Text

String Quartet in D Major, K. 499 "Hoffmeister": II. Menuetto & Trio. Allegretto

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mozart - Così Fan Tutte Overture for 2 Guitars (sheet music)

Mozart - Così Fan Tutte Overture arr. for 2 Guitars (sheet music)

https://rumble.com/embed/v18d2px/?pub=14hjof

Così fan tutte by Mozart

Cosi fan tutte, i.e. The School of Lovers, is a playful drama in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and a booklet in Italian by Lorenzo da Ponte. Taken by number KV 588. The first time that was represented Così fan tutte was at the Burgtheater in Vienna, on 26 January 1790. Thus, all of them are one of the three operas of Mozart, for whom Da Ponte wrote the libretto. The other two collaborations between Da Ponte and Mozart were The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni. Although it is usually said that it was created due to the suggestion of Emperor Joseph II of Habsburg, recent investigations have not supported this idea. There is evidence that the contemporary of Mozart, Antonio Salieri intended to play the book, but left it unfinished. In 1994, John Rice discovered two Salieri trios in the National Library of Austria. The literal translation of the title 'Così fan tutte' is So Do All, and less literally: 'they all do the same' or 'Women are like that'. These words are sung by the three men when they talk about fickle female love, in the second act, picture III, just before the end. Da Ponte used the verse 'Così fan tutte le belle' before Le Nozze di Fígaro (in act I, scene 7). Musically speaking, the critics arouse the symmetry of Mozart's opera: two acts, three men and three women, two pairs, two personalities in the extreme (Don Alfonso and Despina), practically the same number of arias for all soloists. For other critics, symmetry was a value proper to Italian opera of the eighteenth century. All coincide in revealing the abundance of parts dedicated to the ensembles: out of the finale, Mozart composed six duos, five trios, one quartet, two quintets and three sextets. Read the full article

0 notes

Video

youtube

Franz Schubert: Piano Trio in E flat Major - Andante con moto

Vienna Mozart Trio; Irina Auner - Piano; Daniel Auner - Violin; Diethard Auner - Cello

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

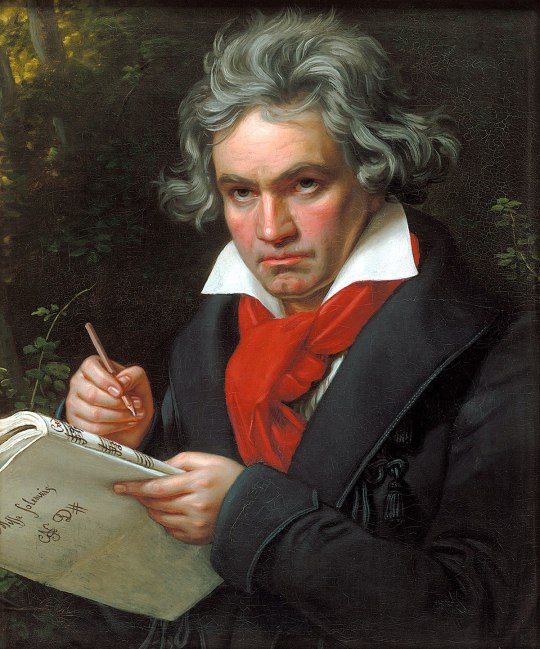

Beethoven and Other Composers

This is a collection of Beethoven’s thoughts on other composers as well as other composers’ thoughts on him. This list currently focuses on some of Beethoven’s contemporaries as of September 16, 2021. This will be updated in the future. There will be a second (and maybe more) post in the future containing many more composers I left out here. If anyone has any more information on these people, leave it below! If anyone knows any other composers’ thoughts on Beethoven or vice versa that I did not mention, please let me know! Also, please inform me if I have made any errors in this post.

(Post updated October 1 and October 20)

(https://images.app.goo.gl/kahgbDzLCf2TiYZi8)

Cherubini

(https://images.app.goo.gl/EYXAxNcoixbjrmjw9)

Beethoven on Cherubini

Beethoven and Cherubini met in Vienna in 1805. Beethoven loved Cherubini’s music and appropriated aspects of his style. When Beethoven was asked who, apart from himself, he thought was the greatest living composer, he paused a little startled and then said “Cherubini”. Beethoven had also said another time that Cherubini was “Europe’s foremost dramatic composer.”

Beethoven wrote to Cherubini in 1823, “I am enraptured whenever I hear a new work of yours and feel as great an interest an it as in my own works—in brief, I honor and love you.”

Beethoven loved Cherubini’s Requiem in C minor, he even wanted it performed at his funeral.

Beethoven sent Cherubini a letter around the time of writing his Missa Solemnis, but apparently Cherubini never got it.

Beethoven wrote to Cherubini, “I prize your works more than all others written for the stage.”

Beethoven said to Louis Schlasser, “Say all conceivable pretty things to Cherubini,—that there is nothing I so ardently desire as that we should soon get another opera from him, and that of all our contemporaries I have the highest regard for him.”

According to Seyfried, Beethoven said, “Among all composers alive Cherubini is the most worthy of respect. I am in complete agreement, too, with his conception of the ‘Requiem,’ and if ever I come to write one I shall take note of many things.”

(https://images.app.goo.gl/JUm1npSP3smEEeKMA)

Cherubini on Beethoven

Cherubini didn’t like Beethoven. He described Beethoven as “an unlicked bear cub” and said that his style was rough. He also said that Beethoven was “brusque.” He attended the first performance of Beethoven’s Fidelio and didn’t really like it.

Franz Joseph Haydn

(https://images.app.goo.gl/FtzwWobpnG1J8VUUA)

Beethoven on Haydn

Haydn was Beethoven’s teacher. He started teaching Beethoven in 1792. He was dealing with a teenage/young adult Beethoven, so Beethoven was obviously going to be difficult.

Beethoven was horrified when Haydn suggested that he write “pupil of Haydn” underneath his name on Op. 1 Piano Trios as a marketing trick. Beethoven felt that he learned nothing from Haydn so he did not write that he was a “pupil of Haydn” on Op. 1 Piano Trios.

Haydn suggested that Beethoven should not publish the third of the piano trios (C minor trio) because it would not have much public acceptance. Beethoven was offended at this remark because he believed that the third piano trio was the best of the set. He believed that Haydn envied the C minor trio.

This event clearly did not soil their relationship since Beethoven dedicated his next opus to Haydn.

On Haydn’s 76th birthday, Beethoven knelt down before Haydn and fervently kissed the hands and forehead of Haydn.

Ries said, “While composing Beethoven frequently thought of an object, although he often laughed at musical delineation and scolded about petty things of the sort. In this respect, “The Creation” and “The Seasons” were many times a butt, though without depreciation of Haydn’s loftier merits. Haydn’s choruses and other works were loudly praised by Beethoven.”

Beethoven said, “Do not tear the laurel wreaths from the heads of Handel, Haydn, and Mozart; they belong to them,—not yet to me.”

(https://images.app.goo.gl/4CZdMUYJb9zcWJaD9)

Haydn on Beethoven

Haydn had an interest of taking Beethoven on his second trip to London.

Haydn genuinely liked Beethoven’s compositions and wished the best for him. When they met for the first time, Beethoven showed him his WoO 87 (Cantatas on the Death of Emperor Joseph II) and WoO O88 (Elevation of Emperor Leopold II) and Haydn was very impressed.

Haydn wrote a letter to the Elector Max Franz and said that Beethoven would fill the position of the greatest musicians in Europe. He also said that he wished Beethoven could stay with him longer.

Haydn called Beethoven “Der große Mogul” behind his back. He was basically calling Beethoven “big shot.”

Beethoven’s friend Ferdinand Ries said this, “I knew [all of Beethoven’s teachers] well; all three valued Beethoven highly, but were also of one mind touching his habits of study. All of them said Beethoven was so headstrong and self-sufficient (selbstwollend) that he had to learn much through harsh experience which he had refused to accept when it was presented to him as a subject of study.”

Haydn said to Beethoven, “You have a lot of talent and you will acquire even more, a lot more. You have an inexhaustible abundance of inspiration, you will have thoughts no one else has had, you will never sacrifice your thoughts to tyrannical rule, but you will sacrifice the rules to your fantasies. You give me the impression of a man who has many heads, many hearts, many souls.” (I read this on the French Wikipedia so if the translation is iffy, I am very sorry)

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

(https://images.app.goo.gl/KHT78BgaKf4hnNRP9)

Beethoven on Hummel

For some time, Beethoven and Hummel were friends. However, after some incidents, they became less close.

Beethoven wished for Hummel to improvise at his memorial concert.

Hummel made keyboard arrangements of Beethoven’s works and Beethoven did not agree with it. He disliked the style of Hummel’s arrangements.

Beethoven and Hummel had two completely different piano playing philosophies. This caused them to butt heads many times.

According to Carl Czerny, Beethoven’s student, Beethoven’s fans thought that “Hummel lacked all real imagination, his playing was monotonous as a hurdy-gurdy, the application of his fingers was like a garden spider, and his compositions were mere arrangements of themes by Mozart and Haydn.”

Ignaz von Mosel, an Austrian court official, composer, and musician, commented on the differences between Beethoven’s and Hummel’s styles. He said, “Herr Louis van Beethoven, whose playing is marked by velocity, power and precision, even more by his compositions, while Herr Joh. Nepomuk Hummel’s is recognized by it’s order, clarity and grace.”

(https://images.app.goo.gl/CBU3vHFuu2iCt8D3A)

Hummel on Beethoven

Beethoven’s arrival in Vienna is said to have shattered Hummel’s self-confidence.

