#therumpus

Text

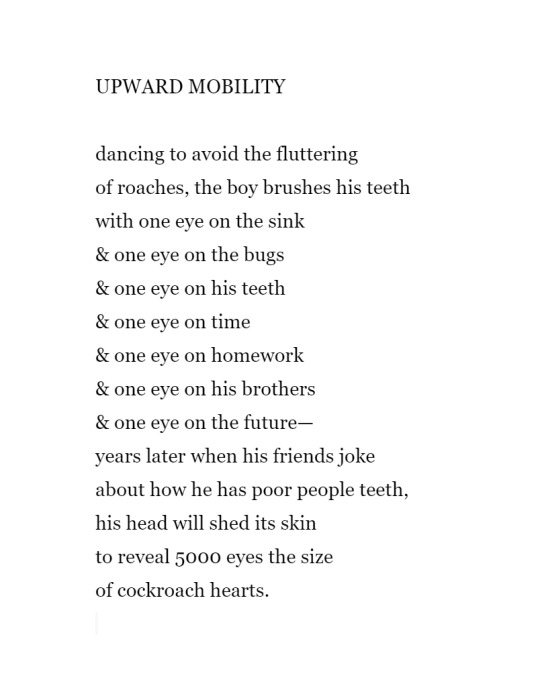

José Olivarez, Promises of Gold; "Upward Mobility"

[Text ID: dancing to avoid the fluttering / of roaches, the boy brushes his teeth / with one eye on the sink / & one eye on the bugs / & one eye on his teeth / & one eye on time / & one eye on homework / & one eye on his brothers / & one eye on the future— / years later when his friends joke / about how he has poor people teeth, / his head will shed its skin / to reveal 5000 eyes the size / of cockroach hearts.]

An excerpt from The Rumpus Poetry Book Club‘s February selection,

Promises of Gold by José Olivarez

forthcoming from Henry Holt and Co. on February 7, 2023.

Subscribe by January 15 to the Poetry Book Club to receive this title and an invitation to an exclusive conversation with the author via Crowdcast.

#José Olivarez#Promises of Gold#Promesas de Oro#Upward Mobility#poetry#therumpus#indielit#indiemagazine#rumpuspoetrybookclub#amreading#joseolivarez#promisesofgold#Henry Holt and Company#excerpt#literature#love#gender#capitalism#religion#migration#words#quotes#translation

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE ORDINARY MIRACULOUS

Dear Sugar,

I printed out your column, “The Future Has An Ancient Heart,” and put it up on my wall so I can read it often. Many aspects of that column move me, but I think most of all, it’s this idea that (as you wrote) we “cannot possibly know what it is we’ve yet to make manifest in our lives.” The general mystery of becoming seems like a key idea in many of your columns. It’s made me want to know more. Will you give us a specific example of how something like this has played out in your life, Sugar?

Thank you.

Big Fan

Dear Big Fan,

The summer I was 18 I was driving down a country road with my mother. This was in the rural county where I grew up and all of the roads were country, the houses spread out over miles, hardly any of them in sight of a neighbor. Driving meant going past an endless stream of trees and fields and wildflowers. On this particular afternoon, my mother and I came upon a yard sale at a big house where a very old woman lived alone, her husband dead, her kids grown and gone.

“Let’s look and see what she has,” my mother said as we passed, so I turned the car around and pulled into the old woman’s driveway and the two of us got out.

We were the only people there. Even the old woman whose sale it was didn’t come out of the house, only waving to us from a window. It was August, the last stretch of time that I would I live with my mother. I’d completed my first year of college by then and I’d returned home for the summer because I’d gotten a job in a nearby town. In a few weeks I’d go back to college and I’d never again live in the place I called home, though I didn’t know that then.

There was nothing much of interest at the yard sale, I saw, as I made my way among the junk—old cooking pots and worn-out board games; incomplete sets of dishes in faded, unfashionable colors and appalling polyester pants—but as I turned away, just before I was about to suggest that we should go, something caught my eye.

It was a red velvet dress trimmed with white lace, fit for a toddler.

