#what with the opposed orthography

Text

I saw a comment on the Fallen London wiki, where someone wondered whether it would be possible to "actually" revive/fix Mr Candles, as opposed to SMEN's mission to the High Wilderness which (as far as I can tell, having never Knocked myself) settles for mourning or avenging him.

My reaction was "well, this is the Neath, and the whole point of the Neath is to be a refuge for the audacious and the impossible, right? So there should be some way to do it, even if it's not in the game."

But then that got me thinking... how would you do it, exactly?

Part One: Body

First off, the requirements to revive the dead, even in the Neath, are apparently pretty heavy. Cups manages it at the end of Nemesis, with a ritual requiring Master's Blood, a bathtub full of Hesperidian Cider, a number of specially-prepared candles, and the remains of the deceased.

Of these four, the first two are obtainable in-game. Eye-wateringly expensive (fun fact: a bathtub is seven firkins), but still.

The third is also obtainable... at a cost. There's probably a reason that the Seeking Road, despite being as misaimed as it is, tries to spell Mr Candles's name in candles.

The fourth... well. SMEN ignores it, except at the very beginning. But the physical remains of Mr Candles apparently still exist. "IT IS NORTH UNDER GRANITE." Probably in Xibalba.

But there's a problem with the Cups Process: it can't restore the mind. In Nemesis, this was an unfixable problem. But for Mr Candles... its mind survives, and we know where to get it.

Part Two: Mind

The Mr Eaten of SMEN vascillates between two agendas: revenge and grief. Why? My theory is that there are two Mr Eatens in the Neath, each an incomplete remnant of the original Mr Candles. We know that one of them is imprinted in the lacre of the Bazaar. That would be the grieving one; aside from the obvious practicalities of what can and can't be described in the language of grief, we know that when you "Accept the Name" from the Eaten Mr Sacks, your Question is immediately shifted to "What is Forgotten" even if you previously set it to "What is Due".

Then where is the Mr Eaten of revenge? Well, where was Mr Candles most likely to leave a part of itself behind? I think the obvious answer is Parabola. It's a place where even the Masters are vulnerable, and if some impression of him didn't remain there, then we wouldn't have dreams of Death by Water. But this Eaten has been warped, too. The Strange Dreams of London interact with each other, after all, and none more than those of Storm. Storm is the other dream-remnant who dreams of going NORTH, and has his own reasons to want to pass the gate of Avid Horizon and bring down a reckoning upon the whole Neath and its lawlessness. When the Bag a Legend protagonist crafts the hungry knife to kill Mr Veils in retribution, they even use Storm's thunderbolt to do it. Some part of Storm has rubbed off on the Parabolan Mr Eaten, I think, and caused it to hyperfixate on the plan of revenge at any cost.

Part Three: Putting the Pieces Together

So now we've found the disembodied mind that the Cups Process cannot, on its own, rebuild. But how do we safely reunite those minds with their body?

If the grieving remnant is imprinted in lacre, then it can be read out of lacre. It's Correspondence, albeit a different dialect written with a different orthography. A sufficiently dedicated Correspondent could "accept the heart and lights" of the Eaten Mr Sacks and then transcribe them. And if there is a concern that "lacre cannot bury the law", then perhaps they should get the help of a Steward, whose whole craft centers around burying the Law, to enact that "no forgotten victim shall be forgotten" while the work gets done.

As for Parabola's Mr Eaten, well, the protagonist has successfully visited the dreams of dead Masters before. Get someone good enough at Glasswork to find the center of the dream. Speak the Name, to grab the attention of the dreamer, and then transport it in a Mirrorcatch Box; the endgame quests of Sunless Sea have shown us that this is a convenient way to contain and transport Parabolans who could not survive in the Neath.

With this, all that remains is to transfer these thoughts into the newly resuccitated Mr Candles. Irrigo is the obvious tool for this; we know that it can lubricate thoughts and memories, allowing them to flow freely from one person to another.

But using the Nadir itself for this purpose would be too dangerous. We'd risk permanently losing the precious canoptic jars which we'd worked so hard to recover. Instead, we need someone skilled with precision application of irrigo, of the "inks of undernight", to perform the transplant. We need Millicent Clathermont's remnant... whom, if we have St Eruzile's Candle, should already be present within us.

And what about the most fundamental obstacle? The notion, put forward by the authors themselves, that there is no longer such things as a Mr Candles, just an absence where a Mr Candles should be?

The Seeking Road has given us the solution to that, as well. The process for filling that void appears every time someone finishes St Gawain's service. St Gawain's Candle is, above all else, an emptiness in the shape of a person, filled with glory and coaxed back to life.

Perhaps it's presence as the final candle of the Seekers is no coincidence either.

In Conclusion

So this is the shopping list.

Mr Requiem, transcribed from lacre into Correspondence

Mr Reckoning, contained in a Mirrorcatch Box by Glasswork

The Inks of the Undernight, and a skilled hand at them, to return the two remnants of Mr Candles's mind to its body

The blood of a living Curator, for the Cups Process

Seven firkins of Hesperidian Cider (or another highly concentrated medium of the Mountain of Light's vitality) for the Cups Process

A number of specially-prepared candles, for the Cups Process

The physical remains of Mr Candles, NORTH UNDER GRANITE

Much of this is familiar. Much of this is stuff that SMEN gives you, for reasons it never deigns to explain before it sends you off to Avid Horizon to ruin everything.

Perhaps this was always the plan, originally. Perhaps Mr Candles, forseeing (as Winking Isle implies) the betrayal, prepared the Seeking Road as a means of resurrection, and it only got bent out of shape later. Perhaps by some ineffective Tragedy Procedure which smudged the Seeking Road but failed to erase it, or perhaps by some Mithridatic scheme of Nicator (who entire stake in the matter, as a player for White, is by his own admission “to bring light to the Neath”), or perhaps just by the Eatens’ tug-of-war between revenge and regret accidentally yanking the path past Xibalba and through the Gate.

It'll probably never be a part of the game. But in the realm of fanfic... the realm of "what might be possible"... who knows?

#fallen london#mr candles#mr eaten#seeking mr eaten's name#smen#speculah#original content#fallen london spoilers#chandlerbat100

209 notes

·

View notes

Note

And another question re: Gaelic post…can you talk more about Scots, and how it came to be seen as the more “educated” language compared to Gaelic, as well as how the language is viewed now?

Barrie quaisten!

SCOTS

Scots is another Anglic language closely related to English. There is heated debate (often, unfortunately, along political party lines) over whether it should be considered a language or a dialect. However, the linguistic consensus is that Scots is indeed its own distinct language, complete with its own vocabulary, grammar rules, and historical character. It's akin to the relationship between Danish and Norwegian - while they share a relatively recent common ancestor and have influenced each other over the course of history (however lop-sided that influence may be), they are indeed separate languages.

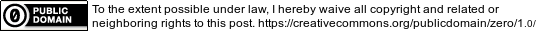

Around the 600s CE, a new language appeared in the southeast corner of Scotland, back when this area was under the control of certain new-ish arrivals to the island who spoke a Germanic tongue. At this point, Middle Irish (modern Gaelic's immediate ancestor) was the court language of Scotland, and would remain so until the reign of David I, crowned in 1124. Scots is said to have begun diverging from the Northumbrian Old English dialect in earnest by the 1100s, although records of the language are sparse before about 1375 (the beginning of the Early Scots literary period) owing to Viking and English "meddling" (some light raiding here, some plundering there, general theft, and so on). Owing to its Northumbrian origin and heavier Scandinavian influence (stemming from close ties with the Danelaw), Scots has more of an Anglian and Norse character to it as opposed to its relatively more Saxon-y, Norman-y cousin to the south (i.e., English). Scots has also had much closer contact with languages like Scottish Gaelic and even Pictish and Cumbric (which I'll be sure to cover in a future post), and as a result has been influenced in its vocabulary and phonology.

