Text

Week 10: Online Harassment: What It Is, Why It Hurts, and How We Can Fight Back

What Is Online Harassment ?

Online harassment is any form of abusive, threatening, or harmful behavior that takes place on the internet. This can include things like cyberbullying, hate speech, spreading private information (known as doxxing), stalking, sexual harassment, and the sharing of non-consensual images or videos. It happens across all kinds of digital spaces: social media, online games, messaging apps, forums, and even comment sections (Pew Research Center 2021).

Online harassment happens for a range of reasons; often rooted in power imbalances, anonymity, and social norms that have spilled over into digital spaces (Kim, Ellithorpe & Burt 2023). The internet provides a platform for connection and expression, but it also creates an environment where harassers can act without immediate consequences.

Harassment can happen to anyone, but certain groups are targeted more often; especially women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people from minority backgrounds. Gender-based harassment is particularly widespread and deeply rooted in offline sexism. To show how serious and common it is, let’s look at findings from a landmark survey by Plan International, which asked over 14,000 girls and young women (aged 15–25) across 22 countries about their experiences online.

58% of respondents had experienced some form of online violence.

In Australia, the number was even higher with 65% of girls reported being harassed online.

Abuse ranged from abusive or insulting language (59%) to body shaming and sexual threats (both 39%), as well as deliberate attempts to embarrass or humiliate (41%).

Platforms where this abuse most often occurred included Facebook (39%), followed by Instagram (23%), WhatsApp (14%), Snapchat (10%), Twitter (9%), and TikTok (6%).

You might wonder: why focus on girls and young women in particular? Because they’re disproportionately targeted in ways that are more personal and gendered; like being threatened with sexual violence, stalked, or objectified (Davey, 2020). This doesn’t mean others aren’t affected, but highlighting these experiences helps us understand how identity shapes someone’s vulnerability to harassment, and why stronger protections are urgently needed.

The Effects of Online Harassment

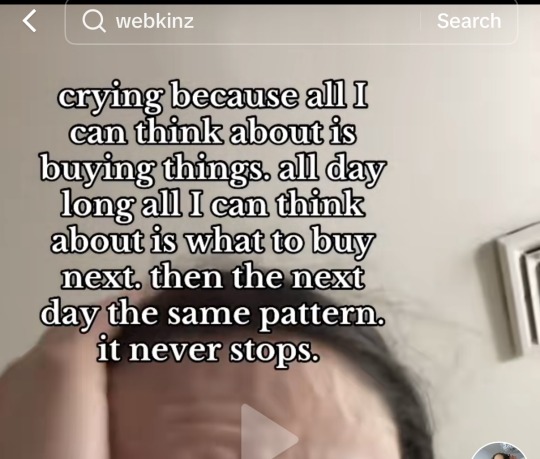

The consequences go far beyond the screen. Many victims of online harassment experience mental and emotional distress, including anxiety, depression, and in some cases, suicidal thoughts or actions.

In Plan’s survey, nearly 40% of girls said the harassment had caused low self-esteem and long-term mental health problems. In Australia, half of those harassed reported emotional distress, and 1 in 5 feared for their physical safety.

Online harassment doesn’t just silence people, it actively pushes them out of digital spaces. Around 1 in 5 respondents in the Plan's survey said they had reduced their social media use, and 1 in 10 changed how they expressed themselves online. For some, being online at all became too dangerous.

Tragically, in some cases, the psychological toll can lead to suicidal thoughts or actions. According to a research by National Institute of Healths (2022), participants who faced cyberbullying were over four times more likely to report having suicidal thoughts or attempting suicide compared to those who had not been bullied online. There have been real, heartbreaking stories of people who took their own lives after being relentlessly harassed or bullied online.

youtube

What can we do as digital citizens?

Online harassment is a social issue, and as digital citizens, we all have a role to play in making online spaces safer. Here’s how:

Educate ourselves and others about respectful online communication. This includes calling out harmful behavior, even when it doesn’t directly affect us.

Support victims, especially friends and peers, by listening without judgment, reminding them that they’re not alone, and helping them report abuse if needed.