“Look at this,” I said and held it up to my mother, who said oh isn’t that the sweetest thing and I agreed and then set the dress back down.

In a month I’d be 19. In a year I’d be married. In three years I’d be standing in a meadow not far from that old woman’s yard holding the ashes of my mother’s body in my palms. I was pretty certain at that moment that I would never be a mother myself. Children were cute, but ultimately annoying, I thought then. I wanted more out of life.

And yet, ridiculously, inexplicably, on that day the month before I turned 19, as my mother and I poked among the detritus of someone else’s life, I kept returning to that red velvet dress fit for a toddler. I don’t know why. I cannot explain it even still except to say something about it called powerfully to me. I wanted that dress. I tried to talk myself out of wanting it as I smoothed my hands over the velvet. There was a small square of masking tape near its collar that said $1.

“You want that dress?” my mother asked nonchalantly, glancing up from her own perusals.

“Why would I?” I snapped, perturbed with myself more than her.

“For someday,” said my mother.

“But I’m not even going to have kids,” I argued.

“You can put it in a box,” she replied. “Then you’ll have it, no matter what you do.”

“I don’t have a dollar,” I said with finality.

“I do,” my mother said and reached for the dress.

I put it in a box, in a cedar chest that belonged to my mother. I dragged it with me all the way along the scorching trail of my twenties and into my thirties. I had two abortions and then I had two babies. The red dress was a secret only known by me, buried for years among my mother’s best things. When I finally unearthed it and held it again it was like being punched in the face and kissed at the same time, like the volume was being turned way up and also way down. The two things that were true about its existence had an opposite effect and were yet the same single fact:

My mother bought a dress for the granddaughter she’ll never know.

My mother bought a dress for the granddaughter she’ll never know.

How beautiful. How ugly.

How little. How big.

How painful. How sweet.

It’s almost never until later that we can draw a line between this and that. There was no force at work other than my own desire that compelled me to want that dress. It’s meaning was made only by my mother’s death and my daughter’s birth. And then it meant a lot. The red dress was the material evidence of my loss, but also of the way my mother’s love had carried me forth beyond her, her life extending years into my own in ways I never could have imagined. It was a becoming that I would not have dreamed was mine the moment that red dress caught my eye.

I don’t think my daughter connects me to my mother any more than my son does. My mother lives as brightly in my boy child as she does in my girl. But seeing my daughter in that red dress on the second Christmas of her life gave me something beyond words. The feeling I got was like that original double whammy I’d had when I first pulled that dress from the box of my mother’s best things, only now it was:

My daughter is wearing a dress that her grandmother bought for her at a yard sale.

My daughter is wearing a dress that her grandmother bought for her at a yard sale.

It’s so simple it breaks my heart. How unspecial that fact is to so many, how ordinary for a child to wear a dress her grandmother bought her, but how very extraordinary it was to me.

I suppose this is what I meant when I wrote what I did, sweet pea, about how it is we cannot possibly know what will manifest in our lives. We live and have experiences and leave people we love and get left by them. People we thought would be with us forever aren’t and people we didn’t know would come into our lives do. Our work here is to keep faith with that, to put it in a box and wait. To trust that someday we will know what it means, so that when the ordinary miraculous is revealed to us we will be there, standing before the baby girl in the pretty dress, grateful for the smallest things.

Yours,

Sugar

#cheryl strayed#dear sugar#therumpus#writer#inspiring#inspirational#personal growth#advice#family#motherhood#journey#ordinarymiraculous#cheryl#strayed#THE FUTURE HAS AN ANCIENT HEART

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boyz to Men: The Rumpus Interviews Alex Kazemi

by Miah Jeffra

Alex Kazemi’s novel New Millennium Boyz (Permuted Press, 2023) is a divisive book. It may piss you off, may offend you, may have you nodding your head to its reality-TV reality, a hazily self-reflexive gesture of the early millennium’s particular brand of pop culture consciousness. Heavily dialogical and uniquely sparse in reflective voice—despite being written from teen Brad Sela’s perspective—the novel reads more like a screenplay stitched together by saturated scenes of suburban banality and angst, largely concerning Brad’s troubling friendship with goth-kid Lusif and emo-stoner Shane. There is so much violent, racist and sexist overtone to the three teens’ interactions that it feels like we’re watching a mashup of The Doom Generation and Beavis and Butthead. Think Brett Easton Ellis. Think Larry Clark. Think deeply unsettling, especially as readers influenced and informed by the last two decades forced to look back.

