#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This actually does a great job explaining one of the weirdest things I've run into being diagnosed as an adult. Was I able to fake my way through school performing well enough that the most anyone thought of me was I wss perhaps antisocial? Yes. Did I actively seek a diagnosis in adulthood because I realized over time no one neurotypical had to work this damn hard to function? Also yes. And yet, when filling out applications, I struggle to self report myself as disabled despite having MULTIPLE issues included in the federal self identification list.

For those not in America, here is the list below:

Definition of a disability You are considered to have a disability if you have a physical or mental impairment or medical condition that substantially limits a major life activity, or if you have a history or record of such an impairment or medical condition. Disabilities include, but are not limited to: Alcohol or other substance use disorder (not currently using drugs illegally) Autoimmune disorder, for example, lupus, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, or HIV/AIDS Blind or low vision Cancer (past or present) Cardiovascular or heart disease Celiac disease Cerebral palsy Deaf or serious difficulty hearing Diabetes Disfigurement, for example, disfigurement caused by burns, wounds, accidents, or congenital disorders Epilepsy or other seizure disorder Gastrointestinal disorders, for example, Crohn’s Disease, or irritable bowel syndrome Intellectual or developmental disability Mental conditions, for example, depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, PTSD Missing limbs or partially missing limbs Mobility impairment, benefiting from the use of a wheelchair, scooter, walker, leg brace(s) and/or other supports Nervous system condition for example, migraine headaches, Parkinson’s disease, or multiple sclerosis (MS) Neurodivergence, for example, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, dyslexia, dyspraxia, or other learning disabilities Partial or complete paralysis (any cause) Pulmonary or respiratory conditions, for example, tuberculosis, asthma, emphysema Short stature (dwarfism) Traumatic brain injury

I have SEVEN of the conditions listed! And every single one of them has impaired my ability to work or required me to leave work early/have a sick day AT LEAST once. Yet I still struggle to voluntarily self identify as disabled.

I worry this stems more from the derogatory way society treats disabilities and people who have disabilities. When really, so much of the definition of a disability harkens back to "unable to perform a completely arbitrary standard of society on a regular basis". Some of us (which is most of the adult diagnosed/ self identitying crew OP is talking about) can fake it with a good deal of effort, but that's not the case for everyone or every disability. Someone who is paralyzed from the waist down and wheelchair dependent can't fake it till you make it to walk up stairs.

I can spend all day backpacking in the mountains and never have an issue with my ADHD because that's a situation where my ADHD is an asset. But require me to sit still and quiet for hours on end concentrating on something and I'm fucked.

I wonder how much better the world would be if the focus of disabilities was less on "how can you not meet the arbitrary society standard" and more on where people excel? Yes, anyone with any disability should absolutely receive the help and care they need to function and live a complete, happy life! But so much of the discourse is on how disabilities make people "less than". It's dehumanizing.

man it's weird when people talk about disabilities like they're Identity Categories

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

soft-riddler replied to your post “Champagne is bad and I think we, as a society, should stop pretending...”

I’m sorry you don’t have taste

What POSSIBLE crimes have grapes committed against your family that you feel that drinking champagne is a good use of your time

#soft-riddler#replies#WAS YOUR HOME BURNED DOWN BY A ROGUE GRAPE VINE MONSTER#alcohol#i am handling landlord related stress by starting pointless discourse on the internet#everyone send me your most controversial alcohol opinions#mine is that champagne????? VERY bad and DEEPLY pointless#just get wine drunk and chuck some diet mentos into some coke!!!!!!!#(i actually have never given two shits what someone else drinks ever in my life)#(but also love thyself and drink something other than champagne what the fuck)#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#story time with star

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disco Elysium (2019) - A Review and Analysis

A postmodern role-playing game for a much different audience. A combination of skillful artistry and unfulfilled potential. An attempt at tackling difficult topics and pandering to different tastes. A full package, with deceptive contents...

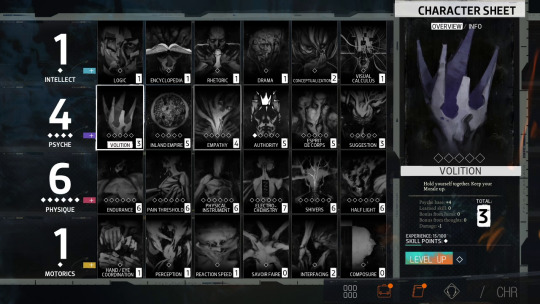

I enjoyed playing through Disco Elysium, but for completely different reasons than those that initially sold the game to me. Going in, I believed that it would be the type of RPG that I had been looking for quite some time – one that is not burdened by most of its interaction with the world happening on a grid, scanning through a list of spells and abilities, franticly pausing every frame, trying to min-max numbers as to not get destroyed by a pack of menacing farm animals of a slightly higher level. Examples of that in the genre would be classics such as Baldur’s Gate or newer re-iterations like Divinity: Original Sin and Shadowrun: Hong Kong. What I would habitually find myself doing is picking up the game, sinking my teeth into it, eventually hitting a numerical roadblock in some quest, and almost immediately retiring to a life of “not playing that game ever again”, as I am faced with the option of either save scumming and beating my head against the numeric wall, until by some fluke of the numbers I get the “good” number and am allowed to proceed; or could just stop doing whatever thing I am currently invested in and go somewhere else on the map, where the numbers are not as disagreeable, so I can get my personal numbers high enough to where the numbers I was having difficulty with before seem less impressive and I can pick up that quest again, but this time only halfway through, struggling to remember contextual cues that were relevant perhaps a few hours ago, but are now a forgotten footnote in some journal entry.

In both cases, the immersion gives way to the idea of gameplay, as the perhaps flawed ideal of an RPG is that which is based on table-top role playing games, such as Dungeons & Dragons, the aforementioned Shadowrun, or anything else that follows the same formula. From my personal experience in TTRPGs, the same issue persists, namely in having meaningful choice and character development take second fiddle to massive 3-5-man 1-2-hour combat encounters in between the more immersive moments of dialogue between players, non-player characters or story development. I’ve always felt that combat is so abstracted from everything else in TTRPGs in the way that it suddenly shifts into an entirely different game, which unlike the elements of role-play is less free-form and bound to a rigid set of rules. You’re no longer interested in how things look, feel or act, but rather how large a number is on a sheet of paper; and this contention of mine seems to always be translated into the video game counterpart of this genre, carrying the same problem from one medium to the other. Games even seem to compound upon the issue, by putting you in charge of multiple characters, where your custom created character is somehow not only equal to them, but at the same time the savior of the universe and all that is holy.