Hummel said about Beethoven, “I readily admit that today Ludwig is far superior to me as a composer. But probably not as a virtuoso at the piano.”

Beethoven was commissioned by Prince Nikolaus II Esterhazy to write a mass. Beethoven wrote his Mass in C and it was performed in Eisenstadt were Hummel was Kapellmeister. The performance did not go well and the prince made a comment behind Beethoven’s back which Hummel reportedly laughed at.

When Beethoven was one his deathbed, Hummel traveled all the way from Weimar to Vienna to see Beethoven. Hummel visited Beethoven three times on his death bed.

On Beethoven’s death bed, Hummel got Beethoven’s signature so Hummel could protect his compositions from illegal copying.

Hummel was present at Beethoven’s funeral. He was a pallbearer.

According to Czerny, Hummel’s fans “reproached Beethoven that he abused the fortepiano, that he was deficient in purity and clarity, that he, through the use of the pedal, only produced confused noise, that his compositions were far-fetched, unnatural, without melody and irregular.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(https://images.app.goo.gl/opTvcPiSsn3azVsx8)

Beethoven on Mozart

Young Beethoven played Mozart’s piano concertos in Bonn and was heavily influenced by him. Young Beethoven once thought he accidentally plagiarized off Mozart. He wrote a passage in C minor and under it wrote, “This entire passage has been stolen from Mozart Symphony in C, where the Andante in 6/8 from the... [he stopped writing here].” He wrote the supposedly plagiarized passage below the text, however, no such passage was ever found in a Mozart symphony that we know of.

Beethoven meet Mozart in Vienna in 1787. According to Ignaz von Seyfried, this is what happened:

“Beethoven made a short stay at Vienna, in the year 1790, whither he had gone for the sake of hearing Mozart, to whom he had letters of introduction. Beethoven improvised before Mozart, who listened with some indifference, believing it to be a piece learned by heart. Beethoven then demanded, with his characteristic ambition, a given theme to work out; Mozart, with a sceptical smile, gave him at once a chromatic motivo for a fugue, in which, al rovescio, the countersubject for a double fugue lay concealed. Beethoven was not intimidated, and worked out the subject, the secret intention of which he immediately perceived, at great length and with such remarkable originality and power that Mozart's attention was rivetted, and his wonder so excited that he stepped softly into the adjoining room where some friends were assembled, and whispered to them with sparkling eyes: ‘Don't lose sight of this young man, he will one day tell you some things that will surprise you!”

You can read Hummel’s perspective on Mozart and Beethoven’s meeting here: https://www.henle.de/blog/en/2020/01/27/beethoven-meets-mozart/ (Warning! It’s long.)

Beethoven said Mozart had “a fine but choppy way of playing, no legato.”

Though he wasn’t exactly bashing Mozart’s operas, he believed that he would never write music to librettos with similar themes to Mozart’s. He said, “I need a text which stimulates me; it must be something moral, uplifting. Texts such as Mozart composed I should never have been able fo set to music. I could never have got myself into a mood for such licentious texts. I have received many librettos, but, as I said, none that met my wishes.”

I’m putting this quote I already showed in the Haydn part too: “Do not tear the laurel wreaths from the heads of Handel, Haydn, and Mozart; they belong to them,—not yet to me.”

Beethoven said, “I have always reckoned myself myself among the greatest admirers of Mozart, and shall do so till the day of my death.”

Beethoven said this to Cramer after hearing Mozart’s piano concerto in C minor: “Cramer! Cramer! We shall never be able to compose anything like that!”

Beethoven said according to Seyfried, “‘Die Zauberflöte’ will always remain Mozart’s greatest work, for in it he for the first time showed himself to be a great German musician. ‘Don Juan’ still has the complete Italian cut; besides our sacred art ought never permit itself to be degraded to the level of foil for so scandalous a subject.”

The Baronin Born asked Beethoven what his favorite Mozart opera was and he said it was ‘Die Zauberflöte.’

(https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-van-Beethoven)

Mozart on Beethoven

When Mozart heard Beethoven play for the first time, he said, “Mark that young man, he will make a name for himself in the world.”

Mozart died shortly after Beethoven came to Vienna so they did not get to interact much.

——————————————————————————

Second Part: https://theferretgeneral.tumblr.com/post/662537492215496704/beethoven-and-other-composers-part-two (Schubert and Rossini)

Third Part: https://theferretgeneral.tumblr.com/post/662710737497735168/beethoven-and-other-composers-and-musicians-part

Fourth Part: https://theferretgeneral.tumblr.com/post/669959288702337024/what-did-brahms-liszt-and-schumann-think-of

Sources:

Beethoven and Haydn: Their Relationship. ClassicFM. https://www.classicfm.com/composers/beethoven/guides/beethoven-and-haydn-their-relationship/

Did Beethoven Meet Mozart? ClassicFM, 6 March 2018. https://www.classicfm.com/composers/beethoven/guides/beethoven-and-mozart/

Haydn and Beethoven. Popular Beethoven. https://www.popularbeethoven.com/haydn-and-beethoven/

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) - Reproduktion eines Schabkunstblattes, vielleicht von Franz Wrenk. B 1618, Beethoven-Haus Bönn. https://www.beethoven.de/en/media/view/4767400939487232/Johann+Nepomuk+Hummel+%281778-1837%29+-+Reproduktion+eines+Schabkunstblattes%2C+vielleicht+von+Franz+Wrenk?fromArchive=4886601146564608

Jones, Rhys. Beethoven and the Sound of the Revolution in Vienna, 1792-1814. Cambridge University, 12 November 2014.

Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) - Stich von Friedrich Wilhelm Bollinger. B 2383, Beethoven-Haus Bönn. https://www.beethoven.de/en/media/view/5065980724117504/Luigi+Cherubini+%281760-1842%29+-+Stich+von+Friedrich+Wilhelm+Bollinger?fromArchive=4886601146564608

Predota, Georg. Ludwig van Beethoven to His Fellow Musicians. Interlude, 22 September 2020. https://interlude.hk/ludwig-van-b-and-his-fellow-musicians/

Predota, Georg. Ludwig van Beethoven to His Fellow Musicians II. Interlude, 20 October, 2020. https://interlude.hk/ludwig-van-b-and-his-fellow-musicians-ii/

Salieri and Beethoven. Popular Beethoven. https://www.popularbeethoven.com/salieri-and-beethoven/

Seiffert, Wolf-Dieter. Beethoven meets Mozart. The genesis of Beethoven’s Mozart Variations WoO 40 according to Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s memoirs (first published). G. Henle Verlag, 27 January 2020. https://www.henle.de/blog/en/2020/01/27/beethoven-meets-mozart/

Somlai, Petra. Two Viennese piano schools: Beethoven and Hummel. Royal Conservatory, 2019. https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/555906/559358

#classical music#beethoven#van beethoven#ludwig van beethoven#cherubini#luigi cherubini#music#haydn#joseph haydn#franz joseph haydn#Johann Nepomuk Hummel#hummel#johann hummel#mozart#wolfgang amadeus mozart#music history#theferretgeneral#yes I know I’m bad at MLA citing#info#part i#beethoven and other composers

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

Whoops, ended up making another fanservant because of a cat pic

It's my fanservant's kid this time

Also, in case my handwriting is unreadable:

Francesco

Violinist

Antonio's older brother and music teacher

Has Glaucus, Dodola and Mayari in his spirit

Girolamo

Francesco's son

Went to his Uncle Antonio in Vienna to study music

Clarinettist

How to these two have wikipedia pages but not one of the incarnations of friggin Tamamo-no-Mae the demon fox

Anyways that's certainly a very unique trio, I can see Glaucus being the lead given the theme of prophecy and outer beings (DGPs, the Avenger schtick, etc), with Dodola influencing the music given her rituals. Meanwhile Mayari can be thrown at just about anything and make it interesting.

Looking into Girolamo that actually does sound like a neat general character concept, someone who took an instrument that was being phased out of use entirely, and decided if it was all they could play they'd play it so well they wouldnt be allowed to phase him out with it. Double so when it's an instrument Mozart is notable for making use of (Basset Horn)

#fgo#fgo mozart#fgo salieri#fanservant stuff#'because of a cat pic' *raises fist to the sky* MOZAAAAAAAART

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell us everything you know about Mozart?

Wow okay so I can try??? My memory is insanely bad but ofc!!

So. I guess I'll just do a biography with like.... everything i know

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in 1756, Salzburg, Austria. He was baptized with the name Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, but he really didn't like it- in fact, most of his life he went by different names. (Gottlieb, Wolfgango Amadeo, Wolfgang Amade)

He grew up with his father (Leopold Mozart), his mother (Anna Maria Mozart), and his sister (Nannerl Mozart). He learned violin and piano at the age of 4, which his father saw potential in. Leopold being a musician, he had the ability to help him compose, writing down the notes while young Wolfgang played the pieces. At the age of 6, Mozart wrote a minuet and a trio for keyboard, the future number 1 of the Köchel catalogue. But with his father, Leopold practically controlled Mozart's life up until his twenties. He controlled where he went, what he studied, where he stayed, and much more; but Wolfgang didn't mind, he really enjoyed the performing. He performed for the French king Louis XV and Madame Pompadour, then for the English family, where he was taught by Bachs son, Johann Christian Bach. In England, he wrote his first symphony and 40 other works. Around the time of 1777, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was 21, and was out of his fathers grasp, since he was busy with the Prince-Archbishop Colloredo. He was meant to go back to Paris with his mother, until he met Aloysia Weber, who he fell in love with; and just so happened to be the sister of his future wife, Constanze Weber. Instead, he went on a concert trip with the Webers to the Hague, which enraged his father. It didn't bring any money into the family. In Paris 1778, Wolfgang watched his mother pass away on her deathbed. Doctors were called, but none arrived. She had grown sick as Wolfgang was unable to find work, barely any food came in, and the room they stayed in was constantly dark and cold. In 1779, Aloysia had became famous and had rebuffed Mozart. Mozart and his music had matured around this point. He went to Vienna, where his career soon picked up once again. In 1781, he fell in love with Constanze, but in fear of his father controlling the relationship he didnt dare tell him that he planned on marrying her. In 1782, they got married. Mozart constantly composed. When it came to money, he was now very well off. At the time where Mozarts first son, Raimund Leopold was born, he met Joseph Haydn, who taught him how to write and compose quartets.

