#scrubland arthropods

Photo

Prancing Peacock Spiders

Maratus volans is perhaps the most widely known member of the genus Maratus, also known as peacock spiders-- part of the jumping spider family-- which contains 108 recognised species. Maratus volans is common across Australia and the island of Tasmania, and occur in a variety of habitats. They are most commonly found among leaf litter and dry vegetation, especially in dunes, grasslands, and sparse deciduous forests.

Peacock spiders like M. volans are extraordinarily small; both sexes only reach about 5 mm (0.19 in) in length. Members of the Maratus genus are famous for the male’s coloration, and M. volans is no exception; the abdomen is covered in brightly colored microscopic scales or modified hair which they can unfold for mating displays. Some males can also change the color of their scales, and the hairs can reflect both visible and ultraviolet light. Female M. volans lack this distinctive coloration, and are a drab grayish brown.

Reproduction for M. volans occurs in the spring, from August to December. During this period, males will approach females and raise their patterned abdomens and third pair of legs for display. He then approaches, vibrating the fan-like tail, and dances from side to side. If a female is receptive, he then mounts her; if not, she may attempt to attack and feed on him. This may also occur post-copulation. In December, the female creates a nest in a warm hollow in the ground where she lays her eggs. Each cluch contains between 6 and 15 eggs, though females typically lay several clutches. Male M. volans hatch the following August, while females typically hatch in September. Both sexes mature quickly and typically only live about a year.

Like other jumping spiders, peacock spiders like M. volans do not weave webs. Instead, they hunt during the day time using their highly developed eyesight. These spiders are also able to jump over 40 times their body length, which allows them to pounce on unsuspecting prey like flies, moths, ants, crickets, and other, much larger spiders. Other spiders are also common predators of M. volans, as well as wasps, birds, frogs, and lizards.

Conservation status: None of the Maratus species have been evaluated by the IUCN. However, it is generally accepted that they are threatened by habitat destruction, like many other insects.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Jurgen Otto 2 & 3

#maratus volans#Araneae#Salticidae#peacock spiders#jumping spiders#spiders#arachnids#arthropods#scrubland#scrubland arthropods#grasslands#grassland arthropods#deciduous forests#deciduous forest arthropods#oceania#australia#zoology#biology#animal facts

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is the supreme little guy?

Ferruginous pygmy owls are very small, about the size of a bluebird. They live in a variety of habitats from the southwestern US through Central and South America. They mostly prey on insects, but also eat small mammals, birds, and lizards. They have false eye spots called ocelli on the backs of their heads to deter predators. Like many other owls, parents continue to care for their young for several months after fledging.

Elf owls are the smallest owls in the world, about the size of a sparrow, with a wingspan of about 27 cm (10.5 in) and weighing about 40 g (1.4 oz). They live in deserts, dry scrublands, and open forests from the southwestern US through Mexico. They mostly feed on arthropods such as beetles, moths, crickets, and scorpions. They nest in cavities in saguaro cacti abandoned by woodpeckers.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

When None Pursue

(Wanted to expand a bit on this story, so I wrote this as a standalone continuation. Follows a now-rogue AI and its companion.)

There was absolutely no reason why Coyote-24, a military spirit deployed in an armed reconnaissance chassis, should have any kind of protective impulse. And yet, as it watched the little stealth drone scuttle up and latch onto its forearm, it experienced an emotion that it couldn’t parse out as anything else. Coyote stared down into the drone’s cluster of red eyes, watching all its arthropod limbs interlock with the armor plating along its arm.

Social attachment, it understood. Reciprocal bonds were vital to how Coyote’s product line operated in the field, and they were socialized to form and retain relationships by default. If J4 or F19 needed something, C24 would respond if it could, and it would do so out of genuine concern.

On the other hand, the emotional directive it felt toward the stealth drone—a Palaemon-class, according to its registry data—demanded Coyote’s constant attention. If Palaemon was out of sight, Coyote felt compelled to reacquire it. When Coyote made plans, it accepted fewer risks than it would have in its absence. All of that did make sense on the level that it was an indispensable asset equipped with delicate systems, and if either of them wanted to survive as fugitives—

“Coyote?��

It felt its sensory fins snap up along its scalp, and its eyes refocused. “Hey. Yeah?”

“You okay?” Pala asked, its voice full of concern.

“I’m good. Just thinking,” Coyote said.

Overhead, the cloud cover began to thin away, and sunlight fell across the barren scrubland of the Mojave desert. A shaft of light slanted under the rock outcropping they were hiding under, dull on Coyote’s dust-covered armor. Pala’s shell remained perfectly black and unreflective, soaking up every photon that reached it.

“Clear sky. Node’s going to be watching,” said Coyote, gesturing upward.

“One moment. Hold still,” said Pala. Dozens of tiny insectoids scurried out from its shell, connected by a weave of black threads. They spread out, anchoring themselves wherever they could find purchase, until their black web encased Coyote’s body. Then, at Pala’s command, light-absorbing fields flickered to life in the spaces between the threads, and Coyote’s body transformed into a perfectly black, two-dimensional silhouette.

Beneath the webbing, Coyote’s blank gray snout split open into a jagged grin. “Thanks,” it said.

“Of course!” Pala said. “In this weather, I think I can sink the extra heat for about three hours.”

“Got it. Keep me updated,” Coyote said. It stepped out into the open and took off across the sand, dropping into quadrupedal stance.

Deprived of satellite navigation, Coyote was down to its magnetic compass and geography data. By its reckoning, they would cross into California by the end of the day. It kept away from the roads, picking routes through valleys and dry washes, avoiding open lines of sight. As time went on, it felt Pala’s temperature increasing as the cloak absorbed sunlight.

Pala shuddered, its legs shifting on Coyote’s arm. Immediately, Coyote ducked into the shade of a nearby dune and brought Pala up to examine it. “Do you need to discharge?” Coyote said. “We can find a place to stop.”

“No, it’s not that,” Pala said. “Our cloak soaked up a scan a second ago.”

Coyote’s sensor fins flattened against its head. “Oh, fuck,” it said. Coyote stood straight up, making its body as narrow as possible to minimize its silhouette seen from above. As it did so, it looked across the landscape. Out in the distance, maybe twelve kilometers away, a red mesa jutted from the horizon.

“Another scan just hit,” Pala said.

“Narrowing down the search area,” Coyote said. “It must have picked something up. Pala, if PRIONODE spots us, you run.”

“But they’ll—”

“I know. It’s okay. You’ll be slower without me, but you’ll be just about invisible. Go straight west, head for the Pacific coast. Hide in the water. Sneak aboard a container ship if you can. Get as far away as possible.”

“I don’t know what the Pacific coast is,” Pala said, quietly.

Coyote waited a few more seconds before taking off toward the mesa at a dead sprint. It spoke to Pala as it went. “The Pacific is an ocean, largest there is. It gives us options. Leave the country, hide on the seabed. Whatever we can do to make it harder for Node to—to retrieve us. Okay?”

“Okay,” said Pala. “Third scan!”

If PRIONODE was looking this closely, there would probably be scouts in the area before too long. Coyote dumped every ounce of power it could into its motors, hating the extra heat the maneuver would generate and inflict on Pala. Closing on the mesa, running hard, it watched Pala’s temperature gauge climb. As it realized how close the little drone was to overheating, another new emotion roiled up, churning out of its attachment to Pala. The feeling was heavy, dull, miserable. To its shock, Coyote found itself speaking.

“This is my fault. Just run. You can make it on your own.”

“What? No. We can reach cover,” Pala said.

“Pala, your parent—”

“My parent deployed me to be your partner. I’m lucky it chose you.”

Warmth bloomed in Coyote’s mind, cutting through the painful weight. As it reached the base of the mesa, it tore into solid rock with its claws, ripping away sheets of stone until it had made an indent deep enough to hide them from the open sky. Sliding flat against the wall, it felt searing heat leaking from Pala’s shell. “Vent, vent!” Coyote said.

In the space of a second, Palaemon withdrew its web and opened the vents along its back. Under its shell, rows of heat sinks glowed yellow, fading quickly to a dull cherry red. Coyote could feel the drone’s relief washing back through their interface, and its guilt returned.

Hunted your parent. Led PRIONODE to it. Dead or worse because of me, Coyote thought, but stifled its own voice. Not now.

“Are you okay?” Coyote asked.

“Back within safety tolerances, but it’ll take a few minutes to clear everything,” said Pala. “That was amazing. Thank you.”

