#precolonial africa

Text

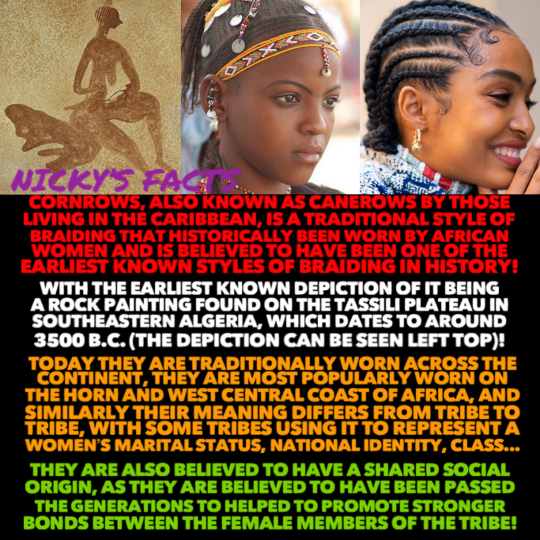

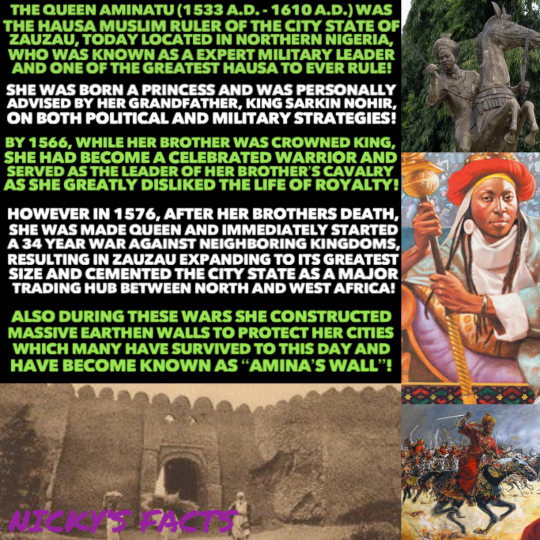

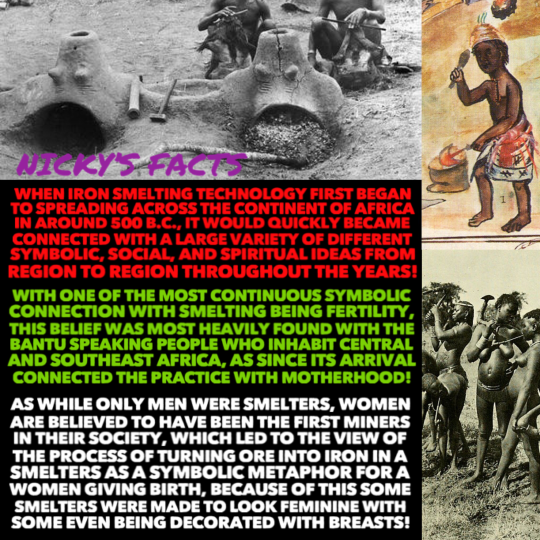

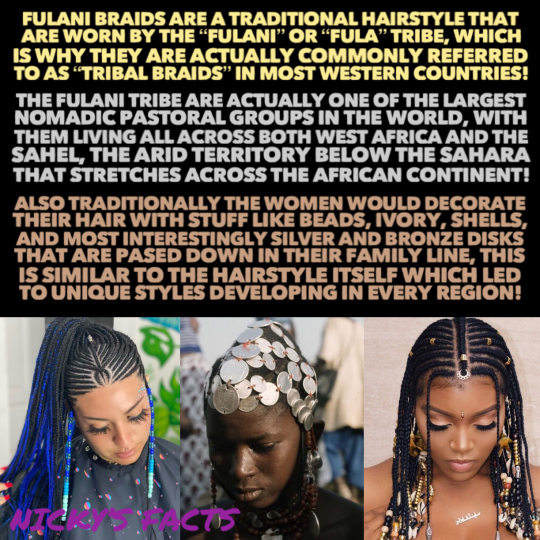

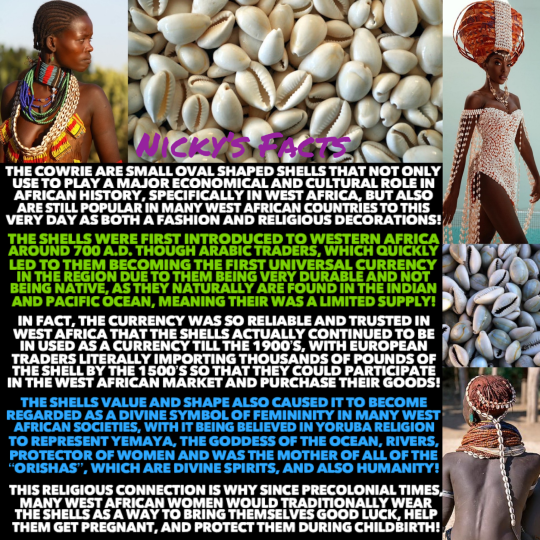

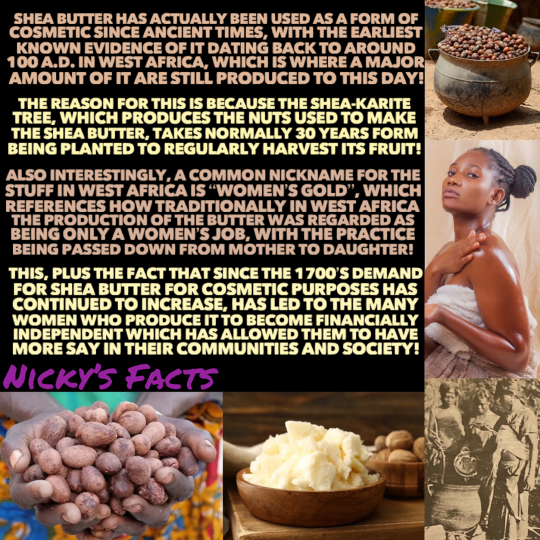

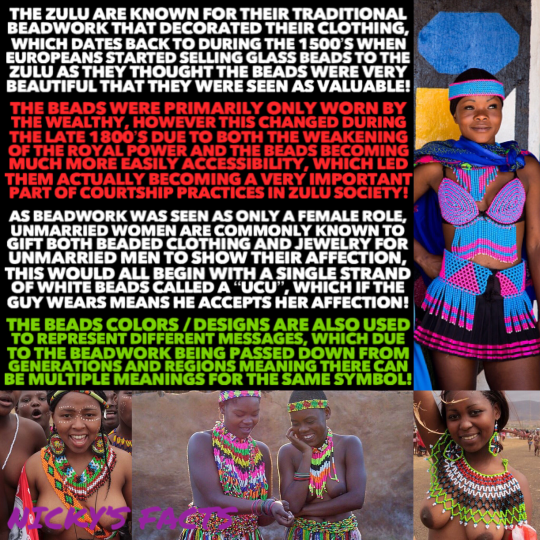

Here is a collection of precolonial African women’s history facts that showcase the many unique and interesting ways women have participated in African history prier to the 1600’s, which sadly I find gets overlooked by more modern history!

🤎💜🤎

👩🏾🦱🌍🧑🏾🦱

💜🤎💜

#black history month#african women#black history#precolonial africa#black femininity#soft black women#traditional femininity#black tumblr#soft black girls#womens history#african culture#black girl moodboard#black girls of tumblr#african history#girl blogger#black girl magic#soft black girl#girl power#nickys facts

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

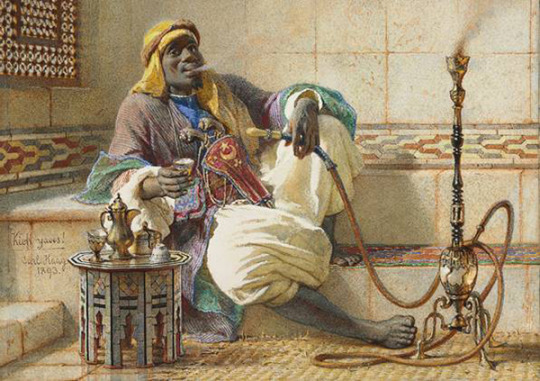

On cannabis in colonial Africa

#cannabis

Jah Billah says: This article delineates pre-colonial and colonial use of cannabis in Africa. Starting with prehistoric cultivation 1300 BC in Ancient Egypt, and 2000 years ago in Madagascar. Going over North African and Sub-Saharan cannabis cultures, we learn that cannabis use was associated with coffee and that in Ethiopian language plant was once called esha tenbit “prophecy plant”.…

View On WordPress

#1300BC#2017#cannabis#Cannabis and Tobacco in Precolonial and Colonial Africa#Cannabis Commerce and Legality#Chris S. Duvall#COLONIALISM#EGYPT#esha tenbit#hemp#Madagascar

0 notes

Text

Organizing more notes. Some recent-ish books on German colonialism and imperial imaginaries of space/place, especially in Africa:

----

