#musa acuminata

Text

Banana Plant 'Musa Acuminata'

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#musa acuminata cv. Morado#red banana#greenhouse#Shinjuku Gyoen National Park#Tokyo#アカバナナ#新宿御苑大温室#新宿御苑#東京#Voigtlander Macro APO-Lanther 125mm F2.5 SL

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

n312_w1150 by Biodiversity Heritage Library

Via Flickr:

Flore des serres et des jardins de l'Europe A Gand :chez Louis van Houtte, eÌditeur,1845-1880. biodiversitylibrary.org/page/27758983

#Missouri Botanical Garden#Peter H. Raven Library#bhl:page=27758983#dc:identifier=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/27758983#flickr#musa zebrina#Blood banana#Musa acuminata var. zebrina#red banana tree#stripe-leaved banana#botanical illustration#scientific illustration

0 notes

Text

"In response to last year’s record-breaking heat due to El Niño and impacts from climate change, Indigenous Zenù farmers in Colombia are trying to revive the cultivation of traditional climate-resilient seeds and agroecology systems.

One traditional farming system combines farming with fishing: locals fish during the rainy season when water levels are high, and farm during the dry season on the fertile soils left by the receding water.

Locals and ecologists say conflicts over land with surrounding plantation owners, cattle ranchers and mines are also worsening the impacts of the climate crisis.

To protect their land, the Zenù reserve, which is today surrounded by monoculture plantations, was in 2005 declared the first Colombian territory free from GMOs.

...

In the Zenù reserve, issues with the weather, climate or soil are spread by word of mouth between farmers, or on La Positiva 103.0, a community agroecology radio station. And what’s been on every farmer’s mind is last year’s record-breaking heat and droughts. Both of these were charged by the twin impacts of climate change and a newly developing El Niño, a naturally occurring warmer period that last occurred here in 2016, say climate scientists.

Experts from Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies say the impacts of El Niño will be felt in Colombia until April 2024, adding to farmers’ concerns. Other scientists forecast June to August may be even hotter than 2023, and the next five years could be the hottest on record. On Jan. 24, President Gustavo Petro said he will declare wildfires a natural disaster, following an increase in forest fires that scientists attribute to the effects of El Niño.

In the face of these changes, Zenù farmers are trying to revive traditional agricultural practices like ancestral seed conservation and a unique agroecology system.

Pictured: Remberto Gil’s house is surrounded by an agroforestry system where turkeys and other animals graze under fruit trees such as maracuyá (Passiflora edulis), papaya (Carica papaya) and banana (Musa acuminata colla). Medicinal herbs like toronjil (Melissa officinalis) and tres bolas (Leonotis nepetifolia), and bushes like ají (Capsicum baccatum), yam and frijol diablito (beans) are part of the undergrowth. Image by Monica Pelliccia for Mongabay.

“Climate change is scary due to the possibility of food scarcity,” says Rodrigo Hernandez, a local authority with the Santa Isabel community. “Our ancestral seeds offer a solution as more resistant to climate change.”

Based on their experience, farmers say their ancestral seed varieties are more resistant to high temperatures compared to the imported varieties and cultivars they currently use. These ancestral varieties have adapted to the region’s ecosystem and require less water, they tell Mongabay. According to a report by local organization Grupo Semillas and development foundation SWISSAID, indigenous corn varieties like blaquito are more resistant to the heat, cariaco tolerates drought easily, and negrito is very resistant to high temperatures.

The Zenù diet still incorporates the traditional diversity of seeds, plant varieties and animals they consume, though they too are threatened by climate change: from fish recipes made from bocachico (Prochilodus magdalenae), and reptiles like the babilla or spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), to different corn varieties to prepare arepas (cornmeal cakes), liquor, cheeses and soups.

“The most important challenge we have now is to save ancient species and involve new generations in ancestral practice,” says Sonia Rocha Marquez, a professor of social sciences at Sinù University in the city of Montería.

...[Despite] land scarcity, Negrete says communities are developing important projects to protect their traditional food systems. Farmers and seed custodians, like Gil, are working with the Association of Organic Agriculture and Livestock Producers (ASPROAL) and their Communitarian Seed House (Casa Comunitaria de Semillas Criollas y Nativas)...

