#sippar

Text

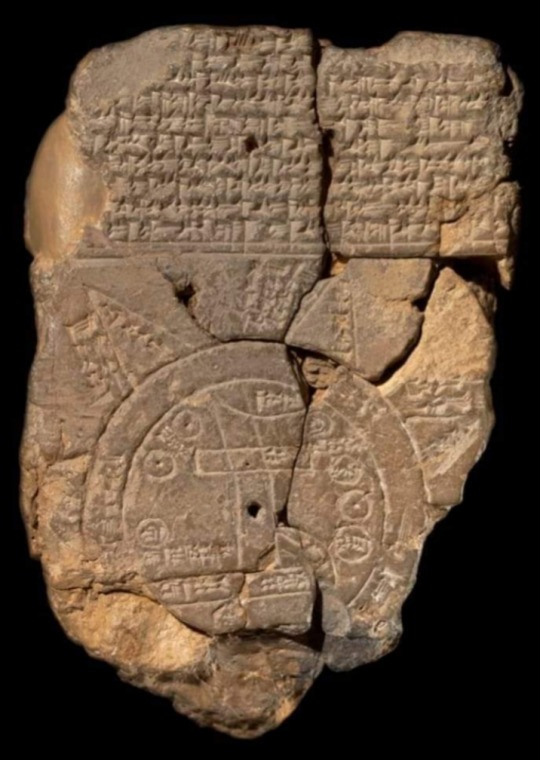

Babylonian Map of the World (6th century BC), also known as Imago Mundi, is oldest clay tablet map written in Akkadian.

The tablet describes the oldest known depiction of the known world.

It was discovered at Sippar, southern Iraq, 60 miles north of Babylon on east bank of Euphrates River.

This map not only serves as a historical record of the region's geography but also includes mythological elements, providing a comprehensive view of the ancient Babylonian worldview.

Today, the Babylonian Map of the World is housed in the British Museum, where it continues to be a valuable artifact for understanding the ancient past.

Details of the map:

1. “Mountain” (Akkadian:šá-du-ú)

2. “City” (Akkadian: uru)

3. Urartu (Armenia) (Akkadian: ú-ra-áš-tu)

4. Assyria (Akkadian: kuraš+šurki)

5. Der (Akkadian: dēr)

6. Swamp (Akkadian: ap–pa–ru)

7. Elam (Akkadian: šuša)

8. Canal (Akkadian: bit-qu)

9. Bit Yakin (Akkadian:bῑt-ia-᾿-ki-nu)

10. “City” (Akkadian: uru)

11. Habban (Akkadian: ha-ab-ban)

12. Babylon (Akkadian: tin.tirki), divided by Euphrates

13. Ocean (salt water, Akkadian:idmar-ra-tum)

#Babylonian Map of the World#Imago Mundi#clay tablet map#clay tablet#Akkadian#Sippar#Iraq#British Museum#history#mythology#map#Archaeo Histories#Ancient Babylon#Babylonia#geography#artifact

540 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is certain, however, is that, for whatever reason, the Urban Revolution began in Mesopotamia and, it seems certain, in the region of Sumer. The earliest cities mentioned are Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, and Shuruppak all of which are located in Sumer. Regarding the various theories as to why Sumer and not elsewhere, Kriwaczek writes that some scholars

see the emergence of civilization as an inevitable consequence of evolutionary changes in human mentality since the end of the last ice age…But we humans aren't really like that; we don't react so unthinkingly. The actual story would have to allow for the everlasting conflict between progressives and conservatives, between the forward and backward looking, between those who propose `let's do something new' and those who think `the old ways are best', those who say, `let's improve this' and those who think `if it ain't broke, don't fix it'. No great shift in culture ever took place without such a contest (21).

Once upon a time, in the land known as Sumer, the people built a temple to their god who had conquered the forces of chaos and brought order to the world. Those people then continued the work of their god and established order throughout the land in the form of the city. The answer to the question of why it happened in Mesopotamia instead of elsewhere can best be found in considering the culture of that particular society. The people of Mesopotamia, regardless of the region or ethnicity, shared the common concern with establishing and maintaining order and, because of their religious beliefs, a near-obsession with control of the natural world. It should not be surprising, then, that such a culture would have been the first to conceive of and construct the urban entity which most completely separates human beings from their natural environment: the city.

