In secular terms, evolution implies an ongoing process of gradually awakening to our potential. In religious terms, we may refer to this process by what theologians and religious philosophers have long since called the unraveling of theosis — also known as deification, divinization, apotheosis, or participation in God. All posts written by [email protected]

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Without Eugene England, I Probably Wouldn’t Attend Church

Reflections on the Growth-Promoting Gifts of Paradox

First, A Confession

Let me begin with a confession: I often don’t like going to church. I find the experience incredibly taxing, exacerbating, and just plain boring. Rarely am I uplifted. Frequently am I peeved. Paradoxically, and interestingly, I also find going to church one of the most redemptive experiences I am trying to learn to love. It is very difficult for me to articulate the origin, nature, and depth of this love-angst relationship. And to be honest, if I wasn’t aware of who Eugene England was, I probably wouldn’t appreciate the discipline of community that comprises church-going, nor respect its attendant paradoxes. Put differently,without Eugene England, I probably wouldn’t attend church.

This loaded, semi-provocative thesis needs unpacking before it’ll make sense to orthodox ears. Let me drill down a bit.

In 1986, Eugene England, a faithful, critical Latter-day Saint scholar, wrote a game-changing essay entitled, “Why the Church is as True as the Gospel.” Personally, this essay has had a huge influence on me and my relationship with the institutional Church. It has carried me through difficult times in my discipleship, given me a lot of hope, beauty and pragmatic bearing, and has provided invaluable perspective on how “not only to endure but to go on loving what [is] unlovable.” In short, it is an essay that I think all Latter-day Saints should read and become familiar with.

The Power of Paradox: The Gospel and the Church

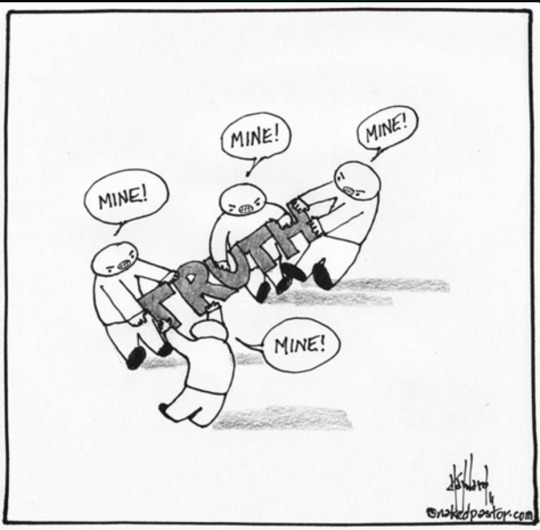

Much of England’s treatment of effective church-going meditates heavily on the power of paradox. Joseph Smith referred to the concept of paradox when he stated that “by proving contraries, truth is made manifest.” Half a century earlier, the poet William Blake had similarly observed, “Without contraries there is no progression.” Contraries, or oppositions, give energy, force and meaning to virtually everything.

Think about it.

The art you see in a theater, a museum, or historic site has risen from the tension of human conflict and opposition. Economic, political and social enterprises have and continue to emerge from competition and dialogue. Human life itself grows out of pain and controversy. Galaxies form spectacularly amid swirls of chaos and explosion.

The gospels, too, are awash with many paradoxical statements:

To be rich you must be poor. To be comforted you must mourn. To be exalted you must be humble. To be found you must be lost. To find your life you must lose it. To see the kingdom you must be persecuted. To be great you must serve. To gain all you must give up all. To live you must die.

Paradoxes, contraries, or oppositions can sometimes tempt us to think that two conflicting propositions will always be incompatible. Yet, it is often when we sacrifice traditional concepts and change our frame of reference that rival statements of paradox suddenly appear compatible.

A paradox, in other words, is not antithetical to the pursuit of truth, but in fact the very definition of it. In his acclaimed essay, “The Institutional Church and the Individual,” Bonner Ritchie stressed the importance of this pursuit: “By confronting the contradictory constraints of a system and pushing them to the limit, we develop the discipline and strength to function for ourselves. By confronting the process, by learning, by mastering, we rise above.”

“It must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things” is thus a profound statement of abstract theology in our scriptures that describes how vital paradox is to the development of all living things.

From the perspective of paradox, England is armed to build a persuasive case for why the Church (the Work) is as true as the Gospel (the Plan). Upon first blush, this rings like a weighty contradiction that just can’t be. The principles of the Gospel are pure and ideal, we say, but the workings and people of the Church are weak and imperfect. As Hugh Nibley once recognized, “The Plan looks to the eternities and must necessarily be perfect; but the Work is right here and is anything but the finished product.” We seem to envision the Gospel as a “perfect system of revealed commandments based on principles which infallibly express the natural laws of the universe,” says England, but in reality all we have is merely our current best understanding of these principles, which is invariably limited and imperfect. Such an unwieldy divine-human paradox seems to put us in a spiritual straightjacket.

In what world can the Church and the Gospel be as “true” as each other?

Consider first how England uses the word “true.” He’s not bearing down any sort of indexical relationship nor conflating the two with some grammatical set of historical, empirical, or metaphysical propositions. His approach is much more pragmatic and existential in nature. What he means is that the “Church is as true — as effective — as the gospel” because it is precisely the place where we are given a genuine and participating feel to practice the Gospel in specific, tangible ways. “The Church,” he says, “involves us directly in proving contraries, working constructively with the oppositions within ourselves and especially between people, struggling with paradoxes and polarities at an experiential level that can redeem us.”

Callings, for example, draw us into a very practical, specific, sacrificial relationship with others. We learn firsthand how exasperating people can be, how demanding and nagging human diversity often is. Paradoxically, when we work with, serve, and are taught by those who differ from and sometimes frustrate us, we allow ourselves room to become more open, vulnerable, gracious, and willing. When we grapple with real problems and work towards practical solutions with those we serve, we are pushed “toward new kinds of being in a way we most deeply want and need to be pushed.”

The “truthfulness” of the Church thus lies in its ability to effectively concretize the principles of the Gospel, bring them down to earth, down into our bodies, our hearts and minds, giving them corporeal form, thereby allowing imperfect agents to painfully develop divine gifts. And the better any church or organization is at drawing out these gifts, the “truer” it is.

Remember this point: “truth” from England’s perspective gains its meaning in relation to the quality of life, or being, it inspires.

England’s argument follows the late eighteenth century existential tradition of how our pursuit of truth must exist in relation to a more pressing concern than mere historical, metaphysical or scientific claims. Truth must lead us to a certain quality of life and quality of character —what philosophers and theologians have long since called “the good life.” Truth must bear down on the particular, not the general; the concrete, not the abstract. England isn’t elevating one over the other per se. He’s merely exposing the myth that the Gospel (the general) can somehow be salvifically divorced from the Church (the particular), as if pretending that sheer academic knowledge alone, and with it the freedom from dealing with the querulous, niggling life-pulse of a congregation, were sufficient for redemption.

This paradigm, he contends, is misguided.

Abstract and Practical Gospel Living

There are many principles of the Gospel that are conflicting and paradoxical and can’t be effectively lived in the abstract. They must instead be faithfully embodied for them to prove redemptive. Agency and obedience, for example. These two foundational principles are in dynamic tension with another, creating a critical paradox in the Church for how we work with others who may offend us or exercise unrighteous dominion. If God’s anointed leader makes a decision without inspiration, are we bound to sustain that decision? The friction created between obedience to authority and obedience to agentive conscience sparks the creative energy “we need to allow divine power to enter our lives in transforming ways.”

These moments of friction call us to walk an authentic path carved out between two easier paths of blind obedience and blanket rejection. They reveal the truth of how to act and not merely be acted upon.

England continues: “It is precisely in the struggle to be obedient while maintaining integrity, to have faith while being true to reason and evidence, to serve and love in the face of imperfections, even offenses, that we can gain the humility we need [to] …literally bring together the divine [the Gospel] and the human [the Church].”

