#nuclear icebreaker

Photo

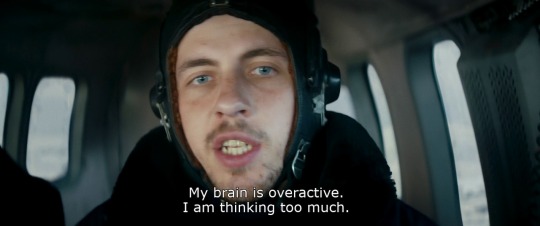

Ледокол [The Icebreaker] (Nikolay Khomeriki - 2016)

#Ледокол#The Icebreaker#Nikolay Khomeriki#disaster film#Sergei Puskepalis#Pyotr Fyodorov#Aleksandr Pal#Antarctica#Alexey Barabash#Vitaliy Khaev#Olga Smirnova#comedy film#History of the Soviet Union#Anna Mikhalkova#Mikhail Somov#Aleksandr Yatsenko#Dmitriy Podnozov#sailors#Murmansk#nuclear icebreaker#Saint Petersburg#Sevastopol#Russians#Terrore tra i ghiacci#Soviet era#Antarctic waters#mutiny#The diamond arm#Mikhail Gromov#USSR

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cover of the day; Day 1: Envelope from a Soviet nuclear ice-breaker

I guess I'll start posting an interesting cover every day, I have a lot of covers so I hope this'll continue for as long as possible.

Oh yeah, if you want to see more covers, here's my website:

---

This cover was sent from the Nuclear Icebreaker "Arktika" to St. Petersburg in 1992 (It arrived to St. Petersburg on christmas day!), by a sailor who worked for the Murmansk Shipping company; whose ID number was SK-5/31.

Also the stationery used to mail this was issued in the USSR but it was used in the Russian Federation

This is my favorite cover in my collection because it came from one of the largest nuclear icebreakers at the time and because of all the handstamps, so I guess I started this cover of the day thing with a bang!

And if you're wondering what's a cover; a cover is an envelope/postcard/aerogramm/etc. complete with stamps and postmarks.

#philately#covers#soviet union#nuclear icebreaker#cover of the day#soviet philately#postal stationary#oh lord look at all those handstamps!#christmas I guess?

0 notes

Text

NUCLEAR ICEBREAKERS?????????!!!!!!!!!!!

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#icebreaker#ships#maritime shit#nuclear power#what sorcery is this#icebreakers

0 notes

Text

#russia#north#murmansk#winter#мурманск#polar circle#polar night#кольский полуостров#moonlight#snow#россия#neonvibes#magic#nuclear#icebreaker#Lenin#атомный ледокол Ленин#polar clouds#magic sky#Кольский залив#train station

0 notes

Text

Protip: if you have a lot of medical implants and you work in a technical field, keep a copy of your x-rays on your phone. Turns out that “hey want to see my fucked-up x-rays” is a pretty great icebreaker when your coworkers are the sort of nerds who will start trying to eyeball the thread pitch of the hardware in your spine. “Are those quarter-inch rods?” Actually I think they’re three-eighths.

There’s something so charming about the glee of a nuclear physicist seeing some new, fucked up use case for titanium. Their eyes just light up. Ask me about airport metal detectors next.

638 notes

·

View notes

Text

Icebreaker ship dogs

Oven - Nuclear powered icebreaker Argo - Arctic expedition sled dog.

Rera - Drift icebreaker Garinko - Dock-worker and companion dog of a Garinko crew member.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uranium in English

1.

A nuclear death shares

its colors with the parrotfish---

chainslick, moccasin,

icebreaker, gigawatt.

The Alabama Shot

stocks "My First Rifles,"

guns in a variety of colors,

pink for girls to shoot squirrels.

I'm arranging information

available to anyone.

2.

I teach my class

the problem/solution structure.

Many logical questions are asked,

several logical solutions proposed.

What about the squirrels?