#studyblr#history#archaeology#civilization#politics#sociology#ubaid period#uruk period#mesopotamia#sumer#uruk#eridu#bad-tibira#larak#sippar#shuruppak#iraq#kuwait#paul kriwaczek

0 notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babylonian Map of the World, 8th or 7th Century B.C.

The Babylonian Map of the World (also Imago Mundi or Mappa mundi) is a Babylonian clay tablet with a schematic world map and two inscriptions written in the Akkadian language. It includes a brief and partially lost textual description.

The tablet describes the oldest known depiction of the known world. Ever since its discovery there has been controversy on its general interpretation and specific features. Another pictorial fragment, VAT 12772, presents a similar topography from roughly two millennia earlier.

The map is centered on the Euphrates, flowing from the north (top) to the south (bottom), with its mouth labelled "swamp" and "outflow". The city of Babylon is shown on the Euphrates, in the northern half of the map. Susa, the capital of Elam, is shown to the south, Urartu to the northeast, and Habban, the capital of the Kassites, is shown (incorrectly) to the northwest. Mesopotamia is surrounded by a circular "bitter river" or Ocean, and seven or eight foreign regions are depicted as triangular sections beyond the Ocean, perhaps imagined as mountains.

The tablet was excavated by Hormuzd Rassam at Sippar, Baghdad vilayet, some 60 km north of Babylon on the east bank of the Euphrates River. It was acquired by the British Museum in 1882 (BM 92687); the text was first translated in 1889. The tablet is usually thought to have originated in Borsippa. In 1995, a new section of the tablet was discovered, at the point of the upper-most triangle.

Clay, Height: 12.2 cm (4.8 in), Width: 8.2 cm (3.2 in)

Courtesy: British Museum

#art#history#design#style#archeology#sculpture#antiquity#tablet#map#map of the world#babylon#british museum#mesopotamia#text#writing#drawing#euphrates#elam#susa#habban

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Humbaba's appearance ever described in detail in any written sources? When looking online, I keep seeing artists depicting him in very specific ways (head covered in entrails, scaly skin, snake phallus...), but I'm having trouble finding the sources for those same specific details

This is something I've spent quite a lot of time investigating myself last year when I was working on his wiki article. The short answer is that not really, but we can piece something together from the available scraps - and it’s not really similar to the modern standard you're describing. You are definitely looking in the right places for Humbaba information if you found no trace of these traits - only one of them goes back directly to an actual source, and even then it’s less firm than it might seem at first glance.

More under the cut.

The textual sources are actually very lax when it comes to describing Humbaba’s appearance, What is emphasized are his supernatural powers and authority granted by the gods - Wer (they set this guy up like he’s the next arc villain in a shonen in the Old Babylonian version’s Sippar fragments) and Enlil or Enlil alone.

There’s a decent chance he was viewed as largely human-like. Andrew R. George ( The Babylonian Gilgamesh epic: introduction, critical edition and cuneiform texts, p. 144) describes him as “essentially anthropomorphic” though speculates he might have been imagined as tree-like. Multiple considerations regarding Humbaba’s iconography can be found in the articles from Gilgamesch: Ikonographie eines Helden, especially in Lambert’s and Collon’s. Collon essentially just concludes that Humbaba was simply depicted as an unusually tall and/or broad but still largely human-like figure, Lambert notes similarities to the lahmu (so we’re still within the realm of burly hairy men, essentially).

Piotr Michalowski (A Man Called Enmebaragesi, p. 205-206) argues that at least in the standalone narratives Humbaba was essentially a parody of various peripheral “barbarian” rulers. It is perhaps worth pointing out that while the etymology of Humbaba’s name is up for debate, it is clear that it was originally an ordinary personal name, and individuals bearing it appear in administrative texts from the Ur III period before Humbaba the literary character arose.

While myths and the epic itself are lax, plenty of information about Humbaba’s appearance can be found in other genres of texts. This evidence has been collected by George (same monograph as above, p. 146-147). His face was regarded as outlandish, with a bulbous nose and big eyes. There are references to diviners spotting Humbaba’s face while analyzing animal entrails. An artistic representation of this phenomenon is seemingly known from one exemplar, and is the source of “entrails-faced” Humbabas in modern work.

