i like to suffer creatively✢ ✢ ✢irregular updatesask box open! dm for beta reading/proofreading ❤spam @emptyrows

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

just came across this when looking back at some old posts. DID NOT KNOW THIS thank you so much (very belatedly) for sharing

Let's talk about story structure.

Fabricating the narrative structure of your story can be difficult, and it can be helpful to use already known and well-established story structures as a sort of blueprint to guide you along the way. Before we delve into a few of the more popular ones, however, what exactly does this term entail?

Story structure refers to the framework or organization of a narrative. It is typically divided into key elements such as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as the skeleton upon which the plot, characters, and themes are built. It provides a roadmap of sorts for the progression of events and emotional arcs within a story.

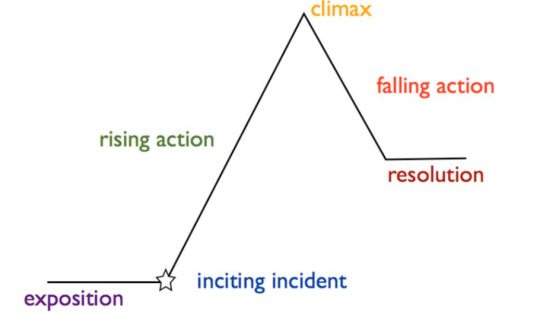

Freytag's Pyramid:

Also known as a five-act structure, this is pretty much your standard story structure that you likely learned in English class at some point. It looks something like this:

Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and basic situation of the story.

Inciting Incident: The event that sets the main conflict of the story in motion, often disrupting the status quo for the protagonist.

Rising Action: Series of events that build tension and escalate the conflict, leading toward the story's climax.

Climax: The highest point of tension or the turning point in the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the outcome is decided.

Falling Action: Events that occur as a result of the climax, leading towards the resolution and tying up loose ends.

Resolution (or Denouement): The final outcome of the story, where the conflict is resolved, and any remaining questions or conflicts are addressed, providing closure for the audience.

Though the overuse of this story structure may be seen as a downside, it's used so much for a reason. Its intuitive structure provides a reliable framework for writers to build upon, ensuring clear progression and emotional resonance in their stories and drawing everything to a resolution that is satisfactory for the readers.

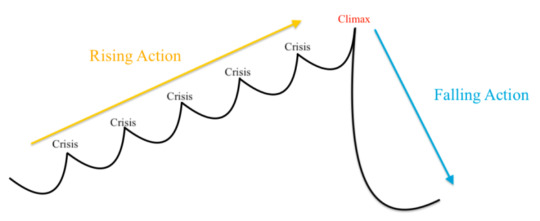

The Fichtean Curve:

The Fichtean Curve is characterised by a gradual rise in tension and conflict, leading to a climactic peak, followed by a swift resolution. It emphasises the building of suspense and intensity throughout the narrative, following a pattern of escalating crises leading to a climax representing the peak of the protagonist's struggle, then a swift resolution.

Initial Crisis: The story begins with a significant event or problem that immediately grabs the audience's attention, setting the plot in motion.

Escalating Crises: Additional challenges or complications arise, intensifying the protagonist's struggles and increasing the stakes.

Climax: The tension reaches its peak as the protagonist confronts the central obstacle or makes a crucial decision.

Swift Resolution: Following the climax, conflicts are rapidly resolved, often with a sudden shift or revelation, bringing closure to the narrative. Note that all loose ends may not be tied by the end, and that's completely fine as long as it works in your story—leaving some room for speculation or suspense can be intriguing.

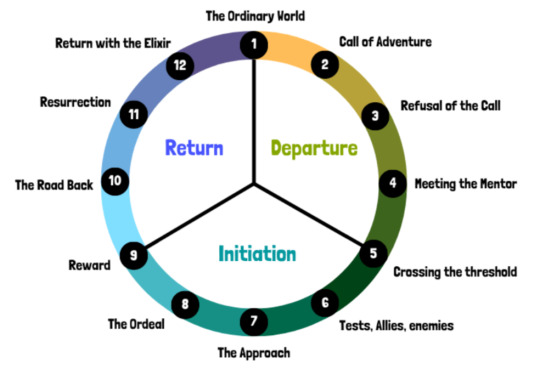

The Hero’s Journey:

The Hero's Journey follows a protagonist through a transformative adventure. It outlines their journey from ordinary life into the unknown, encountering challenges, allies, and adversaries along the way, ultimately leading to personal growth and a return to the familiar world with newfound wisdom or treasures.

Call to Adventure: The hero receives a summons or challenge that disrupts their ordinary life.

Refusal of the Call: Initially, the hero may resist or hesitate in accepting the adventure.

Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a wise mentor who provides guidance and assistance.

Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the unknown, facing the challenges of the journey.

Trials and Tests: Along the journey, the hero faces various obstacles and adversaries that test their skills and resolve.

Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero approaches the central conflict or their deepest fears.

The Ordeal: The hero faces their greatest challenge, often confronting the main antagonist or undergoing a significant transformation.

Reward: After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, such as treasure, knowledge, or inner growth.

The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, encountering final obstacles or confrontations.

Resurrection: The hero faces one final test or ordeal that solidifies their transformation.

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing back the lessons learned or treasures gained to benefit themselves or others.

Exploring these different story structures reveals the intricate paths characters traverse in their journeys. Each framework provides a blueprint for crafting engaging narratives that captivate audiences. Understanding these underlying structures can help gain an array of tools to create unforgettable tales that resonate with audiences of all kind.

Happy writing! Hope this was helpful ❤

#veeeery long post but worth reading#reblog#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#story structure#on writing#writers on tumblr#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#writing community#add tags

500 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I'm currently writing two first-person books, and I need help as one of them for almost the entirety of the first chapter it's only the MC so I'm stuck writing a lot of 《 I 》 and I'm trying to avoid it... But it's hard when it's all first-person POV. Could I get any help with this? I'm asking for advice if that helps clarify anything.

I'm sorry if this goes against anything, and if it sounds offensive, I'm very sorry...😔

Hi, thanks for asking! Here are some tips that might help out a little.

1. Make the world do the work.

Instead of leading every sentence with "I," try leading with the environment. You'll still be experiencing the world through the character's senses, but the focus shifts so that the reader feels more immersed rather than just watching the character observe it, as well as reducing the use of "I" in your writing.

Instead of: 'I walked through the forest. I could hear birds singing. I felt the damp earth beneath my boots.' Try: 'Branches swayed overhead, birds sang somewhere beyond the moss-covered path, and wet earth clung to my boots.'

2. Thoughts without labels

One of the best parts of writing in first-person is the ability to show internal monologue without constantly saying 'I thought' or 'I wondered' or tags of that element—you can just state the thoughts as part of the narrative rather than announcing that your narrator is thinking. If it’s first-person and we’re in their head, the reader will know.

