#so why does female sexuality have to always be seen through the lens of men even in feminist circles?

Text

New approach to feminist media discourse: "Scenes such as James Bond seducing Pussy Galore and Thor's abs being touched by Jane Foster all perpetuate toxic matriarchy and the idea that the female gaze is something to be uncritically accepted despite its demeaning effects on men."

#obviously this post is silly#but if you don't get my broader point#I commented on a video addressing female power fantasies and sexist writing disguised as “realism”#I said that i'm sick of how female power fantasies have to be realistic while men can just single handedly take out 70 men in a movie#not have a scratch#and not have it be questioned by the writers or the audience#someone then retorted with "being sexy isn't a female power fantasy. It appeals to the male gaze!'#to which I said#okay#but I still want to be a smoking hot woman#it's more nuanced than that#when guys are bagging chicks and being sauve and built in movies it's not seen as appealing to a female gaze#although in some cases it very much is#like with that thor example#so why does female sexuality have to always be seen through the lens of men even in feminist circles?#the biggest failure of american feminism is its inability to consider more than one female perspective at a time#american feminism#rambles

0 notes

Note

So I know you haven't seen The Boys but I have a topic that I think fits MHA because I got it from that same show. MHA had a totally missed opportunity, I mean, among hundreds of others lol

But then I think about Momo (who is more than a hundred missed opportunities) and her pitiful internship with Uwabami, who was more interested in how pretty they were to sell her products.

It would have been a great opportunity to emphasize the beauty standards held for female pro-heroes. They're clearer there just not said but I know they are because they really like to make the female pro-heroes look as conventionally attractive as possible since the most popular female pro-heroes in-universe are conventionally attractive women. Do NOT get me started on Midnight (I'll save that one for another question though XD)

And also the sexualization, that ties in with the beauty standards since Momo and Kendo were clearly uncomfortable with everything in that internship. And it's extremely obvi that the female pro-heroes are sexualized, even the underage aspiring female heroes. SIGH... if only... if only Momo could have had that opportunity to explore that, because she didn't come intending to use her looks, she came intending to use her brains. How devastating would it be to realize that people only pay attention to how you look? Gosh I wish that could have been something for her.

Yet no, she and the other girls are still sexualized, in fact I think they got even MORE sexualized after this? I mean jeez...

That will always bother me. The sexualization of the girls and what's bullshit on top of that is the extra bullshit argument that the boys are sexualized too? Yeah right.

Now it's true, the boys are seen shirtless a LOT but... it's not through sexualized lens, it's through idealized ones since the boys being so physically fit and demonstrating their strength is a sign of manliness and promoting that masculinity. It's not meant to be sexual, the GIRLS are meant to be sexual, which is sick.

I mean god you don't see the girls emphasizing their strength the way the boys do. Except MAYBE Mirko but I emphasize 'maybe' since she's STILL very sexualized as you said in another post.

The girls are pretty much only there to be oggled whether it's for sexualized means or moe-ified means because even if the girls aren't being sexualized, boys love seeing the girls act like typical waifu-material and I say that because almost ALL the female characters are generally kind, docile and cheerful. Moe traits that appeal strongly to men, and no problematic traits that make them more two-dimensional.

Have you noticed that? Even the 'meaner' girls like Mt. Lady and Toga have moe-ified or sexualized traits. Toga is arguably the most nuanced female character but she's a victim of sexualization too by having her quirk make her naked for God knows why. Mt. Lady from her first scene was doomed from the start since that was all sexualization.

It's like the girls aren't allowed to be even remotely unpleasant or even have any kind of flaws in ways that would make them seem like real individuals. They're pretty much the same kind and caring person with a different face but somehow the same body shape.

Does... that make sense? ^^; I ask that question too much only cuz sometimes I don't always articulate my words right.

Yeah, it's clear that women in heroics are judged as much for sexual appeal than anything else; it makes a bad sort of sense because of the whole 'heroes are celebrities' bullshit.

I think... I think this is something that, in canon, probably got worse as time went on. When Quirks were starting out, and heroes were all just vigilantes, it was about ability, and with AFO around, survival. Like, look at Nana, she's attractive, sure, but her outfit is probably what is best described as 'bog standard hero': it's a bodysuit that covers most of her skin, practical looking gloves and boots, and a cape (has Edna Mode flashback). Beyond the cape (shudders), it's basiclly a costume that exists to just identify her as a hero, nothing more.

I'm not really in the mood to try and pour through hundreds of pictures, but that is both one of the most practical female costumes that I remember and the oldest one.

It makes an insidious sort of sense, even, in the most realistic kind of way: when everything fell apart, and heroes first started being a thing, the public perception was probably, 'Save me! SAVE ME! I don't care if you look like Pennywise the Goddamn Dancing Clown, I DON't WANT TO DIE!!' Nobody cared about outfits, or if you were a hobo or a weirdo, as long as you protected them.

Things settled and heroing became a career, and the costumes became... not standardized, but professional. There was quality behind it, but it was still less 'This is me in particular!' and more an identifier that 'I am a hero!'.

Then, as time passed, and safety became something standard, instead of exciting, the heroes become more... public. There was competition, money was needed to pay off damages, so the celebrity-ness of it all starting kicking into play, and from there it spiraled as certain people got ahead using their appearances, which probably caused a sort of publicity arms race until we have the canon system of ranked heroes and what not.

In a Watsonian sense, it does track. But, let's be honest here, Doyalist is right in this case, Hori wanted to draw sexy women.

You mention Mt Lady, right? Yeah... here's the thing about her. She's sexualized because she's a fetish. I'm not going to tell you what, or go into detail, because that's not what I want to spend time on, but if you don't already know it's not that hard to figure out which one.

The choice of Mt Lady as the first female hero we see, I think the only one in that first chapter, is telling. It's even more telling when the second female hero we see in any real depth is Midnight. And, let's be honest: she's literally just a different fetish. I mean, Mt Lady, in five seconds, shows more depth of character by being glory hungry, and as a living example of the corruption of the hero society, than Midnight does in MHA almost the entire time.

Like, "canonly", Midnight wants to dress like that. She was going to dress more extreme than that, if I'm remembering Vigilantes right, and I think a law was passed that basiclly boiled down to, 'Midnight, no horni?' I went "canonly" because, of course, that's bullshit, and Hori is just trying to explain her everything off by just going 'she's just like that!' I know you didn't want to go into her in depth, but I just would want to say... instead of making excuses for her (non)characterization, I would have loved if she had taken the female students aside before the internships.

Then she could have explained the 'facts of life', that she's like this because it's how she got this far as a hero, and that they'll be expected to do the same. After that, you could go the jaded route, and have her advise them to as the practical way forward, or the 'ra ra heroic' route, maybe have her explain she grew to like her outfit if you have to, but more importantly that things are different now and that they don't need to listen to anyone who tells them to dress down, and they should go their own path, Plus Ultra. But you know, Midnight doesn't get character development.

Really, the Uwabami thing was interesting to me, not because it was good, but because it seemed like it was going to be good, but then dropped it at the last minute.

The way it was set up, how mercenary Uwabami was about looks, how unheroic she was in general, the sheer confusion with Momo, how Kendo was there to point out the flaws for her, the set up was there to talk about about the sexism, and heroic corruption. I think at some point that was supposed to be the start of Momo's character arc, that she was supposed to go through a Hermione like loss of unthinking trust in authority, grow frustrated, maybe rebel a bit, and start coming into her own. Possibly Uwabami could have done something to make her seem... you know, competent in any way as well, instead of literally being a model who (checks the wiki)... finds people sometimes. There was a lot of work put in to undermine Uwabami, to highlight how shallow she seems and how Momo didn't like it, but it just... never went anywhere. Momo just remained obedient, then it ended and she basiclly wasted a couple weeks for nothing.

It really feels like someone pulled the plug there, and I'm curious about who and why, not that we'll ever know.

Ah, yes, the guys 'being sexualized'. I mean, they're attractive, I guess; there's enough fan girl simp threads for Eraserhead's whole... hobo-ness that that's clearly there, but Eraserhead isn't exposing more skin than he's covering, or wearing skintight spandex.