The confession I began with is a good example of the tension I feel each Sunday while wrestling with these principles in the pews. I’ve attended many wards throughout my life, each replete with a common brand of middlebrow, prejudiced, intellectually unsophisticated types whose opinions I oftentimes vehemently disagree with. I’ve struggled endlessly with socially scripted class discussions, platitudinal public prayer, legalistic watchdogs, and those who proof-text the scriptures to support some idolatrous claim. The people in the Church, to put it mildly, have exasperated me to no end. And it is these very “exasperations, troubles, sacrifices [and] disappointments” that characterize my experience at church that England says “are especially difficult for idealistic liberals to endure.”

But herein lies the power of his thesis: it is precisely in our exasperations with other people at church — those who sometimes piss us off — where we are invited to enter a “school of love,” one that enables us to painfully grow in Christ-like character by “loving what [is] unlovable.”

How might this work?

Not many people I imagine willingly choose to build relationships with those whom they have very little in common with, or who have vastly different temperaments. Paradoxically, when we struggle to serve people we normally would not choose to serve (or possibly even associate with) we enter into a very specific, sacrificial relationship with them that allows us to exercise divine muscles that otherwise may have remained dormant. To accept this challenge, to enter this school, is to potentially become “powerfully open, empathetic, vulnerable people, able to understand, serve, learn from, and be trusted by people very different from [ourselves].”

By entering this school of contraries, we give birth to divinely needed gifts such as patience, compassion, mercy and forgiveness.

These gifts are forged in the furnace of paradox.

Terryl and Fiona Givens have also rightly backed the paradoxes at play in England’s thesis. Sometimes we “imagine a religious life encumbered by fallible human agents, institutional forms, rules and prohibitions, cultural group-think and expected conformity to norms.” Sometimes we “insist on imposing a higher standard on our co-worshippers” by wishing that their prejudices and blind spots did not inflame us. We wish others could simply think about the Gospel like we do. Practice it like we do. Yet when we “submit to the hard schooling of love” the Church offers, we’re able to experience wards and stakes that “function as laboratories and practicums where we discover that we love God by learning to love each other.”

The Church’s perceived weaknesses, paradoxically, are thus actually its greatest strengths.

Each imperfect encounter we experience at church will no doubt stretch and wear down on us, and yet if endured with the right attitude, can act as the very experience, the very gift, needed to become more Christ-like.

If this sounds too sentimental, too lofty, if we would prefer instead our worship services to constantly align with what “we get out” of a meeting, we may be missing the point. England argues, “If we constantly ask “What has the Church done for me?” we will not think to ask the much more important question, “What am I doing with the opportunities for service and self-challenge the Church provides me?” If we constantly approach the Church as consumers, we will never partake of its sweet and filling fruit. Only if we can lose our lives in church and other service will we find ourselves.”

It is a fairly easy exercise to analyze these principles from afar, criticize and make stupid those whose opinions we don’t share. Sometimes we remain too bookish, academic, or idealistic, with little hands-on involvement for the ongoing life of faith. If knowledge and books and abstract learning is where we tap real meaning, and have not charity, the principles we claim to admire so much will have the hollow, disembodied ring of “sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.” We will not know the character-transforming truths that the Church means to imbue us with. It is only when we step into the arena with others, play the game, tussle with their ideas, wishes, and misinformed biases, and try to give constructive answers, that we come to slowly learn the truth of the child-like phrase, “I know the Church is true.”

Or rather: I know the Church is an effective vehicle for divine endowment, despite of, even because of, its very real and imperfect people.

And here is Mormonism asking us to do just that:

Step into the imperfect arena. Wrestle with our leaders. Create an embodied relationship with others. Maintain individual integrity in the face of pressures to obey and conform. Patiently serve those who irritate, bruise, thwart and offend. Love obedience and agency — learn not to resolve their tensions in favor of one conflicting set over the other. Rather, learn to transcend them in our own customized ways while still remaining true to ourselves and our community. Remember, it is not about blind obedience or wholesale rejection. It is about walking the harder path carved out between the paradox. In doing so, we develop divine character in creative ways that no abstract system of ideas (uncoupled from service) could ever produce.

By acting within the zone of this paradox, balancing our individual conscience while serving others and sustaining church leaders, we open doors to prove contraries and encounter truth in tactile ways.

But Really, How Necessary is Church?

Can we not find a framework for practicing divine gifts such as mercy, humility, patience, and service in any number of settings? Of course we can. The Church has not cornered the market on what it means to be a good person nor to practice goodness. All faiths and secular walks of life can be receptive to the larger world of truth and beauty and moral goodness.

Ok, but if the Church doesn’t provide unique opportunities for spiritual practice that can’t be obtained elsewhere, why go at all?

When England takes a hard, all-or-nothing line on this question by evoking the traditional, orthodox answer that the Church has the authority to perform essential saving ordinances, his response is less than satisfying. However, there’s another approach that hides in the margins of his thought that better articulates why church-going (or some semblance of formalized community) can be a powerful boon for developing divine gifts.

To start, we might ask:

How often are most people sufficiently finding ways of their own efforts to love those they would normally not choose to love? And what value could there be in loving those we might consider as enemies?

One way to approach these questions is to consider the kinds of people we normally choose to associate with: If, for example, we choose only to surround ourselves with like-minded souls, people who think, feel, share and welcome our commitments, praise our ideas, flower our egos, what reward do we have? If we salute only those who salute us, if we love only those who love us, what good does hearing what we want to hear and having others confirm what we think we already know do for us? In truth, such groupishness is thoughtlessness. It remains too cloistered. Too bubbled. It runs the risk of creating an in-group echo chamber that appraises the status quo while at the same time teaching us to demonize those who disagree.

Admittedly, it is often in the nature of religious institutions to homogenize disparities and command conformity.

We might ask, but isn’t church just some big, sequestered parrot hall where everyone thinks the same, talks the same, gives unfettered assent to the same basic truth claims? Loyalty to an organization of course can and should be a very positive force, but it can also be a careless excuse to unload responsibility for our spiritual lives onto another. Bonner Ritchie has persuasively framed the dangers involved. Loyalty bent on unthinking conformity, he says, can be “a force which victimizes the individual, who feels freed from the burden of moral choice…We cannot allow the dictates of anyone to relieve the burden, pain, or growth that goes with individual responsibility.”

Indeed, religious institutions are enmeshed in shared networks of meaning and moral matrices that tend to lean towards conservative groupthink, sometimes to the point of giving off the appearance of complete doctrinal uniformity and a fierce, hive-minded group homogeny.

Such tendencies and appearances do not yield optimal religion.

We need the wisdom that is to be found scattered among diverse kinds of people, those who can pull us out of the status quo and be willing to create the dynamic tension needed to constructively fight the overbearing cultural orthodoxy. We need people in our congregations who revel in distinctions, variations, and differences, even those we’d deem as enemies — those we would normally not choose to associate with or love.

As Adam Miller contends, our love of people must be fearless, “marked by [our] confidence that every truth can be thought again — indeed, must be thought again — from the position of the enemy.”

To translate Miller into England’s terms: we must learn to love those who differ from us from the position of paradox. While those who differ from us can always be found both inside and outside the institutional walls of the Church, the practice of going to church can have a unique way of positioning paradox and framing our enemies in redemptive ways that might not be as readily available or instinctive on the outside.

Take the Church’s organization, for example.

That congregations are organized at the local level with a lay clergy and are bounded “geographically rather than by personal choice” cannot be overstated in how Mormon culture is shaped. Many members attend the ward they locally find themselves in rather than shopping around for the ideal, heavenly congregation. There are exceptions of course, but the significance of such standard Zion-building creates a particular kind of community that keeps us within intimate range of each other. We’re threaded together with the devout, the wayward, the liberal, the conservative, the feminist, the watch dog, the intellectual, etc. All kinds of disciples and potential enemies abound. We need all kinds of temperaments, too, to complement the full body of Christ, providing a cohesive enough space to bind our temperaments and differences into mutual loving ties.