3. Sentence structure variety

If you feel like you're using "I" too much, the problem may lie in stacking sentences in the same structure rather than overuse of the word. Adding in variation will help keep the flow more dynamic and make it seem less repetitive or robotic.

Instead of: 'I took a deep breath. I couldn't believe it. I was shocked.' Try: 'I drew in a sharp breath, disbelief flickering through me as I stood, frozen in shock.'

4. Body language

You can use body language, sensory reactions, and behavior to replace direct declarations of emotion, and let your readers feel it rather than being told straight out. Consequently, this will also make your writing more descriptive and immersive.

Instead of:' I was nervous.' Try: 'My hands wouldn’t stop twitching. The room suddenly felt two sizes too small.'

5. Zoom out sometimes

Your narrator doesn't have to be narrating every second of their life—rather, they can remember, summarise, or observe in a more omniscient way. By zooming out like this, you're describing the space, mood, and moment and showing your character's feelings through the environment instead of stating them directly.

Instead of:' I sat on the edge of my bed. I tried to breathe, but it felt too hard.' Try: 'The room hadn’t changed, but everything in it felt wrong. The walls leaned too close, the air suffocatingly thick with unsaid thoughts.'

-

The bottom line is, writing in first-person isn't about reporting events, but about letting your reader experience them, filtered through your character's personality, humour, wounds, and overall worldview. And keep in mind that you're not doing anything wrong by having a lot of "I" in your writing—writing in first-person entails it. Rather than aiming to banish it or reduce your usage of it, try to find more ways to add variation in your writing and sentence structure to keep it fresh and immersive for your readers.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writers on tumblr#writers#on writing#writing community#writerscommunity#deception-united

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, my story's protagonist has an older sister who is a very untrustworthy and unreliable narrator who twists the truth to fit her reality or lies a lot. One of these lies is about their parents. The sister claims that their parents always fought and that their father was abusive towards their mother.

In reality, while their parents did argue, they never got into any divorce-level fights or disagreements. Even if her father does raise his voice, he immediately regrets his actions and apologizes.

How do I show that the sister is not being truthful?

Thanks for asking! Here are some tips.

1. Memory inconsistencies

One way to convey this is to make her story change in small ways every time she tells it. Memory is fluid, but liars often can't keep track of their own fabrications. One time she might say "Dad broke a plate in rage," another time she says he punched a hole in the wall. These inconsistencies may be unnoticeable at first, but when they line up they can create a growing sense of suspicion.

Have her describe the parents' fights in wildly exaggerated terms, like "they used to scream at each other every night," but when the protagonist (or even side characters) remember these moments, they might be much quieter, more normal arguments. Or you could show flashbacks to make the point, like of a scene the parents are arguing about something like finances, raising their voices for a second, but then calming down.

Keep in mind that memory can be hazy and emotional, so even flashbacks can be a little fuzzy—but the overall emotional tone should feel healthier than the sister paints.

2. Use other characters' reactions

Sometimes the best proof that something’s off is how other people react—maybe another sibling frowns when she speaks or an old neighbour fondly remembers the parents being affectionate. Quiet, understated counterpoints like this might not be obvious upon first glance, but the reader will likely be able to put it all together as the story goes on by comparing narrations.

3. Build the lie into her character

Think about why she lies about this. Is it protection? Resentment? Manipulation? Trauma? Showing that she needs to warp reality, whether to feel better, to play victim, or hide her own guilt, makes her lies character-driven, not just plot devices or confusing contradictions. Readers don’t need to like her lies, but this will give a reason to understand that they are a survival mechanism rather than being random.

4. Body language

This might not be visible when the narrative is from the sister's POV, but consider her body language when she talks about it. You can hint that she's trying to believe it herself or that she needs this lie to pass through making it intense, like she's too eager to convince others.

Ex: wringing hands, fake tears that come a little too fast, getting mad if someone questions her version, etc.

She may also overact when she recounts these fights, like dodging eye contact, fidgeting, grinning too widely, or acting too confident as if to compensate or make her words more believable.

5. Catching her lying about other things

Though the reasons for her lie may differ, a person who lies perpetually about one thing is also likely to twist other small things here and there as well. If readers already notice her doing things like claiming someone said something they didn't or playing the victim when it's not justified, they'll naturally question her bigger claims without you needing to say it or make it explicit.

6. Overcomplication

Something to keep in mind is that sometimes when liars are pressed, they may overcomplicate their stories to sound more convincing. If you want, you could have the sister’s stories get more and more dramatic the more she’s doubted, like she’s trying to "prove" it instead of just telling the truth.

7. Contrast her stories with specific, concrete memories

This point depends on how obvious you want to make her lies—but one way you could go about it is not to immediately contradict her when she makes claims about them having fought all the time, but to let the protagonist or other characters naturally recall memories that suggest otherwise. Providing memory as proof rather than direct denial will get readers to catch on.

8. Trust your reader

You don't have to explain the lie too early or correct her in a big dramatic reveal—let it be a sort of creeping realisation. Remember, your readers absolutely have the ability to catch on and connect the dots themselves.

-

Hope this helped!

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writers on tumblr#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#deception-united

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do I write about a character that does gymnastics? I don't know a single thing about practices, how things are scored, and overall how to describe it.

Hi, thanks for asking! I don't know much about gymnastics myself, unfortunately, but here's some information I gathered (feel free to correct me or add on).

1. You don't need to explain the whole sport.

Your readers aren’t expecting a technical manual—they’re looking for the feeling. When you write about your character, you’re not writing about scoring rubrics or competition regulations (unless your plot absolutely demands it); rather, focus on what it feels like rather than what it officially is.

Ex: Her body arcing through the air, the rush of the landing, the tiny breath she holds before a back handspring, etc.

Instead of complicated terms and things some of your readers won't fully understand or connect to, make it more centred around the motion and emotion.

2. Practices (repetition & drills)

Gymnastics practices can be long and grueling. Athletes drill basic moves over and over to perfection (like handstands, cartwheels, backbends). They'll work on strength (pull-ups, pushups, core workouts), flexibility (splits, bridges), and techniques (like perfecting the way they stick a landing).

A practice could involve:

Warming up (light jogging, stretching)

Conditioning (core, arms, legs)

Drilling basic skills

Working on routines (choreographed sequences for competition)

3. Competitions

Gymnasts usually compete in four events if they’re doing artistic gymnastics (the most common form):

Vault (run, jump, flip off a vaulting table)

Bars (swinging between two uneven bars)

Beam (a 4-inch-wide balance beam)

Floor (a tumbling and dance routine on a large mat)

They're judged on:

Difficulty (how hard the routine is)

Execution (how well they perform it—points are taken off for wobbles, falls, or bad form)

But again, keep in mind that you usually won't need a real judge’s scorecard for your narrative. The point isn't to have a full manual on gymnastics for your reader, but the character, inner conflict, motivations, goals, and plot. For example, a fall usually costs a lot of points, but the focus of your story might be to show your character recovering after a mistake like this rather than earning a perfect score.