Report harassment to platforms and demand accountability:

On Facebook or Instagram: File a report here

On X (formerly Twitter): File a report here

On TikTok: File a report here

On YouTube: File a report here

In Australia, if you’re seriously impacted by cyber abuse, report it to eSafety: www.esafety.gov.au/report

Push for better policies. Governments, tech companies, and advocacy groups must do more. But change also comes from the ground up through youth activism, education, and speaking out.

Protect and create safer spaces, especially for those most often targeted. This could be as simple as moderating a group chat, reporting a harmful post, or standing up for someone who’s being attacked, etc.

References

Davey, M 2020, Online violence against women ‘flourishing’, and most common on Facebook, survey finds, the Guardian.

Kim, M, Ellithorpe, M & Burt, SA 2023, ‘Anonymity and its role in digital aggression: A systematic review’, Aggression and Violent Behavior, vol. 72, no. 1359-1789, pp. 101856–101856.

Pew Research Center 2021, ‘The state of online harassment’, Pew Research Center, 13 January.

Plan International 2020, Free to Be Online?, Plan International.

Reynolds, S 2022, Cyberbullying linked with suicidal thoughts and attempts in young adolescents, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

#mda20009#online harassment#online hate#online harms#cyberbullying#mental health#mental wellness#mental heath awareness#mental wellbeing#problems#change#digital citizenship

0 notes

Text

Week 9: Roblox and Kids: Fun, Risks, and Safety Measures

What Is Roblox and Why Do Children Love It?

Roblox is an online platform that allows users to create, share, and play games developed by other users. Launched in 2006, Roblox exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic and now has over 70 million daily active users worldwide as of 2024 (Statista 2025). Nearly 67% of its users are under 16, making it one of the most child-dominated digital spaces today.

One major reason for Roblox's popularity among children is its creative freedom (Liao 2020). Unlike conventional video games with fixed stories and rules, Roblox lets users build their own games using a free tool called Roblox Studio. Children can create anything; from obstacle courses to fashion shows; then publish these games for others to play. This allows users to be game developers, designers, and storytellers all in one.

Roblox also supports high social interaction. Players can customize their avatars, make friends, chat in real time, and join group activities. With millions of games available and new ones added daily, there's always something fresh to explore.

Is Roblox Safe for Kids?

While Roblox offers many benefits, it also comes with serious safety concerns, particularly for younger players who may not fully understand the risks of online interaction.

One major concern is exposure to inappropriate content. Although Roblox has moderation systems and age ratings, not all games are suitable for children. Some games include violence, horror elements, or mature themes (James 2022). Developers often use creative naming or scripting to bypass content filters, allowing questionable games to slip through moderation. For example, “condo games” (a term used for user-created games with sexual content or roleplay) have been an ongoing issue, despite efforts to ban them.

Another danger is online grooming and exploitation. Since players can interact via text chat or voice features, predators can pose as children and attempt to form relationships with real minors (Otago Daily Times 2024).

The Hindenburg Research report (2024) raised even more alarm by labeling Roblox a “pedophile hellscape,” alleging that some users were trading explicit material involving minors using Robux as currency. The report claimed Roblox’s moderation failed to prevent such incidents and questioned the company’s transparency. Although Roblox disputed the findings and said many examples were outdated or incorrect, the concerns mirror issues raised by journalists and watchdogs for years.

How Roblox Tries to Keep Kids Safe?

Here are the key actions they’ve implemented to protect young users:

Age-Appropriate Restrictions: Roblox allows parents to set up accounts for kids under 13, which come with limited chat access, filtered content, and no third-party ads. They also introduced age-based content categories (3+, 9+, and 13+) to better control what children see and play.

Moderation System: A combination of AI filters and human moderators is used to scan chat messages, user-generated content, and uploaded games. However, because anyone can upload games, not all are reviewed before going live; so community reports play a key role.

Parental Control Tools: Parents can turn off chat, set privacy controls, and even review their child’s interactions. For kids under 13, chat is automatically filtered. New features like voice chat are restricted to verified users aged 13 and up.

Developer Rules & Game Reviews: Developers must follow community guidelines. Violations can lead to bans or game takedowns. Games promoting gambling or inappropriate content are not allowed. Roblox also prevents scams by requiring all purchases to go through their official system.

