#sherlock Holmes meta

Text

I think a lot of modern Sherlock Holmes adaptations (as in, Holmes in the modern era) miss out by having Holmes work so closely with the police. A lot of people forget that Holmes was one of the original ACAB bitchies in fiction; he did not like the police. Yes, he worked alongside them sometimes, but he often talked about them with open distain. Sometimes he even worked directly against them (think of The Norwood Builder).

Granted this was mostly because the police lacked a lot of the skills they have today, such as forensics, something that Holmes was an advocate for, and tended to draw conclusions that did not fit the obvious facts. This has obviously changed - the police have a lot more resources at their disposal nowadays, but they are not a perfect institution - far, far from it, and if he were alive today, Holmes would have a lot to say about that.

I wish modern adaptations stayed true to the fact that in canon, Sherlock Holmes was the man you went to if you could not go to the police. If you had, perhaps, a criminal record, were homeless, were POC, were queer, were neurodivergent, an abuse victim, reliant on illegal substances, or even wrongfully accused, Sherlock Holmes would be the man you went to, and he would help you to the best of his ability.

Also, Holmes had his own unique sense of justice. Think of The Abbey Grange - a man murders the abusive husband of an old lover, and the wife is complicit. Holmes and Watson ultimately decide to let them go - Lady Brackenstall was being horribly abused, she was trapped in a loveless marriage with a violent husband. Captain Crocker murdered Sir Eustace, freeing Lady Brackenstall and perhaps saving her life. If the police had arrested Crocker, it would be very likely he would be hanged for murder, regardless of the circumstances.

Then there is James Ryder in the Blue Carbuncle. He, after Holmes pesters him, freely admits to stealing the jewel, but Holmes does not hand him over to the police and instead lets him walk free. It was Ryder's first offence, one he was manipulated into committing, and Holmes and Watson see him as a, quite frankly, pathetic little man. Holmes realises that if he were to turn Ryder in, it would destroy his life - he would be 'a jailbird for life'. Ryder committed a crime, but he is no criminal. Prison would turn him into one.

Holmes takes justice into his own hands, and in a way, it turns him into an anti-hero. But I think this a part of what makes him such a loveable, iconic character.

Holmes has created a 'safe space' within 221B Baker Street. I think this would be extremely intresting to explore through a modern lens.

#mine#i woke up this morning with Strong Feelings and i wanted to write them down#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#acd canon#sherlock holmes analysis#sherlock holmes meta#i admit i havent seen every modern adaptation so if this already exists........sorry#acd sherlock holmes

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sure this has been done countless times, but polls are fun and I'm curious, so...

For the purposes of this poll, I'm only counting shows/books/games/etc. where Sherlock is a main or very prominent secondary character, there's a decent amount of other Sherlock canon characters represented (at least a version of a John Watson), and there are some references made to the ACD originals. Not counting where he's only a relative of the lead but not a main (like Enola Holmes, RKDD, etc.)

Not counting the ACD original canon as an adaptation here, as none of these would exist without it. Everything else listed is adapting it in some way.

There's also some series I haven't watched/read yet but have been recommended that aren't on here yet for the purposes of space, including Detective L, Miss Sherlock and the Bonnie MacBird Sherlock books.

Feel free to reblog this for a larger sample size :)

#sherlock holmes#acd canon#acd holmes#yuukoku no moriarty#moriarty the patriot#cbs elementary#bbc sherlock#yuumori#house md#tgaa#the great ace attorney#herlock sholmes#granada sherlock#granada holmes#rdj sherlock#basil rathbone#detective fiction#sherlock holmes meta#my polls#jeremy brett#rdj holmes#sherlock and co#miss sherlock#sherlock holmes in the 22nd century#acd sherlock holmes#sherlock hound#the great mouse detective#polls#detective polls

596 notes

·

View notes

Text

i can barely tell car brands apart, but i can identify every type of victorian-era carriage

#hazards of the trade#very useful in day to day life of course#sherlock holmes#sherlock holmes meta#victorian culture#carriages#victorian carriages#victorian era#1800s#original post

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

something that I feel like even the most socially conscious Sherlock Holmes adaptations miss is that Sherlock started as a weird friendless college dropout who didn’t have enough money to live alone, had a pretty serious substance abuse problem, and who had to do work for anybody who’d give him a job because otherwise there wouldn’t be money coming in

like I appreciate that there are versions of the story that engage with him as a Wealthy Man, but even if you believe he’s some kind of landed gentry by blood he’s always had to work for a living and he doesn’t even have the clout granted by a graduation from university. he isn’t close to his family, he’s confirmed to be financially dependent upon Mycroft once (during the Hiatus) and was probably forced to ask for money early on as well, and it’s association with Watson that grants him long-term security and greater fame.

he’s never rich and he’s always fairly aware of what it is to be Not Rich

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It was as if a god had been destroyed by treachery. So children mourn, perhaps, when Santa Claus is murdered by their elders" (from The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes by Vincent Starrett about the public's reaction to Holmes' death)

This topic will always be interesting to me. This decision by Doyle is usually described as Doyle hating Holmes, though the truth was that the stories simply weren't what Doyle, as a writer, wanted to write. It's interesting how even when talking about Holmes' death as a character, he is described as a real human being; it's not "Doyle hated writing him", it's "Doyle hated him" (both aren't true, it's just if I were to simplify it). Starrett put it perfectly--at that moment, Holmes' death would've been like when kids found out that Santa Claus wasn't real, when people realize he's simply a character that the author can decide to discard at any moment. But Starrett also acknowledges that Holmes is more than that, he is beyond a fictional character. Doyle, without realizing, has lost control over this character that he has created. It doesn't belong just to him anymore. This writer is no longer the god of his creation, instead Holmes is the god and Doyle only brings upon the treachery.