Really, to anyone who thinks its the same, I want to direct them to the Hawkeye Initiative, aka: imagine the male characters in the female character's clothing and/or poses. Just... just do that, and then marvel at how much skin there suddenly is. Or, imagine Izuku going to his internship with Nighteye and the man spends the entire time dragging Izuku to commercials and trying to update his outfit.

Or both!

Just imagine that for a minute for me. Right now. I'll wait.

...

....And, now that I've proved my point...

I just want to highlight something about Toga here: in theory, the idea behind clothes getting in the way of various Quirks makes sense. Quirks are biological, the powers comes from the body, thus it radiates from them, and clothes are directly in the path of that. So Momo being restricted to her body's available surface area, like her skin is a defacto sort of door she chucks items through, tracks with the settings logic. The fact that Tooru is actually invisible, and so clothes would make her noticeable because they aren't makes sense.* The problems I have with that is, A, they're just used in the most stripperific ways possible (people: give Momo more clothes! Hori: gives her a cape, then exposes more skin) and also, and worse, that we have Mirio, who has this exact same kind of problem... but he's given this convenient solution because he doesn't look attractive when naked, so he can use it for comedy on demand.

*Or, at least it made sense until we found out she just... bends the light around her, instead of being physically transparent. This gives her an option to do things beyond being invisible, thank fuck, but... if she bends light around her body, why can't she bend it around the clothes on her body?

Toga, though? Toga adds to her body; she coats herself in her magic identity slime. When it's done, it melts, and it's clear it's extra mass; she doesn't change her body, she disguises it. Out of all of them, it makes sense that she should be able to keep her clothes, since her Quirk just magics her target's outfit out of her magic identity slime along with everything else it's mimicking. They may be wet, sure, or maybe damaged, but she literally layers it over herself. I can't really think of a reason for her to have this specific weakness of 'I can't use this with clothes' beyond 'for the sexy'.

Personality wise, I've mentioned it before, Toga literally is an archetype, the crazy yandere, that's blood themed. Almost every single major female character I can think of is themed, and generally in a sexual way. It gets escalated, I think, because the hero thing means costumes, and branding, and I do think it's so... same-ish, that all the women are caring, because, A, as heroes they're literally mandated to try and take care of people, and B, there's no time spent on them to develop them.

By and by large, the male heros also try to take care of the people around them (I mean, unless you're named Endeavour, then you have other people do it), but it kinda hits different when Kamino Woods is a walking tree and Mt Lady has a skin tight outfit, doesn't it? Moreover, the only actively 'harsh' female hero I can think of is Lady Nagant. Who... is also an assassin, and had recently broke out of prison, so that's not exactly a quality example.

As to not feeling like real people... Uraraka does, since she came for money with her backstory of being poor, and seems to have graduated to wanting to help people just to help people (before Hori began to ignore her for half the series). Again, though, she has some of the largest amount of female screen time as The One True Waifu, so it's not that she's more than the others, she just has that luxury of development where the others can't.

When Hori used to post his notes in the manga, it was easy to see that he (usually) had a grasp on a character beyond what we saw, he just didn't have a chance to show it (Mt Lady, for example, wants fame to get money to pay off the massive property damage bills that she constantly makes since her Quirk doesn't work well in cities; that's actually really humanizing, but it's side material, and not something we can understand just by her jockeying for more good press).

In other words, at least at the start of the story, before Hori began to pump and dump characters to fill one specific purpose and never use again, the characters were actually characters, he just never gave us a chance to see them beyond the most shallow of takes.

But yeah, you're right: in and out of universe, the female characters exist to be females first, and always attractive ones at that, and characters second, if they're lucky to even get to be characters.

#bnha critical#mha critical#ask#Hori's chronic loathing of women#Edna Mode Gave Me Cape Based Trauma for life#Actually I think it was always there but she gave words to it#Please give them some clothes#Momo's Aborted Character Arc#Momo has been nerfed#the hawkeye initiative#Toga's magic identity slime#If you want people to respect them as characters#then spend time DEVELOPING them as characters

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Jessie, hope you're great !

I was wondering if I could have your advice on something ? I really hope I won't be indelicate, formuling my idea here...

See, I might have some particular relation with the idea of sex ; meaning I'm asexual, without being sex-repulsed, although sometimes...

Anyway, I've also always known to find confort with Hestia, her being a being a virgin godess, you know. Therefore, I've been thinking in having a tatoo of her symbol (if you see what I'm refering to ?) ; but I'm not sure now, how that would be, appear, if I would ever come to be in a relationship where I'm confortable enough to have sex...

Is that as awkward as I think it is ? I'm so sorry, my goodness !

I hope you got the idea. Feel free to ignore this, however, by the way. I can sort it out all alone surely ; I just wanted to be sure it wouldn't be some offense or else to Hestia, y'know ?

Thanks, sorry sorry again, have a lovely life ><

Hello, love!

So firstly we have to remember that sexuality is a human concept which does not actually apply to the divine. Divine beings don't have a sexuality and they very likely don't even have physical forms. We as humans can really only understand the gods through the lens of the mortal world which is why we create mythology. There's nothing wrong with that of course but we always have to be mindful of how limiting it is for the gods when we place them in such strict boxes. Its also limiting to us and how we interact and engage with the divine. Your situation is the perfect example. Because you define Hestia as being "asexual" you're now basing all your decisions around that one aspect of her. Its like judging an entire universe on one star. There's so much more to her than just being a maiden goddess. I do understand tho that that aspect of her is very important to you and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that but again we must remember that we're ultimately dealing with divine beings that exist outside of human concepts and human understanding.

Its also important to be mindful of the reasons certain goddesses were given the "maiden" role. I can tell you it wasn't to inform us on their sexuality. The Ancient Greeks had no concept "sexuality" and definitely did not care enough about female sexuality to create roles and mythology for it. So a goddess being labeled as a "maiden" or "virgin" goddess does not automatically mean shes asexual or a lesbian. That wasn't at all what the Ancient Greeks were trying to convey when they created those roles for those goddesses. For Artemis, it was about her representing girlhood. For Athena, its about her being able to exist, lead, and be respected in the masculine realms she ruled, and for Hestia you can read this wonderful passage. So as you can see there's reasons, outside of defining a gods sexuality, for these goddesses to be seen as "virgin" goddesses.

There is also the idea that all the Ancient Greeks meant by "virgin" or "maiden" was that they were unmarried and not engaging in sex with men. So even if we want to try and define the sexuality of these goddesses, you can't pin point it exactly. No one can say with 100% certainty that X goddess is Y sexuality. Its all just opinions.

Now my point of sharing all this with you isn't to tell you you can't see Hestia as asexual. You absolutely can especially if that resonates with you. The purpose of all this is to help you loosen your grip on this strict definition you seem to have. You're so worried of not living up to Hestia's standards (or more like what you think the standards are) of asexuality that its essentially holding you back from really bonding with her. But as you can see from everything I laid out there is no standard because its not even a fact that Hestia IS asexual. So its basically a mental cage you have confined yourself in, but the good news is you have the power to walk out of that cage whenever you wish. Once you realize there is no standard, not even just in Hestia's case but in general. Asexuality is a spectrum and each of us (hey i'm gonna use this as an opportunity to come out as demisexual! woo!) have a different relationship with sex. Like as a demisexual, I only experience sexual attraction after I get to know someone. And even those who identify as asexual don't automatically refrain from sex at all. There are plenty who do have sex. So yeah there is no asexual standard in regards to sex. You do you, my love!

So the summary of my essay is: You don't need to worry! Hestia loves you no matter what. And if you want to get a tattoo get a tattoo! And if you want to have sex then damn it have sex! Always safe sex tho! Protecting yourself and your partners is a very sexy thing to do! <3

#hestiadeity#hestia#hestia deity#divine sexuality#sexuality#asexuality#maiden goddesses#virgin goddesses#artemisdeity#artemis deity#artemis#athenadeity#athena deity#athena

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate it here

Why does he get to appropriate people's race and still have so much access??

I thought impersonation was a crime.

