#the freckled princess and the dragon

Text

Happy Valentine's Day!

#animated couples#the freckled princess and the dragon#belle#mo dao su zhi#your name#helluva boss#moxxie and millie#stolitz#arcane#vi and caitlyn#castlevania#dracula and lisa#lore olympus#hades and persephone#love#animated love#valentine's day

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

FILMS in 2024:

38 | Belle 竜とそばかすの姫 (2021) — dir. Hosoda Mamoru

#belle#ryuu to sobakasu no hime#belle the dragon and the freckled princess#belleedit#filmgifs#moviegifs#fyeahmovies#userfilm#worldcinemaedit#animanga#animationsdaily#animationsource#dailyanimatedgifs#animegifs#anisource#allanimanga#dailyanime#fyanimegifs#!gifs#films2024

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belle ; Belle ☆ Good Smile Company

#belle#belle figure#ryuu to sobakasu no hime#the dragon and the freckled princess#ryu to sobakasu no hime#pop up parade#good smile company#gsc#anime#anime figure#figure#anime figurine#figure collecting#figurine#scale figure#anime collecting#myfigurecollection#manga

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dealing with Dragons: Cimorene sketch ^_^

Been re-listening to Dealing with Dragons recently (anyone who knows me knows I will not shut up about how formative this series was for me re: many things but mostly dragons) and so I got the urge to draw Cimorene again (I sketched her like a year or so ago, but can't find it, so I thought a redesign with my new style was perfect!)

Also, my fav book reviewer (I have one of those now?? What??) Just covered the first book of the series, so if you want to check out a great reviewer AND my favorite book of all time, here's the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jMaKkwHQQKM

Not me trying to speak into existence an Enchanted Forest Chronicles graphic novel series that I get to adapt, whatttt noooo... ^_-

#enchanted forest chronicles#dealing with dragons#Cimorene#books#nostaltic books#fantasy#cool Princess#I also love her other princess friend#Morwen is also great#also so many cats#this is also where I got my CATS ARE BASICALLY DRAGONS thing#Kazul my love#what a fantastic series tho#highly recommend the audio book#if you like high fantasy with a subversion of tropes and with a fairy tale story structure#yes I know the book doesn't say she has freckles but it's my design so of course she has#this is also where I got my love of long braids

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fairy Tale: Beauty and the beast

#disney princesses#disney#beauty and the beast#belle#ever after high#rosabella beauty#The Dragon and the Freckled Princess#Suzu Naito#Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Faces in the snow" commission by @dragonfiredevil

ありがとう!

(๑˃ᴗ˂)ﻭ #BELLE

#竜ベル#belle#belle movie#belle 2021#dragon#the dragon and the freckled princess#竜とそばかすの姫#belle anime#ryuu to sobakasu no hime

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

You're telling me they're not the same characters?!?

Belle (2021) Princess Tutu (2002)

Both couples seem to have the same arc of trust

Both the Dragon and Fakir watch over their brother, one who is quite innocent, pure and kind, but they believe that they are alone in the world. And to avoid being vulnerable, they both resort to a hostile and aggressive attitude

But the princess and the boy end up connecting in a much deeper way...

And that's why I allowed myself to make a vague sketch of a version of Princess Tutu in the role of Belle (please excuse my lack of talent in this)

#fakir x ahiru#fakir x duck#princess tutu#fakiru#princess tutu mytho#belle 2021#Ryuu to sobakasu no hime#the dragon and the freckled princess#ahiru arima#princess tutu fakir

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Those Left Behind: Answering the anger of the survivors in My Hero Academia vs. Hosoda Mamoru’s Belle

Yes, it's another "What [X] Did Right That BNHA Is Doing Wrong" post. I'm not trying to make this a series, but what's a girl to do when everywhere she looks, she sees other stories that are handling elements of BNHA's endgame with far more grace and rigor? Hit the jump.

