#trochaic meter

Text

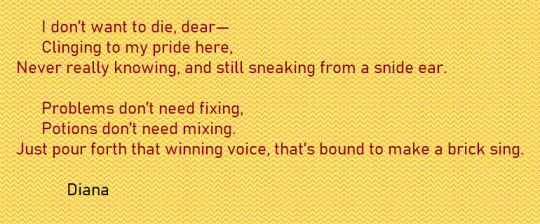

"Serious Moonlight" - a poem written 8/02/2019

#2019#college years#tercets#trochaic meter#trochaic trimeter#trochaic heptameter#feminine rhymes#rhyme scheme#poem#poetry#poets on tumblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

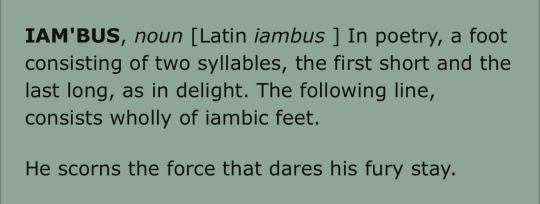

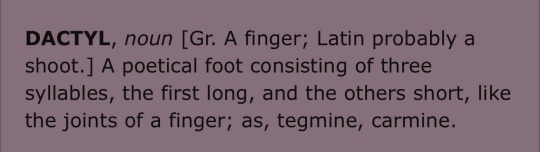

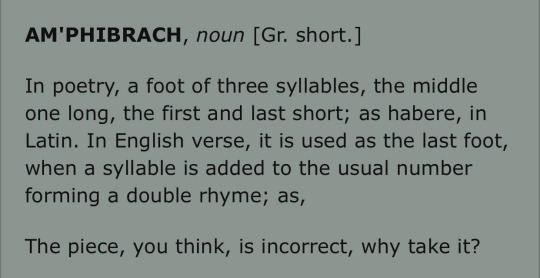

Binary Feet

Ternary Feet

#poetry#iambic meter#trochaic meter#spondaic meter#anapestic meter#dactylic meter#amphibrachic meter

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

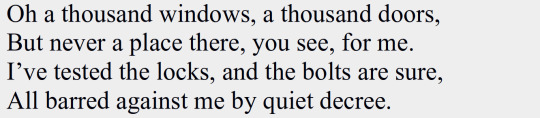

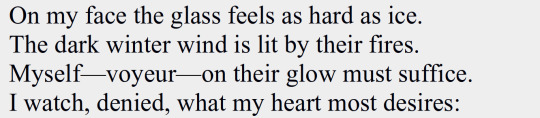

THE BEGGAR

#poetry#poem#writing#own writing#love#irregular meter#iambic tetrameter#anapaestic tetrameter#trochaic tetrameter#anapaest#quatrain#elegy#loneliness#family#peusdo-metrical

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

really really funny to remember this guy exists, check to see if people on RYM felt the same way I did after hearing one song, and be instantly validated multiple times over

#music#of course he's a nepo/industrial plant or whatever#boring BORING music with NO sharp edges#fred again#you know how people are always talking about white boys manufactured in labs for youtube drama? it's like that with spotify#some random person with a name in trochaic meter (sometimes all caps) with their description just “hi” gets recommended#and they inexplicably have 4 million plays on the most formulaic songs known to man#god i feel old

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sprawling farther than the eyes see, green lush

Fields and sun’s azure skies. Golden discs, two,

Slice through clouds before they curve back around—

falling star from heavens, crashes to Earth.

A painful slash upon the neck, blood drips—

A mourning lover cries.

Where is morning? The sun won’t rise.

What purple o’er his head, a flower blooms

In his stead. Failed healing, he takes last breaths.

There is no cure for Fate dictated death.