Pictured: Remberto Gil is a seed guardian and farmer who works at the Communitarian Seed House, where the ASPROL association stores 32 seeds of rare or almost extinct species. Image by Monica Pelliccia for Mongabay.

Located near Gil’s house, the seed bank hosts a rainbow of 12 corn varieties, from glistening black to blue to light pink to purple and even white. There are also jars of seeds for local varieties of beans, eggplants, pumpkins and aromatic herbs, some stored in refrigerators. All are ancient varieties shared between local families.

Outside the seed bank is a terrace where chickens and turkeys graze under an agroforestry system for farmers to emulate: local varieties of passion fruit, papaya and banana trees grow above bushes of ají peppers and beans. Traditional medicinal herbs like toronjil or lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) form part of the undergrowth.

Today, 25 families are involved in sharing, storing and commercializing the seeds of 32 rare or almost-extinct varieties.

“When I was a kid, my father brought me to the farm to participate in recovering the land,” says Nilvadys Arrieta, 56, a farmer member of ASPROAL. “Now, I still act with the same collective thinking that moves what we are doing.”

“Working together helps us to save, share more seeds, and sell at fair price [while] avoiding intermediaries and increasing families’ incomes,” Gil says. “Last year, we sold 8 million seeds to organic restaurants in Bogotà and Medellín.”

So far, the 80% of the farmers families living in the Zenù reserve participate in both the agroecology and seed revival projects, he adds."

-via Mongabay, February 6, 2024

#indigenous#ecology#agroforestry#agriculture#traditional food systems#traditional medicine#sustainable agriculture#zenu#indigenous peoples#farming#colombia#indigenous land#traditional knowledge#seeds#corn#sustainability#botany#plant biology#good news#hope#climate action#climate change#climate resilience#agroecology#food sovereignty

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

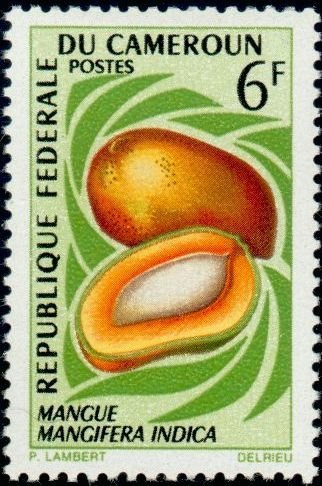

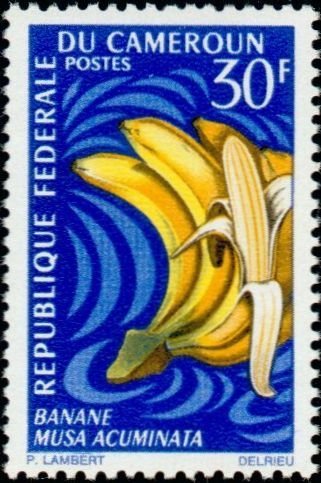

two 1967 Cameroon stamps from a series on fruits

[ID: two postage stamps with illustrations of fruit. the left depicts two mangoes, one of which has been cut in half. the skin of the mangoes is golden, as is the flesh. the pit in the middle is white. this stamp has been labelled "mangue / mangifera indica". the face value of this stamp is 6 Central African CFA franc. the right stamp depicts a bunch of ripe bananas, one of which has been peeled open. this stamp has been labelled "banane / musa acuminata". the face value of this stamp is 30 Central African CFA franc. end ID]

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

Pelipper mail! A... nightmare? No, just a dream?

"What is that... being?" a voice asks. You find you are laying on your side, eyes closed, with the voice from above you.

Another answers: "I really don't know. It's something. It looks alive."

"It looks unwell. It's lost... something. Without knowing what it is, I can't tell what."

You blink open your eyes and see leafy vines, but not yours, spreading over a metal floor. A voice exclaims that you're awake, but from where? You struggle to your feet.

"Hello there!" The voice seems to be speaking to you now, and you slowly realize it is the masses of vines themselves which are producing the words. "What might you be?"

"I am--" you manage, before the other plant-thing interrupts.

"It's sapient! Well, that settles that bet..."

"I... don't know who I am," you say. "My name... I have lost my name, I am only..." You realize something. "I have lost both my names."