The Formula: The Hero vs. The Critic

A bugbear of mine in superhero fiction is when The Hero is presented with someone critiquing their heroism who immediately revokes their objections when The Hero saves them in turn. The basic shape of the story is as follows:

The Hero is confronted by The Critic in some situation that lacks immediate danger. The Critic has issues with The Hero’s day-saving activities. Perhaps in some earlier battle between The Hero and Some Villain, The Critic suffered property damage; they might also be an innocent bystander (or relative thereof) who was harmed in the fight. They might simply be a stickler for laws The Hero may or may not be acting in accordance with. Perhaps they even take issue with the suffering Heroes themselves endure, though in the case of this specific storyline, they’re more likely to be thinking of a different Hero in their lives than the one they’re actually confronting.[1]

The Critic presents an obstacle to the combat-focused method that is superhero fiction’s default mode of conflict resolution. They may endanger The Hero’s activities by threatening legal/institutional reprisal, or they may just be there to make The Hero feel bad about themselves. The Critic may be framed very sympathetically by the story, or they might simply be a buzzkill, but regardless of the degree of empathy the story chooses to afford them, they are a hurdle to be overcome.

The Hero is unable to cogently argue for their own position because superhero narratives are not about offering real life justifications for vigilantism. Rather, because the default mode of conflict resolution in a superhero story is being a superhero, the story circumvents The Critic’s objections by placing them in danger, offering The Hero a chance to save them.

Having thus been personally saved by The Hero (or, to put it more cynically, having personally benefitted from what The Hero does), The Critic promptly gets over all of their objections, even the ones that seemed to have been founded in well-considered ethical frameworks rather than traumatic experiences.

1: “Hero’s civilian loved one has a problem with their heroics” is a whole different story! Typically that story is used to mine for drama in The Hero’s personal life; if it’s not there to serve as an ongoing relationship stressor, it’s more likely that the civilian loved one will get over their objections as a result of seeing The Hero save an uninvolved innocent than because they are themselves directly saved by The Hero.

This, to me, is simple sophistry. “You say you don’t approve of what my saving people costs, but what if I saved you, huh? Then would you like me?” is a cheap gotcha that relies on The Critic being incapable of separating rational ethics from their direct experience. That’s not to say that ethics shouldn’t have a foundation in lived experience, of course, but one also can’t de facto rely on one’s emotional responses to dangerous, traumatic situations to guide e.g. public policy. Emotional responses are not inherently fair; they can be myopic or prejudicial. For the same reasons of impaired partiality that guide judicial recusal or juror screening, a single personal experience with being saved by a superhero cannot be assumed to write superheroes a blank check for everything they do while in costume.

And yeah, I realize that I’m being ungenerous here. I assume that the storyline above is meant to be read as The Critic lacking sufficient empathy for those The Hero saves and coming to a greater understanding of the terror and desperate need experienced by bystanders when Some Villain attacks. I can understand the general thrust of things!

Still, that story structure does not require The Hero to grow—all they have to do is endure and keep doing what they’ve been doing all along. All the growth is experienced by The Critic as they’re led to empathize, not with The Hero, but rather with the other underdeveloped side characters—or more likely bit characters!—The Hero saves. And even that empathy is usually less spotlighted than The Critic’s gratitude, which can feel especially distasteful when it feels like the story is emphasizing how noble The Hero is for saving this jackass Critic that’s been giving them so many problems, and isn’t The Critic just so thankful now that they’ve been humbled and shown the error of their ways?

It’s not a story that, to my eye, usefully challenges The Hero or The Critic, merely a self-serving narrative that assures both The Hero and the audience that The Hero Was Right All Along. I can see the appeal of the “No, you move,” flat arc as much as the next person, but that story just feels like, if you’ll forgive my crudity, setting The Hero up for easily-earned asspats.

Let’s look at some different permutations of the formula as it appears in My Hero Academia.

The Critics of My Hero Academia

Over the course of its 400+ chapters, My Hero Academia portrays a lot of criticism of the state-sponsored Pro Hero industry the story depicts. There are people who criticize the laws that form the basis of professional heroics, people who think Heroes work too hard, people who think Heroes don’t work hard enough, people who think Heroes are too commercial, people who think Heroes are a shiny façade over a corrupt and ugly reality, people whose way of life has been ruined by the rise of Heroes, and on and on.