I thought stealing someone's identity was a crime. How is he walking around Freely and taking pictures with hot chicks?😒

THAT SHOULD BE ME😭😭😭

If he is profiting off of his looks he needs to be sued by Hybe IMMEDIATELY.

HYBE SHOULD HIRE ME - If they can over look my gossipy nature and the fact they really can't trust me with any company secrets plus I'll spend all my time staring at Jikook and simping for YoonminhopeJoon🙂

Bapsae aaahhhhh 😏😏😏

To answer your question Barbara, you are not the only confused one when it comes to these labels. We all are.

A lot of people use Bi these days instead of Pan because people find the term Pansexuality confusing and offensive so....

Strange times.

Offensive because some people in the Bi community feel it's a redundant term as to them it means the same as Bisexuality. As such they feel the use of Pansexuality is erasure and invalidating of their own identity.

From what I understand of this ongoing label wars in the community, those who get offended by Pansexuality do so mostly because they do not view trans identity as a seperate unique gender in of it's own but merely as an adjective.

To such, there is no thing as cis boy or trans boy and that a boy is a boy. So being Bi to them means they are attracted to boys( cis or trans) and girls (regardless of whether they are cis or trans)- which is what Pansexuality actually is💀

Here in lies the conflict. Cis women and some people, myself included, see trans identity as a seperate gender identity from cis identity and differentiates between a biological Male or female and a trans Male or female.

As such a boy is not a boy, a boy is either cis boy or trans boy and both are valid.

This distinction is what mostly sets bisexuality from pan sexuality from my point of view.

It's disheartening. Not to mention anxiety inducing and confusing as hell when we can't even agree on basic terms to describe ourselves.

I don't know how conscious BTS are of these conversations and so I've always viewed their use of labels such as boy/girl in their lyrics with utmost fascination given as there are trans genders within their community.

I often find myself wondering what Joonie means when he talks of girls- does he mean cis girls or trans girls? Would he date either or both?

Personally, I view Trans identity as a valid, separate unique form of identity, unique from Cis identity and not just as an epithet.

I date and definitely find trans girls romantically and sexually attractive especially if there's minimum trace of their cis masculinity in them.

But I have friends who identify as lesbians but wouldn't date trans girls regardless of how they present. Yet they wouldn't mind dating a stud or Masculine presenting females as long as they are Cis girls. Talk of transphobia💀

Some girls call me Bi because I like cis and other fems and I'm perfectly fine with it. However embracing that label in Male spaces gives me a lot of headaches because they just assume I'd date any man too.

I have dated fem tops (girly girls who like to be the dominant one in relationships and also prefer to penetrate other girls during sex) who identify as lesbians but have threesomes with gay men💀

I mean as long as they get to fuck those men or penetrate/ top them or so they say and yes I've seen it happen with my two eyes- I have gay threesomes don't judge or tell my pastor😥

I'm going to hell as it is no need to compound it🤧

My ex was like that. She dated a gay guy she was topping and was gonna marry him because her family was pressuring her to get married. The dude was closeted and their relationship was convenient until he came out and lowkey outed her in the process.

When I asked her if she was bisexual she said she didn't have a label because none suited her at the time and that she likes girls regardless of how those girls identify as. So a femboi, andro, trans girls, cis girls, straight girls, gay girls, as long as you feminine she likes.

I'm a bit like that too... minus the topping fembois and gays part💀

If I had a dick it would be useless 🤣

I say all this to say, labels are a bit tricky and a lot of people struggle to find the right fit.

Gay or queer is our go to label.

For the sake of the conversation we having, I'd define being Bi as liking your own gender plus the opposite of your gender but in an exclusive way. Being Bi also means the gender of a person matters to you in your determination of what you find attractive.

However being Pan means you place less emphasis on the gender of the person you are attracted to and more emphasis on the qualities those people possess- really doesn't matter what the other person is if you like em you like em. Which means a person don't gotta be cis or trans boy or girl or other for you to like them. They just have to have a certain quality you find attractive.

Just like you said, you being a girl find gurls attractive too but I don't think you'd be willing to date a girl- cis or trans- a person has to be Male for you to date them. Right?

That exclusivity is what makes you straight. You like one gender to the exclusion of others.

Gays and lesbians like one gender, the same gender, to the exclusion of others.

Bisexuals may like multiple genders, different genders, to the exclusion of others.

Pansexuals like multiple genders but not to the exclusion of others.

If Gender is important to you in determining who a suitable romantic partner is you are either Straight or Bi. If gender is not important to your determination of who a suitable partner is then you're pansexual.

Pansexuals are gender blind🤣

If Pansexuals are bisexuals, there should be a label for the category currently viewed as bisexuals.

When Suga says " I look at personality and it's not limited to girls" I believe he's talking about the qualities he finds attractive in PEOPLE.

When he sings boy or girl my tongue technology will send you to hongkong it carries a similar sentiment. He's saying basically it doesn't matter what you identify as he can make you orgasm under his- rap?

That's pan energy to me. You go pan Suga! BAPSAE AAAHHH🤭

IF he were queer then I'd assume he's more likely to be pan not bi- hypocritically speaking.

But he is NOT QUEER.

SOPE YOONMIN AND ANYSHIP INVOLVING SUGA IS NOT REAL or even likely to be.

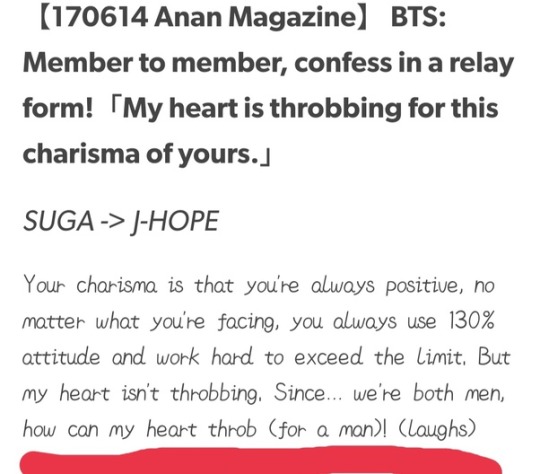

Since we are both men, how can my heart throb for a man. This implies he believes his heart only has to throb for the opposite sex. Yea no he is definitely not bi.

Straight as an arrow this one.

He doesn't find men sexually or romantically attractive. He is not gay or bi and I don't think he wants to be.

I assume he's straight. I do.

And as a straight dude, he's certainly intriguing and I can see how certain actions of his make people queer read him especially in his dominant ships Sope and Yoonmin and Taegi.

But I don't think he goes out of his way to queer code himself.

And I see what you mean by the exaggerated speech. Rappers do trash talk, boast and talk shit in their music but they are also notoriously homophobic with the exception of a few. References of queerness in their lyrics are usually often used pejoratively to slur other rappers etc.

May be I'm too black, gay, and a woman to overlook the misogyny and homophobia that's traveled through Black American hip pop to elsewhere even if it takes on new family friendly labels such as Kpop or BTS.

I don't tend to read hiphop lyrics through non cis non straight non male lens. Unless of course it's from a queer artist but even that there's almost always something internalized.

It's fascinating how people look at a hip hop artist and glean their sexuality from their lyrics....

I'm dozing off. Will read over this tomorrow and add anything I might have missed.

GOLDY

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fuchsia Groan: my (un)exceptional fave

A while ago a friend of mine was asking for people to name their favourite examples of strong female characters, and my mind immediately leapt to Gormenghast’s Fuchsia Groan because it always does whenever the words “favourite” and “female character” come up in the same sentence. In fact scratch that, if I had to pick only one character to be my official favourite (female or otherwise) it would probably be Fuchsia. There are not sufficient words in the English language to accurately describe how much I love this character.

The issue was that I’m not sure Fuchsia Groan can accurately be described as “strong”, and until my friend asked the question, it hadn’t even occurred to me to analyse her in those terms…

Actually this isn’t completely true; Mervyn Peake does describe Fuchsia as strong in terms of her physical strength on multiple occasions. But in terms of her mental strength things are less clear cut. She’s certainly not a total pushover, and anyone would probably find it tough-going to cope with the neglect, tragedy and misuse she suffers through. In fact, this is something Mervyn Peake mentions himself – whilst also pointing out that Fuchsia is not the most resilient of people:

“There were many causes [to her depression], any one of which might have been alone sufficient to undermine the will of tougher natures than Fuchsia’s.”

