#proto-IMDB

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Roger Ebert is my husband.

Cinemania '95

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE RETURN! -- RETURN OF THE "TUMBLR COVER PHOTO" SERIES!

PIC(S) INFO: Part 1 of 2 -- Spotlight on the first set in my ongoing series of Tumblr Cover Photos for the year 2024, and I've finally made up my mind that I will be continuing them, just not as fervently as I was last year. This set includes:

Rob Williams, blasting away as drummer for Weymouth, MA, hardcore punk/proto-blastcore band, SIEGE.

Variant head/helmet for Gentle Giant's 2011 San Diego Comic-Con exclusive "STAR WARS" Imperial Snowtrooper mini bust, after the legendary Ralph McQuarrie's unused concept art

The Lizard, Spidey supervillain, by Todd McFarlane, from "Amazing Spider-Man" Vol. 1 #313 (March 1989).

Japanese 2015 re-release movie poster for cult hip-hop/independent movie "Wild Style" (1983).

THE JIMI HENDRIX EXPERIENCE, as photographed by Karl Ferris for the U.S. release of 1967's "Are You Experienced."

Promotional image for Moribundi (action figure), from Clive Barker's "Tortured Souls" Series 2 by McFarlane Toys.

Partial poster art for the 1978 American sexploitation film "Hot Lunch."

Logo for Swedish hardcore/D-beat band TOTALITÄR

Sources: CVLT Nation, Vintage Posters (shop), McFarlane Toys, IMDb, Pinterest, X, Rebel Scum (blogspot), various, etc...

#Tumblr Cover Photos 2024#Cover Photos#Cover Photos 2024#Tumblr Cover Photos#TOTALITÄR#SIEGE band#STAR WARS#Imperial Snowtrooper#Ralph McQuarrie#Sexploitation Films#Super Seventies#THE JIMI HENDRIX EXPERIENCE 1967#Are You Experienced#Swedish D-beat#Proto-fastcore#Golden Age of hip-hop#Marvel Universe#Marvel Villains#Karl Ferris#80s hardcore#Hot Lunch 1978#Tortured Souls#WILD STYLE 1983#Concept Art#Psychedelia#Proto-blastcore#Original Trilogy#The Lizard#JIMI HENDRIX 1967#SIEGE

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched Sopranos 3x04 "Employee of the Month" last night and I was thinking about it all day today. I don't remember the last time a TV episode shook me this hard. I just finished writing eight (8) pages in my journal reflecting on it and now my arm is sore. Anyway here are some of the points that I wrote about way more verbosely in my journal:

I hate Dr. Melfi's ex-husband so fucking much holy shit I want to punch him in his stupid fucking victim-blaming face

I read some reviews of this episode on IMDb that made me mad because I felt that they were framing Melfi's choice as one between being a bad victim with punitive urges and being a good victim who takes the high road, BUT these reviews made me realize that the episode itself doesn't frame it that way, which I really like. Instead, it's about (1) not "break[ing] the social compact" that categorically disallows vigilante justice, and (2) not crossing the threshold into Tony's world that she could never uncross. She doesn't cross the threshold, but she's still allowed her anger.

I really wished Tony would have found out what happened, not because I would have like to see him avenge her (although tbh I would like that and I hope someone's written that fanfic), but just because I really wanted to see how he would react, how/whether it would affect his image of her, how/whether it would affect their relationship going forward. The two of them have one of the most interesting dynamics I've ever seen on TV, and it's only season 3!

I'm getting a vague sense of Meadow and Jackie Jr. as mirror images, but I won't say much about that because it could turn out that I'm totally reaching. We shall see.

Within this episode, Janice and Melfi were sort of mirror images, too, at least with respect to Tony.

EDIT: I wanted to explain that last point: what I meant was that Tony has to get involved in Janice's problem even though he really doesn't want to, whereas Dr. Melfi doesn't give him the chance to get involved in her problem, even though he might well have been willing to do so. But also, another anti-parallel between them occurred to me, this time nothing to do with Tony: Janice responds to a traumatic experience by declaring that she's now a Christian. Melfi responds to a much worse experience, and one that she, unlike Janice, did nothing to bring on, by sticking to her principles. Janice gives up responsibility for herself to God. Melfi remains in control of herself.

I loved the conversation between Tony and Christopher about Jackie Jr., especially when Christopher accuses Tony of thinking that Jackie Jr. is too good for the mob life but that he (Christopher) isn't. I can't remember him ever expressing anything like that before and I'm wondering whether it's a harbinger of things to come in their relationship. Again, we shall see!

At the party at the Sacks' house, there's a part where Tony exits the house onto the patio and walks past Christopher and Adriana making out against the wall. That made me laugh so hard oh my god. They're just going at it!

I had no clue that the ancient Romans had proto-Rottweilers! I assumed Rottweilers were invented by Germans. Neat!

#x#The Sopranos#Anna watches tv#Anna watches The Sopranos#the thing I hate about the new post editor is that it doesn't save the capitalization of past tags you've used#so if I want my tags to be properly capitalized (which I do) I have to write them out all over again. bleh.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why is it that wikipedia lists the cat from Naughty but Mice as a prototype sylvester? The only real similarity between the two, it seems, is being black and white cats—but so are a lot of cats in Looney Tunes, and cartoons in general??

i'm going to mimic the same spiel everyone and their dog has heard from their high school teachers: DO NOT TRUST WIKIPEDIA!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! < i'm purposefully being dramatic but animation misinformation is RAMPANT and i try to avoid wikis and Wikipedia as much as possible

YOU'RE RIGHT THOUGH, the cat in Naughty but Mice is just a regular cat. that's a common misconception, it seems every black and white cat whose appeared before 1945 is labeled as a prototype Sylvester which is VERY false. Sylvester has no prototype (unless you count his designs in Life with Feathers or Kitty Kornered, but that cat in both cartoons is Very Much Sylvester.)

a lot of it may come down to the prototype Elmer and Bugs, but they ARE actual prototypes of their respective counterparts. proto Elmer is explicitly named as such, and even the Arthur Q Bryan Elmer occasionally sports an outfit adjacent to the prototype; proto Bugs is also named after his creator, models name him as such, and in spite of all his differing designs, the voice and laugh give it away as the same rabbit if the appearance itself doesn't. people in animation fanbases have a tendency to get a little slap happy with spreading info (myself included) and said info has a tendency to get passed around a LOT. we're still trying to debunk the myth that proto-Bugs was named Happy Rabbit, or that proto-Fudd was named Egghead (who is his own character), and of course animation IDs are a war zone for misidentification (but i am absolutely no stranger to this trap as well and understand how easy it is to fall into said trap.) but yeah, wikis and imdb are good in a pinch but not always the most reliable sources!!

#SORRY FOR THE LACK OF POSTING ASKS i've been busy with work and am currently in 'i am symptomatic with The 'Rona but my tests are negative'#purgatory so i've been pretty fatigued#anonymous#asks

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts on that Space Ghost movie that died in pre-prod that basically just seemed like it was gonna be "GOTG but it's space ghost, brak, zorak and moltar having to team up to do space hero shit after decades of being failed talkshow hosts" with (iirc) Jon Hamm as Tad Ghostal himself and Reggie Watts doing a mocap cgi Zorak?

oh and it was gonna have a GOTC esque music gimmick as well, but with late 80s-early 90s proto alt rock like like, sonic youth and dinosaur jr, the minutemen and pavement

I have never heard of this and there is absolutely no record of it existing anywhere online. The only thing that comes up in a search for "Space Ghost Movie" is George Lowe in the costume at the Aqua Teen movie premiere.

youtube

In theory I feel like if there was ever a window for a Space Ghost movie, it would have been from around this time, but Reggie Watts wasn't doing tons of acting back then.

Anything more recent than that and I feel like it would have left a footprint on some movie news site at some point. Like imdb has a lot of entries for dead movies that never came to be.

I dunno. At this point, given Martin Croker died, I'm fine with letting the Space Ghost "brand" rest. I don't want to hear anyone else as Zorak or Moltar. That version of those characters do not exist without Martin Croker.

And I'm not particularly fond of the attempts made to respin Space Ghost back in to a serious super hero.

Just let it rest. It's fine that things sometimes end and ever come back.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

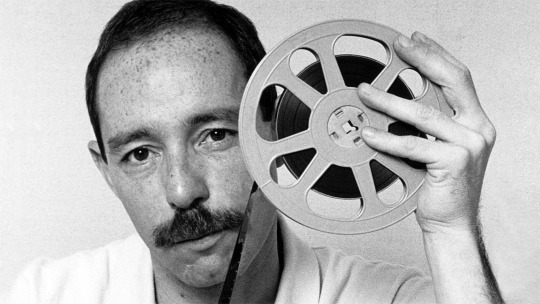

He Was Here.