Starrett also says that Holmes is "an illusion so real...that one might some day look about for him in Heaven, forgetting that he was only a character in a book."

#I'm still only 2 chapters in but I can tell this book will provide some interesting perspectives#for the foggy line between doylist holmes and watsonian holmes#he is both a character and a person and an idea#and I think starrett has an extremely good grasp on that#the private life of sherlock holmes#vincent starrett#sherlock holmes meta#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#arthur conan doyle#classic holmes

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been rereading A Scandal in Bohemia, as one does, and have been really struck by how blatantly, almost performatively queer-coded Holmes comes off in his first meeting with their client..

A slow and heavy step, which had been heard upon the stairs and in the passage, paused immediately outside the door. Then there was a loud and authoritative tap.

“Come in!” said Holmes.

A man entered who could hardly have been less than six feet six inches in height, with the chest and limbs of a Hercules. His dress was rich with a richness which would, in England, be looked upon as akin to bad taste. Heavy bands of astrakhan were slashed across the sleeves and fronts of his double-breasted coat, while the deep blue cloak which was thrown over his shoulders was lined with flame-coloured silk and secured at the neck with a brooch which consisted of a single flaming beryl. Boots which extended halfway up his calves, and which were trimmed at the tops with rich brown fur, completed the impression of barbaric opulence which was suggested by his whole appearance. He carried a broad-brimmed hat in his hand, while he wore across the upper part of his face, extending down past the cheekbones, a black vizard mask, which he had apparently adjusted that very moment, for his hand was still raised to it as he entered. From the lower part of the face he appeared to be a man of strong character, with a thick, hanging lip, and a long, straight chin suggestive of resolution pushed to the length of obstinacy.

“You had my note?” he asked with a deep harsh voice and a strongly marked German accent. “I told you that I would call.” He looked from one to the other of us, as if uncertain which to address.

“Pray take a seat,” said Holmes. “This is my friend and colleague, Dr. Watson, who is occasionally good enough to help me in my cases. Whom have I the honour to address?”

“You may address me as the count Von Kramm, a Bohemian nobleman. I understand that this gentleman, your friend, is a man of honour and discretion, whom I may trust with a matter of the most extreme importance. If not, I should much prefer to communicate with you alone.”

I rose to go, but Holmes caught me by the wrist and pushed me back into my chair. “It is both, or none,” said he. “You may say before this gentleman anything which you may say to me.”

The Count shrugged his broad shoulders. “Then I must begin,” said he, “by binding you both to absolute secrecy for two years; at the end of that time the matter will be of no importance. At present it is not too much to say that it is of such weight it may have an influence upon European history.”

“I promise,” said Holmes.

“And I.”

“You will excuse this mask,” continued our strange visitor. “The august person who employs me wished his agent to be to you, and I may confess at once that the title by which I have just called myself is not exactly my own.”

“I was aware of it,” said Holmes dryly.

“The circumstances are of great delicacy, and every precaution has to be taken to quench what might grow to be an immense scandal and seriously compromise one of the reigning families of Europe. To speak plainly, the matter implicates the great House of Ormstein, hereditary kings of Bohemia.”

“I was also aware of that,” murmured Holmes, settling himself down in his armchair and closing his eyes.

Our visitor glanced with some apparent surprise at the languid, lounging figure of the man who had been no doubt depicted to him as the most incisive reasoner and most energetic agent in Europe. Holmes slowly reopened his eyes and looked impatiently at his gigantic client.

“If your Majesty would condescend to state your case,” he remarked, “I should be better able to advise you.”

The man sprang from his chair and paced up and down the room in uncontrollable agitation. Then, with a gesture of desperation, he tore the mask from his face and hurled it upon the ground. “You are right,” he cried; “I am the King. Why should I attempt to conceal it?”

There’s a lot going on here, so let me break it down a bit.

Previously Holmes had been described as pacing in front of the window as Watson came in, making all kinds of accurate and lively deductions - the “most incisive reasoner and most energetic agent in Europe” persona the king expects. Holmes is not depressed or physically exhausted, in fact he’s fairly keyed up like he so often is at the start of a new case, but not excessively. He’s received a letter telling him to expect a new case involving sensitive details involving the very powerful (” Your recent services to one of the royal houses of Europe have shown that you are one who may safely be trusted with matters which are of an importance which can hardly be exaggerated.”) He recognizes their client to be the actual king of one of the Germanic states, and how does he present himself?

He just ... lays there. “The languid, lounging figure of the man.” This is the point I’m least confident of, since I’m hardly an expert on Victoriana generally or about stereotypes of gay men in particular. But the king comes off as heavy-handed, masculine to a fault. Whereas Holmes is half a step from lounging on the chaise longue, hand thrown backward against his forehead. The difference is striking, that’s for sure, and I’m left wondering (with no hard historical evidence to back this up, as I said) if this isn’t the Victorian equivalent of an intentional limp wrist gesture.

The King is ridiculous. He’s the bull in the china-shop. Holmes also knows who he is and exudes this aura of not-like-him. And given the way less-than-mainstream sexualities and prostitution were linked to poor, weak character in the period, there’s a real juxtaposition going on here between the public figure so manly he couldn’t possibly have been caught in a compromising photo with a somewhat risque woman, versus ... whatever the hell Holmes has going on here.

Then there’s Watson. To be clear, Holmes didn’t call him in; Watson just happens to stop by. When he learns Holmes is expecting a client he tries to leave, both before the King enters and after the King questions whether this extra man can be trusted. He brings no special skills to the table, and really only starts the fire at the Adler house later on; Holmes had a whole crowd of people I’m pretty sure he could have had do that if Watson hadn’t been there. But Holmes repeatedly positions them as a necessary pair, Watson as his trustworthy companion. “It is both, or none.”

