#palestine speaks

Text

Since "Palestine Speaks: Narratives of Life Under Occupation" is suspiciously not available in the US in the form of an e-book, I purchased a physical copy and wanted to share it here for anyone else also unable to get access.

WAFA AL-UDAINI

NGO worker, 26

Born in Deir Al-Balah, Gaza

Interviewed in Gaza City, Gaza

When we first meet, Wafa tells us that her goal is to correct the stereotypical images permeating western media about Palestinian people. Standing in her small office in a dingy building in the middle of Gaza City, this seems like a daunting task, but it's one she is clearly passionate about. She is a small, poised woman with boundless energy wearing a white niqab that covers her head and face. Working with a group of other young men and women, she puts together videos to send to universities around the world featuring ordinary Gazans explaining their hopes and dreams.

She also runs a Facebook page, does regular interviews with the media, and has a wide network of friends around the world. She speaks simply but powerfully in English. When asked about the water quality, she bursts into laughter and asks if we've tried to wash our hair with it yet. Wafa manages to retain her sense of humor, despite Gaza's many deprivations.

Movement of people and goods between Israel and Gaza has been restricted since at least the First Intifada. However, Gaza in the 1990s maintained strong economic and administrative ties to both Israel and the West Bank. Thousands of workers passed through the Erez border crossing from northern Gaza into Israel every day. Travel between Gaza and the West Bank was possible for many Palestinians, even if a bit of a bureaucratic hassle. All of that changed in 2000 at the start of the Second Intifada. Israel began closing the borders to Gaza in what it claims was a response to rocket attacks and suicide bombings. It also destroyed Gaza's only airport. In 2001, Israel began the construction of a massive barrier wall around the entire Gaza Strip and set up a military buffer zone around the perimeter of Gaza, which now takes up 14 percent of Gaza's land area (and which expanded to roughly 44 percent of Gaza's land area during Israel's July 2014 invasion). Israel also significantly restricted movement between the strip and the West Bank for most Palestinians. The border closures devastated the Gazan economy.

In 2005, toward the end of the Second Intifada, Israel unilaterally withdrew its military from Gaza and evacuated all Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip, effectively handing administrative and security control to the Palestinian Authority while opening up some of the closed border crossings to Gaza. However, after the political party Hamas won full control of Gaza in 2007, Israel again closed the borders and imposed a blockade of goods into Gaza by land, air, and sea.

For Gazans such as Wafa Al-Udaini, the border closings would have made life nearly impossible if not for smuggler's tunnels that allowed goods to pass from Egypt into Gaza. Though seen as a military threat by Israel (a means of weapons smuggling to Hamas), the network of over 1,200 tunnels also provided Gazans with food, construction material, medicine, and occasional luxury goods that wouldn't otherwise be available to them.

A LOT OF KIDS SKIPPED SCHOOL TO DEMONSTRATE OR THROW ROCKS

I was born in a hospital in Gaza City in 1988. I'm from a big family - I have five brothers and six sisters. I'm the youngest. The town I grew up in is called Deir Al-Balah. It's right in the middle of the Gaza Strip, about a half-hour drive south of Gaza City.¹

I grew up used to seeing soldiers in the streets while I played. They'd always be chasing someone who'd thrown stones. Especially by the start of the Second Intifada around 2000, there were so many soldiers around all the time.² I remember Israeli soldiers came into our home once to arrest two of my brothers. One brother was seventeen at the time, and the other was just thirteen. They banged on the door until my mother opened it, and then the soldiers hit her on their way in to get my brothers. I was so scared. The soldiers claimed my brothers were throwing stones, but really they might have arrested my brothers just for looking at them funny. That happened a lot. I cried and cried after they left, it was so frightening.

My seventeen-year-old brother was studying for his tawjihi exams at the time, and after he was sent home after being detained for a couple of months, he was too frustrated to continue studying.³ My younger brother was released right away, but he stopped going to school. During the Second Intifada, a lot of kids skipped school to demonstrate in the streets or throw rocks. But I stayed in school and continued to high school during the Second Intifada. Then suddenly, in 2005, Israeli soldiers left Gaza.⁴ For the first time we didn't see the soldiers in the streets, only Gazans. But at the same time, Israel was sealing the borders, so it was hard for people to go to work. Then Hamas got elected, and a lot of aid into Gaza was cut off.⁵

Not long after that, I passed my tawjihi exams and got accepted into Al-Aqsa University in Gaza City. I began studying education at Al-Aqsa around 2006, and then after my first year of school, the blockade started. The first thing I remember was the blackouts. Suddenly, we only had power a few hours a day at most. And there was no propane gas to cook with anymore, so we had to hoard it. Really basic things-formula and diapers, for instance-weren't available, at least at first. But then so much of what we needed started coming through the tunnels. Before long you could get just about anything you wanted-European chocolate, designer clothes, anything.

EVERYWHERE I LOOKED I SAW SMOKE

I was nineteen and still a student during the air strikes in 2008 and 2009. The first day of the strikes, December 27, 2008, was quite memorable. I left the university early because I only had one lecture that day. Just before I reached my house, I heard many explosions. I said to myself, Oh my God, what's happening? There's so much smoke, and I can't see. I ran home and went upstairs to see what was going on from our roof, and everywhere I looked I saw smoke, but I didn't know exactly what was happening-there was no electricity so I couldn't find out what was going on from the TV. I tried to call out to my brothers and my sisters, but they were out of the house and nobody replied.

I was so worried. My neighbors said that Israeli fighter jets had targeted a place in Khan Younis, but some other neighbors said that they targeted a place in Gaza City, and then some others said, no, it was in the south.⁶ Everyone had a different idea about what was going on. I thought, Oh my God, who should I believe? When I looked up, the sky was full of airplanes and helicopters. The first day, the fighter jets bombed hundreds of places, including mosques. They must have targeted every mosque in the Gaza Strip. Our house is close to a mosque, and some of our neighbors were so afraid, because the Israelis could have attacked the mosque at any time and destroyed our building in the process. So our neighbors wanted to go to another, safer place. But we told them there was no safe place in the Gaza Strip. Wherever you went, you would find danger there. The jets ended up bombing the mosque and our house shook violently during the explosion, but nobody was hurt. Only the windows of our building were damaged.

It's a funny story, actually. Okay, it's not funny, but our relatives lived near the border with Israel, and they came to live with us near the coast where it was a little safer. But unfortunately, the night they came to our house, the Israelis targeted the mosque. They were so scared! Our relatives left our house saying, "Oh my God! No place is safe to live! We'd rather die in our own house than die in yours!"

I remember the drones showing up. They buzzed through the skies, and the sound they made was like they were whispering, "I'm going to attack you, I'm going to target your house, your family, your friends." But now we're used to the sound of drones. The last war, in 2012 was more difficult, actually, because in 2008, to some extent, the Israeli army was coming into Gaza. But in 2012, it was just planes. They hit many places, not just police stations and mosques, but houses—really everything in the Gaza Strip.

By 2012, I had graduated and become a teacher. I was a substitute, and would fill in where I was needed. When I was a teacher, I had a very smart student, and I loved her so much. She was an excellent student. She was in the first grade when I taught her. But just about five months after the air strikes in 2012, I met her again, and I was shocked when I saw her. She had lost her mind, and she was walking down the street as if she didn't know anybody. I went to her and asked, "Do you remember me? I was at your school. Do you remember?" The girl looked at me and laughed. She didn't remember anything. I spoke with her mom and she told me the girl's uncle was killed in front of her eyes. The Israelis bombed the place where he was sitting. He was a civilian, not involved in the resistance at all. He was just sitting in front of his house. And, unfortunately, they also traumatized this girl. And really, I was so shocked and so sad when I saw her.

WHEN THERE WAS NO ELECTRICITY, MY MIND WOULD FEEL SO SLEEPY

Since 2007, we've suffered a lot from power cuts. We might get six or eight hours a day on good days. And power might be on in the morning or at night. Every week we get a new schedule, published in the papers and announced on TV or radio. Everything is affected by the power cuts. So it's hard to establish a daily routine.

We never had a generator at my family's house, because I have a lot of nieces and a lot of nephews, and we were so afraid that one of them would touch it and get burned. You know, you hear many stories of generators blowing up and whole families dying. So we preferred to live without electricity than to see our families injured. We wouldn't use candles either because they're dangerous. Instead, we had battery-operated lights that can be charged during the limited time that power is on. They're safer.

I lived in my parents' household until this past year. There were about twenty-five, twenty-six people in our household-mostly my brothers' families. All my sisters had married and moved out. During that time, when the power went out, we'd go to the upstairs of the house. I'd sit with my extended family, chatting and having fun. Sometimes if most of the family was out, I'd read books or write.