On the anniversary of Vito Russo’s death from AIDS, filmmaker Jenni Olson remembers the activist and author, who helped so many—including Olson herself—crash out of the celluloid closet.

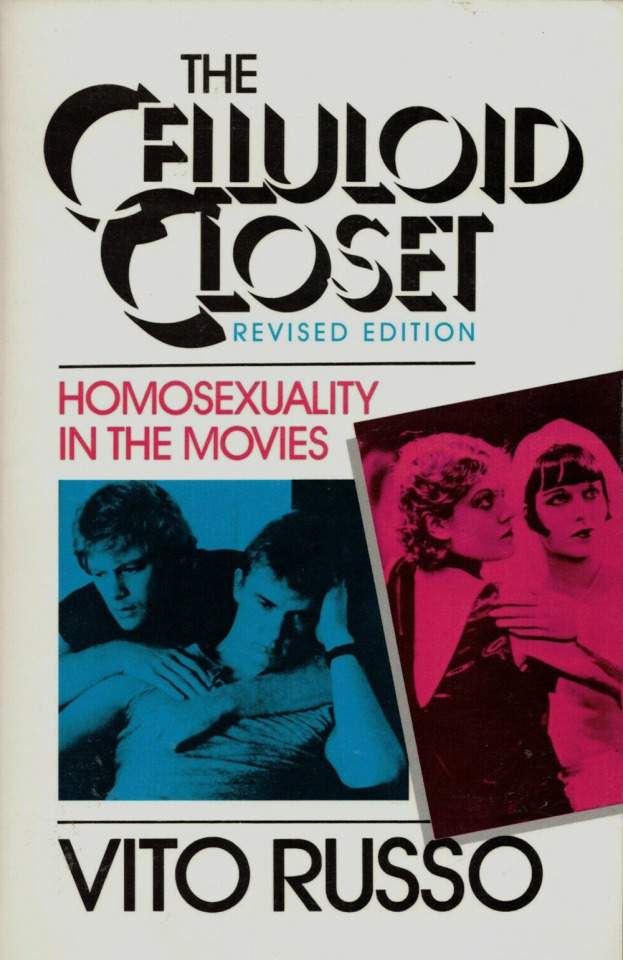

Back in 1986, when my film studies professor handed 23-year-old me a copy of Vito Russo’s book, The Celluloid Closet, little did I know how life-changing it would be. I would go so far as to say that Vito’s powerfully written analysis of the history of homosexuality in the movies actually saved my life.

First published in 1981, The Celluloid Closet covered the history of LGBTQ representation on screen since the dawn of motion pictures. Vito wrote about films as far back as Richard Oswald‘s 1919 Anders als die Anderen (Different from the Others), the German film considered to be the first gay feature, and Mädchen in Uniform, the beautiful and surprisingly political 1931 German drama considered to be the first lesbian feature.

Covering more than a hundred movies, the book spanned all the Hollywood stereotypes: the proto-gay sissies like Franklin Pangborn and Eric Blore in the 1930s; the creepy coded predatory lesbians of the 1940s and 1950s (like the prison matron in Caged); sensational trans depictions like I Want What I Want and The Christine Jorgensen Story, and half-lurid, half-comical bisexual tales such as A Different Story.

Vito revisited the book towards the end of the 1980s, incorporating some more recent achievements of the time, like the Academy Award winning documentary, The Times of Harvey Milk and beloved LGBTQ indie classics like Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts and Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances. (There is, naturally, at least one Letterboxd list of all the films in this revised edition.)

When The Celluloid Closet landed in my hands, I had been miserably stumbling along in college, and in life, for the previous five years. Vito’s book was the catalyst for my coming out to myself as queer (I wanted to see all those movies he wrote about) and for coming into the LGBTQ community (I imagined everyone else might want to see those movies too).

And so, despite having zero experience in how to do it, I started a weekly queer film series on campus, which brought hundreds of people out to the movies each Wednesday night. While there were certainly LGBTQ stories being told on screen in 1986, it was still an era where these films were much harder to access. Some were shown on television or available on VHS tape, but often these films had to be seen at film festivals or arthouse theaters.

The very first films I programmed in that series included some titles that remain among my favorite LGBTQ movies of all time: the aforementioned Mädchen in Uniform; the wonderfully romantic, 1968 French schoolgirl drama Therese & Isabelle; and jumping ahead to the indie gay films of the 1980s, Arthur J. Bressan’s devastating AIDS drama, Buddies (1985).

A few years later (with my University of Minnesota film studies BA in hand), I jumped in to become co-director of Frameline in San Francisco, the oldest and largest LGBTQ film festival in the world, and carved out a queer corner of the internet for movie lovers, co-founding the massive LGBTQ movie database, PopcornQ (aka “the gay IMDb”) as part of the world’s first major LGBTQ website, PlanetOut.

Along the way, I also worked as a queer-film critic, queer-film historian, queer-film collector, queer-archival researcher, queer-consulting producer (most recently on Sam Feder’s acclaimed overview of trans lives on screen, Disclosure), and spent a decade driving the marketing efforts of the oldest and largest LGBTQ film distributor in North America (Wolfe Video). And I made some films myself. (Yes, there is a Letterboxd list!)

At some point, Vito and I became friends. More than that, he became my mentor. He instilled in me a passionate belief in the power of LGBTQ cinema; in all the ways that films can give us the support and compassion, the inspiration and validation, the respect and dignity, the complexity and nuance, the joy and entertainment that we need and desire. And yes, even the messy and fucked-up representations, too. (Be gay, do crime, etc.)

Vito died of AIDS on November 7, 1990. As the 31st anniversary of his passing approaches, I’ve been thinking a lot about leadership, both personal and collective, and how we make positive change.

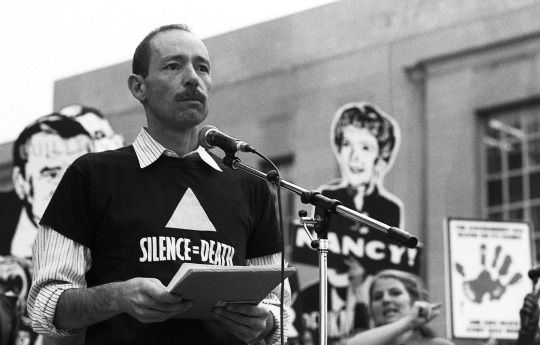

In addition to his groundbreaking work on that life-changing book, which was made into the tremendous, must-see 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, Vito had long been an important gay activist in New York City, eventually co-founding ACT UP in 1987.

Russo with Bette Midler at the 1973 Gay Pride Rally in Washington Square Park, New York.

Vito was also one of the founders of GLAAD, the US-based LGBTQ media advocacy organization dedicated to (among many other things) improving LGBTQ representation in film and television. Since 1985, GLAAD has had an enormous impact in transforming the on screen landscape with regard to LGBTQ characters and stories, cast and crew, coverage and visibility of queer cinema.

This year—this is such a beautiful and deeply moving thing for me—Vito’s mentorship came full circle. I now work for GLAAD. It is my actual job, every day of the week, to carry on his legacy.

As director of our Social Media Safety program, I advocate for LGBTQ user safety around content moderation, data privacy, problematic algorithms and other forms of tech and platform accountability (yes, including Letterboxd). I also get to be involved in some of GLAAD’s other media advocacy work.

One of the most impactful things that GLAAD produces each year is the Studio Responsibility Index, which evaluates each of the major Hollywood studios and serves as a road map toward increasing fair, accurate and inclusive LGBTQ representation in film. There’s an equivalent publication covering the television industry: the Where We Are On TV report.

GLAAD’s most public media advocacy work is the annual GLAAD Media Awards, honoring fair, accurate and inclusive representations of LGBTQ people and issues in film, television and other media. (Submissions are open until December 7, 2021—if you’ve made something, make sure we know about it.)

Every year the event honors Vito’s legacy with the presentation of the Vito Russo Award to an openly LGBTQ media professional who has made a significant difference in promoting equality for the LGBTQ community. Recent recipients include George Takei, Billy Porter, Samira Wiley and Ryan Murphy.

In an interview with Making Gay History author and podcast host Eric Marcus, Vito talked about the legacy he wanted to leave, citing Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar.

“He said, the thing is, is you can’t regret your life, otherwise why did you live? What was the point of having a life if you didn’t say something or do something that was gonna survive after you’re gone… I really feel the reason why I’m here is so that I could leave this book and these articles so that some sixteen-year-old kid who’s gonna be a gay activist in the next ten or fifteen years is gonna read them and carry the ball from there.”

I love the thought of how amazed Vito would be if he could see what LGBTQ representation on the big screen looks like today compared to where we were when GLAAD was founded 36 years ago—in large part because of his leadership.