His trusted compatriot who, it must be said, Holmes positions in a chair close enough he can reach out and grab his wrist to keep him from leaving, all while maintaining the “languid, lounging figure of the man.” Granted, it’s not quite as scandalous as Irene actually sitting on the king’s lap in that photo, but it’s far closer an imagine than Doyle could have given us.

Finally, there’s this bit where Holmes and the King discuss the photo itself:

“Let me see!” said Holmes. “Hum! Born in New Jersey in the year 1858. Contralto-hum! La Scala, hum! Prima donna Imperial Opera of Warsaw-yes! Retired from operatic stage-ha! Living in London-quite so! Your Majesty, as I understand, became entangled with this young person, wrote her some compromising letters, and is now desirous of getting those letters back.”

“Precisely so. But how-“

“Was there a secret marriage?”

“None.”

“No legal papers or certificates?”

“None.”

“Then I fail to follow your Majesty. If this young person should produce her letters for blackmailing or other purposes, how is she to prove their authenticity?”

“There is the writing.”

“Pooh, pooh! Forgery.”

“My private note-paper.”

“Stolen.”

“My own seal.”

“Imitated.”

“My photograph.”

“Bought.”

“We were both in the photograph.”

“Oh, dear! That is very bad! Your Majesty has indeed committed an indiscretion.”

“I was mad-insane.”

“You have compromised yourself seriously.”

“I was only Crown Prince then. I was young. I am but thirty now.”

“It must be recovered.”

“We have tried and failed.”

“Your Majesty must pay. It must be bought.”

“She will not sell.”

“Stolen, then.”

“Five attempts have been made. Twice burglars in my pay ransacked her house. Once we diverted her luggage when she travelled. Twice she has been waylaid. There has been no result.”

“No sign of it?”

“Absolutely none.”

Holmes laughed. “It is quite a pretty little problem,” said he.

“But a very serious one to me,” returned the King reproachfully.

I mean, I know Holmes is an investigator and a keen reasoning, but this quick knowledge of the mechanics of blackmail and the ways of getting incriminating documents back is just a bit much. It’s not totally blatant and he certainly has a good professional explanation for why he’d be aware of all that, but the sheer speed with which he rattles off all the ways the compromising materials could be addressed: it’s almost like it’s a question he’s had to be aware of himself, at least in the hypothetical

And the king’s excusing his behavior as insanity is certainly interesting, because that’s the exact way homosexuality was being discussed at the time, at least in certain contexts. And while I’d need to do a whole other post to dig into this, this whole distinction between the King’s almost farcical masculinity and Holmes’s stereotypically queer behavior here sure puts his snubbing of the King in the final scene and his comments about Adler’s “character” in a very interesting light.

There’s certainly something going on here, is all I’m trying to say, and i don’t think we as a fandom have talked nearly enough about it.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Granda Holmes "The Naval Treaty" Mini Analysis

(Cross-posted on Dreamwidth)

Having recently been reconsumed by my old Sherlock Holmes obsession, I have been enjoying rewatching (and in a few cases, watching for the first time) the 1984 television adaptation of the story, typically referred to as 'Granada Holmes'. The third episode of the series, "The Naval Treaty", is a good episode in general. But one curiosity about it is that Holmes spends most of the episode seeming quietly Bothered by something, and it is also this episode that gives us the infamous Rose Speech - right in the middle of a client interview, which is entirely odd behavior for Holmes and seemingly spurred on by...nothing in particular. The episode itself offers no direct answer to these things, so, with my last rewatch, I made a point to keep my analysis goggles on and see if I could come up with a possible solution.

The case itself doesn't have anything about it that would obviously agitate our titular detective (there are other episodes where that's the case, and it's a lot more out in the open) - it's just a mystery revolving around how some government papers got stolen in an unusual way and trying to find where they could have gone. But there are two other points in the episode that I believe to be the culprit of The Moods:

This episode has Holmes mention twice Watson's medical practice as something that might prevent him from wanting to join him (Holmes) on cases. The first time is openly testy ("Oh, if your cases are more interesting than mine >:/"), while the second time is during a more quiet, melancholy moment. Watson had noticed Holmes being Bothered as well, and asked him if was alright. Holmes initially shrugged it off, but then made some comment about wanting Watson to come with him the next day to investigate if it won't keep him from his 'legitimate work'. There's some carry-over or call-back to the testy tone from earlier, but the actual mood has a lot less bite and is followed by a more earnest request.

The client in this episode is specifically an old friend of Watson's (not sure when they became friends though lol since Watson says he bullied the guy at school, but they only seem to hold affection for each other at present)

Now, one of the interesting things about Granada Canon, is that despite mostly trying to be as faithful to the original stories as possible, they chose to entirely write out Watson marrying, and significantly rearranged the order of the cases. The result of this is that in many of the stories where Watson, in the books, is visiting or returning from time spent with his wife, instead sees him coming back from working at his medical practice or simply a vacation. I could be wrong, but in the books I don't think Watson having a practice ever overlapped with him living with Holmes, so in Granada we get to see a little bit of what that dynamic looks like.

And in this episode, I think we see that it is a matter of some tension and insecurity, at least on Holmes' part. And I think it's because, for Holmes, the cases are his career, his passion. His professional title is Consulting Detective. And also notably, it's a job he invented, not one general society tends to understand or take seriously until they see how he works and how well he does get results. Watson, on the other hand, is a practicing medical doctor - a traditionally respected position and something that frankly should be a full time job. He never takes on any kind of title in relation to the work he does with Holmes, even though he works nearly every case with him. Holmes refers to Watson sometimes as his biographer since Watson always writes up their cases, but I can't recall at present anyways a time where Watson referred to himself as such (the closest you get is that Holmes always introduces Watson as a 'colleague', which Watson does call himself once as well, which is fairly ambiguous).

