#who first wrote the bhagavad gita?

Note

what are all the songs different beatles wrote about the breakup/other beatles/the drama on their solo albums?

Possibly non-exhaustive list, let me know if I'm missing any!

Ringo

Back Off Boogaloo (1972)

Ringo says it isn't about Paul. It definitely sounds like it's about someone. He was publically critical of Ram and McCartney, and the song contains the lyrics 'Get yourself together now / And give me something tasty, / Everything you try to do / You know it sure sound wasted!' Hmmm.

Early 1970 (1970)

This is probably the least bitter song written about the breakup, which I feel makes sense. While there was that incident with Paul in March 1970, for the most part, he maintained pretty good relations with the other Beatles. Nobody was on the verge of starting a blood feud with Ringo. It's Ringo, folks! Everybody likes Ringo.

George

Wah Wah (1970)

The fact that he wrote this directly after leaving the band during the Get Back sessions is really all you need to know.

Isn't It a Pity (1970)

Isn't it just? Though he wrote this years before the breakup, it takes on a new meaning after it. Not to crib from the YouTube Beatles man, but the fact that they'd been rejecting this since 1966...

Run Of The Mill (1970)

They're calling it 'the head BIC of Paul McCartney diss tracks.'

Sue Me, Sue You Blues (1973)

- most litigious Beatle

Paul

Every Night (1970)

And thus began Paul McCartney's string of 'my life is shit but my wife is hot' songs.

Man We Was Lonely (1970)

My Life Is Shit But My Wife Is Hot (Part 2)

Too Many People (1971)

World, here's my album about how great it is to be heterosexual and live on a farm. The first song is about how my old songwriting partner and his wife suck because I'm not mad and I'm actually laughing.

People think this song must be covertly cruel because of how John responded, and the haha you're on heroin line is pretty low, but what nobody takes into account is how it's the equivalent of holding your finger really close to someone's face and saying I'm not touching you! I'm not touching you! Hehe. It's annoying. You want to punch it.

3 Legs (1971)

This song is really cutting in the same way Paul thinks signing 'piece of cake' as 'piss off cake' is cutting.

Dear Boy (1971)

Paul claims this song is about Linda's ex-husband.

What did this man ever do to you besides divorce Linda, father Heather, AND let you adopt her, all of which were great for you? Where's this coming from?

Dear Friend (1971)

Dear Friend and Too Many People being released the same year is pretty funny, but nowhere near as funny as Jealous Guy and How Do you Sleep? being on the same album.

Hon. Mention: well what is that 'we believe that we can't be wrong' bit supposed to mean?

John

I Found Out (1970)

I've seen religion from Jesus to Paul. What Paul? Oh, you know, Paul.

God (1970)

It's delightfully seventeen-year-old-experiencing-a-breakup-for-the-first-time to rank disbelief in The Beatles over not believing in: the Bible, Jesus Christ, the Bhagavad Gita, John F. Kennedy. And I'm all for it.

How Do You Sleep? (1971)

It's her. The sexy, weirdly disjointed song that Went Too Far. Can I be honest? This is so tame. And half the lyrics don't even make sense. The cruelty of this song is in how dismissive and impersonal it is rather than anything to do with the actual words.

I like to think of Run Of The Mill/Too Many People/How Do You Sleep? as a matching set because they display the individual worst qualities of the people who made them. Respectively: bitchy, annoying, and mean.

Jealous Guy (1971)

I Know (I Know) (1973)

[Insert comparison of opening riff of I Know (I Know) Vs. opening riff of I've Got A Feeling] Nice use of leitmotif, Mr. I-hate-musicals.

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spring Break Recap - with pictures :)

the day we got off my friends and I went out to town and went to the beach. (so so grateful for where I live)

my (not so baby anymore) cousin visited from Switzerland! we did so many things since this is the first time she had come to Scotland, she is such a bookworm so me and my dad bought her some books from Waterstones. Love her sm :)

Wrote a letter to my school teacher about joining an abroad programme. I really hope I get in as I honestly believe it would be life changing. this was a draft dw! didn't look this scruffy on the final one :P

Cat shelter volunteering (I didn't get any photos of the shelter as I felt that would be inappropriate) this was on the way back though and I thought It looked magical. forever grateful for the scenery around me.

Played around with my new keyboard. It's a Casio and I love it sm, it was gutted by my uncle and auntie from Switzerland. I partially learned Chemtrails Over The Country Club by Lana Del Rey.

My friends birthday party!!! we did pottery painting and I got to paint a highland cow :D got ice cream (yum) and went to the park after.

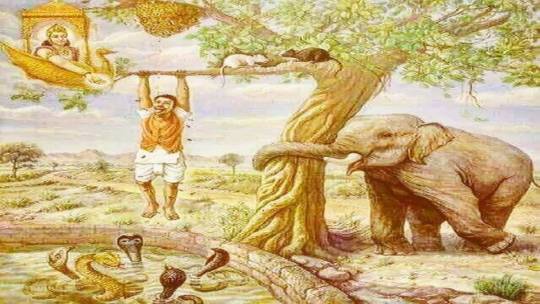

Started reading the Bhagavad Gita. For those who are not aware, the Bhagavad Gita is a Hindu epic scripture that is part of a larger collection of works known as the Mahabharata. The Mahabharata is a Sanskrit epic consisting of over 100,000 shloka (a form of long prose passage) fully forming in to about 1,800,000 (1.8 mil) words and is approximately ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined. The length explains why most only read smaller portions such as the Bhagavad Gita which is in fact a poem! ok I could talk about this forever but I hope that someone learned something new from my spiel :P.

Other stuff I did

-Reorganised my note taking and filing system (I could make a whole post about that)

-looked through all my subject specifications to get a feel of how many topics were are (and sub topics... and sub sub topics :,) )

-painted a mini canvas for my friend (dw that wasn't the only thing I got for her birthday)

-did some sketching (my artistic ability comes in waves)

-played Roblox, idc If its childish SUE ME (I am undefeated in paintball 🥱)

-did my extracurriculars (Sangeet and Bengali)

-Celebrated Poyla Boishakh and Vhaisakhi

Goals for new term

-study at least an hour on weekdays

-ace my sangeet exam

-get >6 on everything

-plan for mocks accordingly

-stay consistent

-do assignments as soon as they are given

-have fun

..............................................................................................................................

Ok this was long but I feel as if I did my break justice, a lot went on and it would be wrong to not give details.

thank you so much for reading this long post

Signing off~

StingrayStudies

#student#studyspo#study motivation#study#studying#studylapse#studyinspo#studyblr#bhagavad gita#hinduism#hindi#desi studyblr#desi teen#desiblr#desi tag#desi tumblr#study aesthetic#study blog

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.V. SUBBARAMAYYA,

part 2

My first pilgrimage to Sri Ramanasramam was on 8th June 1933. From Kanchipuram, where I had accompanied my mother to attend a function, I travelled alone to Tiruvannamalai. I was at that time in great sorrow, having suffered my first bereavement the previous December when my two-year-old son died from what the doctors could only describe as heart failure.

For over two years I had been reading the works of Sri Bhagavan and other ashram literature. My main interest had been literary rather than philosophical. I had been struck with wonder at the style of the Telugu Upadesa Saram that, in its simplicity, felicity and classic finish, equaled that of the greatest Telugu poet Tikkana. I had felt convinced that a Tamilian who could compose such Telugu verse must be divinely inspired. I wanted very much to see him. However, in view of my recent bereavement, my immediate quest at that time was for peace and solace.

I had my first darshan of Sri Bhagavan on the morning of my arrival. As our eyes met, there was a miraculous effect upon my mind. I felt as if I had plunged into a pool of peace. With closed eyes, I sat in a state of ecstasy for nearly an hour. When I came back to normal consciousness, I found someone spraying the hall to keep off insects, and Sri Bhagavan mildly objecting with a silent shake of his head.

Sri Bhagavan was speaking to someone. Since he seemed to be in a mood to talk, I boldly asked him my first question: The Bhagavad Gita says that mortals cast off their worn-out bodies and acquire new bodies just as one casts away worn-out clothes and wears new garments. How does this apply to the death of infants whose bodies are new and fresh?'

