smoothing skin. Snapchat filters immediately became a cultural phenomenon, with millions of users worldwide seeing them as a creative and enjoyable method to enhance their look in images and videos.

Snapchat filters had an extensive impact in the world of beauty filters, shaping beauty standards and trends on other social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. As Snapchat users became accustomed to seeing themselves with digitally enhanced features, they developed a yearning to emulate these changed looks. As a result, Instagram and TikTok added their own versions of beauty filters to their platforms, allowing users to improve their look right within the applications (Statista, 2022). These beauty filters provided a variety of effects, mostly focus on smoothing skin and erasing facial imperfections, as well as applying cosmetics and adjusting face proportions, similar to the features popularized by Snapchat filters. The incorporation of beauty filters into Instagram and TikTok helped to normalize digitally changed looks, establishing modern beauty standards and influencing how users present themselves online.

Research has shown that beauty filters have an adverse effect on users' self-image and physical satisfaction, particularly among young women (Tiggemann & Slater, 2014; Perloff, 2014). Exposure to idealized pictures on social media has been linked to increased body dissatisfaction and low confidence. The availability of extensively filtered photographs may contribute to excessive beauty standards, forcing users to set themselves up to impossible aspirations and be dissatisfied with their natural appearance. Furthermore, the normalization of digitally changed appearances on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok may contribute to a society in which authenticity is overwhelmed by digitally modified images. As a result, though beauty filters empower users with a method of creative expression and self-improvement online, they raise crucial considerations regarding the impact of digital technology on body image and self-esteem in today's digital age.

References:

Lee, J., & Sung, Y. 2016, 'Exploring the Impact of Snapchat on Self-Presentation and Social Interaction', Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(6), 336-340.

Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. 2014, 'NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls', International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(6), 630-643.

Perloff, R. M. 2014, 'Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research', Sex Roles, 71(11-12), 363-377.

Statista 2022, 'Number of daily active Snapchat users worldwide from 2014 to 2022', https://www.statista.com/statistics/545967/snapchat-app-dau/.

Statista 2022, 'Number of monthly active Instagram users worldwide from January 2013 to September 2021', https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/.

Statista 2022, 'Number of daily active TikTok users in the United States from January 2021 to March 2022', https://www.statista.com/statistics/1095186/tiktok-us-dau/.

0 notes

Text

WEEK 3: HOW TUMBLR IS USED BY DISENGAGED AND UNDERPRIVELEGED GROUPS?

Direct comparisons between Tumblr, Reddit, and Instagram may be difficult because each platform has an own user base and set of features. Based on the data at my disposal, Instagram has a greater user base than Tumblr and Reddit. But every platform has a particular function and supports various kinds of interactions and information. Tumblr is renowned for emphasizing creative expression and blogging.

The site is useful for communication study because it provides a large amount of room for users to add textual context to the selfies they submit. Hashtags are widely used to create communities, and shared blogs may be handled collaboratively with others (Renninger, 2015). The visibility of posts within these hashtags is independent of the number of followers, the user’s usual participation within the community, or the number of reactions to the post, thus allowing for a wider range of voices to be heard (Renninger, 2015). Users have the opportunity to like, comment, or reblog content to interact with the post and its creator. These interactions are summarized in a single notes number. Tumblr prevents trolling and bad replies by concealing the more detailed reactions below the summary (Cavalcante, 2018).

Tumblr, which was founded as a hybrid of social networking sites and conventional weblogs, creates the foundation for a vibrant and varied feminist community. Conversely, women who share sexually suggestive photographs on social media sites like Facebook or Instagram typically face backlash and become targets of victimization and "slut-shaming" (Miguel, 2016). Tumblr distinguished itself from these platforms until its policy change in 2018 due to its acceptance of NSFW (Not Safe for Work) content (Renninger, 2015; Tiidenberg & Cruz, 2015). Therefore, in light of earlier studies highlighting the drawbacks and hazards, the general concept of #bodypositive—creating diverse feminist spaces that enable women to discover their own beauty—had a lot of promise on Tumblr until 2018 (Cohen et al., 2019; Maddox, 2019; Sastre, 2014). Furthermore, Tumblr was seen as a platform for "emotional authenticity" and was utilized to create counterpublic spaces for progressive and underprivileged groups (Hart, 2015; Cavalcante, 2018).

Tumblr's role in activism and awareness cannot be overstated. Underprivileged groups leverage the platform to raise awareness about social issues, disseminate information, and mobilize support for various causes. It serves as a powerful tool for grassroots activism, enabling connections among like-minded individuals passionate about creating change. The visual nature of Tumblr makes it an ideal platform for artistic expression. Individuals from disengaged or underprivileged backgrounds can showcase their creative talents, whether through illustrations, photography, or writing. This not only provides an outlet for expression but also offers an opportunity for recognition within the community.

Identity exploration is another vital aspect, with users openly discussing and affirming their identities, including aspects related to gender, sexuality, and race. For marginalized groups, Tumblr becomes a space for self-discovery and acceptance, fostering conversations that may be stigmatized in mainstream society.

References

Cavalcante, A 2018, ‘Tumbling Into Queer Utopias and Vortexes: Experiences of LGBTQ Social Media Users on Tumblr’, Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 66, no. 12, pp. 1715–1735.

Cohen, R, Irwin, L, Newton-John, T & Slater, A 2019, ‘#bodypositivity: A content analysis of body positive accounts on Instagram’, Body Image, vol. 29, no. 29, pp. 47–57.

Hart, M 2015, ‘Youth Intimacy on Tumblr’, YOUNG, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 193–208.

Hillman, S, Procyk, J & Neustaedter, C 2014, ‘Tumblr fandoms, community & culture’, Proceedings of the companion publication of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing - CSCW Companion ’14.

Maddox, J 2019, ‘“Be a badass with a good ass”: race, freakery, and postfeminism in the #StrongIsTheNewSkinny beauty myth’, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 1–22.

Miguel, C 2016, ‘Visual Intimacy on Social Media: From Selfies to the Co-Construction of Intimacies Through Shared Pictures’, Social Media + Society, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 205630511664170.

Renninger, BJ 2014, ‘“Where I can be myself … where I can speak my mind” : Networked counterpublics in a polymedia environment’, New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1513–1529.

Sastre, A 2014, ‘Towards a Radical Body Positive’, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 929–943.

Tiidenberg, K & Gómez Cruz, E 2015, ‘Selfies, Image and the Re-making of the Body’, Body & Society, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 77–102.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Back to the Future, Shatner, Fillion Q&A’s Highlight FAN EXPO Portland Programming, February 17-19

From celebrity Q&As to industry, cosplay, gaming, anime and entertaining, informative sessions from all areas of pop culture, FAN EXPO Portland presents its collection of nearly 150 programing panels and meetups during the event, Friday through Sunday, February 17-19 at Oregon Convention Center. There’s truly something for every fan and every taste every hour of the show into the evening throughout all three days of the convention, right until Sunday’s 5 p.m. finish.

FAN EXPO Portland celebrity guests like Back to the Future stars Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson and Tom Wilson;Ron Perlman (“Sons of Anarchy,” Hellboy; Bruce Campbell (The Evil Dead, “Burn Notice”), Carl Weathers (“The Mandalorian,” Rocky); Gates McFadden (“Star Trek: The Next Generation”), Anthony Daniels (Star Wars franchise) and others will conduct interactive sessions with fans, headlining the thorough slate.