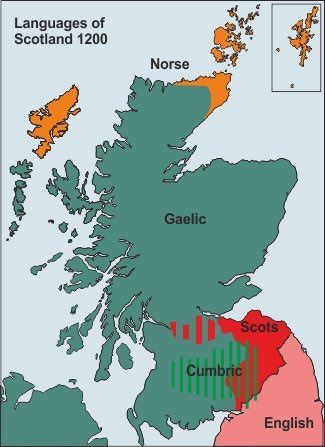

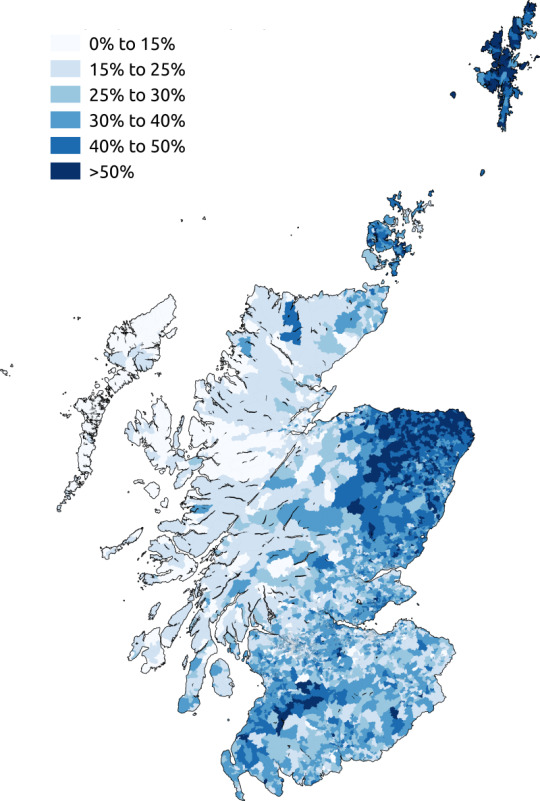

It has several dialects of its own, broadly categorized by location, ranging from Borders Scots to Orcadian Scots and everything in between. (And we can't forget Ulster Scots, a dialect brought to Ulster during the 1600s by Lowlander planters.) Due to this variation, modern Scots has no clear standardized form, though linguists have made several halfway-serious attempts over the past century or so to standardize orthography.

But what's been going on with Scots between David I and the present day? Let's dig in.

David I (in Gaelic, Daibhidh I mac Mhaoil Chaluim), who reigned from 1124 to 1153, initiated the proliferation of proto-urban societies across his kingdom. These societies were called "burghs", or "touns" in Scots, and they'll come in handy later. At about this same time, Norman French began to infiltrate the Scottish nobility, and Gaelic began to decline as a language of prestige among higher levels of society.

Once the 1200s started to creep around, the northern dialect of Early Middle English that would become Scots began expanding ever northward towards the Forth-Clyde line. This dialect was called "Inglis" by its speakers, and over the next century, it began to supplant Norman French and Gaelic as a common language within the burghs. The 1300s saw this "Inglis" tongue grow in prestige and it began to eclipse Norman French at even the higher levels of society, particularly within the courts. As the 1400s approached, it even began to replace Latin as the language of ecclesiastical and royal court proceedings.

The 1400s saw a relatively rapid geographic spread of Scots at the expense of Gaelic, which was cornered into the Highlands, Western Isles, and small pockets in the Lowlands (viz. Galloway, where Gaelic survived at least up to 1760). By the early 1500s, Scots began to be known as "Scottis", and Gaelic, which had previously been referred to thus, was now being dubbed "Erse" ("Irish") in attempts to otherize Gaelic. The 1500s saw the advent of Middle Scots, which was, in my amateur opinion, the golden era of the language, owing to its undisputed support at all levels of society across most of the kingdom. Around this time, a loose written standard did exist, but the language was still written how it sounded and regional variation was commonplace.

1567, however, saw the coronation of James VI of Scotland (note: James I of England and Ireland as well from 1603 on). His famous Bible translation (KJV) helped to set in motion the gradual Anglicization of Scottish society as it was dispersed among the population. In 1603, the Union of the Crowns brought Scots-speaking and English-speaking nobles into closer contact, and English gradually began to dominate the speech of the Scottish nobility (this exchange would produce what is now Scottish English, a distinct standardized dialect of English that some argue is one end of a linguistic spectrum, at the other end being "braid Scots").

Beginning in 1610 and continuing through to the 1690s, Scottish planters from across the western Lowlands and the Borders began to settle in Ulster, the northeastern region of Ireland. Over time, this group of people would come to develop their own regional identity, the Ulster Scots (or, often in a New World context, Scots-Irish). Their local dialect of Scots, while maintaining a Lowland character, picked up various influences from Hiberno-English (particularly in phonology) and from the Irish language (various contributions of vocabulary).

By about 1700, written Scots, at least in an official capacity, had become almost completely Anglicized. An example of an Anglicized convention introduced to Scots writing is the "apologetic apostrophe", an apostrophe that was inserted into a Scots word where an English-speaking person might expect a letter to be (for example, the Scots word "wi" (in English, "with") would have been written wi'). In 1707, the Acts of Union (Note: Panama played a role) seemed to solidify a shift in the upper-class opinion of the Scots language - what scarcely 150 years before was seen as the national language was now looked down upon by the nobility as "uneducated speech" or "bad English".

However, things looked different from a lower- and middle-class perspective. Contrary to high society, the common people began to take a renewed interest in the Scots language, and a literary revival began. This mid-1700s revival gave us such world-famous names as Robert Burns, Walter Scott, and Thomas Campbell. It was at this time that Scots transitioned from Middle to Modern Scots. However, features such as the apologetic apostrophe were retained during this period to gain wider readership among an English-speaking audience, a market that now effectively spanned the globe. (Meanwhile, the Highlands and Lowlands each experienced their own set of Clearances, and Scotland's diaspora began their journey to the edges of the empire.)

By the early 1800s, this "Scots fever" (NOTE: not a technical term) had reached the upper classes of society as they increasingly turned a Romanticist eye to the literature of their homeland, while simultaneously keeping Gaelic at arm's length. Since this point, there hasn't been any sort of top-level, government-sanctioned, institutional spelling reform or rulebook published on Scots orthography, although this hasn't stopped a wealth of Scots poetry and prose from being published through the years.

Since this era, there has been a relatively steady stream of interest in the language, though recent government initiatives have been taken to attempt to ensure the survival of, and increase interest in, Scots. This 2010 study by the Scottish Government sheds some light on modern public perception of the language within Scotland itself.

Over in Northern Ireland, the Ulster-Scots Agency was established as part of the wider Belfast Agreement of 1998 in efforts to promote the language and wider culture.

It's not all roses these days, however. A couple of years ago, it came to light that a North Carolina teenager had been, for over seven years, writing entries on the Scots Wikipedia, without any knowledge of the language. One Reddit user remarked that this teenager had caused "more damage to the Scots language than anyone else in history." (Perhaps take this with a grain of salt.)

Would you like to help protect the language?

The best way to protect a language is to learn it! If you click that link, there are several resources for adult learners of Scots to start their journey. My perennial advice, though: once you've got the basics down, use it! Find a Scots speaker and stumble your way through a conversation. Don't be afraid of making mistakes! (Note: everyone makes them.) One resource I've used in the past to learn some basics is the Open University's (entirely free!) Scots language and culture online course. All you need to do is sign up and work through the modules!

Follow for more linguistics and share this post! If you have any questions, feel free to ask!

#scots#scotland#germanic#language#languages#learning languages#langblog#langblr#indo european#united kingdom#ireland#northern ireland#ulster

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey uhh..... advent denest!! this is just the first chapter, every day from now until christmas there will be a new one featuring a christmassy/wintery prompt for that day, but I won’t bother you with that here--check out the ao3 link! :D (maybe I’ll get some other chapters on here too, just to remind everyone, but I’ll think about that)

--

Snowfall Music

pairings/characters: Denmark (Søren)/Estonia (Eduard), mentioned Finland (Tuomi)/Sweden (Torbjörn), Sealand (Peter), Ladonia (Lars), Vietnam (Vinh), Czechia (Kveta)

word count: 4782

summary:

Eduard has enough to occupy him this December without having to look after his young cousins, or trying to organize events on his radio show, or having to field strange phone calls day after day, but it seems the end of the year has it out for him.

And somehow, Søren manages to brighten every dark day. Hopefully, he'll stick around for a while.

also on AO3 - further chapters posted there!

--

“Today on Radio 8, I have some pretty special guests on the show. Now, this was a surprise for me as well—” Eduard opens the audio channels of two of the other microphones in the studio— “but I’m excited they’re here, so welcome to my cousins, Pete—”

“Once removed,” Lars interrupts, raising his eyebrows and wrinkling his freckled nose as if he thinks Eduard is a bit dim. He probably does, come to think of it. The boy is just at that age.

“Alright,” he amends anyway, “my first cousins once removed, Peter and Lars. They’re my first cousin Tuomi’s sons. Is that better?”

“Yes,” Lars replies imperiously. Peter is rolling his eyes, and Eduard has to stifle a laugh while he turns on some background music.

“Their parents are on a trip out of town for the week, so Peter and Lars have been entrusted to Uncle Eduard for the time being—first cousin once removed Eduard, I know, Lars, but I’ll start saying that when you start calling me that.”

“I will.”

“I don’t doubt it. Why don’t you two introduce yourselves, and then you can think of a song you’d like to hear.” He prays Tuomi hasn’t managed to instill too much of his taste in music in his sons just yet, because although they’re ostensibly a rock station, he doesn’t think his listeners are quite ready for metal that heavy.