But when there was no electricity, my mind would feel so sleepy! This was always a major problem for me. I'd lose concentration for reading or studying for my exams, for example. When I was still a student, I'd have to prepare an assignment for our professor at the university, but I couldn't rely on an internet connection because power would go in and out, so maybe I wouldn't finish in time. Plus, many times the lights wouldn't last for more than two hours, so I had this tiny window to do all my studying. It was a lot of pressure.

As for housework, I couldn't use the washing machine much of the time. I couldn't even make tea with the electric kettle. And I really suffered from not being able to iron my clothes. After I graduated and started teaching, I'd be late to work many times because I was waiting for the electricity to come on to iron. Sometimes I'd go to my friend's house in another city where they had power that day, just to do some ironing.⁹ Since the blockade began, we've had a shortage of cooking gas too. Icannot make sweets or bake a cake. Every time I want to make one, I can't because I don't have any propane gas.

Then there are the water problems. The water is affected by the electricity. There is a water pump in town, so when there is no power, for sure there will be no water. Then the water is polluted. It's saltwater, not for human use.¹⁰ We buy water for drinking and cooking. The other water cannot be used for even animals. We only use it to wash our dishes, clean the house, and wash clothes. Even in the shower, the water ruins our hair. We wash our hair with the sweet water, but not all the time. We can't manage to have a shower with only sweet water. It's not free. So maybe for a wedding, we'll wash our hair well. We have to pay for everything, and a lot of people here in Gaza are unemployed. So they can't pay for the electricity, they can't pay for the gas or the water.

We depended on the tunnels to bring us our basic needs-our food, our clothes, our medicine, everything. When the tunnels were open, we'd go to the store and find all sorts of things. But Egypt and Israel have destroyed the tunnels now, so there's hardly anything in the stores.

MY WEDDING DRESS MIGHT HAVE BEEN BROUGHT THROUGH THE TUNNELS

This year, I got married. Planning for the wedding was a bit of a challenge! One thing I remember was visiting the market to buy my wedding dress. I asked the merchant if all the dresses had been made in Gaza, and he said that many had been sewn in Turkey or Egypt and brought through the tunnels. It's amazing to think of these beautiful dresses being carried fifty feet under the ground through dark, muddy tunnels.

My husband and I were married on March 24, 2014. The day of the wedding, we had to improvise a little. Normally families would prepare food themselves for a wedding in Gaza, but cooking gas was too hard to find. We had to hire a restaurant to cater the wedding for us, since restaurants had an easier time finding cooking fuel. Of course it was all very expensive. We rented a wedding hall, but nobody could afford to take a taxi to the wedding hall because gasoline is expensive, and cabs are nearly unaffordable. We had everyone coming from the neighborhood meet at the bus stop, and we all went to the wedding hall from there. Still, it was a beautiful wedding, and I was happy even in my wedding dress that might have been brought through the tunnels.

Now that the tunnels are closed and nothing can get through Egypt, things are getting harder. Nobody has any money, and basic necessities like food are more expensive than ever. There is so much that needs to change in Gaza, but if I could change just one thing, I'd fix the poverty that's making life so difficult for so many Gazans.

Wafa and her family were especially hard hit by the bombing assault on Gaza that began July 8. They had no water for days at a time, and their access to electricity dwindled. Wafa was unable to use internet or even charge her cell phone, making it impossible to talk with her to get a full update. When she had electricity, she posted brief messages on Facebook and Twitter assuring her followers she was still alive. On July 8, she posted that the Israeli air force sent a warning to the twenty-five family members living in her father-in-law's house (seventeen of whom were children), telling them to leave their home. The family was able to leave before the house was destroyed. On July 25, Wafa wrote, "(Two weeks ago) they bombed my father in law's house, and today Israeli planes bombed my house, our only shelter, for no reason, and no evidence, just to (make) us kneel, but we'll never ever leave our country for them. Pray for us."

---

Footnotes

¹ Deir Al-Balah is a city of about 55,000 people located nine miles south of Gaza City. The vast majority of residents in Deir Al-Balah are refugees who settled in the city after the war in 1948. The city is known for its date palms, and it has a history that stretches back to fortifications used by pharaohs in the fourteenth century BCE.

² The Second Intifada was also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada. It was the first major conflict between Israel and Palestine following the Oslo accords, and it lasted from 2000 to 2005.

³ An exit exam for high school.

⁴ Israel unilaterally decided to disengage from Gaza in 2004, and the plan went into effect in the late summer of 2005. Under Israel's plan, twenty-one settlements in the Gaza Strip would be evacuated, and the settlers compensated. The Israeli military would leave Gaza completely and leave the entire strip to the administrative and security control of the Palestinian Authority.

⁵ After Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza, parliamentary elections were held in 2006, and Hamas won the majority of the seats.

⁶ Al-Aqsa University is one of a half dozen or so colleges and universities in Gaza. It serves around 6,000 graduates.

⁷ Economic sanctions began in 2006 after the election of Hamas, but the full blockade wasn't imposed until a year later, after bloody fighting between Hamas and Fatah in June 2007 drove Fatah out of Gaza.

⁸ Khan Younis is a major city in Gaza located about twenty miles south of Gaza City. It has a population of around 250,000.

⁹ The electricity outages rotate throughout the Gaza Strip, so different cities lose power at different times of the day.

¹⁰ Up to 95 percent of Gaza's water is not fresh. Aside from salt, most of Gaza's water also contains organic and inorganic toxins. Most drinking water is purchased in tanks in Gaza's markets. Salt water is frequently used for showering and cleaning.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't forget about the Palestinians.

Don't forget about them now.

Don't forget about them tomorrow.

Don't forget about them in a week from now.

Don't forget about them in a month.

Don't forget them next year.

Don't forget them in 5 years.

When the history books start to update, don't let them put lies in there.

When documentaries come out, boycott the ones who call this a victory for Israel.

When books release talking about soldier's personal experiences with Palestine, remember the victims. Remember the truth.

Don't forget about what we've seen.

Don't forget about what we've heard.

Don't let them tell lies about Palestine.

Don't forget about the Palestinians when the world tries to make this go away.

#stand with palestine#stand with gaza#free gaza#free palestine#save palestine#ceasefire now#palestine#gaza#isreal#gaza genocide#palestinian genocide#dimond speaks

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

the men and boys are innocent too.

we cry "the innocent women and children" to appeal to the masses, to try and force their sympathy, but the men and boys are innocent too.

I have seen sons crying out for their mothers, their fathers, their siblings. I have seen them break down at the loss of their families. I have seen them cling to their dead and grieve.

I have seen fathers cradle their dead children, seen them kiss their faces and hold their little hands. I have seen them faint with grief when asked to identify the dead. I have seen them carry their sons and daughters. I have seen them fasting to provide what little they can for their families.

I have seen men and boys digging through the rubble with just their bare hands, I have seen them comforting strangers, playing with children, rocking them, hushing them, even if the face of such imminent danger. I have seen them cry, seen them grieve, seen them break down into each other's arms, seen them be selfless, beyond selfless, becoming something I don't have a word for.

I have seen the men who are doctors refuse to leave their patients, even when they have no medicine or supplies to give them, even when they're threatened with bombings. I have seen fathers who have lost all their children pick orphans up into their arms and proclaim them their child so they are not alone. I have seen men and boys digging pets out of the rubble.

the men are innocent too. the men and boys are being hurt and killed too. the men and boys are grieving too. the men and boys are scared too. the men and boys are fighting to save their people too. the men and boys deserve to be fought for too.

#I don't have words to describe how I feel for the men of Palestine#the things I have seen them do after everything they have been through goes so far beyond selfless#what do you call this? this prevailing goodness and willingness to give everything they have and more? what word even touches it?#I don't think there is one#islamophobia has conditioned us to see these men and boys as evil and dangerous#we see this in how we speak about Palestine#and we need to uncondition ourselves#they're just as innocent and of value and good as the women and children#so fight for them#they don't deserve this any more than the women and children#free palestine#palestine

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

Aaron Bushnell died. The active duty US soldier who self immolated in front of the Israeli embassy died of his wounds - he died screaming “Free Palestine” as he burned. He said he no longer wanted to be complicit in genocide. This is the second person to self immolate because of Palestinian Genocide and I hope his story doesn’t get swept under the rug like the first.

#I will not be posting the video here but he recorded himself before self immolating speaking about what he was going to do.#palestine

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

i dont think there is a word yet that can describe how absolutely vile israel is. they killed thirsty children by targeting a water tank.

how inhumane do you have to be to support this, to fund this, to excuse this, to ignore this and pretend as if it isn’t going on?