4. Describing movement

Gymnastics is full of sharpness, grace, power, and control. When you describe a move, don't get bogged down in trying to name every twist. Instead, use verbs that sound dynamic (vaulted, twisted, snapped, launched, spun, lunged, landed, crashed).

Ex: 'She hurled herself into the air, twisting once, twice, before her feet slammed into the mat with a jolt that echoed through her bones.'

Even without fancy jargon the reader will have to look up or ignore, using familiar language anyone can understand can help them feel it, even if they can't personally relate.

5. Emotional stakes

Any story needs internal conflict and a emotion. Consider what your main character is going through—is she chasing approval? Fighting fear? Battling her own body? Gymnastics as a sport demands a lot, like bravery, pain tolerance, and perfectionism. Use this to fuel your character arc. Maybe missing a trick feels like failing her whole family, for example.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#gymnastics#writers on tumblr#writer help#writerscommunity#deception-united

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I saw the post of how to write a father daughter crumbling relationship, and I wanted to ask how you write a father daughter relationship that’s already broken? the way i’m going with my story is she ran away at one point and he’s evil. She ends up seeing him again years later, has to go against him, and even fight him at some point to take him down. They’ll probably never fix the relationship ever, but I still want to have little pieces where there’s that ping of like “that’s my father”yk? I might also add a plot that he now has another daughter too, I hope this is not confusing, but do you think you could help with some tips? :)

Hi, thanks for asking! Here are some tips and ideas.

1. Start with echoes instead of flashbacks.

You don't need to info-dump their entire backstory right at the start. Try using emotional echoes instead—like small memories, half-formed thoughts, or sensory triggers. A particular smell or sight could remind her of her father, especially if it's from what she remembers he was like before their relationship broke or how she wishes it could be. This creates emotional disruption and can help the reader feel the dissonance between who he was and who he became without having to include pages of detailed reminiscing.

2. Focus on what's missing.

Because the relationship is already shattered, a lot of the emotional weight will come from absence. She's not necessarily mourning what happened, but what never did, like a birthday he didn't show up for, the safety she should've felt, things she wishes she had but was never given.

3. Resenting the pieces that still care

Rather than complete hatred, have your protagonist hate that she still feels something. Add in the odd confusing flicker of warmth, nostalgia, or longing that'll make her seem more real instead of just hardened or revenge-focused.

Ex: Noticing a trait she shares with him, flinching at the way he says her name, etc.

4. Mirrored behaviour

You can have her catch herself doing something he does, no matter how subtle (tilting her head the same way when thinking, using a fighting tactic he always did), and it sickens her. This can add inner conflict, especially when she starts questioning 'what else did I inherit?'—maybe she'll think that no matter how much she ran, some part of him is in her.

5. Make the father human.

Villainous as he is, he still is human; he should be terrifying because he's believable. He might believe what he did was necessary, show that he cares in twisted ways, or mourn losing her while refusing to admit that he was wrong. This contradiction can add depth—and as twisted and cruel as he may be, remembering the tiny things like a lullaby or a joke he used to say may haunt her. Though they don't nearly redeem him, they can be the reasons it hurts to fight him.

6. 2nd daughter

I love that you added a second daughter—it can give rise to more emotions and further development. Your protagonist might feel jealous, protective, disgusted. Maybe the new daughter thinks he's a great father (if he learnt from his mistakes?); or maybe he's worse than ever.

This new dynamic can go to show who he is now and force your protagonist to question things. She might be a mirror or a threat: if he's softer with her, maybe your protagonist is furious but also jealous, then ashamed of that jealousy; but if he's using her, too, she might want to save this sister—not necessarily out of love, but out of revenge ('I won't let him ruin her like he did me').

7. Confrontation

When she finally faces him, make it more than just a boss fight. There are going to be emotional grenades from their broken bond, even as they fight (a flicker of hesitation, a glance, a choice not to kill when they could have).

8. Ending

You don't need to end with reconciliation—just recognition. Not all wounds heal, and that's okay. Let the narrative acknowledge the connection without having to fully repair it. Sometimes redemption arcs aren't necessary for the story to have a good ending.

Hope this helped!

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writer help#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#deception-united

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey everyone! i've been locked out of my account since around the start of april. so sorry to all asks who've gone unanswered—i'll be getting to those as soon as i can. ask box and is open and DMs welcome as always ❤

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

yes

How do you write a character who is mature for their age?

My characters are all between 18-14 and act a lot more mature than their age due to how they grew up? There are about 10+ of them, and how do I make them act grown up but still be kids at the same time, while still holding leadership positions.

Hi, thanks for asking! I love this question—you'll find this in a lot of narratives, and if your characters have grown up in harsh or demanding environments, it makes sense that they’d be more responsible, insightful, or emotionally resilient than their peers; but it's important for the readers to still feel that they're young. Here are some tips.

Writing Mature Young Characters

1. Maturity through experience, not just speech

Your characters might sound older because of what they've been through, not just because they use fancy vocabulary or speak in deep philosophical metaphors. This maturity could come from:

The way they handle stress and responsibility

Their ability to assess situations logically rather than emotionally (though they’ll still have emotional moments)

The way they interact with adults (sometimes as equals, sometimes with hidden insecurity)

For example, a teenager leading a resistance group might have a sharp strategic mind, but that doesn’t mean they don’t feel the pressure of failure or secretly wish someone else could handle it. Let that complexity show.

2. Give them moments of being kids.

No matter how much responsibility they carry, they’ll still have cracks in their armour that shows their youth. Examples:

Stupid little habits (chews on their sleeves, obsessed with collecting something odd, still secretly sleeps with a stuffed animal, etc.)

Impulsive moments where emotions override logic (storming off, making reckless decisions, blurting out feelings they later regret)

A desire for normalcy—maybe they joke about things they missed out on or envy people their age who don’t have the same burdens

Even the most hardened of warriors is still a kid (in the context of this ask) and might make inside jokes, argue over dumb things, or mess around when the stakes aren’t high. Or they might make tactical decisions with the confidence of an adult, but forget to eat, sleep, or take care of themselves like a kid.

3. Leadership that feels earned, not forced

If your teens are in positions of power, show why they’re there. Are they the only ones willing to take charge? Are adults absent, dead, or untrustworthy? Did they prove themselves through skill or sheer survival? For example, you can make it feel:

Respected, not convenient—others follow them because they believe in them, not just because the story needs them in charge.

Hard-earned—maybe they had to fight for authority, prove themselves, or take on responsibilities that no one else wanted.

Lonely—leadership is isolating, especially for teens who are aware they’ve lost the freedom of childhood.

At the same time, they might struggle with things like imposter syndrome or self-doubt.