I ask my students.

Whole neighborhoods

annihilated in Hiroshima,

classrooms like cartoon

shadows in Nagasaki.

We agree one violence

is greater than the others,

but a string of tiny violences

makes the largest possible.

3.

A boy with a Crickett rifle

kills his sister in Kentucky.

No teacher can show him

how to live with it,

no diagram of the body,

no pull-down map

can illustrate the wound

spread across his days.

Not Latin odes, not physics---

his parents can't teach him,

nor the man who sold

his father this miniature

with the knowledge

he'd outgrow it

like a pair of shoes.

4.

In 1789, uranium is found

asleep aside anonymous metals.

The bullet, one could say,

was always inside of us,

the club a casual

extension of our arms.

And if all of our limitations

are armed, what's left

to keep a citizen clean,

what glove can fit

one knuckle's trigger?

5.

And don't imagine

it gets easier hearing about it,

I tell my students, or do I,

when they mention

another errant shooting,

nuclear test. And I worry

for the seasons which cannot

worry for each other,

summer like a fog that won't

dissolve, the end of snow.

Too late to worry, says Jorie---

I do not tell them this.

Instead, I ask, what color

is a disagreement between

friends, between nations---

what does being right look like?

And the shame is that the parrotfish

cannot be remade from scratch,

while the delicate,

collectible uranium glass

will glow into infinity,

a Vaseline sheen.

Maya C. Popa, American Faith (Sarabande Books, 2019)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

[sees a distant shot of the bow of a ship in an aesthetic ocean photograph] WAIT A FUCKING SECOND THAT'S MY GOOD FRIEND THE NUCLEAR ICEBREAKER Ямал

#i mean#it's a very recognizable ship#there are not many of them with big shark mouths#still very funny to scroll past some photography on my dashboard and 'wait. i know that ship. i know that ship by sight.'#'i know so much about that ship. i know details about its fucking propulsion system'#I am bizarrely familiar with the Arktika-class icebreakers. don't worry about why this is the case. it's a long and uninteresting story

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bad Movie Line Prompts

• "I'll make more noise than two skeletons making love in a tin coffin."

• "The only difference between a hero and a villain is the amount of compensation they take for their services. At our pay scale, I'd say we're closer to heroes."

• "You look like you got both eyes coming out of the same hole!"

• "It's like a chainsaw set on frappe."

• "It stops felons, judges the crime, and executes sentence. Justice served C.O.D."

• "We scientists are like degreed science-fiction writers. We're all prognosticators of the future."

• "We're not knocking over tin cans here, this is reality."

• "They were all huddled together, but you know I could tell they had just enough piss and vinegar left in them, that, uh, give them an inch, they'd scream for miles."

• "I'm dying my friend. There is no better. No more birthdays."

• "The bombs that they were building. I saw them. They were as big as hogs dicks on Sunday."

• "If ya feel a wet snout in yer face, whatever you do, don't move. And don't kiss it back, 'cause it ain't me."

• "Do you know a nuclear trigger from a Bulgarian dildo?"

• "The last time we did business, you got my cash and I got your business."

• "I thought you lived by the law of the fist too but you're just a damn cherry!"

Movies: R.O.T.O.R. (1987), Icebreaker (2000), Firehead (1991), Grizzly (1976), Honor and Glory (1992)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks to global warming, there is less ice at the top of the world. And less ice, paradoxically, means a surge in demand for icebreakers, the specialty ships that are seen as the must-have currency to be a player in a melting world.

It’s that time again, when the very real warming in the Arctic—four times greater than the rest of the world—is exceeded only by superheated predictions of a coming great-power clash in the High North. Russia’s been rattling Arctic sabers for years and is now being joined by China. There are renewed worries about a resource scramble, new shipping lanes where ice floes used to be, greater military competition, and as always, the icebreaker gap that periodically frazzles U.S. policymakers.