There are dozens of informative, entertaining panels by superstar creators as well as cosplay, gaming, trivia, film, horror and other pop culture themed sessions. Fans can review the entire event schedule at https://fanexpohq.com/fanexpoportland/schedule/. Most panels are free with event admission, and dates/times are subject to change. Just a few of the highlights include:

Friday:

12:50 p.m., Opening Ceremonies, show entrance

4 p.m., Feeling Super: Mental Health in Pop Culture, Room B121

4 p.m., My Name is Zuko: Conversation with Dante Basco, Secondary Theater

4:30 p.m., Why Portland is Weird and Why we Love it, Room B120

5 p.m., William Shatner – Where No One Has Gone Before, Main Events Stage

6 p.m., Anthony Daniels – Don't Blame Me: I’m an Interpreter, Main Events Stage

6 p.m., Women in Horror, Room B117-118

7 p.m., Portland Horror Film Festival Sneak Peek 2023, Secondary Theater

7 p.m., Sean Chandler Speaks! How To Grow A Nerdy YouTube Channel, Room B110

7:30 p.m., An Evening with the Cast of Back to the Future, Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson and Tom Wilson, Main Events Stage

8 p.m., Drink and Draw with Joe Wos - Presented By Wacom, Mox Boarding House, 1938 W Burnside, Portland

Saturday:

11 a.m., Mind the Gap: A Cosplayer’s Guide to Awesome Seams on Eva Foam Projects, Room B111-112

11 a.m., It’s Too Early for an Anime Panel, Room C123-124

11:30 a.m., Haunted History of Oregon & the Northwest with Rocky Smith, Oregon Ghost Conference, Room B120

Noon, Black 2 Da Future, Room B117-118

Noon and 3 p.m., Cosplay Red Carpet, Cosplay Area

Noon, Nolan North is so Tired of Climbing, Secondary Theater

1 p.m., Animation Showdown: X-Men vs. Batman, Room B117-118

1 p.m., Plus Ultra! The My Hero Academia Voice Actors Panel with Justin Briner and David Matranga, Secondary Theater

1 p.m., Old School Spirit Communication with Paranormal Experts Aaron Collins and June Lundgren, Room B119

1:30 p.m., Katee Sackhoff – From Starbuck to Star Wars, Main Events Stage

2 p.m., Matthew Lewis Blows it up. Boom!, Secondary Theater

2:30 p.m., Carl Weathers – From Rocky to the Mandalorian, Main Events Stage

3 p.m., Lea Thompson’s Enchantment Under the Sea, Secondary Theater

4 p.m., Bringing the Backstory with creators Jeff Davis, Nikolas P. Robinson, Adam Ross and Danger Slater, Room B119

4 p.m., Star Trek: Strange New Worlds with Anson Mount and Ethan Peck, Secondary Theater

4:30 p.m., Ron Perlman – Do it for the Club, Main Events Stage

5 p.m. Real Life Sci-Fi: Creating Tomorrow’s Tech Today, Room B119

5:45 p.m., Ethics of AI Art, Room B120

6 p.m., The FAN EXPO Portland Cosplay Exhibition, Main Events Stage

Sunday:

11 a.m., Jodi Benson – Don't Be Such a Guppy, Secondary Theater

11 a.m., The Force Experience + Kids Lightsaber Training, Family Zone

11:30 a.m., Learn to Draw Forest Friends – Cartoon Academy with Joe Wos, Family Zone

11:30 a.m., Nathan Fillion – I'm Just a Good Man, Main Events Stage

Noon, Billy West – Happy Happy Joy Joy, Secondary Theater

Noon and 2 p.m., Hogwarts Sorting Ceremony, Family Zone

Noon, Kickstarters and Comic Publishing, Room A105-106

Noon, Star Wars and Conflict Resolution, Room B121

12:30 p.m., Bruce Campbell: Who’s Laughing Now?, Main Events Stage

1:30 p.m., A Conversation with Filmmaking Legend Sam Raimi, Main Events Stage

2 p.m., Spy X Family X Anya X Yor! Voice Actor Q&A with Megan Shipman and Natalie Van Sistine, Room C123-124

2 p.m., The Super Powers of Bats, Room B121

2:30 p.m., Kids Cosplay Contest, Cosplay Red Carpet

3 p.m., Monsters Are Metaphors: How Horror Performs "Cultural Shadow Work," Room B119

3 p.m., Making History with Pop Culture, Room B121

Tickets for FAN EXPO Portland are on sale at http://www.fanexpoportland.com now, including individual single day, 3-day and Ultimate Fan Packages for adults, youths and families. VIP packages (now sold out!) include dozens of special benefits including priority entry, limited edition collectibles, exclusive items and much more.

Portland is the second event on the 2023 FAN EXPO HQ calendar; the full schedule is available at fanexpohq.com/home/events/.

0 notes

Text

Interesting Papers for Week 25, 2021

Confidence can be automatically integrated across two visual decisions. Aguilar-Lleyda, D., Konishi, M., Sackur, J., & de Gardelle, V. (2021). Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 47(2), 161–171.

From statistical regularities in multisensory inputs to peripersonal space representation and body ownership: Insights from a neural network model. Bertoni, T., Magosso, E., & Serino, A. (2021). European Journal of Neuroscience, 53(2), 611–636.

On the effect of neuronal spatial subsampling in small‐world networks. Bonzanni, M., Bockley, K. M., & Kaplan, D. L. (2021). European Journal of Neuroscience, 53(2), 485–498.

Multiple cannabinoid signaling cascades powerfully suppress recurrent excitation in the hippocampus. Jensen, K. R., Berthoux, C., Nasrallah, K., & Castillo, P. E. (2021). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(4).

Release probability increases towards distal dendrites boosting high-frequency signal transfer in the rodent hippocampus. Jensen, T. P., Kopach, O., Reynolds, J. P., Savtchenko, L. P., & Rusakov, D. A. (2021). eLife, 10, e62588.

Environment-based object values learned by local network in the striatum tail. Kunimatsu, J., Yamamoto, S., Maeda, K., & Hikosaka, O. (2021). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(4).

Dissecting the Roles of Supervised and Unsupervised Learning in Perceptual Discrimination Judgments. Loewenstein, Y., Raviv, O., & Ahissar, M. (2021). Journal of Neuroscience, 41(4), 757–765.

Molecular mechanisms within the dentate gyrus and the perirhinal cortex interact during discrimination of similar nonspatial memories. Miranda, M., Morici, J. F., Gallo, F., Piromalli Girado, D., Weisstaub, N. V., & Bekinschtein, P. (2021). Hippocampus, 31(2), 140–155.

Human subjects exploit a cognitive map for credit assignment. Moran, R., Dayan, P., & Dolan, R. J. (2021). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(4).

Prioritization in visual attention does not work the way you think it does. Ng, G. J. P., Buetti, S., Patel, T. N., & Lleras, A. (2021). Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 47(2), 252–268.

Linking metacognition and mindreading: Evidence from autism and dual-task investigations. Nicholson, T., Williams, D. M., Lind, S. E., Grainger, C., & Carruthers, P. (2021). Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 150(2), 206–220.

Neural mechanisms of visual sensitive periods in humans. Röder, B., Kekunnaya, R., & Guerreiro, M. J. S. (2021). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 120, 86–99.

Orientation Effects in the Development of Linear Object Tracking in Early Infancy. Tham, D. S. Y., Rees, A., Bremner, J. G., Slater, A., & Johnson, S. P. (2021). Child Development, 92(1), 324–334.

How do stupendous cannabinoids modulate memory processing via affecting neurotransmitter systems? Vaseghi, S., Nasehi, M., & Zarrindast, M.-R. (2021). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 120, 173–221.