Unfailingly (and often to its considerable detriment), the flawed but valiant Heroes of My Hero Academia continue to uphold their system and their activities as valuable, admirable, and—most crucially—the only reasonable solution to the problems created by the superpowers wielded by the setting’s inhabitants. Any Critics they face are destined to be proven wrong; neither the Heroes nor the author have any real desire to explore meaningful alternatives to the Hero System. Many of its Critics are thus presented as cynics operating in bad faith or outright Villains who only resent the Hero System because it makes their criminal activities harder!

However, there are Critics who are treated as more valid by the narrative: those whose objections to Heroism are rooted in the family bonds and/or love and care they hold for specific Heroes. It’s this type of Critic—and MHA’s response to them—that I want to look at in more detail.

> Case 1: Izumi Kouta

Kouta is the single most clear-cut example of the “The Hero saves and thus convinces The Critic” narrative the series has to offer, as well as foreshadowing much more extreme damage in other characters the audience will meet later on. An orphaned child whose parents died in combat with Some Villain, Kouta has grown resentful of Heroes and surly towards the society that worships them. He doesn’t understand why a bunch of strangers were so important that his parents would choose to prioritize those strangers over their lives with him. Deku The Hero has no idea how to address this, and therefore roundly fails in his first few attempts to verbally engage with Kouta.

It’s not until Some Villain[2] shows up to menace Kouta with the threat of gruesome murder that Deku’s able to connect with him. Note how this scenario puts Deku back in his comfortable heroic wheelhouse. Sure, he breaks a bunch of bones in the process of fighting Muscular, and it hurts a whole lot, but beating Muscular does not require Deku to triumph in an ideological battle; he simply has to be the best at Punching Really Hard. It’s quite straightforward and simple by comparison!

[2] As it happens, the same one who killed Kouta’s parents, but that’s an incidental detail; the narrative would have gone the same way with any Villain who was willing to threaten the life of an uninvolved child. My Hero Academia simply has a surprisingly low number of Villains who fit that criteria.

Does being the best at Punching Really Hard actually address Kouta’s ideological problem with his parents choosing Heroism over being with him? Well, no. Kouta simply pivots into idolizing Deku and never brings up his parents or his trauma surrounding their deaths again. Having come to understand how much it means to be Saved, Kouta gains a new appreciation for the value of Those Who Save, but this valuation is entirely focused on the Hero who saved him, without resolving the question of why said Hero is valuing the life of some stranger over his own familial bonds—and whether it’s correct for The Hero to do so!

My Hero Academia simply doesn’t care about Kouta as anything other than a vehicle for allowing Deku to feel confident and proud in his chosen career, and thus its portrayal of Kouta as Convinced Critic fails to escape the clang of intellectual dishonesty so frequently present in narratives of the type.

Sidebar—The Case of The Critic as Family:

Midoriya Inko Inko’s opinions on Deku’s heroics present an obstacle twice, with the former instance being much more compelling. Her confrontation with All Might is much closer to the “Hero’s civilian loved one has a problem with their heroics” story I mentioned previously in a footnote, but with a major shift that pushes her closer to The Critic’s role: Deku’s age. If Deku were an adult, Inko’s objections would simply be fodder for relationship drama, but him being a minor means Inko has a degree of parental authority she’s capable of wielding in his life—over his objections, should she choose! This allows her to pose a very direct threat to his further ability to engage in heroics.

In the end, however, the obstacle is resolved in mostly the standard way of the loved one objector. Deku’s prior rescue of Kouta—and the fan letter Kouta sent him as a result—is used to prove firstly the value to others of Deku’s Heroism and secondly the personal fulfillment Deku derives therefrom, leading Inko to back down after making both Deku and All Might promise to be more mindful of their lives when facing danger.

Both will go on to disregard this promise almost entirely, of course, but by the time Inko’s objections resurface post-Jakku, their potential impact has been firmly diminished: Deku has gained resolution and power such that nothing Inko could say would stop him from leaving, and so her objections no longer pose a meaningful threat to his heroism. Indeed, her role is so diminished that said objections don’t even rise up to the level of a relationship stressor or something to make The Hero feel bad about himself—she’d have to actually interact with Deku or be present in his thoughts for either of those to be the case, and, post-hospital, the story allows her neither.