Born, raised and currently living in the Vancouver area, Kazemi began working in the fashion and music industry at 15, and emerged as a pop culture journalist, working for Dazed, King Kong and Prim, among others. His early experience inhabiting this—as Kazemi calls—“post-empire world” clearly influences the novel, flooded with sharp critiques and observations of Y2K music, from Blink 182 to Fiona Apple, backdropped by the popularization of the internet and reality-TV.

New Millennium Boyz serves to indict our recent past as a caustic soup of creative expression, cynicism and techno-reality, a Baudrillard-ian horror film where the characters won’t stop watching themselves, and through gritted teeth simultaneously implore the reader, have we changed all that much? Using our current techno-reality, Kazemi and I chatted over Zoom to explore this question.

* * *

The Rumpus: We obviously see your knowledge of music and culture and fashion all over this book. Why did you decide that you needed to write this story as a novel?

Alex Kazemi: When I was 18, I started writing notes. I uploaded the first 50 pages onto Tumblr and a lot of teenagers really resonated with it. I got a lot of messages and, as viral as things could go in 2013, it did. It wasn't initially concerning style or aesthetic or anything. I was only taking from what I knew back then. As I grew up, however, the meanings of those initial pages changed. I lost a certain innocence.

As the world became crazier, as my 20s became more turbulent, there were more intense emotions that I wanted to explore. I had to grow, practice, change, and evolve. This book is so different from the original Tumblr manuscript, but the reason it was a novel was because that's just what felt right.

Rumpus: In several moments in the novel, the dialogue runs together so much that you don't even know who's speaking. The characters blur. Why?

Kazemi: I remember working with my editor on the locker room scene where the boys are talking about girls and porn. I was like, “I have to include speaker indicators.” They're like, “No, because all the boys are just the same in the scene. They're all amorphous, facets of the extreme teen-boy experience.” I think that in that era—maybe every era—there were so many mixed messages of what it means to be a boy, what masculinity meant, the violence of it, that’s not explored much in art.

Rumpus: Why do you have it set right at the dawn of the millennium?

Kazemi: I was perplexed and fascinated by our culture becoming so obsessed with Y2K. I wanted to unmask the corporate, buzz-feed-type nostalgia for that era and create more of a gritty, voyeuristic version of teen-hood. What if we take the voice from American Pie and explore the darker aspects of that world? I wanted to show that these themes that we're dealing with currently in our culture, of hyper reality and the Internet age, emerged back then.

Rumpus: You're very interested in the consumerism that is bound in this hypermediated society. Do you feel like we were worse off 20 years ago than we are now?

Kazemi: I often think about this. We look at Gen Z, who are so openly queer, openly celebrating their POC-ness, anything that makes them different. And then we rewind twenty years ago and it looks like we are now better off. How have we been able to make that progress if we didn't have social media, if technology didn't accelerate in the way it did? I don't know the answer to that. But it's often something I think about. I think maybe in certain ways we were more intelligent about our moderation around screen time. You open a magazine, and eventually it ends, right? An Instagram feed doesn't end. A TikTok feed doesn't end.

Rumpus: Do you feel like that is one of the functions of all the sexism, the racism, the homophobia of the characters in your novel, for us to look back twenty years ago and see how far we've come?

Kazemi: I particularly made the characters like that to show what the culture amongst white men was encouraging at the time. It’s definitely not a celebration of it, but more so holding up a mirror to how those issues were presented in that time period. Twenty years later we're supposed to look at it and be like, “Holy fuck, this is how people talked. This was normal. Why was it like that? And why did we allow it to be like that? And why did we associate it with creative freedom?”