I cannot help but believe that the party ought to be AI controlled pawns, considering that they are supposedly different people with their own goals and aspirations; thus leaving the player to micro-manage their singular character – their avatar in the game world, rather than developing a form of psychogenic schizophrenia by having to deal with each and every one of the party’s members (now, admittedly the remakes of both Baldur’s Gate games have such a feature, but the combat AI is so poor, that you still have to go and remind them that they actually have a whole list of spells that they could be, in fact, using to… for instance, heal you, as you sit there bleeding profusely, crippled and powerless on the ground).

The only games which I have seen managing combat and RPG elements successfully are listed as a fundamentally different genre, known as “immersive sim” or “0451 games”. To name a few, that would be games like those of the Deus Ex, Dishonored and even the Fallout series. Most of those are first-person, for the most part shooters, with some emphasis on a singular character’s development through dialogue and stat point distribution. My main point can roughly be exemplified by comparing the naming convention and the reality for both genres: one is a “role-playing game”, the other is an “immersive simulation”; the first being used deceptively, as you could be playing a multitude of roles at any given time and also suspending that role-play to participate in some rather lengthy tactical combat for what could be 50% of the game’s runtime. On the other hand, you have “immersive sim”, which according to Warren Spector (game designer of Deus Ex and Thief fame) is a game in which “you are there, [and] nothing stands between you and [the] belief that you're in an alternate world”. I simply cannot emphasize enough how even the most engaging narrative and the most skillful writing can be tarnished by this type of abstract combat, which feels so fundamentally foreign and somehow still intrinsic to the idea of role-playing games and immersion.

Disco Elysium seemed to be the odd one out – a RPG that has no combat, except that, initiated by your choices in dialogue (more akin to playing an animation than actual combat). It was also advertised to me as having quite an in-depth ideological system, that was affected by your choices in-game and would automatically adapt dialogue according to your flavor of politics, philosophy or culture through a series of thoughts, which you would internalize, if used often enough. Frankly, it seemed like wish fulfilment for a jaded immersion-loving straight-edge centrist such as myself.

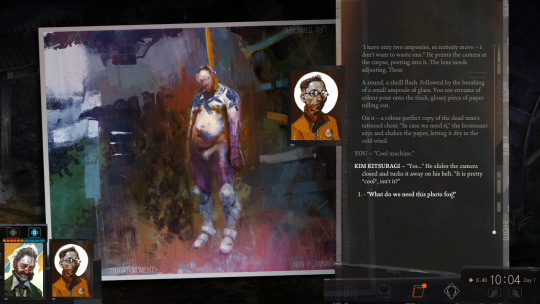

Upon launching the game, I was quickly introduced to the persona that I would be inhabiting – a deranged, drunken amnesiac, who in some cases would pass as a cop, but only if one’s notion of law-abiding is that of a drug-fueled abusive lover; also known as - the farthest thing from me. I already knew that my journey through the game would be that of a redemption arc, where this horrible piece of shit human, was going to become the most squeaky-clean, drug- and alcohol-free centrist known to all of Revachol. A true test of the game’s systems in action – from deranged and corrupt, to the straight and narrow. To my eventual surprise - I could do all of it, and very successfully at that. By the end of my nearly 24-hour playthrough, I had achieved my ideal vision for the character, with only a bit of resistance, which I will briefly mention further down the line. For now, I had succeeded in using all the tools available to me in order to internalize the thoughts for centrism, rejecting any form of drugs, and by the end almost managing to squeeze in the time to internalize being sober, cut short due to the spontaneous conclusion of the game.

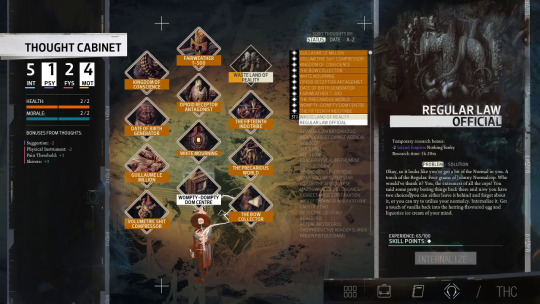

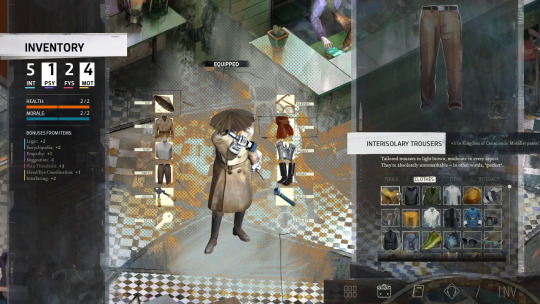

The thoughts system was not entirely what I had initially imagined. Namely, what I had envisioned was a system, which converts whatever responses one made throughout the game, into non-internalized thoughts, which would begin to alter the dialogue options available, and only after choosing to emphasize said options, would it eventually internalize and give you a lot more radical options based on said thought. What it would turn out to do instead is make the acquisition of thoughts work in a similar manner, but make the process of internalization a menu, in which you “equip” thoughts into available slots. It seems like a minor inconvenience, but it makes the thoughts feel like yet another item that you just set and forget, rather than the thoughts of a person being actively developed over time, based on what kind of discourse they engage in. I suppose the idea of having it take anywhere from thirty minutes to six hours to internalize is there to be the substitute for the drawn out process of internalization. It is in a way saying “I feel like turning into a centrist in the next thirty minutes.”, while going around doing investigative work around a crime scene. The more active process I envisioned, would indeed take a lot longer, but it would be massively more immersive, as more and more options become available to you over time, rather than after some arbitrary timer has gone down.

