#the unreliable narrator of his own story . ( self promotion . )

Text

AT NIGHT, I leave the lights on in my little house and walks across the flat fields. when I look back from a distance the house is like a boat on the sea. it's really the only time I feel safe.

credit.

#the unreliable narrator of his own story . ( self promotion . )#will graham rp#hannibal rp#nbc hannibal rp#indie rp#horror rp#crime rp#detective rp

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

...okay, so I know nothing about Dexter except he's like the but what 'if I kill a 100 killers?' meme, but what I DO know is him looking like a homeless lumbercjack in snow cause fandom had a meltdown over it - AND YOU TELLING ME HE'S IN MIAMI CAUSED ME TO QUESTION REALITY! D: [And hey, if you'd wanna advertise me the show my ears are open... xD]

RIGHT? Totally different vibe. Beard!Dexter is a blight on this fandom, for legit reasons other than just facial hair and snow, but those are still unforgivable in their own ways lol. I mean, Dexter's promotional material was a pretty cool mix of playing on his job as a blood splatter analyst (oh ho ho did he cause the splatter?) and playing on his outward image as the supposedly perfect family man (the ketchup he's using is actually blood!), but we also had stuff like this:

The setting is really crucial. If we were set wherever we are at the end of the series (I clearly loved the ending enough to remember where he moved to lol) that would very much mirror the whole serial killer thing; a dark, cold environment to reflect his real self. But by making it Miami, there's this wonderful contrast going on that feeds into both the show's premise — totally normal dude goes about his normal life in this bright, happy, gorgeous weather place — and, by extension, feeds into the show's humor too. It's harder to take Dexter seriously when he's out being all serial-killer-y in a Hawaiian shirt... and alongside enjoying that image, we understand, textually, why no one really suspects him. You know that post going around where OP shows that shot of Hannibal being all creepy in his library and it's like "Oh yeah there's NO WAY anyone would EVER think you're a SERIAL KILLER, guy whose name rhymes with 'cannibal.'" Dexter is the exact opposite of that. At the start of the series one coworker thinks he's shady — presenting expected problems for Dexter — but he's very much the outlier. You don't have to suspend disbelief to go along with everyone trusting, liking, and even loving Dexter. He is lovable.

And that's the cool moral premise. I mean yeah, he's a serial killer. Insert the inevitable tumblr comment about how you can't like the bad guy (/s)... but you're supposed to. Dexter starts the series with a wife, kids, beloved sister, friends at work, and he does love them all. It's not an act put on to get by. The show is very clear that the persona Dexter embodies to not get caught, while inevitably tied up in that Good Brother/Husband/Father lifestyle, is not the sole reason why he created those ties. The premise of Dexter is not "If a killer kills a killer, there are still the same number of killers on Earth, I am so intelligent." It's "What if a cop realized his son would inevitably become a serial killer, so out of love for him taught him to only kill other people who were a danger to the community? And then the son grew up desperately trying to maintain the life he'd built while also keeping his "Dark Passenger" at bay? Would that be fucked up or what?" Dexter is interesting both because he has his code — there are legit conversations to be had both in the story and out about what, if any, merit there is in this kind of vigilante behavior. It reminds me of a similar Criminal Minds episode where a victim hopes a killer won't get caught because he killed her abuser — and because he, outside of the whole killing thing, is a pretty likable guy. You're suppose to struggle with liking him, question what it means to be a monster, figure out what you're willing to ignore for someone you love, etc. Dexter isn't the Joker reveling in chaos for the sake of chaos, nor is his struggle such an angst fest that the show (at least most of the time) feels too edgy. He treats his "Dark Passenger" like a particularly annoying pet he has to take care of. Yeah, it gets dark and serious a lot, but it's also funny as hell.

All of which is made better by casting Michael C. Hall. He's phenomenal in the role.

I don't think any clip encompasses this tongue-in-cheek "He's just a normal dude, doing normal things, definitely nothing to see here ;)" energy quite like the opening does. It PERFECTLY uses the context the viewer has to make everyday actions seem sinister and then contrasts it all with the final shot: how everyone else sees Dexter. It is, totally seriously, one of my favorite openings of anything ever:

youtube

Absolutely watch Dexter. Yes, there comes a time when it goes off the rails and the finale is up there with the likes of Supernatural imo, but you can ignore that + the new season might fix some things if we're very, very lucky lol. If you enjoy police procedurals, monster of the week formatting, morally driven storytelling, unreliable narrators, and fantastic ironic humor, Dexter 100% deserves your attention.

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

16, 52, 67, 99, 134

16 - A book you'd recommend to your younger self

There's always the thought that "if only I'd read that book back then, I might have avoided that particular bad decision", but I think that's just wishful thinking. What you get out of a book when you read it, depends heavily on your own experiences and the mindset with which you approach the story, and you cannot force people into some kind of early maturity just by exposing them to literature they lack the framework to understand.

However, I do regret that it took me so long to pick up Howl's Moving Castle, because I think I would have enjoyed it just as much ten years ago.

52 - A popular book series you love

Apart from the obvious answer (LotR), I'd say the Locked Tomb series (Gideon the Ninth, Harrow the Ninth), though I'm not entirely sure to what extent it counts as popular beyond the fact that my local fantasy/sci-fi bookstore promoted the hell out of Harrow the Ninth when it was published. There's just something about the blend of biblical and mythological allusions, themes of shame/guilt/sacrifice, whodunnit mysteries, unreliable narration, vivid descriptions of anatomy, and modern internet memes, that ticks all the boxes for what I didn't even know I was looking for in a book series.

67 - Your favourite historical fiction novel

A Place of Greater Safety, hands down.

99 - A book with a strong female protagonist

His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman. I am not overly fond of the "strong female protagonist" concept because it has become a marketing gimmick for books that don't let its female protagonists be anything but cardboard cutout "badass" action heroes with little agency or personality. Lyra from HDM is strong in the other sense of the word; she moves the plot forward on her own, she is allowed to be a whole person with flaws and doubts without being condemned for it by the narrative.

134 - Unrecommend any book you'd like

The Black Opera by Mary Gentle, which promised 19th century alternate history and music, and gave me the average New Atheist Internet Smartarse as a protagonist, but with the added ridiculousness of him having this science-over-superstition attitude when he literally talked to the ghost of his dead father on a regular basis. Additionally the writing was tedious. I gave up after about 200 pages. Don't read it.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three Caballeros at 34

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

Mickey Mouse is, and always has been, the face of the Walt Disney Corporation. Perhaps it’s because of legacy or favoritism, because Donald Duck has often proven himself more popular. To expand on a quote from Walt Disney, it all started with a mouse, but a duck pays the bills. Never was this more apparent than in the 1940s.

As morbid as it seems, World War II was a great boon to Donald Duck’s popularity. Mickey Mouse represented an unflappable, upbeat everyman. He became popular during the Great Depression when people needed their morale lifted. Donald Duck was an angry fighter who got knocked down, and stood right back up, fists swinging. That sensibility was celebrated by many during the war. Seeing the influence he had, Walt Disney capitalized on his creation.

Donald was commissioned by many sources during World War II. The US Treasury, the United Way, and the Canadian Film Board all commissioned cartoons from Disney Studios. His likeness was merchandised in countless other places. Within months, Donald Duck was promoting war bonds and celebrating American resilience coast to coast.

Later, Donald joined the US Army, encouraging enlistment. As an act of patriotism, Disney produced seven of these shorts at cost for the armed forces. Why he opted for Donald to join the Army as opposed to the Navy, as is often suggested by his sailor outfit, is a mystery. Donald wasn’t the official face of the war effort, but not for lack of trying.

In 1944, three separate events lined up. First, World War II was still ongoing. Second, Disney Studios was celebrating Donald’s tenth anniversary. Third, the follow-up to Saludos Amigos was nearing completion. It was time for another cinematic saga of comradery in the western hemisphere, this time featuring Donald Duck front and center.

Saludos Amigos was a rush job. Disney Studios churned it out for immediate financial returns. The writers and animators had unused ideas leftover. Some ideas were more dynamic and required money and time, not available in 1941. Now with a foot-hold on the Latin American film market, the studio was able to make a proper follow-up. That was The Three Caballeros.