Rumpus: So, you’re suggesting media of the time was packaged in this effort to celebrate creative freedom, when in fact, it seemed to indulge in aspects of our own culture’s hatred?

Kazemi: If kids are listening to Adam Carolla on Love Line and he says something objectionable, they don’t have the clear ability to critique it like we do now. They were inside of it. They were participating in the culture. For us to say that our media doesn't encourage certain impulses in us is just absurd. Of course, we can't control who is consuming the media. I'm not saying violent movies creates school shooters, but I'm saying there are unwell people who are not equipped to handle this content, and it can unfold into madness.

Rumpus: One of those examples would be the protagonist, Brad?

Kazemi: Brad is in this masochistic male friendship [with Lusif], yet he also fears losing him. A level of trauma bonding.

Rumpus: Do you think that is born of some desperate need for young males to share intimacy, that they would let someone like Lusif abuse them, because at least they were experiencing an intimacy with another male, without reproach, that isn't fostered in our culture?

Kazemi: Absolutely. I think that these young men who, for instance, pledge a frat are really looking for a shared intimacy amongst other men. They're desperate for communication and physical intimacy that feels safe for them and their sexuality. Brad was so intimacy-starved that he would let someone bad like Lusif into his life. I think boys in our culture are in that state of starvation a lot, and that's pretty scary to think of what they're capable of doing in that malnourished state. I was trying to display the way teenage boys have to manage being a good boy to their family while behind the scenes they have all these unresolved feelings around sex and violence and drugs. They're this weird, netherworld creature that's not a boy, not a man, managing this middle-space. They are processing a lot of unresolved sexual energy. It's something that is provoking a very extreme reaction in readers, which is so weird to me because I never predicted that. I definitely have a better understanding of the prose that most people like, and I don't think I went the traditional route.

Rumpus: You averted the traditional route by being so heavily dialogical without much access to Brad’s interiority?

Kazemi: That's interesting because a lot of people say that's a lot of telling. But it's fucked up because in my head, I was like, “Oh, I'm showing their reality. I'm almost creating reality TV, setting it up with minimum imagery, and then getting to watch the conversation.”

Rumpus: Maybe these critics are summoning classic tropes of storytelling when reviewing this book. I think what you said resonates with me. The book mirrors the reality television narrative. Minimal situation and lots of dialogue and reaction.

Kazemi: There are these moments of suburban romanticism in our culture, of hanging out in the 7-Eleven parking lot, smoking—American rites of passages that would resonate with the typical Total Request Live watcher. I definitely did try to create those tiny moments of suburban claustrophobia. The book resembles a three- to four-hour nineties teen movie. It's like an extended cut. I'm shocked that I did it and also that I was so insistent with my publisher to stay true to my vision. Obviously, it's not something I want to do again, this type of style, but it is a bit jarring.

Rumpus: You say you're probably not going to write a novel like this again. Do you have another project on the horizon?

Kazemi: I definitely have ideas, but much like the Madonna school, I'm all about reinvention, thinking of different ways to tell stories. I want to stay in the novel medium and I want to write more books, but I have to figure out what comfort zone I’m going to push against next.

________________________________________

Miah Jeffra is author of four books, most recently The Violence Almanac and the novel American Gospel. Miah is co-founder of Whiting Award-winning queer and trans literary collaborative, Foglifter Press, and teaches creative writing and decolonial studies at Sonoma State University.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Thrilled to interview @thisisejkoh for #therumpus on writing "unguarded, whole, and ready." This @ucirvine alum's memoir, The Magical Language of Others, was a heartrending and heart-mending book I couldn't get enough of. Link in bio! 💌 @ucienglish @ucihumanities @tin_house @kundimanforever #ejkoh #interview #memoir #ineztan https://www.instagram.com/p/B89fTjJAQxe/?igshid=16srbg1suvku4

1 note

·

View note

Link

"i wanted folks to have to reckon with the book in the same ways black folks have to reckon with their two identities…"

t'ai freedom ford discusses "& more black" (Augury Press)with The Rumpus Poetry Book Club.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