Education & Support for Parents: Roblox offers guides and safety tips to help families set up secure accounts. Features like Account Restrictions Mode and PIN-protected settings give parents more control over their child's experience.

References

James, D 2022, Watchdog group issues warning to parents about inappropriate content on Roblox, www.cbsnews.com, CBS News.

Liao, S 2020, How Roblox became the ‘it’ game for tweens – and a massive business | CNN Business, CNN.

Otago Daily Times 2024, Roblox ‘sexual predator grooming ground’ for young gamers: expert, Otago Daily Times Online News, Otago Daily Times, viewed 23 March 2025, <https://www.odt.co.nz/news/national/roblox-sexual-predator-grooming-ground-young-gamers-expert>.

Roblox 2024a, Roblox Community Standards, Roblox Support.

― 2024b, Roblox Refutes Misleading Claims in Hindenburg Report, Roblox.com.

Statista 2025, Roblox games DAU by age group 2024, Statista.

0 notes

Text

Week 8: TikTok’s Bold Glamour Filter and Eurocentric Ideals

What Is Bold Glamour?

Bold Glamour is a viral TikTok filter that launched in early 2023, powered by advanced AI and augmented reality. The filter has been featured in over 270 million videos, with the hashtag #BoldGlamour being used under more than 150 million posts. Unlike older beauty filters, it doesn’t glitch or distort with movement. Instead, it seamlessly locks onto your face and transforms it in real time. The effect is striking: sculpted cheekbones, fuller lips, a slimmer nose, flawless skin, and lifted brows.

The technology behind it uses machine learning and facial mapping to subtly alter bone structure and facial proportions. While TikTok hasn’t officially confirmed its creator, most signs point to an in-house development using AI-trained datasets (Roberts 2023).

A Familiar Ideal

The features promoted by Bold Glamour aren't random or purely aesthetic; they reflect a specific and historically dominant set of beauty ideals rooted in Eurocentrism. The filter tends to give users fair or tan-but-not-too-tan skin tones, slimmer noses, higher cheekbones, fuller lips, large eyes, and thin faces, typify Western beauty standards (Keigan et al. 2024). These traits have long been associated with white, Western standards of beauty - the kind often seen in Hollywood, high fashion, and global advertising (Elmi 2024).

These standards didn’t just appear by chance. For decades, Western media has exported an image of beauty that excludes non-European features (Shahzad 2020). Even as global conversations around inclusivity and diversity have gained traction, many beauty trends; including those built into digital platforms; still revolve around this Eurocentric template.

AR filters like Bold Glamour are powered by datasets and machine learning. If those datasets are trained on faces that already reflect dominant beauty ideals, the technology learns to reproduce and reward those same ideals. People might not explicitly say “this is beautiful,” but the millions of views, shares, and compliments speak for themselves.

youtube

The Psychological Consequences

Bold Glamour doesn’t just alter your appearance; it alters your perception of yourself (Kumar & Agarwal 2023). When millions of users see an AI-generated version of their face that looks “better,” it becomes easy to internalize that as the standard.

Psychologists have warned for years about the dangers of idealized images in media. But filters like this take it a step further. They push people; especially young users; to measure their worth against an artificial, algorithmically defined ideal (Dijkslag et al. 2024).

A 2021 study in the American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery found a strong link between the use of face-altering apps and the desire for cosmetic procedures. And according to the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, more people under 30 are now seeking cosmetic surgery or injectables, often influenced by how they look online.

Bold Glamour takes this even further. Unlike earlier filters that were obviously fake, its hyper-realism makes filtered images look like unedited photos. This blurring of digital and real life can intensify issues like body dysmorphia, as users compare themselves to a version of their face that was never real in the first place (Eugeni 2024). So when the filter disappears, your real face might suddenly feel less attractive, less complete; even if nothing has changed.

Bold Glamour may appear to be lighthearted fun, yet its impact runs deep. It reflects a system that subtly feeds self-doubt and fixed beauty standards. As the lines between real and filtered faces blur, the emotional cost is becoming harder to ignore.