4. Age-appropriate emotional reactions

Even if they talk or act like adults, their emotional responses should remind readers that they aren't. They might:

Feel things too intensely (like anger, grief, and joy to the point of being consuming or reckless), like snapping in frustration when they’re stressed instead of handling things with full adult restraint

Have a skewed sense of consequences (thinking they’re invincible, or believing failure means everything is doomed)

Struggle with emotional control, like bottling everything up until they explode or lashing out because they don’t have healthy coping mechanisms

Maybe they can negotiate peace between feuding clans but are completely helpless when dealing with personal rejection; or they can keep calm under fire but cry when no one is watching. Things like this not only add depth to your characters, but remind readers that they're still babies.

5. Mature, but not omniscient

For instance, a fifteen-year-old might be commanding an army in battle but have no idea how to comfort a crying friend. Examples:

A teenager who had to raise their siblings will have strong leadership and nurturing skills, but might not know how to handle romance or peer friendships well

Still longing for normalcy in ways they don’t admit

Thinking they know everything, but getting blindsided by something outside their experience

6. Let them have growth arcs.

One of the best ways to balance maturity and youth is to show them learning. Maybe they act like they know everything, only to be humbled by a mistake; or assume they have to be strong all the time, but later realise they need help too and it's alright to ask for it. This'll remind the audience that while they may be wise beyond their years, they are still growing.

7. Inexperience

As many skills and responsibilities they may have, a teenager will likely still be inexperienced. For example:

They need to make difficult decisions since they're in leadership positions, but still struggle with the weight of it

Don’t yet have the emotional distance to detach from losses

Competent in battle but still hesitate before killing

8. Speech, humour, & interests

A mature teen might be more articulate and well-spoken, but they won’t sound like a university professor. They might still joke, use slang, or get snarky when comfortable.

It's also important not to forget about personal hobbies and random little things they get excited about. They may be world-weary, but they can still be dorky about their interests.

9. They might not have all the power.

Even if they hold leadership positions, adults might still underestimate them or try to manipulate them; they might be technically in charge but constantly fighting to be taken seriously, or believe they have control over their own lives only to realise they’re still at the mercy of the systems around them.

---

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous

195 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you write a character who is mature for their age?

My characters are all between 18-14 and act a lot more mature than their age due to how they grew up? There are about 10+ of them, and how do I make them act grown up but still be kids at the same time, while still holding leadership positions.

Hi, thanks for asking! I love this question—you'll find this in a lot of narratives, and if your characters have grown up in harsh or demanding environments, it makes sense that they’d be more responsible, insightful, or emotionally resilient than their peers; but it's important for the readers to still feel that they're young. Here are some tips.

Writing Mature Young Characters

1. Maturity through experience, not just speech

Your characters might sound older because of what they've been through, not just because they use fancy vocabulary or speak in deep philosophical metaphors. This maturity could come from:

The way they handle stress and responsibility

Their ability to assess situations logically rather than emotionally (though they’ll still have emotional moments)

The way they interact with adults (sometimes as equals, sometimes with hidden insecurity)

For example, a teenager leading a resistance group might have a sharp strategic mind, but that doesn’t mean they don’t feel the pressure of failure or secretly wish someone else could handle it. Let that complexity show.

2. Give them moments of being kids.

No matter how much responsibility they carry, they’ll still have cracks in their armour that shows their youth. Examples:

Stupid little habits (chews on their sleeves, obsessed with collecting something odd, still secretly sleeps with a stuffed animal, etc.)

Impulsive moments where emotions override logic (storming off, making reckless decisions, blurting out feelings they later regret)

A desire for normalcy—maybe they joke about things they missed out on or envy people their age who don’t have the same burdens

Even the most hardened of warriors is still a kid (in the context of this ask) and might make inside jokes, argue over dumb things, or mess around when the stakes aren’t high. Or they might make tactical decisions with the confidence of an adult, but forget to eat, sleep, or take care of themselves like a kid.

3. Leadership that feels earned, not forced

If your teens are in positions of power, show why they’re there. Are they the only ones willing to take charge? Are adults absent, dead, or untrustworthy? Did they prove themselves through skill or sheer survival? For example, you can make it feel:

Respected, not convenient—others follow them because they believe in them, not just because the story needs them in charge.

Hard-earned—maybe they had to fight for authority, prove themselves, or take on responsibilities that no one else wanted.

Lonely—leadership is isolating, especially for teens who are aware they’ve lost the freedom of childhood.

At the same time, they might struggle with things like imposter syndrome or self-doubt.

4. Age-appropriate emotional reactions

Even if they talk or act like adults, their emotional responses should remind readers that they aren't. They might:

Feel things too intensely (like anger, grief, and joy to the point of being consuming or reckless), like snapping in frustration when they’re stressed instead of handling things with full adult restraint

Have a skewed sense of consequences (thinking they’re invincible, or believing failure means everything is doomed)

Struggle with emotional control, like bottling everything up until they explode or lashing out because they don’t have healthy coping mechanisms

Maybe they can negotiate peace between feuding clans but are completely helpless when dealing with personal rejection; or they can keep calm under fire but cry when no one is watching. Things like this not only add depth to your characters, but remind readers that they're still babies.

5. Mature, but not omniscient

For instance, a fifteen-year-old might be commanding an army in battle but have no idea how to comfort a crying friend. Examples:

A teenager who had to raise their siblings will have strong leadership and nurturing skills, but might not know how to handle romance or peer friendships well

Still longing for normalcy in ways they don’t admit

Thinking they know everything, but getting blindsided by something outside their experience

6. Let them have growth arcs.

One of the best ways to balance maturity and youth is to show them learning. Maybe they act like they know everything, only to be humbled by a mistake; or assume they have to be strong all the time, but later realise they need help too and it's alright to ask for it. This'll remind the audience that while they may be wise beyond their years, they are still growing.

7. Inexperience

As many skills and responsibilities they may have, a teenager will likely still be inexperienced. For example:

They need to make difficult decisions since they're in leadership positions, but still struggle with the weight of it

Don’t yet have the emotional distance to detach from losses

Competent in battle but still hesitate before killing

8. Speech, humour, & interests

A mature teen might be more articulate and well-spoken, but they won’t sound like a university professor. They might still joke, use slang, or get snarky when comfortable.

It's also important not to forget about personal hobbies and random little things they get excited about. They may be world-weary, but they can still be dorky about their interests.

9. They might not have all the power.

Even if they hold leadership positions, adults might still underestimate them or try to manipulate them; they might be technically in charge but constantly fighting to be taken seriously, or believe they have control over their own lives only to realise they’re still at the mercy of the systems around them.

---

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writers on tumblr#writer help#character development#writerscommunity#writing community#story writing#on writing#deception-united

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about writing dual POVs.