Anyway, this has gotten me thinking about Fuchsia’s other traits and my reasons for loving her, going through a typical sort of list of reasons people often give for holding up a character as someone to admire:

So, is Fuchsia particularly talented?

No.

Is she clever, witty?

She’s definitely not completely stupid, and her insights occasionally take other characters by surprise, but she’s not really that smart either.

Does she have any significant achievements? Overcome great adversity?

Not really, no.

Is she kind?

Yes. Fuchsia is a very loving person and sometimes displays an incredible sensitivity and compassion for others. But… she can also be self-absorbed, highly strung, and does occasionally lash out at other people (especially in her younger years).

So why do I love Fuchsia so much?

Well, I’ll start be reiterating that I don’t really have the vocabulary to adequately put it into words, but I will try to get the gist across. So:

“What Fuchsia wanted from a picture was something unexpected. It was as though she enjoyed the artist telling her something quite fresh and new. Something she had never thought of before.”

This statement summarises not only Fuchsia but also the way I feel about her (and for that matter the Gormenghast novels in general). Fuchsia is something I’ve never really seen before. On the surface, she fits the model of the somewhat spoiled but neglected princess, and yet at the same time she cannot be so neatly pigeon-holed. It’s not just that her situation and the themes of the story make things more complex (though that is a factor); Fuchsia herself is so unique and vividly detailed that she manages to be more than her archetype. She feels like a real person and, like all real people, she is not so easy to label.

Fuchsia is also delightfully strange in a way that feels very authentic to her and the setting in general (which is particularly refreshing because it can all too often feel as though female characters are only allowed to be strange in a kooky, sexy way - yet Fuchsia defies this trend).

She’s a Lady, but she’s not ladylike. She’s messy. She slouches, mooches, stomps and stands in awkward positions. Her drawing technique is “vicious” and “uncompromising”. She chews grass. She removes her shoes “without untying the laces by treading on the heels and then working her foot loose”. She’s multi-faceted and psychologically complex. Intense and self-absorbed, sometimes irrational and ruled by her emotions more than is wise, but also capable of insight and good sense that takes others by surprise. She is extremely loving and affectionate, and yet so tragically lonely. Simultaneously very feminine and also not. Her character development from immature teenager to adult woman is both subtle and believable. She has integrity and decency – she doesn’t need to be super clever or articulate to know how to care for others or stand up for herself.

Fuchsia is honest. She knows her own flaws, but you never catch her trying to put on airs or make herself out to be anything other than what she is. She always expresses her feelings honestly.

She’s not sexualised at all. I don’t mean by this that she has no sexuality – though that’s something Peake only vaguely touches on – but I don’t really feel like I’m looking at a character who was written to pander to the male gaze (though her creator is male, I get the vibe he views her more as a beloved daughter than a sexual object).

Finally, I find her highly relatable. I am different to Fuchsia in many ways, but we do have several things in common that I have never seen so vividly expressed in any other character. This was incredibly important to me when I was a teenager struggling through the worst period of depression I ever experienced – because she was someone who I could relate to and love in a way I was incapable of loving myself. Her ability to be herself meant a lot to me as someone struggling with my own identity and sense of inadequacy. It didn’t cure my depression, but it helped me survive it.

What am I trying to say with all this?

I love Fuchsia on multiple levels. I love her as a person and also as a character and a remarkable piece of writing. I mention some of the mundane details Peake uses to flesh out her character firstly because I enjoy them, but also because it’s part of the point. Her story amazes me because it treats a female character and her psychological and emotional life with an intense amount of interest regardless of any special talents or achievements she happens to exhibit. She doesn’t fit the model of a modern heroine but neither does she need to – she’s still worth spending time with and caring about.* To me the most important things about Fuchsia are how different and interesting and relatable she is – and how real she feels.

* To be honest, this is part of the point of the Gormenghast novels in general. The story is meant to illustrate the damage that society – and in particular rigid social structures and customs – can do to individuals with its callous indifference to genuine human need. Fuchsia is one of many examples of this throughout the novels. These characters don’t need to be exceptionally heroic in order to matter – they just need to exist as believable people. And despite how strange they all are, they often do manage to be fundamentally relatable.

Why am I talking about female characters in particular here?

The focus on “strong” female characters and the critique against that is pretty widely acknowledged. Growing up, I definitely noticed the lack of female characters in popular media and the ensuing pressure this then places on the ones that do exist to be positive representations of womankind – someone girls can look up to. It’s very understandable that we want to see more examples of admirable female protagonists, given that women were traditionally left to play support roles and tired stereotypes. The problem is that the appetite for more proactive female heroines can sometimes lead to characters who are role models first and realistic human beings second (characters who I mentally refer to as Tick-All-The-Boxes Heroines). It’s not a problem with “strong” proactive heroines per se, but rather lack of variation and genuine psychological depth (not to mention a sometimes too-narrow concept of what it even means to be strong).

Male characters tend not to have this particular problem because they are much better represented across the whole range of roles within a story. You get your fair share of boring worn out archetypes. You get characters who are meant to represent a positive version of heroic masculinity (and now that I come to think of it, having a very narrow and unvarying presentation of what positive masculinity looks like is its own separate problem, but outside the scope of this particular ramble). We don’t usually spend time obsessing over whether a piece of fiction has enough examples of “strong” male characters though, because we’re generally so used to seeing it that we automatically move on into analysing the work and the characters on other terms. And because there are often more male characters than female, they don’t all bear the burden of having to be a positive representative of all men everywhere. They exist to fulfill their roles, and often exhibit more variety, nuance and psychological depth. They are also often allowed to be weird, flawed and unattractive in ways that women usually aren’t (which is a damn shame because I’ve spent my whole life feeling like a weird outsider and yet this perspective is so often told primarily through a male lens).

Tl:dr; Fuchsia Groan is a character who feels like an answer to so many of those frustrations that I felt growing up without even truly understanding why. A large part of why I love her is simply because of how much I relate to her on a personal level. I admire her emotional honesty and her loving nature… But there’s also a part of me that was just so relieved to find a female character who exists outside of the usual formulae we seem to cram women into. She is unique, weird and wonderful (but non-sexualised). Psychologically nuanced and vividly written. She isn’t exceptionally heroic or talented or a high achiever – but she does feel like a real person.

Female characters don’t need to tick all the right boxes in order to be interesting or worth our time any more than the male ones do.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Motherland: Fort Salem (So Far)

Hey so I know I may be a little behind on this one, but I’ve finally binge-watched Motherland: Fort Salem and I’ve had alot swirling around in my head about it for the last few days. This is a little bit of a review and a little bit of rant, but there will be SPOILERS ahead which I’ll try to mark accordingly.

I think the concept for this show is so fucking cool. Really and truly, alternate history in which the witches of Salem made a deal with the Massachusetts Bay Colony to form a military and fight the New World’s wars in exchange for mercy from extermination essentially. So they form a Witch Army. And Army of Witches!! That’s fucking cool. It is. Sadly, I think the concept may be entirely too cool for Freeform.

By that I mean to say that this super cool and entirely edgy idea is just too heady for Freeform to do properly. This idea belongs on HBO or Netflix, because those networks thrive on subject matter like Motherland: Fort Salem. (Sidenote: wtf is it called that? Just name the show ‘Fort Salem’. That kinda tells us everything we need to know about the premise right there in two word. Adding ‘Motherland’ in there just makes it too long and oddly Russian.)

There are just alot of little things about this show that kept it from realizing what I felt could have been some pretty amazing potential. I’ll try to organize those little things as best I can. But the one big problem I had while watching this was that the best thing about this show is it’s alternate history premise isn’t given enough attention.