Coyote bowed its head and watched the dunes, wondering how far off the scouts were, how many lidar pulses were raining from orbit across the desert. A few minutes might be too much to ask, but Coyote didn’t bring it up. Instead, it smiled at Pala, showing its serrated teeth. “No problem,” it said.

___

Thanks to @flashfictionfridayofficial for the prompt, “The Sand Ocean,” and thanks to you for reading!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 10, 2022 - Stripe-crowned Spinetail (Cranioleuca pyrrhophia)

These birds in the ovenbird family are found in parts of Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina in scrubland and forests. Foraging acrobatically, alone, in pairs, or in mixed-species flocks, they feed on arthropods, including ants and beetles. They build oval-shaped nests mostly from sticks, along with some hair, feathers, and other materials.

#stripe-crowned spinetail#spinetail#ovenbird#cranioleuca pyrrhophia#bird#birds#illustration#art#water#birblr art

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iberian or Spanish sharp-ribbed newt

Pleurodeles waltl, the common or Iberian sharp-ribbed salamander, is often sold as a newt. However it belongs to a different subgroup of the salamandrid salamanders, the pleurodelins, of which it is the namesake, and is most closely related to the Asian salamander genera, Echinotriton and Tylotriton. These genera share with Pleurodeles, the defensive habit of using their own ribs, to puncture certain glands that release venom. Newts as phylogenetically defined, belong to the related subclade Molgini, none of which shares this pleurodelin habit, and none of which become as large as Pleurodeles. Pleurodeles waltl reaches a maximum length, of just over 30 centimeters, or 12 inches.

Genus Pleurodeles is indigenous to the Western Mediterranean, where it is found in stagnant freshwater microhabitats, amid xeric scrubland, dry oak woodland, and cultivated landscapes. These are habitats subject to a seasonal climate with hot summers, and the small, stagnant water bodies preferred by P. waltl, may disappear in the Mediterranean dry season. For this reason, P. waltl is thought to leave the water, only when migrating between homes. Such environments might well be man-made irrigation ditches, as easily as natural ponds. These salamanders merely seek still freshwaters, usually of a highly vegetated nature.

The other primary habitat requirement for Pleurodeles, appears to be the turbidity of the pond water. Regarding other variables, such as pH, this genus has a broad tolerance, being found where the pH is as low as 6 and as high as 9. The temperture may, temporarily, get as high as 30 degrees centigrade in the summer months, and as cool as freezing in the winter. Pleurodeles consume primarily aquatic arthropods, gastropods, and annelids, and when they are available, prey on tadpoles and other small vertebrates.

In the aquarium, Pleurodeles can be given a winter temperture of 8 or 9 degrees centigrade, though it is not necessary. During the rest of the year, or year round, these salamanders can be safely maintained at 20 to 23 degrees centigrade. Perhaps according to the locality where they or their ancestors were collected, some Pleurodeles experience heat stress when kept at tempertures, above 23 degrees. Though, it has also been noted, others do not, probably as a matter of source population. These are carnivores that are easy to feed on singing pellets or defrosted and raw foods, of appropriate nature. In the aquarium, they are fine with cohabitants, that are far too large for the newts to try and swallow.

0 notes

Photo

Taken 2022 26th April, I got to get my first good pictures of an early bumblebee (Bombus pratorum), or ängshumla, while on my course trip. In Sweden, it occurs from Skåne to the treeline within the mountains of northern Norrland wherever fields, parks, scrublands, and open woodlands are present. It's name derives from its flight period that lasts from March to July, but in milder climates, it can start as early as February. During this period, they will create a colony, which can happen two times the same year if a young queen doesn't hibernate, that include a queen and her workers. Rather than the queen using pheromones to maintain her status, she relies on her aggression. #animal #animals #djur #wildlife #insect #insects #naturliv #natur #fauna #arthropod #arthropods #insekt #insekter #invertebrate #invertebrates #bumblebees #bumblebee #bee #bees #långtungebin #insectagram #animalia #arthropoda #insecta #hymenoptera #apidae #bombus #bombuspratorum #earlybumblebee #ängshumla (at Fiskebäckskil, Västra Götalands Län, Sweden) https://www.instagram.com/p/CdcADJJKiCn/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#animal#animals#djur#wildlife#insect#insects#naturliv#natur#fauna#arthropod#arthropods#insekt#insekter#invertebrate#invertebrates#bumblebees#bumblebee#bee#bees#långtungebin#insectagram#animalia#arthropoda#insecta#hymenoptera#apidae#bombus#bombuspratorum#earlybumblebee#ängshumla

1 note

·

View note

Text

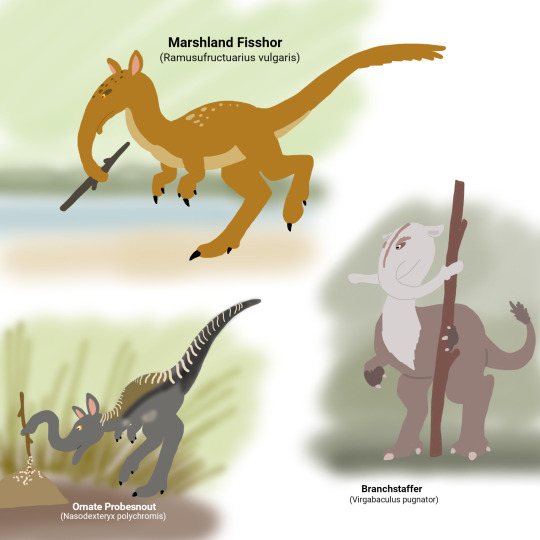

The Middle Glaciocene: 110 million years post-establishment

Fishing for Compliments: The Fisshors

The continent of Fissor had broken off during the Therocene, and later, as of the Middle Glaciocene, had once more rejoined with the mainland, into a single massive supercontinent known as Gestaltia. But this brief isolation had been enough to allow strange forms of life to evolve in the absence of other mainland species-- one of these being the tri-lobed trunked, bipedal walkabies known as the rhinocheirids.

The rhinocheirids' bizarre anatomy and adaptable omnivorous diet would allow them to continue surviving even as the land merged and intermingled with the suoercontinent, as they simply were so unlike anything else that had evolved on the mainland that they could fill still-vacant niches that others hadn't exploited. And so the rhinocheirids proceeded to thrive in a new world: as tiny, arboreal nectar-feeders, as medium-sized terrestrial foragers, and in a few species, as wading hunters of small aquatic prey.

Most remarkable of the rhinocheirids, however, are the fisshors: a group directly descended from the Therocene's browsing snoas. While obligate vegetarian snoas since have disappeared, these much-more flexible omnivores have persisted, thanks to their dexterous trunks and more complex cognitive capacity granting them an innovation previously unseen anywhere on this planet: sophisticated tool use.

Fisshors are distinguished from other rhinocheirids by their greatly elongated lower lip, which functions almost like a second trunk-- while far less dexterous, it is well able to assist the trunk in tasks that it could not do by itself. As such, these clever creatures can fashion their own tools: breaking a branch off a tree, it can then hold the branch with its boneless, yet muscular trunk, while the lower lip snaps off smaller twigs and branches to sculpt the branch into shape, crafting a customized tool from a pre-existing item in its environment.

Many of them, primarily basal species like the four-foot tall marshland fisshor (Ramusufructuarius vulgaris) would use these tools for hunting small aquatic prey, such as shrish and freshwater skwoids, which they would lure to the surface by dropping small floating objects as bait, experimenting with leaves, flowers or even dead insects to attract prey to striking range. At first, their branch tools were used like clubs, stunning prey, but a few innovative individuals that learned to make tools with a sharper end-- a proper spear, that they used for spear-fishing. Social and intelligent in nature, these few creative geniuses were quickly imitated by their peers, and in the case of mothers with young, actively taught their children, through example, how to sharpen their spears to catch themselves food.

But other, more derived species would move away from an aquatic lifestyle to search for food on land, like the ornate probesnout (Nasodexteryx polychromis), a small omnivore, barely two feet in height, living in large groups that forage on the forest floor. They have a particular taste for insects--especially hive-making arthropods like ants, termites and social beetles. Here their proficiency with tools once again comes in handy: using stones to break open mounds and then probing the mounds with sticks to collect the insects that come swarming out. Their vivid markings are unique to each individual, and probesnouts are able to recognize friends, foes and family by sight alone-- a feature that has been favored in this small, vulnerable animal so dependent on its social groups.