Another big detractor is having to use skill points to unlock new slots for thoughts, which would otherwise be put into your more practical skills. Theoretically, one would think a human has an almost infinite capacity for new ideas; and one is surely not going to want to internalize them all. A good example would be the “Volumetric Shit Compressor” thought you gain early into the game, which mainly fulfils its purpose in one skill check for less physically able characters as a part of a single quest and is never made use of again, beyond its flat stat bonuses. No other thought in my playthrough had a temporary pragmatic function like that, which feels like a missed opportunity. Its temporary nature is where the skill-point cost seems absurd, when they could be better used to improve one’s skills. In what way would the character becoming more skillful help them stop “getting their shit together”? Wouldn’t one discard the though immediately after it’s no longer useful? The way the system works currently, meant that I spent most of my points on slots and playing around with thoughts, rather than improving my character until the very last parts of the game, which in effect made the game more difficult than intended. The decision to make thoughts equipable and not persistent passive perks that can upgrade into more radical or complete versions of themselves is perhaps one of my main disappointments with the game. The effect on scope would be minimal, as the game already has the dialogue options for those thoughts written and would only need to change their acquisition and internalization to be less menu-driven and more player-driven.

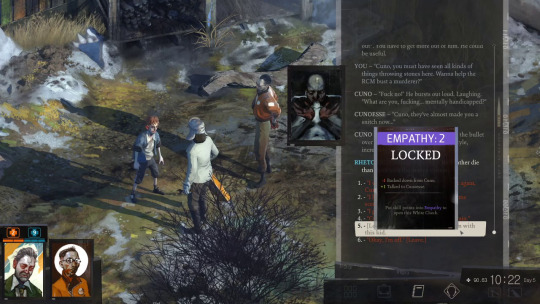

I tangentially mentioned not having skill-points to freely use until the latter parts of the game: That in turn made skill checks a lot more difficult and perilous, by making white skill checks (ones you can fail and retry upon increasing the skill they require) harder to re-unlock once failed and making red checks (ones that you cannot retry once failed) almost impossible, if not clothed in every stat-boosting piece of apparel in one’s inventory or seasoned with every potentially hazardous bottle of booze or glowing fairy dust left lying on the ground. White checks also do not unlock after one has used a consumable item or changed a piece of clothing to boost said stat, which encourages save scumming, as there is no way to change clothing in the middle of dialogue or knowing what the skill check will be, leading to one of the many pitfalls which I described earlier.

An even greater fault is that some quests just drop dead in their tracks, if the stat check is not completed. Moreover, since one cannot be proficient in all four skill categories, I would regularly hit a brick wall, upon being faced with a Psyche or Physique skill check, as my character mainly specialized in Intellect and Motorics. The thing about hitting a brick wall in Disco Elysium is not so much that you fail and have to face the consequences, but rather cannot continue at all and the narrative stops dead in its tracks until you can succeed the check. Sometimes quests are tied to each other, so not being able to progress in one of them means that you can’t progress in any of them. Suddenly an entire quest chain can just be gone at the click of a button. It got to a point where I would prefer to hear that all my efforts were in vain, fucking everything up irreversibly, rather than having a white check get locked and sit there in my journal, waiting for me to miraculously gain five points in some sub-skill of Physique. One way to fix this would be to have more obfuscated red checks with uncertain odds that lead to failure states. At least that would be more immersive than the current offering, as one could live with the consequences, rather than be left guessing what it could have been if one had slightly higher skills. This, however, could be difficult, as there is a dice roll to every skill. Not being skilled merely means you have less of a chance of succeeding or, alternatively, a higher chance to fail and lock the skill check.

The one thing that the game does great when it comes to skills is the addition of secret tasks. If one were to follow particular lines of inquiry, they often lead to some skill check down the line becoming easier, due to the things learned beforehand about that topic. This system rewards being thorough and attentive and is, perhaps, the best feature of the game. However, observations made through the “shivers” system (where orbs of information will show up contextually above the protagonist’s head, revealing information about the environment or elaborating on something relevant) do not appear to factor into these skill checks. This often leads to you reading something important when it pops up in the overworld, but upon engaging someone in conversation one must often select benign lines of dialogue, acting like one hadn’t made those observations to begin with. The dissonance is even more infuriating whenever Kim (your companion throughout the game) tells you that you are obviously wrong, because he also made those observations but (unlike you) could talk about them. It would have been a lot more diegetic if there were dialogue options available for you to repeat the observation to Kim instead, perhaps as you talk to him in the overworld (a feature that is woefully underutilized, and shows the same five or so options throughout the entire game, except whenever Kim wants to talk to you about something he deems relevant – an ability, which you would think the player should have had as well).

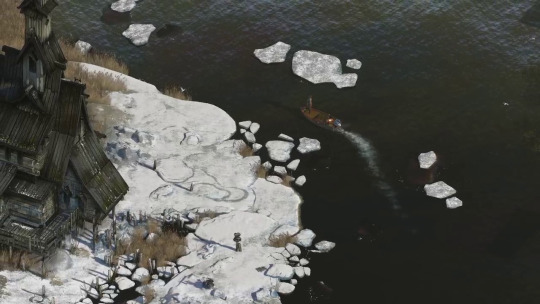

Speaking of the overworld, Disco Elysium does quite a lot with the small real-estate it has on its map. For what feels like a small neighborhood, it packs tens of hours of content, a varied cast of characters and lots of places to explore. Walking around is encouraged by the game, almost to a fault. At many points during the game Kim will remark upon your seemingly absurd ability to run around without getting tired. There even comes a point where you are injured, and are told not to run to avoid further harming yourself. After about twenty hours I realized that this was in order to signal to the player that if they run all over the place, trying to finish everything as quick as possible, they would be left with a lot of extra time at the end of the day, which would have been perhaps better spent looking into side-quests or other optional activities. However, the walk speed is woefully slow and with the amount of backtracking one needs to do, means that you will be seeing the same places plenty of times, which only tempts you even more to not waste your precious time RP-walking. The game has benches, which you can use to pass the time, but they are only available whenever Kim is not with you, which is only durring the night, meaning you can’t make any meaningful progress by resting on one, effectively making them worthless. That and the presence of time-gated tasks, means you will most likely be trying to find ways to waste your time, prompting Kim to berate you even more for straying away from the main focus of the narrative, as he often does. If you’re a fast reader, the game luckily fast-forwards time based on how many options you’ve selected, rather than real-time. This is most apparent whenever you’re save scumming and going though entire trees of dialogue you’ve already read.