#hyacinthus#apollo#i’m taking a poetry intensive creative writing class this quarter#this was for my study on meter#i switched from trochaic pentameter to iambic pentameter to signify the change in tone#and the trimeter and tetrameter lines stand out to me a lot#she’s errrr rhythmically ambiguous tho. like half the words are stressed literally only bc i say so#let me know what you think!!#hyacinthus and apollo#classics#greek mythology#mythology#poetry#original work#love#greek myth retellings#mine#meter#my poetry

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

It may sound crude and self-absorbed

But I'm jealous of my lovers

Each and every one discovers

How much my eagerness is curbed

I'm too much, that much is certain

Nails too long still after clipping

Charge too fast and end up tripping

Tears behind the shower curtain

I wish that I existed twice

To madly love, not as a vice

But to receive the same in turn

Indulge in reciprocity

The breathtaking ferocity

Of a love too sharp to spurn

Dee

#sonnet#poetry#polyamory#trochaic into iambic#I feel like I really did something with the meter here#to elaborate a bit - it's not like my lovers don't give me enough. It's just that I tend to be very intense due to a myriad of conditions.#And I don't blame anyone for being unable to keep up with that - people have different energy levels and that's okay.#My lovers love me in their own ways and I appreciate it a lot#It just gets a little lonely sometimes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinda late to my own party here but I JUST realized that one of the best ways to portray Dragon speech in a hypothetical HTTYD musical is to have them sing in a whole different meter to the humans.

Like so far the Vikings have pretty much exclusively sung alternating stressed and unstressed syllables (iambic and trochaic), so if I make the humans always sing that way, and I make the dragons mostly sing in a different lyrical font as it were, it could be similar to the actual change in font dragonese gets in the books.

#httyd books#musings on the hypothetical httyd musical#dragonese is spoken in amphibrachs and dactyls you heard it here folks

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not gonna clown on these ppl or anything I just wanted to say that trochaic meter doesn’t make me uncomfortable cause it’s bars. Like in epic rap battles of history Stephen king vs Edgar Alan Poe

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

We know what Ninth House poetry is like (terrible!) but we should talk about which meters and poetic forms are in vogue for the other Houses. Some initial thoughts:

The Second: Meter? Iambic or maybe trochaic. Absolutely has to be one of the two-syllable feet though. Number of feet can vary. Form? Couplets. The Second is about epigrams, about the sort of pithy little poem that you could engrave onto the handle of a weapon or use as a grave marker. Short and regimented. They don't *do* long-form.

The Third: Dactyls all the way babyyyyy! Lots of playful/light verse; tend to think everyone else takes poetry much too seriously. A bunch of funky little closed forms with triplets and repeating lines. You know, the sparkly kind where you don't really say anything but it's great for showing off how clever you are. Also. Villanelles.

The Fourth: Iambic tetrameter. Lots of cross-rhymed quatrains; little emphasis on closed forms.

The Fifth: They get iambic pentameter, the lucky bastards.

The Sixth: The sestina is absolutely the most Sixth House poetic form in existence. I bet they have competitions where they're given the end words and have a time limit to complete their poems. I bet Palamades has written sad sestinas about Dulcie. Probably dactylic hexameter even though I kind of feel like that's too cool for them. They might also use Alexandrines bc they're both six-footed and insufferable.

The Seventh: Ballad meter! In the real world we think of this as alternating lines of iambic tetrameter and trimeter, but if you throw it all on one line you can call it iambic heptameter instead. If you want. Great for poems about melancholy and death! Also they write a lot of sonnets (14 lines!), especially the Petrarchan form.

The Eighth: I feel in my heart that they look down on purely syllabic meters and also the concept of rhyming and insist that the only worthwhile poetry is some accentual-syllabic Beowulf shit. Irl this manifests as four alliterative accented syllables per line with the strongest emphasis on the last one. You *could* just string two lines together to make eight accented syllables and call it a day, but that isn't stupid enough. Merely contemplating Eighth and Ninth house poetry should be enough to give you a headache. It is one line with eight stresses. It's awful. Every stressed syllable has to alliterate except the final one, and when a poet finally reaches the end of the line everyone watching applauds in sheer relief.

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awesome choice, @kaylinelizabeth4004 ! If you played the character, I'm sure you have a lot of great insight on this speech already, but let's break it down!

Sorry if you already know some of the stuff I'm going to talk about, I just want to make sure all my explanations are accessible for all levels!

Also this started out as being trying to be objective and ended with me just breaking down my own interpretation so I apologize haha. But enough disclaimers:

For background, The Tempest is generally thought to be Shakespeare's last play, or at least the last one he wrote by himself. For this reason, some scholars interpret Prospero's final speech as Shakespeare's farewell to the stage.