* news was originally shared by Ramy Abdul, chairman of Euromed Human Rights Monitor

it is also not the first time Israel has targeted water tanks . this is how some Palestinians in Gaza get water supplies since the IDF threatens to shoot them.

#palestine#free palestine#gaza#free gaza#jerusalem#current events#just because you are seeing less news about palestine#doesnt mean that the genocide has stopped#this is why we shouldn’t stop speaking up about palestine

43K notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember the 6 year old girl who was surrounded by Israeli tanks and the red crescent couldn't reach her? Her name is Hind Hamadeh. Here you can hear the phone call her 15 year old sister, Layan Hamadeh, made with the medics. She was killed exactly a moment later including all people in the car, except for 6 year old Hind who was stuck in the car with the dead bodies of her family, Israeli tanks and IDF surrounding her, shooting, preventing anybody to reach her.

That was last night (29.1.24). Today, still nothing. The fate of Hind remains unknown.

palestine red crescent ambulance team went to rescue her yesterday evening, but they have not returned as of now. We lost contact with them about 18 hours ago, and we still remain unaware of their fate and whether they succeeded in evacuating her or not.

Please, share Hind's story as much as you can on any platform. We need to know what happened to her. Put yourself in her place, how terrified she must be. Don't scroll past this.

This is Hind.

#never stop speaking up. please#this is soo important don't just scroll past it read the story listen to the audio and share hind's story#palestine#gaza#israel#important#current events#free palestine#ethnic cleansing#free gaza#gaza strip#gaza under attack#israel apartheid#we are not numbers#spilled ink#video

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

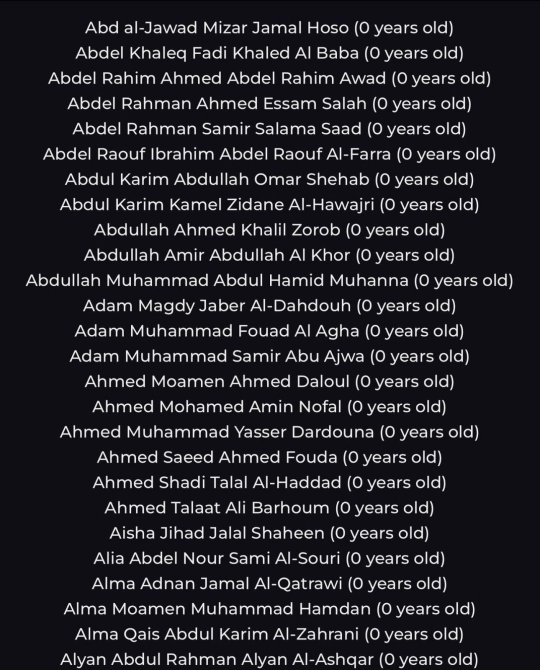

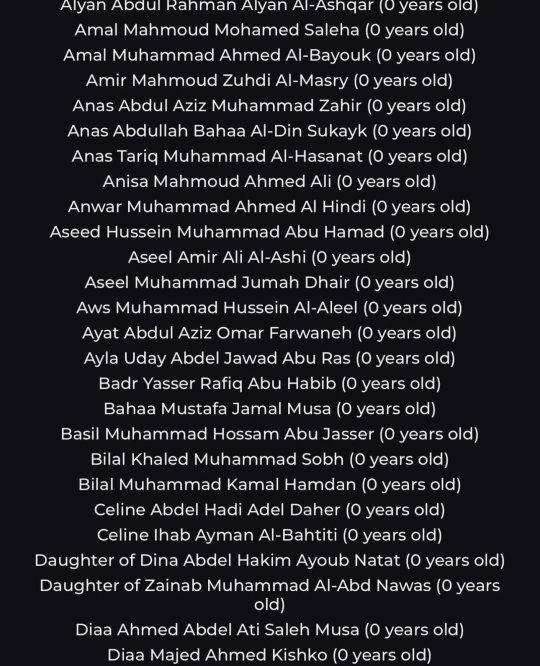

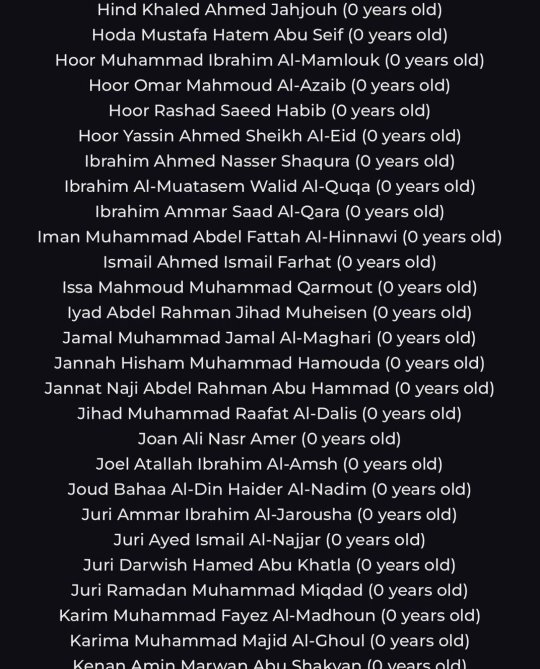

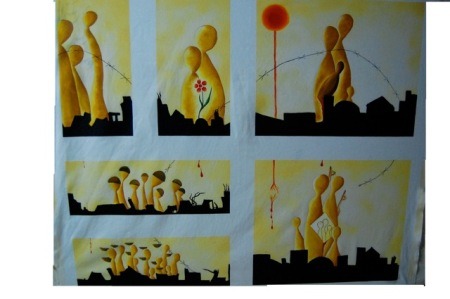

Be furious.

Be absolutely enraged.