What I mean is...I’m interested in the show, because I’m interested in what the world (what America) might have looked like if we had a military operated by supernaturally powered women for the past 300+ years. And Fort Salem just doggedly refuses to actually show me that world. The show doesn’t like to explain itself or really explore what it means to be a woman (witch or otherwise) in this alternative America. Most of the show takes place on Fort Salem, a military headquarters of sorts that is mostly strife with political games, attack strategies, training drills, and odd rituals. I have so many questions about this world: Are non-witch women treated differently due to the fact that their country is run and protected by women? There’s a female president in this timeline, so that’s certainly a possibility. If there are male witches as well, why don’t they fight in the same army as the female witches? And since they don’t fight in the main army, what is their mysterious role in this world? We see them making weapons and babies, that’s about it. In 1x5 “Bellweather Season”, the unit goes to a wedding which celebrates a 5 year contract of marriage between the couple. What’s up with that? Why only 5 years? Are they expected to have a child during this time period? if they do have a child are they expected to stay together longer than the 5 years? How many times are the male witches expected to get married? How many children are expected or allowed? Because this show is full of only-children which is statistically different from our own reality. How long are wicthes expected to serve in the military? They’re entire lives? We don’t see any female witches living as civilians at any age (other than Tally’s mother due to tragic circumstances).

What is the source of the witches powers exactly? They’re abilities are sonic/auditory in nature, usually requiring the use of their vocal cords. Why? How? There are brief moments where it seems like sound is less necessary like when Raelle heals, or when the witches use Linking to connect to one another. There is also the use of herbs/drugs to fly, that doesn’t seem to require sound at all.

We’re told the female witches get some kind of power-up or energy boost from having sex (or perhaps just feeding off the sexually energy?) with the male witches. Hence, the Beltane orgy ceremony in episode 1x04. What’s up with that? Does this power-boast only come from sex with male witches or would sex with human men do just as well? Would human men have a less potent effect? And is the power-boost depended on heterosexuality? Because throughout Raelle & Scylla’s sexually relationship no such power-up is ever mentioned.

See so many questions, that the show simply doesn’t feel the need to answer. I understand the desire to avoid bogging down a show with exposition. But their are ways to do exposition right and in interesting ways. Exposition is sometimes necessary, because the more the audience knows about this world, the more rich and detailed, and so close to real is is to them, the more likely they are to be invested in it.

And make no mistake the world and my curiosity about it is what kept me watching.

For much of this first season, the characters don’t have any room to become people. I don’t dislike these characters, but they have yet to really bloom into more than archetypes (Abigail: the legacy, the leader, the overachiever. Tally: the innocent, the hopeful, the lynchpin. And Raelle: the rebel, the cynic, the shitbird)

Alot of time in the early episodes were spent following the same formulate. Raelle runs off, ditching training to go wander around and finds Scylla. Abigail and Tally follow after her, because they need her to do well in training because they pass or fail as a unit. I can not even tell you how many times Raelle causally ditches training, gets caught, gets told how much trouble she’s in, and then doesn’t actually face any consequences at all. She has to do guard duty overnight once. And that was just for being late, not even all the times she leaves in the middle or doesn’t show up for training at all!

I just wish this show focused on different beats in the pulse of this story, and made more of an effort explore this world and these characters through the lens of 3 young women who have just been essentially drafted into the military. Instead of skipping all that training I wish I could have seen so much more of it! That would have been a fantastic way to explain this world’s magic system to the audience! It’s built-in easy action-paced exposition right there! That the show just has no interest in.

And at last, I’ll talk about the show’s main romantic pair, Raelle x Scylla. Sigh. I’m not hardcore against this pairing. I’m really not. But I am frustrated with the way the writers chose to unfold their relationship. We find out early on that Scylla is an agent of the Spree (big bad witchy terrorists), and I hate that. Because then they try to make me ship Raelle x Scylla even though I already know that shit is going to end in pain and betrayal. I cam’t ship something that I already know is built on lies, dude. I just can’t. That could have been a big awesome emotionally reveal in the later half of the season, instead of the dreadful thing I was anticipating from basically the very beginning. I’m as big a fan of enemies-to-lovers as anyone, but not like this. It’s more fun when both parties know they’re enemies, you know what I mean?

Anyway, I know it’s easy to point at the writers/devlopers and say “Man, I would have done this so differently...” but in Fort Salem’s case it’s my biggest take away.

Even from the very first opening scene, where the Spree (Scylla herself) commits a frightening and ruthless act of terrorism at the mall. Okay, big bad introduction for the Spree there. But how about introducing the audience to the world of this alternate history first? Use that awesome premise. Do a cold open, Salem, Mass 1692 Sarah Adler is about to be hanged as a witch until she opens her mouth and changes the world forever. Show me that. Set the stage of history. The villains could have come later. They always do.

All in all, I don’t hate this show ( I know this may have turned out more rant than review, but...) I was just really disappointed by the execution of a premise I felt had great potential. But, it’s not necesarily too late. Season two can still course correct and pull us into this world outside the fort’s walls, and manage to bring the characters into their own as they find their way back to one another. I’ll keep watching, because if this show did anything for me, it made me curious.

#motherland fort salem#freeform#the unit#bellweather unit#abigail bellweather#raelle collar#raelle x scylla#tally craven#sarah adler#salem witch trials#witch tv shows#spooky season#tv rant#tv review#thoughts on fandom#thoughts on fort salem#fort salem#motherland fort salem s1#motherland fort salem season one#tv recommendations

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

i feel like half the time ppl on this site have discourse arguments bc ppl have entirely different understandings of what the subjects are. every time i see someone talk about gendered "socialization" they have a different description of what it is and what it implies.

so throwing that terminology away while discussing the same issue....there are 2 factors at play, imo. gender and sexuality. ppl tend to focus only on gender, but i think sexuality has a lot to do with it also.

the phrase "female socialization" or "male socialization" are particularly bad, not bc they aren't trying to convey real experiences, but bc they create a false dichotomy and fail to communicate properly what those experiences are by forcing a gender label onto people who don't always match it.

the problem isn't so much that society forces a gendered "socialization" on groups of people, but rather that socialization teaches groups of people it assumes to be binary that they must be appealing to men, and how to. this applies to both "male" and "female" socialization.

what we dub as "male socialization" is more commonly referred to as toxic masculinity. it's the pressure to adhere to standards of "manliness" that only other men care about.

what we dub "female socialization" is the pressure for women to appear attractive to men, and the oppression that comes from failing to do so.

this is why sexuality plays a role, and why there is a false dichotomy and equivalence made between the two ideas.

i think it's very common for transmasc people to relate to the idea of "female socialization," because even understanding their gender, if they still like men, the pressure to appeal to men's attraction is still the same, as is the oppression for not holding the feminine standard that straight men hold for them; the same as many gnc cis women might experience, because society only teaches how to appeal to straight men, not how to appeal to men as an otherwise queer person.

and this does NOT mean that "logically, transfem people must experience male socialization then!" because what is referred to as "male socialization" is not equivalent to the experiences referred to as "female socialization." a transfem child who doesn't relate to being a man is not going to feel the pressured drive to uphold standards of masculinity. in fact, they are far more likely to absorb "female socialization" and internalize the expectations put on women to appeal to men if they're also attracted to them, and sometimes even if not, because femininity is most often defined by heterosexuallity.

the "socialization" concepts are real things, but because they're essentially the same phrase with binary genders swapped out, it creates this false idea that they're the same thing but for afab and amab people. that's so completely not true.

and they're not inherent either, which is also where i think sexuality comes into play.

i, personally as a person who was afab, did not suffer so called "female socialization" the same way other people did. this is because I'm lesbian, and I've never particularly cared about how men find me appealing. even under comphet, i really never felt that as a motivating pressure. the social repercussions for not adhereing to that standard of femininity have never felt as scary or harsh, because i simply do not care what men think of me.

it's not an inherent thing. it's a COMMON experience, but it's very specific, too. and we need to ditch the shitty, binary phrasing, because it really has nothing to do with agab, and everything to do with your relation to men and how you want them to view you.