German Colonialism in Africa and its Legacies: Architecture, Art, Urbanism, and Visual Culture (Edited by Itohan Osayimwese, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023)

An Imperial Homeland: Forging German Identity in Southwest Africa (Adam A. Blackler, Penn State University Press, 2023)

Coconut Colonialism: Workers and the Globalization of Samoa (Holger Droessler, Harvard University Press, 2022)

Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884-1905 (Matthew Unangst, University of Toronto Press, 2022)

The Play World: Toys, Texts, and the Transatlantic German Childhood (Patricia Anne Simpson, 2020)

Learning Empire: Globalization and the German Quest for World Status, 1875-1919 (Erik Grimmer-Solem, Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Violence as Usual: Policing and the Colonial State in German Southwest Africa (Marie A. Muschalek, 2019)

Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, the League of Nations, and Imperialism (Sean Andrew Wempe, 2019)

Rethinking Black German Studies: Approaches, Interventions and Histories (Edited by Tiffany Florvil and Vanessa Plumly, 2018)

German Colonial Wars and the Context of Military Violence (Susanne Kuss, translated by Andrew Smith, Harvard University Press, 2017)

Colonialism and Modern Architecture in Germany (Itohan Osayimwese, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017)

---

German Colonialism in a Global Age (Edited by Bradley Naranch and Geoff Eley, 2014) Including:

"Empire by Land or Sea? Germany's Imperial Imaginary, 1840-1945" (Geoff Eley)

"Science and Civilizing Missions: Germans and the Transnational Community of Tropical Medicine" (Deborah J. Neill)

"Ruling Africa: Science as Sovereignty in the German Colonial Empire and Its Aftermath" (Andrew Zimmerman)

"Mass-Marketing the Empire: Colonial Fantasies and Advertising Visions" (David Ciarlo)