> Case 2: Shimura Kotarou

“Heroes hurt their own families just to help complete strangers.” Kotarou is a man who sees himself as having been abandoned by his mother in favor of Heroism. Even though she left him a letter about how he was in danger because of a “bad man” she had to go and fight, even though he almost certainly knows that battle took her life, he blames her for his horribly traumatic abandonment. His grudge likely goes even further, too: given both the woeful shortcomings of Japan’s alternative childcare system[3] and his own personality as an adult, I would be shocked if Kotarou’s subsequent upbringing wasmarked more often by joy and belonging than by pain and alienation.

3: Which, I note, has not been so improved in the rosy glow of the heroic future that a monster like Ujiko was unable to get a foothold in it.

In Kotarou’s eyes, even if Some Villain was endangering him, that was only happening because his mother was a Hero to begin with. If she hadn’t chosen that career, made that enemy, Kotarou would still have both parents, and he wouldn’t have grown up in an almost certainly overcrowded children’s home with the deep societal stigma of being an "orphan “unwanted child” knotted around his neck.

Unlike the other examples of this type of Critic in the story, Kotarou’s bitterness is never assuaged. Instead, down to their strikingly similar names,[4] he serves to illustrate a possible dark ending of how Kouta’s life might have gone if a Hero had never (oh-so-Heroically) gotten him through his wrongheaded (per the narrative) stint as a Critic. And though Kotarou’s life was ended as a direct result of that resentment, it also outlives him, winding itself into the deepest roots of his son’s equally venomous opinion on Heroes.

4: A disclaimer: Their names are less immediately similar in the Japanese, where Kou and Ko are given entirely different kanji (洸 and 弧 respectively). The ta parts of their names, while also using different kanji, do have a base radical in common: 汰 and 太 both include the 大 radical. That's certainly close enough for wordplay jokes to make sense, even if they're not as close as the official rendering of the names (Kotaro and Kota) makes them look.

> Case 3: Shigaraki Tomura

Shigaraki is MHA’s other key invocation of the Hero vs. Critic narrative, though his permutation is quite different from the norm by virtue of the fact that he is also a Villain. While his own critique of Hero Society is in the “shiny façade covering its true ugliness” camp, Shigaraki also adopts his father’s beliefs as his own, echoing Kotarou’s definition of a Hero at Jakku. Notably, this was part of a speech delivered to a bunch of Heroes who, seeing as they themselves were the danger he was facing at the time, were considerably less nobly determined than usual to Save The Critic!

At the time, Deku had neither an answer to Shigaraki’s accusation nor even the willingness to grapple with it. As of this writing, while he’s much more invested in understanding Shigaraki’s pain, but he still lacks an answer to the root causes of it. It remains to be seen what exactly he’ll come up with, but at current, he remains stoutly determined to treat Shigaraki as nothing more than a shell over the Crying Boy that Deku believes remains at Shigaraki’s core. This is none too promising in terms of doing anything to challenge the standard Hero vs Critic narrative! The premise that Deku will save Shigaraki functionally demands that that “saving” (whatever form it winds up taking) will in and of itself end the opposition Shigaraki currently poses.

The Critic obstructs The Hero. The Hero saves The Critic. The Critic no longer obstructs The Hero.

And then The Hero goes on being the main character, while The Critic passes without protest into the rearview mirror as The Hero’s story moves on.

Let’s take a look at a story that dares to try something different with that over-familiar narrative.

Hosoda Mamoru’s Belle

Naito Suzu is a girl who lost her mother to Heroism, and Suzu has never forgiven her for it.

Immediately, the change of focus electrifies. The main character of Belle is not a Hero who must prove herself to a Critic; she is The Critic!

Or is she…?

To get a bit more detailed, when Suzu was a child, no more than six years old, her mother strapped on a lifejacket and, over Suzu’s protestations and pleas, waded into floodwaters to save a stranded child. The child, put into that same lifejacket, was pulled out of the river by other bystanders. Suzu’s mother was not. In the young Suzu’s eyes, her mother gave up their life together to save some stranger.

Over a decade later, Suzu still hasn’t come to terms with that. She loves music—a pastime her mother encouraged—but now its association with her mother means that Suzu can’t sing without feeling a visceral nausea that leaves her retching and shaking with all that unprocessed fury, grief, and frustration. She’s introverted at school, with only two close friends, and her relationship with her father is distant and awkward.