Callings, as mentioned earlier, then provide constant encouragement, even pressure, to practice this spiritual binding; they help socialize, reshape, and care for people who, if stripped of them, would have less opportunity to make the sacrifices needed to grow and develop divine gifts. As the Givens put it, church attendance causes us to be “forced back to the renegotiating table by an unavoidable proximity” to iron out, smooth over, and make atonement with those who irritate, bruise, and deeply offend. The luxury to click the block or mute button, like on social media, is not readily available. We are commanded instead to be in harmony. To be at one. And that it is up to each individual to get there through prayer, service and ritual. Though difficult, the rewards of such a community are often, paradoxically, the empowered gifts of patience, mercy, humility, charity, kindness, and forgiveness.

Nothing here suggests that non-religious people living in looser communities with a less binding moral matrix can’t find opportunities to equally advance a charitable praxis. Many in fact do. I’d wager to bet there are actually many atheists who care for people better than some religious people do. The point rather is to raise the question of how often we naturally feel compelled to associate ourselves with people of vastly different temperaments, especially enemies. How often do we assume the hard work of paradox, take up the mantle of sacrifice and renegotiation, then strive to love, serve, cooperate, and bless our enemies in ways that better awaken divine gifts?

This question gets at a critical distinction that has less to do with pitting religion against secularism and more to do with how we might better encounter the growth-promoting gifts of paradox. As Patrick Mason has observed, “there are many orbital paths around the sun, but not all are equally suited to maximize opportunities for life to flourish.” We might, for example, join a book club, attend a conference, or volunteer at a homeless shelter. Each of these activities would help foster a sense of community and provide chances to put the gospel into practice.

For England, the Church is the best vehicle “for helping us to gain salvation by grappling constructively with the oppositions of existence.” He doesn’t draw out specifically why church attendance is the best medium above others. Nor does he deny other existing contexts to help promote the good life. He walks the harder path carved out between the paradox that suggests that while the Church may be in possession of sacred and distinctive truths, it by no means owns a monopoly on truth.

It might be noted here that religious ideology, interestingly, even paradoxically, does make one thing obligatory that secularism doesn’t always reveal as instinctive: it sacralizes and binds us to the enemy.

We must do as Jesus says: we must love our enemies, bless those that curse us, and do good to those that hate us. No escape hatch. No transfer to another school. As the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer realized, cheap grace would be to remove ourselves from the “discipline of [this] community.” This distinction, this obligation to love someone who hates us, is ground zero for the greatest manifestation for the life of paradox and divinity to thrive. It is the ultimate school of love that reveals, as England would say, a “frustrating, humbling, but ultimately liberating and redeeming” spiritual praxis. To the extent that people feel a disproportionately powerful gravitational pull of being repeatedly drawn out of their comfort zone to love, serve, wrestle with, and sacrifice on behalf of their enemies, these communities provide the best context to awaken divine gifts. Whether we experience this pull in religious or secular settings is secondary.

What matters first is that we actually feel and experience it.

On a Personal Note

If we need to go to church, like we need ethics or community, it is because we live with other human beings. Who would need church, alone on a desert island? The very act of congregating with others helps us achieve together what we cannot merely achieve on our own. And yet, to be educated and wise is to admit what sometimes we would rather not: however special we believe our spiritual customs are, no church, no God, no system or secular organization has conquered the world so dramatically as to universally compel all human hearts and minds to follow it.

We are all, in our own way, still searching for the ideal community — that place to best awaken divine gifts.

While acknowledging that my community experience at church is far from ideal, I personally have yet to find a better substitute than Mormonism to work through and redemptively prove contraries. I have yet to hear a more compelling story of human potential; one that frames the divine nature of paradox in more educative, purposeful, and ennobling ways to help me realize that potential. In this regard, England is a big hero of mine. He’s opened my eyes to the real redemptive possibility of what the Church means to engender within me. It’s full of nagging, irritable people, yes. The historical record is muddy and replete with skeletons, yes. Our leaders are liable to sin and error and actually have made egregious mistakes, yes. The gospels themselves are rife with contradictory tensions, yes. And our meetings are often so boring and soul-suckingly lifeless, yes. Does this all mean the Church is a scam? That it’s broken? That it doesn’t work?

I believe, like England, that all of these detours and complications are paradoxes that can behave more as blessings than curses, if we let them. They encourage me, though sometimes painfully, to sacrifice traditional concepts of the divine, take risks, become vulnerable, and reassess my assumptions. They become harrowing lessons that help me “engage in not merely accepting the struggles and exasperations of the Church as redemptive but in genuinely trying to reach solutions where possible and reduce unnecessary exasperations.” Church attendance is not about singing kumbaya or blithely picking marigolds while ignoring the Church’s myriad problems, failures, and contradictions. That would be “returning to the Garden of Eden where there is deceptive ease and clarity but no salvation.”

Rather, church attendance for me is about being stretched and challenged, even disappointed and exasperated, in ways I would never otherwise choose to be. I’m meant to be bruised and irritated by the flaws and limitations of others, then called to walk the harder path of working to serve and love and patiently learn from them. These experiences provide lessons in grace, charity, and Christ-centered moral improvement. And when accepting these sacred bonds and obligations to love the unlovable, I’m given “a chance to be made better than [I] may have chosen to be — but need and ultimately want to be.”

Living with contraries is a burden for both the religious and irreligious alike. England has merely reminded me of how to thrive in the face of paradox rather than be frozen by it. He’s provided a redemptive context that’s helped me “see and experience the conflicts [at church and elsewhere] in more positive ways.” He’s framed a particular kind of discipleship that to me is most worth believing and following. Without him, I honestly don’t know how well I’d endure on the path of discipleship.

Who knows, without Eugene England I probably wouldn’t know if the title of this post was meant as hyperbole.

#church#mormon#church of jesus christ of latter day saints#lds#religion#spirituality#eugene england#divine gifts#charity#humility#patience#love#paradox#oppositions#contraries#joseph smith#imperfections#gospel#service#agency#obedience

1 note

·

View note

Text

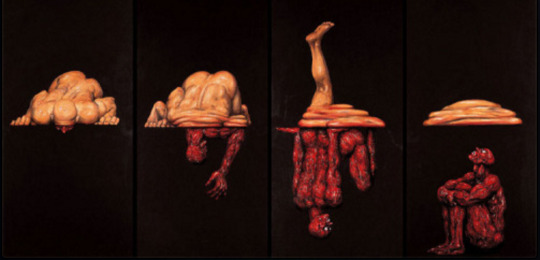

mother! — What the “Baby Moment” Signifies

Plumbing the Third Act

For weeks I’ve been haunted by the dark, dark, dark third act of Darren Aronofsky’s latest film. I remember feeling this way for weeks after Black Swan, too. It’s an emotion that stretches like vines, like fingers, pulsing and slithering its way about without letting go easily. Aronofsky, of course, has always had a gifted predilection for exploring darkness, but in mother! he really amps up the insanity, delivers a mind-blowing climax, and goes places I wasn’t entirely expecting, nor have seen in his previous work. It is difficult to describe how disturbing, how revelatory, this third act is, only to say that the more I think about it, the more I am moved by its madness.

Hence, the reason I am writing a second review — to fathom this madness, approach its depths, and explore its merit beyond first impressions.

Let me start with an observation that I hope will be uncontroversial: there is a big difference between being moved by something versus liking something. I did not “like” this film in the ordinary sense of the term. These ugly, hideous, hateable truths do not ask to be liked or loved. They only ask to be grasped and contemplated. It’s totally possible to grasp what Aronofsky is doing and still find the film hard to connect with, and that’s ok. It just means its themes did not speak to you. Personally, I cannot deny how tremendously moved I was by its themes, its dark wit, sadness, and cautionary sting. This distinction is an important one to parse because the depiction of shocking, revolting, nauseating acts in film is not always equivalent to their endorsement, likeableness, or celebration (unless of course you’re Eli Roth). Rather, these moments can be tantamount with societal mirroring, mourning, and meaningfulness (which Aronofsky’s work always attempts).

This observation, I think, has something to do with how we critically watch film and how we might watch them better. It also prepares the way for how this grisly third act functions, and what it signals.