And while Holmes obviously cares about the work a lot on its own merit, he makes it clear many times in the show that having Watson accompany him makes a significant difference to him, and he clearly prefers it. This is only episode 3 of the series, but in episode 1 we had him insisting Watson join him for the case and telling his client adamantly that he'd work with both of them or neither of them, and in the second episode, we see Holmes low-key mentoring Watson in the craft of deduction; and now we see him being incredibly moody at the fact that Watson has another profession. So, I think he fears that Watson sees the cases as just a fun hobby, and isn't nearly as passionate about them (or about working together) as he is, since functionally there's not a 'reason' for him to work on the cases other than just Wanting To.

This case's client being an old friend of Watson's I think sort of passively exacerbates this insecurity. For a decent chunk of the time they know each other, Holmes considers Watson his only friend. And while Watson doesn't seem to have many close friends either, he nevertheless is the more social of the two and does have old contacts he's still fond of, and I think for Holmes it was just another reminder that Watson could, from his perspective, easily have a normal, respectable life without him at all. And for all that Holmes carries himself with great confidence, there often seems to be an underlying anxiety when it comes to his requests that Watson accompany him, so I think he worries Watson will lose interest in him eventually and want a more 'normal' life (which, there's even more evidence of that in the books, but I think in the show it's definitely still there).

In general, I feel like there's a lot to say about how Holmes and Watson sort of juggle the merging of their professional and personal lives together in Granada especially, but that would probably turn into a whole other essay. xD Case in point, though, I believe that was at the root of Holmes' moodiness this episode. And it would explain why it stays so understated unlike other times things bother him; there really wasn't anything actionable he could about it, it was just this persistent anxiety/melancholy. Because in the episode, Watson is working the case with him, he is being attentive, and Holmes doesn't have any real personal issues with Watson's other friend. So, Holmes keeps it mostly to himself, as much as I would have loved a more direct follow up on it at some point.

(The Rose Speech, placement wise then, I think was that since the interview with the client had mostly come to a close, there wasn't any other immediate distraction, and so in his more emotional mood, he fixated on the rose and philosophy. There's probably more analysis to be drawn from the exact content of his speech in the context of the episode, but that also would be a whole other essay. xD Maybe a little bit of a reach, but it's sort of neat also though that he'd specifically go to a flower while feeling insecure about his friendship with Watson, since Granada Canon especially emphasizes that Holmes generally dislikes nature/the countryside while Watson is a fan. In the book as well Watson specifically mentions the little aside being odd since Holmes normally never showed interest in 'natural things'.)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I respect Sherlockians who Play the Game (live as though Sherlock Holmes and John Watson were real and treat the canon as true stories), and admire the commitment of those who hold to that no matter what. It’s a fun and very unique experience across all fandoms that I don’t see anywhere else.

But I did see a post about the Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes series by Laurie R King (which is good fun though not without some stuff that does deserve questioning). In that thread, one of the comments was from David Marcum, who does the MX Publishing’s massive collections of Holmes stories and who is one of the more serious who Play the Game. He linked a post where he talked about how he rationalizes the series with The Game—specifically how can one rationalize a Holmes who is in retirement marrying a young woman in her twenties.

You can read it here

Basically what I find interesting is that Marcum firstly adheres to Holmes’ supposed age in the Game, making him in his very late 60s in most of the Russell years, instead of his early 50s as suits the story (Holmes remarks to Russell that he was often assumed to be older due to Watson’s stories). A woman in her 20s with a man in her 50s will still raise eyebrows, especially as he met her as a teenager, and yet that’s not the same gap as 70 and 20. Likewise Russell has gone through a lot of life experience by the time any romantic moves are made; her and Holmes are on fairly even footing by then. (Do I still approve of the age gap? No, but then again maybe that’s just my personal preference.

But my bigger qualm with Marcum’s rationalizing the Russell thrillers within The Game is how he rationalizes it all. Russell is a woman who is sick in the head after her family’s death, becomes obsessive over Holmes (fairly directly in opposite to the text where she doesn’t care if he’s a neighbor or a myth, and berates him to his face for assuming her intelligence—point in her favor, I might add), and further descends into madness creating a romance between them in her mind, a life well lived with family.

Here’s hoping I’m not the only one who is a little disturbed by this—yes, the way to rationalize an intelligent woman holding her own with Holmes intellectually, romantically, and as a crime solver, is that she’s insane and disturbed and creepy. Yuck.

He notes that he’s on board with Holmes having romance with Irene Adler, which is fairly bonkers to me. I can read stories where they’ve had a romance, in fact, if memory serves, the two had something brief pre-Russell era in that canon. But I do not like the idea that Holmes cannot be romantic with a “fan made” character. An argument can be made that many Dan made characters are Mary Sues, or John Does, for Watson, as many find the good Doctor difficult to write (and I agree, he is, but that doesn’t always warrant a stand in when Watson would’ve suited the same character actions). But it’s strange that when the newcomer is a woman, she’s hated or interrogated so thoroughly, especially when Mary Russell is so strong a presence and definitely holds her own as a unique character and not just a stand in (even if Watson is a bit dim in her stories compared to canon, we can forgive that because he is so loved by everyone in the Russell texts).

Instead, if I were playing The Game, i would submit this (and I plan on writing a fic to challenge Marcum’s own little story):

Russell is the neighbor of semi-retired Holmes and their meeting is unchanged, he begins to tutor her and saves her in his own way, and she him. The events of Beekeepers and O Jerusalem take place fairly close to recorded, save a few alterations.

Holmes in retirement is living with Watson, as a romantic partnership. Russell discovers this early and although taken aback at first, comes around to it quickly. She creates the stories as fabrications to hide their romance, and with permission from H&W, creates the romantic relationship on paper between her and Holmes to disguise what would’ve been illegal and perhaps reputation ruining for the pair.

The three remain their own sort of family and the series progresses as published to continue that fabrication of the truth.