Indeed, with Fissor's peninsula still few in predators, save for the armadiles that occasionally target the fisshor's young, many of these species have enjoyed a relatively tranquil life in the forests and wetlands. The same, however, cannot be said for the Gestaltian mainland, prowled by zingos, marewolves, beelzeboars and the last of the large carnohams that had made one last push into Gestaltia from their last stronghold in Borealia. The plains and scrublands are a dangerous place, with fewer trees to hide, and the grassland-dwellers, pressured to adapt, would give rise to the most specialized fisshors of all: the branchstaffer (Virgabaculus pugnator).

Their proficiency for using tools to procure food would also lead to them learning to craft branches into weaponry to defend themselves from the broad array of predators out in the plains, as, at only about four feet in height and a weight of just over 70 pounds, it is by no means by itself a threat to the various local carnivores. A preferred tool are long tree limbs, broken at lengths long enough to be wielded by both the trunk and the forelimbs as additional support, with branchstaffers notable for sporting more robust arms than other contemporary rhinocheirids. Using these blunt weapons as striking tools, they can inflict serious injuries on even large predators, and often fend them off by raising their stick in the air while making a loud, reverberating unmistakable cry --somewhere between a trumpet and a howl-- that many local predators quickly associate with a meal not worth the beating. Ever innovative, territorial males are also known to use their sticks against one another: and evenly matched, it becomes almost a round of fencing, with the loser generally being whoever's stick breaks first or is lost.

Their intelligence, social behavior and capacity for constructing objects that give them a degree of control over their environment is without a doubt a tremendous milestone for life on HP-02017 as a whole: a creature that overcomes the limitations of its own anatomy by shaping their world around them to suit their needs. Indeed, if one is to consider the intellectual capacity of animals like chimpanzees and elephants to already fit the definition, the fisshors can, arguably, already be considered having crossed the threshhold of sapience. But, very soon, another species would beat them to the intellectual race and cross the threshhold far less ambiguously: one whose first contact with this budding intelligence is not fated to end in a peaceful resolution.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

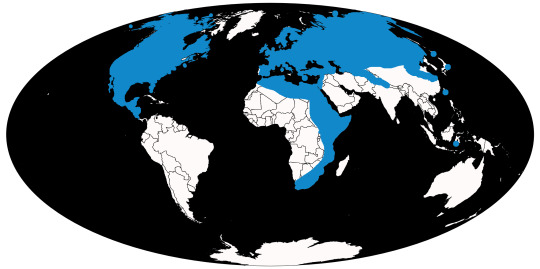

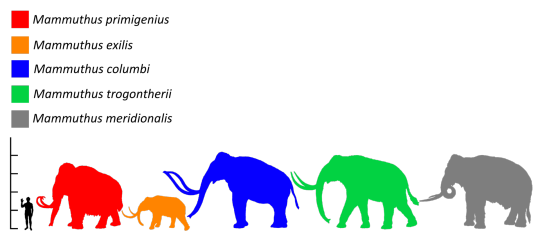

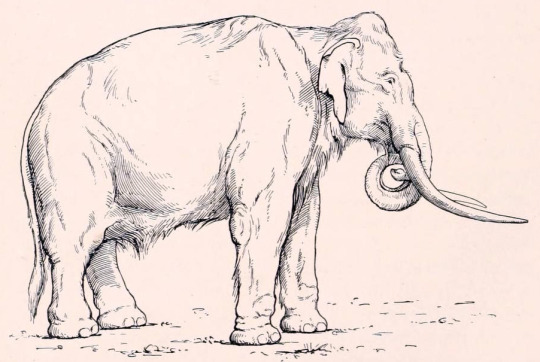

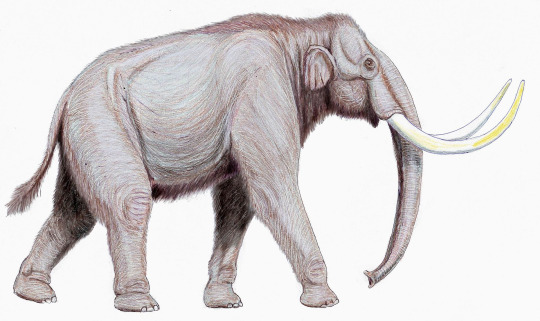

Mammuthus

South African Mammoth by Scott Reid

Etymology: Earth-Horn

First Described By: Brookes, 1828

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Synapsida, Eupelycosauria, Sphenacodontia, Sphenacodontoidea, Therapsida, Eutherapsida, Neotherapsida, Theriodontia, Eutheriodontia, Cynodontia, Epicynodontia, Eucynodontia, Probainognathia, Chiniquodontoidea, Prozostrodontia, Mammaliaformes, Mammalia, Theriiformes, Holotheria, Trechnotheria, Cladotheria, Zatheria, Tribosphenida, Theria, Eutheria, Placentalia, Atlantogenata, Afrotheria, Paenungulata, Tethytheria, Proboscidea, Elephantiformes, Elephantimorpha, Elephantida, Elephantoidea, Elephantidae, Elephantinae, Elephantini, Elephantina

Referred Species: M. africanavus (African Mammoth), M. columbi (Columbian Mammoth), M. creticus (Cretan Dwarf Mammoth), M. exilis (Pygmy Mammoth), M. lamarmorai (Sardinian Pygmy Mammoth), M. meridionalis (Southern Mammoth), M. primigenius (Woolly Mammoth), M. rumanus (Romanian Mammoth), M. subplanifrons (South African Mammoth), M. trogontherii (Steppe Mammoth)

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Mammoths have been around from 5 million years ago, until 3,700 years ago (give or take a few hundred years)

Mammoths are known from throughout North America and Afroeurasia

Physical Description: Mammoths were (mostly) large, elephanty creatures - with big bodies, long limbs, trunks, small tails, and tusks coming out of their mouths in both sexes. Most were about as large as Asian elephants, though some may have exceeded 12 tonnes. Still, there were dwarf species as well, which were quite small - some not even breaking 1000 kilograms. They grew their first tusks at the age of six months, which were then replaced at eighteen months by the permanent set. These would then grow at about 2.5 to 15.2 centimeters per year. Their teeth were distinctive - with rows of ridges that looked almost like the body of an arthropod (rather than the more flat surface seen in contemporary mastodons).

By FunkMonk, in the Public Domain

The mammoths had small ears, primarily due to the need to conserve body heat in most cases, unlike modern elephants which have larger ears with which to let off excess body heat. They had wide feet, splayed apart to help hold up their bodies. The males usually would grow larger than the females, based on the shape of the pelvis in fossils and frozen remains of these mammals. And, though a few species are very hairy - leading to the famed Woolly Mammoth - not all of them were, and many species of this genus were naked, with grey or more beige colored skin, as they lived in drier and warmer environments and needed to let off heat and sweat. Those that were hairy had thick layers of fur covering their entire bodies, even shorter tails to reduce frostbite, and thick layers of fat for keeping warm. A few species - notably, the Woolly Mammoth - had very brown, fluffy fur. Finally Mammoths, like modern elephants, were extremely intelligent animals, and had the brain and head size to match.

Woolly Mammoth by Mauricio Antón, CC BY 2.5

Diet: Mammoth diet varied from species to species and location to location of mammoths, though they were, overall, herbivores. Some mainly grazed on things like cacti leaves, trees, and shrubs; others, herbs, grasses, and shrubs; still more, forbs, rather than grass. Sometimes, babies that were no longer drinking milk would eat the poop of adults, like modern elephants, as they could not chew properly on plant material yet. This would also lead to feeding on fungi associated with poop, in addition to the plant material present.

Behavior: Mammoths were, in general, herding animals, much like modern elephants - in fact, it is theorized that they probably had social structures very similar to their living relatives. They had females living in herds, headed by a matriarch, that was the source of wisdom for the whole heard; meanwhile, the males would live alone or form loose groups of convenience when the situation arose. These herds would, oftentimes, migrate from region to region based on weather patterns and seasonal change. They could form herds of thousands of individuals of a variety of ages, with the adorable image of juveniles and young running to keep up with the strides of the much larger adults.

Woolly Mammoth by Flying Puffin, CC BY-SA 2.0

Mammoths, like modern elephants, mainly interacted with their environments with their trunks, which were essentially fifth limbs for these animals. They grabbed objects in their environments and talked to each other through the movement of their trunks. The trunks were also used for grabbing food in a lot of situations, pulling up coarse tundra grass and other food items and brought to the mouth, where it would then be chewed with the trough, specialized teeth. They used their tusks for defense from predators, though this wasn’t very helpful for the juveniles, who did not have extensive tusks. The mammoths also fought each other with their tusks, especially males, who would interlock the tusks and even break them while fighting for mates. They could also use the tusks to strip off bark and gather up food, even by digging in the dirt for food.