Theta power and theta‐gamma coupling support long‐term spatial memory retrieval. Vivekananda, U., Bush, D., Bisby, J. A., Baxendale, S., Rodionov, R., Diehl, B., … Burgess, N. (2021). Hippocampus, 31(2), 213–220.

Layer 6 ensembles can selectively regulate the behavioral impact and layer-specific representation of sensory deviants. Voigts, J., Deister, C. A., & Moore, C. I. (2020). eLife, 9, e48957.

Using pharmacological manipulations to study the role of dopamine in human reward functioning: A review of studies in healthy adults. Webber, H. E., Lopez-Gamundi, P., Stamatovich, S. N., de Wit, H., & Wardle, M. C. (2021). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 120, 123–158.

Data-driven reduction of dendritic morphologies with preserved dendro-somatic responses. Wybo, W. A., Jordan, J., Ellenberger, B., Marti Mengual, U., Nevian, T., & Senn, W. (2021). eLife, 10, e60936.

Dysfunction of Orbitofrontal GABAergic Interneurons Leads to Impaired Reversal Learning in a Mouse Model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Yang, Z., Wu, G., Liu, M., Sun, X., Xu, Q., Zhang, C., & Lei, H. (2021). Current Biology, 31(2), 381-393.e4.

Speed modulation of hippocampal theta frequency and amplitude predicts water maze learning. Young, C. K., Ruan, M., & McNaughton, N. (2021). Hippocampus, 31(2), 201–212.

#science#Neuroscience#computational neuroscience#Brain science#research#cognition#cognitive science#neurons#neurobiology#neural networks#psychophysics#neural computation#scientific publications

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

a favorite thing of j/b is how they weren't supposed to have intimacy; not when they were "not dating", and not later; and nobody is really privy to their relationship with each other, but people and themselves and the writing like to pretend they aren't close and they had never been close, but there are little things that show they were, that they shared moments we don't know about, that they know little things about each other that nobody else did. i don't know, i just love it.

it's like they and sometimes the group or the show or the fandom tried to downplay or deny their connection, and they just... can't really do it? because it's a big part of their characters, and their arcs, and their relationship is just so instinctual, natural, organic. ugh. i miss them

same!! I have such a soft spot for their entire season 1 arc because it’s Jeff realizing that he wants to pursue a genuine friendship with Britta and her slowly realizing that she wants more and them becoming better friends throughout all of it. like the moment in Interpretive Dance where Britta realizes that she’s jealous of Slater and Jeff’s relationship and wants something like it with him?? that’s the moment I knew I was ruined. they’re the second closest pairing in the study group (Troy and Abed being number one ofc) because they spend the most time together and know each other the best because they’re so similar. and you’re so right about everyone downplaying their connection. the show stopped giving them moments together sometime around season 5, (which is funny since in season 4, Britta was dating Troy, but had more genuine moments with Jeff. like were the writers all on the same page. did anyone even know what was happening.) but their connection is still there despite everything!! I miss them too and I’m 100% positive that a Community movie would only make that worse since D*n’s too much of a coward to let the two of them interact.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

It has been a long hiatus, though to me it didn’t seem to be one. Time flies. June and July have flied by so fast, and I can’t keep up, shit things happening one after the other, and I’m still coping… But it’s a process. I’m functioning now enough to write and interact on this blog.

As I promised, this first post is a list of June releases (from June 3rd) and the reviews I found about them until now. You’re all welcome to let me know if you have a review that I forgot to add.

Since July is also over, I’m also sharing this month’s books and reviews.

As always, updating is constantly happening, if you know about a book or have a review, just let me know! 😉

Welcome back on Swift Coffee, everyone!

For the newbies (welcome 😘): if you don’t yet know what this is all about: I’m posting a list every Monday of the books that get released during the current week. I also include other people’s reviews about them! I try to do a blog hop from time to time and spread the word about this feature, but I obviously can’t find every review that’s related, so a sign that you have one would be very much appreciated! Every review is eligible that is written about a book published on the week in question, even if it was written before said week!

So… one question remains:

Would you like to join the ride?

It’s very easy!

These are the rules:

To be featured, you don’t have to do anything else, but to leave a comment below this post, or contact me by any other way, and let me know you have a review. A link to it makes it easier, but if you only say your review comes out on x day of the week, that’s okay as well, I’ll watch out for it! Following me is not a must, but I appreciate it very much, if you do! 🙂

I continuously update this post according to your infos/comments, and I share it again every time I’ve made an update.

The book you reviewed don’t have to be from the list here, if it’s not listed, but published this week, I’ll add the book, too!

You can also send me a review for next week, because these posts are scheduled! 😉

Books Published in June:

‘After the End’ by Clare Mackintosh mystery/thriller

‘All the Missing Girls’ by Megan Miranda mystery

‘A Merciful Promise’ by Kendra Elliot mystery/romantic suspense

‘A Nearly Normal Family’ by M.T. Edvardsson, Rachel Willson-Broyles (Translation) mystery/thriller

‘Ayesha at Last’ by Uzma Jalaluddin romance

‘Beyond Āsanas: The Myths and Legends behind Yogic Postures’ by Pragya Bhatt, Joel Koechlin (Photographer)

‘Bound to the Battle God’ by Ruby Dixon fantasy/romance

‘Briar and Rose and Jack’ by Katherine Coville middle grade

‘Bunny’ by Mona Awad horror

‘City of Girls’ by Elizabeth Gilbert historical fiction

‘Close to Home’ by Cate Ashwood M M romance

‘Dear Wife’ by Kimberly Belle mystery/thriller

‘Dissenter on the Bench: Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Life and Work’ by Victoria Ortiz non-fiction/middle grade

‘Fleishman Is in Trouble’ by Taffy Brodesser-Akner contemporary

‘Five Midnights’ by Ann Dávila Cardinal horror

‘Fix Her Up’ by Tessa Bailey romance

‘Fixing the Fates: A Memoir’ by Diane Dewey non-fiction

‘Ghosts of the Shadow Market’ YA fantasy

‘Gun Island’ by Amitav Ghosh cultural/India/historical fiction

‘If Only’ by Melanie Murphy

‘Just One Bite’ by Jack Heath mystery/thriller

‘Like a Love Story’ by Abdi Nazemian YA/LGBT

‘Magic for Liars’ by Sarah Gailey fantasy/mystery

‘More Than Enough: Claiming Space for Who You Are (No Matter What They Say)’ by Elaine Welteroth non-fiction

‘Mrs. Everything’ by Jennifer Weiner historical fiction

‘Mostly Dead Things’ by Kristen Arnett contemporary/LGBT

‘Natalie Tan’s Book of Luck and Fortune’ by Roselle Lim contemporary/romance

‘On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous’ by Ocean Vuong poetry

‘Rapture’ by Lauren Kate YA fantasy

‘Recursion’ by Blake Crouch science fiction

‘Searching for Sylvie Lee’ by Jean Kwok mystery

‘Somewhere Close to Happy’ by Lia Louis romance

‘Sorcery of Thorns’ by Margaret Rogerson fantasy

‘Storm and Fury’ by Jennifer L. Armentrout fantasy

‘Summer of ’69’ by Elin Hilderbrand historical fiction

‘Sweet Tea and Secrets’ by Joy Avon cozy mystery

‘Teeth in the Mist’ by Dawn Kurtagich horror

‘The Accidental Girlfriend’ by Emma Hart romance

‘The Bookshop on the Shore’ by Jenny Colgan contemporary/women’s fiction

‘The First Mistake’ by Sandie Jones thriller

‘The Friends We Keep’ by Jane Green women’s fiction

‘The Friend Zone’ by Abby Jimenez contemporary/romance

‘The Girl in Red’ by Christina Henry fantasy/horror

‘The Haunted’ by Danielle Vega horror

‘The Holiday’ by T.M. Logan

‘The July Girls’ by Phoebe Locke mystery/thriller

‘The Last House Guest’ by Megan Miranda mystery/thriller

‘The Most Fun We Ever Had’ by Claire Lombardo contemporary/literary fiction

‘The New Achilles’ by Christian Cameron historical fiction

‘The Red Labyrinth’ by Meredith Tate fantasy

‘The Resurrectionists’ by Michael Patrick Hicks horror

‘The Rest of the Story’ by Sarah Dessen YA contemporary/romance

‘Ollie Oxley and the Ghost: The Search for Lost Gold’ by Lisa Schmid middle grade