"Well, my name is Etlingera Elatior, First Bloom (she/her)," says the cluster of leafy material interspersed with pink flowers. "This here is Heteranthera Limosa, Third Bloom (she/her). We saw what looked like a wormhole, came to investigate, and there you were. We brought you in."

"Unusual to see fellow plant-based lifeforms around," the other says, the blue-flowered one with thinner vines. "First sapient plant I've personally seen besides us affini, certainly."

You try to speak. "I was... somewhere else. I was... someone. A daughter, a teacher, I think. And now I'm not. Without a personal name, or even a species name... I am no one, here. Where is here?"

You look around, but recognize nothing in this metal room except a window to one side -- and through it, the stars? The night sky, moonless, in every direction you look.

"Here," Etlingera says, "assuming you have no connections binding you to whatever place you came from -- if you don't have the means to send yourself back, neither do we, and it sounds like you didn't have a good experience there anyway -- is a new life. With us, should you choose, or as an independent sophont anywhere in the Compact."

"But... my names?"

"Oh, don't worry!" Heteranthera tells you. "We have names aplenty! New names whenever you might want one. I can even give you a name now, if you wish?"

You're not sure what to say to that. You know the names you used to have, the names you can no longer remember, were important to you -- one, especially so. But if they are lost, well, you were planning to gift yourself a third name regardless, even if just as a trial, even if you were terrified the whole way through.

"Let's see, you look like a... Musa Acuminata, Third Floret (she/her), perhaps?"

Etlingera gently slaps Heteranthera with a single vine. "Oh, we mustn't presume like that." Her leaves ruffle in gentle laughter, and when she speaks again it is to you. "But we would be honored if you'd decide to stay with us, now that you've fallen into this universe. It would be a life of great luxury compared to where you came from, I'm certain."

"No need to decide right now," Heteranthera adds. "It will be a week at least before we reach the nearest planet. But we want you to know... losing names is not the end of the world. There are always more, each one personal in a new way for an ever newer you. Perhaps it is better, sometimes, to leave some things behind."

"Because, after all," the pink-flowered Etlingera adds, "a name is a personal thing, for you alone... and people change. If some can't see that, if they tried to hold you by your names as you moved away, then it is worth the pain of seeing them separated from you to know that you are free, now. That you can name yourself anew, and they are left holding only wilting memories of a self you are no longer."

She reaches out with one of her innumerable vines. "Stay, Musa, if we may call you that. Let us be new family to you, in your newest life."

...I didn't like this dream very much. I don't want to lose my names, or my memory. Especially not being taken away from the human world.

I don't know how to feel about the name Musa, though.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

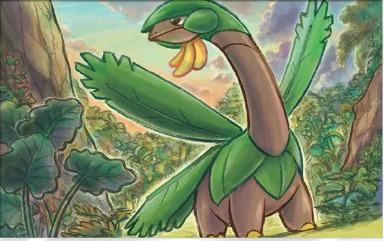

TROPIUS

Tropius is a Grass- and Flying- type Sauropod Pokémon, known for its symbiotic relationship with Musa acuminata, the most commonly known banana plant.

TAXONOMY

Tropius is a sauropod dinosaur of the family brachiosauridae, currently the only known sauropod with a wild population. The smallest known sauropod, it is believed to be the result of island dwarfism. Tropius’ common name comes from “Tropical,” both for its habitat and appearance, and “-saurus,” a term commonly used to refer to large reptiles. Tropius was formerly classified as a Symbiotic Pokémon, but Tropius’ plants are lost and regrown frequently, while a true Symbiotic Pokémon consists of the same individuals throughout entire stages.

DESCRIPTION

Tropius are quadrupedal reptiles with short hind legs, long necks, and no tails. They have rough, brown skin and yellow claws. They are 2 meters long and weigh 100 kg. Tropius cover themselves in soil and grow banana plants directly on their bodies. These plants grow over the Tropius, covering its body with a layer similar to leaf stalks to give Tropius its usual woody appearance. In addition, leaves grow over the Tropius’ head and shoulders. Tropius grow large, sturdy leaves from their back that they can move with specialized muscles to use as wings. These leaves are primarily used for temperature control but are strong enough for the Tropius to fly long distances during migration.

The banana plant’s life cycle remains similar on the Tropius as it would in the ground. The banana plant is composed of many individual stems and propagates over time, with the Tropius discarding older stems to allow new growth. Bananas will sprout near the top of the Tropius’ neck when it is approximately two years of age and every six months thereafter.