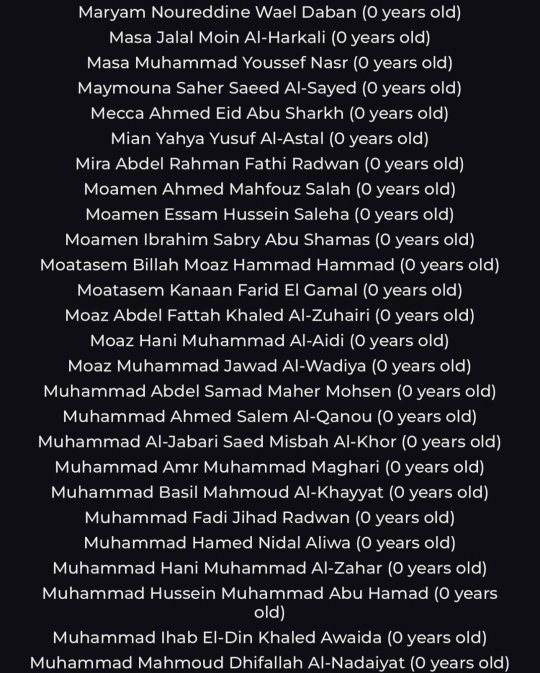

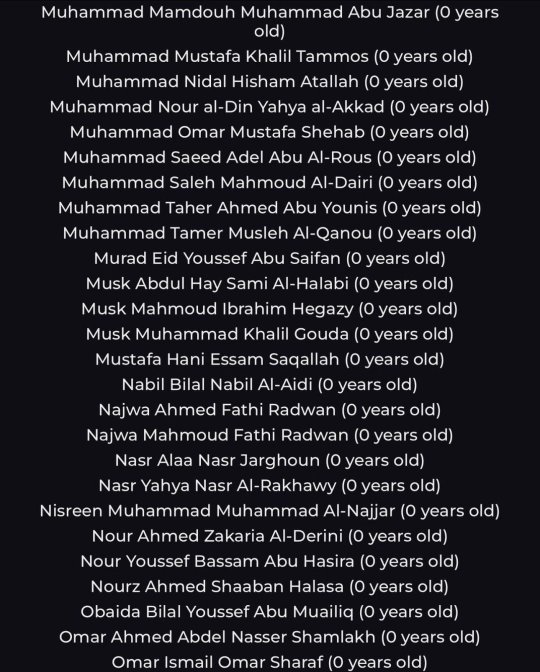

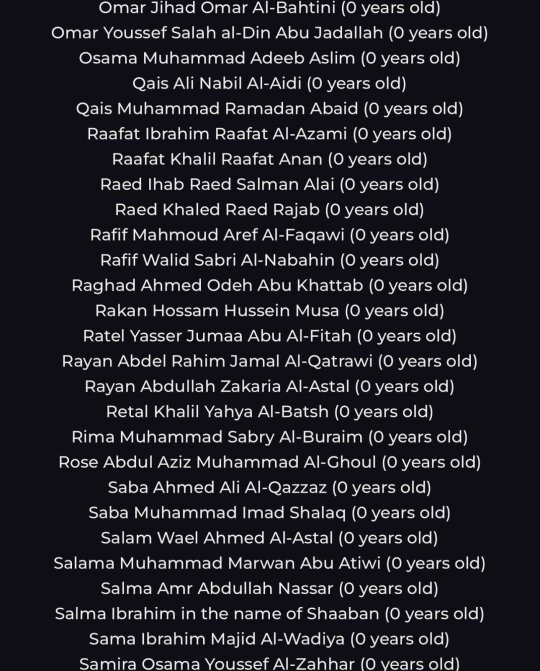

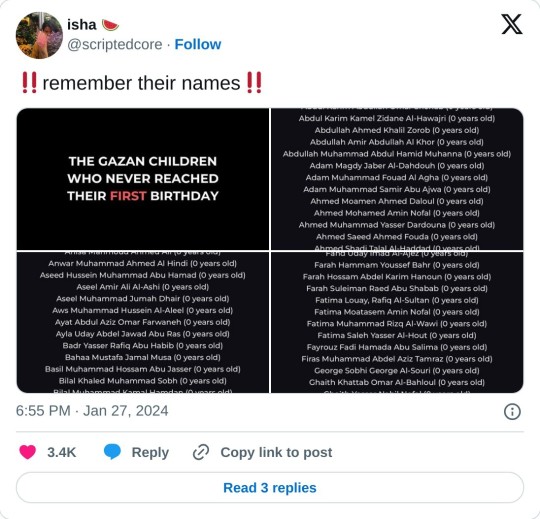

Images put together by wearthepeace on Instagram, found them here

#speak for the ones that weren’t allowed to breathe#free gaza#free palestine#current events#palestine information#support palestine#remember their names#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#pro palestine

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

#free palestine#free gaza#gaza#palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#pray for palestine#genocide#speak tf up!!#ethnic cleansing#israel#israel terrorist forces#ceasefire#permanent ceasefire#america#usa

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

"4 day pause" perfectly positioned right around the weekend when most massive pro-Palestine rallies and protests are organised

They're banking on us quieting down.

But as a reminder to all, a few days of pausing the violence is NOT what we advocate for; we demand to cease all forms of violence, cease the genocide, cease the occupation, cease the apartheid system and most importantly seek justice.

A 4 day pause and then what?

#If you're an organiser or can speak to one I really do hope we keep going at the same speed louder than before.#text: palestine

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Palestinians were killed long before Hamas was formed and would still be getting killed even if Hamas never existed."

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

Since "Palestine Speaks: Narratives of Life Under Occupation" is suspiciously not available in the US in the form of an e-book, I purchased a physical copy and wanted to share it here for anyone else also unable to get access.

MUHANNED AL-AZZAH

Artist, 33

Born in Al-Azzah refugee camp, West Bank

Interviewed in Bethlehem and Ramallah, West Bank

The Al-Azzah refugee camp in Bethlehem is barely more than an alleyway bordered by dozens of small houses jammed closely together. As one walks through the tight corridors, it's hard to miss the haunting murals painted on the walls of the houses. These paintings are taken from the Handala cartoon series created by the late Palestinian artist Naji Al-Ali.¹ In one mural, a girl's hair is twisted into barbed wire. The painting on another house shows gaunt refugees packing their bags and preparing to flee. On another house farther down the street, fat politicians wag their fingers at an emaciated man in rags.

The artist behind these graffitied murals is Muhanned Al-Azzah. With a full beard on his lean face, Muhanned looks the part of an artist. He's soft spoken but funny, and laughter accompanies all of our interviews. Muhanned's family gave the Al-Azzah refugee camp its name when they led the flight from their village in what is now Israel to Bethlehem during the Arab-Israeli War, or Nakba, in 1948.² For Muhanned, as well as many other refugees, the dream of returning to lands lost in 1948 (and during the Six-Day War in 1967) persists, even if little remains today of those farms and villages. This dream of a right to return to property long ago claimed by Israel drives much of the politics of resistance within Palestine.³

Muhanned is a prolific painter, and his work can be found both on the sides of buildings and in galleries around the West Bank. On the day of our first interview, he is preparing a collection of abstract paintings for a show in London. Muhanned's paintings explore different subjects, but his recurring focus is the three years spent in an Israeli prison. At the end of our first interview, he shows us his rooftop studio, his paintings, and the bullet holes in the walls from the night of his arrest.

MY FAMILY HAS BEEN IN THE CAMP SINCE 1948

I was born here in the camp, in September 1981. My parents were born here too. In 1948, my grandparents on both sides left our land, our original village, Beit Jibrin, which is northwest of Hebron.⁴ Even though I've never visited Beit Jibrin, I feel I'm from there. I know all its details, since I've heard so much about it from my grandparents. I know that it's our village.

I know the story of how my grandparents fled the village in October of 1948. One day the soldiers came with guns, planes, and tanks, and everyone in town fled to nearby caves. But some people came back to the village in the night to sleep inside their houses or get things they needed. Then Israeli soldiers entered each house. The first adult male they found inside a house, they brought him to an open space and shot him in front of everyone.The men knew that if they were caught, they might be arrested or shot, so they fled right away. The women followed with whatever they could carry. They didn't have much money, and they couldn't carry much with them. The most important thing was to bring documents to prove that they owned their houses and keep them someplace safe. Most villagers fleeing Beit Jibrin then came here to Bethlehem, where they set up a camp and named it Al-Azzah, after my family.

I have a twin sister, two younger brothers, and one younger sister. Life in the camp has been the same since I was a child. On a typical day, we wake up and the adults go to the main street to eat and talk, to speak about things that are important. Really, it's like cocktail conversation—the news of the day, what's happening with different families, what's happening with the houses in camp. We have political discussions every day, but only in the evenings. In the morning, politics will destroy your brain.

This camp has a little over 1,500 people living in maybe 120 buildings, all packed close together. Everyone knows each other—people spend a lot of time outside because we have such small houses. On the one hand, it can be useful that the community is so close. If a family needs work done on their house, people from the neighborhood will just show up and help. If a family is hungry, a neighbor always has food for them. But you can't expect any privacy here. If you make something good to eat, people are going to know about it and show up for a meal. If you just want some time to yourself, forget about it. You could be sitting in your pajamas trying to rest or think, and someone will show up at your house and say, "Hey, you wanna go get coffee?" It was especially hard for my sisters growing up. If they came home in the evenings even just a little late, everyone in the camp would know they were out late and gossip about them. The girls have an even harder time here than the boys, I think.

THE SOLDIERS WENT CRAZY WHEN THEY FOUND WRITING ON THE WALLS

I grew up dreaming of Beit Jibrin as a paradise. My grandparents always told us about how great life was for them there. Their home and garden in Beit Jibrin were as big as the whole refugee camp where my family lives now. All of my family has hoped that one day we'd be able to return there and live again in our own home.

That's why we were against the Oslo Accords in the mid-nineties.⁶ The accords officially made the land that Beit Jibrin was on part of Israel. For us, we've always wanted a single state between Israel and Palestine so that we can return to Beit Jibrin. We didn't want to accept the Oslo Accords, and some parties in Palestine didn't either. The PFLP opposed the accords and the idea of two separate states that took our land in places like Beit Jibrin and just gave it up to Israel.⁷ The PFLP also supported the right of return, the rights of Palestinians to reclaim land lost in the warduring the Nakba.⁸ So as I grew up, although there wasn't really a single time or event that led me to it, I came to join the PFLP. There were other things I liked about them too—they weren't a religious party. Hamas, that's the big religious party. And Fatah, that's the big party within the Palestinian Liberation Organization, they were always looking for compromise and were willing to accept two states.⁹ But the PFLP seemed like a fit for me-they represented my interests as a refugee from 1948. I'm not going to say much more about their beliefs, though, because I don't want this story to sound like propaganda!

As I grew up, I got more and more into art. My father was an Arabic Literature teacher, and my parents sent me to classes and workshops in Palestinian art at a young age. I grew up seeing art as a way of resistance, through graffiti. During the First Intifada, in 1987, there was no media, there was no radio to cover all that was happening in Palestine.¹⁰ But there were the walls of the houses. They were the only place for media. For example, if there was to be a strike the next day and everyone had to close their shops, there was no simple way to get the message out. So in the night, some people with masks would go into the street with spray paint and write, "Tomorrow, August 9, will be a day of strike for all the shops and schools." So in the morning, everybody could see it.