Russia has scores of icebreakers, specially designed ships that crush ice with their hulls or shear through it to clear lanes of open water, including numerous nuclear-powered ones and one (soon two) armed with deck guns. China has four, as well as a super-advanced one on the way. The United States has just one heavy icebreaker—the half-century-old Polar Star, which is out of its annual dry dock after its Antarctic run—and one medium icebreaker, which is out of action for now after catching fire last month. This summer, there are no U.S. missions in the Arctic; China has three.

The United States and a pair of Arctic NATO allies, Canada and Finland, have announced an ambitious plan to team up and build scores of icebreakers. U.S. officials have touted the so-called ICE Pact, announced on the sidelines of July’s NATO summit, as a mix of friendshoring and industrial policy, leavened with a dose of great-power competition fought with rivets and ratchets, not rockets.

But the looming competition in the Arctic is not like that facing the United States in other oceans or battlefields. The United States has immense strategic interests and challenges in the warmer waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the rest. If the still-chilly waters of the High North get short shrift in Washington, it’s because whatever may come to pass there takes a back seat to things that are happening in the wider world. The U.S. Defense Department’s new Arctic Strategy essentially boils down to a watch-and-monitor approach to an arena that for two decades has been the perennial next great-power flash point.

“Why do we have trouble seeing ourselves as an Arctic nation in anything like the same way as Russia does? One of the reasons is that Russia gets a significant and growing share of its GDP from the Arctic; we do not,” said Rebecca Pincus, director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center.

“The United States is clearly focused on the Indo-Pacific and Europe, so the Arctic is not top of mind—so why the obsession with icebreakers?” said Pincus, who previously worked on Arctic issues at the Pentagon.

The short answer is that all the Arctic nations—there are eight, and seven of them are in NATO—have the icebreakers they need, except for the United States. The long answer is that there seems to be a looming great-power competition up north, and the only way to play is to have the chips, or ships. But the even longer answer is that there is only one gambler at the table—Russia—and it has a very definite tell that can be exploited.

If the competition in the Arctic boils down to another front in the rivalry with Russia (and China is at best a self-proclaimed “near-Arctic state,” despite its frequent polar forays), then the fight should be in Russian shipyards and vulnerable Arctic facilities, not in American ones. The better strategy to combat Russia in the Arctic, Pincus suggested, happens to be the one that the United States and Europe are already employing: making it harder for Moscow to profitably ply the icy waters, not just easier for Washington to do so.

More icebreakers for the United States would not be a bad thing. For years, the United States Coast Guard has said that it requires a minimum of six icebreakers to adequately handle multiple missions a year to both poles, and only a generous accounting of ships on hand can tally even one-third of that minimum; now the service wants eight or nine.

Icebreakers are used up north to support several research missions every summer, as well as for practicing oil-spill response and environmental monitoring. On the far side of the world, the United States has to break in once a year to resupply its Antarctic research station at McMurdo, for which really heavy icebreakers are needed.

The problem is that, while the United States can build some very complex ships such as nuclear aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines, it cannot quite manage to build icebreakers despite years of trying. The Polar Star was built in the 1970s; the Healy, the U.S. medium icebreaker, was built in the 1990s. Since then it’s been dry ice.

In that sense, the new Icebreaker Collaboration Effort, or ICE Pact, makes some sense. Finland and Canada are best in class at building that very particular kind of ship; Finland alone has built more than half of all the icebreakers afloat. For a country like the United States that is now hoping that its much-delayed Polar Security Cutter, the new generation of icebreakers, will arrive only about five years late and over budget, getting some professional help is smart.

“Icebreakers have been a key Finnish know-how for a long time. Now that we are part of NATO, this is one thing that Finland can provide—we are tops in the world in designing and building icebreakers,” said Mika Hovilainen, the CEO of Aker Arctic, the world’s leading designer of icebreakers.