---

German Colonialism and National Identity (Edited by Michael Perraudin and Jurgen Zimmerer, 2017). Including:

"Between Amnesia and Denial: Colonialism and German National Identity" (Perraudin and Zimmerer)

"Exotic Education: Writing Empire for German Boys and Girls, 1884-1914" (Jeffrey Bowersox)

"Beyond Empire: German Women in Africa, 1919-1933" (Britta Schilling)

---

Advertising Empire: Race and Visual Culture in Imperial Germany (David Ciarlo, Harvard University Press, 2011)

The German Forest: Nature, Identity, and the Contestation of a National Symbol, 1871-1914 (Jeffrey K. Wilson, University of Toronto Press, 2012)

The Devil's Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa (George Steinmetz, 2007)

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

As used, the term ‘precolonial’ Africa and the distortions it represents cannot illuminate our understanding of Africa and its history.

More importantly, it is wrong to think of colonialism as a non-African phenomenon that was only brought in from elsewhere and imposed on the continent. Africa has given rise to a rich tapestry of diverse colonialisms originating in different parts of the continent. How are we to understand them? For example, if ‘precolonial Morocco’ refers to the time before France colonised Morocco, it must deny that the 800-year Moorish colonisation of the Iberian Peninsula, much of present-day France and much of North Africa was a colonialism. For, if it were, then ‘colonial Morocco’ must predate ‘precolonial Morocco’. I do not know how any of this helps us understand the history of Morocco. Similarly, a ‘precolonial’ Egypt that refers to Egypt before modern European imperialism would also deny Mohammed Ali’s colonial adventures at the head of Egypt in southern Europe and Asia Minor. Was ancient Egypt part of some precolonial formation? That strains credulity. To conceive of the history of Africa and Africans in terms only, or primarily, of their relation to modern European empires disappears the history of Africans as colonisers of realms beyond the continent’s land borders, especially in Europe and Asia.

It is bad enough that the term distorts the history of African states’ involvement in overseas provinces. It is worse that it misdescribes the evolution of different African polities over time. The deployment of ‘precolonial Africa’ is undergirded by a few implausible assumptions. We assume either that there were no previous forms of colonialism in the continent, or that they do not matter. We talk as if colonialism was brought to Africa by Europe, after the 1884-85 Berlin West Africa Conference. But it takes only a pause to discover that this is false.

African history is replete with accounts of empires and kingdoms. By their nature, empires incorporate elements of colonisation in them. If this be granted, Africa must have had its fair share of colonisers and colonialists in its history. When, according to the mythohistory (the founding myth of the empire) of Mali, Sundiata gathered different nations, cultures, political leaders and others to form the empire in the mid-13th century, he did not first seek the consent of his subjects. It was in the aftermath of their being subdued by his superior force that he did what Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century insisted all rulers should do if their rule is to escape repeated challenges and last for an appreciable length of time: turn might into right. Ethiopia, another veritable empire, is a multinational, multilingual, multicultural state whose members were not willing parties to their original incorporation into the polity. Whether you think of the Oromo or the Somali, many of their successor states within Ethiopia are, as I write this, still conducting anticolonial struggles against the Ethiopian state.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books by Black Authors for Black History Month!

I wanted to share a list of books I love and books that I'm looking forward to reading that are by Black authors in acknowledgement of Black History Month. I feel like a lot of my fellow readers (especially my fellow white readers) always go into a, kind of, reading slump in February and I don't know if that's because the month of January is just ten years long that February feels like a hangover or if it's because they feel the desire to read books by Black authors but then the majority of what is marketed is usually books that are steeped in trauma or nonfiction books. And, like, yeah, nonfiction books are so important but when they're the only kind of book marketed it can make finding the other kinds of books that much harder but I believe that if you read the fun books and the happy books and the fantasy books it will make you want to seek out the nonfiction resources. I'm blabbering so long story short, I thought I would make a little list to do some of the legwork for my fellow readers to find stories that they can check out.

I used GoodReads links (and one StoryGraph) link, you can choose who to purchase from yourself (although I will suggest BookShop.org as your purchase does go towards indie bookstores, I also really like the Libby App which is just your library and it works with your Kindle/Nook/Kobo/iPad). All authors that I have included in this are American or have strong ties to the USA which is why I did not include authors such as Bolu Babalola, Talia Hibbert, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie but I do highly recommend checking them out if you haven't because they do write gorgeously.

Kennedy Ryan has an extensive backlog and beautiful writing, beautiful prose. She had a book called Before I Let Go (Skyland #1) come out in November 2022, it is a second chance romance between a married couple. It has been on my shelf forever, the cover is beautiful and I've heard nothing but truthfully incredible things. I have listened to snippets of the audiobook but keep putting off getting the actual audiobook because Kennedy is the kind of author I want to read the grammar, syntax, wording of everything from. This book actually got optioned to be adapted into a television show and there's a second Skyland book coming out in March called This Could Be Us that has the ARC readers going wild.

Jasmine Guillory is one of my favorite authors. She is a Bay Area native and has a law degree from Stanford. Not only do I think that she writes beautifully but I cannot even describe to you the way that I kick my little feet and twirl my hair. I feel like my favorite of hers changes. Up until a few weeks ago, I would've told you that Olivia Monroe in Party of Two was my favorite Jasmine girly but I listened to Royal Holiday to kick off my reading for January and Vivian Forest is such a beautiful character. She's a 56 year old Black woman who is a veteran social worker who thinks it's too late for her on several fronts and then she gets swept off her feet while on a vacation with her daughter AND THE ROYAL FAMILY. What?! I also think that Jasmine writes, like.... character appropriate sex scenes if that makes sense. Like, Vivian's scenes are more reserved than Olivia's were, Vivian's more closed door than Olivia's were. She also has a Beauty and the Beast inspired book called By The Book and I kept texting my friend the entire way through and then made her buy a copy so she could text me right back with all her thoughts. Amazing. I love her.