Let me just shout out a few Letterboxd lists that so vividly illustrate this point: Intersex, LGBT POC, Films featuring LGBTQ characters/folks with disabilities, LGBT+ films from Southwest Asia and North Africa, TRANS, South Asian LGBT, Directed and/or written by transmascs and trans men, Todos Me Miran: The Queer Latinx Experience. And hey, if the movie list you want—or indeed the movie—doesn’t exist yet, may this be the inspiration that prompts you to create it.

Activist and author Vito Russo. / Photo by Rick Gerharter/HBO Documentary Films

You can learn more about Vito in Jeffrey Schwarz’s beautiful 2011 documentary, Vito. And, you could begin applying GLAAD’s Vito Russo Test to your movie-watching habits. Briefly: a film must include an identifiable LGBTQ character; who is not solely defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity; and, the character must matter to the plot. This short video on GLAAD’s YouTube channel explains it more—there are already many Vito Russo Test lists scattered across Letterboxd.

Lastly, follow GLAAD’s brand new Letterboxd HQ account, where you can discover some of the best LGBTQ films of the past few decades via our lists of GLAAD Media Award Winners. A quick name drop of a handful of those honorees over the years just to whet your appetite: The Wedding Banquet, Pariah, Go Fish, Brokeback Mountain, Moonlight, The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love, Call Me by Your Name.

Grazie, Vito!

Related content

World AIDS Day is December 1—Here’s a Letterboxd list of films that ensure we never forget.

Rebel Dykes, a documentary mash-up of animation, archive footage and interviews about a radical lesbian subculture in 1980s London, opens in UK and Irish cinemas from 26 November (US release TBA)

All the Good Boys: Schlockvalues’ essay for Letterboxd on the real roots of queer cinema and the evolution of gay masculinity on screen

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

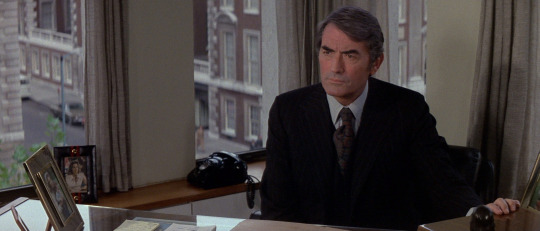

The Stalking Moon (1968)

By the late 1960s, the American Western’s zenith had passed, and the genre was reinventing itself. Bonnie and Clyde (1967) unleashed a wave of films in all genres depicting violence more openly and graphically; meanwhile, the rise of the Revisionist Western (1962’s Ride the High Country, 1966’s The Professionals) led to the deglamorization of the genre’s protagonists and their sense of morality. Released by National General Pictures (NGC), The Stalking Moon reunites producer Alan J. Pakula, director Robert Mulligan, and Gregory Peck – no longer a dashing young man – a six years after To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). Though the team is a throwback, the mindset of The Stalking Moon fits squarely within a Revisionist Western. Mulligan’s dialogue-light film incorporates elements of atmospheric thrillers and, in its tensest moments, seems to resemble a proto-slasher. As a hybrid thriller-Western, The Stalking Moon – once the narrative pieces are in place – is a sharp-edged, gorgeously-shot affair.

On Sam Varner’s (Peck) last day before retiring from the U.S. Cavalry, his regiment surrounds and arrests dozens of Apache warriors. Among the group is a white woman, Sarah Carver (Eva Marie Saint), and her half-Indian son (Noland Clay; Clay’s ethnicity/race is unclear). That afternoon, Sarah pleads for an immediate escort from the Cavalry’s camp instead of waiting for five days for an official military escort. The boy’s father, Salvaje (Nathaniel Narcisco in redface; Narcisco’s ethnicity/race is unclear), is a ruthless assassin and, according to Sarah, almost certainly in pursuit of their son. The Cavalry commander rejects Sarah’s request, but Sam agrees to take them to a remote train station. At the station, disaster strikes, and Sam invites Sarah and her son to stay with him at his rugged, mountainous ranch in New Mexico. Sarah and her son find the personal adjustments to live on Sam’s ranch difficult, but they have help thanks to ranch hands Ned (Russell Thorson) and Nick Tana (Robert Foster, whose character is a half-Indian scout). But even in this ranch, protected on three sides by treacherous rock formations, Sarah and her son have not yet eluded the violence to come.

Mulligan also appears to make comments on how the United States treated the American Indians of the West, but ultimately never does so. The Stalking Moon never highlights indigenous perspectives, declining to even give Sarah’s son a name or expressive space. These perspectives only exist through implication – the wars of the American West are going poorly for the tribes, and white settlers are moving ceaselessly westward and are cementing themselves in these lands. Sarah and Salvaje’s child, being of mixed race and approximately eight or nine years old, would almost certainly be the target of sociopolitical discrimination and the suspicious gazes of many a stranger. Never discussed by any of the characters is the possibility of such behavior towards the child; if Mulligan and screenwriters Wendell Mayes (1959’s Anatomy of a Murder, 1972’s The Poseidon Adventure) and Alvin Sargent (1977’s Julia, 2004’s Spider-Man 2) attempted to insert subtext regarding the child’s treatment, they do so far too subtly.

Salvaje himself is a largely faceless antagonist who never exchanges any dialogue, let alone a grunt, a cry of pain, a primal exclamation. Like numerous American Western movies too numerous to name, this is a reinforcement of stereotypical depictions of American Indians in Hollywood – anonymous, without specific bearing to the lead characters. Is he pursuing his son to reclaim him or the murder him? The movie never says. To Salvaje’s credit, he is a physical menace that could easily overtake an aging Sam Varner. More often than not during the Western’s heyday, indigenous Americans – whether individually or as part of a collective – would be all too easily slaughtered in a hail of protagonists’ gunfire or explosives (in part because of their antagonistic anonymity). Such developments would serve The Stalking Moon, which is partly a thriller, poorly. Thus, Salvaje is an aversion of the too-easily-killed Indian trope, but his complete lack of non-violent interaction with any character and empty characterization beyond his capacity for violence and vengeance uphold the trope of the anonymous indigenous menace. His physicality and obvious threat to the protagonists serve thriller genre; his nature as a blank slate killer is a legacy from American Western narrative traditions (and now largely a relic to that tradition’s contemporary practitioners).

Now in his 50s when he made The Stalking Moon, Gregory Peck – if only because of Hollywood’s obsession over age – was reaching a point in his career where opportunities for lead roles inevitably begin to decline (but not his influence, as Peck was currently serving as the President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). The Stalking Moon will, on paper, appear to be typical material for Peck. His Sam Varner, when no one else will tend to Sarah and her son’s safety, will take the initiative even though this decision, at best, is an inconvenience or, at worst, might cost him his life. As it is so often with Peck, his screen presence – assuredness of posture, the timbre of his voice, and calming persona – engineers a great performance. Even with a screenplay that avoids providing dialogue-driven details about his character’s life, Peck makes Sam Varner another entry in his long filmography of upstanding heroes.

The screenplay also consigns Eva Marie Saint to playing her character as a trauma survivor whose apprehension is pervasive. If one is seeking a role where Saint is able to display the fullest breadth of her acting range, The Stalking Moon is certainly not that movie. But for how the screenplay portrays her character, this is a capable performance from Saint alongside child star Noland Clay as the boy (this film remains Clay’s only screen credit).

Cinematographer Charles Lang (1947’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, 1959’s Some Like It Hot) and editor Aaron Stell (1958’s Touch of Evil, To Kill a Mockingbird) pay lip service to the Western genre with luxurious takes of the mountains and rock formations that mark their landscape photography. With on-location filming in Red Rock Canyon and Valley of Fire State Park in Nevada, the low-to-the-ground, slightly upward-angled camera shots suggest that Sarah and her son, while making Sam Varner’s ranch house their new home, have nowhere to escape to. Dry shrubs line this small, sloped canyon with somewhat steep angles that make even walking without ascending or descending hazardous. Yet Lang and Stell’s collaboration truly impresses during the action setpieces – most notably in a scene where Gregory Peck, in a darkened room, awaits the entrance of the man who has been hunting the people he has been protecting. Before the naming and identification of the slasher subgenre of horror film, The Stalking Moon – noting its selective cinematography and editing in its tensest moments – relies on numerous lighting and staging techniques that the likes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Friday the 13th (1980) would later adopt. Though shot and edited like a thriller, much of the film has scenes of people-watching: adults observing children, children observing adults, people noticing small behavioral details otherwise glossed over in a less patient movie. These moments of observation substitute for the dialogue and are as important as the most critical pieces of dialogue in the film.

youtube

An unconventional score from composer Fred Karlin (1970’s The Baby Maker, 1973’s Westworld) is a restrained effort, making use of a full orchestra but rarely employing the aural grandiosity that an orchestra is capable of. Repeated often throughout The Stalking Moon is the opening motif whistled in the main titles, with the sparse melodies – usually performed by the whistler or a limited number of woodwinds and/or brass – suggesting the vastness and emptiness of the American West, even in the days of westward expansion. Karlin’s music has an unsettling quality that permeates into The Stalking Moon’s most joyous scenes. When Sarah and her son arrive and Sam’s residence for the first time, the cue “Sarah’s New Home” opens with solo triangle before the entrance of a lone flute. The occasional dissonance from the triangle conflicts with the flute – a subliminal, harmonic message (in addition to the various string harmonics used throughout) that Sarah’s dangers have not passed. So often in modern film composing, a director will relegate the music as background noise or the composer themselves will dispense almost entirely of melody. In the latter, numerous modern film score composers have reasoned that melody cannot serve action films or thrillers, so they will compose a wall of amelodic texture instead. But, as Karlin so ably demonstrates in his score to The Stalking Moon, the juxtaposition of memorable melodies and effective action scoring is more interesting dramatically and musically.