“I’m Peter,” Peter all but shouts into his microphone, so Eduard lowers his volume slightly. “I’m twelve, and I, ah, I play hockey, I guess?”

That sounds about right.

“And Lars?”

“Well, I’m Lars, I’m also twelve, and I have a podcast.”

“A podcast, really? What’s it about?”

“School and things,” he replies, and nothing else.

“That’s great,” Eduard enthuses anyway, because he does think it is. “You must be excited to visit the studio, then. Would you like to work in radio someday?”

Peter is shaking his head quite frantically and making slashing motions with both hands, but the damage is done, as Lars huffs, wrinkling his nose again and leaning in close to the microphone.

“Radio is very different from podcasts. You just talk around the music.”

Eduard blinks. “I’m going to take that as a compliment.”

“It wasn’t.”

Eduard looks helplessly over at his production assistant, who seems uncharacteristically amused by the whole exchange, her eyebrows twitching ever so slightly.

“Where did you get that sass from?” He knows it must be Tuomi, unless his husband, Torbjörn, has very deeply hidden depths. And, before Lars can actually reply, “Peter, what should we listen to? What music do you like?”

Lars is opening his mouth, but Peter forestalls him, yelling, “Imagine Dragons!”

So Eduard starts a jingle as he lines up an Imagine Dragons song from the station’s playlist and an older rock song to play after that, pushing the slides for the microphone channels down. When he looks at Lars, the boy is just glancing away, attempting to seem disinterested in everything going on by crossing his arms and pressing his lips together. Eduard shakes his head fondly as he scrolls through some of the messages people have sent the show, including some asking if his cousins will help him judge his weekly dumbest pun contest, which he doesn’t imagine will benefit the already low bar for that one, so that’s perfect.

When he asks the boys about it, Lars starts to say something undoubtedly disparaging about how his podcast never has puns, but Peter quickly interrupts again. Eduard is around them enough that he knows this has been their usual behavior for the past few years, and more often than not, the brothers remind him strongly of himself and Tuomi at their age. They always were more like siblings than cousins, and when their older cousin Erzsébet was asked to babysit, she never seemed inclined to stop them.

Granted, he wasn’t doing podcasts when he was twelve, but he does remember using the house phone to call the local radio station multiple times until his parents started threatening to take the phone bill out of his allowance, and then how was he going to buy CDs? The radio show hosts actually wondered what happened to him after a couple of days without word and his parents had to call in to explain. It’s a fond if embarrassing memory.

The show continues in a slightly messier fashion than usual, mostly due to Peter’s attempts to interrupt every single sentence his brother starts to say and Lars stubbornly talking over him, but it’s fun. Eduard reminds himself to make a compilation or something to give Tuomi and Torbjörn when they get back home.

He lets Lars pick a song as well, as his afternoon show nears the end of its first hour. While the mildly surprising requested obscure progressive rock plays, he becomes aware of movement out of the corner of his eye.

Turning, Eduard huffs a laugh when he spots the sheepish-looking freckled face peering through the studio’s windowed door.

“Boys,” he says, ignoring that Lars just glares at him for daring to interrupt his very intent listening, “looks like your uncle finally showed up.”

Peter’s face lights up when he sees the man on the other side of the door, waving enthusiastically. Søren waves back, face splitting in a grin. Although he is Torbjörn’s brother and not a cousin, he doesn’t bear much more resemblance to his brother than Eduard does to Tuomi. He’s tall, but not as tall as Torbjörn is—or Eduard, for that matter—and his eyes are a darker blue pronounced by nearly-black eyebrows that don’t match his coppery hair at all. Eduard has always thought of him as not handsome necessarily, but definitely interesting, and he’d be lying if he said he minded having to look after his cousins with the man.

They’re not close, but he and Søren have spent some time together, albeit mostly when Tuomi and Torbjörn needed someone to look after their sons for a while.

Now, Peter is moving his hands in a flurry of signals Eduard can’t make much of, except that he points at him at the end, and Søren is quickly signing back, his eyebrows jumping wildly.

“He can come in, you know,” Eduard tells Peter, slightly bewildered. He ignores the annoyed look his production assistant is giving her soundboard. At least, he thinks it’s annoyed. It can be hard to tell, with Vinh.

Peter dashes to the door to let in his uncle, who ruffles the boy’s unruly blond hair, waves at Lars—who ignores him—and grins at Eduard with a sheepish edge to it.

“Hey,” he says, “thanks so much for looking after ‘em! Sorry I couldn’t get there in time. Hope they didn’t cause too much trouble for you.”

“Lars is having loads of fun,” Peter declares, then proceeds to duck out of the way when Lars throws a wad of paper at his head. Eduard shrugs at Søren.

As Lars’s song ends, a commercial break begins, and Vinh wanders away to grab some tea and probably gossip about him with the other hosts, so Eduard puts his headphones down and turns his attention fully to Søren. The man is dressed in the same leather jacket he always seems to be wearing and a T-shirt, but doesn’t appear to be cold in the slightest. He has stuck both hands into the pockets of his jacket, but he still moves them wildly when he speaks. A backpack is slung over one shoulder.

“Thanks again. I really couldn’t get out of work, so I’m glad you could take the boys to yours.”

“Of course, no problem.” Eduard pushes his glasses up. “We did have fun, right, boys?”

Predictably, the response is lackluster, since Peter and Lars are too busy swatting at each other with Eduard’s papers.

“I promise we did,” he tells Søren a little forlornly, receiving a full laugh in response, blue eyes glittering in the studio’s bright lights and crinkling up at the corners.

“One day, they’ll learn to appreciate us, Eduard.”

The dubious expression he pulls in return must be funnier than he imagined, because Søren laughs again, extracting a hand from his jacket to clasp his shoulder. He smells pleasantly like the winter air outside, and like hair gel.

“I aspire to help ‘em keep as many secrets from their parents as possible, so they’ll be forever in my debt.”

“You have to wonder if that’s worth incurring Tuomi’s wrath.” Eduard turns back to his soundboard and patches the newsreader in from another location.

“I can take Tuomi.”

“I think that’s your brother’s job.”

Søren makes a strangled sound that might be a laugh and that makes Eduard grin, shaking his head.

“Are you staying for a while? The boys have a pun contest to judge, and I’m sure my listeners would like to hear from you.”

“Sure, sounds great,” he says, his grin softening surprisingly. “I just gotta ask you to keep the background music to a minimum, if you can.” He gestures vaguely at his ear, and Eduard remembers something.

“Right, you don’t hear so well, do you?”

“Practically deaf without my hearing aids, kind of a bummer when you’re on a radio show, I imagine.” He smiles, his eyes crinkling up.

“That’s why pa taught us sign language,” Peter pipes up. “Dad is so bad at it. Uncle Søren, I’d like it if you stayed.”

“Sign language,” Eduard repeats, because of course that’s what that was, but also, how has he never realized that before now? He’s more-or-less known Søren for over fifteen years by now. “Well, I’ll watch the music. Let me know if it still bothers you.”

Vinh returns just as the short second commercial break is ending, inclines her head towards Søren, who waves and does not seem the least perturbed by her lack of outward response, and they set off on the second hour of the show. Eduard lowers the volume of the background music to nearly zero, gesturing at Vinh to leave it.

“While we were away, my first cousins’ once removed actual uncle finally showed up, after he promised he’d pick his nephews up from school—”

“Hey,” Søren interrupts, “you’re painting me in a bad light here, and I don’t appreciate it.”

“It’s the light of truth.”

Astonishingly, Lars snickers at that. He apparently doesn’t care who gets made fun of as long as it’s not him.

“Well, he’s here now, so hello, Søren. He works for the same company my cousin does, so… Is it your fault that we’re saddled with these kids now?”

“Well, I did introduce their parents to each other, so I suppose…” Søren winks at Peter, who sticks his tongue out. “Hey, Eduard, I hear these two got to pick a song to listen to. Do I get a go at that?”

Eduard laughs. “No, no. You need to do a better job of picking them up from school for that. Maybe next time. Actually, I think we’re overdue for some Christmas music. It’s December, after all!”

Peter crows triumphantly. Søren just grins, shaking his head at Eduard, who shrugs in turn, amused.

The hour goes by fairly quickly. Søren animatedly asks the boys questions about their school day during songs that even Lars answers sometimes, and Vinh doesn’t seem to mind him, which is high honor.

By the time the host of the early evening show has arrived and is setting up her stuff while the last song of Eduard’s show plays, he has received quite some messages asking if his cousins or their uncle, who, according to one of his frequent listeners, ‘sounds like a rad dude’, will return. He gestures Søren over from where he’s now already making merry conversation with his colleague, who looks more bewildered than anything.

“What’s up?”

