Talking about books where the Tumblr Fandom consists of seven people. (not spoiler free: tag-filter books)

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

✦ ⠂⠂୨ Moodboard: The Poppy War ୧˚ ༘

[Review]

#photography#travel#aesthetic#scenery#literature#books#currently reading#reading#booklr#bookworm#lit#book blog#photos#explore#moodboard#aesthetic moodboard#book moodboard#academia#booktok#rf kuang#the poppy war#tpw#tpw trilogy#the poppy war trilogy#fang runin#rin tpw#china#chinese history#zorya moodboard#zorya

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Poppy War: Thoughts & Book Review

The Poppy War by R.F. Kuang

★★★★★

★☆☆☆☆ (yes, two ratings, holy fuck)

Picking up The Poppy War, I had certain expectations. It felt like the author reached into a bag labelled “themes” and just started chucking: War! Gods! Drugs! Colonialism! Puberty! Trauma! Somewhere after chapter 10, I stopped trying to predict where it was going and just hung on like a kid on a wild carriage ride, hoping the horses knew what they were doing. Is it YA? Is it adult? Is it a disguised history textbook? Whatever it is, The Poppy War clearly has something to say. Several things. Possibly all at once. Whether it works or not … Well, that’s where things get messy.

Synopsis: Rin, a war orphan from the Second Poppy War, earns a place at the elite Sinegard military academy. She’s poor, dark-skinned, and from a rural province. An easy prey. Her classmates see her as someone who doesn’t belong. Forced to train in isolation, she eventually catches the attention of the eccentric Lore master Jiang, who introduces her to shamanic abilities linked to ancient gods. When the Federation of Mugen crashes the party with a brutal invasion, war erupts, and Rin is pulled into the Cike, a group of shamanic assassins. But as the conflict drags on, nothing is simple. Every step forward means a step further from who she used to be. Right and wrong begin to blur. Rin may have the power to burn cities, but power comes with the cost of pain.

(7900 words)

The Poppy War is a book that's difficult to classify and even harder to rate — It could easily justify both five stars and one star. So if you're here for coherent analysis, I suggest lowering your expectations. With that in mind, this review will have two parts: First, examining the book at face value, then considering its wider context, real-life connections, and reception to somehow manage finding a conclusion. The tone may shift accordingly between these sections.

The Book At Face Value

Three-Act Structure

The first part is written very YA, a mix between Harry Potter with The Karate Kid, as Rin begins her time at Singard Academy. Themes of gender issues (e.g., fertility in exchange for stopping periods, percentage of women in the military) and racism dominate the narrative. Most issues are portrayed through mean girl drama, which feels out of place compared to the rest of the book. The first part also follows the classic underdog trope of an outcast training under a quirky mentor and becoming better than everyone else. However, I did enjoy this aspect, as I always love a good training arc.

As we move into Parts Two and Three, when we leave the academy and the Third Poppy War breaks out, the tone shifts dramatically to a more traumatic narrative. Trauma porn. While the rapid progression of time made me squeak A LOT when seeing characters from Part One reappear (cue my own personal Leonardo_DiCaprio_pointing meme), my own detachment surprised me: With no time to build up a connection in Part One and the apparent plot amor, I felt oddly distant from them. This gap made it difficult in later parts to truly empathise when those very same characters experienced severe traumata. Given the sheer scale and intensity of the horrors, it's genuinely puzzling that I didn’t shed a single tear during those moments.

The book clearly struggles with its identity, wavering between a martial arts boarding school tale and a dark imperial war story. Be YA or be adult fiction? It doesn’t quite succeed at either.

One of the main and popular criticisms of this Book has been this very structure: The transition from Part One to Part Two feels jarring. It pulls you out of the story with its abruptness. I agree with this criticism. The transition simply isn’t handled well. That said, it was necessary to an extent, and the later tonal changes come across far more naturally and feel earned. By the end, I was genuinely astonished by the protagonist’s transformation from a naïve child to a mass murderer.

The reason I’m so conflicted is that I like it on a conceptual level. War doesn’t wait for you to graduate, start a new job, or settle somewhere safe — it crashes in like a thunderclap on a clear day. The story is split into setup, confrontation, and resolution, each set in a different place, which mirrors how wars move through conquest and consolidation. The characters are forced to adapt to each new stage and environment. It feels messy because it is.

I started appreciating it in later chapters:

Do you know that feeling when you’re the only one in a group unafraid to make a tough decision? Take the classic variation of the trolley problem, for example: Most people choose to pull the lever, sacrificing one to save five. But you’ve always gone against the grain, refusing to act, since ‘killing is wrong and illegal’. Rather watch five die than touch that lever. Does it make you feel special, clever even? However, it’s pretentious to take pride in choosing the other obvious path that costs lives just for your own ego.

I’ve noticed this feeling a lot in others and myself. It’s exactly what happens in The Poppy War: In Chapter 5, during a strategy class, Rin proposes flooding a dam, knowingly sacrificing many, both enemy and own, to gain an advantage. But it causes famine, disease, and years of suffering. Yet, Rin—and you as the reader—feel smart and strategic for grasping the brutal calculus of war. What’s so interesting is that later, in Chapter 26, a side character makes the same grim choice as Rin was confronted back at school. I really liked that contrast; it holds up a mirror to the reader’s utilitarian instincts, quietly calling you out for having fun with strategy, fun with war, and fun with putting people’s lives on a wage.

The shifts also capture the nature of war: The early idealism and motivation of soldiers, followed by brutal reality and inevitable tragedy. I remember vividly our discussions on the outbreak of WW1 (from the German perspective) in my history class. Many young men eagerly enlisted, seeing it as a brief adventure. They were swept up by patriotic fervour, posters glorifying sacrifice for the Fatherland. It's much like the phase Rin goes through. “We’ll be home by Christmas.” But as the war dragged on, the heavy cost became clear: Lost comrades, devastated lands, and fading hope. The book’s three-act structure brilliantly reflects this progression.