Tropius prefer temperatures around 26°C and are extremely sensitive to both heat and cold. Overheated Tropius become agitated and reckless while cold causes them to become slow and lethargic.

HABITAT

Tropius live in tropical jungles, though may occasionally be found outside of that range during warmer months. Tropius do not have set migration paths and instead roam constantly in search of food sources and appropriate weather.

BEHAVIOR

Tropius walk or fly long distances in search of fresh fruit to eat and may stay in an area as long as fruit remains available. Tropius supplement this diet by eating leaves, including excess leaves from their own plant, and small insects, many of which attempt to eat their plant. They seek out areas with comfortable temperatures and spend much of their time resting, letting their plants take in sunlight and adjusting their leaves to help control their temperature. When resting a Tropius will dig a shallow hole to sit in soil.

Tropius are social creatures that will travel in herds when food is abundant but may scatter as food is scarce. Females are more likely to gather than males, and Tropius in herds may groom each other by nibbling excess vegetation and insects from hard to reach places. Tropius are rarely violent and react to most threats by digging their feet into the ground and flapping their leaves hard enough to blow smaller creatures away. They may ‘battle’ each other in this way, doing no permanent harm to the other’s body but potentially damaging their plants.

REPRODUCTION

When a male Tropius’ plant bears fruit, he will actively seek a mate. Males entice females with offers of bananas, showing off the health of their fruit as a sign of their own success and fitness. The couple may mate multiple times, though once the male’s bananas are gone they are unlikely to remain together unless food is abundant nearby. The female will build a nest of leaves over the course of the following week, then lay a clutch of four to ten eggs.

Female Tropius will remain close to their nests for the six weeks it takes for the eggs to hatch, during which time she may be vulnerable. If other Tropius are nearby, they will assist in guarding the nest.

Once the eggs hatch, the mother feeds her young her own bananas for the first few weeks of their life and helps them to cultivate their first seeds. Tropius hatchlings are 0.3 meters long, have no visible plant growth until two months of age and do not grow their leaf ‘wings’ until nine months. Once their wings have grown, they may leave their mother.

Female Tropius with no young will feed and care for other young Tropius or creatures of similar size or coloration. Tropius have been seen ‘adopting’ Patrat, Zigzagoon, immature Pinsir, and human children.

HARVESTING BANANAS

Tropius bananas are particularly sweet and are considered a delicacy. Tropius ranching must be done in large greenhouses to ensure proper temperature control and access to sunlight. These ranches primarily raise female Tropius and keep males only for breeding. In areas with wild Tropius, children are often sent out to politely request bananas. Many trainers supplement their income by harvesting and selling their Tropius’ bananas. Though these bananas have a very short shelf life, the advent of digital item storage has significantly increased the ability for them to be sold all around the world.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi pookie are you still handing out gender? And if yes [takes my hat off like a victorian child begging on the streets] would yew spare one fer me, good sir?

of course darling i can assign you a gender!

your gender is…

Musa acuminata “Red Dacca” or simply just Red Bananas. These bananas grow in and are exported from regions such as East Africa, Asia, South America and the United Arab Emirates. When ripe, raw red bananas have a flesh that is cream to light pink in color. They are also softer and sweeter than the yellow varieties, some with a slight raspberry flavor and others with an earthy one.

enjoy your new gender!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plant of the Day

Monday 18 July 2022

In the Tiltyard at Hampton Court Palace, Surrey, there was an impressive subtropical border. The planting included the tender, upright perennial Musa acuminata 'Zebrina' (stripe-leaved banana). In summer yellow flowers may be produced from purple bracts; these may be followed by small banana fruits.

Jill Raggett

#musa#stripe-leavedbanana#herbaceous#tenderperennial#tender#subtropicalborder#plants#herbaceousperennial#writtledesign#gardens#horticulture#garden#hamptoncourt#surrey#walledgarden

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

idk mate, uhh you want a banana?

[ ? ]

[ WHAT ]

[ ... ]

[ MUSA ACUMINATA ]

[ ? ]

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is a banana?