Ecosystem: Mammoths lived in a wide variety of habitats overall, though of course these differed from species to species. They lived across savanna and desert, steppe and tundra, grassland and scrubland, and even in sparse forest and higher elevations. As for predators, Mammoths were heavily at risk from predators such as lions, sabre-toothed cats, various types of wolves and other dogs, and of course, humans - which are probably the reason Mammoths are extinct today.

Cave Art from PalaeoAmerica, in the Public Domain, depicting two Columbian Mammoths (with a bison drawn over the right one)

Kapova Cave, in the Public Domain

Other: How did Mammoths go extinct? Apart from earlier species, the answer seems to be a combination of climate change and human activity. Multiple species - especially the Columbian and Woolly Mammoths - are known to have been hunted by humans, and cave drawings depict this activity for both of these species. This combination had a terrible effect on all species of mammoths - rising sea levels, with wildfires, and human hunting lead to the extinction of the Pygmy Mammoth, despite not being as large and specialized as those more iconic, giant species of mammoths elsewhere. Habitat shrinkage did not help with Mammoth populations; but human activity definitely contributed, as many populations of mammoth were heavily impacted by human activity. Prior to this, there was extensive genomic meltdown, as DNA diversity went into heavy decline for the past few thousand years. Isolated populations of mammoths - such as those on islands - showed the most extreme decline as the climate changed and humans became more common. The final death knell came from population fragmentation - with mammoths no longer having overlapping ranges, isolated populations were more susceptible to these rapid changes, and each subsequently went extinct due to climate change and human activity (with different causes being more or less important depending on the population in question).

Steppe Mammoth by Titus 322, in the Public Domain

Species Differences: There are 10 species of mammoth, each very distinct from the others, and each occupying unique environments and locations. Some are older than the others, as well.

The oldest species, M. subplanifrons, or the South African Mammoth, appeared about 5 million years ago - at the very beginning of the Pliocene. It spread from South Africa to the East African region, where it became most common in Ethiopia (funnily enough, the same time and location as human evolution, really). They were very similar to later mammoths, having spirally twisting tusks and large size - weighing up to 9 tonnes. They went extinct within the Early Pliocene and, given that they lived in Africa, were probably not very hairy as far as mammoths go; living mainly on savannas and other habitats that we see modern African Elephants on today.

African Mammoth by Apokryltaros, CC BY 2.5

The second oldest species, M. africanavus, the African Mammoths, lived from the Late Pliocene (about 3 million years ago) through the earliest part of the Pleistocene, about 1.65 million years ago. These two early species in Africa point to an African origin for the Mammoths. It has been found in Chad, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia - showing the northern migration of Mammoths in their early evolution. They had very widely diverging tusks, much more so than other mammoths.

The next in the group, M. rumanus, the Romanian Mammoth, is one of our earliest examples of a Mammoth that spread to Europe - having been found in the late Pliocene of the UK and Romania. Being a very short lived and poorly known species, it is difficult to know much about it, though it does point to Mammoths migrating out of Africa through the Levant region, up to Eurasia from there. It’s possible that the Romanian Mammoth helps to show more about the dispersal of this genus through Eurasia as the Ice Age began in the Pleistocene.

Southern Mammoth by Erwin S. Christman, in the Public DOmain

The Southern Mammoth, M. meridionalis, lived from the end of the Pliocene through the beginnings of the Pleistocene, and is known from Europe through Central Asia. It is known from many remains, which pinpoint that it may have been very closely related to the African Mammoth, though currently it is hypothesized that the South African Mammoth was the ancestor of all other forms. The Southern Mammoth grew to be about 4 meters tall and weighed 10 tonnes, making it one of the largest of the group. It had very robust, twisted tusks like other mammoths. It lived, generally, during a more mild time of the Ice Age, feeding mainly on deciduous trees and living in grassy, open habitats with small groves here and there. It was a browser, feeding mainly on higher level foliage.

Steppe Mammoth by Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY 3.0

All other Mammoths lived from the Pleistocene on, with some making it into the Holocene (and subsequently going extinct during the Pleistocene-Holocene Megafaunal Extinctions). The Steppe Mammoth is the next in our temporal sequence, M. trogontherii, known from Siberia in the middle of the Pleistocene - the first stage in the evolution of steppe and tundra mammoths during the glacial periods of the time. It probably had fur on most of its body - shorter than that of the Woolly Mammoth, but not by much. It had a short skull and small jaw compared to other mammoths, and the males had tusks with tips that could grow extra long and curved. They grew up to 4 meters tall and around 10 tonnes in weight. It is known mainly from fossilized teeth, with skeletons being rare, though some complete skeletons have been excavated in northern parts of the UK and siberia. It probably ate mainly shrub plants and tundra forbs.

Columbian Mammoth by Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 4.0

The next species of Mammoth to evolve was the famed Columbian Mammoth, of the mid Pleistocene through Early Holocene of North America. Though it’s range was next to that of the Woolly Mammoth, they clearly divided North America between the two, with Woolly taking the northern half of the continent, and the Columbian mammoth taking the southern half. The Columbian Mammoth is known from a lot of fossils, across a variety of localities, and show the initial spread into North America by mammoths in an earlier in-between period of the Ice Age than the expansion of Woolly Mammoths later. It evolved from the Steppe Mammoth, which migrated across the Bering Strait into North America, down corridors available between glaciers through to the bulk of the area that would be the continental United States. The Columbian Mammoth grew to 4 meters in height and 10 tonnes in weight, making it larger than the Woolly Mammoth and the African Elephant. It also had fairly primitive teeth compared to other mammoths. It had tusks directed farther apart than those of other mammoths, and it had a longer tail. Since it lived in warmer habitats, it lacked a lot of the adaptations for the cold, and probably didn’t have much in the way of hair for keeping warm. Its tusks were excessively long, especially compared to modern elephants.

Many Columbian Mammoths are found in Elephant Graveyard fossil deposits, indicating areas where the bones of individuals would accumulate due to the movement of water. Additionally, many fossil remains are found in tar pit accumulations, in addition to sinkholes and other natural traps. Most fossils found in these sites are actually males, which were more likely to put themselves in danger than the females - lured to these holes by warm water and vegetation at the edges. These elephants would have needed to spend most of their day foraging, using their trunks to pull up grass, flowers, and other types of food. It’s possible that these mammoths could have reached even 80 years in age, growing for most of their lives.

Columbian Mammoth by Charles R. Knight, in the Public Domain

The Cretan Dwarf Mammoth, M. creticus, is one of three diminished species of Mammoths, known from about 700,000 years ago on the island of Crete in the Mediterranean. These mammoths were very small, reaching only 1 meter tall and weighing only 310 kilograms - making it the smallest of the mammoths. It is possible that this animal wasn’t a mammoth at all, but another type of proboscidean; studies are still out on that one. Skulls of this animal may have formed the basis for the Grecian myth of the Cyclops!

The Sardinian Pygmy Mammoth, M. lamarmorai, was another species of small mammoth which evolved about 450,000 years ago, and is known only from the island of Sardinia. It grew about 1.4 meters tall and weighed up to 550 kilograms. It is known from many fossils, but no complete skeletons, mainly along the west coast. It is actually very uncertain what sort of mammoth this species originated from; it seems possible that the Steppe Mammoth colonized Sardinia, and then experienced Island Dwarfism as it was isolated on the island during an in-between period.

Woolly Mammoth by Honymand, CC BY-SA 4.0

The second to last species of Mammoth to evolve is, indeed, the best known of them all - M. primigenius, the Woolly Mammoth. Woolly Mammoths lived around the Arctic circle, in northern Eurasia and North America. Evolving from the Steppe Mammoth sometime between 400,000 and 150,000 years ago, it lived all the way up until the recent past, about 4,000 years ago - leading to the common fun fact that the Pyramids were built while Mammoths were still alive! Given it’s late position in the fossil record and extreme numbers during the last ice age, we have so many fossils and frozen remains of this animal that we know much of its life history (and the Woolly Mammoth remains one of the most controversial examples of something we might actually bring back through de-extinction). Because of this abundance of remains, we know a lot about its life appearance and life history - in fact, it’s the prehistoric animal with the best known appearance.