"female socialization" as a concept honestly covers anyone who wanted to be seen as attractive by men and/or suffered the repercussions of not being so, (and more complicatedly, wanted to be seen as feminine and suffered the social understanding of femininity through the lens of the straight male gaze, regardless of sexuality.) this can include transmasc AND transfem people, and it can include many afab people, but not necessarily all, and certainly not to the same extent for all.

"male socialization" as a concept covers people who wanted to be seen on an equal, masculine level as other men, even to an unhealthy point. this can, in fact, cover transmasc people as well as cis men, but generally tends to exclude transfem people.

and there is the false dichotomy, and why the terms are so incredibly bad - they're not exclusive. someone can experience both of them at once. someone can experience neither. and the "male" and "female" split in the concepts is not only binary, it's based on heteronormativity as well.

the "socialization" queer and trans people experience is not as simply categorized as it is for cishet people, who no doubt created these terms. what we get told growing up is aimed at cishet children, and not being cishet ourselves, we internalize their messages entirely differently, even when we don't fully understand ourselves yet, even when society makes false assumptions about us.

and i think we would be 10x more productive having these discussions on "socialization" if we understood that the terms are really not useful, and that people who use them largely don't always mean to communicate the same ideas.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gothic Literature- Drawing on feminist readings of Gothic Literature analyse the way in which Gothic Literature has responded to the changing roles of women in society.

The Gothic genre has always been viewed through the lenses of psychological thriller or horror. The strange and uncanny of it all causes the unease that we as readers have come to love. But what is it that causes such unease and why do the writers of such a genre become so entranced by it? The stories of The Castle of Otranto, Carmilla, Rebecca and Twilight are excellent in their own right. Yet the path of most fruition in understanding these stories is through the lens of feminism. Through it one can begin to unravel the role of women throughout history and it’s ever changing presence. As such this essay will establish what each of the stories define as the roles of women beginning with The Castle of Otranto and how Hippolatia is depicted as Walpole’s ideal women as opposed to Isabella or Matilda who are naïve and do not understand their role in society. Next, the essay will look at Carmilla and how Le Fanu’s vampire is the embodiment of the threat of feminism in the era and the freedom to womanhood that Carmilla represents by removing the male from sexual relations. The story of Rebecca will look at the twentieth century woman and the breakdown of norms and Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight will look at how this breakdown has shaped the modern role of women.

The Castle of Otranto (Walpole, 2001) written in 1764, follows the story of Manfred, the lord of the Castle and his family. Walpole’s novel indicates the dominant, infallibility of men as opposed to their “damsel in distress” (Siddiqui, 2016) counterparts. In the nineteenth century, women had no rights and were considered second class citizens, and received “unworthy inheritance, such as bible, books and household goods” (Gilbert and Gubar, 2006). Hippolita, Manfred’s wife, is a prime example of this since she is so willing to accept divorce from her spouse simply because he said so. Walpole (2001) explains in the novel that “a bad husband is better than no husband” and without pleading or begging, Hippolita accepted the fate her husband wrote for her. In fact, she has no place to argue- she has submitted herself to her husband “physically, economically, psychologically and mentally” (Siddiqui, 2016). Due to this, Hippolita is the exemplary form of womanhood in The Castle of Otranto. She accepts her divorce and, in the novel, explains that she will “withdraw into the neighbouring monastery and the remainder of life in prayers and tears for my child and –the Prince’’ (p.90-91). She does not fight for her rights and gives herself to God because that is what is expected of her, something she tries to pass on to Matilda and Isabella when she explains, ‘’It is not ours to make election for ourselves; heaven, our father and husband must decide for us’’ (Walpole, 2001). This further highlights Hippolita’s ideology that the men of the family and in the lives of the women have priority in life, being dependent and subservient on these men is what is expected of women and hence the role of women should be of servitude to their husbands and fathers.

Matilda and Isabella are younger than Hippolita and have less of an understanding of how they should be dependent. Although Hippolita tries to explain to them, Matilda only understands through her own experiences. As a female child of Manfred, she is introduced as “a most beautiful virgin, aged eighteen” (Walpole, 2001) as if to say those are her only qualities- she is good looking and at the age to marry. However, she is still a woman and therefore “equally dismissed since under the prevailing system of primogeniture only males could be heirs” (Ellis, 2010). She is neglected by her father and even when she tries to comfort him after Conrad’s death she is met with “cruel emotional attitude” (Putri, 2012). Walpole (2001, p.21) writes:

“She was however just going to beg admittance when Manfred suddenly opened his door; and it was now twilight, concurring with the disorder of his mind, he did not distinguish the person, but asked angrily, who it was? Matilda replied trembling, “my dearest father, it is I, your daughter”. Manfred stepping back hastily, cried “Begone, I do not want a daughter”, and flinging back abrupty, clapped the door against the terrified Matilda”

Due to this, Matilda must accept that due to her gender she is expected to be treated in such a manner and her father will not give her any affection. Putri (2012) writes that for Manfred- “it would be better that Matilda be neither seen nor heard.” (p.7). Isabella who is Conrad’s fiancée is forced by her father to marry Manfred after Conrad’s death. She too is a victim of the patriarchal society in which she lives. She must marry Manfred even if there is no love there and only after Matilda’s death does Theodore accept her, and she becomes Lady of the castle. Even after this, the assumption would be that she becomes subservient to Theodore as opposed to her father. Therefore, the role of women in The Castle of Otranto is subservience to the men in their lives and this is their calling.

In contrast, Le Fanu’s Carmilla (2005) originally written in 1897 is the story of Laura and Carmilla, two young women who do not obey such a patriarchy and are in a lesbian relationship. Before Carmilla, vampires were predominantly male such as Lord Ruthven from John William Polidori's The Vampyre (2017). Signorotti (1996) argues that Le Fanu’s choice of creating a powerful female vampire was because it “marks the growing concern about the power of female relationships in the nineteenth century” since this was the time “feminists began to petition for additional rights for women. Concerned with women's power and influence, writers . . . often responded by creating powerful women characters, the vampire being one of the most powerful negative images” (Senf, 1988). It is for this reason that Carmilla is depicted in such a frightening and sensual way by Laura. She represents the allure of women as sexual beings with fangs dangerous enough to topple the patriarchy that the women in Walpole’s novel held to such esteem. Laura recounts one night that:

“I saw a solemn, but very pretty face looking at me from the side of the bed. It was that of a young lady who was kneeling, with her hands under the coverlet. I looked at her with a kind of pleased wonder and ceased whimpering. She caressed me with her hands, and lay down beside me on the bed, and drew me towards her, smiling; I felt immediately delightfully soothed, and fell asleep again. I was wakened by a sensation as if two needles ran into my breast very deep at the same moment, and I cried loudly. The lady started back, with her eyes fixed on me, and then slipped down upon the floor, and, as I thought, hid herself.” (Le Fanu, 2005)

Carmilla is liberating her fellow woman from the grip of a male dominated life and the needles of freedom cause her pain from the familiarity she initially grew up with into an unknown but free world where their union without a male partner gives them liberation from male authority.

The exclusion of the man is further shown by General Spielsdorf’s recount of when he tried to catch the vampire that was causing his niece, Bertha, to become ill. He watches from the door as he saw “a large black object, very ill-defined, crawl, as it seemed to me, over the foot of the bed, and swiftly spread itself up to the poor girl's throat.” (Le Fanu, 2005). Carmilla takes away the male inclusion and leaves him a voyeur to a union that is beyond the heterosexual norm. This is a freedom from the patriarchal society that has ruled over women for centuries into a freedom over their own lives both physically and psychologically. Signorotti (1996) explains that “Le Fanu allows Laura and Carmilla to usurp male authority and to be stow themselves on whom they please, completely excluding male participation in the exchange of women.” (p.607). This exchange symbolises the change in normality. Not only are women becoming independent from males for their living needs, they are also becoming free in their sexual needs. Where The Castle of Otranto focused on the ideal women being subservient and dependent on the male in one’s life, Carmilla focuses on the threat of women to oppose Walpole’s standard of servitude to the patriarch that controlled their lives and of their bodies as factories for new male heirs. Carmilla is the free women that Walpole’s characters never dreamed of.