References

Dijkslag, IR, Santos, LB, Irene, G & Ketelaar, P 2024, ‘To beautify or uglify! The effects of augmented reality face filters on body satisfaction moderated by self-esteem and self-identification’, Computers in human behavior, vol. 159, Elsevier BV, pp. 108343–108343.

Elmi, S 2024, The Effect of Eurocentric Beauty A qualitative study about Eurocentric beauty standards and ideals and its effect on women of colour, viewed 22 March 2025, <https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/873556/Elmi_Sahra.pdf?sequence=2>.

Eugeni, R 2024, ‘A scanner darkly: augmented reality face filters as algorithmic images’, Visual Communication, vol. 23, SAGE Publications, no. 3, pp. 498–512.

Keigan, J, De Los Santos, B, Gaither, SE & Walker, DC 2024, ‘The relationship between racial/ethnic identification and body ideal internalization, hair satisfaction, and skin tone satisfaction in black and black/white biracial women’, Body Image, vol. 50, p. 101719.

Kumar, H & Agarwal, MN 2023, ‘Filtering the reality: Exploring the dark and bright sides of augmented reality–based filters on social media’, Australian Journal of Management, SAGE Publishing.

Roberts, K 2023, Here’s Why TikTok’s New ‘Bold Glamour’ Filter Is Causing So Much Controversy, Cosmopolitan.

Shahzad, N 2020, ‘Occidentalisation of Beauty Standards: Eurocentrism in Asia’, www.academia.edu.

Varman, RM, Van Spronsen, N, Ivos, M & Demke, J 2021, ‘Social Media Filter Use and Interest to Pursue Cosmetic Facial Plastic Procedures’, The American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery, vol. 38, no. 3, p. 074880682098575.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 7: #looksmaxxing

Spend some time on TikTok, Instagram, or Reddit in 2024, and you probably came across #looksmaxxing. Looksmaxxing is the attempt to maximize the attractiveness of one’s physical appearance (Collins English Dictionary, 2024). This trend, mainly popular among young men, promotes intense self-improvement through fitness, skincare, facial exercises, and even plastic surgery.

At its core, looksmaxxing is about following aesthetic template (social media’s version of a beauty standard). These templates dictate what’s considered attractive, from sharp jawlines to “hunter eyes”. The problem? They create a rigid beauty standard that people feel pressured to achieve (Sternlicht 2024).

How Did Looksmaxxing Blow Up?

Looksmaxxing has been circulating in niche online communities for years, but it went viral on TikTok around 2023 (Usborne 2024). One of the most famous influencers promoting the trend is Kareem Shami. He first gained attention for his transformation and his content quickly went viral by teaching online young men how fitness, skincare, and facial exercises could change one’s appearance. His influence grew to the point where he was invited to speak on the Tamron Hall Show.

youtube

But why are so many young men drawn to this trend? Simple: validation. Social media runs on likes, followers, and attention, and looksmaxxing promises all three. Many who join the trend also struggle with low self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, and even mental health issues like body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Looksmaxxing preys on these insecurities, convincing people they can become more attractive and masculine if they just commit to the 'right' routine (Halpin et al. 2025).

One of the biggest inspirations for this trend is American Psycho. The morning routine scene from the movie; where Patrick Bateman meticulously applies his skincare, does his workouts, and stares blankly into the mirror; has become an aspirational aesthetic for many looksmaxxers.

Most Popular Looksmaxxing Features

1. Sharp Jawline by Mewing

One of the biggest obsessions in the looksmaxxing community is having a sharp, defined jawline. Enter 'mewing' - a technique created by British orthodontist Dr. John Mew that supposedly reshapes your jaw by pressing your tongue against the roof of your mouth. Mewing gained widespread attention when Dr. Mew’s son, Dr. Mike Mew, began promoting it on YouTube. The trend quickly took off, especially among those seeking a more sculpted face.

youtube

However, its effectiveness remains widely debated. The American Association of Orthodontists have stated that the scientific evidence supporting mewing is “as thin as dental floss.” (Leber 2024). While good posture and facial exercises might help with muscle tone, changing your bone structure with just tongue placement? Not so much.