Sri Bhagavan promptly replied, 'How do you know that the body of the dead child is not worn out? It may not be apparent, but unless it is worn out, it will not die. That is the law of nature.'

This was the extent of my interaction with Sri Bhagavan on this first visit. Immediately after lunch, I left the ashram without even taking leave of Sri Bhagavan. I came and went incognito as an utter stranger.

As I write these words more than twenty years after this first meeting, I still feel the glow of joy that was revealed to me in that first darshan. But to capture the untrammeled exhilaration of that meeting and the transforming effect it had on my life, I have to go back to an ecstatic poem I wrote not long afterwards:

Eureka! I've found it! I've found it!

the missing link of this well-knit chain,

the keystone of this unending arch,

the correct solution of this cross-world's puzzle,

the only way out of this vicious circle, the pass to heaven's banquet,

the patent for immortality,

the armor against fate,

the death destroyer.

I've found it! I've found it!

the meeting point of matter and spirit,

the spell of beauty, the enchantment of love,

the magic touch that makes all beings one,

the fountainhead of joy,

the true philosopher's stone,

the secret of secrets,

the grand mystery,

I've found it! I've found it! Eureka!

- The Power of the Presence, III

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mahabharata

The Mahabharata is an ancient Indian epic where the main story revolves around two branches of a family - the Pandavas and Kauravas - who, in the Kurukshetra War, battle for the throne of Hastinapura. Interwoven into this narrative are several smaller stories about people dead or living, and philosophical discourses. Krishna-Dwaipayan Vyasa, himself a character in the epic, composed it; as, according to tradition, he dictated the verses and Ganesha wrote them down. At 100,000 verses, it is the longest epic poem ever written, generally thought to have been composed in the 4th century BCE or earlier. The events in the epic play out in the Indian subcontinent and surrounding areas. It was first narrated by a student of Vyasa at a snake-sacrifice of the great-grandson of one of the major characters of the story. Including within it the Bhagavad Gita, the Mahabharata is one of the most important texts of ancient Indian, indeed world, literature.

Learn more about Mahabharata

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early in the morning of July 16, 1945, before the sun had risen over the northern edge of New Mexico’s Jornada Del Muerto desert, a new light—blindingly bright, hellacious, blasting a seam in the fabric of the known physical universe—appeared. The Trinity nuclear test, overseen by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, had filled the predawn sky with fire, announcing the viability of the first proper nuclear weapon and the inauguration of the Atomic Era. According to Frank Oppenheimer, brother of the “Father of the Bomb,” Robert’s response to the test’s success was plain, even a bit curt: “I guess it worked.”

With time, a legend befitting the near-mythic occasion grew. Oppenheimer himself would later attest that the explosion brought to mind a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, the ancient Hindu scripture: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.” Later, toward the end of his life, Oppenheimer plucked another passage from the Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Christopher Nolan’s epic, blockbuster biopic Oppenheimer prints the legend. As Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) gazes out over a black sky set aflame, he hears his own voice in his head: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The line also appears earlier in the film, as a younger “Oppie” woos the sultry communist moll Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). She pulls a copy of the Bhagavad Gita from her lover’s bookshelf. He tells her he’s been learning how to read Sanskrit. She challenges him to translate a random passage on the spot. Sure enough: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” (That the line comes in a postcoital revery—a state of bliss the French call la petite mort, “the little death”—and amid a longer conversation about the new science of Freudian psychoanalysis—is about as close to a joke as Oppenheimer gets.)

As framed by Nolan, who also wrote the screenplay, Oppenheimer's cursory knowledge of Sanskrit, and Hindu religious tradition, is little more than another of his many eccentricities. After all, this is a guy who took the “Trinity” name from a John Donne poem; who brags about reading all three volumes of Marx’s Das Kapital (in the original German, natch); and, according to Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography, American Prometheus, once taught himself Dutch to impress a girl. But Oppenheimer’s interest in Sanskrit, and the Gita, was more than just another idle hobby or party trick.

In American Prometheus, credited as the basis for Oppenheimer, Bird and Sherwin depict Oppenheimer as more seriously committed to this ancient text and the moral universe it conjures. They develop a resonant image, largely ignored in Nolan’s film. Yes, it’s got the quote. But little of the meaning behind it—a meaning that illuminates Oppenheimer’s own conception of the universe, of his place in it, and of his ethics, such as they were.

Composed sometime in the first millennium, the Bhagavad Gita (or “Song of God”) takes the form of a poetic dialog between a warrior-prince named Arjuna and his charioteer, the Hindu deity Krishna, in unassuming human form. On the cusp of a momentous battle, Arjuna refuses to engage in combat, renouncing the thought of “slaughtering my kin in war.” Throughout their lengthy back-and-forth (unfolding over some 700 stanzas), Krishna attempts to ease the prince’s moral dilemma by attuning him to the grander design of the universe, in which all living creatures are compelled to obey dharma, roughly translated as “virtue.” As a warrior, in a war, Krishna maintains that it is Arjuna’s dharma to serve, and fight; just as it is the sun’s dharma to shine and water’s dharma to slake the thirsty.

In the poem’s ostensible climax, Krishna reveals himself as Vishnu, Hinduism’s many-armed (and many-eyed and many-mouthed) supreme divinity; fearsome and magnificent, a “god of gods.” Arjuna, in an instant, comprehends the true nature of Vishnu and of the universe. It is a vast infinity, without beginning and end, in a constant process of destruction and rebirth. In such a mind-boggling, many-faced universe (a “multiverse,” in the contemporary blockbuster parlance), the ethics of an individual hardly matter, as this grand design repeats in accordance with its own cosmic dharma. Humbled and convinced, Arjuna takes up his bow.

As recounted in American Prometheus, the story had a significant impact on Oppenheimer. He called it “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.” He praised his Sanskrit teacher for renewing his “feeling for the place of ethics.” He even christened his Chrysler Garuda, after the Hindu bird-deity who carries the Lord Vishnu. (That Oppenheimer seems to identify not with the morally conflicted Arjuna but with the Lord Vishnu himself may say something about his own sense of self-importance.)

“The Gita,” Bird and Sherwin write, “seemed to provide precisely the right philosophy.” Its prizing of dharma, and duty as a form of virtue, gave Oppenheimer’s anguished mind a form of calm. With its notion of both creation and destruction as divine acts, the Gita offered Oppenheimer a frame of making sense of (and, later, justifying) his own actions. It’s a key motivation in the life of a great scientist and theoretician, whose work was marshaled toward death. And it’s precisely the sort of idea Nolan rarely lets seep into his movies.

Nolan’s films—from the thriller Memento and his Batman trilogy to the sci-fi opera Interstellar and the time-reversal blockbuster Tenet—are ordered around puzzles and problem-solving. He establishes a dilemma, provides the “rules,” and then sets about solving that dilemma. For all his sci-fi high-mindedness, he allows very little room for questions of faith or belief. Nolan's cosmos is more like a complicated puzzle box. He has popularized a kind of sapio-cinema, which makes a virtue of intelligence without being itself highly intellectual.

At their best, his movies are genuinely clever in conceit and construct. The one-upping stage magicians of The Prestige, who go mad trying to best one another, are distinctly Nolanish figures. The tripartite structure of Dunkirk—which weaves together plot lines that unfold across distinct periods of time—is likewise inspired. At their worst, Nolan’s films collapse into ponderousness and pretension. The barely scrutable reality-distortion mechanics of Inception, Interstellar, and Tenet smack of hooey.

Oppenheimer seems similarly obsessed with problem-solving. First, Nolan sets up some challenges for himself. Such as: how to depict a subatomic fission reaction at Imax scale or, for that matter, how to make a biopic about a theoretical physicist as a broadly entertaining summer blockbuster. Then he sets to work. To his credit, Oppenheimer unfolds breathlessly and succeeds making dusty-seeming classroom conversations and chatty closed-door depositions play like the stuff of a taut, crowd-pleasing thriller. The cinematography, at both a subatomic and megaton scale, is also genuinely impressive. But Nolan misses the deeper metaphysics undergirding the drama.