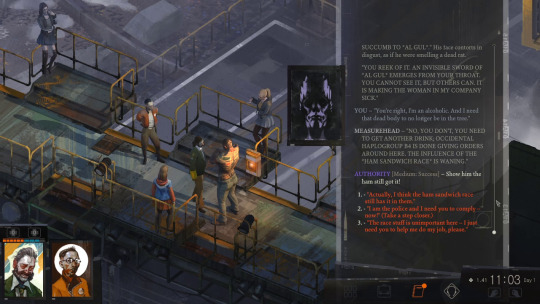

And you will be reading a lot, as this is what you signed up for when you relinquished the combat systems of your typical RPGs. A welcome change, I might add, as the dialogue is beautifully written and engaging for tens of hours. (The end credits even thank Chris Avellone for what is probably him lending a bit of his Midas touch when it comes to game writing.) However, there are of course flaws in the way Disco Elysium decides to portray some of its characters, as it is sometimes more interested in making political statements in a very one-note way that might shock some people, rather than what one would think are nuanced and fleshed out personas. A large part of the cast is wearing a thick layer of existentialism, which they seem to flaunt upon every given opportunity. The same goes for characters who clearly exhibit some variety of political radicalism; you’ve got your racist nationalist, your bourgeois-eating communist, your fence-sitting centrist (dubbed moralist) and a whole swath of colorful opinionated people whom you either interact with or endure. Everyone else is mostly pleasant to be around, if not a bit saddening, due to the overall melancholic way of life people of Disco Elysium are forced to lead, influenced by factors that they alone cannot control; an overall sense of futility present at every turn. Most of them have quirks that help them cope with their predicament, which you can explore in full detail through in-depth dialogue trees, leading to some intriguing interactions and ultimately some interesting consequences down the line. Every line of dialogue seems to have a lot of those, which is surprising for a game that so haphazardly makes you select dumb questions for answers you already know. An example of that is the one occasion in which I used a particular brand of alcohol to boost my “Pain Threshold” in order to open a certain mission-critical freezer. Which towards the end had Kim labeling me as someone who “drinks on the job”, even after becoming sober and internalizing the thought that removes all positive effects from alcohol, as well as the action leading to us retrieving an item, which we would later use to further the plot. Instead as a one-off sacrifice of one’s principles, it was seen as a major transgression that would only lead people into thinking of me as even more of a raging alcoholic, rather than someone who is trying to recover and “get their shit together”, as it were.

A major part of the game’s rhetoric is lost to those who do not have a dictionary that has been well tempered through copious forms of political jargon, coming from a various selection of manifestos, academic political analyses and some of the more famous philosophical works for the last century. I would go as far to say that some of the sentiments the game presents are absolutely impenetrable when it comes to wording. I’ll give you an example:

Heartache is powerful, but democracy is *subtle*. Incrementally, you begin to notice a change in the weather. When it snows, the flakes are softer when they stick to your worry-worn forehead. When it rains, the rain is warmer. Democracy is coming to the Administrative Region. The ideals of Dolorian humanism are reinstating themselves. How can they not? These are the ideals of the Coalition and the Moralist International. Those guys are signal blue. And they're not only good -- they're also powerful. What will it be like, once their nuanced plans have been realized?

If you immediately recognized that it was about centrism, then congratulations – you are a lot smarter than me and probably everyone else around you. For you Disco Elysium is the perfect college-level textual experience for your Tuesday-night 1960’s poetry club. For the rest of humanity, it’s a bunch of gibberish. Flowery prose and poetics are riddled everywhere and you're never really sure what you're doing, what thoughts you're thinking or what's happening to you.

I mentioned briefly that the game tries to depict centrism as a form of moralism (a term which it prefers over the former). Even so, it presents centrism as less of an effort to hold multiple perspectives and act with a full and informed range of understanding, but rather as the stereotypical “fence-sitting” argument, where no decision can be made now, and progress can only be obtained through a slow, incremental process. While on the surface, it would seem so – as a self-proclaimed and passionate centrist, I cannot help but disagree with the outsider view that the game seems to be promoting, favoring critique of the right and an emphasis towards the left side of the political compass (making small but insignificant jabs towards both throughout). Contextually, the game’s developers Studio ZA/UM, have displayed a clear favor of the political left in their public appearances, which may explain this somewhat skewed perspective. While it’d be lovely to go on about the politics of ideology, it’s better not judge the contents of the game based on the developers’ ideological affiliation, but rather on its own merits.

Considering the amount of reading one needs to do, I would hesitantly say that Disco Elysium is part RPG, part choose-your-own-adventure visual novel. I say RPG, because of the aforementioned brick walls, inhibiting progress in a way that no immersive sim ever would, as there would be multiple ways to get the same information, which is sadly not a thing Disco Elysium does well. The sheer volume of the text is also a cause for some, I would suppose, aesthetic concerns about the game. Graphically, the game is stunning with its unique painterly style, but it often values it over function, namely in having the UI serve little to no purpose, as Kim and your portraits take up the entire bottom left of the screen. At the same time the dialogue panel is put on the far right side of the screen, even though two thirds of it are spent zoomed in on some 3D models doing their idle animations, instead of having the text front and center, as the thing you will be most likely looking at for 90% of your time with the game. Other technical issues include shadows being displaced from where they should be, especially on stairs, as well as being incredibly jagged for a game that doesn’t really have high hardware requirements and very little real-time lighting, but all of this is frankly unintrusive, compared to the cramps in your neck from looking to your right all the time.

Every once in a while, you get to enjoy not having to read, as a select few scenes are entirely voice-acted by a talented cast. I am unsure, however, of the production team behind the recordings, as they seem to sound as if recorded in home studios with different microphones and sound processors. Other than that, the quality and range of the performances is wonderful, especially since it is coming from some lesser known actors in the industry.

When it comes to sound, the game does a fantastic job of establishing a lot of varied soundscapes for an admittedly small plot of land. The music is ambient, droning and subtle in all the ways that make you not think about it, until you are sitting there listening to the soundtrack on your own time, remembering all the scenes that every piece of music has lifted from monotony. All of the tracks have this aging, somber tone to them, much like the world they are written for, making the music an unavoidable essential part of the experience, as you walk the fields of Revachol with the wind blowing and the small creek near you emitting a slight babble. The only downside is that the mixing of all these layers is often horribly unproportioned. Everything will be quiet, until some random intercom plays two straight minutes of loud white noise into your ear. Those parts are few and far between, but still leave a surprisingly large impression for an otherwise spotless execution of foley and ambience.