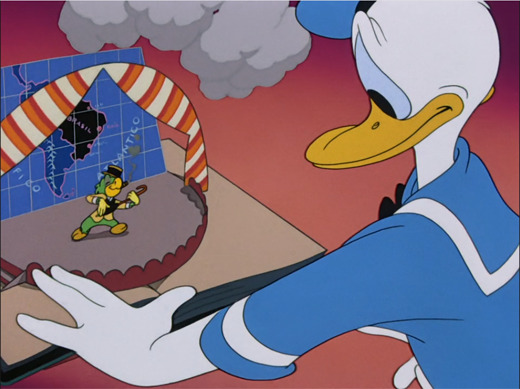

The Three Caballeros uses the 10th anniversary of Donald Duck’s creation as a framing device. Throughout the film, Donald opens a multitude of gifts from friends and well-wishers. Each gift prompts or frames a new vignette. Like Saludos Amigos, the vignettes of The Three Caballeros were created to foster international goodwill between Latin America and the United States.

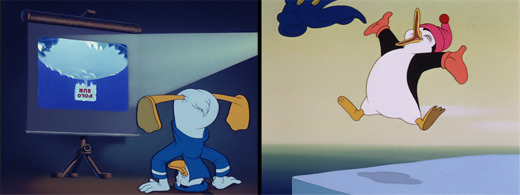

The first gift is a projector and film canister. The movie is The Cold-Blooded Penguin. It features a penguin named Pablo who dislikes living in Antarctica. Pablo hates the cold, and wishes to live in a tropical climate. One day, he pools his resources, and sets out on an ice floe for warmer weather.

Astute readers will notice the error immediately. What on Earth is a cartoon about a penguin doing in a film about Latin America?

It’s true, Pablo’s journey takes him around some of the coastal geographic features of South America’s west coast. These aren’t so much landmarks as name drops. We hear the narrator mention the Straits of Magellan, Cape Horn, Juan Fernandez Islands, Vina Del Mar, Lima, and the Galapagos Islands. But what’s depicted onscreen are rather nondescript landforms. These could be any straits, any coasts, and any islands.

The Cold-Blooded Penguin’s ties to South America are incredibly tenuous. Plainly, it does not belong as part of the film. So much so, it’s not even worth commenting on the animation or story. You could make the greatest rotisserie chicken in culinary history, but if you serve it atop an ice cream sundae, no one will care how the chicken tastes.

The short shamelessly tries to mask itself as an extended cutaway from a larger feature called “Aves Raras,” or “Rare Birds.” The non-penguin half of this short does indeed focus on the indigenous fauna of South America. Somewhat farcically, but also with an informative nugget. This infotainment is what The Three Caballeros aspires to be, and achieves in certain quantities.

Unfortunately, the filmmakers either get lazy or distracted. Strewn among the cultural aspects are nonsense and unsupportive jokes. Either the filmmakers were padding the film or afraid of losing the attention of a younger audience. The end result bogs down quality with unnecessary jetsam.

The highlight of the Rare Birds segment is the Aracuan Bird. This bird has a high-pitched, sped-up voice, and a warbled laugh. He has a screwball sense of humor, and an innate ability to antagonize all those who he comes into contact with. He has a bright red crest, a yellow beak, and oversized eyes. He debuted four years after another cartoon bird with alarmingly similar characteristics: Woody Woodpecker.

Woody Woodpecker first appeared in the 1940 short Knock Knock. Walter Lantz created the character, and licensed him to Universal Studios. The similarities between The Aracuan Bird and Woody cannot be ignored. I can find no information explaining this coincidence. There were no complaints filed, and no legal action by Lantz or Universal. It’s rather unlikely Disney’s animators resorted to plagiarism; we can only assume it was an unintentional, subconscious reproduction.

The Aracuan Bird appears here, and in two more brief scenes. He then disappears for the remainder of the film. One would think he would be a running gag, appearing regularly throughout the movie. Or at the very least, he would be a main feature in his own vignette, his other appearances being callbacks. He would certainly be more on-theme than The Cold-Blooded Penguin.

The Aracuan Bird is an unpleasant reminder that The Three Caballeros was a pile of ideas leftover from Saludos Amigos. He is introduced, then subsequently forgotten. The movie was the production of different animators and writers, working independently. They each had their own ideas, and didn’t seek consultation. These ideas are threaded together as best as possible, but big gaps in style and substance exist.

The next vignette is The Flying Gauchito, set in the pampas of Uruguay. It is the story of a child, looking for the approval of the gauchos of his village. The boy goes on a hunting expedition, finding the rarest game of all: a winged donkey.

The donkey is named ‘Burrito,’ the Spanish word ‘Little Donkey’ (which existed long before the popular Tex-Mex dish). Gauchito returns home with his newly acquired winged steed. Rather than show him off, Burrito is entered in a horse race. It’s one thing to show-off your luck. It’s another thing to demonstrate your worth.

What makes The Flying Gauchito special isn’t its story. Will and determination overcoming the established norms is a common moral. The true strength of the short is its utilization of an unreliable narrator. Gauchito’s journey is narrated by his older self, narrating from an omniscient standpoint in the future. It would be easy for him to tell the story accurately. Instead, he’s forgetful, indecisive, and admittedly unsure of specific details.

This narrative style creates not only a humorous structure, but humorous accompanying animation. Whenever a detail is “corrected” or second-guessed, the corresponding imagery is swapped out. In quick succession, the characters onscreen are left helpless as their world is ad hoc corrected. They must endure a shifting landscape and environment before they can react accordingly. This gives them a sense of instability, like they’re wearing roller skates, or walking a tightrope. It’s an advanced narrative technique, and it’s executed well.

With two and a half shorts finished, Donald Duck moves onto his next present. Inside is his friend and Saludos Amigos costar Jose Carioca. Jose is just as jovial and passionate as ever, but now smoking a giant cigar shamelessly for all children to see. We’re a long way from the warnings of Pleasure Island.

Jose introduces Donald to the Brazilian city of Baia. In a combined mood of nostalgia and admiration, Jose begins a long musical serenade. As his memories and thoughts are manifest to reality, we are swept away in the romantic imagery. The pinks and purples of the city at sunset are wonderfully done.

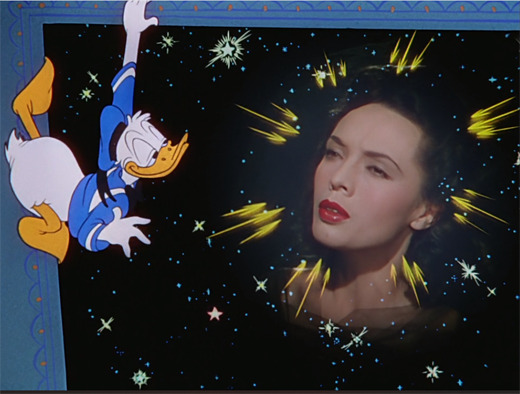

The two avian friends find themselves at a celebration on the streets of Baia. They’re joined by singer and dancer Aurora Miranda, plus a small army of samba dancers. The interplay of cartoon and human is outdated by today’s standards, but to an audience in 1944, it must have seemed groundbreaking. The technique is used extensively throughout the remainder of The Three Caballeros, and to great effect. It’s a gimmick, but a gimmick employed and accomplished well.

Exiting the glory of Baia, Donald opens his next gift from a stranger in Mexico. The unfamiliarity is temporary. Inside the gift is the loud, ecstatic, pistol-packing Panchito Pistoles. This firebrand is so eager to meet both Donald and Jose, he declares the trio “The Three Caballeros.” Finally, forty minutes into the picture, well past the halfway mark, we meet the last of our title characters.

After a fiery song and dance number, Panchito introduces Donald to the piñata. Panchito identifies it as a Mexican Christmas tradition (The Three Caballeros was scheduled for a December release date). Until this point, Panchito has been a quite vocal and boisterous individual. Hearing him tell a reverent and humble tale of Christmas tradition displays his hidden depths. Panchito could have been a shallow and one-note character. Instead, we see him capable of many things.

Cracking open the piñata, Donald is treated to a tour of Mexico’s most popular sights. Panchito summons a serape, which flies like Aladdin’s magic carpet. The Three Caballeros visit the exotic locales of Pátzcuaro, Veracruz, and Acapulco.

Until this point, both Donald and Jose were nothing more than enthusiastic partygoers. They enjoyed the celebrations and sights of their destinations. And they never shied away from the pleasant company of a gorgeous woman. For whatever reason, upon visiting Mexico, something stirs in the mind of Donald.

Going forwards, every woman Donald encounters is an object of lustful desire. Singing girls, dancing girls, sunbathing girls; Donald wants them all. Jose and Panchito do their best to subtly remind Donald he is a cartoon duck in a G-Rated movie, but Donald is driven by his id.