The movie depicts Murphy’s Oppenheimer more as a methodical scientist. Oppenheimer, the man, was a deep and radical thinker whose mind was grounded by the mystical, the metaphysical, and the esoteric. A film like Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life shows that it is possible to depict these sort of higher-minded ideas at the grand, blockbuster scale, but it’s almost as if they don’t even occur to Nolan. One might, charitably, claim that his film’s time-jumping structure reflects the Gita’s notion of time itself as nonlinear. But Nolan’s reshuffling of the story’s chronology seems more born of a showman’s instinct to save his big bang for a climax.

When the bomb does go off, and its torrents of fire fill the gigantic Imax screen, there’s no sense that the Lord Vishnu, the mighty one, is being revealed in that “radiance of a thousand suns.” It’s just a big explosion. Nolan is ultimately a journeyman technician, and he maps that personality onto Oppenheimer. Reacting to the horrific, militarily unjustifiable bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima (which are never depicted on-screen), Murphy’s Oppenheimer calls them “technically successful.”

Judged against the life of its subject, Oppenheimer can feel like a bit of let down. It fails to comprehend the woolier, yet more substantial, worldview that animated Oppie’s life, work, and own moral torment. Weighed against Nolan’s own, more purely practical, ambitions, perhaps the best that can be said of Oppenheimer is that—to paraphrase the physicist’s actual reported comments, uttered at his moment of ascension to the status of godlike world-destroyer—it works. Successful, if only technically.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oppenheimer the movie.

I may not bother to see it. I know the story. The birth of the A-Bomb is a great and terrifying story. I grew up in the duck and cover age. If you do not know about that google it. Feeling fear makes one want to know why. The movie explosions may be fun, but my wife hates things like that and so its go alone or not at all.

The Manhattan project was huge, dangerous, and expensive. It established towns built for the job that were not there before. In Oak Ridge, Tennessee and Los Alamos, New Mexico new towns eventually small cities were made. One because there was abundant electrical power the other because it was so isolated and remote in case something happened.

Money was no object it was war.

First thing to note is that it was not the most expensive WW2 project. Developing the Boeing B29 bomber cost more. That is just one plane type.

The B29 is the plane that dropped the two A-bombs in Japan. It is also the plane that firebombed cities in Japan which actually killed more people and destroyed more homes that the A-Bombs. I do not say that to minimalize the impact of the A-Bomb. It was horrible, but many other horrible things were done as well by the winning side.

I want to talk about the Bhagavad Gita. Hard turn there? No not really. Much is made of the Oppenheimer Quote "Now I have become Death destroyer of Worlds". As in many things there are layers to see that superficial people will miss. That is a line from the Bhagavad Gita where Krishna who is a powerful god avatar shows his "true" form of Vishnu to Arjuna the prince. In doing so he recites those words.

At issue is Arjuna, a Prince in command of an army who does not want to fight the battle as the other side is powerful and has his friends and relatives and revered teachers in it. He knows many will die and is racked by guilt and reluctance. The back story is long and complex and beyond knowing this immediate situation is not necessary to get into.

I am far from a scholar, but Oppenheimer was. He read and translated the story from Sanskrit. He also spoke German Fluently as he was of German Jewish heritage which is why his family moved to the US. He studied Physics in Germany and wrote several papers in German and that is where he got his PhD in 1927. He knew most if not all the people working in Germany in advanced Physics. He had friends there.

When a few scientists during WW2 wrote the US president a letter noting that a huge new bomb was possible and that the leading experts were in Nazi Germany the math was done. It was a race. It was war, and I am still talking about the Bhagavad Gita.

The core issue is Dharma / Karma and well as I said I am not a scholar, but I take those as a mixture of Fate and Duty. The battle Arjuna must fight must go on, it will go on. That is Fate. He must do his best as a soldier and general that is duty. There is no choice. Krishna is explaining in detail why he must proceed.

So here is a man deeply conflicted with the skills and knowledge to do a hard thing who must actually do it even though others, many who he knows and loves may die.

Oppenheimer knew that the bomb was possible. He knew the people on the other side who were working on it and could do it. He knew it would be done. As it could be done it must be done. All that is discussed in the Bhagavad Gita and was deeply known to Oppenheimer.

So the simple line about destroyer of worlds is not as simple as simple people would have it.

Oppenheimer became a proponent of nuclear disarmament. He was also caught up in the red scare of Joseph McCarthy. He knew communists. They were for a long time just a political movement. Then they became the Enemy in the USA. Just as Jews were the Enemy in Nazi Germany. A convenient hate target for small people who craved power.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of Aldous's major preoccupations was how to achieve self-transcendence while yet remaining a committed social being.

Julian Huxley, on his late brother.

Today (11/22/23) marks the sixtieth anniversary of the death of Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World. Aldous Huxley was an interesting figure for many reasons, but it was this work, a work that warns of a future in which a combination of fetal manipulation and social conditioning conspire to cause people to "come to love their oppression," that has made him a household name.

A spirited spiritualist, Aldous Huxley had an interest in mysticism of all kinds, and it was this interest that brought him into contact with the Southern Californian Vedanta Society, which was founded by Swami Prabhavananda (who authored The Sermon on the Mount According to Vedanta). As a member of this society, Huxley wrote a series of articles that sought to explain spiritual principles and practical mysticism, using the vocabulary of the Christian and Vedantic Hindu traditions interchangeably. Among his more noteworthy works was his commentary on The Lord's Prayer, and an introduction to Prabhavananda's translation of the Bhagavad Gita.

Huxley's perspective on life has been referred to by at least one author as "Orientalized Christian," but a more accurate (and less offensive) label might be that of New Age. His opinions on mysticism and spirituality can be found in his book, The Perennial Philosophy, as well as the appendices of The Devils of Loudun. Huxley believed in the importance of the dignity of the individual, while at the same time fearing the effacement of individual identity through mob mentality. Some quotes for Aldous Huxley below:

"The end of human life cannot be achieved by the efforts of the unaided individual. What the individual can and must do is to make himself fit for contact with Reality and the reception of that grace by whose aid he will be enabled to achieve his true end. [...] We need grace in order to be able to live in such a way as to qualify ourselves to receive grace."

"First Shakespeare sonnets seem meaningless; first Bach fugues, a bore; first differential equations, sheer torture. But training changes the nature of our spiritual experiences. In due course, contact with an obscurely beautiful poem, an elaborate piece of counterpoint or of mathematical reasoning, causes us to feel direct intuitions of beauty and significance. It is the same in the moral world."

"Civilization demands from the individual devoted self-identification to the highest of human causes. But if this self-identification with what is human is not accompanied by a conscious and consistent effort to achieve upward self-transcendence into the universal life of the Spirit, the goods achieved will always be mingled with counterbalancing evils."

#Aldous Huxley#Christianity#Hinduism#Vedanta#spirituality#mysticism#New Age#grace#goodness#Holy Spirit#beauty

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan's sweeping new biographical thriller about the "father of the atomic bomb", has opened to a glowing reception around the world. In India, it's been a hit too but some have protested against a scene depicting the scientist reading the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism's holiest books, after sex. Oppenheimer learnt the ancient Sanskrit language and counted the book as one of his favourites.

In July 1945, two days before the explosion of the first atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert, Robert Oppenheimer recited a stanza from the Bhagavad Gita, or The Lord's Song.

Oppenheimer, a theoretical physicist, had been introduced to Sanskrit, the ancient Indian language, and subsequently the Gita, as a teacher in Berkeley years before. More than 2,000-year-old, Bhagavad Gita is part of the Mahabharata - one of Hinduism's greatest epics - and at 700 verses, the world's longest poem.

Now, hours before an event that would change history, the "father of the atomic bomb" relieved his tension by reciting a stanza he had translated from Sanskrit:

In battle, in forest, at the precipice of the mountains

On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows,

In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame,

The good deeds a man has done before defend him

As Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin write in their authoritative 2005 biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J Robert Oppenheimer, a young Oppenheimer was introduced to Sanskrit by Arthur W Ryder, a professor of Sanskrit at the University of California, Berkeley. The precocious physicist had arrived there as a 25-year-old assistant professor. Over the next few decades, he helped build one of the "greatest schools of theoretical physics" in the US.

