#metzler

Text

Delta V, 1970. A project by German rubber and plastics manufacturer Metzler to create a targa-roof kit-car based on the VW Beetle. The prototype was presented in the US where Beetle-based kit-cars were big business but the Delta V appears to have gone no further, perhaps because of the complexity of the kit which had an estimated 10-week build time

#Delta#Delta V#Metzler#1970#kit-car#prototype#Volkswagen Beetle#rear engine#wedge design#1970s#targa#open roof

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was a mundane, unanimously supported bill on liquor taxation that saw state Sen. Machaela Cavanaugh take to the mic on the Nebraska Legislature floor last week. She offered her support, then spent the next three days discussing everything but the bill, including her favorite Girl Scout cookies, Omaha’s best doughnuts and the plot of the animated movie “Madagascar.”

She also spent that time railing against an unrelated bill that would outlaw gender-affirming therapies for those 18 and younger. It was the advancement of that bill out of committee that led Cavanaugh to promise three weeks ago to filibuster every bill that comes before the Legislature this year — even the ones she supports.

“If this Legislature collectively decides that legislating hate against children is our priority, then I am going to make it painful — painful for everyone,” the Omaha married mother of three said. “I will burn the session to the ground over this bill.”

True to her word, Cavanaugh has slowed the business of passing laws to a crawl by introducing amendment after amendment to every bill that makes it to the state Senate floor and taking up all eight debate hours allowed by the rules — even during the week she was suffering from strep throat. Wednesday marks the halfway point of this year’s 90-day session, and not a single bill will have passed thanks to Cavanaugh’s relentless filibustering.

Clerk of the Legislature Brandon Metzler said a delay like this has happened only a couple of times in the past 10 years.

“But what is really uncommon is the lack of bills that have advanced,” Metzler said. “Usually, we’re a lot further along the line than we’re seeing now.”

In fact, only 26 bills have advanced from the first of three rounds of debate required to pass a bill in Nebraska. There would normally be two to three times that number by mid-March, Metzler said. In the last three weeks since Cavanaugh began her bill blockade, only three bills have advanced.

The Nebraska bill and another that would ban trans people from using bathrooms and locker rooms or playing on sports teams that don’t align with the gender listed on their birth certificates are among roughly 150 bills targeting transgender people that have been introduced in state legislatures this year. Bans on gender-affirming care for minors have already been enacted this year in some Republican-led states, including South Dakota and Utah, and Republican Governors in Tennessee and Mississippi are expected to sign similar bans into law. And Arkansas and Alabama have bans that were temporarily blocked by federal judges.

Cavanaugh’s effort has drawn the gratitude of the LGBTQ community, said Abbi Swatsworth, executive director of LGBTQ advocacy group OutNebraska. The organization has been encouraging members and others to inundate state lawmakers with calls and emails to support Cavanaugh’s effort and oppose bills targeting transgender people.

“We really see it as a heroic effort,” Swatsworth said of the filibuster. “It is extremely meaningful when an ally does more than pay lip service to allyship. She really is leading this charge.”

Both Cavanaugh and the conservative Omaha lawmaker who introduced the trans bill, state Sen. Kathleen Kauth, said they’re seeking to protect children. Cavanaugh cited a 2021 survey by The Trevor Project, a nonprofit focused on suicide prevention efforts among LGBTQ youth, that found that 58% of transgender and nonbinary youth in Nebraska seriously considered suicide in the previous year, and more than 1 in 5 reported that they had attempted it.

“This is a bill that attacks trans children,” Cavanaugh said. “It is legislating hate. It is legislating meanness. The children of Nebraska deserve to have somebody stand up and fight for them.”

Kauth said she’s trying to protect children from undertaking gender-affirming treatments that they might later regret as adults. She has characterized treatments such as hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery as medically unproven and potentially dangerous in the long term — although the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychiatric Association all support gender-affirming care for youths.

Cavanaugh and other lawmakers who support her filibuster effort “don’t want to acknowledge the support I have for this bill,” Kauth said.