In 1787, Wolfgangs father died. Mozart was extremely upset. Filled with grief, and desperate for money, he set to work on his famous opera "Don Giovanni". It was an outlet for his despair to work on it; the seducer of women going to hell. Later on in Mozarts life, the enjoyment of his music was stricken down. He never played for the fun of it, he only played for the money. When the money came in, he spent it carelessly. In 1790, Mozart went into debt once more. Nobody wanted to hear from the small unattractive man when names like "Salieri" were in high demand. Near the end of his life when he was writing his by far most famous opera "The Magic Flute", he was most sad and lonely. His wife wasn't at his side and had been staying at a health spa. To write the opera without his source of happiness and support drove him even further into the ground. In 1791, Mozart accepted commissions from anyone as long as they were putting down money. While in the middle of composing The Magic Flute, he had received an anonymous commission to write a Requiem. Alongside that, he had received a commission to finish an opera within 4 weeks. He was growing to be weak, more depressed every single day. His friends often wrote that he always had a glass of wine in his hand, not ever going one day without drinking. He was under so much stress, his time management had never been worse: but he needed the money. His Requiem is often connected to Antonio Salieri, due to the famous movie "Amadeus" only making the previous rumors grow. It was believed that Salieri was the cause of his death, but in reality the two had a very professional and friendly relationship and had nothing but respect for each other. Salieri had nothing to do with the requiem, in fact, it was Count Franz Walsegg-Stuppach, a very small composer who wanted to perform it after the death of his wife and claim authorship for it. Fortunately though, Mozart lived to see the premier of The Magic Flute, which was overwhelmingly successful. He died happy, but pretty poor. Pretty sure he was burried in a mass grave too

#here <3#this took me forever to write goodbye#i know much more small facts but this is just the most important biography shit#mozart

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

02 BEETHOVEN’S TIMELINE

1770 Ludwig van Beethoven is born in Bonn 1776 Starts studying with his father, Johann van Beethoven, 1740?-92) 1778 Has his first public performance 1780 Begins studying the violin and viola under Franz Rovantini 1781 Studies composition and piano under Christian Gottlob Neefe 1782 Under Neefe’s supervision Beethoven publishes his first work “9 Variations in C Minor” 1787 Goes to Vienna and meets Mozart 1789 Attends the University of Bonn, plays in the court orchestra as a violist 1790 Meets Joseph Haydn 1794 Studies under Georg Albrechtsberger 1795 Publishes his first opus: Piano Trios, Op. 1 1799 Serves as piano teacher for Therese and Josephine Brunsvik 1800 Performs his first public concert in Vienna, Symphony No.1 and Piano Concerto No.1 1800 Takes Carl Czerny as his pupil 1801 Studies opera composition with Antonio Salieri 1802 Moves to Heiligenstadt, writes the Heiligenstadt Testament 1802 Publication of Violin Sonata No.5, Spring Sonata 1802 Publication Piano Sonata No.14, Moonlight Sonata 1803 Meets his greatest patron, Archduke Rudolph 1803 Composes Symphony No.3, intends to dedicate it to Napoleon 1804 Disillusioned with Napoleon, renames Symphony No.3 to Eroica 1805 France invades Vienna and the court escapes; Beethoven loses his job 1805 Composes Piano Sonata No.23, Appassionata 1806 Commissioned by Count Franz von Oppersdorff to write Symphony No.4 1806 Composes Violin Concerto in D major 1807 Composes Triple Concerto in C major 1808 Premiere of Symphony No.5 and No.6 at Theater an der Wien, Vienna. Beethoven plays his Piano Concerto No.4 1809 Receives an annuity of 4,000 florins from three noble patrons, an equivalent of $3,800,000 NTD today 1809 Composes Piano Concerto No.5, Emperor Concerto 1810 Writes "Für Elise" and proposes to Therese Malfatti but gets rejected 1811 Composes the Wellington’s Victory to commemorate the Battle of Vitoria, gains wide popularity 1812 Meets Johann Wolfgang Goethe 1812 Writes the “Immortal Beloved", Unsterbliche Geliebtet 1812 Conducts the charity concert commemorating the wounded soldiers of the Battle of Vitoria, performing his Symphony No.7 and Wellington's Victory 1814 Premiere of Symphony No.8 1815 The passing of Beethoven’s brother Caspar Carl van Beethoven; becomes one of the guardians of Carl’s son 1816 Starts using “conversation books” 1818 Starts composing Missa Solemnis 1820 Wins custody battle over his nephew Karl and determines to make Karl his successor 1822 Composes his last Piano Sonata, Op.111 1824 Premiere of Missa Solemnis and Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Choral Symphony 1825 Becomes an honorary member of Wiener Musikverein 1826 Plagued by illness. His nephew’s suicide attempt torments him greatly 1827 Beethoven dies in Vienna, at the age of 56

69 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Mozart - Symphony no. 36 in C Major, “Linz” (1783)

It’s always funny when you notice how your tastes change over time. I remember first getting into classical in middle school, and starting to listen to Mozart in high school. I found most of his stuff boring compared to Beethoven’s power and angst. But now I can’t get enough of Mozart, and his melodies keep playing over and over in my mind. The other day I ‘re-discovered’ this symphony after watching a video analysis by Richard Atkinson, focusing on the finale. Now I can’t get the first tune out of my head! This symphony is famous because of its background story. Mozart invited his then fiancée Constanze to Salzburg so she could meet his father and, hopefully, get his approval. He did not approve. That made their vacation awkward to say the least. On their way back to Vienna they stopped for a month in Salzburg to stay with aristocratic family friends, and the family wanted to hold a concert with his music. Problem was, Mozart wrote to his father, he didn’t have any scores with him, so he had to "work on a new one at head-over-heels speed”! People love this story because it plays into the myth of Mozart churning out masterpieces in one draft, and part of the tale is the claim that he only had five days to write it. That part of the story is probably fake, but regardless the resulting symphony is a lot of fun. It opens with a Haydnesque grand and slow introduction, letting chromatics take us away from the ‘simple’ key of C major. The strings dominate with the main melody in this movement while the winds color and decorate. Despite the relatively small orchestra, it has a very powerful sound when the energetic dance like motif comes in. The slow movement is in a 6/8 siciliano meter, and like that genre it has a soft swaying feel to it. The minuet feels more like a march, with the trio giving the melody to the only winds, turning into a duet between the oboes and bassoons. The presto finale opens with the earworm I mentioned, a melody that Atkinson describes as being something only Mozart could have written. Charming and with a lot of chromatics, and a fun colorful interjection from winds and brass. The finale is a sonata movement, and it includes a lot of compositional devices Mozart loved like canonic imitation for build ups. This symphony is a great example of how Mozart elevated the galant style that was fashionable at the time with Baroque complexity made ‘palatable’ with his lyricism and operatic writing. And honestly I don’t care that this tune will be on repeat in my head for the next week. Nothing wrong with daydreaming about Mozart.

Movements:

1. Adagio - Allegro spiritoso

2. Poco Adagio

3. Menuetto

4. Finale (Presto)

#Mozart#symphony#orchestra#classical#music#classical music#symphony orchestra#orchestra music#Mozart symphony#Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart#classiciam

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Austria & Vienna playlist

Hear that accordion high in the mountains? Hear the mountain orcs gathering? That’s the Austria & Wien playlist you are hearing. Mozart is waltzing to this one!

So, come across the streaming tides with might and glory or on a winternacht sit back and play this Austria playlist here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-iHPcxymC1-RX_IKMvSqyXYuO8PRMtBL

Have I left a song out? Forgotten some band or singer? Let me know here or on my Youtube channel. Danke!