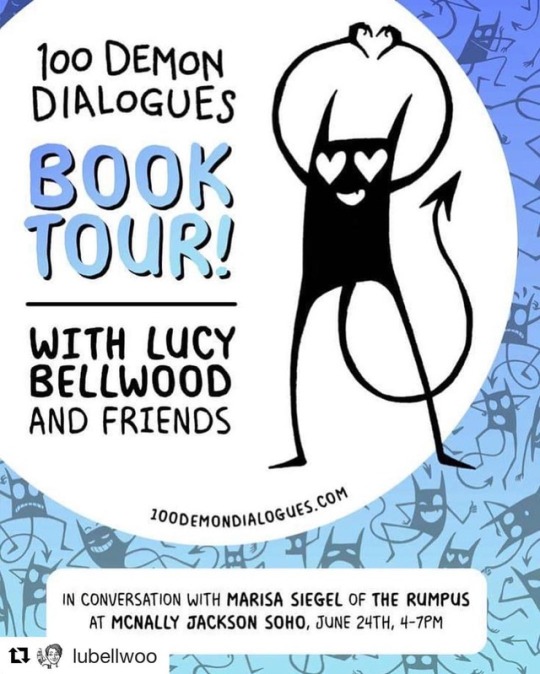

.@lubellwoo reports: NYC! I'll be at @mcnallyjackson in SoHo from 4-7pm this Sunday. This is one of the stops I'm looking forward to the most because I get to talk with Marisa Siegel of #TheRumpus! Come on out. #nycevents #indiebookstore #selfcare #nycbookstores

1 note

·

View note

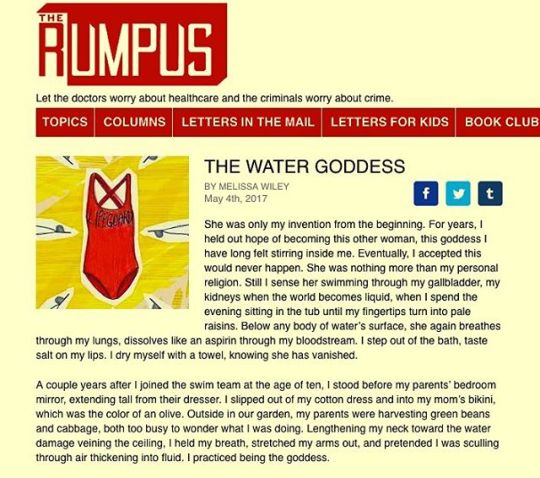

Photo

Take a break from RL 'cause it hurts a lot and read this story by Melissa Wiley 'cause it only aches a little. Now up on The Rumpus 💛💔❣️💛💔💛❣️💔💛❣️ 💛💛💛🖤❣️ 💛🖤❣️💛 💛🖤 💛❣️🖤❤️❣️ 🖤💛💔🖤 #art #art🎨 #artist #artwork #artistoninstagram #drawing #instaart #illustrator #illustragram #illustration #illustrationgram #lit #lit✨ #lifeguard #literature #thewomenwhodraw #therumpus #rumpus #lookrookie #obsesseewithit #goddess #watergoddess #water #magazine (at Williamsburg, Brooklyn)

#illustragram#illustration#literature#art🎨#drawing#lookrookie#rumpus#artist#illustrator#lit✨#obsesseewithit#artistoninstagram#instaart#water#therumpus#magazine#thewomenwhodraw#watergoddess#art#lifeguard#goddess#artwork#illustrationgram#lit

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Write drunk, edit caffeinated." ~ alternative Hemingway quote 📖☕️📝🖌🖍#edit #editing #selfedit #selfedits #poems #WriteLikeAMotherFucker #writelikeamotherfuckermug #rumpus #therumpus #writer #writing #amwriting #englishmajor

#englishmajor#therumpus#edit#writelikeamotherfuckermug#selfedit#writer#writing#writelikeamotherfucker#amwriting#rumpus#poems#editing#selfedits

1 note

·

View note

Text

& without

my summoning, nonetheless, here

it is, invoked : the question

of asking. who gets to. who answers.

who is free—and where —to speak.