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry[1][2] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceousflowering plants in the genusMusa.[3] In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguishing them from dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color, and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starch covered with a rind, which may be green, yellow, red, purple, or brown when ripe. The fruits grow upward in clusters near the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible seedless (parthenocarp) bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of most cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana, and Musa × paradisiaca for the hybrid Musa acuminata × M. balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific name for this hybrid, Musa sapientum, is no longer used.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry[1][2] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus Musa.[3] In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguishing them from dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color, and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starch covered with a rind, which may be green, yellow, red, purple, or brown when ripe. The fruits grow upward in clusters near the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible seedless (parthenocarp) bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of most cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana, and Musa × paradisiaca for the hybrid Musa acuminata × M. balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific name for this hybrid, Musa sapientum, is no longer used.

Musa species are native to tropical Indomalaya and Australia, and are likely to have been first domesticated in Papua New Guinea.[4][5] They are grown in 135 countries,[6] primarily for their fruit, and to a lesser extent to make fiber, banana wine, and banana beer, and as ornamental plants. The world's largest producers of bananas in 2017 were India and China, which together accounted for approximately 38% of total production.[7]

Worldwide, there is no sharp distinction between "bananas" and "plantains". Especially in the Americas and Europe, "banana" usually refers to soft, sweet, dessert bananas, particularly those of the Cavendish group, which are the main exports from banana-growing countries. By contrast, Musa cultivars with firmer, starchier fruit are called "plantains". In other regions, such as Southeast Asia, many more kinds of banana are grown and eaten, so the binary distinction is not as useful and is not made in local languages.

The term "banana" is also used as the common name for the plants that produce the fruit.[3] This can extend to other members of the genus Musa, such as the scarlet banana (Musa coccinea), the pink banana (Musa velutina), and the Fe'i bananas. It can also refer to members of the genus Ensete, such as the snow banana (Ensete glaucum) and the economically important false banana (Ensete ventricosum). Both genera are in the banana family, Musaceae.

The banana plant is the largest herbaceous flowering plant.[8] All the above-ground parts of a banana plant grow from a structure usually called a "corm".[9] Plants are normally tall and fairly sturdy with a treelike appearance, but what appears to be a trunk is actually a "false stem" or pseudostem. Bananas grow in a wide variety of soils, as long as the soil is at least 60 centimetres (2.0 ft) deep, has good drainage and is not compacted.[10] Banana plants are among the fastest growing of all plants, with daily surface growth rates recorded of 1.4 square metres (15 sq ft) to 1.6 square metres (17 sq ft).[11][12]

The leaves of banana plants are composed of a stalk (petiole) and a blade (lamina). The base of the petiole widens to form a sheath; the tightly packed sheaths make up the pseudostem, which is all that supports the plant. The edges of the sheath meet when it is first produced, making it tubular. As new growth occurs in the centre of the pseudostem the edges are forced apart.[13] Cultivated banana plants vary in height depending on the variety and growing conditions. Most are around 5 m (16 ft) tall, with a range from 'Dwarf Cavendish' plants at around 3 m (10 ft) to 'Gros Michel' at 7 m (23 ft) or more.[14][15] Leaves are spirally arranged and may grow 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) long and 60 cm (2.0 ft) wide.[1] They are easily torn by the wind, resulting in the familiar frond look.[16] When a banana plant is mature, the corm stops producing new leaves and begins to form a flower spike or inflorescence. A stem develops which grows up inside the pseudostem, carrying the immature inflorescence until eventually it emerges at the top.[17] Each pseudostem normally produces a single inflorescence, also known as the "banana heart". (More are sometimes produced; an exceptional plant in the Philippines produced five.[18]) After fruiting, the pseudostem dies, but offshoots will normally have developed from the base, so that the plant as a whole is perennial. In the plantation system of cultivation, only one of the offshoots will be allowed to develop in order to maintain spacing.[19] The inflorescence contains many bracts (sometimes incorrectly referred to as petals) between rows of flowers. The female flowers (which can develop into fruit) appear in rows further up the stem (closer to the leaves) from the rows of male flowers. The ovary is inferior, meaning that the tiny petals and other flower parts appear at the tip of the ovary.[20]

The banana fruits develop from the banana heart, in a large hanging cluster, made up of tiers (called "hands"), with up to 20 fruit to a tier. The hanging cluster is known as a bunch, comprising 3–20 tiers, or commercially as a "banana stem", and can weigh 30–50 kilograms (66–110 lb). Individual banana fruits (commonly known as a banana or "finger") average 125 grams (4+1⁄2 oz), of which approximately 75% is water and 25% dry matter (nutrient table, lower right).