AUSTRIA & WIEN

001 Falco - Vienna Calling 002 Rammstein - Wiener Blut 003 Pungent Stench - Shrunken And Mummified Bitch 004 Ultravox - Vienna 005 Austrian Death Machine - See You at the Party Richter 006 Trio Alpin - Die Berg haban an Gipfl 007 VANADIUM - Streets Of Danger 008 The Striggles - Die Nation 009 Leonard Cohen - Take this waltz 010 Andreas Aschaber - Tiroler Bergen Mit Andreas Aschaber 011 Ganymed - It Takes Me Higher 012 Die Grubertaler - Hey Reini spiel inz oans 013 Die GeiWaidler - Samma Ehrlich 014 Summoning - Might And Glory 015 Gary Numan - Vienna on the Telekon 016 Schones - Osttirol 017 Lehnen - Immer Fremd 018 Opus - A Night In Vienna 019 Harakiri For The Sky - Calling the rain 020 Dun Field Three - Lion 021 Edenbridge - The die is not cast 022 Mozart - Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (Serenade), K. 525; 1st. Movement 023 Billy Joel - Vienna, hey 024 BELPHEGOR - Conjuring The Dead 025 Falco - Expocityvisions 026 Lalo Schifrin - Danube Incident (Mission Impossible TV show OST) 027 Jose Feliciano - The Sound Of Vienna 028 In der Niederschwing - Folk song from Austria 029 Peter Brotzmann & Heather Leigh - Summer Rain 030 Hella Comet - Dice 031 Dornenreich - Zu Träumen wecke sich wer kann 032 Heidis KaBCken - Das kleine KaCken piept 033 Pungent Stench - Viva la muerte 034 Thom Sonny Green - Vienna 035 Abigor - In Sin 036 The Sound of Music Soundtrack - 8 - The Lonely Goatherd 037 Nachtruf - Geistwerdung 038 The Night Flight Orchestra - Domino 039 Der Blutharsch ~ Track XI [In The Hands Of The Master 040 John Cale - Dirty Ass Rock 'N' Roll 041 Tracker - Electrosmog 042 Novaks Kapelle - Not Enough Poison 043 Sex Jam - Junkyard 044 Alexandra - Sehnsucht 045 Speed Limit - 1000 Girls 046 Johann Strauss - The Blue Danube Waltz 047 Svarta -Tagesschleier 048 The Devil and the Universe - Turn Off, Tune Out, Drop Dead 049 L'ACEPHALE - Winternacht 050 Falco - Rock Me Amadeus 051 Hollenthon - To Fabled Lands 052 Mitra Mitra - Telescopes 053 Deathstorm - Await the Edged Blades 054 Melting the Ice in the Hearts of Men - Song of the Lower Classes 055 Asphagor - Aurora Nocturna 056 Kraftwerk - Autobahn (Single version 1974) 057 Garden of Grief - HiberNation 058 Redd Kross - Neurotica 059 Triumphant -Hellknights 060 Alte Sau - Maschinen 061 Rainhard Fendrich - I am from Austria 062 Insanity Alert - All Mosh No Brain 063 Korovakill - Waterhells 064 Trans-Siberian Orchestra - Vienna 065 Summoning - Across The Streaming Tide 066 Ein Tiroler wollte jagen - Austrian folk song 067 Von Thronstahl - Imperium Internum 068 Bulbul - Xx 069 Harakiri for the sky - I, Pallbearer 070 Belphegor - Necrodaemon Terrorsathan 071 Åtem - Perchta 072 Goden - Glowing Red Sun 073 Visions of Atlantis - Where Daylight Fails 074 Rainhard Fendrich - Haben Sie Wien schon bei Nacht gesehn 075 Flowers in Concrete- Sehnsucht 076 Abigor - Unleashed Axe-Age 077 Austrian Dukes of Derangement - Against Humans, Against Animals, Against Everything 078 Sylvain Cambreling · Klangforum Wien · Georg Friedrich Haas - In vain 079 Karg - Irgendjemand wartet immer 080 Velvet Underground - Venus in furs 081 Ewig Frost - High octane energy 082 Deathstorm - Human Individual Metamorphosis 083 Allerseelen - Gläserne Kugel 084 Erebos - Of Dawn and Dusk 085 Anomalie - Vision IV: Illumination 086 Ellende - Augenblick 087 Dornenreich - Eigenwach 088 Pungent Stench - Hypnos 089 Summoning - Kor 090 KONTRUST: - bomba 091 Disharmonic Orchestra - A Mental Sequence 092 Miasma - The Unbearable Resurrection of a Suspicious Character 093 Isiulusions - seas of darkness 094 Plague Mass - Living among maneaters 095 Ash My Love - Fire 096 Pazuzu - Bal of Thieves 097 The Striggles - Cold Song (Album - Version) 098 Die verbannten Kinder Evas - In Darkness Let Me Dwell 099 Nullify - Empty Shrine 100 Ringo Starr - Goodnight Vienna 101 Laibach - So Long Farewell 666 Austrian Death Machine - Ill Be Back Play the songs here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-iHPcxymC1-RX_IKMvSqyXYuO8PRMtBL See you at the Austrian playlist party Richter!!

#Austria#Austrian playlist#Summoning#Falco#Vienna playlist#rammstein#abigor#the striggles#pungent stench#bands from Austria#Austria playlist#alpine music#laibach#sound of music#mozart

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

XE3F8753 – Mijaíl Glinka (Михаил Иванович Глинка), Tikhvin Cemetery (Saint Petersburg)

Mijaíl Ivánovich Glinka (en ruso: Михаил Иванович Глинка; Novospásskoie, provincia de Smolensk, 1 de junio de 1804-Berlín, 15 de febrero de 1857) fue un compositor ruso, considerado el padre del nacionalismo musical ruso. Durante sus viajes visitó España, donde conoció y admiró la música popular española, de la cual utilizó el estilo de la jota en su obra La jota aragonesa. Recuerdos de Castilla, basado en su prolífica estancia en Fresdelval, «Recuerdo de una noche de verano en Madrid», sobre la base de la obertura La noche en Madrid, son parte de su música orquestal. El método utilizado por Glinka para arreglar la forma y orquestación son influencia del folclore español. Las nuevas ideas de Glinka fueron plasmadas en “Las oberturas españolas”. Glinka fue el primer compositor ruso en ser reconocido fuera de su país y, generalmente, se lo considera el ‘padre’ de la música rusa. Su trabajo ejerció una gran influencia en las generaciones siguientes de compositores de su país. Sus obras más conocidas son las óperas Una vida por el Zar (1836), la primera ópera nacionalista rusa, y Ruslán y Liudmila (1842), cuyo libreto fue escrito por Aleksandr Pushkin y su obertura se suele interpretar en las salas de concierto. En Una vida por el Zar alternan arias de tipo italiano con melodías populares rusas. No obstante, la alta sociedad occidentalizada no admitió fácilmente esa intrusión de "lo vulgar" en un género tradicional como la ópera. Sus obras orquestales son menos conocidas. Inspiró a un grupo de compositores a reunirse (más tarde, serían conocidos como "los cinco": Modest Músorgski, Nikolái Rimski-Kórsakov, Aleksandr Borodín, Cesar Cui, Mili Balákirev) para crear música basada en la cultura rusa. Este grupo, más tarde, fundaría la Escuela Nacionalista Rusa. Es innegable la influencia de Glinka en otros compositores como Vasili Kalínnikov, Mijaíl Ippolítov-Ivánov, y aún en Piotr Chaikovski. es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mijaíl_Glinka es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Cinco_(compositores)