This is the state of affairs when one of Suzu’s friends ropes her into trying U, a bonkers virtual reality playground/social media platform/fantastical internet-alike that’s taken the world by storm. In U, hiding behind a digital avatar with the face of a Disney princess,[5] Suzu finds that she can sing without being wracked with panic and distress. Before long, and with her savvy friend’s help, “Belle” is a full-on internet sensation, giving virtual concerts watched by millions. It’s when one of those concerts is crashed by a mysterious and much-maligned user called the Dragon that the real plot kicks in.

5: Literally; Suzu’s online avatar was designed by Jin Kim, a longtime Disney animator and character designer.

It’s from that point on that Suzu begins to shift. Recognizing in the Dragon a fellow wounded soul, she’s drawn to find out more about him. When a real-life crisis of the ugliest kind finds him, she risks everything she and her friend have built so that she can find and save the boy behind the Dragon—a boy she has never met. It’s only after Suzu has made that leap—when she is staring into the void, not yet knowing how she’ll land—that she has the epiphany: This is what her mother felt. This is why her mother acted as she did.

The movie still has some places to go in seeing Suzu’s gamble through—saving the Dragon is a major plot element!—but the other main plot element, the story of how Suzu reconciles and finds closure with her mother’s death, climaxes there in that moment of truth. Whatever else there is to say about the film’s perhaps overly faith-driven resolution of Dragon’s plot (and there is, to be sure, a lot to say), its resolution to Suzu’s positioning as The Critic in regards to the actions of her Hero mother is a perfectly elegant, sublime solution to the problem, convincing me of The Critic’s turn in a way no other story ever has.

In My Hero Academia, as in so many other traditional superhero properties, Critics are present as obstacles for the Heroes to overcome. The story does not care if those Critics understand the Heroes themselves; it merely wants them to accede that the Hero is right and they are wrong. It puts problems in their path that it insists only The Hero can solve and thus browbeats Critics into acceptance.[6] Far from presenting any alternate paths for The Critics and The Heroes to come to an accord, the story uses the specter of gruesome death—Kotarou’s death at the hands of the son his anti-Hero stance led him to abuse; Muscular’s gleefully murderous rampage—to leave Critics with no other choice: Validate Heroes or die. And the audience is, very clearly, intended to read this blatant false binary as intellectually honest and emotionally rewarding.

6: This pattern becomes even more egregious if you expand the lens from Critics who are grappling with the actions of Heroic family members out to the more traditional Critics whose issues resolve around collateral damage. Look at the scornful holdouts Shindo and Tatami encounter, for example, or the angry journalist woman whose mother was hurt in Gigantomachia’s rampage, both of whom recant their skepticism after witnessing the scale of the threats Heroes face. You see echoes of the pattern in the final arc as well, wherein Endeavor’s fanboy comes back around on Endeavor as a prelude for skeptics all around the globe being moved to prayer by All Might’s grotesque battle against All For One.

In Belle, on the other hand, The Critic is not overcome by being saved themselves. Indeed, while Suzu is saved at one point (some of Dragon’s AI creations help her escape from U’s peacekeeping force, a group as self-righteous as they are self-appointed), not for one instant does that experience cause her to mentally align herself with the feelings of the child her mother saved. Rather, the story puts Suzu in a situation where she must save another. Thus, she reconciles with The Hero not because the plot corners her into becoming a Victim in need of help, but because her own actions bring her to a place of true empathy. She validates The Hero’s past actions because, in her own moment of crisis, The Critic herself becomes The Hero.

Would that superhero stories like My Hero Academia could treat its Critics with even a fraction of Belle’s respect for Suzu’s interiority and agency.