The fruit has been described as a "leathery berry".[21] There is a protective outer layer (a peel or skin) with numerous long, thin strings (the phloem bundles), which run lengthwise between the skin and the edible inner portion. The inner part of the common yellow dessert variety can be split lengthwise into three sections that correspond to the inner portions of the three carpels by manually deforming the unopened fruit.[22] In cultivated varieties, the seeds are diminished nearly to non-existence; their remnants are tiny black specks in the interior of the fruit.[23]

The end of the fruit opposite the stem contains a small tip distinct in texture, and often darker in color. Often misunderstood to be some type of seed or excretory vein, it is actually just the remnants from whence the banana fruit was a banana flower.[24]

As with all living things on earth, potassium-containing bananas emit radioactivity at low levels occurring naturally from potassium-40 (40K or K-40),[25] which is one of several isotopes of potassium.[26][27] The banana equivalent dose of radiation was developed in 1995 as a simple teaching-tool to educate the public about the natural, small amount of K-40 radiation occurring in every human and in common foods.[28][29]

The K-40 in a banana emits about 15 becquerels or 0.1 microsieverts (units of radioactivity exposure),[30] an amount that does not add to the total body radiation dose when a banana is consumed.[25][29] By comparison, the normal radiation exposure of an average person over one day is 10 microsieverts, a commercial flight across the United States exposes a person to 40 microsieverts, and the total yearly radiation exposure from the K-40 sources in a person's body is about 390 microsieverts.[30][better source needed]

The word "banana" is thought to be of West African origin, possibly from the Wolof word banaana, and passed into English via Spanish or Portuguese.[31]

The genus Musa was created by Carl Linnaeus in 1753.[32] The name may be derived from Antonius Musa, physician to the Emperor Augustus, or Linnaeus may have adapted the Arabic word for banana, mauz.[33] According to Roger Blench, the ultimate origin of musa is in the Trans–New Guinea languages, whence they were borrowed into the Austronesian languages and across Asia, via the Dravidian languages of India, into Arabic as a Wanderwort.[34]

Musa is the type genus in the family Musaceae. The APG III system assigns Musaceae to the order Zingiberales, part of the commelinid clade of the monocotyledonous flowering plants. Some 70 species of Musa were recognized by the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families as of January 2013;[32] several produce edible fruit, while others are cultivated as ornamentals.[35]

The classification of cultivated bananas has long been a problematic issue for taxonomists. Linnaeus originally placed bananas into two species based only on their uses as food: Musa sapientum for dessert bananas and Musa paradisiaca for plantains. More species names were added, but this approach proved to be inadequate for the number of cultivars in the primary center of diversity of the genus, Southeast Asia. Many of these cultivars were given names that were later discovered to be synonyms.[36]

In a series of papers published from 1947 onwards, Ernest Cheesman showed that Linnaeus's Musa sapientum and Musa paradisiaca were cultivars and descendants of two wild seed-producing species, Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana, both first described by Luigi Aloysius Colla.[37] Cheesman recommended the abolition of Linnaeus's species in favor of reclassifying bananas according to three morphologically distinct groups of cultivars – those primarily exhibiting the botanical characteristics of Musa balbisiana, those primarily exhibiting the botanical characteristics of Musa acuminata, and those with characteristics of both.[36] Researchers Norman Simmonds and Ken Shepherd proposed a genome-based nomenclature system in 1955. This system eliminated almost all the difficulties and inconsistencies of the earlier classification of bananas based on assigning scientific names to cultivated varieties. Despite this, the original names are still recognized by some authorities, leading to confusion.[37][38]

The accepted scientific names for most groups of cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata Colla and Musa balbisiana Colla for the ancestral species, and Musa × paradisiaca L. for the hybrid M. acuminata × M. balbisiana.[39]

Synonyms of M. × paradisiaca include

many subspecific and varietal names of M. × paradisiaca, including M. p. subsp. sapientum (L.) Kuntze

Musa × dacca Horan.

Musa × sapidisiaca K.C.Jacob, nom. superfl.