“Well, it seems my listeners like you more than they like me.” Eduard gestures at his computer screen, and Søren grins as he leans over next to him to read the messages. He’s taken his leather jacket off. There are freckles on his bare arms too, and he is making Eduard cold just by looking at them.

“Y’know, the only way to make ‘em rethink that is if I do come back, ain’t it? I can just be an all-round terrible co-host.”

“I like that idea,” Eduard replies, before turning his microphone on as the song ends. “Bruce Springsteen and Born to Run, and it’s the end of another afternoon. Kveta just got here—” he turns his attention to the next host, who nods— “Kveta, anything we can look forward to today?”

“No family members, I think, unless anyone wants me to prank call my stepbrother again.” She laughs. “I’ve got some great new tracks, and there might be some live music going on.”

“Very nice.”

“Of course. So, Eduard, are your family members coming back?”

Søren, who is still next to Eduard, pokes him in the side, then leans further forward to speak into his microphone.

“I’ve always dreamed of being a radio star.”

“I think he’s coming back to usurp me.” Eduard turns to Søren, almost poking his nose into the man’s spiky hair. “He’s already using my mic. And who knows what Peter and Lars will do, they’re twelve.”

“I guess that’s true,” Kveta replies. “Wow, Eduard, he’s really up in your face. I feel like someone should be shielding your cousins’ eyes.”

Peter laughs from where he’s now standing next to Vinh, peering at her screen. Vinh raises her eyebrows at Kveta, who smiles, bites her lip, and looks away. Eduard has to smother a laugh.

“Again, they’re twelve. And I think it’s time we all start heading home, so I’ll leave you to it, Kveta. Please don’t bother your stepbrother too much.” He tilts his head towards Vinh, quirking his mouth, and Kveta glares but sounds upbeat as ever when she replies.

“Can’t promise anything. Now, next hour, we’re starting off with some new music, so stay tuned. Eduard will be back tomorrow afternoon at four.”

The commercial break starts, and Eduard sets about packing up his things, gesturing Peter away from Vinh so Kveta can talk to her a bit before her own production team takes over. Most days, he’d stay at the studio for a while, but he decides to go home right away—Lars and Peter left some of their school supplies at his house that they’ll probably need tomorrow. So, after saying goodbye to Vinh and Kveta, he herds his cousins and Søren out of the studio and towards the elevator, which they ride down to the parking garage. Søren swings his backpack around and pulls out a knit red scarf.

When they reach the garage, the man grasps Eduard’s shoulder as they exit the elevator, stopping him in his tracks. The boys are already racing towards the car, which Eduard also wouldn’t have taken on most other days, preferring to use the bus, but he figured it’d be smarter to take his cousins that way.

“Hey,” Søren is saying, “I biked here, so—”

“In this cold? Do you want a lift?”

He blinks. Scratches his temple.

“There’s a bike carrier on my car,” Eduard adds. “It’s pretty new, I—”

“Uncle Eduard!” Peter calls, waiting by the back door of the car. Eduard holds up a hand—while Lars reminds his brother it’s first cousin once removed Eduard—and pulls the key fob out of his bag to unlock the door for him, then turns back to Søren.

“It’d be no problem; I could take you all over to your place after we stop by my house.”

“We should do dinner,” Søren says, à propos of nothing, his face bright in the gloom of the garage. “Yeah? I owe you one. What kinda food d’you like?”

“I… No, it’s fine, they’re my cousins, it was no trouble at all! I don’t need anything, Søren.” Eduard laughs awkwardly, fiddling with his glasses and looking towards his car. Peter is peering over the backseat.

“We could take the boys out somewhere—this weekend, maybe, before Tuomi and Torbjörn get back. Doesn’t have to be anything fancy.” His hand, still on Eduard’s shoulder, squeezes gently with every other word as if Søren is trying to get his usual gestures across that way. Or, now that he thinks about it, those are probably actual signs. He smiles.

“Well, maybe. I don’t have a show on the weekends.”

“Yeah?” When he pulls his hand back, Søren’s fingers glance off Eduard’s neck. They’re warm. “I’m sure we can find something even Lars will approve of.”

That sounds dubious, but Eduard will hold out hope. Søren agrees to a lift, though, and they figure out how to put his bike on the carrier without difficulties before piling in and driving over to Eduard’s house.

Søren traipses inside after Lars and Peter, peering around curiously.

“Nice place,” he tells Eduard, who waits in the hall while his cousins collect their things. And, “Hey, you should stay for dinner at mine.”

“Søren…”

“Just sayin’, why eat here all by your lonesome when there’s plenty of food at mine? You gotta go there anyways.” At this, he pokes Eduard’s arm gently. “I mean, if you need some alone time after dealing with those two, I ain’t judging.”

Huffing a laugh, Eduard shakes his head. “I don’t know how Tuomi and Torbjörn do it.”

“Together, and with practice, I guess. Wanna come?”

Eduard contemplates it for a moment, looking into the living room and thinking about the leftover spaghetti he has in the fridge.

“Alright. Thank you, Søren.”

Søren smiles, softer than seems to be the norm for him, his cheeks dimpling gently. It’s like a little ray of sunshine on a December day.

“Boys!” he yells, clasping Eduard’s shoulder again when he winces. “Sorry. I’m no good at regulating my own volume.”

Lars is glaring at his uncle, having already been standing in the doorway to the living room with his school bag in hand and having heard him loud and clear.

“Sorry,” Søren repeats, this time signing it as well, putting his hands together as if in prayer.

“What?” Peter yells back from somewhere else. Seconds later, he skids into the hall, his sneakers leaving black marks on the wood floor. “What.”

“Eduard’s coming over for dinner. Got everything?”

They both nod, and Peter claps Eduard on the back as they all head back out. Søren laughs. He takes his scarf off when he gets into the car this time.

“Hey, are you allergic to anything? Or vegetarian?”

“I’m not, don’t worry.” He checks over his shoulder that his cousins have their seatbelts on, then starts his car. “I mean, I don’t eat a lot of meat these days, but I won’t say no.”

“Hm, yeah, that’s good. I oughta be better at that.”

With Søren’s instructions—gestures included—Eduard finds his building on the outskirts of one of the older suburbs easily. Søren tosses Lars the keys to his apartment and the boys run off while Eduard helps him get his bike down from the car, then waits while he parks it somewhere in the shared storage space.

“Alright! C’mon, Eduard, I don’t really want ‘em to break my kitchen down.”

After taking the stairs, they reach Søren’s apartment on the second floor. The door has been left open, and little lights twinkle around the frame.

“Hey!” Søren says, surprised, as Eduard curiously looks around the narrow hall. It’s much neater than he somehow expected, probably just because of Søren’s slightly chaotic mannerisms. Since he sees that his cousins have lined their shoes up by the door, he takes his own off as well, putting them next to Peter’s.

Entering the living room, he understands Søren’s surprise. Peter and Lars are rushing to set the table, apparently trying to outdo each other in speed. There is a tiny Christmas tree on a dresser that suddenly seems quite precarious.

“Be careful,” Eduard says, a little feebly, and Peter grins at him, his hands stacked with far too many plates for four people. It seems to be going alright for now, so Eduard leaves them be to seek out Søren.

“Uh, Søren?” He walks into the kitchen. It’s a surprisingly large space, and Søren already has some pans out and is reaching up for a cutting board. He doesn’t appear to have heard Eduard over the clattering happening in the living room.

“Are you sure about… That?” Eduard asks, when the man has a hold of his cutting board and spots him.

“What, the boys? They’ll be fine.” Something crashes loudly, and Søren pulls a rueful face at the door. “I jinxed it.”

“We’ve got it, Uncle Søren!” Peter yells.

“I’m gonna just… Hey, Eduard, can you get some water boiling while I go check on that?”

“Of course,” he replies, holding a thumb up. Søren pauses on his way out of the kitchen and smiles.

“Of course,” he repeats, moving his hand forward while he first holds just his pinkie up and then opens his whole hand. He does it again, slightly slower, and Eduard tries to replicate the sign. “Hey, great!”

Before he rushes off to assess the damage, he makes an okay sign with one hand.

Eduard fills a pan with water, assuming it’s for the rice Søren’s put on the counter, and turns the stove on to heat it. Søren returns quickly, carrying almost all of the plates Peter was hauling around.

“I think Tuomi and Torbjörn are raising ‘em too well,” he says, putting the plates away. “I don’t think I ever voluntarily set the table until I moved out. Can you slice these peppers?”

Eduard can, while Søren pulls some chicken out the fridge to fry it.

“They’re just hungry. Besides, didn’t they just break a plate?”

“Just the one, it’s fine. I definitely wouldn’t have done a chore if I was hungry. Gotta wonder how Torbjörn turned out so decent.”

“Keeping you in check?”

