#sncc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

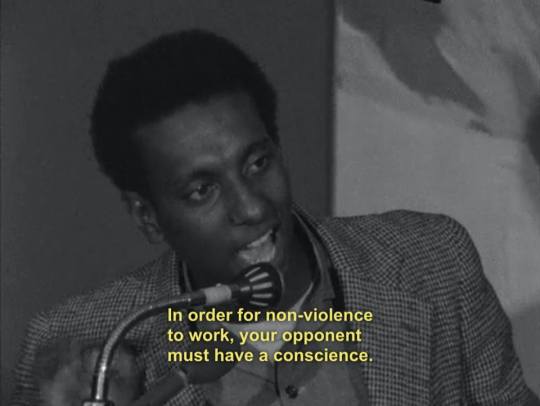

[ID: Two black and white photos of Kwame Ture/Stokely Carmichael, a young Black man, saying into a microphone with a sardonic expression, "In order for non-violence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none, has none." End ID.]

#Kwame Ture#Stokely Carmichael#Pacifism#anti colonialism#antifashism#antifascism#antifashist#antifascist#got tired of seeing the inaccessible version knowing there's doznes of IDs buried in the comments#described images#accessible photos#Black Panthers#Black Power#Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee#SNCC#non-violence#peace#united states#politics#ferguson#From the river to the sea Palestine will be free#free Palestine#free gaza#Gaza#Palestine#BLM#Black Lives Matter#Landback

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

On recent far-left attacks on the Anti-Defamation League

Before we start:

- I think the ADL is wrong about Musk's salutes.

- I think the ADL's Israel advocacy sometimes comes into conflict with their mission in the diaspora. I think their methodologies for data collection and reporting need improvement.

- I think that the ADL is flawed, imperfect and does much more good than harm.

---

Christopher Hitchens put into words what academics used to live by:

"What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence".

The burden of proof is on those making the claim, and the claims of droptheadl.org aren't supported with primary sources or evidence.

For example:

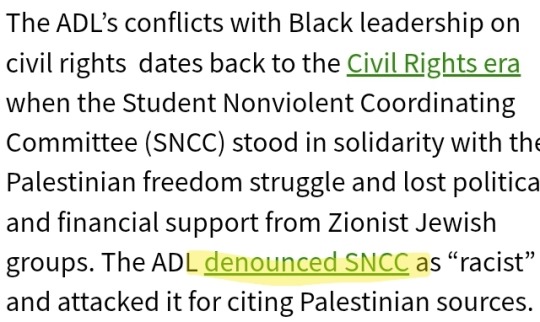

To support its claims about the ADL and SNCC, droptheadl.org offers a link, presenting it as a citation.

This is a link to a Google Books entry. There's no actual text, no citation, no chapter, no page, just the claim that somewhere in this 300-page book exists proof of the ADL denouncing SNCC as racist.

However, that's not in the book. Chapter two talks about this incident in detail, so I read it.

In reaponse to a SNCC newsletter (this is what a primary source looks like!) containing many factual errors about Israel,

...Morris Abram, president of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), summed up their outrage: “Anti-Semitism is anti-Semitism whether it comes from the Ku Klux Klan or from extremist Negro groups

[For those who haven't studied the era: at this point, "Negro" was still the word which the black community preferred. The transition to widespread identification as 'black' got going in the 60s and finished in the 70s. The use of the word 'Negro' here is not a slur. I state this in advance because I know how the illiberal left weilds its willful ignorance]

...

Abram was also careful to echo what the ADL had said: that SNCC’s article put it in the same anti-Israeli trench as the Arab world and the Soviet Union.

That's verifiably, unquestionably true. That's the position SNCC took, because that's where they got their information.

Droptheadl.org lied. This book doesn't say what they claim it says, which is why they didn't quote it or offer a specific citation. Why let facts get in the way of the narrative which makes them feel good about themselves?