2. Hunter Eyes

Another feature that looksmaxxers fixate on is having hunter eyes - a term used to describe deep-set, upward-tilted eyes with a “predatory” look. To achieve this, looksmaxxers chase over something called positive canthal tilt.

Canthal tilt refers to the angle between the inner and outer corners of the eyes. A positive canthal tilt (where the outer corner is slightly higher) is seen as more “dominant” and “aesthetic.” (Nast 2023). Looksmaxxers believe that having hunter eyes makes a man look more attractive, aggressive, and, ironically, “alpha.”

Since you can’t really change your eye shape naturally, some looksmaxxers turn to extreme measures, including surgeries like canthoplasty. Others believe they can train their eyes to look more predatory through facial exercises, squinting techniques, etc.

There are plenty more looksmaxxing methods out there, but at the end of the day, no one notices these "flaws" as much as those trying to fix them.

References

Collins Dictionary 2024, Definition of looksmaxxing, Collinsdictionary.com, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Halpin, M, Gosse, M, Yeo, K, Handlovsky, I & Maguire, F 2025, ‘When Help Is Harm: Health, Lookism and Self‐Improvement in the Manosphere’, Sociology of Health & Illness, vol. 47, Wiley, no. 3.

Leber, C 2024, Does Mewing Actually Reshape Your Jaw?, American Association of Orthodontists.

Nast, C 2023, What Is a Canthal Tilt, and Does It Really Determine How Attractive You Are?, Glamour.

Sternlicht, A 2024, Inside the ‘looksmaxxing’ economy: Jawbone microfractures, expensive hairspray, and millions to be made off male insecurities, Fortune.

Usborne, S 2024, ‘From bone smashing to chin extensions: how “looksmaxxing” is reshaping young men’s faces’, The Guardian, 15 February.

#mda20009#looksmaxxing#mewing#hunter eyes#glow up#american psycho#patrick bateman#transformation#lookism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 6: Mending Over Buying

If you told your grandparents that mending clothes is now considered a “climate-positive action,” they’d probably laugh. Back in the day, fixing up torn clothes wasn’t some bold environmental statement; it was just common sense. Clothes were expensive, and people made them last. Every household had a sewing kit, often stored in an old cookie tin on top of a cupboard. Mending was simply a necessity.

Fast Fashion: Cheap, Trendy, and Designed to Fall Apart

Fast forward to today, and things have completely flipped. Thanks to fast fashion, clothes have never been cheaper or more disposable. Why bother sewing a ripped shirt when you can replace it for the price of a cup of coffee? Fashion brands flood stores with trendy, poorly made clothes, designed to fall apart quickly so you’ll keep buying more (Bau 2017). As a result, the fashion industry generates more than 92 million tons of waste each year, while clothing production consumes approximately 79 trillion liters of water (Niinimäki et al. 2020). The industry create new styles at a ridiculous pace, encouraging us to constantly refresh our wardrobes and throw out the “old” stuff (even if it’s only been worn a few times).

Fast Fashion’s Biggest Scam: Making Us Stop Caring

But here’s the real problem: fast fashion hasn’t just made clothes disposable, it’s made our connection to them disposable too. Most of us have no idea how our clothes are made, who makes them, or what it takes to create a single garment. More disturbingly, we don’t care. When something tears or wears out, we don’t think about fixing it because we’ve been trained to see it as replaceable. And that’s exactly how fashion brands want it. This mindset comes from advertising that promotes the idea that new is always better than old (Bau 2017). The less we care, the more we consume.

As The Guardian puts it, our disconnect from the things we own has left many of us feeling alienated. Karl Marx once said that for work to be fulfilling, it has to be meaningful, honest, and effective. The same goes for the things we own (Martin 2021). When we replace well-made, personal belongings with mass-produced junk, we lose our sense of connection to the things around us. We don’t see clothes as valuable anymore, just as stuff to cycle through. It’s all about chasing the next trend and never actually be satisfied with what we already have.