You want cozy fantasy romance with monsters and happy Black women being loved by their hot monster lovers? Kimberly Lemming has GOT YOU COVERED.

Plugging my new author friend P.J. Leigh and her book Olawu. She actually responded to my request for some indie author recs on Threads and sent me a copy of Olawu that will be here on Friday and I'm so excited. She describes it as: "Set in precolonial East Africa with romance, action, sisterhood, found family, and a feisty but flawed female lead." I cannot wait to dig into this one.

Another author who messaged me is indie author Quiana Glide. Her bio is that she is an unabashed fangirl and her books feature pregnancy trope, cosplay, professional wrestlers and cafe owners solving murders. Her books sound fucking great and they are available on Kindle Unlimited for my KU girlies (gender neutral).

Celestine Martin messaged me as well and she writes paranormal romance with Black witches, emo mermen and fae princes. I tripped over myself running to my Libby app to place a hold on the audiobook.

25 to Love! by Joye Johnson is another one available on Kindle Unlimited for my KU girlies (gender neutral). The synopsis is: "TV's hottest dating show is '25 to Love!'. To nab a guy from her past, Lola signs on as the token girl of color. All's fair in love and ratings--can a week on TV get Lola closer to the one that got away?" You know what I love? Second chance romances, besties, that's right.

Splinter by Jasper Hyde was another I was recommended. Jasper writes paranormal, LGBTQ+ books. Jasper Hyde is a pen name for Georgina Kiersten who also goes by Rian Fox. The pen name denotes the subgenre that they write. Georgina does go by they/them pronouns and writes plus sized rep and neurodivergent rep too.

Kelly Cain. That's it. That's the tweet. THE EVERHEART BROTHERS SERIES????? If you know anything about me, you know that I have a hearing issue and so I've used audiobooks before but I never really clicked with them or got the hype. Turns out I had boring ass narrators (look I did the audio version of a lot of nonfiction books I had to read about old dead white guys in college so of course I had that feeling). THE EVERHEART BROTHERS AUDIOBOOKS ARE WHAT CHANGED ME. Deanna Anthony, the narrator, is so engaging and I didn't feel like I was listening to an audiobook, I felt like I was sitting across the table at brunch having a gossip session with my bestie. If you read it and you didn't like it, that's fine, but I didn't lie to you and enjoyment of art is subjective but also you're wrong and argue with a wall.

I've been seeing a lot of talk lately about Pride & Protest by Nikki Payne. This is a Pride & Prejudice and one of the reviews says, "If you ever wanted P&P to feel more like watching a swoony, steamy episode of Insecure, this is the book for you."

Currently, I am reading You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty by Akwaeke Emezi. It deals with themes of grief and romance and also bisexual representation. Absolutely beautiful prose. Akwaeke is Nigerian and has been in the USA since college. They are non-binary and go by they/them pronouns.

I also cannot end this list without mentioning Memphis by Tara M. Stringfellow. This follows three generations of a southern Black family in the neighborhood of Douglass in Memphis, TN (I was born a couple miles away in Raleigh) . Now, this book does have quite a few trigger warnings that I won't put here but I do encourage you to READ THE TRIGGER WARNINGS before you purchase this book as it does deal with some pretty heavy subject matter.

I'm also going to end this by saying to keep an eye out for anything done by my best friend, the person who I have shared so many amazing, beautiful, life changing experiences with ALL OVER THE WORLD for the last fourteen years: Isana Skeete (Isana does not use pronouns). If you look at the GoodReads account for Isana that I linked, you'll see lists made with recommendations of books with queer POC rep and asexuality representation.

#long post#black authors#book recs#book club#booklr#kennedy ryan#jasmine guillory#kelly cain#kimberly lemming#tara m. stringfellow#akwaeke emezi#nikki payne#georgina kiersten#jasper hyde#pj leigh#joye johnson#celestine martin#romance books#paranormal romance#contemporary romance#i'm posting this now and then will rebagel in the morning

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remy ma is a member of the Hausa people

The Hausa (autonyms for singular: Bahaushe (m), Bahaushiya (f); plural: Hausawa and general: Hausa; exonyms: Ausa; Ajami: مُوْتَانَنْ هَوْسَ) are the largest ethnic group in West and Central Africa. They speak the Hausa language, which is the second most spoken language after Arabic in the Afro-Asiatic language family. The Hausa are a diverse but culturally homogeneous people based primarily in the Sahelian and the sparse savanna areas of southern Niger and northern Nigeria respectively, numbering around 54 million people with significant indigenized populations in Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Chad, Sudan, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Togo, Ghana, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Senegal and the Gambia.