The book, which I recommend reading, isn't about the ADL. It's a scholarly examination of the relationships between the wars the Arab world launched on Israel and the US Civil Rights Movement. This requires much discussion of the impact on the complex relationships between black communities and Jewish communities in the US in the context of their views on Israel and Palestine.

It's fascinating. Here's another excerpt illustrating why many Jews saw SNCC as taking an antisemitic turn:

One day in May of 1967, [Stokely] Carmichael and [H. Rap] Brown were in Alabama chatting with Donald Jelinek, a lawyer who worked with SNCC.

Jelinek, who was Jewish, expressed his positive feelings about Israel and his concerns about the Jewish state’s situation in that tension-filled month as war clouds were on the horizon in the Middle East.

“So it was a shock to me,” Jelinek later recounted, “when my SNCC friends mildly indicated support for the Arabs.” Mildly stated or not, their sentiments prompted Jelinek to reply, “But they may wipe out and destroy Israel.”

Carmichael adroitly changed the subject with some humor, and the men began laughing.

Jelinek thereafter overheard Brown quietly singing to himself, “arms for the Arabs, sneakers for the Jews.” When Jelinek asked him what that song meant, an embarrassed Brown explained that he had learned the song as a student in Louisiana. It implied that the Israelis would need sneakers (tennis shoes) to run from the Arabs, who were armed with weapons from abroad.

My qualms with this, my disappointment in and disagreement with both Carmichael and Brown doesn't make me a racist. It doesn't make the AJC or the ADL racist and it doesn't make Jelinek, the Jewish lawyer working with SNCC, a racist or a poor ally.

Zionism is the belief that Jews should have self-determination in their homeland.

Nazism was the belief that racially superior Aryans own the world, should be organized through fascist methods, and that the genocide of the Jewish people was explicitly required because they were the source of all evil and the obstacle to progress.

These are not the same. Suggesting they are the same, as Carmichael did, is morally and intellectually bankrupt. Pointing this out doesn't make me a racist. It makes me literate.

I still own a copy of Carmichael's book, Black Power. Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Ture) was a complex person. Like every other historical figure, he was neither a saint nor a demon.

I can admire a lot about the Black Panthers without falsely claiming that nothing they ever did or said was troubling, poorly reasoned, or bigoted. The world is more complex than that.

There are no saints. Learn this important truth and use it to guide your understanding of the world around you. There are no saints.

Gandhi, for instance, was a great leader for Indian self-rule and a visionary of nonviolent protest. He was also a racist as a young man who said black people "...are troublesome, very dirty and live like animals." Read about his work in South Africa. He was also really weird about sex and slept naked with his grand niece, which we rightly recognize today as sexual abuse. He wasn't a saint or a demon, he was a person.

People are complex and flawed. If you want to understand people, history, and movements, wrap your head around this as keep it with you: People and their movements are complex and flawed.

But the depth of reasoning I see from the illiberal left is "ADL criticized SNCC, so they're Nazis."

No, child. The world is much, much more complex than that. Why did you go to college if you weren't going to learn anything there?

My 14yo is right. US leftists (not liberals, leftists) are allergic to nuance and discard the facts contradicting any narrative which makes them feel good about themselves.

Selah

Deep breath in, slow breath out.

The book is really delves into some of the factors contributing to the deteriorating relationship at the time between Jewish Americans and Black Americans. It points to this essay by James Baldwin, titled "Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They're Anti-White." I urge you to read it, it is a fascinating artifact of its time and place.

And this:

Jews had long advocated for black liberation by, for example, playing a role in the foundation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Jewish support for blacks was well known; as early as February of 1942, the American Jewish Committee published a study titled “Jewish Contribution to Negro Welfare.” Having experienced the sting of anti-Semitism, many Jews believed they were fighting in the same trench against discrimination alongside African Americans. When the civil rights struggle grew to become a mass movement in the 1950s and early 1960s, Jewish moral and financial support was crucial, and Jews were disproportionately well-represented among those whites who lent their support to the cause. Jewish financial contributions to civil rights groups were also significant. Jews even were the subject of criticism from some southern whites for the high-profile role they played in helping blacks win their freedom. All this compounded a sense of betrayal by SNCC that was felt by many Jewish Americans.