Fatherhood shows up in many of Shakespeare's plays, partly because it was impractical to write many mother characters due to there being no female actors, but also potentially because Shakespeare himself was a dad. We think he probably had at least four children; the oldest daughter, Susanna; two twins, Judith and Hamnet; and probably at one illegitimate son, William. As you may know, Shakespeare's son Hamnet died when he was eleven. His two remaining daughters both married.

So Shakespeare expresses feelings of fatherhood in many of his plays, possibly due to his love for his own children. Hamlet is obviously the most common example of this, but The Tempest is also very relevant to this topic due to Prospero's love for his daughter.

Additionally, Prospero is a creator; in loose terms, an artist. Much like Shakespeare, he commands the stage and invents scenarios, controlling characters and events like a writer would. Prospero references "The great globe" in act four (I believe), and "Prospero's Books" have been widely speculated on, and some interpretations I've seen have gone so far as to suggest that Prospero is making all the magic up, or writing the whole story to entertain himself or Miranda.

All to say, I favor the interpretation that Shakespeare wrote Prospero's last speech as a farewell to the stage and to the audience.

So, if we get into the line by line breakdown, let's start by looking at the meter.

Notably, Prospero's final speech is not written in iambic pentameter. It's closer to trochaic tetrameter — trochaic is the opposite stress pattern of iambic, meaning that the first syllable is stressed rather than the second. Now for a tetrameter, lines should be eight syllables, but for the most part Prospero falls short of this, coming in at seven syllables in almost every line. So it's a weird meter, to say the least. Usually when Shakespeare writes in this reverse-heartbeat pattern, he's trying to creep the audience out. The witches in Macbeth sometimes speak like this.

All this said, there's different verse-types wound all through the speech. Some iambic, some just prose... It's weird!

So what was Shakespeare's purpose in writing it this way? Well, it was certainly intentional. As I've mentioned in past posts, when studying Shakespeare, one of the first things I learned was that we never blame things on sloppy writing, or on the meter. Shakespeare just didn't write like that; his choices were very intentional. When he breaks out of verse, he wants us to notice. Like here:

"Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have ’s mine own,"

From the first couplet here, the syllable count and the trochaic pattern is unusual. Only the rhyme scheme is familiar.

In my opinion, the answer to why Shakespeare choses to write in this style here is evident from the first line of the speech. He is casting off his charms; his poetry, his familiar meter, and all his tricks. In the context of the play, of course, these lines make sense, but they also make sense in the overarching context of Shakespeare's life. If we view it as Prospero sort of transforming into Shakespeare in this moment, it works. Of course, this is only one possible interpretation, but I favor it, as I said above. In writing 'What strength I have 's mine own,' it's not too much of a stretch to imagine Shakespeare casting off a character, and also casting off his poetry in a way, and writing from the heart.

The lines from 'which is most faint' to ' in this bare island' are pretty plot-relevant, so I'll skip over them.

But when we get to this part:

"But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands."

Again, I feel like I can see right through this speech to the man who wrote it.

If you've read Midsummer Night's Dream, these lines are reminiscent of Puck's final address to the audience. Puck's line, "Give me your hands if we be friends" refers to his asking the audience to clap for him and the other players.

I like to think that Shakespeare wrote plays because he loved them, but we also know that he wrote to make money. When the plagues closed the theaters, he printed and sold his writing. He wrote for the people and hoped to draw them in. So it's totally possible that writing plays could've felt like 'bands,' or an obligation of sorts. And with the support of audiences, and their applause, or 'good hands,' he was able to amass a small fortune, and make a name for himself. He owed so much to his audience!! And he totally knew it.

So, he continues on:

"Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,"

Continuing to express gratitude to his audience for their support of him through the story of Prospero's journey home. Now, the use of 'project' is interesting to me, because it implies that Shakespeare had an overarching idea of what he wanted to do with his writing.

This is a tangent which I won't elaborate on here, but I am a major hater of the widely accepted theory that Shakespeare had no desire for a legacy or for his plays to live on after him. I could go on and on about that, but I won't. I just bring it up because his mention of a desire to please, presumably to please the audience, and his 'project,' again presumably to entertain the audience and even maybe to create a legacy for himself and his family.