No mentally disturbed Russell, but a Russell who’s still strong and sane and perhaps at times cleverer than Holmes. No creepy stalker behavior by a girl, but the same in canon amazing woman we get to see grow up. Same partnership, just no romance.

I wonder if this solution wouldn’t occur to a canon purist who plays the game— a purist up until the point where they play a game of rationalizing a non-canonical work to fit their version of Holmes. Not saying that to be scathing, just if one is to entertain the possibility of modern pastiche fitting into The Game, it would be fun to be a little more creative.

I wonder if queer H&W doesn’t slot into their version of the game, and so a clever woman protecting that deep love wouldn’t either. But it seems a far better solution to approach the Russell texts under The Game than Marcum’s rationalization. Again, I’d want for some more creativity than his version.

But then, My Holmes, when I finally write him, is queer, and I enjoyed the Russell series, so it wasn’t a difficult solution.

#sherlock Holmes#all Holmes is good holmes#Mary Russell#Laurie R King#David Marcum#John Watson#Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes#my posts#meta#sherlock Holmes meta#queer Holmes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

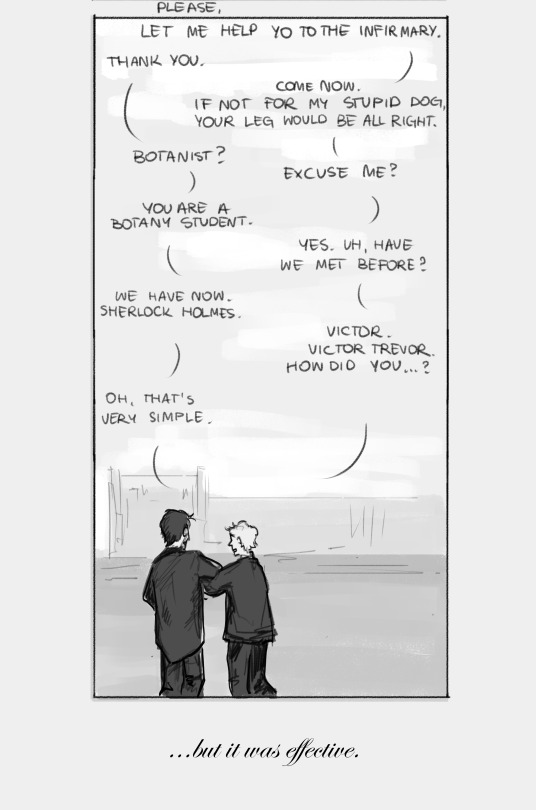

I have had a lot of thoughts on the original story after listening to the Sherlock&Co "Gloria Scott" and a new headcanon just dropped.

Chapter 1: part 1 - part 2 - part 3 - part 4 - part 5 - part 6

Masterpost (Index)

AO3

thoughts, if you're curious:

As far as gay Victor Trevor absolutely got me, I don't think there was anything serious between him and Holmes. This all comes down to my reading of Holmes, who is (to me) too aroace-spec to get involved in a regular relationship (althouuuughh about Holmes, his sexual and romantic orientation and him discovering it I have had so many thoughts I could write a whole essay). He likes to have a default person though, someone who will take him as he is, and maybe even admire a little - now that's Watson, earlier it was Trevor.

And yea I think Victor got a crush straight away after their first meeting, maybe they even talked about this at some point. Maybe Holmes said that he won't be able to reciprocate this affection but if Victor is fine with keeping things as they are, then he is too. I like to think they stayed pen friends even after Trevor's leave.

I feel like I should emphasize this? My intention in the comic was to make Trevor visibly flustered because he didn't expect a young attractive boy (he's hopeless in my head), while Holmes simply didn't expect to see someone his age and so sincerely sorry.

#i feel like i lost the ability to write meta for my drawings you know#the irrational feeling that i'll get misinterpreted if i don't explain everything thoroughly is taking over#truly horrible#also my imposter syndrome is full on lately in terms of my art so ughh it's so hard to share anything#at least i don't think anyone even sees my sh art so i may ramble in the tags here an noone notices :3#my art#sherlock holmes#victor trevor#acd holmes#acd canon#sherlock holmes fanart#i am rotating young holmes in my mind lately#oh yes and i made victor a botanist and named his dog dante for no apparent reasons#holmes collage adventures

566 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m never not thinking about sherlock holmes and aj raffles as narrative mirrors

holmes is a bohemian, an unconventional man who is shown to struggle with mental health and addiction. he is fairly explicitly neurodivergent despite being written before that concept existed. in many ways, he doesn’t live up to the standard of a victorian gentleman; he’s a perpetual bachelor who is uncomfortable in many social situations and is described by watson as having a sensitive nature. his relationship with scotland yard and the law is often uneasy; early in his career the police frequently belittle him and his methods. he has to work to overcome the fact that he is perceived as a deeply odd person. scotland yard puts up with him because he gets results until he eventually earns their respect.

raffles, on the other hand, is a criminal who hides behind his respectability and social standing. he’s charming, handsome, and charismatic. he dresses in full gentleman’s evening wear to commit crime, allowing him to pass by policemen without arousing suspicion. he’s a well known cricketer from a privileged public school background who excels at playing the role of a society gentleman. this allows him to avoid suspicion despite being very unsubtle. the biggest advantage raffles and bunny have is a social position that shields them from suspicion.

although holmes is a gentleman from a similarly privileged background, when he’s in situations with men of comparable social standing this privilege is somewhat negated by how at odds his personality is with societal convention. while holmes is certainly a good enough actor to mask his quirks- and thus receive kinder treatment and more respect- he chooses not to.

the quality of holmes' work compensates for his eccentricity, whereas raffles relies on being perceived as a model of respectable society to conceal the criminal nature of his work.

a queer reading of holmes and raffles reinforces this dichotomy: a queer holmes who refuses to so much as put on a pretense of victorian heterosexual masculinity, openly proclaims a disinterest in women, and leads a bohemian lifestyle would have been at more risk of suspicion than a queer raffles, who- while also a bachelor- has a public persona that is enmeshed with hetero-masculine institutions like athletics and clubs. his bachelorhood lends itself to a society playboy interpretation in a way that holmes’ does not.

reading holmes as queer makes his very nature criminal, even as he works as a detective. he is only able to atone socially for his perceived aberrance by acting as an agent of the law that condemns people like him. raffles is able to embrace crime and the criminal aspect of his own nature because on the surface he fits so well into social norms in a way that holmes doesn’t. there’s just such a rich contrast in the way holmes and raffles each engage in respectability politics and how it impacts the way they’re perceived.