As a devout theist who leans on the side of a culturally religious agnosticism, I was deeply moved by how the third act descends into a decline-of-civilization allegory, but one that especially critiques the sacrament of the Eucharist. To set this critique in context, be warned (spoilers ahead): nothing is more sinister, more taboo in cinema, than killing a child onscreen, let alone an infant. So, naturally, nothing is more seriously fucked up than hearing a blood-curdling snap of a baby’s neck, then watching his mother push through a crowd only to find his carcass lying on an alter, and a human horde feeding on his body. Symbolic of the murder and sacraments of Christ, these appalling sights and sounds will likely never leave my mind. Ironically, no sermon, ritual or doctrinal discourse will probably ever better teach me, on a visceral level, about what it is we church-going people are doing each Sunday while feeding on the sacramental emblems.

This is not blasphemy. This is admitting we’re all ungodly.

The baby moment, like so many other horrific acts of violence in this film, goes beyond mere symbolic gesture and religious iconoclasm. Aronofsky uses hyper-wacky emblems to get at deep, uncomfortable truths about how we humans always seem to destroy what we’re given. These emblems comment on the way we construct, then degrade, each other and our planet. As more and more strangers arrive and the story becomes increasingly calamitous, these emblems work extremely well because they mirror our world problems back to us. They also indict us on multiple levels, essentially holding up a middle finger to religion, environmental issues, society’s treatment of women, fame, consumption, the artistic need to create, and probably a lot of other things. This film should be weeping, wailing, and gnashing its teeth. We live during an insane time in human history. And we can be rightfully shocked by how mother and her baby are treated, but we would be damned to believe we aren’t in the human horde ourselves participating in its chaos.

That’s a terrifying realization, but an important one.

Who among us can’t identify with these menacing house guests? Who among us has not cast a stone, has not consumed, disgraced, taunted, ignored, vandalized, or polluted the earth and its people in someway? It would be easy to otherize these strangers, look around, point to someone else, and say, “Hell is other people.” It would be intellectually honest, however, to look inward and ask the penetrating question: “Are any of these strangers me?” What an ugly feeling that invites, even if only at a marginal level.

As a religious person asking why the third act is hard to watch, I think it’s because I’m able to discern how complicit I am in the human horde — both symbolically onscreen and literally in my congregation—one who feasts on the pure, saving emblems of Christ each Sunday. I’ve been complicit in joining the throng, adding to His unspeakable pain, grief and sorrow. I’ve felt guilt from bad choices and have sought remedy in the Eucharist. And in the Eucharist I have experienced a kind of soul-cleansing neo-cannibalism — the type that is detached from the eating of human flesh and is focused instead on a symbolic petition, one where I ask to be absolved and forgiven for all of my ills and wanton consumptions. In this state of mind, watching Aronofsky’s iconoclastic take on the Eucharist forced me to look deep into my soul and confront my own fears, weaknesses, and limitations. It was as though I was looking into a mirror being forced to reckon my own evil.

That was a powerful, albeit unsettling, meaningful experience.

As a secular person asking why the third act is hard to watch, I think it’s because I’m able to admit how society’s treatment of women and the planet at large is hard to watch. “It is a mad time to be alive,” said Aronofsky. He then listed all sorts of social, political, and ecological grievances that helped contribute to the creation of this film. Things like overpopulation, starvation, species extinction, human trafficking, schizophrenic U.S. climate change, the killing of baby dolphins, the refugee crisis, and our daily state of denial about all of the above. “From this primordial soup of angst and helplessness,” he wrote, “I woke up one morning and this movie poured out of me like a fever dream.” Similar to the baby moment, our pursuit of knowledge, power and mastery over the earth has brought about all of this angst and helplessness, destroying our once pure, guileless paradise of an earth.

All of these layers astound me — the religious, the secular, the referential — all stacking together to weave a bold, epic, challenging drama that won’t be for everyone yet ironically will be about everyone.

Many will avoid Aronofsky films after witnessing the cannibalistic devouring of a newborn child in front of his mother. I wouldn’t blame them either. The moment is so polemical that it will blind many from seeing beyond the symbol to what it signifies. And even if many do look beyond the simulacrum, it will be difficult to admit what its ugly truth mirrors about human nature generally, and each and every one of us specifically.

Interestingly, watching this film because you’ll hate it might be just as valuable as watching it because you’ll find meaning. Why? Because this is a film that wants to piss you off, wants to hurt you, wants you to howl and weep at its violence, but it also wants you to take a seat at its table for further discussion and debate, even if you vehemently disagree. And there is value in listening to those voices that heatedly disagree. This isn’t high-brow, deeply philosophical art. It’s actually quite accessible and wants you to think about hard but important issues. It’s also a film that follows a moral pattern familiar to Aronofsky’s previous work of punishing wickedness and mourning for the oppressed. For adept viewers, these patterns are angry yet compassionate howls that bemoan human brokenness. Thus, nearly everything in them should be viewed as a confirmation of some grieving truth.

If there’s one powerful takeaway from the third act, it’s that its grieving truths have yet to be written. The writing may currently be on the wall, but there’s still time to change course. This kind of cautionary art is exactly what we need right now to fuel important conversation. It’s a sacrament of anger, woe, and indictment that may lead to catharsis. You do not have to like or love or even admire anything about what this film depicts. But you’d be wise to take its messages seriously. You’d be wise to not allow discomfort to lead to disdain. And above all, you’d be wise to help write a new ending.

#film#film critique#philosophy#religion#Christianity#eucharist#sacrament#darren aronofsky#film criticism#mother#motherhood#secularism#climate change#environmetalists#politics#refugee crisis#human trafficking#bible study#the bible#poetry#allegory

1 note

·

View note

Text

mother! A Dark Allegory Sacralizing the Relationship Between Religion and Secularism

My vitals are oatmeal, my brain is slain, my soul is recovering from the syringe-injected wtf emotion. I haven’t been this excited since Aronofsky’s last release, NOAH (2014). And BLACK SWAN (2010) before that. And THE WRESTLER (2008) before that. And…you get the point. I’ve been team Aronofsky from the beginning (Sundance 1998, where he debuted PI). And, like all of his films, I’m destroyed in the most cathartic way as the credits roll. I’m reveling in the darkness of this feeling, this theater, paralyzed with intense awe. I have strong hope there’s light dancing somewhere inside my marred head, guiding me through the fiery, hellbent tunnels of what I just experienced. And MOTHER! is an experience!

What an absolutely sickening, messed up, brilliant cinematic masterpiece!!!!

Here is a film that only Aronofsky could’ve made, a film that contains a motherlode of rich interpretations, a symbolic maelstrom of ideas needing to be painfully birthed. The imagery stains, the ideas baffle, the third act impossible to predict, stomach, or prepare for. Believe me when I tell you: The barbs are real. And it makes for an ultra provocative kind of art because it’s so vulnerable, so sprawling, relevant and contentious in its reach. I might even describe it as a scalpel-sharp metaphor that rips, grinds, and eviscerates every faction of humanity ever to exist. No one is safe. Everyone is indicted. And Aronofsky, like the God of Genesis, is pissed with everyone, pissed with creation, pissed with politics and religion, with the overall state of the world, and he’s ready to burn it all down and start anew.

It’s a film that kind of plays out like NOAH — its prequel and sequel—but replaces the watery deluge with apocalyptic fire. It uses a biblical framework to shape and express a lot of political and humanitarian turmoil, and wraps them all together into one grand, outrageous, cyclical metaphor that might be difficult to grasp without a solid backing in these subjects.

MOTHER! isn’t a political or religious film per se as it is a human film commenting on the state of the world and how we endlessly abuse it. It evokes political and religious overtones to the extent of retelling the creation myth from a gnostic, secularized perspective. It’s also about a lot of other things — the social dynamics between artist, muse and feasting fandom, the creation of art itself, the downfall of civilization, of ecosystems, of human safety, the obsession with social media, tabloids and selfies, the portrait of a decaying marriage, the dangers of open-mindedness, and the list goes on. The interpretations will be myriad.

I found its retelling of the creation myth, however, one of the most moving, cross-pollinating attempts to ever sacralize the warring relationship between religion and secularism.