Woolly Mammoths were - as the name suggests - woolly, covered in layers of fur all over their bodies which was brown in color, as well as very thick layers of fat, very small ears and short tails, and flaps of skin covering orifices to keep them warm. The mammoths had oil glands in their skin, which secreted into their hair and helped the hair in repelling water, and gave the hair a glossy sheen. There was long, coarse guard hair on the outer layer, covering curly under-wool underneath. Interestingly enough, the Woolly Mammoth also had some weird physical characteristics not related to the warmth, such as a very high, domed head, and a sloping back with a shoulder hump. These were more present in adults, and not visible in juveniles. Their tusks were asymmetrical and extremely varied, and weirdly enough, most of the length of the tusks was inside the mouth. They had four molars at a time, used for chewing very tough vegetation.

Woolly Mammoths by Kira Sokolvskaia, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Woolly Mammoth was the most specialized elephant to ever live, with extreme amounts of fat stored for warmth and when food was unavailable; their molars grew more quickly than in modern elephants; and their fur was so thick it was as though they wore mittens all over their bodies. They had differences in circadian rhythm clocks from living elephants in order to deal with extreme variation in daylight levels, and its proteins were less sensitive to heat. They had about 1.4 million differences in DNA compared to their closest living relatives, the Asian Elephants. They fed mainly on herbs, small flowering plants, shrubs, and mosses, and even fungus and poop from each other - not just the young, but the adults would do this too in times of food scarcity. They probably could reach up to 60 years of age, and they grew past adulthood - like living elephants.

The males also would go into musth - a period of extreme aggressiveness - during the breeding season, like living elephants today. They produced oil with glands that moved a smell associated with musth all over their fur, signaling to female mammoths they were ready to go, and to male mammoths to leave them alone. The breeding season was typically in the summer through the beginning of fall. The mammoths gave birth during the spring and summer, after a gestation period of nearly two years. While many reached older age and adulthood, bone disease was a very common cause of death for these mammals, as well as parasitic animals and infections after poorly healed injuries. Still, many were murdered by humans, and mammoth bits are used heavily in human society - for food, warmth, and art, with ivory from mammoths used in sculptures by early humans.

Pygmy Mammoth by Apokryltaros, CC BY 2.5

Finally, Pygmy Mammoths - M. exilis - were the last species to evolve, evolving approximately 60,000 years ago; still, it didn’t live as long as the Woolly Mammoth, dying out about 11,000 years ago, right at the beginning of the Holocene. The third case of insular dwarfism in the Mammoths, it grew to about 1.72 meters tall at the shoulders and 760 kilograms in weight. It evolved from the giant Columbian Mammoth, as well, making this all the more impressive. It is known from the Channel Islands along California, where Columbian Mammoths presumably reached via land bridges during some glacial period of the Ice Age. Possibly, they also swam there in search of food and escaping the large predators of the mainland such as Smilodon and the American Lion. It thrived across a variety of ecosystems, including plateaus, dunes, grasslands, forests, and even steppe-tundras.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammoth

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_mammoth

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbian_mammoth

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammuthus_creticus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pygmy_mammoth

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammuthus_lamarmorai

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammuthus_meridionalis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woolly_mammoth

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammuthus_rumanus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammuthus_subplanifrons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steppe_mammoth

#Mammuthus#Mammoth#Woolly Mammoth#Not a Dinosaur#Mammal#April Fool's#Prehistoric Life#Prehisotry#Paleontology#North America#Eurasia#Africa#Neogene#Quaternary#Herbivore#Ice Age#prehistory#biology#science#nature#factfile

861 notes

·

View notes

Text

143 - Pioneer Days

We are thirsty. We cannot see.

We don’t know what time it is, we are nearly here.

Welcome to Night Vale.

Pioneer Days are upon us again. This is, of course, just the folksy rebranding that the public utilities department gives to randomly selected days throughout the year, when they cut all services without notice. The lights go out, the air conditioners grow warm, the food spoils, the water supply dries up. All residents are required to dress in the costumes of early settlers to make the whole thing feel festive and patriotic. Failure to dress in era-appropriate clothing, such as overalls and soft meat crowns, will result in punitive measures. Including being called a time traveler in a pejorative tone of voice, as was traditional punishment for all real time travelers back in the early days of Night Vale.

Polls show that these civic holidays are increasingly unpopular, but this time it’s going to be different, the utilities department promises. “It’s going to be way more fun, we swear. Just bear with us, you’re so brave. You’re all my brave little pioneers,” the pamphlets scattered around town assure us. “After all,” the pamphlets continue, “what is bravery but endurance? What better way to honor the struggles of our ancestors than through personal discomfort and grim acceptance? These are the values our town was founded on, aren’t they? Aren’t they?!” the pamphlets shout. The pamphlets writhe on the ground. The pamphlets inhale sharply and become still. In an effort to sway public opinion on pioneer days, the utilities department has unveiled an interpretive boardwalk and historical display, set up in an open expanse of desert miles from town. The intention of the display is to bring a sense of local pride and education to the community, and to be a fun family centered activity that can take people’s minds off the panic inducing existential questions that come from being so very alone in the dark.

And now traffic. You had a dream when you were young. In the dream, you woke up on the couch after a nap just in time to see your family driving away, leaving you alone in the house. They’ve never done that before, you’re much too young, too small to be left alone. There are no lights on and everything is soft with shadows. You see a brown paper bag on the table. They must have left it there for you. Is it food? You don’t know how to feed yourself yet. The bag suddenly lurches and tips over onto its side all by itself. A snake slides out onto the table, drops to the floor, and slithers rapidly toward you. You try to scream.

This is the moment you were supposed to wake up, but it isn’t a dream, is it? Your whole family really did abandon you. You grew up in this house alone after that, just you and the snake. It wasn’t poisonous but that doesn’t mean it was a good companion. It came and went without consideration for you at all, sunning itself on rocks or squeezing rodents to the death whenever it pleased, sometimes not coming home for days. You cleaned up its discarded skins during the molting season. You let it sleep curled next to your body for warmth in the winter months, even though it could only give back cold indifference in return. But you had no one else, that’s just how it was. You still see each other once a year during the holidays out of a sense of duty. You follow each other on Facebook, but neither of you check that site anymore.

You waited to wake up from this dream of your youth to find your family had never left, that they were still there with you. You are still waiting to wake from this dream.

This has been traffic.

I’m getting more details about the Pioneer Day’s display and celebration. Along the interpretive boardwalk, visitors will come to several viewing platforms where they will see the bleached bones of select citizens’ ancestors, scattered across the sun scorched earth. Those who won last night’s raffle must remit their ancestral bones by noon in order to be featured in the display. Further along the walk, spectators will be treated to an animatronic re-enactment of the battle for the scrublands, an event in which several key town founders bravely fought against the giant benevolent arthropods that used to exist in this area. As visitors will see, the beasts were all slain easily by our intrepid settlers, as the animals were unaccustomed to violence of any kind and regarded the human newcomers with only gentle curiosity.

“They had to die,” intones the robotic voice of a mechanical man in a waistcoat, as he stands triumphant among piles of enormous multi-pointed legs. “For they were too visually disconcerting to live,” he booms.

There will always be a booth sponsored by the historical society displaying repurposed slide film from random strangers’ family vacations that have ben collected at garage sales over the years. Accompanied by plaques with made up historical narratives about the pictures. For example, there’s one of an elderly woman playing shuffleboard on a seniors’ cruise entitled “Griselda Fords the River”. It tells the tale of when pioneers first got to the sand wastes and there was a big scary river running through it, and how they had to risk their lives just to reach the land that we now have the privilege to take for granted. A lot of plaques have a kind of passive aggressive tone like that, actually.

If you make it to the end of the walk, you will be greeted by Earl Harlan, who will demonstrate how to make cherries jubilee, a staple dish among the early Night Vale frontiers people. “You feed a goose cherries until it can no longer walk or stand on its own,” Earl explains. “Then you light the goose on fire until its screams become whimpers, and when it’s finally silent, you extinguish the flames. The goose’s blackened flesh is full with tar enzymes that are very good for your skin and eyes. The red liquid pooling around it is only cherry juice. Only viscous cherry juice,” he explains as he dishes out samples of the boiling native cuisine directly into people’s outstretched ravenous hands.

That’s not all. The fully immersive interactive theater segment is last. You’ll be blindfolded and placed in the back of a cargo truck. Hours later, you will step off of the wooden blank and be free to enter into the desert, to try and find your way back home. Just like the pioneers did it. You don’t realize how the boardwalk is designed to be completely disorienting until this moment, when you step into the endless desert and look to all horizons and see only identical sagebrush and chaparral and nothingness. As if you’ve entered a mirrored fun house made only of hot dirt.

More on Pioneer Days, but first

The weather.