‘The Space Between Time’ by Charlie Laidlaw

‘The Stationery Shop’ by Marjan Kamali historical fiction

‘The Summer Country’ by Lauren Willig historical fiction

‘They Called Me Wyatt’ by Natasha Tynes mystery

‘This Might Hurt a Bit’ by Doogie Horner YA

‘Time After Time’ by Lisa Grunwald historical/science fiction

‘Waiting for Tom Hanks’ by Kerry Winfrey contemporary/romance

‘We Have Always Been Here: A Queer Muslim Memoir’ by Samra Habib non-fiction

‘We Were Killers Once’ by Becky Masterman mystery/thriller

‘Where The Story Starts’ by Imogen Clark women’s fiction

‘Wicked Fox’ by Kat Cho YA fantasy

‘Wild and Crooked’ by Leah Thomas YA contemporary/LGBT

‘Wolf Rain’ by Nalini Singh paranormal romance

Reviews:

‘Sorcery of Thorns’ by Stephanie at Between Folded Pages

‘The Rapture’ at Book Bound

‘The Resurrectionists’ by Jen at Shit Reviews of Books

‘The Haunted’ by Kris at Boston Book Reader

‘The Friends We Keep’ by Vicky at Women in Trouble Book Blog

‘This Might Hurt a Bit’ by Amanda at Between the Shelves

‘Wild and Crooked’ by Amanda at Between the Shelves

‘The Haunted’ by Mandy at Book Princess Reviews

‘We Were Killers Once’ by Vicky at Women in Trouble Book Blog

‘Five Midnights’ by Sian at Sci-fi & Scary

‘Wolf Rain’ by Corina at Book Twins Reviews

‘Just One Bite’ by Berit at Audio Killed the Bookmark

‘Where the Story Starts’ by Anjana at Superfluous Reading

‘The Red Labyrinth’ by Anjana at Superfluous Reading

‘Fixing the Fates’ by Anjana at Superfluous Reading

‘Gun Island’ by Anjana at Superfluous Reading

‘If Only’ by Anjana at Superfluous Reading

‘Sweet Tea and Secrets’ by Rekha at The Book Decoder

‘Storm and Fury’ by Claire at bookscoffeeandrepeat

‘The New Achilles’ by Zoé at Zooloo’s Book Diary

‘Time After Time’ by Ashley at Ashes Books and Bobs

‘Recursion’ by Lilyn G at Sci-fi & Scary

‘The Space Between Time’ by Rekha at The Book Decoder

‘The Rumor’ by Vicky at Women in Trouble Book Blog

‘The Search for the Lost Gold’ by Lilyn G at Sci-fi & Scary

‘They Call Me Wyatt’ by Jen at Shit Reviews of Books

‘After the End’ by Linda at Linda’s Book Bag

‘Beyond Asanas’ by Shashank at Wonder’s Book Blog

‘The July Girls’ by Nicola at Short Book and Scribes

‘We Have Always Been Here’ by Kristin at Kristin Kraves Books

‘Close to Home’ by T. J. Fox

‘Dissenter on the Bench’ by Taylor at Tays Infinite Thoughts

‘Bound to the Battle God’ by Corina at Book Twins Reviews

‘Briar and Rose and Jack’ by Briana at Pages Unbound

‘Teeth in the Mist’ at Lori’s Bookshelf Reads

‘All the Missing Girls’ by Celine at Celinelingg

‘The Holiday’ by Zoe at Zooloo’s Book Diary

‘The July Girls’ by Joanna at Over the Rainbow Book Blog

‘More Than Enough’ by Jessica at Jess Just Reads

‘Somewhere Close to Happy’ at Jess Just Reads

‘The Accidental Girlfriend’ by Tijuana at Book Twins Reviews

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

Books Published in July:

‘Along the Broken Bay’ by Flora J. Solomon historical fiction

‘A Stranger on the Beach’ by Michele Campbell mystery/thriller

‘A Whisker In The Dark’ by Leighann Dobbs cozy mystery

‘Dark Age’ by Pierce Brown science fiction

‘Depraved’ by Trilina Pucci romance/erotica

‘Deserve to Die’ by Miranda Rijks thriller

‘Drummer Girl’ by Ginger Scott YA romance

‘False Step’ by Victoria Helen Stone mystery/thriller

‘Girls Like Us’ by Cristina Alger mystery/thriller

‘Gods of Jade and Shadow’ by Silvia Moreno-Garcia fantasy/historical fiction

‘Good Guy’ by Kate Meader romance

‘Gore in the Garden’ by Colleen J. Shogan cozy mystery

‘How to Hack a Heartbreak’ by Kristin Rockaway romance

‘Last Summer’ by Kerry Lonsdale contemporary

‘Life Ruins’ by Danuta Kot audiobook/mystery

‘Lock Every Door’ by Riley Sager mystery/thriller

‘Maybe This Time’ by Kasie West contemporary

‘Never Have I Ever’ by Joshilyn Jackson mystery/thriller

‘Never Look Back’ by Alison Gaylin mystery/thriller

‘Nightingale Point’ by Luan Goldie

‘Reclaimed by Her Rebel Knight’ by Jenni Fletcher historical romance

‘Resist’ by K. Bromberg romance

‘Salvation Day’ by Kali Wallace science fiction

‘Season of the Witch’ by Sarah Rees Brennan YA fantasy

‘Sisters of Willow House’ by Susanne O’Leary

‘Spin the Dawn’ by Elizabeth Lim fantasy

‘That Long Lost Summer’ by Minna Howard

‘The Betrayed Wife’ by Kevin O’Brien mystery/thriller

‘The Bookish Life of Nina Hill’ by Abbi Waxman contemporary/romance

‘The Chain’ by Adrian McKinty thriller

‘The Gifted School’ by Bruce Holsinger contemporary fiction

‘The Golden Hour’ by Beatriz Williams historical fiction

‘The Guy on the Right’ by Kate Stewart NA romance

‘The Last Book Party’ by Karen Dukess historical fiction

‘The Marriage Trap’ by Sheryl Browne thriller

‘The Merciful Crow’ by Margaret Owen fantasy

‘The Miraculous’ by Jess Redman middle grade

‘The Need’ by Helen Phillips horror/thriller

‘The Nickel Boys’ by Colson Whitehead historical fiction

‘The Rogue King’ by Abigail Owen paranormal romance

‘The Seekers’ by Heather Graham mystery

‘The Silent Ones’ by K.L. Slater thriller

‘The Storm Crow’ by Kalyn Josephson fantasy

‘The Wedding Party’ by Jasmine Guillory romance

‘Three Women’ by Lisa Taddeo non-fiction/feminism

‘To Be Devoured’ by Sara Tantlinger horror

‘Truly Madly Royally’ by Debbie Rigaud YA romance

‘Under Currents’ by Nora Roberts romance

‘War’ by Laura Thalassa fantasy/romance

‘Whisper Network’ by Chandler Baker mystery/thriller

‘Wilder Girls’ by Rory Power YA horror/mystery

A fantastic review of…

‘Reclaimed by her Rebel Knight’ by Demetra at Demi Reads

‘The Merciful Crow’ by Clarissa at Clarissa Reads It All

‘The Bookish Life of Nina Hill’ at Flavia the Bibliophile

‘The Merciful Crow’ by Kaleena at Reader Voracious

‘The Guy On the Right’ by Astrid at The Bookish Sweet Tooth

‘False Step’ by Jordann at The Book Blog Life

‘The Guy On the Right’ by Angela at Reading Frenzy Book Blog

‘Reclaimed by Her Rebel Knight’ by Joules at Northern Reader

‘Depraved’ by Demetra at Demi Reads

‘Never Have I Ever’ by Steph AT Steph’s Book Blog

‘Reclaimed by Her Rebel Knight’ by Jennifer C. Wilson

‘That Long Lost Summer’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘Sisters of Willow House’ by Joanne at Portobello Book Blog

‘A Whisker in the Dark’ by Berit at Audio Killed the Bookmark

‘The Rouge King’ by Ashley at Falling Down the Book Hole

‘Good Guy’ by Astrid at The Bookish Sweet Tooth

‘Drummer Girl’ by Astrid at The Bookish Sweet Tooth

‘The Need’ by T. J. Fox

‘The Seekers’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘The Silent Ones’ by Steph at StefLoz Book Blog

‘Resist’ by Tijuana at Book Twins Reviews

‘Reclaimed by Her Rebel Knight’ by Jess Bookish Life

‘Sisters of Willow House’ by Joanna at Over the Rainbow Book Blog

‘How To Hack a Heartbreak’ by Corina at Book Twins Reviews

‘Somebody Else’s Baby’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘Life Ruins’ by Amanda at mybookishblogspot

‘The Miraculous’ by Chris at Plucked from the Stacks

‘The Betrayed Wife’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘Salvation Day’ by Lilyn G at Sci-fi & Scary

‘The Marriage Trap’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘The Chain’ at Jess Just Reads

‘To Be Devoured’ by Sam and Gracie at Sci-fi & Scary

‘Truly Madly Royally’ by Olivia at The Candid Cover

‘Season of the Witch’ by Jill at Jill’s Book Blog

‘Gore in the Garden’ by Rekha at The Book Decoder

‘Never Look Back’ by Berit at Audio Killed the Bookmark

‘Wilder Girls’ by Kathy at Pages Below the Vaulted Sky

‘Deserve to Die’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘Sisters of Willow House’ by Shalini at Shalini’s Books and Reviews

‘Sisters of Willow House’ by Berit at Audio Killed the Bookmark

‘Nightingale Point’ by Amanda at mybookishblogspot

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 16%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

See these beautiful covers? *.*

Which are your favorites?

I’m so happy to be here with you bookish guys again!!

Don’t forget to let me know if you have a review!

Oh, and in the near future comes another post with the releases of the beginning of August! You can send me reviews for that post, as well.

Have a wonderful time!

Hugs 🙂

I’m back! – A Master List of Book Releases of June and July + Reviews! It has been a long hiatus, though to me it didn't seem to be one. Time flies.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

@lcveblossomed: “ do i look like the kind of person who could give advice ? ” (alice to joey)

unsolved starters / accepting

Joey responds with a scoff, "Do I look like the kind of person who asks for advice?" Normally, he'd steer clear of the survivors from Nightwing, but...well, he's not exactly sober when he approaches Alice. "I don't know, I just...you were with him when it happened, right?" He's not sure what he wants from this conversation, but he can't help but ask.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Review of: The Umbrella Academy (Season 1)

You know, if I’m going to have this basically-a-blog, I might as well put it to use, right? Always wanted to do reviews, let’s give it a shot.

The Umbrella Academy

Developed by: Steve Blackman and Jeremy Slater

Based on the Graphic Novels by: Gerard Way and Gabriel Bá

Starring: Ellen Page, Tom Hopper, David Castañeda, Emmy Raver-Lampman, Robert Sheehan, Aidan Gallagher, Mary J. Blige, Cameron Britton and John Magaro.

Score: 7/10

Watch If You Like: Dysfunctional Families, deconstructions of superhero tropes (aimed mainly at the X-Men, but there’s some shots at Batman there too), quirky comicbook stuff.

Content Warnings: Semi-frequent Gore, Child Abuse, Torture, Domestic Abuse, use of Stuffed Into The Fridge, Bury Your Gays and Not Blood Siblings romance.

Spoilers below the cut.

So, yeah, this show. Binged it in a few days a couple days ago. It’s pretty okay. Definitely some things in it that would turn a lot of people off. Not fantastically well-written, but competently.

It follows the six surviving members of the Umbrella Academy, a school/teenage superhero team from the early 2000s as they deal with the loss of their leader/adoptive father. He was an abusive asshole, so they mostly don’t miss him besides the Golden Child of the group, Luther.

As they grew up, the kids all went their separate ways, and their father’s death brings them all back together. Initially there are only five of them, but then Number Five, a member of their team that went missing in their teenage years, appears out of a time portal. He’s there to save the world from an upcoming apocalypse, though he only initially confides this in Vanya, the families’ only non-superpowered child. While this happens, Luther attempts to lead an investigation into their father’s death, as he suspects foul play.

The Good:

Fun character interaction.

Decently well-developed characters.

Not one, but two enticing mysteries that intertwine and clash at points.

Good, clear rules to the setting that develop as it goes on.

Quality jukebox soundtrack with some interesting choices.

Decent depictions of various types of abusive relationships.

The Bad:

The aforementioned fridging of Detective Patch in Episode 4, solely to give personal motivation to Diego.

...motivation which he drops at points to serve the plot. There are several moments that will leave you scratching your head and wondering why the characters are either going against character or forgetting to use their powers.

Torture is used an effective means of information gathering.

There’s a developing romantic relationship between a pair of adoptive siblings, which is a little creepy.

Klaus’ time travel jaunt to acquire a dead mlm love interest feels kinda rushed, plus even if the Dave is dead before we meet him, it still counts as Bury Your Gays. You could argue that Klaus’ power (speaking to the dead) kinda negates that, but he never interacts with Dave post-death, despite that being a major motivation of his character. C’mon, not one quiet moment before the end with the two of them interacting?

Ending on a cliffhanger. I know you’re a Netflix show and you’re guaranteed two seasons, but because your cliffhanger is a time travel trip, you leave us with absolutely no closure.

So yeah. Definitely not for everybody, but if you can get past it’s flaws, it’s a fun little show with some room to improve.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Project 3 Refletion

After the presentation I took some time to reflect on my work. 3D modeling is not an easy medium and for a week’s project I believe i achieved good results. When it comes to combining he realities of digital and physical, it takes quite a workload to successfully achieve. I am increasingly more interested in this concept of “remixing” technologies and art forms to create a world of mixed realities.

After some self reflection I can say that in these past 2 months the amount of hours per day in which I have no connection at all are far scarce that they were last year. From the moment we wake up to the moment we sleep we are always connected. In the past this kind of connection has usually been met with negative connotations as many of us would hear reprimands from our elders with the classical interjections “you spend too long glued to that screen”. However with the global pandemic we have turned this once negative outlook into a necessary source for interpersonal connection, education, entertainment and even work.