That retelling might go something like this:

The Earth — our world — is feminized, a Mother to all, a source of both nourishment for humanity and victim of male aggression.

Man’s aggression spawns from greed — from His dominion over Her (the Earth) — thereby becoming a catalyst for His belief in His dominion over Woman.

And so as the Earth is mastered, conquered, penetrated, plowed, tilled, burned, subdued, inhabited, and controlled, so is Woman.

Her paradisiacal garden is turned to waste, but Man continues to plant and labor and sow, and by brute sweat makes Woman yield — conceive.

The Earth — the Mother of all — “gives and gives and gives,” and in return gets invaded, pillaged, and raped, rebirthing the vicious cycle.

And Mother bears it, endures it, braves it, serves it, puts up with it.

Cruel male pagan gods divine this link between Mother and Earth, they gaslight it, and allow for the problem of evil to run amok for the sake of artistic musing and divine retribution for sin.

We’ve seen Aronofsky’s pagan sensibility shine before in BLACK SWAN, where anything that manifests itself to you may be a god, but in MOTHER! this paganism pulses and groans under the weight of what I found were five highly potent, timeless, relevant-in-2017 themes:

1) Mother, as an earthen vessel, holds the seeds to every noxious, selfish, unbending human crime within Her.

2). Mother, as an earthen vessel, may be pillaged, raped, and controlled by Man through “divine” rights, even corporation rights, unleashing the revelations and purgatories within Her.

3) Mother, as an earthen vessel, births, feeds, rears, nourishes, and puts up with a lot of vile, inane, intruding human garbage.

4) Yet Mother, even as this earthen vessel, can reach a furious, volcanic melting point, a chamber that can no longer contain the scalding pressure inside, exclaiming:

(!) “Enough!” (!) “No More!” (!) “The End!” (!)

5) Yes Mother! now as embodied, apocalyptic fury, can reject crude male taming and savagely roar back and boil over with destructive, unmatched chaos.

These themes stretch towards the sacred and the profane equally, finding home within the religious and irreligious alike. It’s a brand of home invasion horror that’s critical now. A story about our world bellyaching, roaring, reaching critical melting point — now! And what’s fascinating here is how Aronofsky transfers his past auteur portraits of hysteria and madness (think PI, BLACK SWAN, NOAH) over from his characters now suddenly to the lap of his audience. This will hit very close to home, and many will feel uncomfortable. In fact, the film almost plays out like Aronofsky’s middle finger to humanity at large, a venting frustration at how we mistreat each other and abuse our sacred, mother planet.

The result? Piqued reactions, confused reactions, zero neutrality, shifting accountability, and above all, a puzzle to be ciphered and querulously debated for years to come. This is the BEST kind of art. The kind that divides yet hopefully unites. It certainly is one of the most moving, thought-provoking films I’ve ever seen, one that hits personally close to home. I say this especially as a devout theist who leans on the side of a culturally religious agnosticism.

While this experience won’t be for everyone, I’d argue there’s a moral blade to the film that cuts DEEP, DEEP, DEEP into a problem that everyone is complicit in, right and left, black and white, male and female, me and you, but it isn’t necessarily preachy or scorning in presentation. Ok, it’s seriously messed up. But I reject any reading that claims Aronofsky is a misogynist or without compassion — especially for Jennifer Lawrence’s character — in part because this posture entirely misses the point by disguising a surface criticism as one that ignores the film’s larger, looming global symbolism, and the mighty realities for which those symbols stand.

MOTHER! might be the kind of art that liberals love to hate because some are unable to fathom how bad things being depicted is not equivalent to bad things being endorsed, but merely commented, mourned and reflected on. You need look no further for evidence of this than when Javier Bardem stated in an interview with USA Today, “Darren is the opposite of my character…He’s more into Jennifer’s character than my character. When I met him, I was like, ‘Where is this darkness coming from?’ Because he is the opposite of that. He’s nice, caring, generous, funny, very creative.”

MOTHER! has a moral edge to the extent that it forgoes pleasure, or punishes it wherever it occurs, to deliver a higher message. And my reaction to the film was one of total compassion, like a surgeon cutting into rotten tissue to find what parts are still salvageable. Put differently, Aronofsky plunges DEEP, DEEP, DEEP into darkness in order to find what shards of light may be hiding there, a skill he has always excelled at. His canon of work has proven how repeatedly and exceptionally acrid his ability is to peer into the abyss to yield enlightenment. And to make great art you have to go to the darkest place, the forbidden place. MOTHER! raises this cost as an insanely moving, nuanced presentation of what happens when you stare into the abyss — the forbidden place — too long.

If REQUIEM FOR A DREAM is Aronofsky’s required viewing for D.A.R.E programs, MOTHER! is his required viewing for earth stewards and married couples. If NOAH is Aronofsky’s biblical making of Genesis, MOTHER! most certainly unleashes his apocalyptic, unmaking, hellfire vision of Revelation. If PI is Aronofsky getting into the confined, mentally ill space of his characters, MOTHER! is him flipping that headspace burden over to his audience. If BLACK SWAN is Aronofsky doing hysteria-horror, MOTHER! is him making BLACK SWAN wishing it were difficult material for Sunday School. If THE FOUNTAIN is Aronofsky’s metaphysical view of history, MOTHER! is him exclaiming there won’t be any history left if our course goes unaltered.

And Aronofsky was right: No matter how many trailers/snippits I read prior to watching, NOTHING could prepare me for this sacred, unholy event. NOTHING! And don’t worry, my take here won’t spoil the madness you, too, will be put through (assuming you dare to step inside his theater!). And the third act. Good sweet mother Mary of all things blessed and disturbing, the third act! Good hell. Can’t wait to follow #mothermovie on that one. In sum, I’ve never seen anything like this. Will never be the same again. And will never answer a door knock again. Thanks a lot Darren.

#film#film critique#religion#philosophy#spiritual#politics#divine humanism#film nerd#poetry#darren aronofsky#allegory#bible study

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrestling with Prophets — There is Balance Between Full Assent and Full Dissent

I am not convinced that the intoxicating need to be right, to be certain, is supported by scripture. As mentioned earlier, Christ does command us “to be one” and to avoid “contention.” There are also several other passages that embolden us to “doubt not, fear not,” or when seeking knowledge to “ask in faith, without wavering.” However, I am not convinced these passages are trying to reduce the journey of faith into propositional beliefs made firm by dogmatic certitude. “We see through a glass darkly” and “Lord, help thou my unbelief” provide balanced expressions for those who live in doubt, even as they model an acceptance of mystery and surrender of cognitive certainty. Ideally, church is a place where we should feel safe to nurse our doubts in a community of saints who covenant to mourn with each other; yet, church often feels like a country club where we collectively show off how certain, with it, we are. This posture, I believe, stems from the unscriptural and dangerous assumption of infallible leadership.

Let me break this down by posing two questions: When a prophet speaks at a pulpit does he automatically speak for God? If someone doubts what a prophet says will he or she not be combatively received by their culture as subversive or apostate? Both questions reveal important doctrinal components of a lived-in faith. Mormons believe strongly in both prophetic authority and agentive authority. Put differently: How do I remain loyal to my Mormon community while at the same time remain true to my own conscience that’s been seared in the furnace of experience? Or, as Frances Menlove asked: “How free are Mormons to confront themselves? How free are they to question and analyze, to admit their strengths and weaknesses, their beliefs and doubts and problems with the Church?”

In a church where children are taught to sing “Follow the Prophet” and are assured that he will never lead the church astray, I think members harboring doubts or uncertainties are extremely limited in their ability to freely voice their concerns without being marginalized as insubordinate. In Sunday School, for example, the pervasive rhetoric of trust and certainty placed in our leaders can create tremendous fear in those who have contrary or countercultural opinions. The fear of looking disobedient offers too much friction for the soul in such daunting situations, that the options imagined are either to silently conform or leave the church.