What’s not clear about the ICE Pact, though, is what it will actually deliver or how it will work; the outlines of the collaboration pact as announced so far do not tackle the fundamental challenges that have bedeviled decades of U.S. efforts to build the kind of ship that China turns out inside of two years.

Foreign shipyards, for starters, are off-limits for U.S. Coast Guard and naval vessels, yet they are the ones with the specialized workforces. U.S. shipyards, bereft of investment, workers, work orders, and even dry docks, have enough trouble even building the congressionally mandated number of nuclear submarines, let alone a new class of vessel. Misguided adventures, such as choosing an unproven German design for the new polar cutter rather than a tested blueprint, only add to the woes.

The ICE Pact, Pincus said, is a little bit like AUKUS, the three-way deal among Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom to bring nuclear submarine technology down under. “Except this time, we’re the Australians,” she said of the United States. “What price are we going to have to pay for their expertise?”

Why does the country that invented the nuclear aircraft carrier find it so difficult to build a ship that can drive straight into a six-foot chunk of ice and keep going? It turns out that icebreakers, like nuclear carriers and subs, are very complicated to design and build, and practice does indeed make perfect. Icebreakers need not only specially strengthened hulls, with different attributes depending on whether they will crush the ice or shear it, but also massive engines and absolute all-weather systems.

Aker Arctic, for instance, spent a decade working on hull-strength analysis to figure out just where an icebreaker needs to be strong and where designers can save steel. That matters enormously when building a ship that is explicitly designed to steer straight for what everything else afloat avoids.

“We are gaining that kind of experience with icebreakers, because we design icebreakers all the time,” Hovilainen said. “We have a lot of standard solutions, we know what works, and we can apply that to new projects. If you have to reinvent the wheel in all areas of the ship, it is going to be super complex.”

Perhaps the new ICE Pact will indeed deliver a collaborative arrangement that helps build the estimated 70 to 90 icebreakers that U.S. officials say Western allies need in the years ahead. But the point about the looming Arctic challenge isn’t to build more Western icebreakers—which mostly carry scientists and science projects—but to make sure that the main Arctic rival of the United States and its NATO allies can’t really take advantage of any ice that it breaks. The United States aspires to be an Arctic nation, or at least Alaska lawmakers do; Russia genuinely is. And that presents not so much a threat as an opportunity.

In 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin updated his already ambitious plans for the Russian Arctic by 2035. He added some new hits such as “protecting sovereignty and territorial integrity,” but he kept the old favorites, including the two most important: tapping Arctic resources to drive Russian economic growth and turning the northern coast of Siberia into a shipping lane worthy of the name.

The Russian Arctic does have mind-boggling amounts of oil and natural gas. (The U.S. and Canadian Arctic has lots, too, but it’s easier and cheaper to frack in North Dakota than to drill in the Chukchi Sea.) Tapping those oil and gas reserves is challenging enough, but Russia has been able to do it, to an extent, despite a decade of Western sanctions that have handicapped some of its frontier energy projects. The tricky part is to move that gas from the frozen north to thirsty markets in Asia: Arctic ice may be melting, but that doesn’t mean those are warm-water ports or easy to navigate.

Especially after the onset of the war in Ukraine, which largely foreclosed European energy export markets to Russia, Arctic energy and its shipping routes to the east have become a key strategic priority for Putin. The Yamal Peninsula in northwest Siberia is the epicenter of Russia’s newfound trade in liquefied natural gas, or LNG; since piping it to Europe is no longer an option, and China is proving a hard bargainer on piped gas headed east, freezing it and shipping it out is the future for Russian energy.

For Putin, the so-called Northern Sea Route (NSR)—the would-be shipping lane across the top of Russia—is the embodiment of his end-run around Europe and toward a full embrace with China. Moscow has visions of the route becoming a genuine global sea lane to rival such routes as the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal, no matter the fact that container ships cannot and will not save a few days’ journey by venturing into shallow, ice-filled, foggy waters that Russia calls its own and taxes as such. In 2023, the NSR had its best year yet, shipping a whopping 36 million metric tons. The Suez Canal, when not disrupted by Houthis, transits that much cargo in a week.