Predominantly Hausa-speaking communities are scattered throughout West Africa and on the traditional Hajj route north and east traversing the Sahara, with an especially large population in and around the town of Agadez. Other Hausa have also moved to large coastal cities in the region such as Lagos, Port Harcourt, Accra, Abidjan, Banjul and Cotonou as well as to parts of North Africa such as Libya over the course of the last 500 years. The Hausa traditionally live in small villages as well as in precolonial towns and cities where they grow crops, raise livestock including cattle as well as engage in trade, both local and long distance across Africa. They speak the Hausa language, an Afro-Asiatic language of the Chadic group. The Hausa aristocracy had historically developed an equestrian based culture. Still a status symbol of the traditional nobility in Hausa society, the horse still features in the Eid day celebrations, known as Ranar Sallah (in English: the Day of the Prayer). Daura city is the cultural center of the Hausa people. The town predates all the other major Hausa towns in tradition and culture.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#afrakans#africans#fitness#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#afrakan woman#tupac#kemet#deep reddish brown skin#epic video#africa#african spirituality#hausa#remy ma#Nigerian

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ashantis have the largest population in Ghana 🇬🇭 with a population estimated at 12 million people, and they can be found in Ghana, Togo 🇹🇬 and Ivory Coast 🇨🇮

The Ashanti people, who are a subgroup of the Akan, speak the Twi language, a language that is one of the most widely spoken in West Africa. Their capital was Kumasi, one of the largest cities in Ghana. Kumasi was the capital of the Ashanti precolonial federation, also sometimes referred to as a kingdom.

Most modern Ashanti people are Christians. Some are traditional worshippers, while a growing population of Muslims can also be found.

According to the history of these great people, the Ashanti kingdom was found in the 1600s, in the midst of a land that was full of gold and that served as a major trade item between them and the Europeans.

Many descendants Ashantis exist in Caribbean countries, especially in Jamaica, where there is a clear Ashanti influence in the Jamaican name, dress, and physical appearance.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 3. Economy

What about building and organizing large, spread-out infrastructure?

Many Western history books assert that centralized government arose out of the need to build and maintain large infrastructure projects, especially irrigation. However, this assertion is based on the assumption that societies need to grow, and that they cannot choose to limit their scale to avoid centralization — an assumption that has been discredited many times over. And while large-scale irrigation projects do require some amount of coordination, centralization is only one form of coordination.

In India and East Africa, local societies built massive irrigation networks that were managed without government or centralization. In the Taita Hills region of what is now Kenya, people created complex irrigation systems that lasted hundreds of years, often until colonial agricultural practices ended them. Households shared day-to-day maintenance, each responsible for the closest section of the irrigation infrastructure, which was common property. Another custom brought people together periodically for major repairs: known as “harambee labor,” it was a form of collective, socially motivated work, similar to traditions in many other decentralized societies. The people of the Taita Hills ensured fair use through a number of social arrangements passed on by tradition, which determined how much water each household could take; those who violated these practices faced sanctions from the rest of the community.

When the British colonized the region, they assumed they knew better than the locals and set up a new irrigation system — geared, of course, to cash crop production — based on their engineering expertise and mechanical power. During the drought of the 1960s, the British system failed spectacularly and many locals returned to the indigenous irrigation system to feed themselves. According to one ethnologist, “East African irrigation works seem to have been more extensive and better managed during the precolonial era.”[48]

During the Spanish Civil War, workers in occupied factories coordinated an entire wartime economy. Anarchist organizations that had been instrumental in bringing about the revolution, namely the CNT labor union, often provided the foundations for the new society. Especially in the industrial city of Barcelona, the CNT lent the structure for running a worker-controlled economy — a task for which it had been preparing years in advance. Each factory organized itself with its own chosen technical and administrative workers; factories in the same industry in every locality organized into the Local Federation of their particular industry; all the Local Federations of a locality organized themselves into a Local Economic Council “in which all the centers of production and services were represented”; and the local Federations and Councils organized into parallel National Federations of Industry and National Economic Federations.[49]

The Barcelona congress of all Catalan collectives, on August 28, 1937, provides an example of their coordinating activities and decisions. The collectivized shoe factories needed 2 million pesetas credit. Because of a shortage of leather, they had to cut down on hours, though they still paid all their workers full time salaries. The Economic Council studied the situation, and reported that there was no surplus of shoes. The congress agreed to grant credit to purchase leather and to modernize the factories in order to lower the prices of the shoes. Later, the Economic Council outlined plans to build an aluminum factory, which was necessary for the war effort. They had located available materials, secured the cooperation of chemists, engineers, and technicians, and decided to raise the money through the collectives. The congress also decided to mitigate urban unemployment by working out a plan with agricultural workers to bring new areas into cultivation with the help of unemployed workers from the cities.

In Valencia, the CNT organized the orange industry, with 270 committees in different towns and villages for growing, purchasing, packing, and exporting; in the process, they got rid of several thousand middlemen. In Laredo, the fishing industry was collectivized — workers expropriated the ships, cut out the middlemen who took all the profit, and used those profits to improve the ships and other equipment or to pay themselves. Catalunya’s textile industry employed 250,000 workers in scores of factories. During collectivization, they got rid of high-paid directors, increased their wages by 15%, reduced their hours from 60 to 40 hours per week, bought new machinery, and elected management committees.

In Catalunya, libertarian workers showed impressive results in maintaining the complex infrastructure of the industrial society they had taken over. The workers who had always been responsible for these jobs proved themselves capable of carrying on and even improving their work in the absence of bosses. “Without waiting for orders from anyone, the workers restored normal telephone service within three days [after heavy street fighting ended]... Once this crucial emergency work was finished a general membership meeting of telephone workers decided to collectivize the telephone system.”[50] The workers voted to raise the salaries of the lowest paid members. The gas, water, and electricity services were also collectivized. The collective managing water lowered rates by 50% and was still able to contribute large amounts of money to the anti-fascist militia committee. The railway workers collectivized the railroads, and where technicians in the railroads had fled, experienced workers were chosen as replacements. The replacements proved adequate despite their lack of formal schooling, because they had learned through the experience of working together with the technicians to maintain the lines.