Today, The Stalking Moon’s influence has been limited in part due to NGC’s dissolution and sale to Warner Bros. in 1974. For anyone willing to dive into this relatively undiscovered piece of American Western, few of the film’s immediate contemporaries adapted its thriller-influenced cues for their own purposes. Its depiction of American Indians is not as egregious as other Westerns and it appears to make some sort of attempt at commentary, but many of the damaging preconceptions of indigenous Americans make their way into the film’s screenplay. Yet considering the undemonstrative approach that Robert Mulligan takes for his film, The Stalking Moon is a serviceable Western torn between the passing of eras for the genre.

My rating: 7/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#The Stalking Moon#Robert Mulligan#Gregory Peck#Eva Marie Saint#Robert Forster#Noland Clay#Russell Thorson#Nathaniel Narcisco#Wendell Mayes#Alvin Sargent#Charles Lang#Aaron Stell#Fred Karlin#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

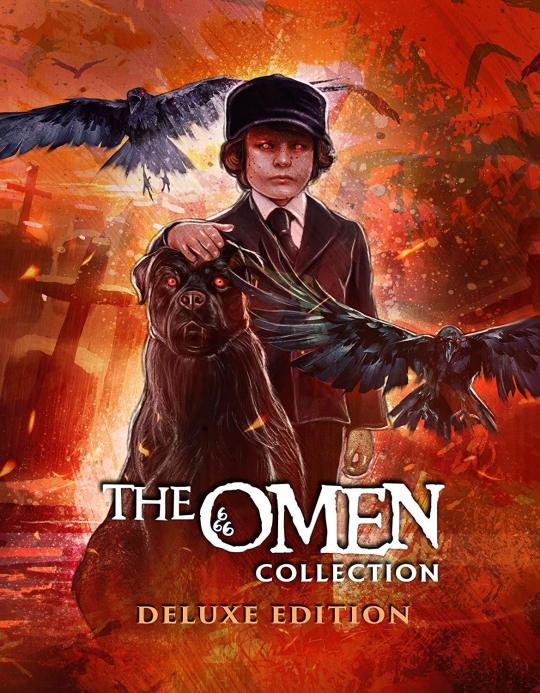

Blu-ray Review: The Omen Collection

In the pantheon of religious horror, the holy trinity consists of The Exorcist, Rosemary's Baby, and The Omen. Although The Omen arrived last, opening on June 6, 1976, it arguably offers more excitement than its satanic brethren (which is not to say that it is a superior film). Likely to be considered a slow-burner by today's standards, the picture builds tension and unravels a mystery at a meticulous pace, but it's punctuated by elaborate, Rube Goldberg-ian death scenes.

The Omen spawned a trilogy of films, a made-for-television sequel, and a modern remake. Scream Factory has collected all five movies in The Omen Collection, which is limited to 10,000 units. Besting Fox's earlier Blu-ray set - which omitted Part IV and featured some of the worst box set packaging known to man - each film is packaged in an individual Blu-ray case with original artwork within a rigid slipcover case. It boasts a deluge of extras, new and old.

In the original film, American diplomat Robert Thorn (Gregory Peck, To Kill a Mockingbird) and his wife, Katherine (Lee Remick, Anatomy of a Murder), adopt a baby named Damien (Harvey Stephens) after their own child is stillborn. Beginning with his fifth birthday, a string of mysterious deaths surround Damien. Upon being presented with convincing evidence by a photographer (David Warner, Tron), Robert becomes convinced that his son is none other than the antichrist, and he is faced with the task of stopping him to prevent Armageddon.

Firing on all cylinders, The Omen is an exemplary horror film. Working from a well-constructed script by David Seltzer (Shining Through, Prophecy), director Richard Donner grounds the story firmly in reality. The fantastical elements are easy to swallow, as each and every incident in the plot could be mere coincidence. Peck brings a gravitas to the production, leading a strong cast in which Remick also holds her own. Even the six-year-old Stephens, who never acted before and did very little after, is convincingly malevolent.

John Richardson's (Aliens, Harry Potter) special effects for the proto-Final Destination deaths - including one of the greatest beheadings ever committed on celluloid - remain shocking after more than 40 years. Cinematographer Gilbert Taylor (Star Wars: A New Hope, Dr. Strangelove) captures it all with clean camerawork, while Jerry Goldsmith (Alien, Gremlins) provides a chilling orchestral score elevated to pure evil with choral chanting.

The Omen has been newly mastered in 4K from the original negative, approved by Donner, for the new release. The result is a pristine presentation with improved detail and color saturation over Fox’s previous high-definition transfer. The Omen carries a whopping four audio commentaries. One, featuring special project consultant Scott Michael Bosco, is new. His audio sounds compressed - as if it were recorded on a cell phone - but it's dense with details focusing on the theological aspects. Bosco often digresses, but I appreciate the fresh perspective rather than a historian reciting IMDb trivia.

The other audio commentaries include: a track with Donner and editor Stuart Baird (Lethal Weapon, Skyfall), in which the two old friends reminisce about the highs and lows of the production; a track with Donner and filmmaker Brian Helgeland (Mystic River, L.A. Confidential), which features as much good-natured joking as it does insight; and a track with film historians Lem Dobbs, Nick Redman, and Jeff Bond, largely focusing on Goldsmith's score. A lot of information is repeated across the commentaries, but the varying viewpoints make them all worth listening to.

Seltzer and actress Holly Palance (who plays the nanny whose suicide by hanging is among the film’s most memorable moment) sit down for new interviews. Seltzer's chat is particularly enjoyable, as he's candid and humble. He openly states that his script is not as good as the movie it birthed. He also shares what he would have done if he had the opportunity to write the sequel. Palance, the daughter of the great Jack Palance, recounts her naivety about working on her first film and shooting her iconic death scene. The final new extra is an appreciation of The Omen's score by composer Chris Young, who says he looked to Goldsmith's progression across The Omen trilogy as he was scoring the Hellraiser films. It's fascinating to hear one accomplished professional praise another in their field.

All of the archival extras are ported over: a thorough, 15-minute interview with Donner from 2008; 666: The Omen Revealed, a 46-minute retrospective from 2000 featuring crew members along with religious experts to provide context; The Omen Revelations, which is essentially a streamlined version of 666, recycling much of its footage in 24 minutes; Curse or Coincidence, in which the crew recounts a variety of curious incidents that nearly derailed the production; an introduction by Donner; a deleted scene with commentary by Donner; an older interview with Seltzer, which features a lot of the same information as the new one; and an interview with Goldsmith about his score. There's also an appreciation of The Omen by filmmaker Wes Craven (A Nightmare on Elm Street), in which the master of horror waxes poetic about the influential picture for 20 minutes; Trailers from Hell trailer commentary by filmmaker Larry Cohen (The Stuff), who cites The Omen as one of his favorite movies; the trailer; TV spots; radio spots; and four image galleries: stills, behind-the-scenes, posters and lobby cards, and publicity.

Following the massive success of the first film, Fox fast-tracked a sequel, Damien: Omen II, to open in 1978. Having narrowly survived the events of The Omen, a 12-year-old Damien (Jonathan Scott-Taylor) now lives with his affluent uncle, Richard Thorn (William Holden, Sunset Blvd.), aunt, Ann (Lee Grant, In the Heat of the Night), and cousin, Mark (Lucas Donat), in Chicago. Damien is ostensibly a well-adjusted kid, unaware of who - or what - he is, but those who cross him wind up dead in freak accidents.

Omen II's plotting mirrors that of the first film, but the mystery aspect that made the original so effective is gone. The viewer knows from the start that Damien is, in fact, the antichrist, so they're left waiting for the characters to catch up. The plot dedicates an inordinate amount of time to Thorn's business enterprises, which is only vaguely paid of in the next installment when Damien rises to power. On the bright side, there are several admirably inventive deaths in the tradition of the first, from a bird attack that would make Alfred Hitchcock jealous to a visceral elevator bisection to a harrowing scene of a man trapped in a pond under ice.