“We should be allowed to debate this,” she said. “What this is doing is taking the ball and going home.”

Nebraska’s unique single-chamber Legislature is officially nonpartisan, but it is dominated by members who are registered Republicans. Although bills can win approval with a simple majority in the 49-seat body, it takes 33 votes to overcome a filibuster. The Legislature is currently made up of 32 registered Republicans and 17 registered Democrats, but the slim margin means that the defection of a single Democrat could allow Republicans to pass whatever laws they want.

Democrats have had some success in using filibusters, which burn valuable time from the session, delay votes on other issues and force lawmakers to work longer days. Last year, conservative lawmakers were unable to overcome Democratic filibusters to pass an abortion ban or a law that would have allowed people to carry concealed guns without a permit.

Cavanaugh said she has taken a page from the playbook of Ernie Chambers — a left-leaning former legislator from Omaha who was the longest-serving lawmaker in state history. He mastered the use of the filibuster to try to tank bills he opposed and force support for bills he backed.

“But I’m not aware of anyone carrying out a filibuster to this extent,” Cavanaugh said. “I know it’s frustrating. It’s frustrating for me. But there is a way to put an end to — just put a stop to this hateful bill.”

Chambers praised Cavanaugh’s “perseverance, gumption and stamina to fight as hard as she can using the rules” to stand up for the marginalized, adding, “I would be right there fighting with her if I were still there.”

Speaker John Arch has taken steps to try to speed the process, such as sometimes scheduling the Legislature to work through lunch to tick off another hour on the debate clock. And he noted that the Legislature will soon be moving to all-day debate once committee hearings on bills come to an end later this month.

But even with frustration growing over the hobbled process, the Republican speaker defended Cavanaugh’s use of the filibuster.

“The rules allow her to do this, and those rules are there to protect the voice of the minority,” Arch said. “We may find that we’re passing fewer bills, but the bills we do pass will be bigger bills we care about.”

Chambers said this is a sign that Cavanaugh’s efforts are working. Typically, the Speaker will step in and seek to postpone the bill causing the delay to allow more pressing legislation such as tax cuts or budget items to move forward.

“I think you’re going to start to see some of that happen,” Chambers said. “I think if (Cavanaugh) has the physical stamina, she can do it. I don’t think she shoots blanks.”

#us politics#news#nbc news#nebraska#Machaela Cavanaugh#filibuster#trans healthcare ban#trans healthcare#trans rights#transgender#lgbtqia+ rights#lgbtqia+#lgbtqia+ representation#Nebraska Legislature#2023#Brandon Metzler#Abbi Swatsworth#OutNebraska#Kathleen Kauth#hormone therapy#gender reassignment surgery#Ernie Chambers#John Arch

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just wondering but do you have any more lit theory recs? Or texts you think are like, basic readings? I had several literature modules in uni but they were ass and gave us No theorical base for analysis 😭 also it's fine if they are German/in German, I'm sure many of them will have translations into English

most intro books for literary theory are very easy to read as they're usually conceptualized for undergrad students, I think a classic one in english is terry eagleton's intro to literary theory? (I have a different one but i forgot which one i gave to it to a friend lol but in my experience, most are very accessible)

for narratology theories

Aristoteles' poetica if you wan to know how very early narrtology was theorized (a lot of fundamental concepts were conceptualized back then)

Barthes for authorship discourse (or others there's so many but Barthes is a good starting point)

Genette for narrative discourse

and then you have literary theory and criticism, but there is a LOT and not everything might interest you and worth a read, so I'd suggest just skimming some and only reading the ones you're interested in, I enjoy Bakhtin (Carnival, Laughter, dialogism), Kristeva (abjection), semiotics in general (saussure etc.), and post-structuralism is sth I'd also recommend

#metzler verlag der klassiker auf deutsch btw#this list is not complete by any means so I'd def recommend reading one or two good intro books#and using those as a starting point#im way too lazy to read everything so having abook that summarizes everything is always good#ive read all theories years ago but its been so long so i dont remember everything#but its good to know where to looks for what im a big fan of buying good intro books jkfdvmfv#good investment#asks