And every day, when the people went outside, the first thing they did was look at the walls. Sometimes the message was, "Next week, we are gathering for a demonstration on Tuesday." Sometimes there was writing about a martyr, someone who was killed in Bethlehem." The soldiers, when they came in the camp, they'd go crazy when they found this writing fight over on the walls. They would arrest people, and every day there was a who should clean it up. Some people cleaned it, some people refused. And it was very dangerous when artists went out at night to write on the walls.

I was doing some of the same sort of thing even as a teenager. Art was my own individual way of resisting, but we can't do much just as individuals to resist-that just leads to chaos, so that's why I joined the PFLP. More than anything I wanted a chance to go back some day to live in Beit Jibrin, and so a lot of my art has been about being a refugee, about wanting to return home.

After high school, I went to Al-Quds University in Abu Dis to study painting.¹² I also had a chance to study traditional arts in Morocco-decoration, Andalusian art, mosaics, and writing.¹³ When I returned home, I continued to study Palestinian art and culture, and I stayed politically active as well.

I was part of the PFLP through 2004, when I was around twenty-two. I met with other members and organized protests and other campaigns on campus. The Israelis considered the PFLP terrorists and an illegal political party, and so I knew that I could be arrested one day, and maybe even killed. But at that time I was feeling that we were under occupation and somebody must do something to change this situation, and anything anybody could do for Palestine was for the good.

SOMETIMES PEOPLE JUST DISAPPEAR

Late on the night of April 15, 2004, I was home asleep. I slept in an apartment on the roof, where I also had an art studio. My whole family was there, and they stayed on the second floor of the building. We had a friend staying with us as well. My uncle's family lived on the ground floor. Suddenly I woke up hearing megaphones. I knew it was the Israeli military. They were ordering everyone out onto the street, demanding that everyone on the block come out of their homes.

I got out of bed quickly and my first thought was how I could escape. I went to the window and looked out. I saw my neighbors filing out of their homes, and Israeli soldiers were there with jeeps and vans—it looked like they were circling the entire camp. As I watched, the soldiers were moving toward our house, starting to circle it. Then they called out my name through the megaphone. They spoke directly to me in Arabic. "Muhanned Al-Azzah. You cannot escape. Put your hands up and leave the house."

I took my time, if I can speak freely, to hide whatever I didn't want them to take when they searched the house. I hadn't been part of planning any big operations or doing anything violent, but it was against Israeli law to even promote or be part of the PFLP. I guessed they were arresting me because someone had let them know I was organizing for the party.

All I could think was that I might die in a moment, and I asked God for just a few more moments to live. My adrenaline was so high, it wasn't a matter of being strong or not strong, just wanting to survive. But I took my time and put on warm clothes. I knew if I went outside, there would be no time to come back and get clothes. After a few minutes, they started shouting into the megaphone again. By this time, the rest of the people in my house were already outside. I started to see the red laser lights of their guns all over my room. They fired a couple of shots at the house. And they kept demanding that I come out, even as they were shooting at my window. I hid as best I could while I decided what to do next.

After some more time, they brought my mother from the street to my bedroom door. She told me to open the door, that it was safe to go outside. So finally I opened the door and went out with five laser sights hovering over my body. I was terrified.

My neighbors were all outside their houses sitting in the street in the middle of the night. There were maybe fifty people, my family and neighbors, watching and waiting for me.

The soldiers didn't tell me why they were arresting me. They told my family they needed to speak with me for five to ten minutes and then I'd come back. My mother was crying, but she couldn't move because there were a lot of soldiers surrounding her. She couldn't tell me goodbye. My family knew I would come back, but not when-in one hour? One day? One hundred years?

After the soldiers handcuffed me, they put me in one of their jeeps, and we drove for what seemed like a couple of hours. We ended up at Al-Muskubiya in Jerusalem.¹⁴

The room where they took me was small-maybe eight feet by eight feet, white, with air conditioning. There was a white light, a table, and computer—these were the only things in sight, other than a chair in the middle of the room. The chair was fixed to the ground. They cuffed my hands behind the chair and chained my legs and hands to it. I couldn't move a millimeter.

Then they questioned me for two days straight. They'd be asking me questions for twenty or more hours a day, with three or four officers asking the same sorts of questions. They weren't really about anything particular—just questions about my life. They didn't even accuse me of anything. I started to get very confused and disoriented. I fell asleep hundreds of times, but just for a second each time. When they saw that I was nodding off, they'd throw water on me to wake me up. They pushed me very hard. Twice a day, they brought me beans and released one of my hands. They said I had two minutes to eat. After two days of being awake, sitting upright, not moving, my legs and hands became numb.

They'd also tell me things to break me down. They told me that my house had been demolished, that my family had been killed. They brought pictures of my younger brothers and told me they'd been shot. I didn't really doubt them, and I assumed I'd be killed too. Sometimes people just disappear, and I thought I'd be one of those people. I started to feel lost, just completely out of focus.

Finally on the third day, they let me know I was being held because of my association with the PFLP and because they suspected the PFLP was planning an attack on Israel. They wanted me to talk about it. I didn't know anything about an attack, but I also didn't want to give them any names of other people in the PFLP that I knew, so I stayed quiet. If I gave them names of other PFLP members, they would arrest them too. Sometimes they'd interrogate me for just a few hours a day, sometimes for twenty hours or more. When I wasn't being interrogated, they sent me to a small, gray room—less than six feet by six feet. If I tried to lie down to sleep, my head and legs would be pressed against opposite walls. If I caused a problem in this room, like making too much noise, they'd cuff me and leave me bound up for five or six hours. They gave me just enough food to keep me alive. After a week, they gave me a few cigarettes but no lighter.

Sometimes in between long sessions, they'd put me in a cell with other Arab men. These men would tell me their stories, say they were from Hebron or whatever, and then start asking a lot of questions about me. It was pretty obvious that these men were informants, part of the interrogation, and that their job was to get me to talk when I was feeling less scared, more relaxed. They'd say things like, "I told the Israelis everything, and now I can sleep. If you tell them everything, they'll be easier with you.”

I never saw sunlight. I never knew what time it was—evening, morning? I would sleep for a few hours, and I didn't know whether I slept for one hour or for one hundred hours. I didn't know what day it was. I didn't know anything. I spent a lot of time alone, and my mind was going, but I had something inside that pushed me to stay strong.

JAIL IS A TIME TO MAKE AN EVALUATION OF YOUR LIFE

After about four months in Al-Muskubiya, I was taken to military court.¹⁵ There were around twenty soldiers there, all with guns. I felt alone and threatened, and I think this was part of the game. They wanted to scare me in any way they could. But I felt strong, because I was not just one person, I was one with the Palestinian cause. I was a civilian, I had the right to resist occupation, and I didn't care about what they would accuse me of. I didn't listen to what they said, really. They charged me with political activism, activity against the Israeli state, and being a member of an illegal political party—the PFLP. They had no evidence against me that I was part of any attacks on Israel, just that I had promoted the PFLP. They gave me three years.

I was taken to a prison near Be'er Sheva around August of 2004, not quite four months after my arrest. The amazing thing was that the route that the prison bus took to get to Be'er Sheva took me right through the site where my home village, Beit Jibrin, used to be. I had never seen it before, so I tried to see as much as I could as we passed through. When I saw the village, I was shaken. My grandparents had said so many good things about it, about the good old days. I had dreamt of it as a paradise. But the land was barren except for a few trailers that make up an Israeli settlement. There was an old mosque, and lots of ruins—old stones and parts of buildings that were thousands of years old.

My grandparents had been driven from their home by force, and here I was seeing it, again only by force. It was hard. I was alone. It reminded me that I wasn't with my family, and I always imagined I'd see the village some day with them. It was a bad, lonely feeling. It was almost like I had woken up from a coma—I couldn't make sense of everything that must have changed from that time before 1948, a time I knew only in my dreams.

Life at the prison at Be'er Sheva took some time to get used to. I spent most of my days inside my cell. The cells were about ten feet by fifteen feet, and there were seven people living in each one. There were bunk beds for each of us, but we couldn't come down from the beds all together at the same time because there wasn't enough space to stand. For example, when we wanted to clean the room, only two people could do the cleaning.

Everyone was from different places. Some people were very old, some people were young. Some had ten or twenty years in jail, and some had one year. If you wanted time alone, you had to pretend you were sleeping. From the first day, I began to get to know the other prisoners pretty well. Social relations in Palestine are very close—there are strong connections between Palestinian people. So you can find somebody in jail whose brother or friends you know and you can speak with him.