Since Donner had moved on to Superman and Seltzer was either uninterested or not asked (depending on the source) to pen the sequel, a new creative team was employed. Stanley Mann (Firestarter, Conan the Destroyer) and Mike Hodges (Get Carter, Flash Gordon) wrote the script, with the latter set to direct. Hodges only shot for a few days, during which he quickly fell behind schedule, before being swiftly replaced by Don Taylor (Escape from the Planet of the Apes). Goldsmith returns to score with a worthy successor, retaining the signature sound while expanding it to incorporate electronics.

Leo McKern is the only returning cast member, reprising his role as archaeologist Carl Bugenhagen in the prologue. Peck's formidable presence is sorely missed, but Holden - who, incidentally, turned down the lead role in The Omen - and Grant bring some prestige to the production. Scott-Taylor is a convincing surrogate for Stephens, but the child acting leaves a bit to be desired. It's offset by a supporting cast that includes Lance Henriksen (Aliens), Lew Ayres (All Quiet on the Western Front), Sylvia Sidney (Beetlejuice), Allan Arbus (M*A*S*H), and Meshach Taylor (Mannequin).

Damien: Omen II's Blu-ray disc features new interviews with Grant, who is proud of the sequel and shares a funny anecdote about discovering her first wrinkle while filming; Foxworth, who was able to get to know Holden, one of his heroes, on their daily commute; and actress Elizabeth Sheppard, who proudly discusses working with Holden as well as Vincent Price (on The Tomb of Ligeia). In a separate featurette, Sheppard narrates a gallery of her personal photos from the shoot, offering a behind-the-scenes look at the bird attack sequence.

Since Omen II's mythology has little biblical foundation, Bosco's new commentary features even more tenuous tangents, but it affords him the opportunity to discuss the franchise more subjectively. An archival commentary with producer Harvey Bernhard proves to be a bit more informative. The disc also includes a vintage making-of featurette consisting of clips, interviews, and footage from the set, along with the trailer, a TV spot, a radio spot, and a still gallery.

The Omen trilogy came to a conclusion in 1981 with Omen III: The Final Conflict - although it proved not to be final after all. As prophesied, Damien (Sam Neill, Jurassic Park), now 33 - the same age as Jesus when he was crucified - has risen to political power. Following the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain’s ghastly suicide, Damien is appointed the position, which was once held by his adoptive father. The only true foe for the antichrist is, naturally, Christ himself. Rather than bringing about the apocalypse, as the franchise had been driving toward since the beginning, Damien attempts to prevent the second coming in a sanctimonious conclusion to the story arc.

While no successor could top the original Omen, its first sequel smartly embraced the gratuitous death scenes. For the third installment, however, director Graham Baker (Alien Nation) made a conscious effort to avoid them. Instead, he delivers inept monks trying to assassinate Damien with the Seven Daggers of Megiddo, while the antichrist’s legion of apostles murder newborn males who are the potential Christ child. Andrew Birkin's (Perfume: The Story of a Murderer) script leans further into religiosity at the expensive of the horror elements while interjecting silly mythology akin to Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers.

Omen III: The Final Conflict's Blu-ray disc features new interviews with Baker, who takes a truly retrospective look back on the film, comparing the society of today to that of when it was produced; Birkin, who hadn't seen The Omen when he first met for the gig and wasn't particularly impressed when he finally watched it; and production assistant Jeanne Ferber, who explains how she was among those polled by Bernhard to help choose the lead, with Neill selected unanimously.

For his final commentary in the set, Bosco is back to pointing out the film's connections to scripture, leading to a lengthy tirade comparing Christianity and Judaism. An archival track with Baker has a few nuggets of information among extended gaps of silence, but most of his points are addressed more concisely in the new interview. Special features are rounded out by the trailer, TV spots, and a still gallery.

Although The Omen’s main storyline continued with two more book sequels, Fox opted to use the familiar title for a made-for-television movie on their budding network in 1991. Although dubbed Omen IV: The Awakening, the film largely serves as a remake of the original film but with a female antichrist. After numerous failed attempts to get pregnant, politician Gene York (Michael Woods) and his wife, Karen (Faye Grant, V), adopt an orphan girl. Seven years later, Delia (Asia Vieira, A Home at the End of the World) becomes increasingly violent and manipulative, leaving a trail of bodies in her wake.

Similar to Omen II's production troubles, Omen IV started with Jorge Montesi (Turbulence 3: Heavy Metal) in the director's chair, but he was fire mid-shoot and replaced by Dominique Othenin-Girard (Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers). Writer Brian Taggert (Poltergeist III) keeps the basic structure of Seltzer's original script intact, but the details of each beat are altered and the death scenes are subdued for TV. In addition to gender-swapping the creepy kid, it's the mother who is proactive this time around.

Despite maintaining the general outline of The Omen, the plot is harder to believe this time around, stretching the required suspension of disbelief to include psychics that can read auras. The most ludicrous plot point comes in the form of a shoehorned connection to The Omen mythology. This "twist" canonically positions Omen IV as a sequel rather than a thinly-veiled remake, but it feels more like a low-budget knockoff than an official installment in the franchise.

Omen IV: The Awakening doesn't have any audio commentaries, but its Blu-ray debut includes a new interview with Taggert, who breaks down several of the major choices made in the script. It also contains The Omen Legacy, a feature-length documentary on the franchise that aired on TV in 2001. Narrated by Jack Palance (City Slickers), it finds cast and crew members (including a couple of folks who don't appear in any other special features) and religious figures (the Church of Satan’s high priestess among them) discussing all four films while playing up the alleged curse. The trailer and a still gallery are also included.

Amidst the onslaught of horror remakes that dominated the early 2000s, Fox shrewdly capitalized with The Omen in 2006 - on 6/6/06, to be exact. Director John Moore (Max Payne) offers slick production value and an inspired cast, but it feels wholly unnecessary considering how closely it follows the original script. Seltzer is the only credited writer, but it's unclear if his 40-year-old script was simply polished off or if he was involved in re-writes, as there are some subtle changes to contemporize it. While it fails to bring anything new to the table, it’s a stronger effort than Omen IV.

Liev Schreiber (Scream) and Julia Stiles (10 Things I Hate About You) star as the Thorns. Talented as they are, they lack the chemistry of Peck and Remick. Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick is successfully creepy as the new Damien, while the role's originator, Harvey Stephens, makes a quick cameo. In a particularly motivated bit of stunt casting, Mia Farrow (Rosemary's Baby) plays the antichrist's new nanny. David Thewlis (Harry Potter) and Pete Postlethwaite (The Lost World: Jurassic Park) also have supporting roles.

The remake is the only Blu-ray in the set that doesn't offer any new special features. The existing extras cover a lot of ground, but it would’ve been interesting to hear the crew reflect back on it. Omenisms is a 37-minute documentary exploring the pressures of making a movie with a release date set in advance, even showing Moore losing his temper and yelling at a producer. It feels very of its time, with director Stephen French treating the piece like a hip art film, but it contains a lot of great material.

Moore, producer Glenn Williamson, and editor Dan Zimmermann participate in an audio commentary that's fairly informative but doesn't touch on many of the trials and tribulations showcased in Omenisms. There's also a featurette about Marco Beltrami (Scream) recording his score at the legendary Abbey Road Studio; Revelation 666, a cheesy TV special tracing the history, interpretation, and theories of 666; unrated, extended scenes, including a longer version of the ending; and theatrical trailers.

While The Exorcist remains the be-all and end-all of occult horror, The Omen franchise as a whole is more consistent. The first three Omen films comprise a cohesive trilogy, while Part IV and the remake each offer a fresh, if flawed, perspective on the material. Between the movies, commentaries, interviews, and featurettes, The Omen Collection contains over 30 hours of content, making it an unbelievable value and a must-have for any horror collector.

The Omen Collection is available now on Blu-ray via Scream Factory.

#the omen#gregory peck#damien: omen ii#omen iii: the final conflict#omen iv: the awakening#mia farrow#scream factory#dvd#gift#review#article#damien thorn#liev schreiber#julia stiles#lance henriksen#lee remick#william holden

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Whoa, I had no idea this game came out on the Saturn! The first Discworld point and click game is kinda like the DK64 of the genre. Very intricate and ambitious, but it brings every single fault and frustration of the genre to the forefront and pretty much contributed to the death of the genre.

I must admit I am not quite as knowledgable as I should be about the timeline of British comedy. Children were supposed to know Tony Robinson from Blackadder but not know Monty Python at all? I actually not remember him being in this game, let me check IMDb to see what he plays...Hmm...”Dunnyman” and “Dog”? So proto Harry King and Gaspode the Wonder dog? That is quite a legacy!

#sonic the hedgehog#stc 92#discworld#donkey kong 64#ankh-morpak is my new nickname for the game version of ankh-morpork

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 24

Reflections on: Transylvania 6-5000 (1985)

Wow why did anyone say this was a horror film? This is a wacky comedy.

This paints Transylvania as a backwards place full of zany people.

I was hypnotized by Jeff Goldblum and Ed Begley Jr.’s floofy hair.