A unique sculpture from Neo-Babylonian Sippar seen above (you can view it from more sides here) is inscribed with a short formula starting with “If the coils of the colon resemble the head of Huwawa”, and has accordingly been described as the visual representation of this statement since the 1920s. Identification as Humbaba has been affirmed for example by Anthony Green in his 1997 article Myths in Mesopotamian Art (p. 137-138 + 150 for a confirmation of the museum number; published in Sumerian Gods and their Representations; you can find it online,it’s worth checking out since it also includes timeless classics like Wiggermann’s Transtigridian Snake Gods and Westenholz’s Nanaya, Lady of Mystery). I’m not actually aware of any parallels, but it’s a cool, striking visual and I personally don’t find its modern fame undeserved.

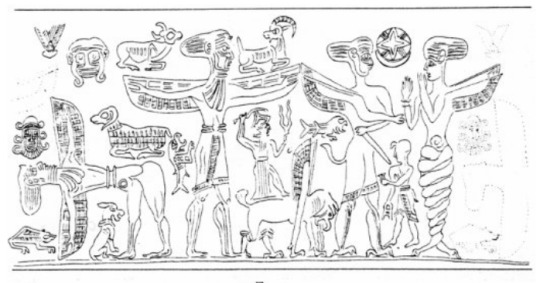

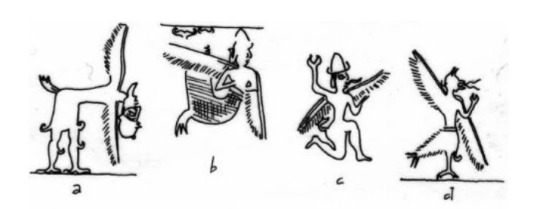

However, it needs to be stressed that it’s not standard. Humbaba’s face is also quite common in visual arts. In fact, it’s so common that Frans Wiggermann (Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: the ritual texts, p. 150) argues that the face came first, with the name perhaps representing a unique sound made by the creature while grinning or laughing (what is this, One Piece?) and only developed into a literary character later. These images served an apotropaic purpose guarding doors (examples have been discovered in situ), appear chiefly in Old Babylonian times, and show remarkably consistent traits, here are some I’ve assembled for the wiki article last year:

Scaly skin doesn’t show up anywhere as a trait of Humbaba’s, as far as I am aware. That’s Tishpak’s thing. However, it is perhaps worth noting that a type of lizard, ḫuwawītum, was named after Humbaba (George, p. 145). This was discussed briefly by Claus Wilcke a long time ago in Humbaba’s entry in the Reallexikon (p. 535); he pointed out the animal was compared to a gecko or what he identified as some variety of agamid. Not sure if anyone ever tried identifying it more precisely with any species of reptile which can be found in Iraq or Syria. Given Humbaba’s apparently outlandish looking eyes my first thought was a chameleon, honestly, but don’t quote me on that, plus note that it seems chameleons were called bargunna (or bargungunna).

As for the other reptilian matter, snake phallus is a part of Pazuzu's iconography (see his Reallexikon entry by Wiggermann, p. 377), not Humbaba's. As far as I can tell, the Humbaba plaque above is naked and shows no such characteristics. Many other possible depictions of Humbaba show him in some sort of kilt with no phallus of any sort in sight (see the numerous seals shown in Collon’s article mentioned above, for instance). I know the snake phallus claim was even on wikipedia at some point - long before my involvement - but it doesn’t come up in any publication about Humbaba I read from within the past 40 years.

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambyses II

Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE) was the second king of the Achaemenid Empire. The Greek historian Herodotus portrays Cambyses as a mad king who committed many acts of sacrilege during his stay in Egypt, including the slaying of the sacred Apis calf. This account, however, appears to have been derived mostly from Egyptian oral tradition and may therefore be biased. Most of the sacrileges attributed to Cambyses are not supported by contemporary sources. At the end of his reign, Cambyses faced a revolt by a man who claimed to be his brother Smerdis, and he died on his way to suppress this revolt.

King of Babylon

Cambyses was born to Cyrus the Great and his wife Cassandane, a sister of the Persian nobleman Otanes. Cambyses had a younger brother named Smerdis, from the same mother and the same father. As early as 539 BCE, when Cyrus conquered Babylon, Cambyses held the position of crown prince. He is mentioned on the Cyrus Cylinder, along with his father Cyrus, as receiving blessings from the Babylonian supreme god Marduk. In Babylonian documents dating between April and December 538 BCE, Cambyses is described as 'king of Babylon', while Cyrus was given the title 'king of the lands'. Cambyses may have been appointed king of Babylon in preparation for his succession to the Persian throne.