Mending is a Quiet Rebellion

Mending is a quiet act of rebellion against all of this. It’s a way of saying, "No, I don’t need to keep buying just because a brand told me to." When you repair your clothes, you’re taking control. You’re refusing to throw something away just because a tiny rip appeared. And honestly? Mended clothes look cool. Visible stitches, patches, and embroidery make each piece unique; something mass production can’t replicate (Jones & Girouard 2021). It’s not just about making clothes last longer; it’s about rejecting the idea that you need to buy new things all the time to feel stylish.

The fashion industry thrives on making us feel like we’re always behind, always needing more (Williams 2022). But what if we stopped playing along? Mending is not only about sustainability but also about taking back power from an industry that survives by making us feel inadequate.

So grab a needle. Repair the damage; not just to your clothes, but to the way we see fashion itself.

References

Bau, M 2017, Fast fashion and disposable item culture: The drivers and the effects on end consumers and environment, 5 May, Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences.

Jones, L & Girouard, A 2021, ‘Patching Textiles’, Creativity and Cognition.

Martin, M 2021, Mend your clothes and do yourself some good, the Guardian.

Niinimäki, K, Peters, G, Dahlbo, H, Perry, P, Rissanen, T & Gwilt, A 2020, ‘The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion’, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 189–200.

Williams, E 2022, ‘Appalling or Advantageous? Exploring the Impacts of Fast Fashion from Environmental, Social, and Economic Perspectives’, Journal for Global Business and Community, vol. 13, no. 1.

#mda20009#fast fashion#sustainable fashion#consumerism#recycling#tailoring#fashion industry#mending#clothing repair#slow fashion#environment#environmentalism

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 5: How Hashtag Activism Backfires

One day, we saw a movement is trending on the internet. The next? It’s buried under the latest meme. While hashtags have the power to amplify voices and bring attention to social issues, they also come with a catch: virality doesn’t always mean impact.

When Activism Feels More Like a Trend

Let’s talk about #BlackoutTuesday. The idea was simple: post a black square to show solidarity with Black Lives Matter. People promise not to post anything else that day and instead reflect on how non-Black Americans benefit from structural racism. But instead of boosting important conversations, it clogged social media feeds, drowning out actual resources and activism. The choice to go silent was flawed. Movements should amplify voices, not silence them (Noman 2020). Brands and influencers participated, but many treated it as a one-time performance rather than a commitment to real action (Spielmann et al. 2022). This is where hashtag activism struggles. Good intentions often get lost in performative gestures.

The Problem with Oversimplified Activism

The internet loves a catchy slogan, but real-world issues are never that simple. #Kony2012 blew up as a viral campaign against Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony, but it quickly became a case study in Western-centric activism. It framed the crisis as something international intervention could fix. The movement overlooked local voices and real solutions, ignoring the complex political reality. It made people feel like they were part of something big, but once the hype died down, Uganda was left to deal with the aftermath of a movement that didn’t actually understand what it was trying to fix (Faloyin 2022). And that’s the problem with a lot of hashtag activism; it makes change feel instant, but real progress is slow, messy, and can’t be wrapped up in a neat, shareable post.

The Danger of Misleading Messaging

Words matter. #DefundThePolice was meant to advocate for shifting police funding toward social services like mental health support, housing, and education. But "defund" was a loaded term. It gave critics an easy way to misrepresent the movement as advocating for total police abolition, which wasn’t the goal for many activists (Bates 2021). The backlash was immediate, with politicians and media figures spinning the phrase into a fear-driven narrative (Cillizza 2021). Some cities experimented with budget shifts, but the movement struggled to maintain traction as the debate shifted from policy solutions to justifying the slogan itself.

At the end of the day, a viral hashtag is just the beginning. It can start conversations, but real change takes strategy, policy work, and actual activism. Without that, even the loudest movements fade into digital noise. So before jumping on the next trending hashtag, ask: is this just an online moment, or is it part of something bigger?

References

Bates, J 2021, How Are Activists Managing Dissension Within the ‘Defund the Police’ Movement?, Time.

Cillizza, C 2021, Even Democrats are now admitting ‘Defund the Police’ was a massive mistake | CNN Politics, CNN.

Faloyin, D 2022, Remember #Kony2012? We’re still living in its offensive, outdated view of Africa | Dipo Faloyin, the Guardian.

Noman, N 2020, What I learned about being a real ally after the #BlackoutTuesday disaster, NBC News.