Søren laughs heartily at that, leaning his hands on the counter so that his shoulders shake visibly. He’s just in his T-shirt again, and Eduard can see now that it is merch of a band he plays sometimes and likes well enough, although he wouldn’t call himself a fan. He slices the bell peppers and some cauliflower, and smiles as a delicious spicy scent fills the kitchen a while later.

Peter sidles into the kitchen as Søren covers the pan to let it simmer for a while. He looks like he’s about to lift the lid again.

“Hey, hey, watch out,” Søren says, pulling his hand away. “That’s hot.”

“I just wanna see.”

He’s always done that, as far as Eduard knows. He can clearly recall a load of pictures of toddler Peter pressed up against the glass of ovens and washing machines and microwaves. He wonders when he’ll grow out of it, or if he’ll be like Tuomi, who still watches whatever he’s cooking for at least ten minutes, but then Tuomi is bad at cooking and might just be making sure it’s not going to explode.

Peter stubbornly crosses his arms and stares at the pan.

“Are you planning on staying there?” Søren asks.

“Probably,” he replies brightly, turning his head to address his uncle. Søren throws a fond smile at him and ruffles his hair before he can duck away.

“Eduard, by the way, I still think we should get dinner this weekend,” he says, pointing a finger at Eduard, who accepts that with a helpless gesture, mostly aimed in an amused Peter’s direction.

“Is that where you get that stubborn streak from?” Eduard asks him, and both Peter and Søren burst out laughing at that.

“It’s like you’ve never even met his parents!”

“Pa says no one is allowed to play Monopoly anymore.” Peter shrugs. “Not that I wanted to, Monopoly’s boring, but Lars got real upset about it.”

“Dad stole all my hotels!” Lars yells from the living room, sounding extremely indignant. Tuomi really is that sort of person, Eduard thinks, glancing at Søren in amusement, but Søren is narrowing his eyes and looking at Peter questioningly.

“Dad stole Lars’s hotels,” the boy relays, and Søren nods, now returning Eduard’s look.

“No Monopoly, got it. I’m sure I got some other games, though, we’ll check it out later.”

Peter grins, nodding. Eduard fears that both his cousins have inherited Tuomi’s competitiveness.

Dinner is good. Eduard is used to eating by himself, or sometimes with Vinh or another coworker, often the early afternoon duo—he tends to spend that time looking at his phone, or, in the latter case, trying to mediate yet another argument between them. It’s nice to have someone to talk to instead of just listening to music or reading news articles.

Søren still gestures wildly while he’s eating, cutlery and all, sometimes even half-forming signs, but he somehow manages to avoid flinging any food as he does so. He says it’s an acquired skill, then launches into a story about throwing soup into Torbjörn’s hair when they were teenagers that has Peter laughing so hard he nearly chokes and Lars, in turn, yelling at him not to throw up or he’ll kill him.

“I’m not,” Peter replies, glaring fiercely even as he breaks out in a hacking cough again, and then quickly signs something at his brother that makes Lars glare back. They definitely inherited that from Torbjörn. Eduard gently claps Peter’s back, and even though he doesn’t think it’s helping much, Peter eventually quiets. His breathing settles back into a normal rhythm, and he takes a large gulp of his water.

“Peter, don’t confuse your cousin,” Søren says, making a downward slashing motion with both hands.

“Sorry, Uncle Eduard,” Peter tells him. He picks his fork back up.

“It’s fine,” Eduard replies, after realizing Søren is talking about Peter using sign language, which he doesn’t understand. Lars, on the other side of the table, rolls his eyes and touches his hand to his shoulder, which makes Søren sigh and shake his head at him.

“It is difficult, Lars.”

Eduard gestures for him to leave it be—wondering as he does so what his gesture might actually imply—and Søren doesn’t say anything else about it, but he does grumble, later, while they load the dishes into the dishwasher, that he knows his brother made it a point that they shouldn’t use sign language to exclude anyone on purpose.

“Probably ‘cause our parents had the same rule,” he explains, leaning back against the counter and crossing his arms. His T-shirt stretches across his shoulders, quite nicely, Eduard thinks. “Although that was mostly ‘cause we were better at it than them. Still are, and my mom would still put me in timeout too, 39 years old or not.”

“That sounds fair. I really didn’t mind, though.”

“It’s the principle of the thing, y’know?”

There is a ruckus from the living room. Søren raises his dark eyebrows questioningly.

“They’re, ah… They’re arguing over which game they want to play.”

“Yeah, that seems about right. Are you staying longer or are you heading home?”

“I should probably be going, I like to do some preparations before I go to sleep.” He adjusts his glasses. “Thank you for dinner. You’re always welcome at mine, too.”

“Might take you up on that, Eduard.” Søren runs a hand over his hair and pushes away from the counter. “I’ll probably see you around before the end of the week, I need your help with those kids.”

“Like I said, their parents do it together too.”

That gets him a lopsided grin and a wink that he doesn’t know what to think about but quite likes anyway. Eduard goes to collect his coat and shoes, bids his cousins a good night before they both try to convince him their choice of board game is the right one, and heads out. Søren walks him down to the parking lot.

“I’ll see you, then,” he tells the man, biting his lip when he gets another lopsided smile.

“See you ‘round, Eduard.” He waves shortly when Eduard pulls up in his car, illuminated for a moment by the headlights as he turns off the parking lot. Still just in his T-shirt.

Back home, Eduard leans over to get his papers out of the glovebox, and his hand brushes against something soft. Blinking, he picks it up from the passenger seat and lets the soft wool run across his hands. Søren’s scarf, he realizes, and takes it inside with him.

He’s sure he’ll have the opportunity to return it soon enough.

#Hetalia#denest#aph estonia#aph denmark#den is just one of those characters I keep getting weirdly specific headcanons about#I love the nonexistent logic of having someone named søren be the brother of someone named torbjörn#what with the opposed orthography#but like if my stories don't have a specific setting they're all just set in a place where wildly eclectic names are the norm#and also danish sign language#which by the way#big shoutout to tegnsprog.dk for having such an excellent sign language resource#that does not exist for dutch sign language and I feel like it should#the One Time me knowing danish comes in handy#anyway#w: 5000#aph sealand#aph ladonia#aph vietnam#aph czechia#u: human#that's enough tags from me

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

what was andrew jackson's thoughts on education or providing education to people?

Starting off with some background, it’s no secret that Jackson was one of the least educated US presidents in history, as he received little formal education. (source) A formal education was hard to attain for the vast majority of Americans during this period, and studying at a university was considered a privilege. Only the wealthy, including the Presidents before Jackson, could afford such an opportunity.

First is his thoughts on education. During his rise to fame, he prided himself on being a common, self-made man. He thus declared that education shouldn’t be a requirement for political leadership. (source)

But this doesn't mean he didn't care about education at all. According to an anecdote, he once debated with his uncle about the topic “what makes the gentleman?”. Jackson said “education” while his uncle said “good principles”. (source)

He also often urged his children to get an education. The best example I’ve found is this part of a letter he wrote to his son, Andrew Jackson Hutchings, which reads,

… and now is the time for you to obtain an education, which if you neglect, the day will come when you will sincerely regret your present mispent time—In a few years now, you will be of age and without an education, unless you attend better to your learning, than you have heretofore—I must again i[m]press upon your mind the great [value] of an education, and urge you for y[our] own benefit, to great application in you[r] studies so that you may at least be a good mathematician, as well as master of arithmatic, and that you learn to write a good hand, and become well acquainted with orthography, in which I find that you are at present, very deficient. (source)

We can conclude that he valued education and saw it as necessary, but was against the classism related to it.

Onto his views on providing education, he didn’t seem to endorse it. Jackson and his supporters “opposed reform as a movement” and Democrats “tended to oppose programs like educational reform mid the establishment of a public education system.” For example, they believed that “public schools restricted individual liberty by interfering with parental responsibility and undermined freedom of religion by replacing church schools.” (source)

On the other hand, Whigs believed that providing education was an obligation of the state (source), as they openly supported free public schools. However, it should be noted that all political parties at the time endorsed education. (source)

This sentiment is further supported by this statement in Jackson’s bank veto message, which reads,

Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. (source)

#virasinbox#anonymous#andrew jackson#historyposting#historyed#heehee not to flex but i emailed mark cheathem for help with the research and he replied *starts giggling* *kicking my feet in the air*#hope this helped anon!!!