All the phones are animals for some reason (see above).

Michael Richards plays a proto-Kramer type character that is so slapstick it’s actually alarming and off-putting to sit through.

Geena Davis plays a sexy dracula. This is where she and Jeffy met.

The fashion was great, but this was difficult to watch.

According to imdb trivia this “was financed by the Dow chemical company in order to spend frozen finances (money that could not be spent outside the country of origin) that the company had in Yugoslavia.”

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

IAC Reviews #014: Have a Nice Weekend (1974)

Another day, another boring time in isolation. I’d say it has me looking forward to the weekend, but it’s not looking like I can say that with confidence any time soon. It might be the dead of summer, but it doesn’t feel like it in spirit. Seeing as how we encountered woodland cannibals the last time we tried to get away, let’s see where our journey will take us this time. I just hope we make it out alive in one piece, assuming we won’t be bored to death!

_______________________________________

I want to say I heard about this vintage gem here via The Burial Ground or someone from UTM before it went under. However, like many titles on my ever-growing watchlist, I always pushed this one to the back burner for a rainy day, and today is that special day (thanks to Wheel Decide)...great.

Have a Nice Weekend is a 1974 horror-mystery “proto-slasher” (and I say that in the loosest way possible) film directed by Michael Walters, and follows a basic And Then There Were None type of formula where a group of family and friends go on an island getaway trip to celebrate the return of a loved one, Chris, who was discharged from the war, and they find themselves being picked off one by one. If the low quality VHS transfer has much to say about what we’re in for, then my expectations for this being anything noteworthy are dropping from the opening title card sequence.

Have A Nice Weekend in One Gif:

Oh, well...that sure was something. I don’t know exactly what it was, but it was something.

________________________________________

I didn’t have high expectations going into this, and I guess it was good for me to keep the bar as low as I did so I wouldn’t have had to worry about getting my hopes up for nothing. As I said at the start, I wasn’t too hopeful that this would be anything of real interest judging from the quality of the film overall.

The opening sequence has a lot of moments where the footage is blurry and out of focus, making it hard to tell to me if it was an artistic choice or it was purely on accident. The other thing to note was the sound wasn’t all that good either, which made it all the more complicated to tell if the line delivery was just naturally awkward and clumsy or it was like that in post when they did some clear ADR - or what I think is ADR.

Yeah, we’re not off to a good start. Also, did I mention that Chris as PTSD-related flashbacks to the war? Yeah, that happens. It starts to feel like we’re about to ease into the trope we’d see later on with films like Deathdream (1974) and Naked Massacre (1976), and whether or not the pay-off will be worth it or not. If I had to give some sort of positive comment to say about the film, it’s that the New England scenery is nice - well, what you can make of it that is. If it ever gets restored at some point, it gives me something else to talk about.

I’m not sure if this is a result of me not paying close attention to what was going on, but the majority of the characters were largely forgettable. It also doesn’t help the acting isn’t very good, and, as a reviewer on IMDb said, the actors seem confused or disinterested about what they’re doing and what’s going on. I made light of it earlier with how they react to stumbling across the first murder victim, and if you weren’t sure how much hope you should have invested in this, then let that be your cue to drop the bar while you can because things aren’t going up from here. It’s almost secondhand embarrassment, and just wait until you get to the “it’s a one-man job” scene. Oh, that’s somethin’!

Along with the sloppy line delivery, the rest of the film is being held together with glue and popsicle sticks with how poorly it’s structured and the glaring plot-holes doesn’t help it out much either. Two examples I can think of when it comes to this logic vacuum is in the first murder reveal, they establish how they were killed off and talk about moving the body even though it will tamper with the crime scene. But, then in the next scene, they say they don’t know how the murder happened and then later berate one of the characters for picking up the murder weapon because it will tamper with the evidence. It should also be noted that the weapon was dropped just several feet away from the body, and it’s not like the killer made it a point to hide it either.

Do you see what I mean? It feels like nobody bothered to proofread the script or point out how this doesn’t make any sense.

The third act tries to build some tension where we see everyone trying to put the pieces together with their own theories behind why one of them would be the killer; be it jealousy or past relation problems, and it comes off as weird and almost dreamlike in nature. This isn’t helped either by the line delivery or needless padding either; such as a ten second sequence of just a picnic table or the aforementioned “one man job” scene I was talking about before. Nobody here sounds real or like they have any sense of awareness for what’s going on around them. That would explain why the actors sound so confused or disinterested in what’s going on. This is another movie where things just sort of happen and “this is what we’re doing now”.

The reveal comes out of left field at the very end of the film, and we wrap it all up with an epilogue to explain just what the hell happened if you were left just as confused as I was. I’m not sure what I think about the twist if I’m being honest or if I would have preferred it to have been some wild maniac like all the slashers that would come after this. Well, that and if the epilogue just feels lazy because the writing was overall poor to where it became a case of show don’t tell.

________________________________________

So, where do we go from here with this one?

There wasn’t really a whole lot to comment on because it sort of speaks for itself. The soundtrack was minimal at best, so I can’t say whether or not it was good or not. There wasn’t a ton of gore or violence either, but when it was there it was just average at best. There’s next to no characterization or arcs going on, so that’s off the board as well. If the quality was better, I’d say the visuals might be the only thing going for this. It’s also hard to say how much of the cast went on to do much else after this, considering that not everybody is mentioned on the IMDb page.

I don’t know about this one. It’s just rather dull and forgettable, and it’s no wonder why it only has 49 ratings on IMDb either. Perhaps there’s another timeline where this was better and more noteworthy, because maybe then we all could have had a nice weekend.

RATING: 3.2/10

#iac reviews#have a nice weekend#film#horror#whodunit#slasher#proto slasher#70's horror#70s horror#1970's horror#1970s horror#low budget horror#obscure horror#indie horror#horror movie#horror movies#horror review

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Alien: Covenant"- A beautiful failure.

(NOTE: As with many of my reviews here, this was taken from my IMDb profile, hence references to how it was my 500th review on that site.)

I was ready to write my 500th IMDb review on a special film that meant a lot to me in order to commemorate reaching such a number. And I was thinking about what I could possibly pick... perhaps my favorite television series? Or a game I highly admired? Perhaps a review of my favorite guilty-pleasure? Or find the movie I thought was the greatest ever made? It had to be something meaningful. And then I saw "Alien: Covenant", and I had my answer. My 500th IMDb review will be not for a great film, or one I admired. It will be in recognition of perhaps the single most disappointing cinematic experience I've ever had. Yes, Ridley Scott's return to the "Alien" saga began on a shaky note with 2012's mediocre "Prometheus"- a film that was stunning to behold but ultimately half-baked in the story department. But oh boy, does he outdo himself with "Alien: Covenant!" I wasn't expecting this. It's almost heartbreaking, because Scott gets the entire film so fundamentally wrong. It's to the point that "Covenant" reaches the brink of being near unwatchable at times. And beyond that... it's so thoroughly ludicrous, it almost retroactively makes the earlier installments less enjoyable merely by association. It's that bad. A vessel known as "The Covenant" is on a mission to the planet Origae-6, where a human colony will be established with a crew and passengers kept in deep hibernation, and the ship under he supervision of android Walter (Michael Fassbender). However, an unexpected neutrino blast cripples the ship and kills several crew and colonists. Awakened, the remaining crew are forced to make a hard choice when in the aftermath of the blast, a distress signal is found on a mysterious nearby planet. Descending to its surface to investigate, the crew shockingly find this previously unknown world to be a suitable analog for Earth thanks to a similar atmosphere... well, if it weren't for mysterious spores that impregnate several crew- members with proto-xenomorphs and the appearance of the android known as "David"- now the sole survivor of the "Prometheus" disaster! From there on, it's a race to survive a tangle of plot- lines as David's motivations are questioned, the crew attempts to defeat the new alien threat and the audience tries to care! In a lot of ways, the problems audiences had with "Prometheus" are back in this follow-up- from the smallest nit-picks to the grandest logical errors and examples of faulty writing. It's very much a film where you can count along with the glaring gaps in reason and execution with each passing minute. The only thing is these issues seem substantially exacerbated by a general apathy and sense of "going through the motions" on the part of the creative team. There's no heart here as there was with "Prometheus." Say what you will... it's clear that there was a drive and effort behind that film. And when the resulting reception ended up mixed, Ridley Scott went back to the well and simply tried to make a film that was cosmetically similar to his iconic original. And that's not spoiling anything- it's in the darned title! And we end up with a film that's merely a pale imitation of what came before, leaving it a wholly monotonous and dull experience. Yes, Scott's trademark visual direction is as gorgeous as ever... but it's to the service of nothing but copying and pasting, with less thought and an added sense of convolution as it must now bridge "Prometheus" and the original "Alien." Not that I lay the blame entirely at the feet of Scott, as there is also the poor writing courtesy a small army of screenwriters. There is a distinct lack of character establishment and development outside of Fassbender's admittedly delightful dual role. Not a single human character feels real or fleshed- out in the slightest, and the bulk of the cast come across like they're playing animated versions of the cardboard cut-outs for the film you see in your theater's lobby. Which is a shame, as there is some good talent involved, including the likes of Katherine Waterston, Billy Crudup and Danny McBride, who oddly enough gives the best performance of the film outside of Fassbender. The pacing of the writing is also suspect, especially in the opening act, which is both needlessly drawn out but also vapid because we're just seeing "stuff" happen with no characters to root for. The script never finds the balance between story and character... so we're left with nothing but tenuously connected plot-beats that transparently only exist to bring us from one sequence to the next, peppered in with the occasional awkward insertion of a reference to the previous films for contrived fan-service. It's hack writing 101. And to top it off... The film feels unnecessary. I hate to say that, because no film is technically necessary. But in the grand scheme of a franchise, there needs to be a purpose to exist or else it just feels like a cash-grab. And this feels like a cash- grab. By virtue of its own design (and again, this spoils nothing), you can't do much outside of complicate the backstory with twists and turns in a prequel such as this, which lends a strange level of unbelievability to the earlier installments. The original four-film series was haunting, and the aliens themselves were a menace that the characters happened upon. Now, with added layers of religious subtext (don't get me started on Crudup's cringe-worthy persecution complex the writers tossed into one scene), nonsensical insertion of numerous new locations that the aliens are infesting, and "Prometheus" suggesting that the xenomorphs are some weapon experiment... and I just don't buy it tying together. The one-two punch of "Prometheus" and "Alien: Covenant" cheapen the whole series. "Alien: Covenant" is a woefully misjudged and shockingly dull tale that takes the series to new lows. And for that, I give it an abysmal 2 out of 10.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