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (Russian: Михаил Иванович Глинка; 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1804 – 15 February [O.S. 3 February] 1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country, and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music. Glinka’s compositions were an important influence on future Russian composers, notably the members of The Five, who took Glinka’s lead and produced a distinctive Russian style of music. Glinka was born in the village of Novospasskoye, not far from the Desna River in the Smolensk Governorate of the Russian Empire (now in the Yelninsky District of the Smolensk Oblast). His wealthy father had retired as an army captain, and the family had a strong tradition of loyalty and service to the tsars, while several members of his extended family had also developed a lively interest in culture. His great-great-grandfather was a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth nobleman, Wiktoryn Władysław Glinka of the Trzaska coat of arms. As a small child, Mikhail was raised by his over-protective and pampering paternal grandmother, who fed him sweets, wrapped him in furs, and confined him to her room, which was always to be kept at 25 °C (77 °F); accordingly, he developed a sickly disposition, later in his life retaining the services of numerous physicians, and often falling victim to a number of quacks. The only music he heard in his youthful confinement was the sounds of the village church bells and the folk songs of passing peasant choirs. The church bells were tuned to a dissonant chord and so his ears became used to strident harmony. While his nurse would sometimes sing folksongs, the peasant choirs who sang using the podgolosochnaya technique (an improvised style – literally under the voice – which uses improvised dissonant harmonies below the melody) influenced the way he later felt free to emancipate himself from the smooth progressions of Western harmony. After his grandmother’s death, Glinka moved to his maternal uncle’s estate some 10 kilometres (6 mi) away, and was able to hear his uncle’s orchestra, whose repertoire included pieces by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. At the age of about ten he heard them play a clarinet quartet by the Finnish composer Bernhard Henrik Crusell. It had a profound effect upon him. "Music is my soul", he wrote many years later, recalling this experience. While his governess taught him Russian, German, French, and geography, he also received instruction on the piano and the violin. At the age of 13, Glinka went to the capital, Saint Petersburg, to study at a school for children of the nobility. Here he learned Latin, English, and Persian, studied mathematics and zoology, and considerably widened his musical experience. He had three piano lessons from John Field, the Irish composer of nocturnes, who spent some time in Saint Petersburg. He then continued his piano lessons with Charles Mayer and began composing. When he left school his father wanted him to join the Foreign Office, and he was appointed assistant secretary of the Department of Public Highways. The work was light, which allowed Glinka to settle into the life of a musical dilettante, frequenting the drawing rooms and social gatherings of the city. He was already composing a large amount of music, such as melancholy romances which amused the rich amateurs. His songs are among the most interesting part of his output from this period. In 1830, at the recommendation of a physician, Glinka decided to travel to Italy with the tenor Nikolai Kuzmich Ivanov. The journey took a leisurely pace, ambling uneventfully through Germany and Switzerland, before they settled in Milan. There, Glinka took lessons at the conservatory with Francesco Basili, although he struggled with counterpoint, which he found irksome. Although he spent his three years in Italy listening to singers of the day, romancing women with his music, and meeting many famous people including Mendelssohn and Berlioz, he became disenchanted with Italy. He realized that his mission in life was to return to Russia, write in a Russian manner, and do for Russian music what Donizetti and Bellini had done for Italian music. His return route took him through the Alps, and he stopped for a while in Vienna, where he heard the music of Franz Liszt. He stayed for another five months in Berlin, during which time he studied composition under the distinguished teacher Siegfried Dehn. A Capriccio on Russian themes for piano duet and an unfinished Symphony on two Russian themes were important products of this period. When word reached Glinka of his father’s death in 1834, he left Berlin and returned to Novospasskoye. While in Berlin, Glinka had become enamored with a beautiful and talented singer, for whom he composed Six Studies for Contralto. He contrived a plan to return to her, but when his sister’s German maid turned up without the necessary paperwork to cross to the border with him, he abandoned his plan as well as his love and turned north for Saint Petersburg. There he reunited with his mother, and made the acquaintance of Maria Petrovna Ivanova. After he courted her for a brief period, the two married. The marriage was short-lived, as Maria was tactless and uninterested in his music. Although his initial fondness for her was said to have inspired the trio in the first act of opera A Life for the Tsar (1836), his naturally sweet disposition coarsened under the constant nagging of his wife and her mother. After separating, she remarried. Glinka moved in with his mother, and later with his sister, Lyudmila Shestakova. A Life for the Tsar was the first of Glinka’s two great operas. It was originally entitled Ivan Susanin. Set in 1612, it tells the story of the Russian peasant and patriotic hero Ivan Susanin who sacrifices his life for the Tsar by leading astray a group of marauding Poles who were hunting him. The Tsar himself followed the work’s progress with interest and suggested the change in the title. It was a great success at its premiere on 9 December 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos, who had written an opera on the same subject in Italy. Although the music is still more Italianate than Russian, Glinka shows superb handling of the recitative which binds the whole work, and the orchestration is masterly, foreshadowing the orchestral writing of later Russian composers. The Tsar rewarded Glinka for his work with a ring valued at 4,000 rubles. (During the Soviet era, the opera was staged under its original title Ivan Susanin). In 1837, Glinka was installed as the instructor of the Imperial Chapel Choir, with a yearly salary of 25,000 rubles, and lodging at the court. In 1838, at the suggestion of the Tsar, he went off to Ukraine to gather new voices for the choir; the 19 new boys he found earned him another 1,500 rubles from the Tsar. He soon embarked on his second opera: Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Alexander Pushkin, was concocted in 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was drunk at the time. Consequently, the opera is a dramatic muddle, yet the quality of Glinka’s music is higher than in A Life for the Tsar. He uses a descending whole tone scale in the famous overture. This is associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor who has abducted Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev. There is much Italianate coloratura, and Act 3 contains several routine ballet numbers, but his great achievement in this opera lies in his use of folk melody which becomes thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material is oriental in origin. When it was first performed on 9 December 1842, it met with a cool reception, although it subsequently gained popularity. Glinka went through a dejected year after the poor reception of Ruslan and Lyudmila. His spirits rose when he travelled to Paris and Spain. In Spain, Glinka met Don Pedro Fernández, who remained his secretary and companion for the last nine years of his life. In Paris, Hector Berlioz conducted some excerpts from Glinka’s operas and wrote an appreciative article about him. Glinka in turn admired Berlioz’s music and resolved to compose some fantasies pittoresques for orchestra. Another visit to Paris followed in 1852 where he spent two years, living quietly and making frequent visits to the botanical and zoological gardens. From there he moved to Berlin where, after five months, he died suddenly on 15 February 1857, following a cold. He was buried in Berlin but a few months later his body was taken to Saint Petersburg and re-interred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery. Glinka was the beginning of a new direction in the development of music in Russia Musical culture arrived in Russia from Europe, and for the first time specifically Russian music began to appear, based on the European music culture, in the operas of the composer Mikhail Glinka. Different historical events were often used in the music, but for the first time they were presented in a realistic manner. The first to note this new musical direction was Alexander Serov. He was then supported by his friend Vladimir Stasov, who became the theorist of this musical direction. This direction was developed later by composers of "The Five". The modern Russian music critic Viktor Korshikov thus summed up: "There is not the development of Russian musical culture without…three operas – Ivan Soussanine, Ruslan and Ludmila and the Stone Guest have created Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin. Soussanine is an opera where the main character is the people, Ruslan is the mythical, deeply Russian intrigue, and in Guest, the drama dominates over the softness of the beauty of sound." Two of these operas – Ivan Soussanine and Ruslan and Ludmila – were composed by Glinka. Since this time, the Russian culture began to occupy an increasingly prominent place in world culture. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mikhail_Glinka en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Five_(composers)

Posted by Enrique R G on 2019-09-12 09:20:20

Tagged: , Mijaíl Ivanovich Glinka , Михаил Иванович Глинка , Mijaíl Glinka , Михаил Глинка , Glinka , Глинка , Tikhvin Cemetery , Cementerio Tijvin , Тихвинское кладбище , New Lazarevsky , Ново-Лазаревским , Tijvin , Tikhvin , Тихвинское , San Petersburgo , Saint Petersburg , Санкт-Петербург , Peterburg , Piter , Питер , Петрогра́д , Petrogrado , Петроград , Leningrado , Ленинград , Rusia , Russia , Россия , Venecia del Norte , Window to the West , Window to Europe , Venice of the North , Russian Venice , Fujifilm XE3 , Fuji XE3 , Fujinon 18-135

The post XE3F8753 – Mijaíl Glinka (Михаил Иванович Глинка), Tikhvin Cemetery (Saint Petersburg) appeared first on Good Info.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Classical Era (1750 - 1825)

The Classical Era brought with it an addition of new instruments. The Double Bass, the Clarinet and the Piano. We also have new musical idioms such as the Solo Concerto often performed with piano, the Solo Sonata which was also solo piano or another instrument accompanied by the piano. As you can tell once the piano was invented it was used quite extensively. And rightfully so, the piano’s wide 7 octave range across 88 keys made it extremely versatile.

We’re also acquainted with Chamber music, a string quartet. Opera, Masses and Oratorios are still relevant. But one major game changer was the Symphony format.

Joseph Hadyn (1743 - 1809)

Franz Joseph Haydn was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the piano trio. His contributions to musical form have earned him the epithets "Father of the Symphony" and "Father of the String Quartet".

Haydn spent much of his career as a court musician for the wealthy Esterházy family at their remote estate. Until the later part of his life, this isolated him from other composers and trends in music so that he was, as he put it, "forced to become original". Yet his music circulated widely, and for much of his career he was the most celebrated composer in Europe.

He was a friend and mentor of Mozart, a tutor of Beethoven, and the older brother of composer Michael Haydn.

Source: Wikipedia

youtube

Symphony No. 88 4th Movement Finale: Allegro Con Spirito

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791)

We all know of him and his profound use of musical composition in film and media in modern times.

Mozart was a prolific and influential composer of the classical era.Born in Salzburg, Mozart showed prodigious ability from his earliest childhood. Already competent on keyboard and violin, he composed from the age of five and performed before European royalty. At 17, Mozart was engaged as a musician at the Salzburg court but grew restless and travelled in search of a better position. While visiting Vienna in 1781, he was dismissed from his Salzburg position. He chose to stay in the capital, where he achieved fame but little financial security. During his final years in Vienna, he composed many of his best-known symphonies, concertos, and operas, and portions of the Requiem, which was largely unfinished at the time of his early death at the age of 35. The circumstances of his death have been much mythologized.He composed more than 600 works, many of which are acknowledged as pinnacles of symphonic, concertante, chamber, operatic, and choral music. He is among the most enduringly popular of classical composers, and his influence is profound on subsequent Western art music. Ludwig van Beethoven composed his early works in the shadow of Mozart, and Joseph Haydn wrote: "posterity will not see such a talent again in 100 years".

Source: Wikipedia

youtube

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770 - 1791)

Beethoven was a German composer and pianist. A crucial figure in the transition between the classical and romantic eras in classical music, he remains one of the most recognized and influential musicians of this period, and is considered to be one of the greatest composers of all time.Beethoven was born in Bonn, the capital of the Electorate of Cologne, and part of the Holy Roman Empire. He displayed his musical talents at an early age and was vigorously taught by his father Johann van Beethoven, and was later taught by composer and conductor Christian Gottlob Neefe. At age 21, he moved to Vienna and studied composition with Joseph Haydn. Beethoven then gained a reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and was soon courted by Prince Lichnowsky for compositions, which resulted in Opus 1 in 1795.

Source: Wikipedia

youtube

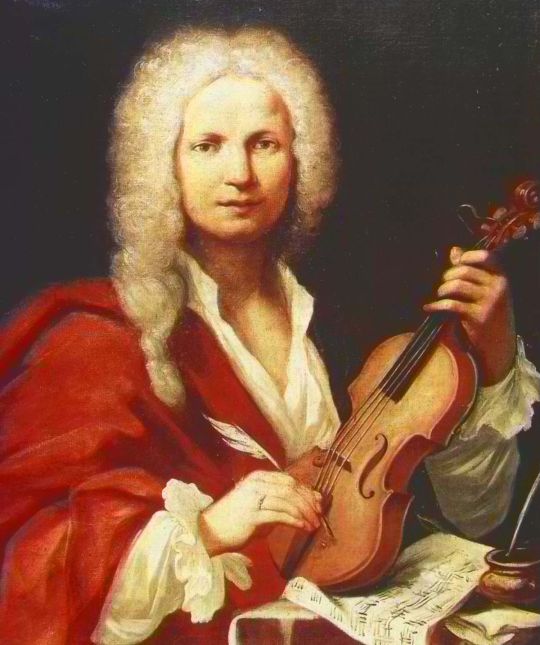

Antonia Vivaldi (1678 - 1741)

Vivaldi, the Baroque musical composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher, and priest. Born in Venice, the capital of the Venetian Republic, he is regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He composed many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as the Four Seasons.Many of his compositions were written for the all-female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children. Vivaldi had worked there as a Catholic priest for 1 1/2 years and was employed there from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for royal support. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died, in poverty, less than a year later.