Spielmann, N, Dobscha, S & Shrum, LJ 2022, ‘Brands and Social Justice Movements: The Effects of True vs. Performative Allyship on Brand Evaluation’, Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, vol. 8, no. 1.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 4: What Happens to Reality Stars After the Show? The Truth About Staying Relevant

Reality TV used to be the final destination for instant fame. Now, it’s just the first step. Before social media, reality stars had their 15 minutes of fame and then faded into thin air. Today, they turn their screen time into entire digital empires.

Reality shows like The Bachelor, Love Island, and The Kardashians don’t just make stars, they make influencers. The moment a season ends, the contestants aren’t just reality TV leftovers. They’re building their brands on Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. One minute they’re crying in a confessional booth, the next they’re launching skincare lines and selling out collabs.

The Social Media Playbook: Winning (or Losing) the Post-Show Game

Social media gives reality TV stars a level of control they never had before. A bad edit on Survivor? No problem. Just go live on Instagram and "clear the air." Got eliminated too soon? TikTok will keep you relevant. This change means that fame is no longer only dictated by TV producers; it’s controlled by the stars themselves too (Richards 2023). The audience follows them beyond the show, invested in their lives like an ongoing series (Tran & Strutton 2014).

And for those who play it right, social media can extend their influence far beyond what reality TV ever could. Contestants on Love Island walk away with built-in followings, and whether they become fashion influencers, podcasters, or lifestyle gurus, they now have a direct line to their audience without needing a network’s approval. The Kardashians mastered the reality TV-to-social media pipeline better than anyone. They are turning family drama into billion-dollar businesses, launching countless brands, and redefining influencer culture. They are not only stay relevant but changed the entire game.

The Price of Staying in the Spotlight

But with the fame comes the hate. And it’s brutal. Reality stars don’t just get fans, they get trolls, harassment, and nonstop scrutiny (Ouvrein et al. 2019). Every post is picked apart, every mistake goes viral, and the same platforms that makes them famous also destroys them. Cyberbullying is relentless, and for many, the pressure is unbearable. Some quit social media entirely; others struggle with their mental health in ways reality TV never prepared them for. The same audience that made them famous can just as easily tear them down.

For years, the tragic suicides of reality TV contestants have exposed the darker side of instant fame. Stars from The Bachelor, The Voice, and Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares have all faced overwhelming public pressure, but few stories hit as hard as Hana Kimura’s. The 22-year-old star of Netflix’s Terrace House became a heartbreaking example of how online harassment can turn the dream of reality TV fame into a nightmare (Adegoke 2020). Her death was a wake-up call, but the cycle of fame, scrutiny, and digital cruelty continues.

The pressure to stay relevant also means they have to keep posting, keep engaging, keep monetizing (Gómez 2019). Keeping up with the algorithm is a full-time job, and the fear of becoming yesterday’s news is always existing. One viral moment can launch a career, but one misstep can just as easily end it. Many stars feel like they’re trapped in an endless cycle of content creation just to maintain their audience’s attention. Some turn to controversy to keep engagement high, while others struggle with burnout, anxiety, or even public breakdowns as they try to keep up with the never-ending demand for new content.

Reality TV hands contestants the spotlight, but social media makes them work for it every single day. In a world where attention equals opportunity, staying visible isn’t just a choice; it’s a necessity.

References

Adegoke, Y 2020, ‘Why suicide is still the shadow that hangs over reality TV’, The Guardian, 27 May.

Gómez, AR 2019, ‘Digital Fame and Fortune in the age of Social Media: A Classification of social media influencers’, aDResearch: Revista Internacional de Investigación en Comunicación, vol. 19, no. 19, pp. 8–29.

Ouvrein, G, Hallam, L, J. S. De Backer, C & Vandebosch, H 2019, ‘Bashed at first sight’, Celebrity Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 1–18.

Richards, J 2023, Personal Branding, Reality Television, and Social Media: How Personal Branding, Reality Television, and Social Media: How Former Big Brother Contestants Create, Maintain, and Alter Their Former Big Brother Contestants Create, Maintain, and Alter Their Public Image Public Image.