Municipal transportation workers in Barcelona — 6,500 out of 7,000 of whom were members of the CNT — saved considerable money by kicking out the overpaid directors and other unnecessary managers. They then reduced their hours to 40 per week, raised their wages between 60% (for the lowest income bracket) and 10% (for the highest income bracket), and helped out the entire population by lowering fares and giving free rides to schoolchildren and wounded militia members. They repaired damaged equipment and streets, cleared barricades, got the transportation system running again just five days after fighting ceased in Barcelona, and deployed a fleet of 700 trolleys — up from the 600 on the streets before the revolution — repainted red and black. As for their organization:

the various trades coordinated and organized their work into one industrial union of all the transport workers. Each section was administered by an engineer designated by the union and a worker delegated by the general membership. The delegations of the various sections coordinated operations in a given area. While the sections met separately to conduct their own specific operations, decisions affecting the workers in general were made at general membership meetings.

The engineers and technicians, rather than comprising an elite group, were integrated with the manual workers. “The engineer, for example, could not undertake an important project without consulting the other workers, not only because responsibilities were to be shared but also because in practical problems the manual workers acquired practical experience which technicians often lacked.” Public transportation in Barcelona achieved greater self-sufficiency too: before the revolution, 2% of maintenance supplies were made by the private company, and the rest had to be purchased or imported. Within a year after socialization, 98% of repair supplies were made in socialized shops. “The union also provided free medical services, including clinics and home nursing care, for the workers and their families.”[51]

For better or worse, the Spanish revolutionaries also experimented with Peasant Banks, Labor Banks, and Councils of Credit and Exchange. The Levant Federation of Peasant Collectives started a bank organized by the Bank Workers Union to help farmers draw from a broad pool of social resources needed for certain infrastructure- or resource-intensive types of farming. The Central Labor Bank of Barcelona moved credit from more prosperous collectives to socially useful collectives in need. Cash transactions were kept to a minimum, and credit was transferred as credit. The Labor Bank also arranged foreign exchange, and importation and purchase of raw materials. Where possible, payment was made in commodities, not in cash. The bank was not a for-profit enterprise; it charged only 1% interest to defray expenses. Diego Abad de Santillan, the anarchist economist, said in 1936: “Credit will be a social function and not a private speculation or usury... Credit will be based on the economic possibilities of society and not on interests or profit... The Council of Credit and Exchange will be like a thermometer of the products and needs of the country.”[52] In this experiment, money functioned as a symbol of social support and not as a symbol of ownership — it signified resources being transferred between unions of producers rather than investments by speculators. Within a complex industrial economy such banks make exchange and production more efficient, though they also present the risk of centralization or the reemergence of capital as a social force. Furthermore, efficient production and exchange as a value should be viewed with suspicion, at the least, by people interested in liberation.

There are a number of methods that could prevent institutions such as labor banks from facilitating the return of capitalism, though unfortunately the onslaught of totalitarianism from both the fascists and Communists deprived Spanish anarchists of the chance to develop them. These might include rotating and mixing tasks to prevent the emergence of a new managing class, developing fragmented structures that cannot be controlled at a central or national level, promoting as much decentralization and simplicity as possible, and maintaining a firm tradition that common resources and instruments of social wealth are never for sale.

But as long as money is a central fact of human existence, myriad human activities are reduced to quantitative values and value can be massed as power, and thus alienated from the activity that created it: in other words, it can become capital. Naturally anarchists do not agree on how to strike a balance between practicality and perfection, or how deep to cut in order to root out capitalism, but studying all the possibilities, including those that might be doomed to failure or worse, can only help.

#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#anarchy works

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

i keep having this thought about history, about wanting to learn history, where i feel like...an anthropological interest, in reading about the precolonial societies of the americas, but its knowledge that doesnt give the satisfying effect of understanding the world a little better, because the nature of colonialism wiped away the significance of all that history yknow? or like, it didnt wipe it away of course, its still in the causal past, but it scrambled it

okay so like. one thing is if youre me, it seems kind of spooky that writing lets us know specific information about the past that we couldnt know any other way, that nobody not even a superintelligence, aliens, whatever could know. writing is special in that its like...a noise-resistant signature. every event leaves a causal signature, reverse the arrow of time (and charge and parity) and you get the past back, the past is inherent in the present. BUT its extremely noise sensitive, so up to our resolution we literally cant know certain details about the past, its mathematically impossible. but writing is noise resistant! that something was written down tells us a real fact about the past ("someone wrote this down") from which we can extrapolate other facts about the past

and culture, human history, etc, is kind of similar, in that we can learn facts about the past and then see how it affected our future, we can see how our history is in part determined by the way such and such a battle went in 100 BC or whatever. the connection is clear both ways. and the thing about colonialism is, it scrambled that influence. if mesoamerican history had gone different in some relatively minor way, if some other group had been the hegemon in mexico, im sure the modern world would be different, probably significantly so, but it wouldnt be *legibly* different, itd be different in a way very much life if you added a bunch of random noise to our world, yknow? does that make sense? so learning precolonial history doesnt give us idk, a much better model of the chain of causality underlying history. this is also partially true in like, subsaharan africa but less so of course. but i think it also kind of holds there. colonialism scrambled things. generally not true in asia imo, colonalism seems to have wiped things a lot less, used preexisting divisions a lot more, etc. it helps that theres a restrictive geography in most of asia thats less present in africa