Writing a novel with a dual point of view where two different characters share the role of narrator can add depth, tension, and complexity to your story, but it also comes with its own set of problems and challenges. Like, how do you ensure clarity between perspectives? How do you keep both characters engaging? And most importantly, how do you make both narratives feel like parts of the same novel instead of two separate stories? Here are some tips and strategies to consider, before and when writing.

1. Ensure both POVs are necessary.

A dual POV should serve the story, not exist just because it seems interesting. Before committing to this structure, ask yourself:

Could the same story be told just as, or more, effectively from just one perspective?

Do both characters bring viewpoints that are unique and essential to the plot? What does this character’s POV add that we wouldn’t get otherwise?

Does each POV contribute to the novel’s themes, conflicts, or emotional depth?

Does it move the plot forward, or is it just there because I like this character?

If the answer isn’t an easy 'yes,' reconsider whether both POVs are truly needed. For example, in a romance novel, it might be better to only include one POV, since knowing there are feelings from both sides can take away tension and make it boring for the reader.

2. Choose a primary protagonist.

Even though you're going to be featuring two points of view, it’s essential to have one central character who anchors the story. This character serves as the thematic and emotional core of your book. Consider:

Which character’s perspective starts the story?

Which character’s perspective ends it?

Who undergoes the most significant transformation?

While both POVs should be compelling, having one clear primary character ensures your narrative remains cohesive.

3. Make each POV distinct.

Readers should be able to identify whose perspective they’re in without needing a chapter heading to tell them (although this is helpful and I do recommend including an indicator like this). You can differentiate this through:

Voice & tone: Their word choices, speech patterns, and internal thoughts should reflect their unique personalities. (See my post on character voices for more tips on this!)

Observations & focus: What each character notices and how they perceive the world will differ based on their backgrounds and biases. What details do they focus on? How do they process emotions? For example, a noble-born strategist will notice different things than a street thief. Sentence structure & style: Ties back to voice & tone—a poetic, introspective character might have longer, flowing sentences, while a blunt, action-driven character may have short, clipped phrasing.

**If you can open to a random page and easily recognise the character’s voice, you’ve done it right.

4. Interweave the two arcs effectively.

Both characters should have distinct yet interconnected arcs—even if they don't meet or interact until later on, or at all, their stories should be able complement or contrast each other in a way meaningful and comprehensible for the reader. Examples:

Parallel arcs: The characters face similar struggles but react differently (shows contrasts).

Intertwining arcs: Their paths cross at key moments & affect each other’s journeys.

Foil dynamics: One character’s success may mean the other’s failure—builds tension and stakes.

5. Smooth transitions

Switching between perspectives should feel natural, not jarring. Consider:

Consistent switching: Like alternating every chapter or at key turning points, or making one character dominant (the main focus) and the other occasional (slipping into it when necessary).

Strategic cliffhangers: Ending one POV on a suspenseful moment can keep readers engaged through the shift (though be careful not to make it so that the reader is skimming through one POV just to get to another).

Mirrored/contrasting scenes: A reveal in one POV can recontextualise a previous scene from the other.

6. Avoid head-hopping.

This is when you suddenly switch between characters’ thoughts in the same scene without a clear break. This can be jarring and pull readers out of the story.

Bad example: Lena glared at him. She was furious. Why didn’t he understand? Jonah sighed. He wished she would just listen.

You can't tell whose head we're in, and even if it was indicated at the start of the chapter, it makes it confusing and frustrating.

7. Build suspense

A well-timed POV switch can escalate tension rather than just pass the baton. Examples:

Character A is walking into a trap; meanwhile, Character B is on the other side of the city, knowing but unable to warn them (creates dread).

One character’s assumptions might contradict reality. (For example, a spy might believe their cover is intact, but another POV reveals they’ve been exposed.)

Character A misinterprets Character B’s actions as betrayal. Switching to B’s POV clarifies their true, but hidden, motives (creates emotional whiplash).

8. Deeper character exploration

Dual POVs can let readers experience both sides of a relationship, rivalry, or power struggle in ways a single POV can't. Examples:

Character A sees themselves as a hero, but Character B’s POV reveals their arrogance (unreliable narration).

Different emotional reactions—the same event might be tragic for one but a relief for another.

Common Pitfalls

Dual POVs might not always be appropriate for your specific narrative, and could:

1. Remove tension.

I briefly mentioned this, but one risk of dual POVs is reducing suspense, especially in genres like romance or mystery. If readers see both sides of a conflict, they might lose the uncertainty that drives engagement. However, you could try:

Using unreliable narrators

Keeping certain information hidden from one POV

Ensuring there’s still conflict and misunderstanding between the characters

Switching between past and present

Keeping one POV until the climax or for a specific plot twist, which can be revealed through a different POV

2. Break story flow.

If one character’s arc lags behind the other’s, readers may get frustrated when switching perspectives. Ensure each POV maintains momentum and contributes to the overarching plot.

3. Make readers favor one character.

If readers strongly prefer one POV, they may skim or disengage during the other. To avoid this, make sure both are equally compelling, both characters have stakes that feel urgent and meaningful, and each has their own distinct emotional arc that readers will be equally invested in.

4. Make it redundant.

If both characters are just retelling the same events with minor differences, the second POV becomes unnecessary. To avoid this, use POV shifts to enhance the story, not just repeat it. You can use the second POV to:

Show what’s happening when the other character isn’t present

Reveal secrets, misunderstandings, or unreliable narration

Build dramatic irony (let the reader know something one character doesn’t)

Happy writing!

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writing techniques#character development#writing community#on writing#writers#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#dual pov#deception-united

201 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! weird question, but how do i write my make character receiving… ahem… oral?

i need something that sounds better than the typical “it felt good, he moaned”

sorry if this was weird!!!!!!!!!!

hi, thanks for asking! writing intimate scenes like this can be hard, and it’s easy to fall into clichés or make it sound mechanical. here are some quick tips.

focus on sensation. describe how it feels rather than flat-out stating how it's making him feel, if that makes sense

breath hitching, heat coiling low in his stomach, white-hot pleasure, etc.

body language > direct statements. instead of saying things like "he moaned," show his reaction.

does he tense up? does his grip tighten on the sheets or their hair? does his breath stutter?

bottom line is, focus on physical reactions to convey what you want.

i do have a previous post with more in-depth tips that you might find helpful, so feel free to take a look at that as well! here:

❤

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writing smut#deception-united

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!! I’ve started writing a novel and i have a character that is fascinated by another character and is in complete awe of them but as i am writing it keeps bordering love or attraction, could you tell me how to write deep admiration without it sounding too much like love or a crush?

hi! just posted an answer to a similar ask, feel free to take a look (here) ❤

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

How can i write deep admiration and approbation without it coming off as love or attraction

Hi, thanks for asking! There’s a fine line between admiration and love, but one that can be easily blurred. Here are some tips to avoid this.