Rebecca (Du Maurier, 2007) was written in in the twentieth century (1938) and is the story of the narrator’s marriage to Maxim de Winter and the subsequent flashbacks to her time in Manderley where she learnt about her husband’s first wife Rebecca and her lingering presence even after her death. Nigro (2000) argues that although the common assumption about Rebecca is that she is manipulative and convinced everyone she is flawless, she was justifiably murdered according to the second Mrs. de Winter. “What if, however, Maxim is the one who is lying, and Rebecca was as good as reputation held her, if his jealousy was the true motive for her murder?” (p. 144). Furthermore, Wisker (1999) points out that Du Maurier is known to have unreliable narrators. Therefore, finding the truth behind Rebecca’s character, flawed or perfect, becomes difficult. This difficulty blurs the lines between gender roles and conformity. The superiority of men is shown by Mrs. Danvers’ comparison of Rebecca as a man, “"She had all the courage and spirit of a boy, had my Mrs. de Winter. She ought to have been a boy, I often told her that. I had the care of her as a child. You knew that, did you?" (Du Maurier, 2007) showing the importance of being a “man” at the time and how they were seen to be superior. When the audience finds out about Rebecca’s imperfect character, one of her detrimental features is that she is promiscuous and why Maxim killed her. Maxim’s murder could therefore be because he was constrained by what people would think if his wife was expose to be a “harlot” and murdered her to uphold the principles that Walpole emphasised- something he cannot go against in his social circle, whilst Rebecca herself was trying to be as free as Carmilla and trying her best to live a happy life unconstrained by social norms and patriarchal glances. The role of gender and women becomes blurred in Rebecca as these roles begin to breakdown and become synonymous to both genders.

Maxim’s attitude towards his new wife is almost paternalistic, treating her like an immature girl referring to her as “my child” and “my poor lamb” (Du Maurier, 2007). Where Mrs de Winter wants to become more mature, Maxim tries to keep her away calling it "not the right sort of knowledge" (p. 223) and telling her “it’s a pity you have to grow up” to block her from gaining the maturity that she craves. As a result, Mrs de Winter becomes trapped in a purgatory between maturity and upper-class standards and immaturity and the life she has come from. This entrapment is what the patriarchal norms establish, the damsel that must be guided by a firm male hand because of her ignorance as opposed to the woman being on equal footing to the man and someone who can take care of themselves. It is this standard that the narrator is held to and is also the standard Maxim held Rebecca to and subsequently murdered her because of. The shame from having a free woman as a wife is what led him to his crime. It is for this reason that the ultimate villain of Rebecca is in fact the patriarchal system in which the characters are confined. Wisker (2003) argues that the aristocratic setting of Rebecca “was to represent an unease at the configurations of power and gendered relations of the time.” Pons (2013) furthers this argument and explains that “the ultimate gothic villain is the haunting presence of an old-fashioned, strict patriarchal system, represented by Maxims mansion, Manderley, and understood as a hierarchical system.” This configuration of patriarchy established in the eighteenth century by Walpole is that of servitude for women and dominance for men. However, in an era where women have more power and have freedom as expressed in Carmilla suggests that these roles are becoming unfulfillable and it is because of this system that the characters are led to “hypocrisy, hysteria and crime.” (Pons, 2013). Thus, the role of women as a strict social etiquette breaks down and although they are treated still as subjects, the shift in power to give women their freedom is evident.

Twilight (Meyer, 2012) written in 2005, follows the story of Bella Swan who falls in love with a vampire and the subsequent life they have together. However, it is subject to great controversy especially because of Bella herself. She seems to conform to female roles that are more akin to Hippolita than Carmilla. Rocha (2011) argues that “Bella illustrates female submission in a male dominated world; disempowering herself and symbolically disempowering women.” She sees herself in a negative light that is incapable of doing anything herself and is totally submissive in nature becoming a pawn in the life of the men of her life. Mann (2009) argues “When Bella falls in love, then, a girl in love is all she is. By page 139 she has concluded that her mundane life is a small price to pay for the gift of being with Edward, and by the second book she’s willing to trade her soul for that privilege” (p.133) and hence has a Hippolitaian quality of sacrifice for the pleasure of men and hence develops nothing about herself. Mann (2009) continues to say that “Other than her penchant for self-sacrifice and the capacity to attract the attention of boys, Bella isn’t really anyone special. She has no identifiable interests or talents; she is incompetent in the face of almost every challenge...When she needs something done, especially mechanical, she finds a boy to do it and watches him. (p.133) This leaves Bella as a “damsel-in-distress” (Rocha, 2011) where Edward becomes her saviour. Thus, the role of women in Twilight seems to be that of a possession to enhance the male being.

It could however be argued that Twilight contains a relationship that female readers can relate to in its ability to show the “women’s powerlessness and their desire for revenge and appropriation.” (Jarvis, 2014) and how the heroine proves to the hero ‘‘their infinite preciousness’’ (Modleski, 1982) bringing the hero to contemplate, worry and obsess over the heroine in a way that the female reader can share “the heroines’ powerlessness and accompanying frustration.” (Jarvis, 2013). This leads to what Nicol (2011) explains is the ‘‘complexities of female sexuality for women in the twenty-first century’’ in so far as it provides a ‘‘socially sanctioned space in which to explore their sexual desires.” These desires are evident in Bella and Edward’s first kiss, that Bella describes:

“His cold, marble lips pressed very softly against mine. Blood boiled under my skin, burned in my lips. My breath came in a wild gasp. My fingers knotted in his hair, clutching him to me. My lips parted as I breathed in his heady scent.” (Meyer, 2005, p. 282)

This sexual tension is introduced earlier in the book where Bella is told that ‘‘Apparently none of the girls here are good-looking enough for him’’ (Meyer, 2005 p. 19). Jarvis (2014) explains that because of this any “female who secures the inaccessible Edward will rise in the esteem of her community” and since she is claiming him, someone who thinks of herself as “ordinary” (p. 210) the excitement for both Bella and the reader who is caught in this sexual act- almost participating in it- is why the sexual nature of the book is so enticing. Therefore, although Bella can be seen as holding the values of Hippolita, the Twilight saga speaks volumes in its showing of the complexities of the social code that twenty-first century women must abide by. They are expected to be as obedient as Hippolita whilst being as sexual desirable as Carmilla or Rebecca. Bella’s metamorphosis from the ordinary human to the alluring vampire symbolises this. Women’s roles therefore have changed to give them more freedom, but they are still expected to behave like Hippolita when the “freedom” they have been given.

In conclusion, the role of women and their identities have changed over the centuries. Walpole’s eighteenth-century idealism was that of the subservient woman that belonged to the patriarchal figure in their life in order to produce a good heir. The nineteenth century however became the start of the empowerment of women and much of the anxiety in Carmilla is her powerful nature as a woman to do as she pleases, removing the man and the patriarchy from Le Fanu’s world. She is thus depicted as a vampire- alluring and deadly- much like giving freedom to women who cannot control nor be trusted with the power they could be given. Rebecca leads to the twentieth century where the woman has been given some freedom to do as she pleases so long as it is under the watch of a man. Maxim’s murder and subsequent second marriage where because he could not control his first wife. The twenty-first century culmination of these roles comes in the form of Twilight where the heroin seems bland on the surface but actually shows the metamorphosis of womanhood through the centuries from that of a second-class servant to the ultimate freedom away from the patriarchy that Le Fanu’s Carmilla started centuries ago. As a result, the role of women has been fluid through the years. The ultimate goal of feminism is to have equality and the books that have been mentioned show that equality can only be achieved if any form of patriarchal culture is removed- a feat that has yet to be conquered.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So let’s talk about them cherubs.

I think it’s no secret that Calliope and Caliborn have always been deeply gendered characters in Homestuck, but (beyond fanart and enthusiastic headcanons) I personally haven’t seen a lot of engagement with their characters on that level. The most comprehensive readings of Calliope and Caliborn that I’ve seen have always been through the lens of metatext (Calliope and Caliborn as fandom avatars) or religion (Calliope and Caliborn as Gnostic figures).