It’s a common cartoon trope for a character to be so blindsided by a woman’s physical attraction, they lose control. From the works of pre-Hays Code Betty Boop shorts, to the then-contemporary Tex Avery, it was a well-established joke. Donald, however, is completely insatiable and unstoppable. It starts funny, gets ridiculous, and then turns downright disturbing. Donald Duck is insatiably in love with these Latin beauties, and cannot be tamed. It’s a running gag that runs far too long. Panchito shouldn’t have shown Donald a hot beach, he should have shown him a cold shower.

The movie ends in quite an interesting way. Instead of a traditional song and dance number celebrating Mexico, the remaining twenty minutes of film is a surreal, avant garde display. More than ‘Toccata and Fugue’ from Fantasia. More than ‘Pink Elephants on Parade’ from Dumbo. Things are odd, formless, wild, and baffling. And lots of fun.

The Three Caballeros’s primary problem is how unbalanced it is. Any ten minute stretch is vastly different from any other. But it is unbalanced in a linear fashion. As the movie progresses, it becomes more cohesive and more audacious. Things are always building towards the (literally) explosive climax.

It begins with one short that doesn’t belong in the film at all. It moves onto a second short that, while more appropriate, could easily be excised. Jose is introduced, giving the movie more structure and narrative harmony. With him, more advanced animation techniques are employed. Panchito is introduced, giving the film a solid shape and definition. Finally, we’re treated to a grand tour de force. Disney’s animators use every trick to deliver a mindboggling trip for the eyes and ears.

The Three Caballeros as a group existed as Disney second-stringers for many years. Donald Duck remained as popular as ever, but it was rare to see Jose or Panchito acknowledged by the studio. Early in the 21st century, the cult popularity of the film prompted a resurgence for the forgone trio.

The Three Caballeros are featured at the Mexican Pavilion of Epcot Center (despite only one of the three members being Mexican). Don Rosa wrote two sequels for the trio, published in comic form. They’ve appeared in Disney television shows, such as House of Mouse, and 2017′s DuckTales. They even star in their own series on Disney+, where they become globetrotting fantasy heroes.

The Three Caballeros expands on the ideas of its predecessor, Saludos Amigos. A multitude of animation techniques continues the celebration of harmony in the Americas. Music, laughter, and a love of exploration unite us all. While the end result is something of a mixed bag, the highs are demonstrably high. It will stimulate some viewers while outright confounding others. But in the end, the wild, surreal adventure is a voyage worth taking. Hasta luego.

Fantasia

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Pinocchio

Bambi

The Three Caballeros

Dumbo

Saludos Amigos

#The Three Caballeros#Walt Disney#Walt Disney Animation Studios#Disney#disney studios#Film Criticism#film analysis#review#movie review#Disney Canon

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perspective: Did Villanelle’s character arc in Season 3 get lost in translation?

Killing Eve Season 3 became something of my object of fascination by the odd disjointed experience I have watching it. It feels like it makes sense at first, but the whole lot is rather off. The more I revisit it, the more it appears that what we see on the surface is but an attempt at telling a very different story. But precisely by failing to convey their intended story (Or not committing to), the authors inadvertently created a slate with enough inconsistencies that it fits any rationalization the audience wants to impose on the final product. Its lack of clarity and internal logic made it adaptable to several points of view. I can impose the interpretation that Villanelle was given an irreconcilable redemption arc, or that she is still a psychopath and it will still somewhat work.

However, when the season is consumed stripped from our expectations, there is a dissonance between the narrative and the other elements of storytelling which sends mixed signals, especially in the most developed storyline in the season: Villanelle’s character arc. In the midst of this confusion and inability to get a hold of the character, I tried to grasp the intent of the author instead of the material itself. Upon reading interviews with Suzanne Heathcote, Sally Woodward and Jodie Comer, many of my initial interpretations of her arc were challenged. They seemed to never seek to rectify Villanelle’s psychopathy or nature, but to explore her deep need to belong. There seemed to be an awareness towards the truth of the character, and the journeys they have been on so far. It appears that their idea is that her impulses are her true self and the tension arises from the inescapability of her own nature and its exploitation, which becomes the sole designator of her worth as a being. This is indeed much more interesting than what I initially interpreted. So, I want to revisit Villanelle’s character arc with new eyes... in more detail... and see if I can find something new.

Villanelle’s initial motivations set-up a “ Self-affirmation” arc, not a Redemption arc

Initially, the show seems to set two main motivations for Villanelle: a search for autonomy and a search for belonging, which will prompt her desire to become a keeper and find her family. Objectively, her motivations set up a journey for authentic self-identity.

The opening wedding sequence is a good way of introducing her search for autonomy. Six months after Rome, Villanelle is gold digging her way through life, still very psychopathic of her. This is the first time we see Villanelle exist without a parental figure and without the tight control of ‘The 12’, and it turns out she is doing just fine. Where her wedding represents her agency and autonomy, being dragged into ‘The 12’ by Dasha has her sitting in the back of the car like a moody toddler. Her relationship with ‘The 12’ is infantilizing, controlling and coercive. It does plant the seeds for her struggle by visual storytelling, which I dismissed for a silly comedic effect.

Villanelle seems more aware of the power plays behind her bargain to come back, contrasting with her previous aloofness. This time, she seems keen on cutting her own part of the deal which is to become a Keeper (which oddly never involves getting the names of ‘The 12’). Her request is so absurd, and their agreement to make her a keeper so obviously fake, that it shows how Villanelle is truly unaware of the magnitude of what she is dealing with and how little leverage she actually has. But her effort to carve some degree of freedom and agency within her world is an authentic motivation. Her overall disinterest for the job also helps to solidify the idea that she is dreading being controlled, and only agrees to perform the kills as part of her promotion process. Which should not be confused – although it easily is – with a lack of enjoyment in Killing. In fact, Villanelle thoroughly enjoys herself in the kills she performs before Episode 5, be it improving on a relic, stealing a baby, or scaring hiccups away. Villanelle isn’t opposed to killing, she is tired of being ordered to kill. As welcomed as this development is, in many moments her motivations could be mistaken by childlike Villanelle just being capricious.

Parallel to her self-affirmation comes a search for a sense of belonging. This is a deep foundational motivation for the character that had always been in the subtext of the show. There is a fascination towards family and normal life in Villanelle, that she tries to recreate with those she “loves”. Arguably not even the character can articulate this urge, so when Season 3 sets to explore it, it feels forced. Villanelle seems intrigued by the gratuitous affection the baby elicits in people, including those that don’t own it, leading her to kidnap the baby as an experiment, then literally toss it away. It did not elicit in her the gratuitous affection it elicits in everyone around her. She is a psychopath. When the baby is reunited with their father, she is once again puzzled at the happiness in the dad’s face. The baby belonged to him. Did she ever belong to someone? This question will lead her to seeking her own family, taking her to Russia.

Being so far removed from the events of season 2 and considering that Konstantin and Villanelle’s scene was completely overshadowed by the subsequent events, I found it hard to add weight to this motivation. A large part of the audience is understandably eager to learn about Villanelle’s past, however there wasn’t enough development to justify why the character wanted to learn about her past. Instead, she enunciates her newfound fascination with babies, without elements or events to convincingly move the character in this direction.

Villanelle’s journey home: nuanced and conflicted story telling got lost in translation

I have broken down how I believe this episode not only retcons her background, but soft retcons Villanelle’s psychopathy and her entire character – and I still believe in practical terms it inevitably does - but it’s a shame, because the episode in itself doesn’t. It’s all about perception and expectation tainting interpretation. The writer’s original idea was to have the audience go on a journey with Villanelle to this disconnected corner of the world, as she is surprisingly charmed by the oddity of what she finds. It was the perfect escapism from her claustrophobic world of ‘The 12’. We wrestle with the nature x nurture question as Villanelle wrestles with it herself, we feel at home, we connect with the family and feel rejected and deceived as Villanelle does herself. This episode was written from Villanelle’s perspective alone, she is the voice telling the story, we are literally asked to see it from her eyes:

But there is a catch: Villanelle is an unreliable narrator. The writer did plant elements that challenge Villanelle’s narrative, mainly as glimpses of other characters perspectives: Bor’ka has a normal loving drawing of his mother on the fridge; Pyotr likes his mother alright and challenge’s Villanelle’s perception of their mother meanness, by stating Villanelle herself used to be mean to him, implying a connection between the two; the husband reveals that Tatiana still cries every night because of the whole thing. All of which becomes the core problem with this episode: Villanelle is an unreliable narrator but we don’t perceive her as such because of our emotional investment in the character. Who is to say Villanelle’s tendencies and behaviour didn’t genuinely scare and tear the family apart and without knowing what to do after her husband died, Tatianna abandoned Oksana in the orphanage, despite genuinely suffering from the decision? Tatianna is a very flawed mother and Oksana is a very troubled child, both these realities are valid and interconnected, in the most nuanced, emotionally challenging and complex episode of the entire show.