Writing Admiration Without Attraction

1. Focus on respect, not yearning.

Romantic feelings or attraction often carry an element of longing—a desire to be closer, to be noticed, or to connect in an intimate way. Admiration, however, is more framed around respect. The character isn't dreaming about the other person or fixating on them in a way that feels personal, but is awed by their skills, intellect, principles, or character. In other words, focus on accomplishments and character rather than physicality.

Ex: Instead of lingering on their eyes or the curve of their smile, noticing things like their determination in the face of hardship, their intellect and the way their mind works, their unwavering principles in a corrupt world, their influence on others, how they inspire or lead, wisdom, bravery, dedication to a cause, etc.

2. Use language that shows reverence, not intimacy.

Words matter. If you use words associated with romance (captivating, alluring, intoxicating), odds are readers will assume romantic feelings. Opt for other words that suggest respect and awe instead:

Ex: Words & phrases like dignity, grace, wisdom, fortitude, resilience, unbreakable will (admirable qualities that one may aspire to achieve themselves).

3. Frame it as aspiration, not infatuation.

A great way to separate admiration from romantic attraction is to show that the character wants to be like the person they admire, not with them. This shifts the focus from desire to aspiration, which admiration often stems from. The idea that the person embodies something the admirer values or wishes to cultivate shifts the focus from them to their influence and how they affect and inspire others.

4. Be careful with body language.

Physical descriptions can quickly veer into romantic territory if you’re not careful. Rather than focusing on lingering touches, physical perfection, or other body language that could be interpreted otherwise, have it signal respect or camaraderie. A good rule of thumb: admiration respects distance, attraction tries to close it.

5. Show admiration through actions, not just words.

If a character admires someone deeply, they don’t always need to wax poetic about it internally. Let their actions demonstrate it:

Ex: Seeking their advice or opinion, defending them if others speak ill, following their advice, trying to emulate them or model their behaviour, feeling a sense of privilege for witnessing their greatness, etc.

---

I procrastinated on this one for a bit, but hope it helped nonetheless. Happy writing!

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#writers on tumblr#writer help#deception-united

318 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello fellow human

i wanna write smut but I suck at writing in general

Hi, thanks for asking!

Writing Smut

1. Describe, but don't get too poetic.

It's always important to have sentences that flow well and use descriptive language no matter what it is you're writing:

Ex: Rather than "He kissed her. She gasped. He touched her thigh," use more sensory language like "His mouth traced a slow path upwards, heat following in its wake. She exhaled sharply, fingers curling into his shirt" etc.

However, something I've noticed some writers tend to do is get too metaphorical with it, and as a reader, it frankly makes me uncomfortable when I read things like 'their bodies tangled together in mother nature's sexual slow dance' or idk.

2. Know your characters.

Smut isn’t one-size-fits-all. When writing a scene, consider their personalities, history, experience, and emotional state, and make it reflect that. For example, a shy character usually won’t become dominant all of a sudden unless there’s a reason; or a guarded character who typically resists vulnerability might be more awkward, unsure, or reluctant at first. Also consider their communication style (are they verbal? Do they tease? Do they hesitate or take control?) Bottom line is, make it more character-driven.

3. Avoid getting overly clinical.

Focus on sensory details rather than the mechanics: don't just list actions like a biology textbook. "He inserted X into Y" isn't hot—describe feelings instead (heat pooling in the stomach, the burn of a touch, hitch of breath, rustle of fabric, etc.).

4. Consent & power dynamics

Even in dark or rougher scenes or the wildest fantasy settings, it's important to have clarity on consent (unless the lack of it is the point). If your character's don't communicate at all, or if something feels off, the scene can easily turn uncomfortable or confusing. A character might want to be overpowered or controlled—but the reader should always know it’s wanted.

5. Word choices matter.

Avoid overly clinical words like "member", but also avoid purple prose. You don’t need to turn into a thesaurus and call it "his throbbing sword of love and desire" (please) but you also don’t want to be so vague that no one knows what’s happening. Overall, keep it natural; if you’re cringing while writing, reconsider.

6. Before & after

Have some buildup. If they go from casual conversation to ripping each other’s clothes off with zero transition, it’s gonna feel flat and likely confusing.

Aftercare is important as well. Once it's over, add a little moment of tenderness, teasing, a shared cigarette, something. Or maybe they don't bask in the moment and immediately get dressed like nothing happened and go their separate ways (it all depends on your characters, their relationship, and the narrative).

___

Aside from all this, it's important to get comfortable with writing first. If you feel like you suck at it, smut might not necessarily be the best starting point—you're not just describing bodies, but have to take into account the pacing, emotion, tension, flow of action, all that. You don’t need to be a literary genius, but it's good to have some sort of a foundation. If you feel unprepared, try practicing with writing simple, mundane scenes, like a character drinking coffee or two people arguing over something petty. If you can describe that in an engaging way, describing more complex scenes will seem much less daunting. Critically reading similar scenes to what you want to write in books or fanfics can also help gain a better grasp of the whole thing.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writing techniques#writing smut#deception-united

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is so incredibly helpful

A Free E-book on Writing Characters That Feel Real

A year ago, I sat down to write this book. At first, it was just an idea, a fleeting thought that whispered, Hey, maybe you should do this. But if I’m being honest? The only reason it actually exists today is you.

You, who kept showing up. You, who kept asking questions, sharing your struggles, and pushing me to keep going when I wanted to throw my laptop out the window. You made me believe this book was worth writing. So here it is. And it’s completely free on Amazon, because I want you to have it.

Now, This isn’t your typical “Here’s how to write a character” manual that tells you to slap on a few traits and call it a day. No, we’re diving deep into the messy, complicated, and downright chaotic process of creating characters who feel real, the kind who make readers laugh, cry, and scream into the void when they suffer.

What you’ll find inside:

🔥 Backstory – Ever met someone whose past didn’t shape them? Me neither. What happened to your character before page one? What traumas, triumphs, or late-night existential crises made them who they are?

"So you mean I have to give my character trauma?" Yes. Or at least something that matters. Nobody wants to read about someone who just woke up one day and decided to be interesting.

🔥 Motivation & Goals – What do they want? More importantly, why? What’s driving them forward or holding them back?

"So, can I just say my character wants to save the world?" No. You need to know what’s underneath that. Do they want to save the world because they failed to save someone before? Because they crave approval? Because they feel powerless and this is their way of taking control? Go deeper.

🔥 Relationships – Nobody exists in a vacuum. Who do they love? Who do they hate? Who’s their worst enemy, and who’s the person they’d take a bullet for?

"But what if my character is a loner?" Cool, but even loners have people they avoid, people they secretly miss, and people who haunt them. Nobody is truly alone.

🔥 Character Arc – People change. Or they don’t and that says something too. How does your character evolve (or refuse to) over the course of your story?

"Can my character stay the same?" Sure, if you want to show the cost of not changing. But readers love growth, whether it’s for better or worse.

🔥 Personality, Voice & Expression – Strengths, flaws, quirks, habits, the little things that make them Human.