Overall, Disco Elysium is a full package. While not necessarily the game that I hoped it would be, it was still an enjoyable experience with an incredible main quest, memorable characters and side quests, elevated by wonderful sound design and fantastic ambient music, with writing that will be unparalleled for years to come. While it is not without its flaws, and some of them are quite major - it does what it set out to do with flying colors and is sure to appeal to a lot of people, who have been looking for an experience such as this. For me, however, it also represents a lot of squandered potential. It is by no means an ideal game – far from it; but I would still recommend you play through it for yourself, just to see where it takes you. It has a way of challenging you intellectually, that not a lot of games can pull off, especially nowadays. It is an admirable endeavor in tackling difficult topics, whilst also spinning an intriguing narrative that keeps you invested until the very end.

Score: 7/10

#game review#review#disco#elysium#disco elysium#harry du bois#kim kitsuragi#game analysis#game design#narrative#analysis#essay#revachol#oranje#politics#thoughts#systems#mechanics#game mechanics#RPG#visual novel#immersive sim#TTRPG#singleplayer#adventure#spoiler free#no spoilers

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

IN HER LATEST BOOK, The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath, Leslie Jamison writes “‘addiction’ has always been two things at once: a set of disrupted neurotransmitters and a series of stories we’ve told about disruption.” In many ways, The Recovering acts as its own sort of disruption of how those stories are told. Not only does Jamison bring together a variety of disparate perspectives on addiction and recovery — articulations that are often kept apart from each other — but she does so in a way that transgresses both the boundaries of genre and competing sensibilities about what makes a story worthwhile.

Anchored in the personal narrative of Jamison’s own experience with alcoholism and recovery, The Recovering places Jamison’s story in conversation with those of literary figures whose work — drenched in the mythos of “whiskey and ink” — inspired her, as well as those of ordinary strangers she encounters both in her reportage and in the rooms of Alcoholics Anonymous, and the larger social history of how addiction was pathologized, criminalized, and racialized throughout the 20th century. As a patchwork of memoir, reportage, literary criticism, and cultural analysis, The Recovering also draws attention to how Jamison’s training as a creative writer, literary scholar, and AA member informs her story in ways that productively challenge how stories are differently constructed, interpreted, and valued in those contexts.

I spoke to Jamison about the various conceptual, stylistic, and discursive bridges she attempts to construct throughout the book, as well as what it was like to translate her story from the rooms of AA into a dissertation on narratives of addiction and, ultimately, into a work of popular nonfiction.

¤

DENISE GROLLMUS: The Recovering draws its energy from the tension that exists between the competing narratives we tell about addiction. There’s your personal story, the stories told by and about literary figures, the cultural history of race and addiction, the stories you encounter in the rooms of Alcoholics Anonymous, stories you collected from other rehabilitation institutions, the psychoanalytic discourse, the medical discourse. Your book gestures to how the discourse of addiction is as profuse and conflicted as the need it attempts to describe. How did you manage your way through that profusion and not get overwhelmed by it?

LESLIE JAMISON: The most honest answer is that pretty early on I had to completely surrender the fantasy or the delusion of comprehensiveness on many levels. Like on a very basic level, when I told anyone about my dissertation or about this book, they would immediately ask, “Are you writing about this book? Are you writing about this novel? Or this author? Are you writing about the opioid crisis?” When you bring up the subject of addiction, the subject moves in 10 thousand different directions, and almost always, my answer was going to be, “No, I’m not writing about that” or, “Oh! I left that out.” And the immediate impulse for me was to feel a sense of shame, in the same way as when someone asks, “Have you read this book?” and I haven’t, because some part of me feels like I should have read everything and have something to say about everything. At a certain point I just had to say: This is a book about addiction, it’s not the book about addiction, so there’s going to be a lot that it doesn’t cover.

That said, through revising different drafts, I definitely did bring in discourses that had been absent from earlier drafts. Like, in the earlier drafts, I didn’t discuss at all medical definitions of addiction, or what addiction looks like in the brain, or what a doctor might say about addiction. But early readers also really encourage me to think about how literary accounts of addiction looked next to how medical science tries to illuminate addiction, or to consider what a doctor would say about how a 12-step program tries to respond to addiction. The goal was to try and bring in those modes of understanding addiction, even in fleeting ways, just to see how they could be in conversation with each other.

How did you end up choosing the discourses and stories you did include alongside your own?

Some of it had to do with the question of who the important people and the important voices were to me as a reader and as a person trying to get sober, especially in terms of the authors and artists I included. So, to some extent, it is unapologetically subjective and arbitrary in the sense that these are voices that happened to matter to me. But that basic architecture of the book also evolved. At another stage, I started to feel incredibly claustrophobic about the book simply being my story engaging with the stories of creative people whose work had been important to me, which is what motivated the choice to bring in the larger social history and the racialized nature of how addiction has been understood and prosecuted. I also wanted the book to work structurally in a way that was somehow akin to a meeting, but I didn’t want the stories that were populating that meeting to simply be the stories of famous writers. So, I wanted to include the stories of ordinary strangers, but I also didn’t want to include the stories of people I had met through recovery in a very detailed biographical way. I knew that I needed fully developed stories of strangers and I needed them to be people I met and approached as a writer, where the contract was clear that I was talking to them about their lives, because I wanted to put their lives in a book and make sure that they were comfortable with that exchange. That emerged from my desire to create a chorus of strangers in a way that wasn’t just me relating to people through their archives, but also me relating to other human beings that I was encountering. That was what motivated the turn to the Seneca House stories.

One particular tension that really struck me was how the pathos of your personal story is so sharply juxtaposed with the reportage style of the social history that you tell about the racist evolution of the drug scare narrative in 20th-century America. Though these two threads and their competing styles become more integrated toward the end of the book, the way they initially sit next to and apart from each other highlights how race, class, and gender inform whose pain is made visible, what that pain is allowed to look like, and how that pain is treated with compassion or not.

The truth is I felt a tremendous amount of anxiety about how these various stories were going to integrate. A few years into writing the book, I realized that I needed to contend with how the ways I had been allowed, encouraged, and given the means by which to articulate my own pain lived alongside racialized, punitive responses to addiction throughout 20th-century America. I very much didn’t want to just feel that cognitive dissonance and then write a book that was about myself and some other white people whose work I had read. I wanted to somehow allow that cognitive dissonance to become the content of the book itself and to trouble the surface of the book. One of my most important teachers, Charlie D’Ambrosio, always used to tell me that the problem with an essay can become its subject. One of the ways that advice bore out for me in this book was taking the way I felt troubled by my privilege and the ways in which my privilege had inflected how I’d experienced and narrated my addiction and make it a problem that didn’t simply haunt the margins of this book, but could be something the book was wrestling with explicitly.