31 Days of Halloween #25 Spider Baby Imagine those old spooky 60's sitcoms like The Addams Family or The Munsters but instead of just being lovably spooky and eccentric, like, they actually fucking murdered the shit out of their guests cuz that's what Spider Baby is. Yo right off the jump if you have an original theme song then I'm gonna bump that shit. And seriously while this song is great it's made even better by the fact the garbled gravelly voice sputtering through the song belongs to the fucking horror legend Lon "the motherfucking Wolf Man" Chaney Jr. The film itself is fun as fuck and weird as hell. It feels like if they made Texas Chainsaw Massacre into Saturday morning children's programming. It features a family that has like Benjamin Button's disease but only for their brains and it just keeps going until they become pre-natal minded cannibals? Wait what the fuck does cannibalism have to do with prenatal consciousness? Are they talking about proto-humans or something, I'm guessing like cavemen but were cavemen known to eat people? Idk, maybe don't check the science on this one because science is for nerds and nerds get eaten by cannibals, ya hear. Plus there with all this crazy shit going on there's this character uncle or cousin Peter (I forget his relation) but he happens to be the most understanding and chill dude on the planet. Good for him, he's like a nice guy, and apparently according to IMDB he's one of the writers for The Deer Hunter wtf!?! Also Lon Chaney Jr is the fucking man and Sid Haig is gold as always may he rest in peace you crazy bastard. #horror #horrofanatic #horrorlover #horrorjunkie #horroraddict #horrorfan #horrorgram #horrorfilm #horrormovie #horrornerd #movieoftheday #moviereview #filmreview #instagram #instagood #instafilm #instahorror #horrorgeek #31DaysOfHalloween #Halloween #October #31DaysofHorror https://www.instagram.com/p/B4DgSU9FANM/?igshid=1la76ulzirxxt

#25#horror#horrofanatic#horrorlover#horrorjunkie#horroraddict#horrorfan#horrorgram#horrorfilm#horrormovie#horrornerd#movieoftheday#moviereview#filmreview#instagram#instagood#instafilm#instahorror#horrorgeek#31daysofhalloween#halloween#october#31daysofhorror

0 notes

Text

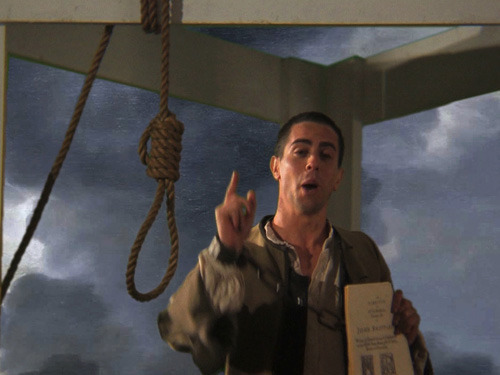

Notes on “The Last Days of Jack Sheppard”: Capital Crimes and Paper Claims

[by Benedict Seymour / Mute]

Introduction by Rogue: This film was an art project originally screened at the Chisenhale Gallery, London, in 2009. From the artists’ site: “The Last Days of Jack Sheppard is based on the inferred prison encounters between the 18th century criminal Jack Sheppard and Daniel Defoe, ghostwriter of Sheppard’s ‘autobiography’. Set in the wake of the South Sea Bubble of 1720, Britain’s first financial crisis, the film is a critical costume drama constructed from a patchwork of historical, literary, and popular sources. It traces the connections between representation, speculation and the discourses of high and low culture that emerged in the early 18th century and remain resonant today.”

There were no commercial screenings, it has no IMDB entry, and as far as I can tell it can’t be downloaded, legally or otherwise. So I’m reposting here the review of a film/art installation that I haven’t seen and probably never will, and that YOU haven’t seen and probably never will, because it’s a damn interesting story. Also, long post.

The Last Days of Jack Sheppard (2009), directed by Anja Kirschner and David Panos, retells the story of a proletarian hero of the early 18th Century who ending his days at the gallows – ‘the triple tree’ – in Tyburn in 1724, was executed for theft at the dawn of financialisation.

Jack Sheppard wasn’t much of a thief. Serially incarcerated during his short life, he won fame for his ingenuity and implacable dedication to getting out of gaol. This is years before Houdini, with his spectacularised escape artistry and proto-Fordist routinised liberation. It is years before David Blaine, who inverted the trope of getting free into feats of hyper-visible confinement endured. Jack’s very public demise is furthest from but for us also closest to the telematic death and redemption of Jade Goody, a working class woman who, like Jack, also found fame in dissolution.

Unlike Jade, however, Jack stood for a certain resistance to commodification and the intrusion of the State into one’s intimate processes of self-reproduction.1 Like her he rose to fame in the wake of a suddenly deflated financial bubble. The Last Days of Jack Sheppard plays on the interconnections between his acts of criminal reappropriation and the speculative adventures of the wealthy during the South Sea Bubble of 1720. As much as anything, Jack’s notoriety was about the contrast his crimes made with the legally sanctioned scams of his social superiors; his bravery, fortitude, skill and cunning versus his superiors’ petty self-aggrandisement and greed. Jack also remained independent of corrupting tendencies within his own class and refused to join in the rackets of Jonathan Wild, self-appointed ‘thief-taker general’.

For these and other reasons we will come to, Jack was one of the first heroes of popular culture. His ghost-written biographical Narrative appears as an early act of proletarian public speech. A posthumous publication, the Narrative is based on the words of a man condemned to death; a man escaped and recaptured who is given the right of representation only when he has nowhere left to run.

Near the beginning and end of the film the notorious housebreaker and escapologist (four times escaped from prison, four times recaptured) invokes his right to speak. He holds up the manuscript of his memoirs to the crowd as he stands before the gallows, a dialectical image of the decisive forces of his age. The scene brings everything together – capital and capital punishment, money and representation, the mob and their hero. Jack steps up onto the platform to have the last word, to give his own account and put right earlier misrepresentations. However, the film sardonically notes that this last gesture of self-assertion is already, also, a piece of advertising. Jack’s publisher Mr Applebee is at hand to tout the completed Narrative – ‘available for 6 pence only from Applebee’s’. In the background, as we shall see, there is the anonymous ghost-writer of the text, Daniel Defoe.

It may be considered a moment of resistance, a claim to rights that were not supposed to be issued to people of Jack’s class. As such it is also an attempt to use the bourgeois representational apparatus to get something material back – control over his own history and a legacy for his mother. This last raid on the emerging finance/culture nexus is carried out within the terms of the law and of the market. Like the stocks and bonds of the bankrupted stockjobbers glimpsed in the wreckage of the South Sea Scheme at the beginning of the film, Jack’s Narrative is itself a kind of ‘paper claim’ on value. Behind it lies a contract, and a title to sales revenue, but in itself the Narrative is a fiction, a projection of what his life will have meant. Furthermore, Jack is not the real, or at least the sole, author. The film’s diegesis continues and exacerbates the logic of displacement by putting into his mouth words that others would only have read on the printed page, pointing up the artificiality of the mise-en-scene and, by extension, of the public sphere.