Ryder, a Republican and a "sharp tongued iconoclast", was fascinated by Oppenheimer. For his part, Oppenheimer regarded Ryder as a "quintessential intellectual", a scholar who "felt and thought and talked as a stoic". The young scientist's textile importer father agreed, saying Ryder was a "remarkable combination of austereness through which peeps the gentlest soul".

Oppenheimer - played by actor Cillian Murphy in the biopic - also regarded Ryder as a rare person who had "a tragic sense of life, in that they attribute to human actions the completely decisive role in the difference between salvation and damnation".

Soon, Ryder was giving Oppenheimer private lessons in Sanskrit on Thursday evenings. "I am learning Sanskrit," the scientist wrote to his brother Frank, "enjoying it very much and enjoying again the sweet luxury of being taught".

Many of his friends found his new obsession with an Indian language odd, Oppenheimer's biographers noted. One of them, Harold F Cherniss, who introduced the scientist to the scholar, thought it made "perfect sense" because Oppenheimer had a "taste of the mystical and the cryptic".

So Oppenheimer's knowledge of Sanskrit and the Gita is clearly germane to telling his story. But some right wing Hindus have complained - particularly about the sex scene with lover Jean Tatlock, played by Florence Pugh - saying the film is an attack on their religion and demanding cuts.

But India's film censors found no problem with it and at the box office it's the Hollywood hit of the year in India, faring better than Barbie since the two blockbusters opened on Friday.

There's no doubt Oppenheimer was a widely well-read man - he took courses in philosophy, French literature, English, history, and briefly considered studying architecture, and even becoming a classicist, poet or painter. He wrote poems on "themes of sadness and loneliness", and identified with TS Eliot's "sparse existentialism" in The Waste Land.

"He liked things that were difficult. And since almost everything was easy for him, the things that really would attract his attention were essentially the difficult," Cherniss said.

With his facility for languages - Oppenheimer had studied Greek, Latin, French and German and learned Dutch in six weeks - it "wasn't really long before" he was reading the Bhagavad Gita. He found it "very easy and quite marvellous" and told friends that it was the "most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue". In his bookshelf was a pink-covered copy of the book that Ryder had gifted him; and Oppenheimer himself gifted copies to his friends.

The biographers write that the scientist was so "enraptured by his Sanskrit studies" that in 1933 when his father brought him a Chrysler, he named it Garuda, after the giant bird God in Hindu mythology.

In spring of that year, Oppenheimer had written a rather florid letter to his brother explaining why discipline and work had always been his guiding principles. It pointed to the fact that he was enthralled by eastern philosophy.

He wrote: "through discipline, though not through discipline alone, we can achieve serenity, and a certain small but precious measure of freedom from the accidents of incarnation… and that detachment which preserves the world it renounces". Only through discipline, he added, is it possible to "see the world without the gross distraction of personal desire, and in seeing so, accept more easily our earthly privation and its earthly horror".

"In the late twenties, Oppenheimer seemed to be searching for an earthly detachment; he wished, in other words to be engaged as a scientist with the physical world, and yet detached from it," his biographers write.

"He was not seeking to escape to a purely spiritual realm. He was not seeking religion. What he sought was peace of mind. The Gita seemed to provide precisely the right philosophy for an intellectual keenly attuned to the affairs of men and the pleasures of the senses."

One of his favourite Sanskrit texts was the Meghaduta, a lyric poem written by Kalidasa, one of the greatest poets in the language. "The Meghaduta I read with Ryder, with delight, some ease and great enchantment," he wrote to his brother, Frank.

Why did Oppenheimer turn to Gita and its notions of karma, destiny and earthly duty so fervently? His biographers hazard a guess: "Perhaps the attraction Robert felt to the fatalism of the Gita was at least stimulated by a late blooming rebellion against what he had been taught as a youth", alluding to his early association with the Ethical Culture Society, an "uniquely American offshoot of Judaism that celebrated rationalism and a progressive brand of secular humanism".

To be sure, Oppenheimer was not alone in admiring the Hindu text. Henry David Thoreau wrote about immersing himself in the "stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial". Heinrich Himmler was an admirer. Mahatma Gandhi was an ardent follower. And WB Yeats and TS Eliot, two poets Oppenheimer admired, had read the Mahabharata.

The sight of the giant orange mushroom cloud rising in the skies after the first atomic bomb test had led Oppenheimer to return to the Gita again. The bombs that were eventually dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II had killed tens of thousands of people.

"We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent," he told NBC in a 1965 documentary.

"I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu [a principal Hindu deity] is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, "Now I have become death, the destroyer of the worlds'. I suppose we all thought that, one way or another."

A friend of the scientist said the quote sounded like one of Oppenheimer's "priestly exaggerations".

Yet, the enigmatic scientist remained profoundly influenced by it.

When the editors of The Christian Century asked the scientist once to share the books that most profoundly influenced his philosophical outlook, Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal held the top spot. And the Bhagavad Gita took the second position.'

#Oppenheimer#Cillian Murphy#Bhagavad Gita#Christopher Nolan#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#The Christian Century#Baudelaire#Les Fleus du Mal#Arthur W Ryder#Harold F. Cherniss#Jean Tatlock#Florence Pugh#T.S Eliot#The Waste Land#Frank Oppenheimer#WB Yeats

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Grass." From the Annapurna Upanishad, the Exploration of the Mysteries of the Queen of Foods.

V-8. ‘Undetermined by space and time, beyond the purview of ‘is’ and ‘is not’, there is but Brahman, the pure indestructible Spirit, quiescent and one; there is nothing else’.

V-9. Thus thinking, with a body at once present and absent, be (liberated), the silent man, uniform, with quiescent mind delighting in the Self.

V-10. There is neither mind -stuff nor mind; neither nescience nor Jiva. Manifest is the one Brahman alone, like the sea, without beginning or end.

V-11. The illusory perception of mind, etc., continues as long as the I[1]sense is bound up with the body, objects are mistaken for the Self, and the sense of possession, expressed as ‘this is mine’, persists.

V-12. Sage ! Illusory perceptions of mind, etc., vanish for one who, through introversion, internally burns up, in the fire of the Spirit, the dry grass that is this three-fold world.

The biggest patch of dry grass in the mind is what happens after we die. We know there is a place beyond this one and in it resides the Holy Ghost, who is also superimposed on this world. The struggle to find a way to meet Him on His own turf has consternated mankind since His origins. The masters who wrote the Upanishads say one has to perceive Him here first, and get to know Him here else He will not know you well enough to invite you into the next realm.

The Upanishad says the answer is to clear the mind, think of nothing but what is necessary. In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna “The Scourge of the Wicked” says:

BG 6.34-36: The mind is very restless, turbulent, strong and obstinate, O Krishna. It appears to me that it is more difficult to control than the wind.

Lord Krishna said what you say is correct; the mind is indeed very difficult to restrain. But by practice and detachment, it can be controlled. Yoga is difficult to attain for one whose mind is unbridled. However, those who have learnt to control the mind, and who strive earnestly by proper means, can attain perfection in Yoga. This is My opinion.

Everyone thinks if they sit and squint their eyes shut hard enough, they will see Jesus or Shiva dancing around in there, but that is not the point of yoga. The point of yoga is to force the mind and body to calm down and extricate themselves from their selfish urges so one can be motivated by truth alone. Full availability to real life is the only way to see God as He is. Who cannot see God here on earth shall not see Him in heaven.

What follows Right Vision is Right Action which we discussed in the prior frame.

0 notes

Text

The Role of Guru in Spiritual Progress According to Shrimad Bhagavatam and Bhagavad Gita

In this blog post, we will discuss the role of Guru in spiritual progress according to the Shrimad Bhagavatam and Bhagavad Gita. Some people question the acceptance of Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj as their Guru, as he is only visible on television screens. However, the scriptures make it clear that only a well-versed and enlightened soul can be qualified as a Guru. Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj was a foremost scholar of all the Vedas and scriptures of this age, and his teachings are capable of dispelling ignorance. The Guru instills discipline and educates the aspirant in scriptural concepts and principles, which in turn purifies the mind of the aspirant. The purification process is entirely in the hands of the aspirant, and the Guru can only guide and eliminate obstacles.