With that in mind, I want to talk about the ways in which Calliope and Caliborn are gendered in Homestuck, and offer my own amateur reading of Calliope as a trans allegory.

Full disclosure, I love the epilogues, but I won’t be engaging with them here -- I view them as extracanonical, which is to say, I’d like to talk about them and their own presentation of Calliope’s story in another post.

Also, it’s Homestuck, so, you know. Sex, death, violence, and bigotry under the cut:

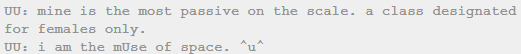

If we’re to read Calliope as a trans allegory, then we don’t need to look very far for evidence, because the text is very straightforward in suggesting it.

Almost as soon as we meet Calliope in the flesh for the first time, we’re confronted with the bleak reality of her desire for a more feminine embodiment:

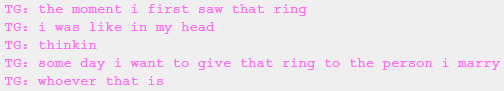

'Callie Ohpeee’ serves as an aspirational figure for Calliope on multiple levels. Most obviously, she’s a vehicle for Calliope’s self-insertion into the wider world of paradox space and the alpha timeline (i.e. her self-insertion into the story of Homestuck); Callie Ohpeee is able to freely and directly interact with the elements and characters of the story that Calliope adores, while Calliope cannot. Somewhat less obviously, Calliope’s trollsona also serves as a way for her to imagine herself in non-caliginous relationships (which she desires on some level, but she feels she has been denied by her biology).

However, Calliope’s trollsona isn’t just a vehicle for her relationships and engagement with other people. Calliope’s trollsona is also key to the way in which Calliope desires to relate to herself.

Calliope desires to be attractive and feminine for her own sake: she desires to be beautiful and pretty, and her trollsona serves as the vehicle by which she satisfies this desire.

Calliope’s trollsona is quite literally her idealized feminine self, and so her relaxing “solo cosplay” sessions bring nothing more to mind than a trans woman privately enjoying a feminine presentation in the closet, as many trans women have. Her costumery and face paint imply clothes and makeup, and Caliborn takes on the role of a patriarch or patriarchy that tries to control her.

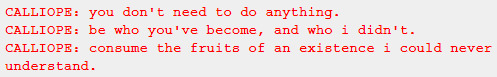

Ultimately, though, Calliope’s embodiment desires are cosmically validated by the unfolding drama of paradox space. Calliope is tormented by the apparent fact that she isn’t and can’t be Callie Ohpeee, but nevertheless, she successfully inserts herself into the lives of the alpha kids and the unfolding of the alpha timeline, forms the kinds of relationships that she wants, and receives the regard that she wants. She dies and takes on the form of her trollsona in the dream bubbles, and even when she’s physically reborn as her cherub self, she’s still “Callie” to Roxy, a meaningful nickname that goes basically unspoken.

Pretty straightforward, right? A trans girl learns that she and her body aren’t unlovable, makes friends and forms bonds as her true self, and escapes the reach of the forces that once abused her.

FEARFUL SYMMETRY

Before we can close the door on a trans reading of Calliope, we also have to consider Calliope and Caliborn as a pair, and not least because the two of them literally share the same body. Fair warning, we’re only going to get more speculative (and more indulgent) going forward.

Calliope and Caliborn are presented, at least superficially, as absolute and dichotomous opposites. They are two spirits that cannot coexist at once within the same body; their respective attitudes and temperaments couldn’t be any more different, and they are, of course, Muse and Lord: quintessentially passive and quintessentially active.

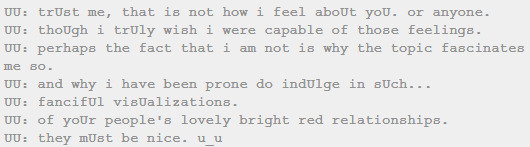

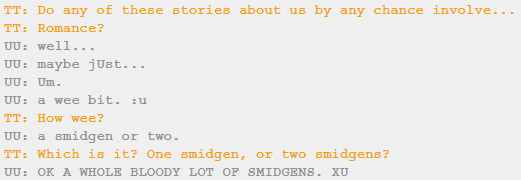

However, Calliope and Caliborn aren’t so different as one might think. Despite Caliborn’s violent protestations to the contrary, they share key characterizing interests in the likes of shipping...

...and art:

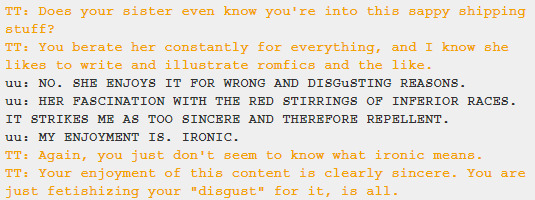

Caliborn is infamous for his disgust and anger with the absurdity of paradox space (i.e. his anger with the text of Homestuck itself), but Calliope is easily provoked into displaying the exact same petulant frustration with the direction of the story and the unfolding of events around her.

Calliope and Caliborn are consistently unified within the text -- not as incompatible opposites, but as two sides of the same coin. In Complacency of the Learned, Calliope and Caliborn are personified in the singular, androgynous Calmasis. In his chess match with Calliope, Caliborn disguises his king as his queen, and vice versa, signifying a mutual transgression and inversion of gender; Caliborn steals Calliope’s hemotyping and typing quirk, just as alternate!Calliope does the same to him, in a mutual appropriation not just of quirk (i.e. voice and presentation), but of blood, or life. On the level of the body, Caliborn’s skin is inextricably marked by the green that signifies Calliope, and Calliope is inextricably marked by Caliborn’s skull: the deaths-head he would inflict upon all life (and a hyperrealization of the masculine or unfeminine bone structure that troubles many trans women).

Most significantly, Aranea indicates to us that Calliope and Caliborn actually began as one being, which then went on to fracture into a male and female aspect, striving with and against each other -- a creation myth for gender and sexuality itself, in the vein of Plato’s Symposium, Rabbinic lore on Adam and Eve, and (rather topically) Hedwig and the Angry Inch.

With their fundamental unity in mind, we can read Calliope and Caliborn not just as ‘brother and sister’, but rather as two identities, personas, or aspects of one person. This is why, for example, calling a cherub by one of their two names brings that personality to the surface -- because, on a literal or symbolic level, it constitutes the active validation of that personality and identity, and the abject denial of the other.

Does all of this suggest a bigender, genderfluid, or otherwise non-binary reading of Calliope and Caliborn? Maybe, but let’s keep going, first.

Aranea’s exposition tells us that even adult, mature, ‘binary’ cherubs are still figures of gender duality, inversion, and transgression. Mating cherubs take on the forms of dueling cosmic serpents -- the sex act occurs between two hyperreal phallic symbols, suggesting male homosexuality in specific and queerness more broadly. It was Calliope’s biological father who ultimately submitted to their biological mother, and thus it was Calliope’s biological father who laid their egg, while their biological mother was the one to fertilize it, revealing the separation of sexual anatomy and power relations from gender among cherubs.

The gender dualities, inversions, and transgressions at play can still exist within cherubs who are, by all accounts, decisively male or female in gender identity -- despite the lack of of any way to assign them a sex or gender from the outside.

The dueling personalities within each young cherub are siblings to each other, but they are also different possible selves that the cosmically-transgender cherub might become as they grow to adulthood -- just as the dueling alternate selves of so many other characters can illuminate their own internal conflicts. In Homestuck, the inner life is always prone to manifest in the outer life, again and again.

I TRAGICALLY LOST A SISTER TO MURDER

Having established a reading of Calliope and Caliborn as two identities within one person -- as ‘Calmasis’ at odds with themself, containing multitudes and torn between them -- we can move on to look at the way Calliope and Caliborn relate to each other, and to gender, in order to get the bigger picture.

Caliborn introduces himself to us as undyingUmbrage, a username of largely straightforward meaning. His umbrage -- his anger, irritation, annoyance, or offense in the face of the world -- is neverending, everlasting, and eternal, and so too is his own life. Caliborn is immortal, allowing him to carry his rage forward forever.