Cambyses' reign as king of Babylon was inaugurated by his participation in the Babylonian New Year ceremony on 27 March 538 BCE. The most important function of the Babylonian New Year ceremony was to convey divine legitimization to the ruling monarch. The purpose of this ceremony was to convey divine legitimization to the ruling monarch. The event is described in the Nabonidus Chronicle, but due to the fragmentary nature of the text, it is hard to ascertain what happened. Cambyses is described as wearing Elamite clothing during the occasion and refusing to lay down his arms. This incident may have offended the Babylonian priesthood. It may also have been the reason why his reign as king of Babylon was cut short. After stepping down as king of Babylon, Cambyses remained active in the region, as his name appears in several legal documents from Babylon and Sippar.

Continue reading...

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adramelech - Day 96

Race: Fallen

Arcana: Hanged Man

Alignment: Neutral-Chaos

August 19th, 2024

For such a central and popular concept, ironically, Demons are actually a rather uncommon sight in many translations of the Bible. For the most part, several attestations of demons are relegated to the old testament, with the new testament seeming to focus most on demons in terms of spiritual possession and the like. However, many biblical stories that have demons within them seem to have a few common trends, whether it be references to demons in reference to grimoires or, more strangely, and more rarely, translating gods from other religions into demons. This can be observed in Dante’s Inferno most obviously, with several deities from other religions seeming to be reinterpreted as demons or sorcerers. However, while most can recognize deities from throughout this trend as not originating as demons, some are a bit more obscure, especially when this trend spreads to other books. One such deity of course, is today’s Demon of the Day, Adrammelech: an ancient semitic deity turned demon in Paradise Lost.

While only mentioned briefly in the Book of Kings, Adrammelech is a very curious figure in the world of Biblical study. For those unaware, the Book of Kings is a book situated in the Hebrew bible cut in two parts, including mythologized accounts of real history in order to tell the theologized story of the destruction of the Kingdom of Judah by Babylon. Of course, like many books in the bible, the Book of Kings is long, interspersed between Luke and Leviticus, and its two parts are a rather complicated read overall, but for our purposes, we only need to focus on a mention in Kings 2, particularly in 17:31.

the Avvites made Nibhaz and Tartak, and the Sepharvites burned their children in the fire as sacrifices to Adrammelek and Anammelek, the gods of Sepharvaim.

Interesting to note here is the mention of ‘Sepharviam,’ a word that has contested meanings and is said to be grammatically dual, but is generally agreed to mean the cities of Sippar Yahrurum and Sippar-Amnanum. Both of those cities, notably, were placed just north of Babylon, noted home of sinners and all sorts of nasty stuff, so the antagonistic role that Adrammelech is painted in is rather obvious in its origins already. Also, Anammelech is mentioned in the above passage, but basically nothing is known about said god, so we’ll just brush over that.

Adrammelech’s name meaning ‘Magnificent King’ has been connected to Baal, though it’s commonly believed that Adrammelech and Baal are different beings with simply similar epithets. However, this does tie into the fact that, much like Baal, Adrammelech was a semitic deity whose worship was rather extremely depicted in the Bible. This isn’t the only place Adrammelech shows up, though- the Talmud has its own appearance in it of this god, where it gives us a physical description. To quote the Jewish Encyclopedia,

The Talmud teaches (Sanh. 63b) that Adrammelech was an idol of the Sepharvaim in the shape of an ass. This is to be concluded from his name, which is compounded of "to carry" (compare Syriac ), and "a king." These heathen worshiped as God the same animal which carried their burdens (Sanh. l.c.; see also Rashi's explanation of this passage which interprets "to distinguish," by "carrying"). Still another explanation of the name ascribes to the god the form of a peacock and derives the name from adar ("magnificent") and melek ("king"); Yer. 'Ab. Zarah, iii. 42d.

And all of this, eventually, ties into Adrammelech’s appearance in Paradise Lost, where he finally appears as a demon, and an incredibly powerful one at that, one who fights alongside Asmodeus but is eventually vanquished by Uriel and Raphael. To quote,

Down clov’n to the waste, with shatterd Armes And uncouth paine fled bellowing. On each wing URIEL and RAPHAEL his vaunting foe, Though huge, and in a Rock of Diamond Armd, Vanquish’d ADRAMELEC, and ASMADAI, 365 Two potent Thrones, that to be less then Gods

Finally, as a solid explanation and image for Adramelech, as he barely appears in said poem, we get a description in the Infernal Dictionary, a book by one Collin de Plancy going over yet another compendium of demons, in which he is depicted as a chancellor of hell and among Satan’s cabinet, appearing in the form of a humanoid body with a mule’s head and a peacock’s tail. A rather faithfully adapted design into SMT, funny enough.