The book not only indirectly echoes this kind of history on its broad scale. At times, it quite literally reads like a history lesson. To be fair, it was needed in the beginning to lay the groundwork for the historical conflict; to set up the country’s history, events, and wars. It utilises the academic part well for this. But even later down the line, you’d often still see paragraphs in a chronological blow-by-blow account, almost like a diplomatic log, where events unfold in a very sequential, matter-of-fact way: “Day one this happened, day two that happened”. It reminded me of the way I was studying history in 10th grade. While I could imagine some readers disliking being lectured, I loved it for setting an atmosphere, even if info-dumping is often considered poor prose. It’s an issue I once mentioned in my Ninth House Review already, but here it was handled so much better!

Its use in Act One works so well because the author grounds the info-dumping within the setting: The characters are students training to become generals and tacticians. What I appreciated most about this approach was the frequent direct quoting and referencing of Sun Tzu’s Art of War in Part One. I read that book earlier this year and wrote a Review on it, arguing that it holds little relevance today and offers hardly anything applicable to modern life. It’s a relic of ancient Chinese warfare, worth reading only out of historical interest.

Kuang’s implementation, however, recontextualises the text and offers a fresh interpretation as we experience them through Rin's and her country's eyes, making these classics accessible to those modern readers—an incredibly cool and genuinely impressive feat. Similarly, she draws on strategies from other Chinese classics, such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms. I was often amazed at the creativity behind certain strategies, only to later discover through research that many were rooted in ancient military texts and classical sources! It shows Kuang's deep understanding of the texts themselves and the broader historical world she explores. That said, I do wish these references had reappeared at least once or twice later in the book to fully execute this vision.

What I found even more intriguing was that these references aren’t included merely to appear clever or pseudo-intellectual. They subtly serve to train the reader to think strategically: As Part Two leans heavily into military tactics, I found myself less emotionally invested in the story, but increasingly engaged in anticipating upcoming plot points, twists, and strategic manoeuvres. Sometimes hundreds of pages in advance, sometimes just the next line.

But such mental engagement is complicated. Predicting gruesome developments, for example as how collecting stray cats and dogs leads to a mass fire and a refugee crisis (Chapter 16), isn’t entertaining in any traditional sense. It's unsettling. A sharp, discomforting contrast. And that, I would guess, could be intentional. It underscores how easily war can be treated like a game when, in reality, it is nothing but suffering.

It draws back to the contrast in tone I mentioned earlier. The book detaches you from emotional involvement. War lands in tragedy. That’s why it works so well. Its consistency made me appreciate its structure.

A 700-page-long Book

Kuang accomplished what many authors attempt over the course of a trilogy within the span of a single book. Its progression is remarkably fast—three years pass in the first 260 pages!—But does this pace really justify the novel’s 700-page length?

The strategic warfare plotlines were okay. While I could predict much of it, simply because I was reading more attentively than ever, I didn’t mind. Those parts needed time to be built, and it was enjoyable to watch them unfold; they, at least in the story itself, felt earned.

But the emotional and personal developments dragged on: The entire novel revolves around Rin oscillating back and forth on the edge of vengeance. Her descent is teased in the first part of the book, we see it at the academy, we see it through her interactions with Jiang, and most glaringly with Altan, whose arc I was already tired of by the midpoint and just wanted to get resolved. All the small, supposedly new perspectives on opium felt increasingly flat by the end. They offered nothing that couldn’t have already been foreseen when Rin gazed out over Jiang’s poppy fields the first time around. What I mean is that the shaman’s powers come without any clear cost. Relying on the tired trope that “magic drives you mad” feels shallow and predictable. We know Rin’s sanity is a ticking time bomb, set to explode right when the plot needs it. Her internal conflict is undoubtedly a tragedy and one I usually love reading about. But stretched across 700 pages without new insight or evolving nuance, it eventually grew tiresome.

Kuang may have packed the novel with warfare and strategy to warrant the page count, but Rin’s personal arc didn’t justify it. I don’t mind a slow burn (in a general storytelling sense). But a slow burn should offer new layers with the additional time it gives itself, not just drag out the same beats. I wish I had felt more conflicted about Rin herself.

Similarly, Jiang and Altan’s ideological positions felt disappointingly too polarised. Too black and white to be truly compelling.

This might illustrate the allegedly recurring trait in Kuang’s writing: she seems to underestimate her readers’ ability to grasp complexity, often shying away from the nuance she’s clearly capable of. It’s a shame, really. Considering the ideas she had to develop on her own, the book might well have worked better as a YA novel.

Characters

Rin as an Antihero

Rin is, on paper, a brilliantly conceived character. She despises being commanded, yet can’t lead, craving someone to guide her so she doesn't have to bear the weight of failure. Everything Rin was, everything she’s become, grew out of the carnage of her people. She is fueled by anger and survival instincts more than genuine liberation, seeking revenge for Altan and her people, but ultimately fighting for self-preservation. Her spirit breaks under the empress’s betrayal and the brutal experiments she’s subjected to. With the unleashing of the Phoenix’s power and the destruction of Mugen, she became consumed by vengeance and paranoia.

Rin’s obsessive study to pass the Keju mirrors her entire journey; From her low status and lack of agency to her relentless drive and willingness to sacrifice everything—including her health and sanity—for power. The opening also brilliantly foreshadows Rin’s core flaw: Rin can memorise information but struggles with understanding. Later, when Jiang pushes her to think critically, she rejects him in favour of Altan, who doesn’t do such thing. Despite Jiang providing the most genuine care and guidance, Rin shows him little respect. In contrast, Altan verbally abuses and physically harms her, does the same to others, lies, and even kills a prisoner. Yet, Rin clings to her loyalty and love for Altan, fully aware deep down that Jiang’s advice is the wiser choice. She chooses the easy path over the right one.

Later, when she wipes out Mugen and calls it 'revenge', it mirrors Mao Zedong, whom Rin is inspired by. Her personal journey should give an educational look at him. In this case, Mao was heavily influenced in his later years by his wife (here, Altan), who encouraged him to eliminate political rivals, many of whom weren’t necessarily his enemies. It is evident that you’re supposed to dislike Rin; Mao Zedong remains one of the most ruthless and controversial figures in history: “When there is not enough to eat, people starve to death. It is better to let half the people die so others can eat their fill.” (1958-1961 during the Great Chinese Famine, resulting of 15 to 55 million deaths)

With this, the novel centres on an antihero’s descent into corruption. Rin is flawed, impulsive, and hotheaded. However, her character ultimately falls short in its execution:

The characterisation is inconsistent; she shifts between naïve and calculating strategist depending on the needs of the plot. For instance, she pushes herself to the point of self-harm to study for the Keju, yet later avoids practising when she sees Altan at her training spot. It’s a lack of clear motivation or coherent direction.