It should not be surprising or taken as racist that Jews objected to SNCC's advocacy against Israel's existence and I maintain that any call for Israel to be destroyed is innately, inarguably antisemitic. No other nation endures calls for its destruction. Just the Jewish one.

There was unquestionably tension between SNCC and the entire spectrum of non-black Americans who supported SNCC when SNCC ejected non-black members. From our perspective, decades removed, I can understand both why SNCC members narrowly voted for this AND why non-black members of SNCC were hurt and disillusioned. All of those perspectives were (and are) valid.

When I was an undergrad studying African American Political Thought, we discussed these tensions head-on, using primary sources, and evaluated them dispassionately.

We concluded that there are no villains in this story. SNCC got a bunch of facts wrong about Israel, their staunch Jewish allies were profoundly disappointed, saw hypocrisy in SNCC's position, and said so.

I think that far left Americans overlaid their feelings about a domestic struggle on a foreign one where they don't fit...and then discarded the facts and the complexity which got in the way of a satisfying narrative which made them feel like the good guys instead of forcing them to grapple with an uncomfortably complex reality.

I think that's what the illiberal left still does. It doesn't like complexity, it doesn't like academic rigor, it likes stories it can tell itself about its moral purity and discards facts, complexity, or rigor which threaten their view of themselves as saviors.

The world is complex. People are complex. Movements are complex. Organizations are complex. History is complex. Justice is complex.

The ADL isn't perfect, its leaders haven't been and are not saints or tzadikim, but the good they do for all Americans radically outweighs their failings and I'm going to keep supporting them while yelling at them to do better.

If you're an ADL hater and have any actual evidence and primary sources on racism from the ADL, I really want to see it, because this weak sauce from droptheadl.org doesn't make the case the illiberal left thinks it makes. And they'd know that if they had learned anything in college about how scholarship works and how arguments are constructed.

The illiberal left perhaps forgets how the ADL responded when Trump called for requiring American Muslims to register.

“If one day Muslim Americans will be forced to register their identities, then that is the day that this proud Jew will register as a Muslim. ”

- ADL chief executive Jonathan Greenblatt

#illiberal left#sncc#Adl#leftist antisemitism#black panthers#jumblr#Black Power and Palestine#anti defamation league#elon musk#Nuance#History#Us history#Intellectual honesty#Intellectual integrity

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Violence is as American as cherry pie. If America don’t come around, we’ll burn her down.”

H. Rap Brown

SNCC

Former Chairman

#blacktumblr#black history#black liberation#african history#nodeinoblackbusiness#buy black#h rap brown#sncc#chairman

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

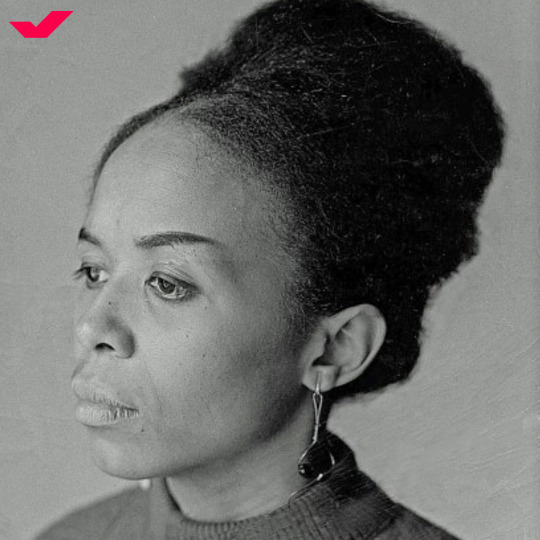

We are saddened to hear about the passing of Dorie Ann Ladner, lifelong voting rights activist. 🕊️🗳️

Ms. Ladner participated in every major civil rights protest of the 1960s, including the March on Washington and the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. She was a key organizer in her home state of Mississippi, with contributions to the NAACP and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In June 1964, she launched a volunteer campaign called “Mississippi Freedom Summer,” with a goal of registering as many Black voters as possible.