There is a parallel to be drawn between Prospero's use of spirits in the play and Shakespeare's use of characters or actors. As we know, Shakespeare often manipulates stories with the use of the supernatural, including The Tempest itself. The relation between "spirits to enforce" and "art to enchant" is also interesting, because we can see that Shakespeare directly associates this kind of supernatural occurrences with his own art.

And in the final few lines:

"And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free."

Something about Shakespeare ending his career with rhyming couplets makes me so crazy. The same format as the ending of a sonnet, and he uses it to end what was probably his last play.

This is part of why it annoys me so much to hear people say that Shakespeare never wanted a legacy. These words, to me, do not read as the thoughts of a man who had no desire to be remembered. In this final section, he directly references his own ending, (or Prospero's, but I'm going off of the Shakespeare's-goodbye theory), and once again calls upon the audience to free him with their good will and their favor. His tacit apology for any faults or "crimes" seems to speak to the entirety of his career, and his desire to be freed by indulgence speaks to his choice to end with a comedy rather than a tragedy. This is an optimistic choice that makes me happy to think about, especially considering how many tragedies were likely inspired by his own life.

So yeah! I love this speech, and a goal of mine is to one day direct a production of The Tempest. I have a lot of ideas for it, haha.

I hope you find this interesting. Thanks for sending in an ask!! Also, sorry for any typos haha, I didn't proofread very thoroughly.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If It Makes You Coffee" - a poem written 1/19/2024

#2024#iambic meter#trochaic meter#iambic trimeter#trochaic trimeter#feminine rhymes#masculine rhymes#slant rhymes#rhyme scheme#poem#form poetry#quatrains

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a p r i o r i

Mother growls, the pups obey

Thund’rous skies all painted grey

Lighting strikes, the puppies fray

Bless your allergies

Mother wolf up in the skies

Spare the world your teary eyes

Nature breathes, the modern sighs

Myths and fallacies

Torn from cloth both stretching past

Wisdom from the first and last

Bread and blood, the soul’s repast

Tame the seven seas

If a drop is out of hand

Blame it on the dogs

Chaos was upon the land

Ere the breathe of Gods

—rudysassafras

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyway, I was trying to find out what poetic meter is most used in Latvian, because Latvian (almost) always puts the stress on the first syllable, so for obvious reasons you wouldn't be using iambs, and anyway along the way I discovered the Cabinet of Folksongs, which I thought some of you would think was neat.

(It's trochaic meter, by the way. Sometimes dactylic, but usually trochaic.)

#cabinet of folksongs#also i was reminded that i can't travel to latvia without first finding a decent lactase supplement#because they use sour cream heavily and i currently cannot have it and i miss it and i would not be able to resist#vegan substitutes just don't do it it's cream but there's no sour#anyway don't cry 4100 mushrooms in latvia okay?

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's your favorite dialogue for Oaths so far? (Either chapter 10 or as a whole!)

WIP asks!

Chapter 10 has a lot of dialogue! Of course being the penultimate chapter, the boss battle, the wyrmening, etc., almost all of it is actually horribly spoiler-y. There's some biggish canon departures (not saying which canon! maybe both!) I'd like to keep a hat on for now. My favourite bit is currently written in common meter and maybe the MOST spoiler-y lines of all. There's also a bit of gratuitously poetic Middle English (a bit I've had jotted down for AGES, before I'd written almost anything at all), other meter (currently slapdash iambic pentameter, possibly to be changed to trochaic who-the-fuck-knows, lovingly absolutely the fault of @that-banhus), Big Declarations, bravado, rage, fear....all the good shit!