There is one vulnerability, though. About half the traffic on the NSR is LNG exports. Shipping gas through ice floes requires icebreaking LNG tankers. Those were previously being built for Russia in South Korea, but the Ukraine war put paid to that, with Seoul canceling the pending delivery of new ice-class tankers. (Western dry docks are still servicing the existing fleet, though.) Russia is trying to build some of its own, and probably can, but it may struggle to master some of the advanced cargo containment technology that was a Western monopoly, Hovilainen said.

That is part of an evolving Western strategy to strike at the Russian weakness in the Arctic. Just after the invasion of Ukraine, Western sanctions poleaxed the big LNG liquefaction facility in the Yamal Peninsula, which was reliant on Western technology. Novatek, the private Russian company plowing ahead, now hopes to jury-rig a solution to get its gas super-chilled and super-moving by 2026, but it is employing unproven workarounds. The facility upped production and even started exports this summer but is still running below capacity.

The West has found other chinks in the armor. This summer, the European Union, in its 14th sanctions package on Russia, specifically targeted Russian transshipment of LNG in European ports—Moscow would use precious ice tankers to ship gas south, then move the gas to a regular tanker for export overseas. With that trade foreclosed, Russia’s hard-worked LNG tanker fleet will have to make the full run from Siberia to the final destination and back again, essentially cutting its energy-export capacity.

Or take the latest Western step to hit Russia. In late August, the United States went after Russia’s LNG shadow fleet with new sanctions. The latest sanctions not only intensify the pressure on Russian gas production and liquefaction in the Arctic, but they also take aim at the fleet of specialized tankers that Moscow needs to build up in order to get its product to its last remaining big market. The goal, the U.S. State Department said, is to “further disrupt” both production and export of Arctic LNG, especially relevant now that the big plant in Yamal is up and running again.

If there is a great-power competition in the Arctic, it is only existential for one of the players. And the recipe for success is not building more icebreakers, welcome as they may be, but making sure that those in Russian hands are opening leads to nowhere.

“We are pressuring Russia with economic tools in the Arctic, which is a cost-effective means of pursuing our goals. Russia’s icebreaker fleet is all about energy exports to Asia,” Pincus said. “That’s why the sanctions are smart. If we can sustain them, and the Russian Arctic oil and gas reserves and facilities become stranded assets, then what is the Arctic to Russia? That could end up starving the NSR.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

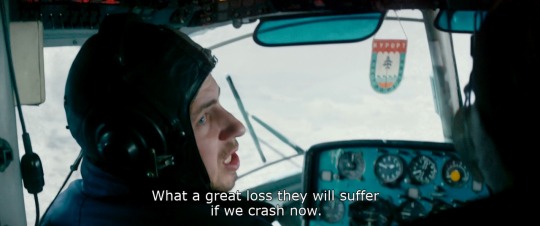

Ледокол [The Icebreaker] (Nikolay Khomeriki - 2016)

#Ледокол#The Icebreaker#Nikolay Khomeriki#disaster film#Sergei Puskepalis#Pyotr Fyodorov#Aleksandr Pal#Antarctica#Alexey Barabash#Vitaliy Khaev#Olga Smirnova#joking#History of the Soviet Union#Anna Mikhalkova#Mikhail Somov#Aleksandr Yatsenko#Dmitriy Podnozov#sailors#Murmansk#nuclear icebreaker#Saint Petersburg#Sevastopol#Russia#Terrore tra i ghiacci#Soviet era#Antarctic waters#mutiny#Mikhail Gromov#leadership#USSR

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Yamal" is a Soviet and Russian nuclear icebreaker of Project 10520 "Arktika". Laid down on October 31, 1986, launched on October 4, 1989.