Source: Wikipedia

youtube

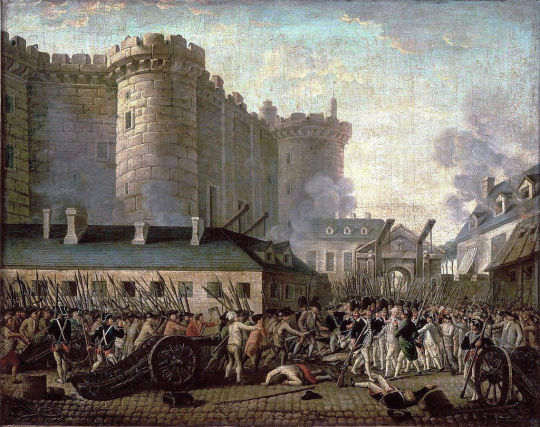

The Classical Era sees the French Revolution

Formation of colonies

The American Revolution

Aristocratic Society

All forms of medium come around full circle back to Greek and Roman philosophy.

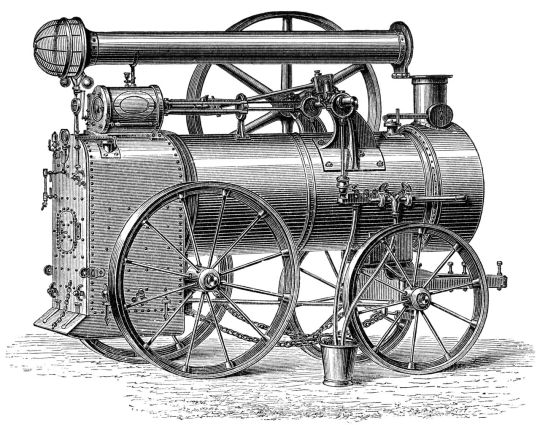

The Steam Engine is invented.

Benjamin Franklin discovers electricity

Oxygen is discovered

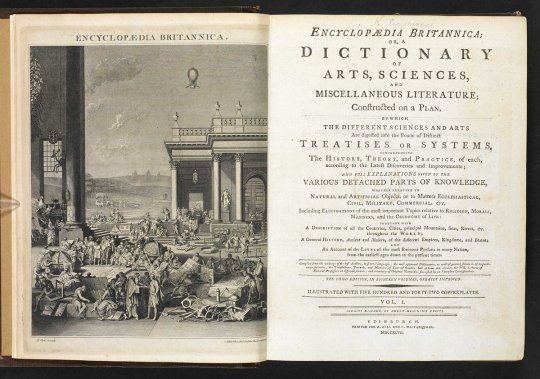

Encyclopedia Britannica is invented

Vienna becomes the cultural center for all mediums of art

The Sonata Allegro form develops into the most common form of orchestral composition. Containing 3 major sections: The Exposition (1st theme, bridge transition, 2nd theme in a new key and the closing section), The Development (variations on themes in different keys), and the Recapitulation (the return to the 1st theme, the bridge in the same key, 2nd theme same as the 1st theme, the closing section and the Coda ending).

Symphonies have 4 parts called movements. First Movement is the Andante/Adagio or theme and variation. Second Movement is the Allegro, Sonata - Allegro form. Third Movement is the 3/4 minuet dance. The Fourth Movement is the Allegro/Presto, Sonata Allegro form and has no exposition repeat.

Beethoven used 4 notes in his first symphony. He also incorporated tempo variations to add suspense and emotion. He created art for the sake of creating art with much longer Codas. This allows the music to be more expressive. He sometimes would write what was call Sherzo, a comedic evil dance. It was all in dark humor though.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mozart : Divertimento No. 14 in B-flat major, K. 270 -

II. Andantino

III. Menuetto & Trio

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Mozart - Published July 1, 2020

In the past, we’ve asked some of our favorite artists to choose the five or so minutes they would play to make their friends fall in love with classical music, the piano, opera and the cello.

Now we want to convince those same curious friends to love Mozart, whose mastery spanned genres and whose influence was profound. We hope you find lots here to discover and enjoy; leave your choices in the comments.

In the past, we’ve asked some of our favorite artists to choose the five or so minutes they would play to make their friends fall in love with classical music, the piano, opera and the cello.Now we want to convince those same curious friends to love Mozart, whose mastery spanned genres and whose influence was profound. We hope you find lots here to discover and enjoy; leave your choices in the comments.◆ ◆ ◆David Allen, Times critic So much of what I love about Mozart tends toward the poignant: his ability to express both the pain and beauty of the human condition, the way his music “smiles through the tears,” as the musicologist H.C. Robbins Landon put it. But he also offers moments of pure, unbridled joy, none more overwhelming than the finale of his “Posthorn” Serenade. It’s a reminder that Mozart, as the conductor Colin Davis once said, is “life itself.”

“Posthorn” Serenade Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic (Sony Classical) ◆ ◆ ◆Mark Hamill, actor I was in the first national tour of “Amadeus,” then I finished my run on Broadway. I did it for 11 months, the longest run I’ve ever had in a play. Beforehand, my wife and I went to Salzburg. You can tour Mozart’s house, and they even had a lock of his hair; it was a sort of reddish brown. That was chilling, hundreds of years later, to be so physically close to him.So much of the play is underscored with his music, which is more common to do in film. I never got tired of the sound; I could use it to inform my performance. And to underplay, because the music was doing a lot of the work. Particularly at the end, when he’s on his knees, wondering whether he’s really been so wicked. He’s so vulnerable, and his Requiem is playing.

Requiem Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon) ◆ ◆ ◆Condoleezza Rice, former secretary of state I have a long history with this concerto, having played a movement — and won with it — in competition at the age of 15. And when I was secretary of state, I had a chance to play a few lines from it on Mozart’s own piano at the festival in Vienna celebrating the 250th anniversary of his birth. Needless to say, the piece means a lot to me. The restlessness of the first movement, the simplicity of the second and the playfulness of the third are for me quintessential Mozart: genius. And Martha Argerich’s rendering is incomparable.

Piano Concerto No. 20 Claudio Abbado and Orchestra Mozart (Deutsche Grammophon) ◆ ◆ ◆Bernard Haitink, conductor Mozart didn’t write a note that isn’t worth hearing. But recently I watched the stream of Glyndebourne’s 2006 production of “Così Fan Tutte,” conducted by my wonderful colleague Ivan Fischer, and was reminded that the trio “Soave sia il vento” is one of the most sublime things I know. The text is “May the winds be gentle, and the sea calm,” and you can almost feel the breezes gently blowing and the waves lapping in the violins as it starts. Such beauty, tenderness and longing, all in the space of just over two and a half minutes.

“Così Fan Tutte” 2006 Glyndebourne Festival ◆ ◆ ◆Zachary Woolfe, Times classical music editor I love when Mozart swerves from the comic, just for a bit, and opens his heart. In “Le Nozze di Figaro,” an ensemble is burbling along when a few voices break out in soaring longing: Just let us get married. And here, in the Piano Concerto No. 25, the orchestra is cheerfully marching, the barest dusk over its bright spirits, when there’s a sudden burst and then an aria of aching loveliness: The cello gently warms the piano from beneath; the melody is passed to the oboe, then the flute. The ensemble is briefly gripped by tension before Mozart passes his magic wand over the music and merriment returns.

Piano Concerto No. 25 Mitsuko Uchida and the Cleveland Orchestra (Decca) ◆ ◆ ◆Ragnar Kjartansson, artist “Amadeus” made my childhood, and I have performed the forgiveness part of “The Marriage of Figaro” for 12 hours straight, twice. But this time I choose “Ave Verum Corpus.” It is just such a glorious short piece. It is the length of a pop song, but with the epic mass of sunrise. Just think of 35-year-old Mozart writing this in the summer of 1791, to thank his friend for setting his wife Constanze up at a resort while she was pregnant with their sixth child. He wrote it in the summer, then was dead in December. He was probably the ultimate “verum corpus”: I think few human bodies have brought as much joy to the world as Mozart.

“Ave Verum Corpus” Leonard Bernstein and the Bavarian Radio Choir (Deutsche Grammophon)

◆ ◆ ◆Tai Murray, violinist Despite being quite content as a violinist, the bassoon is my favorite instrument, and a major reason is this serenade. During the trio, the second bassoon operates as the bass of the group and is suspiciously late to everything; I cannot get enough. Fortunately, I don’t have to give up the violin to play it, because in 1787 Mozart composed the glaringly similar but still totally individual K. 406 String Quintet. He knew this piece was too good not to write it twice.