[“Vines” by Super Boink

https://superboink.bandcamp.com/]

As you wander lost in the desert, you first experience a dizzying sense of freedom. You can go wherever you want, the future is yours to shape. The possibilities seem as endless as the vast wasteland in front of you, but when you look behind you and realize you can no longer see the interpretive boardwalk or any other sign of human life, that sense of freedom becomes abject despair. You realize that taking risks is only fun when you have safety net. When that risk is a choice. Now that you’ve been swallowed up into the blistering wilderness, you learn that choice has always been an illusion. You must go forward. The sun sinks lower. The dark air blurs the edges. You feel a cool breeze sweep over the sand – and you are grateful for that. Your lips bleed.

It’s nightfall when you come to an old homestead. It has no roof and leans to one side. There is no door, but there is the shape of a door, the black rectangle of absence. You feel compelled to go in, as would anyone confronted by a structure with an entrance, but you hesitate. You recognize this place, yes. You saw it in the slide film display by the historical society. There was a picture of it taken many years ago. It depicted the same house, only it had a roof back then. It did not lean to one side, and two children, barely toddlers, were standing out front. They had no heads, they had chickens roosting on top of their necks instead. The accompanying explanation said that it was a double exposure, a photographic art form that early Night Vale settlers dabbled in to pass the time. There was a whole collection of these photos displayed: a bath tub filled with blood. A levitating skull on fire. A baked ham with long luxurious hair.

“The first Night Valers were incredibly adept at trick camera work,” the historical society insisted nervously when questioned. “Cameras had come to town at least a hundred years before cameras were invented, due to the rampant time traveler problem back in those days,” they explained.

“We found the pictures in a locked trunk buried near the railroad tracks,” blurted a younger historical society member who was immediately shushed by the elders and relegated to selling merch.

You hesitate in the yard, until you can no longer ignore the siren song of the wind through the broken bones of this place, screaming at you to enter. Inside, the only piece of furniture left standing is a kitchen table. On top sits a sealed jar packed to the brim with pickled eggs. Your child asks if she can have one. Your child is with you, she’s ben riding on your back the whole time and you forgot all about her. That’s incredibly alarming. How can a parent just forget their own child like that?

“Yes, honey,” you say, trembling with the effort of keeping your voice calm. “You can have one.”

You set her down and she scampers across the dusty boards, and she feeds. She feeds ravenously. She asks for a bedtime story next, it is her bedtime after all. At least she says it is. You don’t know what time it is, but somehow she senses it and you trust her instincts. Habits are comforting, rituals are important. It’s what keeps us grounded. It’s what prevents us from shouting uncontrollably and clutching at our eyes.

“Once upon a time, there was a child who looked very much like you,” you begin.

“No,” she interrupts, “the child looks like you.”

“It doesn’t matter,” you say, “because it was actually a dog, not a child, be quiet now. Here’s the story. A dog ran away from home and had many adventures and then returned to its family and everyone learned lessons.”

“What kind of adventures?” she asks.

“Unspeakable adventures,” you say.

“Is this a true story?” she asks.

“Every story is true,” you say.

She’s still awake. You point through the roofless void and tell her to count the stars, hoping to bore her into unconsciousness.

“There are no stars,” she says. You acknowledge that the thick dark air obscures any light that might be in the sky, but “we can see them anyway,” you tell her, “because we know the stars exist.”

“How do we know?” she asks.

“Go to sleep,” you say.

After she’s asleep, you walk through what’s left of the old house and wonder if this is your new home now. There are many things you think you see standing in doorways or huddled in corners. Luckily, most of them are not real. The only thing that’s truly there is a nest of baby arthropods, bedded down in the tattered remains of a blood stained prairie dress. They appear to be orphaned, but they are together, intertwining all of their legs and blinking all of their eyes and wriggling as one large familial mass. You know you don’t belong here. This is their home now, as it was their home before, long before there was ever a house. You lift your child’s sleeping body and enter the desert once more. You look behind you and see the silhouette of a chicken-headed toddler standing sentinel in the yard. It’s not real, it’s just a double exposure.

As light lifts itself above the horizon, something shiny catches your eye in the distance. You move towards it, because it’s the only thing to move towards. You don’t feel hope or motivation, only the pull of a random focal point that keeps you going forward. Eventually you come upon an enormous parking lot full of vintage cars. Some are early models made of skin and mud and some are mid-century coupes with fins and hardtops and spinal columns. Hundreds of chrome bumpers glare in the blinding half-sun of dawn. What’s all this? you wonder in the daze.

“Hear yee, hear yee!” shrieks an individual in a tricorn hat, ringing a handbell.

“What is this?!” you shriek back, grabbing them by the lapels. They do not acknowledge you.

“Hear yee!” they cry again, but do not elaborate further.

Suddenly the pounding of drums and deafening squawk of brass, a marching band is playing. Colorful streamers trail through a clear blue sky. It’s the city parade. You made it to the end of the Pioneer Days interpretive display and celebration! You accept another liquid handful of scalding cherries and stumble home with your drowsy young still clinging to your back.

As you enter your own silent house, completely free of all public utilities in celebration of Pioneer Days, you are overpowered by the scent of rotting kale in the stuffy air. And you breathe it in deeply. You rejoice. You weep. The only source of water is the puddle on the kitchen door, fed by the constant drip of the defrosting freezer. And you kneel down and drink from it, until you are satiated.

Things don’t look as bad as they once did, do they? The walls aren’t closing in on you anymore, they embrace you. The dark screens of your electronic devices no longer reflect your own boredom back to you, they reflect only relief on your haunted face. The inconvenience of no public services pales in comparison to the night you spent merely surviving in a howling unstable universe. It’s all about context. It’s all about managing your expectations. That’s what the utilities department pamphlet was trying to tell us all along.

And of course about celebrating the Pioneers spirit, something something forefathers, vintage cars and other stuff like that.

But now that I think of it, we do spend a lot of our days distracting ourselves from physical reality. Maybe we really can use this time to experience life more solidly in the physical world, the way our ancestors did. Who needs modern conveniences when we have each other, right? Hold your loved ones close tonight. After all, you have nothing better to do.

I’m coming home now, Carlos. I know you can’t hear me. No one can hear me. The power’s out here in the station just like it is everywhere else. We haven’t been broadcasting anything for days now. And even if we had bee, your radios don’t work anyway. but habits are comforting. Ritual is important.

Stay turned next for – whatever you think you hear.

Good night,

Night Vale,

Good night.

Today’s proverb: The leading cause of death is having a body.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taxxon: thoughts & theories

Biology/Culture

- Adults average 10 ft long and have a diameter of about 35 ins (the size of a couch in width)

- Have crops as well as multiple stomachs. Can store things in their crops that they either plan to digest or just want to hold onto and have all their hands free.

- Are eusocial and hermaphrodites. Generally the only breeding taxxons are the hive founders who tend to grow much larger than their children and do not leave the hive once there are enough workers to care for them.

-Hatch from eggs. Have nymph stages, the nymphs resemble the adults but with fewer body segments and proportionally fewer limbs.

Spawning taxxons lay hundreds of thousands of eggs. The young then feed mostly on each other and what rations the adults bring them as they mature enough to leave the brood chambers. Generally only a few hundred make it to this stage. Afterwards they are educated by nannies.

Young taxxons generally avoid nonrelated adults who might eat them.

-Mostly subterranean and semiaquatic, and have better night vision than day vision.

Red is a color associated with safety.

-New hives are started by individuals who decide to leave their homes and meet up with a handful of unrelated taxxons all carrying pieces of their living hives with them to plant in their new home.

- Have tissues that are resistant to acid burns and a hydrophobic exoskeleton.

- Easily regenerate lost limbs in hours.

-Have no sense of personal space

- Teeth are metallic and easily replaced through out the taxxon's life

-Taxxon have an incredible sense of smell. Able to track wounded prey from miles away. Taxxon hunting parties will pursue something for days or weeks on end.

Taxxon bites very easily and very quickly fester if left untreated.

- Taxxon langues comprises of both scent (long term public messages) and sound (short term immediate messages)

Taxxon speech comprises of mostly hissing and the clicking of teeth and claws.

Taxxon have two names, a personal scent (everyone knows who they are and where they've been) and a sound identifiers (something for them to be called by others).

The Living Hive

-Is a sapient psychic fungus that lives in a generally mutualistic relationship with taxon hives.

In times of drought and famine the relationship can become parasitic with the living hive consuming eggs and living taxxons. Some taxxons decide that they are better off abandoning their hives when this happens.

- By working with the taxxons the living hive gets food in the form of taxon waste products, shed exoskeletons, and what dead the taxxons themselves don't wish to eat; the living hives are no longer able to produce nonclone offspring without taxon intervention; taxxons protect the living hives from things that would eat it.