#cebreaker #Icebreaker Yamal #North Pole #Ocean #Northern Sea Route #Russian Icebreaker Fleet #Arctic

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are you still doing weird physics questions? During a conversation about alternative fuel for paddle steamers, one suggestion was nuclear power. I know there are nuclear-powered subs, so I guess it's not a completely stupid idea. Apparently you can use radioactive ore to heat the water to produce the steam, so basically: is it viable to put a lead-shielded boiler on an old-fashioned wooden-hulled paddle steamer bouyancy- and weight distribution-wise, and if not, what would happen? Thanks.

hmm. thanks anon that's a fun question. many years ago I made a similar investigation about a nuclear powered airship (something the Soviets once thought about), and in the course of that post, I found that the best existing small nuclear fission reactors for space travel generate around 100kW of power and mass in around 500kg, but that might only be on paper performance. that research seems to have been superseded by something called kilopower which generates 1-10kW of electricity from around 40kW of heat, and masses 1500kg. the latter is intended for use on crewed space missions, so it's probably decently shielded.

it's apparently thought possible that a multi megawatt space reactor is possible, massing tens of tonnes. that's on paper though, and it doesn't seem to have been built.

how does that compare to the demands of a steamship? according to this page, a big fuckoff passenger liner from the tail end of the steam era is driven by a few thousand horsepower. by contrast, the first steamship only needed 19 horsepower. this gradually increased to the hundreds of kW as steamships started to regularly cross the Atlantic.

10kW is about 13hp, so the larger end of those tiny space reactors could theoretically power a ship, though it would be a bit weak. as far as mass, I'm not sure how to look up the mass of a steamship power plant very easily, but the Great Western as a whole displaced around 2000 tonnes, so it doesn't sound like the extra mass would be a huge issue.

what about the actual nuclear reactors used on ships, which is termed nuclear marine propulsion? these ships actually do use steam; this is the principle of operation:

Most naval nuclear reactors are of the pressurized water type, with the exception of a few attempts at using liquid sodium-cooled reactors. A primary water circuit transfers heat generated from nuclear fission in the fuel to a steam generator; this water is kept under pressure so it does not boil. This circuit operates at a temperature of around 250 to 300 °C (482 to 572 °F). Any radioactive contamination in the primary water is confined. Water is circulated by pumps; at lower power levels, reactors designed for submarines may rely on natural circulation of the water to reduce noise generated by the pumps.

The hot water from the reactor heats a separate water circuit in the steam generator. That water is converted to steam and passes through steam driers on its way to the steam turbine. Spent steam at low pressure runs through a condenser cooled by seawater and returns to liquid form. The water is pumped back to the steam generator and continues the cycle. Any water lost in the process can be made up by desalinated sea water added to the steam generator feed water.

but these ships not wooden paddle steamers so let's keep investigating.

WP's article tells me

a typical marine propulsion reactor produces no more than a few hundred megawatts.

so the ceiling is clearly way higher than the space reactors! the mass of one of these marine nuclear reactors is not listed in that article. however, the icebreaker Lenin, the first nuclear powered surface ship, displaced 16000 tonnes, or about eight Great Westerns, so that's a bit more overhead for heavy nuclear machinery. the first nuclear submarine, the USS Nautilus, displaced more like 3000 tonnes. still more than the Great Western, but most of that is probably structural mass rather than the nuclear reactor right?

tradeoff wise, I would expect a nuclear reactor to mass more than a coal or diesel engine thanks to all the shielding, but you wouldn't have to carry fuel with you. the Otto Hahn which displaced 17,000 tonnes empty, was apparently able to replace a nuclear reactor with a diesel engine room, and while I don't know how complicated an operation that was, it doesn't sound like they're too enormously different in size or mass.