#the neurodivergent experience of wanting to be so good people have to put up with your quirks#meta#mine#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#aj raffles#raffles#crime and cricket#my writing

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need to reread the Yuumori manga now that I've finished my rewatch, but one thing just occurred to me: Sherlock uses disguises fairly often in ACD canon (all credit to @thenorwoodbuilder for this thorough post with the details), but he doesn't disguise himself much in Moriarty the Patriot, does he? I don't have the best memory, but I can think of only one time he uses a disguise in the manga as far as I've read, and that was to surprise a friend.

It’s unusual for him, but maybe it's because his role in this adaptation is different than most Sherlock media. He’s usually not the one with the grand plans, the mastermind, instead he’s the one unraveling things after the fact, using his intellect but not as much scheming ahead of time. We see much more planning scenes from the Moriarty group’s POV, as their operations are more of the focus.

From what I remember, Irene, Bond and Fred use disguises the most here, and Liam does a little too after the fall when he returns to London (otherwise mostly preferring to cover up with hooded cloaks), but Sherly so far hasn't tricked one criminal that I can recall by using a more in-depth disguise. He'll use ruses for sure, like in The Sign of Mary or A Scandal in the British Empire, but besides putting on a hat or pretending to have a different job, he's generally just being himself without too much physical alteration.

Maybe it’s also because there’s already a few different characters who specialize in disguises, that as a result the creators chose not to focus on that approach with Sherly? Irene and later Bond particularly have a talent for them coming from the theater world, so maybe Sherly doing the same often would be too redundant in the story?

#moriarty the patriot#sherlock holmes#pbjelly thoughts#yuukoku no moriarty#acd canon#acd holmes#yuumori#irene adler#fred porlock#james bonde#sherlock holmes meta

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok so I listened to SHOS pts 1 and 2 and I just have thoughts about the whole meta around mentioning Moriarty.

Because the podcast plays John and Sherlock as real. As if all of this is actually happening now in our world. It puts any listener with even a passing knowledge of Canon in the very intense position of knowing what's going to happen in a broad sense. We can see how John and Sherlock are doomed by the narrative.

We hold our breath as Sherlock talks about bodies of water though especially waterfalls.

We wonder how John will feel in the future about singing "don't go chasing waterfalls"

We scream as we hear James Moriarty get a shoutout.

But we can't warn either of them what lies ahead. If we try, they won't see it. It will be ignored or dismissed. There's also a sense that we cannot cross that line because it would also change the narrative and we can't because it's already literally been written.

Every listener has been forced into the role of Cassandra with this podcast and it is fascinating.

#sherlock & co#sherlock and co#sherlock holmes#john watson#james moriarty#meta#thoughts and musings#its soooo interesting playing this as real but still maintaining that thin veneer of a 4th wall

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

holmes and watson as the sun and moon respectively because holmes is a burning, eccentric force of nature who collapses like a dying star when his mind seizes him, because watson is a solid rock who provides the stone for holmes to lean against and reflects his light by documenting the cases and righting holmes' thought process and scattered bearings. holmes as the light that comes back into watson's life after he's been stripped of hope and forced to wander around london's dark streets without any friends or familiar faces to support him. watson as the calm, ever-present soldier who is capable of burning with equal intensity but is often underestimated in his power because he isnt as outwardly flashy as the sun. holmes as the sun because he does everything with passion, with an inward intensity, watson as the moon because he has the same power but with softer lights, not blinding but glowing, calming. holmes and watson as the sun and moon because they will always be said in conjugation with each other. they belong as one. holmes as the sun because he is the light and watson as the moon is his conductor of light. holmes as the burning sun and watson as the shining moon- do you. do you understand.

#i was listening to o sol e a lua and started thinking about them again#not equipped for rambling#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#john watson#acd watson#granada holmes#does this count as meta#im sick and emotional

688 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autistic Sherlock and Jonk Watson. What a pair they are.

#sherlock & co#sherlock and co#sherlock holmes#john watson#autistic sherlock#jonk watson#I can say with absolute certainty that podcast!holmes is by far my favourite modern adaptation of the ACD canon#it is perfect in every conceivable way.#from the cases to the humour and meta references. and especially the interpersonal relationships between our leads#all of these elements are being handled with such care and it all feels so lovingly crafted#what a masterpiece.#…I should probably make a full post about this. instead of ranting in the tags

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know what I love about BBC Sherlock?

You only catch some things on your 2nd, or 5th or 10th rewatch.

Like with Mycroft and Sherlock.

You watch Mycroft be annoyed at Sherlock calling at Christmas, so you think he would rather be left alone and doesn't want to deal with anyone, including Sherlock.

But his initial expression is one of surprise. He doesn't want to believe that Sherlock could be calling for sentimental reasons because he cannot bear to be wrong.

He wants Sherlock to show him he cares, like he did back when they were children.

And notice his wording there. "Did they pass a new law?" Sherlock is not the one who cares about upholding the law, Mycroft is. He is setting the stage for Sherlock to banter, but Sherlock just tells him Irene Adler is dead and hangs up.