I find this to be an extremely unfortunate position to feel pitted against, mostly because I believe there are many sincere members wrestling with doubt whose voices need to be heard. They can help us resist the temptation of certitude. They can help foster renewal and increase our humility. Sunday School far too often feels like a litmus-test of obedience, where the more conservative and squarely align our answers are to the brethren the more righteous and obedient we appear to be. If we are not completely turning over our agency to others in these moments, then we are pretending to place great worth on individual revelation, but only insofar that it inspires us to follow the teachings of the brethren. I believe that if our sustaining vote is to hold any meaning whatsoever, we must be able to voice our dissent in respectful, constructive, worthwhile ways.

The choice between blind obedience to the prophets and blanket rejection of their teachings is, I believe, a false dichotomy. As I have stated elsewhere, the church is not an all-or-nothing enterprise for me. There must be a meaningful balance between full assent and full dissent, where agency is not overridden but works to our advantage as we experience, think, struggle, stretch, and ultimately make our testimonies our own — not someone else’s. Anything less is just too easy, where either we’re asking for someone to keep our conscience, or, giving free reign to any impulse we feel and calling it our “conscience.” The first path is fueled by laziness, the second by ego. We are part of the House of Israel, whose name literally means “We who wrestle with God.” We do not simply acquiesce to every rigid, status-quo, stultifying pronouncement that prophets might make on behalf of God.

Like Jacob, we wrestle all night and perhaps even our entire lives with those pronouncements. And when done, we limp away, says Rick Jepson, “from the exhausting and injurious night as a new person, changed emotionally and spiritually.” We become “God-wrestlers,” confident and revitalized. This will often mean sustaining other fallible human beings while at the same time following our own inner-light that may lead us outside the comfort of traditional orthodoxy. It will mean admitting that doubt is not a final form of enlightenment but neither is sentimental projection. As Bruce Hafen admonished: “Those who will not risk exposure to experiences that are not obviously related to some Church word or program will, I believe, live less abundant and meaningful lives than the Lord intends.”

For these reasons I do not conflate my testimony of prophets and apostles with the unscriptural assumption that they are always right, or beyond criticism, or that vocally disagreeing with them somehow constitutes apostasy, or evil speaking of the Lord’s anointed. My loyalty to the church is not uncritical loyalty. To be intimidated otherwise would be for me to allow obedience to trump conscience, to deliberately give consent to an action or proposition I felt was wrong. My will is mine to give to Christ alone.

I hope that we can become culturally mature enough to forgo the temptation of turning our leaders into righteous celebrities who cannot err, both individually but especially institutionally. There is power uniquely designed in admitting that our leaders are not just fallible, but sometimes make egregious institutional mistakes while serving as God’s mouthpiece. But that’s ok. That’s expected. There is sanctifying power that can enter our souls when we forgive our leaders as they forgive us. That power helps us learn and practice the grace of forgiveness. It helps heal the pain that has been so disorienting when others have tried to defend what shouldn’t be defended, but simply owned. On extremely rare occasions, I have felt that power invite a special kind of honesty and soul-cleansing vulnerability into our meetinghouses. It dispels the competitive certainty of needing to be right and reminds me of what true religion looks like.

1 note

·

View note

Text

LGBTQ Orientation is a Given, Not a Chosen

Issues of gender and sexual identity are complex. I believe we are living in a very dark time with regard to the church and these issues. I have many LGBTQ friends, many of whom do not feel welcomed at church. They are extremely pained over the conflict between their conscience and the current teachings of the church. Even more, they are anguished by the many unthinking, insensitive, uninformed practices, beliefs, and attitudes we hold in our culture that dehumanize them. As one anonymous author wrote: “In a lifetime of church activity, I have yet to hear a single word of compassion or understanding for homosexuals spoken from the pulpit.” This wouldn’t be so tragic if it weren’t so true.

I disclaim any church posture that puts my LGBTQ brothers and sisters in the margins of a stigmatized identity. I also disclaim any posture that would make them feel that their orientation is something to be shamed.

LGBTQ inclinations are a given, not a chosen.

I do not believe LGBTQ orientation is a choice. No one willingly chooses to be gay or transgendered. And no one willingly leads a life targeted by fear, hate, intolerance, and other deplorable sentiments thrust upon them without honestly, and miserably, shouldering these crosses. In our church culture there is plenty of mythology tossed around that is frankly very destructive to our LGBTQ brothers and sisters, as well as their families. Just the other day during Gospel Doctrine, for example, an older man compared the LGBTQ community to the “wiles of Korihor.” I’ve also heard the rancorous Old Testament rhetoric of calling LGBTQ orientation an “abomination in the sight of God” and a “perversion of nature.” This kind of language is simply disastrous and is exactly the kind of posturing that leads to broken lives, families sundered, and even suicide.

I do not want to make it a point that having LGBTQ orientation is the defining characteristic of a person’s existence. We are all children of God first which means our primary identity is rooted in divine parentage. However, while I believe we choose which characteristics define us, there is something immensely disturbing about denying relations between two happy, monogamous, legally married, consenting adults, and then equating those relations with inflammatory rhetoric such as “sinfulness.” This posture is unrelentingly dehumanizing. It wants to characterize an LGBTQ lifestyle by unbridled lasciviousness, when in reality many people of LGBTQ persuasion just want an intimate, loving relationship like heterosexuals have. To insist on using such rhetoric is, I believe, to be swallowed up in the unforgiving deep of legalism. We can do better than this. We must.

Until heterosexual members — prophets and apostles not barred — are willing to bear the cross of celibacy themselves, or would be willing to stand proxy for the pain and anguish their gay and transgendered ward members feel, I find their privileged positions lacking in essential Christ-like virtues and feel no need to take their posturing seriously.

Do not misunderstand me.

I very much agree with the church that celibacy should be required before marriage in order to keep the law of chastity. I am also fully aware that there are plenty of celibate heterosexuals in the church. Some would even argue that the reality of single, celibate heterosexuals invalidates the uniqueness of LGBTQ orientation. However, I don’t think this posture is really sustainable. Single, celibate heterosexuals always have the hope to eventually meet someone (whether in this life or the next) who they can then spend the rest of their lives with.

LGBTQ people do not have this hope.

While everyone experiences the “desperation of temptation and the emptiness of sin,” LGBTQ people are essentially being told to carry an additional, unnecessary cross by being forever mortally denied basic human needs, intimacy, physical touch, and physical connection. They are starving for affection and emotional intimacy, and the only “hope” the church can offer them is to equate their mortal existence with an “unnatural” physical disability, or illness, one that did not exist in the pre-existence and will not persist in the next life. Many of my friends have explained to me that being changed or fixed in this regard in the afterlife would be like living in hell. I ask my heterosexual friends to therefore consider the following:

How would you feel if God fixed your heterosexual feelings in the afterlife and made them homosexual? I’m sure your answer would be the same: It would be hell.

I am not convinced that LGBTQ orientation is a disability, or illness. After all, it is a pretty well-demonstrated fact that numberless kinds of birds and mammals and primates do engage in homosexual behavior, but our species for some reason is the only one desiring to condemn it, calling it “unnatural,” even though it is the most naturally occurring reality — albeit marginal reality — among all species. It is privileged rhetoric that tells LGBTQ people they are disabled and abnormal, even though what they feel is no different than what their heterosexual friends feel. As many of my LGBTQ friends would say, “I’m not ill. I’m just in love.” This statement reveals that LGBTQ people are essentially desiring everything we hold valuable in our religion — families, committed relationships, loving each other, etc. Ironically, their desires for these things are being intimidated with disciplinary councils and excommunication if they act on them.

Again, do not misunderstand me.

I am not endorsing any sort of laissez-faire, promiscuous relations between LGBTQ people. I am not in support of those relations even among heterosexuals. I am merely arguing against the swaggering, puritanical certainty that exists in our congregations that compels us to reject the value of LGBTQ relationships, then assembles us to legislate laws through organized phone banks that deny them the same privileges that heterosexuals enjoy. I am arguing against our inability of admitting that good can come from family structures we institutionally disagree with. I am arguing against how convinced we think we are — how absolutely certain we know! — that relations between two happy, monogamous, legally married, consenting adults somehow merits our profound social and legal hostility.