Underneath Villanelle’s standpoint, Suzanne Heathcote managed to hide a sensible and honest perception of that family’s complicated past: the heartbreaking reality is that deep down, despite all the layers of pain, trouble, blame, shame and guilt, both characters wished it was different and they could somehow connect, but the truth is that they were, and still are, unable to. Thus, both characters were speaking their truths, however we are not afforded a chance to truly see her mother’s perspective because we are stuck in Villanelle’s world and Villanelle has empathy for no one (Except for her little brother but I don’t want to beat on this dead horse). Despite her manipulative and violent behavior towards her family, from where Villanelle stands - and within her own perspective rightfully so - her mother was simply neglectful, abusive, and worse: saw her as something alien. Thus, having her mother admit her own “darkness” was so important: This darkness I carry belongs to you, therefore I belong to you. Ingenious. Upon revisiting this episode, I truly appreciate it as a showcase of the potential of Suzanne Heathcote’s writting, with beautifully crafted storytelling that seems straightforward at the surface but invites us to dive deeper. Unfortunately, this gem is lost in translation.

The episode was all about how Villanelle made sense of herself and her past, not about what really happened, as the writers claimed they didn’t want to excuse Villanelle’s actions nor erase her psychopathy. It wasn’t about the authoritative writers explaining Villanelle’s past to the audience and deliberately painting Villanelle as a child tortured into becoming a monster because of her upbringing… the problem is that it feels like it was. And when later you add Dasha’s abuse to the mix, the retcon of her psychopathy is irresistible to the audience, but the creators are not naïve and especially as the word “psychopath” seem to have vanished from their vocabulary, when previously it was the selling point of the show; something doesn’t add up. Killing her mother marks a turning point in Villanelle’s character arc, and here things start to get complicated...

Killing her mother sets Villanelle in an identity crisis but what is it exactly?

When Villanelle gets rejected, she kills her mother and sets the house on fire mirroring the orphanage arson. In the train scene, we see Villanelle wearing her mother’s clothes and listening to crocodile rock while crying, smiling, jamming, reminiscing. Despite her efforts to wrap herself in the elements that symbolize the moments she felt like she belonged with that family, she is still alone and there is a lot of pain – fair, psychopaths are not painless. But what that scene represents for Villanelle is an enigma, and I believe not Jodie Comer, nor Suzanne Heathcote, nor anyone, actually knows what this scene is really supposed to mean emotionally for Villanelle.

I want to contrast this scene with another scene in a movie where we watch an actress cycling through many emotions in a long shot as she listens to music: the final 2:30 minute long take in Portrait of a Lady on fire. The scenes parallel each other, and kudos to the unafraid acting of Jodie Comer and Adele Haenel. However, there is a key difference between the two: Celinne Sciamma (screenwriter and director) knew exactly what she was looking for and walked the lead actress Adele Haenel through all the emotions she would be evoking, their succession order and meaning. All the emotions conjured in the scene were carefully crafted in the audience throughout the entire movie, generating a deep connection and understanding of the characters, the story and its symbols, that culminates in an apotheotic cathartic release. That scene was not just a beautiful, emotionally loaded scene: it had intent, it had a clear meaning. And from there on is where Villanelle’s emotional scenes start to break apart.

The display of a person suffering through emotional pain will obviously evoke feelings of compassion, care and empathy in the audience, but this level of immediate reactive connection does not equal an understanding of characters’ emotional reality. It’s important that audiences not only know that the character is in pain but what that pain means, even more so when you are exploring the boundaries of emotion in a character that has a fundamentally different subjective experience than the audience. Given the lack of build up and more extensive exploration of the mother and daughter relationship, it’s not only harder to add the appropriate emotional weight as it is to understand it’s ramifications. Thus, despite lots of tears, Villanelle remains an emotional black box after coming back from Russia.

On the other hand, there is this interesting motif with Villanelle that death brings freedom: once a person is dead, they cease to have a hold on her, allowing her to reinvent herself. For example, when Eve hurt her in the season 2 finale, she kills her to break free from her hold. In her own words: “I’m so much better now my ex is dead”. This motif is again brought up in her conversation with Bertha Kruger in episode 04. As Villanelle tries to reinvent herself after killing her mother and whatever that meant, she learns she was being tricked by ‘The 12’ and that her promotion was a farce, bringing her full circle. She went through these journeys and still didn’t break free: she was still controlled and still rejected, thus her only solution was escape literally and metaphorically.

Her mother rejected her because of her violence, which is precisely the only worth ‘The 12’ see in her. Both of her Nemesis reduce her to the same image: she is a violent kid that kills. Thus, her shifting relationship with killing becomes more interesting when it is framed as a desire for self-affirmation and not as a rectification of her nature as the result of a new found moral compass and compassion, which places Villanelle in the same territory as traditional female assassin characters before her. She is reclaiming her identity, from her past and from her subjugators, hence the motivation to not kill could be seen as a deliberate act of rebellion. However, it is unclear how concrete this motivation is, given that she does indeed keep murdering, and how it interplays with the emotional changes we are shown the character is going through, altogether making her distancing from killing narratively elusive.

Character development couldn’t commit to a narrative, going from nuanced to disorienting

Part of the charm in Killing Eve is what is left unsaid and implied, but nevertheless registers, connects. This relies on the smart use of character expositions and film language to efficiently get the audience on board with the character’s world organically. All previous season’s made good use of monologues and dialogue to flesh out the world and specially characters. In Season 1, Villanelle was explored and developed through excellent dialogues, and in Season 2, when exploring her intimate inner reality, the writers opted to use the AA meetings for a direct exposition via a monologue that tied together previous visual and narrative set up elements.

This type of efficient character exploration doesn’t lend itself well to the nuanced layered exploration the writers set out to do in season 3. And still, they stubbornly committed to it, withholding characters from fleshing out information through dialogue, while overplaying ‘show don’t tell’ trying to convey character’s inner realities with fragmented elements scattered over a disjointed plot, thus relying heavily on the actors to create a semblance of coherence out of the cacophony. I truly believe this choice was extremely detrimental to the season, since it created unnecessary challenges for the main goal which was character exploration. The result is an unsettling gap between the writers’ vision of the characters and their arcs, and what we, the audience, experience.

I want to take a moment to explore examples of storytelling choices that I found confusing in developing Villanelle past episode 05, by taking a look on her 3 murders after she comes back from Russia.

In the Romania kill, we see Villanelle sitting on the bed halfhearted, downgraded into taking this job after her promotion debacle. The title card links us back to the scene in the beginning of the episode when she realizes she was conned. This is bullshit, this job is bullshit, and yet she has to do it. All elements are underlying the conflict in her search for autonomy, but then the song in the background evokes sentimentalism, underlying Villanelle’s growing feelings, subtly implying she feels bad about the act of killing. The scene composition sends mixed signals. Then it cuts to Villanelle ready for the kill with the upbeat recap intro music playing (????), she can’t focus, gets stabbed and cut to an angry tear-eyed Villanelle stitching up her own wound in the bathroom floor, fleshing out how she felt used and that she wants out. Then for a moment, the scene gets more intimate and she says - or even confesses? - she doesn’t want to do it anymore. We look down to a defeated and vulnerable Villanelle underlying the characters impotency or is it a moral struggle? The entire sequence purposely avoids committing to whether she failed because she didn’t want kill, or because she couldn’t kill. These two conflicts have completely different implications in interpreting and understanding the character development, but we remain in the limbo, confused as to what it could be.

To make matters worse, both these motivations: quitting ‘The 12’ and stopping killing, will be flipped when Villanelle pro-actively asks for a job and decidedly kills Dasha (who survived out of plot contrivances luck ). The scene with Helene is also interesting. When Villanelle meets Helene there is a conflict around identity and belonging. A particularly childlike Villanelle is again falling into tears as Helene breaks into her personal space with an embrace. Villanelle gives in to the embrace then pulls away at the mention of the word monster. That is not the identity Villanelle wants, nevertheless it feels good to be accepted. Then Villanelle asks an exasperated Helene for another job, not before being reminded she is a child, again powerless.