Similarly, Rin’s character flaw, which I mentioned earlier, is brilliant in concept, but not handled well: She might have destroyed Mugen, yet the army that massacred her people remains at large in Nikan! The narrative gives little reflection or critical thought to her behaviour, resulting in Rin becoming increasingly unreasonable. It’s apparent that the author wants to portray her perspective as shallow, but the execution doesn’t fully support that aim, leaving me, as the reader, confused and uninvested.

Furthermore, her primary ambition—to gain entry into the academy—is clear and compelling at first. Yet, once this goal is achieved, the narrative loses focus on her inner conflict. The story begins to feel flat after a few hundred pages as we lose connection to her. She tries to convince the reader that she desires to become a soldier and seek power. Neither true nor convincing. Rin lacks a clear philosophy behind her decisions. Unlike Mao, she had no principles.

All those patterns render the main character as the stereotypical immature YA heroine. And whether one likes it or not, Rin does unfortunately falls into several Mary Sue tropes:

She is a war orphan, having lost her parents.

She is a secret descendant of a marginalised, super-powered warrior race.

She is the last surviving member of mentioned race.

Her heritage is the source of her extraordinary abilities.

She is portrayed as the most talented in her village.

Paradoxically, she is also positioned as an underdog within the academy.

She has a training arc with a mysterious old mentor.

Despite committing genocide, she receives little to no accountability and is instead rewarded with a prestigious leadership role.

Certainly, the author’s intention was for Rin to be an unlikable character, and in the context of war, such a portrayal is entirely valid. It's not Rin’s corruption or tragedy that I find frustrating, but rather their lack of depth and substance. Would a mass murderer truly behave as Rin does? She often feels passive to the plot-driven progression. Her voice is lost.

Prose

The prose throughout the novel is deceptively simple and easy to read, yet remains impressively well-crafted! It draws you into the narrative seamlessly and adapts effortlessly to the story’s varying styles and tones.

Kuang incorporates meaningful quotes that feel authentic. They don’t feel like the author tried to be quirky and fit every Pinterest quote on her board into the text. (… unlike what you’d see in the Throne of Glass)

One of her standout strengths is the way she ends chapters with compelling cliffhangers that just make you want to turn the pages for hours on end. There wasn’t a single chapter that I would have cut.

While I did complain about Rin’s lacking character arc, the flawed one Kuang got to work with is still presented very well. So much so that, despite its third-person perspective, the story often feels as intimate as if it were told in the first person.

However, this strong focus on Rin led to many supporting characters, especially the Cike, feeling indistinguishable and voiceless. Kuang is, unfortunately, one of many authors having issues with show-don’t-tell on larger scales: Although the book repeatedly describes them as the “Bizarre Children”, their actions and personalities come across as mostly mediocre and forgettable, so that I eventually gave up trying to differentiate them. I believe the author didn’t really know what to do with the Cike … I wouldn’t have either.

Moreover, the story’s most important plot points are often told rather than shown, too. Kitay and Venka recount the events of Golyn Niis, rather than us witnessing this plot’s major downfall firsthand, and later, it’s Qara and Changhan who describe the Murui flooding. Oh, and multiple people applied to write Altan’s biography.

The Poppy War’s Real-Life Ties

Perhaps the most important context for my review is that I have no Asian heritage. I'm a white German girl who, aside from Japan’s role in WW2, received very little education on Asian history, largely due to my country’s curriculum’s strong focus on European events. (Not that we don’t spend time on US, ‘Russian’ and Australian history, but China is notably absent.) As I mentioned earlier, I read The Art of War by Sun Tzu this year, and when I came across the name “Sunzi” in The Poppy War—the pinyin spelling—I was initially confused. I turned to Google, only to find myself chasing a white rabbit wearing a waistcoat: What started as curiosity about a spelling difference made me fall into a rabbit hole of discrepancies and parallels between the book and real-world Chinese history. That process significantly shaped my understanding of the book and is essential for my opinion of it.

As Goodreads reviewer Meg, who identifies as Chinese-American (keep this in mind, it will get important later), notes, “The line between fiction and reality is always blurred. For the most violent and brutal events in human history, non-fiction books and documentaries are crucial for remembrance and understanding. Fictionalised takes on these events need to be handled carefully, but are also important. Therefore, such themes as the one in this book must be approached with care.“ While the real-world parallels in The Poppy War are intentional, it does not exempt the book from critique, especially when those parallels are not meaningfully explored or effectively integrated.

Naming Issues in Cultural Parallels

Nikan isn’t just inspired by China — it is China. Changing words minimally doesn’t make it any different:*¹

Many foods are real dishes (Eight Treasure Congee becomes Seven Treasure Soup). Cultural elements in chapter 8, such as the shadow play and the street trinkets, are real Chinese traditions.

Wudang Mountain, a real site in China known for its Taoist temples and martial arts, is the place where Sinegard Academy is built.

The hard -r sound of the Sinegardian’s Accent is a characteristic of the Beijing accent.

Both Sinegard and Beijing are the capital cities of Nikan/China.

The story’s life force, „Ki“, comes from Qi/Chi.

The provinces are named after the twelve zodiac animals. (This naming choice seems aimed at Western readers familiar with the Chinese zodiac but doesn’t reflect actual Chinese geography or naming customs.)

The gods mentioned—NuWa, the Jade Emperor, Erlang Shen, and Sanshengmu—are real Chinese deities.

The texts Rin studies, like Mengzi, Zhuangzi, Fuzi (Confucius), and Sunzi (Sun Tzu), are genuine Chinese classics named slightly differently or in Chinese spelling.

Some characters, like Su Daji and Jiang Ziya, are real historical figures from the 11th century BC. Though Jiang might also draw from a legend. Nezha is a folklore god, a patron of children.

At the same time, there are invented names that sound vaguely Asian but don’t match any real language or culture, leading to an inconsistent mix.