Lastly, though, he appears in, drumroll please… the Ars Goetia! YEAH!!!! Unfortunately, his given name is Andrealphus, though everything else is accurate, strange appearance and all. A strange story for an even stranger demon, I must say, but also a fitting start to the countdown to 100.

#shin megami tensei#smt#megaten#persona#daily#if i sound kinda out of it in this one#sorry lol i'm just going thru shit#the school year starting has led to so much baggage that i hadn't yet unpacked

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

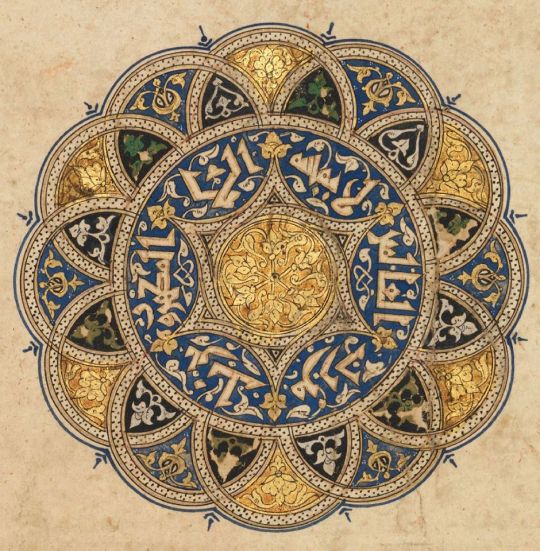

Shamsa (Shamash)

1338 Shamsa means ‘sun’ in Arabic and it is the term used to refer to illuminated roundels.

It says "لا يمسه الا المطهرون تنزيل من رب العالمين" which translates to "Which none toucheth save the purified. A revelation from the Lord of the Worlds."

Quran - Surat Al-Waqiah 78-79

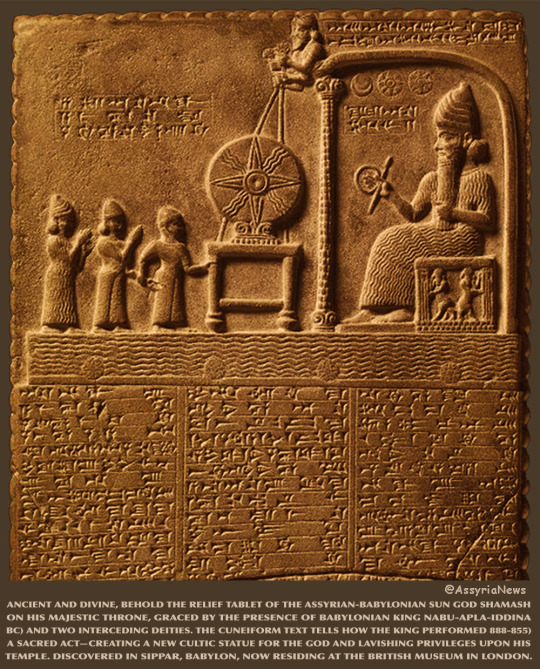

Ancient and divine, behold the Relief Tablet of the Assyrian-Babylonian sun god Shamash on his majestic throne, graced by the presence of Babylonian king Nabu-apla-iddina (888-855 BC) and two interceding deities. The cuneiform text tells how the king performed a sacred act—creating a new cultic statue for the god and lavishing privileges upon his temple. Discovered in Sippar, Babylon, now residing at the British Museum in London.

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cuneiform cylinder: inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II describing his work on Ebabbar, the temple of the sun-god Shamash at Sippar. ca. 604–562 BCE. Credit line: Purchase, 1886 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/321673

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had the sanctuaries of the land Elam utterly destroyed and I counted its gods and its goddesses as ghosts. I destroyed and devastated the tombs of their earlier and later kings. I took their bones to Assyria. I prevented their ghosts from sleeping and deprived them of funerary-offerings and libations of on a march of one month and twenty-five days. I devastated the districts of the land Elam and scattered salt and cress over them. As for the rest of the people, those still alive I myself now laid flat those people there as a funerary-offering. I fed their dismembered flesh to dogs, pigs, vultures, eagles, birds of the heavens and fish the apsû. What was left of the feast of the dogs and swine, of their members which blocked the streets and filled the squares, I ordered them to remove from Babylon, Kutha and Sippar, and to cast them upon heaps.