I feel great compassion for my LGBTQ friends and will stand with them in whatever they decide to do. I will not demand that they become who they are not — nor will I guilt them with harmful rhetoric as the price of my friendship. I will look to find Jesus in them, who always stands disguised in those who suffer. I will look to them to be my teachers, their patience having been made deep by pain can impart profound lessons. I will encourage them that when their loyalty to church authority is held in dynamic tension with the demands of an informed conscience, to choose conscience. Choose the light within. Choose the still, small voice. These teachings I learned from my Mormon heritage, which I feel richly blessed by.

0 notes

Text

Priesthood — Its Power is a Gift, Not a Rite

Similar to the misperception about our claim to a one true church, there is a general tendency among members to reject the efficacy of any priesthood administered outside the institutional walls of the church. Good, honest, diving-seeking people outside of Mormonism have been culturally determined within as having no legitimate priesthood due to their lack of institutional mediation and ordination. This posture is misleading and non-scriptural and forgets that the priesthood was restored before the church was organized and can exist and operate independent of a formal organization. Our claim to divine institutional authorization does not need to be confused with the non-scriptural assumption that no divine priesthood or spiritual power can exist outside of Mormonism.

Joseph Smith, for example, taught that priesthood was first and foremost a divine, spiritual power inextricably tied to the Holy Ghost, and that the rights to the priesthood “are inseparably connected with the powers of heaven.” The priesthood, or any responsibility within it, cannot be purchased or commanded, but operates “only upon the principles of righteousness.” Failure to live the gospel and retain the spirit separates the rights of the priesthood from our ability to speak and act authoritatively. We may very well then believe we hold the priesthood and still not actually be empowered by the priesthood if our full-bodied desires — including our heart, mind, and might — are not in the right place.

Ordination, in other words, or mere membership alone, does not guarantee genuine spiritual transformation, nor does it guarantee the all-important power needed to sanction the priesthood as effective. What good, then, is the priesthood if it has no power? Priesthood without power is like Jesus without Christ. Without the power of the priesthood — the Holy Ghost — the legalistic function of the ordinance is dead, good for nothing. Or, as Joseph taught, we might as well baptize a “bag of sand.”

One reading of Section 121 implies that we should start viewing priesthood beyond ordination rites and more as inward spiritual power. This is not to suggest that ordination rites are unimportant, only that our preoccupation with them often swindles us into believing that priesthood can be compelled by position, office, gender, or mere membership alone, none of which are true. Priesthood power, and the ability to speak and act authoritatively, is contingent upon personal strivings, or light-of-Christ righteousness. Because this power cannot be patented except on these principles, I think it would be healthier to view priesthood beyond church governance, ordination, maleness, and the exclusive right to act for God, if only to avoid the dangerous arrogance of believing that we alone are right, that we alone can vie for God’s power, and that others cannot if they disagree. I believe that a very real form of priesthood — even if not its fullness — can exist among people outside our church who especially exhibit great “faith, hope, charity, [and] an eye single to the glory of God.” “Therefore,” the Lord says, “if ye have desires to serve God ye are called to the work.”

Institutionally, we are not accustomed to speaking of believers outside our faith as having legitimate priesthood because 1). it disrupts our narrative of formal ordination, 2). it makes us worried that the need for ordination is unnecessary, and 3). it opens the door for anyone to make false claims to priesthood authority. However, these beliefs do not take into account that many sincere people can and often are spiritually reborn long before a given community ever ritually embraces them. Joseph Smith and even Jesus understood that there was divine power in many of the words and works of people outside the covenant, demonstrated when they asked if a person’s spiritual acts resulted in good fruit. When outsiders are empowered by the Spirit, their fruits are empowered by God, and if empowered by God, what other priesthood could they be wielding?

What makes these points above disturbing is how quick we are to disclaim any priesthood that bears not the mark of ecclesiastical office, even if the power of God is palatably present in those without the mark. Even more disturbing is how willing we are to accept any priesthood that does bear the ecclesiastical mark, because we assume that proper ordination automatically implies a direct line to God. I find these postures idolatrous and perhaps even anti-scriptural because they place trust in the appearance of priesthood while denying the reality of priesthood whenever it manifests in non-traditional ways. Section 121 leaves open the possibility that individuals called of God but not necessarily ordained by the institution may access the power of the priesthood on mere principles of righteousness alone.

After all, there is no way to validate institutionally those who claim to speak for God except to know them by their inward, spiritual fruits. We do not often think of priesthood in terms of inward spirituality because we’ve somehow allowed outward priesthood (office and ordination) to take precedence over inward priesthood (spiritual gifts). There are reasons for this of course. My argument here is simply to invite us to accept the inward, spiritual priesthood of God wherever it may manifest, both inside and outside the church, both in traditional and non-traditional ways. My argument here is to showcase that there is more than one way to interpret our traditional narratives.

Personally, I am not inspired by narratives that perpetuate the primacy of male-dominated institutional power, nor am I inspired when we promote the primacy of Mormon-dominated priesthood power. Instead, I am moved by narratives that embrace the powers of the Spirit in conditions where males and females, members and non-members, share with God their power, profession, and spiritual mission to heal and bless human families. God’s work is not limited to Mormons, nor should it be limited to worthy, male Mormons either. As various church leaders have emphasized, “men are not the priesthood.” I would go one step further and state that Mormons are not the priesthood either, nor do they possess it when they undertake to “gratify [their] pride” or “grieve the Spirit of the Lord.”

Admitting that other religious and secular traditions can possess inward priesthood is no different than claiming that God bestows spiritual gifts and callings upon all cultures and people. It also means that if we do hold the fullness of the priesthood, both outer and inner forms, it is imperative that we forgo emotions of elitism, arrogance and complacency. As President Dieter F. Uchtdorf has challenged, “In order to exercise [God’s] power, we must strive to be like the Savior.” I would hope this “exercise” can include room for people outside our faith to do the same.

0 notes

Text

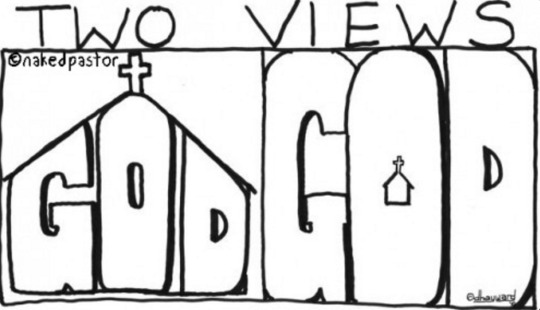

The Scepter of LDS Exclusivity

Whenever I hear members bear testimony of belonging to “the only true and living church upon the face of the whole earth,” I automatically think of Inigo Montoya from “The Princess Bride.” In my head, I rehearse the famous line: “You keep using that [phrase]. I do not think it means what you think it means.” Many I know have interpreted this scripture to mean there is no truth or spirituality or salvation outside of Mormonism. Others have been more subtle: “Well, there’s truth to all religions, but ours is most essential.” Both attitudes are where arrogance and the sin of idolatry take root. I think the most unfortunate misperception about our claim to “the only true and living church” is that we rarely articulate the all-important paradox at play that could even make sense of such a conceited claim.

The Book of Mormon, for example, paints a different picture. 2Nephi 29 challenges the authority of the Bible by breaking its monopoly on scriptural truth, then goes one step further implying that The Book of Mormon itself (along with other distinctive sacred texts outside our canon) is but one divine record in a vast world compendium. As Richard Bushman points out, “The Book of Mormon . . . prepares the way for itself by ridiculing those who think the Bible is sufficient.” It then warns against anyone who restricts God from speaking outside of Mormon scripture, especially when God’s voice appears to go against the grain of rigid orthodoxy.

“For I command all men, both in the east and in the west, and in the north, and in the south, and in the islands of the sea, that they shall write the words which I speak unto them; for out of the books which shall be written I will judge the world, every man according to their works, according to that which is written.”