Mixing the realities could be considered escapism but it can also be integration. Immersing ourselves fully into the digital world we now live in everyday life by bringing elements of the digital sphere into the physical realm with the help of AR technologies, Mapping and 3D printing, we can integrate elements from the digital sphere with the physical realm and blur the lines that separate us from this world that lives inside our pockets.

MR specifically can be a powerful tool of learning and professional training, in ways that VR alone could not. By remixing the realities we can make both students and audiences engaged in the experience, as well as develop their learning through interaction. (Pan, Z. Cheok, A. Yang, H. Zhu, J, Shi, J. ,2006)

This developing medium can benefit us both in academic and scientific ways but also in creating new art experiences and new ways to conduct immersive narratives to the audience.

Slater,M and Sanchez-Vives, M.V. ,present multiple uses for VR technologies that can evolve the human experience and learning to new levels, from Science,Education and Surgical Training to social and cultural experiences, the uses are limitless and possibly what an optimized future might strive for.

References:

Slater, M. and Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2016) ‘Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality’, Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 3. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2016.00074.

Pan, Z. Cheok, A. Yang, H. Zhu, J, Shi, J. (2006) 'Virtual reality and mixed reality for virtual learning environments', Computers & Graphics, 30 (1), pp. 20-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2005.10.004.

0 notes

Text

Robert Bennett, The Psychopharmacological Thriller: Representations of Psychotropic Pills in American Popular Culture, 37 Literature & Medicine 166 (2019)

Psychotropic medications have increasingly become a staple of modern life, with one in five adults now taking some kind of psychiatric pill. Consequently, our voracious consumption of psychotropic pills has begun to raise significant questions about how psychopharmacology radically transforms—modifies, manipulates, molds, and manufactures—human identities one pill at a time. Moreover, this biochemical micro-engineering of the human self has begun to emerge as one of contemporary culture's major preoccupations as new narratives—in memoir, literature, television, film, and popular music—have begun to explore not only mental illnesses themselves but also the medications we take to treat those illnesses. In this newly emergent genre, which I call the psychopharmacological thriller, new narrative techniques are being developed to probe the inner neurochemistry of the human brain, how medications alter that neurochemistry, and the wide-ranging questions raised by this brave new proliferation of psychopharmacology in everyday life.

With today's pharmacology, no one needs to suffer with feelings of exhaustion and depression.

—Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), The Sopranos

Nothing a little lithium couldn't cure.

—Lisa (Illeana Douglas), Stir of Echoes

Widely praised as resembling "nothing else on television," HBO's The Sopranos (1999–2007) narrates the infamous deeds of a notorious mob family whose lives overflow with murders, drug deals, carjackings, fraud, money laundering, racketeering, extortion, gambling, and prostitution.1 And yet, the series does not open in medias res, during a ruthless firefight between heavily armed hitmen or even in some seedy New Jersey strip club, but instead with Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) simply walking into a nondescript psychiatrist's office, seeking professional help for a recent panic attack (fig. 1). No oneoff gag or mere comic juxtaposition between grisly mob violence and touchy-feely psychoanalysis, as in the films Analyze This (1999) and Analyze That (2002), Tony's "talk therapy" sessions with Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) arguably provide the series' central narrative framing device, using the analyst's chair to reveal the depths of its protagonist's character, to explore his broader relationships with family and friends, to simultaneously dissect both criminal and suburban life, and ultimately to probe the very psyche of America itself. In the end, Tony Soprano may be just a run-of-the-mill gangster, but as an analysand he is almost unparalleled in American culture. Not since Woody Allen's Alvy Singer (Annie Hall 1977) has a character been so thoroughly—and entertainingly—psychoanalyzed on screen.

Figure 1. Opening scene of The Sopranos. Tony Soprano visiting his psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi. The Sopranos, HBO, season 1, episode 1, 1999.

The Sopranos' grand psychoanalytic narrative, however, is itself shadowed by a second psychopharmacological one. For Dr. Melfi treats Tony not only with talk therapy but also with psychotropic medications, most notably Prozac. So in certain respects the series plays itself out on a subterranean level, through a biochemical subplot, maybe even as what could be termed a psychopharmacological thriller. Always in the background, this subplot is constantly exploring how the complex psychology of the human mind interacts with the hardwired biochemistry of the human brain. From this psychiatric perspective, The Sopranos is not simply a psychoanalytic exploration of the ideas inside Tony's head, or even the feelings inside his heart; it is also an examination of what's inside his medicine cabinet. In the very first episode Dr. Melfi throws down a psychopharmacological gauntlet, brazenly declaring that "with today's pharmacology, no one needs to suffer with feelings of exhaustion and depression."2 And thus begins the unfolding battle between the Don's deeply troubled, but not so easily cured, psyche and the shrink's vast, but less than invincible, arsenal of psychotropic medications. As in many other texts about mental health, however, this psychopharmacological subplot, the drama of Tony's pills, often seems to pass unnoticed.

The near invisibility of Tony's pills is commonplace in critical discussions of how cultural texts represent mental health. While Glen O. Gabbard and Krin Gabbard's Psychiatry and the Cinema, David J. Robinson's Reel Psychiatry: Movie Portrayals of Psychiatric Conditions, and Danny Wedding and Mary Ann Boyd's Movies & Mental Illness: Using Films to Understand Psychopathology all develop excellent analyses of how mental health and psychoanalysis have been depicted in cultural texts, especially in film, much less attention has been paid to how cultural texts represent psychiatric treatment with psychotropic medications. For example, Wedding and Boyd's Movies & Mental Illness includes only a few short paragraphs on medications per se, rarely making anything more than brief, sporadic comments about how the character "Mr. Jones did not respond to treatment with Haldol" or the film I'm Dancing As Fast As I Can (1982) "demonstrates some of the problems associated with overreliance on Valium" before generally concluding that the "treatment most often used" in films is "individual psychotherapy."3 Likewise, Gabbard and Gabbard's Psychiatry and the Cinema chronicles more than 400 films which depict psychiatrists treating individuals with various psychiatric problems, developing in-depth analysis of portrayals of psychoanalysis but saying very little about medication. And Robin-son's Reel Psychiatry repeats this pattern: It contains exhaustive analyses of how films represent everything from schizophrenia, Cyclothymia, and PTSD to Somatoform disorders, Borderline Personality Disorder, and dissociative amnesia, but it offers few insights about Valium, Thorazine, or Prozac. Similarly, Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin's The Novel Cure: From Abandonment to Zestlessness: 751 Books to Cure What Ails You includes short descriptions of how numerous mental states—from clinical anxiety and depression to quotidian apathy and stress—are depicted in literature, but few entries on how treatments of these conditions are also depicted. As self-proclaimed bibliotherapists, Berthoud and Elderkin contend that literature can insightfully depict, and even help to cure, various psychological conditions, but their comprehensive treatment of 751 books says next to nothing about how these books portray psychiatric medication.

In contrast with the well-developed literature on depictions of psychology, critical evaluations of pharmacology are just beginning to emerge. Lorenzo Servitje's recent (2018) Literature and Medicine article, "Of Drugs and Droogs: Cultural Dynamics, Psychopharmacology, and Neuroscience in Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange," and Isabelle Travis's "Is Getting Well Ever an Art?: Psychopharmacology and Madness in Robert Lowell's Day by Day" stand out as two of the few articles to explore how the relationship between neuroscience and psychopharmacology plays out in works of art. For example, Servitje develops a new reading of A Clockwork Orange which demonstrates how "psychopharmacology plays a central role in the novel's plot," while Travis points out how Lowell's poetry describes himself as both a "thorazined fixture" and "tamed by Miltown," thereby demonstrating how he conceptualizes his psychopharmacological treatment as something of a "chemical straightjacket."4 My own study Pill (Bloomsbury, 2019) is arguably the first book-length exploration of how a wide range of cultural texts depict not only mental health conditions but also their treatment with psychotropic medications.