Poem: Raena Shirali ‘God Of New Beginnings, I celebrate You Poorly’ in The Rumpus

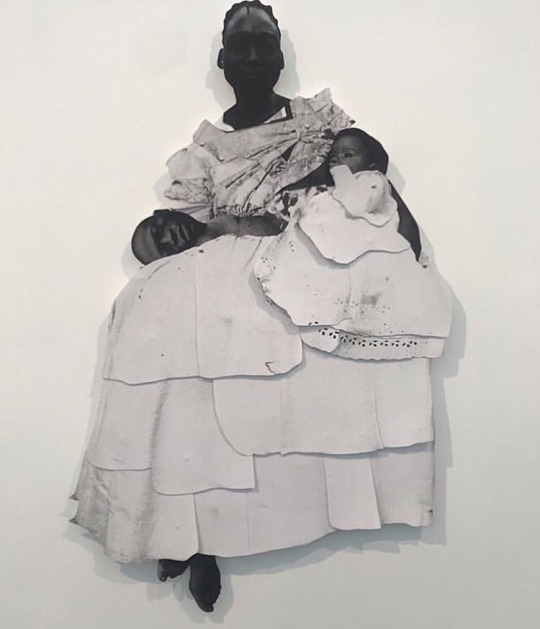

Art: Frida Orupabo from Medicine for a Nightmare

#fridaorupabo #art #therumpus

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Beyond the Bars: A Mini Interview with Geneva Phillips

By Cass Lewis

Geneva Phillips is currently an incarcerated writer completing the end of a prison sentence in Oklahoma. She writes about a broad range of topics and has been actively involved in a writing program called Poetic Justice in addition to PEN America’s Prison Writing Mentor Program, which pairs more than 300 working writers on the outside with close to 300 incarcerated writers. She and I were paired about a year ago, well after she wrote these award-winning pieces. It’s called a mentorship program, but it has prompted me to think about how it’s really a partnership, as we both exchange writing advice and build community.

Phillips’ short memoir piece, “Holding,” received Honorable Mention and was just published in PEN America’s 2023 Prison Writing Awards anthology, Thank the Bloom. Her award-winning work was also included in the PEN America Prison Writing Awards anthologies, The Named and The Nameless (2018), and Variations on an Undisclosed Location (2022). She is the author of the memoir, Disappearing in Glimpses (Mongrel Empire Press, 2020).

I was delighted when she agreed to share her thoughts on writing and community through an interview conducted via letter and telephone.

***

The Rumpus: When you think about your writing community, how would you describe it?

Geneva Phillips: I would describe it as a constellation of hopefuls. We write together inside to find our voices and perfect them. We write with the hope of being heard. Though the distance of our confinement makes it challenging, those outside keep us buoyant with ideas, opportunities, feedback, and encouragement. I think it all culminates into a reciprocating microcosm. We hope together, with each other, for each other. We write, we listen, the confinement loses some power.

Rumpus: While writing is a solitary activity, I’ve found there is something potentially transformative about a group of people all responding to the same prompt and sharing our work. How has writing in groups impacted your work as a writer?

Phillips: I’m definitely a better writer for the writing groups I’ve had the privilege to grow with. The relationships and community make writing a transformative activity.

Rumpus: Do you have any favorite writing prompts you’d like to share?

Phillips: One of my favorites was to open with the line, “Something happened,” and that one line produced a wealth of good material in our writing group. Also, we recently tried some unorthodox story writing where we used a selection of words and random sequence writing to produce short stories. I’m going to send you the directions so you can try it.

Rumpus: Thank you. I’m always looking for new prompts. Who are some authors you admire?

Phillips: Tanith Lee, Sandra Cisneros, Joy Harjo, N.K. Jemisin for the bottomless depths of beauty of their words. Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson for limitless imagination and the sheer scope of their world building.

Rumpus: When did writing become a central focus for you?

Phillips: I discovered writing poetry when I was eleven or twelve. It was a way to capture complicated feelings and experiences in words and helped me to process them. After I was incarcerated, I had a lot more time to write and I utilized it to practice other methods.