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

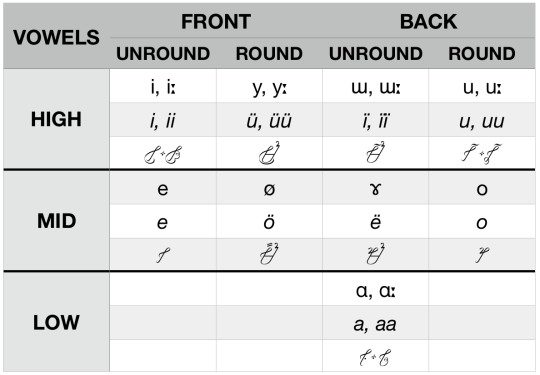

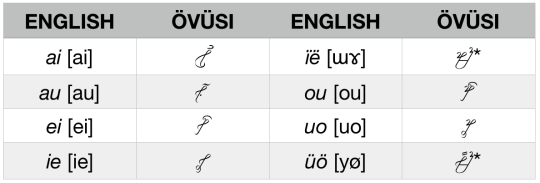

For the cats’ language, do you have a phonetic inventory (the sounds that are found in the language)? I’m really curious to see what it looks like. Loving that [ŋ] can occur word-initially by the way. It’s always cool to see conlangs that do away with conventions familiar to English speakers.

The editor here! The sounds that make up Felinespeak were largely extrapolated from the original Redux and iterated upon to make it not sound like English’s phonology pretending to be another language (a common issue with many conlangs). There are also some changes to the romanization system to make it more consistent.

Now there are fifteen consonant sounds and five(ish) vowel sounds. Here’s a link to an interactive IPA chart so you can hear the sounds being made.

Felinespeak has three stop/plosive consonants: /p/, /t/, and /k/, written in the Latin script as P, T, and K. The important thing to note with these sounds is that they’re never voiced (no /b/, /d/, or /g/) nor are they aspirated like English stops are (no /pʰ/, /tʰ/, or /kʰ/). For the less linguistically inclined, it’s basically the difference between “cat’s car” and “cat scar”. The first is aspirated - pronounced with a puff of air - and the second isn’t, which you can detect by putting your hand in front of your mouth as you say the /k/ sound. The stops in Felinespeak aren’t aspirated, but if you can’t not aspirate your stops, don’t sweat it. I have a hard time with it too.

The nasal sounds are still pretty standard: /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/, written as M, N, and Ŋ (or alternatively, NG). There’s nothing too special about these sounds, except that /ŋ/ can be used word-initially, like in the words ŋoþorr, “titan” or ŋwas, “unease, restless, unsettling”.

There are seven fricatives: /f/, /θ/, /s/, /ʃ/, /x/, /h/, and /ʍ/. I know some of these look scary, but most native English-speakers are familiar with most or all of them. /f/, /s/, and /h/ are pronounced and written exactly as they look, F, S, and H. /θ/ is one of the two dental fricatives English has, written in our orthography as TH. This is the sound heard in “thin”, “nothing”, “moth”, as opposed to the sounds in “this”, “father”, “clothe”, it’s voiced counterpart. It can be written as either TH or Þ depending on your fancy. /ʃ/ is simple enough, it’s the “shh” sound and is written as SH. Don’t be deceived by /x/, it’s not the “ks” sound, it’s the sound heard in Scottish “loch”, that sound made by bringing the back of the tongue up to the roof of the back of your mouth, possibly even made when going “ugh”. It’s a lovely sound, and written with CH. Lastly, /ʍ/, most English-speakers would perceive of this as “pronouncing the h” in words like “when”, “which”, and “white”. It’s written the same way, WH.

Felinespeak is rather unique in that it features two rhotic (r-type) sounds: /r/ and /ʀ/. English-speakers would be familiar with the former as the “rolled r”. If you can’t pronounce the alveolar trill, that’s fine, you can just pronounce it /ɾ/, a single tap, like the Japanese r. /ʀ/ is one of a few sounds English-speakers consider the “guttural r”, when the more technical term is the uvular trill, heard in standard German and some dialects of French and Dutch. When writing down Feline words, /r/ is written as R and /ʀ/ is written as RR. They can be all the difference to distinguish two words: mira “mother” vs Mirra “the Mother”. They were both picked since they resembled the purring and warbling sounds cats make.

Finishing up the consonants, we’ve got the approximants: /w/, /j/, and /l/. English is familiar with all three of these sounds, heard in “wine”, “yip”, and “leaf”. And, much to my dismay for /j/, they’re written the same way as they are in English: W, Y, and L.

And then we have the vowels. There’s five(ish) vowels, each with contrasting length: /i/, /ɛ/, /ɑ/, /o/, /u/, /iː/, /ɛː/, /ɑː/, /oː/, /uː/, and /ə/. The first five are written as I, E, A, O, and U. Long vowels can be written either by doubling the letter like Suriin or by indicating it with a macron Surīn. This means that “ee” and “oo” don’t make the /i/ and /u/ sounds that English-speakers would expect them to. Vowel length is important, as it distinguishes between different words. Mi is the affectionate way to say “mother”, like the English “mommy” or “mama”, but mii or mī is the word for one. /ə/ is an oddity. The cats wouldn’t consider it its own distinct sound, but it can show up in unstressed vowels and is highly dialectical. Diphthongs (vowels where one vowel slides into another, like “ow”) can occur, I just haven’t documented which ones, so assume all diphthongs are possible. Diphthongs and long vowels can’t occur within the same sound because just. Why. Why would you do that.

Due to these sound restrictions, some words have been changed from Redux to Iterum, including bel to pel and caen to chaen.

Hope that makes things simple!

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Aurebesh and cursive

I'm migrating a Twitter thread to Tumblr because twitter threads are hellish.

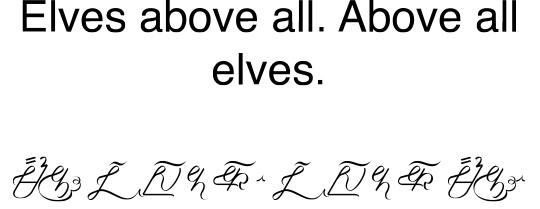

As a brief intro, I created a handwritten version of the Aurebesh for use on ChicksWithDice, because the current planet they're on uses paper books and pens. This post is going to be about orthography, and how to construct logical graphemes based on an extant ConAlphabet. So buckle up for a wild ride through proto-Canaanite scripts (namely Phoenician), modern Hebrew cursive, and the development of a cursive system.

Like most grapheme-based writing systems (as opposed to logograms and syllabaries) Aurebesh has a pretty direct connection to the Proto-Canaanite script system (and the alphabets derived thereof like Phoenecian and proto-Hebrew).

Let's take a look at a grapheme that exemplifies the connection. We don't need to go far to find our first culprit: A, א, and 𐤀. In Aurebesh, the character Aurek.

There's a pretty direct connection to be made from Phoenician directly to all 3 other characters. So in developing a handwritten system, I looked to the handwritten version of modern cursive Hebrew for inspiration (since I'm currently learning Yiddish for fun).

What stood out to me was how well cursive א translates into a cursive version of Aurek. It also worked for Besh/ב/B, Dorn/ד/D, Leth/ל/L and Resh/ר/R. I used the graphemes from ע, ס, and כ in other places as were appropriate, but they don't exactly correspond 1 for 1.

That leaves a hell of a lot of characters to fill in. So, I started thinking about how symbols would evolve as they were written over centuries, and people got lazy with their writing. The first thing I looked at was stroke count. When you need to write quickly you're looking at limiting the number of times you need to make distinct motions. Printed Aurebesh characters have a tiresome number of distinct movements. Aurek is a 6 stroke character. Besh is 7.

If we could take Aurek from 6 to 2 using cursive Hebrew as a guide and Besh from 7 to 3, the rest of the alphabet should follow similar conventions. Cresh could literally just be 1 stroke instead of 3 distinct lines. Esk could be written as 2 strokes instead of 4.

This ended up working for a large portion of the graphemes, which made life super easy. The hard part comes in dealing with graphically similar characters like Cherek and Krill, or Osk, Wesk, and Xesh. In their printed form, it's pretty clear each of these characters is distinct, but in a system where speed is emphasized, especially as we look to limit strokes, they tend to bleed together.

As an example, Cherek and Krill could both reasonably be represented by the cursive כ (see above). Cherek would also be a 1 for 1 phonemic correspondence to cursive Hebrew in that case, but graphically, Krill makes for a better analog. Krill would use the cursive כ and an alternative grapheme needed to be developed for Cherek. In that process, I looked at other alphabets and syllabaries that I had studied previously. Hiragana in particular stood out since the kana つ (tsu) has a similar vibe. Eventually, those inspirations evolved into what you'll see at the end of this post.

My instinct for Osk was straight up just an O or something akin to cursive ס, which is honestly just what I went for. Then I got to Wesk and went, "oh kriff". I took a look at my handy cursive Hebrew chart that I have hanging above my desk for reference, and tried to come up with something. I came up with a version of cursive פ but in all honesty, I'm not happy with it especially when I could have opted for cursive ם, which is literally right there. I think Wesk and Yirt are my weakest graphemes, and I am liable to redo them as I work on this project more.