ok, so, structurally, can a wooden ship handle that? I don't know a lot about shipbuilding but I have watched a bunch of videos on the channel "Casual Navigation", and that's almost the same thing right? the distribution of mass and displaced water on a ship all interacts in a way that's pretty complicated - look into the metacentre to get a glimpse - and I imagine if the ship design had to include a huge heavy powerplant that's considerably denser than the rest of the ship, that's going to impose some funky constraints. and of course wood is also much less strong than steel, which is one reason why wooden ships aren't built on the same sort of scale without internal metal reinforcement. so supporting that reactor will probably take a bunch of metal? but I'm afraid I don't know enough about building ships to get further than those vague statements!

lengthways, a ship can be 'trimmed' much like an aeroplane by distributing the cargo towards the front or the back. if the structural wood is much lighter than the nuclear reactor as I'm assuming, you have a big mass wherever that reactor is, so you probably want it towards the back so the ship is 'trimmed by aft' when it's empty. (idk if this is why, but all the big paddle ships I've seen pictures of seem to have their paddles towards the back.)

nuclear reactors are also dangerous things that you very much don't want to pop a leak or fall out the bottom of your ship in the middle of a busy port. you won't need to refuel as often as a fossil fuel powered ship, but every few years you'll need to open that bad boy up and put some more uranium in there. this is apparently the real limit on civilian nuclear ships: not a lot of ports have that kind of specialist infrastructure. that's the main reason there aren't a lot of nuclear ships outside of the military.

all the same...

I think the odds of nuclear energy being invented but not propellers are pretty slim, especially since moving fluids through pipes is a pretty important element of a nuclear reactor, but if you don't let that stop you... let's suppose we have a setting with abundant fissile material and wood but no fossil fuels and not a lot of iron, and a society that's a lot more on board with nuclear power than people tend to be in our world. the Cancrioth from the Baru Cormorant series, for example. we can assume they've gotten familiar with nuclear tech on land, they're sailing about under wind power, and one day someone says "hey why don't we put that thing on a boat?"

visually I think you could make it look pretty cool. no huge funnels, but instead the reactor is a big metal sphere in the middle of the ship where the paddles are. (a sphere minimises shielding surface area, although there's no need for it to be sphere shaped on the outside!)

how big would these ships be? the smallest nuclear submarine is apparently the Rubis-class, measuring 73m, which is about as long as the Great Western. most other nuclear ships are in the ~200m range. the SS Great Eastern got about that long at 200m, at the tail end of the paddle era. so expect your nuclear paddle steamers to be on the upper end of mid 1800s ships - a little riverboat isn't going to be able to carry that kind, but maybe it would be able to handle one of those tiny space reactors.

in a setting where these ships are common, there would definitely have been accidents. think how bad oil spills are in the real world, and now each one is a mini-Fukushima. sure, there's a lot of ocean to dilute the radiatioactive material. but you could imagine one of these ships running aground, popping open and contaminating a stretch of coastline, or a refueling accident in a port, all sorts of stuff. a setting that is still building paddle steamers probably isn't building their nuclear reactors as safe as modern ones, so cancer rates will probably be higher and you probably have a bunch of infrastructure to filter irradiated water. or maybe they just don't care and this is a grimdark setting where life is really short.

in modern times, we thankfully haven't seen a big nuclear ship get seriously shot at and sunk. but in this setting we're imagining, they probably don't have the kind of long range missiles and aircraft and fancy point defense systems that all those scary modern ships do, so assuming anyone who's nuts enough to build nuclear wooden ships is also willing to go to war with them, battles between these things are probably a lot closer-range and especially horrible. even if you survive there's a good chance of radiation poisoning from nuclear ships catching fire or breaking open.

it's a cool image, and has loads of interestingly fucked up consequences to follow through on, so I say go for it if you want to put nuclear steamers in a story!

#the what if school of multiplying large numbers together and making up a story#engineering#nuclear power#worldbuilding

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pondering

I'm sitting here pondering franchises and stuff I liked as a very young Ram, and remembering how annoyed and patronized I felt at saturday morning cartoons being unable to show gun violence in what was clearly the context of war and struggle of peacekeepers vs. violent lawbreakers; be that on the street level of crime, or like with G.I. Joe, para-military vs. terrorist organizations.