#bnha#the dragon and the freckled princess#mamoru hosoda's belle#bnha critical#my writing#continuing my dubious drawing of parallels between vastly different genres of story#next time: why laios dungeon meshi is a better nerd main character than deku academia#(probably not really but I just want you all to know that if I wrote it I would be right about it)

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

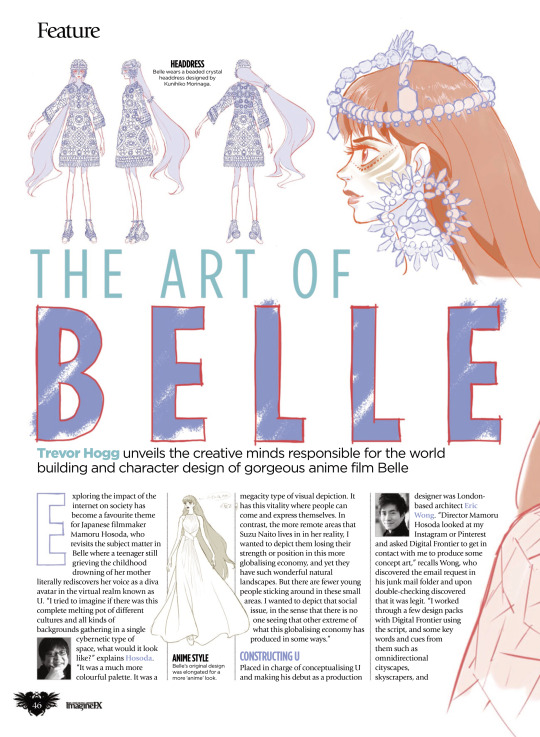

"Belle"- featured section from the magazine "ImagineFX" Issue 215

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Don't look at me"

#fanart#ryuu to sobakasu no hime#belle 2021#belle movie#belle anime#mamoru hosoda#the dragon and the freckled princess#ryuu#dunno if the fandom still exist

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

🐚

#more of my fibshy#zora oc#keve#peachstarfall#legend of zelda#digital art#her singing voice is belle from belle: the dragon and the freckled princess#iykyk

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#anime#belle#ryuu to sobakasu no hime#the dragon and the freckled princess#movie#beautiful art#kiss#monster#beauty and the beast#gif#my edits#blueraimo

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first song cover!!!

I just released my first ever song cover on youtube!!!! Gales of Song from the movie Belle!!!!!!

youtube

This is the first ever song cover that I have done, and I also had to record and edit myself so please keep that in mind while listening, but I really hope you guys enjoy!!!

The thumbnail was drawn by my lovely friend @thenightgazers please give them a follow they are literally the sweetest person I know!!!

Enjoy the song!!!

#song cover#singing#singer#dragon sings#gales of song#belle 2021#the dragon and the freckled princess#suzu#youtube#dragon rambles#animation#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feeding my very few Belle children

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

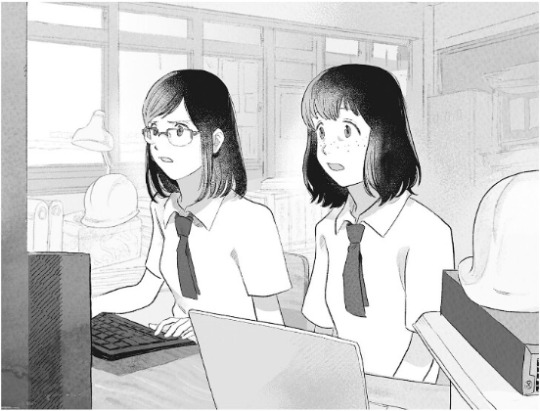

Hiroka Betsuyaku and Suzu Naito from Belle (2021)

#belle 2021#Ryū to Sobakasu no Hime#the dragon and the freckled princess#suzu naito#hiroka betsuyaku#media: image#media: self made#ue: tilda

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bell's Songs

"U" is a tribute to U, a celebration to the ability to start anew -in a way- and connect with so many people.

"Gales of Song" was written and sang for her mother, her loss and Suzu's inability to move on.

"Lend Me Your Voice" is a love song, asking for connection and trust between Belle and Dragon - Suzu and Kei.

"A Million Miles Away" is a song for return and reconnection, of faith and rebirth, of finding strength and realizing you already had it inside you.

#Belle#竜とそばかすの姫#The Dragon and the Freckled Princess#Ryū to Sobakasu no Hime#Ryuu to Sobakasu no Hime#movies#Belle's songs were so dang beautiful#and no I did not misspell the name on the title

24 notes

·

View notes