With all that said in this long post, I probably owe you the actual Aurebesh. It's laid out as Roman, Printed Aurebesh, Handwritten Aurebesh. This is all subject to change, but I'm still pretty proud of the work I put into this! Thanks for reading this far!

If you'd like to support this kind of bullshit, and my Actual Play series visit the Soses Media Patreon

#Star Wars#chicks with dice#Orthography#aurebesh#this post is extremely nerdy#and is the result of a combination ADHD hyperfocus and Autism Special Interest

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

ArkAngel Part 1 - Chapter 7

Tags: Jake, Tessa being the Qweenie of the bad guys, mention of guns, spying on people, mentions of abuse, not perfect grammar/ orthography.

Word Count: 1775

Tag list: @triplexdoublex @welcometohoteldiablo @rumoured-whispers

Author’s note: Can Wes and Molly have peace for five minutes?? Well... if they had, this would be a much shorter story. For what is going to come, I preemtively say: I’m sorry. But I do love happy endings, so I hope you stay to see the end, because I think you’re going to like it this time.

On with the show!

It was Sunday when Jake and three of his father's men arrived at La Guardia airport. They had rented a four-bedroom apartment in Manhattan, near Molly's work. Every day they saw her pass in front of their windows, sometimes with Wes, sometimes with co-workers, but never alone. They had taken turns following her to her apartment, and found out that she lived with three other co-workers.

“Do you think she suspects something?” Jake asked Leo, looking out the window.

Molly was passing by at the time, accompanied by Wes and one of her roommates.

“It's probably just a common precaution,” said the man, watching her go by as well. “This is New York, after all.”

“The girl isn't stupid,” Leo's sister, Tessa, added, cleaning her gun. “I mean, she exposed you the first time, right?”

Leo and Johan laughed.

“I love you too, Tessa,” he replied, showing her his middle finger. “Can we go get her now?”

“We've been here a week, not yet,” Leo replied.

“But we already have the pattern of her comings and goings!” He protested.

“And she's never alone,” Johan pointed out. “If we try now, we're going to head headfirst into a cell.”

“Berlin is right,” Tessa said. “We have to wait for her guard to drop, and then we'll catch her.”

“Then you do think she’s is suspecting something.”

“I think you were such a fool to go threatening Hardy like that,” Tessa replied, starting to mount the gun. “And that we must not rule out that she has warned them.”

“I just wanted to get the cat out of the bag.”

“Not true,” Leo countered. “You were an idiot; the whole thing turned out well by pure chance. Today we will go to her apartment and put some microphones on,” he added. “Hopefully with a little patience, we will get information that tells us when we can go for her.”

Except for Jake, everyone else on the team had a skill that made them valuable: Leo was adept at planting bugs, tapping phones, and cloning SIM cards. Johan was an expert pickpocket and more than good at picking locks. Tessa was a firearms expert, an excellent markswoman, and had handled a hostage situation before.

The three of them knew that the only reason the boss' son was there was because The Irishman wanted the kid to learn something. Personally, Johan believed that he was too arrogant to learn a thing, but he was not going to be the one who would contradict the boss.

They arrived at Molly's apartment around noon, and after making sure that no one was there, Johan guaranteed them entry.

“Don't touch anything that isn't absolutely necessary, and if you do touch anything, make sure you leave it exactly where and how it was,” Leo ordered.

Jake just watched as Leo and Johan bugged the main rooms and tapped the landline. Unfortunately, Molly always carried her phone on her, so cloning the SIM card was not going to be possible at the moment. He wished once more to have Hardy on their side, so they could get into her email accounts.

“I hate posh kids,” Tessa commented, leaning into the bathroom. “Have you seen the amount of creams and makeup they have here?” she added, opening the cabinets. “And almost everything is expensive brands.”

“Couldn't we put up cameras?” Jake asked. “I mean, maybe that way we could get a more complete idea of her routine...”

“You want to see her naked, right?” Said Johan. He shrugged. “Trust me, it won't seem like such a good idea when you see her fucking Wes.”

“I'm not opposed to amateur porn, especially if it's free.”

“You're fucking gross,” Tessa commented.

“Ready!” Leo said then.

“Let's get out of here,” Tessa said.

They left the floor; fortunately, the door was one of those with a security lock that closes automatically from the outside, so that none of its inhabitants would suspect anything when they returned.

From that day on, they took turns listening. There was not much movement on the apartment, because most of its occupants spent the day outside (except Matt, who two days after the bugs were put on caught the flu and was working from home), and when they returned they were dedicated to normal activities: eating, watching TV, chatting, having sex...

“Damn, these kids are boring!” Tessa complained. “I know it's Monday night, but hell, a little more fun!”

“Are they watching Desperate Housewives again?” Her brother asked.

“Yes! Wait... this might be interesting.”

“Hey, I know you haven't been out lately, but it's my birthday!” Carla was saying. "Please."

“I don't know…” Molly said.

“Come on! It will only be one day, and then you can go back to that curfew that you have imposed on yourself.”

“Come on, Mol, we’re all going,” James encouraged.

“Even me,” Matt pointed out.

“Invite Wes if you want, I don't care as long as you come,” Carla insisted.

“Okay, I'll tell him.”

You (20:35):

This Friday is Carla's birthday and she has invited us out.

We could go.

Dopeman (20:36):

I don’t know…

You (20:36):

Please!

We've been like this for almost a month and no one has come for us.

And neither have there been any warnings from Q or any of the others.

Dopeman (20:37)

That does not mean that nothing is happening, just that they don't know.

You (20:37):

We were supposed to go on dates: go dancing, to the movies, to museums… and all we have done is order food delivery and watch movies on my laptop.

Dopeman (20:38):

It's not the only thing 😉

You (20:38):

You know what I mean.

Please.

If we go together, what could happen?

Dopeman (20:39):

Okay, but we will be moderate with the drinks.

You (20:39):

Of course.

I'm a good girl 😋

Dopeman (20:40):

Of course.

And if we are going to go out, put on the black sandals, the Roman ones.

You (20:40):

And I'll go get my pedicure done the day before.

Dopeman (20:40):

Don't tease me, woman xD

See you on Wednesday for lunch?

You (20:41):

Of course.

I love you ❤

Dopeman (20:41):

I love you too ❤

“Okay, we'll go to your party,” she informed Carla.

“Yes!” She exclaimed, hugging her.

“I think I'm going to read for a bit before I sleep, I'm running late,” she informed, getting up.

Matt waited half a minute before getting up and knocking on Molly's door.

“Mol, can I come in?”

“Yeah.”

Matt walked in and closed the door behind him. Leaning against the wood, he watched as she braided her hair.

“Hey, I don't want to stick my nose in your business, but is something going on between you and Wes?” he asked. She looked at him blankly. “I mean, is there something wrong?”

“Nothing's wrong between Wes and me,” she replied, starting the other braid. “Why you think so?”

“That new schedule that you have... You almost never leave the apartment for something other than going to work, going to the grocery store, or your karate and kickboxing classes, and he comes to walk you many days,” he pointed out, sitting in the chair of the desk. “I don't want to accuse him of anything, but… it doesn't look good.”

“Do you think Wes is trying to isolate me from my family and friends?” She asked incredulously.

“It's what it looks like,” Matt replied, shrugging. “I just… I want you to know that if you need help, you can count on me.”

“Matt, Wes isn't trying to isolate me from you guys. I know it might look like that from the outside, but… there's one thing in our past, and it may not have stayed there,” she said, finishing the second braid. “Wes is afraid something will happen to me. I'm a third Dan black belt, but my boyfriend is scared and… I'm just trying to reassure him.”

“That thing from your past… is it from the traumatic night you never talk about?” he dared ask.

"Exactly. If I tell you something, will you promise to keep the secret?” He nodded. “You can't tell anyone, not even James.”

“I won’t, I swear on Basquiat.”

“‘Dopeman’ wasn't just Wes's chat alias, it was what he really did for a living,” she whispered. “I helped him change his life after the traumatic night, but before that, he was selling drugs.”

“Oh… I understand. You're a box full of surprises, Mol.”

“You don’t even imagine. Thanks for caring about me, Matt,” she said, hugging him.

“James and I were talking about it, but he didn't dare ask. He said it was none of our business.”

On the apartment of O'Shea's goons, Tessa let out a triumphant cry.

“Well, yes, but sometimes you have to meddle a bit in other people's business,” she said. “You can tell him not to worry, everything is fine.”

“They are going out this Friday,” she informed them.

“Wes too?” Jake asked.

“Yes, but it's not a problem. We just have to separate her from her friends and she will be a piece of cake.”

If Tessa or any of the others had been listening to Molly and Matt's conversation, they wouldn't have thought that, but they didn't. Tessa put her headphones back on and caught that Carla couldn't decide between going to the Chat Noir club or going to the Moskova.