Rumpus: Recently, in the PEN America newsletter, “Works of Justice,” the Prison and Justice Writing Mentorship Coordinator, Jess Abolafia, and another award-winning incarcerated writer named Leo Paul Carmona discussed your memoir piece, “The Hard Part.” Carmona wrote, “Geneva Phillips’ piece hit me to my very core…It resonated so much, because I have lived and continue to live every word of what she wrote… Much like Geneva pointed out, we form friendships and bonds as we all go through the struggle of what it is to live in captivity. I have found that our bonds with others are solidified and strengthened when we face the same struggles together. Geneva speaks to the trauma of having friends ripped from you, or for us to be ripped away from them.” When you see the impact your work has on readers, how does this add to your sense of community and how does it align with your intentions as a writer?

Phillips: With my nonfiction work, essays, and memoirs, I wanted to expose the parts of being incarcerated that no one thinks to talk about. The emotions behind the injustices. The humans having human experiences inside the boxes where people believe only monsters exist. To have confirmation that others find commonality in experiences I write about just proves to me the importance of writing about these things.

Rumpus: When you’re writing, do you picture a specific audience for your work?

Phillips: I really don’t. Mostly, I just wonder how it will land with my writing group. They’re the thermostat I use to gauge the success of a story.

Rumpus: Where do you find inspiration for your writing?

Phillips: The strangest places. A misheard sentence. Happenstance and serendipity. Inspiration is everywhere.

Rumpus: You have written poetry, memoir, short stories, and other forms. When you write, do you know when you first start working on a piece what form it will take, or is it a surprise or does this process change each time?

Phillips: With poetry, I usually know the tone I’m looking for in a piece. With my memoir, it was a little different. I had an idea, but found the individual pieces fit their own tone. I have found short stories to be a surprise from the beginning to the end.

Rumpus: What are you working on now?

Phillips: I’m writing a genre-crossing collection of fictional short stories.

Rumpus: One of the things I love about your work is how it is haunting and raw but with a refined beauty, like a controlled burn. How do you maintain that balance between revealing what is harrowing while recognizing the universal humanity and even offering what could be interpreted as hope?

Phillips: Well, first of all, thank you. I’m going to save that description forever. I think that it’s really just the truth about life that reveals itself when I write. Life is terrible. Life is beautiful. In the midst of the beautiful, we hurt. And in the midst of the terrible, we hope.

Rumpus: If you were going to share some advice with someone who just started writing, what would you tell them?

Phillips: Write. Practice your craft. Hone your skills. Read. Read things you don’t want to read. And find other people who also read and write to be in community with.

Rumpus: What is some helpful advice you’ve received about writing?

Phillips: Probably the most helpful words of advice anyone has ever given me were “go with your gut.” That was you! It was so helpful when I was revising. And at the end of the day, you have to go with what’s right for you.

Rumpus: Well, thanks. I’m glad it was helpful. It’s hard when different readers give different feedback and it’s all so subjective. I’d like to share a passage that really stuck with me from your poetic memoir, Disappearing in Glimpses: “So, she’s trained her eyes to not-see. Not see the trees. The wooded hills. The fields. The road leading away. She only sees the fence. The razor wire. This is reality. This is where reality is contained. A few square acres. For all intents and purposes, the rest of the world does not exist to her just like she does not exist to the rest of the world.” Can you talk a little bit about how you decided to write this story in a close third-person perspective, and how this poetic memoir came to be?

Phillips: The whole idea for this was inspired by The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros. I had never encountered a book written in the form of vignettes. Once I had, my immediate thought was, I could write a book in this style. The POV was a decision I made so that the book would be not just my story. It is my story, but it is also archetypally all our stories. We, women of the locked boxes.