Even worse, the book often retains original names like Keju or Taoist hexagrams but alters their meanings: Keju, for instance, was a post-education civil service exam, not a college entrance test, and couldn't be passed by rote memorisation. Additionally, it was only open to men, so Rin would have needed to pull a Mulan stunt. (Though, to be fair, I’m quite glad she didn’t, as it helped the story avoid falling into familiar 'Asian stereotypes' and clichés in Western media.) It doesn’t even fit the timeline, as it was abolished in 1905 by the time of the Sino-Japanese War. The latter, the hexagrams, are misrepresented as there's no “Net” hexagram, and the drawing process shown doesn’t match actual Taoist practice, like calling something Tarot de Marseille but replacing the cards and meanings entirely.

Mention of „Gutter Oil“ in the context of „Siphoned from the gutter“. However, in reality, restaurants would reuse the same oil and afterwards sell it to a broker who distils and resells it.

Some references are historically accurate, others purely aesthetic, and some don’t connect logically, making the world feel uneven in its cultural representation. Most of the time, when this issue was raised, it was Chinese readers pointing this out, for example on Reddit*²: The_Bilo: „I am Chinese […] You can't put in real things from that culture or country into the novel without upsetting immersion. […] I feel like whenever I start to sink into this fictional world, the real world suddenly rears its head out of the pages and breaks my immersion entirely.“ Another reviewer, Sam77889, expands on this frustration, specifically criticising how references are used without proper grounding: „As someone who was born in China […] It feels like the author just heard some buzzwords and just went with it, like a bad fanfic with a Chinese-themed Minecraft texture pack. It’s not that gutter oil is anything essential to the world-building. But that’s the problem. It’s not. The author didn’t have to reference it. But since they did, they should have at least do some basic research on what they are referencing to.“

Accurate cultural representation does matter. These issues don't just disrupt the experience for Chinese readers; they can also confuse those less familiar with the history and culture. For many readers, including myself, The Poppy War acts as a first exposure to aspects of Chinese history and culture. Without a strong background, it's easy to take what’s presented at face value. If there were inaccuracies I didn’t recognise, or that haven’t been pointed out by others, I’ve likely absorbed them as truth. And that’s precisely the risk.

Historical Backdrop

A similar—and arguably far more troubling—issue arises in the novel’s treatment of its historical backdrop:

R. F. Kuang’s references in The Poppy War are intended to be profoundly complex, and her academic background underscores how deliberately she engages with such material. Kang has studied Chinese History extensively. She attended Georgetown University before earning a Master of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at Cambridge and an MSc in Contemporary Chinese Studies at Oxford. In 2020, she began pursuing a PhD in East Asian Languages at Yale. This is an immensely impressive academic foundation!

It’s also important to keep in mind that Kuang’s intention is not to use history as mere window dressing: The Poppy War’s central themes are intergenerational trauma and cycles of violence, issues that continue to hold relevance in modern Sino-Japanese relations. She was born into it, into a family that directly suffered through those very wars. Her use of those ties in The Poppy War serves a purpose: It is there to make a point, to convey a political message, not because she was unwilling or unable to craft proper world-building from imagination. Her engagement with Chinese history is deeply personal, rigorous, and intentional. For example, the focus on Rin’s darker skin and the discrimination she faces at Sinegard reflects Kuang’s own experiences upon returning to Beijing, the city that inspired Sinegard.

The novel handles its portrayal of anti-Japanese sentiment mostly (largely sustained until the closing section) with care. While the protagonist’s homeland harbours clear hostility towards Mugen (faux Japan), the narrative does not endorse this prejudice. Instead, it critiques such hatred and highlights its dangers. It's an achievement that is mature and difficult to pull off, especially from her perspective as a writer tackling national trauma. Though at times the message can feel heavy-handed, such as when Rin explicitly points out biological similarities between the people of Mugen and hers. (Thanks for spelling it out, girly!) It is nonetheless refreshing to see avoidance of simple vilification. My sole wish regarding this aspect would have been to see the exploration of Japan’s Dynamics during the 1930s, to provide them with a more understandable motivation for war.

On the other hand, I’m not quite sure what her argument is for the tie to Speer (faux Taiwan or Hong Kong): It’s described as a tributary of Nikan. Its people — violent warriors, portrayed as ‘exotic’. Suppressed. Wiped out by Mugen. And then Kuang based them on an actual nation? To quote the author: „Whenever I describe the world, I just say ‚faux China’ and ‚faux Japan.’“ And faux Taiwan and HK, or what?

Moreover, she fails in executing the historical involvement on a bigger scale:

The novel is heavily inspired by the Second Sino-Japanese War, one of the darkest and bloodiest periods in Chinese history (with around 20 million deaths, mostly Chinese civilians). For example, the fall of Golyn Niis closely mirrors the Nanjing Massacre (IMTFE estimate 100,000 to 200,000+ deaths, some sources estimate even up to 340,000.), while the research facility where Rin and Altan are held is based on Unit 731 (with 14,000 murdered victims and an estimated 200,000-300.000 deaths due to infectious illnesses caused by the facility’s activities). And those are just examples that are the most prominent in the story. Remember the dam flood I mentioned earlier? Altan’s order, only addressed in a single line of dialogue, references China’s 1938 Yellow River flood. (2 million deaths during or in the aftermath)

Within the observations made about Nikan vs China, this reinforces the issue: The problem is that in this world, magic and gods are real, making big changes for fantasy, yet real-world atrocities are merely changed, and instead, sometimes even word-for-word accurate to historical sources. In Kuang’s words, “pulled directly out of history books.” She’s proud of it.

That said, I genuinely ask myself, is this the appropriate setting for a fantasy book targeting young adults? Sure, fantasy as a genre can seriously engage with historical trauma, even be affirming and powerful to some groups. Yet, it doesn’t feel sensitive. Coming back to Meg’s review, I found on Goodreads, it expresses my fear very well: "To me, it feels exploitative and incredibly tasteless. To use other people's pain to make a fantasy novel more exciting. It's a line that shouldn't be crossed.“

It’s even worse, as Kuang mashes together the entire history from the 1800s to 1945. Hell, when I tried researching, I found myself on articles detailing events from 200 BC. One way a lot of people of Asian heritage making this critique more accessible to Western readers online is through an exaggerated comparison that compresses familiar Western conflicts and atrocities into a single, implausible character arc: Imagine our main character experiencing the Napoleonic Wars (starting in 1803), American Civil War, WW1, WW2 with the Holocaust, Dunkirk, D-Day landing, Infiltration of Nazi Germany, Escaping Auschwitz and Flying a bomber over Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1945) all in one book.*³ It illustrates how Poppy War treats historical trauma as a grocery shopping checklist.