41 notes

·

View notes

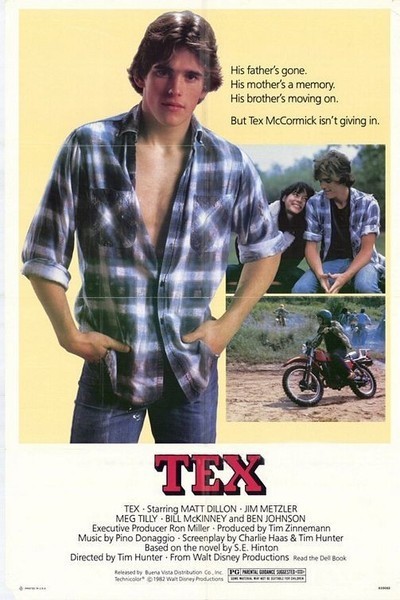

Photo

Shane Metzler

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plughead Rewired: Circuitry Man II (Steven & Robert Lovy, 1994)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketchy redraw of a drawing I made a year or so ago. They're my ocs, Hayden Metzler (who's not awake atm) and Anthony Lamonica who is sort of an insect God destined to eat other Gods that threaten the very fabric of reality.

They're in love <3

The original is under the thing blah blah

#heyden metzler#anthony lamonica#the idea was not to draw this but to draw little cards for stacy and her story so I could explain the plot of that one#which is more of an illustrated dark fairy tale story#this one is just straight up horror#that's still coming probably but also I'm finally learning how to make my digital art look like my trad art#more or less#so that's good#either way#blorbos from my head#original characters#my art

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grace Metzler (American, b. 1989)

We have everything we need, 2022

Oil and acrylic on canvas

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Torma Istvánné vs. Walter Bosse

8 notes

·

View notes

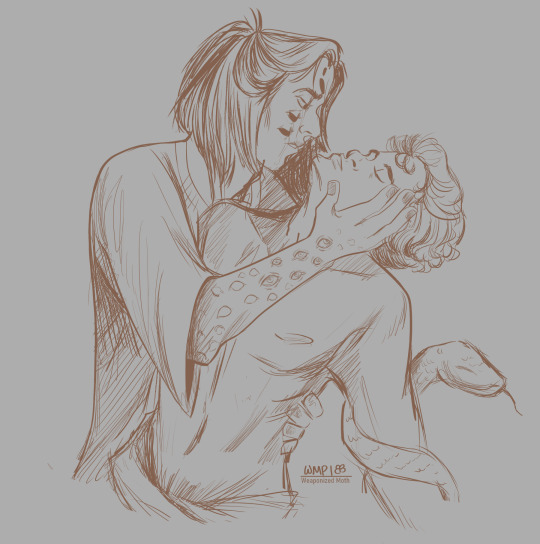

Text

#never forget#unsolved murder#heidi childs#david metzler#close to home#Caldwell fields#blacksburg#virginia tech#virginia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maid (2021)

Eine amerikanische Netflix-Miniserie, die auf Stephanie Lands Roman ,, Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother's Will to Survive" aus dem Jahr 2019 basiert.

Alexs Leben ist nie einfach gewesen, da die Ehe ihrer Eltern von Gewalt geprägt worden ist.

Alexs Mutter gerät nach ihrer Scheidung in eine Lebenskrise. Sie vermacht ihrem eigentümlichen Freund ihr Haus, während sie nun in einem Van am Rande der Stadt lebt und sich nun voll und ganz ihrer Kunst und ihrem Drogenkonsum widmet. Alex Vater lebt mit seiner neuen Familie fernab von seiner ältesten Tochter.

Alex gerät früh in eine Beziehung, die der Ehe ihrer Eltern sehr nahe kommt. Alexs Freund Sean terrorisiert seine Freundin und ihre gemeinsame Tochter Maddy auf täglicher Basis mit seinen spontanen Wutausbrüchen und seinem Alkoholkonsum.