Serenade No. 12 Carion (Odradek Records) ◆ ◆ ◆Missy Mazzoli, composer The Act I finale of “The Magic Flute” has special resonance in these seemingly interminable days of quarantine. We watch our hero, Tamino, search for his lover, Pamina, after she has been kidnapped. At the door of a temple, Tamino sings “O endless night, when will you be gone? When will the daylight greet my sight?” and an unseen chorus whispers “Soon, soon, soon, fair youth — or never.” I love Mozart’s operas because they connect us not only to him but to all of humanity, reminding us that we suffer the same heartbreaks, giggle at the same dumb jokes and feel the same grief as audiences through the centuries.

“The Magic Flute” Ferenc Fricsay and the RIAS Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (Deutsche Grammophon) ◆ ◆ ◆Mitsuko Uchida, pianist There are so many moments. “Giovanni” has everything. “Figaro” is perfect. And “Così,” that is one piece I would take with me to a desert island: the duet for Fiordiligi and Ferrando, which I do not think is cynical music, and the trio “Soave sia il vento,” which brings tears to my eyes every time the strings start playing.But K. 545, the “Sonata Facile,” is one of the most amazing pieces, and I have always loved it. The slow movement is the twin of the aria “Dalla sua pace.” I play it as an encore when I want to say, “Sorry, my performance wasn’t good enough.” The whole thing blossoms, and out comes the truth. I played it for the Kurtags — Gyorgy and Marta, when she was still there. They lived the life of music, totally together. I went to see them just for the day, and when I arrived they wanted to hear Mozart. I played the “Sonata Facile.” I didn’t need to explain; they knew. Editors’ Picks 📷 The Songs That Get Us Through It📷 In a Starving World, Is Eating Well Unethical?📷 Again and Again, Literature Provides an Outlet for the Upended Lives of Refugees Piano Sonata No. 16 Mitsuko Uchida (Philips) ◆ ◆ ◆Seth Colter Walls, Times critic Modernist complexity and Classical-era transparency are often presumed to be at odds. But the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen’s bright, buoyant way of conducting this Mozart flute concerto puts the lie to that assumption. And in a cadenza he wrote, Stockhausen communicates affection for Mozart’s motifs — even when stretching phrase durations to lengths generally associated with the avant-garde. (This performance is on CD 39 of the Stockhausen edition available at stockhausencds.com.)

Flute Concerto No. 1 Kathinka Pasveer and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (Stockhausen Foundation for Music) ◆ ◆ ◆Anthony Tommasini, Times chief classical music critic Before Mozart, ensembles in operas were typically occasions for characters to summarize their feelings. Mozart turned them into action scenes, as in the beguiling sextet in Act III of “The Marriage of Figaro.” Figaro has just discovered that Marcellina, who has been angling to marry him, and the scheming Dr. Bartolo are actually his long-lost parents. A tender moment of reunion begins, while Count Almaviva, who is after Susanna, Figaro’s bride-to-be, mutters that he has been outwitted, a sentiment affirmed by his lawyer, Don Curzio. Susanna arrives, sees Figaro embracing Marcellina, assumes the worse, and stirs up the sextet with her fury.

“The Marriage of Figaro” Claudio Abbado and the Vienna Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon) ◆ ◆ ◆Jane Glover, conductor The scoring of this work, for 12 wind instruments and a double bass, is already extraordinary. But the slow movement is absolutely breathtaking. After four simple unison chords, a steadily pulsating, slightly syncopated accompanying figure in the lower instruments heralds the entry of the first of three solo lines: oboe, clarinet and basset horn, which share between them the most sublime melody. There is a feeling of infinite serenity in this music, of a quiet and radiant joy, and perhaps also a little shadow, so prevalent in Mozart’s music, which brings us to that fine edge between euphoria and sorrow.

“Gran Partita” Serenade Jane Glover and the London Mozart Players ◆ ◆ ◆Joshua Barone, Times critic Of all the things to love in Mozart’s music, I’m most often drawn to the economy of his emotional intensity. Not just in furious outbursts like the Queen of the Night’s famous aria. I’m talking about the leaner soloist entrances in his two minor-key piano concertos — whispered phrases of teeming drama. Or his Rondo in A minor (K. 511), a transparent masterpiece of keyboard writing that looks ahead to Schubert’s wistful lyricism and Chopin’s ornamented turns of phrase.

Rondo in A minorMitsuko Uchida (Philips)

◆ ◆ ◆Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim, Times critic The clarinet held a special place in Mozart’s heart. Inspired by Anton Stadler, an instrument maker and brilliant player, he wrote music for the instrument that was unprecedented in both its lyricism and jubilant virtuosity. One of these groundbreaking works is the quintet for clarinet and strings, which contains a slow movement of weightless, bittersweet perfection.In the beginning, the clarinet unspools long, placid lines over an undulating haze of strings, setting a mood of pastoral peace. Then a solo violin breaks free and engages the clarinet in a pas-de-deux full of playful runs and graceful ornaments. When the violin melts back into the background, the clarinet returns to its opening theme, the atmosphere now subtly changed and clouded with melancholy.

Clarinet Quintet Pacifica Quartet and Anthony McGill (Cedille Records) ◆ ◆ ◆Naomi André, author, ‘Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement’ A scene that has always made my heart stop and brought on the goose bumps is the finale of “The Marriage of Figaro.” The philandering Count Almaviva thinks that he has caught his wife cheating, only to realize that it is he who has been ensnared, in front of his whole household. With no escape, the count finally comprehends his shame and asks the countess for pardon. The magical moment comes when we all expect the countess to have her revenge, and she does just the opposite: She forgives him. She embodies the morality and strength that has been lacking throughout the opera. I love her being the bigger person.

“The Marriage of Figaro” René Jacobs and Concerto Köln (Harmonia Mundi) 🎼 ♪♫ 🗣♪♫🎹♪♫♪♫🎷♪🎻♪♫🎺♪♫🥁♪♫♪♫🎸♫♪

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/arts/music/classical-music-mozart.html

🎼 ♪♫ 🗣♪♫🎹♪♫♪♫🎷♪🎻♪♫🎺♪♫🥁♪♫♪♫🎸♫♪

15 songs, 1 hr 40 min

https://open.spotify.com/playlist

🎼 ♪♫ 🗣♪♫🎹♪♫♪♫🎷♪🎻♪♫🎺♪♫🥁♪♫♪♫🎸♫♪

1 note

·

View note

Text

Barocco Festival, "Sulla strada da Napoli e Vienna"

Barocco Festival, "Sulla strada da Napoli e Vienna" Il “Barocco Festival Leonardo Leo” supera i confini provinciali e venerdì 9 settembre, alle ore 21, approda a Lecce nella chiesa di Sant’Anna con il concerto “Sulla strada da Napoli a Vienna” del trio romano “Séikilos”. Intensi furono i rapporti culturali che unirono nel Settecento Napoli e Vienna, entrambe capitali di regni, poste culturalmente a confronto. Un vivace intreccio di scambi letterari e pittorici, oltre che teatrali e musicali, legò Napoli all’Austria raggiungendo l’apice nel periodo di Maria Carolina, regina di Napoli e figlia di Maria Teresa. Protagonista del programma il clarinetto barocco, proposto sui palcoscenici d’Europa dalle operose botteghe napoletane, che Vivaldi e Telemann conoscevano bene e utilizzarono in diversi lavori. Nei primi tre decenni del Settecento si compie a Napoli una svolta radicale nella cultura, nel gusto e nelle arti. Un mutamento che ha origine nel ribaltamento istituzionale che si verifica a partire dal 1707, quando alla dominazione spagnola subentra quella austriaca, relativamente più libera e progressista. Quando nel 1734 termina il dominio austriaco e viene creato un regno autonomo sotto la guida illuminata di Carlo III di Borbone, si accelera il ritmo del cambiamento e Napoli diventa uno dei centri culturali più importanti del continente europeo, dove si affermano riforme amministrative ed economiche di segno spiccatamente antifeudale e anticuriale. Un analogo fervore investe anche l’arte, nella quale si recuperano nuovi contenuti che si riallacciano alla ricca letteratura dialettale seicentesca, in grado di generare una svolta salutare anche in campo musicale. La musica cessa così di essere appannaggio di una cerchia chiusa e ristretta, aprendosi a una più ampia fruizione. Lo attesta il rapido sorgere di nuovi teatri che, se da un lato soddisfano l’esigenza di uno spazio scenico nel quale il sovrano possa celebrare se stesso e la sua corte, come il San Carlo di Napoli, dall’altro con luoghi di minor fasto e prestigio, come il Teatro dei Fiorentini, il Teatro Nuovo o il Teatro della Pace, vengono incontro alla passione sempre più dilagante per la commedia per musica, che può considerarsi il simbolo di una nuova visione estetica in cui si condensano e sintetizzano le nuove istanze culturali. Non ci sono soltanto strade, autostrade, rotaie che uniscono l’Italia all’Austria. Un canale speciale di comunicazione è quello culturale, prova ne è lo stato di forte contaminazione tra i linguaggi d’arte dei due Paesi. Una strada è offerta dalla musica, la cui tensione supera persino le barriere linguistiche e può essere compresa senza difficoltà da una parte e dall’altra del confine. Prima della straordinaria fioritura artistica poi mitizzata nel termine “classicismo”, Vienna era ancora “provincia italiana”: sotto Ferdinando II la maggior parte dei musicisti della Hofmusikkapelle proveniva dall’Italia. La banda di corte fiorì sotto i successivi imperatori fino al 1740 circa, finché Maria Teresa e Giuseppe II decisero di limitarne l’uso alla musica sacra, e Antonio Salieri, che insegnò a Beethoven, fu l’ultimo direttore di corte italiano. Nell’ultimo trentennio del Settecento il ruolo dell’Italia come fulcro dell’Europa musicale si avviò al declino contestualmente all’ascesa della triade viennese - Haydn, Mozart e Beethoven - che non era isolata ma rappresentava la punta più avanzata di molteplici esperienze musicali e di un’intera generazione di autori, in parte provenienti dalla cosiddetta scuola di Mannheim, in parte attivi come pianisti e compositori nella capitale austriaca. L’attivismo frenetico della Vienna della seconda metà del Settecento si specchiava nella disponibilità dei mecenati e nell’intensa presenza esecutiva dei concerti pubblici, in particolare di quelli organizzati nel periodo di Natale. I biglietti sono disponibili nel luogo del concerto. Ticket euro 3 - Info T. 347 060 4118. Per ulteriori informazioni VISITA IL SITO.... Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Joseph HAYDN (1732-1809)

Joseph Haydn wore the livery uniform of a court servant for most of his career, composing and performing to order. When he was eventually granted a measure of freedom, he became one of the first composers to write for a mass audience. The result was adulation, and it was richly deserved. Almost single-handedly, Haydn established the formats on which classical music would be based for more than a century.