Kuang undoubtedly has the academic credentials to support her choices, and I appreciate the introduction to significant and often overlooked parts of Chinese history. However, by compressing over a century of trauma into a single narrative as plot devices, the novel unintentionally diminishes the weight of these events. It risks oversimplifying complex historical suffering.

Narrative Consequences

Part Three, in particular, contains brutal and harrowing scenes that are in themselves very well written. War crimes are a grave subject and demand more than mere shock value. Kuang knows this. You can see this as she clearly attempts to tie each atrocity to Rin’s character development to serve a narrative purpose. However, the narrative impact of these events is often overshadowed by others: Take the massacre at Golyn Niis; It could have served as a pivotal motivation for Rin’s decision to annihilate Mugen, yet in the end, it’s Altan’s death that drives her. As a result, Golyn Niis feels narratively redundant — horrifying, yes, but without meaningful narrative consequence. It’s irrelevant to the reader.

How can a book include multiple genocides and yet fail to deliver any lasting reckoning or consequence? In the end, Kitay is the only character who condemns Rin’s destruction of Mugen, and even that objection is fleeting! One character expressing outrage is not enough! Why is the genocide of Speer (faux Taiwan or HK) discussed as a big massacre (as it should be!), but we’re just glancing over this one like it’s nothing? If you’re still not seeing the elephant in the room, let me spell it out: Rin blowing up the volcano is the book’s stand-in for dropping the atomic bombs. We glance over the fucking 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki like they’re nothing, for goodness’ sake! I wasn’t kidding earlier. It’s baffling, and frankly, disturbing.

Reception

Picking up from the quote I shared earlier from Meg: „I don't know if the casual American reader of this book will have read The Rape of Nanking or been to [the] Hall of Remembrance in Nanjing or understand how many Asian people from countries Japan attacked during the war still feel anger and pain about the brutal war crimes committed. Perhaps I'm more upset than I should be because I'm also Chinese-American and I care too much about how these things are represented and handled.“

What I found particularly interesting while researching the reception of The Poppy War was the clear divide in responses to its naming choices, historical background, and brutality: On one side are readers who rated it five stars without noticing these issues, or who did notice, but even praised them for it. On the other, there are readers who found such elements jarring or even offensive, describing them as pulling them out of the story. Interestingly, this divide often seems to align along cultural lines: the former group tends to consist of white American or ethnically unspecified reviewers, while the latter often were more openly Asian readers, claiming to either have a background of extensive historical knowledge, from families more directly affected, or living in Asia. Chinese reader The_Bilo mentioned in their conclusion: „I’ve spoken to several friends about the novel [regarding the naming issue], and none of them seem to share my feelings on it, although admittedly, none of them are Chinese, which I think is a huge part of it.“

I found it interesting how the novel reveals just how widespread the gaps in our historical knowledge can be — and how easily we may draw the wrong conclusions in their absence.

Children of Diaspora

Up to this point, I’ve focused on critiquing Kuang’s handling of the overlap between fantasy and reality, a concern I found raised in particular by many Chinese readers. What I haven’t yet addressed, though, is its impact on readers who found real emotional resonance in it.

Opinions among Asian-Americans are not monolithic. Obviously! While some, like Meg—whom I quoted extensively earlier—express discomfort or criticism, I also encountered numerous Asian-American voices who embraced the novel wholeheartedly. Many others praised The Poppy War not despite its choices, but because it provided representation they hadn’t often seen in mainstream publishing. And that, I think, is the book’s true target audience:

Kuang wrote this story for readers like herself — children of diaspora. Readers who have grown up only partially immersed in their culture and, as a result, have a big desire to connect with it. This audience awaited their entire lifetime for a book like this that weaved their experiences into an epic fantasy.

In an interview, the author compared this to Crazy Rich Asians: “It felt groundbreaking to us because it was the first time we saw someone who looked like us as the lead in a rom-com, and the first time we saw the specific struggle of being diaspora… But it flopped in Asia, because people there were like, ‘Yeah, our rom-coms already star Asians — this isn’t new.’ That’s true. Similarly, The Poppy War is written by a diaspora Chinese person for diaspora Chinese readers. It’s written in English, specifically for a Western audience. They [Asia] don’t need that story. We do.” Indeed, by 2020, when the final book of the series was released, The Poppy War had sold rights only in South Korea among Asian countries. The Asian, and especially the Chinese market, is saturated with all the mythology and source material Kuang drew from. This helps explain why it was so groundbreaking in the US and the UK instead!

This is where the emotional core of The Poppy War lies for many: Not in whether every historical parallel is exact or whether every naming decision lands cleanly, but in the feeling of finally being reflected in a story. That’s significant. And that connection deserves respect. To focus primarily on its flaw, as I initially did, risks reinforcing a hierarchy of cultural legitimacy: as though only those with a certain depth of knowledge are allowed to engage meaningfully with this history. That approach sidelines the very audience the book was written for. Readers who, like Kuang herself, sit between cultures, piecing together heritage and identity through fiction.

Trauma and grief don’t always resolve into clear-cut lessons. It doesn’t offer moral clarity. But then, neither does history. To suggest that some readers are simply less informed is to misread what the book is doing for them. It’s that they’re finally being invited into a conversation they were long excluded from. And that, in itself, is a power.

It all leads me to following Dilemma:

I don’t believe I’m in a position to definitively weigh how much Kuang’s insensitive handling, shaped by her academic lens, harms the book, or if the representation manages to outweigh it.

In my opinion, atrocities and human suffering are part of our shared human history. However, their weight is not distributed evenly. The pain of such events is carried most heavily by those whose communities lived through them, passed down through generations, and preserved in culture and memory. I’m not a child of the diaspora. I wasn’t a stranger to the culture around me, and the society I lived in wasn’t a stranger to mine.*⁴ This isn’t my history — not in the way it is for others. Because of that, I may be able to observe whether Kuang’s representation feels honest, exploitative, brave, or necessary, but I can’t weigh them against each other, than maybe those for whom this story cuts closer to home. What I can say is that The Poppy War left me conflicted. It is, at once, a book I found both deeply flawed and undeniably important.