"Can I just give them a scar and call it depth?" No. A scar is cool, but why does it matter to them? Do they trace it when they’re nervous? Does it make them self-conscious? Does it remind them of a promise, a failure, a night they wish they could forget? The details mean nothing unless they mean everything.

This isn’t some dry, theoretical textbook. This is a no-BS, straight-to-the-heart guide to crafting characters that breathe, bleed, and break hearts—characters that matter.

📖 Get your free copy on Kindle now! (Here On Amazon!)

And seriously—thank you. This book wouldn’t exist without you. 💖✨

#reblog#writeblr#writing#writersociety#writerscommunity#creative writing#free ebooks#writing resources#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#character development#writers of tumblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!! I'm struggling to write a slow build up to a crumbling relationship between a father and daughter. I don't know how to pace it or space things out.

He doesn't understand her and doesn't try to. I wanna make him a self centered prick.

And I want her to put some effort into trying to fix it, but he's being a complete man child.

(sorry if this is a bad description)

Hi, thanks for asking! When writing a relationship eroding over time, you want to consider pacing and emotional build-up to make your readers effectively feel the weight of it all. Here are some tips!

1. Establish initial cracks

Before things fall apart, the readers need to see that they were never truly whole in the first place—maybe he was never particularly attentive, or she’s always felt like she had to work for his approval. Even if they have good moments, try making them feel fragile, like a peace treaty on borrowed time. Consider small but telling moments that are just enough for the reader to notice the imbalance (they don't need to be dramatic at first). Possible examples:

She shares something important to her, and he brushes it off or twists the conversation back to himself.

She’s visibly upset, but he makes it about his own stress and problems, leaving her unheard.

He talks at her, not to her (interrupting, correcting, dismissing her words, etc.)

2. Give her hope, then take it away

To make the build-up and subsequent devastation hurt, don't have her give up on him immediately, rather putting in the effort, believing he can change (ex: she plans a one-on-one outing, only for him to cancel last minute because something "more important" came up). The key here is for each failed attempt to cost her more.

At first, she might be frustrated but still hopeful ('maybe he just didn't realise' or 'he's probably just really busy'); then, she starts explaining herself more, trying to get through to him. Eventually, her patience will turn to exhaustion—she starts anticipating disappointment.

3. Let him prove himself undeserving

This is where he gets worse: not cartoonishly evil, rather willfully oblivious and self-centered. Maybe:

He acts like he’s the victim whenever she calls him out. Depending on how you want to portray him, you could involve gaslighting or victim blaming here. ('So I’m just the bad guy now?')

He takes her efforts for granted, never reciprocating or even noticing.

When she finally reaches a breaking point and stops trying, he acts shocked and offended, as if she is the one pulling away.

The more she gives, the more it will drain her, until she finally realises she’s given him all she can.

4. Realisation & distancing

By the time she stops trying, she isn’t even angry anymore; she’s just done. Maybe he does something thoughtless that, months ago, would’ve sparked a fight, but instead of arguing, she just doesn't react or care, since she's stopped waiting and hoping for him to change. If their relationship's crumbled to the point of her leaving, maybe she lets his calls go to voicemail or ignores text messages—it reaches the point that if he ever does actually wake up and try to reconnect, it’s too little, too late.

___

Keep in mind that what can make this so painful isn’t just that he’s a bad father, but that she wanted him to be better and tried and hoped and put effort into their relationship which all went ignored and wasted. So try to space it out, letting her fight for him before she realises he's not worth it; and when she walks away, it's feels less like liberation than a funeral for something that could have been a beautiful and healthy relationship if only he'd cared enough.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writing relationships#writing tropes#deception-united

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i’m writing a slow burn and i was wondering what are good ways to make two very socially awkward / recluse characters get closer over time?

(for reference this is a lady and her servant, and they both mostly interact with just each other)

thanks a ton :)

Hi, thanks for asking! Here are some tips + sample progression of such a dynamic.

Writing a Slow Burn Between Introverts

1. Establish initial barriers

Before your characters can grow closer, define what’s keeping them apart—are they both just deeply introverted, or is there a reason for their reservedness?

Ex: Trust issues from past betrayals, feeling unworthy of emotional connection, rusty social skills from years of solitude, etc.

2. Start with silence, but make it loud.

When two people aren’t used to or don't like socialising, their early interactions will be filled with everything but words, just coexisting at first: glances held too long, hands hesitating before passing an object, the way one lingers in the room just a second longer than necessary. Play with body language and what isn’t said—let the silence stretch, let it be heavy or awkward or oddly comfortable.

Ex: The servant quietly refills the lady’s tea without a word, the lady listens to the servant bustling about but never acknowledges them directly, etc.

3. Small acts of consideration (that they don’t know how to talk about)

Being socially awkward, your characters may struggle with direct displays of affection, rather preferring to show that they care in indirect ways. Let their bond develop through subtle acts of kindness and understanding to show a consideration past mere duty.

Ex: The lady notices the servant’s hands are rough from work and, without a word, leaves a tin of salve in their quarters; the servant uses it but never mentions it, instead starting to do little things in return, like bringing her a fresh quill before she runs out or remembering how she likes her blankets arranged.

4. Accidental intimacy (Oh no, that was personal)

They're so used to keeping to themselves that when something personal slips out, it’s a Big Deal. The key here is discomfort—neither of them is used to this kind of closeness, so they’ll be hyper-aware of every small meaningful moment (until it starts to feel normal).

Ex: The lady absently mentions an old childhood memory, only to realise she’s never told anyone that before; or the servant instinctively reaches out to steady her elbow as she steps over uneven ground, and they both freeze in realisation.

5. Routine

Since they primarily interact with only each other, their daily routines become the foundation of their relationship—at first, they may stick strictly to their roles (lady gives orders, servant obeys), but over time, that routine could give way into familiarity and then further intimacy.

Ex: The servant lingers after delivering a meal, pretending to adjust something unnecessarily just to exist in her presence a little longer; or the lady begins asking the servant’s opinion on minor matters.

6. Forced proximity

You might want to consider this trope for characters like this, since, left to their own devices, they would probably spend years orbiting each other without ever making a move. You've already done this somewhat through the master-servant dynamic, but it would probably still be unlikely for one of them to be bold enough to make the first move. Throwing them into situations where they're even closer together will make them have to engage and could help move things along, pushing them past their usual interactions.

Ex: Getting trapped in a storm or stuck in a carriage together, or something needs doing for the completion of which they have to cooperate or rely on each other.

7. Awkward conversation = mutual understanding

Two socially awkward people are unlikely to launch into deep heart-to-hearts overnight, but that doesn’t mean they can’t bond. Let their conversations be stilted, filled with hesitations, unfinished sentences, and long silences—these awkward exchanges can lead to mutual understanding.