We remember and honor Dorie through the words of her sister and fellow activist, Joyce Ladner: as someone who “fought tenaciously for the underdog and the dispossessed,” and “left a profound legacy of service.”

#dorie ladner#dorie ann ladner#voting rights#civil rights#women's history month#mississippi#naacp#sncc#student nonviolent coordinating committee#black voters#black voter#activist#1960s

372 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gordon Parks (photograph), Stokely Carmichael in SNCC Office, (gelatin silver print), 1967, Edition of 15 [Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL. © Gordon Parks / The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, NY]

#art#photography#stokely carmichael#kwame ture#gordon parks#student nonviolent coordinating committee#sncc#rhona hoffman gallery#gordon parks foundation#1960s

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Local Freedom School activist, Gracie Hawthorne, in front of SNCC’s “One Man, One Vote” at Council of Federated Organizations headquarters. - 1964.

Photo: Herbert Randall

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Deep Dive: A history of Black-Palestinian solidarity

#palestine#israel#black history#solidarity forever#malcolm x#angela davis#nelsonmandela#muhammad ali#lauryn hill#free palestine#apartheid#black panthers#sncc#Youtube#afro Palestinian#hip hop#rap#hip hop culture#the coup#boots riley#vic mensa#the roots#blacklivesmatter#black liberation#toni morrison#cori bush#marc lamont hill#ilhan omar

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) and Jamil Abdullah al-Amin (H. Rap Brown) hold a press conference outside of Hamilton Hall during the Columbia University student uprising, April 1968: "The black students of Columbia University, joined by a few members of the black community, have been in Hamilton Hall for 56 hours—more than that now. We have established a cafeteria with adequate stores, all continuously. A physician is in charge of our infirmary. Morale is high."

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Women's History Month 2025 draws to a conclusion, we celebrate the fierceness of Janie Culbreth (later Rambeau), one of the earliest organizers and demonstrators in Albany, Georgia --at a time when the still-coalescing SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) wasn't quite fully organized or entirely clear on its trajectory.

Born to sharecroppers in 1940, Janie and her family (she was the eighth of nine siblings) later left the plantation --receiving considerable threats as they did so, though fortunately none were acted upon. She would later reflect in an interview that, in the 1930s, "When Black people moved off the plantation, white landowners considered it an act of defiance and often falsified documents or made unfounded accusations to force their laborers to remain." She entered Albany State College, originally intending to major in French. Unsurprisingly she endured rigid segregation --it was likely during this period that she made the quiet but unshakeable decision not to endure any further indignities, and she joined the NAACP youth council. Among other acts of passive rebellion, she and several other Black students made a point of visibly drinking from "whites only" fountains, and she also penned editorials to the Albany Herald, expressing disappointment that so many were afraid to speak up against obvious injustices.

In 1962 Janie was arrested while demonstrating at Albany along with at least 40 other students; they had been protesting the arrest of the first five students that tried to integrate the local bus station. While in jail, she and her fellow students received word that Martin Luther King was coming to Albany, which definitely attracted greater national attention; unfortunately Dr. King would later regard the Albany movement as mostly an "early failure," but participants like Janie disagreed; if anything it had proven the ability of thousands of local people to organize, march, and protest without needing to rely on larger outside organizations --or singular charismatic individuals.