For so long we’ve lived in a narrative landscape in which a certain type of drinking story is told over here, like in a memoir, and a certain kind of story is told over here, like in a discussion about policy or the opioid crisis. I just wanted to bring those very different stories together. I also wanted to address how that same sort of discomfort also lives in meetings, where people from incredibly different backgrounds are coming together under the belief that they can somehow gain something from listening to each other’s stories, even though those stories are often marked by vastly different levels of privilege and vastly different ways in which people have been allowed to express their pain or have their pain witnessed. So, the way in which I would feel uncomfortable in meetings about why anyone would want to hear what I have to say when people in this room have been through so much more, that same anxiety became part of the writing of the book itself.

Aside from the tensions between these different stories, you also touch on the tensions between the competing ways you were trained to be a reader and writer in different institutions, from the MFA program at Iowa and the PhD program at Yale, to the storytelling practices in the program of AA. As someone who is also in recovery and is also working on an academic project about narratives of addiction, I very much related to your description of straddling the huge rift between academia and recovery, largely because of how reading practices in the academy are so heavily dominated by the hermeneutics of suspicion, while the approach in AA is so inherently and necessarily reparative. A lot of literary scholarship reads the narratives that addicts tell about themselves as one Foucauldian nightmare after another, which is so antithetical to the way we interpret our stories in a space like AA. How did you bridge that divide while working on the iteration of The Recovering that was your dissertation? And how did that inform the current iteration?

That all really resonates, especially since I was basically trained as a close reader and didn’t particularly come from any theoretical background, so by the time I arrived at my PhD program, I was sort of like an idiot savant. I didn’t know anything about theory, and I hadn’t really spent time thinking about textual history as a way of coming at literature. It was sort of an embarrassment to me how much I didn’t know, but also a revelation to start spending time in archives and to realize how much I loved both investigating textual production in a very concrete and visceral way. I also became fascinated by the conversation between texts and institutions, and between texts and the larger contexts they came from. That fascination played out in the dissertation, where each chapter was a conversation between a literary text and then some sort of institution or set of institutional texts.

My advisors also ended up being a wonderful set of counterweights for me, because each one of them had a certain kind of suspicion that they brought to the table. For [Caleb Smith], one of my advisors, Foucault shapes a lot of how he thinks about the world and about texts. He does a lot of research and writing about prisons, and the way that prison has shaped the American imagination, so he’s pretty suspicious of institutions, and he was like this godsend for me. Where I’m predisposed to affirm or find something constitutive or saving, his whole approach to something like AA is filled with suspicion about what sort of behavior or narrative is being coerced by this social pressure. Far from feeling like these more suspicious modes of thinking or reading were obstacles, I felt like I was getting tremendous amounts of useful pressure to clarify and interrogate what I was thinking, so there was something so great about the process of incubating a lot of ideas and certainly conducting a lot of archival research under the auspices of my dissertation.

But at a certain point, I also knew that I wasn’t invested in the text of the dissertation. I knew I didn’t want to become a scholar or publish a monograph. I knew I wanted to write this crazy, hyper book, and I wanted one of its strands to be literary criticism and archival research. My dissertation was really a means to an end, rather than an end in itself. I wanted to use all of that research, but I wanted to rearticulate it in what felt to me was a more natural writing voice, rather than an academic writing voice. I wanted to use that work to sustain and feed this bigger, more nebulous project that I felt more committed to.

There was no part of your personal narrative in your dissertation, then?

Not at all. My dissertation was definitely pretty far on a continuum in terms of what the Yale English Department was willing to tolerate. To write something that was verging into personal narrative would have been beyond its upper limits, I think. And by the time I submitted my dissertation, I knew that it would feed this other book, so I didn’t feel any need or desire to put my personal narrative into the dissertation, because I was already sculpting this other book, where I knew it would have a place.

In the book, you express an anxiety about writing “another” addiction memoir, or even worse, you say, a work that would be described as “not just another addiction memoir.” And even though you do describe it as a chorus or “an anthology held together by earnestness,” the personal narrative really anchors the book. What were the stakes of including your personal narrative? Why not write a cultural history of addiction based in the stories of others? What was generative or crucial about including yourself despite your apprehension?

It’s an important question. For me, some of it has do with how my own creative desires are connected to narrative and specificity and the sort of creative writing I’ve always wanted to do. For years, I just wanted to be a fiction writer and I only wrote fiction, and I was so drawn to the idea of bringing a reader along on a story and making that story as lushly habitable as possible, to have it full of the granularity and viscerality of lived experience. And that’s always how I wrote. My writing was always full of sensory details and small moments of observation. That kind of granularity was always the kind of writing that was exciting for me to do. In nonfiction, there are lots of ways to access that sort of granularity, and certainly reporting, if you are taking notes and doing your job right, you can collect that specificity. But I felt that my own story was the story I had the best access to on a really crude level. That’s not to say that we have perfect access to our own lives, because I think self-delusion and imperfect self-knowledge are real, and we’re always questing to understand our own lives, rather than existing in some a priori state of understanding our own lives. But I was excited by the idea of anchoring the book with a spine of personal narrative, because I did want the book to have the momentum of a good yarn, of a narrative that was unfolding where you wanted to know what happened next, where you had all that specificity and the mess and grit of life, and my life was the life that felt the most readily available to use to anchor it and be that spine.

The choice to place that story so centrally among the other research also seems to speak to how the addict was also once the expert of her own experience. Like in the 1820s, before the consolidation of the medical field, Thomas De Quincey was being invited to speak at medical conferences, and his personal account of opium addiction wasn’t just an object to be studied, but it was accepted as a rigorous study of addiction in and of itself. And then, less than 20 years later, doctors start dismissing his accounts as little more than the unscientific, literary musings of a junkie. The addict becomes someone to study, not someone who can do the studying.