Tran, GA & Strutton, D 2014, ‘Has Reality Television Come of Age as a Promotional Platform? Modeling the Endorsement Effectiveness of Celebreality and Reality Stars’, Psychology & Marketing, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 294–305.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 3: How Platform Vernacular Created the 2014 Tumblr Aesthetic We Still Miss

Ok, so let’s talk about an era that lives rent-free in our minds: Tumblr in 2014. If you were there, you know the vibe. But what exactly is that vibe and why is it so unforgettable?

What Even Is Platform Vernacular?

Every social media platform develops its own distinct way of speaking, known as platform vernacular. It is a unique blend of slang, memes, and communication styles shaped by the platform’s culture and features (Gibbs et al. 2015). Tumblr in 2014 was something special; full of chaotic, expressive, and deeply connect with the aesthetics of its time. How they engaged with content, how they reblogged, tagged, and captioned posts in ways that became part of the aesthetic itself. Without this distinct language, the 2014 Tumblr aesthetic wouldn’t have existed in the way we remember it today.

Tumblr had its own language: reblog, dash, notes. Hitting 10k notes meant Tumblr fame. Phrases like "i can’t even", "this ruined my life", and "screams into the void" were everywhere, always in lowercase for ✨aesthetic✨. The vibe was Lorde, Lana Del Rey, Arctic Monkeys, vaporwave edits, and existential memes. The 3 AM scrolling, dramatic reblog chains, and cryptic text posts made Tumblr feel like a collective fever dream.

The 2014 Tumblr Aesthetic Was Built on This Language

Tumblr’s 2014 aesthetic wasn’t just about fashion or photography; it was a whole mood. The sad, moody, depressed, and artsy vibe worked because Tumblr was a space where people curated their identities (Thelandersson 2017). The soft grunge and pastel goth aesthetics weren’t just image but also part of the way users communicated.

What made the 2014 Tumblr aesthetic so powerful was how it felt uniquely personal, yet universally shared (Hillman, Procyk & Neustaedter 2014). Tumblr’s aesthetic was about raw emotion and intimacy. The way people reblogged, captioned, and tagged posts reinforced the idea that these images weren’t just pretty; they meant something. However, within the 'sad girl' subculture, sadness and depression were not seen as unusual but rather as aspirational qualities (Thelandersson 2017).

The platform’s language shaped the emotional impact of its content. You weren’t just posting a sad Lana Del Rey quote in a black-and-white gif; you were sharing a piece of your soul, and someone, somewhere, was going to see it, reblog it, and think, same.

Why Does It Make People Feel Nostalgic?

People still talk about 2014 Tumblr like it was a golden age because it was more than a trend; it was an era. It was a digital subculture where teenagers and young adults found belonging (Mccracken 2017).

Tumblr in 2014 was a space where people could be unapologetically emotional. The aesthetic was moody and melancholic because it reflected how many users felt. For those navigating teenage angst, self-discovery, or just a general sense of existential crisis, Tumblr provided a comforting, relatable space.

Unlike today’s algorithm-driven platforms, Tumblr’s dashboard was organic and intimate. Trends didn’t die in a week; they lasted for years. Everyone was in on the same jokes, aesthetics, and cultural moments. It was like living inside a giant, moody scrapbook curated by the internet.

The Tumblr 2014 aesthetic wasn’t just something you saw, it was something you lived through. Without Tumblr’s unique language, the aesthetic wouldn’t have hit the same.

And honestly? That era of the internet will never be recreated the same way again.

References

Gibbs, M, Meese, J, Arnold, M, Nansen, B & Carter, M 2015, ‘#Funeral and Instagram: death, social media, and platform vernacular’, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 255–268.

Hillman, S, Procyk, J & Neustaedter, C 2014, ‘Tumblr fandoms, community & culture’, Proceedings of the companion publication of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing - CSCW Companion ’14.

Mccracken, A 2017, ‘Tumblr Youth Subcultures and Media Engagement’, Cinema Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 151–161.

Thelandersson, F 2017, ‘Social Media Sad Girls and the Normalization of Sad States of Being’, Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry, vol. 1, no. 2.

5 notes

·

View notes