“Look what you made me do” playing in the background.The song alludes to the power domination she is under and her motivation to break free, but the entire scene alludes to her conflict over her self-perception and belonging with Helene as a mother figure. I’m nor sure I follow what the character wants, I’m hanging on a spiderweb on the wall, Villanelle is crying, and can we please stop torturing this character into feelings for five minutes? Who is this reformed character? Jokes aside, there is one message that emerges, which is Villanelle doesn’t want to be a “monster” (violent killer, or more subtly violent in general) but she is forced to do it. This scene does succeed in softening Villanelle by emphasizing this new narrative leap following her seeming new found conscience: that Villanelle was made into a violent woman, but she is not naturally one. Her brutality is not transgressively hers anymore, it is a burden imposed onto her, which again places Villanelle’s character back into the comfort of the place designated to violent female characters: sad broken woman went murderous. Which stands in sharp contrast with Villanelle characterization so far, and what made her character iconic in it’s own right. The only way to make this narrative work is assuming killing her mother erased her psychopathy and gave her the whole bag of feelings and empathy. But if episode 05 fails to sell that, then the following episodes feels like tumbling down a rocky narrative slope. But the seed still lingers on my mind after reading paratext from the creators and cast: if you’re not trying to retcon Villanelle, then what does this all mean?

Rhian’s murder is a pivotal moment in Villanelle’s arc that fell into obscurity by jarring storytelling. Here the narrative seems to finally address the elephant in the room: when push comes to shove, can she control her violent impulses, which, no matter if inherited or cultivated, became a core part of herself? The ballroom tea dance effectively distances Villanelle from killing, but Villanelle and Rhian’s exchange show things aren’t so simple. More overtly so, Rhian and Villanelle subway brawl is all about giving Villanelle a chance to fully articulate the conflict around her subjugation to ‘The 12’ and her self-agency. Villanelle beats up Rhian, which could symbolically represent her refusal to be an obeying “sheep”; but, despite trying to get a grip of herself, her nature takes over and she kills, which could represent the uncontrollability of her impulse. Thus, the interaction between these two scenes, ballroom dance and Rhian’s kill create a conflict surrounding Villanelle’s nature, self-control and capability to change that goes beyond the central conflict of each scene alone. Interesting, better explore it late than never, right?

The next scene seems to give us the resolution of this conflict, as Villanelle exits the subway, marching forwards, defiantly looking at us while we hear “Nothing matters if you bury it deep” in the background. It sends a message that Villanelle ultimately embraced her nature, and perhaps herself, and by doing so symbolically broke free from the oppression, emerging victorious. One could say she found her mojo back by killing on her terms. However, this never has any effects on the character, Villanelle is still as conflicted about her self-identity and still expresses her desire stop killing when we meet her again in the final scene as if her march after killing Rhian never happened. so what was the writers trying to say with the Ryan’s kill sequence when, despite disconnecting and contradicting the previous and following scenes with Eve, it seems to have no effect on Villanelle herself? What narrative are the writers committing to?

Villanelle’s character arc: the faithful translation of a uncommitted vision

Villanelle’s character arc, not that it is her privilege, gets muddled by deliberate ambiguity, character isolation, confusing motivations, and overall disconnected narrative as the writers refuse to commit to a vision. Thus, set-ups, pay-offs, conflicts and cause-effect are muddled, devoiding the character development of tangible meaning or aim – nuanced or otherwise. Despite it all sort of working moment-to-moment, it’s hard to keep up with what is being established overall, the ever shifting and clashing elements making it impossible to crack these characters and their journeys. In threading the fine line between the said and the unsaid, Season 3 had its characters bottling up so much that we are alienated from them. Simply saying “something changed inside her, and she is facing lots of things” doesn’t mean anything. Having the character state that she doesn’t want to kill (be it in general or for ‘The 12′) only to have have your character still actively killing both for ‘The 12′ and for personal reasons and ignoring the conflict it creates, shows the character’s motivations don’t mean anything. Villanelle was in search for an authentic self-identity but in the end who is she? What was this journey all about? Honestly, fixing Villanelle to allow a romance no one really knows.

So my overall impression is that Villanelle’s character wasn’t lost in translation because there wasn’t any coherent vision behind it, but a succession of floating undecided moods and motivations tied together by powerful performances that leaves you feeling like Villanelle was redeemed. Thus, the audience - and arguably the cast and creators - are left relentlessly rationalizing Villanelle so the character doesn’t fall apart. Some see Villanelle truly in love, some see her as obsessing, some see her as emotionless, some see her as a pastiche, some see her as blossoming into her true self, some see her as two different characters (Oksana/Villanelle), some just think she cries a lot, some think she is remorseful, some think she isn’t, some believe she is a psychopath, some think she matured, some think she was never a psychopath and some think she is outright cured. No one fully grasped what is happening with Villanelle, not because her character is complex beyond comprehension but because her character remained conveniently inaccessible. Ultimately, Villanelle’s character growth is a mystery the show teased at but did not commit to crack.

#killing eve#killingeve#killing eve review#killing eve analysis#killing eve season 3#killing eve s3#killingeveperspectives#ke#ke s3#villanelle#villanelle analysis#killing eve retcon#villanelle retcon

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAMG’s Shameless Self-Promotion

(fanfic edition)

Thunderstruck (Underfell Papyrus/Reader)

Story written in Edge’s POV focused on character development and that sweet sweet unreliable narrator trope. Stuck in the post-Pacifist Undertale world, Edge has to adjust to new life. It doesn’t always go well but, thankfully, you’re there to help him.

Dumb (Swapfell Papyrus/Reader)

Story written in Papyrus’ POV. He just moved out to live on his own, away from his overprotective and overburdening brother... and he needs a fake friend. Fast. You, as his neighbor, are his first and only pick for that role. He just hopes he won’t mess up like he always does.

Brother From Another World (Undertale Sans & Swapfell Papyrus)

Story written in Sans’ POV. The lazy skeleton lives on the Surface for a while now and seems to have it all. One evening in the Lab he hoped he left behind brings him a familiar looking but young skeleton and Sans decides to put his Big Bro pants back on.

A Second Chance (Spicyhoney)

Story written in Carrot’s POV. All the monsters in his world are slowly moving to live on the Surface. Somehow, being a good healer, he ends up taking care of an amnesiac skeleton from the different universe. It would be much easier if said skeleton wasn’t so scary and didn’t try to kill him the last time they met.

Remember to mind the tags and warnings!

💀 💀 💀

#my writing#my writing masterpost#thunderstruck fanfiction#dumb fanfiction#brother from another world#a second chance fic#underfell papyrus x reader#swapfell papyrus x reader#big bro sans#spicyhoney#spicycarrot#papcest#papship#skeleship#i know i have a theme#shush#i love taking the scarred poor and traumatized skeletons#only to put them in better environment#and let them recover and grow#i'm a sucker for this#let them be happy ffs#with angst along the way#because there needs to be balance

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stormcrow Reread

I’m rereading Stormcrow for my challenge day playing with POV fic, so I might as well post some notes. Looking for interesting Wolfe/Santi details and playing with how to make oddities fit with canon. Long post.

I just love Wolfe’s voice. That is all.

Wolfe says he became “a full Scholar” at 15. I am taking this as the age he graduated. The deleted Ink and Bone scene that Caine also has posted on Wattpad has Wolfe starting as a Postulant at 13. I’m inclined just to say that story isn’t canon, but if you want to make it all fit, you could say he graduated at 14, did something else for a year (apprenticeship? internship? that mission he and the Artifex talk about in Smoke and Iron?), then started as a Scholar at 15. Alternative option: that deleted scene happened very close to his 14th birthday, Postulant program lasted a full year, he graduated close enough to his 15th birthday that he was 15 when he started as a Scholar (after summer break? if they have summer break?). If we really, really want to make too much of all this, we can argue that this gives us a semi-canon summer birthday for Wolfe.

By 18, he’s published 10 “highly valued technical works.” I see “publish or perish” is in full force in Alexandria. I would really, really like to know more about his publications. My guess is that these are 10 relatively short papers, or possibly papers he collaborated with more senior Scholars on, and he’s exaggerating his own importance a bit.