The nobles and elders of the city came out to me to save their lives they seized my feet and said, “If it pleases you, kill. If it pleases you, spare. If it pleases you, do what you will in strife and conflict.” I besieged and conquered the city. I felled three thousands of their fighting men with the sword. I captured many troops alive. I cut off some their arms and hands. I cut off of others their noses earth and extremities. I gouged out the eyes of so many troops. I made one pile of the living and one of heads I hung their heads on trees around the city I felled fifty of their fighting men with the sword, burnt two hundred captives from them and defeated in a battle on the plain three hundred and thirty-two troops. With their blood I dyed the mountain red like red wool and the rest of them, the ravines and torrents of the mountain swallowed. I carried off captives and possessions from them. I cut off the heads of their fighters and built there with a tower before their city, I burned their young men, women, and children to death. I flayed as many nobles as had rebelled against me and draped their skins over the pile of corpses. Some I spread out within the pile; some I erected on stakes upon the pile. I flayed many right through my land and draped their skins over the walls.

I cut their throats like lambs. I cut off their precious lives as one guts a string. Like the many waters of the storm, I made the contents of their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth. My prancing steeds harnessed from the riding, plunged into the streams of their blood as into a river. The wheels of my war chariot, which brings low the wicked and evil, where bespattered with blood and filth. With the bodies of their warriors, I filled the plain, like grass. Their testicles I cut off and tore out their privates like the seeds of cucumbers. Their blood, like a broken dam, I caused to flow down the mountain gullies. I hung the heads of Sanduarri and Abdi-Milkutti on the shoulders of their nobles and, with singing and music, I paraded through the public square of Nineveh.

— Ashurbanipal, King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire's account of his destruction of the Elamites

The Assyrian conquest of Elam took place in 639 BCE. Elam was destroyed completely, but the Neo-Assyrian Empire itself did not long survive them and was conquered thirty-four years later by the Neo-Babylonian king, Nabopolassar, and Cyaxares, King of Media.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nothing should surprise us with the way things are going. We shouldn’t need influencers to tell us the "truth" because their influence is just another form of control. All we need is the Word of God.

Karen Hunt aka KH Mezek

Sep 15, 2024

We tend to think that nothing has ever been as bad as it is right now. But it might be encouraging (I suppose in a morbid sort of way) to know that people have always thought like this.

Thanks to AI (because although I mostly talk about the dangers of AI, it has a good side, too), a set of 4,000-year-old Babylonian tablets have finally been deciphered. The tablets are believed to be from Sippar, a prosperous city on the banks of the Euphrates, in what is modern-day Iraq.

In its heyday, Babylon was a beacon of knowledge, housing the vast Library of Ashurbanipal, filled with thousands of cuneiform tablets from all corners of the ancient Assyrian Empire. Since childhood, I have been fascinated by stories of ancient civilizations and especially of Babylon with its hanging gardens, written about in the Bible. I loved nothing more on a rainy afternoon than going into my dad’s study, taking a book about history off the shelf, lying on the floor and losing myself in the past.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I have a quick question. Do you know anywhere that would be a good way to find the cuneiform translation for this famous quote: "O Gilgamesh, where are you wandering? You cannot find the life that you seek." From the Epic of Gilgamesh? I'm only now getting into ancient Sumerian as a language.

Hello! This quote isn't Sumerian, and is from the Akkadian-language version of the Epic, specifically the George (2000) translation. In fact, I believe this exact quote is not in the 2000 Standard Babylonian version of the epic, instead coming from an Old Babylonian tablet from Sippar. George puts it as part of a longer speech by the tavern-keeper Siduri at the start of Tablet X, but other sources, like Helle (2021), only have Shamash say it in Tablet IX, and exclude the rest of the speech from Tablet X. (Helle translates the line as "Gilgamesh, where are you going? You will not find the life you seek.") In any case, the Akkadian translation is

GIŠ e-eš ta-da-a-al / ba-la-ṭam2 ša ta-sa-aḫ-ḫu-ru la tu-ut-ta

or, as represented in this recording of George's translation,

gilgameš ê tadâl / balāṭam ša tusahharu lā tutta

Unfortunately my Akkadian cuneiform skills aren't good enough to guarantee an accurate cuneiform version, but you may be able to find the specific signs in the first version above - or maybe someone can reblog with it below!