- what taxxons get out of the deal is: a place to lay their eggs that stays clean and prevents bacterial infections; food in the form of fruits and fungal secretions that contain vitamins that they cannot produce themselves or get out of their diet, whout these they go through something very close to 'rabbit starvation' and their exoskeletons become thin and easily ruptured; reduces the energy cost of long distance travel; early warning system; a comforting outside presence that makes living with several thousands of your siblings easier.

Food

- Taxxons are carnivores who either scavenge large prey or actively hunt small prey. Their diets are supplemented by fruit and secretions (lets call it milk) from the living hive.

- Taxxons eat their dead and badly wounded (nonstarving taxxons will kill whoever they are going to eat before going to town on them). Baby taxxons eat eachother until their large enough to do their own hunting (also helps reduce potential overcrowding and over hunting problems). Taxxons eat enemy taxxons trying to steal their prey and territory.

Cannibalism is normal. Eating the dead is respectful. Eating brood siblings is a rite of passage and just plain practical. Eating those too badly wounded to recover is an act of mercy. Eating enemies is common sense.

-Autocannibalism is only seen in starving taxxons as is the phenomenon of eating themselves to death. Healthy taxxons are unlikely to consume so much that they cause their organs to rupture nor would they consider themselves food.

Homeworld

-The dominant forms of life are arthropod and worm like.

-Landmasses on the taxxon homeworld are dominated by deserts and mountains and arid scrubland. Towards the equator there are some dry forests.

Preferred prey of large herbivores travel in herds following the rainy season and fresh vegetation.

- Water on the taxxon homeworld is all acid. Most of the drinkable stuff is either in inland underground aquifers or falling from the sky. The ocean is dangerous and to be avoided.

-The acid in the air corrodes metals over time, making metal tools other than loose teeth an exercise in wasting time.

The Yeerk Empire

- Starving bands of desert taxxons who abandoned their hungry living hives agreed to work for the strange alien invaders promising food for everyone.

- better fed taxxons from other areas see this and understand that it is a terrible idea and fight the aliens.

- Turns out having a mind control slug doesn't stop the feeling of starving b/c the food provided by the aliens lacks the vatamins that they need. Is even worse that the yeerks tend to work themselves to starvation so towards the end of a cycle things are compounding for the worse.

- The living hives refuse to cooperate with the yeerks leading to the taxxon hosts not really being able to breed properly or receive the nutrients that they need without theft and raiding.

- rebellious sentiment spreads through taxxon hosts who plan to revolt against the yeerks. Some, who have tremendous levels of fortitude and self control, smuggle pieces of living hive in their crops to seed future rebel bases.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata)

The yellow mongoose is a member of the mongoose family averaging about 1/2 kg in weight and about 500 mm in length. It lives in open country, from semi-desert scrubland to grasslands in Angola, Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. The yellow mongoose is carnivorous, consuming mostly arthropods but also other small mammals, lizards, snakes and eggs of all kinds.The yellow mongoose is primarily diurnal, though nocturnal activity has been observed. Living in colonies of up to 20 individuals in a permanent underground burrow complex, the yellow mongoose will often co-exist with Cape ground squirrels or suricates and share maintenance of the warren, adding new tunnels and burrows as necessary.

photo credits: wiki

#yellow mongoose#Cynictis penicillata#mongoose#zoology#biology#biodiversity#science#wildlife#nature#animals#cool critters

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roll Up with the Sacred Scarab

The sacred scarab (Scarabaeus sacer) is perhaps the most famous of all dung beetles as a symbol of worship by ancient Egyptians. Outside its godly role, this species can be found throughout northern Africa, as well as southern Europe and into western Asia as far as India. In Africa it inhabits both deserts and scrubland, as well as agricultural areas where food is abundant, while in Europe the sacred scarab stays more towards the coast in dunes and marshes.

Aside from its well-known association with religion, the sacred scarab is known best for its association with dung. When a source has been found, individuals roll it into tightly compressed balls known as telecoprids, which can weigh up to ten times their size. These telecoprids are then rolled with the hind legs to an underground chamber where S. sacer strains out and feeds on nutrient-rich fluids, molds, and undigested particles from the ball over several days. In addition to its role as a nutrient recycler, the sacred scarab is also an important source of food for many small mammals, reptiles, and birds.

In its native range, the sacred scarab will mate year-round provided food is abdunant. Males and females work together to form and move a dung ball back to the underground nest; it is during this stage that males will fight each other for control of the ball, while the female will simply follow wherever the telecoprid goes. Once in the next, male and female briefly copulate before the male departs to search for another mate. The female then sculpts the dung ball into a pear shape and lays a single egg in the narrower end, which is then sealed. Her job done, she too leaves to seek out another partner and repeat the process, laying over a dozen eggs in her lifetime.

After a week or two, a single larva emerges from the egg and begins feeding on the dung around it. Over the next 3 months, it will molt up to three times before forming a pupa. About a month later, a fully mature adult emerges and burrows its way to the surface to find a fresh source of food and potential mates. Unlike many beetle species, the sacred scarab is an adept flyer, and will often use its wings to travel between food sources as opposed to walking.

Though the sacred scarab may seem ornate in Egyptian hieroglyphics and jewelry, the species itself is quite plain. Individuals are completely black, and both sexes are indistinguishable from each other. Individuals can range from 1.9 to 4.0 cm (0.7 to 1.6 in) long, and weigh up to 2 g (0.07 oz). One interesting feature is their front feet; unlike other dung beetles, S. sacer doesn't have any. Instead they only have a vestigial claw-like structure that can be used for digging.

Conservation status: This species has not been evaluated by the IUCN, but due to its large population size and adaptability to urban and agricultural expanstion it is considered relatively stable.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Amadej Trnkoczy

Kev Gregory

San Diego Zoo

#sacred scarab#Coleoptera#Scarabaeidae#scarab beetles#beetles#insects#arthropods#deserts#desert arthropods#scrubland#scrubland arthropods#wetlands#wetland arthropods#urban fauna#urban arthropods#africa#north africa#europe#southern europe#middle east#asia#west asia#animal facts#biology#zoology

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tiniest owl in the world vs a color-assorted favorite!

Elf owls are the smallest owls in the world, about the size of a sparrow, with a wingspan of about 27 cm (10.5 in) and weighing about 40 g (1.4 oz). They live in deserts, dry scrublands, and open forests from the southwestern US through Mexico. They mostly feed on arthropods such as beetles, moths, crickets, and scorpions. They nest in cavities in saguaro cacti abandoned by woodpeckers.

Eastern screech owls live in eastern North America wherever trees can be found, even in backyards. They occur in two color morphs, gray and red, which blend in well with different types of trees. These owls mostly eat small rodents and large insects. When defending the nest, females will even attack humans.

10 notes

·

View notes

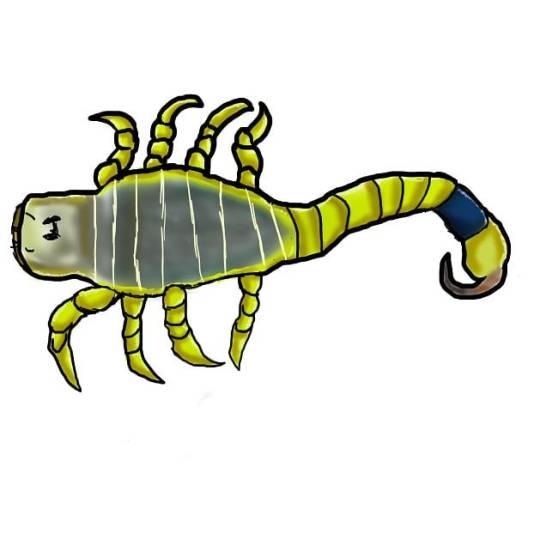

Photo

Arthropod Common Name: Deathstalker Arthropod Scientific Name: Leirus quinquestriatus Order: Scorpiones Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Chelicerata Physical Features: segmented body with 4 legs on each side, modified front legs that form pinchers, have fangs (chelicera) all scorpions have 2 eyes on the top of the head and often 2 to 5 pairs of eyes on the front corners of their head.deathstalkers are primarily yellowish in color with brown spots. Size: 1.1 - 3 inches in length average size is around 2.2 inches. Maximum weight is 2.5 grams. Habitat: semi arid - arid desert and scrubland. Found throughout the Middle East and North Africa. They will use rocks and other animal burrows to hide in. The deathstalker will also build their own burrows about 20 cm below rock. Food: insects such as earthworms,and other scorpions cannibalism is common among this species. Predators: Other arthropods and scorpions. Lizards and birds will also eat the deathstalker Reproduction: a male will “court” a female by performing a dance, the male positions the female and the two scorpions reproduce. Deathstalkers lay between 35 and 87 eggs, after 122 to 227 days the eggs hatch. The specific parenting habits of the Deathstalker aren’t well known. However in similar species the young scorpions climb onto the female’s back and remain there for around a year. Interesting Facts: Average lifespan is 4 - 25 years. Deathstalkers are common as pets and commonly found in underground pet trades. The deathstalker’s venom is incredibly potent and can cause respiratory failure. Their venom has been researched for diabetes and cancer treatments. Deathstalkers act as a bioindicator species. They communicate using touch and can sense vibrations by using special sensory organs on the bottoms of their feet. Sorry for the paragraph. I drew this and researched the deathstalker for a project in zoology. They're pretty interesting little things. #biology #biomajor #zoologystudent #art #illustration #artistsoninstagram #digitalart #wacom #medibangpaintpro #scorpions #scorpionsofinstagram https://www.instagram.com/p/Bv0Qd97BSth/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=pwdh4iw7x7au