I hadn’t known that about De Quincey, but it really resonates with something that became really interesting to me, which was tracking [the founder of AA] Bill Wilson’s story as he told it in different contexts and what he chose to accentuate depending on what audience he was speaking to — like what he put in his autobiography or his story in the Big Book versus what he chose to include when he published his story in the New England Journal of Medicine. He definitely toned down “the great clean wind of a mountain top” rhetoric to present himself in a way that spoke to authority. And the fact that the New England Journal of Medicine was publishing his story said something about what they considered an authority or a voice worth representing. But he also felt like he had to skew his story in a particular way to make it credible in that context. And I also think there’s a pretty inherent traction and siren call to hearing the story of a particular individual. That’s not to say there aren’t all kinds of things that are compelling about stories on larger scales or social stories or the larger story of how Americans have understood addiction in completely schizophrenic ways throughout the 20th century. But there’s something about returning to the scale of the individual life that speaks to something pretty basic about human curiosity and what people are compelled by, enchanted by, and captivated by. It also speaks to how the logic of an AA meeting works. A meeting is a room full of experts on their own lives who are simultaneously being taught that they aren’t fully experts on their lives.

But in the rooms of AA, expertise is often collaboratively constructed. Nobody has all the answers. Instead, you come to a discussion meeting, for example, and you say, “I’m having this problem,” and then 20 other people offer their own iteration and approach and by the end of the meeting, the group conscience, or the chorus, as you call it, becomes the expert, really.

Yup, yup, yup. and I think that’s part of the reparative work I was trying to do with clichés in the book. I was trying to suggest that, for the super self-conscious, hyper self-aware person, part of what the cliché can do is disrupt that sense of expertise. Or to suggest that perhaps this simpler explanation that feels far too interchangeable to apply to you actually has something to teach you about your own life that you might not already understand.

I’m intrigued by what happens when the stories we tell in the rooms of AA become literary memoirs and AA clichés are embedded in literary language, which is supposed to be evacuated of cliché. Part of me revels in the transgression, while the other part of me — the part also trained in an MFA program — wants to scream: “lazy writing!” That move, which you see in works like Mary Karr’s Lit, for example, challenges aesthetic value in generative ways. What are some of your favorite AA clichés?

One of the things I think is lovely about how expansive the AA network is that I’m never quite sure what is an AA cliché or just a cliché. I always love the one, “sometimes the solution has nothing to do with the problem,” because it is such a useful antidote to my natural impulse to solve a problem by thinking about it hard enough or thinking about it intelligently enough. This idea that maybe the answer to the problem was getting coffee with a stranger, instead of analyzing my own life ad nauseam, was so useful. I also like “feelings aren’t facts,” although I also speak about them endlessly. And “one day at a time” is basic, but the number of times I’ve had to invoke it to help me through the moment is infinite. Then, there’s this one, I don’t know exactly how it was formulated, but this one man always used to say it at meetings: “Things don’t always get better, but they always get different.”

¤

Denise Grollmus is a writer, teacher, and literary scholar based in Seattle. She is currently working on a PhD at the University of Washington, exploring how narratives of addiction use religious discourses and concepts in order to complicate medical and popular models of addiction.

The post “An Anthology Held Together by Earnestness”: A Conversation with Leslie Jamison appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2rbNxwT

0 notes

Note

ice wine anon here, please do try it! it is definitely expensive compared to ordinary wine. but it tastes sweet, and for the good red ice wines, a little bit syrupy - like alcoholic juice to put it simply lol. i'd recommend the peller estate cabernet franc if you can get your hands on it!

Oooooh, I’m going to add this to my List Of Luxuries that I am going to indulge in post-lockdown.

Other things on the list include “go to the standing-room-only Indian joint in the West Village with my partners for naan tacos” and “sit in a library around other people for several hours,” so ‘luxuries’ may be a stretch, but I’VE BEEN INSIDE FOR S E V E N WEEKS, LET ME HAVE THIS.

#alcohol#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#oh kiddos i want to lie down about the last two days so much#i want to go to a coffee shop and sit by a window and watch a street be alive#i want to get drinks with upstairs inc and find out if they like board games#i want to hug my parents#i want to go to a restaurant and a library and a bookstore and the butcher down the street#i would like life to be okay again#and when it IS i'm finding myself some ice wine to taste#sorry that got a little maudlin but we're still Handling Stuff and i'm burning the fuck out on landlordman's lying bullshit#Anonymous#asked and answered#story time with star

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm also not a fan of red wines and avoid them mostly, but I have had decent ones before but really pricy (which, what's the point if I can have something that tastes good and is cheap?). have you tried ice wine though? i find red ice wines are better than white ones!

I think my issue with red wines is probably innate (the bf likes fancy wines, despite me and one of the gfs making a policy of keeping eight dollar wine in the fridge, so I’ve tried the gamut), but until this very second I didn’t even know that ice wine EXISTED and now I’m like halfway through the Wikipedia page about them and I would absolutely LOVE to know what the creator of the first ice wine was thinking. This strikes me OVERWHELMINGLY as something that someone did by accident and then had to spin as a stroke of genius really quick in order to cover their ass. I would love to try this stuff.

Anonymous asked:

The only acceptable kind of wine is the mulled kind because warm alcohol equals faster buzz and the spices actually make it taste like something other than rancid cough syrup

I’m elated to tell you that you can mull apple cider and throw some spiced rum or gin in that bitch and it tastes absolutely nothing like alcohol and it’ll get you drunk REAL quick. I haven’t been around mulled red wine since I was performing in a Christmas pageant when I was 14 (obviously not allowed to drink the wine), so maybe I’d like that, Idk.

...I did just find a recipe for mulled white wine featuring honey and brandy, which. It’s getting to be too warm for it, but I could be convinced to mull some wine out here.

Anonymous asked:

another different anon here. i forget how much i hate red wine until i have a glass of it, every dang time. because it smells good! and then i drink it and it burns and is bitter and gross! i prefer frozen margaritas any day of the week, those actually taste good in addition to getting me pleasantly buzzed. also YES about champagne being bitter fizzy hell

I keep trying more red wines! Because for some reason I feel like I should be the kind of person who likes red wine! And every time I take a sip I feel like my tongue is trying to meld with my hard palate to escape the Flavor! It’s so bitter, it’s absolutely unbearable, and that is coming from me, a person known to eat raw lemons.