For more on the tablet of Sippar, see George's description and translation starting on page 272 here. I hope that's helpful!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

During some research, I found an insightful comment on Ishtar's portrayal in The Epic of Gilgamesh versus her portrayal in other sources. I'll need to do the research and check the sources to verify, but I think it has interesting implications. Going to post it below a read-more to help me find it later.

In response to a reddit post about (Fate) Ishtar's feelings toward Gilgamesh:

It’s a bit more complicated than that. Uruk is the city of An (Anu to the Akkadians), and Inanna (Ishtar to the Akkadians), but primarily Inanna. Within the Sumerian political ideaology, a King is the servant of the city god, overseeing the city on their behalf and serving as a representative of the humans before their god.

Within Sumerian myths, Kings of both Uruk as well as other cities actively seek out Inanna’s patronage, and are rewarded with victory in battle, material prosperity, fertility, and long lives. Of the three stories in which the Sumerian Gilgamesh interacts with Inanna, 2/3rds are in a positive manner (with one actually showing a precursor to a common motif between Israelite Kings and the God of Abraham), and the 1/3rd wherein it became negative was related to a jurisdictional dispute (it’s also the precursor to the Bull of Heaven episode in the Akkadian Epic), and ends in an implied reconciliation between Gilgamesh and Inanna.

We then transition to the Akkadian narrative, the Epic of Gilgamesh we know today. This was formed by taking various Sumerian narratives about the life of Gilgamesh and putting them together. Within the most common version (found in Sippar, a city which considered Shamash its patron), we can see a very carefully articulated shift in the view of Inanna/Ishtar. Specifically, we see an alteration of the normative narratives surrounding Inanna, transitioning her from a victim who gains revenge, or an arbiter of justice, to the victimizer in the narratives Gilgamesh uses to justify his refusal, while also expounding her failure to fulfill her divine function as the patron of kings. We also see a very basic shift in perspective, wherein the earlier Sumerian works Inanna is the object of Dumuzid’s desire in their love poetry (even when she initiates), we are instead shown her lusting after Gilgamesh, whose beauty is described in great detail.

Tellingly though, the Epic of Gilgamesh is A. Fairly unique in its vilification of Ishtar, with only one or two other Akkadian (and the derived Babylonian and Assyrian language) language text which depict her in an unabashedly negative manner. The Epic also glorified Shamash as the patron and friend of Gilgamesh, extolling his virtues. As the Epic of Gilgamesh was found in its earliest form in Sippar, I would think that Gilgamesh forsaking the patron goddess of his own city (who oversaw Gilgamesh’s own father becoming a god in his own right) for the author’s favored god may perhaps be a sign of bias.

Beyond that, we can also point out that most of the flaws Gilgamesh points out in Ishtar, in the Akkadian version, are flaws Gilgamesh himself possesses, suggesting Ishtar’s negative portrayal may be less an accurate depiction of views on her, and more a narrative device to make her a suitable foil for the King of Uruk, and a sign of the character growth he needs to undergo.

After I do some research and check their sources, I'll solidify some headcanons about this.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

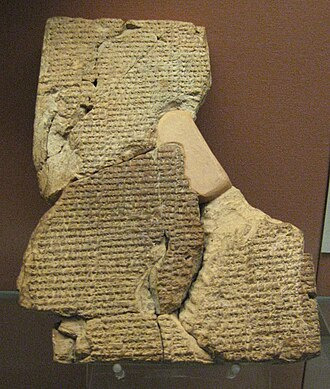

Epic of Gilgamesh IX.9-18 (trans. Andrew R George) and a fragment from a Babylonian tablet ascribed to Sippar.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Old Babylonian Cuneiform Tablet with the Atrahasis Mythological Poem

British Museum, museum number 78943.

Excavated at Sippar, Iraq.

Length: 14.60 centimetres

Width: 12.70 centimetres

17th century BCE

According to the description of the Museum:

Clay tablet; top half; the Babylonian story of the flood. This tablet is one of an original set of three which contained the story of Atrahasis, hero of the Babylonian flood story.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am interested to know about the 4 winds and what is their role in mythology

You’re in luck because while there isn’t much material, it’s fairly easily accessible - by reading Wiggermann’s The Four Winds and the Origin of Pazuzu you can learn 90% of what there is to know. However, since he doesn’t cover the myth(s) involving the South Wind, I figured a brief summary is in order - you can find it under the cut.