As is stated in the Shrimad Bhagavatam 113.21 and Bhagavad Gita 4.34, only a shrotriya Brahmanishtha enlightened soul (i.e. one who is well-versed in the scriptures and has the practical realisation of God) is qualified to be called Guru and capable of taking you to your supreme goal. Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj was the foremost scholar of all the Vedas and scriptures of this age. His discourses, sankirtans, and oceanic literary works are capable of dispelling the darkness of ignorance like thousands of bright suns, which can still be read and heard by anyone.

A Guru first instills in the aspirant the discipline required to perform devotional practice by educating him in scriptural concepts and principles, tattva jnana. Armed with this knowledge, and practicing devotion under the guidance of the Guru, the mind of the aspirant in time. Begins to purify. When this process of purification is complete, the Guru bestows divine love, which is in fact the only true initiation. How long this purification of the mind takes is entirely in the hands of each respective aspirant; it could be one life or many lifetimes. The determining factor is the speed of devotional practice which can only be performed by the aspirant himself. Guru can impart tattva jnana, guide the aspirant regarding the correct performance of devotional discipline and eliminate any doubts or obstacles that would otherwise hamper the aspirant’s progress along the path, etc. However, performing devotional discipline is the sole responsibility of the aspirant and is in fact their true duty.

So proceed on the path prescribed by him and he will grace you when your mind is completely purified. He will do his duty first and we should do ours. Listen to his discourses time and time again. Study his literature and imbibe his teachings and make it your driving force. Strengthen your faith that his divine discourses (through CD or DVD) will guide you after entering your mind. Try it and see; you will surely be benefited.

It is therefore clear that even today an aspirant can practice devotion according to Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj’s teachings and definitely be benefited. First of all, an aspirant needs correct spiritual knowledge and to know the correct path to be followed. Anyone who listens to Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj’s discourses will know what the supreme path is to attain the supreme goal. It is then up to the aspirant to practice devotion with the firm. Faith that Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj will guide him if his thirst is genuine.

He wrote I am always with you countless times and he will be right up to the attainment of God and even after that. We will again have his association in the divine abode of Lord Krishna. The one he adopts can never desert him.

In conclusion, the role of the Guru in spiritual progress is significant, according to the Shrimad Bhagavatam and Bhagavad Gita. Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj was a well-versed and enlightened soul and his teachings are still available through his discourses, sankirtans, and literature. It is up to the aspirant to practice devotion with firm faith in the Guru’s guidance, and the purification process depends entirely on the aspirant’s efforts. The Guru can only guide and eliminate obstacles but performing devotional discipline is the sole responsibility of the aspirant. We should follow the path prescribed by the Guru and imbibe his teachings, which can serve as a driving force towards our supreme goal.

youtube

#Jagadguru Shri Kripalu Ji Maharaj#Jagadguru Kripalu Parishat#kripalu maharaj#kripalu maharaj books#kripalu maharaj news#kripalu maharaj reviews#kripalu maharaj followers#Kripalu maharaj book#Kripalu maharaj story#Kripalu maharaj articles#Kriplau maharaj motivation#bhagwatgeeta#Shrimad Bhagavad Gita by kripalu maharaj#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

हमें भगवद गीता ( Bhagavad Gita ) क्यों पढ़नी चाहिए?

हमें भगवद गीता ( Bhagavad Gita ) क्यों पढ़नी चाहिए?

Bhagavad Gita : भगवद गीता पढ़ने के क्या लाभ हैं? वर्तमान दुनिया में मनुष्यों की कथा।

Bhagavad Gita

1. हाथी पिछले कर्म का प्रतिनिधित्व करता है।

2. सांप भविष्य के कर्म का प्रतिनिधित्व करता है।

3. वृक्ष की शाखा वर्तमान जीवन है।

4. सफेद और काले चूहे – दिन और रात – वर्तमान जीवन को खा रहे हैं।

5. शहद कंघी माया और भौतिक जीवन है। जबकि महाविष्णु ने उन्हें मोक्ष देने के लिए और पुनर्जन्म के दुख के इस…

View On WordPress

#7 - day course on bhagavad gita#bhagavad#Bhagavad Gita#bhagavad gita chapter 1#bhagavad gita in english#bhagavad gita lessons#bhagavad gita meaning#bhagavad gita online#bhagavad gita significance#bhagavad gita slokas#bhagavad gita telugu#bhagavad gita war#die bhagavad gita#learn bhagavad gita#sreemad bhagavad gita telugu#the bhagavad gita#the bhagavad gita summary#what is the bhagavad gita#who first wrote the bhagavad gita?#who wrote the bhagavad gita

0 notes

Text

Plutonium and Poetry: Where Trinity and Oppenheimer's Reading Habits Met - Patty Templeton, Digital Archivist, National Security Research Center

The Lab’s first director, J. Robert Oppenheimer, was a man of sonnets and scientific synthesis.

Oppenheimer’s work at Los Alamos was defined not only by physics and administrative skill, but also by a life philosophy inspired, in part, by literature. The Trinity test, which took place 76 years ago on July 16 in the New Mexico desert, epitomizes this.

Known as one of the greatest scientific achievements ever, the successful detonation of the world’s first nuclear weapon marked the dawn of the Atomic Age. Created in just 27, albeit harrowing, months, Oppenheimer and his team at the Los Alamos Lab worked nonstop on this clandestine effort to help end World War II.

As he had done throughout his life, Oppenheimer continued to foster his love of literature during the Manhattan Project. Two of his influences were John Donne and the Hindu scripture "Bhagavad-Gita." Oppenheimer recalled both during the Trinity test.

John Donne and Trinity

Seventeenth-century poet John Donne was one of Oppenheimer’s favorite writers and an inspiration during his work with the Manhattan Project.

In 1962, Manhattan Project leader Gen. Leslie Groves wrote to Oppenheimer to ask about the origins of the name Trinity. According to a copy of the letter that is a part of the collections of the Lab’s National Security Research Center,

Oppenheimer said, “Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love.” Oppenheimer then quoted the sonnet “Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness” about a man unafraid to die because he believed in resurrection.

Oppenheimer continued, “That still does not make a Trinity, but in another, better known devotional poem Donne opens, ‘Batter my heart, three person’d God.’ Beyond this, I have no clues whatever.”

“Batter my heart” expresses the paradox that by being chained to God, the narrator can be set free. A great force could enthrall the narrator to do greater good. Richard Rhodes, who wrote the book "The Making of the Atomic Bomb," proposed that “the bomb for [physicist Niels] Bohr and Oppenheimer was a weapon of death that might also end war and redeem mankind.”

===

Finding meaning

Poetry was ever-present in Oppenheimer’s letter writing and in his reactions to current events. We know that, according to the book "American Prometheus," by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, before the Trinity test, late at night in the base camp mess hall, Oppenheimer sipped coffee, rolled smokes and read French poet Charles Baudelaire.

T.S. Eliot, a poet Oppenheimer admired and hosted later as the director of the Institute for Advanced Study, famously wrote:

“Do I dare

Disturb the universe?”

Oppenheimer surely did.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Famous historical figures

A list of famous people throughout history. These famous historical figures are chosen from a range of different cultures and countries. They include famous spiritual figures, politicians and writers who have helped to shape human history.

BCE

Sri Ramachandra (c. 5114 BCE) Rama was a model king of Ayodhya who lived according to the dharma. He went to Sri Lanka to fight Ravana who had captured his wife, Sita. Rama is considered an incarnation of Vishnu in Hindu mythology.

Sri Krishna (c. BCE) – Spiritual Teacher of Hinduism. Sri Krishna gave many discourses to his disciple Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. These discourses were written down in the Bhagavad Gita.

Ramses II (1303 BCE – 1213 BCE) – Ramses or Ramesses was the third Egyptian Pharaoh, ruling between 1279 BC – 1213 BC. Ramses the Great consolidated Egyptian power, through military conquest and extensive building.

Homer (8th Century BC) Homer is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Two classics of Greek literature. His writings form a significant influence on Western literature.