Musa × sapientum L., and many of its varietal names, including M. × sapientum var. paradisiaca (L.) Baker, nom. illeg.

Generally, modern classifications of banana cultivars follow Simmonds and Shepherd's system. Cultivars are placed in groups based on the number of chromosomes they have and which species they are derived from. Thus the Latundan banana is placed in the AAB Group, showing that it is a triploid derived from both M. acuminata (A) and M. balbisiana (B). For a list of the cultivars classified under this system, see "List of banana cultivars".

In 2012, a team of scientists announced they had achieved a draft sequence of the genome of Musa acuminata.[40]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oct. 17, 2022

Sign up for Science Times Get stories that capture the wonders of nature, the cosmos and the human body.

Bananas, it turns out, are not what we thought they were.

Sure, most, when ripe, are yellow and sweet and delicious slathered in peanut butter. But a global survey reveals many more appealing counterparts than the generic banana found in American supermarkets, with edible varieties that can be red or blue, squat or bulbous, seeded or seedless.

And the banana family tree as a whole is even more diverse, and mysterious, than previously thought, according to a study published earlier this month in the journal Frontiers in Plant Science.

“The diversity of bananas is not as well described, as well documented, as we thought,” said Julie Sardos, a botanist at the Bioversity International research group, and an author of the study. “It was really overlooked by past researchers.”

She and her colleagues analyzed genetic material from hundreds of different bananas and found that there were at least three wild banana ancestors not yet discovered by botanists. Like the revelation of a long-lost relative, knowing that these missing wild ancestors are out there could change the way we see bananas and provide potential ways to strengthen the crops against disease.

Wild bananas, or Musa acuminata, have flesh packed with seeds that render the fruit almost inedible. Scientists think bananas were domesticated more than 7,000 years ago on the island of New Guinea. Humans on the island at the time bred the plants to produce fruit without being fertilized and to be seedless. They were able to develop pretty tasty bananas without formal knowledge of the principles of inheritance and evolution.

As trading routes and linguistic connections spread, so did the new banana. It picked up genetic complexity as farmers crossbred it with other wild banana species in regions that became Indonesia, Malaysia and India.

Today, it is possible to use genetic markers to trace these bananas back to their ancestors by simulating breeding patterns in a computer program. This procedure can reveal what kind of trading routes and agricultural practices were established in different communities. And, Dr. Sardos said, “Understanding how banana fruits full of big hard seeds transformed into seedless fleshy edible fruits is an exciting mystery to investigate.”

But when Dr. Sardos and her colleagues ran this analysis on a collection of domesticated bananas, they found that there were three ancestors that they couldn’t account for. One seemed to have a strong genetic imprint on bananas in Southeast Asia. Another was localized around the island of Borneo. The third seemed to be from New Guinea. But, other than leaving their genetic mark in certain geographic clusters of domesticated banana plants, these wild ancestors remained completely mysterious to the scientists.

“Their data is suggesting that there was some domestication in parts of the South Pacific which had not previously been considered,” said James Leebens-Mack, a plant biologist at the University of Georgia who was not involved in the new study. “That’s really cool.”

The discovery of these mystery ancestors is also practical. Seedless, automatically fruit-bearing bananas are sterile, which makes the modern breeding of different bananas incredibly complex, according to Dr. Sardos. “You have to go back to wild bananas,” she said, and figure out how to make fertile plants similar to the edible bananas. Then, you have to breed those plants with others to create a new, edible, sterile banana.

The difficulty of breeding new bananas has led most plantations around the world, primarily in Africa and Central America, to only grow one type: the Cavendish, which is the most widely consumed variety in the world. That’s risky, though, because the low genetic diversity of banana crops makes them susceptible to disease outbreaks.

“You hear it all the time,” Dr. Leebens-Mack said. “At some point, there’s going to be a banana famine, a disease run rampant among plantations.”

Breeders will need to go back to wild bananas to diversify banana genetics and make crops more resilient. They can look at different wild traits and decide which ones may be best for preventing disease, fungal outbreaks or even adaptation to climate extremes. “Maybe the solution is we don’t just stick with our typical banana, we take advantage of these other cultivated lines,” said Pamela Soltis, a botanist at the Florida Museum of Natural History who was not involved in the study.