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

So like do people who look down on precolonial (Subsaharan) African architecture not understand that you’re limited by how good your stone is? Just like how yeah, Kyiv at the time the Mongols sacked it, by no means the gleaming City of Tomorrow even by 13th century standards, had three times the population of Timbuktu or Great Zembabwe at their heights—but there is a reason Ukraine grew grain for all of the Soviet Union and a big chunk of the rest of of the Warsaw Pact, and almost all African cultures were primarily pastoralists instead of farmers. Most of Africa is a hard place to live.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The traditional origins of twerking!🍑

🎶🇨🇮🎶

#history#mapouka#dance#côte d’ivoire#music#african history#dabou#fertility#traditional femininity#1990s#twerking#just girly things#black coquette#black girl magic#african women#dance history#west africa#rap#precolonial#traditional practices#black femininity#coquette#womens history#zouglou music#african culture#nickys facts

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 READING LOG

JANUARY

-> Books:

HURSTON, Zora Neale; Their Eyes Were Watching God

WILLIAMS, Tennessee; A Streetcar Named Desire

-> Essays & articles:

CHRISTENSEN, Joel; How do chatbots dream of electric Greek heroes?

DYHOUSE, Carol; Why Are We So Afraid of Female Desire?

EDWARDS, Stassa; A Little Madly: Hysteria at the Moulin Rouge

HOOKS, bell; Romance: Sweet Love

LAING, Olivia; NYC blue: what the pain of loneliness tells us

LIEBERMAN, Jeffrey A.; “The Miracle Cure”: A Brief History of Lobotomies

LORDE, Audre; The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power

SHUSHAN, Gregory; Near-death experiences have long inspired after life beliefs

STADONILK, Joe; We’ve always been distracted

TÁÌWÒ, Olúfémi; The idea of ‘precolonial Africa’ is vacuous and wrong

WYPIJEWSKI, JoAnn; How Capitalism Created Sexual Dysfunction

FEBRUARY

-> Books:

DOUGLASS, Frederick; Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass

WINTERSON, Jeanette; 12 Bytes: How We Got Here, Where We Might Go Next

-> Essays & articles:

BLACK, Bob; The Abolition of Work

BURDEN-STELLY, Charisse; How Black Communist Women Remade Class Struggle

COBB, Michael; Bigmouth Strikes Again

GOODLAD, Lauren M.E.; Now The Humanities Can Disrupt “AI”

HALBERSTAM, Jack; Towards a Trans* Feminism

HARVEY, Katherine; Medieval babycare

ROTHFIELD, Becca; A Body of One’s Own

RUKES, Frederic; The Disruption of Normativity: Queer Desire and Negativity in Morrisey and The Smiths

STRINGER, Julian; The Smiths: Repressed (But Remarkably Dressed)

VENKATARAMAN, Vivek V.; Lessons from the foragers

MARCH

-> Books:

AMADO, Jorge; Gabriela, Clove & Cinnamon

-> Essays & articles:

ALEXANDER, Amanda; Making Communities Safe, Without the Police

BOURDÉ, Guy; The philosophies of history

ELLIOTT, John H.; An Europe of composite monarchies

ERNAUX, Annie; A Community of Desires

HARCOUT, Bernard E.; Policing Disorder

JABBARI, Alexander; After the mother tongues: what we lost with Persianate modernity

MANTEL, Hilary; Anne Boleyn: witch, bitch, temptress, feminist

MANTEL, Hilary; Holy disorders

MANTEL, Hilary; Night visions

MANTEL, Hilary; No passport required

MANTEL, Hilary; The shape we’re in

MINER, Horace; Body Ritual among the Nacirema

RUSSEL, Francey; What It Means to Watch

WEBB, Claire Isabel; Cosmic vision

APRIL

-> Books:

MISHIMA, Yukio; Sun and Steel

OLADE, Yves; Bloodsport

-> Essays & articles:

BATESON, Gregory; A Theory of Play and Fantasy

CÉSAIRE, Suzanne; The Great Camouflage

CHARALAMBOUS, Demetrio; The Enigma of the Isle of Gold

DAVID, Kathryn; How Stalin enlisted the Orthodox Church to help control Ukraine

SINGLER, Beth; Existential Hope and Existential Despair in AI Apocalypticism and Transhumanism

WYATT, Justin; The Smiths, Pop Culture Referencing and Marginalized Stardom

-> Short stories:

ELLISON, Harlan; The Man Who Rowed Christopher Colombus Ashore

SAYLOR, Steven; The Eagle and the Rabbit

MAY

-> Books:

PLUTARCH; Life of Sulla

-> Essays & articles:

BRAUDEL, Fernand; Clothes and fashion

CHAMPLIN, Edward; Nero Reconsidered

GARTON, Charles; Sulla and the Theatre

HAY, Mark; The Colonization of the Ayahuasca Experience

HSU, Hua; Varieties of Ether: Toward a history of creativity and beef

PROBYN, Elspeth; Cannibal Hunger, Restraint in Excess

STAR, Christopher; How the ancient philosophers imagined the end of the world

TELUSHKIN, Shira; Meet Eva Frank: The First Jewish Female Messiah

#reading log#articles#essays#reading recommendations#reading recs#feminism#psychiatry#leftism#communism#anarchism#race#nationalism#imperialism#anthropology#anti-work#the smiths#tech#ai#ecology#religion#occult#bob black#thomas sankara#hilary mantel#audre lorde#bell hooks#annie ernaux

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just in case, some might enjoy. Had to organize some notes.