Ex: The lady asks a question, the servant panics and over-explains, and she finds their nervous rambling oddly endearing; or they blurt out something out of place and are horrified only to find that she's quietly amused rather than offended.

8. Vulnerability & protection

As their bond and feelings for each other grow, you might want to include moments of vulnerability to accelerate their emotional closeness.

Ex: The lady has a nightmare and the servant comforts her; the servant falls ill and, for the first time, she cares for them instead of the other way around; or she defends them against an accusation, even though she shouldn’t.

9. Accidental (& overanalysed) touch

For characters who aren’t used to closeness, even fleeting touches can show the tension or longing without either of them knowing exactly what to do with it.

Ex: Fingers brushing when one hands the other something, both pretending not to notice/spiralling into internal panic; the servant helps her adjust a piece of jewellery.

10. Mutual comfort

Eventually, they might start noticing that they speak more freely with each other than with others, or finding themselves wanting to stay in the other's presence a little longer than necessary—generally coming to the realisation that they're comfortable with each other in a way they aren't with the rest of the world, finally reaching the point where they can just be with each other, without fear or hesitation.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#slow burn#writing romance#romance#character development#character relationships#writing relationships#writing tropes#deception-united

144 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I have a question I'd like to ask: do you know how I can write a truly terrifying villain who's a manipulative abuser masquerading as a charitable sweetheart? (this ask might get dark)

My story's protagonist, Karina, is trapped in an unhealthy relationship with her older sister, Mina (otherwise known by her stage name Aphrodite) who treats her like a tool and constantly uses various cruel methods (emotional manipulation, lies, verbal and physical abuse, memory-altering, victim-blaming, using innocent lives as leverage, etc.) to ensure that she never leaves her despite Karina desperately trying to.

Mina puts on a mask of being a gentle beauty but is, in truth, a cruel and heartless person who is desperate to not be a "#2". She is fiercely jealous and resentful of anyone who (she believes) has a better life than her, especially women. Many know her to be the humble founder of a charity association but, unbeknownst to the public, she also owns a "nightclub" where corrupt(ed) individuals are allowed to indulge in their twisted desires and torture anyone —including her sister— in various horrific ways.

Hi, thanks for asking! To craft a manipulative villain like this, who manipulate others to the point of warping reality itself, you need to build layers upon layers of deception. What makes Mina, your antagonist, so terrifying isn’t just what she does but how inescapable she is, how deeply she's embedded herself into Karina’s mind, and how the world adores her to the point of even her victims themselves having moments of doubt. Here are some tips!

Writing a Secretly Manipulative Villain

1. The most terrifying monsters are the ones who look like heroes.

A great manipulative villain isn’t just someone who tricks the world—they trick the reader, too. Someone like Mina must be so convincing and sincere that even when we’re inside Karina’s head, there’s a moment of doubt. You seem to have developed her well in this aspect, giving her a carefully constructed mask to hide her hunger for power and insidious grip on those around her.

Charm as a weapon: She should be effortlessly likable in public: warm tone, soft gestures, all types of charming. She should never act overtly villainous where anyone can see; rather, her manipulation should be delicate, precise, invisible to the untrained eye.

Philanthropy as a shield: The fact that she runs a charity makes her untouchable. If anyone accuses her, the world comes to her defense. After all, how could a woman so devoted to helping others possibly be a monster?

The gentle knife: When she does hurt Karina, it’s never an outright, obvious explosion (or if it is, it’s followed by masterful damage control). Someone like this would make Karina think it’s her own fault, sugar-coating insults, and delivering any punishment is delivered with a disappointed sigh that says I just want to help you or it's for your own good.

Also, emphasise the whiplash of her cruelty and kindness: one moment, she’s the doting older sister, telling Karina how much she loves her and how everything she does is for her own good, then the next, she’s turning cold, reminding her exactly what happens when she steps out of line. Abusers like her make their victims doubt themselves—Karina might keep telling herself, "maybe Mina isn't that bad" even when the truth is staring her in the face.

Prompt: "I try so hard to love you, but you make it so difficult. Do you even understand how much I do for you? How much I protect you from? No, I don’t think you do. You’re too selfish to see it."

2. Gaslighting

Rewriting the past: She reframes every act of cruelty as one of love, or as a result of Karina's own behaviour: if she hit her, it was because she was being difficult; if she was hurt at the nightclub, she should be grateful that Mina saved her from worse; and if she ever tried to escape, she’s reminded of all the times Mina “took her back” out of kindness.

Controlling the narrative: If Karina ever does try to confide in someone, Mina already has a pre-built counter-story ("Oh, Karina has always had such an active imagination. I try my best, but sometimes she gets these ideas in her head...").

Using love as a weapon: Mina makes Karina believe that she owes her everything, and that without her she would be nothing, telling her that the world outside is cruel and unforgiving and she’s safer right where she is.

An example of a character like this can be seen in The Housemaid by Freida McFadden (⚠️spoiler⚠️), in which one of the characters, Nina, has a manipulative husband who seems perfect until he punishes her for a minor inconvenience through torture, then twists it to make her believe it never happened and the near-tragedy that occurred afterwards was her own fault. She believes this and thinks she's crazy until the torture happens again, at which point it's too late for her to escape due to what he has on her. Gaslighting is one of the strongest weapons of someone like this.

3. The nightclub

A carefully curated circle: Mina shouldn't let just anyone into the club—rather, the people who frequent it are ones she’s selected, and considering she wants to keep up her front, they would likely be people with power and sins of their own who owe her something. They protect her because she protects them.

Using Karina as a puppet: Instead of just making Karina be a victim, she could force her to participate as well. It could start small with things like greeting guests or playing hostess, then escalate to using her to lure people in, making her watch, and overall making her complicit. Someone this sadistic might not settle for Karina’s own suffering, wanting to torture her further by seeing other people experiencing it and break her into something unrecognisable.

Prompt: Mina drapes an arm around Karina’s shoulder, guiding her through the lavish, dimly lit club. Her lips brush against Karina’s ear. “Smile. You don’t want to make our guests uncomfortable, do you?”

4. A villain who will never let go

The most horrifying aspect of Mina might be just the fact that she will never stop coming after Karina even if she does manage to escape.

The fear of leaving: Karina knows that even if she escapes, Mina will find her and plague her with not only threats or further torture, but apologies and public spectacles that will make others believe that Karina is just a troubled girl running from the only person who ever cared about her.

Escalating control: The moment Mina senses she’s losing Karina, she might escalate: at first, through guilt-tripping, then cutting her off from resources, friends, or potential allies, and violence, overall destroy Karina’s life so thoroughly that there will be nothing left to run to.

Public persona: Outwardly, make her seem too perfect; people love her. She's the kind of person others defend rabidly. Everyone being so convinced of her goodness makes Karina feels utterly trapped—because even if she does break free, who will believe her?

Hope this helped!

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#writing villains#deception-united

105 notes

·

View notes