***

Cass Lewis is an award-winning writer, currently working on a memoir that explores mental health, mass incarceration, and the climate crisis. Connect with her here: www.CassLewis.com.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

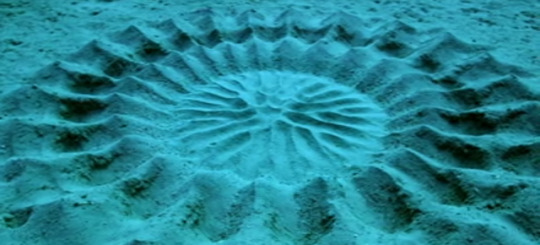

My essay on desire, a failing political imagination, and puffer fish mating rituals is up on The Rumpus. “I didn’t understand my gender or sexuality until I saw puffer fish mate... Talk about desire, talk about potential”.

https://therumpus.net/2017/02/the-saturday-rumpus-essay-ideal-lover/

0 notes

Photo

19 authors suggest reading recommendations in the age of Trump over at The Rumpus. My picks include 'Citizen' by Claudia Rankine and 'Model Disciple' by Michael Prior. Thank you to The Rumpus for the opportunity to participate in this article. - GS "Copies of George Orwell’s 1984 sold out during the first month of Donald Trump’s presidency. Demand for the book has been so overwhelming that the publisher has issued a 75 000-copy reprint. If your copy hasn’t arrived yet, here are nineteen authors on the books you should be reading in the age of Trump." Link to article here and in my bio: (http://therumpus.net/2017/02/a-recommended-reading-list-for-trumps-america/) #therumpus #alternativefacts #nineteeneightyfour #donaldtrump #readinglist #instagrampoets #poetrycommunity #writingcommunity

#writingcommunity#therumpus#readinglist#nineteeneightyfour#donaldtrump#instagrampoets#poetrycommunity#alternativefacts

0 notes

Link

"I’m realizing now that part of the conversation I was having with myself when writing this book was about time. Maybe time travel? Memory is kind of all twisted up in time travel, right? The way our memories are situated in the present body remembering but also in the archival body that experienced whatever we’re remembering. It’s an inaccessible method of time travel because the content keeps shifting the more that we remember it. Or do not remember it."

-Samantha Giles, author or Total Recall (Krupskaya, 2018) in The Rumpus!

1 note

·

View note

Link

Art is important because it allows for visioning, re-visioning. It lets us be linked to our labor, our lives. Art is about reclaiming agency. It allows for grief, rage, tenderness within resistance. Example number 2:

The Rumpus is an online literary journal that is running a feature titled Inaugural Poems. From their poetry section:

Official inaugural poems are a strange beast. There have only been five of them and the one we recognize as the first, Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright,” wasn’t composed for President Kennedy’s inauguration. Frost recited it when the sun’s glare off the snow made the poem he’d written, “Dedication,” impossible to read. But perhaps the real problem with inaugural poems is that they’re too connected to a moment which celebrates rather than questions or critiques power, and in times like these, where we face governance by people who seem at best uninterested in and at worst hostile to the democratic and social progress this country has made over the last 200+ years, it is our duty as poets to stand as witness and critic.

So for this inauguration, we have solicited work from fourteen poets, and we’ll run these poems as features daily from January 7 through January 20. We hope you will celebrate this work and share it with your friends and family, colleagues, and acquaintances. The poems will go live on the homepage of The Rumpus at 3 p.m. PT during weekdays and at noon PT on weekends. After the jump, find a complete list of the poets whose work will be featured in this series.

1/7: Leila Chatti

1/8: Kaveh Akbar

1/9: Julie Marie Wade

1/10: Jaswinder Bolina

1/11: JoAnn Balingit

1/12: Rajiv Mohabir

1/13: Lynn Melnick

1/14: Hanif Willis Abdurraqib

1/15: Eve L. Ewing

1/16: Julian Randall

1/17: Brian Oliu

1/18: Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

1/19: Kyle Dargan

1/20: Airea Matthews

To visions and re-visions, friends.

0 notes

Photo

Go to #TheRumpus and read "Salt" by C.A. Carey! I'm head over heels for her story. ✨ ✨ ✨ ✨ ✨ ✨ #illustration #instaart #drawing #angels #lookrookie #colorpencil #sketch #drinkanddraw (at Williamsburg, Brooklyn)

2 notes

·

View notes