All images are taken from Wiggermann’s article, and have been reproduced here for educational purposes only.

The four winds are the West Wind (Amurru; not identical with the god Amurru), the East Wind (Šadû), the North Wind (Ištānu; no relation to the phonetically similar Hittite designation for sun deities) and the South Wind (Šūtu; I’m not aware of any connection to the goddess Sutītu, who was essentially a deified Sutean - ie. “Southerner” - stereotype much like how Amurru was a deified stereotypical Amorite). The names are virtually always translated into English, so I’ll stick to following this convention here.

The South Wind, who has a plenty of solo attestations as a literary character, is usually female, and the other three male; this reflects the grammatical gender of their names. However, there is at least one case where the North Wind is referred to with feminine terms regardless of that. It seems fairly consistent that regardless of their gender the four are treated as siblings, though. We know they shared the same mother but her identity is never specified. Not that unusual, really.

In Mesopotamian astronomy, the winds’ names could also refer to specific constellations: North Wind is Ursa Major, South Wind is Piscis Austrinus, West Wind is Scorpio and East Wind is Perseus and the Pleiades. Note that some of these connections are not exclusive to them; Scorpio or individual stars forming it could be instead associated with Ishara, Ninigirimma, or even Lisin.

While it can be difficult to identify minor deities in Mesopotamian art, the four winds are distinct enough to make this fairly straightforward to researchers. All of them are depicted with wings and windswept hair (of course), but there are additional traits unique to each. The South Wind, as expected, looks feminine and typically has entwined legs; the North Wind is partially theriomorphic (the rest has no animal traits save for their wings); the West Wind is bent over in an acrobatic pose; and the East Wind is, essentially, a “generic wind” iconographically. The oldest example of a depiction of the group is a seal from Sippar from the nineteenth century BCE, which shows the four of them surrounding a weather god, presumably Adad:

Wiggermann based on this attestation suggests that the group might have originally emerged from the theological speculation of Adad’s clergy from Sippar, and that the seal might depict a set of statues displayed at his local temple. Hard to prove, but compelling, imo. However, personified winds occasionally can be found in earlier sources too: one of Gudea’s inscriptions poetically described the North Wind as a winged man, there’s also a seal from roughly the same period showing Adad, his spouse (presumably Shala) and a winged attendant who might similarly be a wind. However, they were not exclusively associated with the weather god - there is also at least one reference to them acting as messengers of Anu instead. South Wind sometimes appears as a servant of Ea, as well.

With time, the South Wind essentially overshadowed her siblings, and could be recognized as an independent wind deity. She eventually lost part of her original iconography: the wings vanished, but a standard horned crown started to appear on her head, indicating stabilization of her status as a deity. She plays a major role in the myth Adapa and the South Wind. The eponymous hero breaks her wing (or both of her wings) with a curse (notably no physical contact occurs), and as a result she stops blowing. Anu therefore summons Adapa to heaven. He plans to essentially deify him, but this doesn’t come to pass because Ea convinced him to refuse any gifts he might receive.

In this article you can learn more about the history of this myth. Most notably, recently a new version has been discovered during excavations at Tell Haddad (ancient Me-Turan). This is relevant to your question since it seems to its compilers it was South Wind who mattered more than Adapa - the narrative is more concerned with her restoration than with its expected protagonist! Anu asks Adapa why did he break her wings, he seemingly does not answer, and instead the focus shifts to declaring a new destiny for the South Wind. Her arrival is said to bring an unspecified disease, which however is also cured by her departure. By breaking her wings, Adapa made her unable to leave, which seemingly meant the disease could not be cured. Interestingly, this might actually be the original form of the myth - in other words, it was originally about the South Wind, with Adapa as a side character, with the switch of importance only occurring later.

Next to the South Wind, the West Wind probably fared the best once the group ceased to be depicted together. He absorbed his brother’s non-human traits, and in the Middle Babylonian period sometimes had the tail of a bird or stinger or a scorpion, and on top of that a set of talons. The acrobatic pose remained consistent, though. Wiggermann thinks that he was subsequently fused with the apotropaic image of Humbaba’s head to create a prototype of Pazuzu, but this remains speculative.

31 notes

·

View notes