Wolfe says he has an entire High Garda company. Does he? In Paper and Fire, Jess seems to think taking a whole company anywhere is rare. The Artifex is important enough to get a whole company to guard him, but the pack only got a half century for Oxford. Possibilities: A, Jess is wrong; taking a whole company isn’t that unusual, and taking as few troops as they did to Oxford was clear evidence that the Artifex was trying to kill them all. B, Wolfe is wrong; he doesn’t actually have a whole company, just a couple squads, but he doesn’t know enough about the High Garda to realize that. C, Wolfe is lying; this is the Scholar equivalent of a big fish story and he’s saying he got to take a whole company to make himself look good. D, There is, in fact, a full company there, and Wolfe is a dumbass for not realizing that being sent with a full company means Moscow is ridiculously dangerous. E. There is a full company, but they’re not just there for Wolfe; most of them are going to be fighting Burners while Wolfe deals with the Serapeum. I favor some combination of C, D, and E.

The High Garda get winter uniform coats. “Sand-colored,” not the usual black. Wolfe had a robe the same color during the training exercise in Paper and Fire, so I’m guessing this is the Library equivalent of desert camouflage, probably worn in Russia because it would stand out less than the usual black against snow. Another sign that the troops are expecting a fight, which Wolfe misses.

Captains’ collars have Horus eyes. I don’t remember this detail from the books. Also, Library sign on both shoulders.

There is no description of what Wolfe is wearing, beyond the usual Scholar’s robe, boots, and a scarf. That is not warm enough for weather cold enough to freeze lungs. I am headcanoning him a very luxurious black fur-lined cloak to go over that robe while he’s outside, and I refuse to be convinced otherwise.

Wolfe and Santi flirt through hurt/comfort scenes; is it any wonder why I like these two so much?

Wolfe doesn’t recognize Santi here. Santi said in Ink and Bone they met as students. I’ve been over this one already.

Such mixed emotions here for Santi. He’s watching the arrogant but sexy Scholar make a fool of himself, and he has got to be torn between laughing his ass off and hugging the pretty and hurt man. It is a testament to his self control that he manages to be all calm and comforting.

“A tidal pull, a compass pointing north. As if I was seeing a familiar shore after a long, long journey.” Wolfe gets so adorably poetic when he’s falling head over heels in love. But also, this “familiar shore” line, and then Santi’s “I know” both times Wolfe introduces himself totally supports my theory that Santi remembers Wolfe from school even though Wolfe doesn’t quite consciously remember him.

So Santi is a lieutenant here. One rank below captain, which seems to be second only to High Commander. (One day I will try to sort out High Garda ranks. Not today.) He’s around 19, and has been in the High Garda for about 3 years. That’s a rather stunning rise through the ranks. I’m kind of leaning toward headcanoning that he’s actually 2nd lieutenant, not 1st (maybe even lower rank - Wolfe is not a reliable narrator), and he gets put in charge of Wolfe in the Serapeum because all higher-ranking officers are busy with the Burners outside.

The difference here in Wolfe’s reaction to unsolicited touch from Santi and from this other soldier, omg.

Santi wiping blood off Wolfe’s face. Yes, good, very nice image there.

I would say that only for Wolfe and Santi is calling someone an “arrogant ass” a good way to flirt, but if I remember right, Khalila calls Dario the same thing.

I wish I had a better idea of the relationship between Santi and Captain Nghiem. He’s affected by her death, but not devastated, so it doesn’t seem like they were close. I feel like they might not have gotten along well, but I really don’t see any support for that in the text. Or maybe Santi was only recently transferred into this company and didn’t know her well.

Santi: “From now on, you will not argue one single order I give you. Is that agreed?” Wolfe *glad no one can see his boner under robes and winter gear* “Yes.” You can practically hear the unsaid “sir” there. And then he doesn’t like Santi calling him “sir”. This is where I get Wolfe’s submissive side from. Right here.

Wolfe refers to Santi as “captain” here. Editing error? Unreliable narrator? Santi got a field promotion? Wolfe is telling this story after Santi has made captain and just keeps slipping into using his current rank?

Wolfe estimates that Santi is 18 or 19. I’m going with 19, which would have him graduating at the more normal age of 16. I’d be willing to push his age as high as 20 or 21, especially if we’re trying to make that deleted scene fit with canon as well and having Wolfe starting as a postulant at 13/14. A 2-3-year age gap doesn’t seem unreasonable when Wolfe graduated so young.

Only one member of an entire Serapeum staff in a major city trained in Alexandria. That, I think, says something about how exclusive the program all our characters graduated from is. I really want to know what other paths into Library careers are available. Local training programs for Serapeum staff? Some kind of mass recruiting for High Garda cannon fodder?

The Serapeum here seems to be a former palace. We have other Serapeums in the series that used to be cathedrals. The Library is obviously in the habit of acquiring pretty buildings.

But even though he was just all submissive with Santi outside, here’s Wolfe saying he put Santi to work like it’s a perfectly natural thing to order him around. Yup, definitely switches, these two.

The Librarian here has a silver collar. Interesting.

Oh, Wolfe, you think these people are just getting prison sentences. You have no fucking clue yet what the Library does with people who break is rules.

Also, secular court. As opposed to Library court? Or some other kind of court that’s a thing in Russia? Hmm.

Even allowing for Wolfe’s exaggerations, visiting Scholars get spoiled rotten.

The more emotional Wolfe gets, the heavier he gets on the figurative language.

Santi was totally hoping to get into Wolfe’s pants when he went into his room. I get the feeling he wasn’t expecting Wolfe to be as inexperienced as Wolfe obviously is. He doesn’t seem to think anything of serving him vodka on an empty stomach, and apologizes when it hits Wolfe harder than expected. He’s sympathetic toward Wolfe’s shock at the events that just happened, even as he keeps trying to redirect the conversation toward flirting. Then he expresses his interest in Wolfe and leaves, putting the ball in Wolfe’s court. If Wolfe had asked him to stay, he would have, but he’s not going to push Wolfe to move faster than he’s comfortable with, and he’s going to get out of there before they both get too drunk.

Wolfe, meanwhile, is all adorably clueless. He doesn’t even know how to respond when Santi offers him a drink. He needs a shot of liquid courage to ask Santi out, and is an idiot about asking him out. He’s constantly second guessing himself. He cannot imagine that Santi would want to stay if he asked, not that he even has a clue how to ask. He needs a fucking glass of emotional support vodka after a rather tame round of flirting.

Just compare language. Santi is all playful and charming: “I think you’ll bring a great deal of storms with you from now on. You have that look.” “I’d rather you be awake to admire how well I do my job.” Wolfe is painfully awkward: “If I should ask for you to be assigned to me from now on, Lieutenant... would that be acceptable to you?”

Little details that show Wolfe is used to hot climates: thinking of “warm, silken sheets” when imagining sex (not thick piles of blankets), too afraid of the cold to take a bath.

Wolfe: He’s not here. He didn’t text me. He must be avoiding me!!! Oh, wait, right, he has a job. But wait, that doesn’t fully explain things. IS HE OK?!?! (in his defense, he’s actually right to worry)

Library staff has quarters in the Serapeum.

The troops being quartered away from Wolfe is another clue that protecting him isn’t the only reason they’re there. That, or the Artifex and/or Archivist is already trying to kill Wolfe and has arranged for him to be isolated. (This would have to be after the mission Wolfe mentions in Smoke and Iron, which seems to be where things went sour between him and the Artifex.)

Santi has a ��battered Library-issue Codex”. Possible clue to social class? His family didn’t give him a fancier one like Jess’s or Dario’s parents gave them, or like Keria’s Scholar friend (and how did that happen since Obscurists are stuck in the tower - not a particularly close friend, presumably, or just a non-canon detail there) gave Wolfe in the deleted scene. Maybe they couldn’t afford it. Or clue to personality? He’s a soldier and doesn’t want a fancy book.

“I aggressively didn’t care.” I just love this line. This is Wolfe’s attitude toward so many things, neatly summed up.

“It’s a dramatic garment, best used for effect.” This is also just so Wolfe. He has a talent for drama, and knows how to use that Scholar’s robe to its fullest potential.

Wolfe “didn’t even know why” he couldn’t leave Santi behind. You fucking dumbass, you have a giant fucking crush on him.

Wolfe understandably wants nothing to do with his mom, but he will interact with her for Santi. He will not, however, be nice about it. He thinks this means he will owe his mother a debt. I have to wonder what kind of favor she would ask from him in return.

“She no doubt treasured the pen far more than she had me.” Just stab me in the heart why don’t you? Fuck you, Keria.

So Santi’s Codex has been there two hours. What was he doing between leaving Wolfe’s room and going to bed?