(A very long) Conclusion

To sum up;

The fundamental challenge with The Poppy War lies in its intended audience and the ambitions Kuang drew from it:

The primary audience is Western readers of Asian heritage seeking a connection to their roots. The main problem, though, is that this background often comes with significant gaps in knowledge; a lack of representation in media, little to no formal education on Asian history in Western schools, and many atrocities unknown outside their countries of origin. They often lack the extensive knowledge of Chinese history that the book requires: „For many readers, it’s their first exposure to that mythology, culture, or history.“ Additionally, Kuang acknowledges that the average reader doesn’t necessarily register the abstract concept of colonialism as harmful: “Unless they witness the horrors of it vividly on the page—such as white colonisers forcibly converting natives—they don’t fully grasp why it is wrong. Many readers unfamiliar with this history, even those who identify as anti-racist, still need the text to work harder to clarify why certain movements or forms of cultural and military incursion are problematic.” This gap in understanding forced Kuang into a narrative that feels overtly flat, which I have critiqued several times in this review as uninspiring, overly simplistic, excessively polarising, and, at times, dull. It constrains her creativity.

The second issue arises from Kuang’s apparent uncertainty about whether the book is intended for a YA or adult audience. She hesitates to choose. She wishes to provide a YA representation novel that many children of the diaspora long to read, while simultaneously including adult-level discussion and commentary. The book sits in an odd limbo. Too heavily inspired by real events to fully work as fantasy, and too gritty and graphic in the latter half to suit a YA audience. Yet Rin’s character and the way her conflicts are explored feel too immature for an adult readership. And then, given the target group’s limited historical background, she has to excessively dump information on the reader in an attempt to bridge the knowledge gap for the adult themes.

And that started the third issue, which I have already explored in detail: Info-dumping like this lacks the sensitivity, nuance, and respect that Kuang should be expected to demonstrate from her academic background. Ultimately, The Poppy War becomes unsettling and insensitive towards one of the very cultures it intended to honour.

I genuinely admire her ideas and ambitions. There is potential in them. However, great ideas count for little if a fine sketch is ruined in the colouring. The Poppy War loses its voice and sense of purpose by attempting to be a YA story while also wanting to engage with history. It feels shallow. For all her reputation for thorough research, the material rarely moves past what’s easily gathered. It’s as if she skimmed Wikipedia for three days, copied and pasted information, and formatted it into a novel. Her brushwork—character, plot, tone—is applied in unconvincing strokes. The fantasy elements are unevenly shaded in, appearing when the plot demands, then fading into the backdrop. Rather than blending her layers into a coherent picture, Kuang leaves them sitting awkwardly beside one another. The result reads as low effort, speaking of a writer with vision, but little control over the tools.

But perhaps that’s the issue: I don’t believe Kuang harbours any bad intentions. I also don’t want to say it’s overcommitment, but rather directed in the wrong places. The execution falters under the weight of her own knowledge. In my free time, I often read academic papers—mostly in STEM—but recently I came across one titled Marketing Ideas: How to Write Research Articles that Readers Understand and Cite (Warren, Nooshin L.; Farmer, Matthew; Gu, Tianyu). The authors suggest this issue stems largely from the “curse of knowledge”: researchers know so much about their subject that they forget what it’s like to be a reader who doesn’t. They know their stuff, but just can’t communicate to save their lives. We know she’s a heavily studied scholar. She knows her stuff. And although she published The Poppy War during her undergraduate years, it’s her passion that’s evident and driving this problem. Kuang falls into this very trap. To me, she reminds me of my autistic urge to be exhaustively thorough, desperate not to miss including a single little detail (or atrocity) from her studies. Don’t get me wrong, my own writing exhibits the same flaw. Just look at this book review! But I don’t attempt a fantasy series either way, lol.

Does this diminish The Poppy War as an impressive debut? I believe Kuang is capable of more than this book shows. It was her first novel and series, which she wrote between the ages of just 19 and 24! If this is where her writing began, then I’m willing to continue reading her work and follow her development as an author.

To me, this book captures the apex of the Asian-American experience: The deep yearning for representation, connection, and a sense of belonging. It’s this very tension that gives The Poppy War its importance. It can be read as a triumph or a failure, depending on who’s reading and where they’re reading from. For what it offers, I want to give it five stars. For where it falters, I feel I must give it one. In a way, it unfortunately reflects the reality many with dual heritage live through—caught between two frameworks, never fully at ease in either.

But that’s absolutely not a satisfying place to leave things ... So, to Book 2, I shall come.

Who should read the book?

I doubt I’ll say this often, but everyone—yes, everyone—should read this book. I genuinely believe it’s the best I’ve read in 2026. When I’m looking for a book, I want something meticulously crafted and something that sparks real discussion. This book does the latter. Just look at the word count! It may not be a masterpiece of creative writing ... in fact, it’s far from creative, but it succeeds in prompting thought, and that matters more to me.

That said, there are still two conditions you need to meet to enjoy the process: (1) You have to enjoy plot-driven narratives. If you do, you’re in for something strong. (2) You have to be willing to do further reading. Earlier in my notes, I pointed out how the book highlights cultural knowledge gaps. I also said that without any background in Chinese history and culture, the book can easily mislead readers. Some might brush off incorrect names or interpretations as minor, but they’re not. Not to Chinese readers. Cultural representation suffers when accuracy is thrown aside. In my home country, Germany, even children are taught the weight and horror of the world wars — how serious and devastating they were. The Poppy War fails to do the same with a lot of the atrocities it depicts. It attempts to portray and honour Chinese and Asian culture, but doesn’t manage to do so with enough care or accuracy. That’s insufficient. It’s a one-star read for me if it doesn’t achieve the very thing it dedicates and sacrifices everything for.

So if you decide to pick up the book, I genuinely believe it’s your moral responsibility to do the research. I didn’t cover it here (because holy shit the word count), but I did read through a fair bit—academic papers, articles, historical records, and proper history books. A lot. Through that, the book managed something significant: It pushed me to learn more about a country’s history. That’s incredibly special. The Poppy War fulfilled its purpose for me. And that’s why I said earlier it’s the best book I’ve read this year; not because it’s flawless, but because of where it led me. ... Oh, look, a cheesy SJM phrase I can tattoo on my wall.