[ Yazının Türkçe Çevirisi ]

Two titles are regularly bestowed upon him: 'Father of the Symphony' and 'Father of the String Quartet'. But his influence was equally important on the concerto, the piano sonata and the piano trio. Haydn was a wheelwright's son and a natural self-improver. Not only did he make every effort to learn and perfect his musical craftsmanship, he acquired the social skills to be welcome in any company. But he did have to learn those skills.

He spent nine years as a chorister at St Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna until he was suddenly ejected and left homeless and without income. His voice had broken, but cutting off the pigtail of another choirboy had hastened his exit. He survived through busking and teaching. He was briefly employed in Vienna with the Italian opera composer Porpora and a Bohemian nobleman, Count Morzin, but real financial security did not come until 1761.

From then and for the next 30 years, Haydn was an employee of the Esterházy family. Haydn's first years of composing for the Esterházy family have been called his period of Sturm und Drang ('storm and stress'). It is an apt description of music that was highly dramatic, musically adventurousness and emotionally unrestrained. However, it was soon replaced by a more characteristic steadiness and civility.

As his Hungarian employers moved between their winter and summer palaces, Haydn followed. He was in effect a servant and his duties were considerable. They included running the orchestra, composing to entertain the court and its guests and presiding over the chapel choir and musicians. For good measure, he also had to produce a few new operas.

By the standards of the time the Esterházy princes were benevolent masters. They appreciated Haydn's genius and found him easy to get on with. That genius is best illustrated by his symphonies, of which he wrote 104. Haydn wasn't the first symphonist, but he was the one who established the genre's definitive four-movement design. He also gave sonata form the proportions that saw it become the musical foundation of both Classical and Romantic eras.

The features of Haydn's symphonies are mirrored in most of the other genres in which he wrote. And yet they are not short of innovation. Touches of folk music are often present. His third-movement minuets frequently mix the courtliness of the formal dance with more rustic tones. His finales are notable for their jocularity. Haydn's humour is less arcane than Mozart's and less aggressive than Beethoven's. Perfectly timed and always appropriate, his musical wit reveals much of his personality.

By the mid-1770s his fame was spreading, partly because of the newly developing infrastructure of music publishing. Commissions began to come from outside the Esterházy court, and Haydn's employers allowed him to take them on. His chamber music sold well. The 1781 publication of the six string quartets op.33 marked a significant new phase, both in Haydn's career and in the establishment of the genre. The quartets show an ideal combination of intimate detail and sweeping total effect.

Until recently Haydn's concertos, piano trios and piano sonatas were neglected but recordings have revealed their considerable worth. His operas may one day be similarly re-evaluated, though for all their attractiveness they suffer from comparison to Mozart's psychologically perceptive inventions. The oratorios remain perennially popular. The Creation (1798) and The Seasons (1801) date from Haydn's return to Vienna after two triumphant visits to London. There he had been inspired by hearing Handel's oratorios.

Eventually releasing him from court duties, the Esterházys allowed Haydn two visits to England (1791-92 and 1794-95). There he conducted new symphonies in subscription concerts organised by the entrepreneur Johann Peter Salomon. By now he was composing on a grand scale, giving starring roles to wind and brass and allowing slow introductions to his first movements.

The wheelwright's son who had charmed court circles had mastered the art of writing for a large and diverse public. He was adored in London and feted in Vienna when he returned for his final few years. Such was his international reputation that Napoleon, whose forces were attacking the Austrian capital as Haydn lay dying, placed an armed guard around the composer's house.

Source: Sinfini Music

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

LEIF OVE ANDSNES

MOZART MOMENTUM 1785

Nuevo álbum hoy disponible. Además, el primer vídeo de la serie de vídeos Mozart Momentum "Piano Land Vienna" en SONY CLASSICAL YOUTUBE. Conoce a Mozart en Viena y descubre cómo el compositor tuvo que ser cada vez más inventivo para distinguirse y ganarse el cariño del público.

Consigue el álbum AQUÍ

Mira el vídeo AQUÍ

"Cuando te das cuenta de lo rápido que Mozart evolucionó durante los primeros años de la década de 1780, te preguntas: ¿cómo ha ocurrido? ¿Qué estaba pasando? Su creatividad se dispara en ese momento", dice Leif Ove Andsnes.

En 1781, con 25 años, Mozart se atrevió a ir por libre: "¡Viena es la tierra del piano!" exclamó en una carta a su padre, Leopold, en un intento por justificar la renuncia a su empleo del arzobispo de Salzburgo. Con conciertos diarios en lugares públicos o privados, Viena era el lugar perfecto para el ambicioso joven compositor y músico, que rápidamente se dio cuenta de las oportunidades que le ofrecía la ciudad. Un par de años más tarde ya era uno de los músicos más famosos de Viena, pero hacia 1785 apareció la competencia. Según llegaban más y más compositores talentosos a la ciudad, los independientes como Mozart tenían que ser más creativos para distinguirse y ganarse la atención del público. Fue en estos dos años --1785 y 1786-- que la imaginación musical de Mozart floreció como nunca antes.

Mozart escribió una serie de obras maestras y revolucionó la esencia del concierto de piano. Los cinco conciertos de piano, Nos. 20-24, son piezas fundamentales en el cambio de la forma. Mozart comenzó a reexaminar los papeles del solista y la orquesta y creó un diálogo entre estas dos entidades de una forma totalmente nueva. "Cambia completamente con el Concierto de Piano No.20 de Mozart [en re menor K466]," dice Andsnes. "Separa más al solista de la orquesta. La primera entrada del solista en esta pieza es diferente a lo que has escuchado presentar a la orquesta. Este es el momento que apunta al futuro y la evolución del concierto de piano y del comienzo del concierto de piano romántico, que es tan apreciado. Todo desde Tchaikovsky, Grieg y Rachmaninov, donde el solista tiene una especie de papel "heróico." Empieza aquí con Mozart."

En los cuatro trabajos siguientes, Mozart exploró exhaustivamente la forma del concierto y llevó a sus seguidores vieneses hasta el limite de la emoción. "Había una nueva energía creativa en el aire," dice Andsnes: "Mozart parece haberse adentrado cada vez más en el lenguaje y sus posibilidades e intentó nuevas técnicas. "No conozco otra música que ofrezca tanta diversidad emocional."

Mozart Momentum 1785 es el primero de dos lanzamientos que exploran estos años especialmente destacables. Incluye los conciertos de piano Nos. 20-22, el Cuarteto de piano en sol menor, Música para un funeral másónico y Fantasía en do menor para piano solista.

"La idea de este proyecto es explorar la diversidad de lo que estaba pasando en la vida creativa de Mozart en ese momento; mostrar que una separación entre la interpretación solista, la interpretación de música de cámara, y la de concierto, no es realmente importante," dice Andsnes. "Te das cuenta de que algunas partes de piano en la música de cámara son de más virtuosismo que aquellas de los conciertos. Todo va de la mano."

Leiv Ove Andsnes se embarcará en esta nueva aventura junto a una compañera de confianza: La Orquesta de Cámara Mahler. Su proyecto anterior de conciertos --los cinco conciertos de piano de Beethoven-- incluye grabaciones que ganaron el premio al Disco del año de BBC Music Magazine, fueron nominadas a los Premios Gramphone y fueron aclamadas como nuevos estándares de referencia. "Esta colaboración es mucho más que una interpretación excepcional; hay una sensación palpable de descubrimiento, de experimentación de la música," dice Gramophone Magazine. The Guardian dijo: "Es difícil encontrar un pianista y una orquesta que se acoplen mejor."

El segundo álbum doble, que se centra en el año 1786, incluirá los conciertos No.23-24 de Mozart, el Cuarteto de piano en mi bemol, el Trío para piano en sol menor y Rondo en re para piano solista. El proyecto Momentum Mozart también viene acompañado de giras de conciertos por toda Europa.

REPERTOIRE

ALBUM 1 - 1785

Piano Concerto No. 20 K 466 Piano Concerto No. 21 K 467 Piano Concerto No. 22 K 482 Masonic Funeral Music Fantasia for Piano in C minor Quartet in G minor for Piano and Strings

ALBUM 2 – 1786 Fall 2021

Rondo in D for Keyboard

Concerto in A for Piano, No. 23

Concerto in C minor for Piano, No. 24

Quartet for Piano and strings in E flat ��

Piano Trio No 2 in G

Scena and Rondo for Soprano “Ch’io mi scordi di te?”

youtube

0 notes