Jack’s moment of free and direct expression, of the right to tell one’s story and give one’s own account of one’s self, is also the moment of commodification. Destitution recapitulated. Alienation consolidated by claims of complete transparency (Defoe’s vanishing mediation). The moment of truth is the moment of fiction, of a constitutive falsehood analogous to the wage labour contract in that it is both ‘authentic’, legally recognised and a kind of betrayal of at least one of the consenting parties. Jack becomes a virtual player in a textual construct, enabling us to retell and rework his story, but objectifying and distorting his necessarily open-ended subjectivity. Death launches him on the literary market. Analogies to paper money and credit here are not accidental: representation opens up the possibility of derivatives, variants, meta-fictions.

The act of representing one’s self – as the film explores – depends on just such objectifications, a process of displacements and substitutions which put the speaker’s identity and status (living/dead, rich/poor, etc.) in doubt. Jack breaks through the social repressions of his day to speak up for himself and, by extension, his class, but he is also spoken for. His words are put to work. The future development of working class struggle to escape from capitalism is foreshadowed here. The question is implicit throughout – how does the subject/object of history, neck in the noose and facing extinction (or perhaps the mutual ruin of the contending classes), get out of this one?

As in life, he had to alienate his considerable skills as a carpenter in the service of others’ accumulation of capital, so in death Jack’s voice is ventriloquised and exploited by Messers Applebee and Defoe for their own ends. Equality is the very form of inequality; the contract guarantees the subordination of the economically dependent and the reproduction of their alienation. Jack makes history, or at least his history, but not in conditions of his own making. And what will history make of him? The film is hyper-conscious of the potential and risks of myth making, yet in order to pose the question of Jack’s legacy, of his contemporary significance and indeed the future of his class, it is necessary to put him in the frame; the film has to borrow and trade on his legend.

The early 18th century represented here is an age of ‘projections’, of new financial abstractions, schemes and scams, exerting an increasingly autonomous force in social life. Jack’s story, at once a critique of the self-contained world of the stock exchange, the Mansion House and the coffee house, is itself a highly mediated claim to authenticity, a work constructed by Daniel Defoe giving the illusion of a first person account. However, true to Jack’s own language and history, it is necessarily a work of (real) abstraction. For a growing market, Jack’s life has become a kind of ‘structured investment vehicle’, a spectacular commodity with an existence independent of the unruly mob who flocked to his hanging. In death, his social mobility is potentiated.

Jack’s rebirth (or undeath) as a literary figment and popular hero, like the floating of a new concern, is a hostage to the market and to the stories people will construct as derivatives of his ‘authentic’ paper representation. Once written down, he is no longer free to determine his story. The film itself is one such derivative, taking as its premise a hypothetical struggle between the Narrative’s two authors – the ghost writer and ghost-written, Defoe and Sheppard – over the content of the biography. By positing this ur-narrative or pre-textual struggle the film is able to reopen what the Narrative tried to close. It is a narrative back-projection which underlies and echoes the film’s other projections, its allegorical/art historical décor made up of prints, paintings, drawings and other artefacts from the period.

Long ago, Frederic Jameson identified postmodern culture’s ‘renarrativisation of the fragment’ as a kind of recycling, reinscription and domestication of modernist practices of disjunction. What distinguishes The Last Days use of parody from this form of blank referentiality is its heightened awareness of the economic determination of and struggle over signs. Where Jameson sees in postmodern culture’s abstraction and reflexivity an analogy to finance capital’s attempt to defer and get around the underlying tendency to crisis in capitalist production by proliferating virtual capital, this particular art work turns the logic of cultural looting in on itself. The result is an emphasis on the perpetual presence of economic relations of domination in capitalist culture tout court. The struggle between Jack and his literary representative is not a mere conceit by means of which to squeeze a new work out of an old one, an ‘exotic literary instrument’ that yields a domesticated and carefully captioned blast from the past. Instead it pushes renarrativisation into overdrive, offering a web of analogies and historical allegories.

By enquiring into the effectivity of signs, the performative power of fictions – economic, literary, biographical – the film is also alert to the way ‘paper claims’ function primarily as ways of appropriating the (rest of the) material world. Money is essentially a title to future value, a ‘licence to loot’ insofar as the paper titles to capital which capitalists deal in always project ahead of the world, ahead of existing value, through the process of capitalisation. Signs, however apparently free-floating and autonomous, tend to intersect in the most brutal ways with processes of accumulation, equivalent and non-equivalent exchange. Paper claims exact work and life from the labouring bodies they command. In the case of the film, the key moment being the separation of peasants from the land and the production of the urban proletariat of whom Jack is a part. Money, State and the banking system are results and, it should be stressed, products of the (perpetually renewed) dispossession of the poor from all independent means of subsistence. Paper claims are worthless without the State to back them up, and the projections of the financial elite are likewise predicated on a brutal ‘framing’ of the poor.

This brings us back to the triple tree. Execution is the most profound form of recognition which the ruling class can offer one such as Sheppard. It’s also, however, a way of negating identity completely. Capital punishment makes the criminal at once particular and equivalent. Use of the gallows was calibrated around the price of commodities, and hence the socially necessary labour time reappropriated by the malefactor and unreliably echoed in the (jurors’) estimate of the prices of the stolen commodities.2 But the gallows were indifferent to the arguments and aphorisms that a proto-literary figure like Jack was capable of (‘One file is worth all the bibles in the world’). Jack’s (illicit) claims are answered by his definitive transformation from subject to object – the inversion on which capitalism runs made horribly explicit. The ‘moment of [his] dissolution’ is the moment of his complete reification, and, with the help of Defoe and Applebee, the moment at which he gains access to the official means of representation, becoming the subject of a new kind of separation, a second order of (linguistic) enclosure. His death sentence and its execution opens up the space of representation, the dimension of fiction, fantasy, financial projections and speculative futures. Indeed, as we have said, Jack is ‘floated’ as much as hanged and his Narrative becomes the stuff of, or rather for, Legend. A story is born with the death of its protagonist, the Narrator (in the manner of a film noir such as D.O.A.) is already posthumous. Like Jade who survived to read her own obituary, there is something zombie-like about the public proletarian, not lacking in wit, far from wordless, but at the same time, as Applebee puts it, ‘doomed’. The sympathy of the public sphere for marked men and women is already, at this historical moment, the most suspicious thing about it.

There is something rather ‘aesthetic’ about this final instant, then. To quote one of the newspapers of the day, Sheppard was hung up and ‘dangled in the Sheriff’s picture frame’ for 15 minutes. ‘The sheriff’s picture frame’ makes clear the tacit connections between artistic and literary representation and the State’s repressive apparatus. Beyond any Warholian undertones, the link between execution and celebrity is not just via the struggles over the body of the malefactor, the crowd’s identification with the victim or the ballad sellers’ narration of their life and times. In fact, the gallows are aesthetic insofar as it constitutes a crude means for communicating a message to those that can read Jack’s broken body. The State itself requires notoriety to get its point across. This is spectacular language aimed at the (mostly illiterate) early proletariat. Not for them Jack’s ghost written Narrative.

The message is the imposition of work. Commodification uses death to communicate its imperatives to the living through the mediation of exemplary delinquents. As the film presents it, Jack is an escape artist captured first by the fascinated artists of the aristocracy (Thornhill paints Jack’s portrait while the felon is chained up in Newgate, shades of Fassbinder’s Fox and his Friends, here) and then definitively by the art of the State. As Peter Linebaugh frames it in his great book The London Hanged, the triple tree was not so much the final stage for disposal of society’s ne’er do wells, as one of the foundations of the economy. Capital punishment was a part of the production and reproduction of the poor as workers, it was there to teach people a very definite lesson. Founded on the originary violence of primitive accumulation – the separation of people from their collectively held property through the enclosures – early capitalism attempted to instil in those that produced its wealth the necessity of toil. Those who refused to submit to the imperative of making their living by taking what they needed to subsist – or like Jack, flaunting a desire for luxury deemed out of his social reach, luxury beyond reason or measure – would be made an example of. The triple tree was the most important prop in a theatre in which the insubordinate were turned into the unfortunate protagonists of a cautionary tale.

But the State did not have complete control over this stage or the stories told about it; both the criminals and the mob were given an opportunity by the very public nature of the spectacle. Jack’s speech in the film sums up the way in which the stage of instruction was being turned into a site of contestation, a place in which the poor might talk back and challenge the ongoing process of separation by which work was imposed.

Revolts at the points of instruction, punishment and incarceration were in turn providing the raw materials for goods in the literary market place, another node in the production and circulation of commodities. The spiral continues, from enclosure to escape, re-enclosure to re-escape, re-escape to re-enclosure. Remorseless, and contingent, one recalls Marx’s famous formula for the mutation of money into more money: ‘M-C-M’. Capital wants it to continue in a seamless cycle, but in reality there are many obstacles to valorisation – Jack is just one example.