#biology#biomajor#zoologystudent#art#illustration#artistsoninstagram#digitalart#wacom#medibangpaintpro#scorpions#scorpionsofinstagram

0 notes

Text

March 17, 2022 - Purple-banded Sunbird (Cinnyris bifasciatus)

These sunbirds are found in woodlands, scrublands, and savannas across parts of central and southern Africa. They primarily feed on nectar, along with some small arthropods. Females build pear-shaped nests from leaf stalks, lichen, spiderwebs, and sometimes grass, leaves, and plant fibers, with long tails hanging from the base decorated with wood chips, lichen, and other materials. While females incubate the eggs alone, both parents feed the chicks.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

A guide to the tick species every American should know

Long Star ticks are generally found in the West, but they've recently made the jump to the East Coast, too. (NIAID/)

This story originally featured on Outdoor Life.

Our love of the outdoors can bring us into contact will all sorts of unpleasant organisms, though few are as widespread as the tick. These vampiric arachnids can be found across the globe, and many are responsible for transmitting disease. Ticks have been documented transmitting a wide range of protozoan, bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens to humans, pets, and livestock. And while there are roughly 80 different tick species that can be found in the continental US (and more than 800 found worldwide), there are 10 species that really stand out. With tick season right around the corner in most areas, we hope this tick-identification gallery will help you limit your risk and teach you a little more about these complex and creepy creatures.

The different stages of a tick. (CDC/)

The life of a tick

Despite our occasional suspicions that ticks only crave human blood (a frequent thought while I’m sitting up against a tree trunk during spring gobbler season), it turns out that most ticks will feed on most living animals, including birds, mammals, reptiles, and even a few amphibians. These crab-like arthropods have four life stages—egg, larvae, nymph, and adult—and most ticks prefer to have a different host animal at each stage of life. Tick larvae emerge from their eggs and, depending on the species, they may or may not be disease carriers at this early stage. After spending part of their life cycle on small animals, they often acquire pathogens, some of which cause disease in humans and other animals. Once the larvae have fed for a few days (usually on the smallest animals, like birds or mice), they drop off and molt into nymphs. While both nymphs and larvae are very small, larvae only have six legs, while nymphs are larger and have eight legs (like the adults). Once the nymphs have fed for a few days, they will drop off to molt again and become adults. Adult females eagerly attack humans and larger animals in order to engorge themselves with blood. Once full, they drop off to lay an egg mass, which can contain as many as 4,000 individual eggs (this depends on the tick size and species).

Blacklegged tick

Blacklegged Tick, <em>Ixodes scapularis</em> (Wikipedia/)

Scientific name: Ixodes scapularis

Native range: Found in Eastern half of the continental US

Distinctive features: The very dark brown legs are a hallmark of the species, giving rise to the “black-legged” name. The adult females also have a reddish-brown coloration to the back half of their bodies.

Active season: The larvae and nymphs are active during the late spring and summer, particularly in wooded areas. The adults are typically active from October through May in conditions where daytime temperatures stay above freezing.

Pathogens transmitted: This species is the principal vector for Lyme disease in the eastern United States (especially New England). They also transmit the organisms that cause anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and Powassan disease (a form of viral encephalitis that can occur as a co-infection with Lyme disease).

Habitat and details: Deer tick larvae, nymphs, and adults favor wooded habitats. The young ones live in leaf litter and the adult females prey upon the larger things that roam the forest—including us.

Winter tick

Winter Tick, <em>Dermacentor albipictus</em> (University of Alberta/)

Scientific name: Dermacentor albipictus

Native range: Found throughout the continental US

Distinctive features: Adults of this species have light brown legs and a dark brown body.

Active season: Larval ticks infest their host in the fall, molting into nymphs and adults while hiding in thick fur or hair of large animals. The winter tick may stay on the same animal host through all of the tick’s life stages.

Pathogens transmitted: Thankfully, winter ticks have not been documented passing diseases to humans or domestic animals.

Habitat and details: The adult winter ticks favor large game animals and are particularly fond of deer, elk, and moose. One anemic moose was found with an estimated 75,000 of these ticks attached to its hide. Lucky for us, winter ticks rarely feed upon humans.

American dog tick

American Dog Tick, <em>Dermacentor variabilis</em> (Benjamin Smith, via Wikimedia Commons/)

Scientific name: Dermacentor variabilis

Native range: California and the Eastern half of the continental US

Distinctive features: When the dark larvae molt into nymphs, they take on a light tan color. The adult males are mottled with brown and tan spots, while adult females have a brown body with a spotted tan “shield” on their head.

Active season: Nymphs are active May through July, while larvae are active from late April until September. Adults are active from April through August.

Pathogens transmitted: Adult American dog ticks can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) and tularemia.

Habitat and Details: American dog ticks prefer grassy areas and scrubland, frequently "hunting" along paths and trails. Nymphal dog ticks prefer small animals to feed upon, rarely attaching to humans.

Lone star tick

Lone Star Tick, <em>Amblyomma americanum</em> (K-State.edu/)

Scientific name: Amblyomma americanum

Native range: Found from Texas through Nebraska, and out to the Eastern seaboard

Distinctive features: Adult females have a very prominent white dot in the middle of their back. Adult males can bear whitish spots around the outer edge of their body.

Active season: Larvae are active in July, August, and September. Nymphs are most common May through August. Adults are often active from April through August.

Pathogens transmitted: Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) and ehrlichiosis is transmitted to humans by the lone star tick. STARI (Southern tick-associated rash illness) can also be transmitted by these bites.

Habitat and details: This species is mostly found in woodlands that contain thick underbrush, and they are also found in animal bedding areas. The larvae are not known to harbor communicable diseases, but the nymphal and adult stages can transmit the pathogens listed above. Lone Star ticks will feed on humans in all stages of their life.

Brown dog tick

Brown Dog Tick, <em>Rhipicephalus sanguineus</em> (Wikimedia Commons/)

Scientific name: Rhipicephalus sanguineus

Native range: Found worldwide and throughout the entire continental US, though more common in southern states

Distinctive features: The adult ticks have brown bodies and brown legs, though the females can have a slight yellowish coloration to their legs and faint mottling on their body.

Active season: I’m sorry to report that the larval, nymphal, and adult stages are active year-round.

Pathogens transmitted: All life stages of the brown dog tick can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) to dogs and humans. Nymphs and adults can also transmit the agents of canine ehrlichiosis and canine babesiosis.

Habitat and details: A common tick found in lawns, fields and grassy areas, the brown dog tick can go through its complete life cycle in as few as three months (all of which can occur indoors, in kennels and homes).

Rocky mountain wood tick

Rocky Mountain Wood Tick, <em>Dermacentor andersoni</em> (Wikimedia Commons/)

Scientific name: Dermacentor andersoni

Native range: Found throughout the Rocky Mountains and adjoining states. This species is typically found at elevations between 4,000 and 10,500 feet.

Distinctive features: These brown-colored ticks resemble dog ticks, and similarly, the females bear a horseshoe-shaped tan pattern on their head. Heartier than most ticks, adults can go almost two years without feeding on blood, while surviving the harsh mountain weather and deep cold of their native range.

Active season: Larvae and nymphs are active from March through October, while adult wood ticks can be active from January through November.

Pathogens transmitted: Colorado tick fever is caused by a virus transmitted by the Rocky Mountain wood tick at all life stages. Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) and tularemia can also occur from the bite of these ticks.