We had two opportunities to leave our room-once in the morning and once for an hour in the evening. We walked outside in the prison courtyard. In my section there were over a hundred people, but only forty people could fit in the courtyard. So forty people entered and walked in a circle in rows, four to a row. We had one hour, so we walked half an hour clockwise and half an hour counter-clockwise. One of the prisoners would clap when half an hour was up and then we'd walk in the opposite direction. As we walked, I thought, This is the circle of our life, of every day. And when we start at this point, after one hour we will be back at the same point.

The courtyard was mostly covered, so there was barely any sunlight even on bright days. Most of the prisoners started to feel sick, just from lack of sun. There were some small windows in the hallways outside the rooms, and if you wanted to get sun, you had to go there in the morning. But there was a pecking order. I was new to the prison, and there were older people who had been in jail for twenty years and they were sick, so it was more important for them to be in the sun than me. I didn't really see any sun for over a year.

Slowly, my mind started to bend and adapt to life inside cell walls. Jail is a time for each Palestinian to sit with himself, a time to make an evaluation of his life. And it's an important, powerful experience to have the time to learn and share stories with people in jail.

Sometimes we found somebody sitting by himself in the room with his mind on the outside world, and we knew we had to keep him from feeling alone. If any of us prisoners began to live with our mind outside the jail, we would start to feel down, depressed. So we would give each other a little time to think those thoughts, but if we saw someone looking pensive, we would go to him after maybe half an hour and start joking, discussing things, anything, just to keep him from getting lost within himself.

I was in isolation a few times—sometimes for a few days, sometimes for a week. This could be for something like having contraband, like cell phones. It was very bad in isolation. There was no bed, just a small room with a mat on the floor that you slept on. You had five minutes to go to the bathroom and do what you want, shower, clean—just five minutes. And then you came back to the small cell. Some people spend years in isolation.

There were often conflicts with the guards inside the jail. We would begin to shout or knock on the door and they would come and shoot us with pepper bullets.¹⁷ The bullets cut your skin and the pepper goes in.

The guards searched the room several times each day. When they did these searches, they would bring at least nine or ten soldiers to every room. Sometimes they came just to search. Sometimes they came to bother us. They might come at three in the morning, when we were sleeping. Within a second they'd open the door and nine soldiers would enter with their guns, shouting, "Get down! Put your hands up!"

Still, we were able to hide things sometimes. One thing that was important to us was a cell phone. We used the phone to get news, to talk to our families. At one point, it was my job to hide the phone every evening. We would take it out at six o'clock in the evening and use it until ten, twelve at night, and then hide it. I hid it in a lot of places—for example, we put it in the floor. We cut out a little bit of tile and put it underneath. But you had to be very fast and careful because when the guards came, they searched everything, even the floor sometimes. One time, they brought in a metal detector, and they were able to find our phone that way. They took it, and as punishment they took away visits for two months.

THEY WANTED MY FAMILY TO FEEL LIKE THEY WERE IN JAIL TOO

During the whole time I was under interrogation in Jerusalem, my family had no idea where I was or what was happening to me. Toward the end of my time in Jerusalem, someone who knew me from the camp spotted me as I was being escorted down the halls to or from interrogation. This guy told his mother about me when he got out, and then his mother told my mother where I was. Then my mother and father went to the International Red Cross to ask for permission to see me.¹⁸ Finally, two months after I was transferred to Be'er Sheva, they came to visit me.

When I first saw them, my mother had been crying. She was behind a pane of glass and we spoke into telephones. It was difficult for me and it was difficult for her, because we knew she was going to leave after forty-five minutes. During the visit I told them, "It's okay, I'm good. We have a big space, and TV, and the food is good. We have meat, we have chicken every day, we have juice, we can drink what we want." And all of that was a lie to make her feel better about the situation. It wasn't easy, because I knew if anybody was released from jail, they would tell her what was really going on. And I knew that she knew I was lying, but she didn't want to say it.

But she wanted to keep my spirits up as well. I kept asking about what was happening outside, and she told me everything was good—this friend was getting married, this one was about to graduate from college. There were a lot of bad things she didn't tell me about. I know she lied because she wanted to give me a nice picture of the outside. So we were lying to each other just to keep each other happy.

My parents came twice a month. It was hard for them to visit the jail. They'd get on the bus at four in the morning and wouldn't arrive until noon, and the visits were only forty-five minutes long. They wouldn't get home until at least seven or eight at night. Sometimes when they came, the prison guards told them, "He's not here, we took him to another jail," or "He's in court." It wasn't true. Once, another prisoner coming back from a visit told me, "Muhanned, your family is waiting outside." I changed my clothes for the visit and waited for my turn. But every time I asked the soldier about it, he said, "Not now, not now." Finally, visiting hours ended and the soldier said, "Your family didn't come." I told him my family was outside, and he went to check. When he came back he told me they had been there, but that they had to leave because visiting time was over.

You know, I didn't want my family to come. I didn't want them to spend all these hours just to come for forty-five minutes and sometimes not even see me. It was a punishment for my family. The Israeli authorities wanted to make my family feel like they were in jail too. So, one night, I used the mobile that we had hidden to tell them not to come anymore.

A couple of months after my parents first started visiting, my two younger brothers were arrested as well. The older of the two was sentenced to two years. He was nineteen. My youngest brother was given administrative detention for a few months-he was just sixteen at the time.¹⁹ I was the first, but my father and mother now say the Israelis have a map of the house since they've visited so many times.

When I was arrested, it was hard for my family. My mom didn't leave the house for a while. But after she came to visit me the first time, she began to meet people and she began to see there were people who would spend all their lives in jail. They had families, wives, and children that they'd never see. So this gave her some perspective. She thought, My son, at least he will get released. And she felt the same way about my brothers. I felt the same way, too. There were a lot of people who had twenty-year sentences. So I felt I was just in prison as a tourist.

After a year and a half, in the spring of 2006, I was moved again, this time to the prison in Naqab.²⁰ There I lived in a tent in the desert for eight months. There'd be maybe twenty of us in each tent, and huge walls around each section of tents. The walls were the same height as the apartheid wall.²¹ We were in the desert in June and July, the hottest time of year, under the sun all the time. It was like 104 degrees Fahrenheit, but we were just out in the sun. All the prisoners, they spent their time close to the wall trying to get shade. And there were so many bugs—mosquitoes, bed bugs. It was terrible. The only good thing was the other people, the other prisoners I met.

After the prison in the desert, I was transferred again to Shate Prison, near Nazareth, not long before my release.²² I spent a few months there. Then finally, in 2007, I was released.

I MADE MY ROOM LOOK LIKE THE ROOM IN JAIL

I knew the date I would be released, but not the place. They released me in Jenin.²³ It was very far from home, and I didn't have any money. I didn't have anything. In 2007, the situation in Jenin was not easy. I borrowed a phone from a taxi driver to call my family and tell them to come and take me back to Bethlehem.

When I got home, I found a hundred friends, family, and neighbors waiting for me at the camp. All of them wanted to carry me on their shoulders or to hug me. I had spent the last three years speaking and living with a maximum of seven people, and to be around so many people all of a sudden, so much commotion, was overwhelming. I was happy, but it was a little too much. Everyone seemed to be talking at once, and I couldn't focus.

The first day I slept in my own house, I woke up at six in the morning, alone. I had gone to sleep at four or five o'clock in the morning because I was celebrating with my family and friends, but I woke up at six because every day while I was in jail, we woke up at six to do the count.

For three or four months, I wanted to be alone. I didn't want to speak with anybody. I didn't want to meet anybody. I made my room look like the room in jail—I filled it with some boxes to make myself a smaller space, and I had coffee and everything I needed around me in that one room.

Everybody who goes to jail has a lot of problems when they get released. For me, I had trouble speaking with more than one person at the same time, and sometimes I needed a long time to focus on all the details of a conversation. Also, sometimes I had a problem with—I don't know how to say it—feeling secure. For example, if I heard a voice outside, I had to go and see who was talking. If somebody opened the door to my family's house, I had to go and see who it was. Sometimes I'd be sitting in some public space with friends and I'd notice a person sitting behind us, staring at us. My friends, who hadn't been to jail, wouldn't notice that.

But still, I tried to get back into my life. I wasn't as active anymore with friends or politics. But I started school at Abu Dis again in 2008. I was going back to my old art program, the one I'd been in when I was arrested in 2004. My family is educated, as are many people in the camp. Work is not easy to find, and we are not in a normal country. So you must study to have something to do. Having a B.A. here in Palestine is like the same level of qualifications as finishing high school somewhere else. I have four uncles—one has a Ph.D. from Rice University, one has a Ph.D. in education, one is an engineer, the other finished his master's. Two of my aunts are getting their master's. It's the only way to make a living. My twin sister finished her master's and is working for her Ph.D. So getting a degree was very important to me.