Eines Nachts beschließt sie, ihrem Elend zu entkommen: Sie packt ihre Sachen, nimmt ihre Tochter und verlässt Sean, während er noch schläft.

Was nun beginnt, ist ein ewiges Pendeln zwischen zeitweiligen Unterkünften in Frauenhäusern und bei Freunden, Putzjobs und Seans bösartigen Versuchen, sie und Maddy mithilfe seiner Anwälten zurückzugewinnen.

Das Putzen sichert ihren Lebensunterhalt und ist ein gefundenes Futter für ihren seelischen Zusammenbruch, sei es durch ihre schwierigen Kunden oder die körperliche Belastung.

Ihrer Tochter zuliebe gibt Alex nie auf und macht wieder, egal, wie aussichtslos die Situation scheint, in der sie sich befindet.

(7/10)

#Maid#2021#Netflix#mini series#American drama#Molly Smith Metzler#Stephanie Land#Margaret Qualley#Nick Robinson

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

DISABLED CHILDREN: BIRTH DEFECTS, CAUSALITY AND GUILT

“In his book on intellectual disabilities, Chris Goodey draws illuminating parallels between the medical and psychological description of modern ‘coping strategy’. Parents in the contemporary Western world are informed by the experts (obstetricians, paediatricians and so forth) that their child is disabled. Almost as a reciprocal gesture, those experts expect parents to demonstrate a ritualised hierarchy of reactions (among others initial shock, followed by rejection of the child, leading to acceptance of the diagnosis).

This is termed the ‘coping strategy’, and is comparable to the pre-modern version of such a ‘desanctification ritual’, in which supernatural agents such as devils, witches or fairies were blamed for producing the ‘wrong’ child. So, what caused the ‘wrong’ child according to medieval notions? Medieval thought has commonly used the imagery of the microcosmos, whereby the human body represents on the small scale the ordering and hierarchy of the wider world on the large scale.

William of Conches (c.1090–c.1160) stated in his Sacramentarium that the body from head to foot is likened to all of creation. By analogy, what can go wrong with the macrocosmos, i.e., the corruption of the world through sin, can also go wrong with the microcosmos, i.e., the corruption of the body through illness. Refinements and additions were made throughout the high Middle Ages to this basic notion.

In particular, the entire business of engendering children was focused upon in terms of the analogy of the corporeal and the spiritual. Of fundamental importance was the notion of sin, especially Original Sin. Augustine, writing in the late fourth century, had set the tone: though God had given humans the capability for sexual intercourse, and in essence the act was good, in practice every concrete act of intercourse was evil and therefore every child could literally be said to have been conceived in the sin of its parents.

Such ideas went a long way. By the thirteenth century a bestiary compiler could say that all new-borns, of all species, are ‘dirty’: ‘In fact, all recently born creatures are called “pulli”, because they are born dirty or polluted’, and only the act of baptism both metaphorically and literally cleans the infant. Given the fact that human beings only enter this world by procreation, one may then ask how, in medieval aetiologies, temporal factors and the actual practices of intercourse determined the appearance and character of the child.

In a series of translations of writings known as the Pseudo-Clementines from Greek into Latin as The Recognitions around AD 410 by Rufinus, texts which were very popular in the Middle Ages and survive in numerous manuscripts, a passage states that sexual incontinence is accompanied by demons whose ‘noxious breath’ produces an ‘intemperate and vicious progeny … And therefore parents are responsible for their children’s defects of this sort, because they have not observed the law of intercourse’.

Here, in late Antiquity, we already have the main line of argument that was to be pursued throughout the Middle Ages, which can be summed up as follows: intercourse at the wrong time and in the wrong way will result in the birth of defective children. The Chronicon Salernitanum (chapter 14), written in the tenth century, mentions a woman who conceived by a priest and whose child was born without bones, which demonstrates, sneers the chronicler, that her repentance had not been stiffened with true contrition.