Anyways I've realized I don't want to share ANY of it and give even a scrap away so I'll say for Oaths so far it's obviously "Do you fuck, son of man?" mostly because it made it to a tee-shirt, but massive mentions to: Hob describing the hardships of life in Chapter 4, Duncan's first song in Chapter 2 that I was SO nervous about the reception of, that entire first multi-character convo, the first Hob/Dream dialogue that quotes the ballad, any dialogue that includes words I discovered in Dictionary of the Scots Language, the exchange in Chapter 4 where Dream says Hob is hardly a terrible man and Hob says not here he's not, honestly any of their flirting, any of the lads' banter, Hob in Chapter 5 saying he wants to be like a summer sheep, dialogue that echoes and plays with dialogue in Sandman canon, the chapter 7 tame/wild bit, Dream unraveling the truth of his curse in Chapter 8 against his will, Sande telling Hob how proud he is, any monologue (your girl loves monologues),.... i'm just gonna stop hahahaha

#asks#wip asks: oaths edition#asking the dialogue person their fave dialogue is bullying and this is the MESS of an answer you deserve <3#oaths#the sandman

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

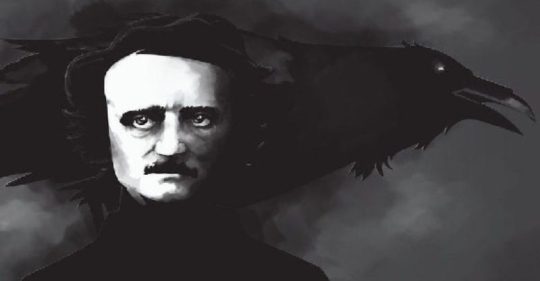

The Raven, by Edgar Allen Poe.

Today, we will be talking about The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

The Raven is a poem that was first published in 1845 and has become one of the most famous poems in western literature. It is a narrative poem that tells the story of a man who is visited by a raven one night as he is grieving the loss of his lover,Lenore.

The poem is written in trochaic octameter, which means that each line has eight stressed syllables followed by eight unstressed syllables. The use of this meter gives the poem a haunting, rhythmic quality that adds to its eerie atmosphere(reading this as child was like watching a horror movie ngl).

It begins with the narrator reading a book as he tries to forget about his lost love, However he is interrupted by a tapping at his chamber door, and when he opens it, he finds nothing there. He repeats this process several times, becoming increasingly agitated, until a raven enters his room and perches upon a bust of Pallas Athena(the audacity of this bish).

The narrator tries to engage the raven in conversation, asking it questions about its identity and its purpose for visiting him. the raven only responds with the repeated phrase "Nevermore," which gradually drives the narrator to despair.

Throughout the poem, Poe employs a range of literary techniques to create a sense of foreboding and uneas. For example, he uses alliteration and internal rhyme to create a sense of repetition and monotony, which reflects the narrator's growing frustration with the ravens unchanging response. Additionally, he uses vivid imagery to create a sense of darkness and decay, with references to the "bleak December" night and the "grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous" raven.

Overall i find that the The Raven is a haunting and evocative poem that has stood the test of time, and has definitely made an impression on me as a writer. It has also in my opinion been a significant influence on the development of modernism in poetry. Modernist poets, such as T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, were influenced by Poe's use of rhythm and meter, as well as his ability to create a unified, cohesive work of art. Ithink jts safe to say it had a profound impact on the poetry scene, helping to establish new forms of poetry and new ways of thinking about the art of poetry. Its influence can still be seen in modern poetry, where poets continue to experiment with new forms and styles, where symbolism and the use of the first-person narrator remain prominent features of the art form.

Throughrough out it leads your heart into a frenzy that lingers long after the poem has been read, undoubtedly one of my favourite reads. Feel free to Share you own thoughts and interpretations.

For those who haven't had the pleasure of reading this poem before here you go! Enjoy!

The Raven

BY EDGAR ALLAN POE

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

“’Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door—

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;—

This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

“Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you”—here I opened wide the door;—

Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?”

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!”—

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

“Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore—

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;—

’Tis the wind and nothing more!”

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door—

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning—little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door—

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as “Nevermore.”

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing farther then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.”

Then the bird said “Nevermore.”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

“Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore—

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never—nevermore’.”

But the Raven still beguiling all my fancy into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore—

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er,

But whose velvet-violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

“Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee—by these angels he hath sent thee

Respite—respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore—

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting—

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

#the raven poem#edgar allan poe#famous poets#poetry#poetry analysis#poems on tumblr#literature analysis#literature#poetblr#dailypoetryforyou#writeblr#daily poems#poem analysis#writers and poets

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

when the ceaseless watcher joke doesnt retain the trochaic meter

5 notes

·

View notes