After release she and most of the other 40 students were expelled from Albany State, and had to complete their formal education at Spelman College. Her commitment did not waver, however; while at Spelman she also organized a march on Grady Hospital, protesting discriminatory hiring --and patient care-- policies. After graduation she committed full-time to the SNCC, mostly pushing voter registration drives. But as the civil rights movement waned (or at least went quiet for a while!), Janie began to pivot to seminarian work; eventually earning multiple doctorates (Christian Education and Pastoral Ministry) and even found time to at last land that Master's degree in French! For 38 years she would teach for the Dougherty School System and at Darton College. She married Deacon Ralph Rambeau in 1965 and they had three children.

In 1992 Rev, Rambeau founded the House of Refuge Baptist Church. In 2010 the incoming administration at Albany State College hosted a year-long celebration of the students who had been suspended and expelled for participating in civil rights activities; welcoming them back and praising their efforts --Janie was the Founder's Day speaker. For the fiftieth anniversary of the Albany protest in 2012, Rev. Rambeau was honored by the city of Atlanta, with no less than Julian Bond (see Lesson #72 in this series) as the keynote speaker. Rev. Rambeau died on July 30, 2017.

#black lives matter#black history#womens history month#sncc#albany#civil rights#do not comply in advance#teachtruth#dothework#showup

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

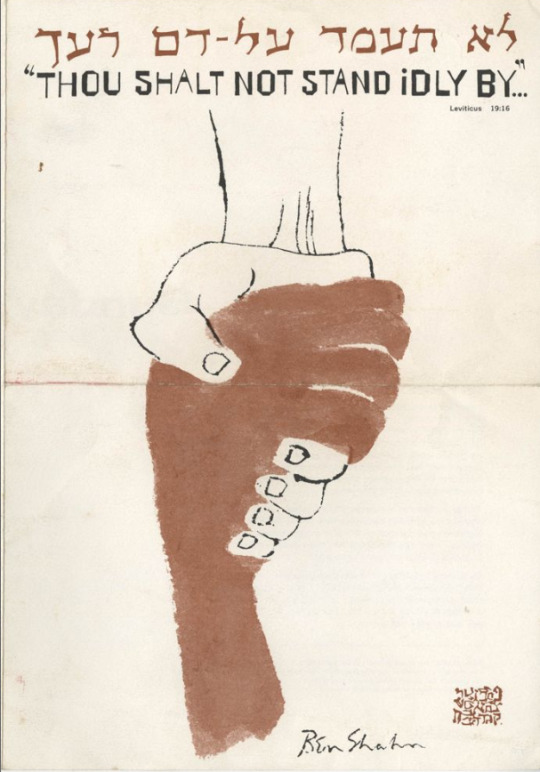

"Thou Shalt Not Stand Idly By…"” Lowcountry Digital Library, Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston, 1965