I enjoyed those episodes that asked some hard questions to go with some saccharine display. And I don't even need to get two sentences into THIS paragraph without every 90s kid that follows me correctly interpreting it to mean, "Batman: The Animated Series." 'Cause 90s kids will remember.

The artful gymnastics around the censorship rules and laws and nanny organizations. The balance of political themes that wanted so desperately to give even the gentle echoes of philosophical questions. What is good? Is an organization good, or are we blindly following it in the hopes that it is the good direction? Are the bad guys truly doing what's wrong? The world-building gymnastics to avoid having to use bullets for finality and death as the logical option in a dangerous situation.

While I do agree that some things deserve light touches narratively, such as not showing the piles of glassy eyed bodies and disembodied heads in all their real gory detail after a callback to something like Waco, I absolutely believe that young people who enjoy pulp be it horror, sci-fantasy or straight up fantasy are YEARNING to be allowed dosages of harsh reality to go with the saccharine make believe. If only to better understand the world.

I used to love, as a kid, when cartoon shows would demonstrate things like vehicles, gadgets, even embellish how they work. Like, how submarines work. How radar works. Even if it's not really reliably hard science but just convenient for the plot!

So I sit here and ponder all the themes that I enjoy that would've made wee-me the happiest lad in the world to read about them in either comic book or cheesy limited-animation Saturday Morning Cartoon format, and how one would conceivably make a franchise and story with these subjects.

Something that gently introduced young people to war as a source of entertainment, but also didn't bury the terrible parts under a veneer of patriotic jingoism- while also allowing echoes of it, after prefacing it with, "too much unthinking loyalty to a cause is bad."

Episodes that were borderline classrooms that explained things like how planes work. How boats work. How trains work. Relevant to their adventures! Sometimes show, sometimes tell.

Topical and contemporary jokes, like Carbombya from G1 Transformers.

When this episode debuted I remembered the older kids that let me watch Transformers with them laughing their fucking asses off. I didn't get it when it aired, but after it was explained to me, I just giggled at the audacity. This was a thing, and hoo boy did it make Casey Kasem mad.

Anyhow..

So I think about the potential of all these stories to put into the context of a young-person friendly cartoon show or franchise, and the number of environments, gadgets and gizmos for plots kind of write themselves. A million little primers on things that exist in the world, that serve as almost icebreaking introductions to the concepts of things a young person may not've even known existed. Stuff that makes them aware such things exist, gives them something to ask their older peers about. Like the history of nuclear weapons.

Hell. As a creator, I could even choose, if I felt like it, to have a story entirely about a young person learning about some made up political issue, asking their peers about it, getting WILDLY different stories and interpretations of history and then growing irritated at the partisan people around them filtering the issue through their own bias. As a lesson in dealing and navigating through a bunch of judgemental shallow jerks and biased peers. The lesson ultimately being, "you can't make snap decisions without all the information, and trustworthy unbiased sources are hard to find.. Doubly so when you're young."

These are the things that I would've loved more of as a young person. Tech porn and war stories. Maybe when I make a definitive list of these things, I'll do something about them in writing.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Given that you like nuclear stuff, research and arctics, have you ever taken a look at nuclear icebreakers?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Putin was told that it is impossible to build the flagship nuclear-powered icebreaker "Russia" because Shoygu bombed the plant in Ukraine "Rosneft" is disrupting the construction deadline for the flagship nuclear-powered icebreaker, scheduled for December 2027, which has already been reported to the Kremlin. The cost of the state contract may increase from 128 billion rubles at once by 40-60%. The "EnergoMashSpetsStal" plant in Kramatorsk, Donetsk region, is supposed to supply large hull components for the icebreaker. But Russia bombed this plant last May and happily reported on it."

8 notes

·

View notes