That said, this reading isn’t complete. I’m not an expert on Chinese history, far from knowing what an average Chinese citizen does. And no, I’m not saying you need to go out and earn a degree in it either. That would be gatekeeping. This isn’t about who gets to read the book; it’s about how they read it once they do. Curiosity and care should be enough. A reader doesn’t need all the answers or read every piece out there, but they do have a responsibility not to take everything at face value. The book deserves your damn attention for the weight it carries.

That’s a way to balance The Poppy War’s major flaws. A way its one-star lows can reach five-star highs. But you have to put the effort in. If you’re after an easy read and don’t want to think critically, then don’t bother. This book isn’t for you. Not even on its own.

Footnotes

*¹= As implied later in the text, that list comes from a range of people highlighting those specific issues. Only a handful were things I noticed myself, and later checked for accuracy. Though, I began compiling the list early on, during the initial stages of my research.

*²= Before you ask: „Why Reddit?“ I usually check the reception of a book across various platforms, including blogs and book review sites. While it’s true that Reddit can be a hostile place full of hate–please take that into account–I wouldn’t have referenced those reviews unless the same sentiments had cropped up repeatedly across different threads and other platforms. I decided to ultimately use quotes from this specific platform, as Reddit’s largest demographic group is reportedly Asian, at around 36%, compared to book review platforms where Asians are a minority (e.g. 6% on Goodreads). Therefore, being more represented. Journals were out of the discussion entirely: Those seen as reputable in the West … tend to reflect Western perspectives (duhhh) and often have financial incentives involved.

*³= For a while, I considered adding “Oh, and the main character is Hitler” to the list, but decided against it. It’s wildly inaccurate from a historical standpoint — adding this here just in case anyone might be having that thought.

*⁴= I, unfortunately, have to be sneaky here: This refers solely to cultural elements shaped by ethnicity and nationality. As an autistic person, my experiences differ in other respects, so the sentiment doesn’t carry over beyond that. Footnote in this case, since I might use that sentence in negation in different contexts.

#rf kuang#the poppy war#tpw trilogy#tpw#the poppy war trilogy#fang runin#books#literature#currently reading#reading#spilled thoughts#prose#booklr#bookworm#authors#book blog#lit#book review#history#china#chinese culture#chinese history#academia#book recommendations#book reccs#moodboard#aesthetic moodboard#zorya#zorya book review#zorya essay

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

vera wong's guide to snooping (on a dead man) // jesse sutanto

first published: 2025 read: 14 july 2025 - 17 july 2025 pages: 384 format: e-book

genres: fiction; adult; mystery (cosy); humour favourite character(s): vera least favourite character(s): i don't have one first line(s): "Vera Wong Zhuzhu should be having the time of her life."

rating: 🌕🌕🌕🌕🌑 thoughts: when i read the first vera wong book back in 2023, it was initially written as a standalone - so imagine how shocked i was when i heard we were getting a book two! having just reread book one, i can say that vera wong's guide to snooping (on a dead man) is pretty much on par. new mystery, same cosy vibes, found family, and fun humour. i will say that though i thoroughly enjoyed the read, and i'm glad we got a sequel, i am also slightly more critical of this book than the first.

plot-wise, it did start out feeling a little formulaic in comparison to the first book. very similar in terms of vera gathering her list of suspects, converting them into her surrogate family, then each of them self-eliminating from the suspect list one by one. in fact it felt so similar to book one that i was looking for a red herring culprit much in the way of the first. but then i will say that the book surprised me with the way it changed tacks and disrupted the formula. thematically this book takes a bit of a darker turn than expected, with some heavy themes, and i think it was to the benefit of the narrative. i liked understanding why this route was taken per the author's note. it felt like it was handled with care.

the cast was nice, and i liked them, but i don't think they had quite the sparkle or chemistry that the OG cast did. as individuals, i'm not sure they had quite the charisma that riki, sana, oliver, and julia had. maybe it's because it felt a little forced this time around, with the new cast being brought together by vera in the exact same way as the OGs were. that said, i liked what they represented and the meaning behind their individual journeys. and i liked the themes that could be explored between the characters (for example the shared loneliness between vera and qiang wen, or the sense of being lost which aimes, sana, and julia could relate to). and i was also glad that the OGs made a lot of appearances (aside from riki for some reason).

the writing still had its charm and good natured humour as from book one. it has some moments of dated/millennial cringe humour (i don't remember the last time i saw anyone use the words 'stahp' or 'lolsob' and yet i've read each of those twice in the last week across both books in this series) but it can be overlooked.

i enjoyed vera wong's guide to snooping (on a dead man), and, as i mentioned before, i am glad we got a second book. the ending suggests we're going to get at least a third instalment where vera goes international... i'm certainly looking forward to reading that, but i do wonder how many times the series' formula can be repeated and i hope these books don't overstay their welcome. vera wong's unsolicited advice for murderers was a great standalone and i suppose i'm just wary that this lovely little series becomes something stagnant and repetitive.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

POPPY WAR ESSAY IS DONE.

ITS WRITTEN.

OH MY FUCKING GOD.

THAT SHIT TOOK ME 4 WEEKS.

WTF.

#The Poppy War#the poppy war trilogy#tpw#tpw trilogy#zorya#Final word count is 8004#Reading Time 32min#Speaking TIme 54min+#7%* plagiarised which is pretty good i guess#*after edits#CUT DOWN 2000 WORDS (and some contents :cry:)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ohhh I can absolutely see that. I think I agree from that angle; while the if and why might never really have been in question, the how definitely still feels uncertain to me. <3

౨ৎ the burning god by r.f. kuang review

rating : 3.75 ★

started : jun 19th, 2025 / finished : jul 3rd, 2025

CW: heavy spoilers under the cut

— finally, i’ve finished the poppy war trilogy.

this book was definitely the weakest in the series. nearly everything that i wanted to happen didn’t happen.

the dragon republic ended on such a strong note after 600+ pages of military strategy, politics, and heartbreak that i expected that same fiery ending to book 2 to be transported into the burning god.

while i get that kuang’s intention was to keep it slow and hopeless on purpose, it still wasn’t the direction i was hoping for. instead, i was anticipating action-heavy sequences with rin and nezha’s armies but that really wasn’t the case at all!