Prophetic books and voices are flooding the earth. Wherever Israel is scattered those histories are being recorded, regardless of whether its writers are ritually embraced into the covenant. The Book of Mormon thinks big by multiplying God’s people beyond an exclusive, organized church and reminds us that all nations will receive their measure of revelation: “For behold, the Lord doth grant unto all nations, of their own nation and tongue, to teach his word; yea, in wisdom, all that he seeth fit that they should have.” The misguided, though, will exclusively cling to their particular set of books as sacrosanct when they should be willing to accept new revelation wherever it breaks forth, both in traditional and non-traditional ways: “And because my words shall hiss forth, many of the Gentiles shall say, A Bible, A Bible, we have got a Bible, and there cannot be any more Bible.” Ironically, many of the covenanted will replace the word “Bible” here with “Quad.”

The Lord rebukes this posture in ecumenical terms:

“Wherefore, because that ye have a [Quad] ye need not suppose that it contains all my words; neither need ye suppose that I have not caused more to be written…For behold, I shall speak unto the Jews and they shall write it; and I shall also speak unto the Nephites and they shall write it; and I shall also speak unto the other tribes of the house of Israel, which I have led away, and they shall write it; and I shall also speak unto all nations of the earth and they shall write it.”

Bushman continues: “The tiny land of Palestine does not begin to encompass the revelation flooding the earth. Biblical revelation is generalized to the whole world. All peoples have their epic stories and their sacred books.”

The tragic paradox of our culture is this: 2Nephi 29 teaches us about an ecumenical, generous, liberal, and almost near universal dispersal of divine power, truth and scriptural communications as belonging to everyone in general and no group in particular; and yet, many Mormons I know still narcissistically position the church as monopolizing these gifts under a traditional, institutional framing of an exclusive-organized tribe. The Book of Mormon derails this pompous posture, revealing instead that God has not spoken the final word or given the whole of divine truth to any person or people or institution. Bushman writes: “The world is a hive of bible-making, and in the end all these records will come together, and people will know one another through their bibles.” 2Nephi 29 reaffirms there are many promised lands, many chosen people, many lost tribes, and many records yet to emerge to reconcile us all. Knowing this, we can’t afford to substitute our humility with a closed, cocksure posture.

Ironically, it took The Book of Mormon to challenge us to reassess our assumptions by calling into question any vain denial of the validity and holiness of other traditions. The 1831 revelation in Doctrine & Covenants 49 further undermines this pernicious myth that outside churches and traditions are without truth or spirituality, wherein the Lord tells Joseph that nearly the entire world is under sin, “except those which I have reserved unto myself, holy men that ye know not of.” The Lord’s true disciples, in other words, are not limited to those who find themselves within the walls of Mormonism. As the apostle Orson Whitney declared:

“God, the Father of us all, uses the men of the earth, especially good men, to accomplish [God’s] purposes…They are among the church’s auxiliaries, and can do more good for the cause where the Lord has placed them, than anywhere else…God is using more than one people for the accomplishment of [God’s] great and marvelous work. The Latter-day Saints cannot do it all. It is too vast, too arduous for any one people…We have no quarrel with the Gentiles. They are our partners in a certain sense.”

Until Mormons are culturally mature enough to celebrate and diffuse an attitude of love, humility, and acceptance of God’s work among all people of the earth — and truly accept the Divine in images other than our own — our ironclad claim to a one true church falls ineffectually short to living up to its ecumenical potential. Thank God for 2Nephi 29 and Doctrine and Covenants 49, right? We can now give up our pretensions to a traditional-exclusive church and look forward to that glorious day that Nephi portends, wherein all truth will be circumscribed into one great whole.

0 notes

Text

Reasons I’d Be Atheist, But Choose to Be Religious

Putting it Mildly

I often wonder how I’m still an active member of the Mormon Church when many of my personal beliefs frequently do not align with the members of my congregation. My faith has changed and deepened over the years, hopefully for the good, but I am finding it harder and harder to attend church most Sundays. I still faithfully attend, serve, and uphold my callings, but the act for me has become a routinized widow’s mite. A kind of wild clinging to the iron rod that ten years ago felt more nailed in the sure place.

Unlike most faith crises, I am not really struggling with historical, theological or metaphysical claims of the Restoration. I am mostly just bored at church. I am deadened by how small, vapid and homogenous the gospel picture looks when interpreted by my fellow ward brothers and sisters, even prophets and apostles at times. I am amazed by how alien I feel in the pews; an insider who feels like an undesirable outsider. I do not think like those in my ward, and can only imagine what they’d think of me if I were to let them in on my well-guarded secret. Instead of feeling strengthened and uplifted, I often leave church feeling totally drained, depressed and disturbed. For me, Sunday is not a day of rest but a day of cross-bearing.

The Gospel is Pure, but the Culture is Messy

These feelings are really hard for me to process. They do not represent well the expansive and exciting character of Mormonism I read about in the scriptures, nor are they in harmony with the deep, panoramic feelings I get when worshipping in the temple. The Creative God I learn about in Genesis, for example, revels in distinctions, differences, and variation, whereas the Uniform God I learn about in Sunday School militates to homogenize disparity and command conformity. Fewer propositions are more aesthetically, morally, and rationally appealing than Joseph Smith’s theodicy of human potential, yet fewer places are more dull, tiresome and soul-suckingly lifeless than a Mormon meetinghouse. The Zion I live in, as opposed to the Zion I aspire to, is replete with all sorts of messy, counterintuitive feelings.

Such feelings call me into a paradox: I should confront my emotions, own them, but never maintain a false sense of certainty of “all is well in Zion.” Truth is, I am not certain about a lot of things I hear at church. This is not to say I am stating unbelief in the central tenets of Mormonism. To the contrary, I would argue that my views strive to be in concert with the many core principles and doctrines (albeit some interpretations). However, I am reticent to embrace the many testimonies and other expressions of certainty I hear that use clear-cut rhetoric to describe circumstances that are, in fact, not so clear. I am not convinced that feeling certain automatically implies that our emotions hold an ethical valence. Good thing in Mormonism we’re not required to believe anything that isn’t true, right?

While the gospel resonates with me in a really powerful way, there are many opinions we voice and postures we hold at church and throughout our culture that make atheism, at times, feel like a more desirable option. I am genuinely frightened, for example, by how quickly we seem to understand things, how defensive we get when challenged, and how easily we draw conclusions with the weight of authority on our side. I am staggered by how often we treat our prophets as demigods, our scriptures as inerrant, and our infallible testimonies of both as incontrovertible. It’s not even necessarily the opinions I hear at church that unease me. It’s the impressive, ironclad — “We can’t be wrong” — certainty that’s used to support them.

These might sound like “cultural problems” that are unrelated to the purity of the gospel itself. Yet, the truth is that my experience of the gospel is almost always inescapably mediated by, and conditioned by, the culture I find myself in. Where the gospel and the culture clash is that place we call “Church,” and this means admitting that the gospel will always be entangled with a mess of unfortunate ideas, boring meetings, people who exacerbate, and legalistic postures that irritate, bruise, and anger me at times. Hearing the Lord’s voice through this noxious environment is extremely difficult, especially in a church that cherishes certainty over humility.

The Challenge of Certainty

Where did we learn this posture of a pure and undivided certitude, in which everyone agrees (at least it seems at church) about the nature of doctrine but no one ever feels inclined to doubt another’s interpretation? Are we saying there’s only one correct way to be a follower of Christ? Is this something Joseph Smith endorsed? If not, why are we so bent on being so agreeable? So overbearingly polite? I mean, really, why are we so bad at handling disagreement? I can think of maybe two examples.

Jesus did unequivocally state: “I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine.” He also said “the spirit of contention is not of me, but is of the devil.” From these verses, which arguably have multiple meanings, it’s not hard for me to imagine why most members of the church are tempted to prize certainty at all costs. Certainty alleviates the anxiety and fear that accompanies ambiguity. It dispels the thought of being wrong about deep, cherished beliefs. It grants power and control over uncomfortable feelings. As Bruce Hafen suggests, certainty helps engender feelings “of trust, loyalty, harmony, and sincerity so essential to preserving the Spirit of the Lord.” And when reached, certainty helps us feel “at-one” with our ward brothers and sisters, thus fulfilling the command.