Still, it sometimes felt like the hardest thing in my life to go back to university. I had been out of university for almost five years, and when I came back, all my old friends were gone. People who had been studying with me, they were now my professors at the school. I couldn't spend time with other students to discuss anything because they were five or six years younger than me. They felt the things they were discussing were very important, but I didn't care if I had Ray-Ban sunglasses or how much my watch cost or whatever. So I found a distance between myself and others. To be honest, I skipped a lot of classes.

I wasn't like that before jail. Before jail I was happy and proud to go in the morning to lectures, to attend university. I was proud of the books I was reading. But after jail, I was ashamed. I didn't want anybody to see me, having me going to school. I felt too old and that this time was finished for me.

But I also met someone, a woman who was about six years younger than me named Aghsan. Before long, we got engaged. But for a girlfriend didn't change much—it was still hard to adjust to being out of prison. For the Palestinian, the occupation changes everything, controls everything your mind, your life. Aghsan is from Ramallah, and it should have taken me one hour to go and visit her coming from Bethlehem.²⁴ But at the checkpoint, Palestinians are stopped for hours, even if you are just going to meet your girlfriend. At the checkpoint you don't know how long you will stay.²⁵

I had to tell the soldiers at the checkpoint that I had been in jail, because if I had not been honest when they asked, they would have checked and it would have been a problem for me. They asked a lot of questions. And sometimes they didn't ask anything, they just told me to get out of my car and made me wait. It depended on the soldier. If the soldier had a problem with his girlfriend, if he was having a bad day, he would make it a bad day for me. So during our engagement I would just go from Bethlehem to Ramallah to see my fiancée for a couple of hours and then head the opposite way to come back, and this was my whole world. After a while, I started to think the story of Romeo and Juliet was easier than my story. I thought, Why am I in love with a girl in Ramallah? London and Ramallah seem like the same distance. Is this really worth it? Sometimes I think the occupation will even stop love.

I also have had trouble at work because of my time in prison. I got a job at an organization called Addameer, a prisoner support and human rights association, a little after I started school.²⁶ It's difficult for me when I feel I'm under someone else's control. I don't want to be under control. This is a problem I have at work. I don't like signing in every day, having my actions determined by someone else.

I BELIEVE ART IS RESISTANCE

When I came back to university at Abu Dis, I spoke with my art teacher. I told her that I wanted to make art about the jail. She supported me because she said there were few artists like me who had experienced jail, even if there were a lot of artists who made prison the focus of their work. Palestinians and international organizations are always speaking about political prisoners in Palestine. Some Palestinian artists make posters, drawings, paintings, and they often depict prisoners as very big and strong, as guys who can destroy the walls of the jail. But I wanted to do something different. I wanted to speak about prison, about life from the eyes of a prisoner. My art was about how the prisoners see the outside world. I painted the bars of the windows, because that's the view we knew. We never saw a view without the fence, without the windows. And when I went to visit my family, my mother, she was on the other side of the glass. So when I was looking at my mother, I saw my mother, but her face was never completely in view. I've painted glimpses of faces and people and houses and cars on small square canvasses to represent the way the outside world appears to prisoners, seeing the world through these little screens, through small glimpses.

I had an exhibition in London in 2011, and also one in Jerusalem, and a third one in Bethlehem. I am proud of that. But I know these paintings I made, somebody can take them for money and put them in his house and close them up. So the maximum number of people who will see these paintings is ten people, twenty people. But I believe that art is for all levels of society. I am from a refugee camp, and I am drawing for the poor people in Palestine, not for the bourgeoisie. I'm not doing a painting to keep it inside the house.

After I was released from jail, I started doing graffiti. Sometimes I and a couple of other artists used stencils, because we did a lot of painting in places where we are not allowed to paint, so we had to go fast. I did graffiti in the main street to let everybody see the drawing.²⁷

I believe art is resistance. The graffiti in Palestine, it's not like the graffiti in any other place in the world. Because when you write something on the wall, this means it has a connection with the First Intifada and the revolutionary time.

When I make my art, it feels that I am giving something to my homeland and sending my message to the rest of the world. I paint because I'm speaking for thousands of people nobody knows about the people in jail. Many of them have been living for thirty years or more in jail. Few people speak for or about them. There are 12,000 people incarcerated in military jails. Why people don't know about them, I don't know.

If you live in Palestine, you have big problems—much pain, much suffering. I am painting to change that, to help ease the pain. Many of us are not fighting with guns, but we find our own way to resist. We may lose our lives or freedom, but we are working for the lives of our next generation.

---

Footnotes

¹ Naji Al-Ali (1938-1987) was a political cartoonist who criticized Palestinian politicians and the state of Israel. A recurring character in his artwork was Handala, a faceless ten-year-old Palestinian boy whose story represented the Palestinian refugee experience.

² Members of the Al-Azzah family had been leaders in the region of their former village ever since revolting against Ottoman rule in the nineteenth century. After many of the residents in their community fled to Bethlehem in 1948, the refugee camp was named after them, in recognition of their prominence.

³ From the glossary -

two-state solution: A proposed peace plan that would create a separate Palestinian state and define clear boundaries between Israel and Palestine. Peace process plans since the First Intifada between Israel and the Palestinian Authority have targeted a two-state solution rather than a one-state solution.

⁴ Beit Jibrin was an Arab village located thirteen miles northwest of Hebron and twenty-five miles southwest of Jerusalem. Before 1948, the population was a little under 3,000. The village was depopulated during Israeli raids in the 1948 war, and there is currently an Israeli settlement on its former location called Beit Guvrin.

⁵ From the glossary -

Arab-Israeli War: A conflict between newly formed Israel and neighboring Arab nations that has shaped Israeli-Palestinian relations since 1948. Tensions between Jewish and Arabic residents of the British Mandate in Palestine (1923-1948) were high leading up to the 1947 United Nations announcement of partition of the region into a Jewish nation (Israel) and a state for the region's non-Jewish Arab population (Palestine). The Arab League, an organization of neighboring Arab countries, opposed the partition plan, and declared war on Israel in May of 1948, immediately after Israel officially declared statehood. The war between the Arab States and Israel lasted until armistice agreements in the spring of 1949. During the war, more than 750,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes, and Israel annexed 60 percent of the land that had been demarcated as Palestinian territory under the 1947 U.N. partition plan. Palestinians refer to the war and its aftermath as the Nakba, or "catastrophe," and much of Palestinian politics today is driven by the claimed right of families to return to lands they were expelled from in 1948.

⁶ From the glossary -

Oslo Accords: A series of negotiated agreements between the leadership of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization starting in 1993, during the height of the First Intifada. The goal of the accords was to institute a peace plan and create an interim Palestinian government in anticipation of eventual Palestinian statehood. The Oslo Accords led to the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (subsequently called the Palestinian Authority), a temporary governing body formed from the administration of the PLO.

⁷ The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) was formed in 1967.

⁸ The "right of return" refers to a political position that Palestinian refugees and their descendants should be permitted to reclaim land and property that they were driven from in the wars in 1948 and 1967.

⁹ From the glossary -

Fatah: A left-leaning political party that makes up the majority of the Palestinian Liberation Organization coalition. Fatah was founded in 1959 largely by Palestinian refugees who had been displaced by the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. After its founding, Fatah had several militant wings and conducted a number of military actions against Israel, and Israel targeted military and non-military elements of Fatah.

Hamas: A political party founded in 1987 as an offshoot of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas is a Sunni Islamist political party, and its stated aims are to liberate Palestine from Israel and establish an Islamic state in the region that now encompasses Israel and the occupied territories. Hamas gained greater influence in the early 2000s, surging to power on dissatisfaction with the Palestinian Authority, which many Palestinians viewed as corrupt and willing to cede too much to Israel in peace negotiations. After winning parliamentary elections in the Gaza Strip in 2006, Hamas solidified its power in Gaza after violent skirmishes with opposition party Fatah. By 2007, Hamas had effectively taken control of Gaza, driving the Palestinian Authority from power there. Because Israel views Hamas as a terrorist organization, it imposed a crippling economic blockade on the Gaza Strip following Hamas takeover. In the spring of 2014, Hamas and Fatah announced a political reconciliation, though to date Hamas remains the sole power in Gaza.

Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): The Palestine Liberation Organization is a coalition of political organizations that was formed in 1964 with the aim of creating an independent Palestinian state. The PLO was first formed in the summer of 1964 during a meeting of the Arab League, and was composed of numerous political and military factions, including Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Yasser Arafat led the PLO from 1969 until his death in 2004. The coalition was considered a terrorist organization by Israel and the U.S. until 1991. After negotiations known as the Oslo Accords began in 1993, the PLO became the official governing and diplomatic body of the Palestinian people. In 1994, the Palestinian Authority was formed out of the organizational structure of the PLO and chartered as an interim government of Palestine for the duration of peace negotiations between Israel and Palestine.

¹⁰ The First Intifada was an uprising throughout the West Bank and Gaza against Israeli military occupation. It began in December 1987 and lasted until 1993. Intifada in Arabic means "to shake off."

¹¹ Palestinians use the term "martyr" generally for anyone killed by Israelis, not necessarily someone who died while fighting. Although originally a religious term, it is now used by religious and secular Palestinians alike.

¹² Al-Quds is a university system with three campuses in the West Bank, including one in the city of Abu Dis, which together serve over 13,000 undergraduates. Abu Dis is a city of around 12,000 people just east of Jerusalem. Al-Quds is the Arabic name of the city of Jerusalem.

¹³ Muhanned is referring to the art and culture from Spain during the 800 years when it was under Muslim influence. In 710, Islamic armies succeeded in conquering large areas of Spain within a short span of years. The conquerors gave the country the name Al-Andalus.

¹⁴ Al-Muskubiya ("the Russian Compound") is a large compound in Jerusalem that was built in the nineteenth century to house an influx of Russian Orthodox pilgrims into the city during the time of Ottoman rule. It now houses a major interrogation center and lockup as well as courthouses and other Israeli government buildings.

¹⁵ Up to this point, Muhanned was being held in administrative detention, a system that allows Israel to indefinitely detain Palestinians without specific charges.

¹⁶ Eshel Prison, near the Israeli city of Be'er Sheva, is a maximum-security facility that was opened in 1970. Be'er Sheva is a city of over 200,000 people located sixty miles southwest of Jerusalem.

¹⁷ Pepper-spray projectiles are weapons sometimes used to incapacitate and control crowds. Each projectile ball fired from the weapon contains chemicals such as capsicum, which is also used in pepper spray. Though they are intended to be non-lethal, deaths have been reported from the use of pepper-spray projectiles.

¹⁸ The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an organization that monitors prisoner rights around the world, among other functions.

¹⁹ From the glossary -

administrative detention: A legal procedure under which detainees are held without charges or trial. Some forms of administrative detention are legal under international law during times of war and while peace agreements are negotiated between opposing factions. Many of the detainees in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, are held by the United States in administrative detention indefinitely, and the procedure has also been employed in Northern Ireland against the Irish Republican Army and in South Africa during the apartheid era. Administrative detention was employed by the British against Jewish insurgents during the British Mandate of Palestine, and the Israeli military adopted the practice at the formation of Israel. In 2014, Israel has held as many as 300 Palestinians in administrative detention. Though each term of detention is limited to a set number of days (usually a single day to as many as six months), detention can be renewed in court, meaning detainees can be held indefinitely without trial or charges. Though article 78 of the Fourth Geneva Convention grants occupying powers the right to detain persons in occupied territories for security reasons, it stipulates that this procedure should only be used for "imperative security reasons" and not as punishment. During the Second Intifada, Israel arrested tens of thousands of males between the ages of fourteen and forty-five without charges.

²⁰ The Ktzi'ot Prison is a large, open-air prison camp in the vast Negev desert (Naqab desert in Arabic), located forty-five miles southwest of Be'er Sheva. Ktzi'ot was opened in 1988 and closed in 1995 after the end of the First Intifada, and then reopened in 2002 during the Second Intifada. According to Human Rights Watch, one out of every fifty West Bank and Gazan males over the age of sixteen was held at Ktzi'ot in 1990, during the middle of the First Intifada.

²¹ This is a reference to the barrier wall separating Israel from the occupied Palestinian territories, which in many places is twenty to twenty-six feet high and made of triple-reinforced concrete.

²² Shate Prison (shate means "hot pepper" in Arabic) was opened in 1952 and houses 800 prisoners.

²³ Jenin is a city of almost 50,000 people on the northern border of the West Bank. It's located over sixty miles north of Bethlehem.

²⁴ Ramallah is the de facto administrative capital of Palestine. It is about thirteen miles north of Bethlehem.

²⁵ From the glossary -

checkpoints: Barriers on transportation routes maintained by the Israeli Defense Forces on transportation routes within the West Bank. The stated purpose of the checkpoints in the West Bank is to protect Israeli settlers, search for contraband such as weapons, and prevent Palestinians from entering restricted areas without permits. The number of fixed checkpoints varies from year to year, but there may be as many as one hundred throughout the West Bank. In addition, there are temporary roadblocks and surprise checkpoints throughout the West Bank that may number in the hundreds every month. For Palestinians, these fixed and temporary checkpoints—where they may be detained, delayed, or questioned for unpredictable periods of time—make daily planning difficult every month.

²⁶ Ramallah is the de facto administrative capital of Palestine. It is about thirteen miles north of Bethlehem.

²⁷ Most of Muhanned's murals are done with the permission, and even at the request, of the property owners.

#palestine speaks#palestinian voices#book exerpt#part 13 of 16#the israeli soldiers going crazy at the writing on the walls reminds me of king belshazzar and daniel from the bible

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WORLD STANDS WITH PALESTINE 🇵🇸

#FREE PALESTINE#!!!!!!#its been over 70 years#and the world is finally waking up#better late than never#proud of everyone for speaking up!! protesting!! sharing on social media!!#proud of people who wont stand for genocide and apartheid#palestine#pro palestine#politics#mine*#gifs*

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

please consider how you engage with aaron bushnell's death. you may react to it as you will, but it's crucial to remember that his death was specifically a call to action. it was not meant solely to shock but to draw attention to a vast moral hypocrisy: that to many, a soldier dying in a campaign backed by the U.S. government is noble, even if the soldier kills innocents to do so, even if the cause is morally bankrupt--but this? this is insanity. a man taking his own life, on his own terms, in an attempt to help others while hurting nobody else, is somehow less rational and more horrifying than the mass killing of civilians.

of course aaron's death was horrific. but as he said beforehand, it is realistically no more horrific than what's happening in gaza. if we can't stomach this, then why can we stomach children being bombed? thousands being starved? for all that self immolation is, it brings death in a matter of minutes. it is a fraction of the amount of pain, fear, and grief that people in gaza are experiencing. it's just that we are able to quantify it. and this tiny, quantifiable sliver of horror is still so unbelievably awful. how can anyone bear to think about anything else when this horror is happening a millionfold in palestine? this is the question aaron bushnell was asking. and he wanted you to face it, head-on, watching him burn to death.

I've been seeing people make fanart. minimalist graphics to sell on t-shirts. to commodify his death, to mythologize it not a day afterwards, is not only in poor taste but a hindrance to his message. the answer is not commodification, nor is it defeatism, nor is it rejoicing in his death. if you want to honor aaron's legacy, take action. channel your horror and your outrage into making a material change. this wasn't about him. this was about palestine. remember that it was always about palestine.

#aaron bushnell#I didn't want to make another post about this but#watching that video changed me irrevocably.#there have been many instances during this genocide that I've felt that way. and today is another one of those days.#I have been radicalized permanently by these events.#people speak to aaron's death as a result of hopelessness#but I see it as him having profound hope. he had hope that his death would change things.#and it is up to those still alive to ensure that happens.#free palestine

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

While I totally applaud South Africa on taking the israeli occupation to the courts, I think ppl should also keep in mind that the SA government has also been complete shit for places like Sudan. They may had condemned the Israeli Occupation but, in a show of blatant hypocrisy, they've also personally welcomed people greatly responsible for the genocide in Sudan and their president has "condemned" that genocide about as much as Joe Biden has the one in Palestine.

So yeah, people are going to be rightfully pissed. That doesn't mean they don't believe in a free Palestine; it just means they want to be free too and the hypocrisy is hurtful to say the least.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

#salty speaks#free palestine#palestine#free gaza#gaza strip#to anyone who uses being queer as an excuse to go not be pro palestine#whole heartedly#fuck you

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

by the way your voice always matters in the fight against injustice. every single time you speak out against an injustice it matters. it sheds light on it. it empowers others to speak up. it matters

#and speaking up can and should mean amplifying the voices of those being oppressed#conversely. your silence is as political an action as your voice#free palestine

14K notes

·

View notes