To do this, though, the banana family tree must be clearer. Dr. Sardos hopes that the discovery of mysterious banana ancestors might spur scientists to do more digging into the crop’s genetic history.

“What we expect, even if it’s not really precise, is to add some weight to the plea for more expeditions for the collection of bananas,” she said.

Mathieu Rouard, another author of the study and a colleague of Dr. Sardos’s at Bioversity International who has been studying bananas for nearly 20 years, added, “My friends and family, they are always amazed I’m still working on bananas. But there are still lots of things to discover, even after all this time.”

The great banana search is on.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are the top widely used fruit's Scientific names :

Apple - Malus domestica

Apricot - Prunus armeniaca

Avocado - Persea americana

Banana - Musa acuminata

Blackberry - Rubus fruticosus

Blueberry - Vaccinium corymbosum

Breadfruit - Artocarpus altilis

Cantaloupe - Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis

Cherry - Prunus avium

Coconut - Cocos nucifera

Cranberry - Vaccinium macrocarpon

Custard Apple - Annona squamosa

Durian - Durio zibethinus

Dragon Fruit - Hylocereus undatus

Fig - Ficus carica

Gooseberry - Ribes uva-crispa

Grapes - Vitis vinifera

Grapefruit - Citrus paradisi

Guava - Psidium guajava

Honeydew - Cucumis melo

Jackfruit - Artocarpus heterophyllus

Jujube - Ziziphus jujuba

Kiwi - Actinidia deliciosa

Lemon - Citrus limon

Lime - Citrus aurantiifolia

Loquat - Eriobotrya japonica

Lychee - Litchi chinensis

Mango - Mangifera indica

Mangosteen - Garcinia mangostana

Mulberry - Morus alba

Nectarine - Prunus persica var. nucipersica

Olive - Olea europaea

Orange - Citrus sinensis

Papaya - Carica papaya

Passion Fruit - Passiflora edulis

Peach - Prunus persica

Pear - Pyrus communis

Persimmon - Diospyros kaki

Pineapple - Ananas comosus

Plum - Prunus domestica

Pomegranate - Punica granatum

Quince - Cydonia oblonga

Rambutan - Nephelium lappaceum

Raspberry - Rubus idaeus

Sapodilla - Manilkara zapota

Starfruit - Averrhoa carambola

Strawberry - Fragaria × ananassa

Tamarind - Tamarindus indica

Tangerine - Citrus reticulata

Watermelon - Citrullus lanatus

0 notes

Text

IJMS, Vol. 25, Pages 3420: MaSMG7-Mediated Degradation of MaERF12 Facilitates Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense Tropical Race 4 Infection in Musa acuminata

Modern plant breeding relies heavily on the deployment of susceptibility and resistance genes to defend crops against diseases. The expression of these genes is usually regulated by transcription factors including members of the AP2/ERF family. While these factors are a vital component of the plant immune response, little is known of their specific roles in defense against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 (Foc TR4) in banana plants. In this study, we discovered that MaERF12, a pathogen-induced ERF in bananas, acts as a resistance gene against Foc TR4. The yeast two-hybrid assays and protein-protein docking analyses verified the interaction between this gene and MaSMG7, which plays a role in nonsense-mediated #RNA decay. The transient expression of MaERF12 in Nicotiana benthamiana was found to induce strong cell death, which could be inhibited by MaSMG7 during co-expression. Furthermore, the immunoblot analyses have revealed the potential degradation of MaERF12 by MaSMG7 through the 26S proteasome pathway. These findings demonstrate that MaSMG7 acts as a susceptibility factor and interferes with MaERF12 to facilitate Foc TR4 infection in banana plants. Our study provides novel insights into the biological functions of the MaERF12 as a resistance gene and MaSMG7 as a susceptibility gene in banana plants. Furthermore, the first discovery of interactions between MaERF12 and MaSMG7 could facilitate future research on disease resistance or susceptibility genes for the genetic improvement of bananas. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/6/3420?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Streetart – Fabio Petani @ Lodz, Poland

Fabio Petani @ Lodz, Poland Fabio Petani @ Lodz, Poland Fabio Petani @ Lodz, Poland Title: NITRIC ACID & MUSA ACUMINATA COLLA Location: Lodz, Poland …Streetart – Fabio Petani @ Lodz, Poland

View On WordPress

0 notes