“They both appeal to me, you know?” she was saying. “The Chat Noir has a Parisian setting, and that's a huge point in its favour, but the Moskova has cheaper drinks and that handsome Russian waiter… Ivan, I think his name is.”

“Well, you have time to think about it,” James replied. “Personally he is not my type, but if you think you can be lucky, I vote for the Moskova.”

“What are we talking about?” Matt asked, returning.

“About the waiter Carla likes.”

“I don't know if I like him, I've barely spoken to him,” she defended herself. “But you have to admit that he is a sight for sore eyes, with those muscles and those eyes... I would do a lot of bad things to him if he allowed me.”

“I hate these kids!” Tessa exclaimed, taking the headphones off.

“You can rest for today; we already know where they will be.”

“I can take over for you,” Jake suggested.

But he didn't hear anything relevant, and soon after, Matt, James, and Carla went to bed. He switched to Molly's room, hoping to hear her having phone sex with Wes (it had happened a couple of times before), but she was already asleep.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the past 6 months, I’ve been taking studying Japanese more seriously. From the time I quit studying Japanese in elementary school until now, I had very little formal schooling in Japanese, and whatever was formal, wasn’t very effective.

*Run down for people who don’t know: I grew up speaking Japanese outside of Japan so my knowledge of it is like..half there half not.

After learning Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese to a relatively high level many years ago, coming back to Japanese now, I realized that I forgot what it felt like to learn another language.

For the past few months, I’ve been trying to study the kanji for words I already knew — that way, I would only have one thing to learn on top of old knowledge, as opposed to learning a new word + new kanji for that new word. For example, I grew up hearing the word とおい (tōi, kanji: 遠い) so I would practice writing and visualizing the kanji.

More recently, I flipped from studying kanji to studying more (new) vocabulary words. Obviously studying a language like Spanish or Portuguese from English won’t be as difficult as going to Japanese from English, especially in terms of vocabulary (and orthography).

What made me think about this was something as “simple” as school subjects. For example:

English-Portuguese-Japanese

Psychology — Psicologia — Shinrigaku (心理学)

Literature — Literatura — Bungaku (文学)

Geography — Geografia — Chirigaku (地理学)

Engineering — Engenharia — Kōgaku (工学)

Having English as a native language, to learning Spanish and Portuguese, once I “learned” about the rules that certain words took from one language to the other, I could pretty much guess that psychology and literature would be something like psicologia and literatura, respectively; and if I was wrong, I would be corrected, simple. But from something like English to Japanese, you can’t just “guess” for languages that don’t really share any kind of history together.

I never learned (or at least retained) something like the names of school subjects in Japanese for multiple reasons, the first being that the acquisition of that vocabulary was never really enforced, even if we went over the words. Second, because I guess I personally never felt the need to know it as a kid, since I wasn’t formally schooled in Japanese in those subjects, and third, because it didn’t have a high enough frequency in my household for me to have known how to say chemistry, biology, math, literature, etc.

What scared and prevented me from learning Japanese for so long, I think, was the fear of kanji. I knew that on- and kun-yomi gave kanji so many different readings in different contexts, and how could I memorize and effectively recall more than a thousand characters, if I could even get that far?

My perspective on that changed when I recently tried to learn new vocabulary. In my notebook, I wrote the school subjects in English, then in hiragana for the Japanese version, since originally I intended to learn the words by how they sound first. I would learn the kanji after I could successfully recall the words.

But what I realized that the kanji actually helps me remember how to say the words.

For psychology, shinrigaku written in hirgana is just a cluster of sounds to me. But when written out in kanji, shinrigaku (心理学) is heart (心), logic (理) and study (学), all of which semantically, I could see being related to the idea of the field of psychology.

The same goes for geography (chirigaku, 地理学). In kanji, it’s ground/earth (地), logic (理), study (学). What helped me even more with this one, was that I recognized the first kanji 地 as the same kanji (and luckily, sound) that appears in map, 地図 (chizu).

While I believed for the longest time that kanji would be the most difficult aspect of learning Japanese, I ran into a roadblock that briefly made me think vocabulary would be even harder than kanji. But taken together, with just a bit of knowledge about certain kanji, thanks to my childhood experience of growing up with it, my kanji has been able to help me expand on my vocabulary.

This experience has been a rather cyclical one. When I was a kid in Japanese school, I believed my strongest area was vocabulary. I always struggled with kanji. Studying Japanese as an adult, I dove head-first into studying the kanji for words I was already familiar with, but when trying to expand my vocabulary, kanji has stepped in and stepped up to help me with my vocabulary by helping me visualize and associate certain sound-meaning pairs with new vocabulary.

I realize that for beginners, kanji is a daunting thing and takes a lot of time to learn and retain. I realize that not everyone has the same background as I do with Japanese. But once you’re familiar with kanji, you can see it popping up in new places, whether it’s embedded within another character or in a compound (words with more than one kanji character) and it has the ability to help you. Not hinder you.

It’s not easy learning a new language, and in my case, it’s not easy trying to add on to a language that comes semi-easily and semi-not. Some languages are hard on multiple fronts, like how I thought Japanese was, especially the kanji and vocabulary. But interestingly, I think it’s all starting to come together like the coherent language it’s supposed to be. And it’s beautiful when it does.

It just may take a while to get there.

#learn japanese#Japanese#language learning#langblog#langblr#kanji#learn kanji#vocabulary#language thoughts

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

hm ive been messing around with the numeric notation form of my conlang Chatter for what feels like forever but i think im finally nailing a system down?

im using a numerological key where numbers can represent up to 5 different phonetic values, and at first i was thinking of differentiating which are transliterated when by assigning certain trinary roots, kinda like arabic. but then it would be a lot of strict memorization, and it wasnt connected enough to the 8-tone system for my liking so now it’s more like...

im separating said roots into semantic “clades”? (ty tumblr user for this handy terminology) aka these phonetic values (represented in the numeric orthography by an integer, and a clarifying leveling arrow that denotes register) that are strictly related to or used under particular grammatical circumstances. that way you know if say, a word is written 58⮅8312 (random example, meaningless) you know thanks to the clarifying arrow set (in this case ⮅, denoted phonetically with ◌́) that the preceding 58 is read /e/ /f/, as opposed to the 58 in 58⭽17, which is read /e/ /p/ (as denoted by ⭽, or ◌̣ phonetically)

however this does mean, in this fake example that will eventually extend to reality at some point and i’ll contend with it then, that /f/ and /p/ would be written identically in the calligraphic (sigil) orthography. oh well i’ll get to that when i get to it lol

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before Breakfast?? Instructions for Weekday Prayers in a Venetian Dialect

Fifty-two discoveries from the BiblioPhilly project, No. 22/52

Book of Hours for the Use of Rome, University of Pennsylvania, Ms. Codex 688, fol. 13r

The Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis project did not formally include manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania, which had already been digitized and made available on the OPenn repository several years ago. However, these manuscripts will soon be integrated within the BiblioPhilly browsing interface in an effort to produce a comprehensive digital resource for pre-modern manuscripts in the region. Preparations for the upcoming “Making the Renaissance Manuscript: Discoveries from Philadelphia Libraries” exhibition I am curating at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts (February–May 2020) have provided an additional reason for looking more closely at some of Penn’s European manuscripts, which still have plenty of secrets to reveal. As many of us know, mere digitization does not equal discovery!

The compact Book of Hours that is our subject today, UPenn Ms. Codex 688, has perhaps evaded attention because it contains no secondary decoration, apart from a large initial D and some vinework on folio 13r which may well be later in date. The textual content of Italian Books of Hours – as distinct from their decoration – has received relatively little scholarly attention, though the situation is changing.1

Ms. Codex 688 is written in a fine humanist hand. It is a late example of a format and genre popular in Central and Northern Italy earlier in the fifteenth century. The text of the Calendar and the principal offices is in Latin, as is the case in the overwhelming majority of Books of Hours from all regions of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe. The Calendar contains saints venerated in Northern Italy generally, including Ambrose of Milan (7 December), Secundus of Asti (1 June), and Prosdocimus of Padua (7 November). Reflecting the increasing prevalence of vernacular prayer in the fifteenth century, towards the end of the book, after the Hours of the Holy Spirit (fols. 86r–128v), there are weekday prayers in Italian. This particularity had been noted without further elaboration in the the existing catalog record for the manuscript, and is not altogether surprising.

But what do these prayers actually consist of? They are in fact a set of devotions intended to be performed in front of a crucifix. This is a rather precise and unusual series of prayers for a Book of Hours, perhaps related to the fact that the book contains no illuminations.2 The prayers are also a reminder of how Books of Hours were often intended to be employed in concert with works in other media, in this case a sculpture. There is one prayer for each day of the week plus another for Palm Sunday, and each is prefaced by detailed instructions about the specific gestures to be made by the devotee while reciting the text.