Although largely absent from the critical conversation about film, these psychotropic drugs are now widely discussed in the medical community. They play a prominent role in current discussions of mental health—from Allen Frances's cautionary Saving Normal: An Insider's Revolt against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life to Peter R. Breggin's outright anti-pill diatribe Toxic Psychiatry: Why Therapy, Empathy, and Love Must Replace the Drugs, Electroshock, and Biochemical Theories of the "New Psychiatry." And certainly, there have been many personal memoirs of people's firsthand experiences with psychiatric medications—from Lauren Slater's Prozac Diary (1998) and Elizabeth Wurtzel's Prozac Nation (1994) to Stephen Elliott's The Adderall Diaries (2009). Nevertheless, very little mention has been made of how these medications are also represented in fictional art. This is in spite of the fact that psychotropic medications have played a role in literary and cinematic texts from Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) to The Sopranos, and they are now beginning to play an ever-increasing role not only in real life, but also in contemporary memoirs, literature, films, and television shows about mental health.

Consequently, in our brave, new psychopharmacological age, more careful attention needs to be paid—both in life and in art—to the neurochemistry of the brain and how that neurochemistry is altered through psychotropic medication. For, as Nikolas Rose argues, it is "now at the molecular level that human life is understood, at the molecular level that its processes can be anatomized, and at the molecular level that life can now be engineered."5 Moreover, the recent emergence of new cultural depictions of psychotropic pills and their neurochemical impact on characters' brains—the emerging genre of the psychopharmacological thriller—has begun to refocus cultural inquiry on this molecular level, essentially providing a new model of human subjectivity located more firmly in the hardwired neurocircuitry of the brain than in the more humanistically oriented softwiring of the mind or the psyche. As Hilary Rose and Steven Rose explain, the brain has increasingly been redefined "as the centre of the self" and "persons" increasingly "reduce[d]" to their "neurons" and "synapses," transforming selfhood into what Fernando Vidal describes as "brain-hood," the "brain-self," or the "cerebral subject."6 Consequently, these new psychopharmacological thrillers increasingly depict how we are fast becoming Jean-Pierre Changeux's Neuronal Man or Joseph LeDoux's Synaptic Self.

If only it were as simple as Dr. Melfi suggests. If only Tony's suffering was "nothing a little lithium couldn't cure," as Lisa Weil (Illeana Douglas) remarks in Stir of Echoes (1999), then all he would have to do is swallow the right pill and out would come the cure, kind of like inserting a dollar bill into a Coke machine, which is essentially what Dr. Melfi's pharmacological model of the human brain implies.7 There would be no need for psychopharmacological "thrillers": no need to depict the excruciating biochemical battles raging inside human brains or the tremendous lengths to which health care professionals go to try to treat mental health disorders. The Sopranos itself might not have even needed a second season, or at least not one that included Dr. Melfi. Instead of ending Tony's suffering with modern pharmacology, however, Dr. Melfi seems only to drag him deeper into pharmaceutical quicksand, prescribing him Prozac in the first episode and Xanax in the third. By the twelfth episode, the emerging mob kingpin is taking lithium, too, and when Dr. Melfi asks him if he is "still taking the lithium," he replies, "Lithium, Prozac. When's it gonna end?"8 (fig.2).

Tony is already onto Dr. Melfi's pharmacological game, and when lithium itself produces adverse side effects, causing Tony to hallucinate a beautiful woman named Isabella (Maria Grazia Cucinotta), one begins to wonder if Dr. Melfi isn't curing Tony so much as she is pulling him down a psychopharmacological rabbit hole, turning his medicine cabinet—and his mind itself—into a psychotropic funhouse. David Healy's 2012 warning against "pharmageddon," Allen Frances's attempt to "save normal," and Peter Breggin's condemnation of toxic psychiatry have all articulated powerful critiques of the overuse and abuse of psychiatric medications in the treatment of mental illnesses, and Tony's rapidly lengthening psychotropic rap sheet seems to lend credence to their concerns about overmedicalization.

Figure 2. Tony Soprano's medicine cabinet. The Sopranos, HBO, season 1, episode 12, 1999.

But The Sopranos is only one example of the proliferating psychopharmacological thriller, in which not only a character's mental illness but also how that illness is treated with psychotropic medications occupies a central place in the text. The rising popularity of this genre is evidenced by the recent memoirs, novels, films, and television shows which explicitly explore the complexities of mental health disorders at least partly from the perspective of the psycho-tropic medications used to treat them; examples include the pitting of Prozac against depression (Prozac Nation memoir 1994, film 2001), Valium against borderline personality disorder (Girl, Interrupted memoir 1993, film 1999), pentobarbital against dissociative disorder (Frankie and Alice 2010), or Thorazine and insulin against schizophrenia (A Beautiful Mind biography 1998, film 2001). Characters' diverse battles with lithium alone occur in Mr. Jones (1993), Pi (1998), Garden State (2004), Premonition (2007), Michael Clayton (2007), The Silver Linings Playbook (novel 2008, film 2012), Homeland (2011–), and Infinitely Polar Bear (2014). Sometimes these psychopharmacological plots play out subtly, as when anonymous psych nurses dispense undefined pills to long lines of generic patients suffering from unspecified maladies (as in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest 1975), or characters with unmistakably disturbed minds take repeated trips to the medicine cabinet to self-administer some unnamed, but clearly psychotropic, medication (as in Donnie Darko 2001). Whether or not these texts specify the precise nature of each pharmaceutical conflict, taken collectively their point is clear: The psychotropic meds dispensed on any given day, day after day, play a central role in shaping the inner psychological conflicts faced by those who take them, as their psychologies and their biologies interact to play out grand psychopharmacological dramas. In each case, the biochemical conflict between a protagonist's troubled mental state and the psychopharmacological tools used to treat it ends up shaping its characters, its plot, its imagery, its emotional conflicts, its dramatic tension, and at times even its metaphysics.

And, pace Dr. Melfi, psychopharmacological thrillers almost invariably emphasize the complexities, rather than the certainties, of treating mental health disorders, depicting psychotropic medications as imperfect at best. In fact, in most cases today, both for real and for fictional patients, psychiatrists now routinely treat mental health disorders by prescribing complex combinations of medications, or psychotropic "cocktails," rather than a single pill. These cocktails are rarely static, too. Psychiatrists frequently adjust diverse amalgamations of prescriptions and dosages while their patients struggle for years, if not entire lifetimes, to manage their conditions. In Side Effects (2013), for example, Emily Taylor (Rooney Mara) is treated with Wellbutrin, Prozac, Effexor, and Ablixa, and in Gothika (2003), Chloe Sava (Penelope Cruz) is treated with Elavil, Mallorol, and Haldol. In The Silver Linings Playbook (2012), Pat Solitano (Bradley Cooper) and Tiffany Maxwell (Jennifer Lawrence) swap stories about being on lithium, Seroquel, Abilify, Xanax, Effexor, Klonopin, and Trazodone—a not implausible course of treatment which vividly illustrates how the simple isomorphic one-toone correlation between a single disorder and a single medication is now more the exception than the rule.