The Library is keeping flammable books in a room made of amber. So here’s a clue that the Library doesn’t care about the books as much as they say they do.

“Russian was not my strongest language.” But he still knows it well enough to come up with the code under pressure. Some evidence that Wolfe is good with languages.

Are bloodstained books still readable? Hmm.

Nothing makes Wolfe angry like injured Santi.

There is nothing better than Wolfe scolding injured Santi while taking care of him.

I also love the completely unconcerned response Wolfe has to learning he and Santi have different religions. It’s both indicative of this world’s greater levels of religious tolerance than the real world, and a very polytheist response to this sort of thing. You have a different god than me? So what, there’s tons of them! Just one more name to add to the list when swearing.

Wolfe instinctively tries to touch Santi. Latent Obscurist talent driving him to subconsciously attempt healing? Or just the need to comfort the pretty and injured man?

Ugh. Timeline. Wolfe went looking for Santi at dawn, and things seemed to have happened fairly quickly. 16 hours later should not be daylight. Let’s chalk this up to Wolfe being unreliable and not paying attention to times.

So we have blood transfusions and IV nutrition here, to add to the list of available medical technology.

Wolfe, you absolutely suck at self care. Also, you have fallen so fucking hard for Santi, omg. Sitting at his bedside and watching him breathe.

Wolfe really does not like being called sir. Is my kinky brain reading waaaay too much into this? Yes.

Santi kept Wolfe’s location a secret. Just how many fancy guest rooms does this Serapeum have? Eh, former palace, probably a lot.

Wolfe still sucks at expressing feelings. “I think you’ll save me in the long run.” Oh for fuck’s sake, just tell him you are madly in love and already imagining spending the rest of your life with him.

“fragile and sharp and painful and beautiful” This is what emotions are for Wolfe.

And Santi is so fucking sweet. He knows exactly what Wolfe is saying, and he lets him say it in his own terms.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Albert’s Magical Library #7

Witchcraft Today - Gerald Gardener (1954)

Odd, messy, maddening history of witchcraft and its revival - with a very unreliable narrator. Completionists only.

Spurred on by @judd051 comment that Valiente's account of the rebirth of witchcraft isn't necessarily accurate, I made this my next read. Gardener isn't as fluid a writer - it reads like a first draft

History is the art of interpretation. Solid facts are few and far between. Good history consists of taking good evidence and explaining how it forms a narrative. Bad history is Witchcraft Today: a jumble of un-sourced history, pseudohistory, surmises, guesses and facts. In history class, you learn how to analyse sources: who wrote this? Why? Are they reliable? Are they biased? Were they writing at the time? What experience or expertise did they have?

This is a truly maddening book, which tells you far more about ideas current at the time and ideas Gardener wants you to believe than actual history.

Gardener is an unreliable source. He takes as fact many sources which have since been disproven - Margaret Murray, and some Da Vinci Code level ideas about the Templars. He is very credulous - at no point in this book do we see him reflecting on reliability. For all that Valiente's conclusions could have been wrong - at least we see her, within her own book, asking questions like “...but what evidence is there for this?”, and willing to debunk ideas held by those around her.

This book presents Gardener's key belief - that the witch trials were distorted views of a surviving ancient Pagan faith, which exists in an unbroken lineage to the present day, which he was initiated into. I've mellowed a lot on this viewpoint since reading more primary texts. Young Albert thought it was bunk. Older Albert thinks there are grains of truth in all three, but these grains have been taken out of all proportion. I think it's plausible that non-Christian nature faiths and folk witchcraft traditions existed in Tudor times, although most people persecuted as witches were not members of that faith, nor was it one unified Religion as we would understand it today. I think the survival of witch customs in local history and families is undeniable, although I think claims to long lineages are unlikely. I think Gardener probably was initiated into a cult involving others, from which he built his own traditions.

How you feel about the book will rely heavily on how you feel about these ideas. Still, aside from that, he also believes in some right shit. He still believes in one, universal religion which unites the Greeks and the English and pretty much everyone. He believes that vodou looks so similar to European Witchcraft because it is wholly based on it, rather than the more sensible view that folk faiths and trad crafts and spirit traditions have organically grown up along similar lines (he shows limited understanding of how African continental traditions were the root of African diaspora religions, and limited enthusiasm for the idea that Black people have created their own religions rather than simply copying from the whites). He thinks legends of fairies and elves come from the real existence of a race of pygmies living in the Isle of Man.

All these horsecrap ideas are presented as fact, and they are certainly of interest to Wiccans and scholar/librarian/research types as they reveal the ideas and influences on Gardener as he developed his Craft, ideas which continue to influence Pagan/Occult traditions today. And there is such a grab-bag of ideas that doubtless, some of it will run near to the craft you do - there's an especially strong focus on witch trials and folkloric witchcraft throughout, which trad types will like. But you can't mistake any of this for serious history.

Above all: whenever Gardener has a question about contemporary witchcraft, he says “I asked my witch friends and they told me...”. Is this concrete evidence that yes, Gardener was initiated into an unbroken lineage of witches? Or is it self-promotion, invention to bolster up his claims? Are “my friends say...” really another way of him saying “I think”? How could we ever tell? When Valiente writes about Crowley's influence on the original rites, she writes that she thinks Gardener copied bits of it. That seems plausible. When Gardener writes about out, he assumes the position of a historian asking “now why are these things so similar...? How interesting!", and comes to the conclusion that Crowley was initiated into the witch cult and was inspired by it. I don't trust him one jot.

Despite my misgivings, this book is its best when Gardener is talking about the present day. The last four chapters are pretty riveting. “My friends tell me that...” WHO. WHO ARE THEY GERALD. Still, here are all these snippets about what the New Forest Coven was supposedly doing, and they are all strange enough to have a ring of truth. They're just too weird and incomplete to be made up. I want to sit him down and demand more details. There's a lovely description of where the legend of witches turning into animals comes from:

I have asked witches what is the origin of the story of their turning into animals. To them it is only a joke; but they have memories of confused stories that at times they would play sorts of games, much as children do. If they were going across country, for instance, they would say: 'Let us go as hares,' and try to imitate hares running; or as goats, butting each other, or as deer; and there is a suggestion that in the burning time they were told: 'If you see anyone behaving as an animal, they have become an animal. If questioned, say you saw no man, but only a hare, or a goat, etc., because if you simply lied and said you saw no one they might know you lied, but if you said you saw some goats, and believed it, you had the resemblance of truth, even under torture.'

He also recounts some ideas about reincarnation, and specifically the need to placate the gods so you will be reincarnated back into your tribe, that I've genuinely never encountered before. I remember “Some Wiccans believe in reincarnation” from geocities, but this is the first time I've seen specific ideas about reincarnation written down, and they are very peculiar and unique. I appreciated reading his from-the-horses-mouth explanation of the gender polarity in Wicca - original Wicca was imagined as exclusively covens of male-female romantic couples, or two singles, as romance would inevitably blossom between them. The implication is both that a romantic/sexual connection is crucial for magic, and that cannot exist between two men or women.

This is such a love-to-hate book. I'm glad to have read it, and I will definitely revisit the last couple of chapters for ideas in future. All the same - I fundamentally don't trust a word that comes out of his mouth. So much of it is so clearly inaccurate or lies that it's then hard to evaluate any of it as true. It's infuriating, because Gardener clearly has a lot of information and I wish I knew what in here I could trust.

Fascinating, but for completionists only.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you like how Armin has been described on his Attack on Titan wikia page?

Altogether,I think it’s a very standard, ok surface description. It’s great for looking upsomething you’re unsure about, but I don’t think you get the depth of thecharacters from the wiki in general. And it might just be me, but I get a veryanime-leaning vibe from the site, so I don’t consult it very often. There is a point I want to make about Armin being an unreliable narrator, andI’m going to use this ask as my opportunity to touch upon it, but first, I’llnitpick on some other stuff I found, since you ask:

“Althoughhe appears to be the physically weakest of the 104th Taning Corps,his intelligence and strategic genius makes him an invaluable asset, especiallywhen paired with Hange Zoë’s mind,” the wiki says in the introduction. Well, Ihave two issues with this: the first is the claim that Armin appears to be theweakest of the 104th. This is why I say the wiki feels eerilyanime-favoring; in the anime, things are sometimes simplified, and we get theshortcut, gimmicky version of the manga. Its logic goes like this: “Armin isweak, his issue is inferiority due to that weakness, and he didn’t graduate topten. Conclusion: he is the weakest of the class.” But this isn’t necessarilytrue; top ten is the icing on the cake. Did they not see all the unnamed cadetson the training grounds? In the smartpass interview, when asked if he couldtake down Historia in combat, Armin didn’t even dignify the question with ananswer, he merely asked if he really looked that weak. And even if he came in absolutelast place – out of what, fifty cadets – it could be due to more than strength:it could be stamina, stealth, etc. Drawing such under-developed conclusions as“he is the weakest” is what I dislike with the anime, and the false narrativethat it pushes onto the fans until they believe it. They simplify thecharacters, and I think in Armin’s case, it’s the reason why so many walk awaythinking he is weak and useless, when in reality that description hardly fitshim.