Gratian in the mid twelfth century cites a letter by Boniface suggesting that corrupt sexual unions would produce corrupt children. And in an early fifteenth-century sermon Bernardino of Siena links neglect of filial duty with the punishment of begetting crippled, ugly, foolish and corrupt children. However, a seemingly dissenting theory was proposed on the grounds of logical reasoning by Albertus Magnus, who turned the emergent notion of hereditary traits on its head.

Possibly with a hint of irony Albertus claims that wise fathers beget foolish children, while foolish parents breed wise offspring: ‘wise men mostly produce defective, foolish (fatui) children … because he who is good at study is bad at sex (malus in venero acto)’, since ‘sex is the most foolish act a wise man commits in all his life’, therefore the reverse must be true as well, and ‘simple men’ have wise offspring.

Nevertheless, medieval notions of heredity were far from comparable with the modern Mendelian, never mind genetic, concept of heredity, despite occasional random similarities. Although mid sixteenth century, Ambroise Paré’s work on monsters is still pertinent for discussion of the Middle Ages, since he cites many medieval examples of monstrosities, but also in mindset he is not far from medieval understandings of the monstrous.

In chapter 13 he cites examples of monsters that are created by hereditary diseases, where intellectual disability and epilepsy are mentioned in close conjunction: ‘also if the father and the mother are fools usually the children are scarcely if ever intelligent (similarly epileptics give birth to children who are subject to epilepsy)’.

By way of cultural comparison some evidence from the Islamic world may be useful, such as ideas from early twentieth-century Palestine cited by Dols: ‘Insanity could also be inherited; some people believed that coitus nudus, intercourse in the open, or during menstruation affected the mental state of the child.’

And in the hadith, the pious traditions in Islam, in treatises on Prophetic medicine the aetiology of mental disorder is sometimes mentioned, for instance by Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziya (d. 1350), The Medicine of the Prophet, who says that ‘a man who does not perform ghusl, or major ablutions, before sexual intercourse is responsible if his wife gives birth to a mentally retarded child’.

Most discussions in medieval treatises centre on the method used in intercourse. Any deviation from the one prescribed method (the so-called missionary position) was seen either to avoid the main purpose of the act, namely procreation, or if a child was conceived by any other method then it would ‘suffer deformities because of its parents’ aberrant practices’.

A popular work falsely ascribed in the Middle Ages to Albertus Magnus, De secretum mulierum (On the Secrets of Women), mentions three main reasons why defective children are born: firstly, if the woman did not lie absolutely still but actually moved during intercourse, the male seed ‘might be divided and a defective child conceived’; secondly, the woman should not let her thoughts wander during intercourse, but she should concentrate on what is going on, otherwise if at the critical moment she thought of something else, e.g. some animal like a cow, the child might turn out to resemble one; and thirdly, any non-standard coital position might result in birth defects in those children who were the results of their parents’ experiments in the conjugal bed.

Here we have an example of the immensely influential concept of the maternal imagination. During intercourse and/or pregnancy, the mother can be imprinted by images that she sees, which will affect the shape and nature of the unborn or even unconceived child. This belief can be traced back to at least the Old Testament, where in Genesis 30:25–43 Jacob placed striped branches in front of the sheep of Laban, so that all the offspring of that flock were born with striped fleeces, which Jacob claimed as his own.

The topic is picked up in the early second century in a gynaecological text by Soranus, and again in Augustine’s treatise Against Julian, both of which tell the story of a disfigured Cyprian tyrant who had beautiful works of art placed in the bedroom, so that his wife would look at those during sex rather than him, and thus he would not father a disfigured child.

Similarly, in the aforementioned thirteenth-century bestiary it is said that many people think that pregnant women should not look at ugly beasts such as apes and monkeys, in case they should bring children into the world who resemble these caricatures. For women’s nature is such that they produce offspring according to the image they see or have in mind at the moment of ecstasy as they conceive.

In the Renaissance, such classically-inspired ideas sustained and renewed their popularity; for example, in his astrological treatise Liber de vita of 1489, Marsilio Ficino mentions that ‘people who are making babies often imprint on their faces not only their own actions but even what they are imagining’, thus extending the maternal to a paternal imagination as well. In wealthy Italian households it became important to surround potential parents with desirable images, located strategically so that they could be regarded at key moments.

Leon Battista Alberti repeated this belief in De re aedificatoria (1452) with regard to painted portraits in the bedchamber: ‘Wherever man and wife come together, it is advisable only to hang portraits of men of dignity and handsome appearance; for they say that this may have a great influence on the fertility of the mother and the appearance of future offspring.’ Additionally, astrological explanations were offered.

An example can be found in the twelfth-century text Causae et curae by Hildegard of Bingen: though men know the proper time for agricultural activities yet they beget their own offspring at any time without regard to the proper period in their lives or to the ‘time of the moon’, and defective children are the likely outcome of such heedlessness.

In the more scientific work, as opposed to spurious texts attributed to him, Albertus Magnus (c. 1206–80) argues that deformed births could be a result of particular causes, which would be related to the paternal seed and the maternal reception thereof, while general causes could include the location and the relationship of the stars at the time of conception.

Albertus is not exactly certain which one of these causes is responsible, but he notes that some planetary conjunctions are recognised as particularly malicious, and points out that conception and birth should be avoided at such times. Specific problems might arise with regard to children born under a new moon, as they might be defective in sense and discretion.

Albertus claims to have seen himself the results of astrologically mistimed conceptions on two occasions, where human beings were born with truncated arms and legs who ‘figuram corporis humani non habebit’ (will not have the appearance of a human body).

For a popular expression of similar ideas one can look even farther back, finding them in Old English texts, which seems to indicate the antiquity and the persistence of these notions, whereby the characters and the fates of children are influenced by the position of the moon on the day they are born. We find that the food consumed by the pregnant woman could have an influence on the shape of the child as well, according to the same Anglo Saxon culture which produced such astrological treatises.

In a collection of medical, astrological and magical texts we find the notions that ‘if a woman is four or five months pregnant and she frequently eats nuts or acorns or any fresh fruit then it sometimes happens because of that that the child is stupid’; furthermore, if the expectant mother eats flesh of bull, ram, buck, boar or gander ‘or that of any animal which can beget, then it sometimes happens because of that that the child is humpbacked and deformed [?]’.

It is worth pointing out that all the meat the pregnant woman should avoid consuming is from male animals, and only the male of the species has the capability to beget, as we shall see. Here we also touch on concern with the very modern topic of maternal nutrition.

Soranus, practising medicine under emperors Trajan and Hadrian, had already said in his Gynaecology that pregnant women should be challenged in their desires ‘for harmful things’, by telling them that what is harmful to the stomach is also harmful to the foetus ‘because the fetus obtains food which is neither clean nor suitable, but only such food as a body in bad condition can supply’.

If a parent was particularly blamed for inappropriate behaviour that negatively influenced the development of the baby, it was the mother. A handful of examples from both the very early and very late Middle Ages may illustrate this point.

In the fifth century Nemesius, compiler of an influential tractate on the soul, also looked at child development, and with regard to the causes of unfavourable bodily temperament stated: ‘if the surroundings are dry, bodies become dry, if not all in the same way, and if a mother lives an unhealthy life and is luxurious her children will in consequence be born with a poor bodily temperament and wayward in their impulses.’

…Popularly disseminated notions on improper sexual conduct can also be found in religious literature aimed at what might be termed a mass-market: penitentials, preaching and sermon tracts. Here the argument based on sex and sin is expanded upon, and damaging factors such as pregnancy, lactation or menstruation are considered.

Robert of Flamborough, in the Liber penitentialis (1208–13), warned that children conceived during pregnancy (disregard the biological impossibility for the moment), during menstruation, or before a previous child was weaned, would be lame, leprous, given to seizures, deformed or shortlived. Note that all three inopportune times Robert refers to are times that were believed to be infertile periods, in other words naturally contraceptive periods.

With the absence of modern over-nutrition, in the past (as still in many traditional societies) the lack of nutrition influenced female fertility to the extent that the physical demands of breastfeeding on the body tended to prevent conception during that time. As we know from medieval childcare manuals, breastfeeding would ideally have continued until children were weaned at around two years of age. Conception during these two years was then unlikely.

Many modern hunter-gatherer societies equally do not wean children until two years old, and have lower levels of calorific intake than Western women, so among such peoples births tend to be spaced out at two-year intervals. One could speculate that precisely because of the lack of conception during such times, which medieval people, especially women, may well have been aware of, they were forbidden by moralists, as intercourse then would have been for pleasure only and not for procreative purposes.

In his Sermons, Berthold of Regensburg adds to such lists of physical deformities the dangers of deafness, mean spiritedness and demonic possession, again, potential disability and moral defectiveness in children is ascribed to their conception at forbidden times, to which Berthold adds the six weeks immediately after childbirth (yet another infertile period), and furthermore notes that nobles and burghers are less prone to such sins than the peasantry. In his sermon on matrimony, he writes:

All the children who are conceived at such times you rarely will gaze at with a loving look; for it is either possessed by the devil, leprous, epileptic, humpbacked, blind, crippled, dumb, foolish or has a head like a mallet. … And this happens mainly to peasants and ignorant people. It does not happen to noble people and burghers in towns.

A thirteenth-century French church synod proclaimed that the children conceived from illicit sex would be born humpbacked, crippled, or deformed in some way. From a fourteenth-century manuscript we have the usual prohibition of sexual activity during menstruation, lactation and pregnancy, and the prediction that children born from such unions would be leprous, lunatic or possessed.

And an early fifteenth-century book of homilies, basing its knowledge on St Jerome, provides the full catalogue, stating that ‘children conceived during maternal menstruation would be lepers, maimed, unshapely, witless, crooked, blind, lame, dumb deaf and of many othre mescheues’. Of the three inopportune, even proscribed, times of conception, menstruation was singled out as particularly important to avoid if parents wanted to prevent the conception of impaired children.

Menstruation was regarded as dangerous by scholastic authorities, using arguments in part derived from Aristotle. Aristotle had argued in Generation of Animals, IV, 3–5 that foetal aberrations should be blamed on a divergent movement of the female matter, and an imbalance of female matter with the formative sperm.

While acknowledging that during the medieval period two competing and widely debated models of conception existed – the single-sex and the two-seed theories – it is, for the purposes of discussing medieval notions of birth defects, almost irrelevant to which theory a medieval authority subscribed. Misogyny was ingrained enough to find ample scope in both theoretical models for almost exclusive ‘blame’ on the woman.

Broadly put, according to the single-sex model of natural science, the menses (or menstruum, female seed) accumulates gradually over each cycle as a kind of formless matter. Only the male seed has form itself and is pure maleness. The female simply receives the seed and nurtures it, but does not generate. By extension of this reasoning the female is of necessity defective; an idea that is theologically backed up by Genesis, where Eve’s creation out of Adam’s bent rib made Eve herself deviant from the male norm.

The clearest expression of this kind of argument can be found in Albertus Magnus’ De animalibus, where, moving on from the premise of menses as formless matter, he reiterates the practical advice given by theologians and physicians alike that semen has the best chances of ‘forming’ the menses in the earlier part of the cycle.

If conception takes place during a later stage of the cycle, however, there is a sliding scale of degradation and degeneration: having missed the ideal time for generating male offspring, the next best would be female children, hence only slightly deformed, followed by the severely defective (disabled) progeny, and lastly and worst no offspring at all – the horror vacui of medieval philosophy. It is worth just repeating this descending scale from perfect male, to slightly imperfect female, to certainly imperfect deformity, to nothing.

Such notions are also apparent in medical texts, for instance the Lilium medicinae of Bernard de Gordon, where conception during menstruation is blamed for the birth of an epileptic child: ‘When a person is begotten during the time of menstruation or from unclean seed, or if the parents are epileptic, and if after his birth he falls into epilepsy, such a person does not seem curable.’ Another famous physician and Bernard’s contemporary, John of Gaddesden in his Rosa anglica, states similar things about the aetiology of congenital epilepsy.

The effects of malconception could have a straightforward causal link, a rational explanation even. In discussing the origin of dwarfs, for example, Albertus Magnus describes a nine-year-old girl whom he had seen in Cologne who had not yet reached the height of a one-year-old boy. He followed the argument of Avicenna, which was perfectly scientific by the standards of the day, explaining that the lack of growth was due to the fact that at the moment of conception only a part of the paternal seed had reached the maternal uterus.

During the same century, writing c. 1276, Giles of Rome in his more general discussion of embryology De formatione corporis humani in utero holds a rather neutral opinion, stating blandly that although normally the male seed generates a male foetus from the menstruum, nothing in nature is so stable and fixed that things cannot go wrong sometimes, which is obvious from the fact that occasionally monsters are born with deformed members.

The medieval scientific approach was one that regarded all material creation as inherently imperfect, hence birth defects and congenital disability were not just individual markers on a sliding scale of imperfection, but also natural events to be expected.”

- Irina Metzler, Medicine, Religion and Gender in Medieval Culture

#cw: ableism#medieval#history#irina metzler#pregnancy#medicine religion and gender in medieval culture

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A message from Leah Metzler

#leah metzler#Panic! at the Disco#brendon urie#nicole row#Mike Naran#dan pawlovich#viva las vengeance

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What I’m watching (2023 Edition) || Queer Eye Brasil - 1ª Temporada (2022)

#queer eye#queer eye brasil#watching#watching23#Queer Eye for the Straight Guy#David Collins#David Metzler#Yohan Nicolas#Fred Nicácio#Guto Requena#Rica Benozzati#Luca Scarpelli#netflix

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Plagues & Pleasures On the Salton Sea (2004)

#plagues & pleasures on the Salton Sea#the salton sea#documentary#chris metzler#jeff springer#john waters#sonny bono#talks

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

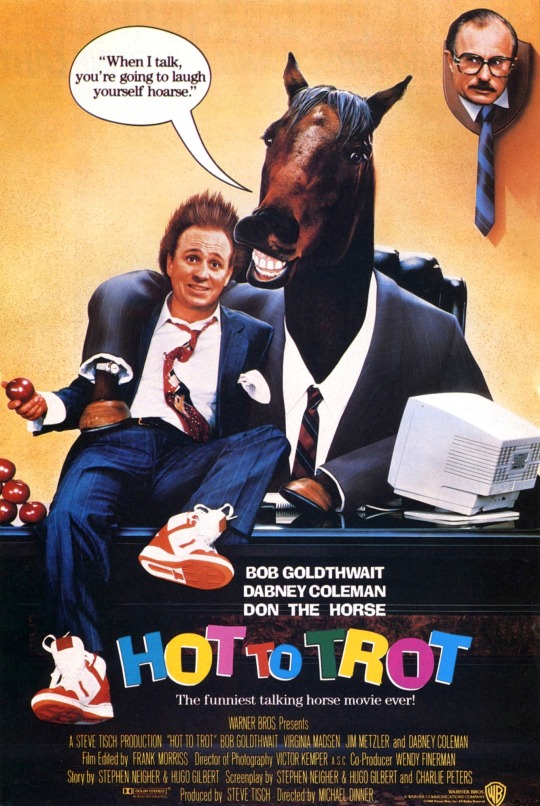

Hot to Trot (1988, Michael Dinner)

1/5/23

#Hot to Trot#Bobcat Goldthwait#Dabney Coleman#John Candy#Virginia Madsen#Cindy Pickett#Jim Metzler#Tim Kazurinsky#Mary Gross#Lonny Price#80s#comedy#horses#talking animals#stock market#yuppies#inheritance#interspecies#jockeys#horse racing#rags to riches#dreadful#unfunny#animal cruelty

3 notes

·

View notes