#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#alcohol#my passionate dislike of red wine is possibly connected to my passionate dislike of coffee#the bf went through a phase of trying to find a coffee i would like#and he would be like 'here is a very fancy and expensive espresso just try it'#and i would taste it and go 'i'm so sorry bf this tastes like distilled unkindness'#now i said 'known to eat raw lemons' up there and what i meant was 'known to buy lemons with the intent to eat them'#apparently criminal intent per the partners but w/e i have rights and those rights include lemons#i will eat this sour fruit and i will regret nothing except the place where i bit my tongue yesterday#so when i say something is intolerably bitter/sour it is a STATEMENT#maybe these were all the same anon actually? idk#i answered them all separately and i will not be questioned on it#if you're the same anon then you've now been assigned two false identities by the power vested in me#i think i'm too stress-giddy to be online but i will not get anything else done so you all have to deal with me#Anonymous#asked and answered#story time with star

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

aces-to-apples replied to your post “Champagne is bad and I think we, as a society, should stop pretending...”

champagne tastes bad and it should feel bad. it certainly makes the /drinker/ feel bad. it's like it's angry at being drunk and feels the need to punish us for the audacity.

YOU are valid, you’re SO valid, I’m out here drinking gin, straight, in a glass, and I still feel like champagne exists to punish me for having the nerve to drink it at a New Year’s party or something.

#aces-to-apples#replies#alcohol#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#new year's parties are the only time i drink champagne because that is when the champagne is free#as a general rule#and even then i drink like. half a glass. and then i go pay money for something else to drink.#also!!!!!#to the anon who sent me some HIGHLY valid champagne commentary!!!!!!#the first half of your commentary has been tragically lost!!!!!!!#story time with star

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

definitelynotscott replied to your post “Champagne is bad and I think we, as a society, should stop pretending...”

The carbonation actually makes the alcohol absorb faster for some reason. Apparently people like writing grants for cases of champagne.

I JUST GOOGLED THAT AND IT’S TRUE????? THAT’S FUCKING BONKERS. THE HUMAN BODY IS SO WEIRD.

#definitelynotscott#replies#alcohol#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#who the fUCK is offering grants for cases of champagne?????#like i can kind of grasp the kind of person who would write a REQUEST for a grant to buy a case of fancy champagne#but who's OFFERING those grants#who's like 'write a good enough request and i'll buy you just. the FANCIEST rotten garbage soda.'#is this science????? are these scientists asking for a bunch of fancy rotten garbage soda for SCIENCE??????#(before you ask: beer is regular non-fancy rotten garbage soda)#story time with star

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

laughingcatwrites replied to your post “Champagne is bad and I think we, as a society, should stop pretending...”

Thoughts on prosecco?

Pretty sure I’ve only had Prosecco as part of a cocktail that was mostly Chambord with some fresh raspberries thrown in there, so when it’s under those circumstances, I would probably like anything.

#replies#laughingcatwrites#and when i say 'mostly chambord' i mean MOSTLY CHAMBORD#contrary to what my comment about drinking straight gin might suggest#i actually prefer my drinks to taste as little like alcohol as humanly possible#there's this thing called a bay green? it's like...cucumber and basil and A LOT OF GIN and it tastes like absolutely nothing#i can (and have) drunk like four without even NOTICING#well--without noticing until i stand up and discover to my satisfaction that i have gotten drunk without noticing i was drinking#that's the shit i like#if it tastes like alcohol i want it to get me drunk VERY VERY EFFICIENTLY#(thus the shots of gin)#ideally i would like anything alcoholic i drink to get me drunk very efficiently AND taste nothing like alcohol#what do i even TAG this#alcohol#story time#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#story time with star

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

different anon here, but honestly, i'd rather drink a glass of soy sauce than a glass of red wine

I feel so unbelievably validated, anon.

White wine, I will drink (mostly, exceptions exist)! I will occasionally even drink pink wine! But I would slam straight white vinegar over red wine.

#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#alcohol#obviously champagne is Bad and i would drink red wine first probably#and i suppose technically champagne is a white wine?#but that should be taken as a statement on my hatred of champagne not a positive note about red wine#Anonymous#asked and answered#story time with star

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Maybe your missing alcohol rant is mine, in which case...1/2 you wanted rediculous opinions on alcohol, i have you. Champagne and red wine are both disgusting rotten grape juice. Tasting your alcohol is overrated and you should let me drink my 5 alcohols, tastes like sweetness and joy but will get me drunk as a skunk in 3 glasses, in peace. Beer is disgusting and I don't know why anyone drinks it, it either tastes like puke which has had resentment and hated played into it or

2/2 or someone pissed in a bottle, watered it 3/4 the way down and fermented it. Alcohol is there to get you drunk! Let me enjoy my fruity drink that will get me trashed! Stop asking me to drink shitty things because you think they make you more adult! I am 28 years old goddamn it and making me feel bad about my alcohol choices are not going to make me want to sleep with you! All that to say, fuck champagne

YES!!!! YES! Beer and champagne both taste like rotten pointlessness, and maybe I’m just a tannin-sensitive bitch or something (coffee and I are Not Allies) but red wine is SO BAD, red wine is for COOKING BEEF and NOTHING ELSE, if you hand me a glass of red wine I am going to assume that you have made a horrible mistake and respond in the same way as if you had handed me an entire glass of soy sauce.

#alcohol#the completely arbitrary alcohol discourse#i am absolutely not joking when i say that i am more likely to drink an entire glass of vinegar than an entire glass of red wine#anyway listen for the gf's 21st birthday (lo several years ago now) we all went to dave and buster's#and i mention this because d&b's has a very good white wine sangria with like...SEVERAL shots of SEVERAL things in it#it tastes like nothing you could give it to a baby#someone came up to me to comment on me drinking a 'girl drink' while i was finishing my third sangria#and i asked him how many beers he'd had (three)#and then did the math for how many shots i'd had in three hours between all the sangria (twelve)#and apparently it was extremely satisfying to watch amiable easy-going cheery drunk!star put some dudebro in his place with one sentence#hey if i shell out for a cocktail from a real restaurant you better BELIEVE i made sure it was gonna get me drunk first#get off my back about it @society!!!! i'm never going to drink beer to look more like a bro#...anyway there's no greater power move than ordering neat gin at a bar and i often just drink straight liquor so as to save money#the respect i get from bartenders...it's intoxicating i'm not gonna lie#you can all absolutely go to hell with your 'ordering beer at a bar to seem tough' shit#Anonymous#asked and answered#story time with star

4 notes

·

View notes