Cyrus the Great (600 – 530 BC) was the founder of the Persian (Achaemenid) Empire. Cyrus conquered the empires of Media, Lydia and Babylonia, creating the first multi-ethnic state which at its peak accounted for around 40% of the global population.

Lord Buddha (c 563 – 483 BC) Spiritual Teacher and founder of Buddhism. Siddhartha was born a prince in northern India. He gave up the comforts of the palace to seek enlightenment. After attaining Nirvana, he spent the remainder of his years teaching.

Confucius (551 – 479 BC) – Chinese politician, statesman, teacher and philosopher. His writings on justice, life and society became the prevailing teachings of the Chinese state and developed into Confucianism.

Socrates (469 BC–399 BC) – Greek philosopher. Socrates developed the ‘Socratic’ method of self-enquiry. He had a significant influence on his disciples, such as Plato and contributed to the development of Western philosophy and political thought.

Plato (424 – 348 BC) – Greek philosopher. A student of Socrates, Plato founded the Academy in Athens – one of the earliest seats of learning. His writings, such as ‘The Republic’ form a basis of early Western philosophy. He also wrote on religion, politics and mathematics.

Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC) – Greek philosopher and teacher of Alexander the Great. Aristotle was a student of Plato, but he branched out into empirical research into the physical sciences. His philosophy of metaphysics had an important influence on Western thought.

Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BC) – King of Macedonia. He established an Empire stretching from Greece to the Himalayas. He was a supreme military commander and helped diffuse Greek culture throughout Asia and northern Africa.

Archimedes (287 B.C – 212) Mathematician, scientist and inventor. Archimedes made many contributions to mathematics. He explained many scientific principles, such as levers and invented several contraptions, such as the Archimedes screw.

Ashoka (c 269 BCE to 232 BCE) – One of the greatest Indian rulers. Ashoka the Great ruled from 269 BC to 232 BC he embraced Buddhism after a bloody battle and became known for his philanthropism, and adherence to the principles of non-violence, love, truth and tolerance.

Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) As military commander, Caesar conquered Gaul and England extending the Roman Empire to its furthest limits. Used his military strength to become Emperor (dictator) of Rome from 49 BC, until his assassination in 44BC.

Augustus Caesar (63 BC-AD 14) – First Emperor of Rome. Caesar (born Octavian) was one the most influential leaders in world history, setting the tone for the Roman Empire and left a profound legacy on Western civilisation.

Cleopatra (69 -30 BC) The last Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. Cleopatra sought to defend Egypt from the expanding Roman Empire. In doing so, she formed relationships with two of Rome’s most powerful leaders Marc Anthony and Julius Caesar.

AD

Jesus of Nazareth (c.5BC – 30AD), Jesus of Nazareth, was a spiritual teacher, and the central figure of Christianity. By Christians, he is considered to be the Messiah predicted in the Old Testament.

St Paul (5 – AD 67) – Christian missionary. St Paul was Jewish and a Roman citizen who converted to Christianity. His writings and teachings did much to define and help the spread of Christianity.

Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180) – Roman Emperor and philosopher. He is considered the last of the five good Emperors. His Meditations are a classic account of Stoic philosophy.

Emperor Constantine (272 – 337) First Roman Emperor to embrace Christianity. He called the First Council of Nicaea in 325 which clarified the Nicene Creed of Christianity.

Muhammad (570 – 632) Prophet of Islam. Muhammad received revelations which form the verses of the Qur’an. His new religion unified Arabia under the new Muslim religion.

Attila the Hun (5th Century) Ruler of the Huns who swept across Europe in the Fifth Century. He attacked provinces within the Roman Empire and was Rome’s most feared opponent.

Charlemagne (742 – 814) – King of Franks and Emperor of the Romans. Charlemagne unified Western Europe for the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire. He provided protection for the Pope in Rome.

Genghis Kahn (1162 – 1227) – Leader of the Mongol Empire stretching from China to Europe. Genghis Khan was a fierce nomadic warrior who united the Mongol tribes before conquering Asia and Europe.

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204) – The first Queen of France. Eleanor influenced the politics of western Europe through her alliances and her sons Richard and John – who became Kings of England.

Saladin (1138 – 1193) – Leader of the Arabs during the Crusades. He unified Muslim provinces and provided effective military opposition to the Christian crusades.

Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274) Influential Roman Catholic priest, philosopher and theologian.

Marco Polo (1254 – 1324) Venetian traveller and explorer who made ground-breaking journeys to Asia and China, helping to open up the Far East to Europe.

Johann Gutenberg (1395 – 1468) – German inventor of the printing press. Gutenberg’s invention of movable type started a printing revolution which was influential in the Reformation.

Joan of Arc – (1412-1431) – French saint. Jean d’Arc was a young peasant girl who inspired the Dauphin of France to renew the fight against the English. She led French forces into battle.

Christopher Columbus (1451 – 1506) – Italian explorer who landed in America. He wasn’t the first to land in America, but his voyages were influential in opening up the new continent to Europe.

Leonardo da Vinci ( 1452 – 1519) – Italian scientist, artist, and polymath. Da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper. His scientific investigations covered all branches of human knowledge.

Guru Nanak (1469 1539) Indian spiritual teacher who founded the Sikh religion. Guru Nanak was the first of the 10 Sikh Gurus. He travelled widely disseminating a spiritual teaching of God in everyone.

Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) – A key figure in the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther opposed papal indulgences and the power of the Pope, sparking off the Protestant Reformation.

Babur (1483 – 1531) – Founder of the Moghul Empire on the Indian subcontinent. A descendant of Genghis Khan, he brought a Persian influence to India.

William Tyndale (1494 – 1536) – A key figure in the Protestant Reformation. Tyndale translated the Bible into English. It’s wide dissemination changed English society. He was executed for heresy.

Akbar (1542 – 1605) – Moghul Emperor who consolidated and expanded the Moghul Empire. Akbar also was a supporter of the arts, culture and noted for his religious tolerance.

Sir Walter Raleigh (1552 – 1618) – English explorer who made several journeys to the Americas, including a search for the lost ‘Eldorado.’

Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) – Astronomer and physicist. Galileo developed the modern telescope and, challenging the teachings of the church, helped to prove the earth revolved around the sun.

William Shakespeare (1564- 1616) English poet and playwright. Shakespeare’s plays, such as Hamlet, Macbeth and Othello have strongly influenced English literature and Western civilisation.

Rene Descartes (1596 – 1650) Dubbed the father of modern philosophy, Descartes was influential in a new rationalist movement, which sought to question basic presumptions with reason.

Oliver Cromwell (1599 – 1658) – British Parliamentarian. Cromwell led his new model army in defeating King Charles I and creating a new model of government.

Voltaire (1694 – 1778) – French philosopher. Voltaire’s biting satire helped to create dissent in the lead up to the French revolution.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) – English mathematician and scientist. Newton laid the foundations of modern physics, with his laws of motion and gravity. He made extensive scientific investigations.

Eighteenth Century

Catherine the Great (1729 – 1796) – Russian Queen during the Eighteenth Century. During her reign, Russia was revitalised becoming a major European power. She also began reforms to help the poor.

George Washington (1732 – 1799) – 1st President of US. George Washington led the American forces of independence and became the first elected President.

Tom Paine (1737- 1809) English-American author and philosopher. Paine wrote‘Common Sense‘ (1776) and the Rights of Man (1791), which supported principles of the American and French revolutions.

Thomas Jefferson (1743- 1826) 3rd President of US. Author of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson passed laws on religious tolerance in his state of Virginia and founded the University of Virginia.

Mozart (1756 – 1791) – Austrian Music composer. Mozart’s compositions ranged from waltzes to Requiem. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest musical geniuses of all time.

Nineteenth Century

William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833) – British MP and campaigner against slavery. Wilberforce was a key figure in influencing British public opinion and helping to abolish slavery in 1833.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821) – French military and political leader. Napoleon made France a major European power and meant his Napoleonic code was widely disseminated across Europe.

Simon Bolivar (1783 – 1830) – Liberator of Latin American countries. Bolivar was responsible for the liberation of Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela and Colombia.

Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865) 16th President of US. Lincoln led the northern Union forces during the civil war to protect the Union of the US. During the civil war, Lincoln also promised to end slavery.

Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882) – Developed theory of evolution. His book ‘The Origin of Species’ (1859) laid the framework for evolutionary biology and changed many people’s view of life on the planet.

Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) Principle Marxist philosopher. Author of Das Kapitaland The Communist Manifesto. (with F.Engels) Marx believed that Capitalist society would be overthrown by Communist revolution.

Queen Victoria (1819 – 1901) – Queen of Great Britain during the Nineteenth Century. She oversaw the industrial revolution and the growth of the British Empire.

Louis Pasteur (1822 – 1895) – French chemist and Biologist. Pasteur developed many vaccines, such as for rabies and anthrax. He also developed the process of pasteurisation, making milk safer.

Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910) – Russian writer and philosopher. Tolstoy wrote the epic ‘War and Peace’ Tolstoy was also a social activist – advocating non-violence and greater equality in society.

Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931) – Inventor and businessman. Edison developed the electric light bulb and formed a company to make electricity available to ordinary homes.

Twentieth Century

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900) – Irish writer. Wilde’s plays included biting social satire. He was noted for his wit and charm. However, after a sensational trial, he was sent to jail for homosexuality.

Woodrow Wilson (1856 – 1924) – President of US during WWI. Towards the end of the war, Wilson developed his 14 points for a fair peace, which included forming a League of Nations.

Mahatma Gandhi (1869 – 1948) – Indian nationalist and politician. Gandhi believed in non-violent resistance to British rule. He sought to help the ‘untouchable’ caste and also reconcile Hindu and Muslims.

V. Lenin (1870-1924) – Born in Ulyanovsk, Russia. Lenin was the leader of Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution in 1917. Lenin became the first leader of the Soviet Union influencing the direction of the new Communist state.

The Wright Brothers (Orville, 1871 1948) – developed the first powered aircraft. In 1901, they made the first successful powered air flight, ushering in a new era of air flight.

Winston Churchill (1874 – 1965) Prime Minister of Great Britain during the Second World War. Churchill played a key role in strengthening British resolve in the dark days of 1940.

Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967) – West German Chancellor post world war II. Adenauer had been an anti-nazi before the war. He played a key role in reintegrating West Germany into world affairs.

Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955) – German / American physicist. Einstein made groundbreaking discoveries in the field of relativity. Einstein was also a noted humanitarian and peace activist.

Ataturk (1881-1938) – founder of the Turkish Republic. From the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, Ataturk forged a modern secular Turkish republic.

A Little History of the World

A Little History of the World: Illustrated Edition at Amazon – by E. H. Gombrich

John M Keynes (1883 – 1946) Influential economist. Keynes developed a new field of macroeconomics in response to the great depression of the 1930s.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) US President (1932-1945) Roosevelt led the US through its most turbulent time of the great depression and World War II.

Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945) Dictator of Nazi Germany. Hitler sought to conquer Europe and Russia, starting World War Two. Also responsible for the Holocaust, in which Jews and other ‘non-Aryans’ were killed.

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) – First Indian Prime Minister. Nehru came to power in 1947 and ruled until his death in 1964. He forged a modern democratic India, not aligned to either US or the Soviet Union.

Dwight Eisenhower (1890 – 1969) – Supreme Allied Commander during the Normandy landings of World War II. Eisenhower also became President from 1953-1961.

Charles de Gaulle (1890- 1970) French politician. De Gaulle became leader of the ‘Free French’ after the fall of France in 1940. Became President after the war, writing the constitution of the 5th Republic.

Chairman Mao (1893 – 1976) Mao led the Chinese Communist party to power during the long march and fight against the nationalists. Mao ruled through the ‘cultural revolution’ until his death in 1976.

Mother Teresa (1910-1997) – Catholic nun from Albania who went to India to serve the poor. Became a symbol of charity and humanitarian sacrifice. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

John F. Kennedy (1917 – 1963) – US President 1961-1963. J. F.Kennedy helped to avert nuclear war during the Cuban missile crisis. He also began to support the civil rights movement before his assassination in Dallas, November 1963.

Nelson Mandela (1918 – ) The first President of democratic South Africa in 1994. Mandela was imprisoned by the apartheid regime for 27 years, but on his release helped to heal the wounds of apartheid through forgiveness and reconciliation.

Pope John Paul II (1920 – 2005) – Polish Pope from 1978-2005. Pope John Paul is credited with bringing together different religions and playing a role at the end of Communism in Eastern Europe.

Queen Elizabeth II (1926 – ) British Queen from 1952. The second longest serving monarch in history, Elizabeth saw six decades of social and political change.

Martin Luther King (1929 – 1968) Martin Luther King was a powerful leader of the non-violent civil rights movement. His 1963 speech ‘I have a dream’ being a pinnacle moment.

14th Dalai Lama (1938 – ) Spiritual and political leader of Tibetans. The Dalai Lama was forced into exile by the invading Chinese. He is a leading figure for non-violence and spirituality.

Mikhail Gorbachev (1931 – ) Leader of the Soviet Union. Oversaw transition from Communism in Eastern Europe to democracy. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990.

Muhammad Ali (1942- ) American boxer. Muhammad Ali had his boxing license removed for refusal to fight in Vietnam. He became a leading figure in the civil rights movement.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan. “Famous historical people”, Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net, 18/12/2013. Published 1 March 2018. Last updated 7 July 2019

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Discussion of One Approach to a Universal Characteristic

I have felt inspired yesterday to make this attempt as a text post on Tumblr. By the subject’s weighty history and definition, it should by no means be an easy endeavor. However, there are two individuals from my readings that have inspired me, named John Locke and George Polya. Although I own both of the texts that interest me by these men, I have not read those specific texts unfortunately. Another influence was the eloquence of Euclid’s axioms, indeed I have not read the Elements either except for like the first page. I tend to become distracted very easily, and this is not something that I am very proud of.

Now I must reveal my passion for the works of Ramon Llull. He was the guy behind the most complete version of Characteristica Universalis, but that is only because he managed to inspire Leibniz to come up with his Characteristica, which was never really worked on or implemented, and the system that Llull created is called Ars Magna, in four distinct stages. The term Ars Magna itself with regards to Llull refers to the Ternary Art, which refers to the wheels or volvelles that he used have elements or principles being divisible by 3. Furthermore this also by coincidence is the third phase of the art, but the phase and divisibility of the wheels are distinct things.

Enough of Llull. Leibniz is really the only person to be regarded here, as it can be assumed that he wished to update Ars Magna to the science of the time and his own distinguished opinion. That being said, he never managed to create such a thing, but merely wrote to his collaborators and associates about what a proper implementation of this Universal Characteristic would look like. His letters are somewhere in the order of magnitude of 10^5, which is a complicated way of saying 10,000. Indeed I do not remember the estimated number from the Wiki, but I do believe it was something like 30,000.

By the way, the Wiki does list 21 different attempts at Characterica Universalis, which is the number if I recall correctly, that this scholarly text on Llull mentioned that the man had written this many different version of his system. Quite interesting, but I cannot lower myself into base numerology. That has been superseded. To return to Ramon Llull for a moment, the man allegedly got his system from the Sufis. This precursor system is called Zairja, and there are a couple of texts available on that subject, one written by modern scholars and another written by a Tunisian historian who wrote the Muqaddimah. A hint for those of you curious about the latter text: The chapter about Zairja is in the third volume of that text, and is available on the Internet Archive.

Back to Leibniz; for some reason essay writing is quite tiring. From what we can discern about what he stated that this system would look like, well I have some bad news. Leibniz simply took the diagram that Empedocles created in antiquity and said “There.” What I mean by this is that Leibniz just took the four elements and their supposed connections, in doing so adding another four nodes to the diagram, and being content with drawing lines between said nodes in order to ratiocinate (think) on paper. Anyone can tell that this is follysome since we now know for a fact that the Classical Elements theory is rubbish. In fact, I have a hot take that it was not only responsible for the idea of “race,” but also the idea of depression. I have created an acronym for the various iterations of Classical Element theory, that is “EHTR” (pronounced ‘ether’) or Element-Humor-Temperament-”Race.” Indeed this may come as quite a shock everyone, but Kant the philosopher was really racist and decided to rank the “races.” I am not going to get into this, but I will say that it may have become esoteric or something through the likes of Manly P. Hall, who mentioned the same scheme Kant used, albeit reordering some things, after the latter mapped it to an analogy about the caste system mentioned in the Bhagavad Gita. I can feel the cancelation brewing already.