These are just some of the newer texts that had been promoted in the past few years at the online home of the American Association of Geographers. At: [https://www.aag.org/new-books-for-geographers/]

Tried to narrow down selections to focus on critical/radical geography; Indigenous, Black, anticolonial, oceanic/archipelagic, carceral, abolition, Latin American geographies; futures and place-making; colonial and imperial imaginaries; emotional ecologies and environmental perception; confinement, escape, mobility; housing/homelessness; literary and musical ecologies.

---

New stuff, early 2024:

A Caribbean Poetics of Spirit (Hannah Regis, University of the West Indies Press, 2024)

Constructing Worlds Otherwise: Societies in Movement and Anticolonial Paths in Latin America (Raúl Zibechi and translator George Ygarza Quispe, AK Press, 2024)

Fluid Geographies: Water, Science, and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, University of Chicago Press, 2024)

Hydrofeminist Thinking With Oceans: Political and Scholarly Possibilities (Tarara Shefer, Vivienne Bozalek, and Nike Romano, Routledge, 2024)

Making the Literary-Geographical World of Sherlock Holmes: The Game Is Afoot (David McLaughlin, University of Chicago Press, 2025)

Mapping Middle-earth: Environmental and Political Narratives in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Cartographies (Anahit Behrooz, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024)

Midlife Geographies: Changing Lifecourses across Generations, Spaces and Time (Aija Lulle, Bristol University Press, 2024)

Society Despite the State: Reimagining Geographies of Order (Anthony Ince and Geronimo Barrera de la Torre, Pluto Press, 2024)

---

New stuff, 2023:

The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Camilla Hawthorne and Jovan Scott Lewis, Duke University Press, 2023)

Activist Feminist Geographies (Edited by Kate Boyer, Latoya Eaves and Jennifer Fluri, Bristol University Press, 2023)

The Silences of Dispossession: Agrarian Change and Indigenous Politics in Argentina (Mercedes Biocca, Pluto Press, 2023)

The Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Dueterte (Vicente L. Rafael, Duke University Press, 2022)

Ottoman Passports: Security and Geographic Mobility, 1876-1908 (İlkay Yılmaz, Syracuse University Press, 2023)

The Practice of Collective Escape (Helen Traill, Bristol University Press, 2023)

Maps of Sorrow: Migration and Music in the Construction of Precolonial AfroAsia (Sumangala Damodaran and Ari Sitas, Columbia University Press, 2023)

---

New stuff, late 2022:

B.H. Roberts, Moral Geography, and the Making of a Modern Racist (Clyde R. Forsberg, Jr.and Phillip Gordon Mackintosh, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022)

Environing Empire: Nature, Infrastructure and the Making of German Southwest Africa (Martin Kalb, Berghahn Books, 2022)

Sentient Ecologies: Xenophobic Imaginaries of Landscape (Edited by Alexandra Coțofană and Hikmet Kuran, Berghahn Books 2022)

Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884–1905 (Matthew Unangst, University of Toronto Press, 2022)

The Geographies of African American Short Fiction (Kenton Rambsy, University of Mississippi Press, 2022)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski, University of Chicago Press, 2022)

Punishing Places: The Geography of Mass Imprisonment (Jessica T. Simes, University of California Press, 2021)

---

New stuff, early 2022:

Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-fatness as Anti-Blackness (Da’Shaun Harrison, 2021)

Coercive Geographies: Historicizing Mobility, Labor and Confinement (Edited by Johan Heinsen, Martin Bak Jørgensen, and Martin Ottovay Jørgensen, Haymarket Books, 2021)

Confederate Exodus: Social and Environmental Forces in the Migration of U.S. Southerners to Brazil (Alan Marcus, University of Nebraska Press, 2021)

Decolonial Feminisms, Power and Place (Palgrave, 2021)

Krakow: An Ecobiography (Edited by Adam Izdebski & Rafał Szmytka, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021)

Open Hand, Closed Fist: Practices of Undocumented Organizing in a Hostile State (Kathryn Abrams, University of California Press, 2022)

Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

---

New stuff, 2020 and 2021:

Mapping the Amazon: Literary Geography after the Rubber Boom (Amanda Smith, Liverpool University Press, 2021)

Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by María del Pilar Blanco and Joanna Page, 2020)

Reconstructing public housing: Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives (Matt Thompson, University of Liverpool Press, 2020)

The (Un)governable City: Productive Failure in the Making of Colonial Delhi, 1858–1911 (Raghav Kishore, 2020)

Multispecies Households in the Saian Mountains: Ecology at the Russia-Mongolia Border (Edited by Alex Oehler and Anna Varfolomeeva, 2020)

Urban Mountain Beings: History, Indigeneity, and Geographies of Time in Quito, Ecuador (Kathleen S. Fine-Dare, 2019)

City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856 (Marcus P. Nevius, University of Georgia Press, 2020)

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This is the first book for nonspecialists to explore the great precolonial kingdoms of Africa that have been marginalized throughout history. Great Kingdoms of Africa aims to decenter European colonialism and slavery as the major themes of African history and instead explore the kingdoms, dynasties, and city-states that have shaped cultures across the African continent."

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The wheel is overrated: Why precolonial Africa didn't use the wheel

2 notes

·

View notes