SNCC invitation

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What comes across in the stories that Myles Horton tells, in SNCC workers’ tales of best organizers, and in the broader literature on organizing is good organizers’ creativity: their ability to respond to local conditions, to capitalize on sudden opportunities, to turn to advantage a seeming setback, to know when to exploit teachable moments and when to concentrate on winning an immediate objective. Sometimes you insist on fully participatory decision-making; sometimes you do not. Albany SNCC project head Charles Sherrod urged fellow organizers not to “let the project go to the dogs because you feel you must be democratic to the letter.” Horton recounted on numerous occasions an experience that he had had in a union organizing effort. At the time, the highway patrol was escorting scabs through the picket line, and the strike committee was at its wit’s end about how to counter this threat to strikers’ solidarity. After considering and rejecting numerous proposals, exhausted committee members demanded advice from Horton. When he refused, one of them pulled a gun. “I was tempted then to become an instant expert, right on the spot!” Horton confessed. “But I knew that if I did that, all would be lost and then all of the rest of them would start asking me what to do. So I said: ‘No. Go ahead and shoot if you want to, but I’m not going to tell you.’ And the others calmed him down.” Giving in would have defeated the purpose of persuading the strikers that they had the knowledge to make the decision themselves. But Horton sometimes told another story. When he was once asked to speak to a group of Tennessee farmers about organizing a cooperative, he knew, he said, that since “their expectation was that I would speak as an expert… if I didn’t speak, and said, ‘let’s have a discussion about this,’ they’d say, that this guy doesn’t know anything.” So Horton “made a speech, the best speech I could. Then after it was over, while we were still there, I said, let’s discuss what I have said. Well now, that was just one step removed, but close enough to their expectation that I was able to carry them along… You do have to make concessions like that.” What better time to make a concession than when you’re looking down the barrel of a gun? Horton presumably knew that he could get away with refusing to be an expert in the first situation and not in the second. Perhaps the difference was that he was unknown to the farmers and was known to the strikers. But one could argue that a relationship with a history could tolerate aberrant exercises of leadership while first impressions die harder. In other words, extracting rules from the stories that Horton tells is difficult. When to lead and when to defer, when to ask leadings questions and when to remain silent, when to focus on the limited objective and when to encourage people to see the circumscribed character of that objective – the answers depend on the situation and are not always readily evident.” – Francesca Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So i made this comment on a really long post about the politics of clothes but I'm not sure anyone is gonna get that far so I wanted to make a post about it so we we can all rejoice in how the coolest shit from American culture is cultivated by black folks. So the reason jeans took off in America is because of SNCC students campaigning in the South. Before this, denim was a tool of the poor working class, and SNCC students were continuing the 50s and early 60s 'Sunday Best' approach to dressing for civil rights activism. However, this was alienating and impractical for bussing thru the south, so SNCC students adopted the dress of southern working class black folk (tho this does not mean that every southern black person appreciated this, however, and should be noted that nuanced conversations were happening around this topic). They found that denim was easy to keep dirt off when traveling thru the south by bus, and overalls often had large pockets to hold pamphlets. (SNCC activists also embraced natural hairstyles at this point, both rejecting their privelege as middle class and because it was a necessity of being on the road without regular guaranteed access to salons and products). It was such a definitive part of SNCC members outfits in the 60s that it became synonymous with activism. Most news at the time usually focused on black activists who performed middle class and respectability to their standards, and thus the white volunteers w SNCC were the ones photographed in jeans, then co-opted by the hippie movement that wanted to capture denims association with activism.

Source: 'SNCC women, denim, and the politics of dress' by Tanisha C Ford in the journal of southern history

#fashion#us politics#us history#fashion history#Activist history#1960s#SNCC#Feminist history#black history#intersectional feminism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#trieyemedia#civilrightsmovement#fannie lou hamer#Mississippi#street photography#landscape photography#canon eos m50#voting rights#Mississippi delta#sncc#civil rights#baptist#mississippisunsetsarethebest

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There is only one thing the man can do to us: kill us. We have accepted the possibility of death, for being killed is inherent in taking revolutionary positions. Too many brothers have taken up the cry: Freedom or Death! If all the current activists are killed, we will die knowing that we have moved history ahead a few steps. We do not despair or fear the future.”

James Foreman

Executive Secretary

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

#blacktumblr#black history#black liberation#african history#nodeinoblackbusiness#buy black#james foreman#sncc

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power, Edited by Lisa Volpe, Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 2022 [© Gordon Parks / The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, NY]

#graphic design#art#photography#catalogue#catalog#cover#stokely carmichael#kwame ture#gordon parks#lisa volpe#peter w. kunhardt jr.#student nonviolent coordinating committee#sncc#a aprp#all african people's revolutionary party#steidl#2020s

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was 13 in 1968 and we lived in South Carolina. I remember being outraged by the killing of three students and the wonding of 20 more by police gunfire. But I was also certainly just a boy.

I do have some pleasant memories of 1968. I felt more accepted and confident in school. I also paid attenton to the news and when I think about that year I remember a pale of sadness about the state of the world.

I don't think that pale has ever lifted.

4 notes

·

View notes