When Sherlock calls Mycroft (despite the fact he prefers to text) in TSO3 many speculate the reason he wants him at the wedding is to have someone for support.

Mycroft says they will spend more time together now that John is married. Just like old times. He knows Sherlock would hate that, yet Sherlock doesn't deny it. He could say he can spend extra time with Mrs Hudson, or Lestrade or Molly or Wiggins.

He could say he doesn't need him at all. But we know that's not quite true.

If Sherlock was being sincere here and said he needs someone on his side, by his side, someone to be there for him, so he feels less alone... Mycroft would most likely think he was being mocked. He wouldn't believe him. Why should he?

When Mycroft tells Sherlock his loss would break his heart, he isn't doing it because of the drugs.

The drugs are just an excuse to hide behind. A smokescreen. He can't even look at Sherlock while is he saying it because he knows what's coming. Mockery.

"What the hell am I supposed to say to that?"

Mycroft broke script. He said the quiet part, the subtextual part out loud. I do care about you and it would break my heart if you died.

Sherlock doesn't know what to say. You can even read his bewildered statement as a genuine question. Mycroft does, in a way. So he answers.

"Merry Christmas?"

"You hate Christmas."

"Perhaps there was something in the punch."

I know you are up to something.

On the tarmac, Sherlock didn't even want to say goodbye to his brother. But when Mycroft calls him in 4 minutes, Sherlock has no idea Moriarty might be back. He just thinks Mycroft couldn't go even five minutes without speaking to him again and checking up on him.

Sherlock didn't say goodbye to Mycroft because he knew that wouldn't be the last time he'd hear from him.

"I will always be there for you."

"Shouldn't you be out there getting me a pardon, like a proper big brother?"

"He was a rubbish big brother." Was, not is.

"You were great."

He didn't find Lady Bracknell convincing. He isn't talking about that.

"Dr Watson? Look after him, would you?"

"Mycroft. Make sure he's looked after. He's not as strong as he thinks he is."

Neither of them are.

#the holmes brothers#mycroft holmes#sherlock holmes#sherlock bbc#bbc sherlock#adding some tags#sherlock meta#the holmes brothers meta#holmes brothers meta#idk if this counts as meta

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

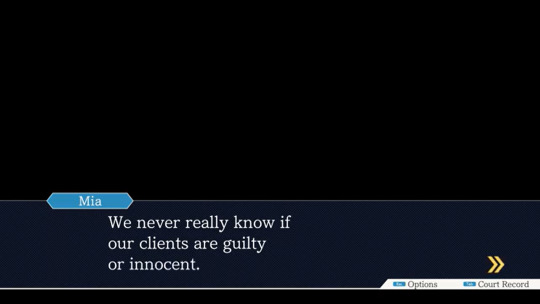

One of the major themes of ‘Ace Attorney’ has always been trust, obviously. Like, this is the most important creed that Mia Fey passed down to Phoenix and from there to anyone he has touched.

As well as just generally being one of Phoenix’s most important positive qualities.

The entire arc of the first game hinges on the idea of the Power of Trust, with it being a core pillar of Phoenix's relationships with both Miles and Maya.

And even the main gameplay themes of ‘turnabout’ and ‘turning your thinking around’ are linked to this theme of Trust. The whole idea around the narrative of a ‘turnabout’ is that the Defendant seems obviously totally guilty, but the defense attorney proves them innocent by Trusting in their innocence.

And ‘turning your thinking around’ is generally framed as - rather than the general mystery-solver mindset of trying to deduce what has happened from the evidence given - trusting in your client’s innocence and looking for evidence that should be there if they are innocent/that other person is the culprit. Using the Trust in the client as the foundation to build your logic from.

And being such a core theme of the franchise, the games started reiterating on and deconstructing it almost immediately. “Farewell, My Turnabout'' having a Guilty Client feels like the most obvious example, maybe. But actually the game starts casting suspicions on Engarde pretty early on, and most of the emotional turmoil related to him is more of the, like “will Phoenix sacrifice the truth for Maya’s sake” hostage situation stuff.

I think the more important stuff in that case is more about the Phoenix-Edgeworth drama. How Phoenix’ sense of trust, which seems like such an unwavering and unbreakable virtue in the first game, does actually have limits. Phoenix feels that Miles has betrayed his trust by, y’know, running off to Europe and making him think he was dead - and it takes him time to learn how to regain this sense of trust in him.

Meanwhile, Matt Engarde, he considers himself strong because he trusts in no one. In contrast to Adrian, who both he and she herself see as ‘weak’ because of her tendency to blindly trust the person she is dependent on. But at the end, it’s Matt’s distrust in everyone around him that brings on his own downfall.

And the game after that adds in Dahlia Hawthorne who is, as Mia Fey’s nemesis, a sort of representation of the dangers of trust. A character who uses and manipulates those who put their trust in her.

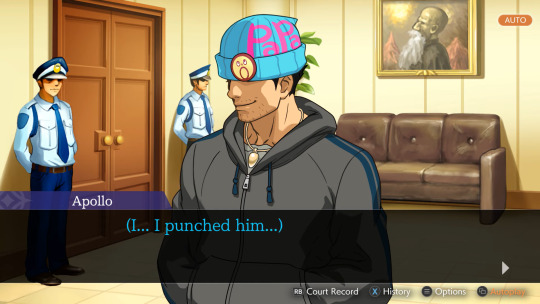

“Apollo Justice: Ace Attorney” establishes its more cynical and deconstructivist tone compared to the original trilogy in part by always putting some sort of element of distrust between the Lawyer and the Defendant. With Apollo basically unable to really have a decent conversation with any of his clients, many of them being antagonistic towards him or hiding things from him. Phoenix Wright was basically the only defendant Apollo went into court actually 100% putting his trust in him… and we all know how that worked out.

And this moment is especially effective because… if you’re playing this game unspoiled after finishing the Phoenix Wright Trilogy, you probably trust Phoenix as well! The emotions Apollo feels as he sees who Phoenix had become are meant to mirror the emotions the Player probably feels at this very moment. And the hints and questions about what Phoenix did in the trial seven years ago are a challenge to the trust of both Apollo and the Player. Both of them are stuck between what they knew of Phoenix before and the revelation of what Phoenix confessed to in “Turnabout Trump”. Apollo’s uncertainty is the player’s uncertainty as well.

And even if Apollo’s image of Phoenix is somewhat improved by “Turnabout Successions” and it’s clearly established that, no, Phoenix never knowingly used forged evidence as an attorney… There’s no big reconciliation that fixes everything like with Phoenix and Miles. It’s clear that Apollo’s sense of trust, in Phoenix Wright and in general, never quite recovered from the events of AJAA. Later games do still reiterate that he’s a lot more distrustful than other playable attorneys.

(And that’s also a point where the Player-Player Character Synergy from ‘Turnabout Trump’ kinda diverges, since I think most Players do regain their trust in Phoenix by the end of AA4 at least. Especially as unlike Apollo, we actually got to be inside his head again - that’s not exactly an experience Apollo will ever get to have. )

But, well, maybe it’s because it’s just really fresh in my mind, but I just think what ‘The Great Ace Attorney’ Duology does with this theme is just… really cool!

These games really play on the idea of challenging the trust… not just of the Player Character Ryunosuke, but also of the Player themselves. Because Ryunosuke also gets to have a Guilty Client… as his very-first actual client who is not himself. And since the game doesn’t lay on the suspicion quite as thick as with Matt Engarde, and since there’s no hostage situation of course… This plotline can have emotional synergy between the Player and the Player Character and focus a lot more about the emotional repercussion of putting your trust in someone totally absolutely unworthy of trust.

And how this betrayal of trust haunts the characters moving forwards. How Ryunosuke now finds himself being held back by his doubts due to the memories of this terrible trial, and... not necessarily a lack of trust in others as much as a lack of trust in himself. How Susato is driven to do something she considers unforgivable - tempering with the Crime Scene behind the police’s back - because that trial had made her lose trust in the entire British Justice System.

The entire climax of the first game is thus a reaffirmation of the power of trust. By unwaveringly defending Gina - a girl they have bonded with, but has also been extremely uncooperative, shady, dishonest and literally involved in what went down in the McGilded Trial, in a very grueling and seemingly unbeatable trial - Ryunosuke and Susato rediscover their ability to trust their defendant. Because, yeah, trust is a leap of faith - you never know when you’re gonna meet a McGilded or a Dahlia Hawthorne - but it’s also absolutely worth it.

And then with the themes of conspiracy strawn throughout the games and especially ramping up in the second game, that’s really kinda a thing that’s bound to sow seeds of paranoia and distrust in the Players about… all sorts of characters. Like, okay, I am fairly sure that pretty much every player who first walked into the Lord Chief Justice’s office and saw Mael Stronghart was like “Oh look! That’s the Final Boss!”. But with the hints for there being some sort of web of intrigue being hidden in the shadows, there’s plenty of other characters that skirt the line between feeling suspicious and trustworthy. The reveal that Seishiro Jigoku is actually a culprit was one of the best-done reveals in the whole franchise. And on the other hand, there are many reasons to be suspicious of Yujin due to the amount of secrets he clearly keeps, and yet he turns out to be a very straightforwardly heroic character.

And then there’s Kazuma. And Mael Stronghart might be the Obvious Final Boss to the Conspiracy and Murder Mystery parts of the game, but within this thematic throughline of the challenges of trust, Kazuma is pretty much that part’s Final Boss.

Initially designed to be someone both the characters and the players intently trust, both in terms of the meta-perspective of how he’s set up to be a kinda Mia-Miles hybrid and any Player with knowledge of the previous games will know that’s a kind of person you can rely on. And in general, even to newcomers, everything he says and does in the first two chapters of the game make him feel like just a very upstanding guy you can trust.

Then, when he comes back in the second games, he comes back with a new attitude that feels colder towards Ryunosuke (and thus the Player) and that’s also coupled with a whole bunch of mysteries about him that were hinted in the previous game, but are now coming to the forefront.

And as the Trial of Barok Van Zieks progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that Karuma has, theoretically, all the possible motivation to kill Greyson and frame Barok for it, that he was one of the last people to see Gregson before his death and that he literally brandished a sword at him. And despite how cagey and shady he acts, he still insists he never killed anyone.

And the reveal that he has knowingly participated in an assassination plot behind the backs of both Ryunosuke and Susato is bound to cause a feeling of shock, confusion and betrayal not just in these characters - but also in the Player. The Player and Player Characters are in a lot of emotional synergy through this entire Kazuma storyline. These feelings of conflict between wanting to trust Kazuma after seeing him in his best and all the mounting suspicions due to all the revelations about him are really felt by all three of us.

And in the end the challenge for Ryunosuke and Susato is not to abandon Kazuma completely, and it’s not to continue blindly trusting their old idealized view of Kazuma - it’s to face the fact that he has kinda lost his way for single-minded revenge, while also still trusting that he is deep-down the same good not-murdery man they have known him as before.

#ace attorney#the great ace attorney#great ace attorney#gyakuten saiban#dai gyakuten saiban#dai gyatuken saiban#tgaa#tgaac#tgaa2#ryuunosuke naruhodou#kazuma asogi#ryunosuke naruhodo#gaac#dgs#dgs2#dgs sherlock holmes#tgaa chronicles#tgaa 2#aa#pwaa#phoenix wright#phoenix wright ace attorney#aa meta#ace attorney meta#phoenix wright trilogy#aa trilogy#ace attorney trilogy#apollo justice ace attorney#food#phoenix wright: ace attorney

166 notes

·

View notes