It is hyperbole, of course, but Andrew Largeman (Zach Braff), the protagonist of Zach Braff's Garden State, reveals a kernel of truth—arguably more truth than Dr. Melfi's boast—when he extends modern pharmacology's proliferation of psychotropic medication ad absurdum. Waking from a disturbing nightmare of a plane crash to find himself in a near catatonic state in a white-on-white bedroom, clearly evoking images of an asylum, Largeman lethargically rises from his bed to face his own reflection in an oversized, double-mirrored medicine cabinet which, as he slowly peels it open, reveals behind his reflected face a wall of no less than 45 prescription pill bottles. A far cry from Dr. Melfi's "no one needs to suffer," Largeman's medicine cabinet throws down its own countergauntlet, calling modern pharmacology's bluff, which—for all of its bewildering array of new designer psychotropics—still offers far fewer and less simple solutions than Dr. Melfi claims. Few images display these complexities, if not outright failures, better than Largeman's oversized, overstuffed medicine cabinet (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Andrew Largeman's medicine cabinet. Garden State, dir. Zach Braff, 2004.

What we see in Largeman's medicine cabinet has become a major preoccupation of contemporary culture: How are we to deal with the brave, new world of modern psychopharmacology, a world in which human identities are increasingly bio-engineered one pill at a time, titrated gram by gram like the soma-addicts of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World?

To Medicate or Not to Medicate: The Psychopharmacology of Nonadherence

I'd like to say one thing about lithium if you don't mind. Nobody even knows if it works.

—Cam Stuart (Mark Ruffalo), Infinitely Polar Bear

In many respects, Maya Forbes's heartwarming Infinitely Polar Bear (2014) exemplifies the psychopharmacological thriller in its simplest form, depicting—in a primarily realistic manner—Cam Stuart as an endearingly manic, happily married father of two whose life begins to unravel largely due to his struggle with bipolar disorder. In fact, Cam is literally introduced in terms of his illness as his daughter's voice opens the film, "My father was diagnosed manic depressive [i.e. bipolar] in 1967. He'd been going around Cambridge in a fake beard calling himself Jesus John Harvard."9 And, at least initially, Cam is depicted appealingly; he may be a little impulsive and quirky, but he is also fun and carefree, even ecstatically joyful, sucking the marrow of life. Consequently, his family accepts, even embraces, the eccentricities of his condition.

The film quickly shifts, however, to emphasize the darker side of Cam's illness and the serious strains it puts on his family. Keeping his daughters home from school so that they can help him "celebrate" his recent firing from his job, Cam remarks unequivocally that "Mommy's going to be so happy that I kept you out of school"—only for his bold declaration of manic freedom to be immediately followed by mommy's attempt to flee their home precisely to escape Cam's madness. When Cam rides up on a bike in nothing but a red bathing suit and a red bandanna, in winter weather no less, he does little to help his cause, sealing his fate perhaps with his hysterical outburst: "I am a man. Men like to live free. That's what we do, Maggie. To hunt and mate. That's what we do. That's why we have balls." By nightfall the police have been called to transport Cam to a psychiatric hospital, and, lovably eclectic as he may be, the film quickly reveals that behind his family's "happy" façade there is "more to it than that. There always is."

Ultimately, however, Infinitely Polar Bear isn't just about Cam's illness; it is equally about lithium, the medication that he uses to treat it, about the decisions that he makes regarding whether or not to take that medication, about the medication's side effects, and even about questioning—perhaps unreliably—the reliability of lithium itself. For while the film clearly, and correctly, suggests that lithium does mitigate, though perhaps not entirely cure, the complex condition of bipolar disorder, it never reduces lithium to a mere panacea: It never boasts that "no one need suffer" if they would just take their lithium, nor does it suggest that bipolar is "nothing a little lithium couldn't cure." On the contrary, the film repeatedly emphasizes how Cam's medication itself produces diverse side effects, constantly needs to be adjusted, and must be accompanied by careful stress and anger management, sobriety, and a healthy daily routine. Add to this the fact that many of Cam's most endearing qualities—including his creativity, his joie de vivre, his charisma, and his compassion—are perhaps difficult to disentangle from his illness and hence subside, if not disappear altogether, when he does properly take his lithium, and the situation quickly becomes murkier. Lithium does not simply cure Cam: It also makes him disappear. Every gain in stability is seemingly counterbalanced by a loss of some treasured part of himself: his spontaneity, his love of life, or his expansive sense of freedom. Given the complexity of Cam's condition, then, it is perhaps not surprising that he frequently lapses into nonadherence to his lithium regimen. It is hard for Cam to fully cure, or even manage, his illness without feeling like he is sacrificing a piece, even the best piece, of himself, making his cure at times seem worse than the illness itself. Consequently, he generally resents and resists taking his lithium, reluctant to even want to "cure" himself.

It is Cam's daughter, however, who first places Cam's medication at the front and center of the narrative, offering a variation on Dr. Melfi's "no one needs to suffer" when she suggests to Cam that if he will "stop drinking and take [his] lithium then mommy would let [him] come home." And while she correctly sums up the core of Cam's predicament, his struggles with bipolar disorder, lithium, and sobriety are depicted as interconnected trials which are far from simple. For if the plot of Infinitely Polar Bear pits the love of family, including mentally ill family, against the toll that mental illness takes on families, then the film's psychopharmacological subplot pits the power of lithium against the refusal to take it, its adverse side effects, ill-advised forms of self-medicating, and even the possibility that it simply might not work. Lithium, then, together with Cam's adherence or nonadherence to taking it, provides the film's principal barometer of Cam's progress as a character—as a husband, as a father, and as a person. When he takes the lithium he is generally more stable, though admittedly not his most vivacious self, but when he stops taking it he unravels, even explodes, though perhaps with what Jack Kerouac describes as the terrible beauty of the "mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars."10 So while lithium indisputably helps Cam manage his condition, his attraction to his other manic side frequently prompts him to refuse to take his medication. One can judge Cam's refusal as irrational from the outside, but the film repositions the viewer on the inside to see how it might feel to be forced to take a medication that so alters your personality as to make you feel like you are not yourself anymore. Perhaps the film ultimately comes down in favor of adherence, but it never ignores, or even minimizes, its costs.

Cam's nonadherence comes to a crisis when he calls Maggie at five in the morning to tell her that he stayed up all night making his daughter a flamboyantly eclectic flamenco skirt—"the most glorious skirt I've ever known," according to his daughter. When Cam adds that he doesn't need to go to sleep because he isn't tired, Maggie asks him point-blank if he is taking his lithium. He replies, "Actually, I haven't taken my lithium since you left. I find that if I take small, steady sips of beer all day I stay on even keel." So Cam is not only nonadherent to his prescribed medication, but he is also self-medicating with alcohol—a dangerous one-two punch for someone with bipolar disorder. But the central conundrum of the film is starkly presented by the fact that it is the same manic qualities, the very manifestation of his illness itself, that enables Cam to be a good, even great, father, to stay up all night frenetically sewing a fanciful and beloved dress for his daughter, while at the same time compromising both his own health and the stability of his family. Ultimately, the same things which make Cam lovable are not easily disentangled from the ones that make him mentally ill: However useful lithium may prove in treating his illness, it cannot navigate the complex biochemical networks of Cam's brain sorting out the good from the bad and stacking them each in neat little piles. Consequently, Cam's adherence or nonadherence to his lithium regimen is not presented as a choice between good and evil, between health and illness, but rather as—at least in part—a balancing act, a necessary evil, a pyrrhic victory, or even an unwinnable catch-22. Sitting at his sewing machine at 5:00 in the morning sans lithium, we see Cam simultaneously at both his best and his worst with his most loving and most unstable selves fusing into one.