one positive thing i can definitely say about the burning god was the layout. one thing kuang is a master at is world building. she paints such vivid pictures, every terrain jumps off the pages. personally, i love snowy weather in all types of media, and the sprawling snow and biting cold really meshed well with that bleakness of this book. definitely a refreshing jump from the dragon republic’s majority spent on a ship (which was awesome! kuang also handled this well). one of my favorite parts of this book was when rin, jiang, and daji marched up a steep mountain to the heavenly temple. the way the atmosphere was described, that clear switch from solitary ground to sacred ground was absolutely phenomenal.

and now… i must talk about the ending: rin’s death. i had a feeling this was going to happen and i didn’t know why. i didn’t see any signs of foreshadowing, not until the final few pages, but even though i predicted it i’m not mad that it happened. in fact, i’m glad it did. another thing kuang nails every time is realistic endings. not one of her books ends on a hopeful note. if a realistic ending is bleak, she lets it be. and i love that about her writing. rin’s death was tragic because she felt she was a shell of herself and because she felt it would break the war cycle. it’s sad, it’s unfair, it just is. and the fact that kitay was so confident in his loyalty to support her decision shows just how important their bond is. and nezha? oh nezha…. i still have mixed feelings about him. yeah, i’m still upset at him for betraying rin but i do feel for him in the end. he was lonely despite being surrounded by people. and on top of that, he’s mourning a girl he both loved and hated, and now he has the weight of rebuilding nikara on his shoulders. poor guy.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Service Info: Updated My Bookshelf -List once again.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, that middle aged woman and those pensioners have taste then :) 🤷♀️

sometimes i do worry i have the reading taste of a middle aged woman and i don't know if that's a compliment or an insult to myself.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

can anyone recommend some good longer form book review/reading blogs?

#rb bc I badly want those reccs too#but also let me introduce myself#— I've got like a 8K book review sitting in my drafts

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

And what does the middle-aged woman read? :D

sometimes i do worry i have the reading taste of a middle aged woman and i don't know if that's a compliment or an insult to myself.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

wait, that’s a snowball system.

You’re not depressed. You just need $250,000 in your bank account.

210K notes

·

View notes

Text

YOU'VE ALWAYS GOT TIME FOR A TAX WRITE-OFF.

Did Claude pay for all the doctor's visits since Stella had braces? Haru had glasses, Julius had a prosthetic eye, that wasn't cheap. When did they have time for this?!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELEANORWOLFSON ROSEWOOD CURSED EDITS ARE BACK

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“dear reader, area 51 r sub- ed t u nonethe rey"

Missed opportunity to utilise tumblr's colour lag to put a cheeky secret message in there. <3

dear reader,

💚 🏠 📚 🎼 🖼

welcome to the main base of area 51, our sub-base is situated at @moon2saturn2mars and our help desk is above. though you... definitely aren't supposed to be here, we are glad to have you nonetheless.

yours,

shrey

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solution to Core Problem:

Library + Lending Books

Project Gutenberg & other free legal online resources

Read school-assigned books since their prices are typically lower for accessibility

Search for different publishing houses and editions

Second-hand + Antique Shops

Classics tend to be cheaper + don't read mainstream books

AO3

If you're very desperate ... read public academics papers instead

Answer that is actually related to the initial Question:

Classics dude, Classics

I need CHEAP book recs because I do not have the money to be buying all these books 😭😭

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

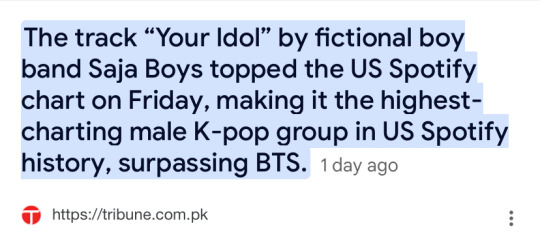

Guys, the Honmoon is fucked.

#kpdh#kpop demon hunters#kpop#bts#bts army#saja boys#jinu kpdh#romance kpdh#abs kpdh#abby kpdh#baby kpdh#mystery kpdh#netflix#usa#charts#music#sony animation#zorya

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ultimate Dark Academia Book Recommendation Guide Ever

The title of this post is clickbait. I, unfortunately, have not read every book ever. Not all of these books are particularly “dark” either. However, these are my recommendations for your dark academia fix. The quality of each of these books varies. I have limited this list to books that are directly linked to the world of academia and/or which have a vaguely academic setting.

Dark Academia staples:

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

If We Were Villains by M.L. Rio

Dead Poets Society by Nancy H. Kleinbaum

Vita Nostra by Maryna Dyachenko

Dark academia litfic or contemporary:

Bunny by Mona Awad

The Idiot by Elif Batuman

These Violent Delights by Micah Nemerever

White Ivy by Susie Yang

The Cloisters by Katy Hays

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

The Lake of Dead Languages by Carol Goodman

A Separate Peace by John Knowles

Black Chalk by Christopher J. Yates

Attribution by Linda Moore

Dark academia thrillers or horror:

In My Dreams I Hold a Knife by Ashley Winstead

The Maidens by Alex Michaelides

Ghosts of Harvard by Francesca Serritella

Catherine House by Elisabeth Thomas

Plain Bad Heroines by Emily M. Danforth

They Never Learn by Layne Fargo

The It Girl by Ruth Ware

Never Saw Me Coming by Vera Kurian

Dark academia fantasy/sci-fi:

Babel: An Arcane History by R.F. Kuang

The Atlas Six by Olivie Blake

Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

A Lesson in Vengeance by Victoria Lee

The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern

Vicious by V.E. Schwab

A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness

The Betrayals by Bridget Collins

Dark academia romance:

Gothikana by RuNyx

Alone With You in the Ether by Olivie Blake

Dark academia YA or MG:

Truly Devious by Maureen Johnson

A Deadly Education by Naomi Novik

Ace of Spades by Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé

The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater

Legendborn by Tracy Deonn

Crave by Tracy Wolff

Wilder Girls by Rory Power

The Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling

Dark academia miscellaneous:

My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell

Disorientation by Elaine Hsieh Chou

Alphabet of Thorn by Patricia A. McKillip

13K notes

·

View notes