There are probably many different ways to attain this Universal Characteristic. I find that I have provided enough introductory information on this subject, so let us move on to the main part of this essay. Unfortunately, this whole thing was spurred on by a feeling of grandiosity, so I really don’t know how valid my intuition is. Furthermore I forgot what it was that I could use to implement Charicterica Universalis. That being said, I think it was along the lines of a study of analogy, using mathematics, so that we could potentially describe the various processes that underlie reality. The other part was a return to metaphysics proper, or the three general distinguishing features of it according to some textbook, those features being categorization (which is what I consider to be important in particular with regards to this endeavor), thinking and a sense of supremacy regarding the method. Personally I really don’t think that the last one means much, and is in fact a detriment to updating philosophy as should be periodically done in my opinion. Science will always push the boundaries.

I am going to split the remainder of this essay into three parts: The first part will be about analogy; the second, categorization; and thirdly an obscure paradox that I came up with last night, as a bonus for making it to the end of the essay. You could just skip to the paradox, if you would like, in fact I will bold the title for you, in case I have wasted too much of your time and am boring you.

On Analogy

I envision analogy as not something fundamental, as the man who wrote Zen and the the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance stated that analogy is irreducible to sub-elements; and I argue against that position taken by the author of that text. I am honestly getting tired of writing and I have written the later parts of this essay before I wrote this part, so here goes nothing.

In the next part I briefly mention knot and graph theory. I envision analogies as graphs, as I was inspired by Schrödinger’s book What is Life that the genetic material was a crystal. Not true, but why could this crystal represent mimesis, as opposed to “genesis?” (Genesis as in genes, an improper way to say that mind you.) Yes, I really think that this is the case, but it does sound kind of crazy now that I have it on paper after having it in my mind for a few years. I don’t know. I dislike the designation that Dawkins created for such things, the “meme” which he literally took from some German scientist with the same first name, and removed the ‘n’ in mneme to create this Internet garbage we see today.

Then there are the developments with the idea of metaphor. I don’t really feel like getting into these because I am too tired and I keep making typing mistakes. Just know that it is possible to limit portions of the structure of the analogy to make it more congruent with other analogies or structures. Lastly, it really feels like the literary criticism movement is starting to claim all of the universe as its “text.” That is a portion of Structuralism, at least, according to PhilosophyTube. She stated that Structuralism started as literary criticism, and what do we as human beings do? Why we map the text to the whole of the universe. Some could argue that is a kind of metaphysics were it to be loosely understood. ...

On Categorization

The general gist of what I am thinking of here is that Ars Magna’s major issue is that it is not chaotic enough, if that makes any sense. What I am attempting to get at here is the thing about the questions generated in that system solely referring to the statements created. There is no architecture or complexity there to be studied and afterwards engineered, as it is just base multiplication to generate the questions. What I would like, is for the creation of the questions to be irreversible and chaotic, indeed those are separate things, much like the weather. Knot theory, or graph theory would come into play here, I am not sure which but that is what my intuition is telling me. Also, many statements could be superimposed to generate a set of questions, or a single question. Hopefully my mathematical studies will enable me to investigate this further in the future.

It must be stated now that the whole category term does apply in my opinion to Ars Manga. This is because the system abstracts the categories into a table of about 54 “elements” which are then combined a second time to produce very short strings of text, for instance “BCD.” Of course, the strings could very well be longer, and could incorporate more intricacy in this manner, but it is really the interaction between all of these strings which constitutes the architecture of the system, although this is done in a manner contrary to the mainstream Lullists, which is an anachronism, really.

Case in point the categories must translate into natural phenomena and vice versa. At the same time, if the categories were generative, then they must be irreversible in order to be as intricate as possible. The sky is the limit with this, “New Lullism.” I don’t feel like explaining any more, but if someone wants me to tell them about why the standard categories must be reversible, and the generative categories the reverse, then I will explain this another day. Indeed, it may be a false distinction; there may very well be four types of category system, that is:

Standard reversible;

Generative reversible (Ars Magna);

Standard irreversible;

Generative irreversible.

That is all for this part.

The Paradox

There is a possibility for a Universal Library, but the one available on the Internet is not feasible for conducting research on, because it is an art website and is not powerful enough to locate texts and be practical. I am talking about an implementation for the Universal Library called the Library of Babel. You can visit the website at libraryofbabel.info. I do not have the energy to disclose the theory behind this whole thing right now, but on request I will write about it another day.

The mathematical constant “pi” supposedly does not repeat. Yet there is a trichotomy to be established here, when the constant is juxtaposed with the Universal Library, either;

1). The Universal Library is effected by Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem (was stated by two separate mathematics professors to likely be the case);

2). Pi does indeed repeat minute portions of itself after a significantly large computation of it is conducted, with an upper bound order of magnitude of around 10^5000. Note that this is a back-of-hand calculation;

3). Pi cannot be mapped to the Universal Library.

This trichotomy may indeed be defective as I am not trained in logic, and also I had to make up the last one as I forgot what it was. Oh well.

Thank you very much for reading all of this. Have a swell day.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Optimism of Satan

by Mitch Horowitz

See article at: https://medium.com/s/radical-spirits/the-optimism-of-satan-eea5a1a24550

A friend of mine once had the opportunity to ask the Dalai Lama a single question.

“Who was your greatest teacher?” he asked.

The exiled leader replied, “Mao Zedong.”

I once felt provoked in my own sphere by a similarly unlikely teacher — Donald Trump.

Years ago, Trump the Developer asked an interviewer: “What good is something if you can’t put your name on it?” His comment is indelibly stamped on my memory, though I confess I cannot find a source for it. Did I imagine it? The sentiment, while coarse and easily rebutted, came to haunt me.

Did Trump, the showy conman obsessed with naming rights, capture a nagging truth of human nature — a side none of us can deny or push away, other than by an act of self-regarding hypocrisy? And did I, hopefully in a more integral way, share a kernel of his outlook? Was the voice even his — or something within me?

Soon after hearing Trump’s remark, I received what struck me as a bit of ridiculous advice from the editor of an academic spiritual journal. I told him in candor that I wanted to find greater exposure for my byline. “You don’t have to put your name on everything you write,” he replied. Such a principle could ring true only in the world of abstraction.

Trump’s statement about self-exaltation, however ugly, captured half a truth. The whole truth is that our lives, as vessels for various influences — some physical, some perhaps beyond — are bound up with the world and circumstances in which we find ourselves; and within that world we must, at the stake of personal happiness, create, expand, and aspire. Whatever higher influences we feel or great thoughts we think, or are experienced by us through the influence of others, are like heat dissipated in the vacuum of space unless those thoughts are directed into a structure or receptacle. Our purpose is to be generative. Questions of attachment and non-attachment, identification and non-identification, are incidental to that larger fact.

I came to feel strongly about this several years ago when I found that my spiritual search, a path of radical ecumenism with a dedication to esoteric interests, was failing to satisfy me. I began to suspect that I was not acknowledging what I was really looking for, either in spirituality — by which I mean a search for the extra-physical — or therapy. I came face-to-face with an instinct that few people acknowledge, and would deny if they heard it spoken. But they should linger on it. Because what I discovered captures what I believe is a basic if discomforting human truth: The ethical or spiritual search, not as idealized but as actually lived, is a search for power. That is, for the ability to possess personal agency. We pray, “Thy will be done.” We mean “my will be done” — hoping that the two comport. This is why, at least in my observations after thirty years as a publisher, seeker, and historian of alternative spirituality, many seekers in both traditional and alternative faiths are ill at ease, fitful in their progress, and apt to slide from faith to faith, or to harbor multiple, sometimes conflicting, practices at once.