Secondly,the Hanji comment, to me, seemed absolutely unnecessary and out of place. Arminis an invaluable asset, period. He can’t be more invaluable by addingan extra component. Invaluable is invaluable. If they wanted to say that heworks well with the new commander, that point could find a much more naturalplace somewhere else in the text. Adding this to the very introduction ofArmin’s page, tells me yet again, that the fanbase has become misguided in howthey view Armin: he’s not a great add-on, he’s his own asset. He doesn’t giveother character an extra edge, he’s his own force to be reckoned with. All ofArmin biggest moments, greatest plans, most spectacular wins, were all productsof his own mind alone! Yet again, we’ve been fooled by the simplicity that theanime promotes: we assume that, as clever characters, Armin and Hanji are boundto be a dream team – because all smarties get along, right? To some extent,they do produce results together, but they aren’t very compatible outsidespitballing; Hanji spins on Armin’s input and leaves him in the dust becausethey prefer to run their own show, not even considering what part of it comesfrom Armin’s own skill to keep up. That’s their personality, and I’m not tryingto fault them for it, but why mention how well Armin works with Hanji, when thelatter doesn’t even recognize Armin’s skill for their own (as further shown inShiganshina, when Hanji did not so much as mention there being a dilemma worthconsidering – nor has expressed any sort of sentiment towards Armin’s contributionto the group ever since he was saved by Levi, if ever). Armin’s short period ofthrowing ball with Hanji is so insignificant to his person (and personality),that I feel like most anything else could be a better way of closing thatopening paragraph on him.

Anotherone: “Armin is rather short for his age,” the wiki page says. While shorterthan most of the other prominent teen boys of the story, Armin beingparticularly short is not something that has ever been given any significancein canon. I’m not saying he’s not short, but this wording makes it sound likeit’s a very prominent part of his appearance, which it isn’t. In your teens,you’re in constant growth, and hormones kicking in later than others’, isnatural. I looked up average height for 15 year old males (present time), andwhile he’s shorter than the average of 170 cm, he fit the average of a 14 yearold to the decimal. For one, it’s not unusual to be a late bloomer, and also, Ihave a theory that he might have been 14 and a half throughout the Trost arc: untilthere is explicit canon proof that Armin is the oldest of the trio (and bornthe year before Eren), he could very well have been turning 15 throughoutmost of the story so far; it’s never explicitly said that you had to be 12 to join bootcamp; as with many schools, perhaps you only needed to turn 12that year, meaning he could have been 11, going on 12 the year of enrollment. Thus,he could be fourteen and a half (and only half a year away from being theaverage height for his age) back in Trost. What’s more: humans have continuouslybecome taller on average. A hundred years ago, the average was considerablyshorter, as the average in the SNK universe could be. Regardless: while Armincould still be shorter than average, there’s absolutely a difference between“below average” and “rather short”. Again, this is an anime-worthygeneralization that skews his character to less keen consumers.

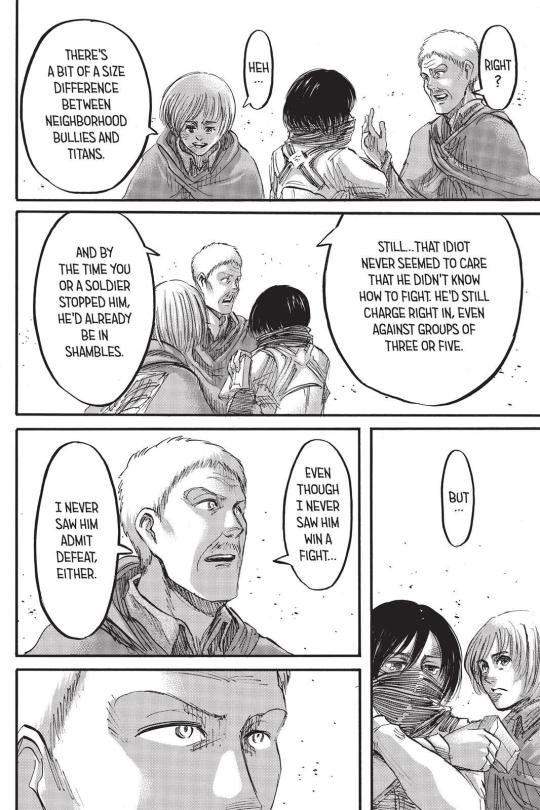

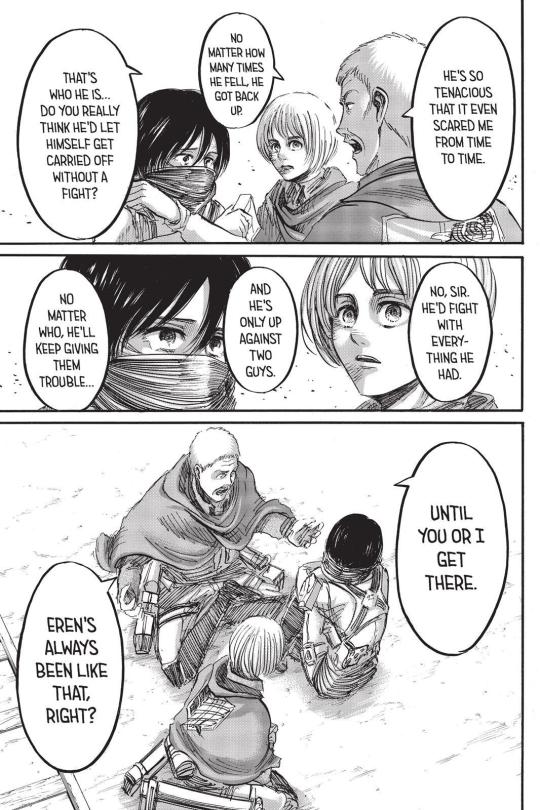

Now, on towhat I’m really here to talk about: “too timid to defend himself, Armin wouldoften need to rely on his friends (Eren Yeager and Mikasa Ackerman) to protecthim from local bullies.” We all know this to be true, right? Why? Because Armintells us so, repeatedly, through his own narrative. But what he feeds us – asboth narrator of the story, and as a main character with frequent innermonologs – is his own skewed perception of his childhood. If we were asked todescribe the trio’s dynamic back in Shiganshina, most of us would be inclinedto say something along the lines of “Eren and Armin would talk about theoutside world while Mikasa listened, and whenever Armin got picked on, his twofriends would have to come to his rescue because he was too weak to defendhimself.” But this isn’t entirely true, as rather: it’s an image with weightwrongfully placed on Armin’s uselessness – a uselessness he’s put on himself,and that nobody but him actually experiences. Let’s look at what Armin says vs.what the manga shows us: Armin portrays himself as a hopeless coward faced with his bullies. But in thevery first encounter we see him have with them, he talks back and stands up forhimself like a badass. In Eren’s flashback in chapter 83, it’s confirmed thatArmin never runs away from those bullies, and probably stands his ground thesame way he did in the first chapter. While Eren and Mikasa would beat his bulliesfor him, that’s not the only way to win or be strong – as Eren would agree,deeply impacted by Armin’s resolve as he was. Armin talks about how he was tooweak to fight for himself, and he selects the images of him crying on theground to emphasis this – so we’re fooled to see the same thing he sees – but that’san image that’s stripped of the positive aspects of him, because it’s hisimages. What we don’t see from his perspective, but that we see in the reallife encounter, as well as Eren’s flashback, is a strong-willed boy with witsto make up for lack of muscle. Does it not take just as much strength to standyour ground (and not hit back), as it takes to wrestle someone to the ground?

Somethingthat further drives home the point that Armin shapes the past to fit hisnarrative, is how he gives us the impression that the fist fights the trio gotinto were all for the sake of him. But that actually isn’t the case! Back inchapter 45, we get a description of the same past, through the eyes of an outsider,and I think you’ll find that it’s rather different from Armin’s way ofportraying it: